RF_PH_5_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_PH_5_SUDHA

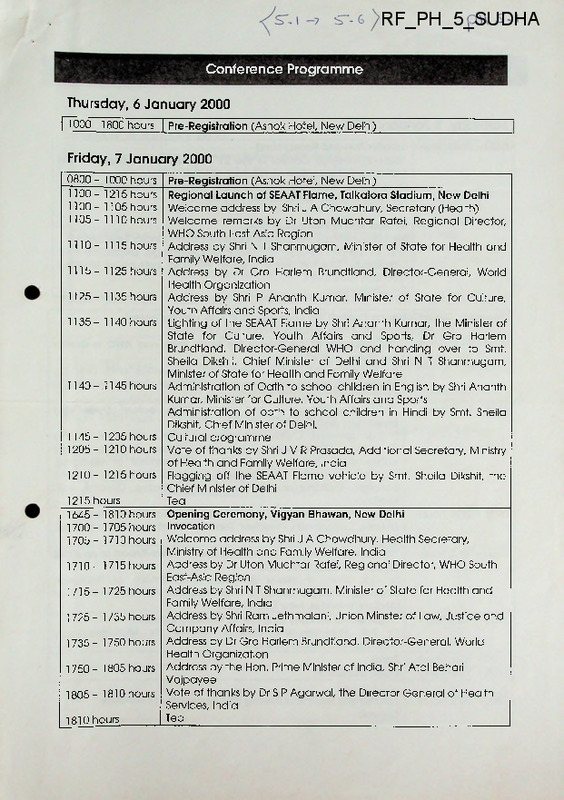

Conference Programme

Thursday, 6 January 2000

| 1000 -1800 hours | Pre-Registration (Ashok Hotel, New Delhi)

Friday, 7 January 2000

0800- 1000 hours

1100- 1215 hours

1100 - 1105 hours

1105 - 1110 hours

1110 - 1115 hours

1115- 1125 hours

1125- 1135 hours

1135 - 1140 hours

1140- 1145 hours

1145- 1205 hours

1205- 1210 hours

1210- 1215 hours

1215 hours

1645- 1810 hours

1700 - 1705 hours

1705- 1710 hours

1710- 1715hours

1715- 1725 hours

1725- 1735 hours

1735 - 1750 hours

1750 - 1805 hours

1805- 1810 hours

1810 hours

Pre-Registration (Ashok Hotel, New Delhi)

Regional Launch of SEAAT Flame, Talkatora Stadium, New Delhi

Welcome address by Shri J A Chowdhury, Secretary (Health)

Welcome remarks by Dr Uton Muchtar Rafei, Regional Director,

WHO South East-Asia Region

Address by Shri N T Shanmugam, Minister of State for Health and

Family Welfare, India

Address by Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, Director-General, World

Health Organization

Address by Shri P Ananth Kumar, Minister of State for Culture,

Youth Affairs and Sports, India

Lighting of the SEAAT Flame by Shri Ananth Kumar, the Minister of

State for Culture, Youth Affairs and Sports, Dr Gro Harlem

Brundtland, Director-General WHO and handing over to Smt.

Sheila Dikshit, Chief Minister of Delhi and Shri N T Shanmugam,

Minister of State for Health and Family Welfare

Administration of Oath to school children in English by Shri Ananth

Kumar, Minister for Culture, Youth Affairs and Sports

Administration of oath to school children in Hindi by Smt. Sheila

Dikshit, Chief Minister of Delhi.

Cultural programme

Vote of thanks by Shri J V R Prasada, Additional Secretary, Ministry

of Health and Family Welfare, India

Flagging off the SEAAT Flame vehicle by Smt. Sheila Dikshit, the

Chief Minister of Delhi

Tea

Opening Ceremony, Vigyan Bhawan, New Delhi

Invocation

Welcome address by Shri J A Chowdhury, Health Secretary,

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India

Address by Dr Uton Muchtar Rafei, Regional Director, WHO South

East-Asia Region

Address by Shri N T Shanmugam, Minister of State for Health and

Family Welfare, India

Address by Shri Ram Jethmalani, Union Minster of Law, Justice and

Company Affairs, India

Address by Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, Director-General, World

Health Organization

Address by the Hon. Prime Minister of India, Shri Atal Behari

Vajpayee

Vote of thanks by Dr S P Agarwal, the Director General of Health

Services, India

Tea

Conference Programme (confd.)

Saturday, 8 January 2000

0830 - 0845 hours

Introduction and Background

"Global Tobacco Control in the 21s' Century and Update on the

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control"

Dr Douglas Bettcher, Coordinator, Framework Convention on

Tobacco Control, World Health Organization

0845 - 0900 hours

Introduction to Methods of Work

Ms Indira Jaisingh, Advocate, Supreme Court of India, New Delhi

and Dr Srinath Reddy, Professor of Cardiology, Department of

Cardiology, Cardiothoracic Centre, All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, New Delhi

Co-Chairpersons

Plenary 1: Global Tobacco Control: The Economic and Agricultural Context

Co-chaired by Ms Indira Jaisingh and Dr Srinath Reddy

0900 - 0915 hours

“An overview of the Role of the World Bank and WHO in Global

Tobacco Control”

Professor Iraj Abedian, Professor of Economics and Director,

Applied Fiscal Research Center, University of Cape Town, South

Africa

0915-0935 hours

“Role of multinational and other private actors: Trade and

Investment Practices”

Dr Luk Joossens, Centre for Research and Information for the

Consumer Organisations, Brussels, Belgium, Professor Prakit

Vateesatokit, Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine,

Mahidol University, Ramathibodi Hospital, Medical School,

Bangkok, Thailand and Ms Bungon Rithipakdee, Director, ASH

Thailand

0935 - 0950 hours

“Ownership of Tobacco Companies and Implications on Health”

Dr Hatai Chitanondh, President, Thailand Health Promotion Institute,

Bangkok.

0950 - 1005 hours

"The Cost of Tobacco Related Diseases in India-Report of an ICMR

Task Force Study 1990-1996”

Dr G.K. Rath, Professor & Head, Department of Radiation

Oncology, Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, All India Institute of

Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

1005- 1020 hours

"Agricultural Diversity as a Tool of Tobacco Control”

Dr P.R. Panchamukhi, Director, Centre for Multi-disciplinary

Development Research, India

1020- 1035 hours

Break______________________________

1035- 1300 hours

Open discussion_______________

1300- 1400 hours

Lunch/Press Technical Briefing (The Economics of Tobacco

Control)_______________________________

Conference Programme (contd.)

Saturday, 8 January 2000

Plenary II: Industry Challenges and Public Health Responses

Co-chaired by Ms Indira Jaisinah and Dr Srinath Reddy

1400- 1420 hours

“Media and Global Responsibility”

Ms Ambika Srivastava, Media Consultant New Delhi, and Mr

Ross Hammond, Hammond and Purcell Consulting, San

Francisco, USA

1420 - 1440 hours

“Industry Lobbying of the Public Sector and other Tactics"

Dr Y. Saloojee, Executive Director, National Council Against

Smoking, Johannesburg, South Africa, and Dr Elif Dagli, Professor

of Medicine, Marmara University Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

1530 - 1545 hours

"Case Study in Consumer Protection from Tobacco in South East

Asia”

Dr Sri Ram Khanna, Managing Trustee, VOICE, New Delhi, India,

and Ms Mary Assunta Kolandi, Media Officer, Consumers

Association of Penang, Penang, Malaysia

"Multisectoral and Intersectoral Approach to National Tobacco

Control"

Dr Kishore Chaudhry, Deputy Director, Indian Council of Medical

Research, New Delhi, India

“Women, Children and Tobacco"

Dr Mira Aghi, Consultant to WHO and other UN Agencies, New

Delhi, India

Break

1545- 1800 hours

Open discussion

1440- 1500 hours

1500- 1515 hours

1515- 1530 hours

Conference Programme (contd.)

