RF_WH_11_4_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

VJH 1^1

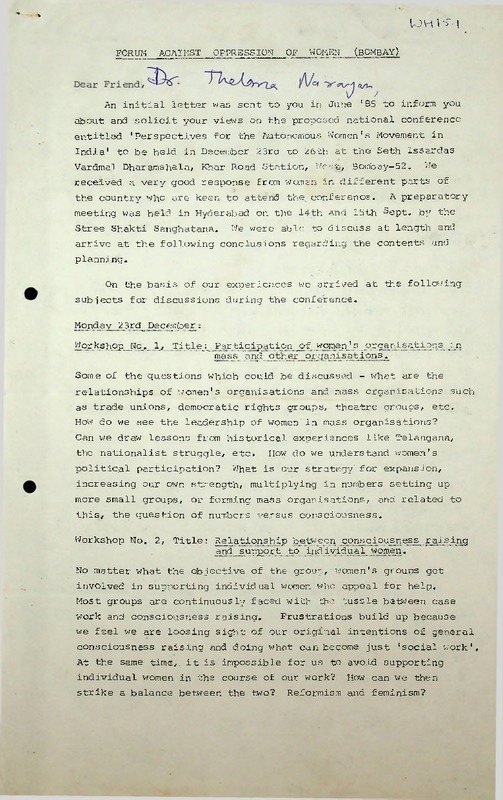

FORUM

AGAINST

OPPRESSION

OF

WOMEN

(BOMBAY)

An initial letter was sent to you in June '85 to inform you

about and solicit your views on the proposed national conference

entitled 'Perspectives for the Autonomous Women's Movement in

India1 to be held in December 23rd to 26th at the Seth Issardas

Vardmal Dharamshala, Khar Road Station, West, Bombay-52.

We

received a very good response from women in different parts of

the country who are keen to attend the conference.

A preparatory

meeting was held in Hyderabad on the 14th and 15th Sepp, by the

Stree Shakti Sanghatana.

We were able to discuss at length and

arrive at the following conclusions regarding the contents and

planning.

On the basis of our experiences we arrived at the following

subjects for discussions during the conference.

Monday _ 2 3rd_ Decejrtoer :

Workshop_No_._ 1_, Titlej-.Participationjof J?omenj s.. pr.gani.saizions^ ~in

mass an_d_ other organisations.

Some of the questions which could be discussed - what are the

relationships of women's organisations and mass organisations such

as trade unions, democratic rights groups, theatre groups, etc.

How do we see the leadership of women in mass organisations?

Can we draw lessons from historical experiences like Telangana,

the nationalist struggle, etc.

political participation?

How do we understand women's

What is our strategy' for expansion,

increasing our own strength, multiplying in numbers setting up

more small groups, or forming mass organisations, and related to

this, the question of numbers versus consciousness.

Workshop No. 2, Title: Relationship between consciousness...r_ai_s_i_ng

and support to individual-women.

No matter what the objective of the group, women's groups get

involved in supporting individual women who appeal for help.

Most groups are continuously faced with the tussle between case

work and consciousness raising.

Frustrations build up because

we feel we are loosing sight of our original intentions of general

consciousness raising and doing what can become just ‘social work'.

At the same time,, it is impossible for us to avoid supporting

individual women in the course of our work?

strike a balance between the two?

How can we then

Reformism and feminism?

2

nrrt anwny Whfr yy3snnit

ygn3

ggt ^T3<T4 if 3TTWT ¥35

Itf 353- -.PT-J 2JT ton 3TJTW

HT/T

3i i’q'i cn$) Tynr" Ywt qy gt-rai cf yry^tn tqgRt my y arm am tnnry yarn? i

u? ntm tmkrm t 3^ w

gwyra cnyyw ofnw, my ntg ttYn [qtwn

yoo 043 y gtw I r gir gu qy ggn stw zqfn<n Twr i tmrwY

WiyYt rcP?

I 611 q. 35 w WhfcT fFT^HTH ?« ait? ?4 twttr W Wf^W

amiYuH TWT qr f cHt W%

YmytciYan iMu YcW nt I

mYmy wf t Twa ; =

-wq i,! 33 ‘feray t yw warm :

gfhfe : arryrnioyty yrtY trnnt nr Ygmrr nrtt mien arry arrwicH nt ®Y

mngmlWr^t gw rninn3 Trent q gmT??^ try wt Tram g ? arryminTi't tiW

a^ttY amang YcbciMY g ? wr gy tti tt any mg -tine arrdwp Vitfgrr'w

3Rwf t n? ttn w g ? artygr

yrmciStii ug??Fi 35 yp-y wy w ^yry g ?

gyrVY wft py am fteor ygr^t ? w gy wk? unKfczjT gt yrtgy

<jt "jyfr urnjcfY aft ypfr yrfgy ?

crwrq- :- 3 : sfhfe : ynjtn ypy

yfgyraihiy tfgny

yt cytyyt 35 ...

wi.

W^icH yry'Y yqgy 3ttt ^y.ayyr 35H sfr Wny a#yr gt3 wp cfr anwfr

yWraY (w erra-ygryr ^cr

1 wyy

gtry tw ^rr gg g - w gy

>

w w yrq 3yuT yrfY gtfiTw' qyy 1 w gy wi wwW yy yif g yr

ggy y£ i ?yrgWryt wf any ytty wfr cirtf y gyyyW gy

wrt ?

ynciq r ,3y Ygfray .’ y^yrly - ?

yhfe : mi® ?nv wh trT

frafr ygr^ wWf w g am fcryryr

qyy g ymr 1 gyy tnv gy MW yTpyrrciy gwrrci aayy g u&

^yy.yre?

n'Ycf gwry^T gyqrn yRWWi

rfWt qg^tryy

fcP? yry any g { yr nt nryT

VJ

o

yiunt n

ww yyyyyt lrt <it nt am ww-ti yrn nyt g^f t yht

yg tcyrr g r yfat 35 qrnt any ymW ntrt ng tyrr g 1 that

3

qrat any yntr

w g ? ^yr33nyWgtr ^5 cfty^i ygg ^Y 3jy wt ygr g i gt gy 3vr

w gy uiHcift^ nt?t3nra Yyyy, wr

y35%ty :- «

?

<w : ^nttnynr nY Tntfant.

anny 2r wq tg ,

?

cy?WY gttrnnt gyrar tY tnwa garr g 1 gy

|v

...■••

3

Tuesday~24th December;

Workshop No. 3, Title:

Communication Work.

One of the main tasks of women's groups have been to communicate

their views and work through the use of different forms of media

like the press, skits, and songs.

They have either created their

own alternative channels of communication or made use of main

stream media by building contacts with sympathetic persons.

What are the pros and cons of using both types of channels?

Secondly, the communication between women's groups is sparse and

infrequent.

working?

Can an internal newsletter facilitate better net

How can it be set up in a democratic and collective

manner?

Workshop No. 4, Title: Politics of personal qrcwth.

Through participation in groups we have grown as persons, become

conscious, got strength, confidence and the courage to act.

While

we are aware of this process, we usually discuss it personally

and have an exchange of support and rapport at an individual-level.

There is much that we can learn and draw out from this process of

pereonal/political growth if it is made visible and articulated.

Can we pool our experiences and link our private and public

struggles?

Wednesday 25thDecember:

Workshop No. 5, Title: Structure, methods and intra group dynamics

of women's groups.

Women's groups are attempting to work in different ways, using

nonhierarchial and collective methods.

Group structure and

methods of functioning are often linked with composition and

beliefs. These alternative forms have at times created problems

between members of groups, disillusionment, and splits.

With

out personalising such conflicts, can we understand how to deal

with them?

How can we take into account efficiency, responsibility

hierarchy and collective functioning?

Workshop No. 6, Title: Relationship with the State.

It becomes necessary to interact with the police, courts and

government.

Often we are in conflict wide them and sometimes we

also take their help and/or try to influence them.

