Rajeev_B_R - Final report.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

Rajeev B R | CHLP Fellowship | February 2015-April 2016

Community Health Learning

Programme Report

SOCIETY FOR COMMUNITY HEALTH AWARENESS AND RESEARCH

ACTION

Contents

Prologue- How I landed at SOCHARA ...................................................................................................................... 5

Learning Objectives.................................................................................................................................................... 8

Community Orientation and Preparation ............................................................................................................... 9

Building Blocks for Fellowship......................................................................................................................... 9

Understanding Community, Society, Development and Health ............................................................ 16

Understanding Community Health and Public Health.............................................................................24

Health system in India ...................................................................................................................................... 27

Social Determinants, Equity and Public Health ......................................................................................... 32

Health Systems and Policy ............................................................................................................................... 34

Environment, Sanitation and Health ............................................................................................................. 37

Local Health Traditions .................................................................................................................................... 41

Field experiences ...................................................................................................................................................... 44

My field area ........................................................................................................................................................ 44

Organisation ........................................................................................................................................................45

Community Health programme ...................................................................................................................... 52

Health Status........................................................................................................................................................56

Religion and Cultural aspects ..........................................................................................................................62

Physical Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................................... 63

Agriculture and food production ....................................................................................................................65

Education ............................................................................................................................................................. 66

Environment ........................................................................................................................................................67

Field Research ............................................................................................................................................................70

Abstract .................................................................................................................................................................70

Background .......................................................................................................................................................... 71

Methods ................................................................................................................................................................ 73

Results: ..................................................................................................................................................................74

Understanding Oral Health ..........................................................................................................................74

Conditions or Symptom Complexes ............................................................................................................ 77

Local Health Traditions.................................................................................................................................78

Social Issues and Challenges ........................................................................................................................ 81

Discussion ............................................................................................................................................................ 81

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................... 84

Reflections ............................................................................................................................................................85

Social, Economic, Political, Cultural and Environmental Analysis ......................................................................87

Development Parameters (Axioms) of ACCORD .................................................................................................. 88

Pedalling forward the Community Health Journey .............................................................................................. 89

1

Oral Health in Action ............................................................................................................................................... 94

Oral Health Policy: rational basis .................................................................................................................. 94

Gudalur experience ........................................................................................................................................... 94

London Charter .................................................................................................................................................. 94

Forum for Oral Health Action in India ..........................................................................................................95

Reflections of the Community Health learning Programme ............................................................................... 96

References .............................................................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined.

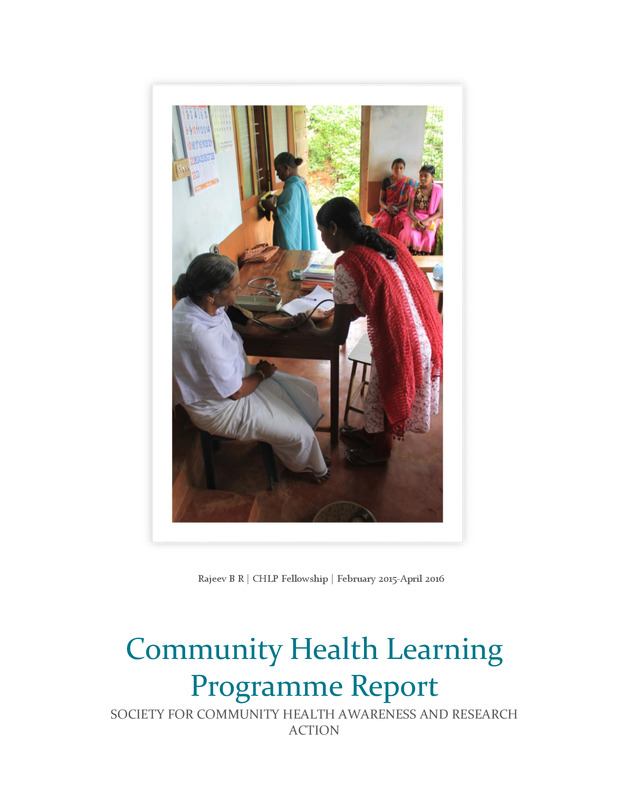

Cover Page photo: Adivasi health worker checking blood pressure of an elderly Mullukurumba

woman at ACCROD’s area centre in Ayyankolli village in the Nilgiris district.

2

I cannot express enough thanks and I am in debt forever to everyone in this journey. This journey

would have not been possible without Samantha and Dr Eugenio at first place. Ravi and Thelma

have been parent figures to me guiding, patting, cheering me every time I found myself in difficult

situations.

SOCHARA is wonderful place with beautiful people with beautiful hearts. Friendly smiling faces

always welcome people here. Mohammed’s immense knowledge on demographics and public

health, Chander’s anti-tobacco and Kumar’s social work experience with various organisations

have been a source of inspiration and joyful learning.

Adithya’s climate change sessions were eye openers, Rahul’s google head was always welcoming

us to discuss, Prasanna’s proverbs and polyglot skills were much appreciated, Janelle’s friendly

and caring attitude, Krishna’s communication techniques, Chandran’s virtual skills and Prahlad’s

santitation sensitivity techniques were not just inspiring but moving. The smooth functioning of

SOCHARA wouldn’t have been possible without Hari Bhaiya, Tulsi Bhaiya, Joseph, Vijayamma,

Kamalamma, Maria, Mathew, Vinay and Victor. They manage logistics efficiently. Special thanks

to the librarian, Swamy who has well maintained this treasure trove. All these made the learning,

a fun filled experience and I want to thank everyone.

At Gudalur, ACCORD and ASHWINI were very supportive. I would like to thank the Adivasi

community for their love and support. My heartfelt thanks to Stan, Mari, Shyla, NK, Rahul,

Ankur, Srikanth, Anna, Bhuvana and Vinoth who made Gudalur experience, a wonderful time.

Special thanks to Mahantu who mentored and guided me. It would not be fun without Royson,

Viraj, Mahesh, Jyothi and all the school children and teachers. I wish to thank Durga, who helped

me writing the consent and information sheet in Tamil and also helped me in transcribing

interviews. Gudalur stay will remain as a special memory.

This journey wouldn’t have been a pleasant one without my co fellows. Finally, I want to thank

my ever supportive family and friends.

