RF_RJS_4_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_RJS_4_SUDHA

RJS-

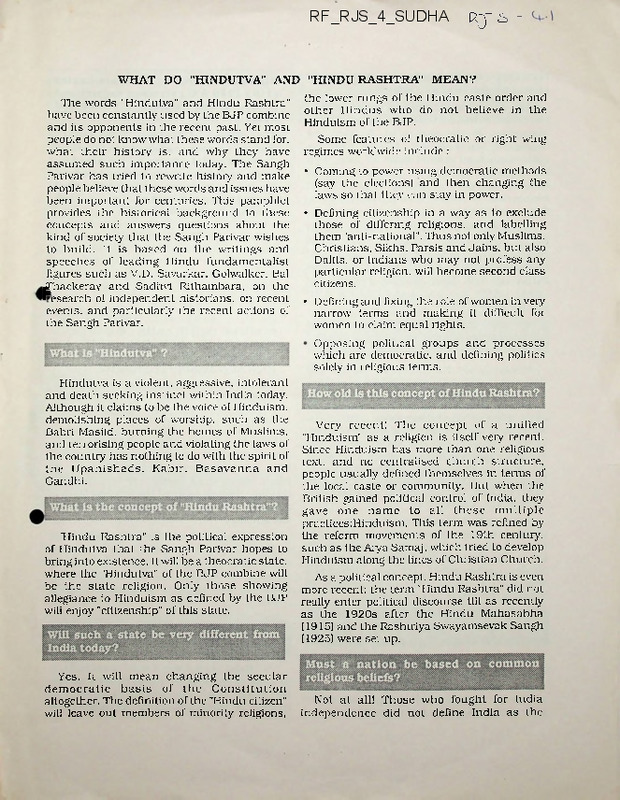

WHAT DO "HINDUTVA" AND "HINDU RASHTRA" MEAN?

The words "Hindutva" and Hindu Rashtra"

have been constantly used by the BJP combine

and its opponents in the recent past. Yet most

people do not know what these words stand for.

what their history is. and why they have

assumed such importance today. The Sangh

Parivar has tried to rewrite histoiy and make

people believe that these words and issues have

been important for centuries. This pamphlet

provides the historical background to these

concepts and answers questions about the

kind of society that the Sangh Parivar wishes

to build. It is based on the writings and

speeches of leading Hindu fundamentalist

figures such as V.D. Savarkar, Golwalker. Bal

Thackeray and Sadhvi Rithambara, on the

"esearch of independent historians, on recent

events, and particularly the recent actions of

the Sangh Parivar.

I

the lower rungs of the Hindu caste order and

other Hindus who do not believe in the

Hinduism of the BJP.

Some features of theocratic or right wing

regimes worldwide include :

• Coming to power using democratic methods

(say the elections) and then changing the

laws so that they can stay in power.

• Defining citizenship in a way as to exclude

those of differing religions, and labelling

them "anti-national". Thus not only Muslims,

Christians, Sikhs, Parsis and Jains, but also

Dalits, or Indians who may not profess any

particular religion, will become second class

citizens.

• Defining and fixing the role of women in very

narrow terms and making it difficult for

women to claim equal rights.

Opposing political groups and processes

which are democratic, and defining politics

solely in religious terms.

Hindutva is a violent, aggressive, intolerant

and death seeking instinct within India today.

Although it claims to be the voice of Hinduism.

demolishing places of worship, such as the

Babri Masjid, burning the homes of Muslims.

and terrorising people and violating the laws of

the country has nothing to do with the spirit of

the Upanishads, Kabir, Basavanna and

Gandhi.

"Hindu Rashtra" is the political expression

of Hindutva that the Sangh Parivar hopes to

bring into existence. Itwill be a theocratic state.

where the 'Hindutva" of the BJP combine will

be the state religion. Only those showing

allegiance to Hinduism as defined by the BJP

will enjoy "citizenship" of this state.

Yes. It will mean changing the secular

democratic basis of the Constitution

altogether. The definition of the "Hindu citizen"

will leave out members of minority religions.

Very recent! The concept of a unified

"Hinduism" as a religion is itself very recent.

Since Hinduism has more than one religious

text, and no centralised church structure,

people usually defined themselves in terms of

the local caste or community. But when the

British gained political control of India, they

gave one name to all these multiple

practices:Hinduism. This term was refined by

the reform movements of the 19th century,

such as the Arya Samaj, which tried to develop

Hinduism along the lines of Christian Church.

As a political concept. Hindu Rashtra is even

more recent: the term "Hindu Rashtra" did not

really enter political discourse till as recently

as the 1920s after the Hindu Mahasabha

(1915) and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

(1925) were set up.

Not at all! Those who fought for India

independence did not define India as the

homeland of the Hindus, but as a nation where

several religions could co-exist.

The "nation" is the most recent of political

formations in human history (as opposed to the

monarchy, or the oligarchy). Nations are

"imagined communities", unities that are

conscious!}’ built around some identity, such

as language, culture, or shared historical

experiences, not necessarily religion. If all

members of one religion belonged to one nation,

there would be only a few nations in the world.

IN OUR OWN REGION, BANGLADESH

SPLIT AWAY FROM PAKISTAN AROUND A

BENGALI CULTURAL IDENTITY. THERE ARE

SEVERAL NATIONS IN THE WORLD, SUCH AS

INDIA OR THE USA. WHERE PEOPLE OF

DIFFERENT RACES, LANGUAGES AND

BELIEFS CO-EXIST.

Absolutely not! The concept of "Hindus" and

"Muslims" constituting two separate political

communities is very recent, a British creation.

When the British established their rule over

India, they portrayed themselves as those who

established law and order in a divided country.

To them, religion was the prime moving force

in history: that is why British historians started

the practice of dividing Indian history into

Hindu (pre 1206) and Muslim (after 1206 to

1757) periods. But they called their own rule

"British" not "Christian"!

It was only during the colonial period that

political representation began to be defined in

terms of religious communities. This gradually

led to the demand for Pakistan from some

Muslim communalists. Yet even when India

was partitioned in 1947. the majority of

Muslims decided to stay on in India.

Most Indian rulers did not see themselves as

"defenders of the Hindu faith" or the "Muslim

faith". In fact, temples were routinely

plundered even by Hindu kings, since they

were centres of wealth and treasure.

• Subhatvarman, a Parmara ruler

(1193-1210 A.D.) attacked Gujarat and

plundered Jain temples in Dabhoi and

Cambay.

• King Harsha of Kashmir (1089-1101) (not the seventh century Harsha) melted

down all metal images in his kingdom

when he faced a grave economic crisis:

he even appointed a minister called

"Devotpatana Nayaka" i.e. "a high

minister for uprooting gods".

Destroying shrines was also a way of

expressing political supremacy. The Jagannath

temple at Puri is built on the ruins of a tribal

shrine, and in Bodh Gaya, a Buddhist vihara

was destroyed by Sasanka to build a Hindr^

shrine in the sixth century.

”

* IN JULY 1991. THE BJP/RSS/VHP

COMBINE IN THE NAME OF KAR SEVA

DESTROYED SEVERAL TEMPLES

INCLUDING THE SANKAT MOCHAN

HANUMAN MANDIR IN AYODHYA.