E.g. the

4

g-Rft rRr of I, go arrWfWRf or g, fipfa wd 30 eft gF-nrT TgT^jcr

W#

Reft g F gifTR Th# 3TTV TRIO# tWRR 3H## 3fr t|trf g# gif ¥35

OB #0 cRci t F W gq g-BR 3H#f W 3FI4HJKN 3R. gR# <cT# 3FT? OR#

g ?

tW# #g

wr,t

#cbr : g#tr - 4

thfe : tt# ^et 35 crtctrf etxr,^rjq^TtT anR aWfro trati-^ragR

TRt #TcH 3RR cTR cR#5

tlT^ 35T-F Tu g F JT-T# I W 3FTR 3R 35

for otr th th m^brio)’ 3ig I j.wt #r g i gtf 03 rh hrt#

trt 35 Tdeii 41

#¥ 'i</l tttjtv jMT

g [ 'fBrrW ci) so) g rtr- 3Rt o yuo) sos-Ho) uiw ci

Rgt ? gg TW CRT# 3O$fO/fa#Wt 3# TcflVcT RTOT 3TR tiTqtgg qTtfoth#

?T3kt

Jr

?

I

: ttr# Tytcft.

crwhr- q

WYvPifr-no)

tr tr

##### sttr crtr)t ;urq qqr q-ggr g f

gq I R RFO IWTR fF^ 3fr gfcR g cF^ q53fr gif JHcf 30 ?Hc|3rft| I Heft' OrMl

wr g r J3'F gRicid i - ?rw

owwoTrf uWrn?

3RT Rf'lVTT g ? gif tcW iJWtl ciTRR'Y Tf'FW Wt

Wft^RRTlRf-

rjrtq b-ort

gr

R^WR H 3TR?^ titgtf,

gY?cf/#ggT gHcJfl 3fR RRtN^FT 3R ^3cF g F

fRoR

BT^tFIWhpT 3ft^f if cfJ^T cTTT R% cTT gif B4RT RFcRF artRTcg 3&

3w;

?

'kw? : TcFWq tgEijT >R gwhr : tMT mf^,ggvRft,TJiWi,

OTOftwl MI q jCRi? RHFnR gc3T?g RR gR$f

4

traTgt O O TTRflR |ilwT

g?RO 3RJWF cR ffwf g ?

W : RRVciw^RFg T® Rtg Rs cuTrt# cjih^era fgv dfgRg Trgd,)Wf or

gW wtr W gjcti

JRrMt gnif Rf rA gt^F l tfgcfr [TRnfT] croXTir

TRt 3FRTRR W)W '0,01^ R^UTR RR 4 W lyffRi fPTcRT W^TR RR y,

Rirt^ [w<] rWtt w 3, tonrrT sr-rtrfr]

w

? o qKff wr

F gif cRfr RR'Wsot r)r?T cIRR RRRT 3)0^1 qcF g F urt rRRf”- OW35T

T?RT'' tFTBcf g cf TrRR,? cTO g>

&5F

rMY

)foi g 3TR 3Brf ?HRl

?oo

3TTT 3fcA UT?J 3RTT 3oo OWt TgcFW tcf¥ pF cR 3TTR F

uhfRR :- cfteH gif RRt tftcH gif RWt tFRT?go Tuf^gltt

I RtffgV gzORFg if

ff $TcHq5 Tgv ■?• 500 )f ?n’ two ^RT R1RT J?W

f RR'T 3FCUTRR

WMt

tqrfvt WT 3FMt cW gff cRgO TgV R- ^00/-

OcF g F

35R gTel g F gif 30^ TOTcfT

,.

. ..

5

the government has proposed a series of welfare measures; what is

our response to them?

How do .we, if at all, intend to influence

government policy regarding job reservations, population, hostels

and shelters?

Secondly, how real is the danger of co-optation

and how can we deal with it.

Thursday 26th December:

Workshop on 'specific issues like personal law, health and environ

ment, communalism, work, and any other suggested by the partici

pants.

Can we plan national campaigns around some issues?

Papers:

Women’s groups and not individuals should prepare notes which will

pose problems and raise questions i.e. act as catalysts for discu

ssion within the workshops.

Some of the topics were picked up by

the groups at Hyderabad like Saheli chose no.2, FOAW no. 5, Stree

Shakti Sanghatana no. 4, Women’s Centre no. 3, and Chingari no. 1.

All groups are invited to prepare such notes.

in advance your prefered topic.

Please let us know

The group which decides to work

on ’posing the problem1 notes should send in their work by

December 1st.

They should also bring 300 copies for distribution..

Funds:

As part of the collective responsibility for organising the

conference, the groups present in Hyderabad have pledged money

from Rs. 300 to 500. The Forum has already raised, through dona

tions ard

loans

some Rs. 2500 which has been utilised so far

for reserving the hall, postage, cyclostvling etc.

'We suggest

that each group raise at least Rs. 100 which they must forward

to us by mid November.

Invitations:

It was decided to limit ourselves to inviting groups with a

primary commitment to activism.

Only women are to participate.

Please let us know how many members of your group can come.

registration fee is Rs. 10/- per member.

travel or food expenses.

The

We are unable to provide

Looking forward to.hearing from you soon.

With regards

FAOW

6

t^p? iRTO

3TOT Wf W TO ?0o/- [TOT] gtT

3TO I

anro^r : f^rfro toM toftoto totohT <E bt ?u fttotototo Eprrror ftot

wi qtgmro Tgw

cf wfr g r ®w gir totftoE f® aiwb toitoto Wr ?toto tot

TOTOTO7 3fT^i I WHTOT TOfTO^T qfr g

eMyiTei i

< tot tototo

jttwrt to% toito tf

HTOt Y TF^[

[g] ?o/- [^T] gij- <J|W

iTOTb?7 ^tottotf fttof ThcIcTt t1

JTOJTOTOTOE SnFTTF,

arMTcHi (TTU,

totoY

3TOtftoto YrorrJY

glTOT TO

(%?,

5 013 - £ffw TOTTO-TO,

totto w,mwcrr,

kfnTT^I

yoo oTO.

^cttof w ;

0^ ‘‘fW TOT | I

? ] f£lTOFY~TOlcI <TTO TO TOTO

3 ] fTFT Sf'lcFM fiTTFT (TFTT -ycHT TO I

5 ] 3FTWTO 3TTO g? TT^hr, gt^oT Bh^ra T?MT< fcTTO 3iTTO^

crr^Wl ‘fWEr arrwr

y]

4

unrofr I

<r# gWt r

] 3TTW a UfY ufc^ JITOT T

oe qT TO cFTfTWT BTcI TF ?6 fWcF

I TO

TOg

3TT 3TTWt TR^ TO UT TT‘?TOF^ TTOT eTETT i

$ ] wfE ^5 W[¥ whft OTOfl+t gr£r cfr g I MtTH gT^I I

u] 3®(h:'iei ,ti i TeTOcfj ?gv ca pti twi I

T^tW :?TOg : ?0

\3

crN b\ : to

?3 WT^TO

?

g g^WTO

5

vf 5-30 TOF Tt S^Y

uihcp)

3 •?o

.

4T

oo (jMr,

WT : B TOO Y TOTO TOmtcTO wf^TO.

§w : TbtoT toto ai^uftro totoi

toE

TU^'TOiTOt TOtrorerot vg^fT i toto ;Ti ^tototoE

fuATqnroY cfrl TO'/TOcfl vrofE i anro wrwft ?tw arotwETro gfto toY totot ‘^’ttot

TOTTO^TcTO TOTfjro : ^^^-TOfgJ^TCcij,^,^ gTOT?q Of¥ BTOTOT I ijfE 3TITO -

TOTO fnTO^fcTO QTOfcTOY tdV TZfr

I

.

= 7 =

Schedule of the day:

Workshops

Morning

: 10.00 to 12.00

Afternoon

: 12.00 to

1.00 to

1.00

3.00

Lunch

Workshops (continuation)

3.00 to

3.30 to

3.30

5.30

Tea

Plenary session

5.30 to

onwards

Cultural items

Evening

PS:

:

(i) Each participant will be able to'attend only one workshop

a day. Do decide in advance.

(±1) Translations from and to Hindi and English will be

arranged. Participants will have to make arrangements

for other languages.

Administrative details:

1.

Accomodation will be provided at the site of the conference.

2.

Please bring your own beddings.

3.

A map shewing locations of different restaurants will be

distributed.

4.

Return tickets should, be booked by the participants themselves.

5.

For those who might want to come early on the 22nd of December/

a room is booked for their accomodation at the same place.

Those who want to stay behind can shift to the Women's Centre.

6.

There is a seperate room for children.

7.

Tables will be provided for distribution of literature etc.

Cult.ural Items :

All groups are welcome to bring their posters, audio visuals,

skits, and songs for the evening cultural session.

