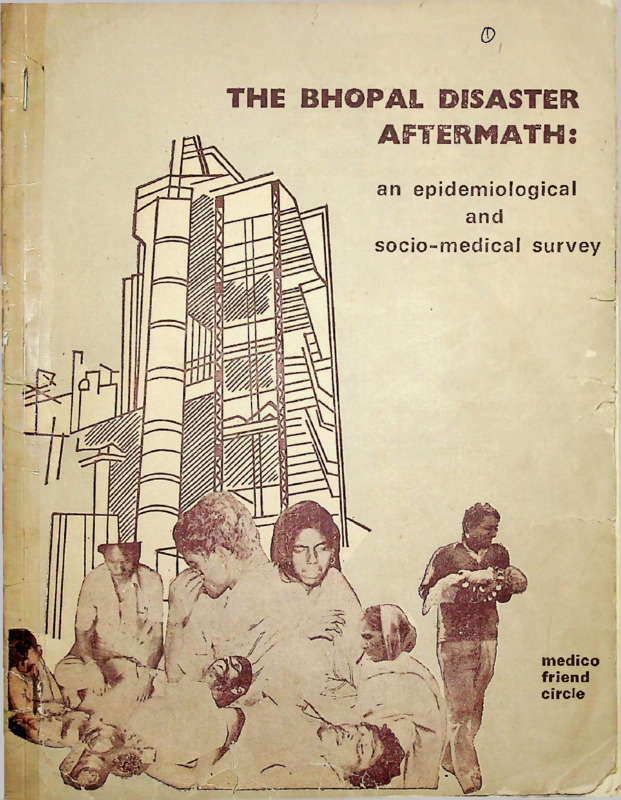

The Bhopal Disaster Aftermath: an epidemiological and socio-medical survey

Media

- Title

- The Bhopal Disaster Aftermath: an epidemiological and socio-medical survey

- extracted text

-

fl)

THE BM0PA1 DISASTER

AFTERMATH:

• .

an epidemiological

and

’1

socio-medical survey

r ■

V

■ p

I

i

i

~T|

medico

friend

circle

/13d7]

Dedicated to the thousands

who died or were disabled

by the Bhopal Gas Disaster

--the worst industrial

accident in recorded history.

With a resolve

to prevent

medical research

from becoming an instrument of

exploitation of human

suffering.

With a determination

to make

medical research

an expression of

human concern.

(

I

rice Rs. 8

-

-MUMI-- HrAfTH

THE

CFf (

BHOPAL DISASTER

AFTERMATH

an epidemiological and socio-medical study

15 - 25 March 1985

medico friend circle

r

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

i

To,

The people of Jaya Prakash Nagar and Anna Nagar for their warm and

welcoming attitude which greatly helped our study.

Rukmini Bahen and friends of SEWA and Ramachandra Bhargava

and colleagues of Gandhi Bhavan for their hospitality in BhopalThe Preventive and Social Medicine Department of Baroda Medical

College fortheir technical cooperation.

Friends of the Gujarat Sangharsh Vahini (Rashmi, Ambarish, Trupti,

Rajesh and Kaumudi) for their help in tabulating and analysing data.

Jan Vigyan Samiti, Kanpur and all our generous friends and members

for their donations, big and small.

A large circle of mfc friends and contacts for their support and

encouragement, and for their critical comments on the draft manu

script of this report.

1

i

•

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

47/1, (First F>r > 3t. Marks Hoad

BANGALO.iE-5u0 0Q1

ii

J

ERRATA

Page

Line

1

3

'where' should read 'were'

6

34

'except' should read 'accept'

6

40

'polo' should read 'pool'

13

19

'weight (ii)' should read '(ii) weight'

43

24

'rigorouly' should read 'rigorously'

46

14

'Hindu' should read 'The Hindu'

52

16

'Gag' should read 'gas'

56

16

'muscie aches' should read 'muscle aches'

62

36

'paramteers' should read 'parameters'

63

31

'on' should read 'of'

65

7

'victims' should read 'victims'

TABLES

Page

18

Table No.

1C

'Others' in Anna Nagar 13.36 should

read '1 3.86'

24

3A

Blurred vision/photophobia

J P Nagar 77.02 (144) should read

'77.02 (114)'

A. Nagar 33.40 (53) should read 38.40 (53)

32

60

After J P Nagar468 should read (46.8)

35

7

15-44 Female FEV (Lit) in A.N. 2.25 (2.42)

should read '2.25 (0.42)'

■ .1

J

AT A H H 3

A,

oniJ

ses9

S'

c

f

I

'Jqeoos' bsai biuoris ‘jqaoxe’

AS

0

Mooq' bsoi bluorte %oloq‘

OA

8

‘tcigiew (iif bssi bluorte ‘(ii) idpiew*

er

sr

■ v‘ bf ci hi *

vleuoioeir bsei bluoris 'vluoiooii1

:

SA

ubni I sriT' Jssi b’uorls ‘c ?n:H‘

r- -

‘asQ' beoi bluorla 'ob£

er

£8

‘?9(kr '•Heurn' bsei bluoris 'aodo- 9i .cjr.c

dr

uU

?6iBq'bssi bluorle'siosjfns\ sq*

d£

So

'to' bssi /Jucru no*

re

v

co

'amiror/' bsei bloods 'emi.:?;.

i

I

83

S

3 ? J S AT

d

■oM ©IdBT

i. n - -

or

8F

AS

A£

bluotfg 8dA ,cn:.;1 9 L i: ;A

03

££

(Ji J) V33 916G1S" A-8 F

V

5S

’38.£ F‘ bsei

Gidodqotortq.noiaiv bsnulS

bid bluorie (AM) £0AV ibqbH S L

‘(MT) 20 VV

(£8 . GA.3g b69i bluorie (£•:•) '

(8.8;)

(£A.£) g2.£ .H.

Sc sr-.-'; .-

'(-‘•.0} c£.£ bs^> h.’uort^

■

.

i

THE STUDY TEAM

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

Ashvin Patel (Baroda)

Co-ordinators

Anil Patel (Mangrol)

J

Daxa Patel (Mangrol)

Nimitta Bhatt (Baroda)

Manisha Gupte (Bombay)

Padma Prakash (Bombay)

Mira Sadgopal (Hoshangabad)

Marie D'Souza (Nandurbar)

Shirish Datar (Karjat)

Anant Phadke (Pune)

C. Sathyamala (New Delhi)

and three volunteers from Baroda Medical College

1.

2.

3.

Ramesh Durvasula

Hemant Vithalani

Bipin Patel

iii

I

PREFACE

The Bhopal disaster has been an unprecedented occupational and environ

mental accident. Equally unprecedented have been the imperatives for relief, re

habilitation and research in the aftermath of the disaster.

The local situation has been extremely complicated and dynamic. While

health service providers and researchers have had to face many medical challenges,

government and voluntary agencies involved in relief and rehabilitation have had to

face many logistical and organizational challenges.

For the medico friend circle too, in its intervention in research and

continuing education strategies in support primarily of voluntary agencies, it has

been both a challenge and a thought provoking learning experience. The experience

of planning, organising, analysing and communicating our research findings based

on a modest study has brought us further in touch with the apathy, vested interests

and status quo factors which obstruct action in favour of the disadvantaged in society.

Having seen the intensity of health problems of the disaster victims and the

inadequacies in the strategies employed to ameliorate them we cannot but help raise

critical comments on all components of the social medical system who are there to

handle such problems.

Our objective, however, is more than critical analysis. Through this

epidemiological study we have tried to make our own small contribution to a better

understanding of the health problems that prevail in the aftermath of the disaster.

We have also made suggestions for a more comprehensive relief and rehabilitation

strategy.

A word of caution here—most of our observations are of the situation as it

existed at the end of March 1985. Six months have passed in the process of ana

lysis, consensus seeking and understanding our findings. During these six months,

many further developments--both positive and negative--have taken place in Bhopal

at the governmental and the non-governmental initiative.

