RF_DR_40_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

B

e

RF_DR_40_SUDHA

Delta

J

I Drug pricing: Centre •*-*-«

r gives ultimatum to cos

I

NEWS NETWORK

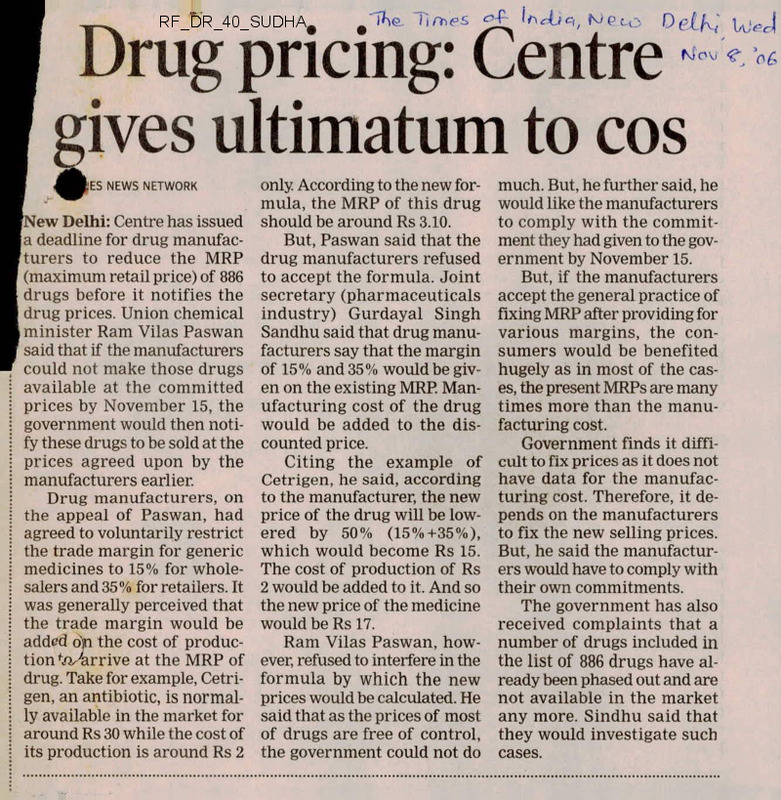

[New Delhi: Centre has issued

I a deadline for drug manufacturers to reduce the MRP

(maximum retail price) of 886

drugs before it notifies the

drug prices. Union chemical

minister Ram Vilas Paswan

said that if the manufacturers

could not make those drugs

available at the committed

prices by November 15, the

government would then notify these drugs to be sold at the

prices agreed upon by the

manufacturers earlier.

Drug manufacturers, on

the appeal of Paswan, had

agreed to voluntarily restrict

the trade margin for generic

medicines to 15% for wholesalers and 35% for retailers. It

was generally perceived that

the trade margin would be

added djn the cost of production <Oz4irrive at the MRP of

drug. Take for example, Cetrigen, an antibiotic, is normally available in the market for

around Rs 30 while the cost of

its production is around Rs 2

only. According to the new formula, the MRP of this drug

should be around Rs 3.10.

But, Paswan said that the

drug manufacturers refused

to accept the formula. Joint

secretary (pharmaceuticals

industry) Gurdayal Singh

Sandhu said that drug manufacturers say that the margin

of 15% and 35% would be given on the existing MRP. Manufacturing cost of the drug

would be added to the discounted price.

Citing the example of

Cetrigen, he said, according

to the manufacturer, the new

price of the drug will be lowered by 50% (15%+35%),

which would become Rs 15.

The cost of production of Rs

2 would be added to it. And so

the new price of the medicine

would be Rs 17.

Ram Vilas Paswan, however, refused to interfere in the

formula by which the new

prices would be calculated. He

said that as the prices of most

of drugs are free of control,

the government could not do

much. But, he further said, he

would like the manufacturers

to comply with the commitment they had given to the government by November 15.

But, if the manufacturers

accept the general practice of

fixing MRP after providing for

various margins, the consumers would be benefited

hugely as in most of the cases, the present MRPs are many

times more than the manufacturing cost.

Government finds it difficult to fix prices as it does not

have data for the manufacturing cost. Therefore, it depends on the manufacturers

to fix the new selling prices,

But, he said the manufacturers would have to comply with

their own commitments.

The government has also

received complaints that a

number of drugs included in

the list of 886 drugs have ai

ready been phased out and are

not available in the market

any more. Sindhu said that

they would investigate such

cases.

I have added points 9 and 10.

If somebody can simplify this (Naveen?), it can go as a press release.

Chinn

Dear friends,

We share with you certain disturbing developments with regards to Drug

Policy which need to be protested against strongly.

Drug Policy and Pricing: Putting the real issues in cold storage. ,Why

these Token Measures Won’t Work

The Government and Mr. Paswan are,announcing measures on 2nd October,

to reduce the prices of medicines. These, are mere sops designed to divert

public attention from the deals being made behind the scenes, and the

calculated delays in announcing the pricing component of the new Drug

policy.

1. The price control component of the policy has been deliberated upon by

committee after committee over the past few years. The Drug Price Control

Review Committee in 1999 toured Europe to discover that price control

exists in virtually all other countries. The pharmaceutical policy in 2002

planned to do away with price control altogether restricting it to less than 30

drugs. A Karnataka High Court Judgement stayed the implementation of the

policy and the final hearing of the case in the Supreme court is still pending.

The various committees appointed by the Government have been in response

to the litigation rather than in response to public interest. The Sandhu

Committee in 2004 was appointed to look at price control mechanisms and

recommended price control over entire categories of essential drugs, which

would have been a welcome step. A task force was later appointed in 2005,

chaired by Dr. Pronab Sen to look at mechanisms other than price control to

ensure availability of drugs at reasonable prices. It mentioned

(uncomfortably for the industry) that price regulation was the only credible

deterrent for the industry. In 2006, we were told about a new policy

formulated by the Ministry after a wide process of consultation and taking

into account the suggestions of the various committees. This policy talked of

regulating the prices of the 354 essential medicines in the National List of

Essential Medicines , which had been submitted to the Cabinet for approval.

This was followed by loud protests not only by the drug industry but also by

the Finance Ministry, and the Commerce ministry. The Health Minister has

maintained a eloquent, sphinx like silence. That India has the highest

number of people in the world who lack access to essential medicines,

because the government does not provide them and the people cannot pay for

them, doesn’t apparently bother^him. After all he has nothing to do with

Deleted: Sops and Tokenism by

Governments]

[ Deleted: is

[Deleted: ,

i Deleted: which

formulation of the Drug Policy, which is formulated by the Ministry of

Chemicals!

I

2. In a democratic country, such loud and vehement protests by the industry,

adequately represented in the media, have obviously to be paid heed to. So

the Ministry of Chemicals has made a 14-member committee to look into the

matter of price regulation again. Of these ll members are from the Industry^

and 3 from the government. This brazen act is a valuable precedent for the

future of public policy making in India; forest policy by timber merchants

association, cement and steel policy by cement manufacturers, housing policy

by Ansals and DLF, retail policy by Ambani and Wal mart, revision of the

Indian penal code by those indicted by law, etc.

3. The central issue with regard to Drugs in India today is their pricing. The

pricing of drugs determines directly which kind of drugs are manufactured,

promoted, and prescribed in the country. And we know that that overpriced,

non-essential, irrational and drugs sell more in this country.1

4. Regulation of the prices of a small number of drugs is the only visible kind of

regulation of the drug industry. The majority of the drugs are outside this list

of price control. In this very price-decontrolled segment, there are huge

variations, explained only by rampant profiteering. J'he government has been

allowing companies to market drugs for mental illness which cost more than 15

times, antibiotics and anti-cancer drugs which cost more than 10 times, and

drugs for diabetes and hypertension which cost more than 5 times other

competitive brands leading to huge windfalls for the companies. Does the

industry or the Ministry of Chemicals, the Finance, Commerce Ministry and the

Prime Minister’s office which are so vehement in their opposition to price

regulation have any credible explanation for this phenomenon? The

Government refuses to recognise, because it doesn’t want to, a fundamental

fact known the world over. A free market does not exist in drugs, where the

fundamental choice of the product is not decided by the consumer but by

doctors, who are heavily influenced by the companies to choose more

expensive preparations. The state of distress under which patients are forced

to purchase medicines does not allow them the freedom to not buy the

products either. A free market means in reality the freedom to overcharge

consumers by exploiting their ignorance and vulnerability and denying the

government any right to intervene.