Guide, to_the. cpnference ha 1 Ij

From Bombay Central Station: Catch a local train (slow) going

towards Andheri or Borivli and disembark at Khar Road Station. Ask

for the West side of the station and the Seth Issardas Hall.

From Bombay V.T. Station: Catch a local Harbour Line train for

Andheri, get off at Khar Road Station. Ask for the West side and

the Seth Issardas Hall. If your incoming train halts at Borivli

or Dadar you can get off there too, and follow the above instructions.

If in trouble call the Hall after 22nd Dec., 8.00 a.m. Phone:531087

or

Arati

:

Nandita:

4225067,

356213,

Nirmala

Jessica

:

:

Address:

Forum Against Oppression of Women,

C/o. Women's Centre,

Yasmeen Apartments, Yeshwant Hagar,

Vakola, Santa Cruz, (East,

BOMBAY - 400 055.

213431,

6422924.

= a «=

ntrart fra ra arrW J-Tpfcm

: sib# cjt ntftnnt ufi nareft’ rat rftft rari3c5 [fhra] fn rasra

nrat

arratn sn? nrat r qtrwft arra "nn <w^ra fra" 3rr<rr f r

X

---------------------cfWt t :

nra rait i

Entra] rat^Vt# ark nrnt frar nnra tfiratn

arrrat tn fhfl nnt; ai^R-f ut rara_

fefrads’ ar? frafr 11 ffftwt sitt trnra

arrwr

?Bcft f r uf wr

tfhft rat wtw

eRt fhft i affcrfY t airrat q'r’TW jt erak errant ^hit-rat, rarity $3

[fira?] s3 eWt gW 1

*

c® TfSsrs ei eft fra ra f'-r rafra ftfjp? f qrar - 4 3 ? 0 <r o jtt nt

raft arrawY WW nv t cratW^t tra ftrnv 1

arrant : a ra 4 0 ? u

raf nr : ra

n a

iMnr - n a « ? ?

trWr ra y ra u y

ECUMENICAL CHRISTIAN CENTRE, WHITEFIELD, BINGALORE

*

*

*

,

Emerging

Trends in women's Movements in India

November 27 - 30, 1985

1.

C Hi Lakshmi

C/o gamithi Office

Tarlupadu p ,0 .

prate, sam Di st

A. P .

2.

Rita Roy & J. Jaya

gtree Jagruti Samithi

103 , 1st Floor

3.

Usha Kiran

25, Hiudin Road

Ulsoor

Bangalore - 560 Oh 2

h.

Sr. Augustina

Ebly Cross Institute

Hajari bag

Bihar

5.

MJi. Flower Mary

S.M.K' S Bhavan

puthukkadai p .0 .

K.K. Dist, Tamil Nadu

6.

Hr era Nawaz

39, Ulsoor Road

Bangalore - 560 Oh-2

7.

Tara M.S. & Nit ya

National Institute & public

Co-operation and child

development

293, 39th Cross VIII Block

Jayanagar

Bangalore

8.

Annie lose ph

W N D (Woman for national

Dev.)

1 6, Bodford Lane

Calcutta - 700 01 6

9.

Dr. prabha Mahale

Reader

Anthropology Dcp?.rtment

Karnataka University

Dharwad - 580 003

10.

Sa kun tala Narasimhan

810, Bhaskara , T.I.F.R.

Colony

Homi Bhabha Road

Bombay - h-00 005

11.

shakuntala R. Thomas

12.

BUILd

11, sujata Co-opiatiye society

1st Floor, S.V. Road

Bandra, Bombay - h-00 050

13.

N.s. Krishnakumari

Research Co-ordinator

No. 17, Miller's Road

Jaint women's programme

Bangalore - 560 Oh 6

ih.

Saraswathi

Joint women's programme

17, Miller's Road

Bangalore - - 560 Oh-6

15.

Madhu Bhushan

Vimochana

1

P .0 . Box h6o5

Bangalore -560 Oh-6

16.

Mrs. N .G, Bhuvane swari

Advocate

No. $ 8, Venkier street

Kondithope

Madras - 600 079

17.

Colette R.G.s.

(Women's Voice)

Good Shepherd Convent

Mu seem Road

Bangalore -560 025

18.

G.Jfma Rani

No. 25, Ben son'A 'Cross

Bensom Town

Bangalore -560 Oh-6

Ammu Ba la chand ran

Advocate

17, Dr. Muniappa Road

Kilpauk

Madras - 600 010

2

Voice)

19 • T he Im Jfa. ra yan

326, 5 th Main

Koramangala 1 st Block

Bangalore -560 034

20.

Maya M.K . (Women's

193, Up stairs

3rd Main Road

Chamrajpet

Bangalore - 560 018

21 . Bharati Dubey

97/' 1A, Hazra Road

Calcutta - 700 026

22.

23. Thomas Kocherry

19/1005 A,

S J) -P .Y. Road

palluruthy

Cochin - 682 006

Kerala

24.

Mrs. Gopa Riman

J. W . P .

17th Mille r 1 s Road

Bangalore - 560 046

Sr. patricia Kuruvinakunnel

Medical Mission Sisters

Mampally

Anjengo p .0 •

Trivandrum - 695 309

Kerala’’

26.

25. Manini

A Forum for progressive Women

No. 15, IV N. Block

Rajajinn gar

Bangalore - 560 010

phone No. -358127

28.

27. Israth

Post Box No 32

Hassan

29 • Leticia pires

Supc r int n ie n t

State Homo

Dept, of social Welfare

Behind C.nce-r Hospital

Hosur Road

FANG*. LORE 560 028

30,.

Madhu Kishwar

C/o Manushi

C /202 Lajpat Nagar I,

New Delhi - 110 024

B. Padmvathi Rao

president Karnataka

Women's Teachers Assn.

Karnataka Federation of

Teachers As soc s.

29, Benson Ro d

Bangalore 560 0 4 6

flB

Off: 70247 Res;573^9O

H. Gn-nampal

C D.P.0 ? (eentral)

39, I'lnd Floor Corporation

Shopping Complex

J .C . Road

Bang lore 560 002 ••

31 . Banu Mustag

4348 Vallabhai Road

Hassan

33. Sot. M. Vijaya

Information & publicity

0 ffice

3rd Floor

Multistoried Building

BANGALORE 560 001

Corin Kumar

Vimochana

P.O. Box 46o5

Bangalore - 560 046

34.

K. Nirmala

D/o Kasivreddy

I irlupadu

p.arakaram 523 332

A. P.

35. A Rexceline Rani

Jeyakumari & -Lid-win Mary .

C/o Bumad Fatima

Society for Rural Education

&■Development

Kallaru, perumuchi p .0 .

Arkkon .ra 63? 001

36.

Anjali Son

Deputy programme Co-ordinator

Luthern World Service (i)

84. suresh Sarker Ro d

Enrally

Calcutta 14

37. Dr. Sorojini p. Chawalar

prof, of Kannada

SIMVS Arts & ftomm. College

for Women

Jayachniaraj Hagar

Hubli 580 020

38.

pro mi la Dan Java te

K1 Sharadashram

Bhavani Shankar Road

Bombay 28. Tel: 4225^6

Ecumenical Christian ( Marjorie David

Centre

( Ranjit gathyrraj

’Aiitcfield, Bang-lore ( G.S. Yalsangi

E .C £ . Staff

Rev. Dr. K .C. Abr-.-.ham

Mrs. Dr . A . Abraham

Susy Nellithanam

EMERGING TRENDS IM WIEN'S MOVEMENTS IN INDIA

WOMEN

AND

RELIGION

or

CAN THE WOMEN'S MOVEMENT BECOME AN ANTI-COMMUNALIST FORCE?

1.

(j<,

Intro duction

During the International Women's Decade, the question of women and reli

gion did not come to the fore front much.

The main emphasis was on

women's deteriorating economic situation, declining work opportunities,

victimisation due to technological modernisation, self-help through self

employment schemes and on sexual and other violence against women, like

rape, wife beating, dowry deaths and the like.

Attention was also paid

to women's health situation, family planning schemes, the effects of

certain contraceptives like IUD's, depo-pravera and NET-EN etc.

This does not come as a surprise since patriarchy in the feminist debate

has been understood as exploitation of a woma's labour, sexuality and

fertility.

It is therefore only logical that primary attention should go

to the economic aspects and to the actual physical subjugation of women.

