RF_WH_11_13_PART_1_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

w

J

RF_WH_11_13_PART_1_SUDHA

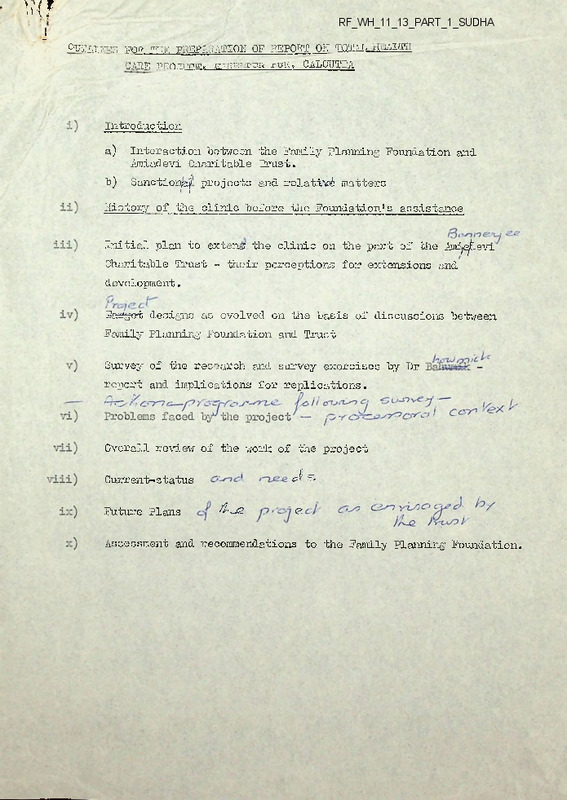

°WTJ>.y, FO R. THE PREPARATION OF REPORT ON TQT.tT, Ha^IZHX

’CARE PRO-Trnc, jtc fr^Trppzt run, CAIiCTJTTA

introduction

a)

b)

Interaction between the Family Planning Foundation and

Amiadevi Charitable Trust.

Sanctiorjaj? projects and relative matters

history of the clinic before tile Foundation's assistance

Initial plan to extent: the clinic on the part of the Ami^levi

Charitable Trust - their perceptions for extensions and

development.

Target designs as evolved on the basis of discussions between

Family Planning Foundation and Trust

Survey of the research and survey exercises by Dr

report and implications for replications.

Overall review of the work of the project

d S

Current-status

Future Plans

^-<2

p

Assessment and recommendations to ■the Family Planning Foundation.

«/

/?6 6.

3

’h

^CO ) t'L'- '’.J „ ^—'^O Z-cJ ^~>c>

/llCAhCr

/^

' (^

77-^e.

ihc'CC

/(frCXT,

ex

T^izLi'tA.o

T><^

*

t5/

Cl^r,

(Z/

<=:uoc-( o>^-e^ h^<c

<zxhcn.il

C i.&^/'e h c</

/O nh. L(^,o

C’l

AC^~!

c~<-^-)

/be^<9

Ccr>T^Z> c<./k^>a

zZX-x~>c-£

ezfK-e&he-cA

^<z

/A_^>

h c^~>/O//'c. /

/A.&

ct,c.^-,i_J=3^->

/?>■€- -/^jecf'

0

FAMILY

’LANNING

TOTAL HEALTH CARE PROJECT,

FOUNDATION

CALCUTTA

Assessment Report and Suggested Action

Observation:^

This report pertains to assessment of the progress of the

programme with regard co completion of baseline survey, preparation

of operational design, working out requirements of the programme,

defining concept of Total Health Care, determining various components

of the health package and identifying target groups for them, and the

progress made with regard to implementation of recommendations made

earlier (refer previous note by the Foundation staff).

This report also

contains suggestions and recommendations for future action.

2,

The baseline survey in the project area was to be carried out

in two rounds.

The first round has been completed for all the 13 project

villages; four villages have also been covered under the second round of

die survey.

Data collected under the survey has a variety of inform

ation which can be used for programme planning, implementation and

measurements.

What is needed is to glean from thia relevant inform

ation which can be of immediate use to the programme.

3.

A preliminary report, based on the sur”ey data, has been

prepared.

It is a fair description of the social situation as it prevails

in the area.

However, it would have to include more details to be able

to provide effective indications for programme planning and development.

This information has not been given in the preliminary report and perhaps

because of this the operational design could not be formulated.

As the

things stand at. present, it would take another two months time (end of

February 1975) to complete tire survey and a few more months to

finalise the report and recommendations.

If the implementation of

action programme haa to wait for completion of the survey report, it

can not be launched before the month of May 1975.

4.

The project has been sanctioned for a period of three years, of

which a little more titan one year has already passed.

If the action

programme is to be initiated from the month of May 1975, it would hardly

leave 18 months time to assess its impact and formulate recommendations.

No action research programme, more so in the field of health and family

planning, can t-.ow impact on the behavioural practices of the people in

such a short time.

The primary need, therefore, is to launch ths

action programme as early as possible.

This can ba done in the four

villages where second round of the survey has been completed.

This

can be treated as a pilot experiment which would help in getting necessary

experience for extending the project activities in other villages when the

baseline survey is also completed there.

The second round of the

survey should be continued simultaneously with ths action programme.

The flexibility of approach, however, needs to be maintained so that the

methodology of programme operations could be changed, modified or

adjusted according to the needs of the programme from time to time.

2.

Recommendations and Suggostions_

P. a commendations pertaining to Research Components^

5.

a

The first step would be to define the concept of Total Health Care

as applicable under the project.

Efforts should be made to

formulate a package of programme which could be reached to

the maximum number of people.

Only those programmes should

be included which could regularly and easily be provided to people

for the G—.ire tenure of the project.

b The family should be i->ken as a unit for providing necessary services^

Since it is a total health care project.

This would help to reduce

the mobility and duplication of visits by the workers which may

otherwise be if action staff tries to tackle various target groups

individually for different components of the programme.

It is

recommended that such target groups should be indicated within

the family record/addition to listing them in a register.

/in

c

The data for the four villages where second round of the survey has

been completed should be compiled and tabulated on priority basis

for extracting essential information to prepare a programme plan.

The following types of information would be necessary

i)

ji->ist of pregnant women (those in the last trimester of

pregnancy may be taken as high priority group).

ii)

iuist of children upto five years of age (infants may be

taken as high priority group).

iii)

x.ist of children under five years of age who had had their

primary vaccination, those who also had secondary vacci

nation and those who never underwent any type of vaccination

(the lust mentioned may form tits high priority group).

iv)

List of couples with wife's age ranging from 15 to 44 years.

v)

^iat of couples with three or more children and those with

less than three children; list of women with youngest child

upto five years of age; list of pregnant women (Ute women

with youngest child upto five years of age should be taken as

high priority group.

Pregnant women should be assigned

second priority).

vi)

Cist of couples where either of the spouses had been

practising one or the other method of contraception.

vii)

iuist of common diseases prevalent in the area as reported

by people and also list of diseases for which people generally

come to the hospital.

The first type of information can be

compiled from the survey data.

For the second type of

information analysis of a 5% sample of hospital records is

recommended.

viii)

Peoples' conception about causation, prevention and treatment

of common disease in the area; what diseases are considered

to be of serious nature and the stage at which they are usually

reported at tho hospital; analysis and comparison of this

information with the diseases recorded at the hospital

(Dr ? X Bhowmick should visit the project villages and

carry out depth interviews with the village people).

ix)

Sources and type of medical care generally resorted to by

the village people.

x)

Total number of births and deaths in the villages and illness

in the family during the past 12 months (this information can

be compiled from the survey data).

xi)

A general report about the environmental sanitation and

hygeine (Dr Bhowmick may visit villages and conduct

depth interviews and observations on the topic).

xii)

Village wise list of community leaders.

xiii)

List of available medical and health facilities from the

Government's side.

xiv)

A general report about economic, educational and

occupational structure of the community.

d It would be possible to take out above information from the survey

records..

