RF_WH_2_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_WH_2_SUDHA

ARTICLES

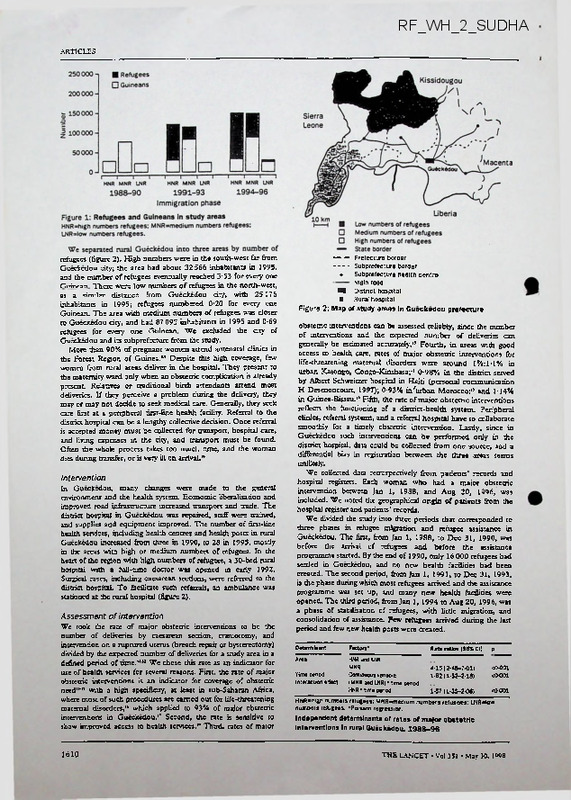

refugees (figure 2). High numbers were in the south-west far from

Gueckedou dry, the area had about 32 566 inhabitants in 1995,

and the number of refugees eventually reached 3-53 for every one

Guinean There were low numbers of refugees in the north-west,

at a similar distance from Gueckedou dty, with 25176

inhabitants in 1995; refugees numbered 0'20 for every one

Guinean. The area with medium numbers of refugees was closer

to Gueckedou dty, and had 87 095 inhabitants in 1995 and 0*69

refugees for every one Gninran We excluded the dty of

Gueckedou and its subprefecture from the study.

More than 90% of pregnant women attend antenatal clinics in

the Forest Region of Guinea.” Despite this high coverage, few

women from rural areas deliver in rhe hospital. They present to

the maternity ward only when an obstetric complication is already

present. Relatives or traditional birth attendants attend most

deliveries. If ±ey peredve a problem during the delivery, they

may or may not dedde to seek medical care. Generally, they seek

care first at a peripheral first-line health facility. Referral to the

district hospital can be a lengthy collective decision. Once referral

is accepted money must be collected for transport, hospital care,

and living expenses in the dty, and transport must be found.

Often the whole process takes too much time, and the woman

dies during transfer, or is very ill on arrival. '•

Intervention

In Gueckedou, many changes were made to the genera!

environment and the health system. Economic liberalisation and

improved road infrastructure increased transport and trade. The

district hospital in Gueckedou was repaired, staff were trained,

and supplies and equipment improved. The number of first-line

health services, induding health centres and health posts in rural

Gueckedou increased from three in 1990, to 28 in 1995, mosdy

in the areas with high or medium numbers of refugees. In the

heart of the region with high numbers of refugees, a 30-bed rural

hospital with a full-time doctor was opened in early 1992.

Surgical cases, including caesarean sections, were referred to the

district hospital. To facilitate such referrals, an ambulance was

stadoned at the rural hospital (figure 2).

Assessment of intervention

We took the rate of major obstetric interventions to be the

number of deliveries by caesarean section, craniotomy, and

intervendon on a ruptured uterus (breach repair or hysterectomy)

divided by the expected number of deliveries for a study area in a

defined period of time."” We chose this rate as an indicator for

use of health services for several reasons. First, the rate of major

obstetric intervendons is an indicator for coverage of obstetric

need”"’ with a high specificity, at least in sub-Saharan Africa,

where most of such procedures are carried out for life-threatening

maternal disorders,•• which applied to 93% of major obstetric

interventions in Gueckedou." Second, the rate is sensitive to

show improved access to health services.’’ Third, rates of major

1610

------ Prefecture border

------ Subprefecture border

•

Subprefecture health centre

1

Main road

■I District hospital

■ Rural hospital

Figure 2: Map of study areas In Gueckedou prefecture

obstetric interventions can be assessed reliably, since the number

of interventions and the expected number of deliveries can

generally be estimated accurately.'’ Fourth, in areas with good

access to health care, rates of major obstetric interventions for

life-threatening maternal disorders were around 1%:1-1% in

urban Kasongo, Congo-Kinshasa;" 0-98% in the district served

by Albert Schweitzer hospital in Haiti (personal communication

H Desenoncourt, 1997); 0-93% in'urban Morocco;” and 1-14%

in Guinea-Bissau.” Fifth, the rate of major obstetric interventions

reflects the functioning of a district-health system. Peripheral

clinics, referral systems, and a referral hospital have to collaborate

smoothly for a timely obstetric intervention. Lastly, since in

Gueckedou such interventions can be performed only in the

district hospital, data could be collected from one source, and a

differential bias in registration between the three areas seems

unlikely.

We collected data retrospectively from patients’ records and

hospital registers. Each woman who had a major obstetric

intervention between Jan 1, 1988, and Aug 20, 1996, was

included. We noted the geographical origin of patients from the

hospital register and patients ’ records.

We divided the study into three periods that corresponded to

three phases in refugee migration and refugee assistance in

Gueckedou. The first, from Jan 1, 1988, to Dec 31, 1990, was

before the arrival of refugees and before the assistance

programme started. By the end of 1990, only 16 000 refugees had

settled in Gueckedou, and no new health facilities had been

created. The second period, from Jan 1, 1991, to Dec 31, 1993,

is the phase during which most refugees arrived and the assistance

programme was set up, and many new health facilities were

opened. The third period, from Jan 1, 1994 to Aug 20, 1996, was

a phase of stabilisation of refugees, with little migration, and

consolidation of assistance. Few refugees arrived during the last

period and few new health posts were created.

D®t®rmln«nt

Factors’

Rat® ratios (95% Cl)

P____

Area

HNR ano LNR

MNR

Continuous variable

(MNR ano LNR)* time period

HNR" time oenod

4-15 (2-46-7-01)

1-82(1-52-2-18)

<0-C01

<0-001

Tim® period

interaction effect

<0001

1-67 (1-35-2-06)

HNR»high numbers refugees: MNR-medium numbers refugees: LNR« low

numbers refugees. •Poisson regression.

Independent detennlnants of rates of major obstetric

Interventions In rural Gueckedou. 198S-96

THE LANCET • Vol 351 • May 30. I»«8

ARTICLES

with medium numbers of refugees had initially higher

rates of major obstetric interventions than the areas with

low and high numbers, the presence of refugees and the

refugee-assistance programme were associated with a

significantly greater increase in intervention rates in the

area with high numbers of refugees compared with rhe

two areas with lower numbers of refugees.

Discussion

M*°r

I

36

2

oostetrie

interventions (01

Exoected 3904 10442 3018

deliveries (n)

13

48

5

4143 11081 3203

41

95

8

3852 10303 2978

Immigration phase

Figure 3: Rates (95% Cl) of major obstetric Interventions by

study area and period

HNRshigh numoers refugees: MNR=madium numbers refugees:

LNRsHow numbers refugees.

