15966.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

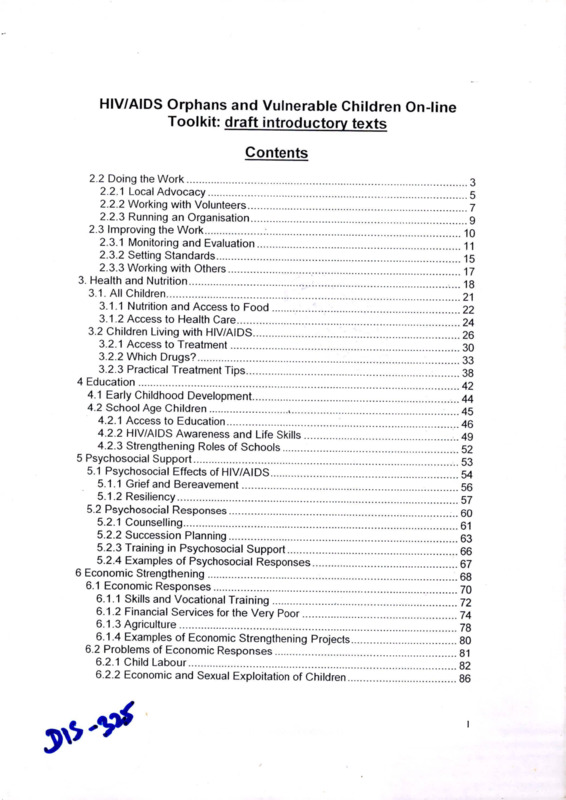

HIV/AIDS Orphans and Vulnerable Children On-line

Toolkit: draft introductory texts

Contents

2.2 Doing the Work........................................................

...3

2.2.1 Local Advocacy.................................................

...5

2.2.2 Working with Volunteers...................................

...7

2.2.3 Running an Organisation..................................

...9

2.3 Improving the Work.................... .............................

.10

2.3.1 Monitoring and Evaluation................................

.11

2.3.2 Setting Standards..............................................

. 15

2.3.3 Working with Others..........................................

.17

3. Health and Nutrition...................................

.18

3.1. All Children......................................................

.21

3.1.1 Nutrition and Access to Food..........................

.22

3.1.2 Access to Health Care......................................

.24

3.2 Children Living with HIV/AIDS................................. .26

3.2.1 Access to Treatment.........................................

.30

3.2.2 Which Drugs?....................................................

.33

3.2.3 Practical Treatment Tips...................................

.38

4 Education........................................................................

42

4.1 Early Childhood Development.................................

44

4.2 School Age Children.......................... .....................

45

4.2.1 Access to Education.........................................

46

4.2.2 HIV/AIDS Awareness and Life Skills................

49

4.2.3 Strengthening Roles of Schools.......................

52

5 Psychosocial Support......................................................

53

5.1 Psychosocial Effects of HIV/AIDS...........................

54

5.1.1 Grief and Bereavement.....................................

56

5.1.2 Resiliency...........................................................

57

5.2 Psychosocial Responses..........................................

60

5.2.1 Counselling.........................................................

61

5.2.2 Succession Planning.........................................

63

5.2.3 Training in Psychosocial Support.....................

66

5.2.4 Examples of Psychosocial Responses.............

67

6 Economic Strengthening.................................................

68

6.1 Economic Responses...............................................

70

6.1.1 Skills and Vocational Training.................... ......

72

6.1.2 Financial Services for the Very Poor................

74

6.1.3 Agriculture..........................................................

78

6.1.4 Examples of Economic Strengthening Projects

80

6.2 Problems of Economic Responses.........................

81

6.2.1 Child Labour.......................................................

82

6.2.2 Economic and Sexual Exploitation of Children.

86

i

87

r

7 Living Environments........................................................................

89

7.1 Carers

92

7.1.1 Older Carers.......................................................................

93

7.1.2 Child-Headed Households.................................................

96

7.2 Children Living Outside of Family Care...................................

97

7.2.1 Commercial Farms and Other Workplaces......................

100

7.2.2 Prisons and Detention Centres..........................................

101

7.2.3 The Street............................................................................

104

7.2.4 Situations of Conflict...................................... ....................

106

7.3 Alternates to Community Care in Extended Families.............

108

7.3.1 Placement of a Child with Another Family........................

109

7.3.3 Residential Care.................................................................

113

8. Children’s Rights.............................................................................

115

8.1 Participation...............................................................................

118

8.2 Stigma and Discrimination.............................................

121

8.3 Protection from Abuse, Exploitation, Neglect and Trafficking

123

8.4 Legal Support............................................................................

124

8.4.1 Birth Registration...............................................................

125

8.4.2 Inheritance.........................................................................

2

2.2 Doing the Work

This section provides practical tips for organizations carrying out activities aimed

at providing support to orphans and other vulnerable children. It focuses

particularly on the type of activities which might form part of a community-based,

‘orphan’ visiting programme.