The only aspect where religion has come into the picture is the demand

for a secular family code which has been raised on and off and short of

this battles are today fought for Muslim women's rights to maintenance,

for the right of Christian women to get a divorce, against extremes of

discrimination in inheritance rights like eg. the Travancore Christian

Succession Act.

The demand for a secular Civil Code extending to matters of marriage and

succession is in no way new.

Baba Sahib Ambedkar had made this point

strongly and it has been argued that diversity in family laws violates,

the principle of Fundamental Rights that there should be no discrimination

between citizens.

The Report of the Committee on the Status of Women in

India which was published in 1975 by the Central Goverrment takes a very

clear stand on this matter:

’’The absence of a uniform Civil Code in the last quarter of the 20th cen

tury, 27 years after independence, is an incongruity that cannot be justi

fied with all the emphasis that is placed on secularism, science and

modernisation.

The continuance of various personal laws which accept dis

crimination between men and women violate the fundamental rights, and the

Preamble to the Constitution which promises to secure

to all citizens

’equality of status’, and is against the spirit of national integration

and secularism.

Our recommendations regarding amendments of existing laws are only ;

;

indicators of the direction in which uniformity has to be achieved.

Wo,

therefore recommend expeditious implementation of..-this-constitutional

directive by the ado_piiQ_n of a Uniform Civil Code." 1

2

However, even ten years after this recommendation, we are no inch nearer to

its implementation and only very recently, the Prime Minister made a cate

gorical statement that a secular personal law is not on any immediate

, 2

agenda.

The reason for this is not far to see;

Over the last decade, communalism

has been on the increase and despite the carnage against Sikhs in Delhi,

Kanpur and many other cities, after Indira Gandhi's assassination, none of

the opposition parties found it opportune to raise the issue of communalism

during the election campaign.

It is therefore significant that one of the

most courageous voices to speak out against communalism after the anti-Sikh

3

riots was the feminist magazine Manushi. ‘ Special investigations were also

held by various women's groups into the situation of women during the anti

reservation agitation in Ahmedabad and into the way women were affected by

4

communal clashes in Bhiwandi.

These kind of inquiries are in themselves

very important but they finally do not really raise the question of religion

because they work on the assumption that religion is not really at the root

of communal conflict.

This assumption is correct, as deeper studies of communalism have borne out.

Bipan Chandra has drawn attention to the fact that communalist forces arc

usually not led by people who are in any way deeply religious and that on

the other hand people with a dimension of religious reform of any depth

would normally be anti-communalist.5

Looking back at the history of the

freedom struggle Chandra observes that "religion was neither the cause .-.or

g

the end of communalism - it was only its vehicle."

At the same time he

gives many examples how communalists opposed religious social reformers ana

vice versa.

It is therefore important to raise the question;

What is the relationship

of the women's movement to genuine religious reform?

I do believe that

this is a crucial question which has been ignored for far too long.

I

would like to define genuine religious reform as such a reform which

enables individuals and groups to participate in secular political

processes struggling for equality of all citizens and against economic,

political and cultural exploitation, without being forced to abandon the

faith dimension of their religious identity.

Besides, genuine religious

reform chrystalizos the humanist content in a religion in such a way, that

non-believers or people of other faiths can relate to this humanist content

in their own right .

This latter dimension is an indispensable part of

creating a rich secular culture.

This is a question which has not been raised in depth by the women’s move

ment, probably for three reasons;

First, the question of genuine religious

reform is normally left out of the general debate on secularism.

Religion

. . 3

3

is normally 'simply declared to be an obscurantist hang-over which needs to be

discarded.

This year's Independence Day Issue of the government sponsored

journal To j ana under the title "Why live with Nonsense?" is a striking

7

example of this tendency.

Secondly, women as primary victims of orthodox religion have good reasons

to be resentful of religion in general.

It is therefore not surprising that

in the wake of the Delhi riots the Sahel! newsletter presented a very

simplified reductionist view on Religion and Women which ends with the

appeal:

"It is we who have to stop believing in gods and start believing

in ourselves, our inalienable rights to a decent life on this earth.

Our

rituals have to be taken over by actions which lead to this.

Our God has

„8

to be replaced by our love for humanity and our hatred for injustices.

A demonstration in Delhi on March 8 (International Wbrking Women's Day)

sponsored by different women's organisations expressed their views on

religion in a similar vein and was only questioned by a thoughtful article

9

by Ruth Vanita in Manushi.

Thirdly, since women due to their position in society have rarely been in

the fore front of ideological production and especially not of religious

ideological production.

Women have rarely been theologians.

been famous mystics or poetesses.

A few have

It is therefore not surprising if the

domain of religious reform has normally remained controlled by enlightened

male intellectuals who at times could have been creative enough to rethink

women's position in their respective religions.

The question is to which

extent women actively need to interfere with religious ideological pro lucti

2.,

Women and Religious Reform in the Freedom Struggle

It is difficult to comment on the question of women and religious reform in

the freedom struggle at any depth, largely because of the fact that most

writings which deal with the Hindu renascence are in no way interested in

the women's question.

Women's studies on this period are on the way, but

most of them have not yet been published.

What I am saying here is there

fore extremely tentative and very-much derived from secondary sources.

Following Bipan Chandra's analysis it can be said that communalism developed

under conditions of "economic backwardness, interests of the semi-feudal,

jagirdari classes and strata, the precarious economic condition of the middle

classes, social cleavages within Indian society, its heterogeneous and multi

faceted cultural character and the ideological-political weaknesses of the

nationalist forces."10 These conditions were aggravated by the colonial

economy and polity and by the desperate struggle for jobs among the middle

classes.

The latter factor helped communalism to acquire a real mass base.

The communalist ferment was ideologically asserting religious orthodoxy and

thus glossing over class differences, caste discrimination and oppression

of women.

. . 4

4

On the other hand, there was a certain ferment of religious reform, expressed

eg. in the Ar ya Samaj, which was prepared to incorporate a certain amount of

social justice and women's concerns but would go back on it's stand when

getting involved in communal politics.

As far as social reform on problems

of caste or women was concerned, the communalist ferment again and again took

to "iolently reactionary options.

This is true for Hindu and Muslim-commu-

nalism alike.

The same is true of the nitremist part of the freedom movement which in

contrast to communalism proper was clearly anti-colonial but on the base

of a religious revivalism which, developing a mythical concept of the

motherland, was prepared to defend caste, joint family and communal village

society as precious expressions of ancient Indian heritage based on love

11

and collectivity as opposed to Western individualism and competition.

Apart from their obscurantist image of the "Mothe l: which was based on

Durga or Kali and implied an idea of motherhood vhich would not have any

openings towards-alternative women's roles, in social reality, their in

clination towards violent struggle would also n-i facilitate women's

participation.

On the other hand, the reformism of the moderates which implied a stand

against "social evils'- like caste, chile marriage and sati and would advocate

education for women, did not achieve much mass appeal.

It was Gandhi's

specific brand of religious revivalism combined with social reforms and a

concrete method of action which captured the imagination of the masses and

provided a base for broad women's m bilisation and participation in the

political struggle.

Tn a recent article "Gandhi on Women" Madhu Kishwar has analysed Gandhi's

12

views on women in great detailThough she does not raise the question

of religious reform, anti-communalism and a feminist perspective in a direct

way, it becomes abundantly clear from her analysis that this connection

exists. Gandhi's view on tradition was: "It is good to swim in the waters

13

of tradition, but to sink in them is suicide.1'’

Though Gandhi originally

believed in a fairly conventional sexual division of labour, ascribing women

sovereignty in the house and leaving the domain of political struggle to

men, the actual need to involve women in mass satyagraha and the bold parti

cipation of women in large numbers forced him to change his views on women

1a

and housework or women as property holders " and his appeal to personal

courage and sense of suffering set free an enormous potential.

The in

teresting aspect is that Gandhi appealed to women as independent individuals.

Due to his belief in brahmacharya he ascribed to women the right to say no

to sexual controls even of their husbands.

Though he saw

women primarily

as wives and mothers he inculcated in women the right to resist.

Madhu

Kishwar emphasises Gandhi's main contribution to the cause of women as "his

absolute and unequivocal insistence on their personal dignity and autonomy

5

in the family and society.While he used the traditional symbols of Sita

and Draupadi for women to emulate he gave these symbols a vigorous new life,

a world apart from the commonly accepted lifeless stereotypes of sub-servience.

