RF_NUT_4_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_NUT_4_SUDHA

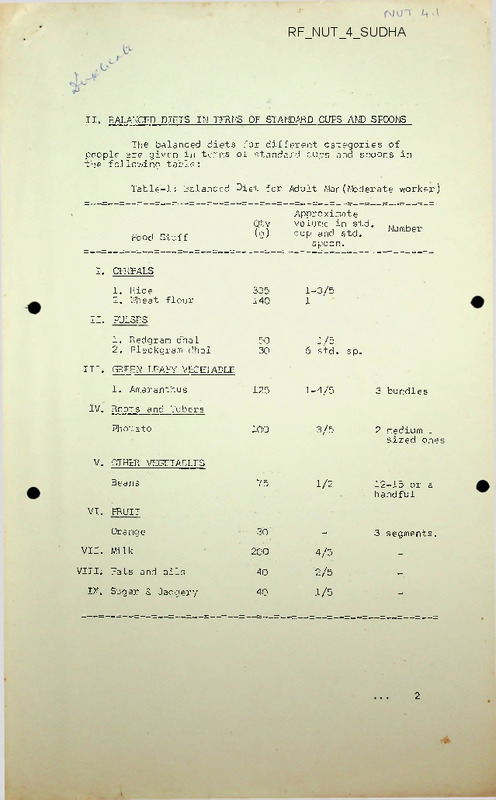

II. BALANCED DIETS IN TERMS OF STANDARD CUPS AND SPOONS

The balanced diets for different categories of

people are given in terms of standard cups and spoons in

the following table:

Table-1: Balanced Diet for Adult Mar(Moderate worker)

Food Stuff

Qtv

(9)

Approximate

volume in std •

cup and std.

spoon.

Number

I. CEREALS

1. Rice

2. Wheat flour

335

140

1-3/5

1

50

30

1/5

6 std. sp.

125

1-4/5

3 bundles

100

3/5

2 medium ~

sized one

75

1/2

12-15 or a

handful

3 segments.

II. PULSES

1. Redgram dhal

2, Elackgram dhal

III. GREEN LEAFY VEGETABLE

1. Amaranthus

IV. Roots and Tubers

Photato

V. OTHER VEGETABLES

Beans

VI. FRUIT

■ 30'

-

VII. Milk

200

4/5

-

VIII; Fats and oils

40

2/5

-

40

1/5

-

Orange

IX. Sugar 8. Jaggery

2

= 2 =

Table-II: Balanced “ let for an Adult Women (Moderate Worker)

(1]

_ 14)-” = - =

(2)

(3)

230

120

1

■ -4/5

45

25

-1/5

5 std. sp.

125

1-4/5

I, CEREAL

1. Rice

2. Wheat

II. PULSES

1. Rcdgram dhal

2. Blackgram dhal

III. GREEN LEAFY ’T’GrT/ ’JJE

Amaranth

3 bundles.

IV. ROOTS AND TUtERS

Potato

:

75

1/2

1

V. OTHER VEGETABLES - Beans

75

1/2

12-155or a

handful.

VI. FRUITS - Orange

30

-

3 segments

or a quarter

fruit.

VII. Milk

200

4/5

-

VIII. Fats and Oils

35

1/5

-

30

6 Std. sp. -

IX. Sugar and Jaggery

Table-Ill: Additional Al. .owance for Pregnancy and Lactation

I-actation

Pr.ignancy

Food Stuff

)

Ippx.Vol.

- .n std.cup.

50

1/5

Appx.Vol.

in std.cup

N0,

I. CEREALS:

Rice

Wheat

II. PULSES:

Redgram dhal

III. GREEN LEAFY

VEGETABLE

25

2/5

VI. Milk

V. Fats & Oils

125

i

40

60

1/5

2/5

20

2 std.sp.

3/4 bun-25

dies

- 125

15

2/5

3/4bundl-

1/2

4 std.sp.

4

= 3 =

Table - IV: Balanced Diet for a Child between the Age

3-6 years (Ref. - 6 year s qld child)

Food Stuff

Qty

(g)

Appx.Vol.in

std, cup

(1)

(2)

(3)

140

60

3/5

2/5

30

15

15

6 std. sp.

3 "

3 "

75

1-1/5 std.cup

No.’

I. CEREALS <

1. Rice )

2. Wheat -flour

-

II. PULSES

1. Redgram dhal

2. Blackgram dhal

3. Other grams

III. GREEN LFAFY VEGO ABLE:

Amaranth

1-i bundles

IV. ROOTS AID TUBERS

Potato

"

50

2/5

50

2/5 std.sp.

8-10 in no.

5 segments.

1 medium size

V. OTHER VEGETABLES

Beans'

VI. FRUITS

Orange

50

2/5- std.cup.

VII. Milk

250,

1

"

VIII. Fats and Oils

25

7

std.sp.

40

'8 std. sp.

IX. Sugar and Jaggery

plV'T^TIorS

HEALTH<NUTRITION AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

(an exploration focusing on Karnataka State)

This exploratory report, is the first step, towards the

initiation of a participator dialogue, between researchers

from various academic disciplines, health and development

action initiators, non-formal educators and others in

Karnataka state, on an area of increasing concern and

importance, with a view, to identify areas of interactive

and participator research, forcusing on agricultural workers

and rural communities.

(The report forms part of a larger, sabbatical assignment

undertaken by me at the London School of Hygiene and

Tropical Medicine from October 1986 to September 1987.

The assignment was an exploration of the relationships

between Health and Agricultural Development.

It included

a review of the health effects of Agricultural development

policies and the occupational health of Agricultural

workers.)

Ravi Narayan

Community

Health

Cell

Centre for Non-formal and continuing Education

Bangalore

(August 1987

)

HEALTH, NUTRITION AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

(an exploration focusing on Karnataka State

CONTENTS

Page

Introduction

Section I

1.

Karnataka State - a profile

2.

Agricultural Development in Karnataka - an overview

3.

The State of Food and Nutrition in Karnataka

4.

The Health Status in Karnataka - some indicators

Section II

5.

Drought - natural or man-made

6.

Kyasanur Forest Disease

7.

Irrigation and Malaria

8,

Japanese Encephalitis

9.

Handigodu Syndrome

10.

Endemic Genu Valgum

11.

Hazards of Sericulture

12.

Food toxins and contaminants

13.

The Eucalyptus Debate

14.

Tribal Health and Nutrition and the impact of

Development

15.

The environmental impact of Agroforestry

Section III

16.

Issues and research priorities

17.

A plan of Action

18.

A bibliography and resource list

)

11.

HAZARDS OF SERICULTURE

The sericulture agro-industry is a rapidly expanding, high priority

development programme which has seen a 300% increase in the context of land

being brought under mulberry cultivation in the last 30 years.

Mulberry

leaves are eaten by the caterpillar Bombyx mori to form its cocoon of

protein silk. The rearing and feeding of caterpillars, the supervision and

'sunning', important processes during cocoon, formation are family based

rural cottage industries spread throughout the rain fed and irrigated

Southern, interior Karnataka.

The cocoons are sold in special markets and the silk thread is removed in

special reeling and spinning units which are also rurally based but not

always home based.

The silk thread is then wove'n into silk of various grades with both

traditional hand looms and electrically operated power looms which are also

part of rural industry.

Studies undertaken by the Ross Unit of occupational health based at St.

Johns Medical College, Bangalore, in Mallur and neighbouring villages of

Kolar district established that many sericulture workers in both homes and

reeling units, who handle the silk cocoons, have skin and respiratory

ailments, an atopic/allergic reaction to certain antigenic products related

to the silk protein.

These were demonstrated in small pilot studies but

larger surveys are required to establish the extent of this problem and

magnitude or morbidity across the agro-industry.

The weaving units have been inadequately assessed from an occupational

health point of view but the noise levels are in the hazardous range and

noise induced deafness could well be a significant problem. The problem of

child labour is however a more important problem in this aspect of the

industry.