Other sections look at related issues, such as how such programmes might get

started (Hyperlink Section: ‘Getting Started') or be improved (Hyperlink Section:

Improving the Work ). Others examine specific issues related to doing the work

in more detail, for example local advocacy (Hyperlink Subsection: Local

Advocacy ), working with volunteers (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working with

Volunteers’) and running an organization (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Running an

Organization’).

Key points about doing the work are:

1. Activities are most effective when they are carried out by individuals or

groups who are part of the local community. External organizations, such

as NGOs, need to play a facilitating role only.

2. Volunteers drawn from the local community constitute the most important

human resource in such programmes. Training, supporting and

motivating this group of people is animportant part of any programme.

(Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working with Volunteers’).

3. Projects will need to have a way of keeping records which helps monitor

activities of the programme as a whole and the situation of individual

children (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Monitoring and Evaluation’).

4. In situations of poverty, material support may be required by particular

children. However, there are many risks involved with this. Experience

has shown that material support is best provided through community

groups once they have demonstrated that they are able to prioritise

children in greatest needs and monitor activities, including the provision of

material support.

Visiting Orphans and Vulnerable Children

Many of the projects (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Project Case Studies’) which work

with orphans and vulnerable children have some kind of visiting programme at

their core. These usually work through a group of volunteers/mentors

(Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working with Volunteers’) who are selected from local

community members. These volunteers carry out a range of activities, which

may include:

»

»

Practical tasks, such as cleaning, washing, collection of firewood.

Counselling’ (Hyperlink Subsection. ‘Counselling ) - on issues including

.

.

bereavement and growing up

Teaching of skills, for example in home management

Psychosocial Support (Hyperlink Heading: ‘Psychosocial Support),

including showing love, spiritual support and teaching about culture and

Assessment of health and nutritional status (Hyperlink Heading. Health

and Nutrition ), including checking on immunizations, health card and

.

•

•

•

accompanying to clinic when ill

Ensuring that children attend school (Hyperlink Section: 'School Age

Children’) and that barriers to this are overcome

Providing support to caregivers (Hyperlink Section: Carers)

Prevention and detection of abuse (Hyperlink Section. 'Protection from abuse

etc.’)

Some organizations have developed frameworks for volunteers to operate within.

One of these is referred to as LEPO. It involves listening, encouraging, problemsolving and identifying other resources.

Some organizations conduct activities in addition to visiting orphans and

vulnerable children. In some situations, these activities are not linked to visiting

orphans and vulnerable children. These activities include:

•

•

•

•

Economic strengthening (Hyperlink Heading: Economic Strengthening )

Psychosocial support (Hyperlink Heading: Psychosocial Support)

Local advocacy (Hyperlink Subsection: Local Advocacy)

Protection from abuse (Hyperlink Section: ‘Protection from abuse etc.)

4

2.2.1 Local Advocacy

This section explores practical ways in which NGOs and CBOs might get

involved in advocating for children, particularly at local level. It also looks at the

issue of advocacy more broadly and briefly considers ways in which locallyfocused NGOs and CBOs can get involved in advocacy at national and

international levels.

Other sections looking at related issues include doing the work (Hyperlink

Section: Doing the Work’), working with volunteers (Hyperlink Subsection:

Working with Volunteers’) and running an organization (Hyperlink Subsection:

‘Running an Organization’).

Key points about local advocacy are:

1. Advocacy can be defined as pleading in support of others or speaking for

those who are powerless to speak for themselves.

2. The Convention on the Rights of the Child provides a powerful basis for

advocacy efforts at all levels (Hyperlink Heading: 'Children’s Rights’).

3. Many NGOs/CBOs find ‘advocacy’ difficult. However, local advocacy can be

started in a number of small practical ways, which are often simply an

extension of existing activities.

4. Locally-based NGOs/CBOs can often engage most effectively with advocacy

issues at national/international levels through involvement with networks and

coalitions.

What is Local Advocacy?