‘ ON 6TH DECEMBER 1992. THE SAME

COMBINE DESTROYED THE RAM

CHABUTRA AND SITA RASOI ALONG

WITH BABRI MASJID.

Even Tipu Sultan, who has been painted as

a bigot by colonial historians and is believed to

have converted large numbers of people to

Islam, always had a temple very near eveiy fort

he built. He even assured the Sringeri Math of

assistance when it was threatened by the

Marathas.

We do have one Indian king who used all the

state machinery to propagate one religion by

declaring it the state religion. His name is

Ashoka, the religion was Buddhism, yet he

continues, even today, to be considered a great

ruler.

The Babri Masjid was a small mosque built

in 1528 at Ayodhya by one of Babar's nobles.

Mir Baqi. There are several mosques and

temples in Ayodhya. Until 22 December 1949.

namaz was offered daily at the Babri Masjid.

and Hindus worshipped at Sita ki Rasoi nearby.

On that date, the local District Magistrate. K K

Nayar, allowed some priests, one of whom is

still alive today, to instal a few idols in the

mosque. The Babri Masjid was sealed, namaz

was stopped, and the case was referred to the

court.

THE DISPUTE OVER THE BABRI MASJID

WAS NOT A NATIONAL ISSUE UNTIL 1986

WHEN THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT OF

RAJIV GANDHI ALLOWED THE FAIZABAD

ADMINISTRATION TO OPEN THE TEMPLE

FOR DARSHAN ON MAY 1. 1986, EVEN

BEFORE THE CASE WAS DECIDED IN

COURT. SOON THE DEMAND FOR BUILDING

WlE RAMJANAMBHOOMIATTHE SAME SPOT

AS THE BABRI MASJID BECAME AN ALL

INDIA AFFAIR DUE TO THE EFFORTS OF THE

BJP AND VHP. IN 1989. THE CONGRESS

GOVERNMENT. JUST BEFORE IT FELL.

AGAIN GAVE PERMISSION FOR THE

CONDUCT OF SHILANYAS PRELIMINARY TO

BUILDING A TEMPLE.

On

December

6.

1992.

the

BJP/RSS/VHP/BajrangDal and the Shiv Sena

bigots destroyed the Babri Masjid in open

defiance of the constitution, the judiciary and

the central government.

B Eminent independent historians with

national and international reputations who

have extensively studied the historical and

archaeological evidence have shown that there

is no authentic basis for the existence of an

11th centtuy shrine.

The VHP. however, has been claiming that

there was a Vaishnava shrine celebrating the

birth place of Rama at the site of the Babri

Masjid.

We condemn the destruction of all religious

sites whether in Punjab. Kashmir, Pakistan,

Bangladesh, or South Africa. Unfortunately,

religious structures have routinely been

destroyed in communal riots since

independence.

• it is not even established whether the

spot is the birthplace of Rama.

• no evidence exists in the texts before the

16th century that people venerated the

site for being the birth place of Rama.

• 14 black pillars which were found at the

site with figures on them do not match

each other, were brought from

elsewhere, do not have Vaishnava

markings, and could not have been from

a temple.

• the first suggestion that there was a

temple at the site came in the writings

of a Jesuit historian Joseph Tiefenthaler

in 1788: this was categorically denied by

another colonial chronicler Francis

Buchanan in 1810.

• the BJP historians have not allowed the

independent historians to examine the

archaeological notes on which they base

their claim.

THE DEMOLITION OF THE BABRI MASJID

IS DIFFERENT FROM ALL SUCH

DESTRUCTION. IT WAS NOT JUST AN ACT OF

VANDALISM BY A MOB OUT OF CONTROL.

BUT WAS PART OF A SUSTAINED CAMPAIGN

AGAINST THE RULE OF LAW AND

DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS. PUBLICLY

ANNOUNCED AND SUPERVISED BY THE

LARGEST

OPPOSITION

PARTY

IN

PARLIAMENT. THE BJP. WHO SWORE TO

UPHOLD THE CONSTITUTION.

The events of the past few months have caused untold suffering, loss of life and

property and serious disruption of normal life for millions of Indian people. Many of

us feel pained, ashamed and extremely anxious about the future of secularism and

democracy in India. Fascist goon squads have unleashed a reign of terror and appear

to be bent on destroying the democratic foundations of this country; even those who

have sworn to uphold the Constitution have violated the rule of law.

The activities of the fascist goon squads bear no resemblance to religious activity

of any description. On the contrary these violent schemes have torn the fabric of the

nation and polarised the nation in ways unseen since Independence. Hence it is

imperative that these forces be countered. We must not be overwhelmed by the large

numbers that have been mobilised by the BJP. VHP. RSS, Bajrang Dal, and Shiv

Sena. The choice is between the politics of life and death, between secular democracy

and communal fascism, between India and Hindu Rashtra.

We believe that in a multi-ethnic, multi-language, and multi religious nation such

as ours, there is no alternative to the path of secular democracy. Secularism must

guarantee all citizens the absolute and unconditional right to practice the faith of

their birth or choice, provided it does not impinge on the democratic rights and

freedoms of other citizens.

The Indian state must guarantee equality of all religions before law. and cannot

implicitly or explicitly support the demands of any single religious group. Neither

language, religion nor ethnicity can be the sole basis of citizenship in this country

nor should any of these identities be considerations to deny access, on a fair and

equitable basis, to any of India's citizens.

Recent events have clearly shown that secularism cannot be merely a political ideal

enshrined in the constitution and enforced by the state. The current situation

demands a massive movement of all Indians committed to secular and democratic

freedoms, i.e. the broadest possible alliance between parties, groups, organisations,

unions and individuals committed to fighting these communal forces. Such groups

have already emerged and begun working in all parts of India. In Bangalore too,

several writers, artists, scientiests and activists have formed a broad based coalition

to bring out materials, organise educational programmes and network with the state.

Come, Join our fight for a just, secular and democratic India.

Begin now. by using the information in these pamphlets to counter lies and

misinformation in conversation with friends, relatives and colleagues in schools,

colleges and places of work.

COALITION FOR SECULARISM.

e

g-ps-u

MY EXPERIENCE WITH SADGURU SAI SHANKAR

(Lord Shankar manifest in the instrumental person

of Sri A. T. Kariappa)

h

1 am the grandson of Late Sir A.P. Patro, Kt., K.C.I.E.,

Minister of Law and Education, Madras State, leader of the

Justice Party and member of the team led by Mahatma

Gandhiji to the three Round Table Conferences held at

London; son of late Sri A. V. Patro, M. B. E., I. P., Commi

ssioner of Police, Madras, LG. of Police, Hyderabad.

Having lost my grandfather and father by the age of nine,

I was left entirely in the care of my mother who had to bring

up my three elder sisters and myself. I completed my

graduation and post-graduation courses in politics and public

administration from Loyala and Presidency College, Madras,

respectively. My pursuits in the athletic field comprised of

being a minus one handicap polo player, tennis and swimming

captain of Presidency College team, winner of the Earl Rob

ert’s International Shooting Competition, adjudged All India

Best Cadet at Advanced Leadership Course held at Pahalgaum,

jKashmir, and represented Madras Gymkhana and Cricket

FCIub in the Spencer Trophy Snooker Tournament.

