OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH

Item

- Title

- OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH

- extracted text

-

RF_OH_3_SUDHA

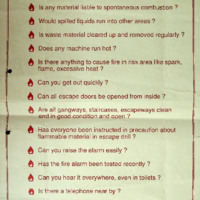

Checklist for Fire

and Explosion Risk

«

;

i

Are flammable materials present in smallest

possible amount ?

(2) Is any material liable to spontaneous combustion ?

Would spilled liquids run into other areas ?

Is waste material cleared up and removed regularly ?

Does any machine run hot ?

Is there anything to cause fire in risk area like spark,

flame, excessive heat ?

Can you get out quickly ?

Can all escape doors be opened from inside ?

Are all gangways, staircases, escapeways clean

and in good condition and open ?

H Has everyone been instructed in precaution about

flammable material in escape drill ?

Can you raise the alarm easily ?

ife Has the fire alarm been tested recently ?

Can you hear it everywhere, even in toilets ?

Is there a telephone near by ?

Are there enough fire extinguishers ?

Are extinguishers checked regularly and maintained ?

Are fire alarms working ?

ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW OF INDUSTRIAL PROJECTS EVALUATED BY

DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

By Barry I. Castleman and Grace E. Ziem

Any developing country can require every foreign investor to submit as part

of the application to build industrial factories, mining operations, and other

industrial projects in the developing country, the necessary information on the

possi ble harm these projects m ay cause to the health ofdeveloping country workers

and people living in areas where the industrial projects would be built.

Another objective is to assure that these operations will achieve high

standards ofperformance; speci fically, the developing country government will be

provided with equipment to assure that workers’ exposure to health and safety

hazards does not exceed specified limits, and that releases of toxic substances into

air and water and onto land do not exceed limits specified in the

cooperative investment agreement between the developing country and the

foreign investor.

Leading global corporations, have issued policy statements on health, safety,

and the environment within the past year. One theme of these policy statements is

that the companies now say they will meet the same high standards worldwide that

they are required to achieve in their home countries in all new projects.

INFORMATION FROM FOREIGN INVESTORS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW

A.

The foreign investor shall provide an Environmental Impact Analysis of the

proposed project,including:

3)

allegedly sustained by workers, including workers’ compensation claims;

explanation of all fines, penalties, citations, violations, regulatory agree

list of all raw materials, intermidiates, products, and wastes (with flow

ments, and civil damage claims involving environmental and occupational

1)

diagram);

2)

health and safety matters as well as hazards from or hann attributed to the

list of all occupational health and safety standards and environmental

standards (wastewater effluent releases, atmospheric emission rates for all

air pollutants, detailed description and rate of generation of solid wastes or

marketing and transport of the products of such enterprises;

4)

other wastes to be disposed of on land or by incineration);

3)

4)

equity partners and providers of technology;

plan for control of all accupational health and safety hazards in plant 5)

environmental and occupational health and safety for each plant location;

products, and wastes;

6)

copy of corporation guidelines of the foreign investor for conducting envi

subjectof controversy within the local community or with regulatory authori

manufacturer’s safety data sheets on all substances involved.

resolved in each case;

audits and reports by consultants;

8)

copies of safety reports, reports of hazard assessment, and risk analysis report

carried out with similar technology by the foreign investor and its consult

processes and products are used, including:

list of all applicable occupational health and safely standards and environ

mental standards, including both legal requirements (standards, laws, regu

copies, with summary, of all corporate occupational health and safety and

environmental audits and inspection reports forcach location, including such

and performance of existing plants and plants closed within the past 5 years

in which the foreign investor has partial or full ownership, where similar

explanation of cases where any plant’s environmental impact has been the

ties, including description of the practices criticized and how criticism was

7)

The foreign investor shal] provide complete information on locations, ages,

B.

1)

names and addresses of governmental authorities who regulate or oversee

operation, storage, and transport of potentially hazardous raw materials,

ronmental and occupational health arid safety impact analyses for new

projects;

5)

description of the foreign investor’s percentage of ownership and techonol-

ogy involvement in each plant location, and similar information for other

ants.

9)

copies of toxic release forms that have been submitted to governmental

bodies (e.g., the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or similar agencies

lations) and corporate voluntary standards and practices forthe control of oc

in other countries) within the past 5 years, for all plant locations;

cupational and environmental hazards of all kinds;

any information considered relevant by lhe forcign investor.

2)

description of all cases of permanent and/or total disability sustained or 10)

AGREEMENTS ON POLICY

The foreign investor shall submit a statement of corporate policy on health,

C.

proposed project. The foreign investor shall agree that the proposed project

will pay the cost to the developing country' government for all medical and

safety, and environmental performance of worldwide operations. This must

exposure monitoring during the lifetime of the proposed project.

include the corporate policy on laws, regulations, standards, guidelines, and

practices for new industrial projects and production facilities. The foreign

G.

the staff responsible for carrying out this policy,

harmed as a result of lire project’s occupational hazards and

its authority and

responsibilities, and its position in the foreign investor corporate structure.

Such descriptions will also include the name, address, and telephone

H.

function. The foreign investor shall state whether it follows the same

standards worldwide for worker and environmental protection in all new

E.

F.

environmental

impacts, as determined by the government of the developing country.

The foreign investor shall follow marketing safeguards as restrictive as

those it applies anywhere in the world, to assure that workers and members

of the public arc not harmed as a result of the use of its products.

number of senior corporate management officials in charge of this staff

D.

The foreign investor shall agree that the proposed project will fully

compensate any person whose health, earning capacity, or property is

investor shall explain how its global policy is implemented by: describing

I.

projects; and if not, explain why not.

The foreign investor shall agree to provide the developing country immediate

If the foreign investor becomes awarcof asubstanital risk of injury to health

or the environment from a substance it manufactures or sells in the

access to the proposed industrial facility at any lime during its operation to

developing country, a risk not known and disclosed at the time of this

application, the foreign investor agrees to notify the environmental protection

conduct inspections, monitor exposure of workers to hazards, and sample

agency of the government of the developing country immediately of such

for pollution release.

The foreign investor shall agree to fully train all employees exposed to

J.

potential occupational hazards, including potential health effects of all

Substances Control Act of the U.S.A.)

The foreign investorshall provide the names, titles, address, phone, and fax

exposures and the most effective control measures.

The foreign investor shall agree to provide the developing country with

equipment to analyze workplace exposures and pollutant generation, including

but not limited to all limits specified in A.2) above, for the lifetime of the

risk. (This is similar to requirements under section 8c of the Toxic

numbers of its senior corporate officials charged with implementing envi

ronmental and occupational and safety and health policies including plant

design and operations, corporate inspections and reviews of plant perfonnance, and product stewardship.

REFERENCES

i.

2.

3.

1C1 announces corporate policy ol “uniform environmental standards lor all new plants worldwide and a comprehensive waste recycling policy”, (Chemical

Week. December 5. 1990)

Dow Chemical announces corporate policy to “ensure Dow facilities from Midland (Michigan. USA) to Malaysia operate under the same environmental

and safety standards... based on those of Dow’s U.S. operations", {chemical Week, October 17. 1990)

Castleman, B. “Corporate Standards Applied Internationally”. Global Development and Environment Crisis: Has humankind a Future? Asia-Pacific

People’s Environment Network, Penang. Malaysia, pp. 397-399, 1988.

Ref: Published in "NEW SOLUTIONS" Summer 1991 Page No. 75-76

•

'*

FrEH

NEWSLETTER

July-August, 1987

Vol. I

No. 5

Occupational Health: Some Issues

Vijay Kanhere

“ALMOST all the agents that have been recognised as be

ing carcinogenic in humans, have been identified as such

in the occupational setting”,—Encyclopaedia on occupa

tional health and safety by the ILO.

