Of Cholera and Post-Modern World

Item

- Title

- Of Cholera and Post-Modern World

- Creator

- Mohan Rao

- Date

- 1998

- extracted text

-

>52?

PERSPECTIVES

Of Cholera and Post-Modern World

Mohan Rao

An examination of the political and economic forces underlying

the recent epidemic of cholera in Latin America

reveals striking resemblances to the situation in which the

pandemics of cholera occurred in the 19th century. It draws

attention to the fact that not only does politics inform the

occurrence of disease, but the shape and content of health policy

and intervention as well.

The Cholera’s Coming

The cholera's coming - oh dear, oh dear,

The cholera’s coming - oh dear!

To prevent hunger’s call

A kind pest from Bengal

Has come to feed all

With the cholera, dear.

The people are starving - oh dear, oh dear.

The people are starving - oh dear!

If they don’t quickly hop

To the parish soup shop

They’ll go off with a pop

From the cholera, dear

The cholera’s a humbug - oh dear, oh dear,

The cholera’s a humbug - oh dear!

If you can but get fed

Have a blanket and bed

You may lay down your head

without any fear.

—A popular song of the 1830s in England.

THIS article, by way of a preliminary en

quiry, is divided into three pans. The first

briefly describes the conjuncture within

which arose the cholera pandemic currently

sweeping Latin America. The second harks

back to the 19th century to examine cholera

pandemics emanating from India and

threatening existing order in Europe. I end

with observations and speculation on the im

pact of what has been described as the post

modern world order on the health of the

poor in third world countries.

I

Cholera, a disease known from antiquity

(the word is derived from the Greek, ‘kolera’,

meaning diarrhoea) now shows its minatory

face over the US, at the apotheosis of her

power and glory. Cholera, that king of

dismay has always been a disease that stalked

the poor and haunted the rich. Now, where

did this awesome threat emanate from?

Peru, the land of the glorious Inca

civilisation.

To historians of disease Peru is of singular

interest. What baffled historians was how

this mightycivilisation succumbed so rapid

ly, so easily, so very meekly to the small band

of Spanish conquistadores lead by Pizarro.

i

i

I

i

I

t

Was it the superior technology of gun

powder? McNeill offers the explanation that

it was in fact disease, in this case small pox,

which scaled the fate of the Amerindian

civilisations. Unexposed to small pox, the

Indians were ravaged by the disease; the

Spaniards, in contrast, supremely immune,

seemed supematurally protected. While

small pox savaged rhe Incas, the conquistadores marched unharmed, unopposed, to

raid the capital, its. temples and treasures.

Thus was Peru ‘integrated’ into the world

market. The events in Peru recalled the

similar amazing conquest of the Aztec em

pire of Mexico and her millions by the

Spaniard Hernando Cortez with an army

numbering less than 600. Infectious disease

then has had a profound, if not decisive,

effect on the tide of history.

Al the heart of the Spanish Empire, Peru

was plundered by colonial rule. Her ‘tryst

with destiny’, when it arrived, was but a sad

one. Peru is today one of the poorest nations

of South America with a population of 20

million and an external debt of 25 million

dollars. A poor country with a primarily

peasant economy Peru could ‘naturally’ only

rely on export of primary products to build

her economy. The economy, equally natural

ly, was guided by the US since the Peruvian

ruling class was preoccupied with a lavish

life style and holidays in Florida. Other

events were natural consequences. A coun

try whose ruling class lives beyond its means

gets into debt. The iron laws of international

economics are unbending: they will not per• mil the prices of the primary commodities,

that Peru exports, to rise. The irresponsible

ruling class cannot tighten its bek; indeed

they cannot even control their own peasant

rebels. Security assistance from the US is

necessary and is forthcoming to quell those

.rebels. The niceties of parliamentary demo

cracy may have to be given short shrift for

some time.

______

This, too, is ‘natural’‘for does the eco

nomy not have to be put on rails? Produc

tivity must increase, exports must go up;

there should fre a cutting down on ‘wasteful’

social expenditures, particularly those

’ 1792

1

'

directed towards vulnerable populations; in

efficient public enterprises must be made ef

ficient, that is to say, almost axiomatically,

privatised. Thus runs the wisdom of the

package on structural adjustment enunciated

by the IMF-World Bank towards which Peru,

‘naturally’, turns for loans. As the country

was being further ‘integrated into the-world

market’, in August 1990 was implemented

the IMF-World Bank sponsored programme

described as ‘Fujishock’ or "the most severe

zform of ‘economic engineering’ ever

applied’’.

