RF_DR.A_17_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

>

F; 4

No 77

RF_DR.A_17_SUDHA

0

1

V -> •

i

.-•V

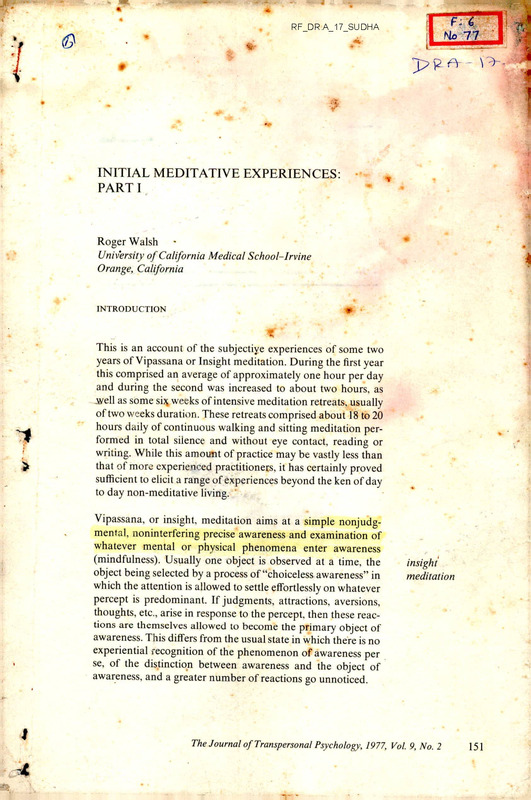

INITIAL MEDITATIVE EXPERIENCES:

PARTI

Roger Walsh

University of California Medical School-Irvine

Orange, California

4

INTRODUCTION

*

This is an account of the subjective experiences of some two

years of Vipassana or Insight meditation. During the first year

this comprised an average of approximately one hour per day

and during the second was increased to about two hours, as

.well as some six weeks of intensive meditation retreats, usually

of two weeks duration. These retreats comprised about 18 to 20

hours daily of continuous walking and sitting meditation per

formed in total silence and without eye contact, reading or

writing. While this amount of practice may be vastly less than

that of more experienced practitioners, it has certainly proved

sufficient to elicit a range of experiences beyond the ken of day

to day non-meditative living.

Vipassana, or insight, meditation aims at a simple nonjudgmental, noninterfering precise awareness and examination of

whatever mental or physical phenomena enter awareness

(mindfulness). Usually one object is observed at a time, the

object being selected by a process of “choiceless awareness” in

which the attention is allowed to settle effortlessly on whatever

percept is predominant. If judgments, attractions, aversions,

thoughts, etc., arise in response to the percept, then these reac

tions are themselves allowed to become the primary object of

awareness. This differs from the usual state in which there is no

experiential recognition of the phenomenon of awareness per

se, of the distinction between awareness and the object of

awareness, and a greater number of reactions go unnoticed.

insight

meditation

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

151

¥

&

I

training

participant

observers

In presenting this material I have several aims. The first is

simply to share these explorations with the hope that they^may

prove helpful for other beginning meditators, since there is

surprisingly little in-depth writing on initial meditative experi

ences (Walsh, 1977b). I would also like to examine them in the

light of Western psychology, especially recent advances in

learning theory, state-dependent learning, altered states of

consciousness, behavioral self-control, and traditional psy

chodynamics. I also wish to do exactly the opposite: i.e., where

possible to examine Western psychology within the light of

these experiences. While there are a number of poignant, rich

and courageous accounts of individuals’ experiences and in

sights (e.g., Shattock, 1972; Lerner, 1977), they lack the pre

cision and psychological background essential for scientifically

productive analysis. Thus there have recently been repeated

requests by a variety of Western psychologists (e.g., Shimano-& Douglas, 1975; Tart, 1975a; Globus, 1976), for indi

viduals with extensive training in the behavioral sciences to

undertake the exploration of consciousness as trained partici

pant observers. This paper seems to present an opportunity for

beginning a preliminary testing of such a paradigm.

While a number of things led me in the direction of meditation, the major forerunner• was clearly a year and a half of

intensive individual psychotherapy which has already been

described in some detail (Walsh, 1976,1977a). Certain features

of this therapy seemed especially conducive to meditation.

These included a markedly increased awareness of, and per

ceptual sensitivity to, the formerly unrecognized stream of

inner consciousness and a heightened ability to discriminate

among altered states within this stream. There was also less

fear of, and more trust in, this formerly subliminal realm of

awareness and motivation, and hence a greater sense of trust in

myself, “myself” having now been expanded to include this

formerly unknown realm. In particular some of the states

which emerged towards the end of therapy were characterized

by feelings of peace, and a relative absence of thoughts, needs

and “doing.” These states readily became the objects of nonin

terfering awareness, and it felt inappropriate to “work with

them” in a traditional psychotherapeutic way.

1 began meditation with one-half hour each day and during the

first three to six months there were few times during which I

could honestly say with complete certainty that I was definitely

experiencing benefits from it. Except for the painfully obvious

stiff back and sore knees, the psychological effects other than

occasional relaxation felt so subtle and ephemeral that I could

never be sure that they were more than a figment of my wishes

152

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

t

4

and expectations. Certainly had it not been for these expecta

tions, prior psychotherapeutic experiences, and the encour

agement of more experienced practitioners, I would never

have gotten beyond the first couple of weeks. The nature of

meditation seems to be, especially at first, a slow but cumula

tive process, a fact which may be useful for beginners to know.

However, with continued perseverance, subtle effects just at

the limit of my perceptual threshold did begin to become

apparent. I had expected the eruption into awareness of

powerful, concrete experiences, if not flashes of lightning and

pealing of bells, then at least something of sufficient intensity

to make it very clear that I had “gotten it,” whatever “it” was.

What “it” actually turned out to be was not the appearance of

formerly nonexistent mental phenomena, but rather a gradual

incremental increase in perceptual sensitivity to the formerly

subliminal portions of my own inner stream of consciousness,

a process which had begun in therapy.

At first this was apparent as the occasional ephemeral ap

pearance of a sense of peace or some other subtle, hard to

categorize affect interspersed among innumerable pains, itch

es, doubts, questions, fears and fantasies which occupied the

majority of meditation sitting time. Usually one or more of

these “events” would be deemed important enough to divert

my attention from meditation. With increased practice the

disruptive nature of these breaks became more and more ap

parent, and the stringency of the criteria for disrupting medi

tation became progressively higher. Interestingly enough the

order in which the different kinds of distractions were given up

seemed to provide an index of the strengths of my attachments.