The greater the number of chemicals used in industries,

the greater are the number of affected persons. The ef

fects of chemicals in their acute form are obvious.

Thousands of persons affected due to MIC in Bhopal,

posed a grave problem to community health. And what

about the workers in the factory, who were slowly and

regularly being affected not only by MIC, but also by

other chemicals like phosgene? Are not the workers also

a part of the community?

Let us take the example of silicosis. It is usually treated

as tuberculosis. This has happened in Mandsaur in

Madhya Pradesh and Baroda in Gujarat. Workers in

Alembic Glass Works had to struggle for being treated

as patients of silicosis. What is the effect of these patients

on the community? Their lungs are affected, their

resistance to disease goes down and they readily contract

tuberculosis. This increases the occurrence of TB in their

families and the community.

Noise pollution in the community has been widely

discussed. It was a topic dealt with in a popular televi

sion serial as well. However, what is hardly ever mention

ed is that workers are day after day, for years attacked

by noise—in the textile mills, in engineering units, on

boilers, compressors... As the hearing capacity of

workers gets affected, apart from many serious possible

accidents, their irritability increases. Within the family,

it creates tensions. Everybody has to speak up so that the

affected worker.can understand. He/she too judges the

capacity of others from his/her or own and so starts talk

ing in a louder pitch, which irritates other family members

in turn.

There are carry-home diseases such as asbestosis.

Chemicals reach homes through overalls, clothes, un

washed body parts and they affect family members. One

ESIS doctor informed us that the majority of the cases

he treats are those of dermatitis, induced by exposure to

chemicals.

No longer can one think of occupational diseases as

an exclusively urban problem. In Punjab and

Maharashtra, there are areas where insecticides are sprayed

aerially by helicopters. These insecticides affect

agricultural workers and farmers. Chemicals used in

agriculture are increasing at a fast rate. In rural areas,

where residential areas and work-places are not sharply

differentiated, the effect of these hazardous substances

are going to be all the more.

The National Commission on Labour in its report in

1969 commented, “... the slow and agonising process of

an occupational disease may not stir the community as

much as it would in countries with chronic labour shor

tage, although to the near ones, it is a tragic occurrence.

Relief gets organised soon after the event, but prevention

gets side-tracked”.

However, in countries like India, relief too takes a very

long time. The Bhopal disaster made national and inter

national news. However, almost 7 months after the

gruesome event, conscious doctors had to move the

Supreme Court merely to get the supply of the proper

medicines. (Dr. Vohra Vs. the State, 1985). Even in a

metropolitan city like Bombay, relief has not been effec

tively organised even in cases of chlorine leakages.

In fact very often it is even difficult to get diagnosed.

as a victim of an occupational disease. Workers suffering

from asbestosis even in cities like Bombay, have to go

through a tiresome process merely for being diagnosed

properly as patients of asbestosis.

There are various reasons for this state of affairs".’ For

one thing, any talk about health and safety at the

workplace is seen as a direct threat to the profits as well

as to the power of the management. This also relates to

the lack of political will to take the health of the workers

seriously. This reflects in the content and approach of the

curriculum in medical colleges. Thus even the knowledge

about ‘notifiable diseases’ is absent with most doctors,

including those working in industrial areas.

This is glaringly brought forth in the fact that from the

year 1960 to 1980, there was not a single case reported

of 11 out of the 22 ‘notifiable diseases’. In this period only

30-32 cases of diseases have been reported per year, while,

with a much better technological set-up in the factories,

almost 20,000 cases of asbestosis are reported each year

in the US despite better preventive measures.

From this it is obvious that the doctors can and must

play greater role in learning about, diagnosing and repor

ting various industrial and occupational diseases. It is also

necessary to make this information available not only to

the industrialists and government agencies but more im

portant to the workers themselves, their relatives and the

public at large especially the poor who are most exposed

to these hazards. This is one important weapon to stop

the mindless and inhuman maiming of lives in this

country.

FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION ONLY

To

The FRCH collective,

I acknowledge, with thanks, the receipt of the BiAnnual Report of your Foundation and the latest issue

of FRCH newsletter.

Both these publications bear your stamp and put forth

loudly and clearly the messages that need constant re

emphasis in our country.

I must confess that I cannot agree with all that is said.

Working, as I do, in a public hospital, full time, I see the

need for such hospitals and for specialities such as mine.

The poorest need excellent service no less than do the wellto-do and I feel that it is imperative that we keep our

public teaching hospitals in the forefront of patient care.

Unfortunately, these days it is the 5 star hospitals that are

in the forefront, whilst the public hospitals are starved

and downgraded.

Whilst there is no dispute regarding the need for effi

cient measures to improve public health, prevent disease,

educate the population at large and generally do all that

is possible to improve the economic status of the villagers

in particular and labourers in general, I see the ill effects

of these being pitted against development of the large

teaching hospitals. I feel that this is wrong. BOTH NEED

ATTENTION, DEVELOPMENT.

Sunil Pandya

Neurosurgeon

E.M.

K.

Hospital

Bombay

Notes from Medical Journals

Mukund Uplekar

Is our pursuit of a healthy body—a major threat to

health?

Ivan Illich, a long time critic of the medical establish

ment no longer views doctors as the major threat to

health. He has discovered a far more dangerous pathogen

the pursuit of a healthy body. Once again we have found

the enemy and once again he is us. Complacently we have

stood by while a multimillion'“health industry” has taken

over, offering advice and handholding to the fibre eating

health magazine readers whom the doctors are too busy

to see. These new pseudoscientist healers diagnose yeast

cells in the blood as a cause of your tiredness, and cure

it with a garlicky remedy that only they sell. They analyse

your hair to find out which mineral or vitamin you need

to buy from them. They measure your body fat by pin

ching you with calipers; determine your skin’s resistance

and electro-magnetic balance with galvanometers; and

perform stress tests, conveniently combined at health clubs

with a massage, a sauna, or the whirlpool. Various “Car

diovascular” exercises are carried out perched on a sta

tionary bicycle while hooked up to a pulse monitor that

lights up as you reach the top of an imaginary hill.

How harmful are these practices other than wasting

people’s money? Illich rails against these “sundry holistic

well-being programes” this “curious mixture of opionionated and detailed self care practices”. He thinks this

mumbo jumbo could cause even more harm than 100,000

patients being seriously injured each year by

hospitalisation.

Antibiotics in Antidiarrhoeals

In ‘Antibiotics: the wrong drugs for diarrhoea’ Health

Action International draws attention to the WHO state

ment that “antimicrobial drugs are not indicated for the

routine of acute diarrhoea”. Health Action International

claims that spending on antidiarrhoeals (nearly $ 150

million a year) diverts attention and resources from oral

rehydration which is a lifesaving treatment.

Products containing neomycin, streptomycin, chloram

phenicol and sulfonamides are singled out as being the

“worst of a bad lot”. For example, widespread and irra

tional use of streptomycin has led to the development of

bacterial resistance to the drugs for the treatment of tuber

culosis. And despite the well recognised risk of bone mar

row suppression, chloramphenical is present in 12

products.

Of the 12 regions surveyed, only Hong Kong has

stringent regulations to prevent the registration of an

tidiarrhoeals containing an antimicrobial. The report will.

be sent to health ministries, drug regulatory agencies and

medical schools around the world.

Interaction Between the Government, NGOs and the

Private Sector in Implementation of HFA

Abhay Bang

■ .Ideological basis of cooperation: The cooperation can the NGOs assume, especially if they want to increase

between the government and the NGOs in the health sec their impact by interacting with the government which

tor was always on the basis of common ideology and alone has the political responsibility and resources to pro

interests. Thus different categories of NGOs were col vide HFA?

