RF_NUT_5_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_NUT_5_SUDHA

A mother’s grief

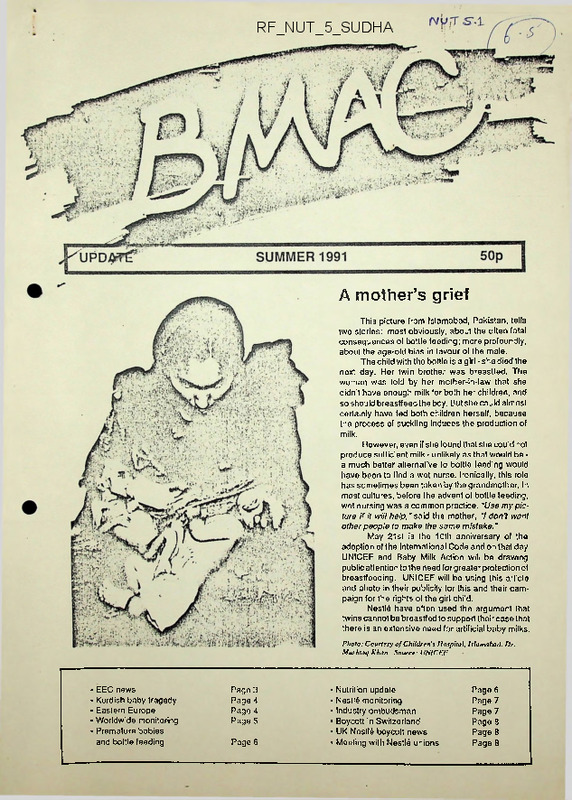

This picture from Islamabad, Pakistan, tells

two stories: most obviously, about the often fatal

consequences of bottle feeding; more profoundly,

about the age-old bias in favour of the male.

The child with the bottle is a girl - she died the

next day. Her twin brother was breastfed. The

woman was told by her mother-in-law that she

didn't have enough milk for both her children, and

so should breastfeed the boy. But she could almost

certainly have fed both children herself, because

the process of suckling induces the production of

milk.

However, even if she found that she could not

produce sufficient milk - unlikely as that would be a much better alternative to bottle feeding would

have been to find a wet nurse. Ironically, this role

has sometimes been taken by the grandmother. In

most cultures, before the advent of bottle feeding,

wet nursing was a common practice. "Use my pic

ture it it will help,"said the mother, "I don't want

other people to make the same mistake.'

May 21st is the 10th anniversary of the

adoption of the International Code and on that day

UNICEF and Baby Milk Action will be drawing

public attention to the need for greater protection of

breastfeeding. UNICEF will be using this article

and photo in their publicity for this and their cam

paign for the rights of the girl child.

Nestld have often used the argument that

twins cannot be breastfed to support their case that

there is an extensive need for artificial baby milks.

Photo: Courtesy of Children's Hospital, Islamabad. Dr.

Mushtnq Khan. Source: UNICF.F

• EEC news

• Kurdish baby tragedy

• Eastern Europe

• Worldwide monitoring

• Premature babies

and botlle feeding

Page 3

Page 4

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

• Nutrition update

• Nestl6 monitoring

• Industry ombudsman

• Boycott in Switzerland

• UK Nostl6 boycott news

• Meeting with Nestld unions

Page 6

Page 7

Page 7

Page 8

Page 8

Page 8

Baby Milk Action

This newsletter (2nd edition) Is produced by Baby Milk Action, the coordinators of the UK Noslld boycott. It is

written and edited by Gay Palmer, Andrew Radford, Patti Rundall, Stuart Reid and Lisa Woodburn. Baby Milk Action is

a member of the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN), a network of over 100 groups working for the pro

tection of infant health in over 60 countries. Baby Milk Action aims to halt the commercial promotion of bottle feeding and

to protect and promote good and appropriate infant nutrition.

We aim to produce a newsletter every 6 months. However, campaigning, lobbying and monitoring commitments

may make this impossible. Contributions and letters are welcomed but we cannot guarantee to use them as space is

limited. Please write if you have any information which may bo useful to us.

Baby Milk Action's development education work is funded mainly by the EEC, Save the Children, Oxfam, Christian

Aid, CAFOD, UNICEF and UK churches. For our campaigning work we rely on donations, membership subscriptions

and income from the sale of materials. If you find this newsletter interesting and would like to help us, please consider

joining or sending a donation. Baby Milk Action is a small organisation, Nestle is the largest food multinational in the world.

Baby Milk Action, 23 St. Andrew's Street, Cambridge CB2 3AX. Tel: Q223 464420. Tel/Fax: 464417

Area Contacts

Our network of area contacts has expanded to 47 activists

following a training day in April. Baby Milk Action intends to hold a

health workers training day in September and an area contacts

training day in Scotland in the Autumn. Anyone interested in becom

ing more active is welcome to attend. A list of area contacts is included

with this newsletter • and we are always looking for additions to it...

New materials

Wake up to the facts: a 6th display poster has been added to

the original series of five mentioned in the last Update. Colour photos

of breastfeeding mothers and babies can also be hired at a nominal

charge.

Baby Milk Action leaflets: A4 folded leaflets with information

on Baby Milk Action and our campaigns.

Breastfeeding a Global Priority, UNICEF (VHS video). 25

minutes. Available for hire: £5 from Baby Milk Action.

Competition

results

This is the

winning caption from

the competition in the

last BMAC Update.

The winner Is Mrs E.

Tent of Saffron

Walden. Runners up

prizes have been

sent to Rhoda Ui

Chonaire of Ireland

and Hermit Singh

Randhawa of New

castle.

Hmm, this one’s not tlcud yet.. better f>ive it another bottle.

BMAC UPDATE Sumnwr INI Pig« 2

Hospital booklet

withdrawn

Bradford Health Authority has been forced to

withdraw a booklet entitled A Guide to Maternity Services

after complaints about full-page adsfor Cow& Gate and

Farley's baby milks which appear on the inside covers.

The message conveyed doubly undermines the Gov

ernment's stated support for breastfeeding by a smaller

advertisement inside which urges readers to support

advertisers “by using their products and services.'

Oldham, North Tyneside, West Norfolk and Cam

bridge HAs have allowed ads to appear in similar book

lets - some of which contain no other information about

infant feeding. We understand that a firm in the Mid

lands arranges for these guides to be paid for by

advertising.

Why we need a law not a

voluntary Code

A health worker reports that companies continue

to dump free baby milk at The Queen Elizabeth II

Hospital in Welwyn Garden City .

Companies feel that as the UK Code is voluntary

they are free to ignore some of its provisions. They are

placing a wide interpretation on ‘professional evalu

ation and research' and are asking for cooperation from

paediatricians for 'research.' Since all the babies for

whom statistics of any kind are being collected are the

subject of research, the manufacturers are dumping

free supplies and at the same time asking health

workers to take part in joint research.

Baby Milk Action Area Contact for Hertfordshire,

Louise Lotz has volunteered to help with the monitoring

and reporting of Code violations in the UK. Louise has

been shocked at the volume of promotional literature

that she has found in hospitals, clinics and supermar

kets and says that it is clear that companies are delib

erately trying to sabotage breastfeeding.

Monitoring...

Tragedy of Kurdish babies

News reports of Kurdish babies dying during their desper

ate flight from Iraq imply that mothers are too malnourished to

breastfeed. For the refugees, who were mainly middle class and

well fed, the long walks into Iran and Turkey must have caused

great shock and stress. Nevertheless, breastfeeding rates in Iraq

are low (in some areas only 30% at 3 months) so the majority of

the babies were already bottle feeding before they left Iraq.

Lactation performance is unlikely to be affected in such a

short time and so those mothers who were breastfeeding and

whose milk diminished from the stress of the journey could

probably, with the right help and encouragement, have rees

tablished their supply. Baby Milk Action Director, Dr Tony Cos

tello, of the Institute of Child Health, London, visited Iraq for Save

the Children and confirmed this. “In my view a very significant

toumber of children, especially babies, died because they were

Ibottle fed. This is a wealthy, population who had been largely con

vinced that bottle feeding is better than breastfeeding. In the

response to the crisis, it was tragic that insufficient attention was

given to the promotion of oral rehydration and the possibility of

relactation.’ Janey Hampton, also with Save The Children,

visited hospitals in Iran where many of the Kurdish mothers were

giving birth. She was not surprised that so many mothers were

bottle feeding since they were given no encouragement to

breastfeed when they gave birth. It was standard practice for

babies to be separated from their mothers at birth for 6 hours.