He constantly deviated from religious stereotypes in a very significant way.

While his emphasis on brahmacharya and his appeal not to make women sex

objects did facilitate women's freedom of movement he did not fall into the

trap of picturing women in the traditional Hindu way as seductresses luring

the tapasvi away from his sacred pursuits.

His exhortations went chiefly

against men's aggressive attitude towards women.

I agree with the way how

Madhu Kishwar differentiates Gandhi's contribution from the 19th century

reformers;

"The most crucial difference is that he does not see women as

objects of reform, as helpless creatures deserving charitable concern.

Instead, he sees them as active, self-conscious agents of social change.

His concern is not limited to bringing about change in selected areas of

social life, such as education and marriage as a way of regenerating Indian

society, as was that of most 19th century social reformers.

He is primarily

concerned with bringing about radical social reconstruction.

While Gandhi's appeal to religious sentiment is often seen as somewhat obscu

rantist if not bordering on communalism, it is important to recognise the

vast difference between his use of religious idiom and that of the conmunalists and of the extremists in the national movement.

His objective was

not religious self-assertion but social reform integrated with the political

goal of swaraj.

Traditionally it is religion which mediates the link between personal life and

wider political concern.

world view.

-Religions spells out a way of life as well as a

In the communalist approach, the religious affiliation distorts

economic and political issues.

reactionary.

The result is socially and politically

In the enlightened approach of the moderates or in the secu

larism inspired by more westernised leaders like Nehru, there was a nationa

list appeal to overcome caste, communalism and oppression of women.

But this

appeal, since it was devoid of religious reform, could not have the same

effect in terms of transformation of personal life and social relations in

the freedom movement.

Even in the communist movement, which achieved a con

siderable mobilisation of working women, it was difficult to raise specific

17

women's issues like eg. violence against women.

Short of an autonomous

women's movement, the Gandhians approach led a long way to a real transfor

mation of women's lives and the mediation between the personal and the poli

tical by religious idiom.

While appreciating this Gandhian contribution to women's mobilisation and

actual transformation of women's lives, one has to face the difficulty that

women finally did remain in a domesticated role within the movement.

Mladhu Kishwar puts it, most women ended up as devotees.

As

This has largely

. . 6

6

to do with a profoundly moralistic approach to power which conceived of power

in any physical sense as evil.

Superior power had to be soul-power as opposed

to body power and women the exemplary sufferers, were seen as the supreme

18

vessels of soul force.

Gandhi lacked a thorough analysis of power structures

not only in terms of class but also in terms of patriarchy.

He did rot en

courage any organised constituency of women within the Congress and as a result

even high profile women leaders remained marginal to important decision making

processes.

While Gandhi was forced to adjust his ideas about women as property holders,

the importance of household labour in a woman's life and on women's political

potential over the years under the pressure of actual women's mobilisation,

he was not forced'by any organisational initiative to rethink on the question

of power nor was he forced to develop his religious imagery to go beyond indi

vidual appeals to courage and sense of suffering.

While the Gandhian movement united aspects of religious reform and women's

mobilisation in a forceful way, thus undermining the social rigidity of

communalism and rivalism, another important impulse working in a similar way

had been present in the national movement since the end of the 19th century

19

in the form of the Dalit movement.

While Gandhi’s religious imagery had

remained high caste, the Dalit movement consciously mobilised an imagery

from below.

Jyotirao Phule (1827-1890) belonged to the first generation of Indian refor

mers ruthlessly critical of the errors of the old society.

While the next

generation was more concerned with emphasising the "Hindu tradition", Phule

in his radical reform movement ruthlessly attacked Brahmin domination, un

touchability and oppression of women.

While the orthodox like Tilak opposed

women's education because it would lead to women running away from home and

refusing to marry, the liberals thou^it of "modernising" Indian society by

offering women education.

Phule went much further by establishing the link

between women's oppression, untouchability and caste.

He founded the Satya-

shodak Samaj to give the cultural transformation an organisational base.

While his movement stood for radically equalitarian values, rationalism

and truth seeking, it also had a component of religious reform.

points out:

Gail Qnvedt

"In dismissing totally the dominant religious tradition of

India, Phulo accepted the assumption that something had to be put in place:

20

even a revolutionary culture required a moral-religious centre".

Ho

formed the concept of Sarvajanik Satya Dharma (Public Religion of Truth) and

saw the world as good and holy as opposed to the Vedantic concept of seeing

it as an illusion.

God was seen as loving parent (ma-bap) and all hunans

are valued equally as God's children.

Phule laid great stress on an ecu-l,i-

tarian man-woman relationship and on an inclusive language, eg. stating

7 s

:

that ’’each and every woman and man are equal1' instead of stating that "all

21

Phulc also reinterpreted sacred religious literature, eg.

men are equal1’.

reading the nine avatars of Vishnu as stages of the Aryan conquest and using

king Bali as a counter symbol to the elite’s use of Rem, Ganapati or Kali.

While Phule's emphasis was very different from that of Gandhi because of his

strong anti-Brahmin conviction, their method of mobilisation has similarities

since it relates an emphasis of social transformation with religious and

cultural reform.

The anti-Brahmin movement in Tamil Nadu had a somewhat different approach

since it left out Dalits and based itself on middle class and middle caste

values.

While Periyar wrote a iot on the situation of women, large scale

women’s mobilisation could not be achieved and the values of "Tamil womanhood"

projected by the movement remain highly ambiguous.

The movement also lacked

a deeper aspect of religious reform since it remained exclusively rationalistic

in its original approach but later compromised with religion without trans 22

forming it.

Trying to summarise we can say that during the freedom struggle a consider

able amount of social transformation was mediated by religious reform and

that women's mobilisation benefited from this religious reform.

However,

since women were not involved in the ideological production of these reform

movements but only participated at the level of mass mobilisation, they

most of the time remained objects of patriarchal benevolence and could n/t

evolve an imagery which would have helped them to express their full aspira

tions towards transformation of patriarchal institutions.

3.

Rethinking VIbmen's Position in Religions - A Methodological Reflection

While the mainstream of the women's movement avoids to enter into the

subject beyond a general critique of religion as an oppressive force, there

is also a fringe of the movement which uses religious symbols like eg. the

women's publishing house Kali for Wbmen.

While I have not heard of similar

efforts among Muslim women, I have met individual Muslim women in the women's

movement who wish to remain believers and who try to reconcile their faith

with their religious commitment.

Among Christians, attempts to develop a

feminist theology are on the way.

The problem which arises is twofold.

On the one hand, one has to grapple

with the problem of use and reinterpretation of religious symbols in general.

On the other hand, one has to deal with the problem of the use of scriptural

sources in a way wh ich takes socio-economic historical conditions into

account.

Since use of scriptures is the most obvious and widespread method,

I would like to deal with it first.

. . 8

8

The question of use of scriptures naturally arises more in the explicitly

scriptural religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam which have been

called “religions of the book".

In Hinduism, the vast heritage of Sruti

and Smrti makes religious traditions much more complicated.

Yet, certain

scriptural sources like the Vedas, Upanishads, the Bhagavatgita or ManuSmrti are frequently referred to and also the greet epics like Mahabharata

and Ramayana are often looked at as being rather authoritative.

There is a certain tendency of religious apologetics which tries to maintain

that “originally" all religions were rather favourable for women and only

“implementation" is lagging behind.

We are reassured by quotations of Manus

“VJhere women are honoured, the gods rejoice" or the prophet Mohamed;

In such quotations, the praise for

“Paradise is at the feet of mothers".

women remains entirely abstract and the patriarchal family- relations which

from the prison of the home in which the woman is made the queen, remain

entirely unanalysed and untouched.

I would like to give a few examples from an All-India Colloquium on Ethical

and Spiritual values as the Basis of National Integration held from

22

Even though these materials are nearly

Jecember 30, 1966 -January 2, 1967.

nineteen years old, I think they are still quite valid today because our .

so-called spiritual values usually undergo very slow changes, especially if

they remain unchallenged from the side of the women's movement.

conference, women were dealt with in Section X:

home.

In the

Women, marriage and the

This is no coincidence since all our religions are sufficiently

patriarchal to see woman's place primarily in marriage and in the home.

This

aspect needs to be analysed in greater depth.

It must be said that the Hindu tradition is slightly more broad based in

this respect than Islam and upto a point Christianity, since it takes

education and women’s role in public into account.

