SDA-RF-CH-1A.15.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

&

;.1'£nS

■

SDA-RF-CH-1A.15

CH- 'A- pr

.I

Among children under 4 months of age, full breast

purchasing power, and the increased tendency of urban

feeding is more common in rural areas than in urban areas

women to emulate Western-style infant feeding practices.

across countries in all regions (Table 3.9). In sub-Saharan

Table 3.17 presents a regional summary of current feeding

Africa, the highest rate of full breastfeeding is in rural

practices for infants less than 4 months of age by urban- j

Rwanda, at 93 percent, and the lowest rate is in rural

rural residence, and Figure 3.4 shows urban-rural differen

Burkina Faso, at 33 percent. In Burkina Faso, Ghana, and

tials for full breastfeeding for this age group by region.

Niger, there are no differences between urban and rural

areas, but in the other sub-Saharan countries, full breast

Table j . 10 presents current status feeding practices

feeding is more frequently practiced in the rural areas. In

among children 6 to 9 months, by urban-rural residence. By

Near East/North Africa, the highest prevalence of full

that age, children should be receiving complementary foods

breastfeeding is rural areas of Morocco (77 percent), the

in addition to breast milk. Overall, urban-rural differences

lowest is in urban areas of Turkey (31 percent). In Asia, the

in the percentage of children 6 to 9 months of age receiving

highest rate of full breastfeeding is in rural Nepal, at 85

complementary foods areas are small in most countries.

percent, the lowest in urban Pakistan, at 16 percent. In

Figure 3.5 shows those differences by region. In Latin

Latin America/Caribbean full breastfeeding is, in general,

America/Caribbean, Near East/North Africa, and Asia, the

less common than in the other regions, but the highest rate

percentages of children receiving breast milk and comple

is in rural Peru, at 75 percent, and the lowest in urban Haiti,

mentary foods are higher in rural than in urban areas, ^his

at

ircent. The higher rates of full breastfeeding in rural

pattern reflects the greater likelihood that urban infants are

ireas reflect a combination of the need for urban mothers to

weaned somewhat earlier than rural infants, which is

return to the workplace more often than rural mothers and

evidenced by the higher percentage of children in urban

therefore begin weaning earlier, the greater availability and

areas not breastfeeding, particularly in Near East/North

narketing of infant foods and milk products, greater urban

Africa and Latin America/Caribbean (see Table 3.18).

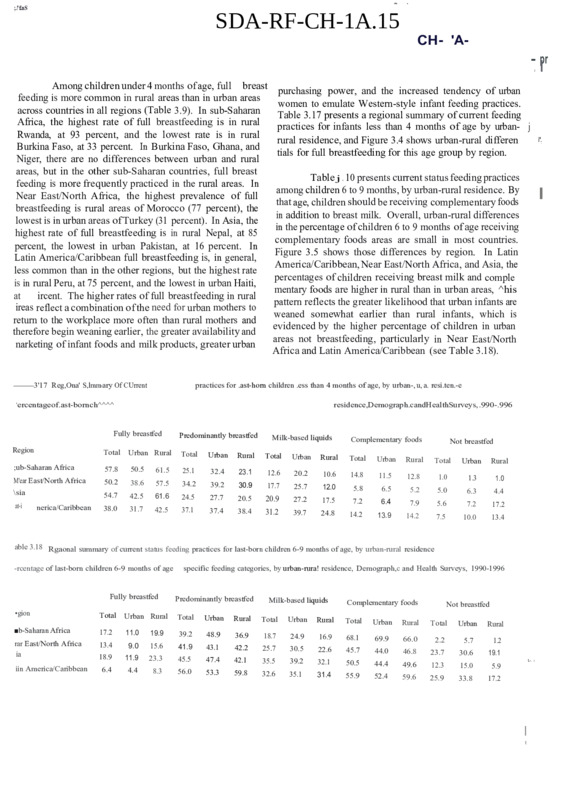

—3'17 Reg,Ona' S,lmm-ary Of CUrrent

practices for .ast-horn children .ess than 4 months of age, by urban-, u, a. resi.ten.-e