3

ACCORD- Action for Community Organisation, Rehabilitation and Development

AMS- Adivasi Munnetra Sangam

ANM- Auxiliary Nurse and Midwife

AMF- Adivasi Mutual Fund

ASHA- Accredited Social Health Activist

ASHWINI- Association for Health Welfare In the Nilagiris

ATLM- Adivasi Tea Leaf Marketing

AYUSH- Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy

CHESS- Community Health Environment Survey Skill-share

CHLP- Community health learning programme

EAG- Empowered action group states

FRA-Forest Rights Act

HIV/AIDS- Human Immune Deficiency Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

IMR- Infant mortality rate

JAAK- Jana Arogya Andholana Karnataka

JSA- Jan Swasthya Abhiyan

LGBT- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender

LHT- Local Health Traditions

LMIC- Low and Middle Income Countries

NRHM- National Rural Health Mission

NHRC- National Human Rights Council

MSS- Mahan Sangharsh Samiti

PHC- Primary Health Centre/care

SOCHARA- Society for Community Health Awareness Research Action

SDH- Social Determinants of Health

TFR- Total Fertility Rate

UHC- Universal Health Coverage

VHSNC- Village Health, Sanitation and Nutrition Committees

VBVT- Vishwa Bharathi Vidyodaya Trust

WHO- World Health Organisation

4

During my training in Dental Public Health, there was lack of contextual understanding of the

entire public health. The course was for three years and I had hardly visited any PHC’s. The only

exposure was when there was dental outreach camp organised in a PHC. I had never met a health

worker or even an ANM. My understanding of villages and their problems were from books,

newspapers and scientific journals. I knew, I lacked the humanness in the training. I studied

5

about the national health programs of India, but didn’t have a solid understanding on their

implications at grass roots. There was a void in my training and When I heard about the

programme modules from both Samantha and Dr Ravi Narayan, it was something I was looking

for.

Besides, my staff at college were not friendly. Their understanding of social determinants was very

poor and didn’t encourage me either. Some of them were rude and hostile too. I would long for a

mentor or guide who is friendly and non-hierarchical. During my training, I undertook an online

offering course of “Health for All” by Johns Hopkins University. The course oriented me to

community health. It was the first exposure to primary health care. The case studies which were

used to explain in the course were success stories on how to bring about change in health status

of a community. Jamkhed1 and Gadchiroli2 projects were used as case studies (Arolle & Arolle,

1974). I understood about a health worker and how they can be agents of change. Since then, I

knew, I wanted that kind of exposure to real life situations and understand for the perspectives of

the people living in affected areas. When I met Dr Ravi Narayan, he was talking about what all I

wanted. I was presented with a training module which exactly what I was looking for.

My interest in humanities goes back to my childhood days. There are few incidents and

experiences during my growing years which had profound influence on my leaning towards

humanities. I was very much interested in Archaeology and History during my school days. I

always took part in social project competitions where I would prepare models and charts on

Egyptian, Roman civilisations and many others. I also won several prizes which further boosted

my interest. It was in one of those times, I came across books on humanities in my school and

public library. I read a lot about how cultures and beliefs in different societies and their influences

on economics, political scene, etc. I had decided that I would study sociology then, but my family

opposed this. They believed that, arts and humanity disciplines would not earn enough bread. My

interest in humanities remained hard, but I chose dentistry as a career out of compulsion.

It was in my third year under graduation, when I was introduced to Preventive and Social

Medicine, my childhood interests were revoked. I showed more interest in the social component

of medicine. It gave a new dimension to my understanding of how health and development go

hand in hand. For ex, the Great sanitary reforms of England which took place in the 18th century

had influenced the public health movement across the western hemisphere and decreased the

prevalence of communicable diseases (Park, 2014). Contrarily, communicable diseases still exist in

India because the structural and socio-cultural determinants are not addressed adequately.

Indigenous cultures exist across the globe and they form a unique ecology. Their behaviours are

in harmony with the environment they live in. The concept of self-sustaining and use of locally

available materials make them more adaptable and amenable to the laws of survival. In such a

context, they place health in the hands of their age old traditions which are yet to be explored.

This is where my interest in public health grew much stronger.

My interest in culture goes back to my roots. My forefathers are from a small village called

Molkalmuru in Chitradurga. It is well known for handloom industry. My forefathers weaved silk

1 Jamkhed is a small town in Ahmednagar district of Maharashtra. Jamkhed project is a Comprehensive Rural Health

Programme started by Drs Mable and Raj Arolle in 1970.

2 Gadchiroli is a district in central India. SEARCH (Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health)

started by Drs Abhay and Rani Bang in 1985 at Gadchiroli.

6

sarees. Here, Swakulasali, Pattasali and Padmashalis and many other weaving communities have

engaged themselves in the handloom profession for generations. All weaving communities

belonged to the shudhra group of social stratification3. Shudra means one who is skilled in an art.

The artisan strata include wide variety of occupations based on skilled handwork. Thus the

artisans were the suppliers of basic essentials and products for the smooth functioning of society.

From clothes to jewellery, iron to pottery; Shudras were the economical drivers and key

contributors of industry and machinery during the pre-independent India. This class included

tantuvai (weavers), swarnakara (goldsmith), vaidyas (healers) etc.

Molkalmuru silk sarees have a distinct style. Contrast colours of body and border, silver reinforced

gold zari, bird figures such as peacock, swan, parrot, floral pattern, and mango and temple images

are very unique to Molkalmuru style. There is rich history and culture represented in the sarees.

Today, the saree industry is dying. With this, the salubrious culture will also be lost and all will be

a thing of past. The motifs in the sarees not just had an attractive feature and also told a story. For

ex, peacocks and mangos are very common here. It is with no doubt, the flora and fauna also were

a part of daily life and thus adorned the sarees too. The craftsmanship means skills which are

learnt hard way. It represents civilisation and a learned activity which is socially accepted. Sadly,

with sarees gone and not much peacocks left, these all will be forgotten soon. It was not just

about which figure showed up on the saree. It is about how the weaving community understood

the nature around and expressing it in the form of art.

I also want to narrate another incident. This was when I was doing my Master's. My senior

researched on “Comparative Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Beliefs on oral health in Siddi

tribals, Tibetan refugees and Local population”. I had doubts about the reliability and validity of

the results of the thesis. His methodology was fairly simple. He visited them only once and

interviewed using a pre designed questionnaire. What puzzled me the most, was, how would one

reveal any personal information to a total stranger? I believe, one has to understand the social

dynamics of a community in all angles to win the confidence and then proceed to ask sensitive

questions.

Through Samantha’s experience at Kalahandi in Orissa, I got a clear picture of how the fellowship

works. Field work would give me an opportunity to live with the community and observe them

closely. Besides, joining CHLP was a calculated risk. The uncertainty of job and the stipend

offered for CHLP was just enough for sustaining and meeting monthly expenses. I took a while to

decide about it. I considered other options of either work or studying further. After much thought, I

decided to apply for this fellowship. I appeared for the interview and later was selected and that's

how I ended up at SOCHARA.

3 Shudra is the fourth varna, whose mythological origins are described in the Purusha Sukta of the Rig veda, one of the

sacred texts of Hinduism, and later explained in the Manusmṛti.

7

General

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Learn community action from a community point of view

Understand community health in action

Learn the health system in India- principles, delivery, etc.

Understand the social determinants of health in India

Understand the cultural factors influencing health in India determined by knowledge,

attitudes and behaviour.

6. Learn the quantitative and qualitative tools of measuring the health burden.

7. Understand the intricate networks through which community health functions

Research

1.

Learn conducting a community mapping, ethnographic methods, focussed groups

discussions, key informant interview method.

2. Understand health through anthropological view- human development, interactions and

existence in harmony with environment.

3. Observe and learn the indigenous way of life.

Personal

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Working in a team

Understand different cultures of fellow participants

Inculcate more good habits, learn from my mistakes, and become more integral.