The following roles may be posible

laborating at different times with the then ruling govern

1.

Research and Innovation

ments. Christian missions were actively cooperating with

2.

Demonstration

the British rulers with common imperial interests. The

3.

Training

Gandhian constructive institutions were active in col

4.

Evaluation

laboration with the Congress government with their com

5.

Building public opinion for changes in

mon roots in the freedom movement and ‘Congress’

government policies.

ideology. The gates were opened for the voluntary agen

While the last one is not cooperation with the govern

cies with closer links with the ‘opposition’ parties (when

these came into power under the name of Janata Party) ment in the narrow sense, this role is extremely impor

by allowing a major role to NGOs in the National Adult tant. The history of public health is studded with examples

Education Programme. Now with the free market ideology as to how this role has greatly improved the government

of the Rajiv Gandhi government, the private sector shall policies and programmes. The Sanitary Movement in

have more role. The talk of social marketing, of delegating Great Britain in the 19th century or the work of the en

the responsibility of advertisement of the national pro vironmentalists today are glaring examples. However, the

rest of the discussion in this paper does not include this

grammes to private agencies are a few examples.

Where do the NGOs in the health sector ideologically type of role.

stand today? Inspite of their tremendous diversity and dif 3. Issues in Government-NGO Interaction: In any work

ferent religious or economic roots, most of them explicitly ing together,compatibility on the following points is im

or implicitly believe in the welfare state with a mixed portant, and hence needs attention.

1. Ideology and Goal

economy. Obviously they do not find- any major

2.

Objectives (specific)

ideological problems in collaborating with the various

3.

Organisational structure and culture

governments in India. Even those who profess to have a

4.

Procedures and rules

radical ideology usually do not have problems in

5.

Personalities

cooperating with the government as long as they can con

6.

Finance

tinue to attack the system while retaining their safe posi

The ideology and the goal being similar, these don’t

tions in the urban universities and institutions. Many other

grass root workers or activists strive for limited reforms pose much problems in the actual working together. But

by opposing govern.ment policies; and yet in the long run the different emphasis due to the different objectives may

they too work with the government as their reforms are pose a problem. Down in the field, primary health care

seems to be reduced to fulfilling targets of a few vertical

accepted.

Thus most of the NGOs today have no major programme objectives. Family planning (FP) tops the list

ideological barriers for cooperating with the governments with immunisation and blindness control coming next.

Rest of the programmes or indicators like infant mortali

in India.

2 Role of the NGOs: Inspite of hundreds of failures of ty count little. The NGOs may have different or broader

implementation, the National Health Policy is more pro objectives and hence a tussle for priority may ensue. A

gressive than most of the NGOs. At least at the concep NGO may not be willing to go all out for the numerical

tual level, the Primary Health Care is oriented to preven targets of FP while for the government health officer, it

tion, outreach and use of paramedics, while most of the is a sacred cow.

There is a contradiction in the structure and function

NGOs are still curative oriented, running charitable

dispensaries or hospitals or diagnostic camps. Gone are of the Primary Health Care strategy. The National Health

the days of Albert Schweitzer or Father Demain when Policy has abandoned the unipurpose organisational

such individuals or NGOs outreached where no govern structure. Now we have buildings and a large number of

ment care reached. The most important outreach agen health workers so that an organisational basis is created

cies today are the government or the private practitioners. for continuous and comprehensive health care. And yet,

Thus in Gadchiroli district which is probably the most the health programmes are still conducted in the form of

difficult district in Maharashtra, there are 3 NGOs in campaigns which need a mobile structure and large scale

health, 34 PHCs, with 230 subcentres and 700 CHVs and propoganda rather than buildings and accessible workers.

about 300 General Practitioners (including Registered

In its relationship with the government organisation a

NGO is likely to face what may be called the ‘middle level

Medical Practitioners).

A recent study by FRCH on the NGOs in health in constraint’. At the top, the officers can take a broader view

Maharashtra concluded that the NGOs are concentrated about cooperation. The bottom level functionary may be

in the developed districts rather than the backward areas. happy to work with a.NGO because of more humane and

With the tremendous expansion of the government

health sector or the private practitioners, what new role

(continued on page 8)

Industrial Accidents: Whose Life, Whose Responsibility?

Sujata Gothoskar

are not really ‘accident’al at all) and this cause can be and

has to be pinpointed and removed. This process of pin

pointing and removing the cause of industrial accidents

and occupational diseases has important implications.

EVERY five minutes, one of the world’s workers is killed

and fourteen permanently disabled as a result of accidents

at work or occupational diseases, according to an estimate

by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). In In

dia, over the 30-year period from 1950-1980, 36,000

workers have been reported killed and 6.4 million injured

in accidents at work in the factories in the organised sec

tor, mines, ports, docks and railways alone. The number

of workers killed or maimed in the unorganised industry

can only be a guess. And over the years, statistics indicate

that injuries due to industrial accidents continue to

increase.

The number of fatal accidents has risen by 225 per cent

in the last 30 years, from 248 in 1950 to 806 in 1980. Nonfatal injuries, equally dangerous *, have been rising even

more rapidly, from 76,000 in 1951 to 355,000 in 1980—a

393 per cent increase.

Increase between the years 1950 and 1980

Increase in average daily employment

Increase in fatal injuries

Increase in non-fatal injuries

120 per cent

225 per cent

393 per cent

Number of fatal injuries per million human hours worked

Countries

number in

1979

1980

U.S.A.

U.K.

Japan

Yugoslavia

India

0.03

0.03

0.02

0.07

0.15

N.A.

0.03

0.01

0.08

0.15

To begin with, it puts a halt to deaths and mutilations

of more workers. Secondly, it asserts that workers have

a right to work without their lives or well-being being

jeopardised. Thirdly, it gives workers the right to know

and act in favour of their own safety according to the

knowledge they have gained about the work process. Four

thly, it makes a political statement about the primacy of

workers’ safety vis-a-vis either management prerogatives

or the blind profit motive.

An international comparison also indicates that acci

dent rates in India are exceptionally high. It is difficult

Theories of Accidents

to compare statistics for non-fatal accidents since criterion

The standard explanation for most accidents is that they

for reporting are different in different countries, but fatal

are due to either unsafe mechanical or physical conditions,

accidents can more easily be compared.

or unsafe actions, or both. However, the actual causes of

The figures for India are based on accident reports accidents cannot be attributed simplistically, but are much

received by the Factory Inspectorate, and therefore relate more complex, especially, if ‘unsafe actions’ are attributed,

only to ‘reportable’ accidents, i.e. those which lead to an as they usually are, to workers.

absence from work of two days or more.

For example, one could consider the accident at Union

Moreover, it is well known that even reportable ac

Carbide, Bhopal, in which Ashraf Khan was fatally in

cidents are very often not reported by employers, as they

jured. He was splashed with phosgene while opening a

wish to avoid paying compensation or getting prosecuted

pipe for maintenance work, panicked and removed his

for non-compliance with the law. And the law does not

safety mask before decontaminating himself, inhaled a

even cover construction workers or workplaces with power

fatal quantity of the toxic chemical and collapsed. The

employing less than 10 workers and workplaces without

management took the position that it was his unsafe

power having less than 20 workers (and most contractors

take care not to have more than 19 workers on any one action—removing his safety mask—which resulted in his

death. Yet the fact is that the pipeline was supposed to

site), so that soTne of the sections, which are subjected

have been properly evacuated and put under vacuum, ac

to most hazards—in small-scale industry, construction,

contract workers, etc,—are not included in accident cording to the company’s own laid-down procedures. The

pipe-line should have been empty. Ashraf had no reason

statistics at all.