For additional information, Dr Bhowmick should visit

the project villages along with other investigators.

The patient

records at the Amiya Debi Hospital should also be analysed to

compile information on the type of diseases for which people come

to the hospital, stage of the disease at which institutionalised

medical care is sought, distance from which the patients come,

general educational and income level of the patients, and their

sex and age composition.

The above information would be useful

for planning the programme, for working out the quantum of

services that the different target groups would need and also for

developing suitable programmes for educating the people.

e Evaluation:

Evaluation is defined as a method of judging whether a particular

programme is moving in the right direction according to the

envisaged goals and to find the causative factors in case its not

being upto the expectations.

This makes it imperative, that

before embarking upon any action research programme, its goals

and objectives are clearly and specifically defined in terms of

"what is proposed to be done' and "how it is proposed to be done".

The success of such programmes mainly depends upon a built-in

system of evaluation to assess the impact of the programme as a

result of efforts and performances by the workers.

Programme

evaluations are carried out at two stages, that is toe "impact

evaluation" and "performance and effort evaluation".

The

impact evaluation is directly related to the ultimate objective of

the programme.

On the other hand, the evaluation of the

performance and efforts goes on concurrently with toe programme

with the sole aim of improving its operations and is based on

analysis of the reports and records of the workers, field observa

tions of the programme and the staff meetings.

The main aim

5.

of health and family planning.

The research support, presently

available to the programme, has been appropriate and useful to

the existing needs, that is, completing the baseline survey related

to social or behavioural aspects and preparing the report.

The

time has come to identify and engage expertise of an action oriented

kind in health and/or development.

Efforts may be made to

locate consultants, if possible with requisite experience in Calcutta

itself.

The consultants should be associated from the beginning of

the action programme and should be continued for the rest of die

tenure of the project.

Their specific functions would include

development of project design, preparation of operational programme

plan, development of indices for measurement, evaluation plan,

development of instruments for documentation, suggestions for

development of suitable educational material, description of roles

and functions of different functionaries of th© project, the type of

help needed from ofccr government functionaries, suggestions for

training of project workers and provide necessary help in

periodical evaluation of die project work.

6.

Recommendations pertaining to toe .Action Programme

a Determining a Package of Health Services

The final package of health services would be based on the needs

of the people, as emerging out the survey and on toe basis of toe

data collected from hospital records.

tentatively, thefoliowing

services can be included as partof total health care to be provided

to people.

i)

Maternal and Child Me alm Gare Services:

These services should include immunisation of pregnant women,

ante-natal, natal and post natal care, and nutritional supple

ment where clinically indicated.

ii)

Immunisation and "vaccination:

This should include ail children under frive years of age, to

be covered under primary vaccination, intensive immunisa

tion drives during epidemics and secondary vaccination of

those children who come to hospital.

iii)

General Medical Care:

This should include in-patient and out patient medical care.

iv)

Family Planning:

This should include male and female sterilisation and

termination of pregnancy at toe hospital, and distribution

of condoms at toe community level.

v)

Me alto Education :

This should be based on individual group and mass education

through various media and methods, and should form part of

each of the health component of toe programme.

b Operational Steps

The subsequent step would be to draw out a plan of action consisting

of various operational steps and their sub-steps.

In this connection

the foilowing are recommended

c

i)

Identification of various target and priority groups for each

individual component of the programme.

ii)

Based on the needs of various target groups as emerging

out of the survey data, the minimum package of services

should be defined.

iii)

Determine suitable methods for providing the services.

iv)

Determine a suitable staff structure on the basis of the needs

and requirements of the people and the methods for delivering

the services.

v)

Arrange for training of the research and action staff.

vi)

Describe various steps in starting the programme and a

time schedule for it.

vii)

Decide about a system of coordinating the activities of

research and action staff.

viii)

Lay down procedures for recording and reporting, decide

about evaluation mechanism, develop instruments for

documentation.

ix)

Identify educational needs of the people and make efforts to

collect/develop educational material accordingly.

a)

identify and try to mobilise human, physical and organisa

tional resources for the programme.

xi)

v/ork out a realistic time schedule for entire tenure of the

project including that of the pilot experiment in four villages.

xii)

Prepare a physical map of the entire project area, showing

situation of all the project villages, Amlya .Debi Hospital,

important landmarks, place of posting of the Government

functionaries, educational institutions, available medical

and health facilities (both modern and indigenous), and

approaches to different project villages from the project head

quarters.

This would help in planning die programme for

different villages, development of staff and chalking out

their movement schedule.

Method of working

The action programme is to be launched within a period of two

m<>r. months.

Efforts should, therefore, be made at this stage to

define and describe the methods of working and approaches to be

adopted for the programme.

These would include determining

a package of health services, systems for delivering the services,

mobilising necessary resources, describing roles and functions of

the staff, defining the role of Amiya Debi Hospital etc.

7.

i)

Package of Health Programmes:

As has been discussed earlier, efforts should be made to

include only those services in die package whose continuity

sufficiency, regularity and easy accessibility to people could

be ensured for the entire tenure of the programme.

As

such, the programme would centre around maternal and

child health care, immunisation, family planning, general

medical care and health education.

Presently, some of

these services are being provided at the Amiya Debi

Hospital.

However, a system should be evolved out for

domiciliary care.

ii)

Method of delivering die services:

The subsequent step should be to evolve methods of delivering

these services.

Thf.t would include education for creating a

demand for the services and developing a system for their

delivery.

A part of these services, as has been mentioned

earlier, would be provided at die hospital whereas others

would be provided at the door-steps of the people.

Services

for male and female sterilisation, termination of pregnancy

and general medical care would be provided at the hospital.

On the other hand maternal and child care, distribution of

condoms and immunisation services would form part of

domiciliary care.

The system thus evolved out would

have to be based on a mix of hospital based as well as home

delivery services.

d Mobilising Resources for die Programme

Human Resources

The success of the programme would be contingent on efficiently

and regularly reaching the needed services to people.

Although

die project would be engaging a number of workers, there would

also be a number of Government functionaries in the area and

unless efforts are mads to coordinate work of the project staff

with them, there would be confusion and overlapping.

Besides,

the services of the Government staff can also be utilised for the

programme.

For instance, the school teachers can be made to

participate in educating people and act as community leaders.

Similarly, the resources of the teaith workers like vaccines for

immunisation and condoms for family planning can also be

procured for the project.

They can also be mobilised during

the intensive campaigns like mass sterilisation programmes and

mass immunisation during epidemics.

It would be advisable to

identify these resources and make efforts to use them for the

programme.

Organisational Resources

The health and agricultural extension departments usually produce

educational material for free dostribution.

The project organisers

by maintaining a liaison with them, can, as and when necessary

and possible, procure these inputs.

Likewise, the Government

functionaries can also help project staff in establishing rapport

with the people and mobilising support of the community leadership.

8,

A cautious approach is recommended, ho waver, while trying

to seek support of the Government functionaries.

The efforts

should be to maintain effective liaison or a sort of working relation

ship with them.

If necessary, senior officers of the concerned

departments may be approached informally to seek their sanction.

At no stage the Government staff should be made part of die project

by assuming their technical or administrative control.

Their co

operation would be necessary only to avoid confusion and duplication

of efforts, avoid overlapping in the area of operation and to procure

necessary inputs for the programme which may be difficult to

obtain in open market.

e

Supervision

Documentation, evaluation and supervision are closely interlinked.

Documentation provides clues for evaluation and, in its turn,

evaluation provides necessary information for supervision.

Together these three contribute to improvements and thus lay

foundation for success of The programme.

Supervision helps in developing staff capabilities for better

performance.

For the project work, it should include both

field supervision as well as headquarters or hospital based

supervision.

Again this can be both technical and administrative.

The technical supervision should be the direct responsibility of the

Assistant Project Director (senior social scientist) who would

operate under the guidance of the project director.

