RF_RJS_2_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_RJS_2_SUDHA

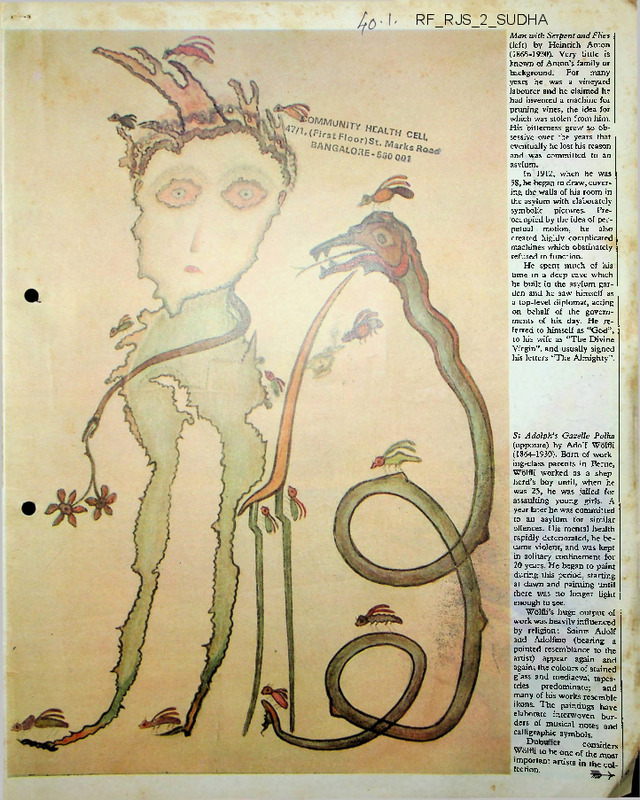

Man with Serpent and Flies

(left) by Heinrich Anton

(1865-1930). Very little is

known of Anton’s family or

background. For many

years he was a vineyard

labourer and he claimed he

had invented a machine for

pruning vines, the idea for

which was stolen from him.

His bitterness grew so ob

sessive over the years that

eventually he lost his reason

and. was committed to an

asylum.

In 1912, when he was

58, he began to draw, cover

ing the walls of his room in

the asylum with elaborately

symbolic pictures. Pre

occupied by the idea of per

petual motion, he also

created highly complicated

machines which obstinately

refused to function.

He spent much of his

time in a deep cave which

he built in the asylum gar

den and he saw himself as

a top-level diplomat, acting

on behalf of the govern

ments of his day. He re

ferred to himself as “God”,

to his wife as “The Divine

Virgin”, and usually signed

his letters “The Almighty”.

Sr Adolph’s Gazelle Polka

(opposite) by Adolf Wolfli

(1864-1930). Bom of work

ing-class parents in Berne,

Wolfli worked as a shep

herd’s boy until, when he

was 25, he was jailed for

assaulting young girls. A

. year later he was committed

to an asylum for similar

offences. His mental health

rapidly deteriorated, he be

came violent, and was kept

in solitary confinement for

20 years. He began to paint

during this period, starting

at dawn and painting until

there was no longer light

enough to see.

Wolfli’s huge output of

work was heavily influenced

by religion: Saints Adolf

and Adolfino (bearing a

pointed resemblance to the

artist) appear again and

again; the colours of stained

glass and mediaeval tapes

tries predominate;

and

many of his works resemble

ikons. The paintings have

elaborate interwoven bor

ders of musical notes and

calligraphic symbols.

W"SUbllket

considers

Wolfli to be one of the most

important artists in the col| lection.

3W 7"

Emile Hodinos-Josome, son of a Paris baker, was

trained as an engraver. Soon after cpmpleung his

military service he was committed to an-asylum

where he began drawing coins and medallions. His

intricate designs eventually covered thousands of

sheets of paper.

■

Gaston Duf, son of an alcoholic calif-owner in

northern France, started work as a minerih-his early

teens. Too unstable for such rigorous work, he was

dismissed from one colliery after another, becoming

more and more withdrawn and spending his time in

cinemas and cafes. When he was 20, Duf was com

mitted to an asylum, and made two suicide attempts.

He was periodically violent but began to spend hours

over his personal appearance, paying special atten

tion to his hairstyle, combing his hair in front of a

mirror for hours. He began to draw in 1948, always

depicting monsters, which he created with immense

conviction. He formed the habit of secreting litde

drawings, always done in black pencil, in his pockets

and carrying them with him wherever he went.

Although he can spell perfectly adequately, Duf cap

tions his drawings with seemingly deliberate mis

spellings (as above).

Laure’s drawings were contributed to the Compagnie by a membr of the Spiritualist circle to

which she had belonged. Around 500 drawings had

been found after her death, but there were no ex

planations as to the drawings’ meanings, and no clue

as to why she had done them. All are precisely dated,

indicating three distinct periods in her work. The

second period coincides with her husband’s leaving

her for another woman, and the third period dates

from the time of his return and death. AU Laure’s

drawings were executed with a blue baUpoint pen;

exquisitely delicate line-drawings weave a series of

elaborately filigreed patterns.

Two Chairs by Laure (1882-1965)

Jeanne’s sketch-books and diaries reveal a mass

Horses’ Heads by Jeanne (b. 1887)

of abstract drawings and messages from the spirit

world. The elder of her two sons died as a baby in

1913 and she has always consulted his spirit over any

important decision. One typical entry in a diary

reads: “WiU A ... help me to buy the coal for next

winter? If Yes, Horse’s Head.” “Yes.” An abstract

drawing of a horse’s head completes the page. Sig

nificantly, her pages proUferate with affirmative

horses’ heads. Jeanne was bom in southwest France

where she still lives with her husband, a retired

“ft- \f.

Medium Drawing by Raphael Lonne (b. 19i0)

Raphael Lonne is a postman in south west France,

where he plays in the local brass band. When he w*

40 he became intensely interested in spiritualism,

he firmly believes in reincarnation; he is also convinced

that he possesses supernatural powers. His drawings like the one above - were mostly produced between

1950 and 1951 and are remarkable for their fine linear

quality. Unable to explain their meaning, Lonne can

remember only that he did them, never how or why.

Guillaume was the youngest son of a French cabinetmaker. He was a serious and sensitive child, doted

K upon by his parents. He followed his father’s profession

BP even though his father had to sell up his own business

>n order to pay his gambling debts. Guillaume, who

was an obsessionally tidy young man, led a quite life

until the outbreak of the First World War, when he

HB was conscripted. When he returned to civilian life,

HI Guillaume quarrelled with his family, married, and took

; a job as a Customs clerk. His personality had undergone

L1- a profound and disconcerting change. He was tyrannical

Bn at home and almost impossible to work with. He began

BE to spend hours gazing at himself in mirrors and in

K 1926 attempted suicide. He invented a malevolent

Le Provence by Guillaume (b. 1893)

|■ daughter who persecuted him. At the age of 33 he was

|H committed to a psychiatric hospital. Nine years later

be began to produce his series of calligraphic paintings,

many of which were inspired by pictures from maga

zines. Working with brushes made from paper and

hair, he continued to paint until 1942. Now an infirm

old man, he is still living at the hospital.

Riverside scene by D. Guider

to create her wedding-dress.

developed pronounced schizo- • Made entirely from threads i

phrenic tendencies in middleage taken from worn-out sheetsand I

and in 1935 was admitted to a dish-cloths (no piece of actual

mental institution where he re fabric was ever used), and resem- |

mained until his death in '1950. bling the finest ’facework, Mar

Braz’s work reflects his’-'pro guerite’s wedding-dress is one

found sexual dilemma: it seems of the most beautiful exhibits.

that he was never able to deter Another artist in the Commine whether he was:"male or p'agnie was more interested in I

.female. The figures he' 'drew the delights in store after the I

.were invariably hermaphrodite: ceremony rather than in the

virile bearded men display vol preparations for the wedding.

uptuous breasts. Sexual symbo- ■ -Aloise (1886-1964), a governess

lism abounds: figures brandish in' France, was a spinster

obvious phallic emblems, and all her life. Each of her highly

animals (like the bull above) sensual paintings was given the

are aggressively potent.