And Peru did adjust structurally, if pain

fully. The pain was not, of course, equally

apportioned—the IMF-World Bank prescrip

tions did not envision that for it would

involve unthinkable changes in patterns of

investment and consumption. The pain was

‘naturally’ distributed to the poor in their

over-crowded shanty towns, slums or barrios.

Structural adjustment has meant devasta

tion to the lives of the poor and indeed even

the salariat. Consequent to wage freeze and

an unprecedented price rise has occurred a

drastic squeeze on the purchasing power of

the people.’Unemployment and casualisation of wage labour has reached dismaying

heights. It is estimated that the real purchas

ing power declined by 85 per cent even as

the cost of bread increased by an incredible

1150 per cent. State support to health and

education has been phased out leading to

a collapse of health and educational institu

tions. Essential humanpowrr, of trained doc

tors and nurses, look flight to greener

pastures contributing io a further drain of

capital from Peru. Public hospitals, despite

inadequate staff and widespread lack of

drugs and equipment, have attempted to

‘recover costs’ through fee for services^ The

impoverished population cannot therefore

avail of medical care leading to a decline in

hospital attendance and admissions even as

morbidity levels increased; the rich, of

course, never dependent on public institu

tions have their private havens. Public health

activities such as water supply, nutrition and

sanitation, seldom an area of high priority,

have come to a grinding halt.

It is in this context of poverty, squalor,

hunger and misery that the disease of under

development flares up. It is not fortuitous,

therefore, that cholera should break out in

the barrios. Cholera was first reported in

several coastal cities of Peru almost

simultaneously.in January 1991..It spread

rapidly across the country.. crossing the

Andes, to affect other cities in less than a

month. Within six months the disease had

marched to neighbouring countries. Since

January 1991 cholera has taken a fearful toll

of 2,681 lives in Peru alone; the reported

number of cases is 2,81,513. By the begin_ ning of this year close to four lakh cases and

more rhan"3,00Qdeaths'hive been reported

from 15 countries. The accompanying table

-. Economic and Political Weekly ’ Auguit 22,' 1992

A,-.

■.

• _■

r_.2.

k.--

inrfly.

be

cd

ru,

iry

rid

ted

me

tre

ter

hny

!>

i*d

of

as

nr

is.

ti

ro

id

ia

of

15tts

lie

id

io

er

i.f

le

i.f

lo

... |e

te

in

■ if

in

id

I’.

r.

i.

h

it

it

tl

b

it

tl

D

11

d

d

d

12

shows the number of cases and deaths in

Latin America since cholera made its debut.

There have been 28 cases, with no mor

tality, so far in the US but alarm bells have

begun to rjng. A recent issue of The Jour

nal of the American Medical Association

(JA.MA) carried an article entitled ‘Cholera

Threatens US Population from Elsewhere in

This Hemisphere* while a weekly watch is

being kept on the depredations of the

disease.

The causes for the current pandemic, the

consequences and the reactions evoked in the

US bring to mind the uncanny if not sinister

resemblance to the 19th century in England

when cholera erupted from her backyard,

India. To this we shall now turn our

attention.

n

India was ‘integrated’ into the world of

capitalism by the British East India Com

pany with the Battle of Plassey. The colonial

loot of the jewel in Britain’s crown was both

instantaneous and staggering. It has been

estimated that the treasure taken from India

alone between Plassey and Waterloo was an

astounding 500 million pounds to a 1,000

million. Thus, while India provided the

capital for Britain's industrialisation began

the process of her own underdevelopment.

The consolidation of the British empire

in India was not as easy as the Spanish con

quest of South America. Several wars were

waged and populations displaced. During

one of these movements of troops broke out

a fearful disease, regarded then as entirely

new but later recognised as cholera. Snow

notes: “In June 1814 the cholera appeared

with great severity in the 1st battalion 9th

regiment NI, on its march from Jaulnah.”

Little however, is heard of this outbreak.

What was of great import, and with grim

consequences, w-as the epidemic breaking

out in August 1817 in Jessore. The Marquis

of Hastings made the following entries in

his diary.

‘73 November, 1817: The dreadful

epidemic, which has been causing such

ravages in Calcutta and the southern pro

vinces, has broken out in camp... I march

tomorrow, so as to make the Pohooj river,

though I must provide carriage for 1,000

sick.

75 November. 1817: We crossed the Pohooj

this morning. The march was terrible, for

the number of poor creatures falling under

the sudden attack of this dreadful infliction

and from the quantities of bodies of those

who died in the wagons, and were necessarily

put out to make room for such as might be

saved by the conveyance. It is ascertained

that 500 have died .since yesterday!’