His

responsibilities would include both supervision of action programme

as well as research.

Specifically this would include field guidance,

help in accurate documentation,assistance in solving work problems

of the staff, help in establishing rapport with the leadership etc.

The supervisory responsibilities of the project director would

include providing technical guidance in matters related to health,

solving administrative problems and periodically taking suitable

decisions for smooth running and successful completion of the

programme.

It is recommended that the mechanisms for

supervision and the supervisory responsibilities at different

levels should be described in specific terms before taking the

programme to field.

f

Education

Education of the people for motivating them to avail the services

provided by the project, to inculcate healthy habits and to provide

correct information on different aspects of the programme would

be an important component.

Health education would form part of

each of the individual programmes like family planning, immunisa

tion etc.

The first step in planning educational programmes would be to

identify needs of the people in terms of their attitudes, levels of

knowledge and awareness, the linguistic contents and the methode

and media to be adopted.

This information should come out of

the baseline survey.

The subsequent step would be to identify

the sources from where needed educational material could be

collected.

In case necessary material is not available or is

not suited to the tastes of the people, efforts should be made to

develop it within the project.

c).

Presently, there are a few agencies like Red Cross, the Health

Education Bureau, the Family Planning Department, the All

India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health and a few other

voluntary organisations from where such material could be

collected.

This is, however, likely to be a routine type of

educational material created for wider use.

The project staff,

therefore, would have to develop and produce suitable literature

and aids with the help of the available technical expertise in

Calcutta,

Two types of educational material would be needed.

Firstly,

die project would need some aids and literature for individual or

group education which can be used by the field workers.

The

second type would be for mass education and would be used with

hospital as the centre with the objective of creating general aware

ness.

Specific knowledge should be given through individual or

group communication programmes where ths audience can be

selected specifically for the purpose and where die mode of

communication would mainly be interactional.

7.

Recommendations pertaining to staff structure

Effective and efficient delivery of services would be basically

contingent on suitable deployment of trained staff.

The project staff,

based on the requirements of the programme, would consist of three

types of functionaries, that is, the hospital staff, the field or action

staff and the research staff.

The needed strength of the hospital staff

can be assessed only by the organisers of the programme according to

the in-patient and out-patient load on the clinic.

Here a staff structure

is recommended only for the action and research parts of the programs

a Action or Field Staff:

Total population to be covered under this project has been estimated

to be around 21,000.

According to the latest thinking on toe

subject, there should be at least one Auxiliary Nurse Midwife

(ANM) *

1 per 5000 population to take care of the maternal and

child health care, family planning and health education services.

In addition, the project would also need at least two male workers *

2

(equivalent to health assistants) for immunisation services,

distribution of contraceptives (mainly condoms) and health

education services.

Thia would give an average of three workers

per 10,000 population (one male and two females).

Taking toe

birth rate to be around 350/00 in the project area (national

average), there would be nearly 175 births in 5000 population

in a year giving an average of nearly 15 births per month. This

would also mean that there would be around 273 *

3 pregnant

women in a year within toe operational area of an ANM.

This

should be the endeavour of project workers to roach MCH and

immunisation services to ail new born children and pregnant

women and, thereby, make this programme a foundation for

boosting family planning acceptance.

*1 and *

2

The main aim is to treat these functionaries as male and

female multi purpose workers. As such the functions of ANMs

and health assistants would essentially be like that of their counter

parts under the proposed governmental pattern.

The old nomencla

ture, however, is retained till suitable designations are decided.

*3

The number of pregnant women in a given area is generally

calculated at one andhalf times of the number of births in a year

within a given area.

10

The project would also need a Health Education Officer.

His

responsibilities would include developing and organising

educational programmes and providing needed technical guidance

to field workers.

b Research Staff:

The primary objectives of this project are twofold.

Firstly, to

find out whether integration of family planning with maternal and

child health care can augment its acceptance by the people.

Secondly, to develop a methodology for delivering a package of

health programmes with a voluntary clinic as nucleus for

providing these services.

The ultimate aim being the replication

of such programmes in other areas, based on the methodology

evolved under Shis project.

The success of the programme would depend upon experimenting

with different delivery systems, assessing their impact,

establishing a correlation between maternal and child health care

and family planning acceptance, developing a programme for

training of workers, collecting essential information for developing

educational material, conducting special studies related to

different aspects of the programme, evaluation of theprogramme

progress both at the terminal and concurrent levels etc.

As

such, the project would have to have suitably competent and

experienced research staff.

Considering the available resources

with the project and the needs of die programme, it is recommended

that there should be at least one senior social scientist designated

as Assistant Project Director and one statistician.

The former,

in addition to his responsibilities described earlier, can also help

in organising the action programme, prepare education material,

write reports pertaining to the project work, supervise the

workers and assist in evaluation of the programme progress.

In fact his supervisory functions would include both supervision

of action programme as well as research work including report

writing.

The statistician, on the other hand, can help in

compiling and tabulating research data, scrutinise field reports

under the supervision of the social scientist and provide all the

necessary statistical support to die programme.

c

Qtaff Structure

The overall staff structure of the project would be somewhat like

the following:

Research Consultant

•

Project Committee

-Project Director

Assistant project Director

{(senior social scientist)

{

Statistician

J

Health Education

4 ANMs

Officer

2 Male workers

!

Hospital Staff

11.

d Role of the existing Research Staff

It is recommended that the question of retaining the existing

research staff for their employment as field or action workers

may also be considered at thia stage. On the positive side, some

of them may be having the requisite competence and their retention

in the project would help in saving time, energy and money which

may be needed for training and orientation of the new workers.

By now, they must have developed understanding of the basic aims

of the project, and should also have developed a working relation

ship with the leadership of the area, besides having complete

knowledge about the area and people of the project villages.

Before taking a decision, however, the needed expertise for the

project work, like training in Health Education Maternal and

Child Care, techniques of vaccination and statistical experience

be considered.

The existing staff would be useful for action

programme only when they have undergone tire necessary training

for these activities.

Therefore, implications of this in terms

of finances and time be assessed before taking a final decision.

Budget Implications:

8.

The following is the likely item-wise break-up of the project

budget:

a Recurring:

i)

ii)

iii)

iv)

v)

b

Staff Salary *1

(see footnotes on page 12)

9,600

plus 4 ANMs @ R?. 200 each

300 x 12

6,000

" 2 male workers @ R? 250 each

500 x 12

9,000

" Asstt. Project Director

750 x 12

(senior social scientist)

4, 800

" Statistician @ R 400

400 x 12

4,800

" Health Education Officer @ R-400 400 x 12

" Stenographsr/Acctt. Asstt./

4, 800

Clerks @ FO 400

400 x 12

2,400

" Driver @ R? 200 x 12

1,200

" Messenger @ R? 100 x 12

12,000

" Hospital Staff © R> 1,000 x 12

(including honoraria for doctors

and petrol expenseon their transportation)

54,600

Travel expenses (travel by project staff,

including expenses on movement of vehicle

5,000

on their travel)

1,000

Stationery, postage, printing etc.

2,400

Maintenance of vehicle (repairs)

4, 000

Misc. (including purchase of education

67,000 per year

material)

Total

Non- recurring: *

2

i)

ii)

iii)

iv)

v)

8,000

500

10,000

2,500

Coat of Vacurette

4 ANM kit boxes

Educational equipment

Bicycles for field workers

Annual expenses on medicines *

3

© K 10,000 x 3

Total

30,000

51,000

12.

c

The grant sanctioned by the Foundation is Rr. 1, 50,000 for three

years or R*. 50,000 par year.

As would be seen, the annual

recurring expenses on the project come to R

*. 67.000 leaving a

balance of R5.17,000 per year.

In addition, non-recurring

expenses would also come to nearly R. 51,000 if we also count

expenses on medicines as part of it.

Thus, the total amount

of money to be managed from other national or international

agencies for the remaining period of two years would come to

R». 85,000.

d The organisers of the project should work realistic requirements

of the project and approach OXFAM for the same.