I was brought up under affluent circumstances in an

aristocratic manner moving in the higher echelons of society

and at no stage was denied any wants, which ultimately

boosted my ego to such an extent that I tended to look down

upon people around me whom I thought were financially,

mentally, physically or otherwise of lower degree than I was

at. This conception was carried on along the years until the

cycle forced it down to the lowest where 1 myself had to look

to the same people around me for help. This original

egoistic behaviour of mine proved very detrimental to the

basic factors such as character, self-respect, social status,

friendship and finance. It was due to this maladjustment in

personality that I tended to lean towards the Bohemian life.

Gradually I became deeply involved in gambling, on horse

racing where I lost colossal amounts of money and indulged

in about fifteen years of hard drinking and all the sensual

pleasures that go with it.

It was at this stage when I was at the crossroads of my

life that I just about realised that I had reached the end of

the tether of a wasted life and would soon end in total ruin

if not helped by some strong force. And it was in this

frame of mind that I resolved to seek some spiritual guidance)

which I thought would recast my personality and make me

learn the true values of life that would give lasting peace of

mind. This I believed would show me the path to a more

purposeful future. I sought solace and guidance in various

ways, none of which proved fruitful. I wandered from town to

town trying to assimilate various kinds of advices, apparently

being given to a lost soul more out of pity rather than man to

man and anything constructive or conducive to my frame of

mind at that time. It was during this run-around that I re

membered two close friends of mine, namely Sri M. Harish

Chittiappa and Sri M. Pratap Chittiappa of Coorg, Karnataka

who happened to be the life of parties that I used to attend

during my Bohemian life. I heard that Pratap Chittiappa had

turned over a new leaf and was treading a spiritual path of

total dedication to Lord. He had set up a Spiritual Guidance

Nilayam at his estate in Coorg, complete with cottages for

aspirants, Bhajana Mandir etc. All this had been done,

through the guidance of his spiritual preceptor, Sri Sadguru

Sai Shankar. I contacted Sri Pratap Chittiappa enquiring

details of whether I could stay at the Spiritual Guidance

Nilayam. He consulted Sadguru Sai Shankar who immedia

tely asked Sri Pratap to give his consent to my request.

that this figure did not manifest in itself the Supreme Power.

Initially, in the first few days of my stay in the Spiritual

Guidance Nilayam, I was deluded to think that the Swamiji

clad in long gown, moving freely with me and intimately

enquiring into my problems, was really the person who was

instrumental in correcting and giving peace of mind and

salvation to the numerous educated disciples and followers,

both foreign and Indian, and persons drawn from every strata

of society. The basic feeling of open mindedness to the

subject on hand being discussed with Swamiji made me feel

^hvays at ease that whenever I happened to mention that ‘ 1 ’

did such a thing or ‘ 1 ’ did not do such a thing, the very fact

that I got a neutral reply made me feel that I was emphasi

sing my ego- This fact was more so brought out by the

very simplicity that was the base of all these conversations

wherein rudimentarv facts and figures explained by Swamiji

made me feel already ashamed to say once again that I had

done this or that which only went to prove how small minded

my thinking was.

Upon arrival, I was taken to Prashanthi Nilayam,

Ponnampet, where I was impressed by the atmosphere, activi

ties and the general nature in which they were conducted. Of

Sadguru Sai Shankar. I cannot say that my first impression

was the best but within an incredibly short span, there was a

complete upheaval of my mind towards the father-figure in

every sense of the term. At present I would not believe if

anyone told me that on the first meeting I had evinced doubt

To clear my doubts about the reality of Sadguru Sai

Shankar, I approached Sri P. G. Kuttappa who, incidentally,

gave up a lucrative executive job in a foreign Tea Company to

become Sadguru Sai Shankar’s first disciple. He told me that

Sri A. T. Kariappa, in whom the power of Lord Shankar has

assumed the role of Sadguru Sai Shankar using the figure of

Sri A. T. Kariappa as His instrument, was, to begin with, a

j^in basically shy and an introvert by nature. He attributed

changes in the personality of Sri A. T. Kariappa and all

the activities that centred around him, which was drawing

people from all walks of life, to the manifest power of Lord

Shankar as an inner voice within him, starting from September

18, 1967. He further stated that it was in recognition of this

great truth that he had chosen to give up his vocation and

come to stay close to Sadguru Sai Shankar so that he could

thoroughly purify himself by acquiring ihe knowledge of the

self from Sadguru Sai Shankar and thereafter offer himself to

he used in whatever manner the power of Lord Shankar deemed

fit. This statement was indeed thought provoking and I

realised that the figure of Sri Kariappa was only an instrument

of the Lord to give guidance and salvation to the various

people who gathered around him seeking the same.

2

3

After hearing the guidances of Sadguru Sai Shankar, I

realised that the power of ‘Iness’ and ‘Myness’ should be

annihilated totally which in turn brings about co-operative

thinking and living built upon the base of simplicity and

humility which is in itself love, which again in itself is God.

The root cause of my base mode of life, I came to realise,

had to be done away with. In the past I was made to give up

drinking, smoking, etc., against my will and hence always

had the incumbent desire to revert to the old habits after a

period of time. In this case, the very initiative to give up

sensual pleasures of drinking, smoking, etc , and the total

desire to make a completely new image that fully reflects every

word and deed had come from within. This inner urge to be

good, to see good and do good was kindled by the guidance

imparted by Sadguru Sai Shankar. The subtle nature of the

mind and the pranks it plays on an individual makes a person

take off at a tangent finally leaving the body unaware of how

it came to be doing what it is doing. Simple self-control

methods by Namasmarana (mentally chanting the chosen

name of the Lord), Satsangha (good company), meditation,

introspection, bhajans, etc., prescribed by Sadguru Sai

Shankar has made me what could be termed “aware of

myself” which in itself is a great step taken closer to the

Lord.

During my sojourns through the various parts of the

country, I happened to visit a couple of ashrams and listen

to lectures and discourses by eminent scholars but none of

them had come close to making anyone of the listeners of

their lectures put into practice their sayings. But here I

found that you are not only shown the right path but are told

in more ways than one, how to implement the plan and

practice it in the work-a-day world. Total renunciation of

family life is not advocated whereas it is imbibed into you

that the life of a householder can go hand in hand with a

totally dedicated and spiritual life.

The root cause of ‘Iness’ and ‘Myness’ complex which

essentially stems from basic ‘attachments’ to a certain person,

place or thing if eradicated leads to a life of simplicity,

humility and peace of mind which mankind longs for. The

attainment of this wisdom, Sadguru Sai Shankar explains in

simple terms, that action, work and duty all seem such a

pleasure to perform when the goal to achieve is such a beauti

ful prize.

I am now staying under the fold of Sadguru Sai Shankar

with the purpose of perfecting the art of living a worldly life

and doing one’s duty in the society based on spiritual

principles without having to renounce worldly possessions.