For example, I am an analytic, intellectually curious person

who loves to understand things. This predeliction runs counter

to the Vipassana process which emphasizes just watching and

observing the arising and passing away of all mental pheno

mena, thoughts, feelings, sensations, without analyzing or

changing them in any way. Therefore, when something unu

sual occurred in meditation. I may have thought, “Wow, I could

really learn something from that.” This thought was usually

sufficient to jolt me out of a relaxed meditative watching and

into an active analytic probing and changing of the experience.

a slow

process

a gradual

increase in

sensitivity

the strength

of attachments

FANTASY

“When one sits down with eyes closed to silence the mind, one

is at first submerged by a torrent of thoughts—they crop up

everywhere like frightened, nay, aggressive rats” (Satprem,

4

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

%

153

a torrent

offantasies

1968, p. 33). The more sensitive I became, the more I was

forced to recognize that what I had formerly believed to be my

rational mind preoccupied with cognition, planning, problem

solving, etc., actually comprised a frantic torrent of forceful,

demanding, loud, and often unrelated thoughts and fantasies

which filled an unbelievable proportion of consciousness even

during purposive behavior. The incredible proportion of

consciousness which this fantasy world occupied, my power

lessness to remove it for more than a few seconds, and my

former state of mindlessness or ignorance of its existence,

staggered me (I am here using mindlessness in an opposite

sense to the Vipassana term mindful, which means aware of

the nature of the object to which the mind is attending). Fore

most among the implicit beliefs of orthodox Western psychol

ogy is the assumption that man spends most of his time rea

soning and problem solving, and that only neurotics and other

abnormals spend much time, outside of leisure, in fantasy

(Tart, 1975b). However, it is my impression that prolonged

self-observation will show that at most times we are living

almost in a dream world in which we skillfully and automati

cally yet unknowingly blend inputs from reality and fantasy in

accordance with our needs and defenses. Interestingly this

“mindlessness” seemed much more intense and difficult to

deal with than in psychotherapy where the depth and sensitiv

ity of inner awareness seemed less, and where the therapist

provided a perceptual focus and was available to pull me back

if I started to get lost in fantasy.

The pjesence of inner dialogue and fantasy seems to present^

limiting factor for the sense of closeness and unity with another

persom However, if I am with another person, and free of

dialogue and fantasy, and feeling an emotion, especially a

positive one such as love, which I know the other person to

be also experiencing, then it feels as though there are no

detectable ego boundaries; we are together in love. But if part

of my mind is preoccupied with dialogue and fantasies, then

my awareness is split; I know that my experience is different

from the other individual’s, and feel correspondingly dis

tanced and separated.

the subtlety

and complexity

offantasies

The subtlety, complexity, infinite range and number, and en

trapping power of the fantasies which the mind creates seems

impossible to comprehend, to differentiate from reality while

in them, and even more so to describe to one who has not ex

perienced them. Layer upon layer of imagery and quasilogic

open up in any point to which attention is directed. Indeed it

gradually becomes apparent that it is impossible to question

and reason one’s way out of this all-encompassing fantasy since

*

154

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

the very process of questioning, thinking, and seeking only

creates further fantasy.

Meditation Exercise

Since the power and extent of this entrapment is so difficult to

convey to someone without personal experience of it, I’d

strongly encourage any non-meditator to use the following

concentration exercise (Goldstein, 1976) before continuing.

Set an alarm for a minimum of 10 minutes. Then take a

comfortable seat, close your eyes, and turn your attention to

the sensations of breathing in your abdomen. Feel the abdo

minal wall rising and falling and focus your attention as

carefully, precisely, and microscopically as possible on the in

stant to instant sensations that occur in your abdomen. Don’t

let your attention wander for a moment. If thoughts and

feelings arise, just let them be there and continue to focus your

awareness on the sensations.

Now as you remain aware of the sensations, start counting

each breath until you reach ten, and then start again at one.

However, if you lose count, or if your mind wanders from the

sensations in the abdomen, even for an instant, go back to one.

If you get lost in fantasy or distracted by outside stimuli, just

recognize what happened and gently bring your mind back to

the breath. Continue this process until the alarm tells you to

stop and then attempt to estimate how much of the time you

were actually mindfully focussed. As your perception sharpens

with more practice, you would probably recognize that you

have greatly overestimated, but this should be sufficient to give

a flavor of the extent of the problem. “Your mind has a mind of

its own, where do you fit in?” (Sujata, 1975).

focussing

attention

on

breathing

The impossibility of working or thinking one’s way out of this

multilayered, multidimensional fantasy, world into which one

falls, rapidly becomes apparent, even though it is very tempting

to try to do so. That leaves within the experiential meditative

world only the primary sensations, e.g., pain and breathing, on

which to focus as perceptual anchors. By focussing attention

back on the breathing it seems that the energy or arousal going

into the fantasy by virtue of the attention being paid it is

withdrawn, and it collapses under its own weight leaving only

the primary sensations until the next fantasy arises. This is

presumably an example of Tart’s (1975a) statement that cer

tain mental structures are dependent on a minimum amount of

attention for their creation and maintenance.

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

155

Fantasy and Illusion

the background

ofdialogues

and

fantasies

the brain

as a

difference

detector

The power and pervasiveness of these inner dialogues and

fantasies left me amazed that we could be so unaware of them

during our normal waking life and reminded me of the Eastern

concept of maya or all-consuming illusion. The question of

why we don’t recognize them seems incredibly important,

but to date I have seen no explanations other than the almost

universal ones among the meditative-yogic traditions that

normal man is an automaton, more asleep than awake, etc.

Several mechanisms seem to be operating here. Firstly, the

dialogue-fantasy creations are completely congruent with the

current ego state and with what Gendlin (1962) and Welwood

(1976) would call the “felt meaning,” i.e., that affective back

ground or context which we assay when we try to answer the

question “how do you feel right now?” It is the contrast

between the dialogues-fantasies and the background affective

state which makes the detection of their pervasiveness easier. It

is therefore interesting that I have not infrequently found that

when I am what initially appears to be dialogue-free, closer

examination of my consciousness reveals dialogue with which

I had been completely and unconsciously identified such as

“I’m really doing this well, I’m in a really clear place, I don’t

have any dialogue going. I’m really getting to be a good med

itator, etc.” However, at such times a thought like, “I’m not

getting anything out of this,” stands out strongly and is readily

identified for what it is, yet another thought. This fits well with

the general neurophysiological principle that the brain is es

sentially a difference detector which picks up differences

between stimuli or stimulus complexes rather than absolute

levels of individual stimuli. Other factors possibly accounting

for our inability or unwillingness to identify the extent of this

dialogue-fantasy may be the extent to which we have habi

tuated to its presence. Furthermore, it is only when we attempt

to stop it that we become aware of its remarkable hold on us,^a

situation strongly reminiscent of addictions.

A further masking factor may comprise the process of “time

sharing.” Usually we are able to switch rapidly between fo

cussing on real stimuli and fantasy in a manner analogous to

the process by which a computer rapidly switches between

different terminals which may be feeding in input simultan

eously. Thus for “normal” levels of external sensory awareness

and performance there may be relatively little functional im

pairment apparent, especially since the vast majority of the

population is also functioning in this manner. It also rapidly

becomes apparent that these dialogue-fantasies may serve a

major (perhaps the major?) defensive function. If so then ob-

156

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

viously there would be major dynamics operating to prevent

awareness of them (perceptual defense).

9

It is clear that fantasy plays a major role in psychological

health and pathology. Obviously a full exploration of these

relationships is beyond the scope of this article, but it is clear

that meditation offers insights into the phenomena which may

extend far beyond current Western psychological under

standing.