While the toll on the British army was no

doubt fearful, that on the population of the

country was devastating although of course

no reliable estimates are available. One

estimate placed cholera mortality in the four

years between 1817 and 1821 in British India

at 18 million deaths. Over the next few years

Economic and Political Weekly

the disease fanned out across neighbouring

countries advancing along three discrete

routes. To the west through Persia and up

the river Tigris to Baghdad, spreading thence

via camel caravans to Syria and southern

Russia. To the east the disease marched

through Burma, Malaya, Java and the

Philippines where a number of Europeans

were massacred with the not-all-toomistaken belief that they had spread the

disease. For as the empire opened up to trade

new pans of the globe, there were forged new

epidemiological links in disease transmis

sion. To the nonh the disease conquered the

vast land mass of China.

_ Was the disease in fact new? Or was it

merely unfamiliar to British doctors? Had

a new, and more virulent, strain of the

disease come into existence? The ease with

which the El Tor cholera vibrio originating

in the Celebes in 1964 replaced the classical

cholera vibrio in Asia in a few years admits

the plausibility of this speculation. It is more

likely, however, that colonial intervention

had altered the ecology of the disease.

McNeill, for instance, suggests that “old and

established pattern of cholera endemicity in

tersected new British-imposed patterns of

w trade and military movements. The result

was that cholera overleaped its familiar

bounds and burst into new and unfamiliar

territories where human resistance and

customary reactions to its presence were

totally lacking?

The next wave of this worldwide epidemic

or pandemic reached Moscow in 1830 and

soon spread over Russia, eastern and central

Europe. Hungary was particularly badly af

fected; in less than three months over a

quarter of a million were affected and nearly

1,00,000 died. The disease established itself

soon at the Baltic sea pons, to the horror

of the British; for, a major pan of Britain’s

trade passed through these pons. Repons

meanwhile poured into London of a ternble

outbreak in the Middle East taking, it was

claimed, 30,000 lives in Cairo and Alexan-

dria in one day. The British government wai

ched with macabre fascination and terror

The king’s speech at the opening of parlia

ment on June 21, 1831 observed:

“It is with deep concern that I have to an

nounce to you the continued progress of a

formidable disease... in the eastern part:

of Europe... I have directed that precau

tions should be taken against the introduc

tion of so dangerous a malady into th

country’ As Snow notes “cholera began

spread to an extent not before known... I

approach towards our own country, after

entered Europe, was watched with more

tense anxiety than its progress in other dire

tions.”

Everywhere the disease was observed •

have terrible social, political and dem

graphic consequences. The disease occurr

despite whatever measures governments

the people—in some cases'driven in

religious, penitential frenzy—took. In Russ

troops were deployed around affected vilk

ges with orders to shoot starving peasan:

• struggling to escape. But the disease spree,

to neighbouring communities. Prussic

equally true to her heritage, stationed he

army at the borders; to no avail The dolef

influence of Malthus’ An Essay on the Pri.

ciple of Population, published in th

historic year of the French Revolution, w.

now being felt on the continent with fea.

ful consequences. Convinced that the disea.

was a conspiracy of the ruling class ar.

physicians to bring down the population c

the poor—for it was strange, if not sinister

that both members of the ruling class ar..

physicians seemed relatively unaffectedpeasants attacked several manors i

Hungary, butchering the nobility. The arm

was, of course, called in but in several cas.

the men had deserted and shot their officer

In St Petersburg occurred the first ‘choier

riot’, to become familiar later in England

The riot came to an end when the Czar ap

peared, falling on his knees on the street t.

offer a public prayer that-his country b

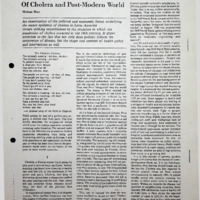

Table: Latin American Epidemic

Country

Month of

1st Report

Cases

Deaths

Dcath-to-Case

Ratio (Per Cent

Bolivia

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Ecuador

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

Mexico

Nicaragua

Panama

Peru

United States

Total

August

May

April

March

February

August

July

October

June

November

September

January

April

109

2611

411

9774

39154

709 +

2247

5+

2028 +

l+

696 +

281513

16 +

336554

6

3

2

132

600

25

36

0

25

0

20

2631

0

3538

7

1

5

....... 1.3 .. .

1-5

3-5

1.6

0

12

0

2.9

0.9

0.0

1.05

• By countryift the Americas, as of November 19, 1991 (data are from the Pan American Health

Organisation).

+ Laboratory-confirmed cascsjonly.

Source: JAMA, vol 267, no 10. March 11. 1992.