" seal of respectability with an

initial depiction of a prim mar- I

Marguerite (1890-1957), daugh riage ceremony; thereafter she

ter of southern French peasants, shows herself in the arms of the

was admitted in her early forties chosen love - always an enor

’ to a mental hospital where she mously distinguished historical

_spent the rest of her life. A figure: Luther, Wellington,

““schizophrenic, she claimed that Napoleon and De Gaulle were a

“she had died 122 times. In her few on her roll of honour.

middle sixties Marguerite be

lieved herself to be 18 years old, D. Gui tier, who painted the river

and that she was to be married side scene (far left) was a schizo

on her 21st birthday. She sent phrenic. The picture was in a

The Wedding-dress, Marguerite wedding invitations and began psychiatrist’s collection. ^j>)) y

“5 T m

5U //0J72.

’ 'J

Ji7

THE MIND S EYE

„ ■ TJ^rTon^rimitive naintings

Next year a unique collection of . „

P,

and sculptures, the Compagnie de I’Art Brut, will move into a

permanent home being enthusiastically prepared for it by the

Swiss Government in the Chateau Brunel, Lausanne. The Com

pagnie is kept at present in a Parisian house belonging to the

French painter Jean Dubuffet, who began the collection in

1945. The French authorities would not provide the backing

for a permanent home because the collection consists entirely

of the work of non-professional artists. Most of them spring

from peasant or artisan stock and few showed any creative

promise until their middle years. A great many are under stress

of one form or another - frequently mentally or physically

handicapped - and many have spent much of their liyfes in

prison or mental institutions. To track them down Dubuffet

wrote thousands of letters to clinics, mental hospitals, prisons

and local authorities. Now the Compagnie is one of the bestpresented and most meticulously documented collections in

Europe. The Compagnie de I’Art Brut is not a pretentious

statement on art as therapy. The artists make their own point

with disturbing effect. By Roger Law and Celestine Dars

THE VISION OF THE PROPHET

The mysterious testami nt of Carlos Castaneda

The hottest literary property in

America - and certainly the most

elusive - is a Los Angeles anthro

pologist called Carlos Castaneda.

For 10 years Castaneda claims

to have been ‘apprentice’ to a

Yaqui Indian sorcerer whom he

calls Don Juan, and during that

time he recorded a series of extra

ordinary conversations with him.

The results, contained in three

best-selling books, have sparked

off a Castaneda cult in America,

though there is some scepticism

as to whether the mysterious

Don Juan actually exists. Casta

neda is almost as difficult to pin

down as his mentor. He has

shunned publicity, and coy pic

tures like the one below are the

only ones taken of him.

Castaneda gives us little infor

mation about Don Juan. We learn

that he was about 60 when they

met, that he was poor, lived near

Sonora, Mexico, and was a hun

ter by trade, a gatherer of plants

and animals. This explains why

he spent so much time with

Castaneda in the wilds.

Castaneda’s first book, The

Teachings of Don Juan, records

his efforts to wrest from the

Indian his knowledge of native

drugs. The second, A Separate

Reality tells how, after a lapse of

several years, he went back to

continue his apprenticeship, and

how his education progressed

beyond psychotropic experiences

into the problems of ‘seeing’. In

his last book Journey to Ixtlan

(just published by The Bodley

Head, at £2-25) from which we

print these extracts, he goes back

plants,” he said. “Talk until you lose

all sense of importance. Talk to them

until you can do it in front of others.

“Go to those hills over there and

practise by yourself.”

I asked if it was all right to talk

to the plants silently, in my mind.

He laughed and tapped my head.

“No!” he said. “You must talk

to them in a loud and clear voice if

you want them to answer you.”

I walked to the area in question,

laughing to myself about his eccen

tricities. I even tried to talk to the

plants, but my feeling of being

ludicrous was overpowering.

After what I thought was an

appropriate wait I. went back to

where Don Juan was. I had the cer

tainty that he knew I had not talked

to the plants.

■

■

He did not look at me. He sig

nalled me to sit do wn by him.

“Watch me carefully,” he said.

“I’m going to have a talk with my

little friend.”

He knelt down in front of a small

plant and for a few minutes he moved

and contorted his body, talking and

laughing.

I thought he was out of his mind.

“This little plant told me to tell

Losing self-importance

/‘Now we are concerned with losing

“elf-importance. As long as you feel

that you are the most important

thing in the world you cannot really

appreciate the world around you.

You are like a horse with blinkers,

all you see is yourself apart from

everything else.”

He examined me for a moment.

“I am going to talk to my little

friend here,” he said, pointing to a

small plant.

He knelt in front of it and began

to caress it and to talk to it. I did not

understand what he was saying at

first, but then he switched languages

and talked to the plant in Spanish.

He babbled inanities for a while.

Then he stood up.

lc"“It doesn’t matter what you say to

a plant,” he said. “You can just as

well make up words; what’s impor

tant is the feeling of liking it, and

treating it as an equal.”

He explained that a man who

gathers plants must apologise every

time for taking them and must assure

them that some day his own body

will serve as food for them.

“So, all in all, the plants and

ourselves are even,” he said. “Neither

we nor they are more or less impor

tant.

“Come on, talk to the little plant,”

he urged me. “Tell it that you don’t

feel important any more.”

I went as far as kneeling in front

of the plant but I could not bring

myself to speak to it. I felt ridiculous

and laughed. I was not angry, how

ever.

Don Juan patted me on the back

and said that it was all right, that at

least I had contained my temper.

“From now on talk to the little

COMMjNmY .; .ALTH CELL

47/1,(First Floor)St. Marks Aoad

over his earlier material and

retells his whole relationship with

Don Juan from the standpoint of

his new understanding.

In the end he realised that

drugs were beside the point. Don

Juan’s teaching was about ‘seeing’

the world rather than ‘looking’

at it. It was about stepping

through the thick veils of western

rationalism that enveloped Cas

taneda’s mind and blinded his

eyes. To understand Don Juan,

he had to find a new relationship

with everything about him.

you that she is good to eat,” he said

as he got up from his kneeling

position. “She said that a handful

like her would keep a man healthy.

She also said that there is a batch of

her kind growing over there.”

Don Juan pointed to an area on a

hillside perhaps two hundred yards

away.

“Let’s go and find out,” he said.

I laughed at his histrionics. I was

sure we would find the plants,

because he was an expert in the

terrain and knew where the edible

and medicinal plants were.

As we walked towards the area

in question he told me casually that

I should take notice of the plant

because it was both a food and a

medicine.

I asked him, half in jest, if the

plant had just told him that. He

stopped walking and examined me

with an air of disbelief. He shook his

head from side to side.

“Ah!” he exclaimed, laughing.

“Your cleverness makes you more

silly than I thought. How can the

little plant tell me now what I’ve

known all my life ?”

He proceeded then to explain

that he knew all along the different

properties of that specific plant, and

that the plant had just told him that

there was a batch of the same species

growing in the area he had pointed

to, and that she did not mind if he

told me that.

Upon arriving at the hillside I

found a whole cluster of the same

plants. I wanted to laugh but he did

not give me time. He wanted me to

thank the batch of plants. I felt

excruciatingly self-conscious ^j> >

This painting, by William Wiley, teas

originally designed as a cover for Time

Magazine to illustrate a story on

Carlos Castaneda, but was not used

and could not bring myself to do it.

He smiled benevolently and made

another of his cryptic statements.

He repeated it three or four times as

if to give me time to figure out its

meaning.

“The world around us is a

mystery,” he said. “And men are

no better than anything else. If a little

plant is generous with us we must

thank her, or perhaps she will not

let us go.”

The way he looked at me when

he said that gave me a chill. I hur

riedly leant over the plants and said,

“Thank you,” in a loud voice.

