INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

Item

- Title

- INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

- extracted text

-

RF_IH_20_SUDHA

adivasi

been given the lands and resources of the

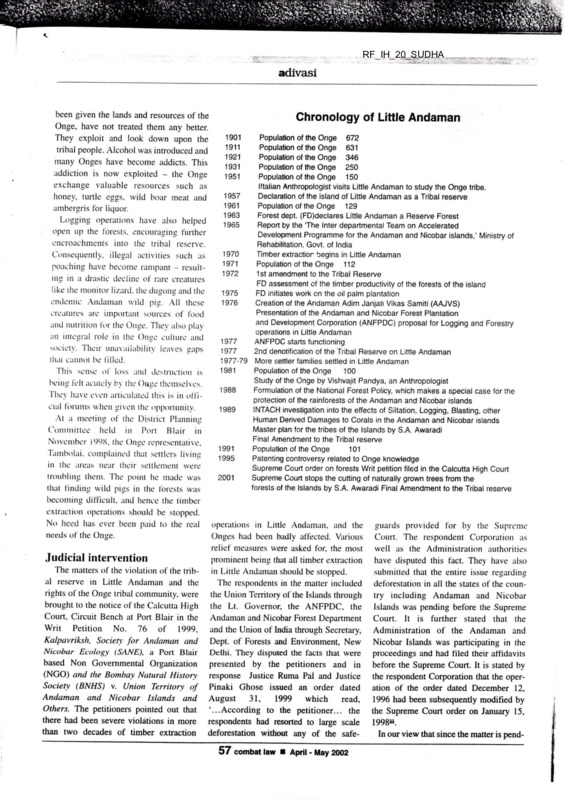

Chronology of Little Andaman

Onge, have not treated them any better.

1901

Population of the Onge 672

They exploit and look down upon the

1911

Population of the Onge 631

tribal people. Alcohol was introduced and

1921

Population of the Onge 346

many Onges have become addicts. This

1931

Population of the Onge 250

addiction is now exploited - the Onge

1951

Population of the Onge 150

exchange valuable resources such as

I Italian Anthropologist visits Little Andaman to study the Onge tribe.

1957

Declaration of the island of Little Andaman as a Tribal reserve

honey, turtle eggs, wild boar meat and

1961

Population of the Onge 129

ambergris for liquor.

1963

Forest dept. (FD)declares Little Andaman a Reserve Forest

Logging operations have also helped

1965

Report by the ‘The Inter departmental Team on Accelerated

open up the forests, encouraging further

Development Programme for the Andaman and Nicobar islands,’ Ministry of

encroachments into the tribal reserve.

Rehabilitation. Govt, of India

1970

Timber extraction begins in Little Andaman

Consequently, illegal activities such as

1971

Population of the Onge 112

poaching have become rampant - result

1972

1st amendment to the Tribal Reserve

ing in a drastic decline of rare creatures

FD assessment of the timber productivity of the forests of the island

like the monitor lizard, the dugong and the

1975

FD initiates work on the oil palm plantation

endemic Andaman wild pig. All these

1976

Creation of the Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS)

Presentation of the Andaman and Nicobar Forest Plantation

creatures are important sources of food

and Development Corporation (ANFPDC) proposal for Logging and Forestry

and nutrition for the Onge. They also play

operations in Little Andaman

an integral role in the Onge culture and

1977

ANFPDC starts functioning

society. Their unavailability leaves gaps

1977

2nd denotification of the Tribal Reserve on Little Andaman

that cannot be filled.

1977-79 More settler families settled in Little Andaman

1981

Population of the Onge

100

This sense of loss and destruction is

Study

of

the

Onge

by

Vishvajit

Pandya, an Anthropologist

being felt acutely by the Onge themselves.

1988

Formulation of the National Forest Policy, which makes a special case for the

They have even articulated this is in offi

protection of the rainforests of the Andaman and Nicobar islands

cial forums when given the opportunity.

1989

INTACH investigation into the effects of Siltation, Logging, Blasting, other

At a meeting of the District Planning

Human Derived Damages to Corals in the Andaman and Nicobar islands

Master plan for the tribes of the Islands by S.A. Awaradi

Committee held in Port Blair in

Final Amendment to the Tribal reserve

November 1998, the Onge representative,

1991

Population of the Onge

101

Tambolai. complained that settlers living

1995

Patenting controversy related to Onge knowledge

in the areas near their settlement were

Supreme Court order on forests Writ petition filed in the Calcutta High Court

troubling them. The point he made was

2001

Supreme Court stops the cutting of naturally grown trees from the

forests of the Islands by S.A. Awaradi Final Amendment to the Tribal reserve

that finding wild pigs in the forests was

becoming difficult, and hence the timber

extraction operations should be stopped.

No heed has ever been paid to the real operations in Little Andaman, and the guards provided for by the Supreme

needs of the Onge.

Onges had been badly affected. Various Court. The respondent Corporation as

relief measures were asked for, the most well as the Administration authorities

Judicial intervention

prominent being that all timber extraction have disputed this fact. They have also

The matters of the violation of the trib in Little Andaman should be stopped.

submitted that the entire issue regarding

al reserve in Little Andaman and the

The respondents in the matter included deforestation in all the states of the coun

rights of the Onge tribal community, were the Union Territory of the Islands through try including Andaman and Nicobar

brought to the notice of the Calcutta High the Lt. Governor, the ANFPDC, the Islands was pending before the Supreme

Court, Circuit Bench at Port Blair in the Andaman and Nicobar Forest Department Court. It is further stated that the

Writ Petition No. 76 of 1999, and the Union of India through Secretary, Administration of the Andaman and

Kalpavriksh, Society for Andaman and Dept, of Forests and Environment, New Nicobar Islands was participating in the

Nicobar Ecology (SANE), a Port Blair Delhi. They disputed the facts that were proceedings and had filed their affidavits

based Non Governmental Organization presented by the petitioners and in before the Supreme Court. It is stated by

(NGO) and the Bombay Natural History response Justice Ruma Pal and Justice the respondent Corporation that the oper

Society (BNHS) v. Union Territory of Pinaki Ghose issued an order dated ation of the order dated December 12,

Andaman and Nicobar Islands and August

31,

1999

which

read,

1996 had been subsequently modified by

Others. The petitioners pointed out that

‘...According to the petitioner... the the Supreme Court order oh January 15,

there had been severe violations in more respondents had resorted to large scale

1998“.

than two decades of timber extraction deforestation without any of the safeIn our view that since the matter is pend57 combat law ■ April > May 2002

adivasi

The Colonization of

Little Andaman Island

Various schemes were proposed under the

broad categories of strategy, agriculture,

animal husbandry, forest, industry,

fishery, water, transport, health,

colonization and manpower.

The island of Little Andaman was spe

Its impact on the Onge tribal community

cially earmarked for a Rehabilitation and

Resettlement (R and R) programme, con

recent order of the Supreme forests and the oceans here (see box titled sidering many had favourable factors like

Court has marked an

‘A Precious Heritage').

the fact that it was an island, its few inhab

important watershed in the

A powerful two-pronged attack - on the itants (only the Onge), and good natural

history of the Andaman natural resource base that sustains the and forest resources, particularly timber.

w^and Nicobar islands. For Onge and on the culture of the The committee suggested drastic steps for

the first time ever, since the British set up community - has over the past three the development of the Island. The sug

their colony here in 1858. timber_extrac- decades slowly but surely pushed the gestions made for Little Andaman

tion operations have been stopped and the Onges to a point of no return. Though the included felling half of the island's

priceless rainforests have been given a history of the settlements, and the timber forests; preparing a settlement of 12.000

crucial breather.

extraction operation in the Andaman settler families on the cleared land; cre

The Andaman and Nicobar islands are Islands in general, is more than a century ation of plantations of coconut, arcca. and

well known for being home to some of the old. Little Andaman remained completely palm oil; and the use of the felled limber

finest rainforests, mangroves and coral

untouched till very recently.

tor wood-based industries like saw mills

reefs found anywhere in the world. The

The story of the Onge people's alien and ply wood factories.

forests here are home to a large number of ation began in the late 1960s. when the

Had the plan been implemented fully, it

endangered species of flora and

Government of India planned a would have destroyed Little Andaman and

fauna, and have rightfully been

massive development and colo caused the extinction of the Onge tribe.

recognized as one of the

nization programme for the Fortunately, logistical problems, lack of

global biodiversity hotspots.

union territory of the Andaman infrastructure and a revision of policies

Importantly they are also home

and Nicobar islands, in complete over time, ensured that the destruction

to six aboriginal tribal communi

disregard of the fragile environ was not complete. However, in the very

ties that have lived here for thou

ment of the Islands and the rights conception and planning of the develop

sands of years. These include the

of the tribal communities. Till ment programme, the Onges were sideNicobarese and the* Shompen

this time the complete island of lined and the violations had begun.

