ENVIRONMENT HEALTH

Item

- Title

- ENVIRONMENT HEALTH

- extracted text

-

RF_E_3_PART_1_SUDHA

I

Weekly Edition —3

THE

IzcliaX Notiouai NouMpapefc

Sunday,June

1980.

HINDU

Printed at Madras, Coimbatore, Bangalore.

Hyderabad and Madurai

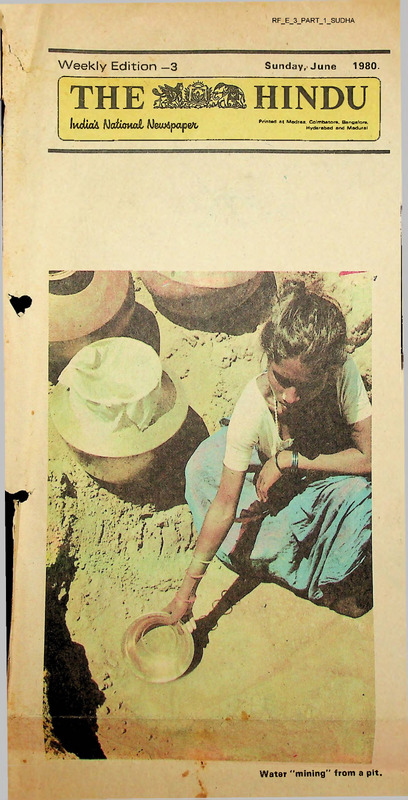

Water "mining" from a pit.

ROTECTED water supply, especially

for those in the villages — whether

j

they live on the banks of a perennial

river or in coastal villages or in the arid zones—

is still an unsolved problem.

Even in a town like Tiruchi, right on the

banks of the Cauvery, where the corner

stone for the present water works was laid

in 1 892, people do not enjoy uninterrupted

water supply — not to speak of a number

of pockets within the municipal limits still

not receiving drinking water.

In Pudukottai district, 1,1 40 hand pumps

were provided to tap ground water under

the aegis of the UNICEF. They very often

go out of order. Putting them back to use

is a major headache to the Water Board

maintenance staff. An assessment has

shown that it costs nearly Rs.1 40 a month

to maintain a pump.

during the Seventies also made an

intensive exploration and identified that in

Tamil Nadu three zones — Neyveli belt,

Aranthangi coastal belt and Tiruvadanai

belt in Ramnad district — have copious

ground water potential. It has even mapped

the transmission zones where the sea

water and the ground water aquifers meet.

In Pudukottai district during the

Sixties, the ONGC and a few Central

agencies engaged themselves in exploring

the ground water potential. The ground

water cell of the State Government,

The cell suggested that in these areas,

ground water could successfully be tapped

through deep bores and that this water,

after treatment, could be made potable.

In the villages in Aranthangi, Aavudayarkoil and Arimalam panchayat union limits,

water in open wells is saline because of

sea water intrusion. The mainstay for them

is the water from the tanks and ponds which

receive replenishments during the monsoon.

The people draw water at the

“drinking water ghats" as distinguished from

the "bathing ghats" of the tanks. They

take the water in pots and allow the mud

to settle.

Twelve comprehensive water supply

schemes (CWSS) were drawn up by the

TWAD Board for the benefit of the coastal

residents in the region covering a

population of nearly one lakh.

Mr. M. Subramaniam, Executive

Engineer, TWAD (Rural Water Supply Division),

Pudukottai, said that 1 2 bore wells had

been sunk to a depth ranging between 600

and 1 ,700 ft.

There is at present the curious

practice called "mining". Water is first

collected from the pit in a small brass

utensil and transferred to a pot. It takes

about 30 minutes to fill a pot of water.

Supply from

an artesian well.

All the deep bore wells of the CWSS are

artesian wells, Mr. Subramaniam pointed

out. A sum of about Rs. Three crores has

been earmarked for the 1 2 schemes, but

maintenance strategies have not been

worked out. Water from the artesian wells

has more hydrogen sulphide than surface

water. Through aeration, sedimentation and

Alteration the impurities were removed and

only treated water was being pumped into the

distribution mains.

Tiruchi Staff Reporter.

Weekly Edition —3

THE1

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 7,1980

B HINDU

Iw/lioA Notiouat klewApapeft,

Pf ntod

at Madras Coimbatore Qangaiora

Hyderabad and Madurai

o

-4?

utants

YDERABAD is one of the nine

■ FT- cities in the country where the na. I Lltional air monitoring programme

has been undertaken by the National

Environmental Engineering Research In

stitute (NEERI), in accordance with the

World Health Organisation's suggestion

to assess air quality within the framework

of selected parameters. Madras, Bombay,

Delhi, Calcutta, Kanpur, Ahmedabad,

Jaipur and Cochin are the other centres.

WHO chose India in 1978 as the nodal

J^nt in South-East Asia for air monitoring.

I he main purpose of the programme is

to alert the public and authorities about

any abnormal increase in pollution levels

and to ultimately enthuse local1 agencies

to take the programme into their hands.

Four parameters are chosen for monitor

ing pollution levels. The programme covers

the determination of the quantum of sus

pended particles and that of sulphur diox

ide, an assessment of sulphation rate and

of dust fall. The programme includes

collection of meteorological information

for data interpretation.

Increasingevidencetheworldoverseems

to prove that certain concentrations of

particulate matter, sulphur dioxide, carbon

monoxide, photochemicals, oxidants and

hydrocarbons produce serious tetratogenic,

carcinogenic, mutagenic and other effects.

Besidesaffecting health, pollutantshave

been found to be responsible for the

decrease in atmospheric visibility damage

to buildings and corrosion.

In order to limit the deterioration in

air quality and improve it further, scientists

formulating.

control measures and ascertaining the

magnitude of air pollution from time to

time.

This necessitates the establishment of

a continuous air quality monitoring network

to obtain concurrent and comparable data

on both gas and dust levels in the at

mosphere.

In Hyderabad, NEERI has selected three

places for air monitoring—the Abids com

mercial area, Tarnaka and Moulali residen

tial areas. Air monitoring, a pilot programme

in Hyderabad, will continue till 1983.

Yet, the problem of pollution is oc

casioned by the lack of adequate sewer

lines and improper location of industries.

For the location of industries, the

athorities do not have base line data about

air quality, the scientists say.

A systematic planning for the location

of industries will foster the establishment

of more industries without fouling the

atmosphere.

NEERIhasbriefedtheHyderabadUrban ■

Development Authority on air quality survey ■

in Hyderabad to determine the level of I

pollution, to define the areas of pollution I

according to the levels, and finally to I

develop mathematical models to predict I

pollution levels, identify the pollution I

sources and suggest control measures.

I

NEERI proposes to prepare air quality '

maps which will help decide the proper

location of industries. NEERI also proposes

to take up air quality monitoring programme

in Visakhapatnam where industrialisation

is apace.

Environmental scientists suggest that |

air filters should be used to reduce the

vehicular emission of carbon monoxide

and carbon dioxide. They also suggest

that autocatalytic convertors should be

used, as in the U.S., to reduce effectively

the carbon dioxode and carbon monoxide

emission.

Atcoal-basedthermalplantsandcement

factories, the scientists say, electrostatic

precipitators should be installed to absorb

dust particles. Similarly, for chemical in- I

.filters and wet scrubbers

Mr.A.ShyamasunderRao,MLC,recently 11

raised in the State Council question of 11

air pollution in Mancherial town (Adilabad II

district) where a cement factory is located, II

with a coal mine nearby. The Minsiter II

for Municipal Administration, Mrs. Sarojini I

Pulla Reddi, said that it was proved that

pollution was high in Mancherial town.