Indeed if the babies were anything but "100% normal", ie, forceps

delivery, twins, low-birth weight, they went straight to special care

units (often for weeks) where mothers were forbidden to enter. All

babies in incubators were bottle fed. Of course, everything should

be done to ensure that milk reaches babies who genuinely need

it (indeed, the Code specifically allows companies to give in those

circumstances) but this tragic episode illustrates the dangers of

relying on imported products and inappropriate methods of feed

ing.

While the reports talked repeatedly about baby milk short

ages, Nestld claimed to have lost sales of about 60,000 tonnes

' of powdered milk to Iraq and Kuwait during the embargo and used

this as one of the reasons for their decline in profits for 1990.

Nestld claims that 17 kg of milk powder are neodod Io lood a baby

for 6 months. But if all babies in Iraq and Kuwait were exclusively

bottle fed for 6 months, only 13,804 tonnes would be needed.

Eastern Europe: baby

milk companies muscle in

Most baby milk distribution in Eastern Europe is con

trolled by governments, but the situation is changing with

the introduction of the 'free market'. Already, excellent

Eastern European milk banks are closing due to lack of

funding and an assumption that commercial baby milk will

replace donated breastmilk. Nestld, Milupa and others are

invading the new markets, with aggressive promotion that

undermines breastfeeding. Fortunately IBFAN groups are

being formed; although not yet properly funded, they have

the enthusiasm essential for any consumer campaign.

Nestle have bought the East German infant formula

Manasan and the price has doubled; they are also planning

a production unit in eastern Germany. Baby milk is pro

moted aggressively in Germany and mothers in the east

are already receiving quantities of gifts and samples.

In Hungary, Milupa are handing out information

booklets containing promotional messages and have or

ganised a paediatric conference. Nestle plan to set up pro

duction sites there.

Phillip Lunts, a Baby Milk Action Director, visited

Poland and found tins of Nestld’s Guigoz with baby pictures

on the label. The text was mainly in English with only the

preparation instructions in Polish.

In Czechoslovakia, where national baby milks are on

prescription only, Milupa products are marketed near the

German border. A Prague shop window had a promotional

display of Chicco bottles and teats. IBFAN also discovered

that South Africa had suggested donating breastmilk sub

stitutes here as aid. A Czech paediatrician told the aid

negotiators, "There’s no need, if we have a shortage of our

own, there is Milupa.”

In October 1990, The first WHO Conference on

Nutrition for Europe took place in Budapest and Baby Milk

Action's Gay Palmer and Dr. Clarke of the UK Department

of Health presented their views in the Infant Feeding

workshop. In April 1991, Gay Palmer ran the infant feeding

section at the Nutrition Policy Workshop in Prague, organ

ised by the London School of Hygiene and the Prague

Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology.

Ten years of the International Code - any progress?

Company promotion continues to lure mothers and health workers

away from breastfeeding, concludes a worldwide survey of baby

food marketing published by the International Baby Food Action

Network (IBFAN). Andrew Radford of Baby Milk Action analysed

monitoring information sent by researchers working in over 80

countries, comparing it with the requirements of the International

Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

Chart 1: The State of the Code by Company shows lip service to

the Code alongside aggressive marketing. The 10 years since the

Code’s adoption shows improved labelling and reduced direct

advertising. However, 10 companies fail to use local language

labels and 11 still use baby pictures. Five companies are

highlighted as the worst: Nestld, Wyeth, Milupa, Meiji, and Hipp.

Company marketing practices have evolved since 1981 and large

BMAC UPDATE Summw IWl P>0« <

budgets are spent on developing new promotion methods

which get round the Code's restrictions and undermine

breastfeeding. Follow-on milks, unheard of 10 years ago,

are now promoted by almost every company. Pre-term,

soya and hypo-allergenic formulas and baby milks which

purport to cure diarrhoea are promoted and marginalise

breastmilk.

Chart 2: Slate of the Code by Country, documents the

measures taken to implement the International Code by the

governments of 169 countries. Only 9 countries have

adopted the Code as law although 12 have a good voluntary

code. Twenty eight have parts of the Code as law but 66

have so far failed to take any action. The charts are available

from Baby Milk Action: £1.50 each or £2.50 for 2.

Changes in European laws

EC allows high

sugar levels

A loophole in the compositional

standards of the new EC Directive will

allow infant formulas and follow-up milks

Faced with mounting consumer pressure and publicity, the EC Commission

agreed on 15 March, the final day of consultation, to important changes to the Directive

on baby milks. Although the final version contains loopholes and omissions, it does

not contradict the WHO Code and will improve breastfeeding protection in Europe.

The final Directive will permit free supplies only to babies who have to be led on

infant formula. The previous wording would have allowed free milk to be given to all

babies who are bottle led. The UK can now keep retain its ban on free supplies to

maternities. Now wording permits countries to ban advertising if they wish. This

means that the UK, (who wanted a ban on advertising) havo no excuse not to ban the

baby milk ads currently flooding hospitals. Baby pictures on labels and froo samples

will be banned. The Commission refused to change the age range of follow-up milks

(they will be allowed from 4 months) despite the fact that most EC member states had

supported the 6 month age limit in 1987. The Directive does not cover other bottle fed

foods (sweetened drinks, special milks etc), exports or bottles and teats.

The Commission came under pressure from all sides: from governments - the

UK and Dutch Governments were strong in thbir support for the WHO Code; from

MEPs • who threatened to overturn the Directive if it did not satisfy their demands; from

over 1,000 health, consumer and development agencies; from the public - the Com

mission allegedly received over 1500 letters; and from Wl IO and UNICEF - UNICEF's

Executive Director, James Grant wrote to Jacques Delors, the President of the

Commission describing the unmodified Directive as a serious setback in our efforts

to promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first 4-6 months.

Patti Rundall of Baby Milk Action and Bas van der Heide, of the Dutch IBFAN

group, WEMOS, who organised the lobbying met with the Commission in February.

The Chair of the Standing Committee discussed possible changes so that at least

countries could honour their commitment to the Code.

Press attention mounted until the last day with three BBC programmes, French

radio, Danish TV, Reuters and numerous journalists pressuring the Commission to

explain why they were insisting on such a bad Directive. The Commission admitted

to Reuters that free supplies were necessary mainly for the survival of the market.

The Commission's advisory committee, the Scientific Committee on Food, is

not required disclose its industry interests. IBFAN has asked the Commission to

address this issue. Please write to your MP or MEP or to Minister for Health, the Rt

Hon Virginia Bottomley, at the Department of Health, 79 Whitehall, London, SW1A

2NS, to ask for the whole of the Code to be adopted as law in the UK

Weaning Directive

Following the baby milk Directive comes a draft Commission Directive on

weaning foods. This draft covers only labelling and composition and does not address

promotion. It allows weaning foods to be labelled as suitable from 3 months, WHO

states; ‘The provision of foods other than breastmilk before about four months of age

is unnecessary and may also be harmful. "Please send comments to: Alison Maydom,

Consumer Protection Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Ergon

House, 17 Smith Square, London SW1P 3JR. The first meeting is in June.

to contain 40-50% sugars - and 75% of

these sugars can be tooth-damaging

sucrose or glucose syrup. Product la

bels will not have to reveal sugar con

tent and can even claim - if glucose

syrup is used - that they are 'sucrose

free'. For more information on sugar,

contact Jack Winkler, Action and Infor

mation on Sugars, 28 St Paul St, Lon

don N1 7AB. 071 226 1672.

Milupa condemned on

sugar levels

Milupa have been found guilty by

a Frankfur( court of marketing a dan

gerous product with insufficient instruc

tions for use. The case was brought by

the parents of two children who suffer

from painful tooth decay alter being

bottle fed with Milupa infant teas. The

Federal Health Department had previ

ously issued warnings about this baby

bottle syndrome but Milupa only in

cluded a warning in small print on an

accompanying loallut. Infant teas and

drinks are high in sugar and, when they

are bottle fed, lead to serious tooth

decay. The Department of Health's

1989 COMA report on tooth decay

states that “for infants and young chil

dren simple sugars (eg sucrose, glu

cose or fructose) should not be added

to bottle feeds."

Another 27 similar cases are

awaiting judgment In Germany, each

claiming over US$27,000 in damages

from Milupa. Lawyers say that in Ger

many alone there are around 100,000

children sufferlngfrom baby bottle syn

drome. In German hospitals newborns

are routinely fed these sweetened teas

and baby milk promotion is widespread.