This is partly because of the fact that weaving is a family

based industry and all members of the family are inducted into service.

However with the increase of power looms the situation is rapidly changing

and workers other than family members need to be employed.

These

additional workers include children, often under very exploitative wage

conditions and school dropout rates are usually high in villages with

sericulture development especially weaving units. The health problems that

these child workers face during their work in noisy, crowded, poorly lit

loom sheds need immediate assessment.

With the rapid growth of sericulture, the magnitude of the above hazards

especially in terms of population at risk, will increase greatly in the

years to come.

A larger issue of importance will be the increasing

diversion of land, normally used for food and fodder, to an export oriented

cash crop, which could have serious repercussions for the community.

In

many areas where sericulture development has taken place, there is

additionally diversions of land for eucalyptus as well.

Together, this

diversion would mean decrease in local food grain production.

There is

already increasing evidence that this is taking place in some regions like

Kolar district in Karnataka and the long term health and nutrition

consequences are obvious.

31

N_g.TR I 7 1 0 N __ Z^c^-ccxl

JL

Milk: It is an ides’.1 food for infants and children and a good supplementary

food for adults. It is nearly a complete food existing in nature. It contains

all the nutrients.

Composition:

Protein

Fat

Lactose

Calories

Rich:

(hrs, per 100 gms

*

Cow1s milk'

Buffalo's milk

Human milk

3.2

4.1

4.4

67

4.3

8.8'

5.0

117

1.1

3.4

7.4

65

in calcium

Deficient:

1^. is deficient in iron and vitamin C

Daily rt-cuirement:

Adults

Children

Expectant mothers

10 oz or 284 gms (non—vegetarian

requirement - 20 oz or 568 gms)

20 oz

40 6z

Milk borne infections: from the animal - Bovine tuberculoses, (Brucellosis)

anthrax, achinomycosis, Q. Fever

from the human - typhoid, paratyphoid, dyssntries,

handler &

cholera, diphtheria, infective

environment

hepatitis.

Preventjon:

Pasteurization -if effectively done - phosphatase tost will be

Boiling

negative

Sice: Kain cereal consumed in south India, cheapest source of energy and

contributes 70-80% of calories. Main source of thiamine add nicotinic acid.

By virtue of its quantity it provides nearly 50% of protein requirements.

Proteins of rice is of better quality than wheat although the protein content

cf wheat is more-.

--Composition:

Gms, pe r 100 grs

Protein

Raw rice(mld)6.8

Parboiled-. .

rice Vmld)

6.4

mgm

mgm

CHO

Fat

Thiamine

Nicotinic

78.2

0.5

0.06

1.9

79.0

0.4

0..21

3.6

Parboiled rice is superior in nutritive value to raw rice as regards the

thiamine and nicotinic acid are concerned.

Daily requirements: 14.$zs or 400 gms Ir milled raw rice is being consumed,

it cm bo partially substituted by wheat, jowar or ragi. Thic improves <he

nutritive value of the diet (N.B. 100 gms or rice contains more pre reins than

in 100 gms of milk).

Wheat: Next to rice, wheat is the most important cereal

Daily requirements:

14 oz or 400 gms

Composition: (whole wheat)

Per 100 uns

iMMa

11-S

Fat

1.5 gms

CHO

71.2 gms

Thiamine

0.45mgms

Niacin

5.60mgms

Though it has protein to the extent of 11.8% it lacks in lysine» l| is a good

source of thiamine and niacin.

Millets: Jowar and Ragi : - Jowar is deficient in lysine and has an excess

of leucine. The consumption of jowar is occasionally found to be issociated

with pellagra.

?agi is a popular millet in South India. It is very rich in calcium, and is

a''ir source of iron, phosphorous and thiamine.

-2-

Vily requirements:

Ip combination with cereals daily requirement is 14 oz

or 400 gms.

Jowar

Ragi

Prdrin

gm

CHO

gm

10.4

7.3

72.6

72.0

Calcium

gm

25.0

344.0

Pulses: Pulses are next in importance to cereals as an article of diet in

India. The common pulses ased are red gram, green gram, bl..ck gram dhal, Bengal

gram, dry beans, and dried peas.

Pulses are rich in protein containing about 20-25 g of protein per' 100 gms. In

vegeterian diets, pulse1 are the main source of protein. Pulse ■ ar? good sour-ns

cf B group vitamins, especially thiamine and riboflavins. Sprouted pulses a?e

good sources of vitamin C.

Daily requirements:

3 oz or 85 gms

Proteins $

Bengal gram

Black gram

Reg gram

Green gram

17.1

24.0

22.3

24.0

Mgn t>er 100 gms

mgm

mgm

m<Tn

Ribofirvine

Thiamine

Niacin

0.3

0.42

0.45

0.47

0.15

0.37

0.19

0.39

2. 9

2.0

2. 9

2.1

iron

10.2

9.1

5.8

7.3

Groundnuts: Groundnuts or Peanuts are ex:tensively ,grown in Indi,a. It is

rich in fat, protein is equal to pulses. It is also rich in nico tinic acid.

thiamine and riboflavine.

Composition;

Per 100 gms

Protein

Fat

OHO

Thiamine

Riboflavine.

Nicotinic acid

Ic-ily requirements:

25.3$

40,1$

26,1$

0,9 mg®

O.'IS mgm

19/9 mgm

5

jj

j

jj

h

J

Groundnuts after

extraction of fat is a cheap

and rich source of proteins

1^ combination with pulses 3 oz

Green leafy vegetables: Eg. spinach, amaranth, fenu greek, cabbage are cheapest

protective foods. These are excellent source of carotene and vitamin C.

They are also good sources of calcium, iron, riboflavine and fo,ic acid. They

provide cellulose which acts as roughage. It plays an important role in persons

who go on diet to cut down calories.

Daily requirements:

4 oz or 114 gms.

Oil: Eg. groundnut oil, gingelly oil etc. vegetable fat. It is 100$ fat,

yields 900 calories per 100 gms. Contains no vitamin, contains more of

polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lowers the serum cholestrol.

Daily requirements:

2 oz or 57 gms

Ghee: Animal. Except for little moisture it nearly cent per cent fat. Yields

between 820 to 895 calories. Good source of vitamin A (200 i.u./lOO gms)

contains more of saturated fatty acid and hence tries to raise serum cholestrol.

Dail^ requirements:

In combination with other fa^,.like-oil 2 oz (n.B.

vegetable fats usually do not cont'i n vitamin A)

7anaepathi: Popular cooking media in our country. It is manufactured by

hydrogenation of vegetable oils. 0n hydrogenation saturated fatty acid content

increases.*

Gives about 7)0 i;u. of A and 150 i.u. of 'D' per 100 gms. It is

.00$ fat and yields 900 calories.

-:_lv requirement: In combination with other fats 2 oz.

’c added by manufacturers accordin." to gover-im-'.^t

-5■ & Jaggery: These are carbohydrate foods. Sugar is a pure ca fh-hyd

end contains no proteins, fats or minerals. 400 cal./lCO gm<

<.aggery: Is used in place of sugar. 383 cal./lOO gms. It is also rich

source of iron 11.4 mgm/100 g.

Daily requirement:

Sugar/and/or jaggery - 2 oz or 5'i < ac.

/feu: It is an important source of animal protein. It contains also the

nutrients except CHO.lt contains protein, "at, calciinr, all the vitamin

except C. It is a complete protein containing all essential amino acids.

Composition:

Protein

Fat

Minerals

K Cals

Dally requirement:

Hoot and tubers:

13.3P

13.3G‘’

1+3

1 egg (ly oz)

Generally used as vegetables.

Potatoes, tap'iooa, carrot, onion, raddish. These especially potatoes are

rich in CHO. Poor source of fac and protein. Good source of calcium and

phosphorous.

Carrot rich in carotene

Potatoes rich in vitamin C

Daily requirement:

3 ozs or 85 gms.

IIHtlWtl!