I

The cement factory had set up a dust

collecting equipment. The factory would u

be advised to take effective steps to prevent

the dust from escaping into the atmosphere.

magnitude of,air pollution from time to

time.

This necessitates the establishment of

a continuous air quality monitoring network

to obtain concurrent and comparable data

on both gas and dust levels in the at

mosphere.

In Hyderabad, NEERI has selected three

places for air monitoring—the Abids com

mercial area, Tarnaka and Moulali residen

tial areas. Air monitoring, a pilot programme

in Hyderabad, will continue till 1983.

Mr.A.ShyamasunderRao,MLC,recently

raised in the State Council question of

air pollution in Mancherial town (Adilabad

district) where a cement factory is located,

with a coal mine nearby. The Minsiter

for Municipal Administration, Mrs. Sarojini

Pulla Reddi, said that it was proved that

pollution was high in Mancherial town.

The cement factory had set up a dust

collecting equipment. The factory would

be advised to take effective steps to prevent

the dust from escaping into the atmosphere.

A Scientist measuring the presence of Gases entering the High Volume Sampler with the help of

Manometer at Abid’s Centre, Hyderabad, where the air pollution effects are found to be very high

NEERI has fabricated sampling gadgets

adaptable to local conditions. Sulphur

dioxide and samples of suspended particles

are collected every tenth day: a sampling

frequency of three times a month.

y About ten years ago, the air quality

in Hyderabad was good, in the light of

U;S. standards. But industrialisation in

some pockets of the city and the increase

in vehicular traffic have contributed to

the deterioration of air quality over the

city.

A hue and cry has been raised against

further industrialisation in and around

Hyderabad. At one time, some officials

even suggested a ban on further industr

ialisation in the city and the shifting of

industries to other parts of the State.

But, environmental scientists were not

sure that these reasons attributed for pollu

tion were indeed correct. Compared to

the industrialisation of other big cities

like Bombay, Calcutta and Bangalore, the

number of industries located in Hyderabad

is not significant.

There was, however, no pollution problem

in Mancherial due to the coal mine. NEERI

would be approached to conduct a survey

of pollution levels in Mancherial.

Recently, some people working in the

drainage galleries of the Nagarjunasagar

dam, complained of suffocation, fatigue,

bronchitis and breathing trouble. The pro

ject authorities requested NEERI to find

out the cause.

The NEERI scientists conducted experi

ments and analysed the levels of hydrogen

sulphide, carbon monoxide and carbon

dioxide for eight days in September and

concluded that in certain. parts of. the

galleries, humidity was extremely high.

One of the remedies suggested by the

scientists is more ventilation at various

levels of the galleries.

After laboratory arid pilot plant studies,

NEERI has designed effluent treatment

plants for all major industries in the State.

Hyderabad Staff

Reporter

Colour

Transparency

by

Our Staff

Photographer

.

Co

.... nt’ALTH CELL

Floor) St. Marks Road

I

Concepts Background.

A

Proposals

V

560 001

bl \Z 1 HO i\l 1'1 EJT -iH PnAW bi I x>IG

E

A. Historical

- - . . _ - - — - -r» ■ ^.■..|^ ■■■■»- .w> >■ ■background

i■

••• Mu ■■ i i and —definitions

■ r— •— — - ■ ■ i

n

m

J*

*M

la

■■ .»»

«■

<

*

a

•

*

a*

•

Hobert Owen was among the .first to see that, unless

controlled9 machines producing within a modern market

economy would have socially harmful consequences; and he

wrote in:1815?

*

•

•'The general diffusion of manufactures throughout

a country generates a new character in its inhabitants;

. and as this character is formed .upon a principle

quite unfavourable to individual and .general happiness,

it will produce the most lamentable and permanent

.evils, unless its tendency- be counteracted by

Legislative interference and direction ...... the

governing principle of trade manufactures, and

commerce is immediate pecuniary ..gain, to wnich.on

the groat scale every other is made to- give/way.

rfhen Owen failed to persuade the government of his day

to listen to his arguments he demonstrated the beneficial ‘

effect that the secure environment of a welfare-oriented

textile mill had on the workers and their productivity at

blew .Lanark. The mill made consistent profits in an era

when other mills were closing down or incurring losses even

though Owen, paid out L 7000 in wages for four months when

the mill was closed. • Thus, as early as the beginning of

the nineteenth century, 185.years ago, farsighted individuals

wer< recognising the not-so-welcome effects of industriali

sation. - From this ooint on the nature of mancs concern

for the environment maybe traced.

•

at

•

•

•

®

The example of England is instructive?

1800 - 1824? iiobert Owen managed the pioneering but

eventually short-lived textile mill at New Lanark.

1

.

'I

.

1844 - 1845 ? Frederic Engels investigated the slum

conditions and wrote ‘The Condition of the Working Class in

England-’ describing the poverty and the terrible -physical

conditions.

‘

■/

•

“

b

y

W

•

•

•

1848 2 The Government passed the first Public..Health Act

regulating the sanitation and sewage arrangements in the

newly sprung up industrial townships. . •

•

* •

•

1868 : The Artisans and ..Labourers Dwellings Act was passed

to regulate the individual housing.

•

I

*

1875 : fhe Artisans and Labourers Dwellings Improvements Act

w-s passed to further control the development of housing. The

Public Health Act was amended to give the municipalities

permission to set up separate departments for dealing with

sewage and sanitation.

2

w

•

I8780- 1890 s Different industrialists adopted the -garden

town" approach to plan their industrial townships in order

to make life more'livable for their industrial workers.

Cadbury set up Sournyille in 1878, Lever sot up Port

Sunlight in 1887 s and now litre;- set up a townsnip in York

in 1890,

4

•

*»

^

*

**

J

•

•

•

•

•

*

••/•••

w

.

1909 ? So far the attempts to control the environment had

been mainly in the.hands of the industrialists wishing to

have a healthier working force or the State in keeping towns

free of epidemics and disease. But during the Boer 4ar

it was discover-' d that recruits from working-class areas

were very weak.- sometimes too’weak to even lift a rifle.

A committee sot up to investigate the reasons for this

reported.on the-appalling living conditions of the working

class and recommended the passing of legislation to control

these conditions. Accordingly in 1909 the government

passed the Town Planning Act which gave the State authori

ties the power, for the first time, dictate how private

property in land was to be used.

1930s 2 The massive problems of the world-wide recession

giving rise to crises in industrial production, employment,

transport etc. gave rise to the first debates on regional

disparities and government action to control these in a

laissez-faire economy.

'• ’

• 19^7 s ’The first Labor government had come, to power and it

tried to implement the first steps of State controJ^over

planning, through hationalisation and the Town and Country

Planning Act which extended planning .concepts from the

city to the village areas.

•

•

. 1950 ? do rid dur II had by- now devastated a''large number of

r towns and these had to be rebuilt from scratch.

In.,

addition John Maynard Keynes had shown through his general

theory how the State not-only could but had to act with

its enormous fiscal .and polit!cal-powers to control the

economy. Thus the rationale for State planning was

established.

•

1968 2 -dith the complete breakdown of the . colonial system

and its consequent economic problems'the government had to

make additional efforts to organise and manage production,

housing, transport, food.etc. Hence the new Town and

Country Planning Act'was passed to control the environment.

