RF_MP_2_A_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_MP_2_A_SUDHA

I

FORM 'G'

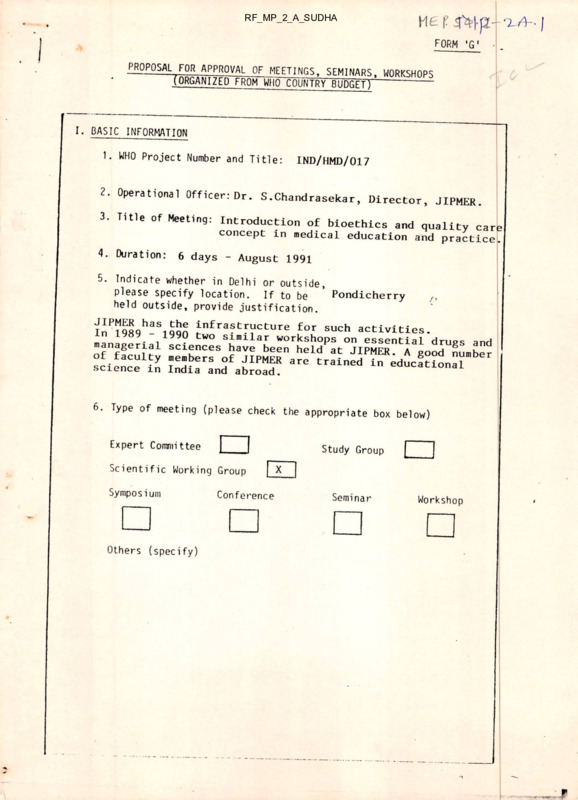

PROPOSAL FOR APPROVAL OF MEETINGS. SEMINARS, WORKSHOPS

(ORGANIZED FROM WHO' COUNTRY BUDGET)

~--------

I. BASIC INFORMATION

1. WHO Project Number and Title:

IND/HMD/017

2. Operational OfficerrDr. S.Chandrasekar, Director, JIPMER.

3. Title of Meeting: Introduction of bioethics and quality carl

concept in medical education and practice.

4. Duration:

6 days - August 1991

5. Indicate whether in Delhi or outside,

please specify location. If to be ’ Pondicherry

“

held outside, provide justification.

I^P19S9hTSlS5S jnfra?tF“‘:ture for such activities,

managerial sc?enc:sSL'ie"e“rteUP:t“i™™ntial “T85 S'"1

^ieS

1^

science m India and abroad.

6. Type of meeting (please check the

appropriate box below)

Expert Committee

Study Group

Scientific Working Group

Symposium

Others (specify)

-A

Conference

X

Seminar

Workshop

- 2

II. technical information

A. Justification

u\unv^^kSLOftot'’LPTposed activ,ty

undertaken in the past and tn Hp

l

? sequence of activities

the problem which the sequence of^ctivities

weting, is expected to solve; (c) iustifv whv «

type proposed ,s the nx.st .ppropria(e

St3tJ

udJng the Presort

We

for ooderpraduato^nH^ ln

a new curriculum

University ofPpond-'apUate studies in Medicine

_____

for the

we

workshop (Dec. 3-9) have

on

have already introduce^the171185

rationa]

T“

-- 1- prescribing,

We

undergraduates during thei? int0006^3 into the curriculum fpr

logical sequence to^fJlu. Lnternship training, We feel it

a

use with concept of qualitvScUP lnt5oduction of rational drilig

growing imp^rtanc^of^Jhi^. bi°ethiC3 keeping in

mind

and cost

effective cquality

is occurring and^s'

^nc^n

t

-.i the

medical

sciences that

scientific 8workit exPected to occur- in

r

next decade.

objectives 1, 2 & 3 fRefer15 expocted to dwell at length This

on

5

(Keter appendix I)

Central

th°e"dUcC“depr„fln:ernai1“’f«“^TUJ" De?e-"ber 1989

B. Specific Objectives

tPlease

i 14state

3.Vclearly

■ terms,

2

f the ProPosed nieeting, snow the

ese objectives to the programme area(s), and

identify the expected

-1 outcomes/outputs.

relevanrp nf th

See APPENDIX I

__ i

. . .3

I

3

c- Methods and Approaches to be used

(Please enclose a

copy of the tentative agenda)

See APPENDIX II

1

D.

Proposals for Evaluation and Follow-up

Please indicate: (a) the

me..,.ds of evaluation that you intend

to use during the meeting

to assess its effectiveness; (b) the

methods of evaluation you intend to i

'"'‘■""d to use in order to assess the

long-term impact of the meeting; (c) the’follow “

are .mended to be token end t’eil

d) actions that

------ /;up

(1)

cue time

frame for the

-.J ppreparation and submission of the Report.

Daily evaluation of the various sessions of the workshops.

(2)

Programme evaluation

(3)

Pre and post tests

(4) Outcome analysis is to be done f

to deans of "edxcal colleges seekUg through

li the questionnaires

ethics and quality

'care are included in the areas of bio

finding out the

ex

curricula and

*

---- extent of

f coverage.

...4

- 4

E. Participants/Invitees

(i)

Number of participants from States

(ii)

Number of participants from U.Ts.

(iii)

Number of participants from Ministry/DGHS

(Give designations)

(i v)

Other outside Invitees

16

8

Total Number

F. Technical Staff Support

Resource persons/Guest Lecturers

(Please give names and designations

with justifications)

Technical advisor

Technical staff for preparation

and duplication of course materials

Audiovisual assistants

1

2

2

y—

24

5 -

‘ill. BUDGETARY AND FINANCial

DETAILS

(i)

Total under the Project:

(IT)

For Group Educational Activities:

(iii)

Amount committed so far:

Rs.2,93,500

IV. expenditure sanction

require^ for

T.A. for

{!)

participants

(air/train/others)

(?)

Rs.

NIL

Rs.

NIL

per day for

days.

(4)

NIL

Daily allowance for outside parti. ?ants

□ t the rate of Rs.

(3)

Rs.

O.A. for local participants at the rate

of Rs- Per day for

days.

O.A. for

IQ

(no.) outstation experts

per day for

at the rate of Rs. 4QQ

10

(5)

days

Rs. 40,000

T.A. for 10

____ (no.) outstation experts

(□ir/train/others)

(6)

Rs. 2,00,000

O.A. for 14

(no.) local experts at

the rate of Rs. 200 per day for IQ dayS

Rs_2<LjOOO

(n Xrelar,ai aSS1Stance (Rs'50 Per day)

lease indicate rate of payment)

(H)

(9)

(2 persons for 30 days)

Stat.onery etc. (Please indicate articles

□nd quantity required)

lea/Coffee for

40

Rs. Wa000_

persons daily

10 days

( 10)

Rs. 3,000

Rs.2,500

Any other i tern

Rs1Q4KKL

Payment for technical assist.

Refer F p-4

TOTAL

Rs ._2x91>J0(L

Name, designation and complete address of the nffim t

I mills are to be released bv wiin

O'ficei to whom the

and account number. If any).

t’ nd,“e of the ^nk, its address

Dr. S.Chandrasekar,

J I P M E

Director>

Pondicherry 605 006

India

IM I o ■

ll? llu’

'• ''in.i | ih (.

H'.hii.ih./ri|,c.ra I lunal Or f •< ,.r

APPENDIX

I

B.

(1)

To identify <areas of

_2 ethics and quality

care that need to be

incorporated into medical

----- curricula.

(2)

To identify areas of ethics and

quality care concept

vant to various levels of health care.