‘ercentageof.ast-bornch^^^^

residence,Demograph.candHealthSurveys, .990-.996

Fully breastfed

Predominantly breastfed

Milk-based liquids

Region

Total

Urban Rural

Total

Urban

Rural

Total

;ub-Saharan Africa

57.8

50.5

61.5

25.1

32.4

23.1

M'ear East/North Africa

12.6

50.2

38.6

57.5

34.2

39.2

30.9

17.7

\sia

at-i

nerica/Caribbean

Urban

Complementary foods

Not breastfed

Rural

Total

Urban

Rural

20.2

10.6

14.8

11.5

12.8

1.0

1.3

1.0

25.7

12.0

5.8

6.5

5.2

5.0

6.3

4.4

Total

Urban

Rural

54.7

42.5

61.6

24.5

27.7

20.5

20.9

27.2

38.0

17.5

31.7

7.2

42.5

37.1

6.4

37.4

31.2

7.9

38.4

5.6

7.2

17.2

39.7

24.8

14.2

13.9

14.2

7.5

10.0

13.4

able 3.18 Rgaonal summary of current status feeding practices for last-born children 6-9 months of age, by urban-rural residence

-rcentage of last-born children 6-9 months of age

Fully breastfed

specific feeding categories, by urban-rura! residence, Demograph,c and Health Surveys, 1990-1996

Predominantly breastfed

Milk-based liquids

Complementary foods

•gion

Total

Urban Rural

Total

Urban

Rural

Total

Urban

Rural

■b-Saharan Africa

17.2

11.0

19.9

39.2

48.9

rar East/North Africa

ia

36.9

18.7

24.9

13.4

16.9

9.0

68.1

15.6

41.9

43.1

42.2

25.7

30.5

18.9

11.9

22.6

23.3

45.7

45.5

47.4

42.1

iin America/Caribbean

35.5

39.2

6.4

32.1

4.4

8.3

50.5

56.0

53.3

59.8

32.6

35.1

31.4

55.9

Total

Urban

Not breastfed

Rural

Total

Urban

69.9

66.0

2.2

5.7

1.2

44.0

46.8

23.7

30.6

19.1

44.4

49.6

12.3

15.0

5.9

52.4

59.6

25.9

33.8

17.2

Rural

L-. ■

I

t

i".

■

I

I

Table 3.12 presents

_______current status feeding practices

Among children 12 to 15 months of age, there are

months

W

23

for children 20 to

- by- urban-rural resi- «

-------- of age,

•stantial differences between urban and rural areas m

dence. The proportion of children not breastfeeding at this

t-year breastfeeding continuation rates, with rural areas

age is important because it represents the inverse of the i

astfeeding significantly longer, as shown in Table 3.11.

second-year breastfeeding continuation rate. As with

tble 3.11 shows the percentage of children not breastchildren 12 to 15 months of age, urban children 20 to 23 |

ding, the inverse of the first-year continuation rates.) In

months are more likely to not be breastfeeding than their

rural counterparts, reflecting the fact that they are weaned t

i-Saharan Africa, urban Namibia, at 51 percent, has the

earlier. The lowest second-year continuation rates are .»

hest rate of non-breastfeeding at 12 to 15 months (i.e.,

found in urban areas of the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, |

lowest first-year continuation rate), followed by urban

Turkey, and Morocco; the highest second-year continuation 1

meroon at 32 percent. In Near East/North Africa,

rates are in the rural areas of Bangladesh, Nepal, Rwanda, |

>rocco has the highest urban non-breastfeeding rate (64

and Burkina Faso. It is evident from Figure 3.7, depicting 1

cent); in Asia, the Philippines (56 percent); and in Latin

overall urban-rural differences in the second-year breast- J

..lerica/Caribbean, the Dominican Republic (86 percent),

feeding rate by region, that the longest breastfeeding occurs |

mre 3.6 shows the overall urban-rural differences in nonin Asia, followed by sub-Saharan Africa. This pattern was |

at 12

>a. iding rates

to 15 months of age

seen Inwith the median breastfeeding duration data (see ■ |

------------~ byi region.

tin jAmerica/Caribbean and Near East/North Africa, rural sectjon 2.4). Latin America/Caribbean and Near East/North |

ren are

are breastfed about 30 percent more often Jhan

have similar second-year continuation rates overall f |

ildren

|

and in rural areas; in urban areas the second-year continuaban children, in sub-Saharan Africa about two-thirds

tion rates are higher in urban Latin America/Caribbean than I

)re often, and in Asia about twice as often. Table 3.19

in urban Near East/North Africa. Table 3.20 is a regional |

esents a regional summary of current status feeding

summary of current status feeding categories for children 20 v

actices for children 12 to 15 months of age, by urban-rural

to 23 months of age, by urban-rural residence.

j

sidence.