Assessment of Protein-energy Malnutrition (PEN)

a)

Biochemical tests

Changes in the body's composition in malnutrition are most readily

assessed in general terms by anthropometric techniques which measure the mass

of tissue in the body or arm etc. Many biochemical tests are indirect

measures of the processes which are in progress during the course of

developing malnutrition. Biochemical tests may therefore be more sensitive

to recent dietary experience and may revert rapidly towards normal when a

malnourished child has only just started to recover.

Tests can be categorised into measurements on i) blood and ii) urine.

Blood tests are not always acceptable in population studies but provide the

opportunity for other useful tests eg. Hb.

Blood tests

1.

Circulating proteins of liver origin

a) Albumin: insensitive but important when low

b)

c)

d)

e)

Transferrin: studied only in severe PEM

Lipoproteins: no more sensitive than albumin

Thyroxine binding pre-albumin: preliminary studies only

Pseudocholinesterase and other liver enzymes: insensitive

Liver-produced proteins are particularly sensitive to a fall in the

dietary protein intake but the concentration in the blood depends not just

on the rate of synthesis but also on the breakdown rate of each protein.

The breakdown rate of albumin adjusts as the synthesis rate falls thus

minimising the effect of the reduced intake of protein. Transferrin does

not show this phenomenon - nor probably does T.B.P.A. but little wprk on

this protein so far. Both proteins may prove more sensitive than albumin

which is often near normal in marasmus * Transferrin and T.B.P.A. show

greater falls than albumin in kwashiorkor but their levels have not been

reported in marasmus. Both tests are time consuming and expensive.

Lipoproteins behave rather like albumin: although both are rather insensitive

any fall is important. At albumin levels below 3-0 gm/100 ml a whole range

of other disorders of hormonal and amino acid concentration are evident and

reflect impaired hepatic function.

Albumin is the simplest and most useful blood test for PEM but is still

of no value_in_demonstrating the extent of growth failure or wasting jn

marasmic children.

2.

Indices of recent absorption: urea, cholesterol.

3. Amino acid levels a) valine reduced particularly in kwashiorkor

b) alanine low in starvation states eg. marasmus

but too variable. Tends to rise in protein

deficiency.

Non-essential amino acids

c) Ratio essential amino acids

. Low in

kwashiorkor, normal in marasmus. Ljkel^vo

change within 2-3 days of altering the diet.

- 2 -

Urinary tests

1. Creatinine excretion. Creatinine is spontaneously formed by the

cyclization of creatine phosphate (C.P.) present as a high-energy compound

in muscle. Creatinine is excreted unchanged in the trine, the rate reflecting

the mass of C.P. in the body. Since the concentration of C.P. is constant

in muscle, its exclusive site, the excretion rate of creatinine reflects

muscle mass. Creatinine excretion is, however, somewhat variable, and in field

studies accurate urine collections for long times are impracticable. Three

hour collections have been tried - coefficient of variation 25%; 24 hour

collections - 10% coefficient. Most meaningful method is to express the

creatinine in terms of the child's height in cm. since this will indicate

the amount of muscle that a child has for his size. Muscle mass in Kg =

creatinine excretion in mgm. » 50. Creatinine is theoretically one of the

best indices of malnutrition since it■ does reflect the pvtent of-muscle.

atrophy - a key featurfi—of-the whole spectrum of PEM from kwashiorkor to

marasmusCreatinine excretion is increased for a short time during stress

eg. trauma or infection.

2.

Urinary tests indicating recent dietary intake.

a) Total Urinary N

. x Urea N

bl —-----

,

.....

% falls on a low protein diet

> Urea N ms

*

mg creatinine1" suitable for single urine but limited usefulness..

d) Urinary SO^/creatinine: ? reflects intake of S-amino acids.

Limited usefulness;,

3.

a) Urinary Hydroxyproline 24 hr excretion: reflects the rate of

growth and related to the turnover of collagen. Increased

excretion in infection; not easy to measure.

b) Hydroxyproline index (OHPs x body wt)

creatinine

Disadvantage of two variables each of which may affect index.

Useful for single urine. Index age dependent and thought to

reflect growth.

Significance of biochemical values

Deficit

<2.8

At risk

2.8 - 3.5

Amino acid ratio

> 3.0

2.0 - 3.0

Acceptable

> 3.5

< 2.0

Other index

< 2

-

> 2

Urea N/creatinine

< 10

Serum albumin

> 10

Serum albumin is the most commonly used biochemical index but it reflects

the extent of liver synthesis which appears well maintained in starvation

states and the index.although simpler, is less sensitive than the T.B.P.A. and

transferrin blood concentrations. Urinary creatinine is the biochemical test

of choice for showing the extent of the nutritional deficit but it is impracti

cable to obtain an accurate estimate of muscle mass by this technique.

W.P.T. James,

February, 1973

Skinfolds

Anthropometric Assessment (Cont.)

Use Harpenden calipers. If other types of caliper are used

the standards for these calipers must be used as calipers with

different pressures and area of cross section at jaws give

different results.

The standard measurements are:

1. Biceps: over the mid-point of the muscle belly with the arm

resting supinated on the subject's thigh.

2. Triceps: over the mid-point of the muscle belly, mid-way between

the olecranon and the tip of the acromion, with the upper arm

hanging vertically (Edwards, Hammond, Healy, Tanner and Whitehouse,

1955 , Brit.J.Nutr. volume 9, p.133, 1955.)

3.

4.

Subscapular: just below the tip of the inferior angle of the

scapula, at an angle of about 45 to the vertical.

Suprailiac: just above the iliac crest in the mid-axillary line.

At these four sites, the skinfold is pinched up firmly between the

thumb and forefinger and pulled away slightly from the underlying

tissues before applying the calipers for the measurement.

If only a single measurement is taken, the triceps skinfold is

the most useful.

If several measurements are made an estimate of

total body fat can be made from the total of four skinfolds (Dumin

and Rahaman. Br.J.Nutr. 1967, vol.21, p.681).

The differences in fat percentages become progressively smaller

for each 5 cm. difference in skinfold as the skinfolds increase in

size.

Percentages of fat corresponding to the total value of

skinfolds at four sites (biceps, triceps, subscapular

and suprailiac)

Total

skinfold

(mm)

15

20

25

50

55

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

___ Fat

Men

5.5

9.0

11.5

13.5

15.5

17.0

I8.5

20.0

21.0

22.0

23.0

24.0

25.0

26.0

26.5

■ 27.5

28.0

(% body weight) ___________

Women

Boys

Girls

15.5

I8.5

21.0

23.0

24.5

26.0

27.5

29.0

30.0

31.0

52.5

55.5

54-0

55.0

36.0

56.5

9.0

12.5

15.5

17-5

19.5

21.5

23.0

24.O

25.5

26.5

27.5

28.5

29.5

—

-

12.5

16.0

19.0

2i^°MMUNJTy HEALTH CELL

(First Floo.-JSt. Marks Road

25.O BANGALORE-560 001

27.0

28.5

29.5

30.5

32.0

55-0

34.0

-

—

—

-

(Rounding off in the percentages of fat accounts for the differences

between adjoining values not being uniform^

The following measurements of triceps skinfold thickness are those

which can be considered as including the ran.'.e of "normal" values for

French-Canadian schoolchildren measured in 1970.

Lower limit

3rd percentile

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Upper limit

97th percentile

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

5.6

5-5

5.4

5-3

5-3

5-A

5.5

5.6

5.5

5.3

5.1

6.4

6.1

6.3

6.5

6.7

6.8

6.9

7.0

7-3

7-9

8.5

12.6

11.9

12.9

14.5

16.4

18.0

19.0

19.8

19.8

19.0

18.0

15.0

16.0

17.5

19.5

21.0

21.5

22.0

22.J

22.8

23.3

23.8

Read from grapsh of Jenicek and Demirjan, Amer. 1I. Clin. Nutr,

1972, 25, 576.