Small wonder that the breastfeeding

rate is as low as 3% at 3 months in

some areas. These drinks are now

aggressively marketed in the UK •

Boots, Robinsons and Cow & Gate pro

mote varieties in bottles designed to

carry a teat. A study in Camden shows

that 11% of bottle fed children suffer

from dental caries.

0MAC UPDATE Summer 1W1 P«9«

Boycott news ,

General Synod to debate

the boycott

/ Nestle overreact as boycott

is launched in Switzerland

The General Synod of the Church of England is to debate

a motion proposed by the Bishop of Leicester calling for

support for the Boycott - possibly in July.

Baby Milk Action meets Nescafe shop

stewards

On 3 May, Andrew Radford and Patti Rundall of Baby

Milk Action met senior shop stewards from the Nescafe factory

in Burton on Trent and representatives of the Transport and

General Workers Union (TGWU). The Nescafe workers had

been worried that the increasing success ol the boycott was a

threat to jobs. The meeting provided an opportunity for all to

express their concerns.

NestIG make no secret of the fact that "because of

rationalisation and rostructuring measures... it is feared that

jobs will be eliminated." According to the International Union

of Food Workers 1,597 jobs are to be lost due to restructuring

in France alone. If the boycott is successful, Nestld will bo

forced to change their practices before profits are reduced to

a level where job losses become necessary.

On behalf of those present. Bob Harrison, TGWU

National Secretary, expressed concern (or our campaign to

protect mothers and children from exploitation. Ho said ho

would report back to his members who would decide on further

action;

Midwives endorse boycott

In December 1990, the Royal College of Midwives called

upon its 36,000 mombnrs to boycott Noscalo and other Ner.tlrt

products and condemned "Nestld's dangerous marketingprac

tice of providing free baby milk formula to maternity wards in

developing countries". (See Boycott endorsers list.)

Stars pull out

Richard Briers has contacted a Baby Milk Action sup

porter to say that he will no longer advertise Nescafe. Felicity

Kendall is already an endorser. Nothing has been heard from

Paul Eddington. Sarah Greene has also stopped advertising

Nescafe.

Nestle have filed a complaint against the three national

Swiss TV stations for biased reporting in screening Yorkshire

TV's Vicious Circles and Australian TV's Formula Fix in Feb

ruary. The programmes, which were screened the day before

the Swiss boycott was launched, document the consequences

of marketing of baby milk by Nestld and other companies in

Pakistan and the Philippines. The films wore shown after

Neslld had made repeated attempts to intimidate the stations

into withdrawing them. Swiss broadcasting legislation requires

all programmes to be balanced and, in their complaint to the In

dependent Media Licensing Commission ol Switzerland, Neslld

claim that thn 1V companies have violated this rule.

Annolies Allain of the International Organisation of

Consumer Unions made the point, "Here was the largest and

holiest of Swiss companies being challenged on home turf."

For a country with a unique 'protection of personality' law

which prohibits criticism of a Swiss company the films amounted

to heresy. Two days before the Swiss programmes were due

to be screened, Neslld hold a press briefing with selected

'friondly'journalists. Thoy showed clips from both films without

permission, in breach of copyright, and refused to allow

anyone from Swiss TV's documentary department to attend.

The documentaries, which have been shown without com

plaint in several other countries, wore followed by a debate

between Neslld spokesperson Franrjois Porroud and Dr. Juan

Perez from the Philippines. Nestle's defence was superficial.

They maintained that not only did their formula save babies'

lives but that breastfeeding has no relationship to infant mor

tality rates.

Nestld's reaction backfired and stimulated the interest

ol the Swiss procs which reacted sceptically to the company's

protestations. Dr Jim Tulloch of tho World Health Organisation

wrote to Swiss Television to challenge Nestle's claims on the

quality ol the programme saying, “To infer....that breastfeed

ing is not important in reducing the risk of mortality in infancy

is absolutely incorrect from the scientific point of view. "The

Christian Medical Commission of the World Councilol Churches

wrote in support of tho programmes.

Nestle shareholders wrote to Nestld President, Helmut

Maucher, expressing concern at the company's response to

the programmes: "Wo thought this typo of reaction, ofplaying

down the facts and ofprofessing a perfectly clean conscience

had been relegated to the museum of tho sevonties, at the

famous Born court case..." In 1974, a Bern Third World group

Actionsgruppe Dritte Welt translated

War on Want's report The Baby

Killers asNestle Kills Babies.

Nestld sued (or libel.

This case also

backfired and

resulted

in wide

spread

publicity

for the

issue.

A carloon from a Swiss newspaper making novel

use of Nesiltf’s birds and nest logo.

rvuT

THE DANGER OF UNDER FEEDING

Kwashiorkor and marasmus are two diseases caused by

insufficient intake of food. This leads to deficiency of

calories (energy) and protein (body building material).

VICTIMS

Kwashiorkor and marasmus occur most commonly in children

between 1—5 years of age. Breast milk is sufficient for

children only upto the age of 4 months. Supplementation

with cereals, pulses, milk and eggs after the age of 4 months

is essential. If this is delayed or not done,-children do

not grow properly and kwashiorkor and marasmus develop.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMSs

■

OEDEMA: Children with kwashiorkor first show swelling of

the legs. Later, the face and the whole body may

also, become swollen.

C

o'

<$■

£

SkIN CHANGES:

The skin becomes rough and sore.

HAIR CHANGES:

-------------- •------- ’—

"

The hair may become scanty and also change colour

from black to various shades of brown. The child

also becomes irritable and disinterested in his

surroundings.

v

Children with marasmus become very thin and feeble due

to wasting of muscles. However, there is no oedema.

TREATMENT: ’

o

The child should be made to eat more food at frequent

intervals. Severe cases with loss of appetite should Le

treated at the hospital. Milder cases can be treated at home.

The diet must contain protein and energy rich foods. A

Combination of cereals, millets, pulses and oilseeds will

provide the necessary nutrients. If possible, milk, eggs

or flesh foods should also be given.

It is important to treat infections and diarrhoea

promptly.

The National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad has

formulated an energy-protein rich mixture to treat protein

calorie malnutrition at the home level. It consists of

wheat, roasted Bengal gram dhal, groundnuts and jaggery.

hese ingredients can be suitably changed depending upon

local availability. The comoosition of the mixture is

given belows

•?’

- 2 -

Whole wheat (roasted)

s

40 grams

Bengal gram (roasted)

8

16 grams

Groundnut

*

10 grams

s

20 grams

(roasted)

Oaggery

86

TOTAL

Calories

. : • 330

Protein

:

11.3 grams.

Many children with protein calorie malnutrition have been

treated with this food, mixture.A-picture of one - of these

children is shown below, 'he child showed improvement after

a few weeks and was completely cured within 3 months.

rvuT b-

-,tH CELL

-loor)St- Marks Road

*...

,,,

INFANT

'■. |

.560 001

FEEDINGS

Breast milk is a nutritious food and meets, the baby's

requirements fully till the 4th month of life.. Later'; breast

milk alone is net enough to meet the nutritional needs of the

growing child. This, calls for additional food supplements.

If additional foods are not given, the baby does not grow

properly and can show stunted growth.

DEINING

v

The gradual switching over of the child from breast milk

one to other foods is called 'weaning'.

'Fast rural .Indian mother do not give supplementary foods

because of the fear that infants will not be able to digest

solid or even semi—solid foods. This is Unfortunately a wrong

belief. The right type of foods- cooked in the right way and

introduced gradually are easily digested and will greatly benefit

the child.

The first foods added to the child's diet, after 4 months can

be in the liquid form. Buffaloe's or cow's .milk, mashed

vegetables like potatoes, tender beans, carrots and green leafy

vegetables can be safely given. Many mother add too much water

to milk.thus making it less nutritious. This practice should

be discouraged.

Introducing new foods to infants is not always very easy as

some infants may not accept them readily, but the mother should

continue to coax the child till he accepts it.

At the age of 5-6 months cereals and millets can be

introduced in the form of porridges. Small amounts of pulses

should be added to the preparation to make it more nutritious.

The belief that pulses are gas producing and cause distension

on the stomach should not exclude the use of pulses in infant

feeding. Infants tolerate a fairly good amount of pulses. Green

leafy vegetables should also be added, since they provide many

nutrients like vitamins. A and C, Iron and Calcium.