Figure 3.6 Percentage of children 12 to 15 months

of age not breastfeeding, by urban-rural

residence and region

Percent

60 ----------

40

Sub

Ne

Asi

La

■:i I •

42

34

33

29

30

0

Reg

53

40

10

Perc

50

50

20

Tab]

.n

I

E3Total

□Urban

■ Rural

---

20

16

17

6

Sub-Saharan

Africa

Note: Based on last-born children only

-•'Mi HI

Near East/

North Africa

1

Asia

Latin America/

Caribbean

Source: DHS Surveys 1990-1996

Current status feeding practices for children less

than 4 months of age by mother’s education are shown in

Table 3.13. Full breastfeeding is most common among

children of mothers with no education across all regions. In

Asia, however, there is no overall difference in prevalence

of full breastfeeding between children of mothers with no

education and those with mothers having primary school

education. In general, full breastfeeding declines with

increasing level of education. The largest differences are in

sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, where children of women

with primary education are more than 20 percent more

likely to be fully breastfed than children of women with

higher education. Children of more educated women

receive more water- and milk-based liquids. A regional

summary of current status feeding practices for children less

tHn 4 months of age, by mother’s education is presented in

i & 3.21. Figure 3.8 shows the regional prevalence rates

for full breastfeeding by mother’s education.

Current status feeding practices for children 6 to 9

months of age by mother’s education are shown in Table

3.14. As noted, the indicator of interest at this age is the

percentage of children receiving complementary foods. In

Latin America/Caribbean, the proportion of infants breast

feeding and receiving complementary foods declines with

increasing level of education (see Figure 3.9), whereas the

opposite is true in Near East/North Africa and sub-Saharan

Africa. This may reflect the tendency among more edu

cated women in Latin America/Caribbean to wean infants

earlier, thus lowering the overall prevalence of breastfeed

ing in this group. In Asia, the percentage of infants receiv

ing complementary foods is lowest among uneducated

mothers, followed by those with secondary education or

r e, and highest among the group with primary education.

A icgional summary of current status feeding practices for

infants 6 to 9 months of age by mother’s education is

presented in Table 3.22.

At 12 to 15 months, mother’s level of education

affects first-year breastfeeding continuation rates, as shown

in Table 3.15 and Figure 3.10. There is a strong positive

relationship between the proportion of children not breast

fed at this age and mother’s level of education, particularly

in Latin America/Caribbean, where the first-year breast

feeding rates are lowest among the most educated women.

Clearly, with increasing education women discontinue

breastfeeding earlier. This pattern is due to a variety of

factors including the return to the workplace, increasing

demands on women’s time, and exposure to Western infant

feeding practices. Regionally (Figure 3.10), Latin Amer

ica/Caribbean countries have the widest variation in the

proportion not breastfeeding according to mother’s educa

tion, and Near East/North Africa countries the least. A

regional summary of current status feeding practices for

children 12 to 15 months of age by mother’s education is

shown in Table 3.23.

At 20 to 23 months of age (see Table 3.16), the

relationship between mother’s education and the proportion

of children not breastfeeding is similar to the pattern seen

at 12 to 15 months. As expected at this age, many more

children are not breastfed across all countries and levels of

education, i.e., the second-year breastfeeding continuation

rates are lower than the first year’s. As Figure 3.11 shows,

the second-year continuation rates are highest in the Asian

countries, again reflecting the tradition of long breastfeed

ing duration in this region, and lowest in Near East/North

Africa. A regional summary of current status feeding

practices for children 20 to 23 months of age by mother’s

level of education is shown in Table 3.24.