5. On paper the government is supposed to monitor the prices of the drugs

outside price control and clamp price control wherever the behavior is

abnormal. Yet when the attention of the Chairman of the National

Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority was drawn to the brazen instances of

overpricing, he responded by making the extraordinary point that even in

[ Formatted

[Deleted; se

I

the case of a fdrug which is priced 14 times its competitor, he cannot

intervene unless it can be shown w show that the annual rise in its price was

greater than 20%.

[ Deleted: we can

6. The effort of the pharmaceutical industry is that retail drug prices, should

not be questioned at all, and they should be left to the ‘free’ market.

According to it, drug prices are so finely balanced at the moment that any

regulation would spell catastrophe for the industry. In the current policy,

regulation of a drug’s price means allowing a post-manufacturing allowable

margin of 150-200%

7. The variations in the drug retail prices have already been mentioned. The

industry cannot explain how it is possible for 2 companies to make the same

drug and sell at 10 times the price difference. The industry cannot explain

how it can sell a drug or an injection at a catastrophically low price of even

10% of the retail price , and afford it and yet complain if any attempt to

lower the final retail price to the consumer? 2The industry should explain

howjt sells J drugs to the government at even 5% of the retail price, and

afford it , and , and yet paint these pictures of doom if the MRP is

rationalised? The industry should explain how it can afford to ply doctors

with gifts, cars and air conditioners, host five-star conferences and spend

more than Rs. 5800 crores on drug promotion alone. The reality is that there

is a huge differential between the cost of manufacture of a drug and its retail

price, which is used for huge profits for the industry and trade and for

underwriting the costs of unregulated and unethical drug promotion. The

present largely unregulated system is to the benefit of everyone, except the

consumer who is either ignorant, or powerless.

The minister is putting the much awaited decision to introduce price control

into cold storage, and introduce an entirely token set of steps. He has

constituted an entirely jllegitimate committee made up almost entirely of

industry representatives to deliberate on price control?_,The Tamil Nadu and

Delhi state models of selective tender and pooled procurement have clearly

demonstrated that the drug availability in the public health system can be

vastly improved without massive increases in budget. But rather than talk

about such measures, we are being offered district level drug banks based

on so-called charity by drug companies. In return perhaps for getting the

spectre of price control off their backs, and putting the matter into deep cold

storage, they shall donate medicines worth 0.5% of their turnover, even as

drugs shall continue to be priced at 1000% of their cost of manufacture.,

8. The proposed measure of putting a cap on the margins of, drugs (that is*

those sold under generic names only) which do not comprise any significant

part of the market, is another attempt at denying the truth about drug

prices and obfuscation. The new policy polices the prices of generic-generic

drugs and branded-generics, while leaving the prices of branded drugs

intact. We are being told of upto 70% reduction in the prices of some drugs.

( Deleted: sei

[ Deleted: afford to

Deleted: illegitimate

committee

Deleted:,

Deleted: which they shall do

perhaps over the next ter years.

Deleted: Rather than

implement measures to improve

drug availability in the public

health system

Deleted: based on so-called

charity by drug companies . For

the people in distress, all that is

required now is that they should

be living on the right side of the

poverty line, and should be

certified as living so, and when

they fall ill, send their relative

straight to the district level drug

bank, where drugs contributed

by the industry out of 0.5% of

their turnover shall be available

for their consumption. There

may be of course some delay in

the entire process, but perhaps

his cabinet colleague shall oblige

by announcing free train travel

for those travelling more than

100 km to procure drugs for

their ill relatives. Shall these

banks be open after office hours,

or shall there be automatic drug

dispensing machines? 51

Formatted: Bullets and

Numbering

Deleted: only generic

Which are these drugs, and what is so special about them? And what about

the others, whose prices are not going to come down? These drugs we are

told are the ones which are generic-generic and branded generic.

___ Generic drugs are drugs which are sold under their non-proprietary

name, and not under the trade name. These drugs in India are only a

miniscule part pf the market. JVe challenge the Minister to point out generic

preparations are available easily for the treatment of anemia, tuberculosis,

dehydration, ^hypertension, diabetes or cancer, and are prescribed and being

sold. There are none.

We would ask the Hon 'ble Minister to define in legal terms what is being meant

by branded generics ( a complete misnomer if ever there was one). Can he point

out any such preparation which does not have a brand name ? Then how can it

be a generic?

The so-called branded generics are merely brands which are being promoted

to the chemists. They offer the clearest evidence of the kind of overpricing in

brands that is being allowed, and the fact that the prices of ALL drugs can

be brought down substantially without affecting the reasonable profitability

For example in the case of ciprofloxacin, the retail price of the leading brand

——fc-around Rs. 9 for a tablet of 500 mg. The Delhi state procurement price

for the same drug made by another company , found to be of good quality, is

10 times less. Now another reputed company promotes the same drug under

a_brand B offering it to the trade at Rs, 1.40 paise, but with a MRP of Rs. 7,

Anyone can understand that the conclusion to be drawn is that the MRP of

Rs. 7 or Rs. 9 should be questioned because it is clearly an inflated one and

that should be regulated. However our Government draws a different

conclusion and finds fault with the 400% margin, and is chastising brand B,

while leaving brand A intact. Why should there be a different benchmark for

the price of two brands? Is the government admitting to differences in

quality?

These so-called branded generics have grown as a segment, but still

constitute a tiny minority of the pharmaceutical trade,

JVe challenge the Government to point out a single instance of a branded

generic being a part of the top 300 brands, the sale of which itself accounts for

Rs. 18,000 crores.

---- The drug policy is silent on many issues which are of crucial concern to

the citizens of this country. The policy is silent on the issues emerging from

TRIPS and what safeguards will be used and when to ensure affordability of

drugs. Poor Indians are being converted into guinea pigs for the world in

clinical trials which are being conducted flouting all norms of consent, ethics

and safety. The policy is silent on the issue of irrational drugs and hazardous

—LU_ the Indian market, which no self-respecting drug regulatory

authority in the world would approve of. The draft policy part A, mentions

[ Formatted

[ Formatted

Formatted

)

plans to make India the drug maker of the world, but does not wish to follow

world standards of what constitutes a rational or safe drug. Drug promotion

in_India is completely unregulated and a major contributor to the inflation of

drug prices, , is increasingly turning into bribing to prescribe. There is a

complete lack of availability of unbiased prescribing information, lack of

norms or regulation with regard to prescription quality, and lack of

regulation over the kind of dispensing provided by India’s chemists.

jBut first, the the government’s bluff needs to be called on the issue of drug

prices. ¥

We call upon all members of civil society and concerned citizens of India to

use the means at their disposal to draw attention to the continued cheating of

the consumer in the area of drug prices,, represent matters in the media, ask

Members of Parliament to raise questions on drug policy and the nature of

this committee.

If a common program of protest can be organised in New Delhi over these

developments, AIDAN shall be willing to put its weight behind it

In Solidarity,

All India Drug Action Network.

The top selling brand in India is Corex, a widely abused cough expectorant containing opiods.

Nimesulide, a hazardous drugs, sells more than Ibuprofen. Dexorange with a composition that any

preparation for anemia should never have, is the top selling preparation for anemia. In a country where

chronic hunger is the lot of the majority of the population, appetite stimulants and nutritional supplements,

which cost more than almonds sell for hundreds of crores

‘ 2 years ago, Mr. Paswan announced that the trade margins in the case of 3 drugs investigated by the

Ministry, Nimesulide, Omeprazole, and Cetrizine, were over 1000%. 2 years later, and much media

publicity later, they remain to be so.