These nutrients are essential for good vision, blood

formation and healthy bones. A preparation using cereal,

pulses and greens is given below?

KICHEDI

Rice

- 3^- table spoons (50 Grams)

Greengram dhal (roasted) - 2

table spoons

(25 grams)

Leafy vegetables

(Palak or Amaranth)

bundle

(15 grams)

Salt

— 1

As required

Cort

2 -

METHOD

Rice and dhal are cleaned, washed and cooked together.

Palak is cooked and strained through a clean cloth. The

vegetable juice is adr'ed to the cooked rice-dhal mixture.

Salt

is added and mixed.

Soft ripe fruits should be mashed and given to the baby.

A ripe bababa is relished by all babies. Orange and sweet lime

juices are good sources of vitamin C. These, however, are more

expensive than are green leafy vegetables.

It should be remembered that clean vessels and boiled

and cooked water should be used while preparing any food supplement

Hands should be cleaned well before preparing the food.

Eggs and flesh foods can be fed to the infant aound the

first year of life whenever they are available and can be afforded

by the parents. Initially the egg should be given in a soft

boiled form.

If the mother is busy with other work and cannot prepare

fresh supplements every day, she can prepare ready mixed by roasting

cereals and millets (like wheat, ragi and bajra) and pulses (like

Bengalgram and .greengram) and powdering them separately. These

powders can be mixed and stored in clean tins for a few months.

Small amounts of'these powders can be prepared as porridges and

fed to babies.

An example is given below..

R A G I N A

Ragi

-4 tablespoons (60 gms)

Bengalgram dhal(roasted)- 4 teaspoons (

Sugar

20 gms)

- 3-Jr tablespoons (50 gms)

flETHOD

Powder all the ingredients and cook in sufficient water.

Addition of milk makes the porridge more nutritious.

The amounts indicated for each recipe are meant to be

given per day per child. They should be distributed in the child's

diet in equal amounts during the. whole day. Instead of ragi or

bajra, wheat can be used. Similarly, any type of pulse can be used

insted of Bengalgram dhal.

Such.supplements started at the proper time will go a

long way in keeping the infant healthy and assuring proper growth.

3 -

RECIPES THAT NEED TO BE COOKED

GRAM

WHEAT

PORRIDGE

oqj

INGREDIENTS?

Roasted wheat flour

; 40 grams ( 2% tablespoons)

Powdered, roasted Bengal . 25 gramg (

gram

Powdered, roasted

groundnut

Spinach ( or any other

leafy vegetable)

tablespoons)

10 grams ( 12 tea spoons )

. 3Q gj?amg (

bundlg

METHOD;

Roast groundnut, wheat and Bengalgram and powder them.

Mix the wheat, Bengalgram and groundnut powders and prepare a Watt er

by addition of jaggery dissolved in a suitable amount of water and

made into a thin syrup.

Boil spinach in water till soft.

Mash and strain through a

clean cloth.

Add the vegetable juice to the batter and cook for a few

minutes with continuous stirring still semi-solid.

COMMERCIAL RECIPES

GROUNDNUT

BISCUITS

INGREDIENTS;

Groundnut (roasted)

s 25 grams (

Wheat flour(roasted)

S 25 grams ( 1% tablespoons)

Sugar

s 20 grams ( 4 tea spoons

Baking powder

; a pinch

Salt

; to taste

tablespoons)

)

METHOD

Powder the main ingredients and mix them. Add baking powder and

salt and mix thoroughly. Make a stiff dough by kneading the mixture.

Role like chapatis.

Cut out any shape desired with tin-lids or any sharp instruments.

Place the biscuits.on metal trays and bake them well on heated sand in a

dekchi. (The dekchi should be kept covered with a lid and pieces of live

charcoal kept on the lid to ensure uniform all-round heating).

Remove the,biscuits when they are goldenbrown

this usually takes about 20 minutes.

The quantities indicated are for use as a sup

plement per child per day. Similar biscuits can be prepared

using Bengalgram, gingelly seeds, cowgram and horsegram.

: 51 ■

NUTRITION

Nutrition is the study of foods and their actions or effects on the

body. Good nutirtion neans that the body is getting the required food

and is able to make use of it. Nutrients are substances with special

functions which are found in food and which are necessary for growth and

development of the body, repair of the body tissues, and protection of

the body against disease. They are of six types, viz., proteins,

carbohydrates, fats vitamins, minerals and water.

People generally eat or drink when they arb hungry or thirsty end,

on auspicious occasions, , they may eat or drink special foods, the foods

that people cat every day are usually not selected on the basis of their

nutritive value, but because of fe.mily habit, religion, or social custom.

It has been found that many such dietary practices, especially those

that are related to feeding infante, young children and pregnant women

arc not based on body requirements.

SOME TRADITIONAL F PCD HABITS AND' CUSTOIS ARE HARFUL TO HEALTH.

Because of e ating an unbalanced diet, many young children in India

are frequently ill due to infections, are retarded in their physical

growth, and their mental development is nega.tively affected. Unless

good nutritional guidance is given, accepted and practised by their

parents, such children will become adults who have, chronic ill health

and are unable to make their full contributicn as productive members

of the cor-TEiunity.

In addition, infants may be born weak and malnourished because their

mothers had poor diets during pregnancy. Because many women do not eat the

amount and kind of food that their bodies require during pregnancy and

afterwards, they become weak, have little- energy to care for their babies

and are unable to produce breast milk in the amounts needed by growing

infants.

NOT EATING CERTAIN FOODS EVERY DAY CAN CAUSE:

i. WEAK INFANTS CF LOW BIRTH WEIGHT.

ii. INSUFFICIENT PRODUCTION OF BREAST MILK.

iii.

RETARDED PHYSICAL AND MENTAL GROWTH .

iv. 'ILLNESS AND’ D’EMJFES'mTlXLlY^MO'NG INFATS AND WiS’CHO’PL’ CHILDREN. ’

11.1

PRINCIPLES OF NUTRITION

In order to be a.ble to assist individuals and families to learn

about and be able to practise good nutrition, you must know the principles

of nutrition.

Food is necessary for keeping the cells and tissues of the body

alive and for maintaining normal body functions.

2.

An adequate daily fluid intake is necessary for maintaining

the fluid balanced diet includes.

3.

A balanced diet includes:

1.

i. a sufficient number of calories;

ii.

adequate amounts of proteins, fats and carbohydrates;

•iid. adequate amounts of vitamins}

iv.

adequate amounts of minerals.

.................. .’Contd/52-

FROTEI1S _

Approx.

Vegetable Sources

cost

Horse gram

Rs .3 per

Kg.

March to October

XXX

Bengal gram

Rs .2/2 5 per

Kg.

Throughout year

■XX

Moong dal

Rs .2/25 per

Kg.

Throughout year

XX

Rs.1.29 per

-Kg.................

Throughout year

X ■

Buffalo Milk

Rs .2/- per

Kg.

Throughout year

XX

Eggs

Rs. 4/- to 5/“

per dozen

Throughout year

X

Fish

Rs.&/- to

Rs .12/- per

Kg.

-

January to April

September to December

XX

Wheat

Seasonal availability

Rating

Animal Sources

Annexure 11.1 contains a list of protein food sources available

in India. Refer to this list of prepare your own list of protein sources

available in your area.

Similar kinds of feed source lists can also be made for other

nutrients such as vitamin A, iron, or calcium which are also often

deficient in the diets of infants and young children (see annexures

11.2, 11.3 and 11.4).

11.3.1

JROTEIN EF BODY-BUILDING FOODS

Foods that contain proteins are needs by the body Hni ly for

repairing and replacing cells. Adequate amounts of this nutrient are

especially.important in the diets of pregnant and nursing women, infants

and young children because they have extra needs in addition to ncrmal

requirements, Pregnant women need extra protein foe ds to tafte care of the

_needs of the g-owing foetus. A nursing mother needs more body-building

foods to replace what she gives to her beby through breast feeding.

Infants and young children are growing at a very rapid rate and require

proteins for healthy growth and developnent.

11.3.2

CARBOWB/JES OR ENERGY-GIVING FOODS

In order to run, play or work, we need foods that give us energy

Carbohydrates in certain foods provide the body with energy. The

amount required by a person depends on the kind of activity he carries

out and the- time for which it is done. A man who is breaking stones all

day will need more energy-giving foods than a man who sits in his shop.

Children, especially pre-schocl children, are often not fed frequently

enough during the day so that they do not receive an adequate amount

of carbohydrates. When this happens, children become less active and

tire easily.