Sunday, 9 January 2000

Plenary III: Global Tobacco Control Law: Towards a Legal and Regulatory Framework

Co-chaired by Ms Indira Jaisingh and Dr Srinath Reddy

0900 - 0915 hours

0915-0930 hours

0930 - 0945 hours

0945- 1000 hours

1000- 1015 hours

1015- 1230 hours

“International Legal and Policy Framework for WHO Framework

Convention on Tobacco Control”

Mr William Onzivu, Fellow, WHO Geneva

“Regulation of Tobacco Products”

Mr Mitchell Zeller, US Federal Drug Administration Rockville, USA

“The Prospects for Globalizing Tobacco Litigation”

Ms Roberta Walburn, Senior Fellow, WHO Geneva

“The Application of International Law into National Law, Policy

and Practice: Lessons for the Framework Convention on

Tobacco Control"

Ms Judy Obitre-Gama, Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Makerere

University, Kampala, Uganda

Break

Open Discussion and

Introduction to the Working Group Process

1230- 1330 hours

Lunch/Press Technical Brieting/Legal Implications of Tobacco

Industry’s Arguments vis-a-vis the FCTC

1330 - 1630 hours

WORKING GROUPS

Chairpersons, Facilitators, Rapporteurs, and Panelists to be

announced

Working Group 1- “Economic Implications of Tobacco

Production and Marketing”

Working Group II - “Towards establishing National Institutions for

the FCTC: Legal, Policy and Practical

Options”

Working Group III - “Addressing Industry Tactics”

Working Group IV - “The Prospects for Globalizing Tobacco

Litigation”

Plenary IV: Conference Recommendations and Chairs’ Summaries

____________ Co-chaired by Ms Indira Jaisingh and Dr Srinath Reddy

1645- 1745 hours

Working Group Recommendations - Reports by Rapporteurs

1745- 1755 hours

Chairs’ Comments

1755 - 1805 hours

Adoption of Declaration

1805- 1825 hours

Conference Synthesis

Dr Derek Yach, Project Manager, Tobacco Free Initiative, World

Health Organization

Closure

1825 - 1845 hours

e

e

pH S-T-

WORKING GROUP I

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIOINS OF TOBACCO

PRODUCTION AND MARKETING

1. KAMAL KABRA

INDIA (CHAIRMAN)

2. DR G. WOELK

ZIMBABWE (RAPPORTEUR)

3. DR SETH KORANTENG

GHANA

4P.R. PANCHAMUKHI

INDIA

5. R.N. TRIVEDI

INDIA

6. DR BABU MATHEW

INDIA

7. DR G.K. RATH

8. MATHEW ALLEN

9. DR GAJA LAKSHMI

10. DR MANGUELE

INDIA

NEW ZEALAND

INDIA

MOZAMBIQUE

ll.PEMA UDON

BHUTAN

12. S.K. OJHA

INDIA

13. K.K. MARWAHA

INDIA

14. DR INDIRA CHAKRAVARTY

INDIA

15. ANTHONY SO

16. MS MAI YA RANJITKAR

USA

NEPAL

20. BYAKUTUIGA TANEFU

UGANDA

21. JUDY OBITRE-GAMA

UGANDA

22.DR K.N. SHAFIUL ALMA

BANGLADSH

23. DR NISHI RANJAN TALUKDER

BANGLADESH

24. AKHTARI BEGUM

BANGALDESH

25. DR FATIMA EL-AWA

WHO/EMRO

26. YOUNG-JOO JIN

SOUTH KOREA

27. DRD.M. KIIMA

KENYA

28. PROFS.K. VERMA

INIDA

29. HECTOR SOLIMAN

PHILIPPINES

30. SAIFUDDIN AHMED

BANGLADESH

31. ATIE W. SOEKANDAR

INDONESIA

32. YUSINIAR N. DARWIN

INDONESIA

33. DR TIN WIN MAUNG

MYANMAR

34. MR MIFUNDU DU BILONGO

35. KATUALA

RDC

RDC

36. DR F N. ENYINE

CAMEROON

37. MR WIN MYINT

MYANMAR

38. ZEWDIE BELAY

ETHIOPIA

39. MRS KRISSANA TREEYAMANERATANA

THAILAND

pH S’. p

WORKING GROUP III

ADDRESSING INDUSTRY TACTICS

. '

g •

h

1. E. DAGLI

TURKEY (CHAIRMAN)

2. DR SRI RAM KHANNA

INDIA (RAPPORTEUR)

3.DRS.G. VAIDYA

INDIA

4. Y. SALOOJEE

5. J. MBATIA

MALDIVES

6. D. Me CARGO

7. A. AFAAL

MALDIVES

8. AGHIMIRA

INDIA

9. P.C. GUPTA

INDIA

10. S. CHANTORNVONG

THAILAND

11. MARY ASSUNTA

MALAYSIA

12. DR SRI RAM KHANNA

INDIA

13. ROSS HAMMOND

USA

14. THELMA NARAYAN

INDIA

15. JEFF COLLIN

UK

16. MIMTA MOLINARI

ARGENTINA

17. DEBRA EFROYMSOiN

BANGLADESH

18. GARRETT MEHL

19. MAG ARETHA HAGLUND LUK JOSSENS

USA

BELGIUM

20. S,. HONG TIY

FIJI

21. NAIMUL HAQ

BANGLADESH

22. BUNGON RITHIPAKDEE

THAILAND

Working Group IV

THE PROSPECTS FOR GLOBALISING TOBACCO

LITIGATION

1. ELANA MAYSHAR

2. JOSE MARIA OCHAVE

ISRAEL (CHAIRMAN)

PHILIPPINES (RAPPORTEUR)

3. PRAM I LA PATTEN

MAURITIUS

4. LOUISE DELANY

NEW ZEALAND

5. PROF R.K. NAYAK

INDIA

6. T. OBIDAIRO

NIGERIA

7.FILOMENA WILSON

ANGOLA

8. V.S. REKHI

9. YASANTHA KODAGODA

INDIA

SRI LANKA

10. RANI JETHMALANI

INDIA

11. AISEA TAUMOEPEAU

TONGA

12. ZEEBA HIRJI

13. MANOHARAN DE SILVA

14. LINDA BAILEY

15 LULAMA MNUMZANA

INDIA

SRI LANKA

USA

SOUTH AFRICA

TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR WORKING GROUPS.

I: ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF TOBACCO PRODUCTION AND

MARKETING.

Objective:

To present the World Bank Report on the economic effects of tobacco production and

marketing and to discuss the arguments advanced by the Bank.

Expected Outcome:

In view of the World Bank Report;

The economic implications of the report for global and national tobacco control

would have been ascertained.

2.

Practical guidelines for implementing the World Bank Report in Developing

countries would have been compiled for the FCTC.

1.

II: “TOWARDS ESTABLISHING NATIONAL INSTITUTIONS FOR THE

FCTC: LEGAL AND POLICY OPTIONS”

Objective:

To explore various options using law', policy or practice to establish national

institutions for development of the FCTC/national tobacco controls in states of the

developing world.

Examine any difficulties that may be encountered, suggesting feasible and practical

solutions to the problems.

Expected Outcome:

1. All relevant issues relating to establishment of these institutions and and

countermeasures would have been identified.

3.

Develop short practical guidelines for establishment of national Institutions

in the developing world to further FCTC process and later implementation.

zlil: ADDRESSING INDUSTRY TACTICS.

.

(.-----------

"

-————

----------—------------- _

Objective:

To discuss and document the nature of tactics used by the tobacco industry to promote

its products in the developing world. To determine the impact of industry tactics on

tobacco control policies.

Expected Outcome.

1. In view of the complexities of the problem, effective options to counter industry

tactics would have been documented.