■*

<

1970 s di th the increase in education and political

consciousness various sections of the public began to

fight both private and public enterprise on environmental

Issues of location, noise, pollution, etc. and so the

State integrated environmental action by setting up the

Department of the Environment. :

3

all tills is neither completely repr: sent itive of

developments in other countries nor unique.

For instance,

State Planning began in earmest in :the USSR in 1920, Even

the US and UK had extensive experience in control by

Government during the two Jorld Jars.

India did not go

through the same process of industrialisation as the UK

nevertheless it adopt d much of the social and planning

legislation of Groat Britain, But the trends are fairly

clear.

In the 1920s environmental issues wore mainly raised

as a protest against industrialisation and its despoliation

of the countryside.

In the 1960s it became fashionable to

talk of pollution, ecology, and muchelse. But in the 1970s

population and pollution have become pressing problems for

governments everywhere.

//hat we learn from history then is that the’ degradation

and control of the environment became public issuesfor

governmental action only when they posed economic problems

in the course of production for private profit -and that

governmental action had to take up increasingly stricter

positions with regard to private property and its use so

that the social fabric was not destroyed,

Jhen these underlying issues become clear we can now

proceed to define our concepts of Environmental Planning so

that these become helpful in understinding our society and

the tasks we have to take up in order to correct its ills.

Je may take -as a starting point Frank Fraser Darling’s .

comment s •’ ,, we need to develop some yardstick for. human

content^ to be able to measure the lesser doget of discontent

and psychosomatic disease in rehabilitated environments.

This is the ultimate concern of politics, •’ Je can now

define Environmental Planning as that political exercise

in allocation and management of resources wnich improves

the well-being of those engaged in production, prevents the

harmful by-products of industrialisation, and preserves

the natural resources, ■'

Je have already dealt with the first two issues, we

shall now take up the third,

‘

*

3. Resources -human and material - and development?

4b

Jo shall not enter here into the debate on the world

ecological crisis - important though it may b< - but shall

concentrate on the case of India using underdevelopment as

an illustration of the ’ general problem of development.

4

Food, energy, and production are intimately related to

the economic state of a nation. The following figure reveals

with great clarity the position of India with respect to

the rest of the world?

.

- Ko

5

• C>w^

't

- 30

• UK

I

1

> ;

yj, Q,

20

y.

G

%S£-*

01

0 VK

<^5*

- 10

£

o

•

—

•

*

.'

'

500 low

-

.

4500

*

.

•

2000

2500

*

f

3000

•

Cross national product(dollars per capita)

e

f

•

■

z

.

- The jJS uses’ov:-r 4-ty X 10 Kcal per c ipita of’which

8.16 X 10° Kcal were- used to provide food for an average

US' resident of which^ further, 18%’ w is used on the farm. If

all the world hud the sarie per capita energy bill for the

entire food chain, a quantity equal to two-thirds of the

1970 world commercial energy use- would have been consumed

for this purpose.

• %

••

Let us look at a few more' relevant figures?

1.‘Between 1971-73 the industrialised countries-with 30$

of total world population produced 60% of the world’s food.

5

2. The US supplied between 1965 and 1970 50/<> of the world’s

exports of cereals and its fellow industrialised countries

took 2/3rd of these exports.

3. The cost of all commercial food exports was

§996 m in 1955

§3000 m in 1967

§4-000 m in 1972

§9000 m in 19744. On present trends

(a) the annual increase of food supplies is

208/0 in the industrialised world

2.7% in the developing world

(b) the annual increase of food deiiiand ds

1.5% in the industrialised world

3*5% in the developing world.

5. The consumption of cereals is

222 kg in the developing countries

1000 kg in the industrialised world (per capita). Of

tni’s 1000 kg only 70 kg is consumed directly by hum m

beings. The rest (930 kg) is either fed to cattle and

consumed as beef or supplied as luxury food to pet

animals.

6. 372 m tons of grain are used annually for livestock feed

in the rich countries. This is approximately the total

amount of grain now consumed directly by humans in

China and India (total population 1400 million).

To illustrate further the dynamic relationship between

food, energy, production and money, lot us take the -case of

a typical hypothetical developing country:

It might be assumed that in country X 20% of the food

requirements are being met by farmers using Green devolution

techniques, there is available only limited foreign

exchange, and half of the fertiliser supply is imported. If

•a lOO/o increase in fertiliser price occures, the following

sequence of events may take place:

i. because of limited foreign exchange, fertiliserpurchases must be halved, reducing total fertiliser

supply to 75% of the original level.

ii. Farmers using Green devolution technology bid up

the price of fertiliser discouraging other farmers

from trying this practice.

iii. The total foodgrains supply drops 2^^, but since

f irn famllies consume half the country°s food, the

shortfalls in marketable surplus is 5^°

iVo Persons anticipating the shortage enter the market

trying to buy advance food supplies, consequently

driving food prices up to perhaps double their

original level.

v. Persons with low incomes who must buy food are forced

to starvation level diets.

vi o The government in oMer to prevent st arvation, buys

grain on the world market and soils it internally

■it low prices.

vii. Grain purchases consume the limited foreign exchange

reserves being accumulated for energy resource

development and fertiliser plant construction.

Food prices in such countries become linked to inter

national energy, fertiliser, or food prices irrespective of

the productive capacity of the people. With energy prices

dependent on what the market will bear, affluent economies,

which are already dependent on high energy use and stand

to incur great Losses if energy flow is cut, can afford to

bld energy prices up to very high levels. One recent model

of California agriculture shows shadow prices of diesel fuel

of around §550 per berrel. The impact of all this is

basically to prevent countries such as X from using or

expanding the use of Gree devolution technology.

dearing in mind that industrial development depends

upon surpluses accumulating froz/agriculture and upon

adequate food supplies in an underdeveloped but developing

economy let us also look at estimates of world resource

depletions

dumber of years until total resource depletion based

on current exponential rates of uscs-

aluminium

Coal

Gold

manganese

dickel

52

147

26

91

93

Molybdenum 62

Cobalt

145

Iron

170

Mercury

38

Petroleum

47

Chromium

151

Copper

45

Lead

61

Natural gas 46

Platinum •

82

tfithin such a macroeconomic situation what are the

specific problems that India faces and will have to face?

7

1. By 2000 a.D. the population will r<ach ?0 crores.

2o Jith increasing population pressures land ownership will

be fragmented making it all the more difficult to apply

aodorn technology.

3. There- will, therefore, be a decline in land productivity.

By the end of the century 210 million tonnes of foodgrains

will be required to feed the population -an increase of

100 million in 25 years.

5. There will be the increased need to export goods at

competitive prices in the world market.

60 Large' scale under- and un-employment will exist in the

agricultural sector.

7. Consequently, there will be large migrations to the cities.

80 Disparities in income, health, education, housing etc.

etc. will continue to grow.

90 The quality of the environment will continue to deter

iorate further adding to the vicious cycle of under

development and poverty.

The figures for agricultural and industrl •*! growth

rates reveal the 'dimensions of the struggle to grow:-

, •

Agricultural growth rates - 56/57 to 7O/71a

1. 5 t o 6/0 with small variations — Punjab,Haryana,Kar• • *

nataka.

2. 5. to 7/0 with large variations — Rajasthan, Gujerat.

3. 2^ -. 3/ .[.with small variations — Ta-ailnadu, Kerala.

4. 3 - 3iX

with large variations — Orissa,We st Bengal,

•

Uttar Pradesh.

■5 = Under 2% with small variations — Andhra, Assam.

6a unic-r 2% with large vari.itions — Bihar,Madhya

Pradesh, riah irashtra.