Table 3.21 Regional summary of current sunus feeclinu practices for last-born children less than 4 months of age, by mother's education

Percentage of last-born children less than 4 months of age in specific feeding categories, by mother’s education. Demographic and Health Surveys, 1990-1996

Fully breastfed

cation

Sub-Saharan Africa

62.9

Near East/North Africa

55.8

Asia

62.9

Latin America/Caribbean 65.8

82

Milk-based liquids

Complementary foods

Not breastfed

higher

Second No

No

SecondSecond

ary or edu

eduary or

ary or

cation Primary higher cation Primary higher cation Primary higher cation Primary higher

57.0

38 6

20.1

25.2

34.6

9.8

12.0

30.0

13.1

16.0

13.9

0.5

1.1

1.5

42.7

42.2

33.8

40.8

40.7

14.7

18.9

19.8

5.1

6.9

5.2

2.3

5.7

5.3

63.0

40.0

21.0

19.0

35.6

15.2

16.1

31.1

10.0

8.9

6.7

1.8

3.3

7.4

54.2

49.3

17.5

26.6

29.1

12.1

14.9

19.3

8.5

13.3

13.5

0.7

2.2

2.4

Second

ary or

No

edu

Region

Predominantly breastfed

Primary

No

edu-

Second- No

ary or edu

=1 :

43

Figure 3.11 Percentage of children 20 to 23 months of age

not breastfeeding, by mother's level of education and region

100

Percent

81

74 H

- -77

80

■

76

64

62

60

□No education

□ Primary

M Secondary+

41

40

33

20

0

Latin America/

Caribbean

Near East/

North Africa

Sub-Saharan

Africa

Asia

Note: Based on last-born children only

Source: DHS Surveys 1990-1996

Table 3.24 Regional summary of current status feeding practices for last-born children 20-23 months ol aizc, by mother's education

Percentage of last-born children 20-23 months of age in specific feeding categories, by mother’s education. Demographic and Health Surveys, 1990-1996

Fully breastfed

Predominantly breastfed

Second

Second- No

ary or eduary or

Primary higher cation Primary higher

Not breastfed

Region

Sub-Saharan Africa

4.2

1.2

0.3

22.4

23.1

14.5

8.6

7.6

10.0

59.8

43.2

20.1

32.7

53.9

76.1

Near East/North Africa

2.4

0.7

0.2

18.1

15.0

12.3

13.0

14.1

7.4

29.2

22.6

17.0

64.4

73.5

81.3

Asia

4.3

1.3

0.1

48.4

43.4

32.8

27.9

28.4

25.4

69.5

57.3

36.9

19.1

33.2

61.7

Latin Amenca/Caribbean

1.2

0.4

0.2

50.1

25.8

21.7

14.7

12.6

16.7

55.7

25.4

20.2

41.1

70.7

77.2

Feeding practices were examined by sex of child as

; well as by socioeconomic characteristics (see Tables 3.25

through 3.28). In this section as in the previous, full breast

feeding is presented in the tables rather than exclusive breast

feeding because of the small number of cases of exclusive

breastfeeding in most countries. The results indicate that

feeding practices do not vary substantially by sex, at any age, in

> any of the countries studied Among infants under 4 months,

S however, in all regions there was a slightly greater proportion of

T female infants fully breastfed overall (Figure 3.12), probably

g. indicative of an earlier introduction of complementaiy foods to

No

edu

cation

Complementary foods

No

education

Sex Differentials

JI

Milk-based liquids

Second No

ary or eduPrimary higher cation Primary

Second

ary or

higher

No

Second

edu

ary or

cation Primary higher

males overall. Among infants 6 to 9 months, only in Asia was

there a slightly greater overall tendency for females to be given

complementary foods (Figure 3.13), a difference not observed

in the other regions. At 12 to 15 months, no differences by sex

in the first-year breastfeeding continuation rates were observed

(Figure 3.14). At 20 to 23 months, the lack of overall sex

differences in second-year continuation rates is similarly seen

(Figure 3.15), although in Near East/North Africa countries

females were 8 percentage points more likely than males not to

be breastfed, that is, boys were breastfed more often in the

second year than girls. The regional summary of feeding

practices by sex of child is shown in Table 3.29.