[Deleted:

[Deleted: d.

— Original Message —

From: Mira Shiva

To: drdabade@qmail.com

Cc: amol p@vsnl.com ; Prasanna Saliqram

Sent: Sunday, October 01,2006 6:54 PM

Subject: Fwd: Re: drug policy

Mira Shiva <mirashiva(d),yahoo.com> wrote:

Date: Sun, 1 Oct 2006 05:31:25 -0700 (PDT)

From: Mira Shiva <mirashiva@yahoo.com>

Subject: Re:

To: Anurag Bhargava <madhurag bhargava@jediffinail.com>. Anant Phadke <cerd@satyam.net.in>

CC: Dabade Gopal <dabade pal@,yahoo.com>. Chinu <sahajbrc@icenet.net>

Dear Anurag,

The OPPI, IDMA ,FICCI ,CII,Commerce Ministry , Consumer Affairs Ministry ,

Finance Ministry , Planning Commission PM's Office Including the Health Ministry

are all against Price Control. Consumer Affairs & Commerce ministry have objected to

price control because it would negatively affect FDI.

AIDAN.s note against Paswan may strategically not be appropriate may weaken the little

stand on price control that is being taken . We could make supportive statement on Price

control. The Finance Minister has said that decreasing Excise duty would mean

REVENUE LOSS " Paswan is trying to get 50% decrease in excize We should support

decrease in Excize duty on Duty on drugs that are essential & RATIONAL drugs

.NOT FOR NONESSENTIAL .IRRATIONAL DRUGS etc

The 14 member group by Chemical's Ministry to negotiate with the Industry was made

at the behest of PM's Office .Some of the companies have made some positive OFFERs

.the catch would be in what they wangle out of the Govt as a bargain ..

The Data Exclusivity for 5 years was pushed mainly by Dr Mashelkar.

In the AIDAN statement we should add something about the drug policy

ESSENTIALITY & RATIONALITY of the drugs in the market

ACCESS , (EQUITY .DISTRIBUTIVE JUSICE )

QUALITY SAFETY

AFFORDIBILITY

UNBIASED DRUG INFORMATION TO DOCTORS & CONSUMERS

ETHICAL MARKETING PRACTICES

RATIONAL USE OF DRUGS

We should not presume people remember this & it is also important to remind everyone

that THE PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY SHOULD COVER MANY ASPECTS

BESIDES DRUG PRICING .For a country with poor public health services ,80 % drug

purchase of medicines OUT OF POCKET thr NATURE OF DRUGS in the market

becomes all the more important, when the nature of diseases afflicting our people are

Acute Communicable diseases as well as chronic diseases requiring long term tratment

For various reasons the voice ofthe consumer , & peoples voice has been hardly audile .

There are some genuine constraints & some we have created for oursemves .

Anurag do not even wait for JSA , this could with the few additions could go as

AIDAN .

Anurag Bhargava <ma(lhurag_bliargava@rediffmaU.com> wrote:

dear friends,

here is a possible piece from AIDAN which with some modification of content could go on the JSA eforum. Perhaps a press release too can be made,

do send comments.

anurag

Anurag and Madhavi Bhargava

HIG-B 12 Parijat Extension , Nehru Nagar , Bilaspur- 495001 , Chhattisgarh Residence07752 270751/519276

JSS Centre: between 9.30 a.m.to 6 p.m.: 07753 244819

9. The proposed measure of putting a cap on the margins of only generic drugs

(that is those sold under generic names only) does not meet the problem head

on. These generic drugs are only Rs 2000 crores of a total market of Rs

30,000 crores and more. And most (approx 62 percent) of the top-selling 300

drugs in the ORG-Nilelsen Retail audit list are irrational and overpriced. So

can we first get rid of these irrational medicines?

10. The pharma industry does not directly lose if prices of drugs are capped only the trade loses its hefty margins. So the argument that the pharma

industry will suffer has no basis.

Mr. Paswan’s and the government’s bluff needs to be called.

We call upon all members of civil society and concernd citizens of India to use

the means at their disposal to draw attention to the continued cheating of the

consumer in the area of drug prices, represent matters in the media, ask

Members of Parliament to raise questions on drug policy and the nature of this

committee.

If a common program of protest can Ibe organised in New Delhi over these

developments, AIDAN shall be willing to put its weight behind it.

In Solidarity,

All India Drug Action Network.

How are drug prices controlled?

Monday, July 10, 2006, The Financial Express

In keeping with the Supreme Court ruling that all life-saving drugs should remain under price control, the

Union chemicals and fertilisers ministry has drafted a new pharmaceutical policy, proposing to bring most

of the 354 “essential drugs” under price control, in addition to retaining the 74 drugs currently under

control. The SC order had come in response to an earlier policy formulation which proposed to remove the

“rigours of price control” through a reduction in the span of price control. Therefore, the latest move by the

ministry which is yet to be endorsed by other government departments and the Union Cabinet, marks a

reversal of the policy direction. Significantly, the ministry’s move also comes with some con-cessions, fe

takes a Closer Look at the evolution of the country’s drug pricing policy:

How many drugs are under price control and how are their prices controlled?

There are 74 bulk drugs (active pharmaceutical ingredients) and all formulations (medicines as we consume

them) containing one or more of these bulk drugs come under price control. The National Pharmaceutical

Pricing Authority (NPPA) determines the ceiling prices for controlled bulk drugs in intra-industry

transactions and the retail ceiling prices of controlled formulations. This is done under the Drug Price

Control Order (DPCO), 1995, issued under the Essential Commodities Act (ECA).

Ceiling prices are fixed as per a formula that gives 100% mark-up on ex-factory cost of the formulation.

The mark-up covers the manufacturers’ margin and trade margins. There are over 3,500 formulations

containing controlled bulk drugs and so are under price control. These include branded and unbranded

formulations. This is just a fraction of the around 800 bulk drugs and about 60,000 formulations consumed

in India.

In terms of span of price control, the latest estimates say less than 25% of the retail pharma market of Rs

25,000 crore is under control. The constitution of the controlled market in the overall market is considerabh'

larger than their numerical share because price-controlled drugs are mass consumption drugs.

On what basis were the 74 bulk drugs picked for price control?

The drug policy 1986 as modified in 1994, following which DPCO 1995 was issued, prescribed mass

consumption and absence of competition within the therapeutic segment as the price control criteria. In

2002, the government announced a new pharma policy. But the policy’s pricing component was held

invalid by the Karnataka high court which said it violated the spirit of the ECA by proposing to liberalise

price control.

What is the price control criteria in the pharma policy proposed in 2002?

Under it, a bulk drug would invite price control if its moving annual total (MAT) value is over Rs 25 crore,

or if any single formulator has a market share of 50% or more, or if MAT value is between Rs 10 crore and

Rs 25 crore and any one formulator has a market share of 90% or more. Mass consumption and single

player monopoly are tlie criteria, as in the previous (operational) policy, only the thresholds change. If these

criteria were implemented as per the April 2002 market figures, just about 35 drugs would have remained

under price control.

The Supreme Court, however, upheld the high court views and asked the government to formulate a policy

to keep all essential drugs under price control. The government then appointed two committees to examine

the issue of drug pricing: the GS Sandhu committee and a task force headed by Pronab Sen. It also prepared

a national list of 354 essential drugs.

What did these panels say?

The Sandhu panel proposed caps on wholesale and retail trade margins—10% and 20%, respectively, for

branded drugs and 15% and 35% for unbranded ones.

The Sen panel, mandated to suggest ways other than price control to reduce drug prices, said the prices of

314 essential drugs should be regulated through ceiling price based on the weighted average of the top three

brands by value. It argued against price control on bulk drugs and unbranded formulations and said

essentiality should be the sole criterion for price control. It also recommended compulsory pre-marketing

price negotiation for patented drugs.

What does the latest policy draft say?