L

Robson et al (Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 1971, 24, 864) have found that

Black children in Dominica have much thinner triceps skinfolds than

London White schoolchildren although the std^fficapular measurements of the

two groups are the same. A racial difference in triceps skinfolds has

therefore been suggested and would certainly explain the very high

proportion of West Indian Black children with thin triceps values.

However, American Black and White children chow no differences in their

response in triceps or subscapular skinfolds to changes in weight, and

this suggests that the differences in West Indian children's subcutaneous

layer of fat may be determined by environmental rather tnan ethnic

factored

Differences in other skinfolds have been found e.g. subscapular

skin thickness is different in French-Canadian and London children but

the triceps measurements are approximately equal.

Changes in skinfold thickness have been observed over the years

e.g. secular changes in triceps measurements have been very marked in

Canadian children with an increase from 6 to 10mm average in boys'

values in the last 17 years. Nutritional factors rather than genetic

control therefore may be more important.

Most London and Canadian children are weaned early onto diets

containing very high quantities of protein and energy. This will produce

faster growth rates with an increased likelihood of childhood obesity.

Many young obese adults were obese in childhood and have an excessive

number of fat cells in their bodies. This excess, which is probably

determined in the first six to 24 months of life, "programmes" the body

for life-long obesity and perhaps an earlier death. Present values for

skinfold measurements although "normal" may not be "ideal", and we cannot

be certain of the significance of thin triceps skinfold measurements in

community surveys. Sequential changes in an individual's measurements

will be significant, however, and the finding of a low percentage of

body weight as fat means that a subject's energy reserves are limited.

W.P.T. James

VITAMIN AND MINERALS

Daily Requirement for an adult

Vitamin A

5000 I.U.

1. Xeropthalmia. Blindness

2. Decrease Resistance to UR VI

5. Inner Ear Deafness

4. Acne

Vitamin D

400 I.U.

1. Rickets in children

2. Osteomalacia in adults

Thiamine

1.5 mgms

1. Beri Beri

2. Neuritis

Riboflavine

1.5 mgms

. Angular Stomatitis

. Photoph

Glossitis

Nicotinic Acid

15 mgms

Cyanocobalamine

1 mcg.

Pathothemic Acid

5 mgms

Choline Parent substance

acetylcholine

and a constituent

of Lecithin

2 gms

Deposition of fat i.1 liver and

Haemorrhagic degen 'ration of

liver and kidney

Ascorbic acid

50 gms

1. Scurvy

2. Decrease resistance to infection

Pellcgara

Anaemia

1. Chick Pellagara

2, Hair growth

Anaemia

Folic acid

1.5 mgms.

Vitamin E & K

Not known

1. Vitamin E_- sterility in male

?, Vitamin K - Bypoprothromhinaemia

Ca.

1 gm.

1. Borne defects

2. Hair

5. Blood disease

Iron

15 mgms.

Anaemia

Fluoride, Ion

in water

1-2 ppm

Dental caries

‘

Essential Fatty acids nutritionally important and. necessary tor growth

They are Linoleic, Linolenic and Arachidonic acids. They cinnot be synthesised

in the body and have to be supplied in the diet. Linoleic- -nd Linoenic acid

are of veritable origin and present in cotton seed, groundnut and linsee o_ls

while Arachidonic acid is of fish and animal origin. E..F.A. regulate

cholesterol metabolism.

DAILY BALANCED DIET FOR AN ADULT

Gms

Cereals (rice chiefly milled)

Dhal (red gram)

Green vegetable (cabbage)

Potatoes

Cauliflower

Banana

Oils ft fats

Sugar (in tea, coffee & sweets)

Milk (cow)

Mutton

Egg

Agathi

<;ais

500 (540x~) 1020

5.55

100

2"

100

T

100

51

100

15C

150

45C

50

40C

100

6"

100

200 (194x2) 52£

85

50

45

50 ■

J1U

COMMUNITY ^^harksRoad

47n.(F

^

*

t

Floor) - 56o()O1

Food System and Society

b ft N G'A u °

Interface between the Socio-economic Status and the

Health and Nutritional Status of Women and pre-School

Children of the Rural and Urban Poor in Eastern India.

(Abstract)

Dr. B. Chattopadhyay, D.Litt.(Econ)

Consultant, UNRISD, Geneva.

I.

Introduction. This project sponsored by a number of U.N. Agencies such as

the UN Research Institute for Social Development, Geneva, UN University,

Tokyo, and the UNICEF, Nev/ Delhi, has grown out of a proposal before the UN

System, mooted after the World Food Conference, for a global study of famine

risk in the modern world.

It was felt that the study of famine

risk would be

too narrow because of various definitional problems of identyfying famine.

Famine Codes and Scarcity Manuals in different parts of Hie world use different

definitions.

Moreover, nothwithstanding the prevalence of the Famine Code in

India, the Bengal famine of 1943 was never declared to be a famine, although

perhaps three million people had died.

It was also felt that famine risk is

endemic in large parts of the Third V/orld because of the extreme vulnerability

of certain segments of the population, during certain seasons, almost every

year, to conditions of food shortage percipitated by lack of purchasing power

and employment.

It was felt that such vulnerability exposing segments of the

population to acute distress conditions even at the slightest fluctuation of

food production, caused by drought or flood, is a consequence of an essentially

multi-faceted structure of determination involving a large number of variables -

ecological, physiographic, socio-economic, technological and cultural.

It was

consequently felt that a System Approach in the proper sense of the term would

be the-best methodological standpoint for the analysis of food systems and

society in all their interaction.

Famine, or acute distress, would then

represent breakdown points of the system through which the system reproduces

itself.— the breakdown points acting more like safety valves.

II.The Components . Food System and Society is then considered to be a

generalised system like any other system.

sub-systems.

It would be composed of a set of

Notionally, w£ think of the main sub-systems of the general

system called "Food Systems and Society" envisaged in terms of information and

output flows and feed-backs.

The Sub-System, which is relatively stable

over the relevant time -span, is the Ecological and Physiographic’ Sub-System,

changes in which can be observed only over the relatively-long run.

The

Ecological and Physiographic Sub-System can be represented and measured, in

terms of parameters such as those relating to the.water regime(rain fall, sub

soil water, surface run off etc.), relief, forest-cover, basic soil properties

etc.

In some cases fluctuations, such as those in rainfall, can also be

parametrised whereby short run changes can be impounded into long run parameters

2

The Ecological - Physiographic Sub-System thus, represented by a set of

parameters, provide, so to speak, the stage for the inter-play of socio

economic forces including property relations, quality and quantity of the

labour force, technology and culture.

It is through the interaction of the

Ecological - Physiographic Sub-System and the Socio-economic Sub-System that

specified configurations of the food system arise.

The Socio-economic Sub-System can be represented by a whole range of

parameters such as pattern of land holdings, cropping pattern and intensities,

incidence of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, incidence of landless

Agricultural labour, interaction with the Urban Metropolitan centres,

availability of controlled irrigation, technology, particularly agricultural

technology, etc.

A whole range of data is available to enable us to express

these parameters in terms of suitable magnitudes on different scales.

The

Physiographic - Ecological Sub-System provides a range of information inputs

into the Socio-economic Sub-System which digests these inputs generating a

structure of production and distribution of food with different social forces

exercising different degrees of control over access to food

.

*

It is possible,.

then, to think of methods of subsuming the entire range of variables -and

parameters in a Composite Index of Food Insecurity to which specified segments

of the population, such as, Scheduled Castes, and.Scheduled Tribes or landless

labourers, are exposed.

The net output of the interaction'of the first two

sub-systems is, then, this composite index of food insecurity, which in turn

becomes the information-input for the Nutritional and Health Sub-System.

It is

possible that the Ecological —Physiographic■ Sub-System also provides certain

direct information inputs of an epidemiological character to the Health and

Nutritional Sub-System.

For instance, data show that in eastern India

incidence of Gastro-Enteritis has a certain seasonal profile, which may be the

consequence of environmental hazards compounded with food insecurity.