Statistical analyses

Since major obstetric interventions can be assumed to be

distributed as a Poisson event, we calculated Poisson confidence

intervals (95%) for rates, and used Poisson regression analysis to

estimate the trend over time in each area. We estimated rate

ratios for the three areas, comparing each time-period with the

previous one. To test the hypothesis of the equality over time in

the different areas, we included the main effects of time and area

in the model, together with an interaction term (time' area).

Results

During the study period, 981 major obstetric interventions

were performed in Gueckedou hospital. Interventions on

464 urban residents, 249 refugees, and 19 women from

outside the prefecture were excluded from analysis. For

1994-96, rates of major obstetric interventions for

refugees in rural areas of Gueckedou were estimated at

0-83%. These were not further analysed.

We analysed 249 major obstetric interventions carried

out on Guinean women living in rural Gueckedou (figure

3). During 1988-90, before the arrival of the refugees,

intervention rates were very low in all rural areas. After the

refugees arrived, the rates of major obstetric interventions

.rose from 0-03% (95% CI 0-0-09) to 1-06% (0-74-1-38)

’in the area with high numbers of refugees, from 0-34%

(0-22-0-45) to 0-92% (0-74-1-11) in the area with

medium numbers, and from 0-07% (0-0-17) to 0-27%

(0-08-0-46) in the area with low numbers. The estimated

rate ratios over time were 4-35 (2-64-7-15) for the area

with high numbers of refugees, 1-94 (0-97-3-87) for the

area with low numbers, and 1-70 (1-40-2-07) for the area

with medium numbers of refugees.

In a Poisson regression analysis (table), a model that

included time and the area with medium numbers of

refugees as main effects and a term for the interaction

between time and area (high numbers vs medium and low

numbers) provided the best fit (goodness of fit x:=7-22 for

five degrees of freedom). The area with medium numbers

had an independent effect on intervention rate, and there

was an overall time trend. Most importantly, there was a

significant interaction with time for areas with low and

medium numbers compared with the area with high

numbers, in which the effect on the rate of major obstetric

interventions over time was significantly greater than the

base rate (rate ratio 167 [1-35-2-06]). Although the area

THE LANCET - Vol 351 • May 30, 1998

Our data show that the use of referral health services by

the rural population of Gueckedou increased substantially

over time. The only obvious difference between the areas

with high and low numbers of refugees was ±e impact of

the refugees and the refugee assistance programme.

It seems unlikely that bias could explain the differences

we found. We tried to avoid misclassification of refugees

as Guineans, although some Guineans may have

registered falsely as refiigees to obtain free medical care.

Such misclassification, if it occurred, was, however, more

likely in the area with many refugees than in areas with

lower numbers of refugees. False refugees would thus

lower the observed increase in intervention rates for

Guineans in the area with many refugees.

During the study period, independent of the refugees

and the refugee-assistance programme, important changes

took place in the Gueckedou health system and in the

general environment. These changes decreased certain

obstacles to timely obstetric care. The Guinean Ministry

of Health and the German Development Cooperation

have improved the quality of care and the financial

accessibility at the hospital of Gueckedou, and have

developed a network of first-line health services in the

prefecture.

During

the

same

period,

economic

liberalisation resulted in more access to money and higher

availability of transport. These changes could have

improved the access to the hospital, and may explain why

the rate of major obstetric interventions increased in all

study areas, including the area with low numbers of

refugees in which the impact of the refugee-assistance

programme was weak.

The presence of many refugees in certain areas of

Gueckedou has, however, led to additional social and

economic changes. First, economic changes have been

more important in the refugee-affected areas. The

presence of and assistance to refugees has transformed the

economy in remote rural areas. The presence of freely

settled refugees meant cheap labour and increased

exploitation of agricultural resources. Relief food was

sometimes resold’, which substandally increased trade and

circulation of money in the area. Some Guineans

registered as refugees and obtained free food, and,

therefore, economic assets. Agencies assisting the refugees

employed hundreds of staff, which introduced more

money into the local economy. These changes may have

enabled better access to cash for the Guinean rural

population of the refugee-affected areas. Patients

commonly mention lack of access to money as the main

constraint when seeking emergency medical care.

Second, transport infrastructure was substantially

improved. Roads and bridges were repaired, mainly to

allow food aid to be transported to the refugee

settlements. Consequently, many more cars arrived in the

area. The ambulance permanently stationed at the rural

hospital in the area with many refugees undoubtedly

facilitated referral to the district hospital in Gueckedou

1611

ARncu-s

and decreased the need for money. The ambulance was

free of charge for refugees and Guineans. Since the

ambulance started operating in 1992, it transported most

of the obstetric emergencies to the district hospital. Efforts

to improve the road infrastructure were also made in the

area with low numbers of refugees, but much less was

achieved than in the area with high numbers.

Third, there was probably a “refugee-induced demand”

for health care. Before the war, health services in Liberia

and Sierra Leone were better and more advanced than in

Guinea, and the population used them more often. When

confronted with a serious disorder, therefore, refugees

living in close contact with the Guineans may have

encouraged them to use the health services.

Lastly, more health services were developed in the areas

into which refugees moved. When the first refugees

arrived, serious efforts to upgrade first-line and secondline health services, were underway in Guinea, based on

cost-recovery schemes.” Between 1988 and 1995, a health

centre was opened in most sub-prefectures of Guinea. In

the refugee-affected areas this process was faster and more

widespread. Full coverage with health centres was already

achieved in 1992, and many additional health posts'were

created.

Rates of major obstetric interventions in the area with

high numbers of refugees were still low in 1991-93, and

die changes took several years to become effective. This

delay probably shows that there is an important time lag

between the introduction of improvements in the health

system, and increased use by people living in remote rural

villages.

The greater increase in rates of major obstetric

interventions in the area with many refugees than in the

other two areas is probably because of the more intensive

refugee assistance programme and the presence of

refugees. We could not identify fully, however, what part

each of these factors played, nor whether we identified all

important factors. The combination of factors probably

contributed to the increased use of referral health services

by the host population. The changes that were introduced,

however, decreased only partly the obstacles to timely

obstetric care. Rural people still face important financial,

logistic, and cultural barriers to such care. Efforts are

being made in Gueckedou prefecture to set up small-scale

health-insurance schemes to overcome these barriers.

None of the changes made in the refugee-affected areas

was specific for obstetric interventions. All health services

were general and the ambulance transported any patient

referred to the hospital. Therefore, access probably

improved for all disorders, not only for obstetric care.

The approach to refugees in Guinea made this positive

effect on the host population possible. Refugee assistance

followed the refugees to where they settled and supported

the refugees* own coping mechanisms. Several factors

were favourable to such a non-directive approach to

refugee settlement and assistance. The refugees arrived

gradually, in several waves, and were spread over a large

area. The administrative and health authorities were not

therefore, overwhelmed by the influx. Moreover, many

refugees were culturally related to the host population in

Guinea, with whom they had had contacts before arrival.

This cultural proximity facilitated assistance by the host

population. With between 15 and 20 inhabitants per km3

the Forest Region of Guinea is not densely populated and

has a relative abundance of underused agricultural

resources. The population is generally positive towards

1612

strangers, who are perceived as an economic asset for

villages.” The refugee-affected areas were also far from the

capital, Conakry, and the refugees were not thought to be

a threat to national security by the government of Guinea.