...................Contd/52-

: 52 :

Foods rich in carbohydrates include the following:

i.

Sugar, jaggery and honey

*

ii.

Cereals such as wheat, rice, millet, suji, maize.

iii-.-¥eg®taLbos such as potato, sweet potato, tapioca, yams

*

iv.

Fruit suchaas bananas, jackfruit, chikku, mango.

11.3.3. FATS CT. CONGENrRATED-ENETcGY FOODS

Foods that contain fats are needed'by>the body because they

supply concentrated energy, prevent dry, scaly- skin, help in the absorption

of vitamin D, and improve the flavour of ford

*

Because they, are a. concen

trated -source of energy, fats 'Supply twice as much energy as the same amount

of proteins or carbohydrates

*

This means that smaller amounts of fats are

needed in the daily diet to meet the body requirements •

- •

Foods rich in&ts include the following:

Vegetable sources:

.Cooking oils such as cocoanut, mustard, sesame (til) or

i.

groundnut oil

Animal sources:

i.

ii.

iii.

11.3.4

Butter and ghee

Milk, curds and cheese

Fish and fatty meat

VTTAI-ilNS CT. EROTECTIVE FOODS

Vitamins are substances which are found in small quantities in

several kinds of food. They are needed by the body for normal growth and :

maintenance of cells.

The body requires vitamins in small amounts. Since

the body cannot produce these substances, food sources are very important.

There are several kinds of vitamins. Seme are needed for good

vision and healthy eyes (Vitamin A)., others for blood formation (Vitamin B),

others are needed in the diet for strong teeth and bones (Vitamin- D), and

others for increasing resistance to infections and early healing of wounds

(Vitamin C).

1.

Vitamin A: In order to prevent nutritional blindness in youngg

children due to vitamin A deficiency in the diet) people must be informed

about the. kinds of foods that contain this important substance'and must be

encouraged to include it in their daily diet. In order to prevent night

blindness and dryness- of the eyes all children from one to five years

are being given vitamin A solutiin twice a, year. Foos rich in vitamin A

include the following:

Vegetable sources:

i.

Green leafy vegetables and yellow fruit like mango and papaya

and vegetables like yellow pumpkins and carrots.5

Animal Sources :

i.

Eggs and liver

-ii. Milk and curds

•

TEAMING FAMILIES- HOW TO -HlEVENT- -NIGHT BLUENESS IN YOUNG CHTTJlHENqs

A VERY IMPORTANT HEALTH EWCjaiOjO^

FOR AIL HEALTH WORKERS.

.

2.- Vitamin B: Vitamin B is a complex vitamin consisting of

several components which have various social functions.

: 52 :

4- Different types of fo-'d provide different kinds and

quantities of nutrients.

5.

The ago, activity, state of health and rate of growth

decide the amount and kinds of nutrients that are required

by the body for healthy growth and for the maintenane of

good health.

11.2

FUNCTIONS AND VAHJE-S OF NUTRIENTS IN FOOD

A~I~1 foods contain nutrients in varying amounts. Some foods

are made up of only one type of nutrient whereas others may include more

than one nutrient, e.g., cooking ail consists entirely of fat, while rice

consists mostly of carbohydrates but also contains some protein. Because

of this characteristic, foods can be classified according to the amount

of the various nutrients that they contain. It is very useful to know

which foods contain a large amount of a given nutrient so that these can be

•selected to meet the requirements of the body.

RE1EMBER THAT -A GOOD DIET IS A IDfflD DIET CONSISTING OF- DIFFERENT KINDS

OF FO(DS WHICH COl-iTAIN THE NUTRT EICTS NECESSARY FOR GOOD HEALTH.________

Each of the six nutrients that are found in food has its own

special functions to perform in the body. Those functions ’are as follows:

Proteins are necessary for growth. They help in repairing

worn-out body colls and in the formation of blood and

antibodies which are needed for building up resistance to

infection.

ii. Fats and carbohydrates provide the body with energy or' fuel

to carry out its various daily activities..

iii. Vitamins and minerals are necessary for the development

of tire blocd cells, help to maintain good vision and strong

teeth and bones, and help to promote normal growth.

iv.

Water comprises more than half the weight of the body and

is essenti: 1 for the proper functioning of body cells and

for maintaining the fluid balance of the body.

i.

11.3

FOOD SOURCES OF NUTRIENTS

When a food contains a very high amount' of a given nutrient^

it is called a feed source, e.g., pulses and dais and very good food

sources for protein, while potatoes and bananas are good food sources

for carbohydrates, but are a poor source of protein.

Protein is the nutrient that is the most important for infant

and child nutrition, hut it is the one that is most often missing in their

diet. It is, therefore, necessary to have information about protein

sources so that this can be conveyed at every opportunity to parents

and others who care for children. Because the different geographical

areas in the country produce varied kinds of vegetables which contain these

nutrients and the dishes that are prepared differ according to locality,

it is not possible to list all of them here. More accurate and realistic

information which is based on local conditions can he ■ compel'.ed by you with

the assistance of the Health Worker (Female) by de ^loping a list of

protein food sources for the villages within the subcentre. A sample

fora is given below

, „ k.. .

Contd/53-

: 53 :

These include the following:

They assist in the breakdown-and absorption of food.

They are necessary for keeping the skin and mucous members

healthy.

iii.

They are necessary for the proper development and function

ing of the nervous system.

iv.

They arc necessary for the formation of the blood cells.

i.

ii.

Foods rich in vitamin B complex include the following:

Vegetable sources:

• 'i. Parboiled rice and unpolished rice

ii.

Cereals and millet

iii.

Groundnuts

iv.

Ibises

v.

Legumes

Animal sources:

i.

Mik and milk products

ii- Eggs

iii.

Meat, liver and fish.

3. Vitamin C; This vitamin is necessary to keep the body tissues

intact arid to help in repair of the tissues. It also helps to protect the

body against infection.

Vitamin 0 is very easily destroyed and hence foods containing

this vitamin should not be exposed to air and heat.

Foods rich in vitamin C include the following:

i.

ii.

Citrus fruits such as oranges and lemons.

Guava, tomato and'amla.

4«- Vitamin D: Vitamin D is necessary for the absorption and

■utilization of calcium and phosphorus and hence lack of this vitamin causes

unhealthy teeth and skeletal deformities such as are seen in rickets.

Sources of vitamin D are as follows:

i.

ii.

iii.

Exposure to sunlight is the cheapest way to obtain this

vitamin.

Fish liver oils have a very high content of vitamin D.

Butter, ghee, groundnut oil §.nd eggs also_ contain vitamin D.

DE1®FBER THAT EXPOSURE TO SUNLIGHT ALONE IS PICT ENOUGHT IF TIE

DIET IS DEFICIENT IN FAT ♦

11.3.5

■ ■

MINERALS CTl HIOTECTIVE FOODS

Minerals are needed by the body for the formation of blood. The

development of strong .teeth and bones, and for regulating certain bedy

processes such as bleed clotting. .There are a number of minerals that

are required in minute quantities by the body. However, calcium and

iren are two of the important minerals which are needed by everyone,

especially by pregnant and nursing-women and children who are growing.

Feeds rich in calcium include the following:

Vegetable ‘sources:

i.

ii.

Lagi

. .

Green leafy vegetables.

: 55 :

Animal Sources:

i.

1 Hlk, cheese •

Focds rich in iron include the following:

Vegetable sources:

ii Bajra and ragi

ii.

Green leafy vegetables.

Animal sources:

i.

hod neat, lever and eggs.

Iodine • is another mineral, which is essential fcr normal growth

and development including the rate at which food is used by tie body.

The deficiency cf this mineral in the d aily diet is the cause of goitre •

Focds rich in iodine include the ■ fallowing:

i.

ii.

Fish of all types

Vegetables w ich are grown in areas close to the sea.

Salt which is fortified with iodine is used in are.as whore goitre

is prevalent.

11.3.6

WATER 01 FEU IDS

An adequate daily fluid intake in important for healthy functioning

of the body. Abnormal losses from vomiting, diarrhoea and high fevers can

cause dehydration (drying up of body fluids), which is a serious condition,

especially among infants and young children. Fluids in the fem of tri Ik

juices, other beverages and fruits and vegetables which are pulpy can be

used to supply the daily needs of the body.

TO PREVENT DEATH FROM DEHYDRATION CAUSED BY EXCESSIVE FLUID LOSS?-PROMPT FLUID REPLACES ENT IS NECESSARY ESTECIA11Y IN INFANTS /.ND

YOUNG CHUDEEN.