He began to laugh in controlled

and quiet spurts.

Death is an adviser

“The thing to do when you’re impn^nt,” he proceeded, “is to turn

to your left and ask advice from your

death. An immense amount of petti

ness is dropped if your death makes

a gesture to you, or if you catch a

glimpse of it, or if you just have the

feeling that your companion is there

watching you.”

He leant over again and whis

pered in my ear that if I turned to

my left suddenly, upon seeing his

signal, I could again see my death on

the boulder.

His eyes gave me an almost

imperceptible signal, but I did not

dare to look.

I told him that I believed him

and that he did not have to press the

^jue any further, because I was

terrified. He had one of his roaring

belly laughs.

He replied that the issue of our

death was never pressed far enough.

And I argued that it would be mean

ingless for me to dwell upon my

death, since such a thought would

only bring discomfort and fear.

“You’re full of crap!” he ex

claimed. “Death is the only wise

adviser that we have. Whenever you

feel, as you always do, that every

thing is going wrong and you’re

about to be annihilated, turn to your

death and ask if that is so. Your

death will tell you that you’re wrong

that nothing really matters outside

its touch. Your death will tell you,

‘I haven’t touched you yet.’ ”

“Of course we’re equals,” I said.

I was, naturally, being very con

descending. I felt very warm towards

him even though at times I did not

know what to do with him; yet I

still held in the back of my mind,

although I would never voice it, the

belief that I, being a university

student, a man of the sophisticated

Western world, was superior to an

Indian.

“No,” he said calmly, “we are

not.”

“Why, certainly we are,” I pro

tested.

“No,” he said in a soft voice.

“We are not equals. I am a hunter

and a warrior, and you are a pimp.”

We remained silent. I felt em

barrassed and could not think of

anything appropriate to say. I waited

for him to break the silence. Hours

went by. Don Juan became motion

less by degrees, until his body had

acquired a strange, almost frighten

ing rigidity; his silhouette became

difficult to make out as it got dark,

and finally when it was pitch black

around us he seemed to have merged

into the blackness of the stones. His

state of motionlessness was so total

that it was as if he did not exist any

longer.

It was midnight when I finally

realised that he could and would

stay motionless there in that wilder

ness, in those rocks, perhaps for ever

if he had to. His world of precise

acts and feelings and decisions was

indeed superior.

I quietly touched his arm and

tears flooded me.

A worthy opponent

Before I came to a sharp bend in the

road I encountered two other people

whom I did not recognise, but I

greeted them anyway. The blasting

sound of the record player was almost

as loud there on the road as it was

in front of the store. It was a dark

starless night, but the glare from the

store lights allowed me to have a

fairly good visual perception of my

surroundings. Bias’s house was very

near and I accelerated my pace. I

noticed then the dark shape of a

person, sitting or perhaps squatting

to my left, at the bend of the road.

I thought for an instant that it might

have been one of the people from the

Becoming a hunter

party who had left before I had. The

Don Juan watched my movements person seemed to be defecating on

the side of the road. That seemed

with apparent fascination.

“Well ... are we equals?” he odd. People in the community went

into the thick bushes to perform

asked.

their bodily functions. I thought that the game he was playing with me was

whoever it was in front of me must cruel.

“It would be cruel if this would

have been drunk.

I came to the bend and said, have happened to an average man.”

“Buenas noches.” The person an he said. “But the instant one begins

swered me with an eerie, gruff, in to live like a warrior, one is no

human howl. The hair on my body longer ordinary. Besides, I didn’t

literally stood on end. For a second find you a worthy opponent because

I was paralysed. Then I began to I want to play with you, or tease you,

walk fast. I took a quick glance. I saw or annoy you. A worthy opponent

that the dark silhouette had stood might spur you on; under the

up halfway; it was a woman. She was influence of an opponent like ‘la

stooped over, leaning forward; she Catalina’ you may have to make use

walked in that position for a few of everything I have taught you. You

yards and then she hopped. I began don’t have any other alternative.”

We were quiet for a while. His

to run, while the woman hopped like

a bird by my side, keeping up with words had aroused a tremendous

my speed. By the time I arrived at apprehension in me.

Bias’s house she was cutting in front

Disrupting the

of me and we had almost touched.

I leaped across a small dry ditch

^routinesoflif^^

in front of the house and crashed

We gathered some sticks and

through the flimsy door.

Blas was already in the house and proceeded to build the hunting con

seemed unconcerned with my story. traptions. I had mine almost fin

“They pulled a good one on you,” ished and was excitedly wondering

he said reassuringly. “The Indians whether or not it would work when

suddenly Don Juan stopped and

take delight in teasing foreigners.”

My experience had been so un looked at his left wrist, as if he were

nerving that the next day I drove to checking a watch which he had

Don Juan’s house instead of going never had, and said it was lunchtime.

I was holding a long stick, which I

home as I had planned to do.

Don Juan returned in the late was trying to make into a hoop. I

afternoon. I did not give him time automatically put it down.

Don Juan looked at me with an

to say anything but blurted out the

whole story, including Bias’s com expression of curiosity. Then he

mentary. Don Juan’s face became made the wailing sound of a factory

sombre. Perhaps it was only my siren at lunchtime. I laughed.

imagination, but I thought he was

“I’ll be damned,” he said.

worried.

“What’s wrong ?” I asked.

“Don’t put so much stock in what

He again made the long wailing

Blas told you,” he said in a serious sound of a factory whistle.

tone. “He knows nothing of the

“Lunch is over,” he said. “Go

back to work.”

struggles between sorcerers.

“You should have known that

I felt confused for an instant, but

it was something serious the moment then I thought that he was joking,

you noticed that’the shadow was to perhaps, because we had no provi

your left. You shouldn’t have run sions to make lunch with. I picked

either.”

up the stick again and tried to bend

“What was I supposed to do? it. After a moment Don Juan again

Stand there?”

blew his ‘whistle’.

“Right. When a warrior encoun

“Time to go home,” he said.

ters his opponent and the opponent

He examined his imaginary

is not an ordinary human being, he watch and then looked at me and

must make his stand. That is the only winked.

thing that makes him invulnerable.”

“It’s five o’clock,” he said.

“What arc you saying, Don

I put everything down and began

Juan?”

to get ready to leave. I presumed

“I’m saying that you have had that he also was preparing his gear.

your third encounter with your When I was through I looked up

worthy opponent. She’s following and saw him sitting cross-legged a

you around, waiting for a moment few feet away.

of weakness on your part. She almost

“I’m through,” I said. “We can

bagged you'this time.”

go any time.”

I felt a surge of anxiety and

He got up and climbed a rock.

accused him of putting me in un He stood there, five or six feet above

necessary danger. I complained that | the ground, looking at me. » >

Without him, it’s going to be just another parade

Buoyant Upholstery gives that special

quality of comfort that can keep even a

Lord Mayor from important occasions.

For over half a century Buoyant has been

offering this special kind of luxury.

Embassies, slipping lines and leading hotels

have chosen it to pamper their guests.

Private buyers of fine taste have used it for

living elegance in their homes.

The Melton suite is a perfect example

of the timeless tradition of Buoyant.

Beneath the surface is a frame of seasoned

timber constructed for lasting strength and

an exclusive patented springing system.

The ten-cushioned three piece suite has a

winged back and is illustrated in Dralon

velvet with matching “Venetian look”

figured velvet cushions. It is finished with

toning ruche and deep-tasselled bobble

fringing. The cushions are loose and

reversible.

Send for our colour brochure showing

the entire collection of Buoyant Upholstery,

plus a list of local stockists.

Buoyant Upholstery Ltd

Sales Office

Silentnight House

CRIf&VA rXSTT Salterforth Near Colne

Li Lancashire BBS SUE

I heard Don Genaro yelling

“Where’s my car ?” I asked,

He put his hands on either side of my whole car away ?” I asked.

something and I saw the hat bobbing

“What did I mean, Genaro?” addressing both of them.

his mouth and made a very prolonged

“Where’s the car, Genaro ?” Don up and down and then falling to the

and piercing sound. It was like a Don Juan asked.

