RF_NGO_16_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_NGO_16_SUDHA

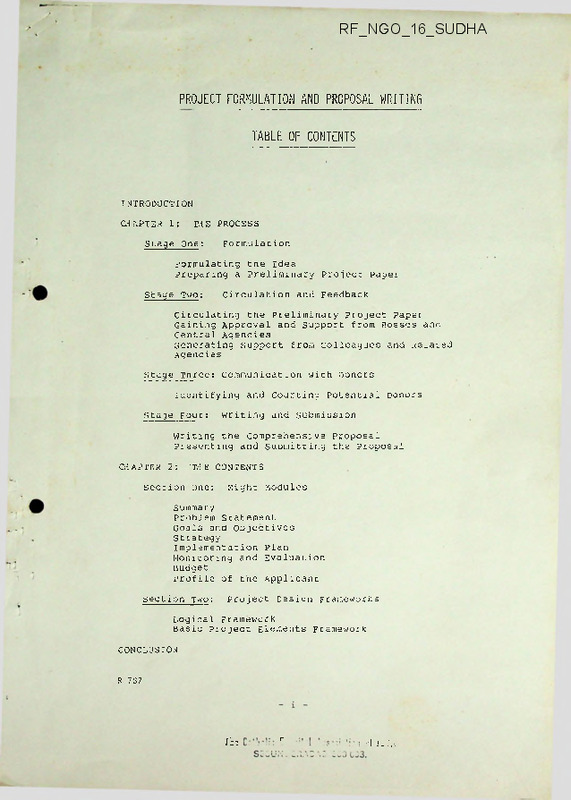

PROJECT FORMULATION AND PROPOSAL WRITING

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1:

THE PROCESS

Stage One:

Formulation

Formulating the idea

Preparing a Preliminary project Paper

Stage two;

Circulation and Feedback

Circulating the preliminary project Paper

Gaining Approval and Support from Bosses and

Central Agencies

Generating Support from Colleagues and Related

Agencies

Stage Three: communication with Donors

Identifying and Courting Potential Donors

Stage Four:

Writing and Submission

Writing the comprehensive Proposal

Presenting and submitting the Proposal

CHAPTER 2:

THE CONTENTS

section one:

Eight Modules

Summary

Problem Statement

Goals and objectives

Strategy

Implementation Plan

Monitoring and Evaluation

Budget

Profile of the Applicant

Section two:

project Design Frameworks

Logical Framework

Basic project Elements Framework,

CONCLUSION

R 787

Th:

r.

I cl u.’j.

INTRODUCTION

All of us involved in developing and managing projects

have nad to learn sooner or later that money does not

necessarily flow just because we have a gppd idea.

Although numerous organizations are in the business of

granting or lending money for development, these agencies

need to be provided with well written convincing documents

presenting our case. They require proposals that show

that what we have in mind is a priority, is feasible, is

cost effective, fits with national plans, does not

duplicate anything already being done, and so forth.

Project managers are usually good at identifying

problems and developing relevant solutions and new

interventions, but they often lack the-time and the skills

to present these ideas in the form required by the

potential financiers and partners.

This is true of many of the managers in the Health

Learning Materials (4LM) Network where good will and good

ideas abound but money does not. The HLM clearinghouse at

,-l.iO has attempted to provide advice and assistance,

wnerever possiole. But it is essential that national HLM

projects become more independent and self-reliant in

writing proposals and approaching donors. Towards this

end, tne a LM clearinghouse has produced these guidelines

for project formulation and proposal writing.

Although developed specifically for HLM Network

Managers, this document can also serve other middle and

senior level nealth managers in government and

non-governmental agencies in the Third World. it draws on

materials from international and non-governmental

organizations and, in particular, on the experience of the

African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF), a

Kenya-based regional non-governmental organization

involved in designing, implementing and evaluating a wide

variety of nealth development projects.

The guidelines deal with the process of formulating

ideas, soliciting feedback, developing support, writing

and submitting project proposals, as well as with the

contents of proposals.

Chapter One takes you through the main stages that

make up the process of project formulation and proposal

writing. For each of the four stages that have been

identified, there is a description of what usually happens

and a few points on how to proceed and wnat to watch out

for.

In its first section, chapter two presents eight

modules tnat can be used to produce preliminary project

papers and full project proposals, a second section

describes techniques for charting essential project

information in summary tables.

Process and contents are inextricably linked in

project formulation and proposal writing. By covering

both, we hope that these guidelines will point the way and

help you get over all the hurdles you will encounter as

you formulate your idea and produce a proposal that

attracts the support and resources you need.

CHAPTER 1:

Stage One:

THE PROCESS

Formulation

*

Formulating the .Idea.

*

Preparing a preliminary project Paper.

The initial process of formulating a project idea

varies enormously, depending on the temperament, training

and opportunities of the concerr’d individual, it. spans

tne period in time from becoming aware of a particular

problem to the moment when you have settled on a

particular strategy to approach tnat problem.

Whether you have arrived by leaps and bounds or step

by step is not important. Nor does it matter whether or

not the idea has come to you in what planners would regard

as a logical sequence. No matter how you got there,

unless you are independently wealthy and run your own

one-man or one-woman organization, you must now get ready

to present your project idea to those whose assistance,

support, approval and money you need for its realization.

You have recognized a problem, an unmet need, a

condition that requires a change in the present course of

action or inaction, you have thought of a solution. It

is now time to sit down and put your analysis and your

propositions on paper, and to critically review your own

ideas.

It is both unnecessary and unwise to start by

preparing a comprehensive detailed project proposal.

It

is unnecessary because the bare bones of your project idea

are sufficient for a first review by your colleagues, your

bosses and by potential donors, it is unwise because

writing a full proposal is a great deal of work which may

turn qut to be a waste of time if your basic idea is not

acceptable to your organization or to the donors.

Produce a preliminary project paper of no more than

five pages. The paper should cover a statement of the

need, the goals and objectives, your proposed strategy and

an indication of the type, size and value of resources

required. Writing the paper will provide a mechanism for:

thinking systematically about your project,

reviewing and clarifying the connection between

tne need, goals and strategy;

identifying 'gaps and inconsistencies you may not

have noticed before;

considering the scope of the proposed

intervention and the feasibility of implementing

it under the prevailing economic conditions and

within the limitations of your organization;

making a rough calculation of the resources

required from external sources;

developing a solid basis for soliciting feedback

and development support among peers and decision

makers within your own institution, from other

relevant organizations and from potential donor

agencies.

Stage two;

Circulation and Feedback

Circulating the Preliminary project Paper.

Gaining Approval and Support from Bosses and

Central Agencies.

Generating support and Cooperation from

Colleagues and Related Agencies.

You have completed your preliminary project paper.

The purpose of doing this has been to clarify your own

thinking and to produce a brief document describing the

essential elements of the project., you can now use this

document as a basis for discussion and as a tool of

persuasion.