Pankaj

who are of Mongloid origin and

Little Andaman had belonged

Sekhsaria

The government team that suggested the

inhabit the Nicobar group of

only to the Onge. As a part of the development programme ignored the

islands. The other four are the Sentinelese,

massive development programme, thou- Andaman and Nicobar Protection of

rht^ Jarawa. the^Onge and th^6 Great sands of mainland Indians, refugee fami Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (ANPATR).

.ndamanese who live in the Andaman lies^ from erstwhile East Pakistan (now which had accorded the status of a tribal

Islands and are of Negrito origin.

Bangladesh) and Tamils from Sri Lanka reserve' to the entire island of Little

were settled here.

Andaman in 1957. Further, about 20.000

The story of the Onge

An T nter Departmental Team on hectares (ha) (roughly 30%) of the island

The Onges form a small community of Accelerated Development Programme for were denotified from its tribal reserve sta

around a hundred individuals, and the 732 Andaman and Nicobar.' set up by the tus in two stages - in 1972 and 1977 sq km of the thickly forested island of Ministry of Rehabilitation. Government leaving 52.000 ha as an inviolable tribal

Little Andaman is their only home. The of India, submitted its report in 1965. The reserve.

community, which has flourished in the plans, and more importantly, the thinking

island for centuries, is today poised on the and the attitudes of the time were clearly Indiscriminate logging

brink of extinction. Though not much is evident in the report - popularly referred

In 1976, the Andaman and Nicobar

known about them, there is clear proof to as ‘the Green Book.' It prescribed the Islands

Forest

Plantation

and

that they have an astonishing depth and route for the development of the Islands in Development Corporation (ANFPDC)

diversity of knowledge related to the general, and Little Andaman in particular. was formed, and it presented its ‘Project

The Onges are a community of around a hundred individuals, and the thickly forested island of Little

Andaman is their only home. The community... is today, poised on the brink of extinction.

54 combat law ■ April - May 2002

adivasi

I!

fl

I

L1J

gc

o

O

o

... MiManrMWriMM

Mangrove forests are an important breeding ground for the diverse marine life of the area.

Report for Logging and Marketing of tim Port Blair in the case FMAT No. 3353 of maintained that a Project Report (men

ber from the forests of Little Andaman.’ It

1995. Range Officer, Andaman and tioned above) had been prepared by them

was estimated that a total of 60,000 ha of Nicobar islands Forest Plantation and in 1976. and since it had been approved by

the island was available for logging, and Development Corporation and others v. the Central Government, there was no

that 60.000 cubic metres of timber could Sushi/ Dhali, a resident of Ramkrishnapur need to draft a Working Plan. A look at

be extracted annually from 800 ha. Of the of Hut Bay in the island of Little the Project Report makes it clear, howev

denotified area, 19,600 ha were handed Andaman. The matter was related to a er. that it is extremely sketchy, and mere

over to the ANFPDC, and timber extrac case of encroachment in the Reserve ly an excuse for the continued logging

tion began in 1977.

Forest area of Little Andaman by Sushil operations. In no way does it meet the

idea of logging from 60.000 ha of Dhali. In his order dated May 30, 1996. needs of a Working Plan. A comparison of

the forests of Little Andaman was another Justice B.P. Banerjee observed regarding this Project Report to any of the Working

clear violation of the Onge tribal reserve. the lease agreement between the FD and Plans for other parts of the Andaman

When 52.000 ha of the island's total area the ANFPDC. ‘...We are at a loss to Islands, makes this amply clear.

of 73,000 ha was already a tribal reserve, understand how under the law of contract Significantly, the Deputy Conservator of

how could 60.000 ha be made available or under any other law for the time being Forests - Working Plan (DCF-WP) of the

for logging? Statistics also show that the in force the government could grant lease Andaman

and

Nicobar

Forest

area logged and timber actually extracted in 1987 with retrospective effect from Department, was also working on the

was in excess to what had been permitted.

1977. The grant of lease with retrospec preparation of the Working Plan at the

Significantly, though the ANFPDC tive effect by the state authorities in same time that the Department was deny

started extracting timber from the forests favour of a Corporation is not permissible ing the need for one. In light of this fact it

of Little Andaman in 1977, a lease agree under the law...’ In spite of this observa seemed amply clear that the continued

ment was signed between the Corporation tion of the Court, the lease has continued timber extraction in Little Andaman, in

and the Forest Department only in 1987, to be operational till today

the absence of a Working Plan, was violafor a period of 30 years from 1977 to

The other important issue related to log- live of the Interim Order of the Supreme

2007. This matter of the lease was the sub ging in Little Andaman was the absence Court, dated December 12, 1996 in the

ject of a very pertinent observation of the of a Working Plan.*’ When this was point Writ Petition (Civil) No. 202 of 1995, TN.

Calcutta High Court, Circuit Bench at ed out in 1999. the FD and the ANFPDC Godavarman Thirumulkpad v. Union of

55 combat law ■ April - May 2002

Hfl

adivasi

India and Others, which said that, ‘the

felling of trees is to remain suspended in

accordance with the Working Plans of the

State Governments as approved by the

Central Government ... ’

Another very serious violation was

committed, by the ANFPDC. There was

clear evidence that it had logged timber

from within the boundary of the tribal

reserve, making a mockery of the law and

the rights of the Onges. Maps available

with the ANFPDC and the Forest

Department have logging coupes, dated

1990 onwards, marked clearly within the

tribal reserve.

Resttlement of outsiders

J •

Even as these violations occurred, thou

sands of outsiders were settled in Little

Andaman since the 1970s. The settler

population grew rapidly: from a few hun

dreds in the 1960s to 7,000 in 1984, and

over 12,000 in 1991. displacing Onges

from some of their most preferred

habitats. Hut Bay, the main town in the

Island, is an example. The ratio of the

number of outsiders, with respect to the

number of Onge in Little Andaman, has

changed drastically against the interests of

the Onge.

The Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas

Samiti (AAJVS). the official tribal wel

fare body of the administration, intro

duced welfare measures that were com

pletely unsuitable for the Onges.

Foodstuff such as rice, dal, oil and bis

cuits were introduced to a community <

whose traditional food included the meat X

of the wild boar and turtle, fish, tubers and

honey. The agency even offered each 3

adult 250 gm of tobacco as a ‘welfare' ?

measure. In a blatant attempt to move the £

forestry operations deeper into the forests |

of Little Andaman, authorities sought to 2

settle the nomadic Onges at Dugong

Creek in the North East of the island, and Jellyfish in the seas off Port Blair.

in South Bay at the southern tip. Wooden

houses on stilts, with asbestos roofing economy in the community, which did not

were constructed for them at these places. have even a barter system. Ill-conceived

These structures were not suited for the schemes, such as the raising of a coconut

hot and humid tropical environment of the plantation (in which the Onge were made

Islands. The Onge preferred to live in workers), cattle rearing (the community

their traditional huts in the forest nearby.

does not consume milk) and pig breeding,

Attempts were made to introduce a cash were introduced. All of them failed.