“You meant that I can get into his Juan asked with a look of utmost ground, where my car was. It all

magnified factory siren.

took place with such speed that I did

“What are you doing, Don Juan ?” car, turn the motor on, and drive seriousness.

away,

” Don Genaro replied with

Don Genaro began turning over not have a clear picture of what had

I asked.

small rocks and looking underneath happened. I became dizzy and absent

He said that he was giving the unconvincing seriousness.

“Take the car away, Genaro,” them. He worked feverishly over the minded. My mind held on to a very

signal for the whole world to go

home. I was completely baffled. He Don Juan urged him in a joking tone. whole flat area where I had parked confusing image. I either saw Don

“It’s done!” Don Genaro said, my car. He actually turned over Genaro’s hat turning into my car,

looked at me, smiled and winked

every rock. At times he would pre or I saw the hat falling over on top

again. I suddenly became alarmed. frowning and looking at me askew.

I noticed that as he frowned his tend to get angry and would hurl the of the car. I wanted to believe the

Don Juan put his hands on both

latter, that Don Genaro had used his

sides of his mouth and let out eyebrows rippled, making the look rock into the bushes.

in his eyes mischievous and pene

Don Juan seemed to enjoy the hat to point to my car. Not that it

another whistle-like sound.

scene beyond words. He giggled and really mattered, one thing was as

He said that it was eight o’clock trating.

“All right!” Don Juan said chuckled and was almost oblivious awesome as the other, but just the

in the morning and that I had to set

same my mind hooked on that

up my gear again because we had a calmly. “Let’s go down there and of my presence.

“Genaro is a very thorough man,” arbitrary detail in order to keep my

examine the car.”

whole day ahead of us.

“Yes!” Don Genaro echoed. Don Juan said with a serious expres original mental balance.

I was completely confused by.

“Don’t fight it,” -I heard Don

then. In a matter of minutes my fear “Let’s go down there and examine sion. He’s as . thorough and meticu

lous as you are. You yourself said Juan saying.

mounted to an irresistible desire to the car.”

I felt that something inside me

I looked down to the area at the that you never leave a stone unturned.

runaway from the scene.

was about to surface. Thoughts and

foot of the hill, some 50 yards away, He’s doing the same.”

images

came in uncontrollable waves

where I had parked my car. My

Don Genaro took off his hat and

The sorcerer’s ring

stomach contracted with a jolt. The rearranged the strap with a piece of as if I were falling asleep. I stared at

of power

the

car

dumbfounded. It was sitting

car was not there! I ran down the string from his pouch, then he

“Do you remember the time when hill. My car was not anywhere in attached his woollen belt to a yellow on a rocky flat area about a hundred

feet

away.

It actually looked as if

I jammed your car?” Don Juan sight. I experienced a moment of tassel affixed to the brim of the hat.

“I’m making a kite out ofmy hat,” someone had just placed it there. I

great confusion. I was disoriented.

asked casually.

ran

towards

it and began to examine

I looked all round again. I re he said to me.

His question was abrupt and

I watched him and I knew that it.

unrelated to what we had been talk fused to believe that my car was

“

Goddamnit!

” Don Juan ex

ing about. He was referring to a time gone. I walked to the edge of the he was joking. I had always con

when I could not start the engine of cleared area. Don Juan and Don sidered myself to be an expert on claimed. “Don’t stare at the car.

Genaro joined me and stood by me, kites. When I was a child I used to Stop the world 1”

my car until he said I could.

Then as in a dream I heard him

I remarked that no-one could doing exactly what I was doing, make the most complex kites and I

forget such an event.

peering into the distance to see if the knew that the brim of the straw hat yelling, “Genaro’s hat! Genaro’s hat!”

I looked at them. They were

“That was nothing,” Don Juan car was somewhere in sight. I had a was too brittle to resist the wind.

asserted in factual tone.

moment of euphoria that gave way ■ The hat’s crown, on the other hand, staring at me directly. Their eyes

“Nothing at all. True, Genaro ?” to a disconcerting sense of annoyance. was too deep and the wind would were piercing. .I felt a pain in my

“True,” Don Genaro said in- They seemed to have noticed it and circulate inside it, making it im stomach. I had an instantaneous

began to walk around me, moving possible to lift the hat off the ground. headache and got ill.

dSerently.

Don Juan and Don Genaro looked

“You don’t think it’ll fly, do you ?’

“What do you mean ?” I said in their hands as if they were rolling

at me curiously. I sat by the car for

Don Juan asked me.

a tone of protest. “What you did that dough in them.

a while and then, quite automatically,

“I know it won’t,” I said.

day was something truly beyond my

“What do you think happened

Don Genaro was unconcerned I unlocked the door and let Don

comprehension.”

to the car, Genaro ?” Don Juan asked

and finished attaching a long string Genaro get in the back seat. Don

“That’s not saying much,” Don in a meek tone.

; v=: Juan followed him and sat next to him.

Genaro retorted.

“I drove it away,” Don Genaro to his kite-hat.

It was a windy day and Doit I thought that was strange because

They both laughed loudly and said and made the most astounding

then Don Juan patted me on the back. motion of shifting gears and steering. Genaro ran downhill as Don' Juan he usually sat in the front seat.

“Genaro can do something much He bent his legs as though he were held his hat, then Don Genaro pulled

I drove my car to Don Juan’s

better than jamming your car,” he sitting, and remained in that position the string and the damn thing act house in a sort of haze. I was not

myself at all. My stomach was very

went on. “True, Genaro ?”

for a few moments, obviously sus ually flew.

“Look, look at the kite!” Don upset, and the feeling of nausea

“True,” Don Genaro replied, tained only by the muscles of his legs;

then he shifted his weight to his Genaro yelled.

puckering up his lips like a child.

demolished all my sobriety. I drove

It bobbed a couple of times but mechanically.

“What can he do ?” I asked trying right leg and stretched his left foot

to mimic the action on the clutch. it remained in the air.

to sound unruffled.

I heard Don Juan and Don

“Don’t take your eyes off the Genaro in the back seat laughing

“Genaro can take your whole car He made the sound of a motor with

away!” Don Juan exclaimed in a his lips; and finally, to top every kite,” Don Juan said firmly.

and giggling like children. I heard

booming voice; and then he added thing, he pretended to have, hit a

For a moment I felt dizzy. Look Don Juan asking me, “Are we

bump in the road and bobbed up and ing at the kite, I had had a complete getting closer?”

in the same tone, “True, Genaro ?”

“True!” Don Genaro retorted in down, giving me the complete sen recollection of another time; it was

It was at that point that I took

the loudest human tone I had ever sation of an inept driver that bounces as if I were flying a kite myself, as I deliberate notice of the road. We

without letting go of the steering used to, when it was windy in the were actually very close to his house.

heard.

“I jumped involuntarily. My body wheel.

hills of my home town.

“We’re about to get there,” I

Don Genaro’s pantomime was

was convulsed by three or four ner

For a brief moment the recol muttered.

stupendous. Don Juan laughed until lection engulfed me and I lost my

vous spasms.

They howled with laughter. They

“What do you mean, he can take he was out of breath.

awareness of the passage of time.

clapped their hands and

y

After investing in a Slumberland Gold Seal bed

I thought my troubles were over.

In fact they were only just beginning.’

C I knew something was up. That

well rehearsed officious glare had

already set hard on his squirrel

like features.

The ensuing speech lasted for

ten minutes. And by the end of it I

had been left in no doubt that the

senior partners were unanimous

in their dissatisfaction with my (as

they put it) lack of purpose.

Precisely what they meant by

that, I wasn’t certain.' All I knew

was that in a way, I agreed.

My wife, in typical style, said it

was probably all her fault.