Finally, these figures do not include the enormous to think he would be splashed with phosgene, and in the

number of people who are killed or disabled by oc circumstances, his panic was an entirely normal human

cupational diseases. Taking this into account, it appears reaction. Thus to say that this accident was due to both

that a significant proportion of the total working popula an unsafe action and an unsafe condition is really to

tion suffers from some form of injury, upto and including misrepresent its cause. If the design and processes can

fatal injury, due to occupational hazards. In short, the not pre-judge and plan according to entirely human

responses of the moment, clearly such designs and pro

situation is appalling, and it is getting even worse.

This points to the extreme urgency of monitoring ac cesses are at fault? As the safety manager at Siemens put

cidents. This is of course not an easy task. Nevertheless it, ‘the work place and work processes have to be not on

most accidents cause immense misery to workers and their ly full-proof, but also fool-proof. Even ‘deliberate ac

families and most accidents have a clear cause (i.e. they cidents’ should be planned against in the original scheme

itself. One did not even ask for that much in the Bhopal

case.

‘Every non-fatal accident has the potential to become a

Again, take the finding that contract workers have a

fatal one the next time it occurs.

higher incidence of accidents, especially fatal accidents.

For example, in a petroleum plant in Bombay, a contract

worker, working in a pool of liquid which he believed to

be water, threw a lighted match into it, it turned out to

be oil, however, and he was burnt to death. This would

be considered a clear case of an unsafe action but the

cause of the accident was ignorance on the part of the

worker. Thus to say that the cause of this accident was

an ‘unsafe action’ would be completely erroneous, because

to use untrained and uninstructed workers for work with

hazardous chemicals is to create an inherently unsafe

situation.

cident Prevention’ Industrial Safety, Health and Welfare Cen

tre, Central Labour Institute, Bombay)!’

If the accident proneness of a few individuals is not

responsible for most accidents, are there other factors

which are within the control of workers? Could there be,

for example, self-infliction of injuries in order to get timeoff from work? Or could a large number of accidents be

due to the carelessness of workers?

Of those interviewed, not even management represen

tatives thought that such causes could account for a

significant proportion of accidents. Nor does it seem likely

There are unlimited instances, indicating the fact that that workers would court death or mutilation if they could

it is absolutely necessary to go beyond the superficial avoid them. Most of the accidents are such that even if

the actual injury is minor, it could easily have been much

category of ‘unsafe action’ and investigate why the un

worse—and therefore to inflict it on oneself would involve

safe action took place.

incurring the risk of serious injury or disablement. Our

Another theory explaining the occurrence of accidents, investigation shows that where workers do take such risks,

attributes the majority to a few individuals who are it is for reasons beyond their control—e.g., because the

predisposed to have a high rate of mishaps. At three places work-situation itself forces them to do so, because they

out of twenty where we obtained interviews, one worker are ignorant of the dangers, because they are asked to do

was identified as a victim of repeated accidents, and in jobs for which they are insufficiently trained, and so forth.

a tyre factory and in the docks, there were a few such

On the other hand, the conditions and actions which

workers. But in most places, there were no such ‘repeaters’, routinely lead to accidents are within the control of

and even in cases, where a few workers repeatedly had ac management; and it is in recognition of this that most

cidents due to drunkenness and negligence, they were far modern health and safety legislation lays the responsibility

from accounting for even a significant proportion of the for providing a safe and healthy workplace on the

employer.

accidents.

This article is based on discussion and research work

Our findings were confirmed by other studies:

“Numerous studies carried out by research workers have fail done for the Accidents bulletin: No. 10, of the Union

Research

Group, Bombay and the several discussions with

ed to prove conclusively that any group of persons in a given

sample can be separated as accident-prone. Dr. Schulzinger, Rohini, Vijay, Ram and Jairus, and going through their

after careful study of 35,000 injury cases,... suggests that notes and jottings.

most accidents are due to the relatively frequent solitary ex

perience of a large numer of individuals. The total number

of accidents suffered by those who injure themselves year

after year... is relatively small... Professor Edwin E.

Ghiselli... advises that the term accident proneness should

never be used in studies of the causes of accidents and in

juries, as it is according to him “dangerous and misleading

and contributes nothing of practical value to our understan

ding of the causes of industrial accidents and injuries”. (‘Ac

References

R.R. Nair, Workplace accidents are increasing, Science Today, September.

1982.

K.C. Gupta, Challenges in the area of Occupational Safety and Health

in the coming decade, paper presented at International Congress on

Safety, Health and Environment, February, 1987.

H. Ganapathy, Prevention of accidents in building construction, Central

Labour Institute.

Ban EP Drugs: An Appeal to SC

Ravi Duggal

The hearing of the Public Enquiry commissioned by

the Supreme Court (SC) regarding banning of the

highdose Oestrogen Progesterone (HDEP) combination

was held on 14th July in Bombay. Like the earlier three

hearings in Madras, Delhi and Calcutta it was also a farce.

The very nature of the enquiry needs to be questioned.

The SC must look into this matter seriously because this

sort of an enquiry is the first of its kind and is going to

form a precedent. And a bad precedent would be both

unjust and dangerous.

First of all the Drug Controller (DC) cannot constitute

the authority to sit over such a hearing because it is par

ty to the decision-making process (in this case banning

or continuing the production and sale of HDEP). Given

the political economy of our country, aptly illustrated by

the Justice Lentin Commission’s exposure of the Drug Ad

ministration of Maharashtra, the impartiality of the DC

office cannot be assumed. The pharmaceutical industry

is too powerful a lobby and the DC authority is highly

influenced by the former. This was too obviously apparent

during the proceedings of the various hearings.

The SC should also question the manner in which the

concerned drug companies have gathered evidence in sup

port of HDEP, when internationally its hazards are well

recognised. It was amply evident during the hearings that

most gynaecologists and other medical and phar

macological experts who submitted in favour of the drug

companies did so for reasons other than their own belief,

practice and conviction. The written submissions given

by many gynaecologists and doctors are mere signatures

on standardised statements obviously circulated by the

drug companies.

to hunt around to gather proof for this. It is well known

and documented. The Lentin Commission has adequate

ly exposed the misdeeds of both the drug companies and

the Drug Administration. The dangerous and misleading

practices indulged by the medical profession in India to

make a fast buck are well known. General Practitioners

will administer injections, tonics, steroids and antibiotics

for ailments like headaches and colds or give an in

travenous drip of calcium gluconate to a patient complain

ing of tiredness. Gynaecologists will reconstruct hymens

to reassure virginity, conduct sex-determination tests, help

preselect sex of foetuses and do ceaserians and hysterec

tomies even when not required.

The prescription practices of an overwhelming majority

of doctors is largely unethical and irrational and this is

the danger that concerned people supporting the ban of

HDEP fear most because HDEP is being grossly misused

by doctors, like many other harmful and also relatively

harmless drugs. I will not go into the misuses and hazard

of HDEP because a lot has already been written and

documented about this.

What should the supreme court look into? First of all

it must scrutinise the adequacy and fairness of the enquiry.

The general experience of the hearings has been that the

fundamental basis of the enquiry was faulty and therefore

the enquiry invalid. More thought needs to go into for

mulating the structure and nature of the enquiry. The SC

must review this seriously because we don’t want a poor

and unjust enquiry to become a historical precedent. The

SC must assure impartiality and justice—a properly con

stituted unbiased enquiry commission, that seeks indepen

dent evidence and is not an interested party to the deci

sion, somewhat similar to the Justice Lentin Commission,

should do an adequate job.