At the time of the refugees’ arrival the conditions

prevailing in the health system were favourable to an

integrated approach to refugee assistance. In most districts

the Ministry of Health had launched new integrated

health centres and was upgrading the hospital. With stocks

of drugs and medical equipment readily available locally,

new health facilities modelled on the national health policy

could be created overnight. Medecins Sans Frontieres was

assisting the Ministry of Health in this development of

health facilities in the Forest Region before the arrival of

the refugees. The two organisations were, therefore, able

to put a refugee-assistance programme together, which

may have contributed to the local and national impression

of control of the influx. Indeed, all medical refugee

assistance was organised by the Ministry of Health and

Medecins Sans Frontieres, in collaboration with the other

foreign health agencies already working in the Region. No

new health agencies brought relief during the first years of

the refugee influx. During the first months, the

operational role of UNHCR was limiter! The agencies

present agreed that medical assistance to refugees should

respect the overall policy of the Ministry of Health to

avoid negative impact on the changing and still fragile

national health system. Resources that became available

through the refugee-assistance programme were partly

invested to reinforce the overall health system.

The situation of the refugees in Guinea was, therefore

different from that for many refugees, who generally arrive

more quickly in larger numbers.” During such acute

refugee emergencies, most attention is focused on

decreasing the burden of the acute health crisis faced by

the refugees. The scope of the crisis and the urgency of

the necessary measures commonly mean that parallel

refugee health services are organised by foreign relief

agencies to deliver a standard package of emergency-relief

measures. The relief is generally well managed by relief

agencies” and has probably decreased death rates,” but

logistic and military constraints might prevent timely

implementation. Unfortunately, this relief approach is

commonly perpetuated beyond the acute rmergmry,

especially when refugees have been housed in rampo 7 The

effects on the health services of the host country, which

does not have enough resources to cope, are often

negative’ and all relief resources are used exclusively by

the refugee health services. Relief organisations often

recruit medical staff from the host country, which can

hamper the functioning of the health services in countries

with scarcity of such staff? The health authorities that are

supposed to coordinate relief measures in their area can be

overwhelmed by new relief actors, further weakening the

local health services. The host population may not be able

to use the refugee health services, even if they are better

staffed, equipped, and supplied than those of the host

country. The quality of care available to the host

population may, therefore, decrease as a consequence of

the assistance to refugees.

In other countries, conditions for an integrated

approach to refugee assistance may be less favourable.

However, the positive effects for the host population

documented in Guinea show that it might be worthwhile

for host governments to consider such an approach

whenever possible. Relief agencies involved should adapt

THE LANCET • Vol 351 • May 30, 1W8

ARTICLES

intervention methods accordingly. An integrated approach

to refugee assistance is probably also more cost-effective.

In Guinea, the overall yearly cost of medical assistance to

refugees was estimated at US$4 per refugee.7 This cost is

much lower than the yearly cost of medical services in

refugee camps—often USS20 per refugee.

The improved access to health care for the host

population in our study should not give the impression

that the refugee influx and the way it was dealt with was

always beneficial to the host population. The refugees and

the refugee-assistance programme in Guinea caused

substantial social and economic changes. The absorption

of such a large population increase in a rural area may also

have had important consequences on the ecological

equilibrium. These changes may jeopardise the long-term

livelihoods of certain strata of the population. The poorest

of the host population may be the worst affected by

changes to the economy.24 Labour opportunities may be

lost because of the presence of cheap refugee labour, and

increases in market prices and increased monetarisation of

the economy may decrease their purchasing power.

Although there are no data to support this hypothesis in

Guinea, the benefits of better access to necessary hospital

^mre may have favoured only Guineans who also benefited

Wm economic change.

A non-directive approach to refugees has the potential

to avoid the negative impact of emergency refugee relief

on the health services of the host country, and to improve

access to health care for the host population. Which

conditions enable such approach and appropriate

intervention methods should be studied in other refugeeaffected areas.

Contributors

AU investigators contributed to the study design, data analysis, and revision

of the manuscript. Vincent De Brouwere and Wim Van Lerberghe had

previous experience of the methods. Wim Van Damme collected data in

Guinea as part ofhis doctorate study on refugee health care in sub-Saharan

Africa.

A cknowledgments

We thank M L Yansane, D Fassa, K Marah, and D Diallo of the Ministry

of Health in Gueckedou, Guinea, and B Verbruggen and G Mirhanx of

Midedns Sans Fronderes in Guinea for their collaboration during the field

work; C Ronsmans and P Van der Scuyft for assistance with the Poisson

analysis, R Ecckels for useful comments on previous drafts. The study was

supported by a research grant from the Fund for Scientific Research,

Flanders, Belgium (FWO-S 2/5-KV-E95), and from the European Union

(IC18-CT96-0113).

1 Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. Prevention of excess mortality in refugee and

displaced populations in developing countries. JAMA 1990; 263:

3296-302.

2 Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. Refugees and displaced persons. War, hunger,

and public health. JAMA 1993; 270: 600-05.

THE LANCET • Vol 351 • May 30, 1998

Porignon D, Notennan JP, Hennan P, Tonglet R, Soron'gane EM,

Lokombc TE. The role of the Zairian health services in the Rwandan

refugee crisis. Disasters 1995; 19: 356-60.

Collins S. Ignoring the host: the impact of recent refugee crises on

health infrastructure in Ngara district, Tanzania. Amsterdam:

Medecins Sans Frontieres 1996: 1-89.

5

Goyens P, Porignon D, Soron’gane EM, Tonglet R, Herman P,

Vis HL. Humanitarian aid and health services in Eastern Kivu, Zaire:

collaboration or competition? J Refugee Stud 1996; 9: 268-80.

6

Van Damme W, Drame ML, Yansane ML, Boelaert M,

Van Hauwaert W, Verbruggen B. Le role des services de same du pays

d’accueil dans la prise en charge des refugjes: 1’experience de la Guinee.

Dev Same 1997; 127:23-27.

7

Van Damme W. Do refugees belong in camps? Experiences from

Goma and Guinea. Lancet 1995; 346: 360-62.

8

Yansane ML. Comite technique prefectoral de same. Gueckedou:

Ministere de Same Publique, 1996: 1-89.

9

Drame ML, Lynen L, Vandemoortele E. Rapport annuel 1991.

Direction Prefecxorale de la Same. Guinea: Ministere.de Same

Publique, 1992:1-9.

10

Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context.

Soc Sei Med 1994; 38: 1091-110.

11

Van Lerberghe W, Pangu KA, Van den Brock N. Obstetrical

interventions and health centre coverage: a spatial analysis of routine

data for evaluation. Health Policy Ptam 1988; 3: 308-14.

12

Van Lerberhe W, Pangu KA. Comprehensive can be effective: the

influence of coverage with a health centre network on the

hospitalisation patterns in the rural area of Kasongo, Zaire. Soc Sd Med

1988; 26: 949-55.

13

De Brouwere V, Laabid A, Van Lerberghe W. Quels besoins en

interventions obstetricales? Une approche fbndee sur 1’analyse spatiale

des deficits au Maroc. Rev Epidemiol Sami Publique 1996; 44: 111-24.

14

Nordberg EM. Incidence and estimated need of caesarean section,

inguinal hernia repair, and operation for strangulated hernia in rural

Africa. BMJ 1984; 289: 92-93.

15

De Brouwere V. Les besoins obstetricaux non converts: la prise de

conscience de la problematique de la santc matemelle au Maroc.

Louvain: Universite Catholique de Louvain, 1997: 1-225.