(3)

(4)

(5)

rele-

To prepare 1teaching/learning modules relating to

content

areas that are found to be relevant

-- -—to medical educatic n.

To test the Iteaching/learning

—..o

modules developed on (a)

medical students and (b?

c

medical practitioners in order to test

ti'onUSehUlnuSS °f this approach and make r~

necessary modificagained.baSed On the feed back obtained and

--J the experience

To plan strategies for dissemination

of these concepts

through

educational interventions in

India and

other

developing countries.

APPENDIX

C.

II

To realise objectives 1,2 & 3.

(1) Scientific

relatino t°rKin8Jr°Up meeting to deliberate on

issues relating to bioethic:

various

---- 1 - quality

care that are of relevance to medical education and and

practice.

Tentative agenda

Day 1.

Overview of bioethics

Day 2 & 3. Selection of

priority areas for curricula

different levels of health care

Day 4,5 & 6.

(2)

for

Preparation of teaching/learning modules.

To realise objective 4.

Pilot workshops to test the

modules on the 1

and rmedical professionals

tessronals from primary, secondary

health

a care.

Workshop for medical students

Workshop for practitioners

(3)

and

and

tertiary

2 days

2 days - 3 workshops

To realise objective 5.

A 4 day workshop to j

sensitize

medical educators

issues and motivate them

2... to

to iincorporate these into on bioethical

curricula

continuing medical education

a programmes. With 3 educators and

college and 8 colleges

per

per workshop, 5 workshops would

about 40 medical

cover

-- - colleges from all over India.

Time schedule

RF. ••

August 1991

Scientific working group meet

Jan/Feb. 1992

Pilot workshops for medical

students and

practitioners.

1992-1994

(6 monthly)

Series of 5 workshops for medical

educators.

I

MODELS OF DOCTOR - PATIENT’ RELATIONSHIP

A STUDY BASED ON HOSPITAL ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

by

Akhileshwar Lal Srivastava *

Lecturer, Department of Sociology, Banaras Hindu University, ^nranasi-S

The

present

paper

deals with the

± nc

1

•

• *

tional setting and cultural matrix, in which the

doctor and the patient interact. The personality

characteristics of the doctor and expect ition

patterns of the patient provide the several

modes of doctor-patient

-------- relationship.

---------------------- Five

models of doctor-patient relationship are presen

ted in this paper

paper as

as probable

probable hypotheses

hypotheses for

for

empirical verification. In connection with his

research work the author had

— an opportunity

Ito meet doctors and patients both in hospitals

and private clinics. Whatever impressionistic

data thus gathered, the author has used them

in framing the model.

I•

With the rise of new medical values to make

man immortal from the medicinal point of

view, and change in the concept of medical

practice (preventive and promotive aspect), the

doctor-patient relationship has assumed new

dimensions.

The medical profession is a

phenomenon of interactional co-operation and

behaviour.

The doctor-patient relationship

occupies a key position in the functioning of

medical profession. Proper functioning of any

hospital system depends upon the functionally

congruent relations among the doctor and

patient and auxiliary workers.

The concept of doctor-patient relationship

denotes a situation in which the doctor and

patient along with their motivational require

ments interact with each other in a meaningful

way for clinical objectives. This doctor-patient

relationship does not operate in vacuum.

But

it is an end product of various interacting factors,

such as the professional training and competence

of the doctors, the role expectation of the

Patients, socio-psychological characteristic of

__

the doctors and the patients and the last but

not the least important point is the socio-cultural

matrix within which the whole medical system

operates. Keeping in view all these factors, it

may be said that the doctor-patient relationship

is not an individual phenomena but a !sociopsychological phenomena operating ir the

growing complexity of medical profession.

A typology of doctor-patient relationship

with

the....

following specification

may be f’amed

r

ior emPlncal investigation.

(1) Role-performance—It implies over: and

covert influence exercised by the .octor

over the patients in interaction. A cordial,

sympathetic and warm relation with the

patient is informal and a cold impersonal

relation is formal.

(2) Way of dealing—The main variable of

doctor-patient relation is the ‘way of

handling’ the patient, having the degree

of interest as the key variable. If the

doctor keeps his interest confined to the

“ disease and cure aspect ” of the f atient,

- it is specificity oriented relation, tf he is

oriented qualitatively in the whole per

sonal well-being and extra ‘disease-cure ’

syndrome, his relation is diffuseness

oriented.

(3) Organizational bureaucracy—In doctor-pati

ent relationship, several variations are

possible in following the rules an(J regu

lations of bureaucratic structure. If the

doctor follows them rigidly. he is termed

bureaucratic and if he follows them with

flexibility he is non bureaucratic.

The models are based on inc

of the author’**.

u

i

,

.

the nndmgs

findings

Hospital, B.H.U. ”

S

inC author« research work conducted on the te Sir Surider Lal

ussw***

Medical College, B.H.U. for their valuable guidance.

—t------- 2ssor and Head, Department of Sociology,

Of the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine,

29

MODELS OF DOCTOR-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

DECEMBER, 1971

Typology of Doctor-Patient relationship

(with doctor as Orientation agent)

Performance

Serial

No.

f

Role-Performance

Model

1.

Medico—Technocratic

2.

Magico—Angelic

3.

Angelic—Technocratic

4.

Medico—Particularistic

5.

Medico—Idealistic

Note

+ = Acceptance

Speci

ficity

Diffuse

ness

I

In-

Formal | formal

Bureau

cratic

+

+

+

+

+

NonBureaucratic

+

+

+

+

Organizational

Setting

Socio-cultural

matrix of dealing

+

+

+

+

+

+

- = rejection

D

P = doctor patient relationship

qualities are projected upon his personality.

Such an image is generally accepta ble to the

average Indian who has a tradition of ‘Vaidyas’

and

‘Hakims’. The private practitioner

acquires this image. He is sympathetic and

helping. He enters into informal ?hats with

the patients and shows utmost care for the con

valescence of the patients. Except ; 1 few simpie and convenient rules, he followss, no bureaucratic rules - regulations in his privately

managed clinic.

Model 1— Medico-Technocratic

The doctor is an expert of his branch

of specialization and works instrumen

tally. He adheres to the bureaucratic struc

ture of the hospital and maintains formal rela

tions with patients. His self image is of a

specialist demanding recognition of his skill.

He does not enter into formal conversation

with the patient or pays attention to the pati

ent’s extra-symptomic description. He ruthlessly

advises and maintains a distance from the

patients and auxiliary medical workers.

Model 3—Angelic Technocrat

Of course, he has all the qualities found in

the medico-technocrat except the ‘dealing’

aspect,. Inspite of his ‘expertise’ he maintains

all the cordiality and certain amount of

patience to bear the strains of informality.

Because of his expertise and warmth in hand

ling the patients, he is the most sought for

doctor in Indian cultural matrix.

Model 2—Magico-Angelic

In the doctor-patient relationship in Indian

cultural matrix, a magico-angelic doctor is

viewed with reverence as an ‘angel’ or ‘messiah’

of cure. He is seen as the saviour of life. This

image of the doctor is born out of his interac

tion pattern with the patient. Charismatic

l

2

j

30

VOL. X. KO' 4.

THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

Model 4—Medico-Particularistic

He is expert and bureaucratic having the

apparent aim of ‘impersonality , he develops

sometimes a soft corner for certain patients.

He: enters with

relations,- may. be due

wnu cathectic

-------------.

particularistic consideration-caste, communi-

X Pus:"IsrZrC'tc?'J,Hism"odel nf

of relation

relation ISis not

not

J-

—------

Sant’with the

d.is

a consistant

the ’doctor, rather it

is a

“ situational

emergent ” relation. For

/. tional emergent

or the weU

being

* r of fhis’ patient, he may deviate irom

from

organizational

.rganizational matrix and medico-ethics.

