RF_WH_.6_A_SUDHA.pdf

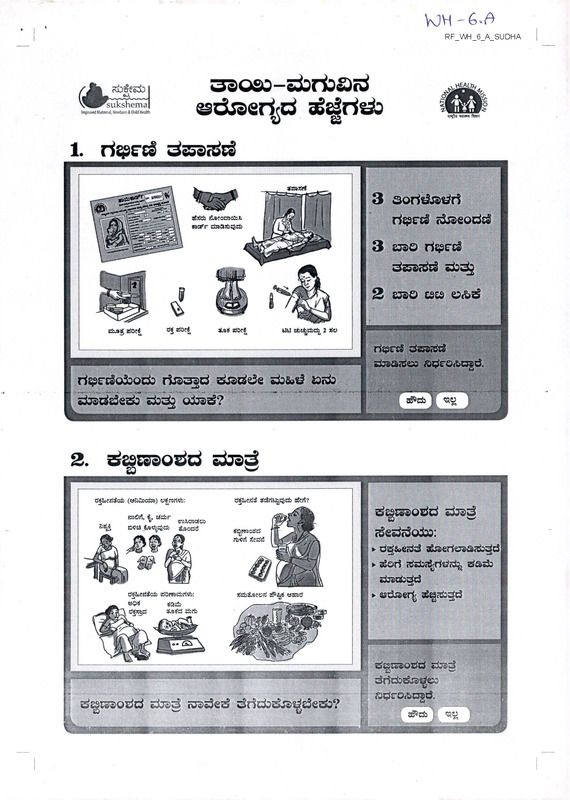

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_WH_6_A_SUDHA

o

53080-darfoad

ssdreertd

age3ris&

V

83

/■Jgijt ?±)^ei>

vBBFsukshema

Impnwed MMmwl Newborn & Child Health

'•Witl.F<i>if)« WM fhne

1.

acsstri

3 sorfc&a^ri

ri^cES rijaeods^

aiddb rJjseorootoX

iran^r dsaCBdjdicb

3 era©

dcSsrdEi 5±i^2

2 essQ ES£S

dbjad, doeS

d-S dOe<

WU tisidbdb 2 do

qtatf doe«

■

f^e-$ dasa^d

djaadoo ade’O^ogd.

ri^E-dofrodD risasred s&adde dowsi iodo

.-,■■■•.•.

--' ■ • *,

■

■

-:«»

- ■

•

.

..

--

-

■•

.A.

■: ■

• ■.

...

daaddeds dsda

odad?

—o

I

I' rz; i

.

k taw

~

2. desEsao^d

drad

ED

o

d&oegteoi) (WsD^ocdsa) e^rari^:

ssOrt, &, dzhr

. _,

*>

tnxxMtVi

o?a„M$S0di ijsodd

A^JL

djrkfwi d^rtt^^db aSeri?

d^Eaaodd doad

etonraodd

rb<?rt jJede!

I deddo&D:

y^jp

| ► d^&ecdd a»raeriCTa<&3d

► aSori

&,»

1\

d^SoesJSci dOrradbriVo:

t5$?$

tfasb

dJrX^S

d/sjrd dart

djadodd

► asdsaer^ d^z&dd

afch&MOKl a?5^ warod

(tswi

-

UZ

'\’h

■

■

■.

d^Eaaodd doad roaded dridodia^dedo?

a^sraotfd dasd

tv dtictos&a^eo

| fJ^E:'o*n§d-

L -IT^I

1

' r

x£>3e&±i

^B^svXshema

Impwred Mjtwiial, Newbwn & Child Heakh

saoeo-cabrtoad

esdraertd

de^rida

W

£3

A

<i«<lii ki<«i Pm

3. rt^racdo^ ©sssodod ^desr&o

T

CO

ri^racddod 9

aoiida ©djod

w

q±05DdO W&3

3dcSjaesg

die)^ esdQ. de

ssddodes doda

sadad ©zsaodd

eadsaridd^

n

e>3c wg>o^

sSrfe^f*,

grTIVi

vo^csUd

4)^

enoO s&te3,

3jsoc33

riada@& d|d$©od

dJsd

23&dca

-x>

dddad&^deda

ri^rE3o±>®

dodaejdaci 16

©siraoda sss^rida

oiros^s^?

ssd^ iuadeda

draddedo?

3eg

□SjSt^.djs’Cs^)

e>z$9 31fi)^r

coOrt eSjsecJ)

3esd—’ fcsU

U-®

o3js>c£)0&o?3

oTOTjcScdo

TJS,«3 .

r/

*?»

osjacScCood

djs^d M

olfcc&o&od

33

f y^n/c^

S^OeS

<3Od <53:55)^

'W

”

J

'

[ spssaobd O5&®rtecto

.

atoerto

' I

ffii?£ra*a®tf.

, a^c* I

'

I

B

«*#

fl

aaoeo-dsrtiad

ssdraerird

ddrids

V

S3

vSB^iSshema

Improved MiternH Newborn & Child Health

«i<wi ft»w

4. a^odd &dd

Q

t»Jbdrt<#jS>l 4rtoct»crfa^^)d:

4 DOS 5 OSO

«as»C

t>4 1^4S

<U^

saoafd

fiil

^®*

C&»dt330t*

eSortrt c-iCnci

tfcrbart tJewci

irtOcfc^cfc

crassrd ^ddnL

cftal’Jd

£j»d:5e irtocfcSe*

•ms,*'

77?

atortrt w^S/$

aSJjjrtcart

^cb

cU^AtW *

K&o&ad <vd3

a^Jo±^n»rt cirf

.twaijiVes ui^cb

c&aas&as&aera.

aSOrtrt a&»;7t>c»rf fRsJ 2 ad

ero«=ijt»<Jw dibrWfi, ucs^tSefc

I11

s^odd

itsIp

atori Addri sdE-o&cjad.

aSoriri #<3e<&

siraa^geSedo?

II ||. I.

\

^c^'T w

5. cddsso cfi®©^risb

-’< -- ./,;?3TSSs:

--S >,,',

J- '

oiofsseSrte*

urtA dssSoa

cdsaro o&aeeicSrisi)

3c£)«^ca> ofcbnsf),

de otoescSridcktj

ddo±o«^ct

«

bI

I

ddsao

f

■ ■

. ' '

2E

'

f

.

.

.

.I.

^©■scd&od &rfc>zto^3>

ero^Gtoeriri^ecio?

V

'

. •‘'*'-:>;,WMig*

■

..

.

■ '

\.. '/

■I

e±k£) I

f;.:

^25 •

■^•.:..«W.

ddda^a^

sdE-o&ngd.

'

- a'....... .... —------- ' ’ • : M

............ ^g. W

h

mi? j

a®Qe3-5±>rtoa<d

ssdraert<d

sgdds^

V

S3

^l^sukshema

Improved Mottroal, Httvbcm & Child Health

4®Sf

<!'<)« «R«4 faVH

sdfdsd

6.

ddd ddaoiades

VsJa^

d^a/d^yxi:

CB£eS0S»tf,

dada doddd 48

rtodri^fg oiradde

<

d>t>£c&,i acda

ucb^jda

daaoddd&adeadada.

sade^n dododaad

dodd 2 od ssddcdaes

\ t Az —y

12 rtodnostv.'j ddtf dort

eictrad dix^d

enasodadededa.

4Vqf rfjidco dartadcj id,

▼

wtddc

sada^ds

<doddd 48 rfodrid<g

g&dd <&±)o±)d<g

■dodo eadod djaddarfeto o&as^? ®dd, <aadeda daaddeda?

-

ss^d agori siJe>a*d

riodd 2 aad erusoisos

a^FO&ngd.

................

•

.............

7. &C3

dexadsA

aroear^jiad

don

drsdoiefcj sn>tx

fcBdad dad. j

^i^daadat^ds <

sli»du Arad

awifej dartadrt

fcaxdfd

Cd asaeaa esd^d.

6 soridddr? ad

da^m^od©

•ad^ dartadrt

aspoarfsiadl^

sgjBudsa ssct £)^.

11

I -vU-a

25i>da^^aaaart dartadda^ did dacA&iraVdefe

asaex saw

u e^edecdsa

6 aoritfddrt

ddaraax

das^ asda^da

ssteoa seatoari 6

©otrfeid^ ridwadw;

PHE

' ’TT

' Jt’-.

MBI

B

, &dca&ngd.

' adasaeaa aedasaad ddari riaaaddeerad 6

»a

| ©oddda odaa^s^?