Traditionally fantasy has been seen as ranging from being a

source of creativity and pleasure in well-adapted individuals

(e.g., Offer, 1973; Offer & Offer, 1974) to a central hallmark

of psychopathology when excessive (Linn, 1975). When the

individual believes his fantasies to be real, and they are dis

cordant with those of the majority of society, the fantasies are

called hallucinations and he is labelled psychotic. Also, when

the fantasies are especially painful and egodystonic, the indi

vidual may experience himself, and be diagnosed, as mentally

ill, even though he knows them to be fantasies. Thus in Western

psychology, fantasies are seen as normal or even beneficial,

unless they prove especially painful or overwhelming.

However, a remarkably wide range of meditation and yogic

disciplines from a variety of cultures hold a very different

view. They assert that whether we know it or not, untrained

individuals are prisoners of their own minds, totally and un

wittingly trapped by a continuous inner fantasy-dialogue

which creates an all-consuming illusion or maya.

fantasy

as viewed

traditionally

fantasy

as illusion

We are what we think.

All that we are arises with our thoughts.

With our thoughts we create the world.

The Buddha (Byrom, 1976)

“Normal” man is thus seen as asleep or dreaming. When the

dream is especially painful or disruptive it becomes a night

mare and is recognized as psychopathology, but since the vast

majority of the population dreams, the true state of affairs goes

unrecognized. When the individual permanently disidentifies

from or eradicates this dream he is said to have awakened and

can now recognize the true nature of his former state and that

of the population. This awakening or enlightenment is the aim

of the meditative-yogic disciplines (e.g., Ouspensky, 1949; De

Ropp, 1968; Nyanaponika Thera, 1972; Ram Dass, 1974,

1976, 1977; Goldstein, 1976; Goleman, 1977; Wilber, 1977).

However, according to Tart (1975a), there is as yet considera

ble resistance to this idea in Western psychology and psy

chiatry:

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

157

A

We have studied some aspects of samsara (illusion, maya) in far

more detail than the Eastern traditions that originated the concept

of samsara. Yet almost no psychologists apply this idea to them

selves. They assume . . . that their own states of consciousness are

basically logical and clear. Western psychology now has a chal

lenge to recognize this detailed evidence that our “normal” state

is a state of samsara and to apply the immense power of science

and our other spiritual traditions, East and West, to the search for

a way out (p. 286).

Perceiving and Labeling Fantasy

quieting

the

internal

dialogue

With continued practice the speed, power, loudness, and con

tinuity of these thoughts and fantasies began to slowly dimin

ish, leaving subtle sensations of greater peace and quiet. After

a period of about four or five months there occurred episodes

in which I would open my eyes at the end of meditation and

look at the outside world without the presence of concomitant

internal dialogue. This state would be rapidly terminated

by a rising sense of anxiety and anomie accompanied by the

thought, “I don’t know what anything means.” Thus, I could be

looking at something completely familiar, such as a tree, a

building, or the sky, and yet without an accompanying internal

dialogue to label and categorize it, it felt totally strange and

devoid of meaning. It seems that what made something famil

iar and hence secure was not simply its recognition, but the

actual cognitive process of matching, categorizing and labeling

it, and that once this was done, then more attention and reactiv

ity was focussed on the label and labeling process rather than

on the stimulus itself. Thus the initial fantasy and thought-free

periods may feel both strange and distinctly unpleasant so tha£

we are at first punished by their unfamiliarit^. We have created

an unseen prison for ourselves whose bars are comprised of

thoughts and fantasies of which we remain largely unaware

unless we undertake intensive perceptual training. Moreover,

if they are removed we may be frightened by the unfamiliarity

of the experience and rapidly reinstate them. This is remini

scent of the lines of a poem by Yevtuschenko, who on visiting a

Canadian mink farm found the minks bred in open cages from

which they never tried to escape despite the fact that their

peers were slaughtered in the adjoining room.

He who is born in a cage,

shall weep for a cage.

Presumably this labeling process must modify our perception

in many ways, including reducing our ability to experience

each stimulus fully, richly, and newly, by reducing its multidi

mensional nature into a lesser dimensional cognitive labeling

158

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

framework. This must necessarily derive from the past, be less

tolerant of ambiguity, less here now, and perpetuative of a

sense of sameness and continuity to the world. This process

may represent the phenomenological and cognitive mediational basis of Deikman’s (1966) concept of automatization

and Don Juan’s “maintaining the world as we know it” (Cas

taneda, 1971, 1977). It is a far cry from the perceptual end state

devoid of all this labeling described by the Buddha as “In

what is seen there should be only the seen; in what is heard

only the heard; in what is sensed [as smell, taste or touch], only

the sensed, in what is thought only the thought” (Nyanaponika

Thera, 1962, p. 33).

It also provides an explanation of the electrophysiological

finding that experienced Zen practitioners may exhibit repeti

tive, non-habituating orientating response^to repeated stimuli

during meditation (Kasamatsu & Hirai, 1966; for a review see

Davidson, 1976). This is as would be predicted if they are in

fact responding to the stimuli themselves rather than to the

cognitive labeling process as described above. This also

provides an explanation for the “deautomatization” which may

occur with meditation (Deikman, 1966). One might also

wonder whether these Zen meditators and also self-actualizers

—who have been characterized among other things for their

ability to repetitively experience things freshly and uniquely

(Maslow, 1971)—display similar non-habituative patterns in

daily living.

This perceptual process might also provide support for, and a

substrate and an explanation of, constructional realism. This is

the philosophy which suggests that we do not simply learn to

recognize reality, but rather learn "to construct reality. This

philosophy has recently been rediscovered by researchers

in a diverse number of fields such as neuropsychology,

developmental psychology, philosophy, and consciousness

(Piaget, 1960; Pribram, 1976; Wilber, 1977). Although not yet

widely recognized, it may be that this philosophy should be

expanded to include the idea that we may construct a reality,

rather than the reality. In any event, the above phenomena

may provide an initial suggestion of the cognitive-perceptual

processes by which this is achieved.

developing

non-habituative

responses

constructing

our reality

THE FIRST MEDITATION RETREAT

The first meditation retreat, begun about one year after com

mencing sitting, was a very painful and difficult two-week

affair. I had never meditated for more than an hour at a time

and so continuous walking and sitting brought me to a

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

159

a marked

hypersensitivity

to all

stimuli

vivid

hallucinations

160

screaming halt. Within three hours 1 literally felt as though 1

had ingested a stimulant, and by six hours there were signifi

cant psychedelic effects. A marked hypersensitivity to all stim

uli both internal and external rapidly developed, resulting in

intense arousal, agitation, discomfort, and multiple chronic

muscle contractions, especially around the shoulders. This

agitation was associated with an increased sensitivity to pain

which seemed like part of a more general hypersensitivity. This

was particularly apparent during the first three or four days

and any exercise such as running would result in extreme

tenderness in the corresponding muscles.