We hope that this report will atleast help to highlight to our readers among

other matters that—

(i)

what people say and feel is as important evidence as what we can discover

through our over-mystified medical technological approach;

(ii)

in the absence of a community oriented epidemiological perspective,

decision making about relief efforts, following a disaster can be adhoc and

often irrelevant; and

(iii)

for research to be relevant to the lives of the people, the findings

and inferences drawn must be communicated to the health service pro-'

viders and the patients themselves through an effective communication

stiategy.

Finally we hope that through this report, we shall stimulate debate, dialogue

and a commitment to a deeper understanding of the problem, leading to more relevant

and meaningful interventions.

Ravi Narayan

Convenor

Bangalore

2 Oct 1985

iv

CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements

ii

Study team

iii

Preface

iv

1.

INTRODUCTION

1

2.

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

3

3.

BACKGROUND : TWO MEDICAL THEORIES

6

3.1 Pulmonary Fibrosis Theory

6

3.2 Enlarged Cyanogen Pool Theory

8

MATERIALS AND METHODS

12

4.1 Sample population

12

4.2 Methods

12

4.3 Building rapport with the people

14

4.4 Plan of Analysis

15

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

16

5.1 Non-responders—some observations

16

5.2 Comparison of samples

17

5.3 Socio-economic profile in the Bastis

18

5.4 Morbidity analysis

21

DISCUSSION

33

6.1 Role of Chronic Diseases and Smoking

38

6.2 Pulmonary Theory : An assessment

39

6.3 Enlarged Cyanogen Pool Theory : An assessment

41

6.4 Magnitude of the Problem : An issue of Damage/Compensation

44

6.5 Thiosulfate controversy

45

6.6 Implication for research

47

4.

5.

6.

v

r

7.

RECOMMENDATIONS

49

7.1 Community based Epidemiological Research

49

7.2 Mass Relief Programme

50

7.3 Listing of the victims; claims for compensation

50

7.4 Health Committees

51

7.5 A communication strategy on health related issues

51

APPENDICES

52

I

Proforma (6 sections)

52

II

English translation of Handout

61

III

ICMR minutes of 14.2.1985

62

IV Study of Medical Relief

65

V

67

People's Perception

REFERENCES

69

ADDITIONAL READING

71

vi

I

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Many months after the Bhopal gas tragedy, conflicting reports kept coming

in from Bhopal. There ware reports that the gas victims continued to present at the

out patients departments with serious physical symptoms and they where getting

very little relief by the standard package of treatment which included antibiotics,

steroids, antacids, cough mixtures, eye drops and bronchodilators.

Doubts were being raised that the disaster victims were developing a sense

of dependence and were exaggerating their symptoms in order to draw more and

more benefits. It was also felt that the first wave of mortality and morbidity

had receded and that there was no significant residual damage and morbidity. The

feeling of ''all was well" was becoming stronger.

In February 1985, another dimension of the human suffering in Bhopal

came to light. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) came out with a

finding that the gas affected population of Bhooal was probably suffering from a

chronic cyanide like poisoning and that the use of an antidote - sodium thiosulfate—

could improve their condition. The situation was, however, further compounded by

a total clamp down of information by local state health authorities.

The medico friend circle (mfc) had decided at the annual meeting in

Bangalore, end of January 1985, to respond to a series of appeals from various

non-governmental groups and to undertake an epidemiological and medico social

investigation with the primary purpose of supporting disaster victims, citizens'

groups and voluntary agencies in their struggle for meaningful relief, rehabilitation,

justice, and for information.

However, at that point the collective knowledge of mfc was too inadequate

(cyanide poisoning was still in the future) for a meaningful formulation of the

pioblem in Bhopal. Naturally the formulation of concrete objectives for the study

was not possible either. This evolved as the study progressed in stages. It was

however felt that the mfc should collect its own field data and get first hand

information about the health status of the disaster victims.

A few mfc members had visited Bhopal in mid-February and had identified

certain urgent areas for action (1).

The team for this epidemiological study was in Bhopal from 15 to25 March

1985. It consisted of a voluntary group of clinicians, doctors working in community

health projects and health activists from different parts of India. During the stay and

subsequently as the collected data was being analysed, it was realised that two

medical theories to explain the continuing symptoms were competing to gain

supremacy :

i) The 'pulmonary' theory which believed that in view of the available

information about the effects of MIC, only extensive lung damage

(leading to diffused pulmonary fibrosis) and direct injury to corneas

of eyes could be expected.

ii) The 'enlarged cyanogen pool' theory which believed that the effect of the

released gases on the patients was to increase the cyanogenic pool inside

their bodies leading to chronic cyanide-like poisoning.

I

Both these theories are explained further in the text. It is important to

realise, however, that this was not a purely academic controversy but a very serious

problem having a direct and immediate bearing on the lives of the people. The

controversy had resulted in the adherents of the pulmonary fibrosis theory (who

dominate the medical establishment in Bhopal) steadfastly refusing to treat the gas

victims on a mass-scale with sodium thiosulfate which had been advanced as an

antidote by the ICMR on the basis of its research findings. Tne net outcome of this

unseemly controversy was that the suffering of the people was continuing without

any relief in sight.

A study undertaken in a situation where two proponents of opposing

theories are busy in a controversy cannot ignore th°se theories. We did not. in

fact we consciously kept this controversy in mind and analysed our findings

accordingly. Needless to add that the study does not and cannot aim to provide

decisive arguments to resolve the controversy fully.

However the critical analysis does not remain narrowly confined to the

merits and demerits of the contending theories only. It goes much beyond that.

The inherent force of the logic of the criticism impinges upon the much wider issues

of weaknesses in methodology, perspective, orientation and setting of objectives of

medical research as it has been carried on in Bhopal. The serious gaps in the very

fabric of research efforts have direct and vital connection not only with the

urgent issue of relief from suffering, damages and compensation to the victims of

the poison gas, but also wiih the issjeof fixing the responsibilities on ell those

who have perpetuated the suffering of thousands of people of Bhopal.

We outline a series of conclusions and recommendations for urgent consi

deration by all concerned.

A summary of this report is also being releasedin English for wider circula

tion and a lay version in Hindi for the gas affected people in Bhopal.

If, through this modest effort we have moved towards the establishment of

a 'people oriented science' and endorsed the peoole's 'right to know', we would

have felt that our efforts were more than worthwhile.

- medico friend circle

Justice is but truth in action and we cannot hope

to attain justice until we have the proper respect

for truth.

—Anon

2

CHAPTER

2

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has initiated over 22

ressearch projects to study the sub-acute, chronic and late effects of the Bhopal gas

disaster. The objectives of the medico friend circle (mfc) intervention in Bhopal

jvaas not to duplicate the efforts of ICMR. We neither have the resources nor me

^c»cess to technical supports that are required for such efforts;nor for that matter the

maandate. We believe that the primary role of organising research linked to relief

anid rehabilitation efforts lies with the governmental and national institutions that

have been established with the tax payers' money.

In January 1985 when we first decided to undertake this study, there was

•isardly any official information available on the health situation of the gas victims of

Blihopal. The clamp down on information was unmistakable. From whatever little

imformation we could obtain, it was clear that people in large numbers were reporting

sy/mptoms like shortness of breath, cough, excess lacrimation, fatigue, headache, loss

off appetite, etc. This was a list of symptoms. Only symptoms, apparently uncon

nected to one another by underlying patho-physiological mechanisms, dominated the

sccene.

Naturally at a meeting in Bombay we first set the following series of

objectives.

(i) Assessing current health status and medico-social problems (ii) Prioritizimg in terms of magnitude and implication for rehabilitation (iii) Identifying health

problems that required health education efforts (iv) Studying existing plan of relief,

reesearch and rehabilitation services and (v) Studying people's perception of these

sservices.

Later on, when the study was in progress in Bhopal, we came across

more substantial

information.

The conflict of two medical theories came

before us in sharp focus and the far reaching implications of this conflict for

relief, rehabilitation, compensation etc. were tentatively grasped in those days.