At this stage, you need feedback from your superiors

and your colleagues about the merit of your idea. Do they

agree with your needs assessment; problem formulation;

tne objectives you have set and the strategy you have

selected? What about feasibility? Do they consider the

technical solution as appropriate and implementable?

What

about the projected resource requirements - is the

proposed solution affordable?

Circulate your paper to a well selected group

including possible adversaries. Observe carefully whether

your ideas are understood in the way you meant them'. How

well have you communicated your analysis, yotir visions?

Be sure to consider tne process of obtaining feedback

not just in technical terms. The reactions you receive

will help you review not only the technical contents of

the proposal, but equally importantly, assess the

feasibility of its adoption in terras of organizational and

political support.

Although rationality and logic are stressed in guiding

you through the process of formulating your ideas and

writing proposals, we all know that these standards of

rationality often do not apply in the real world.

Projects may be perfectly logical and needs assessments

objective and valid. Yet, a project does not get adopted

oecause it does not coincide with the interests and

values of an important decision maker in your

organization. The need nay be considered a priority

within your organization or sector but the central

treasury, dealing with the allocation of scarce resources

between different sectors, may not agree with your

assessment, your objectives and strategy may be perceived

to be competing or conflicting with someone else's pet

project and rejected for this reason.

Discussions of the preliminary proposal can be

skilfully used co develop interest and support for the

project idea. This is the time to lobby, to bargain and

to form coalitions that will assure not only the adoption

of the proposal out also develop solid support for its

successful implementation. Consider all the forces that

affect your project and see how you can acquire allies at

ail levels.

Stage Tnree:

Communication with Donors

Identifying and Counting Potential Donors.

Donors have their own priorities and values.

This is

not only true of the major donors whose operations are

largely determined by macro political and economic

considerations. it is equally true of most other donors .

wno usually have geographical and sector priorities as

well as preferred strategies within sectors, if one were

to caricature the donor situation, one might say that

Africa is 'in', community participation is 'in', the

district is 'in', hospitals are 'out', and so forth.

These 'ins' and 'outs' tend to change every few years,

to

be sure, they are usually based on careful considerations

of needs and experiences in the field. in any case, it is

important to be well informed on what current trends in

donor thinking are and to use appropriate terminology as a

tool to market the project proposal, without compromising

vital principles of your basic idea.

You.should develop and keep up-to-date an inventory

that contains profiles of all potential donors, including

the following information:

- geographical priorities

- sector priorities

- size of projects funded (range)

- maximum project duration

- preferred health strategies

- proposal format

- channels for project submission

- reporting and evaluation requirements

To obtain this information, contact as many embassies

and international delegations as possible in your capital

city and ask for a list ,of development and aid agencies in

tneir country or region. if they cannot provide it

tnemselves, they will give you the name and address of an

institution in their country that can help. There are

also directories of international foundations issued

periodically by different organizations, such as

Organization for Economic cooperation and Development

(OECD) and the united Nations Development Programme

(UNDP). See whether you can find these through the office

of the UNDP representative, or in the library of your

national development institute.

Finally, there are two particular concerns of donors

that you will need to carefully consider and address in

your discussions and negotiations.

Firstly, donors are

inevitably concerned with the economic feasibility and

institutional capability for continuing the project after

external funding ceases. They wish to see project

strategies that explicitly address the development of

institutions and that promote self-reliance.

Secondly, donors understandably aim- to fund activities

tnat will produce tangible results. They usually insist

on identifying ways for measuring the success or failure

of the project, they are helping to finance. The

development of systems for monitoring and evaluation are,

therefore, of special importance.

Stage Four:

Writing and Submission

Writing the Comprehensive Proposal.

Presenting and Submitting the proposal.

in writing the final proposal you will carefully

scrutinize all the feedback information you have

received. It will not be possible to please everyone and

to incorporate all comments, if you do, chances are that

your proposal will become confused and inconsistent. When

you make changes in one of the key sections of the

proposal, be sure to review whether the logical link

between objectives, strategies and inputs remains intact

or whether other sections also med to be altered.

The preliminary project paper is usually produced with

scanty information. completeness and validity of

information are important when you write the full proposal

and will probaoly require additional work.

The interactions you have had with colleagues, bosses

and donors have helped you define the strategic space

within which you must now develop your full proposal.

Whereas at the idea stage, organizational and political

realities may nave been remote, you will need to take full

account of these in producing the final document.

Once you have completed the proposal, you usually need

to submit it through the formal channels. This will

involve central ministries, such as the Ministry of

Economic Planning, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs or the Office of the President. in

some unfortunate situations, it involves not just one but

all of these, proposals to non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) do not always have to follow this route. dowever,

they often require a supporting letter- from the head of

your institution.

To minimize delays, it helps to draft

such a letter for the signature of the relevant person

rather than wait for it to be done by usually very busy

top officials.

Going through official channels need not prevent you

from informally submitting an advance copy to the donor,

provided it has been approved within your own organization.

Cost Sharing

Do not necessarily expect to find a single donor who

will finance your entire project. There are donors who

are willing to provide seed money for operational research

to further investigate problems and to carry out detailed

project design work-. Many donors favour co-financing

arrangements whereby two or more donors participate in

funding a project. Keep donors informed of your

approaches to other agencies, if you have convinced some

donor agencies of the value of your undertaking, they may

even help identify and approach additional donors.

10

Follow-up witn Agencies and Rewriting

Once you have submitted the documents, perseverance

becomes the name of the game, project submissions may get

stuck at each point on the way to the donor, you will

need to checK regularly whether the proposal is moving in

tne right direction. Be prepared to spend time and effort

to see that the proposal arrives at its destination.

Technical officers often consider their labours over, once

a proposal has been completed and accepted by their

superiors. it is difficult to overemphasize the

importance of making an effort to see that the proposal

arrives in the right hands and to show yourself willing to

rewrite and re-edit sections, if necessary and appropriate.

Alterations in propsals at tne request of central agencies

and donors are not unusual.

in fact, donors' requests for

revisions are a positive sign; at least they have not

rejected the proposal.

Although you need to ascertain that the proposal

remains technically sound and organizationally feasible,

your work has not oeen completed until a mutually

satisfactory version of the proposal has found its way to

the final decision makers.

CHAPTER 2:

THE CONTENTS

Section one;

Eight Modules

Section two:

Project Design Frameworks

Information requirements and formats for proposals

vary a great deal from donor to donor, some donor

agencies insist that applicants adhere to their format,

others simply offer guidelines to assist the applicant and

to ensure that major points are adequately covered.

It is noteworthy and comforting, however, that the

same key sections tend to appear in almost all standard

formats of the major donors, smaller donors frequently

leave the questions of tne format to the applicant,

provided that specified essential information is included.