Further, the entire focus of the public enquiry has been

The SC should also immediately put into effect the

on technical issues relating to HDEP and the clever use

of legal loop-holes. The DC and the drug companies, as earlier ban of HDEP that was made by the government

well as their supporters, have completely ignored social on the recommendation of the Indian Council of Medical

realities that are crucial in making decisions concerning Research, the premier medical research institution in In

human lives. The panel conducting the hearing compris dia. When many developed countries after bitter ex

ed only of “technical” persons from the DC’s office. No periences have already banned or withdrawn HDEP on

social scientist, lawyer, gynaecologist, or representative of grounds of well known health hazards, associated with

consumer and civil right groups were, there on the panel. the drug then why wait for further evidence to ban the

Worse still no woman was represented on the panel. Isn’t drug. Do we want another thalidomide type disaster? How

it ironical and unjust that the fate of a drug consumed can the SC and the government permit a known hazar

only by women is being decided by men who’ll never have dous drug to be produced, marketed and consumed free

to experience the hazards of the drug! Why does it always ly in the country? Even an iota of doubt about the harm

happen that any question that involves women’s rights, fulness of drug is sufficient reason to ban it, especially

security and health is treated with neglect, carelessness considering social realities of our country. It is indeed in

and apathy? These shortcomings in itself make the nature human to let loose a harmful drug on an uninformed and

of the enquiry questionable.

oppressed people.

The most important issue that should concern this en

quiry and has totally been overlooked is the nature of

medical practice in India. In general the type of private

medical practice prevailing in the country is grossly

unethical and irrational. The checks and control by the

Medical Council of India and the Drug control Ad

ministrations is virtually non-existent. One doesn’t have

Therefore it is important that the SC in reviewing this

public enquiry should reassess the basis of formulating

terms of reference and assure that social aspects of the

concerned issues are taken into account adequately. And

it is our fervent appeal to the Chief Justice of India to

ban HDEP with immediate effect in the larger public

interest.

PESTICIDE POISONING

Amar Jesani

Pesticide poisoning, including attempted suicide by in

gesting pesticide, is a significant health problem, par

ticularly in the third world countries. In our country

reliable statistics on pesticide poisoning are very difficult

to obtain, although there are some estimates and these

suggest an increase in the number of people suffering from

this problem. Of the third world countries, some studies

are available from Sri Lanka. A survey covering hospita

lised patients between the years 1975 and 1980 revealed

that 79,961 patients were admitted due to pesticide poison

ing, 6083 of whom died. Organophosphate compounds

accounted for 76 per cent of these poisonings. Further,

on analysing data for the year 1979 in this survey, it was

found that 73 per cent of these cases were due to attemp

ted suicide.

From the data of this Sri Lankan survey and others,

certain new and disturbing medical aspects of

organophosphate pesticide poisoning are emerging. The

most commonly seen, and known symptoms include

cholinergic crisis, with miosis, sweating, salivation, etc.

This is treated with high doses of the anticholinergic drug

atropine, cholinesterase reactivators (oximes) and pyridine.

In addition to this acute cholinergic-toxicity phase,

observed in all cases of organophosphorous pesticide

poisonings, some people suffer after two to five weeks of

exposure, from a delayed peripheral polyneuropathy in

volving the distal muscles of the extremities. This syn

drome is also known, though not properly documented

in our country.

Recently, in the March 26, 1987 - issue of the New

England Journal of Medicine, Senanayake and

Karalliedde have described another new syndrome of the

neurotoxic manifestation of the organophosphate poison

ing. They observed,in 10 out of 95 patients (in Sri Lanka),

muscle weakness after 24 to 96 hours after the cholinergic

illness, involving primarily the proximal limb muscles,

neck flexors, certain cranial motor nerves and the muscles

of respiration. The effect on respiratory muscles is indeed

very serious. Seven of these ten patients had difficulty in

breathing and three of them died of respiratory failure.

The authors have called it “an intermediate syndrome”

and the condition does not respond to atropine and

oximes.

This expansion in the clinical profile of the

organophosphorous poisoning has very serious medical

as well as public health implication, especialy in the third

world countries where these pesticides are liberally used,

carelessly packaged and dispensed and are the favourite

of those who want to commit suicide.

Jeyratnam, J de Alwis, Seneviratne R. S., Coppiestone

J. F., “Survey of pesticide poisoning in Sri Lanka” Bull.

WHO, 1982: 60: 615-9.

What is New?

40(5), 194-199, 1986.

Books

WHO Chronicle, “Maternal mortality: helping women off

Flavin Christopher,’ “Reassessing nuclear power: the

the road to death”.—WHO Chronicle, 40(5), 175-83,

fallout from Chernobyl”.—Washington: World Watch

1986.

Institute, 1987, pp.91.

British Medical Journal, “Measuring morbidity”.—BMJ,

Fukuoka Masanobu, “One—straw revolution: an in

294, 263, 31st January 1987.

troduction to natural farming”.—Rasulia: Friends rural Maria Mies, “Why do we need all this? a call against

centre, 1986, pp.181.

genetic engineering and reproductive technology”.—

UNICEF, “Learning together from the Sri Lankan ex

women’s studies Int. forum, 8(6), 553-560, 1985.

perience”.—Geneva: UNICEF, 1984, pp.112.

Robinson Jean C., “Of women and washing machines

Zaidi Akbar S„ “Issues in the health sector in

employment, house work, and the reproduction of

Pakistan”.—Islamabad: Pakistan institute of develop

motherhood in socialist China”.—China quarterly, 10,

ment economics, 1986, pp.20.

32-57, March 1985.

Mitra Ashok and Mukherji Shekhar, “Population, food

Prakash Padma, “Sexism in medicine” (paper for 3rd na

and land inequality in India: 1971”.—Bombay: Allied

tional conference on women studies, Chandigarh.—

publishers, 1980, pp.112.

pp.28, October 1986.

Eastman kodak company, “Information age

technology”.—Singapore: Addison—Wesley, 1986, Barreto Luis (Dr.), “Unemployment among doctors: its

roots in socio-economic development in India”.—MFC

pp.654.

meet, 10, January 78.

India, Government of, “Health information of India:

1986”—New Delhi: Directorate general of health ser Duggal Ravi and Gupte Manisha, “XYZ of sex”.—Indian

vices, 1986, pp.292.

post; 31st May 1987.

Ford Foundation, “Banwasi Sewa ashram (Anubhav: Ex

periences in community health)”.—New Delhi: Ford Awasthi Ramesh and Gupte Manisha, “Our destiny floats

with the clouds”.—Indian post, 14th June, 1987.

Foundation, 1987, pp.32.

Duggal Ravi, “Why population won’t fall”.—Indian post,

Reprints

13th June, 1987.

Fulop Tamas, “Health personnel for health for all”.progress or stagnation (part 1):—WHO Chronicle,

Duggal Ravi, “You can’t blame third world all the

time”.—Indian post, 30th May, 1987.

Books m Brief

Manish Mankad

Indian Council of Medical Research, “Medicinal plants

of India: Vol. 2”.—New Delhi: ICMR, J986, pp.600,

Rs.136/-.

The need for a systematic compilation of data on

medicinal plants in India has been felt by almost all

research workers engaged in the study of medicinal plants.

In 1976, Indian Council of Medical Research published

a first volume comprising of information on nearly 350

species of plants presented in alphabetical order (A to G).

The present 2nd volume extends the same (H.to P). It pro

vides in addition, separate indices for botanical names,

chemical constituents as well as names of plants in English

and regional languages of India. Further, classified lists

of plants according to their pharmacological activities are

furnished in one of the indices. This volume also contains

coloured plates of plants.

World Health Organization, “Concepts of health

behaviour research (Searo regional health papers no.13).