11 .4

■ A BALANCED DIET

Nutrition experts: have been able-to find out what combination

cf feeds is needed in the daily diet for healthy growth arid development.

However, this information has not yet reached many who 'live in the

villages so that they continue to eat only these feeds that have been

eaten'by their families for generations and as a result often suffer

■from various kinds of malnutrition. Often they are unaware that pregnant

women, mothers who are nursing, their babies j-. and rapidly growing young

children need more cf- certain foods to prevent their becoming ill -iv»ri .ghed.

A BALANCED DIET IS ONE WHICH IS MADE UP OF FOODS THAT CONTAIN ALL THE~

NECESSARY- -NUTEIENrS IN THE REQUIRED AMOUNTS AND PROPORTIONS TO MATNTA-T-N

HEALTH (SEE FIG. 1* .1).________________________________________

*

A balanced diet is necessary for good health. It is especially

important that proghant and nursing women,, infants and young children have

a balanced diet because these groups are most likely to develop malnutri

tion.

• ................................ Contd/56-

; 56 :

People need to know how a balanced diet will improve their health,

what fo> ds should be included, how much it will cost, where to obtain

the required foods and even how to prepare feed properly so that nutrients

are not discarded or lost due to improper cooking.

Since you will be the only health worker making regular house-tohouse visits in the twilight area, you should know about balanced diets

for pregnant and nursing women, and children, and proper feeding methods

frf infants.

DAILY BALANCED DIET FOP A PREGNANT OR NURSING WOiO

11.4.1

Select one or more fo- ds from each of these five groups:

a

.

....

f:-'ch

road, Rice. Vfcc-.t. Ebtat- , Sugar,

: 5? :

Group B: Protein foods such as Meat, Fish, Eggs, Milk, Groundnut, Dal,

Beans •

Group C: Fruits such as Orange, Banana, Ninbu(Line), Papaya, Mango

Group D: Vegetables- such as Feas, Capsicum, C: rrots, Bhindi (ladies’

fingers), Drinial, Tomato, Korela (bitter gourd), Cauliflower,

Palak (spinach), and Methi (fenugreek)

Group E: Fatty fo< ds such as Ghee, Oil, Butter

Fig: 11.1: A balanced diet

ii. Pulses, e.g., beans or dal

iii. Cereals e.g., rice or wheat

iv. Green leafy vegetables

v. Eggs

.

,

vi.

Fruit (seasonal)

twice

3 times

at least once

One every day or every

other day .

1 portion daily

Nursing mothers need more fluids including an extra' glass of milk

each day and extra servings of yellow and green leafy vegetables and;

cereals.

If the pregnant or nursing woman is vegetarian and does not eat eggs,

or cannot afford to get milk, she should be encouraged.:

to eat a handful of groundnuts each day;

to increase the pulses to 3 tines a day.

i.

ii.

Anaemia is commonly found in pregnancy and causes the woman to feel

weak and become easily tired..This can usually be prevented by including

a serving of a green leafy vegetable in the daily diet, and by taking the

iron and folic acid tablets which are distributed at the subcentre or on

the home visits by the health worker,.

In sone communities women eat less during pregnancy becuase they

believe that they will then • have a smiler baby and an easier delivery.

People need to knew that this is a harmful practice which can lead to mal

nutrition in the mother and low birth weight <bf the infant who is al an

malnourished.

REMEMBER THAT A SPALL BABY AT SUITE HAS LESS CHANCE OF SURVIVAL AMD IS

ME T.TKTCT.V TO CRT SICK BECAUSE CF LOW RESISTANCE TO INFECTION.

11

2

*

4

BALANCED DIET FOR. INFANTS (ZERO TO 12 MONTHS)

The major points to remember about the diet for and feeding of

infants are as follows:

1.

Breast milk is the best food for infants up to the age of .six

months because:

.

;

< ..

i.

ii.

iii.

it is-clean arid safe;

....

it contains all the necessary nutrients

no cost is involved.

•> ■

’’

..

After four months, all infants need to be given solid, food

since breast mi,1k does not supply all the nutrients that a rapidly

growing baby requires.

3- During weaning the ’first’ foods should be semisolid in consistency

e.g., mashed rice, millet, banana or potatoes. Gradually solid

foods from vegetable and animal sources containing protein must

be added so that the infant receives a balanced diet.

2.

: 58 :

4« Remove the infant’s portion of food before spices.are added

for the rest of the family otherwise the baby will develop «'

diarrhoea.

.

5 • Give the baby a spoonful of food at first and gradually inc: ease

the amount given over a period of weeks.

$*• Tho addition of foods other than milk to the infant’s diet

should be done gradually over a period of tine rather than

■ all at once.

7.

Glean hands and utensils and fresh foed are necessary for

preventing infections. Fbcd must be kept covered so that flies

do not sit on it. Water she Id be obtained from a safe source

of supply or boiled if possible. Never feed an infant with left

over foods because they are very likely to be spoiled and will

cause illness.

. '

.

8.

If the mother does jot produce enough breast milk, do not

suggest the use of a bottle and nipple; use of a. cyp and

spoon is safer since they are easier to keep clean.

9.

Breast feeding should be continued throughout the first year

so that the infant continues to receive valuable protein from

•

■

this source._____

'________

_

_____ ■ ____66

REMEMBER THAT THE MAJOR CAUSES OF BKNUTlfi liON IN INFANTS AND YOUNG

CHILDREN ARE:

i.

DELAY IN ADDING SOLID FOODS TO THEIR DIET .

ii . NOT FEEDING THEM FREQUENTLY ENOUGH .

iii.

THE LACK OF .CQDY-BUILDING EROTEIN FOODS .

iv.

INSUFFICIENT FOODS' CONTAINING THAI-UN A .

11.4.3

BALANCED DIET FOR THE JREASCHOOL CHILD (ONE TO FITE YEARS)

Children between the ages of one and five yoarp are often neglected

and underfed by their mothers. This happens because mothers do not know

that these children need proportionately more food for -uheir size than is

needed by adults. Becuae they are growing at a fast rate and the growth

is continuous, they need extra amounts of body-building protein food and:

energy-giving foods.

In many poor families, young children are breast-fed until they

are two or three years old and are not given any other foods eaten by the

rest of the family. This practice results in a high incidence of kwashi

orkor and marasmus, the former of which is caused by a deficiency of protein

and calories in the diet, while the latter is due to deficiency of calories.

AFTER FOUR MONTH

*

GF AG?, A DIET CONSISTING CF ONLY BREAST MILK IS

INADEQUATE ..

■ ~

A daily diet for children one -fo five years should include the

following:

1. Milk

2. Cooked cereal - pulse

mixture (khichiri, dalia,

idli or groundnuts)

3. Green leafy vegetables

(Ralak, chawli) and yellow

vegetable or fruit (carrot

pumpkin, papaya, mango)

4. Cooked cereal or millet

(rice, wheat, ragi)

-

1 tumbler

8 to 12 level spoons

-

4 to 8 level spoons

4 to 16 level spoons or

1 to 2 chappatis

: 59.:

5« Egg

or dal

or fish/noat

6.

Fresh fruit

• (banana, guava or

Tomato)

-

-

One

4 to 8 level spoons

4 to 8 level spoons.. , «

one portion

The feeds for the child, under two- years should be snail in amount

and should be given at shorter intervals than for the rest of the family.

The following foods should bo avoided in the diet of young children:

i.

Highly spiced dishes and curries.

ii.

Foods made with largo amounts of sugar.

iii.

Very greasy foods.

iv.

Poorly cleaned, insufficiently cooked, or improperly mashed foods.

Dietary instructions are easier to follow for most individuals when

they understand the amounts to be eaten in terms of commonly used measures

(see fig. 11.2). When utensils are not available in -the home, you will

have to give instructions regarding the quantity to be consumed in terms

of a 'a handful of dal’, or' 'one banana1, etc.

Fig. 11.2: Common household measures

Mc|

°£

Child can eat at one meal depends on

has health, body size and physical activity.

: 60 :

In the preparation and serving of food for children, it is

necessary to follow certain procedures in order to:

i.

ensure that the food is safe and clean;

' ii. preservo the nutrients in food;

iii.

nake the food more easily digestible.

These-procedu’ es are as follows:

1. Before preparing food or feeding the child, wash the hands

and utensils with C^-ean water.