56 combat law ■ April - May 2002

A visit to the Onge settlement of

Dugong Creek has become mandatory on

the VIP itinerary. Not only are the Onge

expected to perform for the pleasure and

entertainment of the VIP, they are also put

to work to tidy up the settlement.

The settler communities, which have

TROUBLED

ISLANDS !

Writings on indigenous peoples and the

environment of

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India

H

Pankaj Sekhsaria

Kalpavriksh

Apt 5, Sri Dutta Krupa,

mW

908 Deccan Gymkhana,

Pune - 411004, India

Teh/Pax: 020 5654239

Email: kvriksh@vsnl.com

i

April 2002

A Contributory amount Rs. 40/-, US $ 5

Proceeds will go into the research , legal and advocacy activities of Kalpavriksh in the Islands

C»CO

/VOKTH

CALCUTTA

iaWA

a

'HH.IAUA

NAKCOM6AM It

B.AV

OF

e>£H4>AL

lure.* view

!''■*) aaaYA ^UAtitLA-

it

MlbbLC

AHbAMAfil

AAAAAAA’

'tCA^J+AT

ft

M'AaAMTAlAl..

^AKATAN^ !i

ft’

AtAr

icuTH

R

ah6aa

"OATH

4CNT/NZI

It

e>AM£ti h

w-

AJUA

b^TAlU^

$

U HAVELOCK It

It

tLAIA

rx

kJ

„^AUTLAHl> It

t

• e

i> U Al C A A/

Lime

y'

\

PA4^AO£

OUOOIUO CAM.EK

AaIDPlAAAH t£A

>

*VB*r ** A > HUT BAY

T£ K

>£6*E.E.

CHANNEL

AAA MICOBAA It

TILLANCfiOMS It

'6MAUAA M

TJAMASA /*

4

ItAMOKTA M

^TAiUKAT 1^

5a/AM4OWAY It

katghXll ft

iOAA & Hl A O

AMbAAM AW>

NICObAA

HLMt^

tUblA

AO KM

vii

^HAAlAlg.^

LITTLE Mie06*A

6K£AT NltoaAA

LIST OF ARTICLES

1)

Jarawa excursions.

2)

Embracing disease

3)

Delivering the Jarawas.

4)

A people in peril

5)

Deforestation in Andaman and Nicobar: Its impact on Onge.

6)

Logging off, for now.

7)

A history of alienation.

8)

The new millenium tamasha

9)

Turtle tales.

About this Compilation

Over the years there has been a reasonable amount of anthropological and

academic work on the hunter-gatherer communities of the Andaman & Nicobar

islands. At the same time, however, the threat to the survival of these small

communities has intensified as development policies that were completely

insensitive to their have been conceived, prepar ed and implemented here

Little, if any, research or publication in the mainstream Indian media has

been seen on this aspect of the islands in the last few decades.

Troubled Islands! is a compilation of articles since 1998 on precisely these

issues. It is perhaps the most comprehensive contemporary account of the situation

in the islands from a non anthropological point of view. The articles were first

published in leading Indian publications that include Frontline, The Hindu and

Economic and Political Weekly. They look at some of the key issues faced by the

indigenous peoples of the islands today and follow in detail some of the major

developments that have taken place over in the last few years.

2

I INDIGENOUS PEOPLE

Ml <;>

a.

•' //*

Jarawa excursions

Members of the dwindling Jarowa tribal community in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are stepping

out of their forest habitats for the first time. What is in store for them?

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

T N October 1997, settlers in the Middle

1 Andaman island, one of many that

make up the Andaman and Nicobar

Islands in the Bay of Bengal, were wit

nesses to an unfamiliar sight: a group of

Jarawas, one of six aboriginal tribal com

munities that have lived on the archipel

ago for centuries, had ventured out of the

forest and into modern settlements. This

was the first recorded instance ofJarawas

voluntarily seeking to establish contact

with the settlers from mainland India. It

was particularly puzzling given the fact

that Jarawas have for long been hostile

towards the settlers, to whom they have

lost large swathes of their forests, and the

tribal people have fiercely defended what

is left of their traditional lands.

Over the next few months, there were

several more reports of Jarawas coming

out of their forests. Some of them, it was

reported, were seen to point to their bel

lies: these were interpreted as expressions

of hunger. In the belief that they had run

66

■

'I

*5®|

FRONTLINE, JULY 17, 1998

3

| out of their traditional food resources in

| the forests and were facing starvation, the

« local administration, led by Lieutenant-^23^ Governor I.P. Gupta, arranged for food

relief. Packets containing dry fish, puffed

rice and bananas were air-dropped from

helicopters into Jarawa territory.

fl

Q»y^.Cape Price

North

Andaman1

| Diglipur

Port

Andaman

INDIA

I

Bay of

Bengal

1 Middle

J Andaman

3

Jarawa

reserve

South

«J

■

'

■

Looking towards Port

Blair. Largo swathes

of forest in the

< b

»

Qi

Rutland

PZ <

0

o

■

Duncan Passage

A nd a man a n d N i.c o b ar

Islands have been

creared o.^r a period

I to house settlers from

J the mainland and to

■ feed the timber

«

E

I

1

9 industry. (Below)

I Some members of the

|

II

Jarawa community

who arrived by boat at

?

_ the Uttara jetty near

7, Kadamtala in Middle

Andaman on April 9

c I

5® Port Blair

Andaman Sea

< 07 7

“IS

Andaman

5

E

Ten Degree Channel

"

J

rr

<

77

w CA

g5

CO

o

CD

Great Nicobar

FRONTLINE, JULY 17, 1998

Port Blair!

The natural resources that Jarawas

have had access to have vastly diminished

over time for a number ofreasons, includ

ing widespread deforestation to accom

modate settlers and to feed the flourishing

timber industry. Even so, the theory that

starvation is driving Jarawas out of the

forests appears to be flawed. Jarawas have

sustained themselves on forest produce

for centuries, and there is no reason to

believe that they have suddenly been

pushed into starvation. In any case, eye

witnesses say that the Jarawas who were

sighted recently appear to be healthy,

robust and agile.

Moreover, in February and March,

no person from the tribal community

approached the settlements for extended

periods, that is, for more than two weeks.

And when they did show up, it was often

in small groups of five to 10 persons.

Anthropologists, however, have

another explanation for the Jarawas’ curi

ous “coming out”. It relates to the expe

rience of Enmey, a teenaged Jarawa boy,

who was found with a fractured foot near

Kadamtala town in Middle Andaman

last year. The local residents, most of

them settlers, arranged for his treatment

at the G.B. Pant Hospital in Port Blair,

where he was looked after well. When

Enmey recovered, he was sent back to

Middle Andaman, where he promptly

disappeared into his forest home. Since

October, it is Enmey who has largely

been responsible for bringing his people

out.

Anthropologists explain that Enmey

developed a cultural affinity to the out

side world: in their view, Enmey perhaps

wanted others in his community to expe

rience the settlers’ hospitality that he had

had a taste of. It is this, and not starva

tion, that had drawn the Jarawas out of

the forests, they reason.

MpHE forests of the picturesque

JL Andaman and Nicobar Islands are

home to six tribal communities. The

Andaman group of islands are inhabited

by four tribes ofNegrito origin: the Great

Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawas and

the Sentinelese. The Nicobar group is

home to two tribes of Mongoloid origin:

the Nicobarese and the Shompens.

Precisely when and how members of

these tribes came to inhabit the islands is

not known.

What is known about them is that

their limited contacts with other peoples

have rendered them aggressive and hos

tile towards outsiders: they fiercely

defend themselves and their space. Many

67

4

S□

cn

3

I

w

iu

tt

b

members of the tribes were forcibly taken

as slaves by Arab seafarers who traded

along these routes.