2. A short practical guideline on effectively countering the industiy tactics

w ould have been developed.

IV: THE PROSPECTS FOR GLOBALIZING TOBACCO LITIGATION.

Objective:

To discuss and identify all conditions and factors for ensuring successful transnational

claims against the tobacco industry by or for the developing world.

Discuss any obstacles involved and solutions to these problems.

^pected Outcomes:

1. All prerequisites for successful transnational claims against the industry would

have been ascertained.

2. A set of short guidelines would have been developed to undertake litigation

against the industry.

Table 1: An outline of Tobacco Industry Tactics

Tactic

-*

**

^j^c

r c >5

1. Intelligence gathering

Monitor opponents &jSocial trends to anticipate future

challenges.

5

fL°~

~ H

2. Public Relations

To mould public opinion using the media to promote

pro-industry positions. —

3. Political Funding

Use donations to win votes and legislative favours from

politicians.

Cut deals and influence political process.

4""Jv- (G- A-fV

c. U \

5. Consultancy programme

To produce “independent” experts critical of tobacco

control measures.

6. Smokers Rights Groups

Creating impression of spontaneous, grassroots public

support.

7. Creating .Alliances

Mobilising farmers, retailers, advertising agencies to

influence legislation.

8. Intimidation

Using legal and economic power to harass and frighten

opponents.

9. Philanthropy

Buys friends and social respectability-from arts, sports

and cultural groups. +f

s■

'

10. Litigation

Challenges laws.

11. Bribery

Corrupts political system. Allows industry to by-pass

laws

12. Smuggling

Undermines tobacco excise tax policies and increases

profits.

13. International treaties

Using trade agreements to force entry into closed

markets.

j-A ,-J C-A

PROJECT PROPOSAL

Introduction

Tobacco is a major cause of deaths the world over.

3.5 million people around the

world die due to consumption of tobacco in some form or the other. By the year

2020. it is predicted that globally, 10 million people would die as a consequence of

tobacco comsumption and 70% of such deaths would occur in developing countries.

Every year around 630,000 people in India succumb to death due to consumption of

tobacco in some form or the other. Her/His treatment of the various diseases as a

result of tobacco consumption, thus imposing a heavy burden on the family

financially, psychologically as well as socially. The effects of passive smoking on

side stream smoke being immensely potent would have deliterous effects on the

health of the citizens which is highly compromised by the highly polluted towns and

cities. Respiratory diseases occupy a major stake in the disease circle in Bangalore,

the capital of the state of Karnataka, India surpassing all other cities. Therefore the

need to study the tobacco problem in this state. Tobacco indeed contributes to the

economy of the state and to the country in turn, through taxes and duties. The area

under tobacco cultivation in the year 1997-1998 in the state of Karnataka was 69,500

hectares from which 60,800 tons of tobacco was produced or approximately

875kg/hectare. The revenue of the state/country spent on treating tobacco related

diseases far outweigh the revenue earned from it by roughly three to three and a half

times. This puts an additional burden on the economy of the country. Each worker

gets paid about Rs.80 /- (i.e., less than $2) for a day’s work. Their working as well as

housing conditions being deplorable drastically affects their health. They generally

cannot put their children in schools which are usually very far away. Mother’s cannot

nurse their infants at regular intervals, because they are left behind in their homes to

be looked after by another sibling and the distances from their homes to their work

C:\OFFICBTobaxo\PROIECT PROPOSAL - totaocadoc

places ranging from nearly a kilometer to more which they cover by foot. God forbid

if one of the family members get sick! Hospitals are very far away. The sick person

being too sick to walk, neither take a bus which again would be far away and not

punctual, nor take a bullock cart to the hospital would prefer to rest at home till

she/he is in a condition to reach the hospital. Again the loss of pay from the number

of days off work in addition to the hospital bills constantly haunting the sick person.

Therefore for every bit of tobacco consumed, some poor worker somewhere would be

suffering.

As a result, a substitute to the tobacco crop ought to be found as an

alternative for the poor workers and fanners concerned in our attempts to phase out

the crop.

Unfortunately, youth in the age groups of 12-22 form the major percentage of people

taking up this habit. This is of serious concern to the nation as the popular saying

goes, “Today’s youth, tomorrow’s citizens”.

On the contrary, some stem measures

need to be taken to tackle this global problem due to the export chains and hence it

would be necessary to use the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control

developed by the WHO to counter this issue globally.

Genera! objectives

i)

To analyze the public health, economic and social dimensions of the tobacco

problem in the state of Karnataka, India.

ii)

To study the biddy industry in the state of Karnataka, India, its economic and

social dimensions and its global outreach through exports.

CAOFFICE\Tobaooo>PROIECT PROPOSAL - tatexo <fcc

Specific objectives - To study the bidi industry in the state of Karnataka, India.

i)

its economic contribution to the state,

ii) The working conditions of its employed workers

iii)

Its tax exemption

iv)

Its turnover

v)

Local sales in India, and

vi)

Its global outreach through exports and its marketing strategies.

Methodology - Collection of data from (i) Primary, and

(ii) Secondary sources.

Time frame - 1st October 1999 - end of February 2000.

Budget -

Q\OFHCE\Tol«co\PROJECr PROPOSAL - tobacco,doc

pH S’-8

1

’ v*'

WHO International Conference

on Tobacco and Health, Kobe—

“Making a Difference to Tobacco and Health:

Avoiding the Tobacco Epidemic in Women and Youth”

ADOPTED

18 November 1999

Kobe, Japan

14 to 18 November 1999

http://www.wlio.int/toh

KOBE DECLARATION

We, women and youth leaders, non-governmental organization representatives, government delegates, media

professionals, academics, health professionals, scientists and policy-makers, gathered in Kobe, Japan in

November 1999 at the WHO International Conference on Tobacco and Health, are gravely concerned that:

1.

The tobacco epidemic is an unrelenting public health disaster that spares no society. There arc already over

200 million women smokers, and tobacco companies have launched aggressive campaigns to recruit women

and girls worldwide. By the year 2025, the number of women smokers is expected to almost triple. Tobacco

is the one product that kills its consumers when used as recommended. There arc four million deaths per yea

11,000 per day, related to tobacco. If current trends continue, the world will see a growth rate that turns

tobacco use into the single largest cause of death and disability. It is urgent that we find comprehensive

solutions to the danger of tobacco use and address the epidemic among women and girls. Tobacco has been

identified as a contributing factor to gender inequity and undermines the principle of women and children’s

right to health as a basic human right.

2.

The scientific evidence has shown conclusively that both smoked and smokeless tobaccos contain

toxins that cause multiple fatal and disabling health problems throughout the life cycle. Women who

smoke have markedly increased risks of cancer, particularly lung cancer, heart disease, stroke,

emphysema and other fatal diseases. Women experience gender-specific risks from tobacco and

Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) such as negative impact on their reproductive health and

complications during pregnancy.

3.

Tobacco-related diseases lead to high morbidity rates worldwide, contrary to the goals of sustainable

development and well being for all. The use of tobacco results in a net loss of US $200 billion per year

to the global economy, with half of these losses occurring in low-income countries. There arc

immeasurable personal, social and economic costs to women and children particularly those living in

poverty in low-income countries and in rural settings.

4.

Transnational tobacco companies have implemented well-formulated and deliberate strategies to

expand tobacco markets among women and children, particularly in populous and developing

countries. The tobacco industry is manipulating the process of globalisation for profit. The tobacco

industry promotes the false association of tobacco with images of health, liberation, slimness and

.modernity. Multinational tobacco companies have extended their reach into low-income countries at a

time when structural adjustment policies are often resulting in economic hardship and severely

limiting the health and educational resources of these countries.

5.