Thus^.one may arrive

at sunmaries as the following:

“In the Vedic Age women enjoyed full freedom for learning and

even for choosing their own companions in marriage.

with the onset

of Brahminism.

A change came

The position of women gradually

declined with the rigidity of the.cas.te system and lowering of the

age of marriage.

Buddhism and Jainism also affected women adversely.

During the Golden Age of Hindu civilisation in the early fifth and

sixth centuries A.D. women enjoyed equal rights and were even allowed

to exercise public rights.

However, further seclusion of the Indian

women started with the unsettled conditions inside and invasions from

outside in the eigth century A.D.

The decline in the status of women

24

became complete with the Moghul era, as purdah came to stay." etc.

. i 9

9

The view here is clearly an idealising one because in the Vedic Age and in the

golden age of Hindu civilisation all is supposed to have been well.

Other

authors, like eg. A.S. Altekar in his book The Position of Women in Hindu

25

Civilisation

take a more unilinear view descending from the age of the

Rigveda (from 2500 to 1500 B.0.) via the age of the later Samhitas, Brahmanas

and Upanishads (1500 B.C. to 500 B.C. the age of the Sutras, Epics and early

Smritis (500 B.C. to 500 A. D^ to the age of late Smrtis, Commentators and

Digest writers (500 A. D. to 1800 A. D. ).

Here we see women's history evolving

from a virtually golden age to the present kali jrug.

Altekar's vie,.’ at least has the advantage to link the deterioration of women's

position to their situation in a specific mode of production, their role in

the production process and in the overall cultural system like caste and

religious laws.

He clearly points out that where.women have an important

role in the production process and access to education and public life, their

position is immeasurably better than in a society where women remain secluded,

confined to housework, deprived of education and restricted by rules of

purity and pollution.

Such a comparatively clear view becomes entirely obliterated by a romantic

conservatism which combines an idealised picture of religion with an entirely

bio logistic view of a woman's role.

Eg. in the above mentioned colloquiem we

find views like the following:

"The woman is the seed bed of the nation; the home is the nursery

and the country gathers the harvest.

That the hand that rocks the

cradle rules the world is not a mere truism, it is a proverb of

pregnant significance.

The child imbibes its tendencies and atti

tudes from the mother and inherits her ideals

Our ancients gave an honoured place to the woman in the domestic

set-up.

Her welfare was the concern of the father, the husband and

the son.

She was never abandoned without care and support . . .

She

enjoyed a partnership of equality with her husband; she was the saha

dharmacharee.

No religious rite would be performed without her

participating in it.

It is obvious that women enjoyed a complementary

equality with men subject to reservations arising from their natural

26

physical limitations."

It is interesting to note that this kind of conservative romanticign, con

tinued with a biologistic view of women's roles, claiming an ancient legi

timacy for women's high status is not confined to an explicitly religious

position, it can be found in secular cultural revivalism as well.

One of the

most baffling examples of this kind is C. Balasubramaniam's book; The

27

Status of Wbmen in Tamil Nadu during the Sangam Age

in which he manages to

produce a bold combination between the Golden Age theory in which women

enjoyed education and freedom of movement and the “queen of the house"

10

syndrome in which a woman is eulogised for her chastity (karpu), patience and

submissiveness.

scholars

He reproduces a large number of quotations from various

which all maintain that women were ‘'equal11 and

had an extremely

high status in the Sangam age but he never unravels the contradiction in

these quotations.

Eg;

the wife of Bhudappandiyan is praised as an erudite

scholar but she is also mentioned as the one who prefers suttee to widow

hood.

Some authors do admit that women were kept in an inferior position

but that their moral strength lay in not minding about that and in cheer

fully performing their indispensable household duties.

worshipped for their acceptance of the status quo.

Wbmcn are virtually

Balasubramaniam, commen

ting on the infrequency of suttee in Tamil Nadu takes recourse to a quote

from Manimokalai 42-47

where it is said that top class chastity would

consist of dropping dead from grief at a husbands death while,second rank

goes to women committing suttee and third rank to those widows who lead a

life of suffering.

While of course Manimekalai is a rather late source of

Buddhist inspiration, the striking fact is, that all this patriarchal and

oppressive eulogisation of women appears in a book which claims to establish

the equality of women during sangam age.

Similar tendencies can be observed in other religions as well.

Eg. it is

often stated that women have a very hi^i position in the Koran.

However,

if one looks into the matter, the presupposition on which such a statement

is made is clearly the existence and strong affirmation of the patriarchal

30

Compared to the much more violently patriarchal environnent of

family.

Arabian nomads, the reforms of the Prophet were very protective of women and

tried to give her security in the house as well as the right to remarry

after widowhood and divorce.

It is also true that due to the present day

violently patriarchal culture in many. Muslim countries, women may gain from

quoting the Koran since it is more progressive than many of the customary

laws which are actually imposed by the religious hierarchy.

However, in

Islam much more than in Hinduism, the confinement of woman to the house and

to her so-called "biological'' role as wife and mother is a constraint

which it is difficult to break through.

In Christianity, a similar conflict can be observed.

Actual preaching,

social ethics and pastoral theology have entirely focussed on the role of

woman as housewife and mother.

Quotes from St. Paul and pastoral letters

are in abundant use, pronouncing man as the head of woman, exhorting woman

to be chaste, obedient, inconspicious and silent in public.

The tendency

here is again to keep woman stuck in her role as housewife, to eulogise her

for her compliant submission, to honour her as a child bearer and child

rearer.

However, feminist theology has discovered that this is rot the whole story

at all.

While there is a trend among some feminist theologians to dump the

Old Testament or biblical theology as a whole, because of their “phallocratic"

Bk . ii

11

character - most clearly eg. in the writings of Mary Daly there is also ano

ther tendency to recapture women's history not only as a history of suffering

but as a history which has become obliterated by the fact that it is usually

the victors who

write the records.

Recapturing our forgotten contribute■ns

and interim victories is part of recording the history of our sufferings.

One of the strongest contribution in this direction is eg. the book of

31

InMemory of Her

in which the author

Elizabeth Schuessler Fiorenza:

establishes the leading role of women in the Jesus community and analyses the

systematic role back against the emerging organised forces of women.

She

shows how the patriarchal stron^iold of a male dominated hierarchy comes

into being.

Far from projecting a golden age, Schuesslor Fiorenza attempts

a materialist rewriting of early church history, documenting how the women

who had come to the fore front were slowly driven back by the culture of

patriarchy of the judaic and greek environment.

While it is not possible to go into the contents of liberation theology in

this paper, I would like to derive a few methodological principles from ray

own experiences of working in this field which may help to unclog our minds

on the question of how to deal with religious traditionj

1.

It is necessary to analyse religious sources as far as possible with

methods of materialist history writing, i.e. connecting any statement on

women with their actual position within the mode of production of the

time in which the statement is made.

It has also to be taken into

account that most religious sources and most history books have been

written by men and that this has its ideological implications of its own.

2.

Research on the position of women in religions’ cannot focus primarily on

religious laws and ethical norms which ascribe women a certain fixed

position.

Religious laws and ethical statements of this kind tend to

focus on marriage and family and the whole aspect of women’s education,

public life, contribution to economic and cultural production and of

women as a self-reliant human being tends to be narrowed down to her

contribution as wife and mother.

On the other hand, most religious

sources also know of women who have lived lives in their own rights, be

they unmarried, married or widowed and our attention has to focus on

such women's roles which allow us to develop a wider perspective.

Often

it is also necessary to draw on broader anthropological statements which

are of general humanitarian value and to wei^i them against oppressive

role ascriptions.

Eg. the biblical statement that all human beings,

women and men, arc created, in the image of God overrides other state32

ments of subordination.

3.

It is also important to understand the distortions and blatant contradic

tions in most conservative writings.

On toe one hand a golden age of free

dom and equality is projected while on the other hand women are pinned town

to a sub-ordinated life as housewives and mothers.

For putting up with the

12

contradiction, women are put on a pedestal.

Elis kind of distortion comes

indeed out of a material contradiction which manifests itself differently

in different modes of production.

The need for production of life (i. e.

child bearing and child rearing and maintenance work) vh ich is seen as

women's task in the family is in tension with the need to use woman's labour

for the production of use and exchange values which requires women's work

outside the house.

The underlying problem here is one of sexual division of

labour on the one hand and maintenance of patriarchy (control of a woman's

labour, sexuality and fertility) on the other.