You will find more variation in the words used to

denote the most important components. For example, what

some donors refer to as objective is called purpose by

others. Donors are usually after one and the same thing

wnen they ask you about the approach of your project, the

method of intervention, the technical plan or the project

strategy.

13

Keep in mind that what these sections contain is more

important than how they are named. Your proposal needs to

be internally consistent arid easily comprehensible to a

wide spectrum of reviewers. Be sure that the logic of

your presentation is clear in your own mind and well

understood by those you have asked for comments and

feedback in the first round.

.in the next section, you will find eight modules which

allow you to present all essential information about your

proposed project. These modules can be used for both the

preliminary project paper and the full project proposal.

The eight modules together will produce a

comprehensive project proposal. If your donor requires

less detail, you may want to omit some modules. For the

preliminary project paper, you need only three modules (2,

3 and 4) and one section of a fourth module (5), covering

the problem statement, goals and objectives, strategy and

resource inputs.

Each module begins with the key question to be

addressed in the relevant chapter of .your proposal,

followed by definitions and a discussion of what the

chapter should contain. Examples and questions are added

wnere required to illustrate these points.

Section two of this chapter deals with project design

frameworks for presenting all essential project

information in tables.

SECTION ONE:

EIGHT MODULES FOR PROJECT PROPOSAL

WRITING

Module 1

SUMMARY

What is It All About?

Module 2

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Wnere Are We now?

Background

Needs Analysis

Module 3

GOALS & OBJECTIVES

Where

Goals

Objectives

Module 4

STRATEGY

Which Route Will We Take?

Components

Assumptions

Methods

Outputs

Feasibility

Module 5

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

'How Will We Travel There?

Resource inputs

Workplan

Organization

Module 6

MONITORING AND

EVALUATION

How Will We Know When

We Arrive?

Monitoring

Evaluation

Module 7

BUDGET

How Much Will It Cost?

Capital Cost

Recurrent Cost

And Who Are We?

Organizat ion

Record of

Achievements

Module b

ANNEX

PROFILE OF THE

APPLICANT

do

We Want to Go?

Module 1;

Summary

What is It All About?

The summary is perhaps the most critical section of

your proposal,

you may wonder why it is so important to

write a summary. Remember that decision makers are very

busy people. In addition to attending many meetings, they

review large numbers of documents and propositions every

day. They often do not have the time to carefully read an.

entire document. Only a limited number of the proposals

that come across their desks can be considered.

you need to provide them with a short and concise, but

interesting summary of your project. That summary must

convince the decision makers that your project is relevant

to their particular concerns and to the needs of the

country, and that it is well thought out.

Although short,

it must cover the essential points of the full proposal.

Be sure that you state the objectives and the overall

strategy of the project clearly and succinctly. Explain

how the project will solve or significantly contribute to

the solution of an urgent problem, or to addressing an

important unmet need. Outline the shortcomings of the

preent situation and then put forward a picture of the

future reflecting the changes that will result from the

proposed project interventions.

16

The total project cost is an essential part of the

summary. it allows tne decision maker to relate costs to

anticipated outcomes and to ass'ess the economic

feasioility of sustaining the project activities in thelonger term.

Although in the proposal the summary comes first, this

section should be written after you have completed all the

others.

Module 2;

Problem Statement

Background

Needs Assessment

Where Are We Now?

This part of the proposal should cover the general

background as well as an analysis of the need to be

addressed and alleviated by the project interventions.

The background section should be short and confined to

aspects of the general situation that are relevant to the

problem and to the interventions you are about to

propose. Explain how you (your organization) came to be

involved in identifying and addressing the situation.

This should be followed by your analysis of the unmet

need, diagnosing and further defining the nature of the

problem to be addressed, you will explain the importance

of the problem, commenting on its magnitude, its relevance

to the policies and priorities of your organization and

your government and its importance to the delivery of

effective and efficient health services, as you present

your needs analysis, keep in mind that the objectives and

strategies, which you will put forward in subsequent

sections, need to be clearly traceable to this part of the

proposal.

Tne following is the first paragraph of a problem

statement introducing a proposal for the rehabilitation of

referral nealth facilities and services. it illustrates

how to use the background section to set the scene for

discussing specific needs and for proposing a strategy to

address the situation.

"As a result of the political and economic

disturbances of the 1970s, the national health

referral system has deteriorated to the point that it

no longer provides adequate backup support for the

delivery of basic health care services. Minimum

repair of facilities would include restoration of

electricity, water, sanitation, basic equipment for

primary health care, and limited inpatient and staff

housing. in addition, health facilities have

continued to decline because of insufficient funds for

maintenance, and purchase of essential equipment and

supplies for basic referral functions. An important

factor in the deterioration of physical plant and

equipment has been the attrition of skilled technical

staff who are required to maintain, operate and

administer the health facilities. An additional

factor has been the inadequate level of support for

recurrent operating costs".

20

Module 3;

Goals and objectives

Goals

Objectives

Where po We Want To Go?

Goals are broad statements of what is ultimately to be

accomplished. Objectives are more specific aims which the

project is to achieve with its own resources and

activities and within the time frame specified in your

proposal.

Statements of goals and objectives form the basis for

the consideration of different strategies for their

attainment. Be sure that your statement explains the

purpose of the activities to be performed and establishes

a logical link between the problem stated in the preceding

section and the strategy you are proposing in the next

section.

Because most of the problems we try to address are

complex, you will find that there is a hierarchy of goals

and objectives pertaining to your project. This can be

confusing. Concentrate on the status you want to achieve

oy the end of the project as a result of your project

interventions (called EOPS = End of project Status by some

donors),

your project objective is a statement of the

EOPS you are striving for. It will provide a standard

against which to assess the project's achievements.

22

Some Questions

What has led to the identification of this

problem and to the decision to develop a project

to address it?

What is the general situation and how is the

problem developing? Will it grow rapidly, if

unchecked?

Wnat has been done so far to address the problem

and with what effect?

Wnat has been your (your organization's)

involvement?

Wave there been any evaluations of previous

activities and what have been the findings?

What evidence is there of both need and demand

for a workable solution?

bow is addressing this need relevant to the •

nation's stated priorities?

Tlie Catholic Hospital Association ol India

............ '’.ccaRAO-500 003.

Your project goal is the impact on the bigger picture

in health manpower development, in the provision of health

services or in improving the health status of people, to

which your project should lead or contribute.

An example of a goal statement is 'control and

reduction of the incidence of malaria in Eastern

Africa' with the project objective 'to assist

participating governments in monitoring the

sensitivity of falciparum malaria to current and

candidate curative and suppressive drugs'.

Another project goal may be 'orientation of health

care towards the most prevalent health needs in the

population' with tne project objectives 'to broaden

and improve the existing health information system'

and 'to produce population-based health information

through sampling in selected pilot areas'.

Some Questions

What is the overall goal of the sector or

programme which your project is part of?

-

What are the objectives to be achieved within

your project?