August 22, 1992

1793

spared the disease. The disease revived forgot cholera was kept out of the island. The

Qeneral's office was the remarkable utili

board’s recommendation that quarantine

tarian Edwin Chadwick whose work saved

ten horrors of the Black Death in public

measures be strengthened was vigorously op

more lives than all the doctors in the 19th

memory. The psychological impact of the

posed by the city and business interests and,

century. Assisting him was William Farr who

approach of cholera has been noted to be

indeed, the .Admiralty, which claimed they

raised medical staiistics to a science. Behind

unique. Says Vigarclld, “It seemed capable

would not be able to adequately help imple

of penetrating any quarantine, of by-passing

them both in their endeavours were the

ment

these

measures.

The

compromise

any man-made obstacle. It chose its victims

enlightened public, amongst them Carlyle

evolved placed the responsibility squarely on

and Dickens. Chadwick’s conversion from

erratically, mainly but not exclusively, from

a poor law reformer to a public health cam

the lower classes. It was, in short, both uni non-existent or ineffective local governments.

When cholera at last made its long feared

paigner was due mainly to his consideration

quely dreadful in itself and unparalleled in

appearance from Hamburg in the port town

for financial economy. For in his view, it was

recent European experience Reaction was

of Sunderland, the first reaction was to deny

wasteful that every year thousands of

correspondingly frantic and far-reaching.”

its existence. Commercial interests in the

Indeed it would be no exaggeration to say

widows and their children were thrown on

town, aided by doctors, were vehement that

to the poor rates by the death of the bread

that cholera was one of the twin spectres that

the port was disease-free. The same situa

haunted Europe in early 19th century; the

winner .of the family.

tion prevailed later when London was struck;

other was, of course Revolution.

Chadwick’s investigations and zeal lead

The London Medical and Surgical Journal,

io the presentation to parliament of The

As England anxiously watched the ravages

supported by a solid body of doctors main

Report on the Sanitary Condition of the

of the disease on the continent, fearful of

tained that it was a false alarm. The Lancet

■Labouring Population of Great Britain in

ns arrival, the unresolved conflict between

editorially beseeched “the members of the

1942. The Report was loaded with hard hitmiasmatic and contagionist schools of

medical profession not to be misled by the

disease causation came to a head. The

ling statistics and made pragmatic economic

commercial cry that malignant cholera is not

sense. Striking for instance was the data on

former, going back to Hippocratic days, held

in the metropolis”.

life expectancy: in Derby it was 49 years for

that disease was caused by miasma (mean

Cholera swept through England, Scotland

the gentry, 38 for a tradesman but only 20

ing stain); miasma emanated from spoilt air

for a member of the working class. In Leeds

or atmosphere. Putrefaction, decay and din . and Ireland reserving its horrors especially

for those towns and cities that had grown

were therefore, at the heart of the miasmatic

the figures were 44, 27 and 19 respectively.

rapidly during the industrial Revolution. For

The Report stressed the enormous waste of

theory of disease causation. These pro-cesses

here huddled in over-crowded slums, sans

potential labour and hence of money, caus

were of course, central to the florid lives of

water, sanitation, air and sunlight were the. ed by preventable disease, pointing out that

the tropics, wherein emanated cholera, with

impoverished workers; the only certainty in

their excesses of heat, humidity and indeed

it would be far cheaper to put the cities in

their lives was the insecurity of employment.

order. In this the report echoed the practi

of passions as opposed to the cool, the dry

They were cholera’s natural victims.

tioners of the new science of political

and the temperate. Diseases thus had

As the disease spread, so did panic Towns

geographic, meteorological and ecological

economy, who like the Physiocrats before

were deserted by those who could afford to

causes.

them, saw the wealth of the nation, in terms

flee, carrying the disease into the hinter

of efficient labour. The sanitary maps in the

The contagionist aetiology of disease or

lands. What cholera did. above all, was to

Report showed how cholera cases clustered

the germ theory of disease, all loo often at

expose the unbelievable poverty hidden

tributed to Robert Koch in the late 19th cen

together in the poorest and worst drained

behind the facade of metropolitan prosperi

areas. Chadwick’s labours led to the setting

tury, goes back in fact to as early as 1546

ty.

Cholera

unveiled

the

rotten

underbelly

of

and Giraiamo Fracastoro. Fractastorius

up of a Royal Commission on The Health

capitalism; of the poverty, squalor and

maintained that disease was caused by

of Towns. The Royal Commission’s two

misery of the people on which it was built.

discrete animalcules transmitted through

reports, based on a detailed study of 50 large

To the Bread Riots, the Luddite riots and

human interaction. The contagionist theory

towns with the highest death rates was dam

the Chartist riots in early 19th century

provided the basis for the elaborate medieval

ning. All these reports however came to

England were added the cholera riots. Given

Mediterranean quarantine regulations,

naught, parliament was loath to pass the

the very high mortality in hospitals—experi

enacted to guard against plague. The conta

Public Health Bill recommended.

ence had, not incorrectly, convinced the poor

gionist theory, however, fell victim to

But the bill had a powerful ally—cholera,

that chances of survival in hospitals were

Napoleonic ambitions. His. adventure to

readying itself for another onslaught in 1948.