Rate of growth in large-scale manufacturing sector:

_

•

Plan I

Plan II

Plan III

Plan holiday

Plan IV

Plan V

target

7.00

10.50

10.75

12.00

8.00

realisedp.a.

6.00

7.25 ■

8.00

3-33

2.75

(agriculture)

A.2

4.0

- 1.4

6.2

2.5

Here again it should .be remembered that agriculture

provides the base for national development.

It both provides

the purchasing capacity for manufactured goods in the rural

areas, the raw materials for agroindustries, the market

for agriindustries, and the surplus for industrial investment

8

in the initial stages.

//hi le the 'Gr' on devolution

brought about some r- markable technological; innovations

it only raised the output of -wheat, muiae, and jowar, quite

often at the expense of cotton, groundnut, and other cash

crops from which land was taken away. Also the output rise

levelled off after 5 years in 1970. The growth in agricul

ture has been limited because of (a) lack of cultivable

land? (b) inefficient land and water management.

The incapability of the economy to grow rapidly is

reflected in the social tensions and fears, a medical account

puts it thus:

’dising irreparable damage accompanies present industrial

expansion in all sectors.

In medicine these damages appear

as iatrogenesis.

Iatrogenesis can be direct: when pain,

sickness, and death result from medical care; or it can be

indirect: when health policies reinforce an industrial

organisation which generates ill-health; it can be structural

when medically sponsored behaviour and delusion restrict

the vital autonomy of people by undermining their competence

in growing up, caring, ageing; or when it nullifies the

personal challenge arising from their pain, disability, and

anguish. Most of the remedies proposed to reduce iatro

genesis are engineering interventions. They are therapeuti

cally designed in their approach to the individual, the

group, the institution, or the environment. These socalled remedies generate second-order iatrogenic ills by

creating a new prejudice against the autonomy of the citizen.*’

Thus far the problems are clear. What about the

solutions? In the next section we will deal with the

solutions proposed by governmental and institutional

authorities.

C. Planning for growth:

It is possible to approach social problems with

'Herbert Spencer’s attitudes:-

suffering and evil are nature’s admonitions; they

cannot be got rid of; and the impatient attempts of bene

volence to banish them from the world of legislation before

benevolence has learned their object and end, have always

been more productive than good.”

or assort with Leon Trotsky;’Through the machine man in socialist society will, command

nature in its entirety, with its grouse and its sturgeons.

He will point out places for mountains and for passes. He

9

will change tne course of rivers, und ho will lay down rules

for the ocr .ns. The idoilist simpletons may say th.it this

will be a boro, but that is why they are simpletons. Of

course, this does not nean that the entire- globe will be

narked off into boxes, that the forests will bo turned into

parks and gardens, host likely, thickets and forests and

grouse and tigers will remain. And nan will do it so well

that the* tiger wont even notice the machine, or feel the

change, but will live is he lived in primeval tines. The

machine is not in opposition to the earth. The machine is

the instrument of man in every field of life-’.

or to take positions in between.

distory certainly seems to favour Trotsky.

Given the postulate that it is possible for men to

change the reality through concerted -action let us see what

solutions are proposed by those who cun influence national

policy.

Outlining the Strategy for Integrated Rural Development,

C. Subramaniaia states that '‘The challenge facing us is for

harnessing the potential of science and technology for the

optimum use of all our natural assets - human, animal, and

physical - for banishing poverty from our midst". For

this he proposes that the focus be on the integrated use of

r-- sources and the provision of full employment. This is to

be d me bys-

1. Modernisation of agriculture through land reforms,

community nurseries, water management, pest control,

fish culture, and the use of post-harvest technology,

2. Emphasis on health and family planning.

3. Increased production of energy.

Setting up of agro-industrial complexes.

5- Improved management md marketing.

6. Setting down of minimum productivity standards.

7» Encouraging participation of locaVpeople so that public

agencies perform efficiently.

8o Investing in resear oh and scientific training.

9o Central coordination.

Thus, government is to take specific action in providing

the infrastructure for development (water, transport,pesti

ciics, health, family planning, power, panch.ayat boards,

research, education; administration etc.) and to propose

norms for private production.

• i. ’

rlajni Kothari, looking into the future at 2000 a.D.

mikes life styles, organisation of space, and organisation

of production the central Issues. Accordingly; he recommends

that:

10

1. The principal focus be on the goneration of employment.

2o This is to be done by c italysing the growth in agriculture

through the app Lieut ion of modern technology and

oxtensive land reforms.

3» Generation of employment in rur A areas through large

nub Lie works can be supported by agricultural growth

resulting in restriction of the migration to the cities

and provision of a base for rural industrialisation.

a social continuum has to bo maintained by planning so

as to reduce regional disparities.

5. Mass education is required for cultural changes to support

growth.

6. an ethic of consumption has to be laid down to control

the spending of the affluent classes.

?. The nature of production should be determined by the

needs of the masses.

8. Social minima in health, nutrition, education have to be

provided.

9o Participation by the people has to be enoour>ged at

every level in every institution.

Here, too, the St ite is to take the initiative in the

service sector and lay down production and social norms.

K.N. Ha j , investigating the causes'of Industrial

Stagnation in India arrives at the following analysis:-

1. Growth of industry does not depend on an increase in

the utilise! cap iclty but the pattern of demand for the

production.

20 The demand is of three types:- (a) private and domestic

consumptions (b) fr.om government and public enterprises

(c) for export.

3. Domestic demand is in turn dependent on the condition

of agriculture. Growth in income from agriculture will

increase domestic purchasing capacity.

Agricultural development will also affect ugro-based

industries.

5. Chemical and metallurgical-base industries mainly cater

to the affluent sections and hence should be strictly

controlled.

6. Therefore, it is necessary to focus <n agricultural

development.

7. This can be done by a package of land reforms, innovational

technology, development of small scale rural industries,

marketing infrastructure*, appropriate fiscal and credit

policies, and decentralisation of the decision-making

powers to the people’s institutions.

J

Once again, the State is to develop the infrastructure but

not interfere in the production for private profit itself-

11

So we see that a bread consensus exists amongst

policy-makers and economists on the scope' and content of

planning for growth. The consensus focusses on the need to

provide an infrastructural base for the development of

agriculture and rural industry so as to provide employment

but not to interfere in private profit oth<r than in laying

down certain norms.

In order to assess the value of these proposals we

need to analyse society and its structure more deeply and

systematically to arrive at an understanding of the confli

cting forces in society and their directions.

Only then

can we consciously choose the form of our intervention. In

the following section we shall attempt to look at certain

theoretical formulations of the nature of society and their

practical correlations.

D. Who plans, who pays, who benefits?

As we have seen in Section a planning w is undertaken

as a deliberate State function in order to reduce, if not

remove, the economic disparities between different sections

of the population. Thus the cure for the problem of poverty

was to be found in a redistribution of income and resources

primarily through the provision of employment.

Now

employment obviously means that there is an employer and an

employee. The employer works for profit and the employee

for wages.

Hence the essential relationship in all

production becomes one of wage-employment, and the price

paid for the product should recover both the cost of

production as well us the profit of the owner. The mathematical

femotionality can best bo described bys

p = c + v + s

where p = price of unit product

c = fixed capital investment per unit

product

•

v = Variable capitalper unit product

(including wages)

and s = surplus profit

s

or the rate of profit

r = _______

c

+

V

We shall now see how this equation from Marxian economic

analysis helps us to understand the dynamics of development.