At the eno of the project period, where do you

expect to be?

23

Module 4;

Strategy

Components

Assumptions

Methods

Outputs

Feasibility

Wnich Route Will We Take?

Project strategy refers to the design for a set of

interventions that will meet youi objectives and

contribute towards attainment of the larger developmental

goal. Tne underlying assumption of a strategy is that its

successful implementation will eliminate, reduce or

control the stated problem and that it can be implemented

witnin the time frame of the project and with the

financial and organizational resources available to the

project, including those resources requested from the

donor. Tne project strategy is the core of your project

design.

A strategy may consist of a single intervention or a

number of simultaneous or sequential interventions, it is

useful to examine ano descrioe your strategy both as a

whole and by means of its components. For example, the

strategy for a national continuing education programme

will comprise a large set of interventions, including

reorientation and training of trainers and facilitators;

refresher courses and learning surveys for rural health

workers; distance teaching; development and production

of learning materials; library development; and the

development of a system of supportive supervision.

A number of assumptions are underlying your strategy

for continuing education, for example:

'if health workers

are better trained they will do a better job and, thus,

provide better care to the people'; and ‘continuing

education provides a vehicle for more and better contact

Between different levels in the health system'.

Explain what approach, what methods will be employed.

The next paragraph- is an excerpt from a proposal,

illustrating how to present your approach.

"We will offer assistance and training in developing

country-specific Health Learning Materials (3LM)

production strategies along the following lines;

identification of priority needs for materials,

and of potential authors and potential

readership;

development of the materials through workshops,

editing and pre-testing to produce a relevant,

usable draft of any book;

conducting a workshop with potential teachers,

trainers, specialists and other interested

parties to ensure the correctness and

acceptability of the draft;

re-editing;

artwork;

typesetting;

printing;

paste-up and

distribution.

Throughout this process, research, testing and

evaluation of all aspects of need, relevance,

usability, design and layout for different readerships

and purposes should be carried out'.

26

Try to describe the outputs resulting directly from

each set of planned activities, outputs are those

concrete and tangible products that are needed to achieve

the project objective and that will happen as a result of

specific activities, in the health learning materials

network, your outputs will be the establishment of

institutional units, e.g., a fully staffed and equipped

HLM unit; a number of trained staff; and, of course,

books and other teaching and learning materials. in an

immunization programme, your outputs will be vaccinated

children and mothers; in a rehabilitation programme,

outputs will include adequate staffing to allow full

functioning of the facility, management systems developed

and established to support and supervise activities, and

renovated buildings.

You will also need to comment on the feasibility of

your intervention strategy in technical, economic,

organizational and socio-cultural terms. For instance,

can your organization establish and maintain a printing

unit for tiLM? Will your organization allocate the funds

required for the operation of the unit after external

funding expires? What are the constraints likely to be

encountered?

In order to arrive at a project strategy, a number of

options are usually considered and examined with regard to

tneir cost effectiveness and feasibility. Briefly outline

tne main options you have considered and explain wny you

have selected your proposed strategy.

some Questions

What are the key elements/components of your,

strategy and what are the premises on which

these are based?

wnat are the methods used in this approach?

What are the expected outputs/results of each of

these components?

is the technology proposed in your strategy

available and appropriate for the project area?

Is there an existing infrastructure/organization

to which the project can be linked or does one

need to be established?

Will the implementing organization absorb the

additional recurrent costs implied by this

activity?

Can the implementing organization continue

project activities and sustain the benefits

beyond the expiration of external funds?

Are there any political or bureaucratic

obstacles to the adoption and/or successful

implementation of this project?

28

Module 5:

implementation plan

Resource inputs

Workplan

Organization

■low 'Will We Travel There?

Tnis is a core section of the proposal, describing

wnat is actually going to be done, saving decided where

you want to go and what route to cake, you are now

explaining the details of the journey.

Begin by specifying all the inputs required in terms

of manpower, facilities, equipment, supplies and operating

costs.

Include all inputs, not only those you are

requesting to be funded by an external donor agency. Also

descrioe what resources are already available and where

tney will come from. For example, your organization may

provide office space tnat you already have, vehicles that

nave oeen provided by other donors, and management support.

Next, you need to present a workplan outlining

activities, targets and schedules. in a large project,

you may want to divide your workplan into several specific

project components. These can also be referred to as

responsibility centres when different staff members head

these components.

- 29 -

y

Tne following taele is an example of a workplan,

containing the essential elements that permit easy review

of acnieveraents and constraints.

Output

Timing

Activity

Target

(By Component)

Critical

Assumptions

Indicator of

Achievement

Component a

Activity Al

Activity A2

Activity a3

Component B

Activity Bl

Activity b2

Page 32 shows an example of using this type of

workplan for a national health planning programme.

Another possioility for charting activities and their

timing is the Gantt chart, as illustrated below.

Activities

Jan

Activity 1

XXX

Activity 2

XXX

Activity 3

Feb

Mar

Apr

XXX

XXX

XXX

XXX

May

XXX

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

yet another option is a time table in the following

format:

1987

FEB

JAN

Planning

Planning

AUG

JUL

MAR

APR

MAY

JUN

Writers

Operators

Develop

Production

Course

Course

Software

Assistance

Package

Kenya

DEC

SEP

—

OCT

NOV

Editors

Distribute

Operators

Manuals

Computer

Production

Course

Software

Course

Testing

Course

Assistance

Consulting

Consulting

Tanzania

Package

Under timing, note whether this is a continuous,

periodic or time-specific activity, if periodic, indicate

frequency, if time-specific, indicate estimated date of

start and completion, under target, indicate what will be

tne direct result or output of the activity, if

Be sure that each result of output specified

successful.

can be related to an objective stated in the goals and

objectives section. under critical assumptions, state

essential conditions that need to be present for the

activity to take place and the target to be achieved.

Under indicator of achievement, describe the concrete

evidence or source of information required to demonstrate

that the activity has been completed and to indicate to

what extent its target has been achieved.

Tne workplan need not be overly detailed.

Refer to

the key activities and indicate by project quarter when

you expect the activity to start and to terminate.

32

Health Planning Programme

Workplan 1986 (Excerpt)

No.

ACTIVITY

____________ Title

TIMING

__________

OBJECTIVE/

TARGET

CRITICAL

ASSUMPTIONS

INDICATOR OF

ACHIEVEMENT

4.

HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEMS (HIS)

4.1

Produce the Health

Information

Quarterly for

national distrib

ution.

April

July

October

January

1987

To encourage

exchange of

information

activities,

etc. in

Uganda.

Articles sub

Quarterly

mitted ,

distributed

adequate

on time..

editorial

resources,

printing

materials etc.

4.2

Continuous

monitoring of the

Health Information

Systems in two

districts.

April

until

August

To assess

the approp

riateness of

the system.

Field work

begun in

March 1986.

No restric

tions on

travel.