New Delhi: WHO; 1986.

The global strategy for Health for All by 2000 recognis

ed the need for health behaviour research (HBR). Despite

this good start, research efforts in relation to national

primary health care programmes were initially slow in

recognising the need for and committing resources for

social science research. HBR was needed to help reorient

the planning and implementation of primary health care.

(continued from' page 3)

liberal treatment. It is at the middle level where the pro

blem of rivalry and sharing of power arises and hence a

great resistance or even hostility may start.

A maze of procedures and inscrutable rules which are

characteristic of government functioning pose two types

of problems. NGOs often understand the intricacies of

these or can be easily trapped into immobility while

working with these. On the other hand the NGOs have

the advantage of autonomy and flexibility in their own

structure and their partnership with a government institu

tion or officer who is tied by the procedures may be like

a pair of unequal bullocks resulting in strain and

dissatisfaction to both.

Even in the seemingly faceless and impersonal govern

ment system, the success of cooperation may depend

heavily on personalities. A single person with vision and

openness for new things can make a world of difference.

Whether NGOs find a cooperative government officer or

an obstructive one in their path depends on their luck or

on political manoeuvering. How to match compatible per

sons- from two sides so that smooth working is possible

is a major issue.

Government money should be available to NGOs in

health if they too are working for HFA. And yet if NGOs

take money from the government, they are either subor

dinated by political weapons or they are trapped and im

mobilised by the endless restrictions and procedures which

This document defines the scope and future direction of

HBR within WHO/SEARO. HBR is viewed as part of

health systems research and an integral complement to

all primary health care components.

Feminist review, “Sexuality: a reader”.—London:

Virago, 1987.

The book includes discussion of issues relating to sexual

politics, the social construction of feminity and masculi

nity, psychoanalysis, lesbianism, pornography and

representation, sexual violence and adolescence, with each

article set in its time and context by a series of prefaces

especially written for this volume.

Fukuoka Masanobu, “One straw revolution: an introduc

tion to natural farming”.—Rasulia: Friends rural centre.

1986, pp.181.

The author describes the events that led to th'e develop

ment of his natural farming methods and the impact that

it has had on his land, himself, and the thousands of

people he has taught. He feels that natural farming pro

ceeds from the spiritual health of the individual. He con

siders the'healing of the land and the purification of the

human spirit to be the same process and proposes a way

of life and a way of farming in which this process can

take place. More than merely indicating methods, this

book aims at changing attitudes: about nature, farming,

food, human—physical and spiritual health.

necessarily accompany government grants. In both ways,

the NGO looses its qualities or autonomy and speed.

How can government money be made available to

NGOs and yet not have these side effects is an issue for

discussion.

CHV Experiment: A Case of NGO-Govemment

Interaction

When conceived, the CHV was to be a volunteer bring

ing with him/her the qualities of NGO, i.e. autonomy,

motivation, community participation, etc. And yet

during implementation he was converted into the lowest

category of government worker with little financial

remuneration. He was subordinated and internalised by

the government health structure.

A fate similar to that of CHV must be avoided by giv

ing attention to the various aspects of interaction discuss

ed above. And yet, this is a new area of organisational

research and innovation. Only through a process of trial

and error, experimenting and learning that a feasible

model will emerge. Respect for each other and openness

is an essential prerequisite on either side.

Abbreviations

NGO : Non-government organisation

HFA : Health for All

FP

: Family Planning

CHV : Community Health Volunteer

Edited by Sujata Gothoskar with the co-operation of Manish Manked and secretarial assistance from Anuradha Naik and Eleuterio Fernandes.

Produced by the Foundation for Research in Community Health, 84-A, R.G. Thadani Marg, Worli, Bombay 400 018. Telephone: 493 86 01. Printed

by Modern Ans and Industries, A-Z Industrial Estate, Lower Pare!, Bombay.

S OXFORD i

'J.ErX.T.ff.L l-ISff.l.Thl-J.N

/WDuSr^

Ref. No.

6 3 NN

Q

£r-j Tf) L. ■ !->^L th

Z7 -

P-ppl'/Cn

-~-V^

IJcrthf''

- Mcdfe^ O

D-r _

tsL-OfZ) <2s~>czLo

TJc

CO rc>)'rCcL

/3c^)K c

i.

h)&-p<.

2.

3.

r ooP Kajp

— C-O-r~>

iye.

/^C<.K>-> Cj

%>c\ Y )'^'T7c(j^

'IDE.PP.E&Stpr'S

i I ln^e-^3

&L<s7') r-L^olxJZ- c^L

4. /Az-zg^A^gU^k^^

hfajcAo

. erZe.

Ox^>

/■^c^e^i/i

c^n

sfeteJ-^cL ?

c^

cLCo ^.<s^<> <2

ctj’

hLe-aJ-Leck

g<s»z . e^ ^cet.cf

by

/~^CcH..

7br^~>

(. to yea^,

ElErt TflL.

HE-PL TH

PTZc>J3L£rlE>

HUMfW

T^Ac^oJ^

c^-)

. /-Ox-oZ"■ Pick

l=.XJcef)tan.s

_ fo - X-<a

P.k'...^ ./So. ..^2^<AC^

.P.-rt^c.

Jx^ro. >~>X.L\Ch

_______

—^■y'<s-LJ-p S------

2"crok'JacJ.L.

, J)

_ Scr"C-<'ca./.

-fi2- ~‘''J<~ fi a [s-T^Cj

7 ■/)■£_ ... 73 rcn^-m

—^r"?

___ LS&Jj'Cja^a.J

2.

p.rrcffo Le-tn-a

cZ>[

J-s-i c 'Li^z> /rt<xZ-

z.

FcX

-

A^7^/. /Xe^/ZA

Z<2

.5------ lx/■/

O ■ t^'Lejol^.L

fin

/-/-<£.<=<.O ■ /Y7.• I)

Pj^'cc^

<yz7A&//g->

ZTltfCX-cZA/1,

4>7 <-r<zke-/-y_Cje

- G-cfco-n

Z/- z

Z?.L>_ "?C Z?'l.c<Z7‘S-^'

C?2t<2.CX^^fC^iZak'

^ cS^T-xy^y^rec^ 4?

-

.

-

^Z77t.v//y7Z<" j .

J'a-y^> .. f) >cbLc^->.

Rei->c<hih'h^K<r^

df /reeled

Or

£>/<?.K<S>

ffircro/z

-C-i e~lc^^o

/• /'Wc

/v'fe-c=<< 'Co- K<oo

/T-T-e^c^^e^cj. tftc-

v^C’. /<-<-<£

ezcf L.^jrcn'k..

t>rjpe-^-pcn^c<l

Oceo/'ive.

/<e-ey-7uo

V'c:<~<z-c\-r->^

crr^>&o

'p-r-cxcHcejly

O-o

C^rS^yy<2->' Chirico-'

Coll<? c^cx-e-o

croj?- k)y

— Kke.^-n

raJ'hjzy'

crrCaoftecft ^iJuiaKcra

S

— Z!i_^a_cL^

^■C.jg Lcocj

.

c>/cX

o

jcd?

f^cr-olhLa. .

<2^ -TT_O cro

C^->oL

<S"oLt^ea. f7crr->

CZ>

^^crulcA.

b <?

co- cAaC-li^r l^p^pC'l

ohck be

Cnl'c Ccrr-wicbi-) after

Paints

Slough Works, has

st paint producing

>f the original buildings

nish making of Naylor

lay the site is a giant

Introduction

Slough Works situated in the Thames

Valley services the entire U.K. with

the decorative paints and industrial

finishes produced at Slough, from its

1,000,000 gallon capacity warehouse.