Networking with various people from all areas

Learn new languages

8

BUILDING BLOCKS FOR FELLOWSHIP

The batch of 2015-16 consisted a diverse set of people from different backgrounds. There were full

time and flexi (part time) fellows. Most of them were from social sciences background such as

social work, anthropology, law and psychology. Few of them from bio- medical background such

as medicine, dentistry and pharmacy. There were with journalism, textiles and management

background too. People from different parts of India representing north east, north, central, south

and western India were there too with one exception from United Kingdom. This mix of

education, language, culture, etc was unique but posed many challenges in terms of

understanding the subject, language barrier, culture shock to name a few. It was important to

understand others and self at the same time to have a harmonious and cordial relationship with

all the fellows and the facilitators of the programme. The need to learn intra and inter personal

skills became imperative to understand oneself better.

Johari window was first conceptualised by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham in 1955 to help

people better understand their relationship with themselves as well as others (Luft & Ingham,

1955). It is a framework to categorise our levels of knowing a person. The arena block represents

traits of a person which are known by that person and others. The Facade block representing

information about a person which their peers are unaware of.

Figure 1: Johari Window

The blind spot represents information that the person is not aware of, but others are and

Unknown representing the person’s character that are not recognized by anyone including the

person. Johari region is what is known about a person by others in the group, but is unknown by

the person him/herself. It is the quadrant 2 - 'blind self' or 'blind area' or 'blind spot'. here are two

key ideas behind the tool: to build trust with others by disclosing information about oneself and

with the help of feedback from others, one can learn about oneself and come to terms with

personal issues. By explaining the idea of the Johari Window, one can help team members to

understand the value of self-disclosure, and you can encourage them to give, and accept,

9

constructive feedback. This can help people build better, more trusting relationships with one

another, solve issues, and work more effectively as a team. The ultimate goal of the Johari

Window is to enlarge the Open Area, without disclosing information that is too personal. The

Open Area is the most important quadrant, as, generally, the more people know about each other,

the more productive, cooperative, and effective will be when working together.

At the end of the Johari class, we were given a sheet of paper to write one good quality about each

other. This exercise was to make the fellows think positively and reflect upon some good qualities

observed in the fellows only within a few days of interaction. It was a test to examine the

observation skills and also about knowing a person much more.

Communication skills were introduced during the first collective session. The two-day

workshop on communications skills was an eye opener and team building and team work

exercise. It opened up every fellow from their inhibitions, timidity, language barrier and

inferiority complex to certain extent. Nearly 90% of the exercise was non-verbal and action

oriented. There were improvisation exercises such as voice modulation, imitation, mime shows

and role plays.

Figure 2: Communication skill workshop in progress

10

The sessions were modelled to train fellows to cope up with challenges that one might face in

field. There were sessions related to role plays to communicate the message effectively with

minimal props. Fellows were divided into two groups to come up with a health issue and conduct

a role play highlighting a health issue and also capturing the nitty grits of daily life. Our group

decided to showcase childhood morbidity and the effective role played by ASHA worker. We used

common diarrhoea as a highlight to draw attention. It was a tedious job to have a consensus on

what we do as a group and, to manage it effectively without falling apart with the group, was the

lesson learnt. Some of the group members were difficult to convince and tried to subjugate other

weak voices. Soft skills expose the dynamics of a group and, more over this exercise was apt at

that time. We were preparing for the field and this exercise helped us in understanding the

management of the community members with whom we have to work.

Figure 3: Fellows in imitation session during the communication workshop

Social skills like interpersonal skills are very vital for anyone who interact and work with people

on a day to day basis. People skills is the ability to communicate effectively with people in a

friendly way. It involves, understanding ourselves and moderating our responses, talking

effectively and empathizing accurately and building relationships of trust, respect and productive

interactions. Soft skills enable those qualities and attributes needed to succeed in community

dialogue. They encompass an individual’s ability to listen well, to communicate effectively, to be

positive, to manage conflict, accept responsibility, show respect, build trust, work well with

11

others, manage time effectively, accept criticism, work under pressure, and demonstrate

discipline.

In one of Dr Ravi Narayan’s class, we were asked the names of our support staff- Mr Tulsi Heera

Adhikari and Mr Hari Ojha or Tulsi bhaiya and Hari Bhaiya as we call them with affection. Dr Ravi

tested us, whether we were good at soft skills. Also, we were subjected to another test. Hari

bhaiya or Tulsi Bhaiya would get us tea twice daily, once at 10 30 am and at 3 pm. We were

observed, whether we helped to serve each other or not. This was also, to check if we had

hierarchical attitude. It was also to know how caste and class biased we were.

During field visits, this was an important people skill to bear in mind. People in the community

would only entertain us when equality is established after the acquaintance stages of relationship

are over. Being unbiased and displaying behaviour of trust, respect, equality is as vital to develop

cordial relationship in order to bring behavioural changes in the community. The tea test, as what

I love to call it, is crucial to establish the initial communication. During my field visits, I was

offered black tea with copious amount of sugar which I detested whole heartedly, was offered at

every house visited and any meeting that I attended. With very less chance to deny the adivasis’

love and hospitality, I would drink it. Dr Ravi would tell us that, it was their way of judging a

person if he or she is discriminator.

Our gender sensitivity was also checked by how many men cared to lift up the flappers in the

toilet.

Our

cleanliness

quotient was also checked if

we cared about flushing

toilets after use, dustbins

used well, cared to keep the

surroundings clean. All

these exercises were to

prepare for any challenges

in field or in future. All of us

got together and cleaned up

the premises of SOCHARA

twice.

We

called

it

Shramadhan4. Shramadan

was popularised during the

freedom movement by M K

Gandhi. It is an altruistic act

of gift of labour or in simple

terms

doing

voluntary

contribution of work for

public

cause.

It

was

Gandhiji’s call to the nation

to do shramdhana at every level to uplift the self and others. Gandhiji wrote in Indian Opinion,

that intellectuals should contribute to upliftment of their fellow labourers by earning a living

through physical labour: “Last but not least, it seems to us that, after all, nature has intended man

Figure 4: Fellows doing Shramadan

4

Shramadana means the giving of your time, energy and skills for the benefit of others without any personal gain or

benefit.

12

to earn his bread by manual labour-'by the sweat of his brow”. (Gandhi, 1910 ). Shramadan today

has become an annual event on October 2nd celebrated as Gandhi Jayanthi, the birthday

celebration of M K Gandhi. People exhibit sycophantic gestures to pose for cameras and media

attention. It is sad to witness the actual shramadan is lost.

We all gloved our hands, picked up brooms to clean up the pile of garbage dumped by passers-by

in front of SOCHARA. The place was a nuisance to eyes and nose. It was a painstaking labour

subjected to heavy duty, stench of the garbage, directly exposed to micro-organisms and insects,

potential danger of infections, etc. The act made us realise how difficult it would be for hundreds

of Pourakarmikas5 who clean up the city every day. The health concerns are many. The detritus

also had sharp objects such as broken glass pieces, needles, blades and severed ends of metals. Dr

Thelma Narayan had provoked us about having civic responsibility of knowing people around us.

She asked if anyone us ever bothered to find out about their lives, or even their names. This

shramadana did stir up interest about the municipal sweepers. Shwetha Gupta, co fellow who

resided in the next building of SOCHARA found out the name of the pourakarmika of her lane.