One of the most amazing rediscoveries during this first retreat

was the incredible proportion of time, well over 90 percent,

which I spent lost in fantasy. Most of these were of the ego

self-aggrandizing type, so that when eventually I realized I was

in them, it proved quite a struggle to decide to give them up and

return to the breath, but with practice this decision became

slightly easier, faster, and more automatic. This by no means

happened quickly since over the first four or five days the

proportion of time spent in fantasy actually increased as the

meditation deepened, and on days three through five of the

retreat literally reached psychotic proportions. During this

period each time I sat and closed my eyes I would be imme

diately swept away by vivid hallucinations, losing all contact

with where I was or what I was doing until after an unknown

period of time a thought would creep in such as, “Am 1 really

swimming, lying on the beach?” etc., and then I would either

get lost back into the fantasy or another thought would

come: “Wait a moment, I thought I was meditating.” If the

latter, then 1 would be left with the difficult problem of trying

to ground myself, i.e., of differentiating between stimulus

produced percepts (“reality”) and entirely endogenous ones

(“hallucinations”). The only way this seemed possible was to

try finding the breath, and so I would begin frantically search

ing around in this hypnagogic universe for the sensations of the

breath. Such was the power of the hallucinations that some

times I would be literally unable to find it and would fall back

into the fantasy. If successful, I would recognize it and be

reassured that I was in fact meditating. Then in the next mo

ment I would be lost again in yet another fantasy. The clarity,

power, persuasiveness and continuity of these hallucinations is

difficult to adequately express. However, the effect of living

through three days during which time to close my eyes meant

losing contact almost immediately with ordinary reality was

extraordinarily draining to say the least. Interestingly enough

while this experience was uncomfortable and quite beyond my

control, it was not particularly frightening, if anything the

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

opposite. For many years I had feared losing control if I

let down defenses and voyaged too far along the road of

self-investigation and discovery. This appears to be a com

mon fear in most growth traditions and seems to serve a major

defensive function. Having experienced this once feared out

come, it now no longer seems so terrifying. Of course, the

paradox is that what we usually call control is actually exactly

the opposite, a lack of ability to let go of defenses.

During moments of clarity a process occurred which seems

supportive of Coleman’s (1976) hypothesis of global desensi

tization as one of the mediating mechanisms of meditative

effects. During this first retreat a lot of old, almost forgotten,

highly charged memories would arise into consciousness, re

main for a moment, then slowly sink back out of awareness.

Not infrequently as they did so I would be aware that the

affective charge, e.g., anger, sadness, etc., which was originally

associated with them would tend to diminish while they were

held in awareness, and that they had not infrequently attained

a neutral status by the time they disappeared back into the

unconscious. It was also interesting that some of these mem

ories ranged all the way back to age three or four, and to the

best of my recollection 1 had never recalled them previously

since their original occurrence. This phenomenology seems

highly consistent with Coleman’s proposed desensitization

mechanism.

the fear

of losing

control

the arousal

ofearly

memories

While a good 90 percent or more of this first retreat was taken

up with mindless fantasy and agitation, there did occur during

the second week occasional short-lived periods of intense

peace and tranquillity. These were so satisfying that, while I

would not be willing to sign up for a life-time in a monastery, I

could begin to comprehend the possibility of the truth of the

Buddhist saying that “peace is the highest form of happiness.”

Affective lability was also extreme. While more than 80 per

cent of the time of the first retreat was sheer pain, there were

not infrequently sudden apparently unprecipitated wide mood

swings, to completely polar emotions. Shorn of all my props

and distractions there was just no way to pretend that I had

more than the faintest inkling of self-control over either

thoughts or feelings.

With continued practice and greater sensitivity 1 began to gain

an experiential sense for the meaning of a word which is widely

and loosely used within meditation-yoga circles, namely the

type of “vibrations” that I was experiencing. It appeared that in

any sensory modality at all, there is an endogenously generat

ed continuous flux of perceptual-neural noise. Both figure and

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

161

greater

sensitivity

to

neurocybernetic

signals

ground, or signal and noise, are at least partially generated

by this process. What gets interpreted as signal or figure are

sometimes simply the larger fluctuations in neural activity of

sufficient magnitude to stand out effectively against the re

maining background. During periods of agitation these “vi

brations” appear stronger, larger, more frequent, and more

variable, whereas the reverse is true during periods of calm.

Presumably this simply represents a subjective correlate of the

neurophysiological activity and disturbance of the nervous

system. Since one of the aims of meditation is calm, this sug

gests a basis for the advice given by several meditation teachers

to do that which “fines down the vibration” and avoid those

things which lead to “heavy coarse vibrations” (Ram Dass,

1976). Thus these subjective sensations can be used as a sensi

tive self-guiding neurocybernetic signal to move one in the

direction of increasing calm and peace.

This also suggests a further basis for thejieightened sensitivity

of meditators, namely, the reduction in the magnitude of

background fluctuations or noise,. This would result in a

greater signaknoise ratio. It also raises the interesting question

of whether what is noise at one level of perceptual sensitivity

may not be signal at another more subtle level. Indeed this

leads to the ultimate question of whether there is in fact any

neural “noise” within the brain at all, or merely unrecognized

signals?

the

disrupting

power of

attachments

162

It soon became apparent that the type of material which

forceably erupted into awareness and disrupted concentration

was most often material—ideas, fantasies, thoughts, etc.—to

which I was attached (addicted) and around which there was

considerable affective charge. Indeed, it seemed that the strong

er the attachment or charge, the more often the material

would arise, a fact which suggested that we may all be subject

to an at least partially conditioned hierarchy of attachments

as well as a more biologically based hierarchy of needs a la

Maslow. There was a definite sense that attachments reduced

the flexibility and power of the mind, since whenever I was

preoccupied with a stimulus to which I was attached, then I had

difficulty in withdrawing my attention from it to observe other

stimuli which passed through awareness. This is reminiscent

in a more subtle form of a phenomenon called “stimulus

boundness” which is found in brain damaged individuals who,

once their attention is fixated on a particular stimulus, exper

ience great difficulty in transferring it to another object. Inter

estingly enough, the attachment or need to understand, itself

proved a perceptual and information limiting factor. As long

as I needed to understand something it was necessary to keep

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

that something around in awareness until it was understood

rather than allowing it to pass away of its own accord to be

replaced by the next object, i.e., “to understand” my experience I had to retain and analyze it and thereby stop the

free-flow of awareness.

Paradoxically it seems that a need or attachment to be rid of a

certain experience or state may lead to its perpetuation. The

clearest example of this has been with anxiety, which I worked

quite hard to reduce in my psychotherapy with considerable

success. However, some six months ago I suddenly began to

experience mild anxiety attacks of unknown origin which

curiously enough seemed to occur most often when I was

feeling really good and in the presence of a particular person

who I loved. At such times I would try all my various psycho

logical gymnastics to eradicate it since it was clearly not ok

with me to feel anxious. However, these episodes continued for

some five months in spite of, or as it actually turned out

because of, my resistance to them. During this time my prac

tice deepened and I was able to examine more and more of the

process during meditation. What I found was that I had con

siderable fear of fear and my mind therefore surveyed in a

radar-like fashion all endogenous and exogenous stimuli for

their fear evoking potential and all reactions for any fear

component. Thus there was a continuous mental radar-like

scanning process preset in an exquisitely sensitive fashion for

the detection of anything resembling fear. Consequently there

were a considerable number of false positives, i.e., non-fearful

stimuli and reactions which were interpreted as being fearful

or potentially fear provoking. Since the reactions to the false

positives themselves comprised fear and fear components,

there was of course an immediate chain reaction set up with

one fear response acting as the stimulus for the next. It thus

became very clear that my fear of and resistance to the fear was

exactly what was perpetuating it.