And I, for want of something

better to say, put it down to a

general lack of sleep and promptly

changed the subject.

Two days later, my wife, in

typical style, took it upon herself to

remedy the situation, and pro

ceeded to spend no less than. £150

on a brand new bed.

From what I could gather, it had

a hand built frame, a stretch

Crimplene cover, Double Posture

Springing, and goodness knows

what.

According to the salesman, the

Slumberland Gold Seal was the

finest bed she could buy. The only

bed in the world with Double

Posture Springing. (Equivalent to

over 3,000 springs I’m told.)

After just one night on it, I must

say I felt somehow that my prob

lems might just be over.

The second night, after over

sleeping for the first time in living

memory, and arriving 40 minutes

late for an important meeting, it

occurred to me that they might just

be beginning. ?

Should any points in the above story

strike you as being somewhat familiar,

write for a free Slumberland Gold Seal

brochure and list of stockists to:

Dept. D.L.16., Slumberland Limited,

Redfern Road, Birmingham Bl 12BN.

62

slapped their thighs.

When we arrived at the house I

automatically jumped out of the car

and opened the door for them. Don

Genaro stepped out first and con

gratulated me for what he said was

the nicest and smoothest ride he had

ever taken in his life. Don Juan said

the same. I did not pay much atten

tion to them.

I locked my car and barely made

it to the house. I heard Don Juan and

Don Genaro roaring with laughter

before I fell asleep.

“I will tell you one more thing,”

Don Juan said and laughed. “It really

does matter now. Genaro never

moved your car from the world of

ordinary men the other day. He

simply forced you to look at the

world like sorcerers do, and your

was not in that world. Genaro

wanted to soften your certainty. His

clowning told your body about the

absurdity of trying to understand

everything. And when he flew his kite

you almost saw. You found your car

and you were in both worlds. The

reason we nearly split our guts

laughing was because you really

thought you were driving us back

from where you thought you had

found your car.”

Stopping the world

“Go there,” he said cuttingly.

I drove south and then east, fol

lowing the roads I had always taken

jvhen driving with Don Juan. I

parked my car around the place

where the dirt road ended and then

I hiked on a familiar trail until I

reached a high plateau. I had no

idea what to do there. I began to

meander, looking for a resting place.

Suddenly I became aware of a small

area to my left. It seemed that the

chemical composition of the soil was

different on that spot, yet when I

focused my eyes on it there was

nothing visible that would account

for the difference. I stood a few feet

away and tried to ‘feel’ as Don Juan

had always recommended I should.

I stayed motionless for perhaps

an hour. My thoughts began to

diminish by degrees until I was no

longer talking to myself. I then had

a sensation of annoyance. The feeling

seemed to be confined to my stomach

and was more acute when I faced the

spot in question. I was repulsed by

it and felt compelled to move away

from it I began scanning the area

with crossed eyes and after a short

walk I came upon a large flat rock. I

stopped in front of it. There was

nothing in particular about the rock

that attracted me. I did not detect

any specific colour or any shine on it,

and yet I liked it. My body felt good.

I experienced a sensation of physical

comfort and sat down for a while.

I meandered in the high plateau

and the surrounding mountains all

day without knowing what to do or

what to expect. I came back to the

flat rock at dusk. I knew that if I

spent the night there I would be safe.

The next day I ventured farther

east into the high mountains.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★

I wiped my eyes and as I rubbed

them with the back of my hand I

saw a man, or something which had

the shape of a man. It was to my

right about 50 yards away. I sat up

straight and strained to see. The sun

was almost on the horizon and its

yellowish glow prevented me from

getting a clear view. I heard a pecu

liar roar at that moment. It was like

the sound of a distant jet plane. I

again strained to see if I could dis

tinguish the person that seemed to

be hiding from me, but I could only

detect a dark shapeagainstthebushes.

I shielded my eyes by placing my

hands above them. The brilliancy,of

the sunlight changed at that moment

and then I realised that what I was

seeing was only an optical illusion,

a play of shadows and foliage.

I moved my eyes away and I saw

a coyote calmly trotting across the

field. The coyote was around the

spot where I thought I had seen

the man. It moved about 50 yards in

a southerly direction and then it

stopped, turned, and began walking

towards me. I yelled a couple of

times to scare it away, but it kept on

coming. I had a moment of appre

hension. I thought that it might be

rabid and I even considered gather

ing some rocks to defend myself in

case of an attack. When the animal

was 10 to 15 feet away I noticed that

it was not agitated in any way; on

the contrary, it seemed calm and

unafraid. It slowed down its gait,

coming to a halt barely four or five

feet from me. We looked at each

other, and then the coyote came

even closer. Its brown eyes were

friendly and clear. I sat down on the

rocks and the coyote stood almost

touching me. I was dumbfounded.

I had never seen a wild coyote that

close, and the only thing that

occurred to me at that moment was

to talk to it. I began as one would

talk to a dog. And then I -»■>

Domecq have been making fine sherries

since 1730. Machamudo Castle, traditional

home of the Domecq family, dominates the

Domecq vineyards-acknowledged to be

the finest in Jerez.

£omecq

I

Sherry is one of the world’s great wines...

lovingly matured in the solera.

The solera is simply a system of stacked

rows of casks in which sherry is aged and

blended. Every year, some of the sherry in

the top row is moved to the row below, and

so on. Matured sherry is drawn from the

lowest casks, and the top casks filled up with

new wine. So some of the sherry in a solera

will always be as old as the day the solera

was started.

double:

Centura

Nelson was a lover of Domecq sherry, and

is said to have taken many a glass. His named

cask still stands in the cool, shady bodegas in

Jerez - alongside that of Napoleon. Enemies

united in the appreciation of the finest sherry

in the world!

Domecq produce a range of sherries to suit

all tastes. Double Century, the golden

oloroso with a subtle touch of sweetness;

Celebration Cream, rich and full-bodied;

La Ina, the light, dry fino that is delicious

served chilled; and Casino Amontillado,

the medium sherry with a delicious hint of

dryness.

When drinking sherry from a Domecq solera

you could be drinking the Domecq that Nelson drank

thought that the coyote ‘talked’ back

to me. I had the absolute certainty

that it had said something. I felt con

fused but I did not have time to

ponder upon my feelings, because

the coyote ‘talked’ again. It was not

that the animal was voicing words

the way I am accustomed to hearing

words being voiced by human

beings, it was rather a ‘feeling’ that

it was talking. But it was not like

a feeling that one has when a pet

seems to communicate with its

master either. The coyote actually

said something; it relayed a thought

and that communication came out in

something quite similar to a sen

tence. I had said, “How are you,

little coyote?” and I thought I had

heard the animal respond, “I’m all

right, and you?” Then the coyote

repeated the sentence and I jumped

to ♦ feet. The animal did not make

a single movement. It was not even

startled by my sudden jump. Its

eyes were still friendly and clear. It

lay down on its stomach and tilted

its head and asked, “Why are you

afraid ?” I sat down facing it and I

carried on the weirdest conversation

I had ever had. Finally it asked me

what I was doing there and I said

I had come there to “stop the world”.

The coyote said, “Que bueno!” and

then I realised that it was a bilingual

coyote. The nouns and verbs of its

sentences were in English, but the

conjunctions and exclamations were

in Spanish. The thought crossed my

mind that I was in the presence of a

Chicano coyote. I began to laugh at

the absurdity of it all and I laughed

so hard that I became almost

hysterical. Then the full weight of

the impossibility of what was hap

pening struck me and my mind

wobbled. The coyote stood up and

our eyes met. I stared fixedly into

them. I felt they were pulling me

and suddenly the animal became

iridescent; it began to glow. It was

as if my mind were replaying the

memory of another event that had

taken place 10 years before, when

under the influence of peyote I wit

nessed the metamorphosis of an

ordinary dog into an unforgettable

iridescent being. It was as though

the coyote had triggered the recol

lection, and the memory of that

previous event was summoned and

became superimposed on the coyote’s

shape; the coyote was a fluid, liquid,

luminous being. Its luminosity was

dazzling. I wanted to cover my eyes

with my hands to protect them, but

I could not move. The luminous

being touched me in some undefined

part of myself and my body experi

enced such an exquisite indescrib

able warmth and well-being that it

was as if the touch had made me

explode. I became transfixed. I

could not feel my feet, or my legs,

or any part of my body, yet some

thing was sustaining me erect.