The Nutritional and Health Sub-System can also be represented by a

range of parameters relating to Nutritional levels,'deficiency signs, morbidity

and mortality .profiles, access to Health Care delivery system of, particularly,

the segments who suffer from Food Insecurity etc.

factors

practices

There may be other associational

such as Health Culture and Health Habits, Community Habits and Taboos,

of pre-Natal and post-Natal care. etc.

The purpose of the project being reported here is to identify the

interaction among the three major sub-systems in terms of a.whole range of

parameters to arrive at a composite measure of the entire system of interactions

* For instance, .the interaction between the two.sub-systems is such im

Eastern India that tribals and semi-tribals have been driven to the

low-productive, arid plateau regions.

3

anong the variables, and, finally to arrive at a multifactor index of

vulnerability.

The idea is to use techniques of estimation of a Multi-Variate

System model methods of cluster analysis, factor analysis etc. to arrive at a

composite measure of vulnerability in regard to Food, Nutrition

and Health.

Such an index of vulnerability will, as far as can be envisaged at the present

state of our research, be in the nature of a Mahalanobis Distance measure in

multi-dimensional spa®..

It can provide important guidelines for resource

allocation between regions and communities, and a method of evaluation

&

monitoring.

III.

The Survey .

Ehe foregoing analytical scheme, largely quantitative in

nature, will be based on an extensive compilation of available secondary and

primary data from various agencies in Eastern India, Governmental ani otherwise.

It is expected that the Multi-Variate analytical techniques used in course of

arriving ax the composite Distance Measure will also tell us quite a bit about

the relative weights of the various components of the system represented by the

whole range of parameters,which we propose to estimate for each of the 46 districts

in the three states of Eastern India, West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

However,

since there is no a priori general theoretical framework in the revived body of

knowledge for identyfing the linkages among the variables and the sub systems,

it is proposed to identify some of the linkages by examining the situation at the

micro-level, in clusters of villages in a set of sample districts : four rural

districts and two urban areas in each of .the three, states of West Bengal, Bihar

and Orissa, including the Calcutta Metropolitan Development area.

These micro-

surveys are designed to capture.the linkages among the three sub systems for

specified communities, households and individuals, including women and pre-school

children.

The survey is purposive and is aimed at catching the typologies of

vulnerability under different Ecological and Demographic contexts in the three

states of Eastern India.

It may be possible to evolve certain norms specific to

given connuni.ties — norms which are not based on studies on communities in the

U.S.A, or such other Western countries.- The physiology ' of the tribal nan in,

say, Phulbani in Orissa is not likely to be the same as that of a Toxas peanut

farmer, for example.

The survey will also attempt diagnostic- studies of disease

profiles and access to health care delivery; it will not use any inputs such as

drugs, pills, special feeding pi-ogramneR etc. to elicit information from the

community.

Instead, an attempt will be made to report back to the community sone

of the more easily comprehensive findings through Audio-Visual techniques readily

understood by indigent segments of the inhabitants in the target areas, so that

the community gains a degree of understanding about its human predicament, and

may think of doing something at its own initiative to rectify the perceived

inadequacies.

IV.

The Team. Inevitably, the team is composed of a wide rarge of disciplines —

Medical Scientists, Statisticians, Economists, Geographers, Anthropologists,

Agricultural Scientists etc. At the moment we have a team of about 20 professionals

engaged in this work, supported by a number of computing hands and investigators.

Our main problem at the current phase of our research is the challenge of ihe

massive compilation and processing of the secondary data, and the challenge of

Rett~ing up the logisties of the survey which will begin in West Bengal and Orissa

by the middle of this year.

^■<S

/

C- l<-

C^

y^t^7tf.(_uCx7

^cbCc^l,

Ci-^dAa-YL'iu al

JZx^a/tLe

4>-^<

dLel'a^

<<?

Au?..-J /A

rx/uT

INTEGRATION OF A NUTRITION PROGRAMME WITH HEALTH AND

----AGRIOULTURE

*

--COMMuNHV

-

^-8.

w

c-tL

Vt i kS

"''•^HGAtOTE-MOOOtJolken

In the Indian Social Institute Training Centre

from which I come, we are trying to help fulltimers in rural development from South East Asian countries to

critically evaluate the work their organisation is doing. This

requires first a critical understanding-of their own society:

What is the prevailing concept of under-development and

development which is at the base of all development policies of

their government? This sort of approach has made us all increasingly

aware of the deeper causes which lay behind a process of change we

call ’development’, yet in reality is the development of certain

strata in society only. In an unjust distribution of development

gains we find the basic answer'to the questions Why can the masses

not be mobilised (blocking of motivation), why can the local

resources not be tapped?

Introduction:

1.

The issue of Justice

It is relevant to mention this in the introduction to our theme:

Integration of a Nutrition Programme with Health and Agriculture.

It is meaningful to link these three sectors together? but to be

so more fully, these have to be placed into the totality of social

reality of a country.. I am very much impressed that this Seminar

has been guided by a paper of high quality, indicating that those

developing countries which have brought about a radical transforma

tion of inegalitarian structures have been most successful in

meeting the basic needs of the people despite scarcity of resources.

Only in the context of this total transformation was it possible

to create a new system of Agriculture and a new health system. An

equitable distribution of increased food production and the

priorities of the health-care-system eliminated basically the

problem of malnutrition. The question is then raised: Where this

re-structuring of society has not occurred: "Is it the fate of

nutrition planners to be 1 patient revolutionaries1 biding his time

with pilot projects and marginal influence". For us in India this

question has a very realistic ring. What to say about the apparent

new commitment of Governments to Nutrition Programmes which

excludes however, the more decisive commitment to transforming

unjust and oppressive social structures responsible for the

constant widening gap between rich and poor? I’ll tell you

frankly my opinion: Within oppressive and unjust social structures

creative participation of the people can never be what it should.

The proof is the constantly increasing percentage of the people

who are forced to live below the subsistance level.

In such a situation what real hope can integration of nutrition

programmes with health and agriculture give? I believe the honest

answer is in the saying: Better light a candle than curse the

darkness. Symbolic islands can be created through this approach,

provided it is based on a philosophy of immense trust in the

...2/.

2

capacity of the people. Where this real love of the people

- animates nutrition^-programme-planners an approach which integrates

nutrition with health arid agriculture can make a great difference.

2.

Example of a comprehensive rural health programme

I wish to give this example because it constitutes quite a

sizeable island, covering a population of 40,000. It was

initiated in 1970 by a doctor couple (Dr. Arole) in Jamked,

Maharashtra, and covers about 30 villages. The project demonstrates

it seems to me how best the Chinese model of comprehensive

health-care can be implemented in a feudal society..

This comprehensive rural health project is guided by the three

basic concepts of a) participation of the community

b) delegation of responsibility to lesser

trained personnel

c) mobile health' teams

Under Five Clinics are central to the activities of the project..

as one of the goals of the project is to reduce mortality rate

of the under five by 50% within four years. Through these Clinics

supplimentary feeding is carried out in most villages. The

community takes the responsibility of providing fuel and utensils,

they do the actual cooking. The stress of health education and

the actual experience of improved health among the children has

motivated the community to work for better water supply, and to

set apart some land to grow food for this programme. The project

is collaborating with agencies involved in agricultural development.

But in comparison with another major project in this state, in

Kanakapura Taluka, where the thrust has been in agricultiral

extension for small farmers, more than on nutritional programmes,

the impact of increased agricultural production seemed to have

remained small. Care of minor illnesses, health and nutrition

education of the mothers, and immunisation programmes arranged by

the villagers themselves, are other activities of these under

Five Clinics. I do not think it necessary to give more details

about the various other goals and activities of this project.

Instead I wish to point out some of its characteristics which have

impressed me most and which are relevant for our purpose.