Model 5—Medico-Idealist

The

variation ux

of D. P-.relation model^l^and

ine vanauuix

of

model 5 is subtle.

- ---- ;

,

distinction is the ‘way of dealing’ with the

rlt.Hnetion

the rules and regulations

‘

11.

JLJ.W ***

wj** -----

y

1

’

«

•

•

«1 I

e'tr m no t nPil C.

informally

in D-P relation, He is

----------— ' sympathetic

r * < r

in relation with the patients but refuses pohtely’ to deviate. He is polite but ‘stern’ in

organization

fouowing rules-regulation Cof- the

* ~y

~

j

•

▼▼

tt

I • 1_ __„1

« w^rlirn-idealist.

^ch'matahim

°a

medico-idealist. ’

The models of relation presented above are

ideal types and by n0 means 1they, exhaust the

typology. We have presented on 1yj a few of

them for empirical testing. It is a conceptual

c

scheme derived out of observatior^, It needs

vigorous testing in various

x------- socio-cultural

■■ K&?

TA- 6

m

*

■

Mr ) rV.'^

•

C-M c '

,

■

.

- 1^(00^

■'

z

.

ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION IN INDIA

Solid organ transplantation is a rapidly evolving discipline

currently involving the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, intestines

and kidney. However, the Indian experience is confined to Renal

transplantation.

The incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD)

is 40-60 patients/mi11ion/year. Every year 30,000 patients are

added to this large pool. The logical solution is renal replace

ment therapy which is scarcely available and condensed around the

major cities.

A survey concluded in March 1990 revealed that

approximately 22,000 patients were dialysed in one year for acute

or chronic renal failure in our country.

It is J also estimated

that approximate!y 2000 live donor kidney transplants were done

in 1989 on India.

\

| vW'

''■*

■

.

- '

■

.■M

Renal Transplant Centres:

-

'

'■

■

The major academic institutions, as a matter Of policy accept

only those patients for maintenance dialysis^who have a prospect

of line related transplantation. The obvious reason for this

rationing and denial of life saving maintenance dialysis to this

large pool is grossly inadequate facilities for dialysis and

The

absence of cadaver renal transplant program in the country,

situation is by no means static as the last decade has witnessed

a phenomenal growth with establishment of around 200 centres for

regular dialysis and 30 centres performing renal transplantation.

However, despite this growth, the existing facilities are woeful

ly inadequate for the needs of this vast country.

Cadaver Renal Transplant (CRT) Prograa:

. . • . :j

‘

■

Instead of taking a logistic approach of developing a CRT pro

gram, there has been a trend

__ ‘_____

towards

2

the path of least resistance

ie. ,

the unrelated transplants with the spectrum of i associated

unethical practices.

It is true that CRT in India is beset with

numerous difficulties, such as scarce availability of hospital,

care for the critically ill,

ill

legislative silence-on brain death

criteria and organ donation, inconsistent and unreliable telecommunication and transport facilities and unawareness amongst the

Though

public and professionals regarding organ transplantation,

a tedious task, a viable local CRT program is desperately needed

to meet the growing need of organs and to combat the practice of

unrelated unethical renal transplants.

The * Kidney trade's

1

Recently there has been a lot of press coverage of the kidney

trade. An estimated 2000 or more kidneys taken from live donors

are now sold every year in the country — up from 500 in 1985 and

around 50 in 1983. And while initially it was restricted to

hospitals in the metropolitan cities, it has now moved to smaller

cities.

The 'Kidney business' now has a turnover of Rs 40 crore.

2)

(Contd.

/

'-■

:T

!

-: 2; -

filtruistic Donation:

The concept of Altruistic donation has gained momentum in many of

these centres.

Invariably most of these altruistic donation

is

backed by gratification and financial transection.

Many a

times

the

transection is involving the doctors too.

Lets go into

the

'live related donors'.

The results are very good in this group

and

the financial transections are relatively less.

There

has

been a lot of allegations where the donors have been made 'relat

ed donors'.

There is no agency to check the integrity of

these

related donors.

Un—related Donors;

What do you do for a patient who does not have a suitable related

donor?

Will you refuse treatment for a patient whose

re 1 atives

refuse donation

for various reasons.

These are some

of

the

considerations for those who propagate unrelated donors.

RECOHMENDATIQMS

I

have

a few recommendation to make to this august gathering.

The three major Christian teaching institutions can play a major

role in organising an ethical organ transp1 antation program.

1.

Cadaver Renal Transplant (CRT):

Political pressure must be instituted to have a viable legistalation for cadaver transplantation.

At the moment only the

state Governments of Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu

and Karnataka

have obtained legal clarity on vadaveric organ donation

and

detai 1ing

the

legal procedure for retrieving

organs

from

cadavers.

Despite these efforts, the CRT movement has failed

to gain the desired momentum,

There is an urgent need

for

the

parliament to pass a bill on cadaver organ donation

for

other states to follow.

2.

Concept of Al truism in CRT:

Un 1 ess

the public is made aware of the importance of

organ

donation,

they will never realise the need

for the

same.

Al truism

is a complex phenomenon.

People don't, just

decide

to

be altruis tic« charitable or benevolent.

They must

be

motivated

and guided

by

their

philosophies,

upbringing,

religious & social attitudes and the

immeasurable

contacts

that

effect their perception and determination.

It is here

(Con td.

3)

-:3:-

that media may be enlisted to play a

paramount

role ih

presenting positive attitudes about organ donation.

We must

therefore be over sensitive to opportunities to work with the

media and with the public directly, to inform and educate in

order to disseminate correct and meaningful information.

I here is also a need to evaluate the emotional and other

re

sponses

felt by donor families after a loved one has died.

The death could be traumatic, due to stroke,

primary

brain

tumour

(not metastatised),

or due

to methanol

poisoning

(these

patients can

be dialysed

then organs harvested).

This is a critical and traumatic time in the

life of

the

family and the approach must be psychologically befitting

to

the environment to initiate discussions on organ donation.

This

is a unique area of endeavour, and gentle care and

concern by those of us in the field will inspire and motivate

al truism.

Lack of knowledge or understanding about organ donation,

may

generate fear and mistrust in the minds of families.

In

the

same way , religious attitudes might raise concerns about

the

mor a 1

or religious propriety of invasion of the body of

the

remova1

of part for transp1 antation.

There may be mistrust.

or concern as regards the care or proper respect for a

body

after donation and a lack of confidence that it will not

be

muti1 ated.

There may be understandable

apprehension

that

voluntarily donated organs, perceived to be the act of generosity would somehow be sold for commercial gains,

One of the

most

significant

areas of fear or mistrust is

that organs

might

be removed from a person prematurely before death has

occurred.

People may be superstitious that if they

sign

4

donor card or even talk about the concept while

they are

a1ive, the event of death might in some fashion be preponed.

All these fears and concerns can be alleviated and d i spe11ed

by proper education, & judicious use of audiovisual media and

the written word,

It is imperative for the medical

prof es

sionals

to take up the challenge of educating the public

at

large about the need for organ donation.

To

promote altruism, there is need for advance

planning

to

provide

positive, accurate and informative message so

t ha t

transpl an tation may be better understood

practiced.

Medical

professiona1s engaged in the care of trauma victims

and,

ICU

staff are to be appraised of the need

for

organ

donation,

brain death and care of

such patients.