I have no idea how long I stayed

in that position. In the meantime,

the luminous coyote and the hilltop

where I stood melted away. I had no

thoughts or feelings. Everything had

been turned off and I was floating

freely.

Suddenly I felt that my body had

been struck and then it became en

veloped by something that kindled

me. I became aware then that the

sun was shining on me. I could

vaguely distinguish a distant range

of mountains towards the west. The

sun was almost over the horizon. I

was looking directly into it and then

I saw ‘the lines of the world’. I actu

ally perceived the most extraordinary

profusion of fluorescent white lines

which criss-crossed everything around

me. For a moment I thought that I

was perhaps experiencing sunlight as

it was being refracted by my eye

lashes. I blinked and looked again.

The lines were constant and were

superimposed on or were coming

through everything in the surround

ings. I turned around and examined

an extraordinarily new world. The

lines were visible and steady even if

I looked away from the sun.

I stayed on the hilltop in a state

of ecstasy for what appeared to be an

endless time, yet the whole event

may have lasted only a few minutes,

perhaps only as long as the sun shone

before it reached the horizon, but to

me it seemed an endless time. I felt

something warm and soothing ooz

ing out of the world and out of my

own body. I knew I had discovered

a secret. It was so simple. I experi

enced an unknown flood of feelings.

Never in my life had I had such a

divine euphoria, such peace, such an

encompassing grasp, and yet I could

not put the discovered secret into

words, or even into thoughts, but my

body knew it.

Then I either fell asleep or I

fainted. When I again became aware

of myself I was lying on the rocks.

I stood up. The world was as I had

always seen it. It was getting dark

and I automatically started on my

way back to my car©

COMO...

THE CHAIR THAT’S

ASUITE IN ITSELF.

From Europe’s new designers, a distinctive chair:

attractively priced, beautiful to live with - and very

adaptable. On its own you have a luxurious fireside chair.

Put several side by side and you create a settee to suit your

space. A woman can easily move this chair around, it weighs

only 12 i lbs., yet it!s solidly made with a frame in burnished

chromium-plated steel - gleaming beauty that needs no

polishing. Upholstery is a linen and cotton mixture in an

attractively new pattern. The full-length cushion is a

foam/fibre mixture supported on springy canvas fixed to the

frame. With the ‘Como’ goes a matching occasional table,

also with burnished chromium-plated steel frame. The top in

smoky glass lifts off for easy sponging over. Dimensions:

Chair height, floor to back 27'. Table top 24' x 24'. Both chair

and table come to you in quick-to-assemble form - another

reason why the ‘Como’ represents outstanding value.

Order today from Woolworth by Post.

CHAIR ONLY £15.95 + £1.00 P&P

TABLE ONLY £12.95 + ^?

FREEPOST! No itamp noeded

Rcg'a

return carriape. you advise

242°246MirlSonc Road. London

X

in° thcmpWoohvoJth°bJepost.

SIL. LW<1 In Knoland Wo. 10L2061

SWISS’.

————

ORDER FORM

WOOLWORTH BY POST, DEPT. ST2 ,

FREEPOST, SWINDON, WILTS, SN3 5BR

I enclose a cheque/M.O./P.O. for the sum of -C

Made payable to F. W. Woolworth 4 Co. Ltd. dU_____

| IMPORTANT:These offers apply to British Mainland only.

I

HR W HUE

FtHBVEHEVBK

Despite the success of the

technological age and the continuing

advance of scientific thought, we are

still a superstitious people. Many

old beliefs remain - but with 20thcentury modifications. BYRON

ROGERS examines the extent

to which we still cross our fingers

On this island (left) in north Scotland men once

threw pennies in a well and wished. The well dried,

so ambitious Scotsmen stuck coins in a tree

above. The tree is now dying of copper poisoning.

Above: Eternal lodger. Mrs Kerton-displays the

skull of Theophilus Broome, who died in 1670

requesting that his head be kept at. his house at

Chilton Cantelo. Burial produces “horrid noises”

“This happened during the war. A distant relative

of mine, a lad from Tiree in the South Hebrides, was

helmsman on a destroyer. The ship was part of a

flotilla escorting a convoy out into the mid-Atlantic

where an American flotilla would take over. It was

night and he was alone on the bridge except for the

officer of the watch.

“Suddenly he felt the wheel moving against him.

As he looked down in some bewilderment he saw in

the gloom two hands - severed hands, a woman’s

hands - pulling at it. The force exerted was so strong

that the ship lurched off course. The officer of the

watch shouted at the lad, and by using all his

strength he pulled it back on course.

“But it happened again. This time he told the

officer exactly what he had seen and was happening.

„ The officer failed to see the hands but then he too

3 saw the wheel move. He ran for the captain, who

1 came up on bridge. The captain saw the wheel

“ moving but again failed to see the hands.

o

“This time the ship really was on another course.

> The captain asked the officer to plot it. Then,' by

£ sheer force again, they managed to get the ship

| back with the convoy. This time the hands seemed

2 to give up.

f

“After their rendezvous they started back. When

At the Cloutie Well north of Inverness (above) people tie rags along the pipe which is all

that remains, and on the fence above. Mrs Jean Gray, who lives nearby, tries her luck. Below:

Dupath Well, near Callington, Cornwall, reputedly cures whooping cough. Mrs Coombe and her

son Andrew, of Dupath Farm, stand beside the shrine erected by coughing pilgrims. Right:

Rev. Harold Lockyear of St Nectan’s Church, Stoke, Devon, points to the place where he saw a

hooded ghost. St Nectan, a Welsh missionary, was beheaded by the English, but kept walking

22

great number of people. Even in a

society as traditional as that of the

Hebrides, some are in eclipse and

survive only in anecdote. Thus a

belief in fairies is now universally

regarded as pure superstition. But

in living memory it was not so. John

Maclnnes, as asmall boy, met a minister

in Skye who claimed to have seen

them.

“He would have taken an oath in

court about it. He had seen, he said,

the fairies dancing in the moonlight.

They were small people. That was

some time towards the end of the

19th century. All his Christian doctrine

would have made him reject this, but

he was convinced that he had seen

them, and this had frightened him.

Pressure of belief in a society can

make people see things.

“My own great-uncle in Skye, a

hard-headed businessman, announced

when he was 80 that he had seen the

Washerwoman at the Ford. She is the

figure who washes the shrouds of the

dead, and to see her is an omen of

your own death. I don’t think he

would have believed in her at any

other time of his life. But if the com

munity you grow up in believes in

something, even though you yourself

reject it, something such as old age or

ill-health can still jolt you back.”