The equation expresses two fundamental principless-

a) Firstly, for the economy to develop’the rate of profit

must always%bo a positive quantity greater than Q. Moreover,

in a competitive1 market it will try to maximise itself.

12

b) Secondly, the surplus available * is dependent upon to

what extent the -cost of production c+v can be decreased.

This specifically indicates a degrease in v which includes

the wage and is therefore likely to be resisted by the

wage-earner.

The satisfaction of these two principles has been the

task of planning ns we shall, now see.

1. Profit

a) r can be increased by keeping the cost of production

c+v constant but increasing the price p thus increasing

s.

In a market economy the simplest method of doing

this is to create a shortage in the supply. Such

profits are by and large taken by merchant trade. The

system of planned rationing of scarce goods while

aimed at price and supply control indirectly assists

the merchant who can take g )ods out of the rationing

controls and sell then on the open market. Sugar is

sold by the State to the authorised merchant at Rs. 2

per kilo who then, in collusion with government

officials, falsifies his books and sells the sugar

in the .market at Rs. 6 per kilo.

b)

If v can be decreased then r will increase. The most

common way of doing this is to incr ase the productivity

of Labour, pr -by technical innovations that reduce the

need for labour. Both cill for the correct management

of technology. Since the Emergency of June' 1975 the

tightening of -’discipline” has increased production

in the entire public sector.

Record targets,.increased

exports, and profits have been reported in coal,power,

steel, fertiliser, mining - all under State control

and essentially providing raw materials for private

industry and private agriculture. At the same time

layoffs are reported from many sectors of private

industry. An indication of the drive for profits is

that in 9 months in 7^-75 the rise in industrial output

w „s 3*2% after stagnation.’ In addition bonus and .

dearness allowances have been frozen to control inflation*.

c) Decrease in c in order to raise r takes a special

importance in a country where capital is scarce. The

objective of the conception of Appropriate Technology

is to introduce :tsuch processes and innovati >ns which

may not be capital intensive, should, be able to

generate employment and could be managed with local

skill and competence, using local raw materials and

13

should lead to capital formation for further investment.’

Profit (surplus) is therefore to be increased by minimal

investments in capital goods and infrastructural

facilities such is education and transport.

d) Capital availability- is essential for further investment

and growth.

Capit il is normally extracted from surplus

s but not all s has been invested in productive units.

Much of it has been converted into wealth or used for

luxury consumption. The government’s drive to unhoard

wealth, declare income, and control black money would be

interpreted as an attempt to divert more capital into

production.

Foreign aid is another source of capital

investment and various concessions have been proposed

to invite foreign investment. Net flow of external

assistance fell to Rs. 25^ crores in 1973 but it is

estimated to bo well over Rs. 1000 crores in 75-76. The

Nnrld Bank has recommended that gross aid to India

should rise from Rs. 2098 crores in 75-76 to Rs. 317^

cr. in 1980 to Rs. ^?20 cr. in 1985-86. This is to be

looked at in the background of invitations to multi-natio

nals to invest in India and the fact that the rate of

return on US manufacturing industries in India has

increased from 7.5% in 1967 to 15.8% in 1972.

Fiscal policies reveal the real nature of investment

distribution. The 1976 budget records the dramatic reduction

in direct taxation on personal income and wealth tax in

order to provide more purchasing capibity. Tax reductions

for private industry are also accompanied by an Investment

Allowance of 25% for acquiring plant and machinery. This

is in effect the reflection of the report last year that

the.. Ministry of Industrial Development was considering

a scheme to make it compulsory for all firms in selected

industries, including larger industrial houses, to

reinvest their profits in renovation, modernisation, and

expansion of their existing units. -Further incomes in

the budget arise from the Rs. ^80 cr. of impounded

Dearness Allowances of wage earners for a year. Of the

Rs. 7852 cr. of budgeted expenditure, two-third has been

allocated to defense and the primary sector (petroleum,

steel, transport, coal, fertilisers). Rs 15 cr. has been

allotted to C. Subrananiam’s Integrated Rural Development.

Credit policies have been specifically directed to

provide funds for investment to increase production in

rural areas while maintaining prices for 'agricultural

products at the same level.

e)

Increases in population wipe out increases in production.

To maintain growth and extract more surplus for investment

it is essential that the number of mouths to feed be

decreased relatively. Hence the heavy emphasis on Family

1L

Planning. Apart from the earlier incentives being

offered for steriLisations (cash rewards9 transistors9

etc.) and vasectomies etc. the Four-point programme has

established the rationale for application of enormous

administrative pressures,

FP clinics have been set

targets at the cost of their allowances; State govern

ments have been announcing penalities for those government

servants who do not undergo ’-sterilisation; ration

cards and employment are being tied up to family planning.

f) Early capitalist growth had emphasised the concept of

competition and hence ever increasing rates of profit.

The new "Ethics of consumption" and monopoly control are

attempts to put an end to run away competition.

-’The

Indian case tends one to conclude that the volume of

surplus product is not adequate to the scale of extended

reproduction in the structure where the product originated.

A large body of surplus product may exist side by side

with the stagnation of the structure or it may be mainly

expended to finance rapid expansion of production in

•another structure.

In sone cases the redistribution

system 'acts as a brake on extended reproduction9 thereby

maintaining the dominance of those sections of society

which live off the surplus product of a given structure.

If the volume and material composition of the surplus

product are well balanced-with the numbers9 demographic

dynamics and aspirations"of the dominant class9 then this

class for a long time• experiences rather weak stimuli

for change in the mode of production,

•

*

•

•

2, He si stance.

•

»

*

•

"

•

•

•

Resistance to the process of growth would be encountered

from those whose interests are harmed or not satisfied by

economic development./ Hence9 this resistance has to be

.overcome,

' .

'

• -

.

■/

*

-vra).Land reforms are essential to agricultural growth as the

older system of land ownership patterns1 is not conducive

to the application of modern technology. Large tracts

•of land under the ownership of one family and rented out

for subsistence farming to small farmers are not

.. productive neither is there the incentive for greater

production on the part of the shareholder or tenant.

The determined application of land celling Acts reflects

attempt to break the opposition of the large landowners.

b) However, land redistribution of tiny plots to landless

also does not make economic-sense for these too are not

viable for the application of technological Inputs.

The political rationale for this would9therefore, be to

15

ease the exploitxtion of bonded labour until such time

as alternative employment becomes available through

rural industries and public works.

c) The major conflict between employer and employee is

rooted in the ownership of the means of production. Wage

agitations9 strikes, bundhs, gheraos, representations

are reflections of this conflict. It is not sufficient

to ban the conflict and impose the ban by force. Other

measures to wear down the resistance are important.

One of the ways to do this is to' make the worker a

property owner too. The very process of education,

training, and employment ensures that the worker comes

from a background of petty ownership.

Worker participation

• in management attempts to give selected workers a

democratic chance to have a voice in a limited arc a of

owner control, iind there is the latest suggestion by

the Industries Minister to invest the impounded Dearness

'Allow?pee of workers in public sector shares. Corruption,

. too, plays a major role in providing government

servants with a vested interest in the existing process

of development.

In spite of the Emergency and the spate

of transfers 9 the patwari, the peon, the office clerk,

the administrative and executive officers continue to

receive their 10% share so that they nay supplement

the salary offered by the State. Traders, merchants,

contractors remark that corruption has not been removed,

it h .is only become 'lore expensive and hence less people

-can1afford.it. The structure of administration is also

•: designed to decentralise the conflict. Large production

and manufacturing units contract out portions of their

. work to large contractors who sub-contract to smaller

contractors who further sub-contract to petty contractors

• who contract out to labour contractors and skilled

- workmen and so on. The total surplus extracted is,

therefore, distributed in diminishing percentages over

a wide range.