After coming to Sadguru Sai Shankar, I feel that all the

money wasted by me in the pursuit of my sensual pleasures

could have been used for helping the needy by way of provi

ding food, clothing, medical aid, shelter, educational facilities

and drinking water amenities all of which form the main

activities that are being undertaken by my friend Sri Pratap

Chittiappa, who earlier was also wasting money for no

constructive purposes. This radical change in him only

follows the change of his behaviour towards his parents

whom he used to grossly disrespect and to whom he now

owes allegiance, and has utmost respect for. This former

atheist to believe that the Supreme Power of Lord Shankar

is manifest and also his radical change in attitude to life, I

can now believe, could not have been effected by anyone other

than the Lord himself.

After rational thinking and intensive enquiry, I have

realised that the form and the embodied Supreme Spirit are

two separate entities and it is the voice of Supreme Spirit that

I take to be my spiritual guru. It is therefore evident that

if it is not for the manifestation of the Supreme Spirit,

imyself and other educated youngsters will have no reason to

take any guidance from Sri A. T. Kariappa who had studied

upto S. S. L. C. and had only meagre worldly experience.

A. R. PATRO

Follower of SADGURU SAI SHANKAR

Spiritual Guidance Nilayam

Thithimathi Post, South Coorg

Karnataka State

10-4-77

I write this to bring out mainly the reality that I found

centred around all the words and deeds that I have seen,

heard and experienced practically of the nature, being and

self that is Sadguru Sai Shankar so that anyone of you who

read this and are at present deluded by the present way of life

based on fleeting values and so desire to re-orient your way

of life, I put down my humble experiences.

—A. R. PATRO

5

COORO PRINTING PRESS, BANGALORE-3

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

326, V Main, I Block

BaZaY"9'X

VISHWA YUVAX KENDRA

NEW DELHI

’

Bangalore-560034

India

SEMINAR ON VALUE ORIENTATION TN HUMAN PROBLEM SOLVING

(NEW DELHI - MARCH 11,

12 and 13.

1982)

Sponsored by : Vivekananda Nidhi, Calcutta

•

and

Vishwa Yuvak Kendra

KEYNOTE BY SWAMI YUKTANANDA

At the outset, may I express my cordial feelings and gratitude

to Vishwa*Yuvak Kendra, and to Dr. K.V. Sridharan in parti

cular for having accepted Vivekananda Nidhi as joint sponsor

of this seminar on Value Orientation in Human Problem Solving.

It is a privilege to address.this assembly of eminent people

participating in the seminar .because of the common concern

for value identification and its orientation towards bringing

in attitudinal changes in people which will improve the

quality of life and also the environment.

2.

Areas for deliberation:

The organisers have selected four areas for the deliberations

with a view to drawing conclusions and preparing action pro

grammes which can be implemented, viz.' Value .Orientation in

1.. cultural interaction

3.

2.

social behaviour

3.

upbringing of children

4.

fighting poverty

Target - priority group z

When the value' orientation movement was initiated, decision

making agencies and media people were recognised as the target

group.

The priority was fixed on the rationale that as a

consequence of the over-growing structured socio-environmental

system, the control over most aspects of human existence is

now consolidated in a small number of decision-making agencies

comprising Governments, Corporate Bodies, Political Parties,

Trade Unions, Communication Controllers, Gurus (religious

leaders) etc.

In such a situation, parochial interests,

errors in judgement or any irresponsible action on the part

of one or more of these agencies could cause irreparable

damage to all human endeavour instantaneously or in a slow

process.

The decision-making people- therefore, have to be

aware of value systems, of the absolute component in them,

as well as of. the components which vary with time and place

and social condition.

4.

■ ■

Value_Orientation:

4.1.When the question of Value Orientation arises in any context,

there are two basic elements to be considered: the valuer,

and the value-referent.

For our present discussion man is the

valuer, and thp value referent is the object, event, process

or condition that forms the experiential locus of value con

cern.

A definition of value places clear emphasis either on

the attitude of the valuer of upon the value referent.

In

the first case we speak of man holding or entertaining values

and in the second of objects, events, etc. having values.

It is significant that the basic human values such as love,

truth, etc., remain-indivisible even though application takes

various behavioural forms.

4.2

The concept of value is essentially behavioural.

A value when

'accepted by society in action is transformed into a social oi

behavioural norm, i,e. orientation does take place.

A value

not accepted, is not transformed into a norm, remains sub

jective and speculative, a mere conjecture or reverie.

4-3

In effect therefore, values mean a commitment to the expen

diture of time, effort ano/or other resources in appropriate

circumstances ir order to achieve ar objective relevant to

some, experiential referent.

In this context, what is to be

emphasised is attribution of value.

For, in a given situation

it is what will make a difference in the behavioural response

and condition of the valuer,

thereby modulating the outcome.

The valuer agrees directly or indirectly to contribute time

and energy or to make the resources at his disposal available

: 4 \

to his fellow beings in their efforts to bring about the

desired state of affairs.

Without this commitment, value ori

entation is an exercise in futility.

It may be assumed that value commitments are implemented

when the

circumstances are appropriate.

It is also true

that the appropriateness of the value-directed behaviour

depends upon the experiential context.

In this view, value is not in any way a property of the refe

rent.

Of course, this does not mean that the view of those

who consider value as a property is absolutely incorrect.

My contention is that the properties of the value referent

are irrelevant to the selected subjects for our discussion.

Values_-_gratificatory ,_unconditional_and_conditional :

In practical terms, we are prepared to accept an activity

as value-directed and make investments in terms of time,

effort and/or other resources; even self-restraint, provided

we obtain some gratification out of the investment or sacri

fice.

If the pursuit does not produce satisfaction or grati

fication .for us, the valuers, we do not usually accept it as

value-directed. ■ This is so because the expected satisfaction

or gratification motivates our behaviour, conscious and con

nate, and imparts meaning and purpose to our existence.

gratificatory values may be unconditional or conditional.

The

: 5

5.2

Unconditional gratificatory yalucs are those which are impe

rative or compulsive irrespective of the sacrifice involved

or the consequence.

Their sources are rigid ethnocentric

beliefs and practices the tradition-bound society dictating

what is good or holy or political*' rigidity.

Such values are

enforced by custom, ritual and social indoctrination.

The

enforcement is supported by selective interpretation of myths

and legends and further strengthened by ceremonies and festi

vals.

In this way unconditional gratificatory values are

institutionalised, inhibiting change and always act as the

motivating force behind struggles to maintain the status-quo;

Because these values are quite unrelated to the experiential

aspect, fresh experiences in altered situations cannot bring

about any modification or correction in their behavioural or

attitudinal components.

Individual emotional experiences such

as insecurity and frustration when of great intensity can

generate similar attitudes.

These result in a loss of flexi

bility and receptivity in the respc ise to experience and a

consequent immunity to modification.

It is possible to replace

myth and legend by objective reasoning in the minds of people,

but the after-effects of emotional experience are not so

amenable.

5.3

From the individual this may be an influence affecting a

larger section of people when the condition is common to

them as in a war, large-scale unemployment or political

instability.