The establishment of penal settle

ments - the infamous Cellular Jail - in

the islands by the British in 1858,

Japanese occupation during the Second

World War and independent India’s

colonisation and resettlement plan for the

islands had the effect of further isolating

the tribal communities.

The population of the islands, which

was about 24,500 in 1901, is nearly four

lakh today; however, the populations of

the tribal communities (except the

Nicobarese) have dwindled (see box).

Only the Sentinelcsc and the Jarawas have

been able to retain a semblance of their

identity. The Jarawas, however, are under

severe pressure. Today there are only 250

of them and vast expanses of their rain

forest homelands have been cleared to

accommodate settlers and to feed the

huge timber industry, on which the eco

nomic foundation of the Andamans is

laid.

68

(Above left) Watched by curious settlers, the Jarawas wait at the jetty; (above) a

Jarawa woman and her child have a brush with authority; (left) after receiving a

gift of coconuts and bananas, the Jarawas head back home.

In order to protect the Jarawa way

ray of demolished bridges and even attacked life, a Jarawa tribal reserve was established and occasionally killed - the workers,

over a 700-sq-km area: the objective was Work came to a halt in 1976, but was

as much to keep the tribal population resumed soon. Traffic on the road, which

confined to the reserve as to prevent set was completed recently, has grown enor

tlers from encroaching into it. Along the mously.

Today, many more settlers live in the

periphery of the reserve, 44 bush police

camps with about 400 policemen were areas bordering the reserve, thereby

established. Over time, however, several increasing manifold the possibility of

encroachments were made and the func- interaction-and conflict—between them

tion of the police force has been reduced and the Jarawas. Instances of people tresto confining the Jarawas, who once passing into the reserve to hunt wild boar

roamed the length and breadth of the and deer, and to poach forest produce

island unhindered, to the reserve area.

such as honey and timber, are common.

The 340-km-long Andaman Trunk At times, the trespassers destroy the

Road, which slices through the heart of rudimentary settlements of the Jarawas.

the Jarawa reserve, has opened up more In addition, many illegal encroachments

areas for settlement. Right from the have come up in the reserve area with

begining, the Jarawas had protested political patronage.

against the construction of the road on

VER the years, the island administhe ground that it would endanger their

way of life. They set up road blocks, VV tration has tried to establish friend69

The lost races

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

the six aboriginal tribal communities that originally inhabited the

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, at least

two - the Great Andamanese and the

Onge - fell victim to the march of civil

isation and everything that came with

it.

The Great Andamanese, who had

lived in an insular world for centuries,

were the first tribal community with

whom the British established contact.

The Onge, who lived on the Little

Andaman, were the next. Both com

munities suffered the ill-effects of this

influence. Epidemics of diseases such as

pneumonia (which broke out in 1868),

measles (1877), influenza (1896) and

syphilis killed hundreds of Great

Andamanese. The tribal people had no

resistance to these diseases, which they

contracted from outsiders.

The Great Andamanese are today

virtually extinct. In the early part of the

19th century, tlieir population was estimated to be around 5,000; today, there

are only 28 of them.

The Onge have fared only marginally better. Their population has dwin-

ly contact with the tribal communities

(Frontline, August 17-30,1991), includ

ing the Jarawas. In 1974, a contact party

comprising administration officials,

members of the Andaman Adim Janjati

Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), anthropologists

Population trends (in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands)

Year

WOT

1911

1921

1931

1951

1961

1971

1981

1991

1998

Total population

~ 24,499

26,459 ___

27,080 ______

29^476

30,971

63,548

2,15 J 33

1,88,745

2,80,661

4,00,000 (estimated)

625

455

209

90_

23___

"19

19

25

28

Onge

^672

631

346

250

250

129

112

JOO

101

I

Note: Population data in respect of the Jarawas and the Sentinelese are

unavailable because members of these tribal groups have in the past

resisted any attempts to establish contact with them.

I

died from 600 in 1901 to about 100 the Onge people by the settlers, has

today. Since the 1960s the Onge home-- extracted a heavy toll. Settlers use alcoland in Little Andaman was cleared of hoi, to. which many among the Onge

its verdant forests to house thousands of people have become addicted, to exploit

setders from mainland India. A large- them. The Onge give away resources

scale timber extraction operation was such, as honey, ambergris, and turtle

also started. Attempts are on even today eggsfor the ubiquitous bottle, popularto confine the Onge people to two small ly known as 180.

Thus two hardy races, which flour

settlements so that the rest of the island,

ished for centuries in these islands, have

which is still a tribal reserve, can be

been swept aside by the tides of “civiliopened up further.

Alcohol, which

to sation”. Hi

. LLL was

. ... introduced

----

and police officials, established friendly

contact with some members ofthe Jarawa

community along the western coast of

Middle Andaman. The party approached

the Jarawa territory by sea and left behind

gifts - bananas and coconuts - hoping to

Enmey (standing), the Jarawa teenager who is believed to have played a major

role in bringing people of his community out of the forest to meet the settlers.

70

Andamanese

|

win the confidence of the tribal people,

Critics, however, liken this to the

practice ofscattering rice to ensnare birds.

They argue that the official policy vis-avis the tribal people is aimed at making

them dependent on the administration.

3 The pattern of the Jarawas’ recent behav< iour appear to bear this out: increasingly,

| the Jarawas who emerge from their jun

gles do not leave unless they are gifted

3 bananas and coconuts.

5Q.

The Jarawas have never allowed any

one access to their territory by the land

route; nor, until October 1997, had they

ever emerged voluntarily and unarmed

from their forest homes or initiated any

interaction with the outside world. Last

year’s development is therefore very sig

nificant, but the administration has not

always responded with sensitivity to the

Jarawas’ needs. An incident which this

writer witnessed on April 9 illustrates this

point.

i

I

I

A-

fa

1

A t 8 a.m. that day, 63 Jarawas, the

jiXlargest group yet to emerge from the

jungle, arrived at the Uttara jetty near

FRONTLINE, JULY 17, 1998

0

*

7

Kadamtala. Among them were several |

children and women with babies. It is, of 5

course, true that the administration has «

no way of knowing where and when the |

next group ofJarawas will turn up or just 2

how many ofthem will be there; but even

so, there appeared to be little evidence of

planning for such contingencies.

Until such time as coconuts and

bananas could be arranged for the

LI3”'

Jarawas, they were herded into a small

waiting hall at the jetty and made to wait

on that hot, sweltering day without food

or water. The only people at the jetty who

seemed equipped to handle the situation

were a policemen and three boatmen who

knew some ofthe J arawa people. But after

a while, when the Jarawas grew restive,

even the boatmen ran out ofideas. Things

got a bit rough, and there was a fair bit of

shoving and pushing around, which the

fiercely independent Jarawas resented.

The consignment of coconuts and At Jlrkatang, the entry point to the Jarawa tribal reserve. All vehicles that enter

bananas that the local police had organ- the reserve are provided with armed guards from this point onwards. (Below)

ised arrived around 2 p.m. Each person Modern settlements on the edge of the Jarawa reserve. The Andaman Trunk Road,

in the Jarawa group was given two which cuts through the reserve, has opened up more areas for settlement.

-coconuts and a bunch of bananas; the

. .«K.- >: :

entire group was then put on boats and, <

escorted by armed policemen, taken back *

*.

into Jarawa territory.

g

. ......... .

...................

At the other end, however, more |

trouble was in store. Just as one of the “■

boatmen was about to return, some of the

Jarawa youth, who were evidently

incensed by the way they had been treat

ed that afternoon, seized the boatman’s

bamboo pole as he was pushing his boat

into the river and tried to haul him ashore.

U. 4

■

The shaken boatman said later that

•I « : |

.•

■

evening: “I have interacted with the

Jarawa people for 12 years, but for the

first time in my life I was afraid. I did not

know what they would do to me.”

However, some of the older women

of the tribe, who had known the boatman

• i j /_

7 ■ ■ ■" •

■. ■ ■ • •

W

for long, admonished the youth and

forced them to let him go.