Her name was Ramulamma who came from neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh and has been

working for several years. Ramulamma complained that, they don’t get paid on time. The

contract labour laws are often criticised as anti pourakarmikas. (DNA, 2012) They prevent diseases

in cities. Yet they have minimal job security measures. They contract communicable diseases

quite often and do not have free access to medical care. They are underpaid and work involves

manual segregation of waste without self- protection. The occupational safety and health

measures are completely violated. The pourakarmikas put across their demand and held a strike

too. (Ramani, 2015)

Figure 5: Newspaper column showing the demands made by Pourakarmikas

In another session, we were all given three green colour cards and were asked to write about our

personal, professional and expectations of CHLP. I scribbled few thoughts into the paper.

Although, in hindsight, when introspected, some goals and expectations have been met. While

some of them have been re looked. Particularly, professional goals. I wanted to join the CHLP as a

flexi and leave if I got admission for doctoral studies. But, I decided to finish the course, because

the course provided a solid community exposure which I didn’t want to jeopardise.

5 Pourakarmika is a Kannada term referred to labourers who clean the roads and drainage in Bangalore city.

13

Values such as Equity, rights, social justice, inclusiveness, respect for local health cultures,

solidarity and secularism were facilitated at different stages of collective. 2015 was of particular

relevant to the values discussed. The political scene in India and also across the world was

turbulent and many events were testimonies for violating these values. These values are

intertwined and are moral characters which are practised at an individual, family, community,

national and global level in an egalitarian world. All religions advocate theses values. They are

integrated in a person as one grows. Values are decided by the society and evolve over time. These

values conflict with greed, ego and selfishness. These values have been used as a weapon to

influence critical mass in social movements. Dr R Srivatsan, a political theorist who was the

convenor of medico friends circle6, mentioned about Gandhiji’s Ramarajya7 concept as a utopian

political independence thought. (Gandhi, 1937) Gandhiji adopted seva8 for Harijans9, Mitratva10

for Muslims and Satyagraha11 against the British.

Values relate to the norms of a culture, but they are more global and abstract than norms. Norms

provide rules for behaviour in specific situations, while values identify what should be judged

as good or evil. While norms are standards, patterns, rules and guides of expected behaviour,

values are abstract concepts of what is important and worthwhile. A silent prayer offered for the

victims of Chennai cyclones during the National Dissemination meeting was a norm but reflects

solidarity. Values are generally received through cultural means, especially transmission from

parents to children. Parents in different cultures have different values. For example, parents in

a hunter–gatherer society or surviving through subsistence agriculture value practical survival

skills from a young age. The adivasis12 of Gudalur where I did my field observations showed

immense community bonding and sharing. Mari Marcel Thekaekara, co-founder of ACCORD and

a regular columnist at New Internationalist shares her views about sharing and caring among the

adivasis of Gudalur. She mentions how a young Adivasi girl shared a biscuit with her siblings

given to her (Thekaekara, 2015). Values such as these are a part of their lives and they don’t seem

to be puzzled by these gestures.

All these values are to be taught and learnt by self or through others at home, school, college,

university, work place, etc. Community health learning begins with recognizing these values as an

important part of our lives. Important to us is rights. Right to health is a fundamental right to

attain highest possible standard of health. Community health emphasizes rights and entitlements

as one of the axioms.

Secularism was by far the most argued topic in the past one year in print and social media. New

terms such as “Sicklularists” have sprung up. In my opinion, secularism means to treat everyone

and everything equal. Indian constitution upholds secularism. Accordingly, all religions,

languages, people and cultures are equal. Secularism in India, thus, does not mean separation of

religion from state. Instead, secularism in India means a state that is neutral to all religious

6 medico friends circle is a think tank founded in 1974 by a group of people inspired by socialism and left movements.

The founders were followers of freedom fighter, Jayaprakash Narayan.

7 Ramarajya- Gandhian idea of political independence, i.e., sovereignty of the people based on pure moral authority

8 Seva is a selfless service offered to anyone in need.

9 Harijans is a word coined by Gandhiji referred to Dalits who were considered untouchables.

10 Mitratva is Sanskrit term for friendship.

11 Sathyagraha means “insistence for truth”. It was a non-violent resistance which Gandhi used in his campaigns in

South Africa and India.

12 Adivasis or original inhabitants. I prefer to use the term instead of tribal. Adivasis also means indigenous.

14

groups. Romila Thapar, noted historian shares her views on secularism. “A secular society and

polity does not mean abandoning religion. It means the religious identity of an Indian has to give

way to the primary identity of a citizen. And the state has to guarantee the rights that come with

this identity, as the rights of citizenship”. (Thapar, 2015)

Denial of Right to Health is the most argued case in almost all LMIC. A national level public

hearing on denial of right to health in public and private sector was organised by NHRC in

association with SOCHARA, JSA, JAAK and other civil society organisations13. The meetings were

held at four different places in India. The southern regional meeting was convened in Chennai

and was to be held on December 14 and 15th, 2015. The deluge at Chennai forced NHRC to cancel

the meeting.

According to WHO, “The right to the highest attainable standard of

health” requires a set of social criteria that is conducive to the health

of all people, including the availability of health services, safe

working conditions, adequate housing and nutritious foods.

Achieving the right to health is closely related to that of other

human rights, including the right to food, housing, work, education,

non-discrimination, access to information, and participation.

The right to health includes both freedoms and entitlements.

Freedoms include the right to control one’s health and body

(sexual and reproductive rights) and to be free from interference

(free from torture and from non-consensual medical treatment

and experimentation). Entitlements include the right to a system

of health protection that gives everyone an equal opportunity to

enjoy the highest attainable level of health.

Vulnerable and marginalized groups in societies are often less likely

to enjoy the right to health. Three of the world’s most fatal

communicable diseases - malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis disproportionately affect the world’s poorest populations, placing a

tremendous burden on the economies of developing countries.

Conversely the burden of non-communicable disease – most often perceived as affecting highincome countries is now increasing disproportionately among lower income countries and

populations. Violations or lack of attention to human rights can have serious health

consequences. Overt or implicit discrimination in the delivery of health services violates

fundamental human rights. Many people with mental disorders are kept in mental institutions

against their will, despite having the capacity to make decisions regarding their future. On the

other hand, when there are shortages of hospital beds, it is often members of this population that

are discharged prematurely, which can lead to high readmission rates and sometimes even death,

and also constitutes a violation of their right to receive treatment.

Figure 6: Newspaper

advertisement on NHRC

meeting

The goal of a human rights-based approach is that all health policies, strategies and programmes

are designed with the objective of progressively improving the enjoyment of all people to the right

13 The word ‘Civil Society Organisation’ is deliberately used for substituting Non-Governmental Organisations.

15

to health. Interventions to reach this objective adhere to rigorous principles and standards,

including: Non Discrimination, Availability, Accessibility, Quality, Acceptability, Accountability

and Universality. (WHO Committee on Economic, 2009)

UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY, SOCIETY, DEVELOPMENT AND HEALTH

Understanding a community is an arduous task. It involves careful observation of everything

without making a value based judgment and reporting honest picture devoid of preconceptions. It

is a hard assignment to be non- prejudiced. Our upbringing is always modelled on the basis of

questioning and critiquing. The very essence of science is based on the strong foundations of

questioning the way it is, and understanding things the way they function means getting down to

a level where one sheds his or her hierarchical attitude and looks through the eye of the

observant.