Final Report

on system

with recommen

dation for its

alteration,

adoption or

otherwise.

4.3

Organize

workshop on

Health Information

Systems

August

for

three

days

To finalise

revision of

Health

Information

Systems.

Field trials

complete and

report pre

pared .

Proceedings.

4.4

Organize two

refresher courses

on Health

Information

Systems

November

January

(three

days)

To introduce

finalized

system to

two

districts.

Revised

Course

system

report.

accepted and

forms reviewed

and printed.

4.5

Depending on 4.3

the continuation

of the modified

system in two or

more districts.

September To collect

reliable

data on

morbidity,

mortality

and health

activity

from rep

resentative

districts.

33

An agreed

system is

confirmed;

necessary

modifications

introduced,

funds avail

able. No

restrictions

on travel.

Regular

statistical

output from

the system

on a national

level.

A very important ingredient in the success of a

project is the organizational framework within which

implementation is to take place, a description of the

project organization should be provided in this section.

This may include an organization chart.

Comment on

important linkages between the project and other

organizational units and external organizations. Lines of

authority and of communication should be clarified in this

section. Discuss organizational procedures for project

guidance and control, and for reporting activities and

expenditures.

Some Questions

What resources are required for the project to

function?

Which of these are already in place and can be

used by the project?

What are the activities to be carried out?

What is the timing of these activities?

What are the intended results of these

activities?

What are the major targets and milestones?

What are the conditions that must be present for

activities to be undertaken?

low can implementation of activities and

achievement of targets be verified?

Who will be in charge of the project?

What staff will be assigned and/or recruited?

To which department/division will it be

responsible?

low will it link up with other relevant

departments and organizations?

What reports will be made?

,iow often?

To whom?

What are the communications channels?

Will there be a steering or advisory committee

to provide direction and advice?

What will be its membership?

reference?

35

its terms of

Module 6;

Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring

Evaluation

riow Will We Know When We Arrive?

Surprisingly often, systems to provide information

for management and for evaluation are not adequately set

up at the beginning of a project. At project midpoint,

when donors usually ask to evaluate achievements and

project managers start to think about applying for a

follow-on grant, panic sets in as it becomes clear that no

baseline data is available and information has not been

systematically collected to allow a clear assessment of a

project's achievements against its plans.

To avoid such situations and to assure continuous

review of tne effectiveness of your project strategy, it

is important to develop indicators of achievement and to

set up a system for monitoring and evaluation at the

design stage. Roles and responsibilities in this area

need to be clearly assigned. Be sure to emphasize the

learning objectives of these functions and to develop a

system whicn assures broad participation.

Monitoring refers to the process of systematically

reviewing progress against planned activities and

targets. Evaluation encompasses a more comprehensive

review and assessment not only of project results, but

also of the initial assumptions underlying the project

design, including the relevance of the problem statement;

the relationship between the problem and the established

objectives; between objectives and strategy; between

strategy and implementation;

and between implementation

and outcome.

Monitoring is usually done by the project manager on

the basis of reports, field visits and regular meetings of

the project team. The comprehensive workplans described

in the previous section are an important monitoring tool.

Evaluations are commonly scheduled in the middle and

towards the end of the project period.

Many donors insist

on external evaluations using outside consultants, but the

best results are often achieved when external consultants

and project implementers together make up the evaluation

team. In the long run, evaluation will involve

measurement of the impact of the project interventions on

the situation prevailing at the outset. An example is the

impact of health learning materials on the attitudes and

practices of health workers.

Some Questions

What data will be routinely collected?

What indicators are you establishing for

various targets?

Who will monitor and analyse project

information and how often?

How will evaluations be scheduled and who will

participate?

38

Module 7:

Budget

Capital Costs

Recurrent costs

• -low Much Will It Cost?

in the project budget, you will systematically

enumerate the anticipated costs of planned inputs and

activities. Although estimates must be realistic, keep in

mind that a budget is a forecast rather than a definitive

statement of costs and prices;

Most organizations differentiate between capital

costs which occur only once during the life of a project,

and operating or recurrent costs which recur regularly.

Ah important characteristic of recurrent costs is that

they usually continue beyond the project period and after

external funding expires. Donors are generally wary of

financing recurrent costs unless these are projected to

drop substantially once a programme has been developed and

estaolished.

It is important to keep good notes stating tne

assumptions underlying your calculations. This is

particularly true for budget items which constitute

activities, such as workshops or evaluations. Although

shown as one amount, the cost of a workshop is composed of

several different types of expenditures, such as travel,

per diem, honoraria.

39

However, most line items in a budget refer to inputs,

sucn as commodities (computers, cars) and supplies

(stationery). Personnel costs are best broken down into

individual positions and their salaries and emoluments,

ratner than presented as a global figure.

Budgets should include a contingency for unforeseen

events and expenditures. Provision also needs to be made

for inflation.

Donor requirements vary widely with regard to the

currency in which the budget is to be presented: some

insist on dollar budgets and others on local currency

budgets. yet others require that your budget estimates be

presented in two columns, one for'local currency (LX) and

one for foreign currency (FX). you will need to consult

tne guidelines of your particular donors to be sure that

you present the budget in the required form.

It is quite possible that you will not be able to

find one donor to fund your entire project.

instead of

writing several proposals to cover different aspects of

tne same project, you may simply divide up the costs

between different donors. in this case, you can present a

comprehensive budget wnich indicates the amount of money

you are requesting from different donors as well as your

own organization's contribution. If your contributions

are in kind, e.g. premises, equipment, you should point

this out in the budget notes.

Regardless of specific donor requirements, budget

preparation can be quite easy if you use a comprehensive

checklist such as the one below, to guide you.

Budget Check List

Capital Expenditure

2.

Construction

Office buildings;

staff housing;

training schools;

health units; other

construction.

Commodities

Equipment;

vehicles.

furniture;

Recurrent Expenditure

3.

Personnel

Technical staff;

support staff;

consultants; casual

labour.

4.

Training

Fellowships; study

travel; workshops;

refresher courses;

correspondence

courses; extension

courses; other courses.

5.

Travel Costs

Train/bus/air fares;

per diem, etc. for

personnel and training.

6.

Supplies

Medical supplies;

training supplies;

vehicles; office

supplies; printing and

photocopying.

7.

Maintenance

Equipment;

buildings.

8.

Vehicle Running

and Maintenance

Operation and

maintenance of vehicles.

9.

Other Costs

Utilities (electricity,

fuel, water, rent);

communications

(telephone, telex,

postage); licences and

permits.

10.

contingency

11.

inflation

42

furniture;

Here is how a project: budget might look:

PROJECT BUDGET (state currency)

PYI

Line Item

1.

2.

3.

4.

