9600.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

J

M(?Jv CYjSOS'to'YTb

Penguin Education

-

3 cincjci toy(^

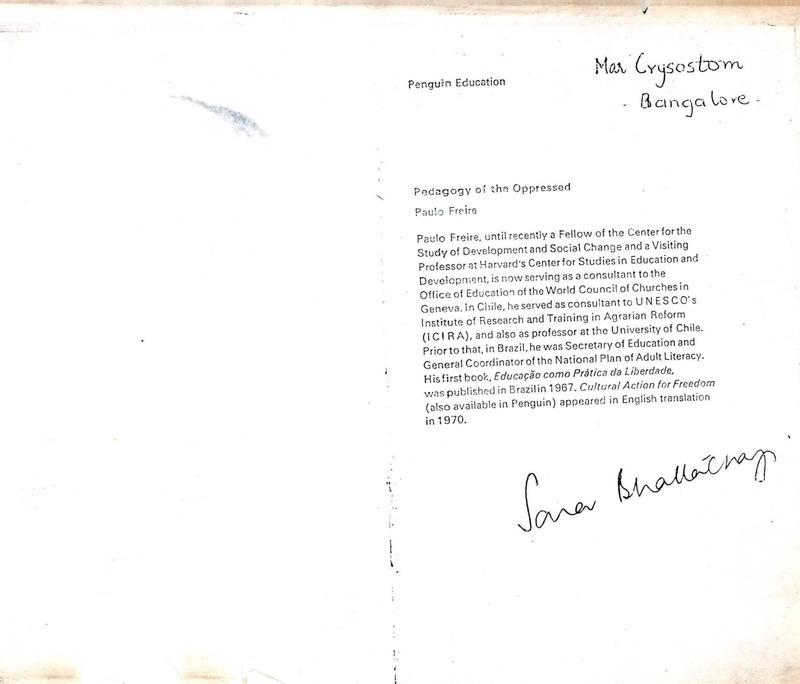

Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Paulo Freire

Paulo Freire, until recently a Fellow of the Center for the

Study of Development and Social Change and a Visiting

Professor at Harvard's Center for Studies in Education an j

Development, is now serving as a consultant to the

Office of Education of the World Council of Churches in

Geneva In Chile, he served as consultant to U N E S C 0 s

Institute of Research and Training in Agrarian Reform

(I Cl R A), and also as professor at the University of Chde.

Prior to that, in Brazil, he was Secretary of Education and

General Coordinator of the National Plan of Adult Literacy.

Hisfirst book, EducafSo como Pratica da Liberdade

wns published in Brazilin 1967. Cultural Action for Freedom

i

(also available in Penguin) appeared in English translate

in 1970.

b

I •

f.

r—

08600

I

i

■

■

Ii

Pedagogy

of the Oppressed

Paulo Freire

Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos

Penguin Educ-ation

!

I

1

I

1

I

Contents

r ■''

<<

v-‘''

Foreword by Richard Shaul! 9

Preface 15

Chapter 1 20

The justification for a pedagogy of the oppressed; the

contradiction between the oppressors and the oppressed, and

how it is overcome; oppression and the oppressors; oppression

and the oppressed; liberation: as a mutual process.

Chapter 2 45

I

The 'banking' concept of education as an instrument of

oppression; the problem-posing concept of education as an

instrument for liberation ; the teacher-student contradiction of the

'banking' concept superseded by the problem-posing concept,

education as a world-mediated mutual process; man as a

consciously incomplete being, and his attempt to be more fully

human.

i

li

I

r

Chapter 3 60

Dialogics: the essence of education as the practice of freedom;

dialogics and dialogue; dialogue and the search for programme

content; the men-world relationship, 'generative themes’, and

the programme content of education as the practice of freedom;

the investigation of 'generative themes' and its methodology;

the awakening of critical consciousness through the investigation

of 'generative themes'.

?

i

i

>:

I

-

I

I

!

Chap

Ar fir

I

ed ra

the latt

ar‘:dia

rd

rr

aCut-zn

Penguin Education

To the oppressed,

A Division of Penguin Books Ltd,

Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd,

Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

and to those who suffer with them

and fight at their side

^and cl

R

'

<’•

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd,

1 82-1 90 Wairau Road, Auckland 10,

New Zealand

■K

Firsi published in Great Britain by Sheed & Ward 1972

Published by Penguin Books 1972

Reprinted 1973, 1974

Copyright© Paulo Freire, 1972

Made and printed in Great Britain oy

C. Nicholls & Company Ltd

I?

Set in Monotype Times

This book is sold subject to the condition that

it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without

the publisher's prior consent in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is

published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on the

subsequent purchaser

I

V

t

0980Q

too

■

sr

■i

i

I

Foreword

Chapter 4 96

Antidialogics and dialogics as matrices of opposing theories of

cultural action: the former as an instrument of oppression and

the latter as an instrument of liberation; the theory of

antidialogical action and its characteristics: conquest, divide and

rule, manipulation, and cultural invasion; the theory of dialogical

action and its characteristics: cooperation unity, organization,

and cultural synthesis.

I

!

-

References 153

I

In the course of a few years, the thought and work of the

Brazilian educator Paulo Freire have spread from the North

East of Brazil to an entire continent, and have made a profound

impact not only in the field of education but also in the overall

struggle for national development. At the precise moment

when the disinherited masses in Latin America are awakening

from their traditional lethargy and are anxious to participate,

as subjects, in the development of their countries, Paulo Freire

has perfected a method for teaching illiterates that has contri

buted, in an extraordinary way, to that process. In 'act, those

who, in learning to read and write, come to a new awareness of

selfhood and begin to look critically at the social situation in

j

■

>■

i

■ i--

i

!

i

I

I

"which they find themselves, often take the initiative in acting to

transform the society that has denied them this opportunity of

participation. Education is once again a subversive force.

In the United States, we are gradually becoming aware of the

work of Paulo Freire, but thus far we have thought of it

primarily in terms of its contribution to the education of illiter

ate adults in the Third World. If, however, we take a closer

look, we may discover that his methodology as well as his

educational philosophy are as important for us as for the dis

possessed in Latin America. Their s[niggle to become frce_

subjects and to participate in the transformation of their_society__

is similar, in many ways, to the stmggle not only of blacks and

Mexican-Americans, but also of middle-class young people.

And the sharpness and intensity of that struggle in the develop

ing world may well provide us with new insight, new models,

and a new hope as we face our own situation. For this reason

I consider the publication of Pedagogy of the Oppressed in an

English edition to be something of an event.

Paulo Freire’s thought represents the response of a creative

mind and sensitive conscience to the extraordinary misery jmd

K

i

II

i ■■

I

i

11

10

i

J

suffering of the oppressed, around him. Born in 1921 in Recife^

the centre of one of the most extreme situations of poverty and

underdevelopment in the Third World, he was soon forced to

experience that reality directly. As the economic crisis in 1929

in the United States began to affect Brazil, the precarious stab

ility of Freire’s middle-class family gave way and he found

himself sharing the plight of the ‘wretched of the earth’. This

had a profound influence on his life as he came to know the

gnawing pangs of hunger and fell behind in school because of

the listlessness it produced; it also led him to make a vow, at

the age of eleven, to dedicate his life to the struggle against_

hunger, so that other children would not have to know the

agony he was then experiencing.

His early sharing of the life of the poor also led him to the

discovery of what he describes as the ^culture of silence’ of the

dispossessed. He came to realize that their ignorance and leth

argy were the direct product of the whole situation of economic,

social, and political domination - and of the paternalism - of

which they were victims. Rather than being encouraged and

equipped to know and respond to the concrete realities of their

world, they were kept ‘submerged’ in a situation in which such

critical awareness and response were practically impossible.