anxiety

the

perpetuation

fear

This insight and the further application of new meditative

awareness to the process certainly reduced but did not eradi

cate these episodes entirely. Paradoxically they still tended to

recur when I felt very calm and peaceful. It was not until the

middle of the next meditation retreat that the reasons for this

became clear. After the first few days of pain and agitation I

began to feel more and more peaceful and there came a sitting

in which I could feel my meditation deepen perceptibly and

the restless mental scanning slow more and more. Then as the

process continued to deepen and slow I was literally jolted by a

flash of agitation and anxiety accompanying a thought—“But

what do I do now if there’s no more anxiety to look for?” It was

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

163

the paradox

ofanxiety

paring away

attachments

164

apparent that if I continued to quieten, there would be neither

anxiety to scan for nor a scanning process itself, and my need to

get rid of anxiety demanded that I have a continuous scanning

mechanism, and the presence of the mechanism in turn created

the presence of anxiety. My “but what do I do now?” fear had

very effectively removed the possibility of the dissipation of

both, and its occurrence at a time when I was feeling most

peaceful, relaxed and safe, of course explained why I had been

subject to these anxiety episodes at the apparently paradoxical

times when I felt best. Paradoxically then it appears that within

the mind, if you need to be rid of something, then not only are

you likely to experience a number of false positives but you

may also need to have them around continuously so you can

keep getting rid of them. Thus within the province of the mind,

what you resist is what you get.

Since the things which tend to preoccupy consciousness and

disrupt meditation tend to be those things with strong attach

ment, it becomes apparent why the paring away of attach

ments is one of the three aims of the triune path of puri

fication (Pali: silya), discriminating wisdom (panna), and con

centration (sammhadi). These three are said to interact in such

a way that the deepening and increasing of one deepens the

other two and hence the whole meditative process. It took no

more than a few days of the first retreat to make this painfully

obvious. Any time I did something which broke the rules or

consciously disturbed other people’s practice or well-being, I

found myself agitated and disturbed in a way which affected

my own meditation as well as other apparently unrelated as

pects of my behavior. For example, one of the rules was that

we could shower only during two or three set times during the

day so as to minimize the possibility of disturbing other peo

ple’s meditation. However, I soon found that showers were an

excellent, if only partial antidote to the intense agitation and

dysphoria that I was experiencing. Thus I was certainly not

about to let a minor matter like the disruption of someone

else’s meditation stand between me and my comfort, and so for

the first five or six days I averaged perhaps six showers a day.

However, by about the fifth day my meditation had deepened

to a point where I was more aware of the emotional reactions I

underwent during this transgression. What I eventually no

ticed that I was doing was minimizing the effects on me of their

imagined discomfort by creating a psychological distance

between us. To do this I found myself creating feelings of

anger, separation, and superiority toward them so that the

discomforts which I imagined them to be experiencing, I could

now justify, defend against, and even feel righteous about. By

the seventh day this process had become too painful and ugly

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

to watch and I was forced to at least partially give up my

attachment to showers and to resign myself to showerless agi

tation. This devaluation of people who are wronged is consis

tent with cognitive dissonance theory, which is concerned with

the effects of incongruity between expectation and actuality

(Festinger, 1957; Malmo, 1975). If this process is generalizable,

then it obviously holds widespread implications for under

standing the dehumanization which occurs with crime and

warfare.

Using the example above, and I could if necessary present

several others also, it has become apparent that greater inner

sensitivity reveals more clearly the multiple yet often subtle

ways in which we harm both ourselves and others by behavior

which is not marked by authenticity and integrity. Further

more, the reason we act without integrity is to avoid confront

ing and having to possibly give up our attachments. On the

other hand, if we wish to speed up the meditative process of

increasing concentration, insight, and reducing attachments,

then living with as much integrity as possible will bring us up

against the greatest number of attachments in the shortest

possible time. Although this will, of course, be uncomfortable,

it will afford, if we wish, the opportunity of most speedily

recognizing and letting go attachments and hence progressing

most rapidly. This provides a rationale for many of the ethical

precepts of most of the meditation-yogic traditions and seems

analogous to Don Juan’s concept of impeccability (Castaneda,

1971). It also fits with the hypothesis that the more mentally

healthy person will tend to be motivated by approach rather

than escape and avoidance (Walsh & Shapiro, 1978). Certainly

it is apparent that perceptual sensitivity and integrity are both

mutually interactive rate-limiting factors for this process.

living

with

integrity

BELIEFS

As with psychotherapy (Walsh, 1976), the limitations and

self-fulfilling prophetic nature of beliefs and models again

became apparent. Once again John Lilly’s (1972) statement

proved awesome in its power. “Within the province of the

mind what I believe to be true is true or becomes true within

experimental and experiential limits. These limits are further

beliefs to be transcended. Within the mind there are no limits.”

Usually it has seemed that my beliefs and models of who and

what I am seem to lag behind the changing reality and to be

closer to what I was than what I am now. In areas where there

is growth this can be especially limiting because I then find

myself fighting and dealing with an outdated chimera rather

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

165

than acknowledging the reality that is. Although at the present

time it is very subtle and often at the limits of my perception, at

times when I become aware that I have been operating out of a

model rather than out of the current reality, then I am able to

detect the following: Firstly that my awareness is split with a

major portion fixed on the mental model, some sense of repressing the awareness of the here and nqw^ and a sense of

lessening being and flowing and heightened active “doing” to

match the expectancies of the model.

Another limiting belief, derived in part from my Western

psychological and psychiatric training, is that I cannot change

my mental state—e.g., affect, state of consciousness—without

adequately working through all the intervening determining

psychological material; e.g., if I feel guilty, then it is necessary

to work through the determining factors before I can expect to

feel good again. A mere moment’s consideration will show the

inaccuracy of this assumption, but it’s amazing how often it has

caught me and others.

BEING AND DOING

The theme of allowing and “being” versus “doing” has been

a central and recurrent one for each and every retreat. It

gradually became apparent that the sense of doing actually

represents a form of paranoia, a readiness to correct the on

going automatic process of being, for fear that it will be inade

quate or suboptimal. This fear leads to hypervigilant surveil

lance of both the present and anticipated situations and be

havior, coupled with an emergency readiness to deal with any

shortcoming of being. We are thus continuously and need

lessly on emergency alert, derived from a basic pervasive fear

that we will not be sufficient in any moment.

directing

attention

to the stimulus

166

‘ became

most forcefully apparent during

The process of doing

b<

the second retreat, by which time I was attempting to passively

observe as much as possible. However, if any stimulus, of

seemingly greater significance than others came into aware

ness, then I would immediately cease passive observation and

go through a series of stages of first actively directing my at

tention towards the stimulus, secondly focussing on it intense

ly, thirdly attempting to identify it, and fourthly sometimes

to transmute it in some way, e.g., from fear to excitement.

However, by the end of the first week when my mind had

become more sensitive there was an almost continuous stream

of surfacing of “significant” awarenesses. So much so that I

was fatigued and unattracted to working with them and no

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

longer attempted to transmute them. Then with more time I

did not even bother to identify them, next could not even be

bothered focussing on them, and finally could barely raise the

interest to turn my attention towards them. This sequence thus

evaporated in accordance with the sequential loss of the links

of a non-reinforced behavior chain. This fatigue led to an

increased willingness to just be, to just watch, to surrender and

to recognize that I really did not have to do anything with the

contents of awareness. At first this type of trusting was very

difficult, but was necessary out of sheer fatigue, a situation

reminiscent of the spontaneous recovery of some neurotics

who literally wear out their own defenses and themselves. With

time, however, there was an increasing sense of letting go,

surrender, less need to react and to work to change experiences,

and a greater sense of just allowing them to be whatever they

were, e.g., it was ok to be scared rather than having to try to

change it.