'

d) Divisions within the opposition are also useful to

overcome the resistance.

The multipolarity of political

parties, the diversity of trade and labour unions, the

income gradations in the working class, the hierarchical

relationship between workers in different sectors of

industry, the conflict between the administrative

apparatus and the productive labour force are all

factors which divide the resistance and a unified contra!

coordination body is capable of successfully manipulating

these divisions. The 20 point programme provides the

correct platform for establishing the centralis ition.

e) Mass education Is advocated as the base for a democracy.

But the cost of mass education is very high. Instead mass

advertising provides a convenient method of building up

an image and attitude while selective training reinforces

16

the mass consciousness* Every mass media, every bus,

truck, and train carries the slogans of the 2Q-point

programme. The commercial advertising firms were

mobilised for this massive effort*

In addition regular

courses are being organised for union leaders, profess

ionals, and party members on the form and content of

the new economic initiatives. The point being constantly

driven home is that production is being reorganised to

provide for the needs of the masses,, that structural

transformations are being made to benefit the people.

With a record output of foodgrains last year to permit

the government to control food prices in the market

these statements can be proved sufficiently true for the

1xrgely uneducated population* In this context the loss

of democratic freedoms in sone areas means little at

the present time*

f) Potential resistances to the system lie in the young

people who enter the educational institutions expecting

employment at the end of the course. Banning unions,

rustications, and signed pledges arc not in themselves

enough*

Cultural, attitudinal changes are necessary

for their tolerance of the system* Publicity is valuable

but still not enough* Hence, opportunities have to be

provided to engage the youth in national action of some

sort* The National Service Scheme for students and a

plethora of other schemes for youth and social welfare

offer the opportunities potential problem-makers to

adjust to social realities*

It is estimated that such

schemes reach out t^ 6 to 7% of the student population

and the importance of these programmes should not be

underestimated*

g) The industrial trxnsitian in Europe was influenced by

arjd in turn encouraged the work ethic of Protestantism

which broke away from the earlier Catholic fatalism*

Neither Hinduism nor Islam have had such a break*

Hinduism remained and developed as an ideology of

developed feudalism which is why it forms the base of

the backward-looking political parties today. While

this offers problems for the industrial development of

India - which offers a rationale for charismatic and

autocratic leadership trends - nevertheless the system

of caste institutions exhibiting features of tribal

cohesion, slavish humility, and social estate organisation

are useful in absorbing dissent and peaching conformityfor instance, in the appeal by Vinob.a Bh-ave for an

era of discipline.

The reader may be wondering how all this is related to

17

exercise in the allocation -and. management of resources which

improves the well-being of those- engaged in productiona

prevents the harmful by-products of industrialisation, and

preserves the natural resources19.

(Here preservation is in

the sense of regeneration rather than mere protection,, )

The point by now is quite clear:- all planning including

environmental planning today, is undertaken under duress by

the profit-making sections of society in order to preserve

their dominance over society,, The real question then is

whether planning can be used in India to remedy this

situation and what should be the direction of the remedy?

E, Ideals and examples:

That the problems of industrial society lie tn the private

ownershipof the means of production and, thereby, production

for private profit was recognised even by Robert Owen with

whom we started this piper, hence, in the abstract plane

it is not so difficult to stipulate that if the motivation

for private’property wore to be removed from society.then

social and economic ills would be amenable to solution. Thus

the- demand for socialisation of the means of production,

ioO. social ownership and control..

To illustrate the point let us take the case of the

Hukamchand Jute Mills (manufacturing Caustic Soda) at

Anlai, run by private industry for private profit; Under; law

the Mill has to provide basic medical facilities for its

250 employees. Two years without a doctor in the health

centre finally sparked off an agitation amongst the employees

and within 24 hours a doctor was located and employed. The

salary of the doctor was fixed at Rs. 800 p.m. and the budget

for medical supplies at Rs. 1200 p.m.

Uithin a year the

doctor found that he was on duty practically 24 hours a day

as he was resident in the Mill colony and that the budget

for medical supplies was totally inadequate0

For instance,

chlorine gas leakages would occur frequently and up to a

dozen asphyxiated workers would be brought in demanding

immediate treatment. Tne first step in this would be to

supply Oxygen but there was only one compressed Oxygen bottle

to be shared between a dozen men.

In other instances most

workers would get the prescription from the' doctor and then

have to purchase the medicines from outside as the doctor

has specific instructions not to issue drugs except to

‘’important19 persons such as union office-holders and super

visors. Finally the doctor asked for a salary increase to

Rs. 1200 and a medical budget of Rs. 2500. After two months

of indecision the management offered the doctor Rs. 1000 and

no increment in the budget. The doctor resigned and the

Mill is once again without medical facilities. The question

to be asked is would the same have happened if the Mill had

boon under social (workers’) control rather than under

private ownership?

18

• Here is another report:

-This plant, started in 1968, refines several million tons

of oil a year.

I walk out among pipes and red banners to

the unlikely sight of pools of goldfish and ducks in cane

pons. There are smiles when I ask how these can stand the

polluted environment.

’’You have seen the point:3, says

a worker with a knowing grin,- but upsi :.o down'’. The fish

and ducks are the living fruit of ingenious affort to' beat

pollution. The plant emits waste water, the worker explains,

which contains harmful sulfides and phenols.

If allowed to

run away it would damage crops and foul rivers. The best way

to get rid of evil it was reasoned, is to turn evil into

good. Here is a tower where sulfides are removed from waste

water.

Over there is a cement pool where the residue of oil

is skimmed off it - and sent back for refining. Nearby, a n

oration tank where compressed air and a flotation agent are

added to the water. The water then flows into pools in

which the emulsified oil and flotation agent are scooped off.

Still left are the phenols, but with the aid of a rotary

beater they are absorbed by micro-organisms.

Now the water

is ready for the fish and ducks, as well as vegtable plots

which help to feel the plant’s workers. Everyone grins with

satisfaction as we survey this cunning sequence.'4

The plant described is General Petrochemical in Peking.

In the UK dereliction, neglect and misuse of resources

are found in all the old centres of the Industrial Revolution.

Of all the abuses the river’s require the most urgent

action because of their far-reaching impact on land, air,wild

life and people.

Of the 30 per cent..which need improvement,

over 10 pur cent arevseriously polluted. The river Trent

receives the sewage of the great midland cities. It could

cost nearly 200 million to .cleanse it to standards set 60

years ago, yet probably only a quarter more to treat the

sewage-so that the water is almost drinkable. Yet the UK

goverhiiient believes it to be significantly worthwhile to take

up ■ environmental restoration.

For instance, the Nuffield

Foundation, the Swansea City Council, and the Government

initiated a study of the valley of the river Tawe in 1961.

Over 1200 acres of this dead and derelict landscape bore

witness to the depredations of nineteenth-century copper

and zinc smelting.- during the investigations it was estab

lished that the legal problems arising from multiple ownerwhip

wore considerable. Other issues extended far beyond the

vaLLey. Reclaiming part of the site for light industry would

affect employment in neighbouring valleys where coal-mining

was on the decline.

Its use for recreation would relievo

pressures on unspoilt countryside, a formal report for the

project was presented in. 196?.. Rince then 5^ acres have

been-'reclaimed and much of the valley has been used for new

development projects or landscaped.