There is an urgent need for governments and the international community to develop effective gender

specific tobacco control strategies and to allocate sufficient funds for tobacco control programmes that

also reach poor women and girls. Although there are some countries that have implemented effective

strategies against tobacco, such as increased taxation and legislation to ban tobacco advertising, many

governments still have a direct association with the tobacco industry as producers, exporters or

subsidizers.

•

fVe are resolved to:

6.

Demand that the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control incorporate gender-specific concerns

and perspectives and include a women’s protocol; require the active participation of women delegates

and NGOs in the development and monitoring of the Convention and its related protocols; and

demand that the Convention and its related protocols are ratified by all member states without

reservations that are incompatible to the spirit and the letter of the Convention.

7.

Recommend that the governments and the private sector refrain from supporting the tobacco industry

and restructure financial policies to raise taxes ad valorem on all tobacco products to a minimum level

of 2/3 of the price of tobacco; promote policies that broaden employment opportunities for women and

farmers and provide for transitional programmes beyond the tobacco industry; and require that

increased tobacco revenues be used for tobacco control programmes as well as for public sporting and

cultural events previously sponsored by the tobacco industry.

8.

Demand a global ban on direct and indirect advertising, promotion and sponsorship by the tobacco

industry across all media and in all forms of entertainment; and demand public funding for counter

advertising that disconnects women’s liberation and tobacco use and that reaches women and girls in

all cultural contexts. The use of a tobacco-registered brand name, logo, or trademark on non-tobacco

items as well as vending machines that dispense tobacco products should be banned globally.

9.

Ensure that gender equality in society becomes an integral part of tobacco control strategies and

promote women’s leadership which is essential to success.

10.

Develop gender-specific strategies, with regard for diversity and the needs of women and girls in

different cultural contexts. These should include the creation of smoke-free environments, the

reduction of exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS); gender-sensitive cessation methods;

and the adoption of effective strategies to raise public awareness and to reduce tobacco initiation and

use.

11.

Mobilize NGOs, communities, religious groups, media, women’s and youth organizations, and the

scientific communities in the fight against tobacco products through a multidimensional approach.

Monitor the media to ensure accurate and balanced image of tobacco in reporting women’s health

issues.

12.

Call for effective health education in tobacco use and control including media literacy, at all levels of

formal and informal education; invest in overall education in women and girls as a mechanism for

development of skills, empowerment and for improving their capacity to fight against tobacco.

Education and training programmes in tobacco control should be implemented for health care

professionals.

13.

Increase public funding for research and advocacy on women and girls and tobacco; and improve

dissemination of research results to the general public.

14.

Ensure devolution of the tobacco control strategy of WHO and UN agencies and their regional and

country offices; demand that WHO develop and disseminate tobacco control information and

guidelines for best practices worldwide especially in transition and low-income countries.

15.

Incorporate recommendations to combat the negative impact of tobacco in sections dealing with

“women and health” and “the girl-child” in the UN General Assembly Special Session on Women

2000; and similarly incorporate environmental aspects of tobacco control in the review of the Earth

Summit in 2002, and in other relevant UN follow-up sessions to international conferences.

x6. Uphold the principle of women and children’s right to health as a basic human right and build on the

progress made at the Children’s Summit; the UN Conferences on Environment and Development;

Human Rights; Population and Development; the Social Summit; the Fourth World Conference on

Women; Habitat; and the Food Summit. Build on existing documents such as the Convention on the

Rights of the Child; Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women;

Human Rights Covenants; the Draft Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; and WHO

Assembly resolutions highlighting gender, health and development; Declaration of ALMA ATA and

the Ottawa Charter on Health Promotion.

January 6, 2000

THE TIMES OF INDIA

Tobacco consumption worries WHO planners

Th« Times of India News Service

NEW DELHI: The health costs of

tobacco-relatcd diseases are far

greater than the income generated

from tobacco as a cash crop, says a

new study by the Indian Council of

Medical Research (ICMR).

The average cost of one case of to

bacco-related cancer is Rs 3.5 lakh.

Last year alone, 1.63 lakh people de

veloped cancer due to tobacco use,

says the study conducted by

ICMR's deputy director general,

Kishorc Choudhary.Tic study was

conducted at two centres, Delhi and

Chandigarh.

As it is, says the World Health Or

ganisation (WHO), India may be

heading for a tobacco epidemic.

One-fifth of the 2.8 million people

who die each year the world over

from tobacco-related diseases are

Indians. Nearly 50 per cent of Indian

males over the age of 15 are smok

ers, it says.

Therefore, to check the increasing

cigarette consumption in develop

ing countries, WHO is using interna

tional law for the first time to reduce

damage to health caused by tobacco

products. An international treaty is

being drawn up for tobacco control.

To discuss these issues, a three-'

day international conference is be

ing organised in Delhi from Friday.

Tie conference is being sponsored

by the Indian government and

WHO.

WHO says in the next two to

three decades seven million people

will die of tobacco-relatcd illnesses

in the developing countries. Tie to

bacco pandemic is dcscrilied as “one

of the major public health disasters

of the 20th century".

However, policy-makers realise

that reducing tobacco consumption

will not be easy. Union health secre

tary J A Chowdhury says curbing

the consumption of tobacco-based

products is a complex issue as tobac

co cultivation is very remunerative.

Therefore,strategies will need to be

worked out for providing alterna

tives to farmers. Tie conference

here will examine issues from the

perspective of a developing country.

What is little known to people is

that there arc about

chemical

substances in tobacco smoke, of

which -138 can produce cancer, the

most dangerous being nicotine, to

bacco tar and carbon monoxide.

Nicotine is an alkaloid that affects

the central nervous system mid is

probably the cause of smokers' de

pendence on the habit.

Details at www.tlmosonndla.com

Inauguration Ceremony

Please note that all the delegates should carry their invitation cards and the

badges for the inaugural ceremony. Due to security reasons no other personal

items such as hand bags or equipment such as celluar phones and lap top

computers are allowed into the hall. Please read the instructions given at the back

of the invitation cards for more details.

Travel inquires and ticket re-confirmations

Our official travel agents, M/s INDTRAVELS will be available to assist you with your

ticket reconfirmations. Travel desks at Ashok Hotel and Vigyan Bhawan, will be set up at

the following times.

Date

Venue

Time

Friday, 07 January 2000

Ashok Hotel

Saturday, 08 January 2000

Vigyan Bhawan

09.00 - 17.30 hrs.

Sunday, 09 January 2000

Vigyan Bhawan

09.00 - 17.30 hrs.

09.00 - 17.00 hrs.

Kindly note that most airline offices close for the weekend by 13.00 hrs. on Saturday

through Sunday. So please contact the INDTRAVEL desk on Friday 07 January to

avoid any inconvenience.

pH SHO

WI-IO/DG/SP

Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland

Director-General

World Health Organization

WHO’s International Conference on Global Tobacco Control Law:

Towards a WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

New Delhi, India, 7 January 2000 (17h35)

Mr Prime Minister,

Distinguished guests,

It gives me great pleasure to be in India today - this is a country and a people close to my heart. I am

especially pleased to be speaking to an audience of some of the world’s best legal and public health

experts.

We come from a wide range of backgrounds, such as public health, medicine, law, media, economics

and social sciences. What has brought us here to Delhi is our common resolve to highlight the grave

problems arising from tobacco in the developing world. This meeting will explore possible means to

address these problems, taking into account developing country perspectives. It will be one of many

important contributions over the next months and years towards a strong international legal tool to

fight tobacco, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Ladies and gentlemen,

India, with its myriad of cultures and its complex economic and social realities, in many ways mirrors

our new globalized world. But despite its diversity, its disparities and its conflicts, a strong sense of

unity - has kept this immense nation - which harbors nearly one sixth of humanity - together in a

viable and vivid democracy.

The rest of the world is only slowly waking up to this realization that all of us, no matter the physical,

cultural or economic distance, are dependent upon each other. One region’s poverty is another region’s

lost opportunity. One area’s industry may be another area’s environmental disaster, and one country’s

disease outbreak today, may be another country’s epidemic tomorrow.