Use unpolished hand-pounded or parboiled rice instead of

pplished rice.

3.

Whenever possible use only fresh fruits and vegetables.

. 4- Do not expose picked vegetables to sunlight.

5.

Clean and wash vegetables before cutting or slicing then.

6.

Avoid soaking cut vegetables in water before cooking.

7.

To reduce the incidence of diarrhoea caused by indiegestible

fords, nake then soft and digestible by:

2.

a.

b.

c.

d.

8.

- ■

soaking dried foods before cooking;

removing husks from grains;

cooking until soft;

mashing feeds.

Do. not throw away the water used for cooking vegetables but

use it for preparing soups or other dishes.

Avoid prolonged cooking, reheating already cooked foods, or keeping then warn over a period of tine..

MANY FAMILY DILTS CAN ffi IMIKOVED’ BY THE AbDUION OF:

i.

MORE HJLSES CR DAIS

x ii • GREEN LEAFY VEGETABLES

iii.

YELLOW FRUIT OR VEGETABLES

THESE/CHANGES GAN BENEFTjC All' IN THE' HOUSEHOID'.

Additional methods for increasing the nutritional values, of-foods

are as follows:

1. Sprouting pulses, i.e. Bengal gran, black gran or green gran,

increases the vitamin 0 and' ribonilavin (vitamin B) content.

Such processing also increases the digestibility of pulses

so that they are especially good foods for young children.

Sprouted pulses should be prepared and served either raw

or lightly cooked-in order to preserve the nutrients. .

2.

Fermenting cereal and dal increases the vitamin B content

■ of both foods. This is commonly done in South India, e.g.,

in preparing idli and dosa.'

3« Mixing a pulse with a cereal as in Khichadi increases the

quality of the protein eaten.. Less of each is required for

meeting-the daily requirements.

In annexure 11.5 a few nutritious recipes-are included. These

are selected according to the foods available: in the noritem, southern,

eastern and western regions of India.

11 .5

KITCHEN GARDENS

Encouraging families to plant kitchen gardens and to eat the produce

should, also bo considered a part of your work in the delivery of nutrition •

services tc tile’people who live in the area.

: 61.:

They need to be helped to understand how growing fruits and

vegetables for the family will help then to cat better and improve their health

health. Other benefits of kitchens gardens arc as follows:

i.

Less money is needed to buy food.

' ii. Fresh produce usually tastes better.

aii. Fresh fruits and vegetables contain more nutrients than those

that have been picked earlier, handled and transported.

iv.

Sullage water can be utilized, and is, at the same time, disposed

of in. a hygienic way.

You can help families who want to "plant a kitchen garden by giving

then advice so that they cs.n decide where to locate' it, uhe size of the

plot needed, and the amount and kinds of vegetables or fruit to be grown.

' If they require more information than you are able to provide, you can refer

them to the local agricultural, worker who is attached to the Block Development

Office.

Kitchen gardens should be located:

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

v.

near to the house for easy care;

near to the source of water;

sc that there is exposure to the sun;

in rich soil;

on land with a gentle slope and with good drainage.

In deciding the size of the plot, the family should- consider:

i. the time available. to cultivate it;

ii.

the number of members in the family.

In deciding the amounts and kinds of vegetables and fruit to grow,

the following factors should be considered.:

i.VJhat arc their food preferences?

Do

ii.

they need sone to eat fresh and others to store?

_iii .Which vegetables are needed to improve the family diet?

Is

iv.

fresh water or sullage water used for watering the garden?

(see also section 6.2.1)

EACH FAMILY SHOULD BE ENCOURAGED TO PL/.i-T AND E/J? THE VEGETABLES

Al® FRUIT THAT THEY- GROW IN THE KB? CHEN GARDEN SO THAT THEIR DIET

IS IMJROVED .‘

11.6

MAKING EFFECTIVE VISITS FOR IMPROVING FAMILY NUTRITION

In order to "alee your nutrition education activities effective, you

will liavc te collect or find out specific information related to the diet

ary habits and practices of. the community in order to decide how best to

assist them to improve their food habits. The information that you should

collect includes the following:

1 • The Banes of locally available foods, especially those that are

rich sources of proteins, minerals, and vitamins.

The typos of fo<d which arc being eaten or not being eaten bv

the family.

3.

Whether or not the pregnant and nursing women in the family are

being provided with extra amounts of food cr special foods.

4« The kinds of fo ds which- are toeing fed. to children above four

months of ago.

5.

The duration of breast feeding.

6.

Whether supplementary snacks are being given to young children

betr cn ••.oals until, thrnr rrc, nh"'n +.-> t

n fll-’n fn.T'il-'- -'cal.

2.

:62 :

7.

8.

11.7

Fbople * s knowledge about the nutritional value of fbods

and methods for preserving the nutrients of food.

Whether the family can afford to implement the suggested

changes in dietary practices.

HEALTH EDUCATION

Sone of the topics which you should talk about in relation to

inproving the diet are as follows:

1. Pregnant and Nursing Women

i. The need to include more proteins, vitamins and minerals

as well as additional calories in the daily diet.

2.“Pre-school Children.

i. Tlie continuation of breast feeding for the first year as

breast milk can supply protein to supplement the diet.

The importanace of nixing pulses and dais with the staple

cereal to increase the quality of protein.

iii.

The methods of preparing, food so as to make it softer

and more digestible.

iv.

The.importance of avoiding spices in the child's diet.

v.

The need for including body-building foods, protective

foods and energy-giving foods in tho 'cliild’s daily diet.

vi.

The importance of cleanliness in the preparation and

solving of food.

■ vii.’The need to ensure that the child gets a sufficient daily

diet-.

ii.

NUTRITION TEACHING FOR CHANGING BEHAVIOUR BECOMES MORE EFFECTIVE

WHEN FAMILY JRIOR-ITIES Ad© FEASIBILITY ARE OONSIDEIED AJ© THE • •

INFORMATION OR MESSAGE IS CLEARLY RELATED TO THE -IDENTIFIED PROBLEM.

11 .8

I-iALl-UTRITIOH

Malnutrition is a condition which occurs when the. body does not

get the proper kind of food an tho amounts that are needed for maintaining

health.

MALMJTRETION IS A COMMON HEALTH HIOBLEM -AMONG YOUNG CHILDREN IN

Iim. • EIGHT OUT OF EVERY TEN IRE-SCHOOL CHILDREN SUFFER FROM SO IE

DEGREE OF MALNUTRITION.________________________________________________

11.8.1

WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT 1 A.LLUTRIT ION

1. Poverty and parental ignorance regarding proper feeding

and diet for infants .and young children in addition to

incorrect family f ood habits and customs are nnj or factors

responsible, for malnutrition.’

2.

A failure to gain weight, or loss of weight in young children

.. are signs of early malnutrition.

■'3. Serial or repeated weighing is the best method for identifying

malnourished children.

4.

Early identification and correction of malnutrition are

important because severe malnutrition permanently affects the

physical and mental devel op.ientof chil dren and may load to

death.

: 63 :

’

5« Children who develop infections with-fever or who have worms

or repeated bouts of diarrhoea can develop rialnutrition if care

is not taken to meet the extra food requirements of the body.

6. Tlie larger the size of the family, the more likely is it that

one or more children will be malnourished.

7.

iJlien a child is ill, food and fluids should not be withheld but

should be given in order to prevent malnutrition.

8.

The largest number of malnourished children are between six months

and three years of age. Look for malnutrition in this age group

in the community.

9» The most common conditions caused by poor diet and incorrect

eating habits are:

i. Kwashiorkor, from lack of protein, e.g., dais, grams, milk

and eggs, as well as lack of calories.

Nutritional marasmus, from insufficient calories because of

not eating enough focd. ■

i ii. Anaemia, from lack of foods containing iron and vitamins,

g.,

e.

green leafy vegetables, eggs and foods from animal

sources,

iv.

Night blindness from lack of foods containing vitamin A,

e.g., yellow fruits and vegetables.

- Rickets from lack of foods containing vitamin D, and fats

v.

such as butter, groundnut oil, and eggs.

ii.

■ '

11.8.2

IDEIffIFICASION OF- MILHUTRITION IN IRE-SCHOOL CHILDREN

Young children have low nutritional reserves and, therefore,

require a relatively higher amount of calories and. proteins in order that !.

they may grow and develop normally, Insufficient foods of the right kind

in the diet of a young child will result in malnutrition.

There are several methods commonly used for identifying children

who are malnourished in a community. This can be done by:

1. Weighing and measuring children regularly.

2.Measuring the circumference of the upper arm.