Paints Division also has its H.Q. and

Research and Development centre at

Slough. The operation starting with

patient research and development,

manufacture, marketing and

distribution is centred at Slough and

backed by the other paint producing

factories at Stowmarket and Glasgow,

the Hyde Works where plastic

sheeting and pvc coated fabrics are

made and the wallpaper manufacture

based at Oldham, plus the depots and

sales offices situated to keep pace

with the constant demand for ICI

Paints Division products.

The entire Dulux Gloss finish and

Emulsion ranges are manufactured at

Slough Works. Added to this are the

many industrial finishes for a variety

of markets and topcoats for the car

industry—paint in capacity from |

pint tins to a customer's 34,000

gallon tank filled continuously with

ICI Electrocoat primer. The 1,000

employees including skilled plant

operators, technicians and scientists

keep production over 10,000,000

gallons a year of finished products.

Other products including Dufix

adhesives and industrial varnishes are

made in the Resins section of the

Works which also make the main

constituent for all paints.

Paints Division stay ahead in the

highly competitive paint market to a

great extent because of the work of

the 500 personnel in Research and

Development Department. Winners

of the Queen's Award to Industry

in 1969 for research into polymer

dispersion, the department is

concerned with the invention of new

paints and coatings, the improvement

of manufacturing processes and

background research into the

properties of surface coatings.

Across the Wexham Road from the

Works and Research Department, is

the stylish Division H.Q. building,

housing the administrative force

which ensures the efficiency of the

Paints Division operation. The key

to this success is the new computer

centre which deals with the range of

services from accounts to paint

formulae.

ICI Paints Division is a worldwide

organisation with associate or

wholly owned factories in Australia,

Argentina, Canada, S. Africa, India,

Pakistan, Malaya, Portugal, Germany,

Trinidad and many more countries.

A liaison is kept with these

operations through the Overseas

at Slough.

From Slough the U.K. and overseas

markets are serviced with ICI paints

whether the order is for single tins

or tanker loads. The reputation of the

paint of being a top quality product

'backed by the technical resources

of ICI' is further ensured by the

Technical Service and Colour

Advisory Departments which offer a

service to all customers which helps

them to make the best use of the

wide range of ICI Paints Division's

products.

How Sheet

The popular misconception of paint

making is that the technique is just

a simple 'stick and bucket' process.

In recent years the paint industry

has seen a revolution in paint

manufacture with the introduction

of synthetic resins, complex

formulations and new machinery.

Even so, the basic constituents of

paint have not changed.

Paint is made from three components

—the pigment, which gives colour

and opacity, the resin or binder

which forms the film and the

thinner or solvent which makes it

possible to apply by brush, dip,

spray or other method. The

important steps in production are

first to make the binder—nowadays

almost wholly synthetic resin or

polymer and secondly to incorporate

the pigment into it using one of a

number of different machines.

e

Manufacture

It is from the Stores department at

Slough that the whole process of the

manufacture of paint begins.

Raw materials arrive here and vary

from a 24 ton load of pigment to a

5,000 gallon tanker of solvent. Raw

materials, are very diverse; with over

950 items from all over the world,

including the colouring and dyeing

pigments, some of which are very

costly items—(Monolite Fast Red

costs £5.10.0 a lb.). To the

decorator the Dulux tin is a well

known sight, and 50 million of these

tins are handled by the store each

year. The solvent tank farms

connected to the paints and resins

departments by a network of

overhead pipes are topped up by

a fleet of tankers to the tune of

150,000 gallons a week.

This covers the basic constitutents

of paint except resin which is

primarily manufactured on site in

We Resins Plant.

The manufacture of synthetic resins

has greatly improved the

Top: In the foreground one of the Solvent Farms,

with its network of overhead pipes feeding to the

Paint department. In the middle, is the oil farm which

services the Resins Plant.

Above: A row of 600 mixers, which are used in the

second stage of preparing a batch of paint. The vehicle,

thinner and drier is added to the concentrated paint

base ready for the final colour matching.

Left: The Alkyd Resins plant with its row of 'kettles',

which produce a wide range of resins used in products

manufactured by Paints Division.

Below: Speed and accuracy are essential in filling

'Dulux' into millions of cans of different sizes. Paints

Division engineers have designed ingenious machines

to do the job.

properties of durability, flow and

gloss retention in paint. The last

ten years has seen the introduction

of several new types, acrylics for

cars and industrial paints, P.V.A.

latex for emulsion paints and the

new Electrocoats for electro

deposition on metal surfaces. The

more traditional resins, alkyds for

air drying and stoving finishes and

urea and melamine resins are also

made on the plant.

The different types of resins are

made in separate buildings situated

at the far end of the site.

These products are made in reactors

commonly called kettles. Reaction

temperatures of up to 250 degrees

centigrade or higher are necessary

and the process lasts 12 hours or

more After the chemical process,

which calls for a high degree of skill

rom the plant operators, is

completed, the resin solutions are

tmnned, filter-pressed and pumped

to storage tanks' with a total capacity

of 350,000 gallons. Most of the resin

is supplied by pipeline to the paint

department for pigmentation, but

some is blended to produce clear

industrial insulating varnishes, beer

can lacquers and adhesives.

The Paint department is the hub of

the Works where the different

ingredients, the pigments from the

dry colour stores and the resins

meet to be dispersed into a base.

The pigments are dispersed in the

resins by a variety of machines; Ball

mills, large steel drums half full of

steel or porcelain balls, which

cascade as the drum revolves are

used to disperse the highly

concentrated pigment base for car

and industrial finishes. Fifty Ball mills

with capacity of 50 to 1,000 gallons

are housed in the Paint department.

Attritors and sand-mills use different

techniques to disperse the same

materials, the latter being used where

high quality Titanium pigments are

used as in Dulux White gloss paint.

High speed mixers have been

developed in the industry whereby

all operations are carried out on one

Manufacture

machine. The contents are both

mixed and ground by a blade shaped

like a circular saw two feet in

diameter, which transmits very high

dispersion power to the batch.

Emulsion paint is made by a similar

process except that the combination

of oil and resin is replaced by a

water based emulsion. The final

stage, is carried out in the mixing

section, where the base of the batch

of paint is transferred from the ball

mill, attritor etc. to a separate

finishing mixer, where carefully

weighed ingredients such as solvents,

dryers, anti-skinning agents, etc,

are added. It is at this stage that the

true colour of the paint is reached.

Tinters are added until the skilled

colour matcher has corresponded

the batch with the correct colour

standard. The various properties of

paint batch are then tested and

passed by the Control Laboratory.

The very large number of products

being manufactured at one time

necessitates that an accurate control

record is kept, not only of items

being manufactured, but also of

the stage which each has reached.

Decorative paint is strained into

portable containers and transferred

to another building to be filled into

tins. The paint is fed into the

machines by means of automatic

air controlled valves. Tins ranging in

size from | pint to 1 gallon are fed

into the machine, filled, capped and

passed along a conveyor belt for

packing. Half pint and 1 pint tins

are packed into cartons for easy

handling. These in turn are stacked

on pallets of uniform size into the

warehouse.

The warehouse, a four-storey

building, capable of holding over a

million gallons of paint, acts as a

store for finished products from

Slough and some products from

other factories in the Division, and

as a distribution centre to Paints

Division Depots and customers on

demand.

The paint is brought by fork lift

trucks and stored in bins or pallet

racks. Loading goes on day and

night onto long distance lorries and

local delivery vans. A proportion is

also for export. The entire works is in

full production day and night,

operating a three-shift system. The

smooth running operating includes

canteen facilities on site, a medical

centre, an efficient fire brigade

which is run by men on the works.