Religion has been one of

the strongest forces to uphold the institution of the patriarchal family.

Religious family laws mainly serve this supreme purpose.

Likewise, patri

archal family has strengthened institutionalised religion.

To break through

this alliance is a major task which the women's movement has not even tried

to tackle.

These three guidelines which I have tried to evolve here, are up to a point

also applicable to the use of religious symbols.

It may rot always be possi

ble to fully trace the historic origins of a religious symbol but certainly

it can be analysed how a religious symbol functions in a particular social

environment or how it is appropriated by different classes.

Eg. Sita who

was the symbol of the self-sacrificing wife in the eyes cf orthodoxy, acquired

the qualities of a self-willed courageous woman in the Ge.ndhian interpreta

tion and may be used as an outright symbol of protest if seen through feminist

eyes.

Eina Agarwal, in a recent Sunday Edition cf Indian Express wrote a

very moving poem under the title "Sita speak", in which Sita is encouraged

33

to tell her side of the story.

As it is important to'go into religious texts about women which go beyond

the sanctified institution of marriage and family life, it is also important

to go into the mythological heritage of religions in order to, trace certain

cultural assumptions about women which may be quite widespread in the public

mind.

Eg. there is a widespread as sunpt ion in Tamil Culture that women are

in fact bearers of supreme power and that this power needs tp.be controlled

because it will turn destructive without control.

Thus, the power of women

is supposed to be vested in their karpu (chastity) in order to ensure male

control over women.If one takes the trouble to go throu^o the temple

myths of Tamil Nadu, one discovers an ancient layer of goddess religion in

which the goddess is a virgin or a powerful independent entity in her own

35

rights.

The stala puranas contain many versions which record the process

of subjugation of thegoddess which usually ends up in sacred marriage.

This process happens not only to the goddess but also to semi-historical figu

res like the Amasouz queen Alli.

Research into such historical backgrounds c.-.u

unearth a protest potential as yet untapped.

. . 13

13

i

Invariably, freeing women from the shackles of subordination involves making

choices.

In the same- way as we constantly hove to make choices between differ

ent roles offered in the family and in society at- large, we also have to make

choices between traditions and symbols offered:

To combine an ideal of freed? .

and equality with women's exclusive destination to be ideal wives and mothers

is possible only in a hypocritical mind which tries to bomboozle us by means

of cultural chauvinism.

Real life and liveable values involve a more painful.

process of acceptance and rejection of contents which have to be tested in

their potential to free or to oppress women.

4.

The ^uest for Secularism and Cultural Identity

While I am writing all this, I am painfully aware that the idea to delve

deeply into religious texts, myths and symbols must sound rather exotic to

most women in the women's movement.

Certainly, there are countless much more

pressing issues to be taken care of.

However, there is no doubt that the

struggle for a secular Personal Law which has priority for the women's move

ment is part of the wider struggle for a secular stete and national culture.

36

This connection has been forcefully drawn by some of the feminist writers,

however, without going into a full analysis of what goes into the building

of a secular culture.

The whole argument tends to focus on the legal aspect

only by promoting the- demand for a secular ciyil code and publicising it

widely.

However worthy of support this demand certainly is, its implementation gets

stuck precisely because of the subtle or not so subtle pressure of majority

communalisra which went into a cataclysm during the Sikh riots of November

1984 and which then found expression in the advertisement campaign of the

ruling party during the electioneering which systematically conjured up

violence and gragmontation of the nation.

Madhu Kishwar and Ruth Vanita made

a very perceptive analysis of this election campaign from tile angle of what

women have to expect from the ruling party and though they did not go into

the issue of .communalism in a very direct way, it became very clear in this

article to which extent the communalist tendency is linked up with the

37

patriarchal family syndrome and with the phenomenon of dynastic rule.

This is the kind of climate in which a secular family code cannot be

implemented because the communalist vibrations created in order to catch

the ’’Hindu vote” precisely make it necessary to assure the "minorities"

that their "rights” will not be touched.

In reality of course this means

assuring Muslim and Christian males that their superiority in the family

will not be touched.

Taking the issue up from a legal angle is good and necessary to the extent

that women's rights arc being claimed.

demand.

However, this remains a sectoral

To go into the wider question of religious reform as one of the

. . 14

14

means to build a secular national culture means taking up a general ques

tion (i. e. of secularism and a national culture) from a feminist perspective

and thus going beyond a sectoral approach.

a very dialectical way.

However, this has to bo done in

The strong attack on religion by rationalists and

by parts of the women’s movement is quite misleading since it pictures reli38

thus creating a bo gey which can be

gion as an arch-enemy of humankind,

beaten easily while the dimensions of class patriarchy and political self

interest remain entirely invisible.

This is a self-defeating strategy.

Huth Vanita rightly pointed out that the victims of the anti-Sikh riots

did not experience themselves as victims of religious fanaticism but were

39

She also cautioned

aware of a concerted campaign by politicians and police.

against imposing a Hindu majority kind of version of secularism “which is

what the government is doing anyway."

Madhu Kishwar has made a very moving contribution to the building of a

secular national culture recently by publishing her visit in Longowal vill-•

and an interview with Sant Longowal in which the spiritual quality of the

man and the place come across together with a very clear humanist content,

It

becomes clear in her writing that it was irreligious communal forces which

were fanning fanaticism and murder while the hunanist essence of Sikhism was

made accessible to the nation in the religious reform which the Sant stood

for.

It also becomes clear that this enlightened religious tolerance is

much less male-chauvinistic than the saber-rattling militance of the communalist fanatics.

I would like to quote this as an example of making access

ible the humanist content in a religion to non-believers and people of other

faiths.

It is important to acknowledge that in communalism, in religious reform and

in the women's movement a common question is raised but provided with diff

erent answers:

the question of cultural identity.

Communalism tackles the

question by creating a false consciousness with the suggestion that people

of the same religion automatically have the same socio-economic interest,

irrespective of class or patriarchy and that the way to implement this in

terest is to politically organise on the ground of religion.

Defence of a

religious personal law is crucial to this approach.

The women's movement tends to build on the assumption that there is a

certain commodity of interest between all women and that the barriers of

class, caste and community have to be overcome.

While overcoming class barr

iers entails clear political choices in favour of poor and exploited women ,

overcoming of caste and communal barriers is often attempted in a somewhat

voluntaristic way by simply declaring that they are artificial and thus

somehow unreal.

. . 15

:

15

Genuine religious reform deals with the matter in a more dialectical way by

acknowledging the social reality of caste and communal cleavages and identi

fying and contesting their religious sanctions.

An active effort is made to

A le- dor

overcome the meaning system which gives legitimacy to such cleavages.

like Dr. M.M. Thomas declares wherever he goes that Christians cannot be

communalists because they have to stand up for the new humanity in Christ and

arc thus responsible for safeguarding the humaneness of every human being.

He enables Christians to participate in secular political processes without

abandoning their faith dimension and he also makes the humanist essence of

his faith accessible to non-believers and people of other faiths and thus con40

tributes to a richer secular national culture.

His contention is that

rationalism and religious faith in certain ways need each other in order to

correct their mutual self-righteousness.

Since M.M. Thomas makes radical statements in religious language, he often

suffers the fate of not being heeded by religious congregations (because of

his political convictions) and by the secular political movement (because of

his faith dimension).

However, one docs need to ponder the point that ration

alism cannot always take its own rationality for granted (eg. the statement

that religion is the greatest divider of mankind is not a rational statement)

while a humanist faith can be quite rational within the parameters of the

aim to build a huaan society.

An approach similar to that of MM. Thomas is followed by Swamy Agnivesh who

was on the road in saffron robes instantly in protest against the Sikh riots.

He, like M.M. Thomas, openly theologises on his option for the poor and on his

political choices.

At the same time he makes it clear that political pro

cesses have to be free from the control of religious institutions.

His

saffron attire and religious language may alienate some people who are strict

rationalists or those who feel that Vedantha can only be seen as reactionary.

3n the other hand he reaches people with an emotional attachment to this par

ticular religious tradition and offers

them an identification with the poor,

with human rights issues and anti-communalist religious tolerance which would

otherwise remain beyond their horison.

Among Muslim Asgkar Ali Engineer has been untirngly recapturing the humanist

41

traditions within Islam.