The concept of community is a sociological construct. It is a set of interactions, human

behaviours that have meaning and expectations between its members. Not just action, but actions

based on shared expectations, values, beliefs and meanings between individuals. Observation is

the key here. It involves careful watch of the functioning of a system. Observation is the

foundation of descriptive studying. The cognitive senses have to be working at their best to be

accurate. Reporting as it is, is not as easy as it seems so. The observant should have an eye for it

and write whatever appeared to the eyes, which means that, it is a skilful job

and highly competent work. A thorough knowledge of what has to be done. Even while

everything works well, acknowledging the grey areas in between apparent black and white is the

real challenge. My understanding of the community is still in a nascent level and I think, I have

made an attempt at understanding little bit of the black and white areas, although some of the

grey areas were understood in due course with help.

Community is defined as “a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social

ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in geographical locations or settings”.

(Kathleen M. MacQueen, 2001 ) According to a research, community has five core elements—

locus, sharing, joint action, social ties, and diversity which were was cited by 20% or more of

respondents. (Kathleen M. MacQueen, 2001 )

Community largely encompasses animate and inanimate objects. There is an objectification of

characters such as our people, my place, etc. and that determines the identity of a person or a

group of people. Society is a web of social relationships. It includes every relationship which

established among the people. This social relationship may be direct or India organised or

unorganized, conscious or unconscious. But community consists group of individuals. A definite

geographical area is not necessary for society. It is universal and pervasive; but, a definite

geographical area is essential for a community.

Community sentiment or a sense of "we feeling" is not essential in a society; community

sentiment is indispensable for a community. There can be no community in the absence of

community sentiment. Society is wider; there can be more than one community in a society.

Community is smaller than society. There cannot be more than one society in a community.

Society is abstract. It is a network of social relationships which cannot see or touched. On the

16

other hand, community is concrete. It is a group of people living in a particular area. We can see

this group and locate its existence.

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or

interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives differ from cooperatives in

that they are not necessarily focused upon an economic benefit or saving, but can be that as well.

Class and Caste have differences have existed in India and elsewhere since time immemorial. Dr.

Ketkar defines caste as "a social group having two characteristics: (i) membership is confined to

those who are born of members and includes all persons so born; (ii) the members are forbidden

by an inexorable social law to marry outside the group." Baba Saheb Ambedkar, the architect of

Indian Constitution, argues that caste existed long before Manu14. (Ambedkar, 1979) He was an

upholder of it and therefore philosophised about it, but certainly he did not and could not ordain

the present order of Hindu Society. His work ended with the codification of existing caste rules

and the preaching of Caste Dharma. At the outset that the Hindu society, in common with other

societies, was composed of classes and the earliest known are (1) the Brahmins or the priestly

class; (2) the Kshatriya, or the military class; (3) the Vaishya, or the merchant class; and (4) the

Shudra, or the artisan and menial class. He further argues that, particular attention has to be paid

to the fact that this was essentially a class system, in which individuals, when qualified, could

change their class, and therefore classes did change their personnel. His thesis revolves around

proving that some castes were formed by imitation, the best way, it seems to me, is to find out

whether or not the vital conditions for the formation of castes by imitation exist in the Hindu

Society.

This process of imitation is coined as “Sanskritisation”15 by eminent Sociologist and Anthropolgist,

M N Srinivas. (Srinivas M. , 1952) In today’s times, there is a myth that caste and class practices

are predominantly observed in rural areas, which is often the reason quoted for migration after

job opportunities. Dr Ravi Narayan mentions that, class and caste practices are more obvious in

urban educational centers. (Collective notes) The unfortunate death of Mr Rohit Vemula, a Dalit

doctoral scholar is a typical example of urban caste practices. The 26-year-old PhD student killed

himself inside the campus of Hyderabad Central University. Rohit was a member of the

Ambedkar Students' Association, which fights for the rights of Dalit (formerly known as

untouchable) students on the campus. He was one of five Dalit students who were protesting

against their expulsion from the university's housing facility. The five faced allegations that they

attacked a member of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad - the student wing of India's ruling

Bharatiya Janata Party. They all denied the charge and the university cleared them in an initial

inquiry, but reversed its decision in December, 2015. Rohit in his suicide note, he writes, (Vemula,

2016)

14

Manu is the name accorded to the progenitor of humanity, He is ascribed to the Sanskrit text, Manusmriti which is

considered by some Hindus to be the law laid down for humans.

15

Sanskritisation may be briefly defines as the process by which a ‘low caste’ or tribe or other group takes over the

customs, ritual, beliefs, ideology and style of life of high and in particular, the twice born (dwija) caste.

17

“The oppressive attitude of bureaucracy and brahminical mindsets of a few… The value of a man was

reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never

was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing made up of star dust. In very field, in studies, in

streets, in politics, and in dying and living"

Swami Vivekananda said: "Caste is an imperfect institution, no doubt. But if it had not been for

caste, you would have had no Sanskrit books to study. This caste made walls, around which all

sorts of invasions rolled and surged but found it impossible to break through." The newly created

Telangana state’s movement started off as a Dalit movement and politically motivated campaign.

Policy towards Dalits is often criticised as appeasement and vote bank politics rather than

genuine desire for uplift of the backward classes. Despite the commonly held belief that casteism

and untouchability are prevalent only in rural India with few traces of this practice in

cosmopolitan cities, a report reveals notions of impurity and inferiority that still dictate the

occupations and livelihoods of Dalits, particularly in the city of Hyderabad. (Mehta, 2015) Swami

Vivekananda’s words are true in this case. Caste has made an impregnable walls and these provide

platform for vote bank politics.

Today’s, class discrimination is not caste based, but it is the urban elite education based; opines

Dr Ravi Narayan. (Collective notes) Rohit’s suicide created a stir in nation. Politicking of his caste

status also picked up instantaneously. Caste based reservations continue in government and

educational institutions. There is a hidden discrimination of the scheduled castes and tribe

students in educational institutions. It is much more obvious in government offices. Government

jobs are called based on reservations. The Maharaja of Mysore, Shri Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV and

his Diwan, Sir Mokshagundam Vishweshwaraih argued on caste based reservations. Sir M V had

opposed caste based reservations. He stated in his memoirs, “My idea was that by spreading

education rapidly and adopting precision methods in production and industry, the State and its

entire population would progress faster. By ignoring merit and capacity, I feared production would

be hampered and the efficiency of the administration” (Vishweshwaraih, 1951)

The new class of educated middle class urban elite have bought about a new dimension to caste

and class issues. There is a feeling of threaten among a lot of educated mass. The identity crisis

which is a result of heavy competition has led to class distinction. The most affected are the

scheduled tribes, especially the adivasis. Their primitive traits, geographic isolation, shyness with

the community at large have made them vulnerable to exploitation.