PY3

Total

Personnel

Medical Training officer

100

110

121

331

Nurse Tutor

Secretary

100

50

110

55

121

61

Driver

50

55

61

331

166

166

605

1000

1655

200

200

605

1655

Training

1 Fellowship

1000

5 Refresher Courses p.a.

1 Regional Workshop

500

-

550

-

Travel Costs

Support and Supervisory

Visits

500

Supplies

Office Equipment

1000

1 Vehicle

1000

■ Office supplies

Photocopies

5.

PY2

550

1000

-

-

1000

500

100

550

110

605

121

1655

' 331

500

550

605

1655

1000

1100

6400

3740

1210

4315

3310

14455

Vehicle Running and

Maintenance

(1000 km per year at .50)

6.

Other Costs

Contingency

TOTAL

43

Budget Notes

1.

10% inflation per year included.

2.

Refresher course cost based on an average of 20

participants and one week duration.

facilitators' per diem

participants' room and board

learning materials

stationery

100

Total Cost Per Course

3.

40

40

'10

10

Office equipment includes:

1 computer

1 photocopier

4 filing cabinets

- 44 -

500

300

200

Module 8:

Annex/Profile of the Applicant

Organization

Record of Achievements

And Who Are We?

In this Annex, you belatedly introduce yourself.

This introduction should include a description of your

organization.

If you have a brochure about your

institution or a suitable annual report, this may

suffice. If not, produce a short paper which provides

oasic information about the nature of your organization,

its legal constitution, number of employees and proportion

of professional staff, the size of your budget, your major

funding sources, institutional goals and key areas of

operation, both technical and geographic.

in addition to tne above general information, you

should.outline what your track record has been in relation

to the type of project you are now proposing to

implement. What has been your experience in planning,

managing, implementing and evaluating such interventions?

What have been your achievements in this area?

Finally, your proposal may be much enchanced if you

include short resumes of staff already on board, or to be

recruited, who will work on the proposed project.

45

SECTION TWO:

PROJECT DESIGN FRAMEWORKS

There is now widespread use of certain techniques for

presenting all essential project information in tables.

For some donors, these taoles are a compulsory part of the

proposal, others will ask you to use them when you make a

preliminary submission.

The two most important ones are the Logical Framework

(Logframe), pioneered by the us Agency for international

Development, and now also used by German, Canadian and

other aid agencies, and the Basic project Elements

Framework, developed and used by UNDP. in addition to

serving as concise analytic summaries of the proposed

project, these frameworks can be very useful for reviewing

and discussing project design in small groups.

Logical Framework

The Logframe states causal relationships between

goals, purpose, outputs and inputs, and the underlying

assumptions about the factors affecting them. It

encourages designers and planners to be specific, concrete

and realistic in describing the relationships between ends

and means. it also establishes a basis for project review

by providing indicators which allow comparisons of actual

and intended effects.

46

Basic Project Elements Framework

UNDP's Basic Project Elements Framework is based on

tne same principles as tne Logframe but uses a different

vocabulary, it specifies immediate objectives, outputs

and inputs and reviews success criteria, verifiers and

external factors for each item.

All these terms have already been discussed in the

eight modules of the preceding section. Should your

donors require a project design framework, you can ask

them or the UNDP office to provide you with the relevant

forms and instructions.

CONCLUSION

The chief purpose of this guide is to help develop

marketable proposals. We trust that the preceding pages

provide a useful overview of what needs to be done and how.

AS with any other skill, you will only be able to

develop competence as a result of experience and a lot of

hard work. Do not be discouraged if you are not

successful the first time. Perhaps you have not done

justice to your idea in the way you have presented it.

Perhaps you are courting the wrong donor or asking for too

much money or putting the case forward at the wrong moment

in time. After all, donors are business people and they

do not give their money away lightly.

We suggest that you follow the steps outlined in this

guide, using your own discretion depending on the subject

of the project and the preferences of the donor. Once the

planning and selling have been done, the battle is far

from over.

Rather, it is only just beginning.

The accepted proposal constitutes a contract between

the donor and the implementers. However, there must be

built-in flexibility to be able to modify the project

design in response to experience gained during

implementation. A well thought-out project strategy, a

sound implementation plan and a good monitoring and

evaluation system will go a long way towards ensuring the

success of your project.

49

Program Planning

&

Proposal Writing

Introductory Version

By Norton J. Kiritz and Jerry Mundel

Copyright © 1988, The Grant Smart ship Center

■

"■

11

foundation. It will often be 10-20 pages long, and the funding

source guidelines will contain the sequence to be followed in

writing the narrative portion.

Il is a good idea io read the information describing how

your proposal will be evaluated. Quite often, g< ivemmenl

agency guidelines describe exactly how each section of your

proposal will be weighed. This tells you what the reviewers

look for and helps you to organize your thoughts. If you are

told to limit your proposal to 10 single-spaced pages, don’t

include one or two more thinking that it won’t be viewed in

a negative light. Follow theguidelines meticulously, because

1. The cover letter

the reviewers will. Proposals can be deemed inappropriate

2. The proposal

simply because you failed to follow .specific instructions.

3. Additional materials.

Proposals going to government funders may also contain

unique forms such as face sheet forms where the entire

I.

The cover letter is signed by the Chairperson of the

project, names of key staff, budget, numbers of people

Board of a nonprofit agency, or the top authority in a

impacted by the project, etc. are indicated; assurance forms

governmental agency. Il briefly describes the program, and

(addressing issues such as human subjects at risk); equal

tells the grantmakcr how important the grant would be to the

opportunity policy statements; facility access to the

community served by the applicant agency. It shows strong

handicapped; and a number of other such forms. It is

support of the Board of Directors, which is essential in

important to understand which items must be submitted

^Jgaining foundation grants.

Along with your proposal and how they are to be completed,

2.

The body of t he proposal may be as modest as one pageso read the instructions carefully.

(in the case of a foundation that limits requests to a page) or

3.

Additional materials will generally include those

voluminous. It may be in letter form or a more formal

items suggested bylhe funding source. This usually consists

presentation. In either case, following the instructions in

of job descriptions, resumes, letters of support or

Program Planning & Proposal Writing (PP&PW) will help to

commitment, your IRS tax exemption designation, an annual

assure that the necessary items are included and are presented

report, financial statement, and related documents. This

in a logical manner. Remember one thing: PP&PW can help

you structure your thinking and even plan your project or section (or Appendix) can be extensive when a funding

program. It can serve as your proposal format where the source requests a great deal of information. There are

instances in which the funding source will request copies of

funding source has not provided one—as is often the case

with foundation proposals. Bui it should not be substituted certain agency policies and procedures, copies of negotiated

for anyformat required by a foundation. If they ask you to indirect cost rates, etc.

Generally, this will happen only once, and for refunding

follow a set format, do it!

packages to the same public agency, you will probably not

3.