The

Foundation, in its turn, should also make efforts to interact

with OXFAM to help the project.

In this connection, it would

be advisable to approach the regional officer of the OXFAM to

visit the project and discuss the requirements.

Considering

the fact that some of the inputs would be needed even to initiate

die programme, efforts should be made to have this meeting at

the earliest possible opportuni ;y.

*1

The suggestions with regard to scales of different functionaries

are only indicative of approximate expenses.

The salaries

would finally be determined on the pattern of the salaries and

scales as prevalent in West Bengal.

*2

Non-recurring expenses as given in this report are only

tentative suggestions.

Actual expenses would depend on

the market prices.

*3

The Family Planning Foundation does not provide budget for

purchase of medicines, equipment etc.

TOTAL HEALTH PROJECT - BUDGET

a) Banerjee Charitable Trust

b) Family Planning Foundation

Total

Promised

Already Paid

To Be Paid

RS.

R?.

RS.

50,000

1,50,000

2, 00,000

30,000

75,000

1,05,000

20,000

75,000

95,000

Money already spent a) On Research

R§. 50,000

b) On Hospital work R'. 36,000

86,000

Money at Hand

19,000

Promised money yet to be paid

95,000

Total available fund for Budget

(for next if years)

1,14,000

Expected Expenses in Hospital As per present activity

Proposed increase of

M.T.P. (with instal

lation of Vacurette)

R5. 36,000

R*. 12, 000

Money avaliable for Action Programme :

48,000

66,000

Expenses required for Action

Programme

Items to be taken up :

A PROPHYLACTIC

1. Small Pox vaccination

2. Triple Antigen inoculation

3. T.A.B.C. injections

4. Multi-vitamins/Calcium for babies

s cuRfVrrw medicines

1.

a.

b.

c.

Against Gastro Enteritis - 30%

Antiamoebic

Antidysenteric

Antihelmantic

2,

B CURETIVE MEDICINES (Contd. )

2,

a.

b.

Anti Infective drugs - 20%

Sulpha group

Broad Spectra group

3.

Secondary to malnutrition - 40%

Supplementary vitamins/nutrition

4.

possible

Skin conditions and others - 10%

At present we are not taking up adult health education due to lack of capital

for aduio-visual set up and no certainty for future recurrent expenses. (We

have purchased an old Jeep for transport of doctors, but we are still using

our personal car as the Project cannot afford a driver or petrol for the same).

C

The family planning operations, including tubectomy and medical termination

of pregnancy, are being carried out and will continue in the Amiya Debi Hospital

as before, but with Vacurette the M.T.P. work will increase.

Though a concrete plan is not possible without a knowledge of financial resources

and rising price index, the minimum requirements are given below.

In formulating a provisional Budget our aim would be a.

To protect the families where the mothers have been ligated, particularly

babies.

b.

To give incentive to our Project population for family planning operations.

c.

To allow some coverage to fringe areas outside the Project zone on

humanitarian grounds.

The action programme plan is based on our knowledge of research already

carried in the first schedule and analysis of hospital attendance over the years.

We have taken for the purpose of calculation an average daily attendance of

100 in our out-patients department and average distribution of cases. This

is in addition to the expenses for operations and indoor patient care being

carried out in the Amiya Debi Charitable Hospital and which will continue.

Expected Expenses of Action Programme

(very provisional)

A.

1.

PERSONNEL

-

RL 26,100

Social Workers R5. 15,300

We shall require at least 3 Social Workers who would carry out house visits

including inoculations and medicine distribution. They will be recruited from

the field workers who have already carried out dosr-to-door data collection

and are conversant with local conditions. They are known to the local

populace and the latter will feel more at ease in dealing with them. We intend

to employ 3 of the female field workers whose services would be terminated

otherwise, now that data collection for research is over. Though we have

allowed them free accommodation in our residential house next to the hospital,

their salary would be R5. 850 per month. So for 1| years: R5. 850 x 18 - RL 15,300.

3,

A.

PERSONNEL (Contd. )

2.

Record-keeper cum Typist

Rd 300 per month

-

R?. 5,400

3,

Driver for jeep @ R456. 300

per month

-

R5. 5,400

B.

METHODOLOGY

1.

Small Pox - door-to-door visit for all

2.

Inoculations - part by home visit and part hospital based.

3.

Distribution of medicines

-

Rd 3,600

- mostly hospital based.

So some Peripheral working and use of the Jeep will need rough estimate for

conveyance @ R5. 200 per month

R?. 3,600.

C.

COST OF MATERIALS

If the Action programme is to be properly completed and, more important,

evaluated in accordance with the Family Planning Foundation's guidelines,

it is estimated that the following items of medicines with their quantities

will be required. Against each item the cost has been worked out on the

basis of wholesale prices quoted by pharmaceutical companies. It will be

noticed that on this basis the total cost of medicines for the remaining if

years works out to nearly Rd 9 lakhs. This is obviously impracticable.

What we intend to do is to tailor the work in this field to the quantities of

medicines that we can procure with donations from international and other

organisations. Needless to say, any part of this that can be supplemented

by cash donations will be welcome.

Materials

- will be available from State Govt, sources

1.

Small Pox vaccine

2.

Triple Antigen inoculation - 5% of 20,000 - 1000 children

@ 3 ampoules - 30,000 ampoules (from 2 to 5 years old

children)

Cost Nil

45,000

T.A.B.C. injections - 2000 10c.c. phials @ 6 monthly

injections - 3 x 2000 - 6000 phials (for whole population)

12,600

4. Multivitamin tablets - for 1000 babies one daily - roughly

3,50,000 tablets

63,000

3.

5. Calcium tablets

-

35,000

- do -

6. Against Gastro Enteritis - 30 patients daily - roughly

400 days - so total is 12,000 patients in if years

a. Antiamoebic tablets @ 10 tablets of Enteroqiunol per

patient - 1,20,000

b. Antidysenteric tablets @ 10 tablets of Thalazol per

patient - 1,20,000

c. Antihelmenthic - Decaris 1 tablet/patient - 12,000

12,000

adults

15,600

45,000

Anti-infective drugs - 20 patients per day @ 400 days in

1| years - total number of patients 8,000

25, 200

a. Sulphanilamide @ 2 tablets twice daily for 5 days, i. e.

20 tablets, therefore for 50 patients - 4000 x 20 - 80,000 tablets

10,400

b. Terramycin

- do - 4000 x 20 - 80,000 capsules 54,000

8.

Secondary to Anaemia

(and malnutrition)

April 23, 1975,

40 patients per day @ 400 days in 1| years

Total number of patients 16,000

@ 1 tablet daily for 1 month 16,000x30 - 4,80,000

Fero-redoxin or the like

8, 89, 600

3

a... 2

2

8

caotodarnblo usd i .too.

s..to

eo.tsisttot;

to '.a: . .atoll :

' la's:’, It ;;ec caas.toostol a suitable ylaco ilzn: .-a

to.. ta -• a to-

too.o stootoo.

J.

ObjopMvafi

:.a.to. toto stovs. u?,s a; ioa atosto tout it was joaatolo to havo cn

.'

a.a oto‘. ■ a aaaaaa i ..a <a -.to' to? J.ly totos.to.o-,

aa. a... to .. .so

.

to...-a : ?ao 000.00 .coos-., af a aa.vaa: aa.Jaa aa,; --.0.000 00 aaaday asa..

. a.j. ■ ato a \a of" .asa

■ a;.

*to

to,;.to

..

.1 oa?a.. to s..to? of tooto,-;:.:.totoi

co..: ccatoftotos of jototolv-s ;. .J. ;,;a v.'avsivo stoical rjuiL hoalfZi er.XG, .

'".a stoato. a?

a.: a-'-a ■ aoy.

, a'. ;ja!?a. acaa.ai :a

. to o to.;-.., ..-toss

a .