It proposes to bring almost all the 354 essential drugs under price control, besides retaining control on the

74 DPCO drugs. The draft policy proposes continuance of cost-based price control. However, there won’t

be fixation of prices of bulk drugs as at present.

The rigorous inspection-based system for costing of bulk drugs would be replaced by a liberal system based

on market data. Also, Mape would be increased to 150% from 100% in case of controlled drugs. As for

drugs developed out of indigenous R&D, Mape would be even higher at 200%.

http://www.financialexpress.com/fe_full_story.php?contentjd=l33363

People's Democracy

(Weekly Organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) Vol. XXV No. 13 April 01, 2001

Decontrol of Drug Prices

Amit Sen Gupta

THE wolves are baying at the door, once again calling for further decontrol in the prices of drugs. Since

comprehensive price controls were imposed on drugs in 1979, drug companies have continuously

clamoured for their removal. It is a measure of the clout that these companies exercise, that over the years

they have regularly managed to extract their pound of flesh from the government. Thus successive price

control orders of the government have whittled down both the span of price control and the limits on

profitability.

Thus, in 1979, a total of 343 drugs—accounting for 85 per cent of drugs in the market—were placed under

price control. Profitability allowed on price controlled drugs ranged from 40 per cent to 75 per cent. In 1987

the number of controlled drugs were reduced to 166 - covering 60 per cent of drugs in the market, and

profitability allowed was increased to a range of 75-100 per cent.

In 1995 the number was further reduced to 74 - covering 35 per cent of the market, and profitability

allowed was hiked up to 15 per cent. At each point when price control has been reduced, there has been an

immediate spiralling effect on the prices of drugs. And each time this has been preceded by loud wails from

the Pharma industry about declining profitability—a claim however that has never been borne out by the

health of the balance sheets of the pharma sector.

This time around, the tone for further price decontrol was set a couple of years back by the then Finance

Secretary Sri Vijay Kelkar, who publicly held forth on the need to free the industry of all price controls.

The recent announcement by Sri Yashwant Sinha in his Budget speech of further price decontrol of drugs,

hence, was on expected lines. It is expected that only a handful of drugs will now remain under price

control, and this is bound to fuel rise in drug prices. This time, though, the plea of poor profitability for drug

companies has not been used. Possibly because, given that all major news channels these days discuss share

prices at great lengths, it would have been difficult to conceal the fact that Pharma shares have remained the

most profitable even when there have been dizzy gyrations in the stock market.

Instead the rationale now being used to justify price control is two pronged—one that market forces are bsst

suited to stabilise drug prices, and two that the industry must be made more profitable in order for it to

increase investment on R&D and be globally competitive. Both these arguments are seriously flawed, and

are being used to justify the unjustifiable. Let us examine both these arguments.

DRUG PRICE CONTROL IS A GLOBAL PHENOMENON

It is important to underline that drug prices are controlled by differing mechanisms all over the world,

including in developed capitalist countries. In Australia since 1993, new drugs with no advantage over

existing products are offered at the same price. Where clinical trials show superiority, incremental cost

effectiveness is assessed to determine whether a product represents value for money at the price sought. In

Britain, there exists the pharmaceutical price regulation scheme - a voluntary agreement between Britain’s

Department of Health and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry in which companies

negotiate profit rates from sales of drugs to the National Health Scheme.

Globally, Drug Companies are being forced to reduce the cost of medicines. Pressure is being mounted by

Health Insurance Cos, Health Management Organisations (HMOs) and governments (in countries like UK

and Canada where the State provides Health Insurance cover) all over Europe and North America. These

pressures have become stronger in recent years with the realisation that spiralling Drug costs are making

Health insurance cover (whether state funded or privately managed) unsustainable. In all these countries

there is a major move to insist on generic prescription in most cases, thus opening up a huge generics

market. Large TNCs are forced to compete on more or less equal terms which a large number of lesser

known Cos, and also sell drugs at relatively cheaper rates. In the US, for example, from 1995 through 1997,

generic (i.e. drugs without brand names that are produced by small companies and are cheaper) drug prices

showed a double-digit rate of decrease. This shift was facilitated by the Hatch-Waxman Act, which made

the approval process of generic drugs much easier. Since 1984 this has resulted in a dramatic increase in

competition from generic drugs, leading to an estimated saving of 8-10 billion dollars in 1994 alone.

The fact that drug prices are controlled all over the world flows from the global experience that market

mechanisms cannot be expected to stabilise prices. Various other interventions are needed to manipulate the

market, in order to guard against monopolies emerging. Unlike in the case of consumer goods, there is no

direct relation between the market and consumers in the case of drugs. Drugs are purchased by consumers

on the advice of doctors or chemists.

Consequently, the marketing strategies of drug companies target doctors or chemists. Doctors are not

known to take decisions based on price of contending brands. Similarly chemists have no interest in selling

cheaper brands. So, if we believe that drug prices will be kept low by market competition, it is a belief that

is not borne out by the past experience, in India or elsewhere.

Here, it is necessary to nail another lie. There is a prevailing myth that drug prices in India are the lowest in

the world. This is at best a partial truth. Drugs, which are still Patent Protected, are much cheaper in India

due to India’s earlier Patent Act. It should be obvious that we will lose this advantage after amendment of

the Indian Patent Act of 1970. But off-Patent Drugs (which anyway account for 80-85 per cent of current

sales in the country) are not necessarily cheaper in India. In fact, generally, Drug prices for these Drugs are

higher in India than those in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. In fact prices of some top selling drugs are higher

in India than those in Canada and the UK. Thus, clearly, the benefits of the advantage that the Indian Drug

Industry enjoys over all other Third World nations, in terms of the availability of indigenous technology and

a large domestic market, have not been passed on to the consumers.

FALSE PROMISE OF GREATER R&D ACTIVITY

Let us now turn to the argument that price decontrol is necessary to spur R&D activities in the drug

industry. When legitimate concerns were raised that amendment of the Indian Patents Act would result in

rise in Drug Prices, the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilisers had consistently claimed that any rise in prices

would be kept in check through mechanisms in the Drug Price Control Order. It is extremely surprising that

now that amendments are being made in the Indian Patents Act, we should be simultaneously talking of

diluting Price Controls-. Any further dilution would mean virtual abandonment of Price Controls. If the

government is to consider this, under the garb of encouraging R&D, it will only substantiate earlier fears

that a change in the Patents Act can only lead to a spiralling rise in prices of drugs.

Present investments on R&D in the Drug Industry is less than 2 per cent of sales. The dubious logic that

price controls have led to this situation has been put forward. In the past two decades the span of price

controls has come down from in excess of 85 per cent of the Industry’s turnover to around 35 per cent. If

reduction in price controls is to spur R&D activity, why has there been no rise in R&D expenditure in the

past decade. It may be recalled that the 1995 policy had a provision for keeping all drugs developed by

indigenous R&D outside price controls for ten years. This too does not seem to have spurred any significant

R&D activity in the Industry. The issue of Price Controls has nothing to do with infrastructure development

for R&D, and the two issues need to be dealt separately. It appears as though the issue of R&D has been

used as a red herring by drug companies to lobby for price decontrol and thereby licence to profiteer.

A major constraint for the Drug Industry in India is the relatively small domestic market (compared to our

population). The solution to this constraint cannot be sought within the industry, as it has to do with the

extremely low purchasing power of over 80 per cent of our population. The belief that it is possible to

extract significantly larger amounts of’’surplus" as profits from the domestic industry, that can be

channelled for R&D, is thus fallacious.

WHY DO WE NEED A DRUG INDUSTRY?