Emphasis on the educational aspect of the programme

Not only the mothers but the whole community is exposed to

continuous nutrition and health education. Not only the explanations

given by health workers, but also the actual results of a programme

in which many take an active part, achieve this result. I was

much impressed by the villager, who has been trained as health

educator, and wanders from village to village. He had a session

in the village I visited. In a dramatic way he explained his

charts to the villagers seated on the ground around him. Since

I knew the local language, I myself got fascinated by his way of

communicating, pointing out concrete examples of his reference among

the audience. I understood that the best communicators are

’found among the people themselves.

a)

3 -

b) The people are made to understand that food-supply from outside

was only meant as a starter. They would have to grow the food

required for feeding programmes. Some, members of the community

did get motivated to donate some of their land.

c) The nutrition programme being part of a comprehensive health

programme meeting the basic health needs of the people, supported

by locaH resources (primary health workers, collaborators and

material supplies),- has a very strong demonstration effect. As

child mortality declined, motivation for planning the family

became effective.

d) The educational impact of the programme is very much

strengthened by the central role of the local permanent workers

who are fully identified with the community. Much of the training

of other health and nutrition workers is also given locally. They

escape thus getting alienated from the people through a sophisticated

training in a city. Experience has shown that team-members trained

in city-conditions, tend to leave this rural areas soon agafcu

Evaluation; The Jamked project shows the possibility of creating

health through a comprehensive approach in which community teams,

inspired by dedicated animators (the Aroles) are able to bring to

life the participation of the village communities. The remarkable

success of the project and the spirit which animates it, has

encouraged many other groups in India to launch similar ventures..

Just now a new team of medical mission sisters is reaching out

into the area bordering on Jamked. Dr. at ole told the sisters:

"Do not imitate the Jamked project, you can do better; be creative."

Provided success does not blind the groups involved to the fact

that they are still up against formidable obstacles, rooted in the

unjust structures of ownership of land and concentration of

political power in the hands of a minority, they are doing a

highly meaningful service to the people. Though they have to work

within the constraints of the prevailing structures, reflected in

the caste-system, they are instrumental in expanding the educational

processes in a direction which will make people more critically

aware of the still deep rooted elements of a highly inegalitarian

society. It might be worthwhile to discuss whether or not such a

comprehensive approach can and should evolve further into genuine

conscientization leading ultimately to the emancipation of the

masses.

3.

Food for Work

I

had the, opportunity to listen -to your first reports on

programming concrete projects. In all of these food for work

had an important place.

What is surprising about food for work programmes is that

some lock.upon them as a curse, others as a great blessing. When

visiting in Maharashtra, a massive food for work project, I was

much impressed by hundreds of men and women constructing

percolation tanks that would greatly increase the agricultural

production. A few critical questions, however, brought out a

..4/-

- 4 -

a number of serious drawbacks of the programme. Nutrition

education was totally- absent; more serious: the land below the

percolation tanks belonged to the richer farmers of the villages.

And an accident of lorries with grain having been diverted to the

market of a nearby township, still further darkened the picture.

As I wish to elicite discussion, on what the conditions for a good

Food for Work Programme are, I cite another case. Over thousand

men and women have been involved in a programme which lasted

several years. It was greatly effective in increasing agricultural

production in the area. A network of channels were dug which

would bring the water from the main canal into the fields of the

farmers: fields were levelled and bunded. All excellent on

first inspection. But there were non-intended effects. The

earning capacity of the farmers was increased permanently through

the labour of this army of workers. These, however, after

completion of the project were back where they were initially:

in poverty, unemployment and helplessness. The inequality gap

between them and the farmers had been widened as a result of the

project. This case demonstrated how linking of Food for Work and

agricultural development needs a good deal of political wisdom to

be really contributing towards genuine development. The question

as to what impact such programmes have on the social structures of

society cannot be ignored. I am sure that many of you have been

connected with such projects which really improved the productive

capacity and the income of the beneficiaries themselves. I too,

know many such projects.

A friend of mine visited' recently some region of Andhra Pradesh.

On his return he wrote to me: "I was shocked to see how priests

and sisters have become corrupt in handling development projects.

He was not referring explicitly to Food for Work Projects. But

the problem is common to all development work. If our preoccupation

is only in terms of efficiency, of effective programming etc.,

there will be a missing link. Development programmes, however

well conceived, do not automatically bear fruits of justice,

integrity and responsibility. It is strage that so many organisa

tions which go under a spiritual name pay so little attention to

this. I am Including the organisation to which I belong. We

expose a host of people to responsible work, supply them with lots

of material inputs, and expect them to be good and honest without

helping them to discover motives to be so. Exposed to a host of

pressures it is not easy to swim against the stream, especially

with the increasing shortage of food-stuffs and constantly rising

prices. Food For Work programmes are to a high degree vulnerable

and expose the persons handling them to the pressures mentioned,

in an atmosphere of wide-spread corruption and of 'let me get up'

philosophy.

4.

The Educational Dimension

The linking of nutrition, health and agriculture has the advantage

that all three sectors demand primary emphasis on educational

processes if they have to build up new people with new ways of

...5/-

- 5 -

feeling, thinking and acting. You know much more about the nature

and methods of extension education related to these three sectors

than I do. But the best extension education can still miss the

ultimate worthwhile goal of building a community, a horizontal

solidarity, of helping a new spirit of collaboration and sharing

to be born. Mere achievement motivation which results from

successful experience in 'keeping my child health, producing more

on my fields' risks to be infected with striving for egoistic

social advance, which is the root-cause of underdevelopment

understood in depth. Everywhere we see that the same processes

which push up some, keep others down.

The following happened in North India

*

Under the guidance of a

priest the Santals had transformed a jungle area into fertile fields.

They had built, with Food For Work an earthen dam in a valley close

to their settlement. The monsoon broke in. Heavy rains poured

down incessantly. Suddenly in the ‘middle of the night shouts

resounded: "The dam is bursting", men and women ran out of their

houses in the direction of the dam. They worked the whole night,

filling bags with sand to strengthen the dam. The priest was with

them and all got wet to their skin. In the morning the dam still

stood. They had made it together. "During this night the community

was born"', commented the priest in narrating the story. How can

such community experiences become educational processes within

programmes of nutrition, health and agriculture? This seems to be a

critical question if our long-term goal is the creation of a new

society, in which dignity and equality and participation is deeply

experienced within human organisations and institutions. It is

my personal conviction that any organised intervention risks

unconsciously to serve the interests of those who have control

over societal institutions, unless it is clearly guided by long-term

goals of a more just and more human society. Every intervention,

however small it may be, affects the process of change in society.

It either is supporting a process leading to increasing-inequality,

or it belongs to the counter-forces inspired by counter-values,

and which do have a relevance for a change towards greater social

justice.

You may remember the .passage from Solzhenitsyn's novel 'The Inner

Circle1.,., about the sheep producing more wool because of being

better fed. In explicit terms it means: mere extension education,

however Important it is, not accompanied by 'political education'

gained by people organising themselves, establishing their own

institutions, e.g., for credit, marketing, etc.,(reflooting on the

causes of their having little say in policy formulation of

political bodies at various levels), risks to support the existing

power structure. Social workers are easily 'used' by politicians.

And the greatest illusion would be to think that Nutrition

Programmes are neutral, having no political consequences.

Politicians may be interested in Nutrition Programmes (nationally

and internationally) for "political reasons"., which in plain

language means: for the purpose of "feeding" rather than for the

purpose of emancipation and liberation, which really would serve

the interests of the people.

pu-y Lf.-

4

WHO Chronicle, 31: 143-149 (1977)

KEEPINS FOOv SAFE FROM

HARMFUL GERA'S

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

47/1,(FirstHoor)St. Marks Road

BANGALORE-560 001

The health of people depends to a large extent on the

fbod they eat. Keeping food safe from harmful germs

and their toxic products is therefore an important

problem, which over the years has engaged the

attention of various WHO expert committees concerned

with different aspects of food hygiene. The latest

report of the WHO Expert Committee on microbiological

aspects of food hygiene, which met in Geneva in March

1976 (with the participation of FAO), has recently

been published-1 and it describes the microbiological

agents of food-borne disease and the microbiological

hazards in relation to foods. The article below, which

is adapted from the secotr part of the report, describes

*

th

Microbiological hazard;

handling and storage.*

etc., as well a;

""

'elated to food processing,

>n movements, tourism,

•

*

t

Centre^ them.