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development, which I had the privilege to chair,

came up with the concept of ‘’sustainable development” on the basic premise that development needs

of nations must be met in a way that allows future generations to fulfill their own aspirations.

Enshrined in this concept was the whole notion of solidarity, the right to knowledge and access to

basic life-sustaining information for all nations and people. That idea is now institutionalized globally

in a series of environmental treaties. It has entered the vocabulary of policy makers.

We will add health to that illustrious list.

The importance of the role of health in overall development is being rapidly embraced by governments

around the world. It is a conceptual shift not unlike that which took place with the environment 25

years ago. Increasingly, governments realise they need to integrate health into the broader context of

development. They are also beginning to look at investments in health as more than simply a mere

consumption expenditure. Instead, health is increasingly being seen as a major opportunity for growth,

productivity, human progress and poverty alleviation.

My point of departure is a broad reading of the role of health in development. WHO is indeed the

specialised agency on health - but the purpose of our work is not only to combat ill-health - although

WHO/DG/SP

that remains key - it is also to promote healthy populations and communities - and indeed to

demonstrate how wise health interventions can spur development.

There was a period in development thinking - not so long ago - when access to public services, such as

health and education, would have to wait until countries had developed a certain level of physical

infrastructure and achieved a certain level of economic strength. Once countries had become fully

industrialised - large outlays on health care seemed appropriate and necessary. Indeed, it was seen as a

sign of national prosperity and success.

Experience and research over the past few years have shown that such thinking was at best simplified,

and at worst plain wrong.

We have seen that developing countries which invest relatively more on health in an effective manner

are likely to achieve higher economic growth. In East Asia, for example, life expectancy increased by

over 18 years in the two decades that preceded the most dramatic economic take-off in history. A

recent analysis for the Asian Development Bank concluded that fully a third of the Asian “economic

miracle” resulted from these gains.

We have also observed how health spending in some of the world’s richest countries can reach very

high levels and still not provide necessary and quality health services to all their citizens.

Health is not only an important concern for individuals, it plays a central role for the society in

achieving sustainable economic growth and an effective use of resources. And health is even emerging

as an important element of national security.

With globalization, all of humankind today paddles in a single sea. There are no health sanctuaries.

Diseases cannot be kept out of even the richest of countries by rearguard defensive action. The

separation between domestic and international health problems is losing its usefulness as people and

goods travel across continents. Two million people cross international borders every single day, about

a tenth of humanity each year. And of these, more than a million people travel from developing to

industrialized countries each week.

This is not only an issue of infectious diseases. With an explosion of international trade, travel and

media, new cultural influences spread faster than ever before, driven by economic aspirations,

entertainment and advertising. Many of the effects are positive, but we also see drastically negative

effects, such as unhealthy changes in diet - and the rapid spread and increase of tobacco-use.

Disease and death do not stop at national borders, but still our efforts to fight them are far from being

sufficiently international. The time has come for both health and foreign policy to reflect the needs of

the world’s public with greater emphasis on international health security and its contribution to world

peace. Foreign policies and international business practices must acknowledge transnational threats of

disease, the dangers of trade in products and technologies that are harmful to health, economic and

health disparities between and within countries and population growth. Countries must collaborate to

develop strategies that ensure sustainable human security.

As the world’s leading health agency seeking value for our constituents we have chosen our setting we will play an active role in this work; as a facilitator, as a provider of evidence and best practices and as a moral compass.

Ladies and gentleman,

One of the most important political legacies of this century has been the universal ideal of human

rights that are now irreversible as tenets of international law. The past 30 years have seen the birth of

2

WHO/DG/SP

undreds of organizations around the world that have given a voice and a focus to issues that affect

our lives on a daily basis. Our search for justice is as old as we are. Our search for life in harmony

with laws - whether they be natural laws or those that have developed over centuries - is as old as

humanity himself. Access to basic health is, in the final analysis, a search for justice.

It is my firm belief that where there is no vision, there is no progress. The success of our vision lies in

the hands of our Member States.

As nations feel increasingly compelled to co-operate with each other to solve their problems, the

development of binding global public health norms and commitments will become crucial. Although

international health law is still in a nascent and dynamic stage of development, it must address both

the positive and negative health impact of globalisation. Consequently, health development in the 21st

century is likely to make wider use of international legal instruments to take advantage of the

opportunities afforded by global change and to minimize the risks and threats associated with

globalisation.

Today, our focus is tobacco. But the work we do on tobacco has wider consequences. As the

composition of the global burden of disease changes, so must the emphasis of our work. In addition to

continue with the past century’s very successful effort to limit or eliminate infectious diseases, the

work we are doing on a Framework Convention on Tobacco Control stakes out the way disease must

increasingly be fought and prevented in this brand-new century. This is the first time WHO is

exercising its constitutional right to negotiate a set of globally binding rules. The Framework

Convention is a product and a process and a public health movement.

Turning principle into practice is not an easy task, but we will lead the way and as I said, I am

counting on your help. Our task is not to produce worldwide regulations. It is to build a International

legal framework which will assist and support countries in their national regulation process.

The success of our approach will depend on political commitment, capacity building in public health

law and economics, public support and effective enforcement. Legislation and regulation have to

strike a balance between individual freedom and public needs and interests.

For the next few days, you will hear about the science, economics and politics of tobacco control. We

know that tobacco use is a risk factor for some 25 diseases. It was here in India in 1964 that the first

link between oropharyngal cancer and chewing tobacco was identified. Studies from eastern India

were the first in the world to link palate cancer to the chewing of tobacco.

As the recent report of the World Bank has clearly documented, the risks to health and health systems

from tobacco are widely underestimated. So are tobacco industry tactics. When I first looked into the

issue of tobacco use world-wide I was unprepared for what I was to learn about the extent and manner

in which the tobacco industry was marketing a product that killed half of its consumers. I was appalled

to see how the tobacco industry had subverted science, economics and political processes to market a

lethal and inherently defective product that imposed a massive burden of disease and death on

countries.

I am outraged by what I learn with each passing day about the tobacco industry from previously secret

documents that have now come to light mainly due to court cases in the United States, in particular

Minnesota. I want to use this platform to call on national and international public health experts to

work with their Constitutions as well as their countries’ international commitments to help prevent and

combat this man-made epidemic. Let us craft the world first truly viable public health Convention.

Tobacco is freely allowed to kill one person every eight seconds. That is four million preventable

deaths per year. Today in India, tobacco kills 670,000 people every year. In China, if present smoking

patterns continue, about a third of the 300 million Chinese males now aged 0-29 will eventually be

3

WHO/DG/SP

killed by tobacco. Countries like Canada and Sweden that had long bucked the tobacco epidemic now

see it reappearing again. No country and no people are safe from the to acco men

I have occasionally heard comments to the effect that smoking is mainly an industrialized country

problem and that WHO should focus its energies on fighting the traditional peases of poverty, such

as malaria, tuberculosis and childhood diseases. Such comments are understan

e u mism orme .

If unchecked and unregulated, by 2030, tobacco will kill 10 million people each year Seventy percent

of those deaths will occur in the developing world, with India and China in the lead, If nations do not

act individually and together, in the next 30 years, tobacco will kill more people than the combined

death toll from malaria, tuberculosis and maternal and child diseases. Every tobacco related death is

preventable. That is our message. That is our challenge.

Fifty years ago the world found a solution for polio. Today we are on the verge of eradicating it. Fifty

years ago scientists and researchers linked tobacco to cancer and other diseases. I wish I could tell you

that the world has risen to the tobacco challenge as vigorously and unequivocally as it fought polio.

The unacceptable reality about tobacco is that the health community has lost out to the tobacco

industry aggressively seeking new markets and newer victims. The world will have little cause to

rejoice over the health gains of the eradication of polio if we continue to remain unprepared for, and

indifferent to, new challenges such as the one posed by tobacco.