16

Van den Broek N, Van Lerberghe W, Pangu KA. Cesarean sections for

maternal indications in Kasongo (Zaire). Im J Gynecol Obstet 1989; 28:

337-42.

17

Kourouma K, Conde S, Gody M. Analyse des taux de cesarienne en

Guinee. Conakry Minivrrr de Same Publique, and Gesellschaft fur

Teghnkehe Zusammenarbeit, 1997: 1-18.

18 Nordberg EM, Mwobodia I, Muniu E. Hospital catchment area and

surgery in Meru district, Kenya. East Afr Med J 1995; 72: 127-29.

19 Menezes d'Alva FR. Analyse du programme de reduction de la

mortalitc matemelle dans le district sanitaire de Gabon. Antwerp:

Institute of Tropical Medicine, 1997: 1-59.

20 McPake B, Hanson K, Mills A. Community financing of health care in

Africa: an evaluation of the Bamako Initiative. Soc Sei Med 1993; 36:

1383-95.

21 McGovern M. Identities and the negotiation of displacement in

Southeastern Guinea. Oxford: Refugee Studies Programme, 1996:

1-19.

22 Goma Epidemiology Group. Public health impact of Rwandan refugee

crisis: what happened in Goma, Zaire, in July, 1994? Lancet 1995; 345:

339-44.

23 Toole MJ. Vulnerability in emergency situations. Lancet 1996; 348:

840.

24 Chambers R. Hidden losers? The impact of rural refugees and refugee

programs on poorer hosts. Ini Migrat Rev 1986; 20: 245-63.

1613

Draft outline, May 24,1993

CHAPTER 6: EMPOWERMENT AND FERTILITY

by

Simeen Mahmud

A.

Historical overview

1.

Traditional transition theory

Traditional demographic transition theory maintains that

aggregate economic development and modernisitation in a society

will ultimately lead to declines in aggregate fertility levels

(Coale,1973).

While

different

societies

will

follow

this

generalised path at different paces depending upon specific

contexts, the completion of transition will be characterised by

declines in mortality levels followed by declines in fertility

levels that tend to stabilise at levels significantly below pre

transition levels. It is assumed that improvements in overall

health and hygiene including the control of epidemics with modern

technology, a rise in literacy levels, and increases in income and

consumption levels will produce appropriate responses in fertility

behaviour patterns of populations experiencing transition. Implicit

in these assumptions is that economic development and modernisation

will effect all segments of the population including women, so that

there should also be visible improvement in the level of female

education and increase in female participation in modern sector

employment which will then motivate couples to limit fertility.

While these theories have recognised that modernising changes

in the economy may influence the motivation of couples to limit

fertility, they have not paid much attention to the dynamics of the

decision making process about reproduction at the individual or

couple level. There is no recognition about how these changes could

affect women's power and autonomy from male domination and their

implications for the fertility decisions of couples and women. Not

surprisingly, they have been unable to explain fertility patterns

in many parts of the developing world where power balances favour

men, and where a range of fertility regimes have been found to

occur in diverse socio-economic contexts, a reality most recently

confirmed by the World Fertility Surveys

(WFS:

Cleland and

Hobcraft, 1985). In attempting to explain "deviant" fertility

patterns in the developing world a macro concept of "women's

status" (measured by aggregate indicators like female literacy and

school enrollment rates or labour force participation rates) was

introduced

as

a

"catch-all"

variable

but

there

was

poor

understanding about both the concept as well as the linkages to

fertility (Mauldin and Berelson, 1978).

2.

Micro vs macro influences

Embedded in the traditional transition theory is the maternal

role incompatibility hypothesis which stipulates that women in

modern sector employment have lower fertility due to role conflicts

between "mothering" and "working". However, this conflict is not

elaborated in terms of its implications for women's domestic power

or role in fertility decision making, but rather more in terms of

a

lack

of

complementarity

between

women's

time

use

in

childbearing/childcare and work outside the home. A reappraisal of

the hypothesis has led to the conclusion that micro rather than

macro structural changes may better explain the relationship

between women's work and

fertility.

Examining the working

environment of women in Malaysia, Mason and Palam concluded that it

was the "household's opportunity structure" through which it

accumulates status and resources which shaped this relationship

(Mason and Palam,1985).

The need to look more carefully at micro-level relationships

that may influence in important ways the fertility decision making

process and how these relationships may vary by social and cultural

contexts was clearly indicated. One of these relationships was

identified as that between men and women in the society, and the

important implications of women's status on their domestic power

and on demographic outcomes was recognised even quite early on

(Mason,1984).

3.

Women's status and fertility theories

More recent demographic theories of fertility decline in the

developing world have invoked the concept of relative female status

as an explanatory variable. Demographers, most notably Caldwell and

Cain, have theorised about the linkages between some concept of

women's status in patriarchal societies and their fertility

behaviour patterns (Caldwell, 1976, 1981; Cain, 1979, 1981). The

essence of these theories is that an improvement in women's status

relative to men will lead to fertility decline.

The argument is that changes in the socio-economic structure

which affect aggregate indicators such as mass and female education

and women's access to or participation in gainful employment will

lead to a significant reduction in the subordination of women by

men (in the first case because of the emotional and material

nucleation of families, and in the second case because of the

reduction of women's economic dependence on men). It is further

argued that this is sufficient to bring about declines in existing

fertility levels since reductions in female subordination will lead

to an increase in the costs of children due to a reversal in the

"wealth flows" and/or a reduction in the "risk-insurance value" of

children to parents. Cain describes the situation of women in

patriarchal societies of South Asia while Caldwell draws his

conclusions from family experiences in the patriarchal Yoruba

community in Nigeria.

However, given that fertility decision making, if at all done

consciously, ultimately takes place within a household context,

there are no explanations about the mechanism through which reduced

subordination of women at the household level can be translated

into a greater role in fertility decisions in situations where this

is empirically observed. Nor do they provide plausible explanations

in situations where these predictions are not valid.

B.

Empirical evidence of the status-fertility relationship

1.

Female education and fertility

One of the first empirical linkages between women's status and

fertility was evidenced in the strong and consistent relationship

between female education and fertility levels. A comprehensive

review of evidence across the developing world revealed that female

education and fertility was inversely related in 11 out of 20

cases, the higher the literacy rate of a country, the more likely

there was to be an inverse relationship, and that female education

was more likely to be inversely related to fertility than male

education (Cochrane,1982). The effect of education on fertility is

hypothesised to be indirect through its impact on certain

"intervening variables". Thus, the effect of education on fertility

depends on how education effects the demand for children, the

supply of children and the use of fertility regulation to limit

births.

Although much of the attention on how female education affects

fertility is focussed on its impact on the costs and benefits of

children, some studies have looked at variables that could provide

insights into women's roles in the fertility decision making

process. It was found, for instance, that education increased the

wife's age at marriage,

husband-wife communication and the

knowledge, attitude and access to birth control all of which were

negatively related to fertility adjusted for age. These factors

could potentially exert a positive impact on women's participation

in fertility decision making but more research is needed to

establish these pathways under different contexts.

(Box on these cross-national correlations ?)

In discussing the complex mechanism through which improved

maternal education raises child survival in rural Punjab, Dasgupta

concludes that education raises skills and self-confidence,

increases exposure to information and alters the way in which

others respond to them (Dasgupta, 1990). Caldwell, too, examining

Nigerian data suggests that women who have been to school are more

likely to elicit behaviour from others like mother-in-law, husband

or health worker that are favourable to child survival (Caldwell,

1979) . These could very well be the same mechanisms through which

education could impact on women's autonomy with regard to

childbearing decisions.