Social exclusion in today’s times is no more related to caste oppression and women exploitation.

The structural determinants which enable a person or group of people to go below the line of

social mobility is a recognised fact. LGBT, minorities, debt ridden farmers, SC and ST, adivasis,

migrant labourers, urban slum dwellers, people with mental and physical disabilities, drug

addicts, delinquent etc. face discrimination and marginalisation at many levels.

According to the WHO’s Social Exclusion Knowledge Network, Exclusion consists of dynamic,

multi-dimensional processes driven by unequal power relationships interacting across four main

dimensions - economic, political, social and cultural - and at different levels including individual,

household, group, community, country and global levels. It results in a continuum of

inclusion/exclusion characterised by unequal access to resources, capabilities and rights which

leads to health inequalities. (Jennie Popay, 2008)

18

Social exclusion will have direct consequences on the health inequalities. Both of them have

underlying social and structural determinants governing the relationship. The WHO Commission

on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH, 2006) framework for action on health inequalities

highlighted the socioeconomic and political context and including: the labour market; the

educational system; religion and other cultural systems; and political institutions. These give rise

to patterns of social stratification based on differential access to economic status, power and

prestige. Income levels, education, occupation status, gender, race/ethnicity and other factors are

used as proxy indicators of these differential social positions. Based on socioeconomic position

individuals and groups experience differences in exposure and vulnerability to healthcompromising conditions. Socioeconomic position determines the level or frequency of exposures

and the level of vulnerability (intermediary factors through which social inequalities generate

health inequalities). The fundamental driving force for social inequalities and thus for health

inequalities within the CSDH framework is ‘power’ embedded in social relationships and

exercised through the formal and informal institutions and organizations making up the

socioeconomic and political contexts.

Figure 7: WHO framework of Health inequalities and social determinants

Power dynamics play a major role in health. Underneath questions of injustice and inequality is

the question of power. Power is the degree of control over material, human, intellectual and

financial resources, exercised by different sections of society. (Miller, 2006) Empowerment of

women, oppressed, weaker sections is the common talk by sociologists, activists and social

workers.

Empowerment is a strong social process involving power dynamics. When we say, women

empowerment, it means giving equal power to women in all situations. It is a social, economic

19

and politically ascribed status delivered to women. At a family level, woman empowerment means

the husband or the men in the family give equal status. It is the same at community level too.

Community empowerment is a dynamic process where the oppressed or the weak are able to

access entitlements and exercise rights.

It is a complex situation where the stronger section of the society is ready to accord the equality

and equity position to the weaker. It is often mistaken and implied that, empowerment is

enabling the powerless to become aware of their rights. But, it is forgotten and misled by civil

society organisations, media and politicians. For ex, the 33% reservation for women in the Indian

Parliament is perceived as instrument to gain equal status as men. In my opinion, empowering

only happens when the men are ready to share the platform along with women, rich are ready to

help poor, government is ready to structurally elevate poverty, etc. Nevertheless, women have

achieved incredible success as change agents. Majority of the health workers are women. Had

they not actively participated in the health care delivery, women and children related diseases

would still have been in an upsurge motion.

Dr Ravi Narayan narrated a story about community empowerment which he was part of, Mallur

Health Cooperative: In Mallur village in Karnataka, a health cooperative attached to a milk

cooperative was set up way back in 1973. Encouraged by the success of the milk cooperative, the

members persuaded doctors of the St. John Medical College to start a health care centre, which

would be self-sustained, financed and managed by the community. The health cooperative

provides services to nearby villages. During the first two years, members contributed at the rate of

one-two paise per litre of milk sold by them. Subsequently, five percent of the profits from milk

sale were given to the health centre. (ICMR, 1976)

Community empowerment is also a process where the community is aware of the issues around

them and take right informed decisions to deal the issues. It encompasses the principles of health

promotion. Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to

improve, their health. It moves beyond a focus on individual behaviour towards a wide range of

social and environmental interventions. (Promotion, 1986.) The Lalonde report16 from the

Government of Canada, which contained a health promotion strategy "aimed at informing,

influencing and assisting both individuals and organizations so that they will accept more

responsibility and be more active in matters affecting mental and physical health".

Another example for community empowerment is the adivasis of Gudalur. ACCORD started

working in 1984 with land rights movement. Within two years of their work, ACCORD with AMS

was able to reclaim about two thousand acres of land from local land lords. The Adivasi

community realized that they had poor access to health care despite presence of primary health

care centres. The PHC staff discriminated them and ill-treated most often. They realized that they

wanted a health care and, thus they demanded for health services to ACCORD. It was at that

time, Dr Devadasan and Dr Roopa started the community health programme. The community

health programme was able to reduce communicable diseases to a great extent. But, the acute

conditions, emergencies couldn’t be handled and mortality still continued. The adivasis realized

16

Marc Lalonde, who was the Canadian Minister of National Health and Welfare in 1974, proposed a new "health field"

concept, as distinct from medical care. The new concept "envisage[d] that the health field can be broken up into four

broad elements: Human biology, Environment, Lifestyle, and Health care organization;" that is, determinants

of health existed outside of the health care systems. It was one of the first documents which drew global attention

towards social determinants of health.

20

that they need a hospital to handle emergencies. Thus, a adivasi community owned hospital came

into existence. The Adivasi ownership changed the power dynamics in Gudalur. The hospital was

open to non-adivasi too, but they had to get permission from the local sangha17 to avail treatment.

Until then, the adivasis were dependent on non-indigenous people for many things. With quality

care provided at the hospital, non-indigenous people began to realise that they were dependent

on adivasis for health. The power was now vested in adivasis or it was hard earned and also

importantly shared by non-indigenous people.

Even 67 years after Independence, the problems of Adivasi communities are about access to

basic needs. These include, but are not restricted to, elementary education, community

healthcare, sustainable livelihood support, the public distribution system, food security, drinking

water and sanitation, debt, and infrastructure. For them, equality of opportunity remains largely

unfulfilled. In this context, it is important to stress that the values of adivasi18 culture are

transmitted in a manner that protects the right of the bearers of knowledge to determine the

terms of the transmission without exploitation or commodification. Nor can the Adivasis’

unhindered access to land and forests, especially in scheduled areas, be understated. Indigenous

communities have, over the decades, witnessed the fragmentation of their habitats and

homelands and the disruption of their cultures through predatory tourism. All this has left them

shattered and impoverished. Entire communities across states have been dispossessed

systematically through state action, and have been reduced from owners of resources and wellknit, largely self-sufficient communities to wage earners in agriculture and urban agglomerates

with uncertain futures. Yet, we can scarcely forget that the rights of adivasi communities in India

are protected by the Constitution and special legislations.

Indigenous communities across the world face extinction, social exclusion, exploitation,

marginalization, main streaming, acculturation, etc. Scores of these largely self-sustaining

traditional communities continue to this day in remote jungles, forests, mountains, deserts, and

in the icy regions of the north. A few remain completely isolated from modern society. Their

home is under threat. Most forests where the indigenous communities dwell are source of

minerals such as coal, timber and other resources. These attract industries and apathy by

governments cause conflicts. Some of them even give way to extremist activities and have resulted

in naxal and maoist movements. The identity crisis particularly of culture, environment, religious,

etc have led to the present conflicts.