Additional materials should be limited to those need to resubmit the same documents.

required by the funding source supplemented by only the

We suggest the following as a basic format for planning all

most important addenda. Reviewers don’tgrade proposals by

of your proposals. Thinking through the various sections

^^the pound, so save your postage.

should enable you to create virtually all that either a private

or government funding source will ask of you. It will also

The proposal package to a government funding source

enable you to develop a logical approach to planning and

usually contains these elements:

proposal writing.

1. Letter of transmittal

This is our proposal format:

Proposals written for private foundations and those

written for government grants (Federal, State, County or

City) usually differ in their final form. Foundations often

require a brief letter as an initial approach. A full proposal

may follow in many situations. Government tunding sources

almostalways require completion ofanumberofformsalong

with a detailed proposal narrative. Therefore, proposals to

private and government grantmakers look quite different

The package to a foundation or corporation will usually

contain these three elements:

2.

3.

The proposal

Additional materials

1.

The letter of transmittal is a brief statement (2-3

paragraphs) signed by the highest level person within your

organization. It briefly describes the request, the amount

asked for, and may indicate the significance and importance

of the proposed project It should reflect the Board’s support

and approval of therequest as reflected in the signature of the

Board Chairperson (possibly as a dual signature along with

the Executive Director/Chief Executive Officer).

2.

The proposal going to a government funding source

will generally be more lengthy than one going to a private

2

Program Planning & Proposal Writing—Introductory Version

PROPOSAL SUMMARY

I. INTRODUCTION

II. PROBLEM STATEMENT

III. PROGRAM GO,ALS AND

OBJECTIVES '

IV. METHODS

V. EVALUATION

VI. FUTURE FUNDING

VII. BUDGET

VIII. APPENDIX

^5) Eggacs ..... ■■■■■■....

PROPOSAL SUMMARY

The summary is a very important part of a proposal—not

just something you jot down as an afterthought There may be

a box for a summary on the first page of a federal grant

application form. It may also be called a “proposal abstract”

In writing to a foundation, the summary should be the first

paragraph of a letter-type proposal, or the first section of a

more formal proposal. The summary is probably the first

thing that a funding source will read. It should be clear,

concise and specific. It should describe who you are, the

scope of your project,-and the cost The summary may be all

that some in the review process will see, so make it good.

I. INTRODUCTION

In this part of the proposal you introduce your organization

as an applicant for funds. More often than not proposals are

funded on the reputation of the applicant organization or its

key personnel, rather than on the basis of the program’s

content alone. The Introduction is the section in which you

build your credibility, and make the case that your

organization should be supported.

Credibility

What gives an organization credibility in the eyes of a

funding source? First of all, it depends on the funding source.

A “traditional, conservative” funding source might be more

responsive to persons of prominence on your Board of

Directors, how long you have been in existence and how

many other funding sources have been supporting you. An

“avant garde” funding source might be more interested in a

Board of “community persons" rather than of prominent

citizens and in organizations that are new rather than

established.

Potential funding sources should be selected because of

their possible interest in your type of organization as well as

the kind of program you offer. You can use the Introduction

to reinforce the connection you see between your interests

and those of the funding source.

What are some of the things you can say about your

organization in an introductory section?

•

How you got started—your purpose and goals

How long you have been around, how you’ve

grown, and the breadth of your financial support

Unique aspects of your agency—the fact that you

were the first organization of its kind in the nation,

etc.

•

•

.»n

Iu

Thesupportyouhavereceivedfromotherorganizations and individuals (accompanied by a few letters

of endorsement which can be attached in the

■ Appendix).

We strongly suggest that you start a “credibility file”

which you can use as a basis for the Introduction in your

future proposals. In this file you can keep copies of

newspaper articles about your organization, letters of support

you receive from other agencies and from your clients.

Include statements made by key figures in your field or in the

political arena that endorse your kind of program even if they

do not mention your agency. For example, by including a

presidential commission’sstatementthat the typeof program

which you are proposing has the most potential of solving the

problems with which you deal, you can borrow credibility

from those who made the statement (if they have any).

Remember, in terms of getting funded, the credibility you

establish in your Introduction may be more important than

the rest of your proposal. Build it! But here, as in all of your

proposal, be as brief and specific as you can. Avoid jargon

and keep it simple.

IL PROBLEM STATEMENT

OR ASSESSMENT OF NEED

In the Introduction you have told who you are. From the

Introduction we should know your areas of interest—the

field in which you are working. Now you will zero in on the

specific problem or problems that you want to solve through

your proposed program. If the Introduction is the most

important part of your proposal in getting funded, the

Problem Statement is most important in planning a good

program.

The Problem Statement or Needs Assessment describes

the situation that caused you to prepare this proposal. It

should refer to situation(s) that are outside of your

organization (i.e. situations in the life of your clients or

community). It does not refer to needs internal to your

organization, unless you are asking someone to fund an

activity to improve your own effectiveness. In particular, the

Problem Statement does not describe your lack of money as

the problem. Everyone understands that you are asking for

money in yoursolicilalion. That is a given. But what external

situation will be dealt with if you are awarded the grant? That

is what you should describe, and document, in the Problem

Statement

Problem Statements deal with such issues as the homeless,

offenders returning to prison with regularity, children who

are far behind mjheir reading skills, youth dropping out of

Some of your most significant accomplishments as

■ school, and the myriad other problems in contemporary

an organization or, if you are a new organization,

society. Needs Statements are often used when dealing with

some of the significant accomplishments of your

a less tangible subject.’They are especially useful in programs

Board or staff in their previous roles

that are artistic, spiritual, or otherwise value-oriented. These

are certainly no less important as subjects, but they do not

Your success with related projects

Pngnm Planning & Propcnal Writing—Introductory Version

3

—----------------------------lend themselves as directly to the problem-solving model of

PP&PW. You would ordinarily deal with them as Needs and

Satisfaction of Needs instead of Problems and Objectives.

You should not a: sumo that “everyone knows this

problem is valid." Tha may be true, but it doesn’t give a

funding source assurance about your expertise if you fail to

demonstrate your knowledge of the problem. Use some

appropriate statistics. Augment them with quotes from

authorities, especially those in your own community. And

make sure that you make the case for the problem in your area

of service, not just on a national level. Charts and graphs will

probably turn off the reader. If you use excessive statistics,

save them for an Appendix, but pull out the key figures for

your Problem Statement. And know what the statistics say.

In the Problem Statement you need to do the following:

•

Makea logical connection betweenyourorganization’s background and the problems and the needs

with which you propose to work.

•

Clearly define the problcm(s) with which you

intend to work. Make sure that what you want to

do is workable—that it can be done within a

reasonable time, by your agency and with a

reasonable amount of money.

Support the existence of the problem by evidence.

Statistics, as mentioned above, arc but one type of

support. You may also use statements from

groups in your community concerned about the

problem, from prospective clients, and from other

organizations working in your comm unity and from

professionals in the field.

•

Berealistic—don’ttry andsolvealltheproblemsin

the world in the next six months.