TThe objective was slowly evolving and finally came to be a thorough-going critique

oof the two medical theories and the implications flowing from them.

Our initial

sact finding, appraisal of information and situation analysis, led us to identify a

sseries of issues of concern: (i) secrecy on any type of data/information on the

(disaster; (ii) secrecy of ICMR research study plans; (iii) absence of open scientific

idebate on research findings, (iv) the vertical, clinical and organ centred nature of

(research projects; (v) the absence of encouragement to non governmental initiatives;

(vi) the adhoc and populist approach to relief and rehabilitation; (vii) the absence

of authentic scientific and research based information for the medical teams

providing services; (viii) the absence of demystified but authentic information to

the disaster victims for their evolving mevament/struggle for a more relevant relief

and rehabilitation programme.

These concerns led to a reassessment of the Bombay objectives and a

series of new objectives emerged to best meet the emerging situation. These were( i) To assess the current health status and related problems of the people

on a sound epidemiological/ community basis;

( ii) To assess the findings in the light of the medical controversy between

'exclusive pulmonary pathology' vs. an 'enlarged cyanogenic pool'

leading/ to a chronic cyanide like poisoning;

3

I

i

(iii) To evolve a critique of the ongoing

programme;

research

and

medical

relief

(iv) To identify factors that have important implications for the relief,

rehabilitation strategy (including claims for compensation);

(v) To assess the people's perception of the ongoing health care services;

(vi) To make suggestions for a more meaningful relief/research/rehabilitation policy.

The health problem situation as it evolved in Bhopal which helped give a

final shape to the objective, has another interesting aspect which bears on metho

dology of the study.

V

During and after the study many have commented that our reliance on>

symptoms is somewhat unsatisfactory, that they are subjective and therefore we are

on shaky ground and that more objective data like bio-chemical measurements,

X-rays etc. as were done by other groups (e.g. the Nagrik study) is missing in our

study, rendering it less solid. This faith and attachment to laboratory tests. X-rays

and other types of 'objective' tests is interesting but difficult to understand.

When predominance of a broad range of symptoms was the only important

fact known and even after the fact of 'enlarged cyanogen pool' came to be known,

what could be the biochemical-pathological tests that could be done in a sample

population so as to make our study more objective and less shaky? The only bio

chemical tests of real value, suggested by the 'cyanogen pool' theory are augmented

output of urinary thiocyanate following intravenous sodium thiosulfate and study of

blood gases. Both these tests were of course, beyond our reach. However, that

should not mean that studies at less sophisticated levels like ours, have no objecti

vity about them.

With regard to X-rays, it should be noted that the place of chest-radiography

is extremely limited. Its only legitimate use is in the detailed follow-up of those

whose pulmonary function studies have shown very significant lung diseases (19).

Furthermore X-ray findings sometimes bear little relation to the patient’s disability,

loss of function or severity of other symptoms (10)

The other test which is of real

value Is pulmonary function tests. The forced vital capacity (F V.C.) and the forced

expiratory volume in the first second (F.EV. 1) are the simplest, most repeatable,

valid and among the more discriminating tests reflecting mechanics of breathing.

They have had most extensive trials during the past 25 years and regression equa

tions for predicted normal performance are better documented than for any other

respiratory test (10,19). We have in our study undertaken these tests.

Biochemical parameters, which are routinely studied in clinical settings

where the problem situation is much more settled and clear-cut, cannot be easily

and automatically used with a view to improve objectivity, in a situation like the

Bhopal gas disaster. This is completely new and unknown territory in so far as

little is known about MIC's effect on the body. To use such parameters would be

like shooting in the dark. These 'solid' 'objective' tests themselves do not

necessarily lend objectivity to any study in such an inherently difficult and ill-defined

problem situation. In doing so we are only reinforcing and perpetuating the popu

lar, mythical notions about scientific objectivity. To study symptoms is not

necessarily to be subjective—but about this later.

4

L

in

*

^4

I

J)

<

Ul

d

>

a

□

t-

(0

CHAPTER 3

BACKGROUND : TWO MEDICAL THEORIES

The disaster that took place in Bhopal on the night of 2/3 December 1984

has been universally accepted as the worst man-made industrial and environmental

accident in recorded history. Forty tonnes of stored methyl■ isocyanate (MIC)

escaped into the atmosphere killing over 2500 people and over three thousand cattle

and affecting over two lakh people according to official estimates. These shocking

statistics do not adequately express the actual enormity of the human tragedy—of the

lives lost, the families disrupted, the people disabled and ill and the thousands

impoverished.

The relief efforts that were initiated soon after were handicapped by the

absence of authoritative information on the released gases; the unwillingness of the

Union Carbide company to part with authentic information; the absence of meaning

ful information among the relevant sanctioning, licensing and inspecting authorities

in the State and the Centre; the lack of preparedness of the local bodies and govern

mental health authorities to handle the unprecedented consequences of such a

disaster and the absence of technical or toxicological expertise on MIC among our

scientific community (1).

In the early hours of 3rd December 1984 when hundreds were pouring in to

Hamidia Hospital seeking medical relief, the beginnings of two medical theories

which would later on compete with each other to occupy the central position were

clearly discernible.

They are going to be the main focus of our report,

try to elaborate on these two medical theories.

In this chapter we will

They are (3.1) Exclusively Pulmonary Pathology Theory, which has

been referred to as 'Pulmonary theory' throughout this report. It is so called be

cause it claims that all the mortality and the prevalent morbidity in the gas hit

population of Bhopal is exclusively due to direct injury to lung tissues which over

a period will lead to diffuse pulmonary fibrosis.

I

((3.2) Enlarged Cyanogen Pool Theory, which for the sake of brevity is referred

to as 'Cyanogen pool' theory' throughout the report. This theory postulates chronic

cyanide poisoning of the victims due to enlarged cyanogen pool, in addition to

direct lung/eye damage.

It must be stated clearly and unambiguously at the very beginning that the

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) which is the main protagonist of 'cyano

gen pool' theory does except the fact that lungs have been damaged by MIC gas and

a proportion of the morbidity may be due to that. It is, in fact, therefore the pro

ponent of mixed pathology, but for the sake of discussion and convenience, it is

called the protagonist of'cyanogen pool'theory. Supporters of pulmonary theory

include a dominant faction in Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal and has strong

support in the health department of MP Government. They are adamantly refusing

to accept any other theory, but their own theory. Naturally they are totally opposed

to cyanogen polo theory.

3.1 Pulmonary Theory

According to this theory, isocyanates, of which MIC is one member, are

6

toxic, irritant gases that directly damage the tissues they come in contact with-lungs

and corneas of eyes. The acute and long lasting pathological effects therefore are

to be seen only in lungs and eyes, and the effects of hypoxia secondary to lung

damage.

A small proportion of (about 5-10%) persons exposed to these substances

also develop sensitization (2,5).

The effects of isocyanates even in high doses on the gastrointestinal tract is

minimal (4).

It can induce blindness or visual impairment depending on the degree and

location of scarring (2,3).

Among the isocyanates toluene di-isocyanate (TDI) has been shown to

produce Central Nervous System (CNS) damage, manifested as loss of memory,

diminished mental capacity, persistent headache, personality changes, irritability,

depression etc (6)

But any such effect by MIC on CNS has been dismissed as

anecdotal "because MIC is such a severe primary irritant it would be apt to produce

such a severe degree of irritation that death would occur before sufficient absorption

of the compound could occur to produce systemic effects" (6).

This brings us to the central point of the theory, which is to explain why

MIC exoosure must produce damage to only lungs and corneas excluding all other

organ systems. Wny for instance MIC, an isocyanate, cannot have long lasting

CNS effects whereas another isocyanate, TDI, can have long lasting effect on brain

function?