Advocacy has been defined as pleading in support of others or speaking for

those who are powerless to speak for themselves. Advocacy for orphans and

vulnerable children at local level might take a number of forms including:

•

Providing training about the rights of children (Hyperlink Heading:

‘Children’s Rights’), in general and the Convention on the Rights of the Child,

in particular. This training might be provided to community-based volunteers

working with orphans and vulnerable children and the children themselves.

•

Being aware of and focusing on children at particular risk.

•

Being careful to avoid terms (Hyperlink Section: ‘Terminology’) which

reinforce stigma (Hyperlink Section: ‘Stigma and Discrimination’), such as

AIDS orphans.

5

•

Using the law to protect the rights of children, for example on inheritance

(Hyperlink Subsection. Inheritance) of property.

•

Assisting children to get important documents, such as birth certificates

(Hyperlink Subsection: Birth Registration ).

•

Representing children’s interests in a variety of ways, including to social

workers, the police, courts, community leaders and to schools.

•

Assisting in a variety of ways to ensure that children gain access to important

services, such as health (Hyperlink Subsection: Access to Health Care’) and

education (Hyperlink Subsection: Access to Education ).

•

Using the media to disseminate information.

•

Linking to networks to participate in national and international advocacy.

6

2.2.2 Working with Volunteers

This section explores issues relating to ways in which NGOs and CBOs work

with community-based volunteers. Such people are often the key group in doing

work (Hyperlink Section: Doing the Work’) with orphans and vulnerable children

at community level. It looks at how these people are selected, trained and

supported.

Other sections looking at related issues include doing the work (Hyperlink

Section: ‘Doing the Work’), local advocacy (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Local

Advocacy ) and running an organization (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Running an

Organization’).

Key points about working with community volunteers are:

1. These volunteers should be selected by members of the local community

using a process and criteria agreed by the community.

2. Training should be relevant to the activities the volunteer is expected to carry

out and should be ongoing.

3. Ways need to be found to provide ongoing support and encouragement for

community-based volunteers. Initial training only is unlikely to be sufficient to

achieve this. Clear policies on ‘incentives’ for volunteers may need to be

developed.

4. In many projects, volunteers are mainly women. Ways need to be found to

mobilize men into these roles and to share the burden of care more equitably.

Visiting Orphans and Vulnerable Children

Many NGOs that work with orphans and vulnerable children do so by supporting

visiting programmes (Hyperlink Section: ‘Doing the Work’) which operate

through community-based volunteers. To get these programmes started

(Hyperlink Section: Getting Started’), such volunteers need to be selected. This

should be done by the local community using a process and criteria developed

by them. Examples of criteria for volunteers developed by one programme

include leading from the heart, people skills, ability to manage community

change, ability to be a role model and a sense of humour.

Training Volunteers

Many programmes conduct initial training for their community-based volunteers.

The precise content of this training varies but is likely to include training for what

the volunteer may need to do during a visit, sources of additional support and

7

record-keeping systems. Experience has shown that initial training alone is

unlikely to be sufficient, and that training needs to be ongoing.

Ongoing Support to Volunteers

A key element of working with volunteers involves supporting them in their work

on an ongoing basis. This support may take many forms and may include:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Ongoing training - this may include workshops, training elements in support

meetings and also exchange visits to other programmes

Support/supervision meetings

Feedback on individual and programme performance. This feedback may

come from various sources, including from inside and outside the local

community

Visits to the programme. These may be motivational, in that they give

recognition to the volunteers and the work they are doing. However, they can

be problematic particularly if the number of visits becomes excessive

Counselling and other supports to overcome problems of stress and burnout

Allowing volunteers to actively participate in programme development

Ensuring realistic workload, given that volunteers carry out programme

activities as volunteers, in addition to other responsibilities

Group identity - many volunteers gain support from religious bodies they

belong to

Material incentives - such as food, soap, T-shirts, shoes etc. This element is

potentially problematic because of the risk of creating dependency. Clear

guidelines may be helpful in this regard.

In many programmes, the majority of volunteers visiting orphans and vulnerable

children are women. This emphasizes the point that the burden of care which

results from HIV/AIDS is falling mainly on women.

8

2.2.3 Running an Organisation

In many cases community-based activities with orphans and vulnerable children

have not been started by an established organization but by an informal

community group or perhaps a church. In those cases, the people involved need

to learn a variety of skills, not only those specific to working with orphans and

vulnerable children, but also more general skills related to running a project, and

setting up an organization. Although this section contains some resources which

refer to these issues, many more resources are available in the International

HIV/AIDS Alliance’s NGQ/CBQ Support Toolkit (Hyperlink Toolkit).