Finally, we need to understand that drugs are a commodity that are required most crucially by those who are

least likely to be able to pay for them. Unlike commodities like cars or washing machines, the whole logic

for the existence of the Industry lies in its ability to provide its products to the people who are economically

deprived. If the Industry fails in this fundamental endeavour, the very reason for its existence is open to

question. We already have a situation where a majority of our population does not have access to drugs,

because they cannot afford to pay for them. In such a situation rise in drug prices can only "cost out" larger

sections of the population. It can then legitimately be asked, if those who require drugs the most are going

to be unable to afford drugs, why have a drug industry at all? The industry argues that adequate

competition, even in the absence of price controls, can peg down drug prices. If that is so, why are they

afraid of price controls?

http://pd.cpim.org/2001/april01/aprill_snd.htm

Few takers for drug cos’ claim on prices

P.T. Jyothi Datta

The Hindu Business Line, Monday, Feb 11, 2002

ATTEMPTS by pharma companies to allay fears of drug price rise on the ground that the market would be

the leveller are not gaining currency with consumers.

A reduced price control regime being imminent, following the recent Drug Policy 2002, consumer forums

are not buying the arguments by pharma majors that competition would stabilise the cost of medicines.

Drawing parallels from the inflationary trends in the basket of essential drugs, following the announcement

of the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO-1995) — the Delhi Science Forum (DSF) is sure of a price

escalation in medicines, this time around too.

Dr Amit Sengupta of DSF told Business Line, "The revised DPCO will be followed by similar inflationary

trends, since the principles applied to reduce the span of control are the same.”

Citing from the insights of a DSF study post-DPCO (1995), the DSF discounts the theory of increased

research and development (R&D) investments by pharma companies following reduced controls.

"In the past, price controls were slashed from 166 drugs to 74. In the last decade, it was diluted to about 30

per cent of the market to spur R&D activity. But R&D investments in the drug industry is still less than 2

per cent of sales," he said.

On the market ironing out prices, the DSF observed that since drug companies targetted doctors and

chemists to sell, the latter were under no compulsion to sell the lowest selling drug to the consumer. "The

market is too rigged and flawed to be seen as leveller," an analyst observed.

The DSF study also revealed that the top selling brand in a particular formulation was not the cheapest one

as borne out by a comparative cost of top selling drugs, as per the ORG Audit-Nov 1997.

It was found that Cifran (ciprofloxacin from Ranbaxy) cost 100.12 percent more than the cheapest brand in

its category.

Similarly, Norflox (norfloxacin from Cipla) and R-Cin (Rifampicin from Lupin) were 128.93 per cent and

163.52 per cent higher than the cheapest drugs in their segments.

A comparative study of drug prices between February 1996 and October 1998 found that the price increase

for drugs under price control was negligible, while prices for drugs out of control were up by an average

14.94 per cent.

Sporidex was up from Rs 54.25 in 1996 to Rs 61.10 in 1998; Digene was up from Rs 16.55 to Rs 27.10;

Crocin went up from Rs 3.89 to Rs 5.88. Using this as a touchstone, the DSF infers that medicine prices are

expected to increasingly and silently creep up, as against a one-time escalation.

The forum dispels as "myth" the contention that India had low drug prices. "It is higher than Sri Lanka,

Bangladesh, Canada and the UK", he said. In the UK and Canada, the health management organisations

moderated drug prices and in the countries, such as the US, the health insurance agencies acted as

arbitrators.

In India, however, the only regulating mechanism was on its way to complete dismantlement, come 2005,

in line with the WTO commitments, an analyst pointed out.

http://www.blonnet.com/2002/02/ 11 /stor i es/2002021101230100.htm

Pharmabiz.com

New Pharmaceutical Policy A savage attack on healthcare and a licence to profiteer

Friday, March 15, 2002 11:16 1ST

Amit Sen Gupta

The new Pharmaceutical Policy 2002 cleared by the Cabinet is a savage attack on healthcare in the country.

Though it has been termed as a "Pharmaceutical Policy", the new changes are only aimed at allowing a rise

in drug prices. This has been done at the behest of pharmaceutical companies, who have been given further

license to profiteer at the expense of the sick and the ailing. All other elements in the Policy are mere

w indow dressing to justify the price hike.

It may be recalled that in 1995 the number of Drugs under price control had been slashed from 166 to 74.

This had led to an immediate spiral in drug prices. The; new policy has further reduced the number of drugs

under Price Control to just 38.

Myth of Low Prices

There is a prevailing myth that drug prices in India are the lowest in the world. This is at best a partial truth.

Drugs that are still Patent protected are much cheaper in India due to Indians earlier Patent Act. It should be

obvious that we would lose this advantage after amendment of the Indian Patent Act of 1970. But off-Patent

Drugs (which anyway account for 80-85% of current sales in the country) are not necessarily cheaper in

India. In fact, generally, drug prices for these drugs are higher in India than those in Sri Lanka and

Bangladesh. In fact as Table 1 shows, prices of some top selling drugs are higher in India than those in

Canada and the U.K.

The above raises the important fundamental issues that the benefits of the advantage that the Indian

Pharmaceutical Industry enjoys over all other Third World Nations, in terms of the availability of

indigenous technology and a large domestic market, have not been passed on to the consumers.

International Cost Comparison of Drugs

BNF J

MIMS

(UK) |

(India)

”“£89''""“

Amoxycillin

250 mg

2.59

Ampiciiiin

250 mg

~ 3.18

2.42

Erythromycin

250 mg

2.87

3.28-4.17

Cephalexin

250 mg

7.74

4.46 _

IPropanolol

40 mg

0.25

1.39

Atenolol

50 mg

2.65

1.29

Prednisolone

10 mg

1.5

1.09

1.32

Paracetamol

500 mg

T.25..... . 0.32

Haloperidol

0.25 mg

0.13

1.6

0.55

”’ 0.5

Phenobarbitone

30

mg

______

0 25 T 0.28

BC ~ British Columbia Children"s Hospital Formulary

No.35, MarchT998

MIMS - MIMS India, March 1998

(Single units - tab./Cap./vial - has been taken fcTal^^

India Rupees (Rs.). Rough conversion rate is : 1 U.S.dollar = Rs.42.50 1

Canadian Dollar = Rs.25.00, 1 British Pound = Rs.70.00)

Drug Dose

BC

(Canada)

1.75

1.75

1.25

3.00

.... 1.25....

°-49

Single units - tab/cap/vial - has been taken for all drugs. Prices are in Indian Rupees. Conversion rateis

$1=42.52, 1 Canadian dollar = Rs25, 1 Pound = Rs 70.

Source: British Columbia Children”s Hospital Formulary, British National Formulary, No.35 March 1998

MIMS India, March 1998

Decontrol leads to price rise

In the New Policy, in one sweep, the volume of pharmaceuticals under price control has been reduced from

an estimated 40% to below 25% of the total drug market. There has been no attempt to provide even the

semblance ofjustification for the decontrol of drug prices. Earlier studies have clearly shown that prices of

drugs start rising as soon as controls are removed. This was evident in 1995-96, after the last round of price

decontrol effected through the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO) 1995. Further, in almost all segments, the

brand leader for a particular drug (i.e. the Brand with the highest turnover) is usually one of the most

expensive (in some cases twice as expensive!). This flies in the face of the argument that market forces and

competition stabilises drug prices. If a more expensive brand sells more in the market than cheaper

alternatives, it should be evident that the price of a drug does not determine its volume of sales.

This is so because market mechanisms are notoriously ineffective in stabilising prices of drugs, as there is

no direct interaction between the consumer and the drug market. Companies are able to sell over-priced

drugs through aggressive promotional strategies aimed at doctors and by providing lucrative margins to

chemists. 1 he Governmenf's claim, hence, that market forces shall prevent price increase is fraudulent. It is

even more surprising that pharmaceutical companies have been provided this windfall when even a lay

observer is aware that pharma stocks have been some of the most robust in the stock market.

Market mechanisms do not stabilise prices

It is precisely because of this phenomenon that practically all countries in the world have mechanisms to

control drug prices. Controls on Drug Prices are exercised in many Market Economy countries. In spite of

strong Patent Protection, there are effective measures in place that allow regulation f Drug Prices. In

Australia since 1993, new drugs with no advantage over existing products are offered at the same price.

Where clinical trials show superiority, incremental cost effectiveness is assessed to determine whether a

product represents value for money at the price sought.