2.

Women's work and fertility

The other source of empirical evidence drawn upon to

illuminate the relationship between women's status and fertility

are studies that examine the effect of women's work and fertility.

However, as Youssef (1982) concludes "Research to date has failed

to provide a clear and consistent explanation of the relationship

between women's employment and fertility, and has not confirmed the

causality". What is recognised, nevertheless, is that both women's

work and fertility emerge from "a family decision making process

that encompasses a number of goals . . . reacting in response to a

common set of social and economic forces as well as to unfolding

events over the life cycle" (Lloyd, 1985).

Empirical observations about the impact of women's work on

fertility and child care can be differentiated along the lines of

type and magnitude of remuneration, work place, type of activity,

and occupation. There are even situations where maternal employment

has been associated with higher infant/child mortality and

undernutrition, reflecting a negative impact on child care, as well

as larger completed families, reflecting a positive impact on

fertility, suggesting that the effect of employment may be more

context specific than that of education. Also, causality is less

easy to establish since most women may work at various points in

their reproductive years,

so that fertility and employment

decisions affect one another.

The important distinction to be made when trying to establish

a relationship between women's work and fertility is that between

earning an income and controlling it. Work which does not alter the

existing gender pattern of control over productive resources and

women's labour is not likely to have any impact on women's decision

making power with regard to fertility. Although it has been

established that women who leave their home for work have the

lowest fertility in most societies, the explanation most commonly

forwarded is that of role conflict. It could very well be that

going out of the home, especially in traditional societies, could

provide women with an enhanced self esteem, greater independence,

access to information and services, peer support and so on that

increase women's self confidence in independent decision making,

e.

i.

their autonomy.

Studies of poor women in South Asia involved in subsistence

income earning work have concluded that these women have a less

subordinate position to men in the household relative to women who

depend entirely on their husband's incomes. These women appear to

have a certain degree of autonomy in their behaviour including in

the use of contraceptives and exhibit significantly lower fertility

levels (N. Nelson; Mahmud,1993). However, evidence is limited and

more work needs to be done to identify pathways of impact on

women's autonomy.

3.

Linkages to women's decision making power

Empirically,

the

education-fertility

(as

well

as

the

education-infant/child mortality)

relationship has been more

consistent than the employment-fertility relationship. This seems

quite understandable since education, being in a sense more

instrumental in terms of influencing learned perceptions should

have a stronger and more consistent impact on women in the form of

enhancing capabilities needed to "gain some control over one's own

life and over the resources needed for survival".

However, it is not yet sufficiently clear what type of

education has the greatest potential for impact on women's decision

making power,

and under what specific contextual conditions

strategies for "empowering education" may be sustained. For

example, aggregate indicators of education are all based on the

Western model of education (as emphasised by Caldwell), but many

would argue that this type of formal schooling with a certain

number of years spent at school, while assisting women to behave in

a more modern way with regard to acceptance of new technology

(birth control, ORS, child vaccination, hygeinic habits), was

totally irrelevant to enhancing capabilities of poor rural women in

traditional situations. Also, it is argued that it tends to

reinforce traditional gender inequalities rather than to question

them. On the other hand, the case can be made for a more informal

and strategic type of education with empowering for women's

practical

and

strategic needs

(cross

reference

chapter on

empowermrnt) . Questions regarding mechanisms of influence as well

as contexts under which these are feasible still remain to be

answered and provide the directions for future research.

The case for the effect of employment on women's decision

making power is more difficult to establish since there is a

diverse range of the type of work that women engage in and the

conditions under which these are undertaken. Empirically, it has

been the experience that both the type of work and the context of

work has significant and varying influence on women's perceptions

about identity and wellbeing and on "enhancing capabilities" for

increasing that wellbeing. The evidence, not surprisingly, has been

mixed,

especially since the effect of employment is often

confounded with the education effect

(eg.

in the case of

professional or non-traditional occupations).

In any case, whatever the direction of causality, there is

sufficient reason to believe that causality is in both directions

since decisions about women's work and fertility are not once for

all decisions and evolve in response to one another and to other

events and decisions. The significance for women's empowerment

strategies lies in identifying the work environment that leads to

an enhancement of women's autonomy and decision making power and

the pathways of influence under situations of varying male control

over women's labour. In this regard, too, much work needs to be

done to answer questions about the viability and sustainability of

these straregies.

C.

Conceptualising pathways of influence

1.

The concept of female status

As the concept of the status of women has entered mainstream

demography, its complexity has led to the use of alternative

definitions and synonyms (female autonomy, women's rights, men's

situational advantage). Mason (1984) reviews these definitions and

concludes that beyond the common focus on gender inequality

"demographers have more than one thing in mind when they discuss

women's status". The three basic dimensions of gender inequality

focussed most commonly were (1)

inequality in prestige,

(2)

inequality in power and (3) inequality in access to or control over

resources.

The complexity derives from the fact that women's status is a

multi-dimensional concept: that there is more than one dimension on

which it is possible for men and women to be unequal, although in

reality a higher status in one dimension,

e.g.

control of

productive resources, may mean a higher status in other dimensions;

that women may be "powerful" in one area such as in domestic

matters but may be completely powerless in another area such as in

the control of productive resources. Superimposed on this is the

fact that gender inequality may vary by location such as the social

unit (family, neighbourhood, community, state) and by stage in the

life cycle (unmarried daughter, young bride, young mother, older

mother of many surviving children, woman with no children, motherin-law, widow, old woman with no assets, and so on).

There is a need to recognise that the different dimensional

and locational components of women's status as used in the

literature may not necessarily respond to structural changes in a

nicely consistent manner. For example, do women who are able to

access productive resources including market opportunuties for

income generation have a higher status because of their freedom

from seclusion (purdah) or have a lower status because they have to

give up the social status associated with purdah (Youssef, 1982).

Alternately, poor women who have to engage in income earning

employment or even educated women in professions may appear to be

less dependent on or subordinate to men in the household but may in

fact have very little autonomy in decisions regarding their incomes

(Safilios-Rothschild, 1980).

2.

How status influences fertility decision making

Drawing conclusions from anthropological studies in developing

countries Epstein (1982) defines women's role as "the way she is

expected to behave in certain situations" and her status as "the

esteem in which she is held by different individuals and groups who

come in contact with her". As a woman proceeds through the

different phases of her life cycle she assumes different roles and

is "awarded different prestige ranking by different people within

her social range". These rankings are in most part hierarchical and

is also closely correlated to the various roles assumed by a woman

within her "social range" which includes the household, the

neighbourhood, the community and the state, generally in the

chronological order of life cycle events. All of these status

rankings in this highly structured system are primarily determined

by

the

woman's

reproductive

outcomes,

being

significantly

influenced by the gender, the number and the timing of her births

(Cain, 1981 in comparing regions in South Asia). However, in

certain situations where women traditionally have access to

independent productive resources these status rankings may also

depend upon women's productive outcomes (Boserup, 1970; Cain, 1981;

Adams and Castle chapter).

Hence, within the existing societal power structure women are

able to ascend to status levels with higher rankings that are

associated with visibly higher levels of "power" with regard to her

relationships within the household (such as control over the labour

of younger household members and domestic labourers, decision

making power in domestic matters and so on) and to a limited extent

with regard to the broader community (such as the prestige awarded

to the elderly) . This type of "power" is however limited or

circumscribed to the extent that it is derived from men and

relationships with men (Safilios-Rothschild, 1982) and does not

significantly increase women's decision making power relative to

men with regard to either their labour or their reproduction.