-a,-, a.....

a.

,a;atoa'!. as.'. a.aaSf, ,.a:

.'aads.'-J. o.o as ;;-a a of zabj. aatod

. . . . c.a.. a:x as y Ivtiiiioiaf ..slT ;0.. as.-aizf.

defcoaojo-y

a a as. la

v....; •. jJ.,: a’ ■LO-.:.;-.a; oarisoo.

a:-,'.'; ;... 70.00 to _i' ,l

0 '

.. ..too . Io ;.toa.to;;y .aicjri-toas

aa.:-:-,) '.so ~ -■. souvoy of

a . ..jiC-O.S.SOOJaO?..'.;; aad.J.a.a XOf tUO

soal'to os', xto-ily toaoitoj jiaeilu mto

r. iso i . a;.:l atoao.'toioatoos os totoa:;toa-.:toad 3t;.<.oaLj disto oadl ha

'too ' aa/,;-^as a a too as a a uiai to? as ajojoot:.

ctovolop q naojcot; d-atoai basal oii t'o? a'i ato..

.'ov.2.a_:i/o ■ toaoos-ffl-srcitioji project,

iG' to3.

*'O.,

isinoc toss -

of toe tojnae q ;:j fox

totase adc- _ .-to.ivo <tooo a-todto:.

JC o*

of

a --xo-jocs

tola oxojco-e 'jo;; co-ioidarcxl iioxj.xto. si '.ox‘ oj’roxs.'l s..’oeo.;o.\so (1) to.ilo

u. ; :sto:. of is.'to as -.too Siodiii usxo xsa:'; aocayttol to bhco.ey, toicxo veo do

soot pxtaiticol a s; to.ia> fox- aiux-a’.so-.i of aotofsl isiiiJlcs^nto-idon.

s.iis

saxtiotolcifly toaci io too case af voXusttoto o-jjanliJaticuio '.la.icli ac-edotl in tos;

Coa.-td.».5

5

>

8

Hie project, therefore, had special

th:.t would suit; th-mi.

up th.- ido?. in •.

value for this

(ii)

the project would help to identify ways and means

of ,;. Ivsocial norvice mimed citisons with or without medical oxyartiso to

ho i_./olvjd in t’:

*

..ro^rnoae

ihe project if iisnonstratod well would have ropli~

oum pre ;r :.. .....:•

Ceti;.:, v ;luo for the

^pomtfon-liantl&n of the ■■iclrrao;

who -chow, . ;ot up to s - cod sturt.

.;'.. the- project

>< f.j i.

tJav.-.wnor of •■? .t

Eie ‘hnasetiGnt Cow.iittoe of the project

also launched by no loss ..-, parson than the

- Jr fir-s.

2i.i h»di:l had from the v.'wy ■.>;■

n:..;.-.’. .1 ..'...• ^

tho

u stro-rj bias in favour of

’..j.j./ ah,o utrokply imbum-1

t.’ti lawn of oervi-rj t?:o people,

■; of i .o well-to-do : JLplty th.;- xio-sdy and/or helpless.

mity’

; £•.'j . ;.-J os . . Ii.. owl-jzitation for hsultu services whore people’s i nvolvement

r . '..- ,...’ alien to some of the hey iniividr/ls.

rz.tt

;• tyl)

o :s.;y

nr.pwcol

providers of charity.

it also scored to

Oriontation of the key pooplo to

■ s:e med ...nd relevance of tb.c- uo. munity hoziluh approach continues to

bo ;j real cli:.ll.;.n.:o to the foundation,

' ho positive support of i-w Irani and one

or two •..i~..ioow3 ol tie Committee has boon r; helpful one in continuing tho project.

I’oun .;tio.•’. .'jtaff, ti.orafoi-e, had to nuh. a few visits to Calcutta and help

t;. j ,Pi-..-..'etsrs t..- conceptualize as having innovative possibilities,

.dco it i?as

dcoidwl Is rc;nii;;itic»i the services of a I'rofessor of Social Anthrojolosy in

conructin;., xhe initial survey for deaipni. . the project.

Hio normal work of tho

boa.it.-l. widi ucoent on sterilization continued for most of t-c- time, except

i\:w L..;c period ci‘ f.;o cmae.'£psncy uho»i ate work slowed down conaidorably.

Arininiatratian & Ptaanam

2ie Covarninp -hoard at its rnjotinp hold on 12th i^ptoubor, 1972 sanctioned

Contd....4

s

a grm:.t ox

4

t

Out of this a sun of ks 1,20,000

1,50,000 for ■ t -is project.

has alreray boon disbursed.

"•ator in ,;\v<rast 1374» tie Governing Board sanctioned ts sun of Bs 36,000

to cover ■■•.■:, .■ . ....;e;.-. ozi soHoasch consultancy.

-hie mount has not boon

utilised ::o far.

xollcia u~; '■-. - 7i.i.uro hetioa

.h.ic project for good part of tie tine lias boon a difficult one.

t’.io vJu.'hc ■; .' t

eiil.i

hospital has boon kept at a steady pace, iho e^peri-uontal

part of it, did not pick up in tins or sufficiantly.

~''-Q difficulties, sons

which h.-.d bion indicated above c:v. bo sumaricod so follows s

(2)

ih_ shift fraa ■ clinic oriented hospital to

c

difficult process paxTciculsrly b .cr.’ce of the ’.cental attitude of uedicol

co.rrani'sy hospital has bean

-.iho .-.lii’.oirri deeply co .: ittc.' to COkrnmity aexvice, it was difficult

for t;. ■'cnnlatlon to help them siove ir this direction 3?a;idly raid adequately,

'■ills delrynil

Co,.:::'.i ttoc

. -.ru^reso.

ell

It

ba added that L'.u (Xmin.an, 1 '.n.'.c;in...

; aporcciative of ire cor.unity approach.

influence in ;;re.;ter p- rt helped, in ilia

His

slow ahanjo that currently is

fchi: : pl.;rso.

r j,.orl iiroparod fo.-..’ purposes of projeot v.’ork ;.<•- the social

(2)

cci-.r.tict we;.; toe i-rii-ojolopicully oriented irr-. did not provide adccuato

i'-ifaaxition foe dcvaloniri; a pro.;X5.-.ne with strom; propra'.'.r.e oontent.

lie,'..' '.ci.

(?)

Shis is

u :•. xdicJ ?•;■ p'aiiiariiv; irius facie for i’.c pre Joab work.

'A'-o p'..’oj‘.ct was expected to pot . adical and oikor support fror on

intourrtlcr."?. u;;? .m, uhlc’i did not u/iorii’lfau st all.

-sic is u.'d was a

contizui. \; problem, and has not helped to increase tl.o iU’oprun.^ content.

(4)

Th© project ;-lt -j jh dolcyod is now beir-.; recast to rofleot co- unity

orientation including identification of local conmr.il ty health woxkora to

■ /. ■

pit

■ - il

'-■ a, "CJV;... .

;eti ,<

. 1 tixn <■ si.-sx:.:

likely- to so hoj.':; liooivl rrr.i iialp£ul.

\'<5 A'

Ccil^

( r5^ - /" <:/ ^cz^c- 1,

!/i

«

fest/™ n 4

mi(-<?;/ ex/’ez/io? 7<

Che,

7/

/c/72 -

He>

&

*

Vdey

J~ I

^i._

Li'~>

-

}

Ct,

Cs-> i'&^-te.k&’cJL

I'i- ^/a-r-)

/?

/<

AuZo/flx

— Ab

Z^c) by

(

ci~

I'

I

.

/ 775

/ 7 7^ d^L- 7 7 ?g

^Ot°l

giy2-

f33<5

^152-

73

/d6

io Z

III

27

n

2-0

2-h

13

Is)

32-

34

/ 7 7 3 1 / 7 7M

II77 8

I- IblAl- No

1

O- gjj MTP.