Among the three isocyanates used in industry MIC is much more reactive

than the other two e.g. TDI and MDI (Methyl Di-isocyanate). It has been argued

that 'MIC is so readily decomposed by water, the chances are "very very remote"

that this iso-cvanate could enter the blood stream, be whisked to internal organs

and produce damage there, by reacting with target proteins'. It is further argued that

'for the same reason MIC lacks the hardiness to be a carcinogen. Molecules of the

compound would have to penetrate the cell wall and reach the DNA to do their ge

netic dirty work. It is virtually unthinkable that molecules of MIC could survive

such a cellular journey' (2,9).

This is the point : the high reactivity of MIC molecule renders it nonspe

cific and therefore it is bound to damage only those organs which come into

direct contact with it — lungs, eyes and skn. The skin may however escape because

MIC fumes may not penetrate the skin (3). The logical corollary of it is that long

term problems in survivors can be due to extensive lung damage and corneal damage

only.

Mr. W. Anderson, Chairman of Union Carbide Corporation, U. S. felt so

confident that in a letter of 3rd January 1985 (exactly one month after the disaster)

he wrote to an activist group which is monitoring the Bhopal Disaster to say that

'those injured by Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) are rapidly recovering and display little

lasting effects

for example, no case of blindness' (11).

The pulmonary theory therefore, must reject any other explanation for the

presence of wide ranging symptoms in the community and also the treatment based

on alternative explanations.

7

For the same reason some U. S. Scientists have characterised such

reports of Cyanide Poisoning of the exposed population 'highly questionable'

and 'probably spurious'. They have further argued that there is no known

metabolic pathway that converts isocyanate into cyanide (2).

The clash of theories extends to the whole range of health problems in

Bhopal.

i

Thus according to the ‘pulmonary theory' the large number of deaths in the

early hours of the morning of 3rd December 1984 were due to carbon monoxide

poisoning and to others the deaths were due to cyanide poisoning. We have no

definite information regarding the nature and quantity of dangerous gases that were

□resent in the atmosphere after the massive gas leak. However it is known that the

thermal decomposition of methyl Isocyanate can lead to the oroduction of a variety

of toxic substances including Carbon monoxide (CO) and Hydrogen Cyanide (4).

Tne temperature of toxic fumes gushing out of the tank was at least 1 20 degrees

centigrade (12).

An investigation was undartaken by the ICMR at a very early stage to sort

out this controversy. Particular attention was paid to find out clear evidence of

carbon monoxide and/or cyanide. A large number of control blood samoles and

also samples of blood already preserved in the deep freeze in the Medico Legal

Institute and fresh samples from cases who subsequently died were examined for

evidence of carbon monoxide poisoning (carboxyhaemoglobin) or cyanide poisoning

(cyanomethemoglobin) by spectrophotometric analysis (14). In none of the samples

was there evidence of either.

In contrast to this, a study of 113 MIC affected people who themselves

reported to K.E.M. Hospital, Bombay showed carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb) at a

concentration of more than 2% in 93% of cases. (The normal levels of COHb in

blood are 0.5 - 0.8 %. In smokers the levels could be as high as 1 5%, the average

being biing 5%) (13). This sample however is not a representative sample and the

control is lacking. Moreover aop/sex structure and smoking status are not given

(8). Bes;des, the effects of COHb levels less then 5% are controversial. COHb

levels of 20%, decrease tissue oxygenation and affect performance (10).

3.2

■ .

Enlarged Cyanogen Pool Theory

v

One of the most important developments of the complex findings among

Bhopal disaster victims has been the evidence favouring what may be termed an

'Enlarged Cyanogen Pool' theory. Professor H. Chandra of Medico Legal Institute

of Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal noticed in the early hours of 3rd December when

the first autopsies were being performed that even the venous blood of dead bodies

was cherry red in colour (so called arterialization of venous blood). All the internal

organs, lungs, intestines, kidneys, brain, muscles, etc. were bright red in colour.

This led him to suspect that victims could have succumbed to cyanide poisoning

(14,15).

A visiting German clinical toxicologist Dr. Max Daunderer is reported to

have detected cyanide in the affected patients (14,15,1 7) Unfortunately his findings

could not be repeated because of technical and methodological problems (14,15).

ICMR set out to 'identify the presence of either the original products'. The objec

tive was to obtain a better understanding of the probable detoxification mechanisms

which would help in the prompt use of an antidote to remove toxic substance still

circulating in the body (14).

8

As has been pointed out in 3.1 above, attempts to establish the presence

of either carboxyhaemoglobin or cyanomethemoglobin in the blood failed. However

all the samples of all victims showed twin bands of oxyhaemoglobin( 14) which is

an indication of a change in the nature of the haemoglobin molecule.

Special note must be taken here that from as early as the first week of the'

disaster, the ICMR approach to the problem pointedly ignored the theoretical notion

of the MIC molecule being too reactive to reach the blood stream and causing

damage to the internal organs.

Following a rapid study of available literature by Dr. Sriramachari it was

felt that the mechanisms of conjugation of isocyanate should be investigated

vigorously. The equivocal results in the increase of blood urea in fresh autopsy

tissue samples as well as qualitative reports of the presence of cyanide in tissue led

to the hypothesis that either due to inhalation of hydrogen cyanide from the conta

minant or cyanide radicals released by the breakdown of MIC within the body, there

was every likelihood of either acute cyanide or chronic cyanide poison operating

(14). This idea was reinforced by literature scan where in there is a reference to

the cyanide pool and its major excretory pathway through urinary thio

cyanate (14)

5 CYANOGEN

POOL

Major palb

CN“

Minor

pefh.

minor

2- iminoihiazolidine4- carboxylic acid. .

HC bJ

in expired air

CNS“ -

u

C M" poo I

Excretion.

Cyawocoba la win.

v

metabolism of

one carbon

compounds.

HCNO

HCOOM

CO2

some excreted

in urine.

L

9

As shown in the diagram above, there is a cyanogen pool in the body

which normally generates extremely small amounts of cyanide radicals in the course

of normal metabolic processes of the body. These cyanide radicals are easily

removed from the body by a process of detoxification which converts the cyanide

radicals into relatively harmless thiocyanates which are excreted as urinary thiocya

nates. This detoxification process is controlled by the enzyme called rhodanase in

the liver.

I

The process of detoxification by the rhodanase system can be accelerated

bv sodium thiosulfate if given in large amounts- This provides the rationale for

injection of sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of cyanide poisoning.

Also the amount of urinary thiocyanate excreted in the urine following

injection sodium thiosulfate gives an indirect clue of the size of cyanogen

pool in the body

And this provides the rationale for sodium thiosulfate as

an epidemiological tool of investigation of the hypothesis of 'enlarged

cyanogen pool' in the MIC exposed population of Bhopal to which we will

return in the Chapter 6.

p

} I

This pool of cyanogen is proposed to have been enlarged in the MIC

exposed population of Bhopal. According to the theory small quantities of cyanide,

but much larger than that which would be normally produced in the body, is con

tinuously contributed to the cyanogen pool of the gas victims from MIC molecules

which are attached to alia chains of haemoglobin molecules - a process that is called

carbamylation of haemoglobin. Cyanide blocks the activity of a large number of

enzymes but the most important from the point of view of its effects is the enzyme

called cytochrome oxidase in all toe cells w lich controls the oxygen utilisation of

theceils. This leads to under-utilisation or non-utilisation of oxygen at the cellular

level producing chronic hypoxia which is responsible for the whole range of

symptoms. At the same time carbon dioxide transport is also reduced. The study of

gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood may provide clues to disturbance

of gas utilisation and transport at the cellular level. The ICMR continued to pursue

its inquiry further to explore the idea of the cyanogen pool and its major excretory

pathway through urinary thiocyanate.

It decided to undertake a double blind clinical trial to find out the useful

ness of sodium thiosulfate injections on 30 patients. 10 out of 19 who were given

sodium thiosulfate showed marked clinical improvement and had an 8 to 10 fold

increase in the excretion of urinary thiocyante, whereas 1 out of 15 who got

injection glucose showed such increase (14). The full details of this most crucial

trial have not been made public and the findings have been contested by those who

uphold the 'pulmonary theory'. Tnis controversy has been further discussed in

Chapter 6. The opoonents of 'cyanogen pool' theory claim to have conducted their

own study with sodium thiosulfate and the results were according to them, dis

couraging. However it is known that it was not a double blind clinical trial like

ICMR's and that full details of this trial have not been made public either !