These

professiona 1s

are the referral source to the organ

procure"

ment team.

(Contd.

4)

-:4:-

3.

What else is the Option?

fill CRf becomes a reality we have to rely upon live donors.

Ethically we are justified to perform transplant on

live

related donors.

But what do we do for those patients who do

not

have a suitable donor?

Is it ethical to deny them

the

option of a live unrelated renal transplant? This needs

to

be discussed

in detailed in appropriate forums within our

hospital infra structure.

I would suggest that each hospital

have a organ donation ethical committee consisting the physician, transplant surgeon, social worker, representatives from

the citizens council and legal profession

to monitor

the

integrity of

these unrelated donors and

avoid financial

transec tions.

It is better to openly do an unrelated organ

transplant

in

excep t i on a1

cases by using a set protocol

mentioned above.

Her r/f • 7

Mr

CHRISTIANS IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

Date s 28^29/2/9 2

MEDICAL COLLEGES AND THEIR ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Ethics: Science of morals.

Moral

behaviour or code»

Moral behaviour or code is known to all of us. There is

a need, however, for us, a group,to dwell on this responsibility

as Christians, -working in and as part of a Medical College.

In this context of a Medical College, the areas that need

to be looked at carefully are, our ethical resoonsibilities.

A) As Teachers

B) As Managers/part of a working-team of a department

C) As members who are part of the Institution

D) As part of the vast realm of medical professionals in ?

country of numerous medical colleges and varied types of

medical colleges

E) As part of the Society in which we live

As Teachers

n Few boys are incorrigibly idle, and a few are incorrigibly

eager for knowledge, but the great mass are in a state of doubt

and fluctuation, and they come to school for the express

purpose, not of being left to themselves because that could be

done anywhere but that their wavering tastes and propensities

should be decided by the intervention of a master" Syndney Smith.

We are responsible for the finished product of our College.

The child that enters the portals of the Medical College and

the Doctor/Nurse/Allied Health professionals who leaves it.

- The one who enters has his qualifications and has made the

required grade.

- The process of education and training is over.

- He/she makes his/her place in society.

Broadly this may be a) A purely academic career - research, teaching

b) Where the skill acquired is used in the service of the

society

c) Professionalism or commercialising of the training.

.002/

2 z

Each College represented here has its own policies for

selection which are sound and carefully worked out. The

role played by St. John's Medical College in the moulding of

students to face ethical issues is basically in two phases:

Phase I.

Make known what the Institution stands for -

a) Institutional objectives spelt out in the prospectus

b) Ethical values paper included in the Entrance examination

c) The pattern of interview also conveys to the student/

"the ethical stand" of the Institution.

Phase II.

Create an ethos where the students are nurtured in

these ethical values by -

a) Classes on medical ethics/where the principles are taught

b) Providing role models - as teachers/ doctors/ administrators,

nonteaching staff and research staff.

The above steps will provide the student with the basic

foundation in ethics as a subject and the practice of ethics.

This in turn will provide uhe (guidelines in decision making.

I would add the Institution should look to Christ for

example. A Christ-centred life together with the knowledge

of ethics as a subject is the right amalgam.

There are stumbling blocks to the achieving of this goal.

You will be able to list many out of your experience as a

teacher.

As Managers, or Heads of Department

There is a need to constantly remind ourselves about the

stand we take in ethical issues that arise, The one I find

most difficult is to be a good example. Some of the areas

that need to be considered are -

- Using working time for personal errands

- Misuse °f office stationery

- Expecting the 'Helpers' to run errands at home and in the

office

- Overtime wages and compensation for every bit of extra work

o..o 3/

2

3 :

- Fear of the "Workers' Union"' when disciplining is necessary

- Discrepancy in "Management policies" in the various other

departments

- Writing "Confidential reports" on staff who have been irksome.

Do I misuse this hold I have?

and

- Our responsibilities in departmentally acquired infections

injuries.r

constantly supervise the staf£ in

- Need to protect, educate and

the department.

C) As members who are part of the Institution

In a Christian Institution, it is only correct to expect a

Reeling of a common bond with unity of purpose, working for

the common good of the Institution. This may be the case most

of the time but cannot be the case all the time. Few

examples are - Management versus staff issues. Either as individuals or

collectivelyo

~ Protection of the Institution's reputation in the wake of

public criticism.

- Our stand when various categories of staff from other

medical colleges strike work.

- Facilities/ per^cruisites and higher pay scales in corporate

hospitals which lure trained personnel away.

- Mission institutions under the control of the Church/Churchss/

Councils. If there is a resentment do we allL^rw it to grow?

Universities to which, the institution is ai.filiated

The

can pose problems* At times, the University expects

Christian Institutions to be "Lead Institutions" and at

other times laws and rules are laid down which require

major policy changes within the Institution - this may even

at times affect admission policies and the Institutional

objectives. What do we do?

s 4 s

E) Each one of us here belongs to the

in we live.

What is our role as health professionals? Do we have an

ethical responsibility towards -

- Building healthy communities?

- Do we discharge this responsibility as

a) individuals

b) groups of like-minded medical peonle

&

c) through philanthropic groups such as Rotary Club

d) as part of our Church activity

e) any other

Do we consider it as a mandate and find time for it?

Ethical issues in Biomedical Research

There are many facets to this. The guiding principles

are laid down by WHO»

In St. John's Medical College there is procedure for

ethical clearance of a scientific project. The project is

submitted to the’‘Ethical Review Board” comprising of a senior

and a junior representative of the pre and paraclinical

departments; one from the clinical section, a senior research

consultant (one who has had many years of research experience)o

Ethics Consultant, a legal consultant and the Principal of

the College. This committee/board meets, reviews the projeclts

for its ethical clearance and issues a certificate to that

effect. The board has the liberty to reject or modify the

project in order to make it ethically acceptable.

The other areas to be considered in ethics of research,

certain .issues that are not discussed in books. Some of them

are s (1) Authorship of the research outcome and the order

(ii) Interdepartmental research projects are best discussed by

the participating personnel and all issues agreed upon.

(iii) Using of departmental registers, patient’s charts for

analysing data. Bearing in mind the ethics of confidentiality

of patients reports.

■

*

Medical Education. 19X4. .8, 67-70

editorial

Medical ethics and medical education

Declaration of Sydney (1968) on the determination

of death, the Declaration of Oslo (1970) on therapeu

tic abortion, and the Declaration of Hawaii (1977) on

the responsibilities of psychiatrists particularly with

reference to possible misuses of chemotherapy and

invasive brain surgery.

The World Health Organization and in particular

the Council for International Organizations of Medi

cal Science (CIOMS) have long been concerned

about ethical issues in health care and the need for

the integration of medical ethics in medical educa

tion. While in the past the concern has arisen within

the medical profession and has been related either to

the control of medical malpractice or the dilemmas of

clinical medicine (particularly related to new devel

opments) now the pressure is increasingly coming

from the public and the media and relates to a series

of new issues of growing importance.

The first issue relates to the exponential growth in

clinical research and particularly in the trial of new

drugs, and public concern that there should be

adequate control and protection of the rights of

experimental subjects. This issue is particularly

focussed in the developed countries on the ifole of

Research Ethics Committees or Institutional R.eview

Boards in providing ethical review of clinical re

search. and concern at the absence of adequate

controls on pharmaceutical companies and medical

entrepreneurs in developing countries.