Note: Many grant applicants fail to understand the

difference between problems or needs and methods of

solving problems or satisfying needs. For example, an

agency working with the elderly in an urban area said that

what the community needed were vans to get the elderly to

various agencies. They determined that this “need" existed

because not enough seniors were able to get to the social

security office, health services, and related human service

programs. What they had done was to immediately jump to

a “method” by which seniors would now be able to readily

receive services. The problem with that logic is that the

transportation suggested is a method and there arc other

methods as well. For example, what about the possibility of

working with institutions to dccentraliz.c services?

Alternatively, volunteer advocates could work with seniors,

acting on their behalf with some of these service providers.

Ultimately, buying vans might be the best method, but it is

clearly a method and not a problem or a client need. Be very

cautious about this. If you find yourself using “lack of

statements in the problem section, you are probably saying

“lack of a method." This starts you on a circular reasoning

track that will ruin the planning process.

4 Program Planning & Proposal Writing—Introductory Version

, ■!„,

.

■

HI. PROGRAM GOALS

AND OBJECTIVES

A well-prepared proposal has continuity—a logical flow

from one section to another. Your Introduction can establish

the context for your Problem Statement Similarly, the

Problem Statement will prepare the funding source for your

logical Goals and Objectives.

Goals are broad statements such as: Develop additional

resources to provide AIDS information to bilingual

populations; Reduce underemployment rates among adults;

Increase availability of resources to address the problems of

adolescent pregnancies; Create an environment in which folk

art is fully appreciated; or Enhance self-images of senior

adults. These types of statements cannot be measured as they

are stated. They offer the reader an understanding of the

general thrust of a program. They are not the same as

Objectives.

Objectives are specific, measurable outcomes of your

program. Object! ves are your promised improvements in the

situation you described in the Problem Statement When you

think of Objectives this way, it should be clear in most

proposals what your Objectives should look like. For

example, if the problem was that certain children in your

school read al least three grade levels below the norm for their

age, then an objective would be that a certain num ber of those

children would read significantly better when you had

concluded your program. They would read belter than their

classmates who had also been reading poorly, but who did not

have the benefit of your intervention. Tnese “outcome"

Objectives should state who is to change, what behaviors are 1

to change, in what direction the changes will occur, how

much change will occur, and by what time the change will

occur.

Another example of a measurable objective would be:

"Within 30 days of completion of the JTPA Classroom Training

Program, 75% of the 80 participating welfare recipients will have

secured unsubsidized employment at aminimum of $525 per hour.

and will maintain those positions for a minimum ol 90 days."

The Importance of Distinguishing

Between Methods and Objectives

- Many, if not most, proposals state that the purpose of the

program is to establish a program or provide a service. This

is consistent with most thinking in the nonprofit sector, which

sees the nonprofit organization as a “service provider." This

results in Objectives that read like this:

"The objective ol this project is to provide counseling and guidance

services to delinquent youth between the ages of 8 and 14 in the

blank community."

The difficulty with this kind of objective is that it says

nothing about outcome; It says nothing about the change in a

situation that was described in the Problem. That is, unless

the Problem Statement (perish the thought) said that the

problem was “a lack of counseling.” Presumably the Problem

Statement said something about youth being arrested, going

to jail, dropping out of school, or whatever.

Objectives should be specific, estimating the amount of

benefit to be expected from a program. Some applicants,

trying to be as specific as they can, pick a number out of the

air. For example, an agency might say that their objective was

to “decrease unemployment among adults in the XYZ

community by 10% within a certain time period.” The

question you need to ask is: where did that figure come from?

Usually it is made up because it sounds good. It sounds like

a real achievement But it should be made of something more

substantial than that Perhaps no program has ever achieved

that high a percentage. Perhaps similar programs have

resulted in a range of achievement of from 2-6% decrease in

unemployment In that case, 5% would be very good and 6%

would be as good as ever has been done. Ten percent is just

plain unrealistic. And it leads one to expect that you don’t

really know the field very well. Just remember that

Objectives should be realistic and attainable. Decide whether

the 10% figure is attainable. If not, then it is a poor objective

because you cannot achieve it.

Ifyouare having difficulty in defining yourObjectives, try

projecting your agency a year or two into the future. What

differences would you hope to see between then and now?

What changes would have occurred? These changed

dimensions may be the Objectives of your program.

A Note About Process Objectives

You may be used to seeing Objectives that read like this:

The objective of this training program is to offer classes in

automotive repair three times each week, for a period of 36 weeks,

to a group of 40 unemployed individuals', or

The objective of this program is to provide twice-weekly coun

seling sessions, lor a period of 18 weeks, to no less than 50 parents

who have been reported to Child and Protective Services for child

abuse.'

These are Process Objectives, and belong in the Methods

section of your proposal. They tell what you will do, and do

not address the outcome or benefit of what you will do. It is

critically important to distinguish between these process

Objectives and true outcome Objectives. If you do not do so,

you will end up knowing only what has occurred during your

program, and will not have dealt with the changes attributed

to your program: Remember, you have proposed your

program in order to make some change in the world, not to

add one more service to a world already overcrowded with

services and service providers.

Process Objectives may be very useful, but should only

appear in the Methods section of your proposal, so they are

not confused with the results of your proposed program.

IV. METHODS

You have now told the reviewer who you are, the problems

you intend to work with, and your Objectives (which promise

a solution to or reduction of the problems). Now you arc

going to describe th: Methods you will use to accomplish

your Objectives.

The Methods component of your proposal should

describe, in some detail, the activities that will take place in

order to achieve the desired results. It is the part of the

proposal where the reader should be able to gain a picture in

his/her mind of exactly how things work, what your facility

looks like, how staff are deployed, how clients are dealt with,

what the exhibits look like, how the community center

recruits and assigns volunteers, or how the questionnaires

will be administered and results interpreted.

There are two basic issues to be dealt with in the

Methodology section. What combination of activities and

strategy have you selected to employ to bring about the

desired results? And why have you selected this particular

approach, of all the possible approaches you could have

employed?

Justifying your approach requires that you know a good

deal about other programs of a similar nature. Who is

working on the problem in your community or elsewhere?

What Methods have been tried in the past and arc being tried

now and with what results? In other words, you need to

substantiate your choice of Methods.

The consideration of alternatives is an importantaspeclof

describing your methodology’. Showing that you are familiar

enough with your field to be aware of different program

models and showing your reasons for selecting the model you

have gives a funding source a feeling of security and adds

greatly to your. credibility. Obviously then, building

credibility only starts in your Introduction, and can be

enhanced as you demonstrate that you are knowledgeable

throughout your proposal.

Your methodology section should describe who is doing

what to whom, and why it is being done that way. Your

approach should appear realistic to the reviewer, and not

suggest that so much will be performed by so few that the

program appears unworkable. A realistic and justified

program will be impressive. An unrealistic program will not