Alongside this investigation, studies of arterial and venous blood oxygen

and carbon dioxide levels were undertaken. This was to understand the state of

oxygen utilisation al tissue level and carbondioxide removal from the tissues.

Following are the salient findings of the investigation.

a) Level of oxygen in arterial blood was lower than normal (14)

b) Similarly level of carbon dioxide in the arterial

than normal (14)

10

I

blood was also lower

c) Inspite of raised haemoglobin levels its oxygen carrying capacity was

lowered. There is a probability of some compensatory mechanism,

operating such as indicated by elevated levels of 2-3 Diphosphoglycerate

(2-3 DPG) in the blood which is one of the mechanisms to improve the

oxygen utilisation by the tissues (14)

d) Following the treatment with sodium thiosulfate the carbon dioxide

level in venous blood increased, with improved clinical condition. This

preliminary observation tends to indicate that following administration

of sodium thiosulfate, patients appear to better utilise the oxygen. The

higher levels of carbon dioxide in the venous blood probably means that

venous carbon dioxide is being carried in solution. This could be du?

to some alteration in the haemoglobin molecule, possibly by mechanisms

such as carbamylation of end-terminal amino groups (14) .

All these findings such as increased haemoglobin concentration, twin

bands of oxyhaemoglobin, more than doubled normal values of 2-3 DPG in the blood

and clinical improvement, augmented output of urinary thiocyanate and rise in carbon

dioxide level in venous blood following sodium thiosulfate injections are unexpected

but highly suggestive.

These findings strongly suggested that tissue utilisation of oxygen in gas

victims is problematic. This is not a simple function of reduced diffusion —perfu

sion ratio leading to anoxia as one would expect in exclusive pulmonary damage.

The pathology is not only in the lungs, probably it is at a cellular level in

all the vital organs. Logically speaking it is not imoerative for the theory to chase

only MIC molecule in the cellular processes. There may be other molecules deri

ved from MIC or other toxic gases which contribute to the cyanogen pool. The

cyanogen pool theory may stand or fall the critical tests but these findings if true

are in need of explanation.

11

I Z’P /

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

47/1, (First Floor) 3c. .Marks Soad

BANGAtO3£ - 5u0 001

CHAPTER 4

MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1

Sample Population

I

Two bastis (slum areas) were selected for the study: ( i ) JP Nagar. which

was the worst affected, is situated right in front of the U tion Cirbide factory;

(ii) Anna Nagar, which is about 1 0 km. south of the factory was selected as a control

(see mao)

It is important to clarify here that no area in Bnopal which has similar

bastis was unexposed to MIC at the time of the disaster and hence Anna Nagar was

also exposed. However, it was one of the least affected areas. In the absence of

any available information regarding the quantum of gas exposure of various com

munities differences in postexposure mortality can be taken as a criterion of difference

in gas exposure. Our assumption, therefore, in selecting Anna Nagar as the least

affected was based on the available mortality rates from the Department of Infor

mation and Publicity, Government of Madhya Pradesh - JP Naoar 2 34% and Anna

Nagar 0 32%

This assumption was further corroborated by our study-finding of a

difference in mortality between JP Nagar (36.6/1000) and Anna Nagar (7.9/1000),

in the three month p°riod between MIC gas exposure and our study. Another

significant finding which justified this selection of samples was the fact that 45

persons (30%) out of our sample in JP Nagar had been hospitalised after the gas

exposure whereas the figure for Anna Nagar was one person (J.72%), a clear indi

cation of the differential exposure.

L

1

Both these bastis were more or less comparable with respect to housing,

sanitation and economic characteristics though there were some socio-cultural

differences among the two areas, in that the inhabitants of Anna Nagar were predo

minantly migrant labour from the south who were, however, resident in Bhopal for

many years.

We decided on a sample size of about 180 persons of both sexes of more

than 10 years age for each basti (This was based on the assumotion that

significant morbidity would be atleast 15% in JP Nagar and 5% in Anna Nagar.

We wished to have a 90% chance of finding this difference with significance level

of 5% in a two tailed tes* i. e. 2a = 5% and B = 90%). It needs to be emphasised here

that the assumptions on which the sample size was computed, are quite stringent. For

our ouroose sample siz^ is more than adequate. Since random selection of indivi

dual persons was noi possible, we decided to select at random 60 families from each

basti to yield the desired number of persons. Random selection of families in both

bastis was fortunately possible because the ICMR had already provided a numbar

plate for each household. This provided the much needed sampling frame from

which random sampling of families was done with the help of random number tables.

Children below 10 years were excluded from our sample because of the

fact that their reporting of symptoms and pulmonary function tests would be

unreliable.

4.2 Methods

As will be noted by the readers, history-taking has been our most important

method of study. Methodological issues arising in respect of this method have been

discussed in Chapter 2—'Objectives of the study* 'and below in the section of

'Morbidity Analysis*. The following were undertaken during the study.

12

4.2.1 History-taking and physical examination of each individual

A detailed proforma was designed for the study which was to be administred to each eligible member of the selected families (Appendixl). It included

the following sections.

Section I : This included the following information about each household:

family composition; deaths or missing members since the gas leak; occupation;

income; history of smoking or chronic respiratory diseases (TB, asthma and chronic

bronchitis) of each member. Details of loans taken by the family and compensation

received were also elicited.

Section II : This was to be filled for each individual in the household

included in the sample. It included details of occupation and income; change in

income due to i11n ess/disabiI ity following gas leak; certain details about exposure

and safety measures attempted; whether hospitalised after exposure and history of

smoking and chronic respiratory illnesses (TB, asthma and chronic bronchitis).

Section III : Every individual included in the sample was subjected to a

systematic enquiry of 26 symptoms. The patients own description of these

symptoms were listened to avoiding much direct questioning.

A general physical examination was also done including (i) height and

weight (ii) and (iii) pulse and respiratory rates for full one minute in resting posi

tion after lapse of considerable time to ensure relaxation (iv) eye examination

including cornea, lens, pupillary reflexes, distant vision and near vision (v) general

signs like oedema, jaundice, cyanosis (vi) examination of skin; (vi.) respiratory

system; (viii) cardiovascular system; (ix) central nervous system; (x) alimentary

system.

The parameters for each system are shown in Appendix I.

Section IV : This was for each woman belonging to the reproductive age

group included in the sample. It included menstrual history; history of gynaecolo

gical complaints before and after gas leak; pregnancy and its outcome; if a nursing

mother then details of lactation before and after exposure.

4 2. 2 Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs) which included Forced Expiratory

Volume in 1st second (FEVI) and Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) for each individual.

PFTs were recorded by Morgan's electronic spirometer set as BTPS. Three readings

were recorded and the highest reading was taken for analysis.

For the interpretation of PFTs, height of each individual was measured by a

straight aluminium rod on which a metal measuring tape was fixed. Weight was

measured by standardised bathroom scales. The sample size of PFTs was further

extended by additional observations on other families selected at random in both

bastis. PFTs were performed by a doctor who had adequate experience of using the

spirometer under field conditions.

4.2.3 Haemoglobin estimation using Sahli's haemoglobinometer was done on a

random sample of the two bastis.

4.2.3

An enquiry into the people's perceptions of the existing services was done

13

by administering a questionnaire (section vi) to one member of each family jn.

eluded in the sample. These included questions recording availability and accessi

bility of services, quality of service, type of treatment given, attitude of examining

doctor, cost of treatment, and nature of doctor-patient communication.

4.3

Building rapport with the people

The mfc team arrived in Bhopal to undertake the study in the third week

of March 1985 (15th - 25th) . three and a half months after the tragedy. Numerous

teams of investigators and relief workers both governmental and non-governmental

had visited the selected bastis, made enquiries, offered or promised relief, raised

expectations about compensation and assistance.