Other sections looking at related issues include doing the work (Hyperlink

Section: ‘Doing the Work’), local advocacy (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Local

Advocacy’) and working with volunteers (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working with

Volunteers’).

9

2.3 Improving the Work

This section looks at ways in which activities being carried out with orphans and

vulnerable children can be improved and strengthened. This is an essential part

of running a programme (Hyperlink Heading: Running a Programme) once it

has been started (Hyperlink Section: 'Getting Started) and some work is

already being done (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Doing the Work’). Three essentia

elements are considered here, namely monitoring and

(^r"nk

Subsection: 'Monitoring and Evaluation'), work.ng with ?th^g (Hyperlmk

Subsection: ‘Working with Others’) and setting standards (Hyperlink

Subsection: ‘Setting Standards').

Key points about improving the work are:

Monitoring and evaluation (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Monitoring and

1. Evaluation^) of a project helps establish what has been achieved, including

what has worked well and what could be better. Learning from such

activities can be valuable in improving work.

NGOs can work with others (Hyperlink Subsection: Doing the Work) in

2. a variety of ways, including through formal and informal networks and w th

implementing joint projects. This contact with other organizations local y,

nationally and internationally can be a useful way of learning about other

approaches which can be used to improve activities.

3. Setting standards (Hyperlink Subsection: Setting

reached in the provision of care for children can be useful for monitoring

and evaluation (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Monitoring and Evaluation )

purposes, and for comparing different projects and approaches^ Sue

standards can be used by organizations as targets to aim for. This is

likely to improve the quality of work being carried out.

10

2.3.1 Monitoring and Evaluation

This section looks at the monitoring and evaluation of programmes. This is an

essential part of improving work (Hyperlink Section: ‘Improving the Work1).

Related sections include working with others (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working

with Others’) and setting standards (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Setting Standards’).

Key points about monitoring and evaluation are:

1. Both monitoring and evaluation are processes used to assess project

progress.

2. ‘Monitoring’ refers to an ongoing system used to keep the project ‘on

track’.

3. ‘Evaluation’ refers to a one-off event conducted to account for resources

used and/or to document lessons learned.

4. There are two main approaches to evaluations. Scientific approaches

emphasise the importance of objective facts/evidence. Interpretive

approaches emphasis the views and perspectives of people affected

by/involved with the project. These people are termed ‘stakeholders’.

5. Many approaches to evaluation now'emphasise the active participation of

stakeholders, particularly children and young people. Different

stakeholders may have very different levels of power within a project.

6. Indicators are things which are used to measure or assess progress made

by a project. They may be expressed as numbers (quantitative) or

descriptive words (qualitative). They may be internationally or locallydefined and can be used to measure project activities at different levels,

for example processes/activities and outcomes/impacts

7. Good monitoring systems and evaluation approaches collect and compare

information from a variety of different sources using different methods.

This is termed triangulation.

Defining Monitoring and Evaluation

Resources in this section contain a number of definitions of the terms ‘monitoring’

and ‘evaluation’. These two processes both seek to examine and analyse the

progress of a particular project. They differ from each other in three main ways:

ll

1. Nature: The term monitoring is used to describe a system of collecting

and analyzing information about the work of the project. On the other

hand, the term evaluation is usually used to describe a specific event.

2. Timing: Monitoring is a regular and ongoing process which takes place

throughout the life of a project. An evaluation usually occurs at a

particular time, for example midway through a project or at the end.

3. Purpose: The purpose of monitoring is relatively narrow, in that it usually

focuses on keeping a project ‘on track’. This involves measuring what the

project has done and comparing this with its plans. Evaluation may have

broader purposes, for example assessing what has been learned as a

result of project activities.

Purpose of Evaluation

Two main purposes can be identified for conducting an evaluation. First, an

evaluation can be conducted to hold a project accountable for what it has done

and achieved. In such cases, actual project activities and achievements will be

compared with what was planned. Such evaluations are often required by donor

organizations that provide funds for a project. The receipt of further funds may

depend on achieving a satisfactory outcome to such an evaluation. Secondly, an

evaluation may seek to learn lessons from project activities. This is likely to

include an assessment of what worked well and what didn’t. Things that have

worked well may be referred to as ‘good’, ‘effective’ or ‘best’ practice. There is a

tension between these two purposes. For example, this may explain the reason

why ‘negative’ findings, that is what didn’t work, are rarely recorded in evaluation

reports. Although such findings are very useful for the purpose of learning, they

are problematic in terms of accountability, because donors are unlikely to be

willing to fund activities shown to be ineffective. Consequently, organizations

may not wish to publicise findings of this nature.