150 acres have been

19

afforested. Flood prevention schemes have been undertaken

on the river Tawe,

-but in order to resolve the multiple

ownership problems the Swansea City Council had to acquire

and amalgamate in land ownerships.

In the US Halph Nader wrote in- 197 1 2

’’The Federal

role in water pollutioncontrol began in 19^8 on a temporary

trial basis and became permanent in 1956. ... Beginning

with the drafting of the water pollution legislation, the

Federal effort grew into a complex charade. The built-in

procedural delays exceeded the professional avarice of

the most adamant corporate lawyers. The generic delegation

of initiatory moves to the states insured the availability

of. a 5livide-and-rule’ tactic by industry vis-a-vis

already subservient and underequipped state agrncies.

A 72 year old Federal law banning the dumping of industrial

pollution into navigable waterways went almost completely

unenforced until its 70th birthday when the first of some

30 in junctive actions were brought against a fraction of

the approximately -40,000 daily violators. Hundreds of

millions of dollars of construction grant subsidies flowed

from Washington to local government for waste treatment

plants which industry promptly used to dump more waste

through. This subsidy to local industry turned into a

subsidy to factories that increased water pollution. The

Kafkaesque tapestry extends into the mockery of Federal

enforcement conferences, the neverending deadline

extensions for the weakest of pollution controls, the

secured trade secrecy over what lethalities industries dump

into the public’s waterways, the clear evidence of serious

and worsening contamination of drinking water, the damage

to other people’s property and property rights by industrial

municipal, and agriculturalpolLution without even any

compensation. the loss of livelihoods for thousands of

commercial fishermen, and the emergence of water so laden

with ignitable wastes that, rivers such as the Buffalo and

the Cuyahoga are declared official fire hazards ....

Its

(the Federal role’s) effectiveness to date can be

concisely assessed by the virtual absence of any evidence

that the seven laws passed and more than three billion

dollars spent by the? Federal government has reduced the

level of pollution in any of our country’s major bodies

of water, so that they are once again suitable for human

use ....”

And, finally, some revealing data from Tachai, the

pioneering commune in China?.-

20

Product!on of grain

160

180

2^0

337

5^3

917

Individually (19^9)

'

Mutual Aid Team member (^8-52)

Cooperatives 1st year (53)

Advance cooperative 1st year (56)

Commune 1st year (58)

Present (7^)

Jin/mou

jin/mou

jin/mou

jin/mou

jin/mou

jin/mou

v/hat are the lessons that we. can draw from the historical

experience of this and other countries about environmental

control? —

•K

1. The technical aspects of control, conservationj and

regeneration are within the grasp of mankind.

2. The environmental economics is extremely important in

the long run but not so visible when the objective is

immediate profit.

3. tfhat we despoil today somebody else will have to pay

■ for tomorrow - at much higher cost.

4. Governments and agencies act on environmental Issues

-■ only when there is sufficient pressure from organisat

ions of people.

•

•

•

I

5. People organise on such issues when they have a direct

.• vested interest in as also a consciousness of the

■ preservation of the environment.

6.-Thus action for and against environmental planning is

, essentially political.

•

% <•

•

•

*

•

•

•*«•*

•

7. The large-scale aspect of environment al action makes

it imperative for the state to be involved.

8. Political action by those engaged in production is,

■therefore, the central issue of all environmental (and

•. other) action and planning.

, , . Merely a theoretical perspective will not lead to the

practical solution of the issues under consideration. The

slogan of .’’Socialism” is, therefore not a panacea for all

ills. It is a concept, a guide for action, a perception

of the future - a possible future not a determined one.

The possibilities of that, future depend upon the reali

ties of the present and the social forces that emanate

from the present. It is the consciousness of me about their

social fabric and environment that will determine how they

shape their lives, as conscious individuals, therefore,we

too have to set out specific takks and goals.

21

F.

Tasks;

The tasks "before us 9 then, would seem to lie in three

areas:

1. Intellectual:

A detailed understanding of how the present

planning process sustains and perpetuates an existential

society and of what are the dynamic forces within that

society interacting with planning is essential for

extrapolating- into the future., This is not merely an

academic exercise for a few individuals. Rather it

involves theoretically challenging the present system

and organising a structure that will enlarge the "body

of individuals conscious of social contradictions and

pose the issues for the larger society. The methodology

of setting up such structures and the formation of

cadres has been established in detail in another set of-.

papers and hence we need not gointo it hero.

2. Cultural:

A desire for change is rooted in the

realities of life.

If life is perceived to be unpleasant

and full of deprivation then forces are released for

bringing about a transformation in that way of life.

However, perceptions are.not absolute and what is

unpleasant for one nay be indifferent for another.

Responses to environmental factors can be conditioned

over periods of time. Those who have known nothing but

dirt and hunger, for instance, in their daily lives are

likely to accept these as unchangeable and given. Forms

of communication (newspapers, drama, propaganda) are

also intensively used by dominant classes to create

attitudes and thought processes that are - at that moment

of time - not aimed at changing society but rather at

preserving what is bearable in it. The task would,

therefore, be to examine what are the- forms of culture

that break away from the past and look into the future

and what is the relationship of these with the techno

logical forces extant in society. These issues have

been dealt with separately and we shall have to consider

in greater detail the methodological tools necessary.

3. Economic:

Since material conditions form the base

from, which consciousness arises (if there were no

poverty there would be no perception of poverty) and,

hence, the culture and organisation of human beigns;

therefore we have to look into the economic forces

and policies that dominate in society today and frem

this determine the way in which we would intervene.

For instance, if the trader extracts large surpluses

from the production process and does not invest it in

productive ways then does not an Intervention in the

marketing organisations lead to a consciousness of

how society operates and, thence, an attempt to control

the environment?

22

We shall end this paper by noting that the concepts

of environmental planning'presented here differ in many

details and definitions from what is commonly accepted

by institutional structures but we have tried to estab

lish the rationale of why we differ. Since the concepts

are new the methodological tools are -also to bo evolved

anew so that analytical treatment of data may be

possible with different biases.

We are .on new ground

and it is best that we are sure of what is under our feet

before we take the next step. '■

.

‘

List of references

1. Lincoln Allison; Environmental Planning; a political

and philosophical analysis; George Allen & Unwin

Ltd-. 1975.

2. 8.No Juyal; Area Development Planning; Concepts, methods

and practices; seminar paper, 1976.

3. Rajni Kothari; an outlook for India’s future (2000 a.D.)

a Interim report on rural development;NCST, 1976.

C. Subrauaniam; Strategy for Integrated Rural Develop

ment; Govt, of India, 1976.

5. K.N. Raj; Growth and Stagnation in Indian Industrial

Development; G.L.Mehta memorial lecture,Bombay,1976.

J.

6. C. DeFonseka; The Man-Land relationship and Agrarian

reform

in China; seminar paper, Colombo, 1976.

<

•

7. Commerce, August 18, 1973.

•

•

•

c

8. Financial Express, August 9, 19739. .LJo Chancellor & J.R.Goss; Balancing Energy and Food

Production,1975-2000; Science, Vol.192, 1976.

10. Times of India; selected news items on Industrial

•policies and data.

11. Economic and Political Weekly; selected data from

19 Companies'®.

•

•

■

12. Sone aspects of the study of a multistructural society;

unpublished manuscript.

13. Mo Naveed; India; The June’76 budget;Imprecor,no.51,May,76.

1^. India’s Health Dilemmas and Us; Hole of Ideological and

Political Factors; seminar paper, 1976.

15- Communist Party of India(Marxist);Central Committee

Meeting, Jun. 1976.