Had any bodily harm been done to

the boatman, the consequences would

have been unpredictable: the settlers, sion can be eased if the setdements of the land. Since the political system goes with

already restive over the constant “intru- outsiders are removed from in and around the number, no political party is in a posi

sion” by Jarawas, might well have retali- the Jarawa territory. But this requires tion to contradict their demands.”

The numbers, clearly, are working

ated violently.

tremendous political will and understandagainst the Jarawas. After all, 250 indi

Administration officials admit in pri- ing, which is absent,

vate that they are unable to do anything to

If anything, the weight of political viduals do not count for much in the

ease the tension between the tribal com support is on the side of the setders, as is political system. For the Jarawas, howev

munities and the setders. The two groups evident from a statement made in the Lok er, this battle is not about political power;

are locked in a tussle over land rights, and Sabha in 1990 by the Congress(I) mem- for them it is literally a struggle for sur

the atmosphere has been vitiated by some ber of Parliament from the islands, vival and against extinction. And if their

administrative policies of the past. The Manoranjan Bhakta. He said: “... Job- land rights and other needs are not

Jarawas, as the original inhabitants, have seekers (settlers) who have come (to) the respected, they might very sodn go down

the first right over this land, but not many island are now serious contenders for as another ofthe lost races ofhumankind.

allotment of

ofhouse

house sites

sites and

and agricultural

agricultural

people are willing to concede this. The ten- allotment

r------

*•

-

«

•

«.

«

•

jli

.1 ...IAt.

________ ___

I

K

||0

■’t,

•<

■

1

:

J

.

1

I p t

FRONTLINE, JULY 17, 1998

71

EMBRACING DISEASE

In October 1997, a new chapter began in the history of the is the Andaman Trunk Road (ATR) that connects Port Blair

remote and ancient tribe - the Jarawa of the Andaman islands, to the north of the islands. The ATR cuts through the heart of

From being a hostile, uncontactable community, they took their Jarawa territoiy and has been the single most significant

first step out of their remote forest home- to interact with the factor in bringing in more outsiders closer to the forest home

‘settlers’, the people from mainland India who have settled of the Jarawas and the Jarawas themselves. It has encouraged

along the forests that are their home.

encroachments into and exploitation of resources from inside

In August earlier this year, less than two years since the Jarawa reserve. From the veiy beginning environmental

they first stepped out, the worst had begun with the death of a groups had been opposing the ATR, but their opinion was

young woman of the community that is presently afflicted with always ignored. “Closing the ATR and putting an end to the

a severe epidemic of measles and other infections. The first indiscriminate interaction between the Jarawas and the

death was reported on 16th August, with the death due to acute settlers would appear to be the only way to save this ancient

broncho-pneumonial congestion of an young Jarawa women tribe”, says Acharya. According to him the Directorate of

nick-named Madhuri by the Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Shipping has the resources (boats and manpower) to put in

Samiti (AAJVS). It however took more than a month for the use as an alternate route between Port Blair and Middle and

news to come out when around 30 Jarawas were admitted to North Andaman islands. They have the wherewithal to taking

the GB Pant Hospital on the 21st September. At the time of care of the entire load of passenger and cargo traffic that uses

going to press, 59 Jarawas of the estimated population of 300 the ATR by the sea route. This option needs to be urgently

were in hospital suffering from measles, post measles broncho- looked into and all support that may be needed to make it

pneumonia infections and conjunctivitis. There also is the operational should be immediately provided.

possibility that pockets of infection remain deep in the forest

Also significant in the context is a writ petition filed

and more of the tribe members may get infected. “It could well recently by a local lawyer (though before the outbreak of the

be the beginning of the end”, says Samir Acharya of the epidemic) asking for the rehabilitation of the Jarawa. This

Society for Andaman and Nicobar Ecology (SANE), the 1st suggestion has been opposed by various Indian groups

bring die episode to light

including SANE and Kalpavriksh. Reputed anthropologists

What is very worrying is that the history of the from around the world whose expert testimonies were

Andaman & Nicobar Islands is replete with the decimation of compiled by the London based Survival International and

such tribal communities by diseases that they contracted after recently placed before the court in Port Blair via an

contact with the outside world. The most chilling example is intervention that was filed by SANE, too have argued that

that of the Great Andamanese. Hundreds of them died in the Jarawas should be allowed to lead their traditional lives

epidemics of pneumonia in 1868, measles in 1877 and in the forests and any attempts to resettle / rehabilitate would

influenza in 1896. Combined with other factors like massacre only lead to disaster. Discussing the health related

by the colonial powers and the shrinkage of their forest habitat implications. Dr. James Woodbum of the Dept of

because of deforestation and settlements, they were reduced Anthropology in the London School of Economics and

from a population of around 5000 in the earlier part of the 19th Political Science points out that when a isolated community

century to less than 30 today. A similar devastating outbreak of with low population density (like the Jarawa) comes into

measles has also been reported amongst tribal communities contact with one of high density (like the settlers), the

from around the world, the better known being that of the isolated group will become in and many may die. Some of

Nambikuara tribe from Brazil. Following an epidemic in 1945 the diseases, measles for example are density dependant, and

the 10,000 strong community was reduced to less than 600 do not take root in a population with low density. When an

individuals.

isolated community comes into contact with outsiders.

The outbreak of the disease is an outcome of the because they have not acquired immunity in childhood, they

policies and attempts of the administration to establish friendly are likely to struck down by one illness after another. First

contact with this hostile community, that had always shunned they will be weakened, and if the next illness strikes during

any interaction with the outside world There still are opinions this period, people will die. “It is not unusual” he warns, “for

that the Jarawas should be assimilated into the modem world, 50% or even more of the population to die in the first months

but it is clear, that it is exactly this contact with the outside or years of extensive contact”

world that is rapidly pushing them towards annihilation.

Whats happening with the Jarawas today is proving to be

Also the most pressing question is what should be exactly what had been predicted and unless some of the steps

done now? The present medical treatment is only going to work at correcting the situation are not taken urgently we could

in the immediate short term, and more concrete, sustainable well be witnessing the pushing of another race of humankind

steps are urgently needed if further outbreaks of even worse into history.

diseases like TB or Hepatitis are to be avoided. One of the

biggest vectors of outside intervention into the Jarawa territory Unpublished. September 30. 1999

Qn/nn/iann

i INDIGENOUS PEOPLE

2

Delivering the Jarawas

CD

3

I

w

UJ

For the Jarawa tribal population of the Andaman islands, a court order

“fe’brings hope of protection from the "civilised" world.

X2

j. i

O

/Ax

.AAA-/A'A.

;;

lllo

'.

■

'

H

-A:-

' 1

FL

I

.

•

■

■■

T:

\

'

1.74

A Jarawa tribal person and others on the Andaman Trunk Road in the Middle Andamans.

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

A^OURT cases involve complex

v_yprocesses, which sometimes take tra

jectories of their own and reach destinationsnotquiteintendedatthetimeoftheir

initiation. In one such instance, an order

that the Port Blair Circuit Bench of the

Calcutta High Court issued recendy has

turned out to be to the benefit ofthe indigenous Jarawa community of the Andaman

islands.

The case had its origins in an intrigu

ing development that was noticed in

October 1997 - a drastic change in the

lifestyle and attitudes ofthe forest-dwelling

Jarawas who were previously extremely

hostile to outsiders. For reasons that are not

yet clear, the Jarawas voluntarily broke

their circle of isolation and hostility and

came out from their forest home to have

peaceful interactions with the settler communities that live on the forest’s edge

{Frontline, July 17, 1998).

Almost overnight, the until then feared

and mysterious Jarawa became a subject of

FRONTLINE, AUGUST 31, 2001

intense curiosity. People travelled to the

margins of the forest to catch a glimpse of

the Jarawa, and a small industry was created out of this. The impression gained

ground that there was not enough food in

the forests to support the community,

Consignments of bananas, coconuts and

papayas were sent in regularly and even airdropped into the forests.