. 63

8

32-

1

In patient

FMIL'I Pl-NNNI NliSj oPEPPT/Cn

<2 aj tl)EE<z-to

c4

OPD

1

oU-Totan no

zgo6

°7

17

MTH1S,

tU

4. DTH&P.

.

27

O P&PATToNl

S’. Smapn ?<oa

•

<o- T&IPN&

7£T.

22-

5/

3^

/\NTl&,EN

l/Aoc

ii\^

7z/\

Iron k F&i~/o 4czz>

i

1

^>8-

lit

7/

74

3372

6 18 8 _

//p 80

3 8^o

77°

12^

3-^0 '

~ToVoI m* r

7©

/o 7<7 ?

/°/77

/f w'MZV

I^VU^IY^. 'r^AZx-'

*A-fti

~h-&vi. f\\aA—

£

11/^—

/^7«

<x ??

r'tdA.-

4

V

^77

i

1

X

X

X

x^C't'T/£&‘'_ \ w/L

*-

AUft^TlTlQdfc fl.

3_on ^’*e Total Health Care Project in 24 ?arganas, West Bengal

INTRODUCTION

The Banerjee Charitable Trust was founded by Dr. Tarun Banerjee and

his wife, Dr. Anima Banerjee, in 1966.

In 1969, the hospital called

the Amiya Debi Hospital was built in the rural setting at Narendrapur,

24 ’’arganas district, 9 miles from Calcutta.

The hospital contained

12beds, an airconditioned operating theatre, and an out-patients clinic

with a dispensary; all medical services, both for indoor and outdoor

patients, are absolutely free.

The hospital is run mainly on the

voluntary services of Drs Tarun and anima Banerjee and their friend.

Dr. Ajit K Dutta.

As the hospital became popular, it was necessary

to take on some salaried staff a part time medical officer, a resident

qualified trained nurse, two female nursing assistants, three male

duty assistants and a part-time pharmacist.

All expenses are borne

by the Trust and medicines and other medical help is provided for the

village population, but the main emphasis is on family planning

operations on females.

In early 1972, through some mutual friends contact was established with

the Family Planning Foundation in New Delhi.Q$A scheme was presented

for a Total Health Care ’reject serving a population of about 20,000

people spread over 13 villages in this predominantly rural area,

comprising both Hindus and Muslims.

Professor S.C. ;.<avoori,

Executive Director of die Foundation, visited the hospital and its

surroundings soon thereafter.

He inspected the activities of the

hospital and discussed the feasibility of the Total Health Care Project.

The Foundation ultimately decided to provide R?'. 1, 50,000 over a period

of three years with the Trust contributing ft". 50,000 over the same

period.^

A programme was drawn up, divided into three phases :

Phase I

To have a research programme for deriving certain basic

data (base-line of this population) through the work of

research assistants who will be collecting these datas

by house-to-house visits.

-?hase II

The dates were to be further qualified and specified with

more emphasis on family planning and in relation to

other health care like immunisation, sanitation, health

education etc.

'base III There will be an action programme with a view to provide

prophylactic and curative health care, the quantitative and

qualitative measures of which were to be assessed from

scanning of die datas collected from the first and second

research programmes.

These activities were to be directed from the Amiya Debi Hospital.

It has been the experience of die Trust that the motivation for family

planning operations can be generated very satisfactorily by providing

comprehensive medical care and attention for die entire family.

2.

®//a s the Trust was now involved with the finances provided by the Family

Planning Foundation, the trustees of the Banerjee Charitable Trust

decided that a separate organisation should be set up to undertake the

The Total Health Care .Project.

A committee consisting of the following

was brought into being:

Mr. C.R. Irani

Chairman

Dr Mrs Anima Banerjee

Hony. Treasurer

Dr Tarim Banerjee )

Mrs Threety C Irani )

Dr Ajit X Dutta

) )

Members

On die 30th September, 1972 His Excellency die Governor of West Bengal,

Shri A.L. Dias, formally opened the ?rojact at the hospital premises

where Dr. J.C. £<avoori handed over a cheque for R>.50,001),being die

first contribution from the Foundation, to the Chairman of She Project,

Mr. C.R. irani.^/

The plan of the x reject is set out below :

Action Programme:

Planning Programme:

Phase I

Collection of basic data of the

population and analysis

Medical service and family planning

operation at autniya Debi Hospital

Jhase II

Collection of data with emphasis

on family planning

Phase III

Preventive aspect

Medical service and family planning

operations at Amiya Debi Hospital

(i)

immunisation

(ii) child health care

(iii) adult health education

The first phase of the work was completed on 31st December, 1974 and

included (1)

the appointment of the Research Scientist, Dr. P.K. Bhowmick,

D.Sc. (Calcutta), Reader of the Department of Anthropology, Calcutta

University.

He was entrusted with the research work on an honorarium

of FA 400 per month.

(2)

the appointment of research field workers and statisticians

after scrutiny and selection by the Project committee.

A field super

visor was provided on an honorarium of K. 325 per month and the other

workers K.275 per month.

In addition, Dr and Mrs Banerjee made

available the ground floor of their house adjacent io the hospital to

enable the workers to stay on the project.

(3)

drawing up of the pro forma incorporationg door to door visits

3.

visits covering the entire population of about 20,000 people spread over

13 villages in an area extending over five miles from the hospital,

£he

mass of information collected in this fashion is now being statistically

analysed and a preliminary report prepared by Dr. P.K. Bhowmick is

attached.

The second part of the programme of the research wing consisting of

data collection with main emphasis on family planning and health care

is in progress.

This will be completed by the end of March 1975.

As for the curativeaapect of the work of the hospital, we have to report

the average out-patient attendance is noted in a register kept for the

purpose and is 60 per day; ligation operations were performed on 74

females during the period und-.-.r review.

The working committee of the Project is set out below:

Project Chairman:

Director:

Dr. A. Banerjee

Surgical Specialist

Gynaecological Specialist

Medical Officer

Nursing Sister

Female Assistant

Male Assistant

Mr. C.R. Irani

Dr. Tarun Banerjee

Co ordinator:

Dr. Ajit K, Dutta

Social Research Scientist:

Dr. ?.K. Bhowmick

Demographer

Statistician

Male Field Worker

Female Field Worker

Auxiliary Nurse

Before commencing work on the Project, Dr. Ajit i< Dutta and Dr. P.K.

Bhowmick and two field workers visited Gandhigram by courtesy of the

Family Tanning Foundation to watch their operations.

Recently,

Dr. S.iC. Misra, Research Specialist attached to the Foundation, visited

the Project twice, once in the company of Commodore Mehta and again

with Prof J.C. aCavoori.

Dr. Misra spent two days at Narendrapur

watching the field workers in action and helped to assess and guide diem

in their field work.

We are anxiously awaiting his report, on the basis

of which we propose to plan the third phase of the Prophylactic Health

-Programme.

Problems ^^Difficulties

A major difficulty encountered by field workers is lack of cooperation

from the population due to ignorance and exaggerated expectations.

Initially, there was some resistance to the concept of family planning

largely baaed on communal considerations, but this has been gradually

overcome and the confidence of die villagers has been earned by the work

done in the hospitalmainly in the out patient department.

It would be of

great help if slide projectors and other audio-visual aids could be made

available.

The ’roject considered providing a skeletal nutrition programme for

under-nourished children but has decided to put this off for the time

being because of administrative problems.

4.

I

As regards the curative aspect, the Project is trying to secure a Vacurette

and if we are successful in this effort we expect a major dent to be made

in the task of limiting families.

A dm ini s irative and Financial aspects

The programme commenced in October 1973 and by the end of March 1975

the Family Planning Foundation will have contributed PJ.75,000 and the

Banerjee Charitable Trust R.30,000.

We accept the need for adequate

statistical data but cannot help making the observation that most of the

assistance provided by ths Foundation has been absorbed by the research

programme and the curative aspects of the work at the hospital has not

received any direct benefit.