He has paid a heavy price for his efforts even

physically, being exposed to the violence of the reactionary forces in a very

direct way.

His rc-intorpretation of jihad for liberation as opposed to

jihad for aggression opens up a social justice dimension suppressed by the

conservatives.

Faith to him means upholding the perspective of hope.

God’s

sovereignty is not seen in competition to human initiative but on the contrary,

as a source of setting it free.

While this kind of religious humanism is rare

and comes under pressure from institutionalised religion, it is ncvcrthlcss

an important ferment of cultural transformation.

Since such enlightened indi

viduals are open to the women's question, they may occasionally incorporate i

. . 16

16

M.M. Thomas in fact has develojosd a growing awareness of it over the years.

However, a feminist dimension of liberation theology has not yet evolved to

a substantial extent.

There is an additional reason why the women’s movement needs to go into the

cultural question more deeply:

The effort to give women a new sense of

identity beyond family, caste and religion needs to grapple with the pro

blem of cultural identity and continuity.

It is comparatively easy to

point out what has been oppressive and destructive of women in our cultural

heritage.- But the question what are the protest values and the humanist

values of our cultural traditions also needs to be answered if shallowness

is to be avoided.

To work out the materialist and rationalist heritage is

only one approach to this question which leaves the reservoir of humanism

within religion entirely untouched.

The need to touch upon this reservoir

also arises while facing the task to bring up children in a meaningful way.

Most activists confront the problem of having to relate to much more cons<r-|

vative and even very religious families in a constructive way.

Their chil

dren have to bridge the gap between a non-descript culture in their own

and something very different in the houses of their friends and relatives.

What docs one finally believe in?

Often women in the movement are frightened to touch upon religion because

they are frightened of communalist reactions and cleavages.

real problem*.

This is a very

However, making each others religious synbols accessible in

a secular spirit is a different matter which can become quite constructive.

Alliance of Anti-Communalist Forces

Since Secularism is rot a sectoral demand, the women's movement cannot fight

this struggle alone.

It has to ally with other forces which arc fighting

for the same objective.

4

However, the forces trying to build secularism in

the present situation are by no means homogenous.

In Kerala, the CPI-M has been able to champion the cause of a secular civil

code to a certain extent.

state

The fact that the party has a broad base in this

and that people's science movement has worked to build a scientific

consciousness, accounts for a more favourable situation as compared to mary

othcr states.

However, often enou^i electoral considerations &> weaken the

left parties in taking a clear anti-communalist stand as was obvious during

the national election campaign of 1964.

Englightcned intellectuals in different religious communities also play an

important role in creating an anti-communalist climate.

It is important

that the rationalist forces and the forces of religious reform which try to

creatively work out a progressive faith dimension, do rot become mutually

antagonistic.

17

17

Dalit and tribal moverrents which drastically attack caste and contest the domi

nation of the mainstream Hindu culture have an important contribution to make

towards a pluralistic secular culture.

At the same time they may not always

find it easy to come to terms with existing forces of religious reform -of main

stream Hinduism.

Eg. the reinterpretation of the terms arya and dasyu which

42

may not be acceptable to a Dalit perspective,

Swamy Agnivesh has to.offer

while his involvement with bonded labourers or his participation in Ekta-

morchas after the anti-Sikh riots are very important contributions towards the

building of a secular honanist culture.

The women’s movement may face its own difficulties to relate to all thesefores because it may disagree with the party analysis of class and patriarchy,

it may find the enlightened intellectuals to be paternalistic in dealing with

women, it may find the champions of tribal and dalit culture to be romantics

about women in palaeolithic times but not always helpful in day to day inter

action.

Finally, as women in the women's movement, we may realise that we

find it difficult to agree on issues of culture and religion.

There arc no

easy answers but indications arc.that the perspectives on secularism, reli

gious reform and a pluralistic humanist'culture are deepening within the

women's movement.

If the challenge ..is taken, women will be able to make the

most crucial contribution towards .building a truly humanist secular state.

NOTES

1.

Towards Equality: Report of the Committee on the Status of Women in ■

India (CSWl) (19 75, 4.236 7, p. 142).

2.

Eg. Indian Express, Madurai Edition, Nov. 17, p. 11. The Prime Minister

assured the Muslim community that their personal law will not be

touched.

3.

See Manushi No.25, 1984 and No.26, 1985.

4.

Vibhuti Patel, Sujata Gothaskar: "The Story of the Bombay Riots; In

the words of Muslim Women1' Manushi No. 29, July/August 1985, p.41-43.

Ammu Joseph, Jyoti Punwari, Charu Shahare, Kalpana Sharma; "Impact of

Ahmedabad Disturbances on Women" in; E.P.W., Oct. 12, 1985, Vol. XX

No. 41.

5.

Bipan Chandra; Communalism in Modern India (Vani Educational Books,

Vikas Publishing House 1984) pp. 86f. p. 131. Bipan Chandra insists on

Gandhi being a clearly anti-communalist religious reformer despite

his use'of Hindu imagery, eg. p. 156. See also p.167 "It has often

been noted that the purely religious or theological content of oommunalism has tended to be rather meagre. The communalist seldom relied on

Theology and, in fact, actively avoided theological issues",

op. cit. 167.

6.

Ibid. p. 160

7.

Yojana Vol.29, No.14 & 15 August 15, Special (Govt, of India Press,

New Delhi 1985)

8.

Saheli Newsletter Vol. 2, No.l, March 1985 p. 6ff.

. . 18

18

9.

Manushi No.27, March/April, 1985, p. 20.

10.

Bipan Chandra op. cit. 292.

11.

See eg. Sankar Gose; Political Ideas and Movements in India (Allied

Publishers 1975) Chapter II Extremism and Militant Nationalism,

especially his characterisation of Aurotindo‘s social outlook during

his period of religious nationalism p.52.

12.

E.P.W. Vol.XX No.40 Oct. 5, 1985 pp. 1691-1702 and Vol. XX no. 71,

October 12, 1985, 1753-1758.

13.

Quoted op. cit. p. 1691 (from Navajivan June 28, 1925).

14.

See detailed examples in my own article : “Personal is Political:

Women and political process in India" in; Teaching politics Vol.X Annual

No. 1985 pp. 45-70.

15.

E.E.W. Vol. XX No. 40, p. 1692.

16.

E.P.W. Vol.XX No.41 p. 1757

17.

On this aspect see my article mentioned in note 13.

18.

For a comprehensive critique of the body-soul dichotomy in Gandhi and

its political implication see M.M. Thomas: Towards a redefinition of

Gandhism (1953) in: Ideological 4uest within Christian Commitment

1939 - 1954 (CLS, Madras 1983) pp. 236-252.

19.

For the following see Gail Omvedt: Cultural Revolt in a Colonial

Society. The non-Brahman Movement in Western India. 1873 to 1930

(Scientific Socialist Education Trust 1976), especially chapter 6.

20.

Ibid. p. 108

21.

Ibid. p. Ill

22.

On women’s position in the Dravidian Movement see my article mentioned

above (note 13).

23.

The Record of proceedings was published July 1967 by Bharatia Vidya

Bhavan. The Committee of the Colloquiun comprised the President of

India, Dr. Sarvepally Radhakrishnana, the Vice-President Dr. Zakir

Hussain and many leading lights of Indian political and cultural life.

24.

Joachim Alva op. cit. p. 419.

25.

Motilal Banasidass 1st Edition 1938, reprinted 1962 and 1973.

26.

Ananynous Author, Colloquium report (note 22) p. 421 f.

27.

University of Madras 1976

28.

Ibid. p. 23f.

29.

Ibid. p. 19

30.

See eg. Malik Ram Baveja: Woman in Islam The Institute of Indo

Middle East Cultural Studies Agapura, Hyderabad, ho jear.

31.

In memory of Her. A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian

Origins (SON Press 1983)

'

. . 19

19

32.

On this question of having to make choices between contradictory state

ments according to the criteria of broader humanitarian values see my

paper “Perspectives of a Feminist Theology: Towards a Full Hunanhood

of Women and Men1' in; Woman's Image Making and Shaping ed. by Peter

Fernando & Frances Yasas (Ishvani Kendra, Pune 1985, pp. 123 - 148)

33.

Nov. 17, 1985 Express Magazine p. 5

34.

See eg. the anthropological study of Susan S« Madley (ed.) The Power of

Tamil Women (Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs Syracuse U

University 1980). This study remains very much at the surface of present