The end of the hostility of the Jarawa

also i saw the increased exploitation of

resources from the Jarawa forest reserve,

Sand mining from the beaches on the western coast of the islands and poaching and

removal of non timber forest produce

(NTFP) from the forest habitats increased

drastically.

All this while a few anthropologists,

tribal rights activists and environmentalists

kept arguing that outsiders had to be

stopped from contacting the Jarawas, that

providing them food was not the solution

and that the violation and exploitation of

their forest habitats had to be stopped.

It was in this context that Shyamali

Ganguly, a local lawyer, filed a writ petition before the Circuit Bench in May 1999.

The petition, a classic example of a move

undertaken with the right intentions but

seeking the wrong solutions, asked for the

administration’s help to bring the Jarawas

into the mainstream and improve their

lives. The examples of the Great

Andamanese and the Onge (two other

Andamanese tribal communities) were

held out to explain how this could be done.

But surprisingly, the petitioner failed to

notice that both these communities are on

the verge of being wiped out, primarily

because of attempts to ‘civilise’ and take

them into the mainstream, made first by

the British and then by the governments of

independent India. The petition also asked

that the Jarawas be relocated in another

area, which would then be all theirs,

At this juncture the Port Blair-based

Society for Andaman and Nicobar Ecology

(SANE)

(?

* ? ’T intervened. A vocal advocate of

environmental protection in the islands,

SANE has played a crucial role in fighting

for tribal rights. “What was asked for in the

petition would have meant certain death

for the Jarawas,” says Samir Acharya of

SANE. SANE largely disagreed with the

65

w

^^'3- - ?

E

from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) in

South Asia, and of Amazonian tribes in

Latin America.

-- ------Dr. Marcus Colchester of the Oxford

based Forest People’s Programme argued

•A

that the relocation of the Jarawas could

even be termed illegal under the

,

» rt •.

H Ml KM two.-1 •

1.

International Labour Organisation’s

(ILO) Convention 107 and Articles 7 and

10 of the United Nations Draft

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples, which prohibit “the forcible

removal of indigenous people from their

lands...” and “any form of population

transfer which may violate or undermine

.'

their rights...”

On the issue of health, Dr. James

Woodburn of the Department of

Anthropology in the London School of

On the Andaman Trunk Road, at the entry point to the Jarawa Reserve in South

Economics and Political Science pointed

Andaman island. (Below) The primary health centre at Kadamtala in the Middle

out that “when a previously isolated com

Andamans. A number of Jarawas who contracted diseases through contact with

munity with low population density (like

members of the settler communities outside the reserve, have been treated here.

the Jarawas) comes into contact with one

of high density (like the settlers), they are

particularly vulnerable to diseases like

measles against which they have not

acquired any immunity in childhood.” He

also pointed out that this could be the main

reason for the death of a large number of

the Great Andamanese community in the

19th century and of the Onge afterwards.

It was almost as if Dr. Woodburn was

looking into a crystal ball. A couple of

months later, in September 1999, an epi

demic of measles hit the Jarawa tribe. By

the third week of October, 48 per cent of

the estimated Jarawa population of350 was

suffering from disease and ill-health. The

affected people were treated mainly at the

primary health centre (PHC) in Kadamtala

in the Middle Andamans and at the G.B.

Pant Hospital in Port Blair. There were

even reports that a couple of them had died

in the forests. These reports could not be

corroborated, but clearly the worst fears

about their safety seemed to be coming

true.

Fortunately, a team of doctors com

views of the petitioner, particularly in the that the J arawas should be allowed to main

matter of relocating the Jarawas, which it tain their traditional lifestyles in the forests prising Dr. Namita Ali, Director of Health

felt would be disastrous for the tribal com and that any attempts to resetde or reha Services, Dr. Elizabeth Mathews,

Superintendent, G.B. Pant Hospital, and

munity. Most important, it requested the bilitate them would lead to disaster.

Dr. R.C. Kar, the medical officer in

“__

Historic___precedents involving the

court to order the removal of all encroach

ments, camps and outposts from theJarawa relocation and sedentarisation of tribal Kadamtala, did some commendable work,

reserve and an inquiry into whether the peoples (particularly in island cultures) and not a single casualty was reported

Andaman Trunk Road (see box) ought to have often led to their complete destruc- among those Jarawas who were admitted

be closed to traffic and alternative transport tion...,” explained Dr. Mark Levene of the to the hospitals.

Department of History, University of

routes explored.

A S for the court case, a six-member

Help also came from Survival Warwick, United Kingdom. Levene, a

International, the London-based tribal research scholar working in the area of jtYexpert committee established by the

rights organisation, which contacted eight genocide in the modern world, cited exam- court in February 2000 submitted its

of the world’s leading anthropologists. pies of such genocide in different parts of report six months later, in August. The

Their signed testimonies, which were the world - of Tasmanians by the British committee had the Chief Judicial

placed before the court, unanimously said settlers in the 19th century, of Chakmas Magistrate of Port Blair as its member-sec-

WWOBMli ; I-

£■■1

IfifJAWA AREA '■

■

'oi

66

FRONTLINE, AUGUST 31, 2001

n

retary. Other members included two

anthropologists, Dr. R.K. Bhattacharya

and Kanchan Mukhopadhyay from the

Anthropological Survey ofIndia (ASI), and

three doctors, Namita Ali, R.C. Kar and

Anima Burman from Port Blair.

The committee pointed out that a pre

liminary study by the ASI had indicated

that the forest had enough food resources

to provide for the Jarawas and that there

was no food shortage; that they continue

to be susceptible to many infectious dis

eases and that vigilance should not be slack

ened; that the maintenance of the

Andaman Trunk Road and procurement

of wood for the purpose regularly degrad

ed the forests; and that illegal fishing,

poaching and removal of NTFP from the

Jarawa reserve were happening regularly.

Many other conclusions of the committee

were reflected in the order issued on April

9 in Port Blair byJustice Samaresh Banerjea

and Justice Joytosh Banerjee. A detailed,

60-page written order in the matter came

from Calcutta more than six weeks later,

on May 28, 2001.

The court has directed the formation

of an expert committee to look into the

matter and given it six months from the

date ofits formation to come up with a plan

to deal with issues related to the Jarawas.

The order also made a special reference to

“Master Plan 1991-2021 for the Welfare

ofthe Tribes ofthe A&N” prepared by SA.

Awaradi, former Director, Tribal Welfare,

in the Andaman and Nicobar administra

tion. It indicated that the document should

be taken into consideration while formu

lating the final policies. For the interim

period, it has ordered a number of steps to

be implemented on a war footing.

The court has directed the local admin

istration to stop poaching and intrusion

into Jarawa territory and to prevent its fur

ther destruction by encroachment and

deforestation. It ordered issuance of an

‘appropriate notification clearly demarcat

ing the Jarawa territory’. This would great

ly help law enforcement, particularly in the

detection and removal of encroachments.

The court also ordered that penal measures

be taken against encroachers and poachers,

and importantly, against those among the

police and civil authorities who are negli

gent in this regard.