Hazards related to food -'reparation

The largest proportion of food-borne disease is

probably caused not by commercially processed foods but

by food prepared at home, in institutions, or in food

catering establishments. Food-processing plants were

implicated in 6% of food-borne disease outbreaks in the

USA during the period 1968-73 and in nearly 25% of

outbreaks in Denmark during 1954-63. The commonest

causes of disease resulting from food prepared in

kitchens of private homes or institutions in the USA

arc unexpected contamination of the raw food material

and faulty preparationtochniques. One study of disease

outbreaks that could be attributed to food processing

plants suggested that most of the outbreaks were due to

contaminated raw materials (for products not given a

terminal heat process) and to faulty applications of

processing and packaging techniques.

2

Common faults in the handling and processing of

food in homes, restaurants, and other food catering

establishments, which led to disease outbreaks, are

given in Table 1. In some cases several faults were

found without the possibility of identifying the

importance of each one. Several outbreaks of food

poisoning, usually caused by salmonellae, were found

to he due to the transfer of organisms from conta

minated raw food to cooked food by hands, utensils,

and unclean surfaces.

Table-1. Factors contributing to 493 outbreaks of disease

caused by foods processed in homes or in food catering

establishments3

Factor

No. of outbreaks

Inadequate refrigeration

Food preparation far in advance of serving

Infected persons and poor personal hygiene

Inadequate cooking or heating

Food kept “warm" at a wrong temperature

Contaminated raw materials in uncooked foods

Inadequate reheating

Cross-contamination

Inadequate cleaning of equipment

Other conditions

336

156

151

140

114

34

66

53

52

160

° Adapted from BRYAN, F.L. Microbiological food hazards

today-based on epidemiological information. Food technology,

23(9): 52(1974)

Hazards related to storage

Hazards related to the storage of food are determined

by various combinations of factors-length of storage, type

of food, methods of processing and preservation, types and

relative proportions of organisms present, PH, water activity,

and temperature.

1 VW Technical Report Series, Nj.593, 1976 (Microbiological

aspects of food hygiene). Report of a VJl-10 Expert Committee

with the participation of FAO), 103 pages, Price; Sw. fr. 9.-.

3

3

Temperature control is of major importance in

reducing hazards from pathogenic bacteria, limiting spoilage,

and keeping food safe. In countries where refrigeration

facilities are available perishable foods should be stored

at temperatures that inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria,

e.,

i.

less than 4°C (or alternatively above 50°C). The law

temperatures must be achieved quickly after processing in

order to obtain the greatest benefit from refrigeration.

Slot; cooling may allow heat-injured spores to recover and

subsequently to grow before the temperature reaches an

inhibiting level.

At low temperatures, particularly under chilled

storage, changes may occur in food usually as a result of

the growth of psychrophilic bacteria such as Pseudomonas,

Achromobacter, Flavobacterium, and Alcaligenes and certain

yeasts and moulds.

Hazards related to food habits

Food habits vary from one country to another and even

within a country, but these habits are subject to change. In

countries where environmental sanitary conditions are poor,

gastroenteric diseases are one of the most important causes of

morbidity and mortality. Food and water are important channels of

transmission of these diseases.

The following factors tend to increase food-borne

diseases:

(1) Intensive production of livestock and the use

of contaminated feeds.

(2) Consumption of raw or undercooked meat or poultry.

This increases the risk of parasitic diseases and bacterial

infections and intoxications, e.g., salmonellosis, toxoplasmosis,

human linguatulosis, Taenia saginata and T. solium infestations,

and trichinosis. Even in countries where meet is thoroughly

inspected to prevent transmission, mild infections of carcases can

still be missed. The habit of cooking large cuts of meats into

which heat cannot adequately penetrate may sometimes be

responsible for these infections.

(3) Consumption of raw milk, either from choice or for

economic reasons.

4

4

(4) Consumption of raw or undercooked fish. Infections

due to Vibrio parahaemolytlcus, biphyllobothrium latum or

other cestodes, trematodes, and nematodes may result.

(5) Consumption of wild animal meat. Out-breaks of

trichinosis have occurred through consumption of wild boar

and bear meat.

(6) Improper home canning of foods. In the USA

the majority of outbreaks of botulism occur as a result of

home canning of vegetables end fruits where adequate processing

has not been carried out.

(7) Preparation of ready-to-eat foods in bulk and

mass feeding, where under certain conditions normal habits of

food hygiene are relaxed.

(3) Consumption of traditional food delicacies. Utijak,

an Eskimo delicacy prepared by' keeping seal flippers soaking

in oil until rotten, has been responsible for whole families

dying from botulism.

Hazards related to population movements end travel

With improvements in the speed and safety of travel,

more and more people now visit other countries; in the case

of "package” tours, organized to attract tourists, a considerable

number of people are exposed to Environmental hazards which

they would not experience in their own countries or homes.

Outbreaks of food-borne disease cue to Staphylococcus

aureus, Clostridium perfringens, salmonellae, V. parahaemolytlcus

cholera and non-cholera international air travel. Strict control

of food hygiene in flight kitchens, as well as on board aircraft

is essential.

JJumerous outbreaks of enteric infection have been recorded

on passenger ships; several of these have been reported on

cruise ships. Replenishment of ships’ water supplies during

a voyage has always presented a particular hazard since many

opportunities exist for contamination of water between ship

and shore. An additional hazard is cross contamination of

drinking-water with bilge or waste water. Several outbreaks

of V. parahaemolytlcus gastroenteritis were reported on cruise

ships sailing from ports in the USA in 1975. In one of these

outbreaks V. parahaemolytlcus serotype OgjK^ was isolated

5

5

from sick passengers and seafood cocktail was implicated. It

was thought that the food was contaminated vdth polluted sea

water. In another investigation of the incidence of gastroente

ritis on a passenger ship, Escherichia coli 027 was. the’

predominant organism isolated from patients with diarrhoea.

In addition to the specific hazards of well-known

enteric infections and. intoxications, travellers and holidaymakers are exposed to other infections usually classed as

"travellers’ diarrhoea"; such infections are of limited

duration. There is evidence that travellers’ diarrhoea is

associated with strains of enterotoxigenic E. coli new to the

individual and acquired through the medium of food and water.

Amoebiasis and giardiasis may also be involved in tourists'

gastroenteritis originating from food and water.

Owing to the influx of large numbers of people to sites

of pilgrimages and refugee camps, the threat of cholera and

other enteric diseases in these places is very real. Camping

and Caravan sites, fairs, and festivals can also present

hazards of food-borne disease outbreaks if the sanitary arrange

ments are not satisfactory.

Hazards related to imnortec foods

Large quantities of foods for human consumption and for

feeding animals are transported from one country, or from one

cart of the world, to another. The exporting country may have

no knowledge of the ways in which their products are used in

importing countries, and foods that are considered safe in the

country of originmay provoke disease in the importing country

as a consequence of different food habits. The importing

country, on the other hand, often has insufficient knowledge

about the production and processing of the food, and public

health authorities are concerned about the unknown risks. This

has led to the setting up of control systems or requests for

guarantees on wholesomeness, absence of pathogens, etc., which

information many exporting countries are generally unable to

give. Import control based only on sampling and testing of lots

is often ineffective and has not been able to prevent several

outbreaks of disease due to imported foods in various countries.

6

6

Eliminating harmful germs

Eifferent processing methods, e.g., heat treatment,

refrigeration; etc., arc available for combating food-borne

disease agents such as bacteria, parasites, and viruses.

The effects of such treatment on these agents or on toxins

produced by them are summarized below.

Effect of heat processing

(1) ton-spore-forming bacteria. Officially approved

heat treatment of moist foods for the purpose of eliminating

non-spore-forming bacteria, notably salmonellae, ranges from

3.5 minutes at 61.1°C for liquid whole egg to 1 second at

132.2®C or over for ultra-high temperature treatment of milk.