The second issue relates to the politic? ; and

economics of health care in a period of world

recession, and the ethical issues to which economic

scarcity has given prominence—namely questions

concerning the ethics of resource allocation. These

arise at several levels; in clinical practice (e.g. in

deciding between patients for renal dialysis or

intensive care when equipment and facilities are

limited), in the management of personnel and re

sources within a health care system (e.g. in shifting

resources from the acute high-technology hospital

Medical ethics, at any rate in the West, has been

traditionally based on the Hippocratic Oath, with its

threefold principles of respect for human life, confi

dentiality in fiduciary relationships and beneficence

(‘the duty to care and do no harm’). For many

doctors and health professionals the Hippocratic

Oath has been a sufficient basis for medical practice

and they do not see the need for new codes or

guidelines. However many developments in the

modern world and contemporary health care have, in

the view of others, made it imperative to clarify these

general principles of medical ethics and consider in

more detail their application in clinical practice and

the larger areas of health care administration in both

developed and developing countries.

Public outrage at the discovery, during the Nurem

berg War Crime Trials, of what had been done by

Nazi doctors in the name of medicine and scientific

research, gave major impetus to the review and

elaboration of medical ethics. The Declaration of

Geneva (1948 amended 1968) attempted to restate

the Hippocratic Oath in modern terms, affirming the

doctor’s duty of respect for human life and service of

humanity, the duty to care regardless of race, sex,

religion or social class; and respect for the secrets of

the patient. The Declaration of Helsinki (1964

revised 1975) sought to further clarify the ethical

principles governing clinical research involving hu

man subjects emphasizing informed consent and

proper scientific research design; and the Declaration

of Tokyo (1975) stressed that medical ethics pre

cluded doctors from participating in torture and

other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment.

Recent developments in bio-medical science and

technology have made it possible to achieve success

ful organ transplants, safe abortions, resuscitation of,

and artificial life support for, those who would

previously have died. This in turn has produced

pressure for further clarification of medical ethics: the

67

■

68

/. Thompson

medicine to primary care or to care of'the elderly and

mentally ill), and in attempts to achieve justice in

health-care at an international level (e.g. in providing

for more adequate staff and resources for developing

countries).

Medical training tends to focus attention on the

clinical relationship of doctor and patient, and much

recent discussion of medical ethics tends to have

concentrated on ethical dilemmas in one-to-one

clinical relationships. The discussion of such issues

tends to be couched in terms of personalist ethics and

individualistic values. This tends to overlook the fact

that doctors also frequently are involved in clinical

research with groups of patients, exercise consider

able power in the management of staff and allocation

of resources within institutions, and may play a

crucial role in determining policy at regional or

national level in their respective countries. The fact is

that personalist and individualistic ethics are in

general inadequate to deal with ethical decision

making at this level. Understanding of institutional

and political ethics with its more universalistic

concerns with justice in health-care and the common

good may be necessary, and these values may in fact

conflict at times with more personal understanding of

patients' rights and professional duties in a clinical

situation.

While there is a growing recognition that medical

education should include medical ethics, the empha

sis in existing courses tends to be either very

traditional (concerned with forensic medicine and

medical etiquette) or at best concerned with ethical

dilemmas of clinical medicine. Little attention is

given to the broader questions involved in medical

research, public health policy and the national and

international allocation of health resources, and yet it

is obvious that most doctors have to address these

questions at some time or other in their professional

life.

Medical Ethics and Medical Education, * a report of

the proceedings of the XIVth Round Table Confer

ence of CIOMS held in Mexico City from 1-3

December 1983, gives evidence that WHO and

CIOMS are attempting to address themselves to these

questions. The first two sessions of the Conference

relate to the ethical review of clinical research,

dealing both with general principles and considering

local applications in several different countries in the

* Medical Ethics and Medical Education. Edited by Z. BANKOWSKI

& J. Corvera Bernadeli.I. Council for International Organiza

tions of Medical Sciences. Geneva. 1981. Pp. 281. Sw. Er. 20.

Americas. The publication also includes the most

helpful Provisional Guidelines for Ethical Review

Procedures for Research Involving Human Subjects.

The third session was devoted to discussion of both

the theoretical importance of medical ethics in

medical education and some interesting practical

examples of courses where the attempt has been

made to integrate medical ethics into the medical

curriculum. The final session was concerned with

the broader ethical and policy questions involved in

the relationship of medical education and govern

ment.

The introductory papers were particularly out

standing. John Ladd, a philosopher, in addressing

ethical issues in human experimentation criticized

Research Ethics Committees (or IRBs) for being

unduly pre-occupied with questions of informed

consent, pointing out that most committees are less

concerned with the ethical issues of protecting patient

dignity and autonomy than protecting themselves

and the institution from legal action. Iriformed

consent as a legal notion pre-supposes an adversarial

relationship between doctor and patient which en

courages defensive responses on the part of both. He

pleads for a disentanglement of moral arid legal

aspects of the subject, greater awareness that ‘bourge

ois’ ideals of freedom are largely inapplicable to

patients who are highly dependent because qf need,

institutionalization or socio-economic circumstances,

and that the real challenge of facilitating patient

autonomy means getting away from legalistic inter

pretations of informed consent.

On the subject of research he pleads for a greater

awareness of the different value-conceptijons or

ideologies underlying those whom he calls ‘enthusi

asts’ and ‘restrictionists’. Both those who consider all

scientific research invariably benefits mankind and

those who are afraid of its Faustian pretentions tend

to argue from absolutist premisses. He argues very

persuasively that both positions need to be qualified

by human compassion and insistence on mainte

nance of the highest standards of scientific research.

He concludes that there are three factors which must

be taken into account in determining the moral

quality of a medical experiment on a human subject:

(a) the balance of risk and benefit for the subject; (b)

the adequacy of the project and its potentiality for

reducing suffering or benefitting future patients; and

(c) the relationship between the experimental subject

and those who stand to benefit from the experi

ment—that is, whether they are remote from him or

■

Editorial

69

•

%

people to whom he is related by some kind of

community of interest.

Robert J. Levine, in discussing the value and

limitations of ethical review committees, makes some

provocative comments as a clinician which must be

of interest to those serving on such committees. He

first points out that the limited research on such

committees in the U.S.A, suggests both that they

have contributed to better protection of the rights and

welfare of human subjects, and also contributed to

the improvement of the quality of research proposals

submitted and the quality of the research done. The

values which such committees attempt to uphold (in

the light of the Declaration of Helsinki and other

directives) are the following: (a) there should be

informed consent; (b) there should be good research

design; (c) there should be competent investigators;

(d) there should be a favourable balance of harms

and benefits; (e) there should be equitable selection

of subjects; and (f) there should be compensation for

research-induced injury. However, he suggests that

ethical review committees are often limited in what

they can do because they lack credibility. This lack of

credibility is related to the fact that many spend too

much time on unimportant details, that there is poor

co-ordination between different committees where

multi-centre trials are involved, there may be incon

sistent criteria determining which projects require

review and which do not. in the absence of standar

dized procedures committees will vary in the quality

of review given, there is no provision for monitoring

research approved, and some committees have diffi

culty in recruiting members who command the

respect of the institution or community they serve.

Francisco Vilardell gives an excellent analysis of

ethical issues in gastroenterology and how these can

be monitored effectively by laying down clear

criteria. The paper is very specific and detailed and is

a model of how ethical review can be developed in

specific clinical areas.

John F. Dunne gives a masterly overview of ethical

review procedures for research involving human

subjects, distinguishing three different kinds of re

search each with its own attendant ethical problems:

(1) detailed studies of a physiological or pathological

process in response to specific interventions, in one or

more individuals; (2) prospective controlled trials of

specific therapeutic regimens in larger groups of

patients; and (3) field studies in which consequences

of prophylactic or therapeutic measures are deter

mined within comparable communities.