Santa Domingo had been laid low by yellow distinctly less than if they suffered-in their

It was finally the threat of cholera, accom

homes, and the general distrust of upper

fever; when yellow fever broke out in

panying the age of revolutions of 1848,

class doctors and the fears of the sacrilege

Barcelona in 1822 French physicians were

which led to the passage of the Public

of post-mortem riots occurred at several

asked to make a ‘definitive’ study of disease

Health Bill and the establishment of a new

towns. Mobs raided hospitals, smashing

causation. They concluded that there was no

Board of Health. Public health was finally

everything in sight and delivered patients to

possibility of contact among the victims of

acknowledged as the responsibility of the

their homes. Seldom before had the medical

yellow fever—not having known of the role

state.

profession been exposed to be so impotent

of the insect vector, mosquito. The con

Six pandemics of cholera reached England

even

as

they

bickered

over

what

caused

tagionist theory of disease aetiology was

in the 19th century, five of them emanating

cholera,

how

it

spread

and

how

to

cure

it.

thence given a premature demise. Medical

from Ihdia. But the importance of cholera,

When cholera receded it had left 60,000

reformers were henceforth at the forefront

as indeed of all infectious diseases, declin

dead. It also left behind in the minds of a

of efforts to dismantle the quarantine

ed as England completed her sanitary revolu

section of the middle class, the sanitary idea.

regime. They were vociferously supported by

tion and improvements occurred in nutrition

Most crucial to this concept was the under

British free traders. Regulations on free

and the general standard of living. It is

standing that the poor did not choose to live

trade, it was argued, was a superstitious relic

significant that this decline occurred prior

of contagionist fears not based on scientific

in squalor. The sanitary idea embraced the

to the discovery of the cause of the disease.

empirical facts.

need for hygienic housing, clean piped water

The sway of the miasmatic theory of. disease

The government in Britain was now in the

in adequate quantities, efficient sewers and

was, however, so strong that when Snow

throes of a crisis over the agitation for the

paved roads.

published his remarkable findings, a classic

Reform Bill. But when cholera broke out in

The reformed parliament in 1933 passed

in epidemiologial research, On the Mode of

Hamburg in 1831—a port with which

the Registration Act for the compulsory

Communication of Cholera in 1849, it was

England had vast maritime contact, a board

registration of births and deaths; it also

largely ignored. The tide of sanitary reform,”

...oLhealth was set up. The primary respon- -• passed the notorious Poor Law’s. The author

however, could not be ignored; it swept

sibility of the board was to ensure that

of the Poor Laws, manning the Registrar - • through the continent also. The urban land-

1794

...

and Political Weekly ' August 22, 1992

scape of Paris was transformed; the Second

Empire rebuilt the city with wide boulevards

as much to let in air to ward off noxious

miasmata as to control revolutionary mobs.

And Germany, having completed her sani

tary reform, was rewarded with seeing

cholera now respect boundaries, this time

sanitary.

Cholera, then, became a disease of the

Other: a tropical disease. But with each new

pandemic from India, the British govern

ment came in for international censure. A

series of international sanitary conferences

took place in 1866, 1874, 1875 and 1885

devoted specifically to cholera and the ques

tion of quarantine. The first conference at

Constantinople in 1886 had embarrassed the

British government" by pronouncing India

the natural home of cholera. Threats of a

trade boycott were in the air; the French

spoke of the possibility of riots breaking out

in Marseilles if the British did not control

communicable diseases in the. Indian ports.

The cholera pandemic of 1861 had, further,

decimated the British army killing one in

every 10. It was not only expensive but

physically not possible to keep shipping in

fresh recruits. Military men in India, par

ticularly after the 1857 uprising, were acutely

aware of the proportion of Europeans and

Indians in the British army and the constant

and large number of the former invalid in

hospitals. All these factors together propell

ed the government to initiate public health

measures in India directed towards protec

tion of the army.

What evolved was a policy of cordon

sanuaire. The British army and important

civilians were to be segregated in sanitary,

self-contained areas, secluded from the

natives. Fears of miasma emanating from

the latter even lead to the construction of

walls between Indian and European troop

locations to keep miasma out. A broad

based sanitary reform on the lines of the

west encompassing the entire population was

never on the colonial agenda—as indeed it

is not in the nationalist agenda of the day;

the government was unwilling to make the

necessary financial expenditures. Sanitary

reforms for the general population compris

ed ad hoc arrangements at pilgrimages.