Vt-sat-

.

aKiME"""

I

■ I

33Q£o-e±>rtoa<d

©draeried

dddds

U

S3

__

^l^sukshema

Improved Metemjl, Newbern & Child Health

A

eisfla wwfl then

essrao&d ©dcari^o

8. cdsdezsd

»3e t$ea

ziradrsado,

s^s)b8><S«be)Od353ari2»d

24 rtotfofcO

6 xJo^o^ tf&ds dxra^

dtoefcaoart

e^eari^r^j rbdoa*

essd

dz^ eszsa&aa.

elc Z3e)O3

:

eatortsb

d^e^de«b^d3

dusd^S <3£icS «3td3S$dj

CO4><t0

eruaaiiaoQcbd)^

deaod dsaSKsb t!o333rt)S$d3

■

■■

■

■

■

‘Etdo^db fc^da

ieradad ssfe

£j saw.

ddsr sdtfd erbE^ds

jbaoidc

^ebs^ds,

■

djai^b uosjartas^db/

wcbdjds

'acbdjcb

dderad Szbades

dodo adod

19 eszsaodd

ssz^ddo odads^?

®d^ <oad<g<&

adaddeds?

voiiuaud i/aodd

wsod alresj

^sraabci e^eartecte

dedddoa rt^rtvart^d)

£2<ggri atojertoD

■

B

^©<bC5g^.

fe • 27 -’.

L^£.

Mi -

Bum

..V^WrW^’ r

•

■

ssGao-edrisad

ssdraedd

ddrisd

6

S3

(JL---**---

VimiBr sukshema

Improved Maternal Newbern & Child Health

ri’tfta wrrw fhw

9. cdsdesad

dartadrt^ did

dbonx

iC, ics^rtfrt

aded*. arattasdda

aSji^b tdCrt

ara^dda

dartd*. uijctocd

*3 dWAarf!*

Kdasi fcsadjbj 7 art

xajrtdssajJrf

Dkjodod

e»d«± esdj^

ga zbrbaid

a»a^,

@7s>a^a<±^d2 aed

essTOErae.

(d

*^dfid rtodoSci

OXS araizbsi'Cb

X* U

ds&rad '&Ebad

| ©di^oiia 7 ©osirisid^

I rtebsdsa sdreAagd.

I ddarad adsazd esd(d aedoaad <u®d)

•

7 esodrido oiras^4?

I

IO. S3c)£3Q3O^

ro

••

-•■-*•

■

••

‘

•

•

•

■

--•.■-

•

-

■

•

-»

i

^£3F&0

dru gjasaoaoi)

g3ae<d oe? dsaeriri^

e^>

wxcreud tfjjodd

d^dodd. gs^ridzd^

ddcs rfc)dja&

clrsc^otood

ts^S d^ ^d

ied,

idf&wd)

dxiDdg truid

sSjdjdes esad

tag Etosssrtditd

rfjsd

rtdzjsrbd)^

• :

ddoddeda.

W z&ra^&sed)

I sissaedbd e^tarisdeg

:;rt:S‘S;iSS

| gssEsoacxt^ dods adod 11 essssodd

| ds^rids odaddr? &>dE| roadeds s&addeda?

Cxkt ....^.iBBaegat.

..-. rrwi

| ,e$^r? dsaeriex)

■<?

**

F-

ssoec-Etorfcad

esdraertrd

ggddsd

U

S3

<Jn

^I^suksherna

Improved M»temH Newbern & Child Health

A

wr<wi fttn

11.

aS^eesoisae £>&dsjaoeori,

es&& o&dd^aesari

dosaaddoa6 o&ddjadri

‘©&drida

esedd dsa ddd'.

^(&«3aFQ&)

rto&scot&so

Xa

'I

<iJc>Q£Od«±^

f>

I

a^ejjUFE6-^

'

-

. ..,.

.■,„

. *,

--iMk

-■••■

— <*.' —

■••>.•

•• -v-..X.V- *,

:

•

7

n)^ro<&c3gd.

I odsd odad draeririsr? oiraaari

gj| .. . .

’

..

...-.-■^

I asadddedo?

3a5

Q&de&c^

12.

vo^ti BazaSiatdO^

dado dartOTta

adolfjoi drtert

«tbs^ 3 ddrti eoad

' ^da^ddarta

cd&rte rddasS

aec&Drt:

s£r

SSS^OiS iUSOW

iraodjjedjf

jotoJjo &U3CW

c&MeaSrte

4<tofc

/

©oddades.

rioades a^ssd®

C8

alraeddrtsb

dsbot-a.

Wd3*-U CTioo—

/

I s S • S0 <

do^d ddod

SJiOibC &UJOW

©o^dades.

otafdFSrteb

i1

$£&

drx fct&owd tfrso

;

dowoa doa<£a oSaaeesdodad^ odad

i esdda&djaddeda?

_____

. . .:

.

I.......... -.7,

i£t3»w odeas

®si=la<’u^sa^e»

fe

ffitfco&rod.

B^WwiL .

"" *

J

2

I-

33Qe3-5±irba<d

/Jh ^ee±)

__ _

ssdraerird

v

^■^sukshema

Imptored Maternal Xwborn ft Child Health

*

as

<i>sJlq kiwi Pith

: dad wzpaod zbWaou £eo§,d doddd dozio

: dortrt daai dodaO dsad dz^djd^Ood doodad sarVa

erodes

Q

doagprar

ddoiodjda

: rtzprf^, darao£ daztra w^oi ^Wso’d^da

erode&d rtso^

zjs?dwdjdad rtooag): d^ ^4 tsdasa 2 Ood 3 asdodad dza rtao^j

sjAoSo

1. djBdeo eroded dsSo^oi/soaoart e^eabsron

ero^ds ?530dd.dd?.

dsfo.

kod -Sertuad ddodrt^ art

2. saod d37t£)cd wdjsertj-dtfrg

s^do^daeid dsaa&rs^.

3. 'siOdod 12 adoirW aodds4 wc& dsaS&aodo dd/te ddse^ edort adOs».

4. dddo^d ejez^rtd de£> arodeDdsd -d»^ dsaSo^oid^ d^So^zpad

de1?.

5. esde dsak^oid^ eroded dsSotfc&aodrtja d>^^ z^ad ros&bd dxiae^ asazsazb

de^eo 3?2j.

6. dsrt Sedo zorad

&aedoiO

d&oid?,

ra

co Se?uad dx3

_s

4

4 See.

7. esdaod dja3 d.a^oii wdoo ^gesaSo^. esdd erodd ddodaAdd d,do^. uodi

des? doodad dsaSo^ ^?dddd dodjado ^rodsad^an 3s?&.

Q

-C

&.

8. d?rt tsddo ddo droSo^ dead dodd ddr^a rodejadfsa erodedd rort

Q

&

9. e>rtd^dd

az^rtd

A

dsrt R>c3.

d^od

esosfrteb:

? ~’

< A'

► .sea 12 ddoirtVds, a-SI de?dea.

► djad rbodrt <side ddoi 3?ddesadd aa^dodo* do^d zjs?&.

► d?eodaran sadad dds? erocroddrgrt^da, zas?&.

► £>dc& ^?S)d dodd cadd^ doSe^cd zsaodiodde daasaxb zadsddjae

aoda doaeO^.

\

.

.' ..-i;.S«g»... .-A^SgM

■r

IJ

Page 1 of 10

HMJ 2013:346:13263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.13263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

Severe adverse maternal outcomes among low risk

women with planned home versus hospital births in

the Netherlands: nationwide cohort study

OPEN ACCESS

Ank de Jonge midwife senior researcher', Jeanette A J M Mesman physician assistant midwife ,

Judith Mannien senior researcher', Joost J Zwart obstetrician^, Jeroen van Dillen obstetrician , Jos

van Roosmalen professor""

'Department of Midwifery Science, AVAG and the EMGO Institute ol Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam.

Netherlands: department of Obstetrics. Leiden University Medical Center. Leiden. Netherlands: deventer Hospital. Deventer. Netherlands:

’’Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center. Nijmegen, Netherlands; department of Medical Humanities, EMGO, VU University Medical Center,

Netherlands

Abstract

Objectives To les: the hypothesis that low risk women al the onset of

labour with planned home birth nave a higher rate of severe acute

maternal morbidity than women with planned hospital birth, and to

compare the rate of postpartum haemorrhage and manual removal of

placenta.

Design Cohort study using a linked dataset.

Setting Information on all cases of severe acute maternal morbidity in

the Netherlands collected by the national study into ethnic determinants

of maternal morbidity in the netherlands (LEMMoN study). 1 August

2004 to I August 2006. merged with data from the Netherlands perinatal

register of ail births occurring during the same period.