One question of both theoretical and practical importance

which comes up repeatedly not only in meditation but in all the

growth disciplines, is whether thought and behavior patterns,

habits, conditioned responses, etc., are ever fully extinguished.

Learning and behavior theory suggests that they follow de

clining asymptotic curves. My own experience suggests that

the same thing happens in meditahom As a behavior pattern is

eradicated at one level this in turn increases perceptual sensi

tivity so that one is now more likely to become aware of it

operating at an as yet uneradicated and more subtle level. This

process can recur many times, each in a more subtle, sensitive,

exquisite, and more difficult to detect manner than the time

before.

different

levels of

behavior

patterns

At my next retreat, some five months after the previous one,

it should have been no surprise to me, although it was, to find

myself amazed and astounded at the amount of “doing” that I

was doing. Whether in fact I was actually “doing” more or

whether 1 was simply more sensitive to it, 1 cannot be certain,

though subjectively it felt more like the latter. In any event by

the second or third day of the retreat it was apparent that a

large proportion of my mental time and effort went into an

active, anxious doing attempt to change the mental contents to

fit a variety of predetermined models. Subjectively it seemed

that a percept, thought, feeling, etc., would arise and would

then be immediately anxiously scanned for its threat value and

to determine how well it matched whatever the relevant model

was of the way it and I should be. The most frequent model

was one of an idealized end state, e.g., happy, clear, perspica

cious, insightful, aware, deeply meditative, etc. Whenever the

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

monitoring

an object

of attention

mental object of attention was found to be lacking in any way,

as surprisingly enough it not infrequently was, then immedi

ately a whole series of corrective measures would be taken to

try to align it with the model. These corrective measures would

include all the psychological, mental, and meditative man

euvers that I had learnt over the previous three years, e.g.,

relaxing, letting go, taking the energy up. attentional focussing,

etc., ad infinitum, ad nauseam, all within the space of seconds

or less. If the corrective actions were successful, then they

would tend to diminish, but if not then they would increase in

intensity and there would be a detectable mounting anxiety.

To complicate matters still further these corrective actions

would themselves in turn be contrasted with specific models of

the way they ought to be, judged, and modified in turn so that

there could literally be chain reactions cascading out in all

mental directions until something else became the focus of

attention.

It felt as though the process I was now witnessing was a faster

and more subtle version of the one I had seen in the previous

retreat where I had initially semiconsciously turned my atten

tion towards and then tried to modify prominent percepts.

Now I was observing the same process at work on larger

numbers of more subtle mental events.

In the midst of this dilemma it felt as though any doing, any

volitional activity, involved an active modification or correc

tion of what was, and only trapped me more in my own reac

tivity. This raises the interesting question of whether doing, as

opposed to just being, is always reactive and therefore always

follows some stimulus, and therefore always adds more con

ditioning and perhaps what might be viewed as karma. This

was certainly the subjective experience and if so would explain

the Buddhist and many other meditative teachings that it is

literally impossible to “do” anything to get oneself out of one’s

mental trap.

“doing

the

right

thing”

168

Similarly my attachment to getting ahead with and speeding

up this process became patently counterproductive. It became

apparent that periods of intense well-being lasting even only a

matter of several seconds, tended to elicit thoughts and con

comitant anxiety along the lines of “but what if I’m not doing

the right thing?” The right thing was of course that maneuver

which would propel me forwards at the fastest possible rate

and which had to be constantly searched and selected for, a

process which could not continue if I was just sitting feeling

calm, peaceful, and happy.

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

Interestingly enough this achievement need also trapped me

in an endless treadmill. It turned out that one of the little

games I was playing with myself to supposedly speed up my

growth was to retrospectively negatively distort my self-image.

Thus the memories of myself and my behavior that I retaineH

across the years, and even across the duration of a meditation

sitting, were negatively tinged and biased. One of the beliefs

out of which this process sprang was that these negative mem

ories would prove aversive enough to provide the motivation

to keep me working on myself as intensively as possible. The

only problem with this was that of course I spent years trying to

chase and correct chimeras, and chimeras turn out to be hard

things to improve, especially when all you have to go on are

negative memories of how poorly you dealt with them last

time. In rereading it, this description of the memory distortion

feels rather gross since the process itself was very subtle,

though not without pervasive effects, so subtle in fact that it

was only in the depths of a retreat that I became aware of the

operation of the mechanism at all. It does seem important,

however, since once having recognized the mechanism, I was

able to see how much of my current behavior is motivated by

beliefs about who I have been and hence am. The awareness

that those beliefs were subject to specific detectable distortions

was a powerfully relieving one.

Associated with doing and “doing the right thing” was, of

course, an incredible amount of judging. This thought was

good, that was bad, this feeling was ok, that was not, this

experience really shouldn’t be allowed into awareness, etc., in

an initially continuous and never ending process in which

things, e.g., thoughts, feelings, etc., actually felt good, bad,

right, wrong, etc. with increasing recognition of it, this process

became quite distressing, since it became apparent that I could

do, think, or feel, almost nothing without being subjected to a

barrage of judgmental reactions, and even judgments of judg

ments. These so clouded my perception as to significantly and

continuously distort it. Now I could understand the words of

Sengstan, the Third Zen Patriarch (Clarke, 1975):

judging

When thought is in bondage, the truth is hidden,

for everything is murky and unclear.

And the burdensome practice ofjudging

brings annoyance and weariness....

Indeed it is due to our choosing to accept or reject

that we do not see the true nature of things.

With increasing mindfulness, however, an interesting change

began to develop in which I became aware of the temporal and

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

169

mental gap between the percept and the judgment. Thus a

thought which originally would have “felt bad” and possibly

ugly and painful was now experienced as “just a thought”

without any particular affect attached to it. Then a small but

detectable time after, there would be a wave of affect corre

sponding to the nature of the judgment, e.g., distasteful affect

for a negative judgment, but this affect was now no longer

identified with the original percept. The original percept, e.g.,

thought, sight, etc., was just whatever it was, and in another

time and space there was an affect which represented a judg

ment. With still greater mindfulness and the passage of time,

the strength of these judgments began to diminish and there

was a slight but detectable sense of things just being a little

more “what they are,” rather than being good, bad, etc.

The range and pervasiveness of this judging process is difficult

to convey, but there were times when I felt almost mentally

crippled by the constant checking, limiting, deleting, and pro

scribing of whole ranges of thoughts and feelings, a process

which formerly had been below the threshold of awareness.

eff°rt

and

achievement

There are several other counterproductive factors involved in

efforting and achievement in meditation. Firstly these motives

seemed to produce agitation and anger, both of which ap

peared disruptive and reduced sensitivity and insight. In ad

dition the attempt seemed somehow intrapsychically splitting

since it had the feeling that “part of me is trying to push

another part which the first part doesn’t trust.” The result was a

subtle but significant sense of dissociation in which I felt aware

of the energy, agitation, and sometimes strength and power,

but also somehow felt very superficial as though I was out

of touch with my deeper awareness, a situation which would

follow, I suppose, naturally from the process of separating my

self from it in order to manipulate it. This seems analogous to

the process of objectification which Bugental (1965; 1976) has

noted to be a common pervasive feature of existential numb

ing.