Given these structural constraints to women's independent

decision making, the mechanisms by which women's status as achieved

through their traditional roles can influence fertility may be

conceptualised as follows:

(Box with diagramme representing these linkages based on Mason,

1984.)

Existing economic and social (including kinship) institutions

determine the low status of women in society. The low status of

women is characterised by gender based inequalities in prestige or

esteem, in the control over productive resources and in decision

making power. These inequalities determine the economic dependence

of women on men and their lack of autonomy from male control, both

of which are instrumental in controling women's labour and

fertility. Women's economic dependence and lack of autonomy dictate

their fertility behaviour and outcome rather than considerations of

their own wellbeing. With changes in the economic and social

structures of communities that are favourable to women (such as

those leading to higher female education or increased female

employment in gainful activities)

it is expected, but with

considerable lag, that women's status will improve reducing the

gender based inequalities. These improvements will eventually

reduce women's economic dependence on men and their lack of

autonomy, so that some concerns for women's own wellbeing may be

reflected in fertility outcomes.

3.

The concept of autonomy/freedom from male domination

Upto now discussions of women's status have primarily focussed

on gender inequality as an outcome but not on decision making power

or women's autonomy as they effect these outcomes. Even when

demographers have used the concept of female autonomy,

its

implication for women's freedom of control from others has been

restricted to personal matters. Dyson and Moore (1983) explain the

equality of autonomy between men and women as implying "equal

decision making ability with regard to personal affairs", but do

not extend their definition of female autonomy to include decision

making power beyond personal affairs. This is misleading because

fertility decision making, while very much a personal concern for

women, is also significantly influenced by family and often

community situations to the extent that childbearing determines

women's status in those social locations.

There is also no discussion about how gender perceptions of

identity and wellbeing, often utilised to maintain existing

inequalities in status (Sen,1990; Papanek, 1990) can be shaped by

power relations between men and women or about how these

perceptions may determine women's autonomy in decision making

affecting their lives.

Clearly,

the concept of

female

autonomy needs to be

distinguished from that of women's status since the question of

power relations between men and women and how they affect decision

making is very central to it. Even though women may rise to higher

status levels through their traditional roles, both as producers

and reproducers of labour, their subordination to men is not

necessarily reduced. Thus, although women may gain some power over

the lives of younger women and some younger men in the household,

they still have very little power and autonomy about decisions

affecting their own lives (Safilios-Rothschild, 1982). In fact,

women's greatest subordination occurs at a time when they are being

initiated into fertility behaviour patterns that are not geared

towards their own wellbeing but towards that of their families.

Even when women are earning incomes they are often unable to

translate these into decision making power if men control the

income and the conditions under which women can work.

The

traditional gender balance of power is such that male dominance

over women at all dimensions and locations takes the form of

variously controlling women's labour and fertility, and the

consequences of their fertility, by restricting their power and

ability to make independent decisions about their labour and their

reproduction.

It may be hypothesised that the major constraints to

increasing women's wellbeing in a male dominated environment has

been their lack of autonomy from men in decision making which

affects their wellbeing, including reproduction, and the fact that

women are resigned to accept the "legitimacy of the established

order". Sen (1990) has argued that women's perception (or the lack

of them) of their own wellbeing and self-worth can be an important

factor in the perpetuation of existing gender imbalances in power,

but that these are not necessarily resistant to change or

alteration through conscious social policy.

4.

Empowerment and its linkages to fertility decision making

The previous discussion would imply that one way of increasing

women's autonomy and decision making power would be to provide them

with an alternative power base that was independent of the

domination of men. Even in societies characterised by highly skewed

gender balance of power and control of productive resources, women

may gain access to power from certain kinds of empowering

experiences

like the process of politicization

for gender

awareness,

processes

of

economic

change

or

processes

of

mobilisation for economic, social or psychological support.

(These processes are described in the chapter on Conceptualising

Empowerment. That chapter will also try to define empowerment in

terms of a process rather than an end or even a means to an end,

and that it is a process that the process of gaining power "begins

in the mind with self image and confidence, with understanding the

environment, with ability to turn weaknesses into strengths ...)

The mechanism by which such empowering processes may impact on

women's autonomy and fertility decision making is conceptualised

below:

(Box showing how the mechanism of impact of women's status on

fertility is modified by introducing the notion of increased

decision making power and autonomy which accompanies women's

empowerment strategies)

The pathways of influence of women's empowerment on their

fertility behaviour may be both indirect and direct. Empowering

experiences impact on women's perceptions of selfworth and

wellbeing and through them on their economic dependence on men and

their lack of autonomy in decision making. These impacts flow back

into

the

hierarchical

social

structure

through

women's

relationships with men and other "powerful" women to exert

influence in changing the established gender inequalities in

prestige, control over resources and decision making power, i.e.

the components of women's low status. Changes in women's status

then affect fertility behaviour through the traditional channels as

described in the previous box. This is the indirect effect of

empowering experiences on fertility. The direct impact on fertility

is through the formation of new relationships within the different

social locations (household, community, state, market) which

embodies self confidence, access to independent information, peer

support, physical mobility and so on, in such a way that women's

own wellbeing (family size preferences, health needs, birth control

preferences, employment alternatives, healthy children) as well as

that of their children and other vulnerable groups dictates

fertility behaviour and outcomes. Also, since the empowering

experience is conceptualised as a process rather than an end,

impacts on fertility behaviour is also expected to be an on-going

flow responding to external forces and life cycle events as they

unfold.

5.

Power sharing and responsibility

Obviously, if fertility decision making has to be a conscious

one by both men and women in response to structural changes that

effect them differently, then the mechanism by which these changes

influence decision making has to do with the balance of power

between women and men in all the different social locations like

the household, community and the state within which they interact.

In other words, there must be a reallocation of power in favour of

women at all different dimensional and locational contexts,

allowing them to alter their reproductive behaviour for their own

wellbeing. This may entail some "negative externalities" in terms

of men feeling threatened or the established order being questioned

by more "powerful" women.

So far women have had to bear the burden of reproduction at

the cost of their own wellbeing (economic independence, education,

health, healthy offspring, mobility), while men have been enjoying

the benefits. Thus, the underlying assumption of empowering

strategies for women has been that altering reproductive behaviour

is primarily a woman-specific concern, perhaps even a concern with

opposing gender interests.

Increasingly, it is clear that the concern needs to be not

only gender neutral but also a societal concern, i.e. women's

empowerment strategies need to incoroporate a greater role and

responsibility even accountability of men and the broader societal

institutions. The empowering process must be able to elicit a more

caring and responsible attitude and behaviour from the other actors

in this decision making scene. In other words, it must be ensured

that the empowering process does not burden women with additional

segregated

responsibility.

The persistence

of gender based

allocative inequalities in a society is not only determined by

power relations but also rationalised by the implicit priorities

and generalised notions of distributive justice that have emerged

over many years. It should be remembered that these relations and

notions are not likely to vanish automatically with the process of

women's empowerment.

Other existing political structures such as the lack of a

democratic state structure, the presense of a communist or a

socialist state structure, the presense strong patron-client

relationships, the emergence of religious fundamentalism will

significantly influence the operationalisation and impact of

strategies for women's empowerment.

REFERENCES

A.J.Coale (1973). Will be provided.