Arnold observes trenchantly "Cholera in

India was more than a dreaded disease. It

was associated with much that European

medical officers and administrators found

outlandish and repugnant in Hindu pil

grimage and ritual—so much so that the at

tack on cholera concealed a barely disguis

ed assault on Hinduism itself!’ No such

assault on cholera was in fact in the offing;

for, sanitary reforms for the general popula

tion was also blocked on the specious

grounds that they would offend the religious

sensibilities of the people. Cholera thus was

the leading cause of death in India in the

19th century frequently accompanying the

terrible famines which swept ,yario.us.j)arts_

oTthe country.

The reasons for the decline of cholera, as

indeed the decline of death rates in India

commencing in the 1920s, is a matter of con-

t

1

1

1

?

e

1.

c

y

le

d

<g

a.

>n

is

or

se

<w

ic

of

as

n.

pt

d“ I

>92

’

Economic and Political Weekly

be controlled ‘on a war footing’. In other

words while hospitals and medical colleges

came up., primary health centres did not.

In the third plan the Mudaliar Commit

tee’s recommendations came to force. This

HI

committee had noted that the primary health

care system that had evolved bore no resem

The history of cholera throws light on

blance to that visualised by the Bhore Com

some salient issues. First, the occurrence of

mittee. Very curiously, however, the con

disease is not necessarily ‘natural’ but con

tingent on a large number of interlinked

solidation of existing services to be on par

with

the west rather than building up the

socio-economic factors. In other words, a

web of factors resting on a socio-economic

PHC network was recommended. The fami

ly planning programme now took wing. The

milieu not only sets the ground for occur

extension education approach not having

rence of a disease but also contours the

limits of health intervention. Second, it

been successful, the IUCD was relied upon;

focuses attention on the limits to medical

that having proven a failure a targettechnology. Technical solutions offered to

oriented, time-bound programme was laun

problems social in nature, while having great

ched.- During the Third and Fourth Plans

health budgets continued to decline even as

short-term appeal, offer no long-term cure

expenditure on family planning increased

to community health problems. Third, mor

sharply. Health obtained 2.63 and 2.12 per

bidity and mortality are seen to be not mere

ly biological phenomena shared by the

cent; family planning was allocated 029 and

human population. Diseases are not the

1.76 per cent respectively. Over this period

great levellers they arc frequently thought to

the colossal malaria eradication programmes

be; the disease and death load in a popula

suffered a series of set backs. Among other

tion are distributed as unevenly as are

reasons, technical and logistical, one of the

resources. Lastly it shows us above all that

major reasons for the failure of the pro

politics informs not only the occurrence of

gramme was that a health structure, one

disease but the shape and content of health

capable of carrying out surveillance, had not

policy and intervention. That is to say that

been developed adequately. During the Fifth

given a set of health problems imagpnmuniPlan health and family planning received

ty, it is politics which decides w’tHch of these

1.92 and 124 per cent respectively. Even as

problems are important;, and jhese are not

recognition is said to have dawned that

necessarily epidemiological imperatives.

“development is the best contraceptive” this

Politics also determines whichb'f a possible

plan period witnessed the use of brutal

range of interventions is selected.

methods to obtain family planning targets.

Now, how does all this have any remote

And in view of the continuing set backs to

bearing en India in the late'20th century?

the malaria eradication programme, a nr*

Is it relevant now at the dawn of a brave new

strategy for the control of malaria was drawn

up: eradication became a long-term objec

world? To consider these questions we shall

tive. Efforts were belatedly made now to in

briefly survey the evolution of health services

tegrate the vertical programme; a task not

in India.

At the glimmerings of the dawn of indcyet adequately achieved.

pendence in India was established the Bhore

During

the

‘ Sixth Plan

.................................

health and family

Committee to draw up the blue-print for the

planning received 1.86 and 1.03 per cent of

the budget respectively.- In a departure from

health system of India. In view of the quan

previous plans the Sixth provided for an in

tum and nature of the health problems in

crease in the allocation for rural health. This

the country the Bhore Committee drew up

was, however, at the expense of preventive

a plan that laid emphasis on preventive ser

vices focusing on rural areas linking health

programmes: reduction of medical expen

to overall development. These recommenda

diture was only 4 per cent whereas that for

tions were considered eminently feasible

the control of communicable diseases was

within available resources; they were ac

II per cenu The family planning programme

cepted as the.mimmum irreducible if a dent

now came to be directed at poor women

was to be made on the health profile of the

whose reproductive profligacy was con

country.' The recommendations were ac

sidered the cause of the country’s poverty.