We are apprehensive that in the third

phase die action programme related to prophylactic care, including

consultancy fees, is likely to be so expensive that all the financial

commitments made by die Foundation will be absorbed, with no direct

benefit to the curative work at the hospital - so vital for the achievement

of our common objectives.

Also, it would be of great assistance to the doctors if the Foundation felt

able to give some indication, as to what is likely to happen at the end of

the three-year programme.

If the Foundation feel that it will not be

able to assist thereafter, the Trust will have to take decisions now on

the future work of the Amiya Debi Hospital.

Needless to say,

continued work on these lines is imperative if the results achieved so

far are not to be lost and for work of thio kind a sligHliy longer perspective

is also, in our view, necessary.

23. i. 1975.

MH- 13-

TOTAL HEALTH CARE PROJECT 5 1973—74

REPORT

On

FAMILY PLANNING ACTIVITIES

/' in 11 villages and 2 Semi-urban

Settlements of Sonarpur P.8.,

24--Pa.rga.nas district,

West Bengal, 1974/

EXPOSITIVE REPORT

(September 197 6)

fUlMARY OF THE FINDINGS ON FAMILY PLANNING ACTIVITIES

BY THE ELIGIBLE COUPLES IN SONARPUR P.S. (1974)

In Sonarpur P.8. 11 rural and 2 semi-urban settlements

were investigated in the beginning of 1974 to elicit information

about the extent of family planning activities by the eligible

couples.

Altogether 2856 eligible couples were found in these

settlements.

Social group wise breakdown of these couples was

as follows

*

Rural

Semi-urban

Total

1521 (75.4)

450 (24.6)

1751 (100.0)

:

957 (93.6)

65 ( 6.4)

1022 (100.0)

c) Christian:

85 (100.0)

0 (0.0)

85 (100.0)

Total :2561(82.7)

495 (17.3)

2856 (100.0)

a) Hindu

b) Muslim

:

Out of 2856 couples only 19 per cent were found to

have ever-practised any family planning

method.

Social group-

wise classification of these couples reporting use of F.P. methods

reveals the following picture:

Rural

Semi-urban

Total

a) Hindu:

307(71.2)

124(28.8)

451(100.0)

b)Muslim:

83(91.2)

8(8.8)

91(100.0)

c)Christian:

22(100.0)

0(0.0)

22(100.0)

Total:

412(75.7)

152(24.5)

544(100.0)

Out of 544 eligible couples who had sone F.P.

3.

experiences 51 per cent declared to have adopted sterilization

measures.

was

Socialgroupwise distribution of the sterilized coup!

as follows:

Rural

a)Hirdu:

152(70.0)

b)Muslim:

41(91.1)

c)Christian: 14(93

3)

*

Semi-urban

65(30.0)

4(8.9)

1 (6.7)

Total

217(100.0)

45(100.0)

15(100.0)

207(74.7)

70 (25.3)

277(100.0)

Total

Out of 277 sterilised couples 56 per cent declared

4,

to have opted, for sterilization of male sponses (vasectomy) and

the rest 64 per cent was for sterilization of female spouses

Social group-wise breakdown of the cases of vasectomy

tubectomy).

and tubectomy showed the following picture:

VASECTOMY

CASES

Semiurban

Rux•al

15=54

25

1=24

TUBECTOMY

CASES

Semi-urban

Rural

105

50=155

IS

5= 21

a) Hindu

b)Muslim:

c ) Christi axi:

5

12

0=12

54=177

84

16*«100

2

1=

x£&

125

Out' of 177 sterilized wives 67 per cent

5.

to be 51 years and more in age.

were found

Classification of these wives

by social group, age and location showed the following picture:

Sterilized wives

age 31 years and more

age 5O.vears and less

Rural

semiurban___ Total

12

49

a) Hindu:

57

b) Muslim:

7

1

c) Christian:

1

1

Total

45

14

Rural

66

8

2

55

Semiurban

58

Total

104

11

2

15

1

0

1

78

40

118

Out of 100 sterilized husbands 86 per cent were

observed to be 56 years and more in age. Distribution of these male

spouses by social group, age and location reveals the following:

a) Hindu:

Sterilized

husbands

age 56 yrs.and more

age_J_5_ yas.and less

Dural Semiui’ban

Total Rural Semiurban

7

6

1

14

45

b) Muslim:

c) Christian •

5

Total:

12

Total

57

0

9

0

20

g

72

14

86

1

0

4

20

5

2

14

7.

Among 177 sterilized wives the large majority were

relatively aged and these wives were observed to possess already

4 and more fcliving children to look after in high as 69 per cases.

They were, thus, sustaining larger families before they got

themselves sterilized to st6p for ever further childbirth

disbribution of the sterilized female spouses by social group,

number of living children and location has been shown below:

a)

b)

c)

Sterilized. 'lyes_____________________

with 5 and less

with, .4, and_more

living children

living. chilsren

Rural

Semiurban____ Total Rural Semiurban.

Total

Hindu:

29

18

47

74

52

106

Muslim:

5

1

6

15

2

15

Christian:

2

0

2011

Total:

56

19

55

87

55

122

6.

Among 100 sterilized husbands those who were relative

ly aged were again dominating and 51 per cent of these husbands

reported to have already 4 and more living children. Sterilized

husbands with smaller ar larger famulies were found in almost

eaual strength. Classification of the sterilized male spouses by

social group, number of living children and location is noted below:

a) Hindu:

Sterilized husbands

with 5 and less

living children

Rural

Total.

Semiurban

10

54

24

with 4 and more

living children

Rural Semiurban. Total

5

50

25

b) Muslim:

c)Christian:

9

5

1

0

10

14

5

7

0

0

14

7

Total:

58

11

49

46

5

51

9.

Family planning activities of the eligible couples

over the eleven villages under study were not at all uniform.

Proportions of the couples who reported to have ever-practised

any F.P. methods varied from a high 29/i (village Kumarkhali) to

a low 2# (villages da.gannathpur and Ukhila).

In the following six villages it was found that 200

10.

or more of the eligible couples concerned ever-practised F.P

methods: a) Kumarkhali (290), (b) Jayenpur (270), (c) Bingolpota 270)

(d) Chowhati (.250), (e) Hischintapur (250) and (f) kamchandrapur

(200).

In the semi-urban settlements of BLACHI the eligible

11,

couples having some F.P. experiences explained for 290 cases, where

as in semi-urban Jagaddal the comparable couples accounted for

only 240. Bulk of the couples without any 1?.P» activities dominated,

thus, both rural and semi-urban areas under study.

12.

As far as sterilization experiences of the eligible

couples having ?.P. activities are concerned it has been obtained

that in 8

out of 11 villages such experiences had duly been recorded

1n semi-urban settlements sterilisation cases were also available.

In the following four villages adaption of sterilization method by

the eligible couples for the most effective family planning was

most markedly noticed, (a) Hamchandrapur, (b) Jayenpur, (c) Bingelpo-

ta one (b) ^ischintapur.

15.

In this context, special attention is drawn to the

villages Jagannathpur, ukhila and Kusumba. Eligible couples of

these three villages appeared to be apathetic to ary family

planning activities.

An

agannathpur as good as 169 eligible

couples were found and among them only end only 5 Hindu couples

reported to have ever-practised any F»P. methods, --one of these

couples had also opted for sterilization.

In Ukhila out of 176

eligible couples only 4 couples (2 Hindu and 2 Muslim) evinced

practise of F.P. method and here agan, more of these couples

went for sterilization.

Lastly, in Kusumba 99

..ere found and only 5 couples

experiences.

eligible couples

(1 Hindu aid 2 Muslim) had B.P.

here also no case of sterilization was reported.

Eventually, the eligible couples of these three villages should

have the topmost priority in aiy family planning programme that

might be in operation in the area.