In Britain, there exists the pharmaceutical price regulation scheme - a voluntary agreement between

Britain"s Department of Health and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry in which

companies negotiate profit rates from sales of drugs to the National Health Scheme.

Globally, drug companies are being forced to reduce the cost of medicines. Pressure is being mounted by

Health Insurance Cos., Health Management Organisations (HMOs) and Governments (in countries like

U.K. and Canada where the State provides Health Insurance cover) all over Europe and North America.

These pressures have become stronger in recent years with the realisation that spiraling Drug costs are

making Health insurance cover (whether state funded or privately managed) unsustainable. In all these

countries there is a major move to insist on generic prescription in most cases, thus opening up a huge

generics market. Large TNCs are forced to compete on more or less equal terms with a large number of

lesser known companies, and also sell drugs at relatively cheaper rates. In the U.S., for example, from 1995

through 1997, generic drug prices showed a double-digit rate of decrease. In the U.S. this shift was

facilitated by the Hatch-Waxman Act, which made the approval process of generic drugs much easier. Since

1984 this has resulted in a dramatic increase in competition from generic drugs, leading to an estimated

saving Of $8-$l0 billion in 1994 alone.

Thus, it needs to be understood that market mechanisms alone cannot be expected to stabilise prices.

Various other interventions are needed to manipulate the market, in order to guard against monopolies

emerging.

Red Herring of R&D

I he new pol icy has attempted to justify the price decontrol with the plea that this shall boost R&D

expenditure in the pharmaceutical sector. When concerns (legitimate in our view) were raised that

amendment of the Indian Patents Act would result in rise in Drug Prices, the Ministry of Chemicals and

Fertilisers had consistently claimed that any rise in prices would be kept in check through mechanisms in

the DPCO. It is extremely surprising that now that we are moving towards a Product Patent regime (the

amendment to the patents Act ispresently pending in Parliament), there should be talk of diluting Price

Controls. Price Controls have already been diluted in the past decade and only 40% of the turnover of the

Industry was under Price Control prior to the new policy. Any further dilution would mean virtual

abandonment of Price Controls. If the Govt, is to consider this, under the garb of encouraging R&D, it will

only substantiate earlier fears that a change in the Patents Act can only lead to a spiraling rise in prices of

drugs.

Present investments on R&D in the Drug Industry are less than 2% of sales. The dubious logic that price

controls have led to this situation has been put forward. In the past decade span of price controls has come

down from in excess of 60% of the Industry"s turnover to around 30%. If reduction in price controls is to

spur R&D activity, why has there been no rise in R&D expenditure in the past decade? It may be recalled

that the 1995 policy had a provision for keeping all drugs developed by indigenous R&D outside price

controls for ten years. This too does not seem to have spurred any significant R&D activity in the Industry.

The issue of Price Controls has nothing to do with infrastructure development for R&D, and the two issues

need to be dealt separately. It appears as though the issue of R&D is being used as a "red herring” by drug

companies to lobby for price decontrol and thereby license to profiteer.

Millions "Costed Out”

Pharmaceuticals have another unique characteristic - those who need drugs most are the least likely to be

able to pay for them. Thus even a small increase in prices results in the "costing out" from the market of a

large number of people. In a country where half a million people die of Tuberculosis - a disease that can be

treated by over a dozen drugs - because drugs are unaffordable, such a license to profiteer is inhuman.

The imminent rise in drug prices comes at a particularly unfortunate juncture. The public health delivery

system is in shambles and large parts of it are being dismantled or privatised. Drug supplies at public health

facilities are at an all time low. This has already forced poor consumers to pay for medicines even if they

are being treated in public facilities.

Any further price rise can only push such patients to the brink of penury. It is significant in this context that

the Pharmaceutical Policy is announced by the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers. Does the Ministry of

Health believe that Drugs are mere industrial products?

Not a Pharmaceutical Policy

Finally, it is a moot point whether the recent policy that has been cleared by the Cabinet Committee on

Economic Affairs can be called a Pharmaceutical Policy. A Pharmaceutical* Policy has to start with the

premise that Drugs are not like any other industrial products or consumer goods. Unlike say, washing

machines or cars, availability of affordable drugs may make the difference between life and death for

millions of people. A pharmaceuticalpolicy, thus, has to address the issues of quality, indigenous

manufacture, availability of essential drugs, review of existing irrational and hazardous drugs, and

affordability of drugs that are available. The new policy does not address any of these. An estimated 50% of

drugs in the market are irrational, or hazardous, or sub-standard.

De-industrialisation has increased in the drug industry at a frightening pace and many companies are

dependant on imported bulk drugs. Imports of finished formulations have increased by 420 per cent in the

past year! Clearly the new "policy" is only a ploy to allow profiteering at the expense of people's health.

The timing of the new policy is also significant - it has been announced when the country's Parliament is

not in session. It appears to be a deliberate, all too familiar attempt, to bypass democratic processes in the

country. It is hoped that the unjustified attack on people’s right of access to affordable medicines will be

debated in full in the coming session of Parliament.

http://www.pharmabiz.com/article/detnews.asp?articleid=l 1395§ionid=46

Liberal Pharma Policy for Whose Benefit?

Wednesday, April 24, 2002 I 1:16 1ST

Amit Sen Gupta

I couldn t help being both amused and disappointed by Mr. Gopakumar Nair"s reactions to my small note

on the New Drug Policy (Pharmabiz, March 21). Amused because the reactions are so predictable.

Disappointed because we would expect the "Indian" Industry, at least, to be more responsive to people"s

needs and peoples concerns. Drugs are not like cars or washing machines. In the case of drugs those who

need them most are the least likely to be able to pay for them. It is precisely because of this that pricing is

such a major issue. If high process cost out a majority of people from the market, there is no point in having

an indigenous pharmaceutical industry in the country.

International Price Comparison

Let me turn to the points Mr. Nair raises in his rejoinder. The first point is easily taken care of. Let me

assure Mr. Nair that 1 am aware that different countries in the world use different currencies. In my note the

note on conversion had been inadvertently missed. For readers who may have been impressed by words like

"misinformation" and "chaotic figures" used by Mr. Nair, the Table should read as follows: (see table

above)

That, I hope takes care of any confusion that may have been created and readers can draw their own

conclusions!

High Trade Margins Responsible for High Prices?

Mere statements asserting that high taxes, duties and trade margins are responsible for prices in drugs bein"

higher in India than in neighbouring countries are unacceptable. High taxes and duties on medicines is a

matter of concern in most developing countries. I would welcome an initiative by the Indian Industry, in

partnership with public interest groups, to press the Government for a review of the duty and tax structure.

However I would insist that the Industry also appear to be seriously interested in lowering drug prices by

taking other necessary measures. Mr. Nair talks of high trade margins. There are a large number of

instances where the same company sells generic drugs to wholesalers at one-fifth or less of the price at

which their branded products are marketed. The readers are free to draw their own conclusions as to who is

crucially responsible for hiking prices of drugs. May I underline here that the entire marketing system of

drugs in the country is designed to benefit BOTH the manufacturer and the wholesaler/ retailer. It is a

system that has been arrived at for their mutual benefit, disregarding the interests of consumers. The

industry is a captive to the demands of those involved in trading of medicines because it survives on

aggressive promotion of its products, and needs them for its own survival.

Misinformation on Low Drug Prices

Any confusion that may exist regarding rise in prices of patented and off-patent drugs is in fact an Industry

creation. It is the Indian industry that has for long asserted that Indian drug prices are the lowest in the

world - an assertion, unfortunately, that has been unquestioningly accepted by most. This is a contention

that we have always disagreed with. It is the Industry, which has repeatedly used figures regarding global

process of on-patent drugs to try to prove that Indian drugs are much cheaper. As my earlier note had

pointed out, this kind of selective use of figures deliberately hides the fact that off-patent drugs in India are

often more expensive, not only in developing countries, but aso in some developed countries. This is of

serious consequence because off-patent drugs account for more than 85% of the volume of drugs sold in the

country.