And it became clear to him that the whole educational system

was one of the major instruments for the maintenance of this

culture of silence.

Confronted by this problem in a very existential way, Freirc

turned his attention to the field of education and began to work

on it. Over the years he has engaged in a process of study and

reflection that has produced something quite new and creative

in educational philosophy. From a situation of direct engage

ment in the struggle to liberate men and women for the creation

of a new world, he has reached out to the thought and experi

ence of those in many different situations and of diverse philo

sophical positions: in his words, to ‘Sartre and Mounier, Eric

Fromm and Louis Althusser, Ortega y Gasset and Mao, Martin

Luther King and Che Guevara, Unamuno and Marcuse*. He

has made use of the insights of these men to develop a pers

pective on education which is authentically his own and which

seeks to respond to the concrete realities of Latin America

•J •

!■

fI

r

His thought on the philosophy of education was first expressed in 1959 in his doctorardissertation aFthe University

of Recife, and later in his work as Professor of the History and

Philosophy of Education in the same university, as well as in

his early experiments with the teaching of illiterates in that same

city. The methodology he developed was widely used by

Catholics and others in literacy campaigns throughout the

North East of Brazil, and was considered such a threat to the

old order that Freirc was jailed immediately after the military

coup in 1964. Released seventy days later and encouraged to

leave the country, Freirc went to Chile, where he spent five

years working with UNESCO and the Chilean Institute for

Agrarian Reform in programmes of adult education. He then

acted as consultant at Harvard University’s School of Educa

tion, and worked in close association with a number of groups

engaged in new educational experiments in rural and urban

areas. He is presently serving as Special Consultant to the Office

of Education of the World Council of Churches in Geneva.

Frei re has written many articles in Portuguese and Spanish,

and his first book, Educa^ao como Prdtica da Liberdade, was

published in Brazil in 1967. His latest and most complete work,

Pedagogy of the Oppressed, is the first of his writings to be

published in the United States.

In this brief introduction, there is no point in attempting

to sum up, in a few paragraphs, what the author develops in a

number of pages. That would be an oflence to the richness,

depth, and complexity of his thought. But perhaps a word o£

witness has its place here - a personal witness as to why I find

a dialogue with the thought of Paulo Freirc an exciting ad

venture. Fed up as Lam with the abstractness and sterility of

so much intellectual work in academic circles today, I am cxcltcTTy a process of reflection which is set in a thoroughly

historical context, which is carried on in the midst of a struggle

to create a new social order and thus represents a new unity of

theory and praxis. And 1 am encouraged when a man of the

stature of Paulo Freire incarnates a rediscovery of thejwmanizing vocation of the intellectual, and demonstrates the power

of thought to negate accepted limits and open the way to a new

future.

12

13

Freire is able to do this because he operates on one basic

assumption: that man’s ontological vocation (as he calls it) is

t2-b?.ASMwho acts upoh and transforms lus xyor^and

in, ^Ljojogjupyes towards ever new possibilities of fuller and

richer life individua]Hy_and collectiyejy^TTiis ‘world’ to whiS

he relates is not a static and closed order, a given reality which

J

man must accept and to which he must adjust; rather, it is a

problem to be worked on and solved. It is the material used by

man to create history, a task which he performs as he overcomes

th-at ^jehj^dehumanizing at any particular time and place

and dares to create the qualitatively new. For Freire, the re

sources for that task at the present time are provided by the

advanced technology of our Western world, but the social

vision which impels us to negate the present order and demon

i

strate that history has not ended comes primarily from the

suffering and struggle of the people of the Third World.

Coupled with this is Freire’s conviction (now supported by

a wide background of experience) that every human being, nq

matter how ‘ignorant or submerged in the ‘cuIture^qf sifeacc/

he may Te, is capable, of Joo king.j:riucallz at his world Jn..a_

dialogical cn

c cgunter whh_^others.' Provided with the proper

tools for ----such1 an encounter, he can gnidually perc.Qiv£L_his

personal and social realityj as

contradictions in

as well

well as

as the

the contradictions

in it,

it,

become conscious of his own perception of that reality, and

ii

deal critically with it. In this process, the old, paternalistic

teacher - student relationship is overcome. A peasant can

J

^acilitate this process tor his neighbour more effectively than a

teacher brought in from outside. ‘Men educate each other

through the mediation of the world.’

As this happens, the word takes on new power. It is no longer

fe:an abstraction or magic but a means by which man discovers

imsclf and his potential as he gives names to things around

tim. As Freire puts it, each man wins back his right to say his

' own word, to name the world.

When an illiterate peasant participates in this sort of educa

■

tional experience, he comes to a new awareness of self, has a

new sense of dignity, and is stirred by a nevkhope. Time and

a8ain, peasants have expressed these discoveries in striking

ways after a few hours ol class: T now realize I am a man, an

i

E

IK

I-

educated man.’ ‘We were blind, now our eyes have been

opened.’ ‘Before this, words meant nothing to me; now they

speak to me and I can make them speak.’ ‘Now we will no

longer be a dead weight on the cooperative farm.’ When this

happens in the process of learning to read, men discover that

they are creators of culture,, and that all their work can be

creative. ‘I work, and_worXingJLtransform the world.’ And as

those who have been completely marginalized are so radically

transformed, they are no longer willing to be mere objects,

responding to changes occurring around them; they are more

likely to decide to take upon themselves the struggle to change

the structures of society which until now have served to oppress

them. For this reason, a distinguished Brazilian student of

national development recently affirmed that this type of educa

tional work among the people represents a new factor in social

change and development, ‘a new instrument of conduct for the

Third World, by which it can overcome traditional structures

and enter the modern world’.

At first sight Paulo Freire’s method of teaching illiterates in

Latin America seems to belong to a different world from that in

which we find ourselves. Certainly it would be absurd to claim

that it should be copied here. But there are certain parallels

in the two situations which should not be overlooked. Our

advanced technological society is rapidly making objects of most

of us and subtly programming us into conformity to the logic

of its system. To the degree that this happens, we are also be

coming submerged in a new ‘culture of silence’.

The paradox is that the same technology which does this to

us also creates a new sensitivity to what is happening. Especially

among young people, the new media together with the erosion

of old concepts of authority open the way to acute awareness

of this new bondage. The young perceive that their right to

say their own word has been stolen from them, and that few

thifigT are more important than the struggle to win it back.

And they also realize thaFtHeeducational system today - from

kindergarten to university - is their enemy.

There is no such thing as a neutral educational process.

Education cither functions as an instrument which is used to

facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the

i

t

II

il ;

14

r;

■

■

I

i

it

ii

it h °^!^e Prcsent system and bring about conformity to it or

\he praclicc

freedom', the means by which men

covTrT6"

Cr,.t,Cally and creatively with reality and^:

Thp h °7 t0 part,c,pate ,n

transformation of their world,

thic 676 Opment of an educational methodology that facilitates

our Pr0CeSS

inevitably lead to tension and conflict within

ty* But jt C01J,d a,so contribute to the formation of a

new man and mark the beginning of a new era in Western

history. For those who

are committed to that task and are

searching for cc

concepts and tools for experimentation, Paulo

Freire’s thought

’*.t may make a significant contribution in the

years ahead.

Preface

Richard Shaull

i

ff

1

!!•

I I-

These introductory pages to Pedagogy of the Oppressed are the

result of my observations during the last six years of political

exile, observations which have enriched those previously

afforded by my educational activities in Brazil.