85

4

Table 3.29 Regional summary of current status feeding practices for last-bom children 20-23 months of age, by sex

Percentage of last-bom children 20-23 months of age in specific feeding categories, by sex of child and region. Demographic and Health Surveys, 1990-1996

Milk-based liquids

Fully breastfed

Predominantly breastfed

Female Total

Male

Female Total

Male

Female Total

Male

Female

Total

Male

Female

47.9

21.0

47.7

48.3

47.2

47.1

47.4

24.1

17.5

74.9

71.4

78.7

53.9

25.3

49.5

51.5

38.3

38.5

38.1

25.1

25.6

71.7

71.6

71.7

Region

Total

Male

Sub-Saharan Africa

3.1

1.6

3.1

3.1

21.6

22.6

20.6

9.1

9.3

8.9

1.3

1.8

15.3

19.4

10.9

9.8

10.3

9.3

2.6

2.4

2.8

41.1

0.6

0.5

0.7

25.0

Near East/North Africa

Asia

Latin America/Caribbean

3^

38.3

24.8

36.9

26.9

23.9

23.2

25.1

12.9

12.6

13.1

MEDIAN AGE AT INTRODUCTION OF

COMPLEMENTARY FOODS

Table 3.30 and Figure 3.16 show the median age of

introduction of complementary foods among last-bom children

less than 3 years old currently breastfeeding. Median age ranges

vary widely across countries and regions. In sub-Saharan

Africa, the median age of introduction varies from a low of 2.1

months in Malawi to a high of 9.8 months in Ghana, with an

overall median of 5.6 months for the region. In general, children

in West African countries are introduced to foods later in life

than children in East and Central African countries. In Asia, the

median age ranges from a low of 2.8 months in Indonesia to a

high of 13.2 months in Pakistan, with the exception of Bangla

desh, where no median could be determined. 5 For the region,

excluding Bangladesh, the overall median is 7.5 months. In

Latin America/Caribbean, the median ranges from 0 months in

the Dominican Repubhc, to 6.7 months in Guatemala, with an

median for the region of 3.9 months (excluding Brazil).

L ue Near East/North Africa, median age at introduction of

complementary foods was calculated at 7.3 months. Additional

tables showing the median age at introduction of complementary

foods by other selected differentials are included in Appendix H.

Not breastfed

Complementary foods

The wide range of ages for introduction of foods across

countries is illustrated in Figure 3.16. If those ages earlier than

4 months are considered “too early” and those later than 8

months are “too late,” it is clear that children in 9 of 18 subSaharan countries, in 2 of 4 Near East/North African countries,

in 3 of 7 Asian countries, and in 2 of 8 in Latin America/Caribbean countries, are being introduced to foods at inappropriate

ages. Timely introduction of appropriately prepared, nutrition

ally adequate complementary foods should be a focus of

programs or improve the health and nutrition status of young

children in many developing countries.

-

1

I

aL

|

|

|

I

I

K-

Socioeconomic Differentials

It is important to remember that the median age

represents the age at which 50 percent of children are introduced

to complementary foods. The remaining 50 percent are intro

duced to foods either at an earlier age or a later age. Thus, in

many countries, although the median age may be around the

recommended time (i.e. 6 months), many children are being

given foods much to early or too late. Both of these situations

may be detrimental to the infant’s health: Too early introduc

tion is associated with increased risk of diarrhea. Late introduc

tion may have adverse effects on growth and development.

Differences in the median age at introduction of J|

complementary foods are shown by urban-rural residence in 1

Table 3.30, and by mother’s level of education in Table 3.31. ■ j

The differentials are of interest in understanding the influence of

socioeconomic status on feeding practices, as proxied by area of

residence and mother’s educational attainment. In sub-Saharan

Africa, only slight differences in the age of introduction of I

complementary foods exist between urban and rural areas. In

Asia, differences of a half month or more (in both directions)

exist between urban and rural areas in 4 of the 5 countries where

medians could be determined, with the exception of Indonesia,

where there was little urban-rural difference. In Pakistan and the

Philippines, median age could not be determined for urban

areas, but it is probably higher than in rural areas, as indicated

by the total figures. In Egypt, complementary foods are

introduced to children in rural areas almost a month later than to

children in urban areas. In the other Near East/North Africa |

countries, medians could not be determined for children still ■

breastfeeding. 6

5 The Bangladesh median could not be calculated because less than 50

percent of breastfeeding children received complementary foods at the

age covered by the survey.