16. Appropriate- Technology Development Association;Statement

of objectives; Lucknow, 1976.

17‘. Rose Terrill; Flowers on an Iron tree; Five cities of

forthcoming publication, 1976.

< * China;

•

18. David Zwick & Marcy Benstock; Bater Nasteland;Bantam,

1971.

19a Robert arvil.L; Man and Environment5 Pelican, 1967/

.

•

* •

•

20o Geor.ce Dalton; Economic Systems and Society; Capitalism,

Comminism and the Third. Norid; Penguin, Modern ‘Economic

Texts,

• •

21. C.c.^Fonseku; Tachai; seminar paper, 1975*

2d Lim Tech Ghee; Technology and Culture* in Southeast

• zisius In search of a now balance; project paper,

University Sod ns, Malaysia, 1975«

23o BoNo Juyal and Vikasbhai; Response to Technology and

Culture in Southeast Asia; Varanasi, 1975-

24. Narayan Chandra; Plan for Social Change; seminar paper,

Varanasi, 1976.

The Shahdol Group

July,1976.

c

cowi^1’r'

B°ad

67'A'^So^-5eo0°1

AIMS AM~ POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF WATER S UPPLY IMPROVE ’TENTS

Dr. SV. Rama Rao*

There is urgent need for understanding the health

aspects in water supply and a programme launched for such a

purpose must bestow top priority for health education regardino

the importance of water. This education is important for not

only the community but also the administrators and aoencies

■involved in providing water supply to the community.

/O% of our body is made up of water in the tissues

and-water is an universal solvent and but for its role,

metabolic activities would come to a stop and life would not

be possible.

The developed countries are fortunate since they do

not have the problem of finding resources.

From thic-r standards

providing water does not cost much and people can afford to pay.

All they want is water should be readily available in abundance.

The water provided thus is of a quality which has minimal risk

of health hazard and people tend to take things for granted and

they may not look at the Health aspect critically.

India is a vast country and reswrces are poor.

People themselves are often too poor to pa/ for water and

specially so for a filtered safe water supply in their homes.

• Governments, Agencies - private and public including

Plantation management who provide funds for supply of water to

Community under their, care nec-d evidence of health benefits for

their financial investment on a Water supply project.

Funds are provided for a project of safe water

supply and it is too meagre for an ideal one. Alternatives

have to be thought of.

Improvements and innovations are called

for.

Few people get excellent water and a majority have either

no water supply worth its name or they are substandard.

Diseases•related to water supplies are numerous and

distributed over a vast area. Decreasing the incidence. and

prevalence of these- diseases is-one of the important priority

goals in any public health undertaking in our country.

The indirect effect of lack of a protected water

supply is reflected in our health indicators which compares

very unfavourably with those of developed countries.

*Prof. & Head ,

Dept. of. Community Medicine,

St.John’s Medical College,

Bangalore - 560 034.

C'

2

Table - I*

Some of the Health Indicators in

India compared with USA.

CDR

IAR

.

MMR -

•

Life Exp.

INDIA

USA

15.0 (1976)

9.4

122 (1971)

18.0

3.6(1976)

0.18 (1972)-

56.6 years

70 years

uur or ±0uu rive birros 25V *or

co not reacn their

‘5th’ birthday.

150 of these do not even rea:h their first birth

day. The wastage of human life is enormous and if we analyse

the dauses we find that water related diseases account for many<

Engineers and Administrators need to have a very clear

understanding of these facts and figures to appreciate the

enormity of the problem and the importance )f providing adequate

funds on a priority basis for water supply scheme. A large

amount of misery, sickness and deaths related to water supply

can be prevented by household tap systems o: water supply.

Th-e World Health Assembly in 1972 has set a new

target - n25% of the rural population in de/eloping countries

to have reasonable access to safe water supply by 1980”.

Reasonable defined as dis proportionate part of day not spent

in water fetching,

At present 86% of the rjral population in

India do not have reasonable access i

Cons Lderc-d by Region,the numbers and percentages of people without reasonable- access

to safe water supply were as follows:

Table - II*

•

Population

% without reasonable

access to safe water

Africa

136.0 mil.

89

America

92.1 mil.

Region

76

•

Eastern Meditaranian

Europe (/\lger ia

JVbroces & Turkey)

139.5 mil.

••

82

South East Asia

666.7 mil.

91

Western. Pacific •

59.0 mil.

79

1111.6 mil.

86

All Regions

I

•

^“Source: Water, Wastes and health in hot climates.

— •* —v». r

•• •■...... '

....... ' . .

;. .

.; •

3

,

.. .TV? problem of population explosion in the'

oeveloping countries makes the situation worse 1

Merely to

keep.the- unservec population-constanti.t is?necessary to

provide water for a population equal to 5 times the population

of United Kingdom (28G million by 1980).

This can be described

as the everworsening situation, .or as"crisis. “

For majority of the World population there is no

possibility that the needed financial and human resources for

providing an ideal water supply would be forthcoming.

Efficient and rational allocation of financial and

human resources, planning for water supply development with

closely defined and agreed objectives sc that scarce resources

may be utilised to the best advantage appears to be the only

possible solution.

*

rational planning presupposes closely defined and

agreed objectives.

We do not have any at present for the- low

income communities.

These objectives could be set forth having

in view the short term aims and benefits as also long term aims

and benefits.

.

Table..- Ill*

•

•

•

f

Aims and Potential Benefits of -Water

Supply Improvements.

Immediate•

Aims

•'

■ ■■

■■■

•'

■■

• •• Stage I

benefits'

Stage. II ...

benefits'

. Stage III

benefits

1 *

• " • ■ j”:

Improved water

........

. Save time ’”

Higher cash

.incomes

Increased and

more -

Quality

Save energy

Labour release

. /.

Crop innovation

Quantity

Improvedhealth

Crop improve--... Reliable subsistence

ment

/Availability

Animal

husbandry

Anirpal hus

bandry

innovation

Improved health

Animal husbandry

impr ovement

Increased

Ic-isure

liability

At one of the spectrum’of immediate- aims we have in

mind a high grade water ..sc.rvice... for •_a prosperous community, to

provide water of high quality,- abundant in quantity, complete

availability and total reliability and at rhe other end we have

communities with no water s.uppiy^of any sort worth mentioning.

In between we have various and different grades.

V

.1

The- Low Income- Communities while they cannot afford

the high grade water service which is unattainable, must think

of some combination of improvements.

•■‘Source : WaterWastes and health in hot climates

...4

4

The potential benefits of each type of water supply

needs to be examined with a view to assess- the degree to which

different improvements will realise different levels of benefits.

This will enable one to know the improvements with the most

impact, at a given cost and the anticipated cost-effectiveness

of alternative schemes can be compared.

it can be seen from the table III that the benefits

from Stage I to Stage III are arranged chronologically and the

complementary development inputs and inititatives required at

each stage are indicated in Table - IV.

Table - IV *

Complementary inputs necessary for the

achievement of the various aims and

benefits set out.

Aim or benefit

Complementary inputs or prerequisite

conditions

Immediate aims

Active community participation and

support.

Competent design

Adequate facilities for operation

and maintenance.

Appropriate technology utilized

Stage I benefits

New -supply used in preference to

old.

New supply closer to dwellings than

old. ’ •

Water use pattern changed to take

advantage of improved quantity^

availability and reliability'

Hygiene changed-to utilize improved

supply.

Other environmental health measures

taken

Supply must not create new health

hazards (e.g. mosquito breeding

sites )

Stage II benefits