0.63 and 58.3%, 33.2% to 87.5%), the rate of postpartum haemorrhage

was 19.6 versus 37.6 (0.50 0.46 to 0.55 and 47.9%. 41.2% to 54.7%).

and the rate of manual removal ol placenta was 8.5 versus 19.6 (0.41,

0.36 to 0.47 and 56.9%, 47.9% to 66.3%).

Conclusions Low risk women in primary care at the onset of labour

with planned home birth had lower rates of severe acute maternal

morbidity, postpartum haemorrhage, and manual removal ol placenta

than those with planned hospital birth. For parous women these

differences were statistically significant. Absolute risks were small in

both groups There was no evidence that planned home birth among •

low risk women leads to an increased risk of severe adverse maternal

outcomes in a maternity care system with well trained midwives and a

good referral and transportation system.

Participants 146 752 low risk women in primary care at the onset of

labour.

Main outcome measures Severe acute maternal morbidity (admission

to an intensive care unit, eclampsia, blood transfusion of four or more

packed cells, and other serious events), postpartum haemorrhage, and

manual removal of placenta.

Results Overall. 92 333 (62.9%) women had a planned home birth and

54 419 (37.1 %) a planned hospital birth The rate of severe acute

maternal morbidity among planned primary care births was 2.0 per 1000

births.! or nulliparous women the rate for planned home versus planned

hospital birth was 2.3 versus 3.1 per 1000 births (adjusted odds ratio

0.77 95% confidence interval 0.56 Io 1.06), relative risk reduction 25.7%

(95% confidence interval -0.1% to 53.5%). the rate of postpartum

haemorrhage was 43.1 versus 43.3 (0 92, 0.85 to 1 00 and 0.5%, -6.8%

to 7.9%). and the rate of manual removal of placenta was 29.0 versus

29 8 (0.91.0.83 to 1.00 and 2.8%. -6.1% to 11.8%). For parous women

the rale of severe acute maternal morbidity for planned home versus

planned hospital birth was 1.0 versus 2.3 per 1000 births (0.43, 0.29 to

introduction

Thu relative safety of planned home births is a topic of

continuous debate.1 Several studies have compared severe

adverse perinatal outcomes among planned home births with

those of planned hospital births.' 5 The rate of adverse perinatal

outcomes was low and not significantly dilterent in most

studies.'1’ although slightly higher for primiparous women with

planned home births in a recent large cohort study ' The authors,

however, disagreed about the interpretation of these results.2 6 7

Less evidence is available on the association between planned

place of birth and maternal morbidity, especially severe adverse

maternal outcomes, since these are rarer than severe adverse

perinatal outcomes. Several studies have shown that at the onset

of labour low risk women with planned home births have lower

rates of referral to secondary care, augmentation, medical pain

relief, operative delivery, postpartum haemorrhage, and

episiotomy than women with planned hospital births. ''3 ' •

Correspondence to: A de Jonge ank.de|onge@vumc.nl

No commercial reuse See rights and reprints

Subscribe-

Page 2 of 10

8MJ2013;3'l6:f3263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

_ ____ ___

Some have questioned the rationale of routine hospital birth for

low risk women because of the exposure to overuse of medical

interventions with potentially harmful effects.1 However,

although the overall rate of maternal complications may be

lower among planned home births, the delay due to

transportation from home to hospital might lead to severe acute

maternal morbidity. A previous Dutch study showed that the

lower rate of medical interventions is not an impoilant reason

for women to choose a home birth, but sense of safety is a

dominant reason to choose a hospital birth."' Therefore, even

though the rate of severe acute maternal morbidity is small, if

the risk would be higher among planned home births this would

probably be a reason for many women to choose a hospital birth.

As far as we know, no studies have been large enough to study

severe acute maternal morbidity among planned home births.

Of all Western countries, the Netherlands has the highest

percentage of home births and is therefore ideally suited to study

the association between planned place of birth and rare but

severe outcomes.’ " National obstetric, midwifery, and neonatal

data are recorded in the Netherlands perinatal register. In

addition, the national study into ethnic determinants of maternal

morbidity in the netherlands (the LEMMoN study; Landelijke

studie naar Etnischc verschillen in Maternale Morbiditeit in

Nederland) resulted in a database of all cases of severe acute

maternal morbidity in the country over two years.13 Merging

data from the national perinatal register and LEMMoN databases

provided us with a unique opportunity to compare the rate of

severe acute maternal morbidity among planned home births

and planned hospital births. In addition, we compared the rale

of postpartum haemorrhage and manual removal of placenta.

The main hypothesis was that low risk women in primary care

al the onset of labour with planned home birth have higher rates

of severe acute maternal morbidity than those with planned

hospital birth.

Methods

In the Netherlands, midwives in primary care provide care to

low risk women. These are women with a singleton pregnancy

of a fetus in cephalic presentation who do not have any medical

or obstetric risk factors that are an indication for secondary care,

such as previous caesarean section, and who start labour

spontaneously between 37 and 42 weeks.

If complications or risk factors occur during pregnancy, labour,

or after birth, women are referred io secondary care. After

referral, women may receive care from clinical midwives,

obstetricians, obstetric registrars, and obstetric nurses, under

the final responsibility of an obstetrician. Obstetric interventions

such as electronic fetal monitoring, augmentation, and medical

pain relief only take place in secondary care. The indications

for referral are laid out in the obstetric indication list.1- This list

is revised regularly by a project group consisting of midwives,

obstetricians, paediatricians, and general practitioners.

Women who are still in primary care al term can choose to give

birth at home or in hospital, assisted by their primary care

midwife. Women with a “medium risk" indication can give

birth in primary care but are advised to give birth in hospital.

The official medium risk indications according to the obstetric

indication list are postpartum haemorrhage or retained placenta

after a previous birth.1; Midwives may record other reasons for

medium risk if they think it is better for a woman to give birth

in hospital.

No commercial reuse: See rights and reprints

Data linkage

We combined the information from the datasets of the LEMMoN

study and the national perinatal register. The methods of the

LEMMoN study have been described in detail elsewhere.12 In

short, all cases of severe acute maternal morbidity were collected

from all 98 hospitals in the Netherlands over two years (1

August 2004 to 1 August 2006). Each month a local coordinator

reported all cases, or the fact that there were no cases, via a web

based form.

The national perinatal register database consists of data from

three separate databases: one for primary care (national perinatal

database-1), one for secondary care (national perinatal

database-2), and one for paediatric care (national neonatal

register). During 2004-06 an estimated 95-99% of primary

midwifery care practices and 99-100% of hospital based

obstetric practices entered data into the perinatal register.111'’

The three datasets are combined into one national perinatal

database via a validated linkage method.1' We selected all data

from the national perinatal register for the period in which the

LEMMoN study took place.

In both databases we selected women with a singleton pregnancy

without a history of caesarean section who gave birth between

37 and 42 weeks and had spontaneous onset of labour. We only

included cases in the LEMMoN study if severe acute maternal

morbidity occurred after the onset of labour.

Primary linkage of data from both datasets was based on date

of birth of the baby plus or minus two days and date of birth of

the woman. If there was more than one match or if date of birth

of the baby was missing in one of the datasets, we used the

following additional variables for matching: postpartum

haemorrhage more than 1000 mL. hospital number, and postal

code. Two researchers (AJ and J Ma) checked whether the data

were well matched. We compared the characteristics of

LEMMoN cases that were not linked with the national perinatal

register with those that were linked.

We excluded women who were referred during labour from

primary io secondary care but were missing the form from

primary care, owing to important information, for example on

their planned place of birth, being unavailable. We compared

the characteristics of these women with the total sample to

examine differences between the two groups.

Study sample

For the analyses we selected women who were in primary care

at the onset of labour. We excluded women who were referred

because of ruptured membranes for more than 24 hours without

contractions since their planned place of birth did not have an

effect on their labour process. To ensure that groups were as

comparable as possible, we excluded all women with a record

of a “medium risk" indication.

The study sample therefore consisted of women in primary care

with a term singleton pregnancy without a medium risk

indication, prolonged ruptured membranes without contractions,

or any indication for secondary care at the onset of labour.

Definition of variables

The variable for planned place of birth comprised three

categories: planned home birth, planned hospital birth, and

unknown planned place of birth. At some point during pregnancy

the midwives in primary care register women’s planned place

of birth in the national perinatal database-1. This information

is missing for some women: midwives may forget to record the

Subscribe: ■:

Page 3 of 10

BMJ 2013:346:13263 doi 10.1136/bmj.l3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

details or the women may not have made a decision on where

to give birth until the onset of labour.