I have encountered, both in training courses which analyse

the role of ‘conscientization’1 and in actual experimentation

with a genuinely liberating education, the ‘fear of freedom’

discussed in the first chapter of this book. Not infrequently,

training course participants call attention to ‘the danger of

“conscientization ”’ in a way which reveals their own fear of

freedom. Critical consciousness, they say, is anarchic; others

add that critical consciousness may lead to disorder. But some '

confess: Why deny it? I was afraid of freedom. I am no longer

afraid!

In one of these discussions, the group was debating whether

the conscientization of men to a specific case of injustice might

not lead them to ‘destructive fanaticism’ or to a ‘sensation of

total collapse of their world’. In the midst of the argument a

man who previously had been a factory worker for many years

spoke out: ‘Perhaps I am the only one here of working-class

origin. I can’t say that I’ve understood everything you’ve said

just now, but I can say one thing - when I began this course I

was naive, and when I found out how naive I was, 1 started to

get critical. But this discovery hasn’t made me a fanatic, and

I don’t feel any collapse either.’

Doubt regarding the possible effects of conscientization

implies a premise which the doubter does not always make

explicit: Itjs better for the victims of injustice not to recognize

themselves as such. In fact, conscientization does not lead men

I. The term ‘conscientization’ refers to learning to perceive social,

political, and economic contradictions, and to take action against the

oppressive elements of reality. See chapter 3. (Translator's note.')

1

i

17

16

i

to ‘destructive fanaticism’. On the contrary, by making it

possible for men to enter the historical process as responsible

subjects,2 conscientization enrolls them in the search for selfaffirmation, thus avoiding fanaticism.

The awakening of critical consciousness leads the way to the expres

sion of social discontents precisely because these discontents are real

components of an oppressive situation.3

i

Fear of freedom, of which its possessor is not necessarily

aware, makes him see ghosts. Such an individual is actually

taking refuge in an attempt to achieve security, which he prefers

to the risks of liberty. As Hegel testifies in The Phenomenology of

Mind\

It is solely by risking life that freedom is obtained; . .. the individual

who has not staked his life may, no doubt, be recognized as a Person;

but he has not attained the truth of this recognition as an independent

self-consciousness.

I

1i

Men rarely admit their fear of freedom openly, however, tend-,

ing rather to camouflage it - sometimes unconsciously - by

presenting themselves as defenders of freedom. They give their

doubts and misgivings an air of profound sobriety, as befitting

custodians of freedom. But they confuse freedom with the

maintenance of the status quo\ so that if conscientization

threatens to place that status quo in question, it thereby seems

to constitute a threat to freedom itself.

Thought and study alone did not produce Pedagogy of the

Oppressed} it is rooted in concrete situations and describes the

reactions of workers (peasant or urban) and of the members of the

middle-class whom I have observed directly or indirectly during

the course of my educative work. Continued observation will

give me an opportunity to modify or to corroborate in later

studies the points put forward in this introductory work.

This volume will probably arouse negative reactions in a

number of readers. Some will regard my position vis-a-vis

the problem of human liberation as purely idealistic, or may

2. The term ‘Subjects’ denotes those who know and act, in contrast

to ‘objects’, which arc known and acted upon.(Tru'islalor'snote.')

3. Francisco WetTert, in the preface to my Educa^do cotno Prddica da

Liber dade.

i

5

I-

s

even consider discussion of ontological vocation, love, dialogue,

hope, humility, and sympathy as so much reactionary ‘blah’.

Others will not (or will not wish to) accept my denunciation of ' .

a state of oppression which gratifies the oppressors. Accord

ingly, this admittedly tentative work is for radicals. lam certain

that Christians and Marxists, though they may disagree with

me in part or in whole, will continue reading to the end. But

the reader who dogmatically assumes closed ‘irrational’ posi

tions will reject the dialogue I hope this book will open.

Sectarianism, fed by fanaticism, is always castrating. Radical

ization, nourished by a critical spirit, is always creative. Sec

tarianism makes myths and thereby alienates; radicalization

is critical and thereby liberates. Radicalization involves in

creased commitment to the position one has chosen, and thus

ever greater engagement in the effort to transform concrete,

objective reality. Conversely, sectarianism, because it is myth

making and irrational, turns reality into a false (and therefore

unchangeable) ‘reality’.

Sectarianism in any quarter is an obstacle to the emancipa

tion of mankind. The Rightist version thereof does not always,

unfortunately, cal! forth its natural counterpart: radicalization

of the revolutionary. Not infrequently, revolutionaries them

selves become reactionary by falling into sectarianism in the

process of responding to the sectarianism of the Right. This

possibility, however, should not lead the radical to become a

docile pawn of the elites. Engaged in the process of liberation,

he cannot remain passive in the lace of the oppressor s violence.

On the other hand, the radical is never a subjectivist. For him

the subjective aspect exists only in relation to the objective

aspect (the concrete reality which is the object of his analysis).

Subjectivity and objectivity thus join in a dialectical unity

producing knowledge in solidarity with action, and vice versa.

For his part, the sectarian of whatever persuasion, blinded

by his irrationality, docs not (or cannot) perceive the dynamic

of reality - or else he misinterprets it. Should he think dialectic

ally, it is with a ‘domesticated dialectic’. The Rightist sectarian

whom I have earlier, in Educa^do como Prdtica da Liberdade,

termed a ‘born sectarian’) wants to slow down the historical

process, to ‘domesticate’ time and thus to domesticate men.

1

' al

•<

i1

I- i?

I

*

j

H

I!

■

I

ih

h

i

.I

18

The Leftist-turned-sectarian goes totally astray when he

attemptsjo interpret reality and history dialectically, and falls

into essentially fatalistic positions.

The Rightist sectarian differs from his Leftist counterpart in

that the former attempts to domesticate the present so that (he

hopes) the future will reproduce this domesticated present,

while the latter considers the future pre-established - a kind of

inevitable fate, fortune, or destiny. For the Rightist sectarian,

‘today’, linked to the past, is something given and immutable;

for the Leftist sectarian, ‘tomorrow’ is decreed beforehand, is

inexorably pre-ordained. This Rightist and this Leftist are both

reactionary because, starting from their respective false views

of history, both develop forms of action which negate freedom.

The fact that one man imagines a ‘well-behaved’ present and

the other a predetermined future does not mean that they

therefore fold their arms and become spectators (the former

expecting that the present will continue, the latter waiting for

the already ‘known’ future to come to pass). On the contrary,

closing themselves into ‘circles of certainty’ from which they

cannot escape, these men ‘make’ their own truth. It is not the

truth of men who struggle to build the future, running the risks

involved in this very construction. Nor is it the truth of men

who fight side by side and learn together how to build this

future - which is not something given to be received by men,

but is rather something to be created by them. Both types of

sectarian, treating history in an equally proprietary fashion,

end up without the people - which is another way of being

against them.

While the Rightist sectarian, closing himself in ‘his’ truth,

does no more than fulfil his natural role, the Leftist who

becomes sectarian and rigid negates his very nature. Each,

however, as he revolves about ‘his’ truth, feels threatened

if that truth is questioned. Thus, each considers anything that

is not ‘his’ truth a lie. As the journalist Marcio Moreira Alves

once told me: ‘They both suffer from an absence of doubt, ’

The radical, committed to human liberation, docs not

become the prisoner of a ‘circle of certainty’ within which

he also imprisons reality. On the contrary, the more radical

he is, the more fully he enters into reality so that, knowing

19

it better, he can better transfdrm it. He is not afraid to confront,

to listen, to see the world unveiled. He is not afraid to meet

the people or to enter into dialogue with them.4 He does not

consider himself the proprietor of history or of men, or the

liberator of the oppressed; but he does commit himself,

within history, to fight at their side.