The people of Mahan19are facing the threat of wipe out. Giant corporations like Essar and

Hindalco are after the coal reserves below these forests. Over 14,190 lives and livelihoods were

dependent on the Mahan forests, Madhya Pradesh. Their culture, community and lives are

intertwined with the forests that the corporations threaten to destroy. Displacement from their

natural habitat was devastating for the indigenous community.

17 AMS- Adivasi Munnetra Sangam (www.adivasi.net) is a conglomerate of village level groups called sanghas containing

members from the indigenous communities.

18 The term has vernacular and local synonyms such as Girijanalu (Hill inhabitants) in Andhrapradesh, Kaadu

Manushyaru (forest dwellers) in Karnataka, Malaivasi (Hill inhabitant) in Tamil Nadu, Adibasi (same as adivasi) in

Orissa, Chattisgarh and Jharkand.

19

Mahan in Madhya Pradesh is one of the oldest Sal forests of Asia

21

Hindalco and Essar want to mine for coal in Mahan. The coal mining companies pose a threat to

destroy the lives of the indigenous people of Mahan. The people of Mahan have come together to

reclaim what is theirs. The MSS was formed in March 2013 to protect the forests and land from

coal mining. Since then, the MSS has expanded to 11 villages. They have also organised rallies and

public meetings to raise awareness of their rights in the region. The Forests Rights Act20 (2006)

entitles communities to decide for themselves. It recognises forest dwellers’ rights and makes

conservation more accountable. In Mahan, the people are fighting for their right to ensure this

law is implemented and their rights are respected. With the help and support of Greenpeace

international and other environmental activists, MSS was able to get a stay from the court on the

mining activities. (Greenpeace, 2013)

Another success story of Adivasi struggle is Niyamgiri in Odisha21. State-owned Orissa Mining

Corporation, which was granted mining rights for 30 years in 2004. It was granted a right to mine

in the Niyamgiri forest area which is rich in bauxite deposit, to supply ore to Vedanta Resources.

In 2013, a dozen villages in southern Odisha invoked their right to worship the Niyamgiri hilltop,

warding off government plans to open a bauxite mine in their neighbourhood. The struggle ended

up in the court. The Supreme Court passed a historic and exceptional referendum order in

January,2014, to refuse final forest clearance to the proposed mine. Environmentalists world over

celebrated the victory of the Dongariah and Jarnia Kondhs primitive tribal groups from one of

least developed corners of the country. But the state government has gone back to the court to

revoke the case. (MOHANTY, 2015)

Legally and constitutionally, Clause 5 of Article 19, specifically is concerned with protection of

interests of scheduled tribes as distinct from other marginalised groups through limitations on

right to freedom of movement [sub-cause 1(d)] and right to freedom of residence [sub-clause

1(d)]. This, with existing protections offers a core and express fundamental right protection to

adivasis (as distinct from legal/ statutory protection) from a range of state and non-state

intrusions in scheduled areas as well as from the perennial threat of eviction of adivasis from their

homelands. (Kannabiran, 2015)

Stephany reports about Eco Village. Traditional indigenous communities offer the best example of

sustainability. Worth mentioning is Eco villages. Ecovillages aren’t about technology. They are

locally owned, socially conscious communities using participatory ways to enhance the spiritual,

social, ecological and economic aspects of life. Findhorn Ecovillage in the United Kingdom is one

of the best known and has half the ecological footprint of the UK national average. It includes 100

ecologically-benign buildings, supplies energy from four wind turbines, and features solar water

heating, a biological Living Machine waste water treatment system and a car-sharing club that

includes electric vehicles and more. (Leahy, 2015)

Traditional knowledge and a holistic culture is a key part of the longevity of many indigenous

peoples. The march of progress means that efforts are being made both to extract the resources

on which these communities rely and to ‘mainstream’ indigenous groups by introducing Western

medical, educational and economic systems into traditional ways of life. The traditional medicine

20 The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers Act better known as Forest Rights Act passed in 2006

upholds the rights of forest dwellers across India's forest areas for democracy, livelihood and dignity.

21 Odisha, previously called Orissa is a state in the eastern side.

22

practiced by the indigenous communities relies entirely on the forest for herbs and medicinal

plant sources. It is well documented that, some of the modern medicines are derived from the

traditional indigenous medicine knowledge.

It is important to preserve these biodiversity cultures and practices, especially local health

traditions. The Karnataka knowledge commission was set up in 2000 to focus on the key

components of the public health system in Karnataka state. The knowledge commission charted

an actionable plan to revitalise local health traditions by state patronage and encouraging LHT’s

based home remedies and recognising LHP to strengthen local health traditions in primary health

care through state and university accreditation mechanisms. (Karnataka Knowledge Commission,

2012)

Agrarian distress is another important social issue that is plaguing the country. There is an

increase in the number of farmer suicides across India. Inflation, loans and debts, failure of

rainfall, pesticide and insecticide issues, increase in the price of fertilisers and falling prices of

crops, political treaties, etc are among the many reasons for this social issue.

The agrarian distress can be traced back to Green revolution22 . The introduction of genetically

modified seeds which yielded high production of crops. This genetically modified seeds also

require heavy feed of fertilisers and pesticides. Heavy use of chemicals and continued high

production of crops at a massive scale have rendered the lands untenable. Climate change and

less rainfall have pushed farmers to edge.

With the liberalization of the economy in 1991, more banks started giving loans to farmers to buy

heavy machinery including tractors and to dig tube wells. More agriculture based industries like

Monsanto came in. The underlying agrarian crisis is a result of marginalization of agrarian

economy in national policy since the economic reforms of 1991. The increasing growth of

multinational companies’ influence in the changing global political economy is apparent. This

coincides with the quiescence of farmers’ movement as compared to 90’s which is reflected in the

changing rural society and their attitudes. (Posaani, 2009)

Many activists and civil society organisations have been fighting against the lobbying of

developed countries and supranational companies in imposing treaties and sanctions on

developing countries. The commonly debated topic is the price fixing on crops based on the

international trade as against the free trade. Vandhana Shiva, a noted activist has been in the fore

front of agitation against Monsanto and other agriculture based companies who are trying to

monopolise the agricultural market. Control over seed is the first link in the food chain because

seed is the source of life. When a corporation controls seed, it controls life, especially the life of

farmers.

22 Green Revolution in India was a period when agriculture in India increased its yields due to improved agronomic

technology. The introduction of high-yielding varieties of seeds (hybrid seeds) and the increased use of

chemical fertilizers and irrigation led to the increase in production needed to make the country self-sufficient in food

grains, thus improving agriculture in India. The methods adopted included the use of high-yielding varieties of seeds

with modern farming methods. Measures adopted were the use of high yielding varieties of seeds or hybrid seeds,

expansion of irrigation infrastructure, use of insecticides and pesticides, consolidation of holdings, land reforms,

improved rural infrastructure, supply of agricultural credit, use of chemical or synthetic fertilizers, use

of sprinklers or drip irrigation, use of advanced machinery and the use of vector quantity.