The main outcome variable was severe acute maternal morbidity,

which was defined in the LEMMoN study in five different

categories: admission to intensive care, uterine rupture,

eclampsia or HELLP (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and

low platelet count) with liver haematoma, major obstetric

haemorrhage (blood transfusion of four or more packed cells),

and other severe acute maternal morbidity as diagnosed by the

attending clinician. Secondary outcomes were the individual

categories ol severe acute maternal morbidity; we combined

uterine rupture and other indications in the category

“miscellaneous.” Other secondary outcomes were postpartum

haemorrhage more than I()()() mL and manual removal of

placenta, both based on data from the perinatal register.

We identified the following confounders that may be associated

with planned place of birth and with maternal complications:

parity, gestational age, maternal age. ethnicity, and

socioeconomic position.1" IK19 Parity was coded as nulliparous

or parous. Gestational age was divided into 37 to 37+6 weeks,

38 to 40+6 weeks, and 41+0 to 41 +6 weeks. Maternal age was

coded as less than 25. between 25 and 34, and 35 or older. The

ethnicity classification is challenging in the perinatal

register- for example, women of Turkish or Moroccan

background are both classified as “Mediterranean” and women

of African origin are classified by some midwives as “creole”

and by others as "other.'' We therefore categorised ethnicity as

Dutch and non-Dutch. Socioeconomic position was derived

from social status scores based on postal codes developed by

the National Institute for Social Research based on income,

employment, and level of education. These scores were divided

into low (below 25th centile). medium (between 25th and 75th

centile), and high (above 75th centile).

Augmentation of labour with oxytocin and operative delivery

(caesarean section, vacuum, or forceps delivery) have been

associated with adverse maternal outcomes.1"ISIn a secondary

analysis we therefore controlled the results for augmentation of

labour and operative delivery (vacuum, forceps, or caesarean

for primary and secondary care, but this information is not

always consistent. We conducted sensitivity analyses for women

without discrepancies between data from primary and secondary

care for this variable and for onset of labour based on the

national perinatal database-1 only.

Results

Linkage of data

During the study period, 240 400 women who had no previous

caesarean section, a singleton pregnancy, and a spontaneous

onset of labour between 37 and 42 weeks' gestation were

recorded in the national perinatal register. In the LEMMoN

study, 706 women met these criteria and had severe acute

maternal morbidity after the onset of labour (27.7% of all

women with severe acute maternal morbidity) (figure j). Of

these, 56 could not be linked to data in the perinatal register

(7.9%<). Women with severe acute maternal morbidity who were

linked to the perinatal register did not differ significantly for

type of severe acute maternal morbidity, parity, and ethnicity

from those that were not linked to the register.

Of the total linked data. 10 101 (4.2%) women were referred

during or after labour but were missing the national perinatal

database-1 form and 52 of the women in this category had severe

acute maternal morbidity. Compared with all women who were

referred during or after labour these women were more likely

to be parous (31.29<- r 30.0%) and of Dutch ethnicity (83.4% v

78.7%). There were no significant differences between these

groups in incidence and type of severe acute maternal morbidity.

The linked dataset contained information on 230 299 women,

of whom 598 (2.6 per 1000) had severe acute maternal

morbidity. Of these. 172 973 started labour in primary care

(severe acute maternal morbidity, n=364), and for 439 women

(severe acute maternal morbidity, n-1) the level of care at the

start of labour was unknown.

Study population

We used SAS version 9.2 to merge data, and analysed the data

using SPSS version 19.0. Within eaeh planned place of birth

category we calculated the number and percentage of the primary

Of the women in primary care at the onset of labour, planned

place of birth was unknown for 18 070 and these women were

not included in the analyses (fig I). Another 2112 women were

excluded because they had a “medium risk" indication. Of these,

1248 (59.1 %) had a history of retained placenta or postpartum

haemorrhage and the others had various indications such as “no

prenatal care” and “use of medication (not further specified).”

and secondary outcomes. We performed logistic regression

analyses only for severe acute maternal morbidity, blood

An additional 6039 women were not included because they were

referred for prolonged ruptured membranes without contractions.

transfusion of four or more packed cells, postpartum

haemorrhage, and manual removal of placenta, because of a

low number of events in the other outcomes; these analyses

were done for nulliparous and parous women separately and lor

planned home births versus planned hospital births. For all of

Of the remaining 146 752 women in primary care al the onset

of labour. 92 333 (62.9%) had a planned home birth and 54 419

(37.1%') had a planned hospital birth (table 1 ). Women with

planned home birth compared with those with planned hospital

section).

Data analyses

these outcomes we present the crude odds ratios anil 95%

confidence intervals. We used multivariable logistic regression

analyses to control for potential confounders. resulting in

adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We also

present relative risk reductions with 95% confidence intervals.

Subsequently, the associations between planned place of birth

and severe acute maternal morbidity were controlled for

augmentation of labour with oxytocin and operative delivery

(both as binary variables). We excluded missing data because

they were less than 5(X for all variables.

For the main analyses we used the perinatal register definition

of onset of labour in primary or secondary care. Onset of labour

is defined in the register based on information from the databases

No commercial reuse See rights and reprints

birth were more likely to be parous, less likely to give birth

between 37+0 and 37+6 weeks' gestation, and more likely to

give birth between 41+0 and 41+6 weeks; they were less often

younger than 25 years, more often aged between 25 and 34

years, more often of Dutch origin, and less often of a lower

socioeconomic position.

Adverse maternal outcomes

Of all women included in the analyses, 288 (2.0 per 1000) had

severe acute maternal morbidity (table 2i ). Among planned

home births, severe acute maternal morbidity occurred in 141

women (1.5 per 1000) and among planned hospital births in

147 women (2.7 per 1000). Most of the affected women had a

blood transfusion of four or more packed cells. Other causes

Subscribe:

a ■ i.-subscfiticj

Page 4 of 10

BMJ2013:346.f3263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

were rare. Postpartum haemorrhage was the most common

adverse maternal outcome and this occurred among 2699 (29.2

per I ()()()) planned home births and among 2172 (39.9 per 1000)

planned hospital births.

Adverse outcomes were less common among planned home

births than among planned hospital births, but differences were

only statistically significant for parous women (table 3 J.

Among nulliparous women outcomes for planned home versus

planned hospital births were: severe acute maternal morbidity

adjusted odds ratio 0.77 (95% confidence interval 0.56 to 1.06)

and relative risk reduction 25.7% (95% confidence interval

-0.1 % to 5.3.5%), blood transfusion of four or more packed

cells 0.90 (0.65 to 1.27) and 14.5%' (-14.7% to 45.8%),

postpartum haemorrhage 0.92 (0.85 to 1.00) and 0.5% (-6.8%

to 7.9% ). and manual removal of placenta 0.91 (0.83 to 1.00)

and 2.8% (-6.1%- to 1 1.8% ). Among parous women outcomes

for planned home versus hospital births were: severe acute

maternal morbidity adjusted odds ratio 0.43 (95% confidence

interval 0.29 to 0.63), blood transfusion of four or more packed

cells 0.45 (0.30 to 0.68), postpartum haemorrhage 0.50 (0.46

to 0.55). and manual removal of placenta 0.41 (0.36 to 0.47).

Sensitivity analyses and adjustment for

medical interventions

Sensitivity analyses showed similar results for all outcomes in

table 3 (data not shown). In some of the sensitivity analyses,

differences just reached statistical significance that did not in

the main analyses. For example, for the comparison of severe

acute maternal morbidity, if only women without discrepancies

in onset of labour between the data forms from primary and

secondary care were selected the adjusted odds ratio for planned

home versus planned hospital birth in nulliparous women was

0.63 (95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.88) and in parous

women was 0.46 (0.30 to 0.69). If onset of labour was based on

the national perinatal database-1 form only, the differences in

severe acute maternal morbidity, postpartum haemorrhage, and

manual removal of placenta became significant for nulliparous

women: 0.72 (0.53 to 0.99). 0.90 (0.83 to 0.97). and 0.88 (0.80

to 0.96). respectively.

Fewer women with planned home births compared with planned

hospital births received augmentation of labour (nulliparous

women 22.9%- r 27.5% and parous women 3.4%. v 7.8%;.

respectively) and had an operative delivery (nulliparous women

23.1%. i’ 24.7% and parous women 1.6% v 3.2%. ). The

comparison of severe acute maternal morbidity controlled for

augmentation of labour and operative delivery for planned home

versus planned hospital births among nulliparous women gave

an adjusted odds ratio of 0.80 (0.58 to 1. 10), which is an increase

of 3.9%. in odds ratio. For parous women the adjusted odds ratio

for severe acute maternal morbidity after controlling for these

interventions was 0.47 (0.32 to 0.69). which is an increase of

9.3% in odds ratio.