The pedagogy of the oppressed, the introductory outlines !

of which are presented in the following pages, is a task for

radicals; it cannot be carried out by sectarians.

I will be satisfied if among the readers of this work there

are those sufficiently critical to correct mistakes and mis

understandings, to deepen affirmations and to point out

aspects I have not perceived. It is possible that some may

question my right to discuss revolutionary cultural action,

a subject of which I have no concrete experience. However,

the fact that I have not personally participated in revolu

tionary action does not disqualify me from reflecting on this*

theme. Furthermore, in my experience as an educator with the

people, usjng a dialogical and problem-posing education, 1 have

accumulated a comparative wealth of material which challenged

me to run the risk of making the affirmations contained in this

work.

From these pages I hope at least the following will endure:

my trust in the people, and my faith in men and in the creation

of a world in which it will be easier to love.

Here I would like to express my gratitude to Elza, my wife

and ‘first reader', for the understanding and encouragement

she has shown my work, which belongs to her as well. I would

also like to extend my thanks to a group of friends for their

comments on my manuscript. At the risk of omitting some

names, I must mention Joao da Veiga Coutinho, Richard

Shaull, Jim Lamb, Myra and Jovelino Ramos, Paulo de Tarso,

Almino Affonso, Plinio Sampaio, Ernani Maria Fiori, Marcela

Gajardo, Jose Luis Fiori, and Joao Zacarioti. The responsibility

for the affirmations made herein is, of course, mine alone.

I

i

i

I

J

it

■

I

t

4. ‘As long as theoretic knowledge remains the privilege of a handful

of “academicians” in the Party, the latter will face the danger of going

astray,’ writes Rosa Luxembourg in Reform or Revolution, cited in

C. Wright Mills, The Marxists.

4

21

Chapter 1

While the problem of humanization has always been, from an

axmlogicali point of view, man’s central problem, it now takes

on the character of an inescapable concern^ Concern for

humantzabon leads at once to the recognition of dehumaniza

tion. not only as an ontological possibility but as an historical

reahty. And as man perceives the extent of dehumanization,

he asks himself if humanization is a viable possibility. Within

history, m concrete, objective contexts, both humanization

and dehumamzation are possibilities for man as an uncom

pleted being conscious o f his incompleteness.

But while both humanization and dehumanization are

real alternatives, only the first is man’s vocation. This vocation

is constantly negated, yet it is affirmed by that very negation.

It is thwarted by injustice, exploitation, oppression, and the

violence of the oppressors; it is affirmed by the yearning of the

oppressed for freedom and justice, and by their struggle to

recover their lost humanity.

Dehumanization, which marks not only those whose

humanity has been stolen, but also (though in a different way)

t ose who have stolen it, is a distortion of the vocation of

1. An axiological viewpoint is one which involves the ethical, aesthetic

and religious.

2. The current movements of rebellion, especially those of youth, while

they necessarily reflect the peculiarities of their respective settings, mani.ht ln

ejSSence thls Preoccupalion with man and men as beings in

.

?nd Wlth lhC W°rld ~ a PreoccuPafion with what and how they

-d? r ■ 'U,S r

thCy PlaCC consurn€r civilization in judgement, denounce

•

ypcs o ureaucracy, demand the transformation of the universities

t i.mgxng the rigid nature ofthe teacher - student relationship and placing

•hal refcmonsh.p wHhin the context of reality), propose the transform^

Hon o. reahty itself so that universities can be renewed, attack old orders

« nd established institutions in the attempt to affirm men as the subjects

decrsion, all these movements reflect the style of our age, which is

more anthropological than anthr<»|x>ccnlric.

!

becoming more fully human. This distortion occurs within

history; but it is not an historical vocation. Indeed, to accept

dehumanization as an historical vocation would lead either to

cynicism or total despair. The struggle for humanization,

for the emancipation of labour, for the overcoming of aliena

tion, for the affirmation of men as persons would be meaning

less. This struggle is possible only because dehumanization,

although a concrete historical fact, is not a given destiny but

the result of an unjust order that engenders violence in the

oppressors, which in turn dehumanizes the oppressed.

Because it is a distortion_of being more fully human, sooner

or later being less human leads the oppressed to struggle against

those who made them so. In order for this struggle to have

meaning, the oppressed must not, in seeking to regain their "-i

humanity (which is a way to create it), become in turn oppres

sors of the oppressors, but rather restorers of the humanity of

both.

This, then, is the great humanistic and historical task of the

oppressed: to liberate themselves and their oppressors as well.

The oppressors, who oppress, exploit, and rape by virtue of

their power, cannot find in this power the strength to liberate

either the oppressed or themselves. Only power that springs

from the weakness of the oppressed will be sufficiently strong

to free both. Any attempt to ‘soften’ the power of the oppressor

in deference to the weakness of the oppressed almost always

manifests itself in the form of false generosity; indeed, the

lit tempt never goes beyond this. In order to have the continued

opportunity to express their ‘generosity’, the oppressors must

perpetuate injustice as well. An unjust social order is the

permanent fount of this ‘generosity’, which is nourished by

death, despair, and poverty. That is why its dispensers become

desperate at the slightest threat to the source of that false

generosity.

True generosity consists precisely in fighting to destroy

the causes which nourish false charity. False charity constrains

the fearful and subdued, the ‘rejects of life’, to extend their

trembling hands. Real generosity lies in striving so that those

hands - whether of individuals or entire peoples - need be

extended less and less in supplication, so that more and more

r

f

4L

■

i

a

I

1

22

they become human hands which work and, by working,

transform the world.

This lesson and apprenticeship must come, however, from

the oppressed themselves and from those who are truly with

them. By fighting for the restoration of their humanity, as

individuals or as peoples, they will be attempting the restoration

of true generosity. Who are better prepared than the oppressed

to understand the terrible significance of an oppressive society?

Who suffer the effects of oppression more than the oppressed?

Who can better understand the necessity of liberation? It will

not be defined by chance but through the praxis of their

quest for it, through recognizing the necessity to fight for it.

And this fight, because of the purpose given it by the oppressed,

will actually constitute an act of love opposing the lovelcssness

which lies at the heart of the oppressors' violence, lovelessness

even when clothed in false generosity.

But almost always, during the initial stage of the struggle,

the oppressed, instead of striving for liberation, tend themselves

to become oppressors, or ‘sub-oppressors’. The very structure

of their thought has been conditioned by the contradictions

of the concrete, existential situation by which they were shaped.

Their ideal is to be men; but for them, to be a ‘man’ is to be

an oppressor. This is their model of humanity. This pheno

menon derives from the fact that the oppressed, at a certain

moment of their existential experience, adopt an attitude of

‘adherence’ to the oppressor. Under these circumstances they

cannot ‘consider’ him sufficiently clearly to objectify him - to

discover him ‘outside’ themselves. This does not necessarily

mean that the oppressed are not aware that they are down

trodden. But their perception of themselves as oppressed is

impaired by their submersion in the reality of oppression. At this

level, their perception of themselves as opposites of the

oppressor docs not yet signify involvement in a struggle to

overcome the contradiction;3 the one pole aspires not to

liberation, but to identification with its opposite pole.

In this situation the oppressed cannot see the ‘new man’

as the man to be born from the resolution of this contradiction,

3- As used throughout this book, the term ‘contradiction’ denotes the

dialectical conflict between opposing social forces. {Translator's note.)