W.P.Mauldin and B.Berelson (1978) "Conditions of fertility decline

in developing countries,

1965-1975",

Studies in Family

Planning, 9(5), 139-41.

K.O.Mason and V.T.Palam (1981) "Female employment and fertility in

Peninsular Malaysia: The maternal role incompatibility

hypothesis reconsidered", Demography, 18, 549-575.

J.Caldwell (1976) "Towards a restatement of demographic transition

theory", Population and Development Review, 2, 321-366.

(1979) "Education as a factor in mortality decline: An

examination of Nigerian data", Population Studies, 33(3), 395413.

(1981)

Will be provided.

M.Cain and S.Nahar (1979) "Class, patriarchy and women's work in

Bangladesh", Population and Development Review, 5, 405-438.

M.Cain (1981) "Risk and insurance: Perspectives on fertility and

agrarian change in Bangladesh and India", Population and

Development Review, 7, 435-474.

K.O.Mason (1984) The Status of Women: A Review of its Relationships

to Fertility and Mortality, The Rockefeller Foundation, New

York.

N.H.Youssef (1982) "The interrelationship between the division of

labour in the household, women's roles and their impact on

fertility",

in R.Anker, M.Buvinic and N.H.Youssef (eds)

Women's Roles and Population Trends in the Third World, Croom

Helm, London and Sydney.

C.Safilios-Rothschild (1980)

Will be provided.

(1982)

"Female

power,

autonomy

and

demographic change in the Third World", in R.Anker, M.Buvinic

and N.H.Youssef (eds) Women's Roles and Population Trends in

the Third World, Croom

Helm, London and Sydney.

T.Scarlett Epstein (1982) "A social anthropological approach to

women's roles and status in developing countries: The domestic

cycle", in R.Anker, M.Buvinic and N.H.Youssef (eds) Women's

Roles and Population Trends in the Third World, Croom Helm,

London and Sydney.

E.Boserup (1970) Women's Role in Economic Development, St.Martins

Press, New York.

M.Dasgupta (1990) "Death clustering, mother's education and the

determinants of child mortality in rural Punjab, India",

Population Studies, 44, 489-505.

C.Lloyd (1991) "The contribution of the World Fertility Surveys to

an understanding of the relationship between women's work and

fertility", Studies in Family Planning, 22(3), 144-161

S.Singh and J.Casterline (1985) "The socio-economic determinants of

fertility", in J.Cleland and J.Hobcraft (eds) Reproductive

Change in Developing Countries: Insights from_ the__World

Fertility Survey, Oxford University Press, New York.

N.Nelson (19 ) Why Has Development Neglected Rural Women: A Review

of the Literature from South Asia, Pergamon Press,

S.Mahmud (1993) "Female power: A key variable in understanding the

relationship between women's work and fertility', (unpublished

manuscript), Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies,

11

12

Dhaka.

A.K.Sen (1990) "Gender and cooperative conflicts", in Irene Tinker

(ed) Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development,

Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford.

H.Papanek (1990) "To each less than she needs, from each more than

she can do: Allocations, entitlements, and values", in Irene

Tinker

(ed)

Persistent

Inequalities:

Women

and

World

Development, Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford.

T.Dyson and M.Moore (1983) " On kinship structure, female autonomy,

and demographic behaviour", Population and Development Review,

9, 35-60.

S.Cochrane (1982) "Education and fertility: An expanded examination

of the evidence" in G.P.Kelly and C.M.Elliot (eds) Women's

Education in the Third World: Comparitive Perspectives, SUNY

Press, Albany.

(Draft for discussion-Feb, 2001)

Health Task Force

Women's Health

Why the need to look at Women's Health as a separate agenda• Consequences of poor health of women, as against those of men, are far greater since their poor

health translates into poor health of families, particularly the children who represent the future

generation. A mother’s death has twice the impact of afather’s death on child survival. "Women Days- Lost' due to ill health therefore includes many hidden but critical factors which impact on

the family and in the larger context on the health of the community and the nation.

• Also, gender related factors impact negatively on all issues related to women, including health.

Health status of women in Karnataka:

The overall health and developmental status of women and children in Karnataka has improved over

the past several decades.

But, as can be seen by the health indicators and developmental indices, the improvement does not

compare favourably with that of States like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra etc.

There is a considerable disparity between Rural & Urban Karnataka, between males & females and

regional disparities with the districts of Raichur, Koppal, Gulbarga, Bidar, Bellary, Bijapur and

Bagalpur characterized as category C due to poor health and other developmental indicators.

Health Indicators of Karnataka:

Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)

The IMR is 51.5 according to NFHS-2, and 58 according to SRS 1998.

IMR is 70 for Rural and 25 for Urban areas and varies from 29 in Dakshina Kannada to 79 in Bellary.

The Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) according to UNESCO is 450. But recent estimates by SRS

(1998) places it at 195 per 100,000 live births.

Life Expectancy at Birth (LEB)

The International Conference on Population Development had resolved to target an LEB of 70 by 2005

and 75 by 2015. Karnataka has only reached 62.

LEB of women was higher than that of men throughout the State, but the difference ranged from the

highest of 9 in Kolar and Hassan and only 0.62 in Bangalore (Urban).

LEB was highest in Dakshina Kannada with 68.82 and lowest in Bellary with 57.12years.

Crude Birth Rate

The SRS estimate of CBR in 1998 was 22 per 1000 population; 23.1 in rural as against 19.3 in urban

areas. CBR has been fluctuating widely rather in Karnataka and the regional disparity is similar to

other indices.

Crude Death Rate (CDR)

CDR as estimated by SRS (1998) was 7.9 per 1,000 population; 8.6 in rural as against 6.9 in urban

areas.

CDR varied from a low of 7 in Dakshina Kannada & Shimoga, to a high of 10.5 in Gulbarga.

Developmental Indices of Karnataka- HDI4 GDI

The Gender-related Development Index (GDI) measures the overall achievements of women and men

in the three dimensions of the Human Development Index (HDI) -life expectancy, educational

attainment and adjusted real income-and takes note of inequalities in development of the two sexes.

The methodology used imposes a penalty for inequality such that the GDI fells when the achievement

levels of both men and women in a country go down or when disparity between their achievements

increases. The GDI is therefore the HDI discounted for gender inequality.

Though the GDI and HDI are not comprehensive and do not cover all aspects of human development

they serve to high light disparities within the State as well as Ae consequences of gender

discrimination.

According to the 1991 census the Gender Ratio is 960 women for 1,000 men. This is worse than in

Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa and Tamil Nadu. But more disturbing is the fact that it has worsened

between 1981 & 1982.

The Gender Ratio is unfavourable to women in most districts except in Dakshina Kannada & Hassan

The IMR for females is 72, and highest in Dharwad Bellary & Bidar.

Age specific mortality rates indicate that 26% of deaths of women occoured between 15 - 34years of

age as against 15% among mea

Reasons for the poor health status of women in Karnataka:

The efforts taken to address women’s issues have been inadequate, distorted, vertical, top-down and

have rarely emerged out of women's priority concerns. Gender disaggregated data is often not

collected on women’s morbidity, suffering and paia

• Health seeking behavior of women: The ingrained gender insensitiveness in society has led to

women themselves relegating their own physical and mental health, emotional and social needs as

their last priority, if at all.

' • The health needs of women are addressed by the RCH programs, which are restricted to the

reproductive phase. Very little systematized attention is being paid to their other health needs and

much less to their emotional needs.