Discussion

Low risk women in primary care at the onset of labour who

planned to give birth al home had lower rales of severe acute

maternal morbidity, postpartum haemorrhage, and manual

removal of placenta compared with women who planned to give

birth in hospital, but the differences were only statistically

significant for parous women. Odds ratios for severe acute

maternal morbidity changed slightly when we adjusted the

results for medical interventions, and more so for parous than

for nulliparous women.

No commercial reuse. See rights and reprints

Strengths and limitations of this study

A major strength of our study is the large sample size and the

fact that all cases of severe acute maternal morbidity that

occurred in all hospitals in the Netherlands were collected

meticulously over two years. As far as we are aware, this is the

largest study to date into the association between planned place

of birth and severe adverse maternal outcomes.

Our study has some limitations as well. Firstly, because we used

registration data, some were missing or may have been

misclassified. For example, information on the variable “start

of labour in primary or secondary care” was not always

consistent between midwifery and obstetric registration.

However, sensitivity analyses using different definitions of this

variable generated similar results. In addition, 10 101 women

were excluded because their national perinatal database-1 form

was missing when they were referred during labour. Some of

these women were cared for by general practitioners or midwives

who do not participate in the national perinatal registration. In

particular, general practitioners who still practise midwifery are

often located in rural areas. This may explain the higher rate of

parous women and women of Dutch ethnicity among those with

a missing national perinatal database-1 form. For 18 070 women

planned place of birth al the onset of labour was unknown. Their

rate of severe acute maternal morbidity was comparable to that

of women who planned hospital births. Even if all of these

women would have a planned home birth or. alternatively, if

all of them would have a planned hospital birth, the strength of

the associations would have changed but the results would have

been in the same direction.

Secondly we collected the data from 2004 to 2006 and

theoretically midwifery management and women’s

characteristics may have changed. However, we have no reason

to believe that at present planned home birth leads to more

unfavourable maternal outcomes. For example, the percentage

of women with a singleton pregnancy who were older than 35

years only increased from 20.5%; in 2004 to 21.1% in 2006 and

this percentage was 21 A% in 2010." 1 Besides, we controlled

the results for differences in maternal age.

Thirdly, although none of the women who started labour in

primary care should have had an indication for secondary care

according to the obstetric indication list, there may still have

been differences in risk profiles between women who planned

labour at home versus in hospital. We corrected the analyses

for known risk factors, such as maternal age and ethnicity.

Adjusting the results regarding severe acute maternal morbidity

for augmentation of labour and operative delivery only led to a

small reduction in the differences. This means that medical

interventions explain some of the differences in severe acute

maternal morbidity, which is consistent with earlier studies that

showed higher rates of adverse maternal outcomes among

women with medical interventions.1’ I!' 11 However, the fact that

odds ratios for adverse maternal outcomes were much lower for

parous women than for nulliparous women, suggests that other

factors played an important part. Those women who had a

relatively difficult previous birth may have been more likely to

plan a hospital birth next lime, even if there was no official

medical indication. If so, this self selection may have resulted

in better outcomes among women with planned home birth. In

addition, there may have been residual confounding owing to

differences in characteristics that could not be identified. For.

example, we had no information on body mass index. Although

a high body mass index is not an official medium risk indication

according to the obstetric indication list, midwives may have

advised these women to give birth in hospital. They may have

ticked the medium risk box but they could not record body mass

Subscribe:'^

Page 5 of 10

BMJ 2013:346:13263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

1

index as the reason for medium risk in the national perinatal

database-1.11

Nevertheless, our hypothesis that low risk women at the onset

of labour who planned birth at home would have a higher rate

of severe acute maternal morbidity compared with women who

planned birth in hospital was not confirmed. Women with

planned home birth had lower rates of all adverse maternal

outcomes, albeit not significantly so for nulliparous women.

This is consistent with other studies that found lower rates of

maternal morbidity among planned home births.’4 ’22 Concern

about safety is an important reason for women to choose hospital

birth, and even more so for their partners."’ '' They worry

especially about transportation to hospital in case of an

emergency. However, although the referral rate during labour

is high in the Netherlands, only 3A(7< of women are referred for

urgent reasons.’* Our results suggest that planned home birth

for low risk women is not associated with an increased risk of

adverse maternal outcomes despite the possible delay in case

of an emergency. Previous studies have not shown higher risks

of severe adverse perinatal outcomes either for planned home

births compared with planned hospital births in the

Netherlands.'" We should emphasise that our results may only

apply to regions where midwives are well trained to assist

women al home births and where facilities for transfer of care

and transportation in case of emergencies are adequate. In 2009,

82% of women were in hospital within 45 minutes from the

moment a midwife called an ambulance in an emergency

situation.’5 The average time was 35 minutes (standard deviation

12 minutes). Travelling lime Io hospital is important for the

.safely of all births, regardless of planned place of birth. A Dutch

study showed that the incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes

was higher if travel time from home to hospital was more than

20 minutes, but differences were only statistically significant

for women in secondary care at the onset of labour.'''

Planned hospital births are also associated with risks. The rate

of medical interventions is lower for planned home versus

planned hospital births among low risk women: for example,

odds ratios for caesarean section varied between 0.31 and 0.76

in different studies. 1 '' It is important to limit the use of

caesarean section because of its association with various adverse

outcomes at the current birth, and the risk of uterine scar rupture

during the next pregnancy and birth.12 2,12'29 However, again

selection bias may play a part despite all women in these studies

being considered al “low risk.” Although more women with

planned hospital birth may have needed interventions to ensure

a good perinatal outcome, considering the large size of the

differences in the rate of medical interventions between the

groups, it is unlikely that these can be explained by a difference

in risk profile only.

The fact that we did not find higher rates of severe acute

maternal morbidity among planned home births should not lead

to complacency. Every avoidable adverse maternal outcome is

one too many. An audit of maternal morbidity should be used

to learn from every case of severe acute maternal morbidity to

improve care, optimise the risk selection system, and prevent

future severe acute maternal morbidity from happening.’"

We thank the Netherlands perinatal registry for the use of the national

database.

Contributors: AJ conceived the study, wrote the article, and is guarantor

of the study. JMe and AJ conducted the analyses. JMa linked the

datasets. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data, critically

revised earlier drafts of the paper for important intellectual content, and

gave final approval of the version to be published. The researchers had

access to all the research data.

Funding- This study was funded with a career grant (VENI) from ZonMw.

The funder had no role in any aspect of the study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform

disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi._disclosure.pdf (available on

request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from

any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with

any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in

the previous three years: no other relationships or activities that could

appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The ethical committee of VU University Medical Center

confirmed that ethical approval was not necessary for this study

(reference No 11/399).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

2

3

4

5

Our study showed a lower risk of severe acute maternal

morbidity, postpartum haemorrhage, and manual removal of

placenta among low risk women in primary care at the onset of

labour with planned home versus planned hospital births. These

differences were statistically significant for parous women. We

found no evidence that planned home birth among low risk

.

Olsen O. Clausen JA. Planned hospital birth versus planned home birth. Cochrane

Database Syst Kev2012;(9) CD000352.

Birthplace in England Collaborative Group. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned

place ot birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England

national prospective cohort study. BMJ 2011:343:d7400.

De Jonge A, Van der Goes BY. Ravelh AC. Amelink-Verburg MP. Mol BW. Nijhuis JG, et

al. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in a nationwide cohort ot 529,688 low-risk planned

home and hospital births. BJOG 2009:116:1177-84.

Hutton EK. Reitsma AH. Kaufman K. Outcomes associated with planned home and

planned hospital births in low-risk women attended by midwives in Ontario. Canada.

2003-2006: a retrospective cohort study. Birth 2009;36:180-9.

Janssen PA Saxell L. Page LA. Klein MC. Liston RM. Lee SK. Outcomes ol planned

home birth with registered midwile versus planned hospital birth with midwife or physician.

6

CMAJ 2009.181:377-83.

Van der Kooy J. Poeran J. De Graaf JP. Birnie E. Denktass S. Steegers EA, et al. Planned

home compared with planned hospital births in the Netherlands intrapartum and early

7

neonatal death in low-risk pregnancies. Obsrel Gynecol2011;118:1037-46.

Olferhaus P. Rijnders M, De Jonge A. De Miranda E. Planned home compared with

planned hospital births in the Netherlands: intrapartum and early neonatal death in low-risk

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Conclusion

No commercial reuse: See rights and reprints

women leads to an increased risk of severe adverse maternal

outcomes in a maternity care system with well trained midwives

and a good referral and transportation system.

17

18

19

pregnancies. Obstel Gynecol2012; 119(2 Pt 1):387-8.

Davis D. Baddock S. Pairman S. Hunter M, Benn C. Wilson D. et al. Planned place of

birth in New Zealand: does it affect mode ol birth and intervention rates among low-risk

women? Birth 2011 ;38:111-9.