In relation to these different kinds of research he

draws attention to several kinds of ethical problems.

First, whether in determining research policies coun

tries will use public funds competently for the general

benefit of society. Second, in developing countries

there are specific problems which arise because of

external sponsorship of research. These include

research projects which are unrelated to the country’s

primary needs, make heavy demands on limited

medical staff and resources, may be in conflict with

local customs and mores, and do not involve long

term commitment to the country or accountability to

its people. Third, developing countries lack the

medical infrastructure in toxicology and pharmacol

ogy to support the regulatory apparatus for monitor

ing new drug developments. Fourth, there is a risk of

exploitation of the underprivileged by sanctioning

research in developing countries that would not be

tolerated in countries with better general levels of

education and health care.

More generally his paper also contains some

excellent observations on the limited usefulness of

the notion of‘informed comment' when dealing with

research involving children, pregnant women, the

mentally ill and when public health measures (e.g.

fluoridation) involve whole communities. These

situations require other safeguards such as proxy

consent, review tribunals, provision for compensa

tion for personal injury and public accountability of

individuals or institutions involved in research.

The succeeding papers were of considerable inter

est in documenting the specific provisions for ethical

review of clinical research in Argentina and Chile,

specifically and more generally in the LatinAmerican Association of National Academies of

Medicine. Two papers of particular interest deal with

difficulties of doing paediatric research in Latin

America with conservative attitudes of parents and

established institutions (Kumate), and research re

lated to fertility control in women (Stoltz) where the

same difficulties apply compounded by the subordi

nate and oppressed condition of many women.

Other papers deal with the teaching of mainly

traditional forensic medicine and medical etiquette in

Venezuela and Brazil, and reveal a debate internal to

North American medical schools, namely between

the teaching of‘bio-ethics’ or ‘clinical medical ethics’.

The development of the Hastings Center and the

Society for Health and Human Values focussed

attention on the need to examine medical ethics in

the wider context of ethical and value questions in

70

1. Thompson

the bio-medical sciences in general. The initiative in

reseat ch had come from theologians and ethicists

rather than doctors. Mark Siegier criticizes this

dttf«lopment and argues for a restriction of medical

ethics to what he calls 'clinical ethics’ and preferably

taught by ethically literate but clinically competent

doctors. Edmund D. Pellegrino, doyen of bio-ethicist . defends the broader view and argues strongly

lor the injection of more training in the humanities

into medical education. In part the debate is about

method and content of medical ethics teaching:

whether it should be theory based or case based,

whether it should be given by philosophers or

clinicians, or in a multi-disciplinary mode, whether it

should be primarily medical or concerned with the

bio-medical sciences in general. In part also the

debate is about the scope of medical ethics: whether it

should be restricted to clinical, doctor-patient rela

tionships or whether it should lake in the ethical

responsibilities of doctor as researcher, hospital

manager, public health planner, policy maker for

health services generally, and international issues as

well.

1 he I nal closing addresses deal with some of these

issue.- but less satisfactorily, perhaps because no one

has really thought through these issues very carefully

just yet. The two Latin-American contributions are

mamly a plea for the independence of medical

schools to be respected, for epidemiological rather

than political criteria to be employed in defining

priorities for developing health services at nations

and regional level, and for realistic partnership ir.

striving to attain the WHO objective ol ' Health for Ab

by the Year 2000. Fitzhugh Mullan's paper is a rathci

smug defence of the U.S. National Health Service

Corps as a means of dealing with the health problciih

of deprived areas by scholarships to medical studcnirequiring them to do compulsory serv ice in deprived

areas following qualification. Why those who car.,

afford to finance their own medical training should

not have to do so is not made clear. Howard 11

Hiatt’s paper is a most useful beginning to

discussion about the need for training of doctors in

health policy and management and the ethical issues

involved al that level.

What this excellent publication lacks is a detailed

discussion of the wider ethical issuei of justice

health care between the developed a id developii.t

countries. What is needed is a WHO 'Brandt Report

which would deal with the ethical and educational

challenges to doctors of the North-Sou th polarizalior.

of wealth and poverty, health and disease, medical

resources and the lack of them.

1. Thompson

Scottish Health Edu|cation Group

Centic.

Health Education

T 1

Woodburn House, Canaan Lane

Edinburgh

^4 lo

Mr-? a-g

Medical Ethics and its Place in

Undergraduate Curriculum

By

Satya Parkash

Dean, Medical Superintendent and Professor of Silvery, Jawaharlal Institue oj

Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Pondicherry.

‘'Amongst our contemporary experts physicians are

those trained to the highest level of specialised in

competence for this highly needed pursuit"

(/van HUch - 7976)

ABSTRACT

Ethical consideration have a bearing in most disciplines of medical practice

including, research on human beings, therapy on children, mental aberrants, geriatric

patients and similar other gn ups. A 20 hour teaching programme at undergraduate level

and intern level is recommended, which may be incorporated in the existing curriculum.

J

The relationship between a physician and

a patient, in a wider sense, has been a peculiar

have tried to question this distinction (Kass,

■’983). All the same, lack of a strict code can

|

one; of absolute blind faith bordering on

worship to complete mistrust and hostility.

cause havoc with the interests of a sick and

therefore gullible and open to suggestions.

Both the responses are understandable and

i justified. Certain codes weie laid down since

C

:

ancient times which governed relationship,

based on correct perspectives, with a

i view to

proiect the interests of the patients ;as well as

safeguard the legitimate interests

of the

physicians.

Medical people like to describe them

selves as professionals rather than

tradesmen

which per se means professing

to a certain

code of ethics, but

on the other hand traders

l also have a code of ethics

and some gn-ups

Ethics is a much more complicated pro

blem these days with the availability of

assisted life processes, use of cadaver or near

dead and live donors, trials and therapy and

Investigations on human including use of

placebos, question of informed consent when

applied to children or mentally retarded,

euthanasia, medicolegal aspects taking into

account the laws governing the community

and the social structure. Requirements of an

informed consent even for the tried and

accepted

or

surgical

other therapeutic

I

4

1'

52

Indian Journal of Medical Education

measures is not easily spelled out. There is also

a problem of certain drugs which have been

discontinued in some countries, but considering all aspects, may still be useful in some of

the less developed countries where the priori

ties may be different.

Ethics Through the Ages

Ethical codes are as old as medicine. Strict

codes were laid down in ancient Egypt and by

Summarians in about 3000 B. C. Hammurabi's

code in 1200 B. C. laid down severe penalties

for harm following treatment (Thorwald

1952). Sushrutha laid down a moral obliga

tion on the part of surgeons, the patient and

a strict criterion for selection of a candidate,

which may not accord with modern concepts

(Shankaran, 1976). It is recorded that during

the Buddhist period, in India, a public

affirmation of conduct and etiquette was laid

down (Thorwald 1962). Hippocratic Oath is

well known to need any mention and it is

still in vogue in some places, though parts of

its are totally out-moded; some of his

aphorisms have still an eternal message.

However, most of the codes, oaths or affirma

tions were more in the way of ethics laid

down regarding personal relationships between

the physician and his patient and do not have

answers for the problems of to-day.