23

in the process of oppression giving way to liberation. For

them, the new man is themselves become oppressors. Their

vision oCthe new man is individualistic; because of their

identification with the oppressor, they have no consciousness

of themselves as persons or as members of an oppressed class.

It is not to become free men that they want agrarian reform,

but in order to acquire land and thus become landowners - or,

more precisely, bosses over other workers. It is a rare peasant

who, once ‘promoted’ to overseer, does not become more

of a tyrant towards his former comrades than the owner

himself. This is because the context of the peasant’s situation,

that is, oppression, remains unchanged. In this example,

the overseer, in order to make sure of his job, must be as tough

as the owner - and more so. This illustrates our previous

assertion that during the initial stage of their struggle the

oppressed find in the oppressor their model of‘manhood’.

Even revolution, which transforms a concrete situation

of oppression by establishing the process of liberation, must

confront this phenomenon. Many of the oppressed who

directly or indirectly participate in revolution intend - con

ditioned by the myths of the old order - to make it their private

revolution. The shadow of their former oppressor is still cast

over them.

The ‘fear of freedom’ which afflicts the oppressed,4 a fear

which may equally well lead them to desire the role of oppressor

or bind them to the role of oppressed, should be examined.

One of the basic elements of the relationship between oppressor

and oppressed is prescription. Every prescription represents the

imposition of one man’s choice uponLanother,Transforming the

consciousness of the man prescribed to.LntQ_QneJha£conforms

to the prescriber's consciousness. Thus, the behaviour of the

oppressed is a prescribed behaviour, following as it docs the

guidelines of the oppressor.

The oppressed, having internalized the image of the oppressor

and adopted his guidelines, are fearful of freedom. Freedom..

would require them to eject this image and replace it with

4. This fear of freedom is also to be found in the oppressors, though,

obviously, in a different form. The oppressed are afraid to embrace

freedom; the oppressors arc afraid of losing the ‘ freedom ’ to oppress.

7.

24

I.

autonomy and responsibility. Freedom is acquired by conquest,

not by gift. It must be pursued constantly and responsibly.

Freedom is not an ideal located outside of man; nor is it an

idea which becomes myth. It is rather the indispensable

condition for the quest for human completion.

To surmount the situation of oppression, men must first

critically recognize its causes, so that through transforming

action they can create a new situation - one which makes

possible the pursuit of a fuller humanity. But the struggle

to be more fully human has already begun in the authentic

struggle to transform the situation. Although the situation

of oppression is a dehumanized and dehumanizing totality

affecting both the oppressors and those whom they oppress,

it is the latter who must, from their stifled humanity, wage

for both the struggle for a fuller humanity; the oppressor,

who is himself dehumanized because he dehumanizes others,

is unable to lead this struggle.

However, the oppressed, who have adapted to the structure

of domination in which they are immersed, and have become

resigned to it, are inhibited from waging the struggle for

freedom so long as they feel incapable of running the risks it

requires. Moreover, their struggle for freedom threatens not

only the oppressor, but also their own oppressed comrades

who are fearful of still greater repression. When they discover

within themselves the yearning to be free, they perceive that

this yearning can be transformed into reality only when the

same yearning is aroused in their comrades. But while domin

ated by the fear of freedom they refuse to appeal to, or listen

to the appeals of, others, or even to the appeals of their own

conscience. They prefer gregariousness to authentic comrade

ship; they prefer the security of conformity with their state of

unfreedom to the creative communion produced by freedom

and even the very pursuit of freedom.

The oppressed suffer from the duality which has established

itself in their innermost being. They discover that without

freedom they cannot exist authentically. Yet, although they

desire authentic existence, (hey fear it. They arc at one and the

same time themselves and the oppressor whose consciousness

they have internalized. The conflict lies in the choice between

25

-

I

being wholly themselves or being divided; between ejecting the

oppressor within or not ejecting him; between human solidarity

or alienation; between following prescriptions or having

choices; between being spectators or actors; between acting

or having the illusion of acting through the action of the

oppressors; between speaking out or being silent, castrated in

their power to create and recreate, in their power to transform

the world. This is the tragic dilemma of the oppressed which

their education must take into account.

This book will present some aspects of what the writer

has termed the ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’, a pedagogy which

must be forged with, not for. the oppressed (be they individuals

or whole peoples) in the incessant struggle to regain their

humanity. This pedagogy makes oppression and its causes

objects of reflection by the oppressed, and from that reflection

will come their necessary engagement in the struggle for their

• liberation. And in the struggle this pedagogy will be made and

remade.

The central problem is this: How can the oppressed, as

divided, unauthentic beings, participate in developing the

pedagogy of their liberation? Only as they discover themselves

to be ‘hosts’ of the oppressor can they contribute to the

midwifery of their liberating pedagogy. As long as they live

in the duality where to be is to be like, and to be like is to be

like the oppressor, this contribution is impossible. The pedagogy

of the oppressed is an instrument for their critical discovery that

both they and their oppressors are manifestations of dehumaniLiberation is thus a childbirth, and a painful one. The man

who emerges is a new man, viable only as the oppressoroppressed contradiction is' superceded by the humanization

of all men. Or to put it another way, the solution of this

contradiction is born in the labour which brings this new man

into the world: no longer oppressor or oppressed, but man in

the process of achieving freedom.

This solution cannot be achieved in idealistic terms. In

order for the oppressed to be able to wage the struggle for

their liberation, they must perceive the reality of oppression,

not as a closed world from which there is no exit, but as a

?

■

I

li

* •»«.

i

26

I-

I

—

II

Ui

«.‘H

1

I®

q

s

•<<-

r;

i

I

I

y|

I

mW

Ji'

I

-

IJ,

I

limiting situation which they can transform. This perception

is necessary, but not a sufficient condition by itself for libera

tion; FTmust become the motivatingTorceTbr iWcraTingTicrionr"

Neither does the discovery by the oppressed that they exist

in dialectical relationship as antithesis to the oppressor who

could not exist without them (see Hegel’s The Phenomenology

of Mind) in itself constitute liberation. The oppressed can

overcome the contradiction in which they are caught only when

this perception enlists them in the struggle to free themselves.

The same is true with respect to the individual oppressor

as a person. Discovering himself to be an oppressor may cause

considerable anguish, but it does not necessarily lead to

solidarity with the oppressed. Rationalizing his guilt through

paternalistic treatment of the oppressed, all the while holding

them fast in a position of dependence, will not do. Solidarity

requires that one enter into the situation of those with whom

one is identifying; it is a radical posture. If what characterizes

the oppressed is their subordination to the consciousness of the

master, as Hegel affirms,5 true solidarity with the oppressed

means fighting at their side to transform the objective reality

which has made them these ‘beings for another’. The oppressor

shows solidarity with the oppressed only when he stops regarding

the oppressed as an abstract category and sees them as persons

who have been unjustly dealt with, deprived of their voice,

cheated in the sale of their labour - when he stops making

pious, sentimental, and individualistic gestures and risks an

act of Jove. True solidarity is found only in the plenitude of

this act of love, in its existcntiality, in its praxis. It is a farce

to affirm that men are people and thus should be free, yet to do

nothing tangible to make tlifs aTTirmation a reality.

Since it is in a concrete situation- that the oppressoroppressed contradiction is established, the resolution of this

contradiction must be objectively verifiable. Hence, for radicals

- both for the man who discovers himself to be an oppressor

5. Analysing (he dialectical relationship between the consciousness of

the master and the consciousness of the oppressed, Hegel, in the same

book, states: ‘The one is independent, and its essential nature is to be for

itself; the other is dependent, and its essence is life or existence for another.