Lindgren HE. Radestad IJ, Christensson K. Hildingsson IM. Outcome of planned home

births compared to hospital births in Sweden between 1992 and 2004. A population-based

register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Stand 2008:87:751-9.

Van Haaien-Ten Haken T. Hendrix M, Nieuwenhuijze M, Bude L. De Vries R. Nijhuis J.

Preferred place of birth: characteristics and motives of low-risk nulliparous women in the

Netherlands. Midwilery 2012:28:609-18.

Christiaens W. Nieuwenhuijze MJ De Vries R. Trends in the medicalisation of childbirth

in Flanders and the Netherlands. Midwilery 2013;29:e1-8.

Zwart JJ. Richters JM. Ory F. De Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW. van Roosmalen J. Severe

maternal morbidity during pregnancy, delivery and puerpenum in the Netherlands: a

nationwide population-based study ol 371.000 pregnancies BJOG 2008:115:842-50.

Obstetric Vademecum. Final report of the Maternity Care Committee of the College of

health insurance companies. [Verloskundig Vademecum. Eindrapport van de Commissie

Verloskunde van het College voor zorgverzekeringenj. De Koninklijke Nederlandse

Orgamsatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV). De Landehjke Huisartsen Verenigmg (LHV).

De Nederlandse Veremging voor Obstetne en Gynaecologie (NVOG). Zorgverzekeraars

Nederland (ZN), Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg, eds. 2003. Diemen.

Slichtmg Perinatale Registratie Nederland. Perinatal Care in the Netherlands 2004

[Perinatale zcrg in Nederland 2004], 2007. Stichling Perinatale Registratie Nederland.

Slichting Perinatale Registratie Nedeiland. Perinatal Care in the Netherlands 2005

[Perinatale Zorg m Nederland 2005]. 2008. Slichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland.

Slicntmg Perinatale Registratie Nederland. Perinatal Care m the Netherlands 2006

[Perinatale zorg in Nederland 2006]. 2008. Slichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland.

Meray N. Reitsma JB. Ravelli AC, Bonsel GJ, Probabilistic record linkage is a valid and

transparent tool to combine databases without a patient identification number. J Clin

Epidemiol 2007:60 883-91.

Kramer MS Dahhou M, Vallerand D, Liston R, Joseph KS. Risk factors for postpartum

hemorrhage: can we explain the recent temporal increase’’ J Obstet Gynaecol Can

2011:33:810-9.

Zwart JJ, Jonkers MD, Richters A, Ory F. Bloemenkamp KW. Duvekot JJ. et al. Ethnic

disparity in severe acute maternal morbidity: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands.

Eur J Public Health 2011:21:229-34

Subscribe:

Page 6 of 10

BMJ 2013:346:13263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

. .

RESEARCH

-i

What is already known on this topic

Low risk women with planned home birth at the onset of labour have lower rates of referral from primary to secondary care during labour,

augmentation, medical pain relief, operative delivery, postpartum haemorrhage, and episiotomy than those with planned hospital birth

Studies so far have been too small to compare severe acute maternal morbidity between planned home birth and planned hospital birth

among low risk women

What this study adds

Low risk women in primary care with planned home birth at the onset of labour had a lower rate of severe acute maternal morbidity,

postpartum haemorrhage, and manual removal of placenta than those with planned hospital birth

These differences were statistically significant for parous women

There was no evidence that planned home birth among low risk women leads to an increased risk of severe adverse maternal outcomes

in a maternity care system with well trained midwives and a good referral and transportation system

20

21

22

23

Van Dillen J. Zwart JJ. Schutte J. Bloemenkamp KW. Van Roosmalen J. Severe acute

maternal morbidity and mode of delivery in the Netherlands. Ada Obstel Gynecol Scand

2010,89.1460-5.

Stichtmg Perinatale Registralie Nederland. Perinatal Care in the Netherlands 2010

|Perinatale Zorg in Nederland 2010|. 2013. Stichting Perinatale Registrat

Blix E. Huitfeldl AS, Oian P, Straume B, Kumle M. Outcomes of planned home births and

planned hospital births in low-risk women in Norway between 1990 and 2007: a

retrospective cohort study. Sex Reprod Healthc 2012:3:147-53.

Bedwell C. Houghion G. Richens Y, Lavender T. She can choose, as long as I m happy

with it: a qualitative study ol expectant fathers views of birth place. Sex Reprod Healthc

24

2011.2'71-75.

Amelink-Verburg MP. Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Hakkenberg RM. Veldhuijzen IM.

Bennebroek GJ. Buitendijk SE. Evaluation of 280,000 cases in Dutch midwifery practices,

25

a descriptive study. BJOG 2008:115:570-8.

Kommer GJ, Zwakhals SLN. Time in ambulance care. Analysis of emergency journeys

in 2009. (Tijdsduren in ambulancezorg. Analyse van spoedinzelten in 2009.]. RIVM, ed.

26

RIVM Briefrapport 270482001/2010. 2010.

Ravelli AC. Jager KJ, De Groot MH. Erwich JJ. Rijninks-van Driel GC, Tromp M. et al.

Travel lime from home to hospital and adverse perinatal outcomes in women al term in

Declercq E. Barger M. Cabral HJ. Evans SR. Kotelchuck M, Simon C. et al. Maternal

outcomes associated with planned primary cesarean births compared with planned vaginal

28

births. Obstel Gynecol2007:109:669-77.

Declercq E. Cunningham DK, Johnson C. Sakala C. Mothers’ reports of postpartum pain

associated with vaginal and cesarean deliveries: results of a national survey. Birth

29

2008:35:16-24.

Fitzpatrick KE. Kurinczuk JJ. Alfirevic Z. Spark P. Brocklehurst P. Knight M. Uterine rupture

by intended mode ol delivery in the UK: a national case-control study. PLoS Med

30

2012;9:e1001184.

Van Dillen J. Mesman JAJM. Zwart JJ. Bloemenkamp KW, Van Roosmalen J. Introducing

maternal morbidity audit in the Netherlands. BJOG 2010:117:416-21.

Ciie this as: WJ2013;346:f3263

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons

Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute,

remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially. and license their derivative works

on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is

non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.Org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/.

the Netherlands. BJOG 2011 ;118:457-65.

No commercial reuse: See rights and reprints :

27

■. ■ r

Subscribe:

•■/ ■■/v/.-; c-ni.orwovz w. !

BMJ 2013;346:f3263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

Page 7 of 10

RESEARCH

Tables

| Characteristics of low risk women in primary care at onset of labour

Characteristics

Total (n=146 752) Planned place of birth at onset of labour

Home (n=92 333)

Hospital (n=54 419)

Parity:

0

65 227 (44.4)

38 728 (41.9)

26 499 (48.7)

It

81 521 (55.6)

53 602 (58.1)

27 919(51.3)

4(0)

Missing data

Gestational age:

5700 (3.9)

3404 (3.7)

2296 (4.2)

38+0 to 40+6

107 763 (73.4)

67 507 (73.1)

40 256 (74.0)

41+0 10 41+6

33 289 (22.7)

21 422 (23.2)

11 867 (21.8)

37+0 to 37+6

Maternal age (years):

<25

18 549 (12.6)

9142 (9.9)

9407(17.3)

25-34

101 691 (69.3)

66 554 (72.1)

35 137 (64.6)

>35

26 498 (18.1)

16 630(18.0)

9868 (18.1)

14(0)

Missing data

Ethnicity:

Dutch

119 755 (82.0)

83 629 (90.9)

36 126 (66.9)

Non-Dutch

26 289 (18.1)

8385 (9.1)

17 904 (33.1)

Missing data

708 (0.5)

Socioeconomic position:

High

35 567 (24.6)

23 243 (25.5)

12 324 (23.0)

Medium

66 419 (45.9)

45 320 (49.7)

21 099 (39.4)

Low

42 861 (29.6)

22 671 (24.8)

20 190 (37.7)

Missing data

1905 (1.3)

For all characteristics P<0.001.

| No commercial reuse: S6e rights and reprints http.■Avww.i.ytij eom/permissiOfis

Subscribe: htip-Vwwwbmi.convstJbscritHn

Page 8 of 10

BMJ 2013:346:13263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

•_

| Severe acute maternal morbidity, postpartum haemorrhage, and manual removal of placenta in low risk births starting in primary

care: total group

No with outcome (No/1000 women)

Outcomes

Total (0=146 752)

Planned home birth (n=92 333) Planned hospital birth (n=54 419)

Severe acute maternal morbidity

288 (2.0)

141 (1.5)

147(2.7)

Admission to intensive care unit

70 (0.5)

32 (0.3)

38 (0.7)

19 (0.1)

8(0.1)

11 (0.2)

Eclampsia or severe HELLP syndrome

Blood transfusion >4 packed cells

256(1.7)

134 (1.5)

122 (2.2)

Postpartum haemorrhage (>1000 mL)

4871 (33.2)

2699 (29.2)

2172 (39.9)

2865 (19.5)

1550(16.8)

1315 (24.2)

Manual removal ol placenta

HELLP=haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count.