23

The Agreement on Agriculture, negotiated during the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement

on Tariffs and Trade, which determines the price of crops is criticised for

reducing tariff protections for small farmers, a key source of income in developing countries,

while simultaneously allowing rich countries to continue subsidizing agriculture at home.

In July 2015, as many as 90 farmers committed suicide in Mandya and Mysore districts of

Karnataka. The relatives of deceased reported that lack of institutional credit as major problem.

(The Hindu, 2015) This issue was also riased in the legislative sessions. Activists and the media

rightly question loopholes in the National Crime Records Bureau data, pointing out that several

state governments often report no farm suicides, contrary to local media reports. Suicides of

farmers represent only the tip of the iceberg. Farm suicides, whether owing to purely agricultural

reasons like crop failure, or the complex pressures on an Indian farmer, must be tackled seriously

on the basis of a comprehensive examination of the causative factors, and the context.

UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY HEALTH AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Community health is a process of enabling people to exercise collectively their responsibility for

their own health and to demand health as their right. It involves the increasing of the individual,

family and community autonomy over health and over organisations, means, opportunities,

knowledge, skills and supportive structures that make health possible. (CHC Team, 1989)

Public health is more technical field. It involves epidemiological investigations to produce

evidence based information. The social influences on public health include the current paradigm

of individual responsibility and independence, as opposed to community-based values.

Community health deals with translating the information obtained into a meaningful action.

Meaningful action means, the information of the community, by the community and for the

community. Community is involved in the decision making right from the conception of the

problem. It is a political stand taken to emphasise the democratic values. Community is

empowered to make their informed decisions.

Public health also works towards translatory reseach and action. For example, in case of Malaria,

the preventive strategy is to provide insecticide treated nets. This is based on evidence based

research results. One of the preventive startegies for HIV/AIDS is use of condoms by men. In both

these cases, the preventive strategies are accepted methods of disease transimission. But, in

reality, this strategy has met with many challenges and is proved to be partially successful. Use of

condoms has many psychosocial factors associated with it. Some people might object to the use of

latex or some aren’t comfirtable using it.

In case of Malaria, particularly among the indigenous communities of Madhya Pradesh, it was

observed that Malaria still continued to be prevalent despite governement providing insecticide

treated nets. After careful observations, it was seen that the Bharia and other indigenous

communities didn’t use the nets. Most of these people were engaged in collecting Mahua 23. They

would go into the forest during April and stay there coinciding with the blossoming of Mahua

flower. During these times, it was observed they wouldn’t use the nets or some would use them to

cover the trees to collect the flowers into the net. Malaria incidence peaked during April and was

23 Mahua- Madhuca indica, a flower found in the forests of central India. It is used for making liquor.

24

mainly seen in those who ventured into forests to collect flowers. (Collective notes, 2015). It was

clear about the causative relationship between Malaria peaking during April and the activites of

the people. This discovery was possible bacause, there was an effort to understand the causality

from the community point of view. This falls in the room 4 of Johari window. It was unknown to

both people and the investigators why nets failed to prevent Malaria.

Community health focusses on this aspect of why certain thing fails and certain things work. It

involves careful observation of the community from a sociological and anthropological lens to

understand the community dynamics. It is that effort to make the community to feel that health

is a fundamental right and they are entitled to basic primary care. It is a medium in which health

is advocated by the community theemselves. The community is placed at the cetre of an issue and

helped to solve the problem through action that is locally relevant with an ultimate aim of ‘Health

for all’. Community health recognises that health is not just biomedical construct, but the cause of

health issues are rooted outside the framework of medical personnel and infrastructure. It weighs

heavily on the social and structural determinants of health.

Individuals recognised for their social skills are identfied from the community and are used as

change agents. Dais24, health workers, community leaders such as local health healers, village

heads and indigenous community chiefs are engaged continuosly to communitise health. There is

collective dimension and consensus building within the community to analyse the situationa and

prioritise issues. Community health action emerges from contect of wider sociao-economic,

cultural process of change and aims at an integrated approach to reduce duplication of the work,

and establishes interactive communication to disseminate community health perspectives into

masss education. A dialogue is established with key governement planners, policy makers and

community members and feedback is valued to continuosly modify the strategies. Community

health is a movement overviewing community empowerment especially marginalised groups,

sharing of resources, networking, socio-epidemiological approach to priority setting to solves

issues and linking with other social movements to garner support and stand in solidarity.

(Community Health Cell-Red book, 2011)

Axioms of Community Health was facilitated by Mr Prasanna Kumar Saligrama and Mr

Chander S J. The axioms or principles of Community Health is a summary of axioms derived from

the reflection of SOCHARA team. The axioms are a result of analysis built on grounded theory to

evolve alternative approach to understand and practice community health. The alternative

approach to community health that emerged became known as ‘social paradigm of health’ and

was rooted in the framework of rights and responsibilities. (Cell, 2011)

1.

Rights and Responsibilities: In Gudalur, the adivasis demanded for health care and as a

result of it, they have an excellent model of community health programme. (Fieldnotes,

2015) It is embodied in the Health Promotion concept. ‘The process of enabling people, to

exercise collectively their responsibility, to their own health and demand health as a right’.

2. Autonomy over Health: Manikantan, who was a health worker and now working as lab

technician at ASHWINI mentioned that, in his childhood, they had come across many

deaths. Once he became a health worker, he realised it was easy to prevent many deaths

through simple measures and vaccinations. He along with other highly motivated young

adivasis worked at villages to improve the health status. When they realised that some

24 Dai is the traditional midwife

25

deaths weren’t preventable with the existing infrastructure and added discrimination at

public health care facilities, they realised the need to have a hospital for themselves. This

autonomy for self-care and taking health matters into their hands is what community

health aims at. The community members explored the opportunities, used their existing

knowledge and took support from others to make health possible. (Fieldnotes, 2015)

3. Integration of Health and development activities: Community health approach includes

attempt to integrate health with development activities including education, agricultural

extension and income generation programmes. Gudalur is a typical example of

community development integrated with health activities. It all started as land rights

movement and community health came later. ACCORD felt the need for a school based

on alternative model and value based education, tea was grown in the land reclaimed,

soap making and honey processing and selling in fair trade market. All these development

activities complimented health. The health programme was a comprehensive approach

oriented at preventive and curative services. The local indigenous healers are encouraged

to be a part of the health system. Some of the dais were trained to be health workers.

Community based health insurance was implemented to sustain health programme. (N

Devadasan, 2004) Adivasis are organized into groups at village level to form sanghas for

increased involvement and participation of the community through formal organization

(AMS), health team, finance team, education team, etc. (Fieldnotes, 2015)

4. Decentralised democracy at community level: This value system pervades the interaction

between the community and health action initiators. A non-hierarchical, participatory,

people centred, team building and empowering ethos built in the system is the

community health approach.

5. Equity and Empowering community beyond social conflicts: The system should be

inclusive and equitable. It should reach out to the marginalized. The Kaattunayakans

consider Bettakurumbas and Panniya25 group as inferior, but the community health

programme at ASHWINI is impartial and involves all sections of the society even the nonindigenous group. ACCORD, AMS and ASHWINI recognizes the cultural differences