The former is the Master, or Lord, the latter the Bondsman.’

27

and for the oppressed - the concrete situation which begets

oppression must be transformed.

—present this radical demand for the objective transformation of reality, to combat subjectivist immobility which

would divert the recognition of oppression into patient waiting

for oppression to disappear by itself, is not to dismiss the role

of subjectivity in the struggle to change structures. On the

contrary, one cannot conceive of objectivity without sub

jectivity/Neither can exist without the other, nor can they be

dichotomized. The separation of objectivity from subjectivity,

the denial of the latter when analysing reality or acting upon it,

is objectivism. On the other hand, the denial of objectivity in

analysis or action, resulting in a subjectivism which leads to

solipsistic positions, denies action itself by denying objective

reality. Neither objectivism nor subjectivism, nor yet psy

chologism is propounded here, but rather subjectivity and

objectivity in constant dialectical relationship.

To deny the importance of subjectivity in the process of

transforming the world and history is naive and simplistic.

It is to admit the impossible: a world without men. Thisobjectivistic position is as ingenuous as that of subjectivism,

which postulates men without a world. World and men do not

exist apart from each other, they exist in constant interaction.

Marx does not espouse such a dichotomy, nor does any other

critical, realistic thinker. What Marx criticized and scientifically

destroyed was not subjectivity, but subjectivism and psy

chologism. Just as objective social reality exists not by chance,

but as the product of human action, so it is not transformed by

chance. If men produce social reality (which in the ‘inversion

of the praxis’ turns back upon them and conditions them),

then transforming that reality is an historical task, a task for

men.

Reality which becomes oppressive results in the contra

distinction of men as oppressors and oppressed. The latter,

whose task it is to struggle for their liberation together with

those who show true solidarity, must acquire a critical aware

ness of oppression through the praxis of this struggle. One of

the gravest obstacles to the achievement of liberation is thatoppressive reality absorbs those within it and thereby acts to

I

I

I

I

4

i

28

r

submerge men’s consciousness.6 Functionally, oppression is

domesticating. To no longer be prey to its force, one must

emerge from it and turn upon it. This can be done only by

means of the praxis: reflection and action upon the world in

order to transform it.

Hay que hacer la opresion real todavfa mAs opresiva ahadiendo a

aquella la conciencia de la opresidn haciendo la infamia todavfa

mas infamante, al pregonarla.7

X )

>

I

Making ‘real oppression more oppressive still by adding to [t

the realization of oppressionj__corresponds to the dialectical

relation between the subjective and the objective. Only in this

state of interdependence is an authentic praxis possible,

without which it is impossible to resolve the oppressoroppressed contradiction. To achieve this goal, the oppressed

must confront reality critically, simultaneously objectifying

and acting upon that reality. A mere perception of reality not

followed by this critical intervention will not lead to a trans

formation of objective reality - precisely because it is not a

true perception. This is the case of a purely subjectivist percep

tion by someone who forsakes objective reality and creates a

false substitute.

A different type of false perception occurs when a change

in objective reality would threaten the individual or class

interests of the perceiver. In the first instance, there is no

critical intervention in reality because that reality is fictitious:

there is none in the second instance because intervention would

contradict the class interests of the perceiver. In the latter case

the tendency of the perceiver is to behave ‘neurotically’. The

fact exists; but both the fact and what may result from it may

6. ‘Liberating action necessarily involves a moment of perception and

volition. This action both precedes and follows that moment, to which

it first acts as a prologue and which it subsequently serves to effect and

continue within history. The action of domination, however, does not

necessarily imply this dimension; for the structure of domination is

maintained by its own mechanical and unconscious functionality.’ From

an unpublished work by Jose Luis Fiori, who has kindly granted per

mission to quote him.

7. [To bring it to public notice, we must make oppression even more

real by adding to the consciousness of oppression the infamy which at the

same time has to be made more infamous.]

23

be prejudicial to him. Thus it becomes necessary, not precisely

to deny the fact, but to see it differently. This rationalization

as a defence mechanism coincides in the end with subjectivism.

A fact with its truths rationalized, though not denied, loses its

objective base. It ceases to be concrete and becomes a myth

created in defence of the class of the perceiver.

Herein lies one of the reasons for the prohibitions and the

difficulties (to be discussed at length in chapter 4) designed to

dissuade the people from critical intervention in reality. The

oppressor knows full well that this intervention would not be

to his interest. What is to his interest is for the people to

continue in a state of submersion, impotent in the face of

oppressive reality. Lukacs’ warning to the revolutionary party

in Lenine is relevant here:

— il droit, pour employer les mots de Marx, expliqucr aux masses

leur propre action non seulement afin d’assurer la continuity des

experiences rdvolutionnaires du proletariat, mais aussi d’activer consciemment le d£veloppement ult£rieur de ces experiences.

In asserting this need, Lukacs is unquestionably raising the

issue of critical intervention. ‘To explain to the masses their

own action’ is to clarify and illuminate that action, both

in terms of its relationship to the the objective facts which

prompted it, and alsoof its aims. The more the people unveil this

challenging reality which is to be the object of their trans

forming action, the more critically they enter that reality.

In this way they are ‘consciously activating the subsequent

development of their experiences’. There would be no human

action if there were no objective reality, no world to be the

‘not I’ of man to challenge him; just as therejvould be no.

human action if man were not a ‘projection’, if he were not able

to transcend himself, to perceive his reality and understand it in

order to transform it.

In dialectical thought, world and action arc intimately

interdependent. But action is human only when it is not merely

an occupation but also1 a preoccupation, that is, when it is. not

dichotomized from reflection. Reflect ioh, whicb is essential to

action, is implicit in Lukacs’ requirement of‘explaining to the

masses their own action’, just as it is implicit in the purpose

ttk.

II

L

I

I

h’i1

'

I?

p

I

I

r

30

he attributes to this explanation: that of‘consciously activating

—the subsequent development of experience-.__________________

For us, however, the requirement is seen not in terms of

explaining to, but rather entering into a dialogue with, the people

about their actions. In any event, no reality transforms itself,«

and the duty which Lukacs ascribes to the revolutionary party

of ‘explaining to the masses their own action’ coincides with

our affirmation of the need for the critical intervention of the

people in reality through the praxis. The pedagogy of the

oppressed, which is the pedagogy of men engaged in the fight

for their own liberation, has its roots here. And those who

recognize, or begin to recognize, themselves as oppressed must

be among the developers of this pedagogy. No pedagogy which

is truly liberating can remain distant from the oppressed by

treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their

emulation models from among the oppressors. The oppressed

must be their Own example in the struggle for their redemption.

The pedagogy of the oppressed, animated by authentic,

humanist (not humanitarian) generosity, presents itself as a

pedagogy of man. Pedagogy whjch begins with the egoistic

interests of the oppressors (an egoism cloaked in the false

generosity of paternalism) and makes of the oppressed the

objects of its humanitarianism, itself maintains and embodies

oppression. It is an instrument of dehumanization. This is why,

as we affirmed earlier, the pedagogy of the oppressed cannot

be developed or practised by the oppressors. It would be a

contradiction in terms if the oppressors not only defended but

actually implemented a liberating education.

But if the implementation of a liberating education requires

political power and the oppressed have none, how then is it

possible to carry out the pedagogy of the oppressed prior to the

revolution? This is a question of the greatest importance, (he

reply to which is at least tentatively outlined in chapter 4.