This period also witnessed official policy to

cepted by the government of India; they were

encourage the corporate sector to enter the

not however to sully the conscience of our

planners. During the first two plan periods

health market.

The Seventh Plan made some efforts

health obtained 3.3 and 3 per cent of the

towards strengthening health infrastructure.

total plan outlays, much below the irreduci

Health and family planning were allocated

ble minimum of 10 per cent recommended

l.SS and 1.80 per cent of the budget respec

by the Bhore Committee. Further within this

tively. Yet towards the end of this period,

budget, 55 to 60 per cent was allocated to

curative health services and to medical

given the lack of correlation between pro

gramme performance and birth rates, it was

education. Public health obtained a mere

grudgingly acknowledged that the massive

third of the budget. Of the funds available

.fpr. public heahh,--the major .share-was— -family planning programme had not been

successful. With financial incentives from. .

garnered by the vertical programmes like

the state there occurred a mushrooming of

malaria, small pox and soon even family

super speciality institutions for high

planning, for, by the early 1960s, it was

technology curative care during this period.

decided that the number of poor ought to

troversy. One fact however, is generally ac

cepted and that is that public health policy'

and intervention had little to do with the

decline. .

August 22. 1992

1795

i

i

i

i

I

I

i

i

I

t

i

What is striking however, is that in our

country now, not only is the morbidity and

mortality load still high but there has been

no change in their overall character; infec

tious diseases continue to be the major

causes of morbidity and mortality; malnutri

tion continues to be widely prevalent. Data

from the National Nutrition Monitoring

Bureau reveals that while the prevalence of

severe malnutrition has somewhat declined

that of moderate malnutrition has in fact

increased, while the prevalence of mild

malnutrition remains unchanged.

What we have achieved has been to evolve

plural and divorced worlds of health sys

tems. One endowed with advanced and ex

pensive technology, concerned with cancer,

diseases of ageing and so forth and another

at the periphery which fails to confront

preventable morbidity and mortality. The

former attends to the needs of a small

minority whose living standards includes ac

cess to public health services. The latter fails

to recognise that the prevailing morbidity

and mortality arc rooted in poverty and are

therefore, not amenable to technical

solutions.

India is now poised at a new conjuncture.

The World Bank-IMF policies of structural

adjustment is pregnant with dire conse

quences for the health of the majority. They

will further wrench apart the distance bet

ween these dual health systems. The cut in

health budgets would mean that health in

stitutions, on the verge of collapse, may

simply go under. Al the recent World Health

Assembly in Geneva the minister for health

and family welfare declared that we do not

have sufficient resources for primary health

care. Reports, meanwhile, have come in of

cholera deaths in Tripura and in Bihar; while

Delhi, the most endowed of Indian cities, has

started reporting cases of cholera. The threat

of cholera flaring up again therefore,

persists.

These are not merely Cassandra’s fears.

Data not just from Peru but a number of

other countries that have implemented the

World Bank-IMF dictated policies of struc

tural adjustment reveal the grim conse

quences of these policies. UNICEF’s The

Stale of the World’s Children 1992 notes that

given the problems of external debt, of

declining terms of trade and of protec

tionism in the markets of the First world the

1980s were disastrous economically for the

majority of the countries of the developing

world. It states “UNICEF has watched the

deterioration of that economic environment

being translated, in many countries, into ris

ing malnutrition, preventable disease and

falling school enrolments”. The. report fur

ther goes on to warn that “the developing

world will find it difficult to find a place in

the new world order”.

To illustrate, a 10-country study on the ef

fects of recession and structural adjustment

on_heakh, published by UNICEF, showed

a deterioration in the nutritional.status of

children in eight of these countries. Infant

and child mortalit/ rates which had been

declining for two decades since the 1960s

showed either a reversal of the trend or a

slowing down of the rate of decline. Data

from Zambia show that between 1980 and

1984 hospital deaths due to malnutrition in

creased from 2.4 to 5.7 per cent in the 0-11

months age group and from 38 to 62 per cent

in the age group 1-4 years. Between 1980 and

1985 infant mortality rates went up from 146

to 168 in Ethiopia, from 97 to 108 in

Uganda, from 103 to 110 in Tanzania and

from 87 to 91 in Kenya. Similarly childhood

mortality rates went up from 32 to 38 in

Ethiopia from 18 to 21 in Uganda, 19 to 22

in Tanzania and 15 to 16 in Kenya over the

same period.

The devastation to people’s health and liv

ing conditions in the developing world has

lead to calls by UNICEF for “adjustment

with a human face”. As India prepares to

tread the same path some sobering reflec

tion is called for. Are we prepared to con

demn the country, in perpetuity, to be a ‘fac

tory of disease’?