The modern interest in a suitable code

arose when the world conscience was stirred

by what happened in Nazi Germany and was

the Nuremberg code of 1947. This insisted on

a “voluntary consent” for all experiments

where human beings were involved. World

Medical Association in their meeting at

London in 1949 laid down a code for medi-

Volume XXIV No. 3

cal research. In 1964 W. M. A. adopted’

HELSINKI I declaration governing clidicaj

research and informed consent. In 1975'

"I'

HELSINKI II declaration broadened its scop£

to include , biomedical research involving

human subjects (Bankowski, 1982). Most of

these-'principles were incorporated by th^

I.CM.R. Committee headed by Justice AX

Khanna in 1978 (Satyavathi, 1982; Medappa,*

1980).

Research on Humans

Research on humans is accepted as justified

but is governed by a strict stipulation in the

way of its necessity, because of an inadequajl

animal model, its relevance, peer acceptance

informed consent, rules regarding suspension

of the project if there was any adverse

development or a withdrawal by the volunteef

Informed Consent

This is difficult to define, particularly ii

the context of routine therapy or an operativ

procedure. Warning the patient about all th

possible complications will scare away mpjfe

patients from useful medical aid. Tb&

Supreme Court of Canada in 1980 justified

informing only of special risks of the co^

templated therapeutic procedure (Browi

1984.) On the other hand, a free informt

consent will not absolve the clinicians froi

liability in the case of negligence. Son)

principles would apply to invasive investigl

live procedures. Consent for therapy for tb

benefit of the patient may not pose an ethiefl

problem, but a procedure to benefit soml

other person or purely for research can P

open to objections (Bankowski, 1982.)

September- December 198r

Consent in Children

It is not clear if a guardian can give a

consent for an invasive procedure on a child

which is not of direct benefit to it. What is

more important is whether a child be permitted

to die or come to serious harm, because an

important parent withholds consenbfor a life

saving or a vital procedure.

Research in children is permitted only for

such studies which are exclusively for their

benefit and cannot be done except in that

age group. In older children it should be

possible to obtain their consent apart from

that of their guardian. Similar criteria will

govern mentally unsound patients, patients in

coma, etc. Question may also come up when

research involves less sophisticated com

munities incapable of appreciating the nature

of the trial. No trial can be done on false

pretenses or misrepresentations. Prisoners are

a closed community and a suitable group for

trial, but on the other hand any research based

on financial or other inducement or anyother

considerations or would be not free consent

and thus be illegal (Bankowski, 1982).

Placebos in Therapeutic Trials

Placebos have a place in therapy and also

in double blind trials. However, if their use

results in withholding proved beneficial treat

ment, it is open to objection.

Untried and New Therapeutic

Procedures; Peer Acceptance :

In 1874, Sir John Eric Ericksen opined in

favour of sanctity of the abdomen, chest and

brain from the surgeon’s knife. This was in

i

Medical Ethics...53

spite of the fact that a successful laparatomy

had been done in U.S.A, in 1814 and that

intestinal surgery was performed by Sushrutha

in 600 B.C If such authoritative opinion

had been accepted, there would have been no

progress in medical sciences (Aird, 1961).

Peer acceptance is important but it has to

be remembered that top medical opinion in

early nineteenth century declared Simla as

unsuitable for Europeans because of lack of

oxygen at those heights. Lice in boys’ hair

were considered part of masculinity. Smoking

was considered good for the lungs on medical

grounds and was introduced in public schools

like Eton. Breast feeding was considered an

imposition on women, only a few years ago.

Life Support Systems and

Concept of Death :

Introduction of mechanical respirators in

1950 and cardiac resuscitations in 1950 have

led to a large number of patient being kept

‘alive’ for monihs or years. A patients’

committee in USA recommended defining

death when there was an irreversible cessation

of function of the entire brain, including brain

stem. This has led

to the anomalous

positions such as in the case of Karen Ann

Quinion where higher brain function was lost

but not that of the brain stem (Editorial

Annals of Internal Medicine, 1983). Youngner

and Bartlett (1983) favoured irreversible

upper brain loss, i.e. permanent loss of

consciousness and cognition as the criteria.

Support systems are expensive and relatives

may be unable to afford and may even feel

disturbed at a irrecoverable relative being

kept part alive to a vegetative existence. On

^3

54 Indian Journal of Medical Education

the other hand, in the absence of clear cut

guidelines, the hospital authorities may expose

themselves to charge of murder, if patient is

taken of such systems.

Sanctity of Human Life :

■ •

’^lume XXIV No. 3

trical or other assessment, There must be

substantial safeguards, including a suitable

heavy insurance for such donors.

Robertson (1983) has raised a pertinent

point about loss of human dignity in an

incontinent old person, unable to lool after

himself who becomes a social burden and

source of embarrassment, since he might

expose his body or behave or conduct himself

in someother indecent manner. The family

had built up an image of him through the

years, of a highly revered and respected

symbol in the family. This is lost causing lot

of pain and anguish to all friends and

relatives. Why can one not permit a will for

self deliverance when one is in his senses ?

Social ethos in this context are para

doxical. It is patriotic to kill the enemy in

war but to give him full succour and respect,

if the person is taken as a prisoner. Dozens

die in increasing civic unrest round the world,

but a doubtful default in a patient care even

with an irrecoverable illness may hit head lines

and lead to serious difficulties for the physi

cian. A. numoer of individuals commit suicide

when a political or screen hero is seriously

ill, and this behaviour is accepted socially and

seldom discouraged. Death due to social

A similar case could be made out for

inequalities are common in the poorer coun

patients

born with gross congenital defects

tries, but most societies frown on euthanasia

or

incurable

painful and distressing conditions,

in any circumstances. Sanctity for life extend

such

as

advanced

malignancies. Are support

ing even after death to a cadaver or near

cadaver, has a bearing in obtaining organs systems justified in such cases ? Is it the

like the kidney for transfer as well as utili physician’s job to prolong the act of dying ?

sation of cadaver parts such as cornea, blood,

bone and split skin graft. Most of this Professional Etiquette

material could be of great benefit to the living

This is governed by rules laid down by the

with no harm to anybody, unlike obtaining

Medical Council and this governs -•j—*-■ ■

advertising,

parts from live donors. Most donations,

responsibility of a professional act, copduct

irrespective of what the declaration are for

towards patients and fellow physicians etc.

a consideration, social pressure, emotional

Jurisprudence lays down Jaws regarding

involvement, financial inducements, media

abortion, sex. marriage, professional liability

publicity, hero instinct, etc. Is it ethical to

and they may vary in the same country for

use a major organ from a live donor ? France

different communities. There is also conforbids use of live donors (Holston and

troversy as to how far a professional person

O’Conner, 1966) In India there appears to is liable in his individual capacity and

how

be no law in favour or against such donations far he acts as an agent when he is e

np oyed

and most countries do allow such donations by an agency, such as the government,

in

after a suitable informed consent and psychia- which case the liability mt.v also be of the

September December 1985

Medical Ethics...55

employer and as a consequence he may lay

down constraints on his professional work.

to exposure to it. Olukoya (1983) of the

Logos University of Nigeria found that 88%

Community Programmes Without consent

of ciinical students showed interest in the

subject and recommended inclusion of this

subject as a part of the curriculum. Givner

Community bodies also permit compulsory

drueaing in the way of supplemented foods,

such as iodised salt or flour supplemented with

calcium and enforced innoculations or vacci

nations. Pollution of the environment is

common and is often permitted by the

community. Smoking in public places is a

r classical example and exposes a large number

< of unwilling people to passive smoking, which

I may be more dangerous, even then smoking

by the individual himself. This exposure to

drugs and chemicals is without* any infoimed

or uninformed consent.

Quackery

In 1551, Queen Elizabeth-I could not get

Margaret Kennix, a traditional practitioner,

registered with either of the colleges which

had obtained the royal charter from her

(Simpson,

1962).