Missing data: postpartum haemorrhage 1234 (0.8%), manual removal ot placenta 2106 (1.4%).

Women could have more than one type of severe acute maternal morbidity.

No commercial reuse See rights and reprints

Subscribe:

Page 9 of 10

BM/2013;346:f3?.63 doi: 10.1136/bmj.13263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

| Severe acute maternal morbidity, postpartum haemorrhage, and manual removal of placenta among low risk nulliparous and

parous women starting labour in primary care

Nulliparous women (n=65 227)

Variables

Parous women (n=81 521)

Planned home birth (n=53 602)

Planned hospital birth

(n=27 919)

Planned home birth (n=38 728

Planned hospital birth

(n=26 499)

89 (2.3)

82 (3.1)

52(1.0)

65 (2.3)

Reference

Severe acute maternal morbidity:

No (No/1000)

Crude odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.74 (0.55 to 1.00)

Reference

0.42 (0.29 to 0.60)

Adjusted odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.77 (0.56 to 1.06)

Reference

0.43 (0.29 to 0.63)

Reference

25.7 (-0.1 to 53.5)

Reference

58.3 (33.2 to 87.5)

Reference

85 (2.2)

68 (2.6)

49 (0.9)

54 (1.9)

Reference

Relative risk reduction (%. 95% Cl)

Blood transfusion >4 packed cells:

No (No/1000)

Crude odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.86 (0.62 to 1.18)

Reference

0.47 (0.32 to 0.70)

Adjusted odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.90 (0.65 to 1.27)

Reference

0.45 (0.30 to 0.68)

Reference

Relative risk reduction (%. 95% Cl)

14.5 ( 14.7 to 45.8)

Reference

52.7 (24.9 to 85.3)

Reference

Postpartum haemorrhage:

1655 (43.1)

1134 (43.3)

1044 (19.6)

1038 (37.6)

Crude odds ratio (95% Cl)

1.0 (0.92 to 1.07)

Reference

0.51 (0.47 to 0.56)

Reference

Adjusted odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.92 (0.85 to 1.00)

Reference

0.50 (0.46 to 0.55)

Reference

Relative risk reduction (%. 95% Cl)

0.5 (-6.8 to 7.9)

Reference

47.9 (41.2 to 54.7)

Reference

1099 (29.0)

773 (29.8)

451 (8.5)

542(19.6)

Crude odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.97 (0.89 to 1.07)

Reference

0.43 (0.38 to 0.48)

Reference

Adjusted odds ratio (95% Cl)

0.91 (0.83 to 1.00)

Reference

0.41 (0.36 to 0.47)

Reference

Relative risk reduction (%. 95% Cl)

2.8 (-6.1 to 11.8)

Reference

56.9 (47.9 to 66.3)

Reference

No (No/1000)

Manual removal of placenta:

No (No/1000)

Adjusted relative risks adjusted for variables in table 1.

No commercial reuse: See rights and reprints

Subscribe:

• fx I

Page 10 of 10

I3MJ 2013,346:13263 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3263 (Published 13 June 2013)

RESEARCH

Figure

National perinatal register data

Singleton pregnancies, spontaneous onset of labour

from 37 to 42 weeks' gestation without

history of caesarean section (n-240 400)

LEMMoN data

Singleton pregnancies, spontaneous onset of labour, and severe

acute maternal morbidity (SAMM) after onset of labour

from 37 to 42 weeks' gestation without history of

caesarean section (n>=706; 27.7% of total LEMMoN cases)

b

LEMMoN cases not linked to

perinatal register data (n=56; 7.9%)

I....

Linked data total (n-240 400), SAMM (n-650; 2.7/1000)

Primary care form missing for women referred during labour (n”10 101; 4.2%), SAMM (n“52; 5.1/10OO)

Eligible women (n»23O 299), SAMM (n-598; 2.6/1000)

Primary care at onset of labour

(n=172 973), SAMM (n-364; 2.1/1000)

Secondary care at onset of labour

(n=56 887), SAMM (n=233; 4.1/1000)

Unknown level of care at start of labour

(n=439), SAMM (n«l; 2.3/1000)

Excluded (n-26 221; 15.2%), SAMM (n-76; 2.9/1000):

Planned place of birth unknown (n»18 070), SAMM (n»=46; 2.5/1000)

Medium risk at onset of labour (n»2112), SAMM (n-10; 4.7/1000)

Prolonged ruptured membranes, no contractions (n=6039). SAMM (n=20; 3.3/1000)

Total for comparison within primary care (n-146 752), SAMM (n-288; 2,0/1000)

---------------------------J--------------------------- }

Planned home at onset of labour (n-92 333; 62.9%),

SAMM(n«141; 1.5/1000)

Planned low risk hospital at onset of labour (n-54 419; 37.1%),

SAMM (n”147; 2.7/1000)

Flow of births between August 2004 and July 2006

No commercial reuse See righls and reprints

p

Subscribe:

‘'

Policy Recommendations for Maternal Health in India

The Delhi statement

Context of maternal health and maternal mortality in India

Maternal mortality continues to be an unjustifiably significant problem in India in spite of the issue garnering a

lot of attention and being the focus of policy and programme by the Government of India and international

bodies. Health activists have been feeling increasingly dissatisfied with the maternal health care situation on the

ground in India. Many women continue to die around child birth because health facilities in many parts of the

country are not equipped to provide Emergency Obstetric Care, the quality of antenatal care provided is

inadequate, and safe abortion services in the public sector are inaccessible for the majority of women.

Government reports, however, project that the maternal health situation is improving mainly because the Janani

Suraksha Yojana disbursements are increasing.

We believe that women have the right to the highest attainable standards of maternal health and

maternal health care. Maternal health services have to be available, accessible, acceptable, and of good

quality. While motherhood is often a positive and fulfilling experience, for too many women it is associated with

suffering, ill-health and even death.

The approach to addressing maternal health in India is fragmented and focused on promoting institutional

deliveries alone, while overlooking the broader framework of sexual and reproductive rights. The maternal

health policy in India needs to move away from the paradigm of institutional deliveries to a paradigm of safe

deliveries. Several issues that affect maternal health - such as access to safe abortion services, access to choice of

contraception, dignified childbirth, poverty, nutrition remain blind spots in policy.

Similarly, gender based violence is a crucial factor that has major health implications and even death. This is the

result of physical injuries and also of barriers created by domestic violence to women seeking appropriate care

during pregnancy and delivery. The situation is exacerbated by the state’s regressive demographic goals and

coercive population policies that have dictated health policies and programmes for women especially in terms of

financingand resource allocation. There is enough evidence to suggest that attention to ante natal and postnatal

care has suffered because ofthe priority accorded to the family planning programme in the country.

Thus, the solutions proposed often fail to capture or be relevant to the lived realities of women. Approaches to

reduction of maternal mortality have for too long been driven by experts, funders and international bilateral

organizations, with the voices of the women of India and the activists working among them, hardly ever being

included in policy and programme planning. Maternal mortality reduction strategies have been target oriented

and treat maternal mortality as a simple input - output problem. In the pastyear or so, there have been a number

of documentations of maternal deaths by civil society groups from different parts of India including from the so

called ’developed' states like Tamilnadu, Karnataka and Kerala. All of these reports bring out the inadequacy of

purely technical and narrow indicator-oriented approaches, without concurrent attention to the social

determinants, health systems and other broader aspects surrounding these deaths.

While Maternal Death Reviews are mandated and are being done in several states, many maternal deaths still fail

to get reported, especially those that occur outside hospital settings. There is no public disclosure of the analysis

of maternal deaths, or of the measures planned to address the causes of maternal deaths. Neither is there an

1

■ ■

accurate and disaggregated database from which the especially vulnerable groups can be identified.

In order to focus more political attention to maternal health in the country and to suggest recommendations for

policy and programmes, a group of public health specialists and civil society activists from different networks

and organizations including CommonHealth, NAMHHRand Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, SAMA, CEHAT, SOCHARA and

SAHA) met in Delhi on the 12th and 13th August, 2013. The meeting saw the participation of nearly forty persons

working closely at the grassroots on issues related to maternal health. On the second day, Dr Syeda Hameed,

Member, Planning Commission and Mr Keshav Desiraju, Secretary, MoHFW, interacted with civil society

members at a policy dialogue session. The sessions saw several concerns and recommendations emerging from

the consultation.