3

.Systematically looking for children who are more likely thah

others to develop malnutrition.

4« Systematically looking for children who show signs and

symptoms of nutritional deficiency.

Your major responsibility is to identify children who are rialnourished as early as possible so that curative measures can be started prompt

ly.

1. Regular Weighing and Measuring: The best way to identify" young

children who are malnourished is to weigh and. measure then regu

larly (monthly for infants and at three to six month intervals

for those who are older). Those children who do not show consis

tent, growth and weight, gains over tine are either sick or mal

nourished (see Weight" Curve Chart, Fig. 11.3)..

Children arc usually weighed and measured in the clinics held at

the subcentres or by the health workers who nake regular domicil ia-ry visits.

Follow the directions on the Weight Curve Chart in deciding what action to

take when the weight of the.children is below line I (see fig. 11.3).

.Contd/64-

WEIGHT

in KILOff'I

PAFSiTS SHOULD D3 LiCCi t-AGSD 10 TAICE TULIP GHUDL3E KEGUURLY TO THE

OLZIO AT l.n. S\.TQT-'.TBU F" k 1IZTL1.'’ 2Wl;&’I0iJ, ’JEIGiilSG AI0 ?EASUR-

Weights of average well-fed healthy children should

be above'the uppernost line I.'

Children whose weight’ fails between lines I’and in.

arc tinder-nourished and require supflenontrry. feed

ing at litae»

Children whose weight falls below lino III

several;

rialncurishcd. Consult the doctor an.! follow hi s 'at Ivie:

Children whose weight falls below line IV will have tp

be hospitalized for- troatuent.

Fig. 11.3: ’’eight curve chart

2.

^ensuring Idd-ara Oircunfcren.ee: The identification of children who

are nalnourished can also bo done by rseasurihg tJ .c distance around, the

rdd-am. This should bo done by bavin;' the anti lianr-; lor.se at the side

•of the body and. jfLacing t?'.c ari.i circuuforcncp. sc.-Io s.t

? r.id-pcint

us showp in fig. 11.A:; h b. Any cliild between the ages -:f one and five

5=-oars is considered to be nalncurishe'." if this neastu'evsent is less than

12-8 cn.

*

'

.Ccntd/65-

: 65 :

IMMUNIZATION SCHEDULE

GUIDE TO BUTRITIOi!

S.'EjLFOX

hnirry: at birth or as soon

lifer as possible

feination of Scar

REACCIiLATION at one year

an- overj three years,

threafter

Date?

pate

Date

Date

D ,te

V.SERCU LOSIS (D.C.G)

Hnary: at birth er as soon

£ter as possible

Saoination of- Scar

Date

Date

^IHEHERIA-WHOOPING OOUGH3TAAUS)

(Triple Vaccination)

.-inarysfren /th month

Two injections at interval

?: 8-12 weeks

SISTER: 1-1/2 - 3 years

BIRTH TO 01® YEAR: Breast Feed’

Breast nilk is not enough for the baby after

six riontte. He needs additional nouritsh'• -ent• Continue breast feeding 'as long ab

possible and introduce the .following solids

gradually.

FOURTH liOBTII

Introduce frosh cow, buffalo, goat or tinned

powder nilk if breast i.-.ilk is insufficient.

Bice, Suji, Ragi (Dhajia) etc., well cooked

to a soft consistency and sweetened.

Vegetables like potato, carrot, cooked and

nashod.ft

' -+

hashed ripe banana-sweetened, orange/

sweet line/tonato juice.

Date

SIXTH liOnTH

Date

In addition to solid foods already given

Date

introduce the following:

•

Date

Bread,; biscuits,.dials’like; Bangal gran,

5 years

_________ _lentilj. red. gran' - well - cooked, FishILIOlu'ELITIS (Oral trivalent v;accine)

boiled, Boat - well- cocked and' tender,

Date

binary: fron /th -month

Eggs-half boiled, Curd, buttor-mlk-Clianna (Casein),, vegetables like cauli

iree doses by mouth

Z-6 weeks interval

Date

flower, cabbage, cucunbor, etc. All

HTPHOTD-FARATYRHOID

fruits.

Ol.G YEAR

rirary: at 1-1/2 years or l?ttier Date

'wo doses at 7-10 days

Child can share the. fa’lily food, except hot

■ interval

Date

and spiced foods. BOOSTER: Two doses at 7-10 days

Do not wait for the baby to cut his teeth

interval every year

Date

to give solid foods. He will digest well

cooked vegetables, rice, suji, etc., even if

TZPHTHEFXA - TETANUS

he has no teeth to chew then. .

rbinary: when triple vaccine

Wash your h a.nds oefore preparing food, cooking

given durin!" infancy

Date

or feeding.

•V- injections at 8-12 weeks

All foed for the baby should bo freshly prepared,

vo?ks interval

Date

no left-over be given.

£C-STER:One injection at 5 years Date

All utensils like cups, spoons, bottles etc.

doctor/nufse will record tine date of

should, be washed in boiled, water and kept covered.

gring the injection and toll you when to

srpg the child for the next one.________

i-I .C .H . CARD II

Child’ Card

(To be kept with the riother)

FHC/S .0/1 .C .D. Centre

.Registration No.

Vil"

••Katie:

. L/T .

. Date first seen:

Date of birth :

Orlc.

No. of brothers:

birt

Religion:

Sistr.

Diet:

Vegetarian/NcnHbther’n nano:

Occupation:

Fatter's name:

Occura.ti.on

:

Address a

:

Medical notes:

Blood Group :

Allergies:

Other infornation: ■_______ ,

Fatiily Hanning status of pt

Have your child weighed regt:.

Weight will be narked on thi

Bring your child to the cent:

month till his second birthd .

every three months till his’ f.

birthday and any tine he dot..,

appear well. Protect your cln

from diseases by giving hit; j.

zations shown on this card.

services are given without ■■■:'.

Ministry of Health and Fanil’,

planning, Birman Bhavan, New .

: 66 :

;.l

j|

5

j

0

7cci

I

|

“

Rod

u _

“

/ Acllovz I

12»5cli

I

Green

13 -5on

j

ARi; ar.?a.; j-epeece scale

---------------------------------------Colour Code

17.5cn

(adapted from

Ifel-nour- Possible Norml

iidnan Shakir

ished

Ifel-nntri

Sc David. Mbrloy-1

tion

The Lancet.P 758759, April 20,

1974

under 12.5cm Malnaurished

Yellow 12.5-I3~5cm Possible

mlnutritionGreen, over 13.5cm Normal

Red

Fig: 11.4b: Arm circumfcronco tape

3.

Characteristics' of Chaldron who' arc likely to Develop ihlnutrition:

The system tic search for :alnourished children in the cbpmnity can bo very

fruitful when your effort s are concentrated among those who have certain

social characteristics which are as follows:

i. The child is one of twins.,

ii.

The child has no living parents or. has a stepmother.

iii.

The child is cared for during the day by an .oldor sister or brother

while the mother works.

iv.

The child hah a younger sister or brother and the difference in ago

is loss than onc year,.

v.

There are four or more children in the, family. «

. vi. The child belongs to a migrant family4"'’('4,1

■<

'

vii.

Tho child .is obviously thinner and svrUef’ than others of his ago.

and which can cause sxgnxiacaau

.

. . .

occur in infants anl y'ung children, whereon others arc seen in persons

ox all aces. A feu er. ?, bo fatal or canto the underlying cause of death,

while others way lead to serious disability. Those diseases arc. as

follows:

Kwashierker (Protein Deficiency) is a serious disease which develops

in young children, usually between one and t> re.; years, who arc fed

diets which lack sufficient amounts of protein

calories to meet

body requirements (see fig.-11.5) • It can also .-l_’.olcp in previous

ly malnourished children following diseases such as measles, whoop

ing cough and .lalaria. If adequate treatment is not provided,

clnldrc.n with kwashiorkor can die (see section 11 .8.3) .

Fig : 11.5: Kwashiorkor

b.

i-ferasnus (see fig. 11.6) i.s the technic?! tor for the severely

wasted, undernourished- child or adult. It is a sorioud disease

which, can occur at any age when a person docs net oat or got enough

food which is require-’ by his body. In young children the condition c

often dcvolcps during the second year when breast feeding stops and

provision is not rads for giving Ilion sufficient amounts of nilk and

other feeds to meet the daily requirements, e.-;., small supplementary