An association

with

an

unqualified person was forbidden in the

Hipprocratic Oath, On the other hand in

some countries, particularly the poor countries,

traditional healers have a useful role to play

and this has been well accepted by the WHO.

Also with tne present day highly sophisticated

modern therapy, association with non-rnedical

non-professional personal is inescapable.

Medical Ethics in Undergraduate Curriculum

In view of the complexity and wide range

o the subject, it stands to reason that a suit

able part of tae curriculum should be allotted

and Hynes (1983) found a positive advantage

in outlook of students exposed to medical

ethics for three months Cassidy, Swell and

Stuart (1983) incorporated this subject as a

part of family practice clerkship for the year

IV year students. Thung (1981) emphasized

exposure of medical students to the pleuralistic

morality governing patient’s acceptance of

medical advice in the cognitive and

non-

cognitive fields, in the case of a child patient,

he analysed the role of the child, parent,

doctor and society in acceptance of treatment.

Keller, 1977 recommended a course for

residents consisting of 5 halfdays in I year, 3

days in II year and a day including an

assignment in III year.

The present curriculum allows for two to

three lectures on the legal aspects of the subject

as a part of the forensic medicine curriculum.

The first year students are exposed to 20 hours

course in

community medicine including

sociology. Medical ethics is very akin to the

subject and it is proposed that a 20 hour

programme distributed between first to fifth

year be introduced. Four lectures could be

devoted to the definition of death, informal

consent, etc. and could be part of the PSM

teaching programme in the first year. The

lecture programme for the jurisprudence could

remain unchanged and be covered in 3 to

4 hours of teaching. Department of Pharma

cology could devote one to two hours in

relation to drug trials. Similarly the other

clinical and non-clinical departments could

e

55

Volume XXIV No. 3;

Indian Journal of Medical Education

aspset can be evaluated

as part

devote one to two hours teaching programme

in the ethical aspects pertaining to their

This

specialities. The stress should be on exposure

to the existing problems and taking into

account the accepted norms of the society.

be given suitable assignments during their

evaluation of the subject.

posting in Community Medicine with thfc

PSM department.

REFERENCES

1.

The interns may

Aird, I. The making of a surgeon, London Butterworth, 1961, p. 93.

2. Brown, F.N. Some comments about informed consent. Canadian Journal of Surgery,

27:131-2, 1984.

3.

Bankowski, Z. Ed. Proposed International guidelines for biomedical research involving

human subjects. C1OMS, WHO, Geneva 1982, p. 1-40.

4.

Cassidy, R.C., Swell, D.E. and Stuart, M. Teching biopsycho ethical medicine in

family practice clerkship. Journal of Medical Education, 58 : 778-783, 1983.

5.

Editorial—I he determination of death. Annals of Internal Medicine, 99 : 261-264,

1983.

6.

Givner N. and Hynes, K. An investigation of change in medical students’ ethical

thinking. Medical Education, 17 : 3-7, 1983.

7.

Holston, G.E.W. and C ’Conner, M. Ethics—Medical progress with special reference

to transplantion—A Ciba Foundation Symposium, London, J. & A. Churchill,

1966 pages 1-257.

8.

Illich, I. Limits to medical nemesis—the expropriation of health London, Marion

Boyals, 1976, p. 6.

9.

Kass, L.R. Professing ethically—on the place of ethics in deCning medicine, JAMA,

249 : 1305 1310, 1983

10.

Keller, A.H. Human values of education in the family practice residency. Journal of

Medical Education, 52 : 107 116, 1977,

11.

Olukoya, A.R. Attitude of medical students and medical ethics in their curriculum.

Medical Educaticn. 17 : 83-86, 1983.

i

•S-

12.

o, ta.n Mure |n

Krtmon. C.S. E,h,t,|

287 ; II75-1] 77, 1983.

J3.

Satyavati, G.C. Ethical considerations

in medical research—Paedi tries.

208, 1982.

19 : 201-

14.

Shankaran, P.S. Sushtutha’s contribution to

surgery, Varanasi. Indolog,.dl Book

House. 1976, p. 15-25.

15.

Simpson, R R. Shakespeare and medicine, Edinburgh & London E & S I ' •

1962, pages 69-70.

s

^onaon, t & S Livingston,

16.

Thorwald, J. Science and

secrets or medicine, London, Thomas & Hudson, 1962,

pagee 120, 218-219.

17.

Thung, P.G. Introducing medical students

to ethical issues. Medical Education,

15 : 79-84, 1981.

i

L

18.

»

oi internal Medicine, 99 : 252-258, 1983

5’7

7.

Si

J

S4-11

I

Doctor Patient Relationship —

The Neglected Domain of Medical Education

By

N. Ananthakrishan

Lecturer in Surgery

Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Pondicherry.

J

ABSTRACTS

r.

2

An analysis of the lacunae existing in the field of doctor-patient relationship

during the training period of medical personnel revealed intrestmg facets many of

them amenable to correction with little outlay of man or material. It appeared that

a small shift in emphasis during training along with other miner remeuiai measures

may go a long way in correcting this unhealthy state of affairs. An analysis of the

existing problems has been presented and detailed suggestions made to evolve a

strategy to rectify the same.

Introduction

f

The entire duration of medical training,

undergraduate and postgraduatete is concerned

.1

___________________ 1

mainly. .with the

cognitive

and psychomotor

domains, to the detriment of achieving profiency in what might be the most important

quality expected of the doctor, and perhaps

the one most difficult to master, viz. an ability

to establish rapport with patients and to

communicate with them to the patients

satisfaction.

At the termination of their

training period the end products of medical

education are left to acquire this proficiency

in the affective domain entirely on their own.

This state of affairs is unfortunate, since

S L doctors* work involves not only activity and

| decision making but also communication. It

| cannot be denied that currently there exists a

| profound communication gap between trainee

doctors and patients due to lack of either

ability (physical or mental), understanding or

motivation which leaves the patient some

times bewildered but more often dis-satisfied.

Much of the research on the relations

between cognitive achievement and attitudes

and values shows them to be statistically inde

pendent (Bloom et. al., 1964). This is illus

trated by Mayhew (1958), who reported little

relationship between attitude changes and

growth of knowledge in a college course.

Inspite of research and writings to the

contrary by Tyler (1934, 1951), Furst (1958),

Dressel and others there still persists an

implicit belief that if cognitive objectives are

developed, there will be - corresponding

development of appropriate affective behavi

ours. Jacob (1957) has raised serious questions

about the tenability of this assumption.

82

VOLUME XX JV9. 3

THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

Bloom et. al. (1964) studied the history of

several major courses at the general education

level of college and found that in the original

confined to

surgical

patients and surgical

trainees.

PROBLEM

statement of objectives there was frequently as

much emphasis given to affective objectives as

to cognitive objectives and even small attempts

were made to secure evidence on the extent to

which students were developing in the

affective behaviour. However, as these courses

were followed, there was a rapid dropping of

the affective objectives and an almost complete

disappearance of efforts at appraisal of

student growth in this domain,

because it is easier to teach and

perhaps

evaluate

cognitive objectives.

In medical college curricula in India also,

institutional objectives often make mention of

the need to develop certain attitudes in

students but little if any effort is paid to this

aspect of their training.

Evaluation material in the affective domain

is rare and is usually connected to some

national educational research project or a

sponsored local research project (Bloom et al,

1964). In the medical curriculum evalua

tion work for effective

objectives are non-

existent.

A study conducted by the author amongst

patients and colleagues, especially those

undergoing training, to identify the extent and