Training is given to all the plant

operators on joining the Company.

Much of the paint making history of

the last half-century has been

written here at Slough. The team

work, the technological skills and

the enthusiasm of all Paints

Division's personnel will ensure that

much of the future progress in paint

making will also take place here at

Slough.

Top right: Comparative hiding tests being carried out

in the Development department at Slough between

Dulux and other paints.

Above left: The latest development in the bulk

handling of pigments. The Titanium Dioxide silo holds

pigment used in the manufacture of Dulux Gloss paint

and Supercover Emulsion. The pigment is pumped

by compressed air from the 90 ton silo direct to the

high-speed mixers.

Centre right: Many hundreds of investigations are made

each year with the Electron Microscope, which can

magnify up to 50,000 times. It is used for examining

the shape and structure of pigments and extenders,

paint surface defects and for studying the internal

structure of paint films.

Above: Paint supplies are sent daily from Slough

Works Warehouse to Paints Division Depots

strategically placed throughout the country.

19 6 9

THE QUEEN'S AWARD TO INDUSTRY

ESSO

AT FAWLEY

Esso Petroleum Company, Limited is the U.K. affiliate of the

group parent company - the Standard Oil Company (New

Jersey). Founded in London in 1888, it is among the oldest and

largest of the oil companies in the United Kingdom. Its net assets

are over £300 million; with its affiliates it supplies more than a

quarter of the nation's oil products, and its annual turnover is over

£600 million. It collects more than £300 million each year in

Customs and Excise duties and the value of its total annual export

amounts to £20 million.

Esso Chemical Limited, founded in 1965, is the United Kingdom _

affiliate of the world-wide network of Esso Chemical Company i^J

which operates 64 manufacturing plants in 29 countries.

This leaflet provides a brief description of some of the refining and

chemical manufacturing processes of these Companies at their

Fawley complex; on the back page are listed some of the salient

facts and figures about Fawley.

Esso Petroleum Companymajor refining processes

Esso Chemical Limitedmajor manufacturing plants

1 Primary distillation

This is a process of fractional distillation. Crude oil is first heated

in a furnace and the vapours produced are then condensed in a

fractionating column to produce fractions of different boiling ranges.

These raw fractions are subsequently further refined or purified.

8

Steam cracking and ethylene recovery

Steam cracking is a high-temperature thermal cracking process to

produce olefins and diolefins as feedstocks for other chemical,

plastic and rubber manufacturing processes. The feedstock of

either naphtha or gas oil is vaporized, mixed with steam, and heated

to high temperatures. Under these conditions most of the high

molecular weight hydrocarbons in the feed are cracked to produce

a wide range of low molecular weight hydrocarbons including

ethylene, propylene, butenes and butadiene. These are separated

as saleable products or for further processing in other plants.

2 Catalytic cracking

Cracking breaks large oil molecules into smaller ones. One

application at Fawley is in cracking a heavy gas oil to form high

grade petrol and gas. The process used is known as 'fluid catalytic

cracking’ - 'fluid' because the catalyst (this helps the cracking

reaction without being changed itself) can be made to flow like a

liquid when it is blown with air or hydrocarbon vapour.

3^^/verforming

This process changes the configuration of atoms within molecules

rather than the size of the molecule. The Powerformer converts low

quality naphtha from primary distillation into a high-quality

petrol component.

4

Polymerization

Polymerization is the reverse of cracking; it builds up small

molecules into larger ones. Light gases, produced by the catalytic

cracker and chemical units, are combined to produce heavier

materials, such as heptenes and high-quality petrol.

9

Isobutylene extraction and recovery

This extraction process, using sulphuric acid as a solvent, separates

and recovers isobutylene from mixed butenes produced during the

catalytic and steam cracking processes. Isobutylene is one of the

feedstocks for the manufacture of butyl rubber.

10

Butadiene extraction

These units recover and purify butadiene from the raw

butadiene-containing streams produced by the steam cracking units.

Butadiene is fed to neighbouring International Synthetic Rubber

Company for the manufacture of the synthetic rubber - styrene

butadiene. End uses include car tyres.

11

Butyl rubber unit

This unit consists of a co-polymerization section where raw rubber

is made from purified feed streams of isobutylene and isoprene, and a

finishing section, where the raw rubber is dried, baled and

packaged. The unit has been recently expanded with facilities to

manufacture chlorobutyl rubber.

5

Treating processes

Almost all the fractions obtained by primary distillation need to be

further 'treated' to meet the very stringent specifications demanded.

One example is the removal of sulphur from such products as diesel

oil and white spirit. This is done by a Hydrofining process, where

sulphur compounds are converted to hydrogen sulphide. The H2S

is then fed to the Sulphur Recovery plant capable of producing up

to 60 tons/day of pure rock sulphur. Further examples of treating

are the Edeieanu process for the removal of aromatics from

kerosene and the copper sweetening process for converting corrosive

I^B ialodorous compoundsinto non-corrosive and inoffensive ones.

12

Aromatics extraction unit

Another extraction process, using a feedstock from the

Powerformer, rich in aromatics. This feedstock is subjected

to sulfolane extraction and subsequent fractionation to recover

toluene and benzene. These important intermediate chemicals are

used in making plastics, synthetic fibre, detergents, paints, dyes, etc.

6

Lubricating oil manufacture

Feedstocks for lubricating oil manufacture are prepared by vacuum

distillation of the residue from primary distillation of certain crude

oils. There are three further processes:

i

Phenol treating to remove undesirable aromatic compounds.

ii

Hydrofining to improve the colour and stability of the oil.

iii

Dewaxing to improve the 'pour' characteristics.

13

Methyl ethyl ketone unit

Butenes from steam cracking are extracted with sulphuric acid to

recover normal-butenes as secondary butyl alcohol. The crude

alcohol is purified by fractionation and dehydrogenated, by a

catalytic process, to methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) which is then

purified by further fractionation, mek is used as a solvent for

industrial and pharmaceutical applications.

7

Bitumens

On this unit the residue from vacuum distillation of Venezuelan

crude oil is blended with a diluent to produce a range of penetration

grade bitumens, some of which are subsequently air blown to produce

oxidized bitumens.

14

Paramins plant

A series of vessels in which various purchased and indigenous

chemicals are reacted or blended, in batch processes, to give a

wide range of additives, a number of which are used to improve

specific characteristics of lubricating, fuel and crude oils.

Some facts and figures about Fawley

The marine terminal

General

Small refinery commissioned in

deadweight tons (draught limitation 49 feet) turn a

24 hours. With over 18 million gallons of crude oil or ^ned

oroducts crossing the terminal each day, it handles more tonnag

foone°month than is handled by the Port of Southampton m a year.

Automation

Direct Digital Control (or D.D.C.) is the operational term which

describes the system of computer control installed in two areas ot

the refinery. The first of these was commissioned in 1968 and won

for Esso Petroleum Company the distinction of being the first oil

company to receive the Queen’s Award to Industry. In 1970 Esso

Chemical Limited were similarly honoured fortheir contribution to

the export market - the Company having increased its exports

from 16 per cent, to 33 per cent, on total sales over a three-year

period.

1921

First major expansion

1949-1951

Capacity of the refinery per year

19 million tons (13 mill/galI/

day)

Employees

about 2,200

Investment at Fawley

£140 million

Investment per employee

£63,000

Land area (includes undeveloped

foreshore)

3,300 acres (about 1,300 acres

developed)

Local rates per year

over £11 million

Local harbour dues, pilotage and

tugs per year

about £| million

Local wages, salaries, purchases

per year

£9 million

Utilities Required

Environmental control

Steam per hour

1| million lb.

Industrial development must always be at a certain cost in terms