Accepting the recommendations of the

expert committee, the court directed that

medical aid be given to the Jarawas only

when they came out ofthe forest and sought

it and only to the extent necessary. It asked

for periodic medical programmes for the

Jarawas in their own territory and only to

the extent necessary so that they need not

FRONTLINE, AUGUST 31, 2001

Questions about a road

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

The ATR is a perfect example of

------------------ -----------------------short-sighted planning. First, it is not the

HTTIE Andaman Trunk Road (ATR) best way to travel in the islands. Most of

1 connects Port Blair in South the setdements in the Andamans are sitAndaman to Diglipur in North uated on the coast, so the most logical

Andamans, covering nearly 340 kilome- and immensely cheaper mode of transtres. Across the world, road construe- port that should have been developed is

tion, particularly in rainforest areas, has marine transport,

Every year crores of rupees and

been one of the biggest reasons for the

destruction of forests and their indige large quantities of timber go into the

nous residents. The story of the ATR is maintenance of the road. SANE esti

no different. Directly and indirecdy, it mates that a minimum of 12,000 cubic

has contributed to the destruction ofvast metres of timber from the evergreen

areas of evergreen rainforests in the forests is burnt annually for this purirely affected

pose. Compare

this with the official figAndamans, which has sevei__,

x

_

the Jarawas.

ure of 70,000 cu m of timber that is

Work on the

the road

road began

began in

in 1971,

1971, logged in the entire islands today, and

and it was violendy opposed by the one gets a sense of the destruction

Jarawas. But the work continued and the caused by the ATR. There is not

entire stretch was completed recently,

itly. enough traffic on the ATR to justify

Huge amounts of money went into its such a huge expenditure.

But the question, as always, is the

construction which could have been

same: Who’s listening? ■

avoided in the first place.

Maintenance work on the Andaman Trunk Road inside the Jarawa reserve.

Large quantities of timber are burnt for the maintenance of the road.

come out from the forests for such aid.

Significandy, the court directed that until a

policy on dealingwithjarawas was finalised,

no new construction or extension of exist

ing construction should be undertaken in

the Jarawa territory and no extension was

to be made to the Andaman Trunk Road.

The order has been welcomed by envi

ronmental and tribal rights activists famil

iar with the situation in the archipelago. It

is considered a very positive order, and one

with great potential for safeguarding the

future of the tribal people here. Ensuring

its implementation is the next big chal

lenge, and a lot will depend on how and

with how much sincerity this is done. H

In association with The Transforming Word

Pankaj Sekhsaria is a member ofthe environment

action group, Kalpavriksh.

67

12

I INDIGENOUS PEOPLE

A people in peril

The Onge tribal community of Little Andaman, which is on the verge of extinction, faces a serious

threat from ill-conceived development plans and their attendant maladies.

PANKAJ SEKHSARIA

/""AN February 26, 1999, Andaman

Herald, a Port Blair newspaper,

reported that the bodies of two youngj

members of the Onge tribal comitmunity

were found floating in a creek near their

Dugong Creek settlement on the Little

Andaman island. The young men had

been missing for a few days apparendy

after having gone turtle-hunting. The

cause of the deaths was not known, but

drowning was ruled out. The Onge peo

ple are excellent swimmers and sailors

and there is no record of an Onge drowning in a creek. The newspaper said that

foul play was suspected as the post

mortem and the cremation were done

with undue haste. One of the dead men

was a constable with the Andaman and

Nicobar Police, according to the news

paper report.

This piece of news was inconsequential except to a ffew concerned people,

This incident, however, assumes extraordinary importance in the light of the fact

that the Onge issue has a complex background and history,

'"I ^HE Onge community is one of the

1 four Negrito tribal communities that

still survive in the Andaman islands. Its

population today is around a hundred

individuals; the 732 sq km of the thickly

forested island of Little Andaman is the

only area they inhabit. The community

is on the brink of extinction.

Additionally, one of the dead youths had

reportedly complained to an adviser to

the Planning Commission, who visited

the island in the recent past, about the

resource depletion that the community

faced owing to illegal timber logging and

poaching in the forests.

The Onge community had flourished

in the Andaman islands for centuries. Not

much is known about the community,

but whatever is known is proof enough

of the astonishing depth and diversity of

its knowledge (see box).

A powerful two-pronged attack - on

the natural resource base that sustains the

community and on the culture of the

community - has over the past three

decades slowly but surely pushed Onges

to a point of no return. Recent investiga

tions in Little Andaman have brought to

light: some glaring irregularities, and the

itwo reported deaths are believed to be the

The tribal community of Onges that had flourished in certain areas of the Andaman archipelago for centuries consists of only

a hundred or so individuals today.

FRONTLINE, MAY 7, 1.999

67

13

Cape Price

q.

latest and the most obvi

• Andaman and Nicobar

0

o r ,

ous consequence of the

i Forest Plantation and

o \

:

process.

! Development

North

0

The story of the Onge

• Corporation

(ANFAndamai

i PDC), which is the sole

people’s alienation begins

Diglipur

in the late 1960s, when

• agency responsible for

the Government of India

timber extraction here. In

p

planned a massive devel

1976, theANFPDC pre

i‘(?

opment and colonisation

sented its Project Report

1 Middle

for

Logging

and

programme for the union

Andaman

Marketing of timber from

territory of the Andaman

Port Andam;

the forests of Little

and Nicobar Islands, in

Andaman. It wks estimat

complete disregard of the

ed that a total of 60,000

fragile environment of the

Area de notified

I - 'I as tribal reserve

ha of the island was avail

islands and the rights of

able for logging and that

the tribal communities. A

60,000 cubic metres of

1965 plan, prepared

timber could be extracted

specifically for Little

annually from 800 ha.

Andaman, proposed the

a

Here again was anoth

clear-felling of nearly 40

er

clear

violation of the

per cent of the island’s

<=0

South

Onge tribal reserve.

forests, the bringing in of

Andamai

When 52,000 ha of the

12,000 settler families to

the area and the promo

island’s total area of

tion of commercial plan

73,000 ha was already a

Port Blair

Q

- &

tations, such as those of

tribal reserve, how could

60,000 ha be made avail

red oil palm, and timber

Rutland

<

able for logging? The

based industries in order

0

Corporation should have

to support the settler pop

c>

ulation.

limited its operations to

Had the plan been

the 19,600 ha that had

Duncan Passage

implemented fully, it

been leased out to it. With

! 1,600 ha being under red

would have destroyed

Little Andaman and

I oil palm plantation, the

caused the extinction of

actual area for logging was

the Onge tribe. Logistical

I even less, at 18,000 ha.

Andaman

Sea

tittle

problems, lack of infra

! This meant that the

Andaman

structure and a revision of

Corporation should have

i logged only 18,000 cu m

policies over time ensured

that the destruction was

• of timber from an area of

< 240 ha annually. The average for the actu

not complete. However, in the concep

< al logging over the last two decades, how

tion and planning of the development

programme, the Onges were sidelined

ever, is much higher, at 25,000 cu m of

and the violations started.

J timber from an area of 400 ha annually.

The government team that suggest

Furthermore, a working plan has not

I

been prepared for the logging operations

ed the development programme ignored

the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of

on Little Andaman. Besides, the contin

ued logging contravenes a Supreme

Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (ANPACourt order of 1996 stopping all logging

TR), which had in 1957 accorded the sta

in the absence of a working plan. The

tus of a tribal reserve to the entire island

of Little Andaman. Further, about

Forest Department has justified the log

20,000 hectares (roughly 30 per cent) of

ging on the basis of its 1976 project

the island was denotified from its tribal

report. However, the legality and validi

reserve status in two stages, in 1972 and

ty of this report are open to question.

1977, still leaving 52,000 ha as an invio

Significantly,

the

Deputy

Conservator of Forests - Working Plan

lable tribal reserve. Many of the proposed

projects were also taken up for imple The coordinates of a logging site as

(DCF-WP) ofthe Andaman and Nicobar

mentation. These included a 1,600-ha they appear on a global positioning

Forest Department is now reportedly

red oil palm plantation and a major tim system (GPS) reception unit which

preparing a working plan for the forests

ber extraction operation that continues indicate that the site may be located

of Little Andaman. This clearly contra

even today.

either on the border of the tribal

dicts the present stand of the

The Forest Department leased out reserve or be further inside the

Department, which claims that the

19,600 ha from the denotified area to the reserve on Little Andaman.

equivalent of a working plan already

I

68

FRONTLINE, MAY 7, 1999

<

in

<6

*

<

<

I§

I

'h

>41

I

W i ■

W

r

^5:

r' f<\.-

vl

w- ■'

igoyM

r or

' w ■

iiw

fc. Jla^lk

- ji•

bl

V-i

rfl ■FplBWfen

I

¥J- ■;

rJ'\

7x>&,

- 1 ww il

A

f-

I

>7^-7^;/; < ? .; 7?<; 7 ;

: ' .''