Factors for consideration:

The Gender Concept

Gender

Gender is the different meanings and roles that societies and culture assign to people, based on whether

a person is male or female. It is a strong, but often unacknowledged, part of what we learn as we grow

up, for example, how we treat each other and ourselves.

" This means that men are expected to behave in a particular manner, women in a different manner and

transgendered persons in another manner.

These divisions and roles are not equal between men and women and women are usually given less

powerfill and restricted roles to perform. This also means that the impacts of social phenomena are

different on the different genders.

These roles change with changing times as well as within communities from time to time due to factors

like improved literacy, higher economic status etc.

Gender Diicrimination

From the time of conception the girl child is discriminated against all her life. This includes being

subjected to foeticide & infanticide and sexual abuse; being weaned from breast feeds earlier than male

babies; her nutritional, health, emotional and other needs being given the last priority, having

restricted access to education- either not sent to school at all or if sent, not allowed to complete her

education in order to look after siblings or do household & other work; and are often married off

during adolescence.

The woman is required to meet the needs of her family before her own needs and acquires recognition

as » family member only after she bears a child, and more specifically a male child.

She has very little decision-making power and issues concerning her are marginalized.

When gender discrimination has been socialised and internalised, it is no longer visible to the gender

insensitive. Unfortunately, religion, health care, education the legal system, employment and the

media, reflect and promote gender discrimination.

Men continue to control decision-making, limited family resources, women's sexuality, freedom of

movement, access to the world outside the home, etc.

So women need a supportive environment to ensure that they are fed adequately, are educated and can

make decisions regarding their life and their children.

Gender sensitivity

Gender sensitivity is an understanding and consideration of different needs of women and men arising

from their unequal social relations and that a policy or programme can thus benefit women and men

differently.

Gender sensitive indicators

Gender sensitive indicators are required to measure the integration of gender sensitivity into any given

programme. They will point out changes in the status and roles of women and men over time, and

therefore measure whether gender equity is being achieved.

Gender issues related to health care

Even when available, health care services are underutilized by women because:

• They are occupied all day with work related to childcare & household tasks, and work outside the

house, and often neglect illnesses in the early stages.

• Health services available are insensitive to women’s needs. They are staffed with male workers;

privacy is ignored; the timing is inconvenient and long waiting periods result in lost wages.

• .Access to health care facilities is inadequate. These include factors like long distances; lack of

transport and even when available an inability to pay for it; a lack ofindependence that prevents

them from leaving their homes alone and restricts them from using their own income or savings;

the expenditure incurred even in the supposedly free health care facilities etc. This is especially

critical when emergency care is required and is a major factor resulting in high maternal and

neonatal mortality.

• The health needs other than those associated with their reproductive capacity are neglected.

• Their awareness of available facilities tends to be lower than that of men.

• They are also not aware of their rights and often do not think they have any.

Poverty & illiteracy

40 % of people in Karnataka are below Poverty Line. Poverty coupled with Gender bias and poor

social and economic status of girls and women limits their access to education, good nutrition as well

as money to pay for health care and family planning services.

Though the enrolment in primary schools exceeds 8.2 million; percentage of children in age group 614 attending schools is 65.3(rural) & 82.4 (urban) and drops out rates have declined from 69% in 1950

to 16.5% , still 2.6 million children (28%) in 6-14 age group are out of school.

Girls participation has gone up from 44.5 in 1980 to 48 in classes Ito 4 and from 39 to 45 in classes 1

to 7and the drops out rates has declined from 73% to 17%. But still there is need for improvement

Literacy programmes are not sustained despite good work in the early years. So the literacy rate is 56%

for Karnataka but rural female literacy in Raichur is a dismal 16.48%

3

Low levels of Female Literacy is a major factor resulting in high rates of maternal & infant mortality,

female foeticide, skewed sex ratio & dowry deaths.

Some reasons for girls not being sent to school are- to care for younger siblings, housework etc., for

economic reasons, fear of sexual harassment and sexual abuse, far off locations, an overwhelming

number of male students and a fear of not being able to get a groom with higher educational

qualification than the daughter.

Women & Work

Wage earning empowers women in decision making. Non -wage earners do not have this advantage

and their contribution is not even recognized. The down-side to this is the fact that very often women

do not have control over their earnings. Also, work outside the home places an additional demand on

the women who are already burdened with household work; reproduction and child rearing; and family

demands- both physical and mental.

1 Girls start working earlier than boys, work longer and harder throughout their lives. The energy

consumption in mere survival tasks of fetching fuel, water, fodder, care of animals; washing; cleaningwhich are exclusively women’s responsibility, results in negative nutritional balance and calorie

deficit The situation worsens when women also have to perform hard labour for wages. Walk long

distances to fetch water and fuel, especially in hilly areas; take care of large extended families, caring

of children, elderly, sick husband and animals is done by women alone with little or no help.

All the above domestic work is unpaid work and is cbnsidered unproductive work. Even when

women work outside the home, they domot get equal.wages for equal work and are made to perform

unskilled jobs which are poorly paid, more hazardous and demanding. They face various occupational

health hazards. Rural women cooking in poorly ventilated huts using wood and cow dung cakes as

fuel, are exposed to 100 times the acceptable level of smoke particles. This is equivalent to smoking 20

packs of cigarettes a day and can cause Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease. Women forced to earn

their living as commercial sex workers are prone to infections like STDs, HTV, etc. from their male

clients.

Nutrition

Malnutrition

Though the incidence of severe malnutrition has declined to negligible levels, problems due to milder

levels of protein -calorie malnutrition, and deficiency of iron, iodine and vitamin A deficiency are seen

among a majority of women & children in India.

The Women & Child Departmen and not the department of H&FW is responsible for ensuring the

nutrition of the people. The ICDS projects have not been able to ensure adequate nutritional coverage

for children.

Denial of adequate food to girls, partly due to non-availability and partly due to discrimination, results

in the lower nutritional status of women. Height for age is a sensitive indicator of adequacy of

nutrition. This data shows that girls are more malnourished than boys today in Karnataka

An inadequate diet has life-long consequences for girls and their growth and development is

jeopardised. The nutritional needs of girls especially of iron, vitamin A, calcium and iodine, increases

with the growth spurt associated with puberty and onset of menstruation Early marriage and early

pregnancy further deplete their inadequate reserves.

The woman herself is partly responsible for this. She considers her nutritional and health needs as the

last priority and does not know the importance of her own health as a contributing factor in ensuring

the health of her children

Rising food prices, limitations of the public distribution system and shift to non-edible cash crops, will

undoubtedly worsen the existing nutritional status of women.

Other than the direct ill health caused, malnutrition in women directly contributes to mortality &

morbidity in infants and children.

A child's physical & mental potentials are formed during the period from conception to 3years of age

ofwhich rapid development takes place in the first 18months. So the nutritional status of women

during pregnancy and lactation and of young children is of paramount importance for later

development

Likewise, the nutritional status of adolescent girls shapes the nutritional status of women during

pregnancy and lactation.

• 20% of maternal mortality is directly related to anaemia.

The prevalence of Anaemia among women in Karnataka:

Age in years

Mild%

10.0-10.9gm/dl-children,

pregnant women

10.0-11.9gm/dl-nonpregnant women

Moderate%

7.0-9.9gm/dl

Severe%

< 7.0gm/dl

15-24

29.3

16.4

1.7

47.4

25-34

25.4

12.5

2.4

40.2

35-49