-t of

6 The medians could not be calculated because less than 50 percent

'cred

breastfeeding children received complementary foods at the age cove,

by the surveys.

06

I.

O

. .n

■

Figure 3.16 Median age at introduction of complementary

foods, children less than 3 years old currently breastfeeding

Age (months)

14

13

12

10

10

8

6

4

2

0

9

8

8

illllll I III Jll

6 7 7 7 7

: 7

ii

o,6,<V> o>

Note: Based on last-bom children only

For mother’s level of education, in most countries

where medians could be determined, complementary foods were

introduced earlier with increasing level of education. The

differences are clearest in sub-Saharan Africa because medians

could be calculated for most countries, although among children

of mothers with the highest educational level, cell sizes are

small. In the other regions, the tendency toward earlier introduc

tion of foods with higher level of education is discernible, but

meralizations are problematic because of the lack of median

data or small cell sizes. The earlier introduction of foods with

higher maternal education may reflect the tendency for more

educated women to return to the work force soon after birth,

greater exposure among educated women to information

regarding appropriate timing of complementary foods, greater

economic ability to purchase complementary foods, better

access to markets, or a combination of these factors.

Sex Differentials

Differences in the median age of introduction of

complementary foods by child’s sex are shown in Table 3.32.

Regional averages for sex differences are shown in Figure 3.17,

which additionally illustrates the overall differences in median

age at introduction of complementary foods among regions. In

Latin America/Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa, there were

few differences in age of introduction by sex, although in both

regions foods were introduced to girls slightly earlier than to

98

8

aS.oJ’-CK'-cfe.o?5 oKcP-.ofc.dv’

Source: DHS Surveys 1990-1996

boys. In the Asian countries, sex differences were more

pronounced, with girls being started on complementary foods talmost a month earlier than boys on average (7.7 vs. 8.4

months). In the Near East/North Africa, median age data were

available only for Egypt, where boys were given complementary

foods almost a month earlier than girls (6.9 vs. 7.7 months). Sex |

differences in the age of introduction of foods may reflect

cultural/religious biases and may partially explain differences in

nutritional status, morbidity, and mortality rates, although many

other factors also influence these outcomes.

3.3

TYPES OF FOODS EATEN BY CHILDREN

In addition to breast- and bottle-feeding patterns and

feeding

practices within different age groups of children, .

general

it is important to know what kinds of foods children are eating,

and how often they are fed. Beginning with the third phase of

the Demographic and Health Surveys program (DHS-IH) only, h

mothers were asked what types of food were given to their

children in the 7 days before the interview, and the number of

days in the week the children were given those foods. Table

3.33 presents the results of the weekly recalls for all children

over the age of 6 months. Because the results are from surveys ,

conducted only during DHS-HI, the data are limited to a f relatively small number of countries from sub-Saharan Africa,

Asia, and Latin America/Caribbean.

■

Figure 3.17 Median age at introduction of complementary

foods, by sex and region

10

Age (months)

8

- 8

8

6

6

6

ESMale

□ Female

4

4

3

2

0

Sub-Saharan

Africa

Near East/

North Africa

Asia

Latin America/

Caribbean

Note: Based on last-bom children only

Source: DHS Surveys 1990-1996

Water-based liquids (e.g., juice, tea, broth) are given to

children in most countries about 2 to 3 times per week. In subSaharan Africa, about a third of children are given water-based

liquids in the four countries studied. In Asia, a third of children

are given water-based liquids, on average, but the range is from

10 percent in Indonesia to 53 percent in Kazakhstan. In Latin

America/Caribbean, the range is from 16 percent in Colombia

to 45 percent in Peru.