If you determine your course

with force or speed,

You miss the way of the law.

The Buddha (Byrom, 1976)

PERCEPTUAL RECOGNITION PROCESS

The perceptual process of recognition, categorization, and

naming or labeling a stimulus seems to be important and

central to a number of psychological processes. The process

170

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

seems to be similar for both internal and external stimuli and

to be multiphasic. To date I have managed to identify the

following components. At the first awareness of the stimulus

there is an arousal and an orientation of attention towards it

coupled with an active attempt to recognize it. When the stim

ulus is identified, there may sometimes be a sense of relaxa

tion or alternatively there may be a fraction of a second of what

feels like searching past memories in order to decide how to

respond to it. At this stage more attention is focussed on the

category or label and less on the stimulus itself. This whole

process, however, is markedly susceptible to modification by

meditation and this modification is discussed below. The in

teresting point is that once the stimulus has been identified and

labeled, then habitually most of the responses to the stimu;

lus-label complex are actually determined by the label rather

than the stimulus per se. Thus, for example, if I experience a

feeling which I label either correctly or incorrectly as fear, then

I will tend to respond to “fear” with all its connotations and

associations rather than to the percept itself, which may be so

mild as to warrant very little reaction or may actually have

been misidentified and not be fear at all. However, if it has

been misidentified, I will continue to react to it as though it

were fear unless I choose to go back and reexperience the

feeling directly.

Interestingly the extent of reaction to the stimulus itself as

opposed to the label seems to be a direct function of the degree

of mindfulness or meditative awareness. If I am mindful, then

T tend to be focussed on the primary sensations themselves, to

label less, and to react to these labels less. For example, there

was a period of about six weeks during which I felt mildly

depressed. I was not incapacitated, but was uncomfortable,

dysphoric and confused about what was happening to me

throughout most of the waking day. However, during daily

meditation this experience and its affective quality changed

markedly. The experience then felt somewhat like being on

sensory overload, with many vague ill-defined somatic sen

sations and a large number of rapidly appearing and disap

pearing unclear visual images. However, to my surprise, no

where could I find stimuli which were actually painful. Rather

there was just a large input of vague stimuli of uncertain

significance and meaning. I would therefore emerge from each

sitting with the recognition that I was actually not experiencing

any pain and feeling considerably better. This is analogous to

Tarthang Tulku’s (1974) statement that “The more you go into

the disturbance—when you really get in there—the emotional

characteristics no longer exist.” It is also reminiscent of the

state of affairs in quantum physics. “Our conception of sub

labeling

stimuli

becoming

more

mindful

ofprimary

sensations

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

171

stance is only vivid as long as we do not face it. It begins to fade

when we analyze it.. . the solid substance of things is another

illusion” (Commins & Linscott, 1969). Therefore, it may be

that appearances of solidity and stasis in both the inner and

outer universe are merely illusions reflecting the limitations of

our perception.

However, within a very short time I would lapse once more

into my habitual non-mindful state and when I next became

mindful once again I would find that a powerful regression had

occurred. That is, I would find that I had been automatically

labeling the stimulus complex as depression and then reacting

to this label with thoughts and feelings such as “I’m depressed,

I feel awful, what have I done to deserve this?,” etc. A couple

of moments of relaxed mindfulness would be sufficient to

switch the focus back to the primary sensations and the re

cognition once again that I was actually not experiencing dis

comfort. This process repeated itself endlessly during each

day. This effect of mindfulness or phenomenology and reactiv

ity should lend itself to experimental neurophysiological in

vestigation.

The subjective experience above of the perceptual recognition

process with its initial arousal prior to identification, identifi

cation and sometimes concomitant relief and relaxation, may

represent the subjective analogue of the psychophysiological

phenomenon called the orientation reaction (for reviews, see

Lynn, 1966; Raskin, 1973; Pribram, 1975; Waters, etal., 1977).

the

orientation

reaction

172

This reaction is important at both behavioral and physiological

levels and has been postulated to be a mechanism media

ting environmental effects on brain anatomy and chemistry

(Walsh & Cummins, 1975,1976a,b). As described objectively the

orientation reaction consists of a complex of behavioral and

physiological responses which orient the subject to a stimulus

and increase perceptual sensitivity. The reaction is most read

ily elicited by stimuli which are either novel or of historical

significance to the subject. Sokolov (1960) has proposed a

neural matching model to explain this in which the stimulus

initiates a response in the cortex and this response is then

compared with cortical neural models of previously exper

ienced stimuli. If the stimulus matches any existing neural

model, then the orientation reaction is blocked, but if no match

exists, i.e., if the stimulus is a novel one, then the reaction

occurs. With repeated presentation of the initially novel stim

ulus, habituation of the reaction takes place. This would seem

to fit with the subjective experience above inasmuch as the

initial subjective arousal ceased upon recognition.

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

If the arousal prior to recognition is aversive, as indeed it is

sometimes felt, then an interesting situation arises which may

provide the basis for explanations of psychopathologies such

as paranoia and intolerance of ambiguity. It should be noted,

however, that Sokolov’s model does not explain the activation

of the orientation reaction by familiar but significant stimuli

(Lynn, 1966). Thus the finding as described above, that a major

portion of reactivity is in response to cognitive labels rather than

the percepts which elicit them, is especially interesting since it

would provide an explanation of this phenomenon.

In moments of special clarity it has seemed that the £ecognition

(labeling) of a stimulus is followed by an extremely rapid

process, of recalling how I responded to it in the past, and

choosing a current response. It may be that the existence of this

instant of choice represents a crucial demarcation between

different psychological models of man. Skinnerian behavior

modification at one extreme sees responses as merely choice

less conditioned automaticity. On the other hand, psychologies

which emphasize the importance of cognitive mediating pro

cesses in determining responses—from several branches of

behavior modification (Mahoney, 1974; Thoresen & Maho

ney, 1974; Bandura, 1977a,b), all the way through to trans

personal psychology—recognize and emphasize the existence

of this choice process even though it may normally reside

below perceptual awareness. However, it must be noted that

recognition of this choice process tells us nothing about

whether it itself is merely a conditioned choiceless stimulus

response chain, but rather merely brings the level of observa

tion and analysis to a much finer level.

the

stimulus

response

chain

Subjectively it is clear that habitual interpretation of stimuli

according to expectations, mental set, etc., may lead to misi

dentification. For example, during the anxiety episodes men

tioned elsewhere which occurred most commonly while with

someone that I felt very close to, I initially labeled these as due

to a fear of intimacy. Having done this the process generalized

(stimulus generalization) to situations with other people which

I also began to label as fear of intimacy, where in point of fact

as detailed elsewhere, these episodes actually turned out to be

determined by a number of processes, none of them in fact

related to intimacy. The experiences described above all sug

gest that unconscious labeling and conceptualization is a

highly significant process with far-reaching and pervasive

effects which when performed without mindfulness may cause

a shortcircuiting and misinterpretation of, and loss of contact

with, experience resulting in a limiting automaticity and ster

eotypy. On the other hand, increasing mindfulness may per-

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

173

manently weaken and disrupt misinterpretation, automaticity

and conditioning. “Any label is entrapping, because labels are

limiting, they are finite, they have suffering connected with

them” (Ram Dass, 1977, p. 114).