One of the first things that I did at the WHO was to ask our Member Countries to give us a mandate to

negotiate the Framework Convention. This new legal instrument is expected to address issues as

diverse as tobacco advertising and promotion, agricultural diversification, product regulation,

smuggling, excise tax levels, treatment of tobacco dependence and smoke-free areas.

The Framework Convention process will activate all those areas of governance that have a direct

impact on public health. Science and economics will mesh with legislation and litigation. Health

ministers will work with their counterparts in finance, trade, labour, agriculture and social affairs

ministries to give public health the place it deserves. The challenge for us comes in seeking global and

national solutions in tandem for a problem that cuts across national boundaries, cultures, societies and

socio-economic strata.

An early ally has been UNICEF and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. While the Convention

on the Rights of the Child does not explicitly include tobacco, several of its articles address over

arching values essential to safe and healthy development of children and as of this year, the States’

reporting guidelines have now been amended to include tobacco.

For tobacco, this means that the interests of the child take precedence over interests of the tobacco

industry. Later as I share with you some tobacco industry tactics to promote tobacco to children, you

will see why this is important.

Within the United Nations Family, The World Bank is an essential partner in global tobacco control.

Their 1999 report effectively shows that over the long term economies will benefit from tobacco

control. They highlight a basic economic fact. If people stop spending on tobacco, they will spend on

other goods and services that will generate more jobs and revenue than those from tobacco.

We also have a close working relationship with FAO. Together, we are reaching out to tobacco

fanners to ensure that when successful tobacco control reduces demand for tobacco the economic

consequences will be minimized.

Our decision to use legally binding mechanisms to circumscribe the global spread of tobacco on the

one hand, and to regulate the product itself on the other, is based on sound science and irrefutable

documentary evidence. The science that underpins our work is unequivocal - a cigarette is the only

WHO/DG/SP

freely available consumer product which, when consumed as intended by manufacturers, kills. Let us

never forget that.

Nicotine is addictive. A cigarette is not just tobacco leaves rolled in a strip of paper. It is a highly

engineered product. The tobacco industry has studied our saliva and central nervous systems to

determine the right dose of nicotine to deliver so that addiction occurs and is sustained. Other tobacco

products, whether they be beedies, snuff, gutka or spit tobacco, are no less addictive - nor lethal.

Imposing international norms on a global industry that seemingly without qualms can make huge

profits from a product that kills is not an easy task. It is our firm belief that to develop a truly

meaningful global treaty to control tobacco, our Member States must have a clear understanding of the

tobacco industry and its tactics.

Fifty years is a blink of time in a millennium, but fifty years is a long time to sustain a deliberate

deception that causes death and disease. For almost fifty years, the tobacco industry has known that

tobacco products cause deadly diseases. I am speaking to an audience of lawyers and public health

experts - I chose my words carefully. The tobacco industry which acts as a global force is in the

business of selling deception. Deception in science, public health and economics. Internal tobacco

industry documents that have now become public bear eloquent testimony to this.

Tobacco litigation began in the United States 1954. But the major breakthrough came in the 1990s - in

the States of Mississippi and Minnesota - with the revelations of millions of pages of documents

forced from the files of the tobacco industry and with the framing of different types of legal theories

that focused on the conduct of the tobacco industry.

For us, these documents show how and why the tobacco industry has been so successful in defeating

public health objectives in the past and provide valuable lessons into how the public health community

must come to terms with the tobacco industry to make progress in future. We believe the tobacco

industry has fractured the tobacco issue by playing different tunes in different countries. In one it is

labour, in another it is farmers, in a third it is marketing rights. We believe that through our

Constitution and that of our Member States, we can restore the global and national picture so that the

truth can emerge to benefit public health for all.

Consider this internal tobacco industry discussion. A document written by a tobacco industry lawyer

in 1980 sets out some of the reasons for the tobacco industry’s refusal to publicly admit that smoking

causes disease. The document was written at a time when the British and American Tobacco Group

companies were considering changing their public stance on the issue of causation of disease. The

lawyer opposed such a change, and wrote:

“If we admit that smoking is harmful to 'heavy ’ smokers, do we not admit that BAT has killed a lot of

people each year for a very long time? Moreover, if the evidence we have today is not significantly

different from the evidence we had five years ago, might it not be argued that we have been wiljully

killing our customers for this long period? Aside from the catastrophic civil damage and governmental

regulation which wouldflow from such an admission, Iforesee serious criminal liability problems

Tobacco companies also denied for decades that smoking was addictive. In private, they recorded in

the fifties that smoking was addictive. In 1961, a top industry scientist wrote, "... smokers are nicotine

addicts” In 1963, an industry lawyer wrote, “(NJicotine is addictive. We are, then in the business of

selling nicotine, an addictive drug ...” In 1979, a tobacco executive considered the hypothesis that

“high profits ... associated with the tobacco industry are directly related to the fact that the consumer is

dependent upon the product”

The internal documents also demonstrate that the tobacco industry intentionally designed cigarettes to

exploit their addictive potential. While nicotine is a naturally occurring component of the tobacco

5

WHO/DG/SP

plant, the modem cigarette is a highly engineered and sophisticated product in both manufacture and

design. Decades ago, the tobacco industry began to control and manipulate the level and form of

nicotine in cigarettes in a variety of ways.

Publicly, the tobacco industry’ maintains that it does not want youth to smoke. Privately the tobacco

industry' has long recognised that the preservation of its market depends upon recruiting youth. As one

document stated, “Younger adult smokers are the only source of replacement smokers ... If younger

adults turn away from smoking, the industry must decline, just as a population which does not give

birth will eventually dwindle” The tobacco industry documents are replete with discussions of

marketing to youth and the need to increase market shares by enlisting youth.

The documents are an underused public health tool. But that is about to change.

There is some type of tobacco litigation underway in at least 15 countries ranging from personal injury

class action litigation in Australia to health cost recovery in Canada to public interest petitions in

India.

Last October I called for a preliminary inquiry into whether the tobacco industry has exercised undue

influence over UN-wide tobacco control efforts including interfering with WHO’s work. Later this

year I have called for a meeting of international regulators to set in motion the process of regulating

tobacco. The jigsaw is falling into place.

One of the primary' objectives of the tobacco industry is to frame tobacco use as an individual and

behavioral decision. Adults can chose for themselves if they have full access to information. The same

does not apply to children and adolescents. On a given day, between 82,000 and 99,000 young people

- sometime as young as 8 - start smoking or chewing tobacco. Over eighty percent of smokers started

before they were 18. By the time they find out, it is too late. The addiction has taken control.

The good news is that we can buck and reverse the global tobacco trend. We know what works and

how. Taxes work and the young are especially susceptible to increased prices. Advertising and

sponsorship bans work. Smoke free policies work.

Such policy interventions could, in sum, bring unprecedented health and economic benefits. WHO’s

message is that there is a political solution to tobacco and it is routed through policy interventions and

political vision.

The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is a pathfinder in public health. It will assist in

placing health at the top of national and international agenda and will create a debate on the wider

issues and solutions to health problems.

We owe this to ourselves. We owe this more to future generations. Let us never forget that public

health is a search for equity, solidarity and justice.

Thank you.