Feeding of grains (reflecting cereals made from grain or grain

flours) was reported unevenly, with 40 percent or more in the

Central African Republic, Uganda, Bolivia, and Guatemala, but

less than 20 percent in the remaining countries where the foods

were reported. However, the frequency of feeding grains was

3 to 4 times per week. Tubers and plantains (again, probably

reflecting cereals made from these foods) were given to a third

or more of children in all the countries where those foods were

reported. Tubers and grains were given from about 2.5 to 4

times per week. Other complementary foods were also given to

children, ranging from 10 percent in Zimbabwe to 67 percent in

the Central African Republic. Other complementary foods may

include fruits, vegetables, snacks and sweets, garnishes, food

mixes, or other processed foods. When foods of any kind were

considered, more than 90 percent of children in most countries

were given some type of food. In Mali, Brazil, and Colombia,

only 77, 65, and 71 percent of children, respectively, were

reportedly given any foods in the last week. Interestingly, in

Latin American/Caribbean countries, the frequency of feeding

any type of food was about 4 times per week, which is higher

than the average number of times foods were given in either

sub-Saharan Africa (2.9 times per week, on average) or Asia

(3.3 times per week, on average).

Milk-based liquids (i.e., milks other than breast milk)

are also given to children; this type of feeding varies from 3

percent of children in Indonesia to 33 percent of children in

I Zimbabwe. As with water-based liquids, the weekly frequency

of giving milk-based liquids is about 2 to 3 times per week.

At least half of the children in most countries were

\ given eggs, fish, and poultry about 2 to 3 times per week on

average. Nepal was the exception with only a third of children

g receiving these foods, and less than 2 times per week on

; H average. Half or more of the children in sub-Saharan Africa and

llLatin America/Caribbean received red meat about 2.5 times per

iM^Week. Fewer than half of all children in Asia received red meat,

i.. jSwith Nepal at 27 percent again having the lowest prevalence.

101

Figure 3.18 Percentage of children 0 io 11 months of age bottle-fed

Central African Republic 19$

Burkina Faso

12

a.2

B3

P3

■"3

Madagascar 1992

S

K33

SL3

Tanzania 1991-92

Senegal 1992-93

Zambia 1992

Zimbabwe 1994

Uganda 1995

Kenya 1993

Cameroon 1991

Ghana 1993

Nigeria 1990

Namibia 1992

Near East/North Africa

Egypt 1992

Morocco 1992

Turkey 1993

Jordan 1990-91

a. 30

«

Asia

Bangladesh 1993-94

Nepal 1996

India 1992-93

Indonesia 1994

Pakistan 1990-91

Philippines 1993

Kazakhstan 1995

114

, . 15 •

54

Latin America/Caribbean

Haiti 1994

Guatemala 1995

Bolivia 1993-94

Peru 1996

Paraguay 1990

_ brazil 1996

. . .

Colombia 1995

Dominican Republic 1991

31

■

3737

0

85

20

Note: Based on last-born children only

3.4

BOTTLE-FEEDING

Bottle-feeding is not recommended for the vast

majority of infants in developing countries because of the

potentially adverse effects of contamination from water, utensils,

and hands during preparation and storage of formula and other

bottle-feeds, and the potential for overdilution of instant formula

•with water, rendering the bottle-feed nutritionally inadequate.

F’^mre 3.18 presents the percentage of last-bom infants 0 to 11

aths of age currently receiving a bottle. By region, bottle

feeding is least prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa and most

common in Latin America/Caribbean. In sub-Saharan Africa,

the use of bottles is less than 10 percent in most countries; the

highest rate of use is in Namibia, where one-third of infants

receive a bottle. In Latin America/Caribbean, on the other hand,

bottle-feeding ranges from 23 percent in Haiti to 85 percent in

the Dominican Republic. In Near East/North Africa countries,

the prevalence is intermediate, with a range of 20 to 43 percent.

The range of bottle-feeding rates is quite wide in Asia, probably

a result of the varied mix of countries in that regional grouping.

Overall, as countries move higher on the economic development

ladder, bottle-feeding rates increase, and become closer to the

rates found in developed countries.

40

60

Percent of children

80

100

Source: DHS Surveys 1990-1996

Summary

The data from 37 countries indicate that there is

substantia] divergence from the WHO recommendations for

infant feeding. Exclusive breastfeeding of infants younger than

4 months is rare in all but a few countries. In contrast, most

young infants are predominantly breastfed, i.e., given breast

milk with some other liquids. Equally troubling is the fact that

in a third of the countries studied fewer than half of children 6

to 9 months of age are receiving complementary foods, as is

recommended. At the same time, the median age at introduction

of complementary foods among children under age three years

is as young as 1,2, or 3 months in 13 of the 37 countries. Thus,

liquids and solids other than breast milk are being given to

children at very early ages, increasing the risk of diarrhea. From

the age of 6 months onward, when breast milk alone is nutrition

ally insufficient and complementary foods are needed, many

children over 6 months are not fed any solid foods, or are not

fed them on a daily basis.