For the mfc team to ensure, therefore, that it would still be able to get

reliable, authentic and relevant information it was necessary to counter this pre*

conditioning of the basti dwellers and establish a meaningful rapport, free of sus

picion, of false expectations and a sense of dependency. We therefore, employed the

following strategy :

(a) Two days before the study, while selecting the samples the Coordinator

and a team member visited the selected bastis and had informal discussions with

some of the people explaining the objective of our study and the possible outcome;

►

(b) A hand-out prepared in Hindi was freely distributed among the basti

dwellers. It clarified the role of the mfc, explained about the need for a sample

and mentioned the possible follow up action. It specifically clarified that we were

not providers of service but were facilitating a more relevant plan of serivces

(Appendix II).

(c) During the actual survey, time was $.

spent with each family answering

their numerous enquiries and listening patiently to their stories.. C

Occasionally

when non-sample individuals/families approached the team members they were also

listened to and occasionally given an examination;

(d) A summary of findings was made and handed over to each person in

the sample; because we believed that it was a right of the people to get a record of

.the findings.

(e) In all our contacts with the people, it was very clearly stated that

though the team was a medical one, it was not going to provide any treatment nor

be involved with compensation claims. However, wherever it was necessary a

prescription was given though this was rather occasional;

I ’

(f) A commitment was also made that the salient findings of the study and

our recommendations would be made available to the people of the affected bastis to

help them demand their rights to meaningful health services.

This methodology of informal, frank and participatory communication had

its own rich dividends. The basti dwellers in both Anna Nagar and JP Nagar wel

comed us into their homes warmly and took us into confidence. They appreciated

our 'listening' attitude and this generated a lot of cooperation and support to our

efforts. A major point of frustration for many of them was that though they had

received treatment from government and other services, they had felt that the doctors

were not taking them seriously and were summary in their approach. This affected

the credibility of the existing services.

14

Our decision to concentrate very consciously on rapport building ensured

that there was not one refusal among those who were present at the time of our

visits. Moreover although several health surveys are supposed to have been done

in these bastis, we found that in hardly any family, we had selected in our sample

was there any health survey done. There was, therefore, no question of families

being flooded witn same types of questions and getting conditioned, consciously or

unconsciously, to answer in a particular way or pattern.

4.4

Plan of Analysis

Ths plan of analysis of the data collected by us was as follows:

(i) All parameters in history, symptomatology and findings of clinical

examination and lung function tests have been quantified and the

percentage in each of the two bastis have been compared;

(ii) Relevant statistical tests have been applied to determine whether the

differences, if any, are statistically significant;

(iii) Both the theories in the current medical controversy i.e. the pulmonary

fibrosis theory and the 'cyanogen pool' theory have been kept in mindz

consciously during the analysis to raise critical questions about both

these theories from our findings;

(iv) Basically the important problem areas have been identified. There has

been no attempt to group symptoms into specific diagnostic categories

and both signs and symptoms have been taken into account in the

analysis.

He is unwise who acts without investigation-

—Charaka Samhita

15

CHAPTER 5

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

I

5.1 Non-responders: some observations

ii

In JP Nagar in the 60 families selected there were 203 eligible persons

whereas in Anna Nagar, the corresponding figure was 163.

In JP Nagar, 60 out of 208 individuals could not be interviewed and

examined, giving a non-response rate of 29%. The corresponding figure for Anna

Nagar is 15% (25 out of 163).

■

Several home visits were made by the survey teams in both

reduce non-response rates.

the bastis to

We feel that the given non-response rate in JP Nagar and Anna Nagar

will not have a significant effect in the differences in rates of serious morbidities.

Because, first, the age and sex structure of both responders and non-responders in

both bastis is more or less similar. Secondly there was not one case where a

person was at home but refused to cooperate. Had there been many such refusals

amongst non-responders "the results would have been biased in unpredictable

manner".

i

In JP Nagar majority of non-responders (about 60%) were out of town

mainly for the reasons of treatment or fear of another gas leak. Twenty five per cent

of them were out for work. At Anna Nagar about 50% were out of town for the

purpose of social visits whereas 25% were out for work.

There have been large epidemiological studies where non-responders have

been as large as 30%. This did not necessarily vitiate its results (22).

In the case of non-responders, if we are blind with respect to both exposure

and outcome then the difficulty increases (22). In JP Nagar we have no information

about the outcome in non-responders but we have recorded information that about

50% of them (28/60) were exposed to gas on 3rd December, in the remaining half

many may have been exposed but we have failed to record definite information. No

one among the non-responders in Anna Nagar was heavily exposed to MlC gas.

Thus with regard to exposure status we are not completely blind.

I

If we make an assumption (though it is unlikely in view of available

history of exposure in at least 50% of non-responders) that all the non-responders

in JP Nager and Anna Nagar were normal, this will have an effect of narrowing

down the differences in rates of morbidities between the two bastis. Even then the

difference in rates of all serious symptoms between JP Nagar and Anna Nagar

except for dry cough, lacrimation, breathlessness at rest and impotence remain

statistically highly significant.

‘

•

The reduction In sample size due to non-response rate has also not effected

the outcome at all, because much greater differences in the rates of morbidity than

had been expected (or assumed) between the two communities meant that our pur

pose of finding significant differences (if there was any) would have been served

well even by much smaller size of the sample than the ones we studied.

16

5. 2

Comparison of samples of J P Nagar and Anna Nagar

Tables 1-A and 1-B show that both these sample populations are compara

ble with reference to age, sex structure, history of smoking habits and chronic disea

ses. Table 1-C shows that occupations’and income levels are also comparable

though the J P Nagar population was probably socio-economically better off than

the Anna Nagar population. This income difference cannot however affect the

observed differences in morbidities between the two samples. Table 2 shows that

body surface areas (M2) calculated from height and weight records are also compa

rable in the two samples. This is particularly relevant in the context of pulmonary

function tests.

Comparisons of some of the important characteristics of J P Nagar and

Anna Nagar populations (study/control populations)

Table 1 A

Age-Sex Structure

Age

J P Nagar

%

n = 148

Sex

Anna Nagar

%

n = 138

11-15 years

M

F

8.10

9.46

10.14

4.35

16-45 years

M

F

35.81

33.78

34.78

31.88

M

F

6.63

10.14

6.75

8.70

46 +

Table 1 B

History of smoking and chronic diseases

Smoking (a)

+

J P Nagar

Anna Nagar

%(n= 148)

% (n= 138)

77.24

25.0

75.0

9 58

90.41

89.62

22.75

Chronic

diseases (b)

10.37

(a) a smoker is one who has smoked at least one cigarette per day for at least one

year in a life time.

(b) chronic diseases specifically included asthma, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis

and others.

17

Table 1 C

Occupation and income levels

J P Nagar

Anna Nagar

%

n = 148

%

n = 138

Unskilled

18.91

27.73

Skilled

7.43

8.73

Self-employed

13.51

15.32

Service

14.18

10.21

House work

29.72

24.08

Others

16.21

13.36

Occupation

Per capita income per

month before gas exposure

Less than Rs. 50.00

4.68

4.58

Rs. 51-75

10.93

22.93

Rs. 76-100

16.40

21.10

Rs. 101-125

14.84

13.76

Rs. 126 and above

53.12

37.61

5.3 Socio-economic profile in the bastis

5.3.1 Occupational structure

The residents of both JP Nagar and Anna Nagar were long term residents of

these bastis. Residents of JP Nagar were predominantly Muslims and Harijans with

a wide range of occupations that included daily wage labour, construction workers,

beedi rollers, cobblers, railway and factory employees, self employed artisans and.

others. Almost 1 /5th (19%) of the working population in JP Nagar was unskilled.

18

Residents of. Anna Nagar were, predominantly.Tamila and-Maharashtrians

and had a similar range of occupatian apart from a large number of potters. The

percentage of unskilled workers was 28%.