In the sample villages when 82 per cent of 2561

eligible couples reported no family planning activities it goes

wh without saying that enough groundwork is still needed to motivate

the couples towards birthcontrol. Of these couples 57 per cent were

found to procs:: possess alreacjy 1-5 living children and they must

be reached immediately with a hold family planning programme and

action-programme for sterilisation has to be

er delay.

This programme

launched without furth

is equally urgent for the semi-urban

couples.

15.

Favourable attitude towards and effective adoption

of F.P. methods had already been shown by a segment of the total

eligible couples of Sonarpur P.S. and the same needs now to be

intensified among the non-adopters.

in this direction, the

Hindus of both higher aid lower caste groups had given the lead.

Initial resistance against family planning measures had noticably

been broken.

More perusation and patient shall no doubt, help in

the longuun to remove this resistance in favour of the programme of

population control.

16.

It was

true that relatively a little aged male

ar female spouses among the group of eligible couples with F.F.

experiences and more than three living children

majority opted

had in

for stei’ilisation method to do away fully ri th

further procereation, yet these sterilized couples shall play the

most vital role in the local society in motivating their neighbour

families as well as their counterparts of younger age-groups.

Family Planning education for sterilisation must he intensified

among the eligible couples, especially among those who had already

three or more living children in their individual family.

REPORT ON FAMILY PLANNING ACTIVITIES IN

SONARPUR VILLAGES AND SEMIURBAN AREAS

Luring the survey for family-oriented basic Health

Services in the selected 11 villages and 2 semi-urban settlements

of Sonarpur

P.S., 24-Farganas district, ttest Bengal (1974) an

attempt was made to collect information about Family Planning (F.P)

activities of the eligible couples per household of the survey

areas.

From each male sponse of the couples relevant records

were also taken on following items of information: a) Religion

and caste affEEix affiliation, (b) Occupational, status, (c) age,

(d) education, (e) number of living children^

For the purpose of the present study a couple has been

defined as follows: a husband and a v/ife, both living together

with or without any living child at the time of survey formed

a couple.

If a husband had more than ene wife, therewere as

many couples as the number of wives.

Further, only those husbands

whose wives were between 15 and 45 years in age constituted

the group of eligible couples.

Family planning activities of

these eligible couples have been studied

here with special

reference to social group,, age, occupa.tion, education, number of

living children of each male sponse.

Family Planning activities have been measured by the

practice of different birth control methods either by tile male

or female sponse.

Ssp Special attention was given to sirinit

elicit information about vasectomy and /or tubectomy cases among

the eligible couples of both rural and semi-urban areas under

study.

Husbands reporting 0-3 living s’lldrc." children have

been examined in terms of smaller family, where as those reporting

4 and more living children were considered to posses larger

families.

Age-wise distribution of the husbands has been shown

in terms of three braad age-group, namely, (i) 30 years and

below, (ii) 31-40 years, and (iii) 41 years and above.

the basis of religions

On

affiliation the husbands have been

:i-rnined under three broad social groups: (a) Hindus, (b) Muslims,

and (c) Ohristiqns.

Occupation-status wise the husbands have

been classified under five principal groups: (l) Agricultural

workers (cultivations, agricultural labourers and other workers

related to agricultural activities taken together), (2) Service,

(3) Manual labours, (4) Others, and (5) Ho Occupation.

Education

ally the husbands have been classified into two major groups:

(1) Illiterate and (ii) Literate.

A) FAMILY ELANMI'IG IN GENERAL:

After a through shifting of the information elicited by

the couples it has been formed that altogether 2856 couples

satisfied the criterion of eligibility.

Of these eligible

couples 82.7 resided in eleven villages under survey and the

rest was from two semi-urban settlements of Elachi and Jagaddal.

Among the rural-bred eligible couples only 17.5 reported that

they practised one or other methods of family planning.

The

large majority never practised any F.P. iiethods to check family

size.

Among the

ever-practised sub-group of households those

who were 41 years and more in age dominated as a single major

group (82 8.2?0 .

Those who were 30 years and below in ghd

age a very negligible portion (1.4/0 reported to have some

form of F.P. activities.

As a matter of

part, it is found

that in villages out of 412 husbands who ever-practised F.P.

methods as mary as 378 were 31 years and more in age.

Young

adult husband aging 30 years or below had yet to respond

favourably for birth control measures.

Among the x ever-practised sub-group as high as 74-5$

were the Hindus.

The Muslims accounted for only 20.2$.

The

remaining psr proportion was explained by the Christians.

Within the ever-practised sub-group of the Hindu husbands

(507) it is

interestingly observed that those who maintained

smaller families (1-3 living children) reported use of B.P.

methods in majority cases (S2$ 52.1$) and next was the position

of those having larger families (4 and more living children).

Among this sub-group only 3 per cent reported no living children

and even then they practised F.P. methods.

The Hindu husbands

who declared to ps prossess smaller families and to practise

P.P. methods were mostly middle aged (31-40 years).

In contrast,

the Hindu husbands who were practising P.P. methods and prossesing

larger families were mostly 41 years or more in age.

Within the ever-practised sub-group of the Muslim husbands

(85) the majority reported to have larger families (54.2$) and.

they were 41 years and more in age.

Similar trend was also

true for the ever-practised sub-group of the

Thus, it may be

Christian husbands.

summarized that in rural areas the middle

aged Hindu couples having smaller families showed greater

inclination towards P.P. activities, were as the aged Muslim

couples possessing larger families evinced Stronger inclination

towards P.P. activities.

In general, the Hindu couples, inespective

of age and family size, were more motivated to ever-practise

some form of P.P. method.

On the otherside, among the never-practised sub-group of

the rural couples (1949) the large majority (37

1$)

*

to prossess smaller families.

was found

But those reporting to have larger

£2Ei±±ESXxB^ikHSHKxnpmstiKsxfcsxhH3JEx£RxgEX

families

were not insignificant in magnitude (54.50)

*

important to

It is

note that of this never-practised sub-group

as good as 11 per cent declared to prossess no living children.

On the other hand, it is also

observed that with the increasing

age of the hushands who never practised any P.P. methods the

magnitude of larger families increased in each of three social

groups in question.

Within the never-practised sub-group of the Hindu husbands

1014 smaller families dominated in the majority cases (47

50)

*

Wn-i 1 e within their

’.

counterparts of the Muslim husbands (874)

larger families (45.10) dominated, this very trend was also

true among the Christian

husbands.

In general, it may be observed that the 'never-practised’sub-group of the group of couples living in the villages

under survey should form the target group sf for F.P. activities

and of this sub-group those who declared to possess already 1-5

living children must be the immediate target group.

Since within

this immediate target group the eligibile husbands aging 51-40

years formed, inespective of

religion and caste

affiliation,

the dominant segment, F.P. education and services has to be

concentrated first among this particular age-group.

Husbands with smaller families but no family planning

activities were found to fall mostly within the age-group 51-40

years in every social group and eventually they are to be given

topmost priority in any action-programmes related to family

planning.

Through

relatively speaking, the Hindu husbands

had shown greater inclination towards F.P. activities than the

Muslims or the Christians, yet the over-all social climate was

not found

encouraging enough

to favour any quick change

in traditional motives which guide family building activities

of the rural couples of the area.

Scanning the level of F.P. activities of the eligible

couples

of the sample 11 villages we find that they evinced

a wide variation.

Unequal- response for and acceptance of F.P.

methods were markedly present within the villages.

Ingeneral,

the villages which were dominated by the Muslim families showed

quite a lower level of us response as well as acceptance.

On

the other hand, the Hindu-dominated villages maintained a good

level.

The range of variation in the magnitude of the husbands

the sample villages was from a very

practising P.P. methods

low of 20 (villages Jagannathpur and Ukhila) to as high has

290 (village Kumarkhali).

Villages Jagannathpur and Ukhila are both pzs populated

mostly by the Muslims.

Though the Muslims are the major

inhabitants of village Kumarkhali, yet the Hindus reported

use of P.P. methods in greater number of cases.

In village