Ourconcerns

•

In spite of the fact that the poorest and most vulnerable women are the most affected, the government

has fallen short in addressing maternal health with a comprehensive strategy and being accountable for

it.

•

Maternal Death Reviews, though mandated since 2010, have not been institutionalised in many districts

across various states, and are notbeing carried out in several communities, especially in rural areas.

•

Even where maternal death reporting and reviews are being done, this information is not available in the

public domain so as to ensure transparency and accountability of the process.

• Important social determinants like poverty, caste and gender including violence against women that

have been shown repeatedly by civil society documentations to be intimately related to maternal health

and maternal mortality, are not being addressed in any manner by existing programmes.

• There is a lack of institutionalized systems of accountability to the community in the health system

including for critical issues like maternal mortality.

• Undignified treatment of women, especially those from marginalized communities, during childbirth

has been reported from various parts of the country, but is not acknowledged as a problem. Women

report facing physical abuse and verbal abuse, particularly use of derogatory, sexually explicit language.

This makes them reluctantto use public health facilities thus impacting access.

• Gender based violence, including domestic violence, which is known to have an impact

impact on

on women's

women s

control over their fertility, as well as pre and post partum health of mothers is not even addressed as an

issue of concern.

• Unsafe abortion which is a major cause of maternal mortality is not adequately addressed in maternal

health programmes.

Key Recommendations

/

In spite of the increase in the number of institutional deliveries in recent years, quality of care remains a

serious concern. Marginalized women from vulnerable caste groups and geographically remote areas

continue to be excluded from programmes. Therefore, we recommend that

• Ensuring SAFETY must be the priority in ALL deliveries irrespective of where they occur and who

conducts them.

2

11

I

•

Outcome indicators should go beyond JSY disbursements and number of institutional deliveries to

include indicators of Safety such as, completeness of antenatal care, technical aspects of care like

Active Management of Third Stage of Labour and provision of postpartum care.

•

Blood availability continues to be an important issue. Blood storage units should be operationalized at

every FRU.

• Referrals are often done unnecessarily and to facilities that do not have the capacity to manage specific

complications. Availability of emergency transport during such referrals is also an important issue.

Accountability during referrals must be ensured and continuity of care provided during transit between

facilities during referrals. Ensuring that women are accompanied by appropriately trained health

personnel during such referrals, providing free emergency transport, and instituting audits of referral

protocols and outcomes are some mechanisms to ensure accountability duringreferrals.

• Verbal and physical abuse by health care providers, during labour in public health facilities must be

stopped and action taken against health care providers who indulge in it. Mechanisms to address

grievances particularly related to abuse must be put in place in health systems.

/

Policies and programmes must respond to women's needs that go beyond quality health care during

pregnancy, delivery and post partum period to include nutrition, contraception, access to safe abortion,

freedom from violence, dignity during care and access to information and care, from adolescence

throughouttheir life span.

•

Documentations of maternal deaths show that non-obstetric causes are becoming an important

contributor to maternal deaths. Services for tuberculosis, malaria and rheumatic heart disease

during pregnancy must be strengthened and integrated with existing vertical programmes for

these diseases.

• Availability and access to abortion services in the public health sector need to be ensured.

Information on number of abortion services provided in public sector facilities should be collected and

analysed.

/

Policies and programmes need to be more nuanced and tailored to the needs of women in different

situations.

•

For instance, screening for sickle cell anaemia in tribal populations, bed nets and malaria

prophylaxis in malaria endemic areas.

•

Maternal health care needs to be placed in the context of all-round strengthening of health systems.

•

Maternal health care can be strengthened only within a functioning primary health care system and

Universal Access to Health Care that is publicly provisioned and tax-financed.

• While the Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram is a step towards Universal Maternity Care, this should

be monitored rigorously both from within the system and through communities to ensure that no out

ofpocket expenditures are being incurred.

/

Maternal health is dependant on a range of social determinants like nutrition, gender, poverty, caste,

religion.

3

I

•

Needs of pregnant women should be prioritized in all social welfare programmes at all levels. (For

example, adding maternity benefits in NREGA)

• Specific interventions like one fresh cooked meal women in pregnancy and during lactation as

demonstrated in Andhra Pradesh should be implemented.

• Screening of gender based violence during pregnancy should become an integral part of antenatal

care.

/

The state has to be accountable for ensuring the health of every woman during pregnancy and delivery

including access to safe abortion services if necessary.

• Ensure social audits including provision of resources and setting up mechanisms.

• Quality of care in the private sector needs to be monitored and regulated.

•

Make Maternal Death Reviews transparent and accountable. Strengthen reporting systems for

maternal deaths by including reporting from persons outside the health system like Anganwadi

workers, teachers, PRI members and self help group members.

—

Broaden district and state MDR committees to include civil society representatives, PRIs and

independenttechnical experts.

-

Include private sector deaths in MDR

Consolidated reports of MDRs should be made public with details of actions recommended and

taken.

Tools should be modified to include better evidence for technical details and also social

determinants.

• Ensure grievance redress mechanisms, including immediate response systems and district level

ombudspersons.

This statement is an outcome ofdiscussions during the National Consultation on Maternal Health in India,

held in Delhi on August 12 and 13,2013 organized by the undersigned organizations.

CommonHealth

Coalition for Maternal-Neonatal Health and Safe Abortion

www.commonhealth.in

Alt

People's Health Movement

JSA

Sama

NAMHHR

Date of Publication July 2014

4

building community health

Iv>

(

01 032 ch26.qxd 05/24/2005 18:05 Page 1

*

Chapter 26

Maternal and Perinatal Conditions

Wendy J. Graham, John Cairns, Sohinee Bhattacharya. Colin H W

Bullough. Zahidul Quayyum. and Khama Rogo

The Millennium Declaration includes two goals directly rele

vant to maternal and perinatal conditions: reducing child mor

tality and improving maternal health. The fact that two out of

the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are exclu

sively targeted at mothers and children is testament to the sig

nificant proportion of the global burden of disease they suffer

and to the huge inequities within and between countries in the

magnitude of their burden. Achieving these goals is inextrica

bly linked at the biological, intervention, and service delivery

levels (Bale and others 2003).

*

Maternal and child health services have long been seen as

inseparable partners, although.over the past 20 years the rela

tiveemphasis within each, particularly at a policy level, has var

ied (De Brouwere and Van Lerberghe 2001). The launch of the

Safe Motherhood Initiative in the late 1980s, for example,

brought heightened attention to maternal mortality, whereas

the Internauona! Conference Qn Population and Development'

CPD) broadened the focus to reproductive health and, more

recently, to reproductive rights (Germain 2000). Those shifts

can be linked with international programmatic responses and

erminology—with the preventive emphasis of, for instance,

prenatal care being lowered as a priority relative to the treat

ment focus of emergency obstetric care. For the child, inte

tanagement of

of childhood

childhood illnesses

has bro.wht

grated management

”

renewed eimphasis to maintaining a balance between preventive

and curative

ive care. The particular needs of the newborn how

ever, have only started

past three or four years (Foege 2001).

Although health experts agree that the single clinical inter

vent,ons needed to avert much of the burden of maternal and

perinatal death and disability are known, they also accept that

these interventions require a functioning health system to have

an effect at the population level. Levels of maternal and perina

tal mortality are thus regarded as sensitive indicators of the

entire health system (Goodburn and Campbell 2001), and they

can therefore be used to monitor progress in health gains more

generally. What is also clear is that maternal mortality and the

neonatal component of child mortality continue to represent

two of the most serious challenges to the attainment of the

MDGs, particularly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

An estimated 210 million women become pregnant each

year, and close to 60 million of these pregnancies end with the

death of the mother (500,000) or the baby or as abortions.

I his chapter focuses on the adverse events of pregnancy and

childbirth and on the intervention strategies to eliminate and

ameliorate this burden.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MATERNAL

AND PERINATAL CONDITIONS

Much has been written about the lack of reliable data on

and perinatal conditions in developing countries

,

J2003’('rah;'m 200TSave the Children 2001). Weak

rdi- "'e ‘"f0"™'1™ ’yStems’ inadeq“a<e vital registration, and

non, I r-0"

10USCl,°ld SUrveys as ,he main

of

Recognizing the implications of these obstacles for prioritizing

health needs and interventions is important and is now

endorsed by a global movement toward evidence-based deci

sion making for policy and practice (Evansand Stansfield 2003)

I

I

'..••P 001 -032 ch26.qxd 05/24/2005