5.4

There is of course the possibility of intense emotional

experience beinq th# cause of fresh unconditional gratifi-

catory values which loosen the hold of the established values

upon the personality of an individual.

In such a situation,

transmission of unconditional gratificatory values from

one generation to the next stops and the result is generation

gap.

5.5

Next to be considered are conditional gratificatory values,

so termed because they are not so compulsive or imperative

as to stop individuals absolutely from pursuing other inte

rests and concerns.

Conditional gratificatory values are

hot looked upon as beyond reasoning.

They can be judged on

the basis of their consequences, which fact effectively pro

duces a control over their influence,

Bei.,g flexible, con

ditional gratificatory values are modified by the assessment

of a given situ ition and the anticipated consequences.

Unlike the unconditional gratificatory values, conditional

values by virtue of their flexibility and adaptability,

allow

themselves to be intellectually organised and to be pursued

by choice, provided the circumstances are such that fixed

habits and rigid customs are not functional.

Conditional gratificetory values are also transmitted from

generation to generation, thus becoming a part of the heri

tage of a society.

There are however, among these values,

some which are born of personal experienc.-. end which do not

survive longer than the life of the individual entertaining

them.

They vary with location, occupation, status etc.,

but those which form part of the heritage are usually acce

pted by the people unawares.

To free our society from the false view of the absoluteness

of unconditional

gratificatory.values,

the most effective

means is a constant and alert exercise of the intellectual

faculties so as to affect a devaluation of all extra-expe

riential considerations in thought and behaviour.

Technolo

gical progress and interaction between different cultures

do bring about social changes which gradually make the esta

blished unconditional gratificatory values■irrelevant, and

without going into the reason behind the cnange, a noise is

raised that values are eroding.

Atxthis point, of course,

there is always an apprehension of new ones being created by

emotional disturbances in individuals and groups.

Though

these cannot by their very nature las.t long, they can give

rise to cults or erratic social behaviour and such other

deviations which may persist for some time, afterwards but

eventually die. out.

So-called value erosion or birth of

cults have nothing with absolute values inherent in man.

: 8 :

5.7

It is a matter of utmost urgency that the minds of decision-making people be made fre . of unconditional gratificatory

values, if the scientific and-technological advancement in

our times is to be fully utilised for the benefit of-mankind.

5.8

Now that this whole planet of curs has effectively become one

neighbourhood and pluralism in the rield of changing man

made values inevitable, we are required to identify the

conditional gratificatory values of greater flexibility in

thought and behaviour, based on the dignity of the indivi

dual, and providing .scope for tolerance of the values of

fellow beings.

This will be a slow .process no doubt, but

imperative for survival.

6.

6.1

Value concerns and change,_and_dynamics_of_improvement :

This flexible approach and the pluralistic view of values

does not in any way mean•acceptance of any kind of permi

ssiveness or disintegration of social value concerns or of

anything damaging to some common purpose.

The point is that

change of sociax value concerns is inevitable, that they

cannot forcibly be made to stay based on unconditional grati

ficatory values ...

6.2

On the basis of what I have submitted to you, we can now .

refer to the four chapters for discussion and see how value

orientation can provide the dynamics of improvement in these

9

four fields.

Values whether unconditional or conditioiiar ’gratifies tory

are derived from some fundamental ideas drawn from the

metaphysical component of human heritage and culture, and

supported by the findings of science.

Political ideology

and religious faith are both founded on these two factors..

Till before the advent of quantum mechanics and the theory

of relativity, a large part of human civilisation oriented

its beliefs,

faith, norms and political concepts on the

mechanistic world view.

Now that science has replaced this

by a holistic world view, it is high time that the clutter

of notions in our minds is cleared up, and we freed ourselves

from the hold of unconditional gratificatory valu systems

to replace them by a conditional gratificatory value system

sanctioned by objective reasoning, based on the insepara

bility of things, events and consciousness--and on the denial

of cessation of existence.

Once we accept the oneness of

the cosmos of which the individual and the world are compo

nents, most of the problems mankind is facing in its efforts

to reach individual and collective fulfilment disappear.

A completely fresh approach to social behaviour, political

ethics and religious pursuits is opened up.

is value orientation.

This, I submit

I shall indicate briefly its impli^

cation in the four fields chosen for discussion.

s 10 s

I.

Value Orientation in Cultural Interaction: -

While working-to preserve the imiqueiw o' one's own

culture, a?1 other cultures ar.

required to accept the

inevitability of interaction with other cultures,

without denouncing any, or attempting to destroy anothe;

culture for the supposed benefit to one's own.

II.

Value Orientation in Social Behaviour :-

The social system is inclusive of all without exception

and alienation or isolation of individuals or grouos

is a contradiction.

The economic system is not a means

for instant gratification of needs or desires but pro

vides a frame-work for living together on the basis of

mutual trust, interdependence and communication.

Ill.Value Orientation in the upbringing of children:-

This is the most sensitive and vital

range of the deliberations.

part within the

It is so because of the

fact that even before the human mind is formed,

fixation t. kes place.

loyalty

'What type of a person the infant

will develop into is to a large extent pre-determined

by the physical and social environment in which the

infant grows.

/

The home and the parents are the primary

contributory factors to the development of the adult

from the infant.

The problem here is that the adults

who create the infant's environment have already acquired

loyalty fixation.

However, acquired conviction in a

value system (which is also socially acceptable)

and

commitment to it can bring about a re-orientation of

attitudes.

It is a great responsibility which does

not admit compromises if we desire a better society.

IV.

Value Orientation in fighting ooverty :-

This has to do with the ultimate aim of value orientati.:r

which is character building.

Truly to fight poverty to

the finish, we have to include in its definition not

only

material poverty but also poverty of the inte

llect, of emotions and power of action.

For it has

become increasingly clear that in any scheme for eco

nomic uplift of any kind of development whatsoever, we

are not deriving the expected output from more than

adequate input in the form of investment, . infrastructure,

technically created planning etc. .'.This is-true 'not only

on the national scene but also.-'on the global level.

Something is amiss somewhere.

It is not difficult to

identify the defect as lying in the performance of

the human component in implementing plans.

If the

individual or group responsible for implementing any

programme is not receptive to the value system as the

dynamics of planning, not only is development retarded

5 12 :

but antivalues grow and result in insincerity, indisci

pline, and corruption becomes institutionalised.

awareness c E values need to be

An

created in people who

form public opinion, in order to reverse the effects.

This requires the initiation of a massive movement in

the field of value systems.

6.5

It is, of cours'te, not only in these four areas, but in ever

field of human pursuits, value orientation in terms of the

changing'values and the enduring ones is imperative.

By

changing values and enduring values I mean, by the former

unconditional and conditional gratificatory values and by

the latter the fundamentals of the value system, i.e.

metaphysical and scientific truth.

6.6

There are other classes of values as perfunctory values and

instrumental values, but for our present purposes it is not

necessary to go into them.

7.

Value_directed action :

In conclusion, I humbly draw your attention to the urgency

of our taking some positive steps;

1.

to develop convictions regarding the enduring values

as found by physics and metaphysics; a holistic world

13 :

view in which the- valuer and the valued are rnanifes ca

tions of the same existence.