Notes

Stockholm, 1982.

Snow, John, On the Mode of Communication

of Cholera, John Churchill, London, 1855,

reprinted USAID, New Delhi, 1965.

UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children,

1992, OUP, Delhi, 1992.

Vigarello, G, Concepts of Cleanliness: Chang

ing Attitudes in France Since the Middle

Ages, CUP, Cambridge, 1988.

*

‘Cholera: Fall Out of New Economic Order’,

EPW, Vol XXVI, no 34, p 1941, August 24,

1991.

‘Epidemic Cholera in Latin America’, The Jour

nal of the American Medical Association,

vol 267, no 10, March II, 1982.

‘Cholera Threatens US Population • from

Elsewhere in this Hemisphere’, ibid.

‘Cholera in the Americas’, JAMA, vol 267, no

11,‘March 18, 1992.

‘Epidemic Kills 32 in Darbhanga’, The Times

of India, New Delhi, May 30, 1992.

‘Over 3-Fbld Rise in Cholera Cases’, The Times

of India, New Delhi, May 22, 1992.

■Diarrhoea Claims 86 Lives in Bihar’, The

Times of India, New Delhi, June 2, 1992.

Tripura Epidemic Claims 150 Lives’, The Times

of India, April 23, 1992.

[I am grateful to Padma Prakash for not only

mooting the idea of this paper but also sup

plying me with data from JAMA. 1 am alone

responsible for errors and infelicities.]

0

’4

BBS

rfi

I

Bibliography

Arnold, David (cd). Imperial Medicine and In

digenous Societies, OUP, New Delhi, 1989.

—, ‘Cholera Mortality in British India

1817-1947’ in Dyson (ed), India's Historical

Demography, Curzon Press, London, 1989.

Chossudovsky, Michel, ‘Under the Tutelage of

IMF. The Case of Peru’, Economic and

Political Weekly, February 15, 1992.

Cornia, G, Jolly. R and Stewart, F, Adjustment

with a Human Face, Clarendon, Oxford,

1987.

Guha, Sumit, Environmental Sanitation in the

Health Transition: India and the West in the

19th and 20th Centuries, paper presented

at the NCAER workshop on Health and

Development in India, New Delhi, January

1992.

Kanjt et al, ‘From Development to Sustained

Crisis: Structural Adjustment. Equity and

Health’, Social Science and Medicine,

vol 33. no 9, 1991.

Klien, Ira, ‘Cholera, Dysentery and Develop

ment in Eastern India 1871-1921*. Journal

of Indian History, Golden Jubilee Volume,

1973.

Longmate, N, King Cholera: The Biography of

a Disease, Hatnwfi Hamilton, London,

1966.

McNeill, W, Plagues and People, Penguin, Harmondsworth. 1979.

Naraindas, Harish, Poisons, Putrescence and

the Weather: A Genealogy of the Advent

of Tropica! Medicine, unpublished paper

presented at CSDS workshop, Delhi. 1990.

Park. J E. A Textbook of Preventive and Social

Medicine, Bhanot. Jaipur. 1991.

Qadecr, 1, ‘Beyond Medicine: A Analysis of the

Health Status of Indian People’, Think/

India, vol 2, no 1, January 1990. . •

Ramasubban, R, Public Health and Medical'

Research in India: Their Origins under the/

Impact of British Colonial Policy, SA REC, •

Please Contact:

©

CYAN BOOKS PVT. LTD.

5, Ansari Road, New Delhi-110002

Phones : 3261060, 3282060

Fax : (Oil) 2511737 Attn. GYAN

GEOGRAPHY OF INDIA

Prithvish Nag & Smia Sengupta

Rs. 300

The book provides a means to know

more about the geography of India.

Apart from the conventional themes, new

themes like environment and Indian

Ocean have been Included. Special

attention has been made to add the

recent development.

The contents of the book would meet the

requirementsol graduate or post-gradu

ate courses In geography of India In

different universities. It should prove use

ful to social scientists, planners, geogra

phers. geologists and the like.

AusetCil collection In tne libraries.

Publishers:

CONCEPT PUBLISHING COMPANY

A/15-16, Commercial Block, Mohan Garden

NEW DELHI-110059 (India) Ph: 5554042

i

“----------------- •• — ■ ' ----------------- ------------------------------------i

,..7..-Economic and Political Weekly

1796

I

...

..

. ..

2_.

‘

_____ ____

‘‘ -C-i--'— •

•

' -

August 22, 1992

;

'

~

"

Position: 1392 (9 views)