Foods with low water activity or high fat content require more

intense heat treatment than foods with high water activity or

low fat content. Such treatment can he expected to effectively

eliminate salmonellae, staphylococci, pathogenic streptococci,

brucellae, etc. Studies of the heat resistance of V. parahaemolyticus have shown that this organism is killed as easily as

other non-spore-forming bacteria,

(2) Spore-forming bacteria. The heat resistance of

spores of C,botulinum type A has been the basis for calculating

minimum heat processes for low-acid canned food for half a

century. Spores of C. botulinum types B and F may have a

heat resistance approaching that of type A; spores of most

type E strains are destroyed at temperatures below 1OO°C

and strains C and D barely survive heating to 100°C. 7he

spores of type G seem to be as resistant as types C and. D.

The heat resistance of C. perfringens type A spores may

approach that of C. botulinum type A, which means that they are

not killed by normal cooking (boiling) of food. The resistance

of spores of non-heemolytic strains is generally higher than

that of B»haemolytic strains. Heat-shocked C. perfringens

spores, when ingested, germinate in the intestine. Later

sporulation of these vegetative forms gives a greater yield

of snores and therefore more toxin.

(3) Parasites. Trichina and several other parasites

are killed by exposure to a temperature of 53°C and all

food-borne parasites seem to be destroyed by boiling (1OO°C)

for a short time.

7

(4) Viruses. Oncogenic viruses in ice-cream mixes

were effectively destroyed by Stannard pasteurization

(63.3°C for 30 minutes or 79.4°C for 25 seconds). Pasteurization

of liquid whole egg at 60°C for 3.5 minutes resulted in a

million-fold or tenthousand-folcl decrease in poliovirus and

echoviruses, respectively. Studies of survival of poliovirus

and Coxsackie viruses during broiling of hamburgers showed

that 4 minutes at u71°C and 76.7°C respectively were required

for 90% reduction. For complete destruction of some viruses

it may be necessary to boil the food.

(5) Microbial toxins, Most fungal toxins, including

the aflatoxins, are not destroyed by boiling or ® autoclaving.

Staphylococcal enterotoxins are also very heat-resistant; more

than 9 minutes at 121.1°C may be required for 90% destruc tion.

Foiling readily destroys botulinal toxins as well as C.perfringens

toxin, but the latter is never or only rarely present in foods.

(6) Microwave heating. Microwave heating of food has

become widespread in recent years. Frequencies of 915 or 1450

MHz are most often used. Microwaves generate heat in foods and

it has been suggested that their effect is solely due to the

generated heat. There are indications of additional modes of

action when vegetative cells are killed by microwave. However,

microwaves do not effectively kill spores at temperatures

below 100°C.

Effects of irradiation

Resistance of food-borne pathogens to ionizing radiation

might be a problem in irradidation preservation of foods. Low

doses of irradiation have been suggested as a means of prolonging

the shelf-life of food and eliminating radiation-sensitive

disease agents such as salmonellae. Large doses (4J3 x 10^ Qy

(gray) 4.8 megarad) or more) have been recommended for

sterilizing canned foods.

(1) Non-spore-forming bacteria. Irradiation of food

with doses of up to 1 x 10^ Gy(l megarad) will effectively

eliminate bacteria such as salmonellae, staphylococci, vibrio,

and others.

(2) Spores. Spores of C. botulinum are among the most

radiation-resistant microbial forms. The dose required to

-3

destroy 90% of spores is a little more than 3 x 10 Gy

(0.3 megarad) for the most resistant strains of types £ and b

and more than 6 x 103 Gy (0.6 megarad) for proteolytic type

F. In the USA, 4.8 x 104 Gy (4.8 megarad) has become the

accepted sterilizing dose for food.

a

(3) Parasites, viruses, toxins. Parasites are rather

sensitive to irradiation. Larvae of Trichlnella spiralis

may survive as much as 1 x 104 Gy (1 megarad) but 1 x 102 Gy

(0.01 megarad) suffices to sterilize the female larvae and

thus interrupt the infection cycle. Viruses are quite resistant

but it is believed that a sterilizing dose (4.8 x 104 Gy or

4.8 megarad) will inactive viruses naturally present in food.

Toxins in food cannot be inactivated by irradiation.

Refrigeration:

(1) rbn-spore—forming bacteria. The growth of

salmonellae is arrested at temperatures below 5.2°C and above

44—47®C. ’ he th er they will actually grow at these temperature

extremes depends on other factors; low pH or water activity

narrows the range of growth. Staphylococci can grow at

temperatures between 6.7°C. and 45.4°C and enterotoxin

production can occur at temperatures ranging from 10°C to 46°C.

The lowest reported temperature permitting growth of

V. parahaemolyticus is 3°C and the riiaximum 44°C.

(2) Spore-forming bacteria. While the growth of

proteolytic strains of C. botulinum is arrested at temperatures

below 10°C it has repeatedly been confirmed that non-proteolytic

E and F strains grow and produce toxins at temperatures down

to 3.3°C. The minimum growth temperature for C. perfringens is

6.5°C but growth is slowed down considerably at temperatures ’

below 20°C. No clostridia have been found to multiply at

temperatures, higher than 50°C. Bacillus cereus can multiply

in the temperature range 7-49°C. Pathogenic bacteria may

remain viable, hut without growth, for a long time in refrigera

ted foods.

(3) Parasites, viruses, toxins. These agents co not

multiply in foot’s but may remain active indefinitely at

refrigeration temperatures.

(4) Moulds. The majority of fungal toxins may be pro

duced in food kept at temperatures between 4°C and 40°C, but

fungi that produce alimentary toxic aleukia can grow and

produce toxin in the range of —2°C to - 10®C with an optimum

temperature for toxin production of 1,5-4°C.

9

Freezing

(1) Nbn-spore-forming bacteria. Freezing not only

results in arrest of growth but also in destruction of some

cells. However, like salmonellae and staphylococci,

V. parahaemolyticus shows better survival at low freezing

temperatures. At - 3O°C, they may survive for longer than

4 months.

(2) Spore-forming bacteria. While the vegetative cells

of bacilli and Clostridia are not much more resistant to

freezing than non-spore-forming organisms, their spores are

highly resistant.

(3) Parasites. Protozoa are generally destroyed by

freezing. Trichinella spiralis, Anisakis, and Toxoplasma

cysts Can be killed by exposure to freezing temperatures for

long enough periods of time. The same is true for intermediate

stages of Taenia ano' Diphyllobothrium latum in fish.

(4) Viruses, toxins, moulds.

very resistant to freezing.

These agents are generally

Water activity, nil, and other factors

Different types of microorganism have characteristic

ranges of growth with respect to the water activity in foods.

The latter is reduced by increasing the concentration of solutes

which can be accomplished by drying and/or the .addition of

agents such as sodium chloride, sucrose, glucose, glycerol,

and propylene glycol. The type of agent used influences the

response of microorganisms to variations in water activity.

Values that are inhibitory to the growth of microorganisms

do hot necessarily destroy them or viruses or toxins. However,

trichina and possibly other parasites die in heavily salted

foods. Minimum and optimum levels of water activity that favour

the growth of different bacteria and moulds may be found in the

report on which this article is based.

The effect of the acidity (or pH) of food on the

growth of different organisms, etc., may be summarized as

follows s

(1) bion-spore-forming bacteria. Staphylococci can

grow under aerobic conditions in food within the pH range

4.3-3,0 or higher, but enterotoxin production (with the possible

exception of type C enterotoxin) does not occur at pH values

below 4.5. The limiting acidity for anaerobic enterotoxin

production is pH 5.3,

10

Salmonellae can grow in the pH range 4.1-9.0 and V.parahaemolyticus in the range pH 4.3-11.0. Values below pH 4 are lethal to

most vegetative cells of pathogenic food-borne bacteria. The

lethal effect and the growth inhibitory effect depend on

temperature, pH, and on the acids used.