". 7 "X' !<

Jr

--7 ,'"' a

77'i=5S7®777ft ? .- I BlliWllW

'

'i !

‘..

..

.. v:--] ‘^’■: ■

sir 1 ■'

««i

i

ri

;.r ■' - ^rri \rribw

j;z7r.

'jb ■ -

,

11

rj " 1. ■..: < iUi i I j3«

;7. 'WS

Forests burnt and cleared for the creation of settlements and farms inside the Onge reserve.

(Below) A logging camp inside the reserve.

,;ffy ijji jn

gyraaa

A precious heritage

PAN KAJ S EKHS ARI A

—— ------ -——---------

some vigorous chewing they are quickly reduced to a greenish pulp, which is

smeared all over the-body...another;

f 14HE ethnobotanical knowledge of huge mouthful is chewed on the way

1 the Onge tribal community is stag- up and spat at the bees to make sure

gering. Italian anthropologist Lidio . that they.will be deterred... the bees fly

Cipriani, who studied the community away from the comb without stinging'

in the 1950s, was among the? first of and the honey can be cut out...” caus' many experts to acknowledge this ing harm neither to the collector of

Onge heritage. He wrote in 1966: “In honey nor to the bees.

their continual search for food the

Disregarding such knowledge,.

Onges have acquired botanical and attempts are made to impart modern u

zoological knowledge which seems technology to the Onge people. A few

almost innate, and they know of prop- years ago the Fisheries: Department

erties in plants and animals of which. posted a fisheries inspector and two

we are quite unaware. Nearly every day fishermen at Dugong Creek to teach

on Little Andaman I came across this. Onges modern methods of fishing/'

I had only to draw a rough sketch of an The fishermen adnutted later that, they

animal and they knew at once where it had much to learn from the tribal com. could; be-found; it was only, thanks to: munity about fishing in the waters of

them that I was able to find the-vari- the island.

■ous amphibia,: which subsequently

More recently, ua' controversyproved to be new species.”

erupted when senior researchers from

Among the best-known examples ■ the Indian CounciT of Medical

of Onge: knowledge. is the method Research (ICMR). tried to patent a disOnges use to extract honey from the covery that would probably lead to a

Elephants at work In the huge timber

hives of the giant rock bee. In order to cure for cerebral malaria. The issue

yard In Hut Bay on the Little Andaman

ward off the bees, they use the leaves of; attracted international attention. The

island.

a plant, which they call ‘tonjoghe’ source of the medicine in question is a

{Orphea katshalica). To quote Cipriani plant that the Onge use to treat fever

m

again: “...the juice of a certain plant and stomach disorders.

sb''5

they, call tonjoghe... has the power of

The size and.nature of the wealth Oo

deterring bees, and this knowledge that lies in the island home ofthe Onge

•

(which) has been handed down from people are largely unknown. What is

generation, to generation, is. applied more important is that if the present 1o

with delightful simplicity...There are situation continues, the Onge people; 5ra

bushes of tonjoghe everywhere...the may not survive for too long and with 3o

Onges simply grab a handful of leaves them will go a huge bank of invaluable

and stuff them into the mouth. With knowledge. ■

■ I

----- — '

I

■ I

CD

exists.

The Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas

As if this was not enough, the Samiti (AAJVS), the official tribal welfare

Corporation has gone a step further; it is body of the administration, introduced

logging within the tribal reserve, making welfare measures that were completely

a mockery of the law and also the rights unsuitable for the Onges. Foodstuffs such

of the Onges. Maps available with the as rice, dal, oil and biscuits were introANFPDC and the Forest Department

x

duced to a community whose traditionhave logging coupes dated 1990 onwards al food included the meat of the wild boar

marked clearly within the tribal reserve.

and turtle, fish, tubers and honey. The

Even as tthese

‘

violations occurred, agency even offered each adult 250 gm of

thousands of outsiders were settled in tobacco as a “welfare” measure. In a bla

Little Andaman. The settler population tant attempt to move the forestry opera

grew rapidly; from a few hundreds in the tions deeper into the forests of Little

1960s to 7,000 in 1984 and over 12,000 Andaman, authorities have sought to setset

in 1991, displacing Onges from some of de the nomadic Onges at Dugong Creek

their most {preferred

r

' 'habitats.

'•

THut

T "

,

• the

’ northeast

'

.....................

Bay,

in

of.the

island and ......

at South■

the main town in the island,

is an exam- Bay at the southern tip. Wooden houses

-----------------ple.

on stilts and with asbestos roofing were

70

The survival of the Onges can be

ensured only If the present

development policies v/s-a-v/s the tribal

people are reviewed with sensitivity.

FRONTLINE, MAY 7, 1999

tb

K

F

w

1

,

•

Little

Andaman:

J?

t ■*'

E -fe

on p

wBWfc;

I ■

7 the

i Onge

n

of

672.

departmental Team on Accelerated

Development Programme for the A&N

Islands’, Ministry of Rehabilitation,

Government of India.

1970: Timber extraction begins. 1

1971: Population of the Onge 112.

1972: First amendment to the trib

al reserve on Little Andaman.

1974: Forest Depanment assesses

constructed for them at these places, become addicts. This addiction is now

These structures were not suited for the exploited - the Onge people exchange

hot and humid tropical environment of with the setders valuable resources such

the islands and the Onge people preferred as honey, turde eggs, wild boar meat and

to live in their traditional huts in the for- ambergris for liquor.

est nearby.

Logging operations have also helped

Simultaneously, attempts were made open up the forests, encouraging further

to introduce a cash economy in the com- encroachments into the tribal reserve,

munity, which did not have even a barter Consequently, illegal activities such as

system. Ill-conceived schemes, such as the poaching have become rampant - result

raising of a coconut plantation (in which ing in a drastic decline of rare creatures

the Onge people were made workers), such as the monitor lizard, the dugong

cattle-rearing (the community does not and the endemic Andaman wild pig. All

consume milk) and pig-breeding, were these creatures are not only important

introduced. All of them failed. sources of food and nutrition for the

Environmentalist Bittu Sahgal noted that Onge people, but play an integral role in

during one of his visits to the Onge set- their culture and society. Their unavaildement a few years ago, the Onge people ability leaves gaps that cannot be filled,

were found being used to do menial

It is clear now that the survival of the

chores, such as fetching water for welfare Onges can only be ensured if the present

workers appointed by the administration, policies vis-a-vis development and the

A visit to the Onge settlement of tribal people are reviewed with sensitiviDugong Creek has become mandatory ty. Serious attention must be paid to what

on many a VIP itinerary. Not only are the the tribal people have to say and an honOnge people expected to perform for the est attempt made to find out what they

pleasure and entertainment of the VIP, want. There are no signs however of that

but they are put to work weeks in advance being done.

to tidy up the settlement.

At a meeting of the District Planning

The settler communities, which have Committee held in Port Blair in

been handed over the lands and resources November 1998, the Onge representaof the Onge people, have not treated tive, Tambolai, complained that settlers

them any better. They exploit and look living in the areas near their settlement

>ling them. A major point he

down upon the tribal people. Alcohol was were troubling

introduced and many Onges have made was tthat finding wild pigs in the

FRONTLINE, MAY 7, 1999

1975: Forest Department initiates

workfen the fed oil palm plantation.

1976: The Andaman Adim Janjati

Cotpoudo. pwpowl far losing

forestry operations in Little Andaman, fe

pjs." F“

^j^fe^-Second dendtificaton of.the

tribal reserve on Little Andaman.

1977-79: More outside families set-

W 19^L d■ Y' S q = ? s I00’

pologistVishvajit Pandya.