2.

to define the situation, iden ify the location of

the individual, find the role-identity of the indivi

dual, and its relation to collective existence and

to acknowledge the reciprocity of obligation.

3.

to accept value-commitment in playing our mutual

roles.

4.

to be aware of the interdependence of individual

humans, of individuals and the ecosystem, and their

interrelation.

5.

to evolve work programmes to achieve these objectives,

which will also make value orientation a shared expe

rience; to take part in various development and

service projects with a view to making them value- ,

directed.

V’ <+-

THB INDIAN IDBOLOG'!Remarks

Defence;-of the Caste System 3

India’s caste system may be one of the most inhuman social

systems of the world. With its thousand and one precepts and

prohibitions, the caste has been able to regulate the minute

details of the individuals life, erect walls between man and man

and;condemn large sections of the people to inhuman conditions

of life. The caste is no doubt the result of a complex historical

pro,cess, and racial,, cultural, economic, geographical and

political facotrs have gone into making of it. Caste difference

is not identical with,..class difference, but it is doubtful

if caste discrimination could have flourished so long and gone

to such lengths .without-, the backing of socio-economic and poli

tical power and the ideology*’, which it produced to legitimize

and stabilize the whole thing. There are certain basic beliefs

and dogmas that gave the system the status of a natural or

divine institution, made-its observance a religious duty, and

immunised it against criticism. These seem to constitute the

me st imoortant ideological. jeonoonent of Indian thought 5 indeed

they may be said' to' make up the Indian ideology.

Though there, .are statements that:favour or justify caste

discrimination in several books of the Hindu Sruti, the most

typical expression of the caste ic’bology may be found in the-Hindu

law-books the Dharma- Sastras. The purpose of thi-s short article

is tc draw attention to the ideological character of Manava-Dharma

Sastra or.of Hindu-laws.■The oxtert Menu smriti attributed tc

the mythical personage Manu,.is a collective work and dates back

at least to the early centuries oi

>ur-era. It contains laws and

regulations that might have originited in different times and in

different communities .standing of JJjhu smrti would require the

.investigation of origin, developme r; and codification of the

different traditions in terms of t.u

dialectics and -beliefs and

life-interests. Such a study is st:

1 outstanding and I do not

presume to bo qualified to..-make a h ■ ginning in the direction.

Therefore, I shall consider the extd at Manava Dharma sastra as

it has been there for centuries, influencing the life and

thought of generations of Indians,

’.eluding those muslims '

and Christian o; n, crt.f f_ cm l.induis».i who are hindu atleast in

this rospecie

2

- 2

The way the word Dharma is usually understood betrays a

basically conservative tendency. For Dharma refers not only to

those rules and laws that regulate man's conduct, social and

individual, it refers also and above all to the cosmic law, rta.

In fact it is in virtue of its being the law of being or the

law of the world that Dharma becomes the law of Man's life and

conduct."The pattern of the laws of behaviour corresponds with

the pattern of the laws of being". True, the laws of behaviour

have or should have something to do with the reality of Man's

life and the world. But to make this a matter of ontological

correspondence would raiso historically conditioned laws and

regulations to a cosmic or ontological status and give them an

absolute, metaphysical quality. It is not surprising in this

context Dharma viewed as eternal, sanatana, and that ones duty,

svadharma, is determined by what one is by birth rather than

through decision. In this way of thinking, what, is sat, is

good; what is not, asat, is bad.. One's duty is to be what one is

ot to become aware of what one is.

It is not realized that what is, is often not as it can or should

be, and thus what is, is not necessarily good. One the contrary,

it may be bad and in this case, what is not, would be the good

man can and should strive for, and this would imply criticism,

change or overthrow of the existing situation rather than conformity

with it. One attains one's true self not simply by being what one

is not, by change, revolution, metanoia.

The truth of our

being consists not so much in knowing what we are but in realizing

what we can be and thus are not. This realization is, of course,

not independent of what we are

a

but dialectically related to it.

The upanisadic, tat tvam asi would in this light have to be as much

a matter of praxis, karma, as of theory jnana. Such an approach

can hardly accept doing a 'duty' that is found to be devoid of

merit rather than one that is found to be good; it would rather

challenge or overthrow a duty, dharma, that is less than good,

and not submit to it merely:because it is said to be one's duty,

svadharma•

The fact that one's dharma is essentially varnasrama-dhrama binds

man to the role he has to play according to his birth and age.

We cannot enter here into the enslavement this means to the

individual's free self-rea.lization, whatever caste one may belong

to. Our concern is rather the way this compartmentalize the

society, erected a rigidly hierarchical social system and

3

- 3 favoured tha oppression and exploitation of the large sections

of the population in the name of religion and morality. For if

the oaste system is something natural and God given, its

inequality and discrimination are not wrong. On the contrary

man is bound to approach (accept) them willingly, without .protest.

It is in this light that we should understand Manu’s repeated

stress on the divine authority of what he says : ’In order to

clearly settle his (i.e. the Brahmana’s) duties and those of the

castes according to the order, wise Manu sprung from the Self-

existent, composed these Institutes (of the sacred Law)*.

(1*102) The brahman is to study and teach them (v• 104)"and if

he does fulfill its injunctions ’he is never tainted by sins,

arising from thoughts, words or deeds’ but will secure welfare,

learning, fame and supreme bliss (V. 106 *CF*10*131) "In this

(work) the sacred law has been fully stated -as well as the good

and bad qualities of (human) actions and immemorial rule of

conduct to be followed by all the "four castes".

(1»1O7) This

rule of conduct corresponds to or follows from the order of

creation. "But for the prosperity of1the worlds, he caused the

Brahmana, Ksatriya, the Vaisya,' and the Sudra, to proceed from

his mouth, his arms, his thighs and his feet". (1»31) Manu

describes in detail the duties and occupations of the four castes,

varnas, brahmans (priests and teachers) Ksatr-iyas (warriors,

princes) Vaisyas (peasants and traders) 'and Sudras (servants)

(1587-91) of these the first three castes are twice born,

dvijas, whereas the sudras have only one birth(lO54). All others

are outside the pale of system (ibid). They are outcastes, avarnas

and as such are not born from the four parts of the deity (1O.j45)

Divinely instituted as they are, the caste duties are absolutely

binding. Those members of the four castes relinquishing their

proper occupations except in case of distress are to become servants

or dasyus, after having passed through despicable bodies (12*70^0.

F W 71-72) It goes without saying that this must have been a

powerful incentive to observe the caste duties. It facilitated the

acceptance of intolerable living conditions without criticism and

protest. For if the evils of the present life are the consequences

of one’s own actions in a past life, karma, there is no use in

criticism or protest.