Mrs Eilidh Watt of Dunfermline, a

retired schoolteacher, comes from

a Skye family who have the second

sight. It is acknowledged to be a

hereditary thing. “Nobody practises

the second sight, you just have it.

efinitions are central to any dis

Nobody seeks it. People try to get rid

cussion of superstition. One of it in general as the experiences you

man’s belief, as Voltaire said, is have are so frightening. My father, for

another man’s superstition. “A French instance, never talked about it, except

man travelling in Italy finds almost sometimes to my mother. She would

everything superstitious. The Arch tell us children.

bishop of Canterbury claims that the

“They never try to prevent what

Archbishop of Paris issuperstitious; the they have seen. A man on Mull

Presbyterians levy the same reproach dreamed on three successive nights

against his Grace of Canterbury . . .” that his son would be drowned. The

The frontiers of superstition change following day he decided he would not

constantly. Few people would believe let the boy out of his sight, so he took

today that it is possible to work out him to work. As they came down a

the Day of Creation from evidence road a horse suddenly bolted towards

provided in the Bible; yet for much of them. The man threw the child aside,

the last century this belief was stoutly out of danger, while he caught and

defended.

quietened the horse. When he looked

Superstitions survive, despite the back he saw his child floating face up

encroachments of secularly, science in the bum.

and the media. Danger, uncertainty,

“You cannot intervene. What you

fear bring them surging up again, as have seen will always take place. The

in times of war and ill-health. Often, child, had it stayed at home, would

in the classic dictionary definition, just have fallen face down into a

they are beliefs sheepishly clung to in bucket of water.”

spite of the fact that no rationality or

There is no tradition in a Gaelic

scientific evidence underwrites them.

community of anyone consulting

A superstitious man would appre someone with the second sight to see

ciate that wonderful exchange between into the future. It is not boasted

Chesterton and a Cambridge student. about, not even mentioned except to

Chesterton asked him whether he friends or close relatives. Though it is

knew if he existed.

possible to pass it on, by the secondThe student: “No I should say I sighted one placing his left foot on

have an intuition that I exist.”

another’s left foot, and his left hand

Chesterton: “Cherish it. Cherish it.” on the other’s left hand, it is never

Yet there is little joy in superstitions. sought. There is a chilling story of one

Usually they are an attempt to pro man who sought it, and at last pre

pitiate, or ward off, something - or vailed upon someone to do this for

just to ensure good fortune. They are him, only to lose his reason as the

difficult to index as few people are result. The second sight was not

prepared to talk about their super hereditary, and he could not cope.

stitions, unless they are shared by a

Second sight is the best con-

they got to the point where it had

happened the captain ordered that

the ship take the course the hands had

indicated. They sailed for six hours.

At the end of this time they came upon

a raft. There were two bodies on the

raft, that of a woman and a baby. The

baby was still alive. The woman was

quite cold.

“The lad came from a family in

which there was a tradition of the

second sight. Now if you make that

story up either you’ve got a very

powerful imagination or it actually

happened. I’m an agnostic about the

second sight; but you must remember

that if I, sitting here in Edinburgh,

can tell you that story it’s an indication

of how strong is the tradition.”

John Maclnnes is a lecturer in

Scottish Studies in that shrine to

rationality, the University of Edin

burgh. A Gaelic speaker, he left his

native Hebrides over 20 years ago,

at 18, but frequently returns to a croft

he owns there. He grew up in a cul

ture which believed firmly in the

second sight: the ability to see the

future, and especially doom in the

future, superimposed upon the present.

“The primary living superstition in

the Hebrides and in the Highlands is

the second sight,” he says. “Only I

wouldn’t call it a superstition. This is

pretty firmly believed in, still. I don’t

see any diminution in their beliefs at

all, and there is no feeling of super

stition. People there get very angry

when outsiders laugh.”

D

23

temporary example of a belief shared

by a community who cannot account

for it rationally. This is what the great

superstitions of the past were like,

dark things on the fringes of ex

perience, often an alternative to the

official teaching of Church and State,

and one’s own common sense.

Maclnnes thought that belief in

wishing wells had disappeared in the

Highland communities. This is the

idea that one gives an offering to a

well in order to have a wish granted.

Yet the wells survive, if only as a

tourist attraction, or as a ritual for the

living to carry out just for the amuse

ment it affords, as at Christmas.

In his book Haunted Britain* Antony

Hippisley Coxe instances the Cloutie

Well in the Black Isle above Inverness

as “the most telling visual manifesta

tion of superstition” he had ever seen.

Here on the first Sunday in May

people hang out rags as offerings to

the goddess of the well. The well is a

pipe coming out of a bank beside the

road. Just above it, fencing off a clump

of <es, is some 30 yards of wire

netting.

It looks like a rubbish tip. About

the netting are tied pieces of trousers,

string vests, handkerchiefs, petticoats,

tights, sheets, pyjamas, linen drawers,

socks, net curtains. They flutter

weirdly in the wind, and look rather

menacing.

An old lady, who had lived near the

well all her life, talked about it. “We

all used to go in the old days when I

was young. It was a meeting place.

People came from all around. Yes, I

used to wish. No, I don’t now. You

don’t believe in it as you get older.

The education has finished it off, you

see. No, the ministers never inter

fered with it 1 think it’s for the

tourists now.”

The attitude of the Church is always

a good index to the strength of a

superstition. In the Highlands it has

b^m and remains, as Mrs Watt bore

out, opposed to the second sight. It

represents an alternative belief. John

Maclnnes said that he knew even now

of one man afflicted with the second

sight who would not go out at night

except with a Bible in his pocket for

protection.

But most superstition in Britain

today is of a rag-bag variety, like a

tendency not to walk under ladders

or to touch wood for safety, which add

up to no organised system of belief.

A good example are the superstitions

of sports players, particularly profes

sional footballers.

Jackie Charlton, late of Leeds and

England, now manager-elect of

Middlesbrough, admits to being

superstitious. “I go to the lavatory

before every game. I take a programme

with me. I put it down to the left of

me if we’re playing at home, and to

the right if we’re playing away. It was

awful playing abroad where some

times they don’t have programmes.

What did I do? Well I’d have to take

the team sheet in with me.”

Charlton’s superstitions are all re

served for football. “Basically it’s

what you’ve found either brings you

experience in that time was that when

I got up to go to work I got to work.”

The irony about superstitions is the

way modern technology has adopted

them. To the headless horseman and

white ladies of folklore the Midlands

has added one of its very own,

fashioned understandably, out of the

internal combustion engine. A ghost

lorry with dim headlights haunts the

wrong side of the A428 from Coven

try to Rugby: it has no doubt figured

in many a hopeful insurance claim.

Stewart Sanderson, Director of the

Folk Studies Department at Leeds

University, has done some research

into the superstitions that have grown

up around the motor car. There are

the talismans like St Christopher

medallions on dashboards and old

number plates transferred to new

cars to bring luck.

Sanderson is particularly struck by

the short length of chain attached to

the rear bumber of a car as a cure for

travel sickness. The explanation ad

vanced is that it transmits to earth the

figure, 2,000 years old. Legend says that childless couples passing a static electricity built up in the car’s

night on the relevant portion of the giant will be blessed with fertility bodywork during travel, which, it is

claimed, causes sickness. Yet, as he

success, or doesn’t bring you failure. superstition of not passing under a notes, almost invariably the chain is

For years I’d never touch a ball unless ladder simply by putting a ladder only a few links long and does not

I could crack it into the net first shot. against a wall over a pavement. There reach the ground, thus earthing

Gary Sprake’s first job was always to was no one up the ladder, yet 37 of nothing. “The practice is in fact

roll a ball to me gently and I’d hit it the 51 people who passed by in 15 normally magic, and if indeed effica

into the goal. I’d go crackers if a minutes stepped into the road.

cious, presumably works by auto

goalkeeper caught it.

Immigrant communities, if only suggestion.”