6

Ph s', i

Inaugural Session of the

WHO International Conference on

Global Tobacco Control Law :

Towards a WHO Framework Convention

on Tobacco Control

7-9 January 2000, New Delhi, India

Address by

Dr Uton Muchtar Rafei

Regional Director, WHO South-East Asia Region

World Health Organization

Regional Office for South-East Asia

New Delhi

Inaugural Session of the

WHO International Conference on

Global Tobacco Control Law :

Towards a WHO Framework Convention

on Tobacco Control

7-9 January 2000, New Delhi, India

Address by

Dr Uton Muchtar Rafei

Regional Director, WHO South-East Asia Region

World Health Organization

Regional Office for South-East Asia

New Delhi

Your Excellency, the Honourable Prime Minister of India

Honourable Minister of Health and Family Welfare

Honourable Minister of Law, Justice and Company Affairs

Secretary of Health and Family Welfare of India

Director-General of Health Services

Director-General, World Health Organization,

Distinguished

gentlemen,

experts,

dear

colleagues,

ladies

and

In the century that just passed, humanity has, without doubt,

witnessed

tremendous

achievements.

Unprecedented

scientific advances have greatly enriched human life. The

discovery of antibiotics has made a significant difference in

the treatment of diseases and in enhancing longevity of life.

New frontiers have been explored. Formidable health

and economic problems have been surmounted. Global

barriers have been broken and nations have come much

closer to one another and have become interdependent.

Yet, in the midst of all these achievements, there are a

few dark spots. For example, mankind is yet to take

concrete steps to negate the severe health and socio

economic impact of tobacco. As we welcome the dawn of

the new millennium, the world faces a formidable public

health challenge posed by tobacco.

WHO International Conference on Global Tobacco Control Law

Inaugural Session

Already, 800 million of the estimated 1.2 billion

smokers in the world live in developing countries. In 25

years, 75% of the world's smokers will live in these

countries. They will account for seven million of the global

10 million tobacco-related deaths by the third decade of

this century.

Today, 80% of the global tobacco production comes

from developing countries. Four countries, including India,

account for two-thirds of the world's production.

Developing countries, in fact, are virtually sitting on a

time bomb I The question is : can we afford such a man

made calamity in the 21” century ?

The answer is an

obvious NO.

Excellencies, the South-East Asia Region contains one

fourth of the world's population, and carries an even larger

percentage of its disease burden and the poor. Yet, the

Region has the unenviable distinction of having the second

highest annual per capita growth in tobacco consumption

among the six WHO Regions.

The large populations and rapid economic growth in

some countries are an irresistible magnet for the tobacco

industry. Multinational companies and national tobacco

monopolies are expanding

Indonesia and Thailand.

their

business

in

India,

As a result of the powerful advertising and marketing

strategies of these companies, over one million children in

India and Thailand alone take to smoking every year. The

Region also reports not only one of the highest smoking

WHO International Conference on Global Tobacco Control Law - Inaugural Session

rates among women but also oral cancers caused by

tobacco. Cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive lung

diseases and lung cancers are already major killers. Every

year, tobacco kills an estimated 580,000 people in the

Region.

We must adopt legal instruments to control tobacco or

our children will accuse us of having wasted the

opportunity. This is one epidemic of several illnesses which

we can control and we must take action now.

For many decades, the tobacco industry has used the

argument that tobacco control will lead to unemployment

and revenue loss for governments. But this is not true. World

Bank reports clearly state that most countries will not face

any significant economic repercussions or job losses if

tobacco

consumption

is

reduced

or eliminated.

For

example, in Bangladesh, which is a net tobacco importer,

elimination of tobacco consumption will

increase

employment by over 18%. Also, a rise in tobacco taxes, in

fact, increases, rather than diminishes government revenue.

In

the

South-East

Asia

Region,

tobacco

disproportionately affects the poor and the most

vulnerable. Over 80% of the workforce in the tobacco

industry comprises women, the poor and children. It is they

who till the land, pluck the tobacco leaves, cure thousands

of metric tonnes of leaves in smoke-filled curing units, and

spend hours in bidi rolling and gutka packaging cottage

industries.

It is they who suffer from numerous occupational

hazards. Their vulnerability is accentuated by the very low

WHO International Conference on Global Tobacco Control Law - Inaugural Session

wages they earn from tobacco. Working in tobacco

production, keeps the poor in poverty.

In many countries of the Region, about 25-30% of a

poor man's income is spent on tobacco. The expenditure

on diagnosis and treatment, travel for treatment, and loss

of income due to absenteeism goes far beyond the means

of most families.

Poverty alleviation programmes are being eroded as

beneficiaries spend larger proportions of their income on

tobacco products than on food, shelter, education and

health. In fact, the government spends more on tobacco

than it receives as revenue.

In the final analysis, it is the tobacco industry which

grows richer, leaving the poor poorer.

Today, the link between TB and tobacco needs no

elaboration. Already, this region accounts for about 40%

of the world's reported tuberculosis cases.

The danger facing a majority of communities exposed

to the TB bacilli and now to smoking or chewing tobacco is

too serious to be ignored.

Excellencies, the time has come for us to respond to

the urgent call to disinvest tobacco in order to enhance the

future welfare of our nations. Today is the hour, tomorrow

will be too late.

The litigation against the tobacco industry in the USA

holds valuable lessons for all of us. The industry cannot be

allowed to continue to sell hazardous and addictive

WHO International Conference on Global Tobacco Control Law - Inaugural Session

products. Nor should it be permitted to continue to lure

millions of innocent children into tobacco use under the

garb of trade liberalization and the right to freedom of

speech. The tobacco industry knows the health hazards of

tobacco and skillfully markets death. With the power of this

information, we must ensure our children understand the

dangers they face.

We also need international laws and regulations to

curb this deception, particularly in developing countries.

Laws that will protect the most vulnerable and ensure that

what is not allowed in developed countries is not allowed

in developing countries either.

This Conference presents a unique and timely

opportunity for developing countries to shape the elements

of a Global Tobacco Control Law. A law that will not only

protect their economic interests but also save the lives of

millions who are, and will be, enslaved by tobacco.

The challenge is obviously daunting, but it is definitely

not unsurmountable. With focused commitment and the

determination of all governments, the world can become

tobacco-free.

Let us enter the new millennium with the determination

and vision to liberate society from the bondage of tobacco.

We owe this to posterity. Together, we can make a

difference. Together, we can make it happen.

Thank you.

WHO International Conference on

Global Tobacco Control Law: Towards a

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

7- 9 January 2000, New Delhi

World Health Organization

Government of India

Messages

President, Republic of India

Tobacco represents a paradox. While its use has, over the ages, received societal

acceptance, it is not disputed that tobacco whether smoked or chewed, is harmful to

human health. Similarly, the production of tobacco has major social and economic

implications for developing countries in terms of the employment of people on farms

and factories. At the same time, the profit margins from tobacco go to industry and

advertising rather than to small growers and workers. Tobacco control policy has

therefore, to address the negative effects of tobacco in a manner that is imaginative,

weaning people away from the use of tobacco, without hurting any vulnerable segments

of society.

I congratulate the WHO for initiating the development of the Framework Convention on

Tobacco Control. By hosting this conference jointly with the WHO, India has affirmed its

support to the need for global action for tobacco control.

I wish the deliberations all success.

K.R. Narayanan

President, Republic of India

Prime Minister, Government of India

I am happy to learn that the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the World Health

Organization are jointly hosting an international conference on "Global Tobacco Control:

Towards a WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control" in New Delhi.

The conference represents an emerging global consensus on the need for state

intervention to control the use of tobacco products. Governments all over the world

are beginning to adopt a pro-active role in curbing addiction to tobacco products as

it poses a serious threat to public health. These measures need to be adequately backed

by community participation in disseminating information about the harmful effects of

tobacco products.

It is a matter of concern that the consumption of tobacco products has been steadily

increasing in developing countries. Therefore, the developing countries need to evolve

a common approach on how best to tackle this problem.

The Conference on Global Tobacco Control will provide an opportunity to participants

to discuss this and other related issues as well as exchange information on measures

being taken by various Governments to check the use of tobacco products.

I wish the Conference all success.

A.B. Vajpayee

Prime Minister, Government of India

Chief Justice of India

I am happy to learn that the World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare are jointly organising an International Conference on "Tobacco & Law"

at Vigyan Bhavan, New Delhi from January 7-9, 2000.