One aspect of the reply is to be found in the distinction between

8. ‘The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances

and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed men arc products of other

circumstances and changed upbringing, forgets that it is men that change

circumstances and that the educator himself needs educating.’ (Karl Marx

and Friedrich Engels, Selected Works.}

g

rgd i

31

systematic education, which can only be changed by political

-power^ and educational-projects^- which should be carried out with the oppressed in the process of organizing them.

The pedagogy of the oppressed, as a humanist and libertarian

pedagogy, has two distinct stages. In the first, the oppressed

unveil the world of oppression and through the praxis commit

themselves to its transformation. In the second stage, in which

the reality of oppression has already been transformed, this

pedagogy ceases to belong to the oppressed and "becomes’ a

pedagogy of all men in the process of permanent liberation.

Tn both stages, it is always through action in depth that the

culture of domination is culturally confronted.^ In the first

stage this confrontation occurs through the change in the way

the oppressed perceive the world of oppress ion; in the second

stage, through the expulsion of the myths created and developed

in the old order, which like spectres haunt the new structure

emerging from the revolutionary transformation. ’

In its first stage the pedagogy must deal with the problem

of the consciousness of the oppressed and the oppressor, the

problem of men who oppress and men who suffer oppression. It

must take into account their behaviour, their view of the world,

and their ethics. A particular problem is the duality of the op

pressed: they are contradictory, divided beings, shaped by and

existing in a concrete situation of oppression and violence.

Any situation in which A objectively exploits B or hinders

his pursuit of self-affirmation as a responsible person is one

of oppression. Such a situation in itself constitutes violence,

even when sweetened by false generosity, because it interferes

with man’s ontological and historical vocation to be more fully

human. With the establishment of a relationship of oppression,

violence has already begun. Never in history has violence been

initiated by the oppressed. How could they be the initiators,

if they themselves are the product of violence? How could they

be the sponsors of something whose objective inauguration called ~forth their existence as oppressed ? There would be no oppressed

had there been no prior situation of violence to establish their

subjugation.

9. This appears to be the fundamental aspect of Mao’s Cultural Revo

lution.

1

32

I

I

I

f

s

I

f

Violence is initiated by those who oppress, who exploit,

who fail to recognize others as people - not by those who are

oppressed, exploited, and unrecognized. It is not the unloved

who cause disaffection, but those who cannot love because they

love only themselves. It is not the helpless, subject to terror,

who initiate terror, but the violent, who with their power

create the concrete situation which begets the ‘rejects of life’.

It is not the tyrannized who are the source of despotism, but

the tyrants; nor the despised who initiate hatred, but those

who despise. It is not those whose humanity is denied them who

negate man, but those who denied that humanity (thus negating

their own as well). Force is used not by those who have become

weak under the preponderance of the strong, but by the

strong who have emasculated them.

For the oppressors, however, it is always the oppressed

(whom they obviously never call ‘the oppressed’ but - depend

ing on whether they are fellow countrymen or not - ‘those

people’ or ‘the blind and envious masses’ or ‘savages’ or

‘natives’ or ‘subversives’) who are disaffected, who are

‘violent’, ‘barbaric’, ‘wicked’, or ‘ferocious’ when they

react to the violence of the oppressors.

Yet it is - paradoxical though it may seem - precisely in the

response of the oppressed to the violence of their oppressors

that a gesture of love may be found. Consciously or un

consciously, the act of rebellion by the oppressed (an act which

is always, or nearly always, as violent as the initial violence

of the oppressors) can initiate love. Whereas the violence of the

oppressors prevents the oppressed from being fully human,

the response ol the latter to this violence is grounded in the

desire to pursue the right to be human. As the oppressors

dehumanize others and violate their rights, they themselves

also become dehumanized. As the oppressed, fighting to be

human, take away the oppressors’ power to dominate and

suppress, they restore to the oppressors the humanity they had

lost in the exercise of oppression.

It is only the oppressed who, by freeing themselves, can

free their oppressors. The latter, as an oppressive class, can

free neither others nor themselves. It is therefore essential

that the oppressed wage the struggle to resolve the contradiction

33

in which they arc caught. That contradiction will be resolved

by the appearance of the new man who is neither oppressor nor

oppressed — man in the process of liberation. If the goal of the

oppressed is to become fully human, they will not achieve their

goal by merely reversing the terms of the contradiction, by

simply changing poles.

This may seem simplistic: it is not. Resolution of the

oppressor-oppressed contradiction indeed implies the disappearance of the oppressors as a dominant class. However,

the restraints imposed by the former oppressed on their

oppressors, so that the latter cannot reassume their former

position, do not constitute oppression. An act is oppressive

only when it prevents men from being more fully human.

Accordingly, these necessary restraints do not in themselves

signify that yesterday’s oppressed have become today’s

oppressors. Behaviour which prevents the restoration of the

oppressive regime cannot be compared with acts which createand maintain it. One cannot compare it with acts by which few

men deny the majority their right to be human.

However, the moment the new regime hardens into a domin

ating ‘bureaucracy’10 the humanist dimension of the struggle

is lost and it is no longer possible to speak of liberation.

Hence our insistence that the authentic solution of the oppressor

-oppressed contradiction does not lie in a mere reversal of

position, in moving from one pole to the other. Nor does it

lie in the replacement of the former oppressors with new ones

who continue to subjugate the oppressed - all in the name of

their liberation.

But even when contradiction is resolved authentically

by a new situation established by liberated workers, the

former oppressors do not feel liberated. On the contrary,

they genuinely consider themselves to be oppressed. Condi

tioned by the experience of oppressing others, any situation

other than their former seems to them like oppression. For10. This rigidity should not be identified with the restraints that must

be imposed on the former oppressors so they cannot restore the oppressive

order. Rather, it refers to the revolution which becomes stagnant and

turns against the people, using the old repressive, bureaucratic State

apparatus (which should have been drastically suppressed, as Marx so

often emphasized).

34

merly, they could cat, dress, wear shoes, be educated, travel,

and hear Beethoven; whilemil lions didnot eat, had no clothes

or shoes, neither studied nor travelled, much less listened to

Beethoven. Any restriction on this way of life, in the name of

the rights of the community, appears to the former oppressors

as a profound violation of their individual rights - although

they had no respect for the millions who suffered and died of

hunger, pain, sorrow, and despair. For the oppressors, ‘human

beings’ refers only to themselves; other people are ‘things’.

For the oppressors, there exists only one right: their right to

live in peace, over against the right, not always even recognized,

but merely conceded, of the oppressed to survival. And they

make this concession only because the existence of the oppressed

is necessary to their own existence.

This behaviour and way of understanding the world and men

(which necessarily makes the oppressors resist the installation

of a new regime) is explained by their experience as a dominant

class. Once a situation of violence and oppression has been

established, it engenders an entire way of li?e anif behaviour

Tor those caught up in it - oppressors and oppressed alike.

Both are submerged in this situation, and both bear the marks

of oppression. Analysis of existential situations of oppression

reveals that their inception lay in an act of violence - initiated

by those with power. This violence, as a process, is perpetuated

from generation to generation of oppressors, who become its

heirs and are shaped in its climate. This climate creates in the

oppressor a strongly possessive consciousness - possessive

of the world and of men. Apart from direct, concrete, material

possession of the world and of men, the oppressor consciousness

could not understand itself - could not even exist. Fromm

said of this consciousness that, without such possession,

‘it would lose contact with the world’. The oppressor con

sciousness tends to transform everything surrounding it into an

object of its domination. The earth, property, production,

the creations of men, men themselves, time - everything is

reduced to the status of objects at its disposal.