“I think everyone in football has his because of their smaller numbers, are

Sanderson has also indexed a series

pet superstition. I know players who easier to study. One Leeds student for of myths widely believed in connec

wouldn’t change their boots until the his post-graduate diploma investigated tion with Rolls-Royces: that no one

end of the season and you’d see them their superstitions. Two West Indians, is-allowed to drive a Rolls-Royce

with their laces all covered in knots. In who wanted to settle down with as unless he has been trained at the

changing rooms you can often see them little difficulty as possible in the city, company’s driving school; that the

doing something, but that’s their brought with them to Britain a bonnet of a Rolls-Royce is sealed and

business. I wouldn’t dream of laughing small sample of their native soil. When the breaking of the seals invalidates

at them.

they got to Leeds they mixed this with the guarantee; that the company will

“I suppose I’m more superstitious some Leeds earth, and added water. not allow any owner to make modi

than most, but Revie . . . he’s worse They then drank the lot.

fications to a Rolls (especially strong

than me. He’s even had people to lift

Occasionally there is delicate social in the case of people who want to turn'.

curses from the Leeds United ground. comedy in the meeting of cultures, as the car into a van); and that the Silver

At one stage the team wasn’t having when the immigrant from St Nevis, Lady mascot is always made of silver.

any successes and someone told seeking to ensure a supply of good

This is one of the few instances

Revie that it was because of a curse luck, went round the shops of Leeds where a piece of technology has

laid on it by a gypsy who’d been asking for horseshoes, with no result. acquired its own folklore. Usually it is

moved off the site years before. Revie

a case of a very old superstition

had a woman over from Blackpool to

ne or two are quite peculiar,

acquiring its own modem slant, as in

and it will be fascinating to see ghost lorries, or perhaps unidentified

lift the curse. I think he had her over

more than once.”

how long they persist on alien flying objects. Modem technology

Charlton has the classic conflict of soil. To comb your hair at night is an seems to have done little to diminish

a modem superstitious man, between open invitation for the Jumbies to call. superstition.

the ritual he observes and his own (Jumbies are West Indian ghosts). A

Perhaps it is a case of wanting to

common sense. “I’m not a religious dry leaf carried on the wind brings believe in the strange, and the wonder

man but I do have certain beliefs, so good news if it touches someone.

ful and the dreadful. Perhaps it is a

I’m a bit guilty that I do have these

Certain jobs, such as mining and the case of just having to. As Sanderson

superstitions.”

stage, have their own superstitions. To remarked: “One might say that more

It is difficult to work out just how quote Macbeth back-stage is bad luck highly-educated people are less super

superstitious Britain is today. The (John Osborne once changed a men stitious; but the more I observe my

only large-scale survey was under tion of Macbeth in one of his plays fellow dons the less I am convinced

taken by Geoffrey Gorer who in 1955 to Antony and Cleopatra because the of this. The logic that mankind has

invited readers of a newspaper to cast objected.) Bad things are sup pieced together so painfully is easily

answer a lengthy questionnaire. More posed to happen when Macbeth is broken through.”

than 14,000 replied. He found that one performed: the cast get injured or

Perhaps complete rationality, like

in six believed in ghosts, and nearly forget their lines.

the Golden Age and the Just City, is

one quarter were uncertain as to

Mining superstitions, as one ex out of reach of humankind. If any

whether or not they existed. One per miner observed dourly, mostly involve thing goes wrong, like disaster or

son in three had been to a fortune not going to work. You turned back if disease (magicians, as Defoe noted,

teller. About two-thirds read their you saw a woman on the way to the pit, throve during the Plague), then the

horoscope at least occasionally. One or if you heard a crow croak. Yet it is old terrors lurch back. Perhaps they

person in ten believed they had lucky arguable how many of these persist will always be there, beyond the light,

days or numbers.

today. A Barnsley miner said: “I’ve out of reach of faith, or knowledge, or

A psychologist investigated the been in the pits 35 years. All my even humour, their greatest enemy.

O

• Haunted Britain—A Guide to SupernaturalSites frequentedby Ghosts. Witches. Poltergeists and otherMysterious Beings by Antony Hippisley Coxo. will be published by Hutchinson & Co. on October 1. at £4.

25

Of God’

Are Edgy

By WILLIAM J. DRUMMOND

Los Angele* Time* Service

NEW DELHI—The first na

tionwide public opinion poll

among India’s lowly untouch

ables shows a growing will to

rebel that carries explosive

possibilities.

The landmark survey was

carried out by the Indian In

stitute of Public Opinion here,

an affiliate of the interna

tional Gallup group.

The poll described the treattnent of untouchables prevail

ing today as “indian apar

theid.”

• “The high-handedness of

dominant castes is creating

what might be described as a

gsychologicail

backlash

among the Harijans (untouch

ables) said institute Director

Eric P. W. De Costa. Hari

jans, literally “children of

God,” is the name given to

the untouchables by Ma

hatma Gandhi.

f "Forty percent of those sur

veyed throughout the country

would opt for organizing their

Community to fight against

injustice committed by other

castes,” said De. Costas, add

ing:

Violence Threat

i “A sizable segment of the

Harijan community is thus in

<t ferment that carries explo

sive possibilities, a majority

oT those willing to organize I

themselves would not hesitate I

to resort to violence in self

defense.

“This

militant

section I

constitutes only one-fifth of

the Harijan community. But

this small but determined

segment may eventually con

vert the silent and resentful

majority to opt for violence

when the chips are down.”

; The number of Harijans in

India is estimated at 80 mil

lion, or about 15 percent of

the totql population.

■ “They’ are eligible for spe- |

cial government quotas in

gaining employment or edu- J

cation.

■ Apart from constitutional

guarantees for a number of

individual rights, discrimina

tion on grounds of untoucha

bility is a crime punishable

by law.

A special act provides pen

alties for preventing a Hari

jan from using public facili

ties or subjecting him to so

cial or occupational discrimi

nation.

• However, De Costa found

(hat the legal guarantees had

been ineffective.

; The survey of 1,500 respon

dents found that 13 percent of

Harijan

youngsters

were

placed in segregated seating

arrangements

in schools,

more than 50 percent of Hari

jans were made either to

stand or to sit on the ground

during visits to the home of

caste Hindus and 40 percent

of Harijans said they were

forbidden to enter a caste

Hindu temple to worship.

Losing Battle

Economically, the Hari

jans are still downtrodden,

De Costa said.

■ “A vast majority, notwith

standing the evidence of some

improvement in economic

condition, still have to wage a

■losing struggle for making

■ends meet,” he said.

‘ “This is reflected in the

Heeling shared by a sizable

^segment (43 percent) that

'their lot is more titan their

parents’.”

; De Costa drew attention to

ithe recent formation of a

'.'group in Maharashtra state

^calling itself the Dalit Pan'thers (Black Panthers), a

►militant organization of unllouchables that has borrowed

la page from Eldridge Cleaver.

‘ Earlier this year, the Dalit

►Panthers engaged in violent

iclashes in the streets of Bom;bay with caste Hindus and

£ police in which dozens of per

sons were injured.

The possibility that the

j Dalit Panthers might become

• the leaders of Harijans seek' ing change "must surely call

“for some furious thinking on

• the part of India’s privileged

I classes.”

34

THE jJ^V TIMES, NOVEMBER 25 1973

THE SUNDAY_THyiESj_NOyEMBg^ 25_12Z2.

myself included, decided to do

no more than was really neces

sary, following orders but if

possible keeping out of harm’s

way. I have a feeling that many

of the officers felt the same

way.”

Keeping from freezing was a

major front line preoccupation

during the ensuing bitter win

ter. Chancy recalls an occasion

when it brought opposing

trenches into a kind of brother

hood of mutual suffering.

J| Continued from

yl preceding page

rifle, but we hoped for the best. ing out of their uniforms,

meeting with his father, who

We each made little piles sometimes smelling to high

was serving as a staff sergeant

in charge of an advance field

beside us of the clips of heaven.”

hospital.

cartridges for easy reloading,

Such memories remained

left and right. There they sat,

loading with nine cartridges buried for many years after the

“ I saw him standing by the

squat monstrous things, noses

in the magazine and one in war when Chaney, like so many

roadside anxiously scanning

stuck up in the air, crushing

the

breech,

and

waited.

Noth

others who had been promised

the faces as we passed by, but

the sides of our trench out of

ing seemed to be happening a “ Land fit for Heroes.”

1 had to shout to him and wave

shape with their machine-guns

so I thankfully dropped down plunged into another kind of

my hand frantically before he

swivelling around and firing

into the ditch half full of water fight for survival. It was dur

spotted me. He scrambled

like mad.

and fell asleep.

ing the days of the Depression

through the marching ranks to

“ I was awakened with the in 1928 that two particular

" Everyone dived for cover,

get to me and gazed at me in