There is still an urgent need to promote adequate and

safe feeding of young children. Breastfeeding patterns in the

countries

studied

J are far from optimal, with few young infants

---------------103

Definitions Used in the WHO Global Data Bank on Breastfeeding

»

Category of

infant feeding

Does not allow the infant

to receive

Allows the infant to

receive

Exclusive breastfeeding

Breast milk (including

milk expressed or from

wet nurse)

Drops, syrups (vitamins,

minerals, medicines)

Anything else

Predominant

breastfeeding

Breast milk (including

milk expressed or from

wet nurse) as the.

predominant source of

nourishment

Liquids (water, and water

based drinks, fruit juice),

oral rehydration therapy,

ritual fluids, and drops or

syrups (vitamins, minerals,

medicines)

Anything else (in

particular, nonhuman milk,

food-based fluids)

Complementary feeding

Breast milk and solid or

semisolid foods

Any food or liquid

including nonhuman milk

Breastfeeding

Breast milk

Any food or liquid

including nonhuman milk

Bottle-feeding

Any liquid or semisolid

food from a bottle with

nipple/teat

Any food or liquid

including nonhuman milk.

Also allows breast milk by

bottle

•i

I

Requires that the infant

receive

i

Source: WHO, 1996

1

kJ \-¥o

IO

f

165

OA1

£ .

'< U!!FP4

ffl oB^emves of study

..

J

K7---'

3 rr

i

A Study Commissioned by

7

.

;

• To assess Incidence of Induced

abortions In these two states.

• To assess contribution of sex linked r

abortions in total Induced abortions.

• To understand Imnact of inriiinefi

abortions and sex linked abortions on

Total Fertility Rate.

UNFPA

METHODOLOGY

■

• Indirect estimates.

• Large scale data sets used Le.NFHS I and II

andSRS.

• Proximate variable model used for

Decomposition of total fertility.

•. Index of sex discrimination at birth

calculated on the basis of deficit in

number of girls at birth, expected ratio

being 100/106.

%

Table 1: Total Induced Abortions

Per 100 Live Births

(1992-1998J

Haryana

Punjab

Urtaa

Total

Rural

Urtsu

Total

14.7

30.9

17.9

19J

44.9

262

199? IT

112

Ml

Ilf

165

1992

nr

Table 3: Impact of SSA on TFR

j

Table 2: Ratio of Sex- selective Abortions to

Total Induced Abortions (in Percentage)

(1992-1998).

Haryana

;

Punlaii

Total

Total

18.1

112

69.9

57J

35J

455

W90 712

671

oiT

lol

19J

nT

1992

Punjab

Haryana

Brttaa Total

OT

Roral

Ortna

Total

Rural

1992

442

3.14

llT

109

240

1991

3.13

218

225

242

TFR in Case No. Sex Sex selective abortions

4.71

1992

328

4J2

3.31

Tro"

2.69

114

2jf

103

Im

1991

m

nr

251

2J2

m

Percentage Increase in TFR, had there been no sex selective abortions

9.1

1392

12

11

72

15

15

1991

8.7

22J

lol

6J

124

~15

'•

~

■

w

■'

3

■ w

POUCy IMPLICATIONS

&

j^UJIFRa

- Value of girl child

- Dowry as social evil

- Consequence of declining sex ratio

on family formation patterns

- Commercialization of sex

'■

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

rwww r»3

1 Advocacy on Issues related to:

.

-

2 Legal framo work:

- Expand scope of PNDT act to include other

methods of pre-selection of sex.

- Ensure effective implementation of MTP

and PNDT Act

3 Improve service delivery for safe

abortion

POLICY IMPLICATIONS....

Contd

■■

4 Research:

- Demographic Impact

-Bata Collection Methodologies on

Abortions

- Changing Patterns in Method Mix and Its

impact on TFR

- In-depth studies

on socio-cultural

determinants of SSA

2

Position: 1465 (5 views)