Health hazards associated with use of tobacco both by the user as well as by the passive

smoker have been highlighted from time to time but precious little appears to have

been done to meet the challenge. India is a party to various resolutions adopted by

the World Health Organization, including the one adopted in 1986 which urged member

countries to formulate a comprehensive national tobacco control strategy. No significant

follow up action, except banning smoking in public places and public transport and

that too in certain cities and localities only and printing of the statutory warning on the

packets of cigarette and in the advertisements relating thereto, has been taken.

Considering that in India alone almost one million tobacco-related deaths take place

every year, the hosting of the International Conference is a timely step in the right

direction. The existing law apparently has not made much impact because of its poor

enforcement and other inadequacies. Causes need to be identified and remedial

steps taken.

The experts, scientists and other delegates taking part in this Conference would have

an opportunity to focus upon the harmful effects of tobacco consumption on public

health and generate community awareness about various harmful aspects of the use

of tobacco. If the Conference can formulate a framework for tobacco control, devise

some effective strategy and propose measures for dealing with the menace, it would

have served a very useful purpose.

I wish the Conference every success.

Dr Adarsh Sein Anand

Chief Justice of India

Minister of Finance, Government of India

General awareness about the detrimental effects of tobacco consumption has been

increasing over the years. Yet there has always been a somewhat hesitant approach in

launching any tangible anti-tobacco programmes in developing countries. This could

be attributed to apprehensions about the undesirable economic and social

consequences of any such measures. In a pre-dominantly agrarian economy like India's

such apprehensions have to be resolved before any meaningful programme can be

made in the direction of tobacco control. There will have to be consultations with

various interest groups before the dream for a tobacco-free society can be realized in

real life.

Any law must necessarily reflect the aspirations of society. If social evils could have

been curbed by legislations alone, this world would have been a veritable Eden.

Therefore, without sanction from society, no law can be effective. It is therefore, very

necessary for the eminent participants of this conference to gauge the mood of society

and appropriately mould the legislation. In this task, a very onerous responsibility has

been cast upon them. They have to carry the global society with them. If they do not

succeed, dur future generations will not forgive us for having missed at the very beginning

of the new millennium, the crucial opportunity while trying to launch a crusade against

tobacco use. I wish the Conference all success.

Yeshwant Sinha

Finance Minister, India

Minister of Law, Justice and Company affairs. Government of India

I am indeed thankful for your invitation to participate in the WHO International

Conference: Tobacco Control Law to be held in New Delhi in the first week of the new

millennium.

The deleterious effects of tobacco consumption on health of smokers, both active and

passive smokers, and on public health in general is well established. I understand that

for developing countries in particular, the Conference will provide a unique opportunity

to devise strategies and framework for international legal instruments necessary to

regulate and control the consumption of Tobacco. I am certain that with the wide

participation of delegates from 55 developing countries, the Conference shall generate

enormous community awareness of the menace posed by the evil habit.

In India, we have made compulsory the printing of a statutory warning on every packet/

package containing Tobacco. We are committed to generate a still wider awareness

of the harmful effects of tobacco especially amongst our young people.

I wish the Conference all success and on behalf of the Law Ministry, I assure you that

every possible effort shall be made to facilitate the widest possible collaboration between

the concerned parties (NGOs, Social Welfare/Health Ministries, etc.) in this crucial matter

of public health.

Ram Jethmalani

Minister of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, India

Minister of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India

There is an urgent need to stem the habit of tobacco consumption. It is now proved

that tobacco is a risk factor for about 25 diseases. Estimates suggest that in India, the

number of persons affected with tobacco related diseases is very high. Out of the

estimated three million tobacco related annual deaths in the world, about 0.8 million

deaths take place in our own country. All this calls for more concerted action to restrict

and eventually eliminate consumption of tobacco.

The government of India has taken a number of steps for discouraging smoking and

intake of products which are tobacco addictive:

it is mandatory to display a warning that smoking is injurious to health on all cartons/

packets of cigarettes.

advertisements relating to tobacco and tobacco related products are not permitted

on state sponsored electronic media.

iii)

smoking is also prohibited in public places like hospitals, dispensaries, education

institutions, conference rooms, the domestic air flights etc.

i)

ii)

There is a growing demand for enacting a comprehensive legislation for control of

smoking and tobacco consumption to reflect the positive commitment of the

Government of India on this subject. This international conference has therefore come

at the most opportune time for us. We look forward to helpful inputs not only for our own

legislation but also for laws having global relevance. Even a slight reduction in the

incidence of tobacco consumption, if brought about by State intervention, will transmit

the right signal to the community and lead to a positive impact on public health. I,

therefore, look forward to the pragmatic outcomes of this Conference, and wish its

mission all success.

[4 • I •

-----

N.T. Shanmugam

Minster of State (Independent Charge)

Health and Family Welfare

Government of India

ty)

Director-General, World Health Organization

At the dawn of the new Millennium, it is appropriate that I visit one of the most populous

countries to urge world leaders to act decisively this century against tobacco. I wish to

thank the host, the Government of India, for actively supporting WHO to hold this meeting.

This conference focuses on Global Tobacco Control Law and offers developing countries

the opportunity to establish their unique perspective on the creation of a viable Framework

Convention on Tobacco Control. The burden of disease resulting from tobacco consumption

is increasing steadily and at an alarming rate in developing countries. It is projected that

developing countries will contribute 70% of tobacco induced deaths if current smoking

patterns continue.

This conference is very timely and important for several reasons. First, developing countries

need to have their views articulated on the issue of global tobacco control. They need to

be fully involved in the Framework Convention's creation and its future implementation. The

Convention will enable developing countries to adopt a collective response to combat the

tobacco epidemic.

Secondly, this meeting will help create a multi-sectoral approach to tobacco control in

developing countries. The evidence of the increasing burden of tobacco-related deaths in

Africa, Latin America and Asia calls for a multifaceted global response. Tobacco is not only

bad for health but, it is also bad for the economy at large. A multi-sectoral approach to

tobacco control is needed if the Framework Convention shall be an effective tool for all

areas of governance which have a direct impact on people's lives and health in poorer

countries. Therefore, the development of the Framework Convention calls on the participation

of other Governmental Ministries in addition to the Health Ministries, such as finance, justice,

trade, agriculture and education.

The conference is also a point of departure for collecting the necessary technical and public

health expertise from developing countries to support WHO efforts for tobacco control. I

hope this conference builds consensus, strengthens the hands of parliaments and

governments participating in this process and gathers the political backing necessary to

control the global spread of tobacco.

Tobacco claims one victim every 8 seconds. Tobacco now kills four million people a year. In

about thirty years, that figure will rise to 10 million, more than the total deaths from malaria,

maternal and childhood illnesses and tuberculosis combined. Globally, between 82,000 and

99,000 young people, some as young as 12 years old, start smoking each day. In India

alone, about 630 000 people die annually from tobacco.

Future generations will recall and judge this conference as one where developing and

least developed countries made a major contribution to health through their efforts to control

the tobacco scourge and reduce deaths.

Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland

Director-General, World Health Organization

Regional Director, WHO South-East Asia Region

Every minute of the day, everyday, someone, somewhere in the world succumbs to a

ruthless killer: Tobacco. The global toll is 4 million lives every year. By the 2020s or early

2030s, based on current smoking trends, the figure could well rise to about 10 million.

Nearly 70% of these deaths would occur in developing countries. This would make

tobacco consumption the leading cause of disease burden in the world.

Keeping this grim scenario in mind, the World Health Assembly, in 1996, requested the

WHO Director-General to develop a Framework Convention for Tobacco Control. For

the next few years concerted efforts were made towards this end. In July 1998, the

Director-General launched the global Tobacco Free Initiative expressly aimed at