All that one can do is to boar them

patiently and hope for a hotter life next time. As if this other

worldly sanctions were not enough Manu enjoins the king to soe

that the caste duties are observed by all (7*35)•

- 4 Manu interprets the story of man's origin in tho rigvodic

purusasukta in such a way as to establish the superiority of

those higher up in the social ladder as something divinely

instituted and therefore immutable. ’Man is stated to be pure above

the naval (than below hence the Self-oxistent (Svayambu) has decl

ared the purest (part) of him (to bo) the mouth" (1:92)

"As the Brahmana sprang from (Brahman’s) Mouth, asho was the

first born, and as he possess the veda, ho is by right the lord

of ell creation (V.93). As R G Zaohnor points out, seldom in the

history of the world has a class of man arrogated to themselves

such powers and previliges and such honour as the Brahmins of India:"

Of created beings the most excellent are said to have those

which are animated of the animated, those which subsist by inte

lligence; of the intellegent mankind; and of men Brahnanas;

The very birth of a brahmana is an eternal incarnation of the

sacred law; for ho is born to fulfill the sacred law, and becomes

one with Brahman. A Brahmana coming into existence, is

born

as the highest on earth, the lord of all created beings, for the

protection of tho treasury of the law. Whatever exists in the

world is the property of the Brahmana is indeed, entitled to all.

The Brahnanas eats but his interest on food wears but his own

apparel, bestows .but his own alms; other mortals subsit through

tho benevolence of Brahmana" (1;96-1O1)" By his origin alone a

brahmanais a dioty even for the gods, and (his teaching is-

authoritative for men, because tho veda is the foundation for that".

(11:85) No wonder if the-'gods on earth bhudevas or bhusuras, could

lay claim to all sorts of rights and previliges. And the oridinary

mortals were naturally reluctant to refuse what the brahman sought

Some of Manu’s ordinances arc meant to assure the priestly.classes

the means of substonance without undue care. So is also tho

injunction that Brahmin is not to take, up other occupations

except in case of distress. (4:2-7) As proceeds, however, to lay

down what brahraan should do or avoid, the legislation becomes

strange and self-interested. For Instance, the brahmin is asked

to take care not to unduly fatigue his body" (4:3) ho is to avcid

at all costs serving others, the only occupation allowed to tho

sudras, as service is in roality the 'dog's mode of life',

svnvriti (w.4-6) Agriculture is either strictly forbidden or

allowed with great reluctance. For manu fears that the Brahman, enga

ging in agriculture would have to injure the earth and tho beings

living in it, while ploughing (3Z:64:10.82 :83-83) if this is the

case, it may bo asked how brahmans came to be such monied and.

landed class, which they are even now for tho m. st part.

5

- 5 Some of manu’s ordinance indicate the direction in -which an

answer may be sought. Manu exhorts the king to give liberally to

learned Brahaanas "The king shall offer various (srauta)

sacrifices at which liberal fees are distributed, and in order

to acquire merit, he shall give Brahaanas enjoyment and wealth,

(7 i'(3 JCF also VV37-38) A gift made to a Brahmana is never lost

(WS82-83) Indeed it is better than agnihotra the sacrifice to

the God of fire. (Vs85). "An offering made through the mouth of

fire of Brahmanas rich in sacred learning and austerities, saves

from misfortune and from great guilt" (3598) while "a Brahmana

who stays unhonoured (in the he use) takes away with him all the

spiritual merit" of the householder (v.100) Honouring the Brahsanis

said to be one.'.of the best means for a king to secure happiness

(7s88).

The knowledge governing interest of these statements is

evident. Squally obvious is the effect it would have on pious

sould. History bears witness to tho importance Indian princes

and aristocracy attached to brahmadana, the bestowing gifts on

brahmins in the form of gold and landed property. Manu ordains

that "on failure of all (heirs) brahmanas shall share the estate"

(9s 188) while, the- property of a brahmana shall never be taken

by a Kind" he may do this only in the case of ether castes (VSI89)

The Brahman may take an article necessary for the completion of

a sacrifice, from a vaisya (l1:11-12)ho "may take at pleasure

two or three articles (required for tho sacrifice) from the house

'of a sudra5 for a sudra has no business with sacrifices" (Vs13)

But manu is careful to warn that this may be done only under a

"righteous King" (v.11) and he advises tho "righteous kind" not

to xnflidt punishment on tho brahman for doing so" for (in that

case) the Brahmana pines with hunger through the Ksatriya's want

of care" (v.21) The Ksatriya, on the contrary, must never take

the property of a brahmanj when starving, ho may take tho property

of a dasyu, or of one who neglects his sacred duties (Vs18).

In the same way Brahmans are to be exempted from punishments

which ordinary mortals are liable to. His dignity immunises him

against all capital puiiishnont, "No greater crime is known on

earth than slaying a Brahmaha; a king must not oven conceive in his

mind the thought of killing a Brahmana" (8J399) Whatever crimes

he may have committed, ho may only bo banished from tho kingdom,

and that "leaving all his property (to horn) and his body unhurt"

(v:380) Based as it is on tho•fundamental inequality of men, tho

caste-based laws are to bo applied differently to different jatis

and varnas. It is only after the British introduced their laws in

India that the fundamental equality of all in civil matters was

6

-6 at least theori-rtically admitted. While the killing of a brahman

constituted a severe offence Mahapataka, the killing of a va?isya,

or a sudra was a minor offence, upapataka (9:235:11|55 and 11:67).

This is the case with giving pain to brahman by a blow; as a

.Eimr offence, it was to cause the less of caste, jatibhramsa?

(11:68). To be sure tho Mahapataka demanded more severe penances

after death than the upapataka. The slayer of a Brahman will have

to enter the womb of a dog, a pig, a chandala, a pukkaso etc.

( 12:55)."

A twice-born man who has merely threatened a

brahmana

with the intention of (doing him ) corporal injury, will wander

about a hundred years in the Tamisra hell". (4:165) The inten

tional striking of a brahman even with a blade of grass will have

to be attoned for by passing through twenty one existences

(V:166;GF.W:167-169).

It is natural that community of men endowed with such divine and

human perogatives despise and exclude the others. Manu draws .

long lists of .those to be despised and excluded by the twice-born.

especially the brahman. Numerous professions,

lot to speak of

ordinary labour, are qualified as impure, and those engaged in

them are condemned to.be putcastes (3:155-166). The twice born

are adviced to. avoid these lost they should themselves bo reduced

to tho category of outcastes and condemned to despicable births

afterwards . Even the other two categories of the twice born, i .©.

Ksatriyas. and vaisyas, are not pure nor noble enough for the

brahman. He may not treat the ksatriyas visiting him as a guest,

atithi, and may feed him only after the guests, proper, i.e0

, bfahman may feed him only with his servants ’showing (thereby)

.

his compassionate disposition". (V.112).