The percentage of skilled persons in both samples was less than 10%. The

category 'others' in the table is mainly represented by students.

5.3.2

Income levels and change in income since gas exposure

The income levels of both the samples are shown in Table 1-C. JP Nagar

residents are generally of higher income levels as compared to Anna Nagar, e.g. before

the disaster 68% of the families in JP Nagar had an income more than Rs. 100.00/

capita/month whereas the corresponding figure in Anna Nagar was 51%.

After the disaster, in JP Nagar 65% (42 out of 64) of the working persons

experienced a drop in income ranging from 20% to 100% with a median of 50%

drop in income (Fig. 1)

In contrast, in Anna Nagar only 9% (6 out of 64) reported a drop in income

after the disaster. The extent of the drop in income was in the range of 20% to 55%

(Fig.1).

Two individuals in JP Nagar showed an increased income after the gas

disaster being exceptions rather than the rule.

(a) one person who was a loco-daily wage earner and got a job in the

loco-loading department after the event with an increased scale of pay;

(b) one woman (housewife) who started brick loading after the'disaster as her

husband was not able to work after the disaster. Since our focus was on

individual income rather than family income such an instance of increase

is misleading. In actual fact with the husband being unable to work the

family income had not been increased.

5.3.3

Compensation received and loans taken

During the acute phase of the crisis the only source of inconTe if at all was •

the compensation received by families (only those who had deaths in the family)

and loans taken from money lenders and others locally.

Some of our findings were:

In J P Nagar

Compensation of Rs.10,000.00 was given to 8 persons (out of 26 reported

deaths). One non-respondent family had 5 deaths and 1 child survivor of 8 years in

an orphanage. We could not elicit compensation details in this case.

Compensation was also given to other families who did not have a death.

In our sample 2 persons got below Rs. 500.00; 3 persons between Rs. 500-1000,

4 persons between Rs.1000-2000 and 1 person between Rs. 2000-3000.

13

F

I

o

o

CN

o

co

O

O

in

o

co

o

6

co

6

o

o

CD

6

co

o

o

°?

o

O

OOfrl0081"

u

VI

□

0CZL-.

V)

O

CL

X

®

w

Q

D)

oooi-

co

.2

®

’E

□

E

E

o

o

Q.

Ui

®

CD

Q.

□

o

o

<

z

<

z

z

<

ooz.-:

oo9-: :

oo9-:

00fr-

JC

X)

<

O

s.

c 006-:

o

<5 008a

♦-

Ct

£0014o

E

E

o

o

c

008003-

v>

75

5

001-

’■5

l

ift'

c

OOVL-

o

008

®

E

I •

. I

o

u

c

c

©

ex

c

x:

o

©

c

0011-

a> ooo t-*

a

c

o 006w

©

CL

a

z

CL

Q.

00

'u>

®

0

CL

oo9-: .

a.

□

£

5

a>

E

o

o

c

£

<

<

K_

©

®

Ct

008-

ex

c

u

u.

11

5 0031-*

«

009-•

oov008- ♦

003-•

* « * ♦

00 L-

6

OOO

CN

CO

6

in

o

o

% Uj 0UJO3UI Ul eSB9J08Q

i

Twenty families in which there were no deaths and to whom no compen

sation was given had to take loans for medical treatment and for the migration during

'operation faith'. Many of them put their ornaments, vessels etc. on mortgage.

In Anna Nagar

Seventeen families who did not have a death in the family had to take loans.

Most of them specifically mentioned that this was during 'operation faith' when they

went outside Bhopal for a while.

5.4 Morbidity Analysis

5.4.1 General comments

Before presenting the analysis of morbidity, two issues must be sorted out.

One, it must be stressed again that there is no population which matches

JP Nagar socio-economically or in respect to housing and sanitation which

was not exposed to the toxic gases on 3rd December, 1984. A control population

selected like Anna Nagar is not strictly speaking a 'non-exposed' population as it

should be but serves as a control population by virtue of being minimally exposed

in comparison to JP Nagar. This also implies that even in our control pooulation

one would expect to observe some of the disabilities or debilitating morbidities in a

higher proportion of the population than would be the case in an unexposed control

area. Actually this is what we did observe and the Anna Nagar sample had dafinitely a larger number of serious symptoms in a sizeable proportion of persons stu

died (Tables 3-A to 3-C)

This is something which is quite unexpected and in fact narrows down the

differences in rates of symptoms observed between the two populations. The health

impact of the toxic gases on the exposed population is, therefore, much greater than

what our study reveals.

Seen in this background alone can one appreciate the devastating impact

on the health of highly exposed populations. Because in spite of the dampening

effect on the differences in rates explained earlier, the rates of many serious symp

toms (indicating widespread underlying damage to the physical and mental health of

the victims of the gas disaster) in JP Nagar are higher than Anna Nagar with an

extremely high level of significance (Table-3-A and 3-B).

Two, the dependence of the study on symptoms may be felt to be proble

matic by many, since it is 'subjective' and therefore less dependable. As discussed

in Chapter 2 the problem situation as it was unfolding was such that one had few clues

as to the pathophysiological disturbances taking place in the bodies of the gas victims.

The only loud and clear clue was the people complaining of symptoms. What

biochemical pathological parameters could be included in the study to enhance the

objectivity of the study? None, except one as we have tried to argue above.

We acknowledge freely the problems of relyingion symptoms reported by

the individuals. We would, however, like to draw attention to the fact that even

in more understood problem situations like epidemiological studies of chronic bronc

hitis, emphysema, angina pectoris also, the most reliable tool of epidemiological

study is recognised to be the questionnaire. Of course, these tools as developed

by Medical Research Council (U.K.) and American Thoracic Society (U.S.A.) have

been standardised to varying extents. Similarly, the epidemiological too! in the

21

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

47/1. (First Floors, Marks noad

BANGAlO^- •560 001

study of psychiatric disorders is also a questionnaire. It is not necessarily true that

since symptoms are reported by the individuals, they are subjective and hence less

reliable than biochemical measurements. The point is not whether we are using

so called subjective or objective measurements, the point is whether we are employ

ing appropriate methods and tools to answer clearly the critical questions we are

raising in a given problem situation.

■

True, an important limitation of this study is non-standardization of the

questionnaire i.e. ability of the questions to elicit the same answers on two or more

occasions (reliability) and the ability of the questions to measure what was intended

(validity). Due to limitations of time this was not possible.

r

..

However the varied symptomatology presented by the subjects of the study

were not mentioned by them casually but given in graphic detail; words and' exam

ples used by the patients while describing their symptoms clearly showed the gra

vity of the symptom as well as its effect on the person's day to day work. The

different manner in which the symptom was described also showed that the person

was informing us of a problem based on his/her own experience and not just vague

hearsay expressions. This is particularly important since in the absence of signs in

the same proportion as symptoms, doctors attending on these people in busy

government clinics were often passing off the symptoms reported, as compensation

'malingering' or'not of clinical significance'. We have every reason to believe that

these symptoms were real expressions of physical and mental ill health and many

should be accorded the same significance as the use of patterns of cough with or

without expectoration in the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis or the use of anginal

history in the diagnosis of Ischaemic Heart Disease.

The commonest symptom reported was breathlessness on usual exertion and

the specific descriptions recorded were: (1) while excessive talking; (2) on brisk,

walking; (3) doing house-hold work in a hurry; (4) fetching water and firewood;

(5) cannot go till the market; (6) little walking - say 100 yards; (7) while coughing;

(8) while riding a bicycle etc.

5.4,2 Symptomatology and signs - a comparison

Tables 3-A - 3-C show the difference in rates of the 26 symptoms that had

been enquired into in both the sample populations. It must be emphasised that a

symptom was recorded as positive only if it was present at the time of the study.

Five symptoms were not significantly different. These were blood in sputum, fever,

jaundice, blood in vomit, stool or malena and vomiting.