It is precisely because of this that we feel that tying up the issue of price-controls with change in the Patent

Act is illegitimate. What Mr.Nair is essentially saying is : allow us to make more profits (some would read

it as profiteer) and we will develop new drugs. It is because we had anticipated such an argument from the

industry that we had said that a change of the Indian Patent Act will be used as an excuse to decontrol drug

prices further and thus the amendment of the Indian Patent Act would lead to a hike in prices of off-patent

drugs too. Nr Nair"s assertions have only confirmed our worst fears in this respect.

Research and Development

Promising trends" notwithstanding the total R&D expenditure as a percentage of sales turnover has shown

little increase. Tying up price decontrol with the requirement to increase R&D expenditure suffers from the

pitfail that higher profits allowed to manufacturers do not necessarily translate into higher R&D

expenditure. We hold that in order to spur R&D activity the Government has to play a proactive role and

pledge resources for such activity. Global experience shows that private R&D expenditure always follows

public expenditure. We find the new drug policy entirely deficient in this respect - a 150 crore fund is a joke

for any country seriously considering the prospect of emerging as an R&D superpower!

Local Manufacture

I totally puzzled by the argument that price decontrol will promote local manufacture. Price decontrol

affects formulations - how will this promote bulk drug manufacture? Mr. Nair is of course correct (and

honest) when he says that an "open policy" helps industry. What he has not said is that it helps the industry

make profits and satisfy its shareholders. But then it would not require a genius to deduce that! But drug

manufacture, I assume, is done to remedy diseases. If drugs are too expensive for those who require them,

why do we need an industry at all?

WTO and the Industry

I am glad that Mr.Nair agrees with me on something - that the present situation has resulted in high import

dependency. I am not interested in even discussing how self-reliant we are in production of formulations.

India is not a Banana Republic, and I start from the premise that self-reliance means self-reliance in bulk

drug production. The question is not which government is responsible for the WTO regime that is in force.

The question is whether the government of the day and its policies are doing enough to protect indigenous

industry. Mr.Nair takes resort to the tired TINA (there is no alternative) slogan.

I fear that large sections of the Indian Industry are not even interested in manufacturing any more. They are

comfortable in being traders because their profits come from selling formulations, not from manufacturing

bulk drugs. Yes, the WTO regime has made the situation difficult for bulk drug manufacturers. But do we

see the same level of interest in this issue within the Industry as we see on the issue of price controls? We

need to seriously engage in a debate regarding how to counter the problem ofcheap imported bulk drugs.

Can we not think of a cell within the industry that works on anti-dumping measures? Can we not think of

measures to make bulk drug manufacturing more competitive?

Non-Intersecting Concerns

The last argument that Mr Nair has used really lets the cat out of the bag. He cynically asserts that the

situation of wide price variations for the same drug is something, " we must be prepared to deal with and

live with in an open market society". Who has to be prepared to do so? The Industry has no problems with

it, because it stands to gain from such instances of blatant profiteering. But the people of this country

certainly are not prepared to live with it. They, furthermore, do not require to be preached to on the merits

of an "open market society" by an industry that wishes to put profits over their misery. Clearly we are

talking of two non-intersecting sets of interests. I am disappointed because it need not necessarily be so. It

is possible for the industry and consumers to work together, at times, to their mutual benefit. But for that the

industry needs to show some sensitivity towards the needs of consumers.

http://www.pharn-iabiz.com/article/detnews.asp?articleid=11400§ionid=46

‘We don’t need no price control’

Drug companies chorus against Cabinet’s prescription

Amit Shanbaug

Mumbai. The Indian pharmaceutical industry has expressed its extreme displeasure at a proposed policy

that aims to control drug prices.

Slated to come up before the Cabinet for discussion soon, the new policy has the CII National Committee

on Drugs & Pharmaceuticals concerned that if and when it is implemented, it would have a disastrous

impact on the pharmaceutical industry and even the country as money for R&D would be reduced.

Ajay Piramal, Chairman of the CII committee and also the Chairman of Nicholas Piramal Limited, stated

that drug manufacturers spend only 5 per cent of their turnover on research & development (R&D) while

their foreign and MNC counterparts spend 15 to 20 per cent on the same.

It is necessary to increase investment on R&D for making medicines at affordable prices to consumers,” he

said.

He also added that despite inflation, in the last four years, the cost of 539 drug formulations have actually

dropped by nearly 5 per cent due competition and increased research.

Indian prices lowest in the world

Ranjit Sahani, Managing Director of Novartis Limited, pointed out that the prices of drugs in India are

lowest and it should be left on competition to decide pricing.

Over the years, due to Excise Duty and Value Added Tax, our margins have been decreasing. Now if the

government puts in a price control mechanism, margins would be further decreased directly affecting and

‘demotivating’ R&D,” he said.

At present 74 drugs comprising of 30 per cent of formulations are under a controlled price policy. If the

new drug policy comes into force, 354 drugs comprising 80 per cent of formulations be covered.

A drug’s cost is only 15 pc of the price

According to Kewal Handa, Managing Director of Pfizer India Limited, the industry had given a lot of

options to the government in the past wherein they could have procured medicines at just 50 per cent of the

price for hospitals.

We are yet to get any confirmation on that,” he revealed while adding that drug prices make just 15 per

cent of the health costs in the country where as taxes, hospitalisation costs and transportation of the patient

adds up to remaining 85 per cent. “The remaining costs can be eliminated if a focused study is done on how

to procure effective drugs,” he said.

http://www.mumbaimirror.com/nmirror/mmpaper.asp?sectid=13&articleid=71 820062231362037182006223034640

Drug Companies Up In Arms Over New Pharma Policy

Wednesday, July 19, 2006; Posted: 12:09 AM

RTTNews) - The government of India firmed up its stand on drug pricing by re-emphasizing its proposal to

bring 354 formulations under price control from the current 74. The policy is likely to go for Cabinet's

approval soon, according to media reports.

The country s pharmaceutical industry, under the aegis of the Confederation Indian Industries, came

together to oppose the policy and asked the government not to proceed on the draft drug policy in the

present form.

Novartis, the Swiss group and Nicholas Piramal, an Indian rival, are leading the revolt against moves they

claim would strangle margins, discoursing expansion into rural areas and could affect quality.

Meanwhile, the department of chemicals, which takes care of pricing regulations for medicines and

pharmaceuticals, stressed that the prices of generic drugs would be monitored. It also said the government

would ensure that they maintain the prescribed trade margin of 15% for wholesalers and 35% for retailers.

Satwant Reddy, secretary, department of chemicals, announced that vaccines, biologicals and non-branded

drugs would be exempted from the price control regime. Similarly, drugs, which have a maximum retail

price of Re. 1 or less, and drugs and other medical utilities procured in bulk by hospitals, would also be kept

out of the price regime, she said.

http://www.tradingmarkets.com/tm.site/news/ASIAN%20MARKETS/309673/

19 Jul 2006

Expanding Price Control Detrimental for Pharma Companies: CII

Expressing concern over the proposal to expand price control from 74 to 354 drugs in the proposed national

pharmaceutical policy, industry chamber CII today said the step will prove detrimental to the growth of the

industry as well as the economy.

"Healthy competition between pharma companies already ensures reasonable pricing. Instead of affecting

the growth by over regulation, it would be better to allow market forces to determine prices," CII’s National

Committee on Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Chairman Ajay Piramal told reporters after a meeting with the

committee members here.

The committee suggested that the government should maintain 'status quo' on the current 74 bulk drugs

under cost based price control and effective monitoring of the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM)

drugs to control any abnormal price increase.

It also proposed to allow government agencies to procure at a ceiling price of 50 per cent of MRP

voluntarily and provide adequate incentives for R&D oriented Indian companies.

"Any sudden regulatory shocks like increased price contro would be detrimental to the industry and the

economy," Piramal said.

Quoting independent studies, Piramal said that there had been an average five per cent decline in real terms

over the last four years and drug prices in India are among the lowest in the world.