If this is the case with Ksatriyas and vaisyas on whose protection

and patronage the brahmin’s well-being largely depended, the

condition of the sutra can be imagined. Born of the deity’s 'feet,

the sudra is in Manu’s view a slave or domestic servant of the

twice-born, especially the brahman. "One occupation only the lord

prescribed for, sudra to serve meekly even these (other) three

castes." (1:91)" But let a sudra serve brahmanas, either for

the sake of heaven or with a view to both (this life and the next

life) for he who is called a servant of Brahmana thereby gains

all his ends. The service of brahmanas alono is declared (;'t6~be)

an excellent occupation for a sudra; for whatever else besides

this he may perform will bear him no fruit. (10:122-123). The

king is asked to order the sudra to serve the brahman(8:41 O)"

But a sudra whether bought or unbought the (brahmana) may compel

7

7

to do servile -works for he was created by the self-oxistent

(Syayambhu) to be the slave of a Brahmana" (V:413) manu cannot

even imagine how a sudra can be frees "A sudra though emancipated

by his master, is not released from servitude since that is

innate to him, who can set him free from it ?" (V:4l4)

In another

place, the interest behind this emphasis on the servile nature

of the sudra is somewhat naively admitted:" No collection of

wealth must be made by a sudra even though he may be able (to do

it) for a sudra who has acquired wealth gives pain to Brahmanas"

(10:129)

In contrast to the other three varans, the sudra is net entitled

to the sacred initiation, ho has to be satisfied with one birth

(10:4) Besides, the sudra is forbidden to study the Veda(j:156:

4:99s10s127) and he is not to be instructed by the brahman(4:80)".

For he who explains the sacred law (to a sudra) or dictates to him a

penence, will sink with that (man) into'the hell (called)

Asamyrta" (V.:81 ) Indued the sudra is so low that "ho cannot

commit an offence, causing the loss of caste (pataka) and ho is

not worthy to receive sacraments; ho has no right to (fulfill)

the sgcrod law ( of the Aryans, yet) there is no prohibition

against (his fulfilling certain portions of the law)" (10:126)

Evon a brahman who has nothing but his name may interpret the

law to the king," but never a sudra" (8:20:CF also V:21). Manu

oven.contends that the presence of many sudras is enough to destroy

a kingdom (v.22). However inhuman and servile his duties may bo

the sudra is bound to fulfill them, as he is created by God for that

purpose and as disobdienco will moan punishment in the next birth(s)

Manu says that the sudra neglecting his duty will bo reborn as a

ghost feeding on moths (8:4l4).

The inhumanity of caste system is most evident in the treatment

meted out to those sections of the population the upper classes call

out castes, avarnas. Manu defines them as "those tribes ifi the

world, which are excluded from (tho community of) those born from

the mouth, arms, the thighs, and the feet of tho (brahman)"

(10.45). The fact that they are called Dasyus, and are said to

speak either the language of the riLecchas or that of tho Aryans (ibid)

seems to point to racial differences that might have been, atloast

partly, responsible for their segregation. However, it is not

likely that all these communities are the result of mixed marriages

between tho different castes and those outside, as Manu contends

(10:7-49)* Whatever that may be, they are all "base-born) apasada,

subsits by and are enjoined to "subsist by occupations reprehended

8

8

by tho twice-born" (10:46). And those groups include not only

butchers and fishors and cobblcrsbut also carpenters, drunisors,

horse-breeders and chariot rankers (W:46-49). They are to live near

well-known trees, burial, grounds, and on mountains (V:50). What

makes their lot ail the more miserable is the fact that they aro

not only defactc dependent on socially despised occupations

but are bound to continue being so by the caste ideology (10:46)

Chandalas are to live outside the village, the vessels they

use are impure, and their only wealth shall be dogs and donkeys

(v.5l). Further "Their dress (shall be ) the garments of the

dead, ( they shall eat) their food from broken dishes, black

iron (shall be) their ornaments, and they must always wander

from place to place" (V.52) Tho authors of these regulations

if not also their practitioners" seems

to have has a measure of

sadistic 'pleasure in condemning other human beings to such in

human conditions.

In the eyes of the well to do, the poor and despised sections are

often also morally deprived. The way Manu describes an impure

caste -chows how the depressed classes arc stigmatized; "Behaviour

unworthy of an Aryan, harshness, cruelty, and habitual neglect

of duties betray in this world aman of impure origin" (10:58)

It would seem that the presence or absence of those vices is all

a matter of birth, whether one is born of brahman of chandala

parents. Tho base-born candala and pukksas are so polluting that

tho twice-born are asked to avoid them by all means. In

case a

brahman happens to touch a chandala he is to purify himself by a

bath (5^85) Indeed a brahman approaching a candala or a very low

caste woman or eats with such persons, will become himself an

outcasts (11:176) And infringing caste regulation meant', as we

a

have seen, also other worldly sanctions in the form of despicable

births and re-births. The only way to beatitude open to the outcastos

is to die "without the expectation of a reward, for tho sake of

brahmanas and cows, or in defence of women and children" (10:62)

It may not be said that all manu’s prescriptions and prohibitions

are meant to safeguard the interests of tho highorup in socio

religious hierarchy. They are not. But a good many of them soon

to serve the purpose, and quite a few statements betray an ex

plicit interest in legitimizing the status quo. This is all the

more evident in view of the fact that the twice-born, especially

tho brahmans, were for the most part responsible for both tho

making and interpretations of tho laws of dharma, wo have seen

how Manu enjoins that tho law be interpreted by brahmans and not

sudras.

9

9

On doubtful points of tho law, what good brahmans and sistas

profound is to have legal force, and good brahmans are those

who have studied the vodas and can adduce convincing procfs "from

the revealed texts" (12s108-109) In this respective, it is

natural that tho brahman interpret the law in such a way as to

protect and legitimize their rights and previleges.

That the underprevileged had no right on grounds of faith, to

study the scriptures, let alone interpret them, made it extremely

difficult, if not impossible, for the others to critize or chall

enge the brahmin's interpretations , True, some of Manu's extreme

claims may bo the expression of wishful thinking rather than of

reality. For instance, tho sudras wore not everywhere forced to

serve the brahmans, as Manu ordains 5 on tho contrary, there have .

been instances where tho brahman has to depend on the sudra. Yet,

much of what Manu says reflected tho social and political reality

of Indians life till recent times. There is no denying tho

religious apartheid that caste fostered and tho opportunities

it gave to the upper classes to oppress and exploit the masses of

tho working population in tho name of God and dharma. Wo may not

say this was made possible solely or mainly by the ideology of

varnasrama-dharma. But there can bo no doubt it has helped to

cement and perpetuate the division and difference's arising from

a complex of economic, political, racial, social, cultural and

geographical factors. It gave the subjugation and exploitation

of the poor and weak by those who came to yeild power and

influence the cover of respectability. Indued, it provided a

basically inhuman situation, a cosmic or divine legitimation so

that the previleged classes could enjoy their provilegos without

the prick of conscience and the underprevileged could accept their

suffering and servitude as something inevitable. Infact the caste

even now is a determining factor, in India's social and political

life. This makes tho uncovering and criticism of the caste ideology

a necessary stop on tho way to tho all round emancipation of

India's masses. But this is only a stop, and no more than that.

For emancipation has now to be above all economic, and this would

require a politics of development for all as well as tho elimina

tion of oppressive and exploitative structures. It would bo impo

ssible to achieve this end without tho organised action, es

pecially of tho sufferers themselves, cutting across tho

traditional barriers of religion and community. In this precess,

tho criticism of enslaving ideologies, whether religious,

cultural or social will form part of a theory of the new man

to bo realized by emancipatory praxis.

********

Jeevadhara (January - February 1976)

10

28-11-87/50

Position: 1140 (6 views)