FEAR

overinterpreting

and

mis

labeling

Fear, in one form or another, was a not infrequent experience

especially during the earlier phases. However, during the sec

ond retreat, the nature of this experience began to change

rather dramatically, and it became apparent that I had been

overinterpreting (misattributing) a number of emotional ex

periences as fear. For example, after the first few days of the

retreat as my mind became a little more sensitive, it became

apparent that there was a whole range of emotional and so*

matic responses which were automatically mislabeled as fear.

For example, the sudden slamming of a door would elicit a

strong sensation in the abdomen and chest which I initially

assumed to be fear, whereas a closer examination of the sen

sation revealed it to be an affectively quite neutral arousal

response.

Similarly it became apparent that many of my reactions, e.g.,

fear, sexual, came not out of an accurate identification of the

primary response but rather out of old expectations about the

way I would react. Thus, for example, a stimulus would elicit

the thought-feeling “I should be scared of that,” followed by

an emotional reaction which was initially labeled as fear but

which on closer examination had a different flavor to it and did .

not actually seem to be fear. This seems to represent a specific

example of the post-stimulus recognition choice point which

was discussed above. It also raises, together with the previous

discussion on depression, the question of whether the actual

sensations underlying any emotion are actually inherently

aversive or whether their aversive quality comes purely out of

the labeling and expectations that we ascribe to them.

the

fear

death

174

One of the major recurrent fears has been of what will

happen to me if I continue on this path. This has manifested

in a variety of ways and provides an interesting lesson in

psychodynamics. Fear of death has been especially prevalent,

especially the fear of death of a particular sub-personality or

personality complex, and this is described in more detail

in Part II. It seemed that this basic fear activated a variety

of more superficial ones in ways which interfered with my

meditation. Thus, for example, there was a period of several

days in which I had intense visual and somatic imagery of

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

having my toenails ripped off, a fear which had lain dormant

since an adolescent reading of Nazi tortures. For several days I

was unable to get past this fear until eventually I went into it

deeply and found myself suddenly experiencing terror that if I

continued with the meditation and did not heed the fear I

would die. A similar process occurred with a number of other

fears, and I gained the impression that a part of my personality,

or what would be called ego in Eastern terminology, was liter

ally fighting for its survival. In doing so it seemed to be acti

vating other latent fears in a way which would interfere with

the meditative process and therefore presumably abet its sur

vival. This has also emerged in more subtle ways such as

procrastination, forgetting etc., suggestive of Freud’s (1914)

“psychopathology of everyday life.” For example at one stage

it became very apparent that to be optimally effective the

meditation procedure or mindfulness was going to have to be

continuous throughout the day. I therefore decided to draw up

a plan of how I could best attempt to work towards this. Some

two months later, after almost daily decisions to get it done that

day, I began to suspect that perhaps I might be exhibiting a

little resistance and so decided to do it that hour. Two days

later I felt pretty confident that I had been right about my

resistance since there was still no plan in existence. Having

decided to do it there and then, within minutes I was in the

middle of a full-blown panic attack and watched myself crying

“No, no, please don’t make me do it, I’ll die, don’t make me do

it, please, please.” At times like this the strength of the resis

tance and defenses against awareness seem remarkably

powerful.

As more and more anxieties were confronted and the feared

catastrophies failed to materialize, there gradually began to

develop a deepening trust in the process. It gradually became

more apparent that fear was certainly not necessarily a reason

to avoid something. Indeed often it served as a useful signal

that here was something which needed looking at and exper

iencing. In addition it became apparent that there was a certain

pattern to at least some of my fears of meditation. Particularly

clear patterns included the fear of becoming amotivational

without a desire to produce, achieve, or contribute to others.

This would come up especially whenever my striving, con

trolling, and obsessional defenses were under examination.

Another factor which assisted this increasing trust was the

recognition that any experience could be used as grist for the

growthmill. Certain experiences were not necessarily any more

growth evoking than others, but rather what was important was

the way they were used. This was a recognition of one of the

major Vipassana precepts that it is the process of mindfulness

a deepening

trust

in the

process

Initial Meditative Experiences: Part I

175

which is important rather than the object, or experience, which

is being observed. This is reminiscent of Rajneesh’s (1975a)

statement that “the only sin is unconsciousness.”

allowing

things

“to betf

With lessening fear and increasing trust came a greater

willingness to allow things to be the way they are. This

transition represents an interesting example of interaction

between meditation and other inputs. Thus my third retreat

was marked by significantly greater “allowing things to be” than

previous ones, and this was almost certainly due to a conver

sation the day prior to the retreat in which a close friend had

pointed out how much difficulty I had in “allowing things to be

as they were” without worrying, thinking, and planning how to

change them. This retreat was marked by a number of new

experiences which felt secondary to this thematic switch. There

was a considerable increase in feelings of peace and a height

ened awareness of the incredible number of models 1 have of

how things should be, and the amount of judgment that goes

along with this.

Finally towards the end of the retreat there was a powerful

experiential recognition that I do not have to try to change any

part of my experiential process. All I need to do is to watch it.

The next thought to follow this was the recognition that to

some extent I had misused what I had learned over the previous

three years of therapy and meditation. 1 had taken the skills

and tools and used them to try to more adroitly change and

manipulate my experience. In terms of the approach-avoid

ance model of health (Walsh & Shapiro, 1978), I had used the

information in order to more skillfully approach and avoid

rather than to transcend this dichotomy.

Paradoxically, allowing an experience to be rather than at

tempting to change it, seemed to modify it in a beneficial

direction. Thus when a percept which I would formerly have

changed now arose and I allowed it to be as it was, e.g., anxiety,

I would not infrequently have a thought such as “this feeling

can’t be too bad if I don’t have to change it,” and as I did,

some of the aversiveness of the percept would be reduced and I

would feel less need to change it.

Several reactions to this increased allowing became apparent

over the weeks succeeding the retreat. There were occasional

eruptions of self-punitive anger and hatred (see the section on

subpersonalities in Part 11) associated with the idea that I had

given up striving and was thus weak and cowardly.

There was also an episode involving the eruption of a number

of what felt like formerly repressed fears. While sitting quietly

176

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1977, Vol. 9, No. 2

I began to experience a familiar fear, and rather than resisting

and attempting to change it as I was accustomed to doing, I

just allowed it to be. Shortly thereafter another fear also arose

and I allowed it also to be there. There then followed an

increasingly rapid eruption of fears until I felt myself to be

physically encased in them to the extent that my body felt stiff

and difficult to move, and I had the visual image of being

completely surrounded by them. It also felt as though it was

the allowing which made it possible for them to erupt and,

interestingly enough, also seemed to serve to minimize my

discomfort. For a while I felt surrounded by and physically

encased in the fears, but I also felt remarkably unperturbed

and continued to observe them with only minimal discomfort.

There was also a gradual but perceptible change in behavior