He pointed out that product patent regime will impact the industry leading to higher investment requirement

for R&D.

"Large investments in R&D are critical for affordable medicines in the future," he said.

Source:PTI News http://www.medindia.net/news/view_news_main.asp?x= 12497

Drug Price Regulation: An Imperative and an Obligation in India - Dr, Anurag Bhargava,

S. Srinivasan.

Will the final form of the pharmaceutical policy again neglect the predicament of patients , the

Indian experience of the free market in drugs and the priorities of public health?

The current proposed policy and the arguments of the industry:

No policy relating to the health of the Indian people arouses as much interest in the media as the

pharmaceutical policy. The current policy, evolved possibly in response to a directive of the Supreme

Court and a stated commitment under the common minimum programme, seeks to increase the number of

drugs under price regulation. The pharma sector is astir and has been trying to score points in the media.

Few counterpoints are being offered to clarify the real issues at stake, hence this piece.

The industry creates innovative arguments each time there is any talk of price regulation. It used to talk of

closure of units earlier, now there are visions of increase in number of spurious drugs, decline in exports

decline in R&D, and barely concealed threats of scarcity of drugs if price regulation is put in place. These

arguments are specious. It has been a part of the pharma policy that any drug developed by indigenous

R&D, shall be exempt from price control for a period of upto 15 years. There have been no claimants to

the best of our knowledge, for this exemption so far.

The arguments for price regulation:

The purchase of drugs is a unique situation.

The pharma industry portrays medicines as being like other consumer goods and patients being like other

consumers. In the case of medicines, the choice is exercise by a doctor, and not by the consumer, who is

usually ignorant of their nature. The need for medicines is often immediate, obligatory, even life-long, and

has life and death implications. For such a critical and essential commodity, governments all over the

world, even in so-called market economies regulate the prices of all medicines while providing them,

paradoxically, as part of a highly socialised system of healthcare.

The high personal cost of disease and the consequences of deregulation of drug prices in the past.

On the contrary in India we have one of the most privatised system of healthcare. 83% of healthcare related

expenditure is borne by out-of-pocket expenditure made by people, most often by the poor who fall sick

more often. More than two thirds of this expense in outpatient illnesses is made on purchase of drugs. Only

13% of the chemical entities made in India are presently under price regulation. The no. of drugs under

price regulation fell progressively from 347 in 1977 to 146 in 1986, 74 in 1995 to a projected 25 or so

drugs in 2002. The 2002 policy which would have virtually done away with price regulation, was stalled

on the interventions of the Karnataka High Court, who ruled that this would make essential and life-saving

drugs out of the reach of ordinary people. This case is subjudice in the Supreme Court. In fact each episode

ot deregulation has been followed predictably with a dramatic increase in drug prices. In 1995 for example

the price of a preparation for anemia rose by 177% while the price of anti-TB drugs rose by nearly 90%.

According to the WHO’s World Medicines Situation report of 2004, an estimated 649 million people in

ndia more than any other country in the world, lack regular access to essential medicines. The

availability of drugs in the public health system is abysmal by the Government’s own admission. The

increase in healthcare costs, of which drug price deregulation is a major cause has resulted in an increasing

number of people not seeking healthcare at all. Those who do seek healthcare fall into the trap of medical

poverty. Healthcare costs are becoming a significant cause of rural indebtedness and liquidation of assets

across the country.

The anarchy of prices of drugs which are outside the price-controlled list.

A strong argument for governmental regulation is provided by the reality of prices of drugs, which are

outside the price-controlled list. 2 reputed companies manufacture the same chemical in the same strength

with a retail price difference of even more than 1000%.Aventis charges Rs.95 for a single tablet of an

antibiotic like Levofloxacin 500 mg, while Cipla charges only Rs. 6.8 for the same tablet. The same drug

or diabetes can be sold for Rs. 2 as well as Rs. 10. The companies are freely charging upto 5-6 times in

the case of a drug for hypertension, upto 15 times in the case of a drug for a psychiatric ailment, upto 18

times the price of a drug for cancer, without any logic, and what is disturbing, without any intervention

from the government. The true nature of the market and the insensitivity of doctors to the price of a drug

is revealed by the fact the costlier brands often sell the most.

The real cost of manufacture of drugs: Price regulation is fully compatible with profitability.

The real cost of manufacturing drugs is often a very small fraction of the retail price. This is revealed by the

prices of drugs in competitive tenders, by the trade margins that companies offer, and by the humungous

amounts they can afford to spend on drug promotion.

Internationally an Indian company created a stir when in 2001 it offered to sell quality certified anti-HIV

drugs at 3% of the price at which American companies sell them. At home in India, even in quality

conscious bulk procurement processes like in Delhi and Tamil Nadu, the tender rates of drugs are as low as

2-20% of the market rate, which would be unheard of in any other commodity. Cadila Pharmaceuticals bid

tor supply of a medicine for worms, Albendazole 400 mg tablets was a mere 22 paise, while its ZYBEND

brand sells for Rs. I 1.90 in the market. A drug for hypertension like Atenolol is procured at 12 paise by

Delhi State while in the market the same drug is sold for as much as Rs. 2.50.

Trade margins in pharmaceuticals can be astronomical. Dr. Reddy’s Nimesulide is priced at Rs. 2.90 per

tablet, while Cipla offers the same to its traders at 10 paise per tablet. An antibiotic injection like Amikacin

made by Alembic has a retail price of Rs. 64, while the retailer can buy it at Rs. 12.50 . Numerous other

freebies are given to the trade which include free drugs, consumer items, overseas trips and the like. The

pharmaceutical sector needs to explain to the public how it can afford to sell drugs at even 10% of their

MRP to wholesalers and not suffer from loss of profitability and yet complain bitterly whenever the MRP is

sought to be lowered by the government? The new policy talks of a 150-200% margin on the post

manufacturing expenses for drugs under price control. Surely such a profit margin is adequate for

profitability of any manufacturing enterprise.

The need for a comprehensive, balanced and rational drug policy:

It is possible to balance the public good with private profit in a pharmaceutical policy. Profitability of drug

companies can be ensured while protecting the people of India from overpricing. The government is

planning to put all the 354 medicines in the National List of Essential Medicines under price control. Past

experience suggests that in the light of price regulation, the companies switch to production and promotion

of drugs, often irrational or higher priced alternatives which are outside the list. The government should

pre-empt this by bringing all alternative drugs also at the very least under a scheme of price monitoring.

The policy should put in place firm guidelines on conduct of clinical trials in India, limit new drug

approvals to entities which clearly confer a therapeutic and cost advantage, remove irrational formulations

which comprise a major part of the market, ban hazardous drugs, ensure quality in manufacturing and

testing of drugs, evolve stricter codes on pharmaceutical promotion, mandate provision of unbiased

prescribing information, implement nationwide pooled procurement schemes on the lines of Tamil Nadu

and Delhi, and improve availability of drugs in the public health system.

It needs to be clarified that price regulation is a national policy matter and in no way incompatible with

TRIPS. In fact it is even a greater imperative under TRIPS.

The MNCs are once again eyeing the huge market, which India has to offer, and pressing for all kinds of

deregulation. The pharmaceutical sector in India, which owes its existence and its success to strong

Governmental support, is clamouring for the same. The Government and its committees are all aware of the

fact of the anarchy of retail prices, the rise in prices after deregulation, the high trade margins, and the

impact of healthcare costs on people. If it still does not act in the public interest it shall be deemed

complicit in the rising graph of people’s miseries.

It remains to be seen whether concerns for the health of the people, and their distress, or the health of the

stock markets will engage the government in its thoughts and be reflected in its actions.

(Dr Anurag Bhargava is a practising physician in a rural community health program, and S.Srinivasan is

involved in manufacture of drugs at low-cost for community health programs. Both are members of the All

25 years)1^

NetW°rk Which h3S be6n camPaigninS on drug ^ues and a rational drug policy for over

Drug Price Regulation: An Imperative and an Obligation in India - Dr. Anurag Bhargava,

S. Srinivasan.