Six symptoms were significantly different. These were dry cough, breath

lessness at rest, lacrimation, skin problems, bleeding tendency and impotence.

Fifteen symptoms were highly significantly different. These were cough

with expectoration, breathlessness on usual exertion, chest pain/tightness, blurred

vision/photophobia, headache, weakness in extremities, muscleache, fatigue, loss of

memory, tingling/numbness, nausea, abdominal pain, flatulence and anxiety/depression. Moreover critical symptoms like breathlessness on usual exertion, lacri

mation, pain/tightness in chest, blurred vision, weakness in extremities, fatigue,

loss of memory, tingling/numbness, anorexia, nausea, flatulence and anxiety/depression were not reported in a monosyllable 'yes' but described in such graphic

detail that their presence could not be doubted.

22

5.4,3

Clustering

It was obvious from the study findings that most of the persons in JP Nagar

had more than one symptom present. To further study the pattern of clustering of

symptoms, we grouped the symptoms according to the system they naturally belong

to. Some overlap in such grouping is inevitable but it does reveal the overall pattern

e.g. an important symptom like breathlessness on usual exertion which is reported

with highest frequency does not squarely belong to one system like cardiovascular

or respiratory system alone. Both these systemscan with equal legitimacy lay claim

to this most frequent and crucial symptom and this is particularly important

since we are examining critically two dominant medical theories in this study-'cyanogen pool' theory and 'pulmonary theory/

All the symptoms were grouped together system wise as follows :

(a) Pulmonary system (P)

The grouping of symptoms suggesting diffuse pulmonary fibrosis is based

on Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 10th edition, 1983 (Chapter

280, P.1567).

They include breathlassness at rest and on accustomed

exertion, dry cough and cough with expectoration, weakness in extremities

and pain/tightness in the chest. To be included in this group the combi

nation of symptoms had to have cough with or without expectoration and

dyspnoea at rest or usual exertion.

(b) Gastro-intestinal system (Gl)

They included anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and flatulence.

Table 2

Comparison between body surface area ( M2) in JP Nagar and Anna Nagar

according to age-sex (figures in brackets show S .D)

Body surface area

(mean)

in Sq M2

n= 136

n = 137

1.23

(0.14)

1.22

(0.19)

F

1.22

(0.12)

1.15

(0.13)

M

1.49

(0.09)

1.51

(0.12)

F

1.37

(0.11)

1.35

(0.12)

M

1.50

(0.14)

1.53

(0.09)

F

• 1.37

(0.09)

1.41

(0.22)

M

1.35

(0.04)

1.38

(0.15)

F

1.32

(0.06)

1.28

(0.05)

15-45 years

61 4-years

Anna Nagar

M

11-15 years

45-60 years

J P Nagar

Note: The differences in mean BSA's were tested by't* test — all

were statistically non-significant fNS)

23

the

differences

Table : 3 A

Comparison of Symptoms reported by individuals in J.P. Nagar and Anna

Nagar. (Expressed in percentage. Numbers of cases are shown in brackets.)

bl

No.

Symptoms

J.P. Nagar %

A. Nagar %

P. Value*

P

(a)

1.

Dry Cougn

27.70 (41)

14 49 (20)

2.

Cough with Expectoration

47.29 (70)

23.91 (33)

< 0.001

3.

Breathlessness at rest

10.13 (15)

2.89

(04)

< 0.025

4.

breathlessness on

usual exertion

87.16 (I29)

35 50 (49)

< < 0.001

5.

Chest pain/tightness

50.0

(74)

26.08 (36)

< < 0.001

6.

Weakness in Extremities

65.54 (97)

36’95 (51)

< < 0.001

7.

Fatigue

81.08 (120)

39.85 (55)

< < 0.001

8.

Anorexia

66.2.1 (98)

28 26 (39)

< < 0.001

9.

Nausea

58.10 (86)

16.66 (23)

< < 0.001

10.

Abdominal pain

53.37 (79)

25.39 (35)

< < 0.001

11.

Flatulence

68.91

(102)

25.36 (35)

< < 0.001

12.

Lacrimation

58.78 (87)

42.62 (58)

<< 0. 01

13.

Blurred vision/photophobia 77.02 (141)

33.10 (53)

< < 0.001

14.

Loss of memory for

recent events

45.27 (67)

11.59 (16)

< < 0.001

15.

Tingling/numbness

5*1.72

20.28 (28)

< < 0.001

(81)

*(a) P Values were calculated by X2 method.

24

<

0.01

Table : 3 B

Comparison of Symptoms reported by individuals in J.P.Nagar and Anna

Nagar. (Expressed in percentage. Numbers of cases are shown in brackets.)

(Symptoms significantly different but not analysed further)

SI.

No.

Symptoms

J. P. Nagar %

A. Naga'%

P. Value

•(a)

1.

Skin problems

29.05 (43)

11.59 (16)

<

2.

Bleeding tendency

9.45 (14)

2.89 (04)

< 0 025

3.

Headache

66.89 (99)

42.02 (58)

< < 0.001

4.

Muscle ache

72.97 (103)

36.23 (50)

< < 0 001

5.

Impotence

8.10 (12)

0.72 (01)

< .05

6.

Anxiety/Depression

43.92 (65)

10.14 (14)

< < 0.001

0 01

Table : 3 C

Comparison of Symptoms reported by individuals in J P Nagar and Anna

Nagar

(Expressed in percentage. Numbers of cases are sho wn in brackets.)

(Symptoms - Non-significant)

Si.

No.

Symptoms

J. P. Nagar %

A. Nagar %

P. value*

1.

Blood in Sputum

10.13 (15)

7.24 (10)

N.S.

2.

Fever

27.70 (4’1)

• 28.98 (40)

N.S.

3.

Jaundice

0 67 (01)

00

N.S.

4.

Blood in vomii/stcol/malena

12.16 (18)

10.14 (14)

N.S.

5.

Vomiting

11.48 (17)

5.79 (C8)

N.S.

“”2

*(a) P Values were calculated by X method.

25

(a)

r

(c) Eye Symptoms

They included blurring of vision and or lacrimation.

(d) Central Nervous System (CNS)

Disturbance or loss of memory and tingling and numbness.

The foliovying symptoms were not included in this classification: impotence,

anxiety/depression,’headache, muscleache, bleeding tendency, skin problems.

Table 3-D shows the incidence of the combination of these symptom complexes.

Some very interesting facts emerge.

As large as 63.5% (94/148) persons reported all the important symptoms.

Only 2.7% (4/148) have symptoms which are exclusively pulmonary.

Atleast

35.14% of persons do not have any pulmonary symptoms.

Table 3-E further explores the group of patients without pulmonary symptoms and

we found the following significant facts:

About 21% persons have Gl symptoms without pulmonary symptoms.

About 22% persons have eye symptoms without pulmonary symptoms.

I

About 15% personshave CNS symptoms without pulmonary symptoms.

i

In the last three categories symptoms of other systems may or may not

have been present.

An important further point of comparison between JP

Nagar and Anna

Nagar with reference to this grouping of svmotoms is that every person in JP

Nagar reported atleast one serious symptom but quite a few in Anna Nagar

did not report any serious symptom.

!

Table: 3 D

Symptoms

Symptom groups

■ 11

No /Total

%

P + G. I. + Eye + CNS

92/148

62.16

P (Pulmonary only)

4/148

2.7

P - NIL (ie G.I./CNS/Eye)

52/148

35.14

(For

. symptoms

included in

grouping

26

V

please

refer

4.4.3)

Table : 3 E

Symptom Complexes excluding Pulmonary System

Symptom Groups

No./Total

%

GJ. (with or without eye/CNS)

31/148

20.94

Eye (with or without GI/CNS)

32/148

21.62

CNS (with or without Gl/Eye)

23/148

15.54

Table : 4

Patterns of disturbance of vision in 10 — 45 yrs of population in J.P. Nagar

and A. Nagar (Figures in brackets indicate actual number )

J.P. Nagar %

Anna Nagar %

(D