In their unrestrained eagerness to possess, the oppressors

develop the conviction that it is possible for them to transform

everything into objects of their purchasing power; hence their

35

strictly materialistic concept of existence. Money is the measure

of all .things, and profit the primary goal. For the oppressors,

what is worthwhile is to have more - always more - even at the

cost of the oppressed having less or having nothing. For them,

to be is to have and to be of thejjiaving’ class.

A?"beneficiaries of a situation of oppression, the oppressors

cannot perceive that if having is a condition of being, it is a

necessary condition for all men. This is why their generosity is

false. Humanity is a ‘thing’, and they possess it as an exclusive

right, as inherited property. To the oppressor consciousness,

the humanization of the ‘others’, of the people, appears as

subversion, not as the pursuit of full humanity.

The oppressors do not perceive their monopoly of having more

as a privilege which dehumanizes others and themselves.

They cannot see that, in the egoistic pursuit of having as a

possessing class, they suffocate in their own possessions and

no longer are; they merely have. For them, having more is an

inalienable right, a right they acquired through their own

‘effort’, with their ‘courage to take risks’. If others do not have

more, it is because they are incompetent and lazy, jindjvprst

"oT aTTisTTieir uniustifiableTngratitude towards the ‘generous

gestures’~of the dominant class., Precisely_..b^use .they are

‘ungrateful’ and ‘envious’, the oppressed are regarded as

potential enemies who must be watched.

. * It cou Id Tiot^be^oTh erwise. If the humanization of the

oppressed signifies subversion, so also does their freedom;

hence the necessity for constant control. And the more the

oppressors control the oppressed, the more they change

them into apparently inanimate ‘things’. This tendency of the

oppressor consciousness to render everything and everyone it

encounters inanimate, in its eagerness to possess, unquestion

ably corresponds with a tendency to sadism. Here is Fromm in

The Heart ofMan:

The pleasure in complete domination over another person (or other

animate creature) is the very essence of the sadistic drive. Another

way of formulating the same thought is to say that the aim of sadism

is to transform a man into a thing, something animate into something

inanimate, since by complete and absolute control the living loses one

essential quality of life - freedom.

£

I

} *

36

twtcli Cf'J.

/

37

d

Sadistic love is a perverted love - a love of death, not of life.

Thus, one of the characteristics of the oppressor consciousness,

and its necrophilic view of the world is sadism. As the oppressor

consciousness, in order to dominate, tries to thwart the seeking,

restless impulse, and the creative power which characterize

life, it kills life. More and more, the oppressors are using science

and technology as unquestionably powerful instruments for

their purpose: the maintenance of the oppressive order through

manipulation and repression.^ The oppressed, as objects, as

‘things’, have no purposes except those their oppressors pre

scribe for them.

In the light of what has been said, another issue of indubitable

importance arises: the fact that certain members of the oppressor

class join the oppressed in their struggle for liberation, thus

moving from one pole of the contradiction to the other.

Theirs is a fundamental role, and has been so throughout the

history of this struggle. It happens; however, that as they cease

to be exploiters or indifferent spectators or simply the heirs of

_ exploitation and move to the side of the exploited, they almost

always' bring \vithi them the marks of their origin: their pre,

judices and their deformations, which include a lack of con

fidence in the people’s ability to think, to want, and to know.

Accordingly, these adherents to the people’s cause constantly

run the risk of falling into a type of generosity as harmful as

that of the oppressors. The generosity of the oppressors is

nourished by an unjust order, which must be maintained in

order to justify that generosity. Our converts, on the other

hand, truly desire to transform the unjust order; but because

of their background they believe that they must be the executors

of the transformation. They talk about the people, bu£they

do not trust them; and trusting the people is the indispensable

precondition for revolutionary change. A real humanist can be

identified more by his trust in the people, which engages hjm in^

Their struggle, than by a thousand actions in their favour without

that trust.

""Those who authentically commit themselves to the people

must re-examine themselves constantly. This conversion is so

9

II. Regarding the ‘dominant forms of social control’, sec Herbert

Marcuse’s One- Dimensional Man and Eros and Civilization.

radical as not to allow for ambivalent behaviour. To affirm this

commitment but to consider oneself the proprietor of revolu

tionary wisdom - which must then be given to (or imposed on)

the people - is to retain the old ways. The man who proclaims

devotion to the cause of liberation yet is unable to enter into

communion with the people, whom he continues to regard as

totally ignorant, is grievously self-deceived. The convert who

approaches the people but feels alarm at each step they take,

each doubt they express, and each suggestion they offer, and

attempts to impose his ‘status’, remains nostalgic towards his

origins.

Conversion to the people requires a profound rebirth.

Those who undergo it must take on a new form of existence;

they can no longer remain as they were. Only through comrade

ship with the oppressed can the converts understand their

characteristic ways of living and behaving, which in diverse

moments reflect the structure of domination. One of these

characteristics is the previously mentioned existential duality

of the oppressed, who are at the same time themselves and the

oppressor whose image they have internalized. Accordingly,

until they concretely ‘discover’ their oppressor and in turn their

own consciousness, they nearly always express fatalistic

attitudes towards their situation.

The peasant begins to get courage to overcome his dependence when

he realizes that he is dependent. Until then, he goes along with the

boss and says ‘What can I do? I’m only a peasant.’12

When superficially analysed, this fatalism is sometimes inter

preted as a docility that is a trait of national character. Fatalism

in the_guise of docility is the fruit of an historical and sociological situation, not an essential characteristic of a people’s -;

behaviour. Ialmost always rcLitcd tFOic power ofScstiny

"or fate^or fortune - inevitable forces - or to a distorted view

of God. Under the sway of ma’gic and myth, the oppressed.especially the peasants, who arc almost submerged in nature

(see Mendes’ Memento de Vivos) - sec their suffering, the fruit

of exploitation, as the will of God - as if God were the creator

of this ‘organized disorder’.

12. Words of a peasant during an interview with the author.

!

38

39

Submerged in reality, the oppressed cannot perceive clearly

:*he ‘order’ which serves the interests of the oppressors whose

ttuage they have mternahzed. Chafing under the restrictions

oi this order, they often manifest a type of horizontal violence,

striking out at their own comrades for the pettiest reasons’

Frantz Fanon, in The Wretchedofthe Earth, writes :

The colonized man will first manifest this aggressiveness which has

been deposited in his bones against his own people. This is the period

when the niggers beat each other up, and the police and magistrates

do not know which way to turn when faced with the astonishing

waves ofcrime in North Africa. ... While the settler or the policeman

has the right the livelong day to strike the native, to insult him and

to make him crawl to them, you will see the native reaching for his

knife at the slightest hostile or aggressive glance cast on him by an

other native; for the last resort of the native is to defend his personal

ity vis-a-vis his brother.

It is possible that in this behaviour they are once more mani

festing their duality. Because the oppressor exists within their

oppressed comrades, when they attack those comrades they are

indirectly attacking the oppressor as well.

On the other hand, at a certain point in their existential

experience the oppressed feel an irresistible attraction towards

the oppressor and his way of life. Sharing his way of life

becomes an overpowering aspiration. In their alienation, the

oppressed want at any cost to resemble the oppressor, to imitate

him, to follow him. This phenomenon is especially prevalent

in the middle-class oppressed, who yearn to be equal to the

‘eminent’ men of the upper class. Albert Memmi, in an

exceptional analysis of the ‘colonized mentality’, The Colonizer

and the Colonized, refers to the contempt he felt towards the

colonizer, mixed with ‘passionate’ attraction towards him.

How could the colonizer look after his workers while periodically