Ways of Conducting Evaluations.

There are a variety of ways of conducting evaluations. These can be divided into

two main types. The ‘scientific’ approach seeks to compare a group of people

receiving a particular intervention or service with a comparable group who do not

receive it. The purest form of this is referred to as a randomized, controlled trial.

It places strong emphasis on objective facts/evidence. On the other hand, the

‘interpretive’ approach places much greater emphasis on trying to understand the

views and perspectives of different individuals and groups associated with the

project.

Stakeholders

12

People associated with the project can be referred to as ‘stakeholders’. Many

different stakeholder groups can be identified for a particular project, including

the children and young people who are intended to benefit from it. These

stakeholders may have very different expectations of a project evaluation. Two

key issues relating to stakeholders and evaluation are:

1

Power: There may be power imbalances between different groups of

stakeholders. For example, donor views may be given greater weight

within an evaluation because they control project funds.

2. Participation: Interpretive approaches to evaluation place great emphasis

on the active participation of project stakeholders, particularly children and

young people, in an evaluation.

Indicators

Indicators are widely used in both monitoring and evaluation. Essentially, they

are things which can be measured or assessed to see the progress being made

by a project. They may be expressed in numbers (quantitative) or through

descriptive words (qualitative). They may form part of an international set of core

indicators or may be developed locally for a specific project. They may measure

different ‘levels’ of a project. These levels include:

•

Inputs - that is the things needed for the project to occur. An example of an

indicator of project inputs is project cost*

•

Processes - that is the activities of a project. In general, these are relatively

easy to measure and process indicators often form the bulk of monitoring

systems. An example of a process indicator would be the number of orphans

and vulnerable children visited by volunteers. In some situations, these

figures are expressed as the percentage of people who need a service who

actually receive it. This is termed ‘coverage’.

•

Outputs - that is things produced by the project, for example an upgraded

health facility.

•

Impact/Outcome - these are longer-term changes produced as a result of

the project. In many cases, it may be difficult to show clearly that these

changes have occurred as a result of the project because they are affected by

many other things. An example of an impact indicator might be children’s

nutritional status.

Some examples of process and outcome indicators used by programmes

working with orphans and vulnerable children are presented in the table below.

Process Indicators

Outcome Indicators

13

| Number of children assisted by the

programme

Number of community-based

volunteers (Hyperlink Subsection:

Working with Volunteers') within a

programme

Production of community-generated

financial and material resources

(Hyperlink Heading: ‘Economic

Strengthening’)

Number of volunteer training sessions

Number of supervisory visits carried

out by senior staff

Prevalence of abandoned

children/street children (Hyperlink

Subsection: The Street )/child-headed

households (Hyperlink Subsection.

‘Child-headed Households’)

Stunting and wasting

Dietary intake profile

School enrolment/drop-out

Immunisation status

Proportion of sibling separation

Primary carer income

Household land cultivation

Monitoring and Evaluation Methods

a

Monitoring and evaluation may use a variety or different methods for collecting

information. Primary methods are those used by the people doing the

monitoring/evaluation. Primary methods may include questionnaires, surveys,

focuse group discussions, direct observation and interviews with key informants

Secondary methods involve looking at work done by other people, usually

through reviewing project and other documents. Good quality monitoring and

evaluation uses information from a variety of different sources, collected using

different methods to cross-check its validity. This is called triangulation.

14

2.3.2 Setting Standards

This section looks at setting standards for activities which seek to provide care

and support for orphans and vulnerable children. It is part of improving work

(Hyperlink Section: 'Improving the Work ). Related sections include working

with others (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working with Others’) and monitoring and

evaluation (Hyperlink Subsection: 'Monitoring and Evaluation ).

Key points about setting standards are:

1. Standards can be used by an individual project/programme to assess their

own achievements and to have something to aim for

2. Standards can be used to compare different approaches. This may be

particularly important when trying to assess costs.

3. Standards can be set in a number of areas where children have needs/rights.

These include survival, security, socialization and self-actualisation.

Why are Standards Needed?

Organizations have very varied ways of working with orphans and other

vulnerable children. It may be extremely difficult to assess the relative

effectiveness of these approaches unless there are agreed standards for the kind

of care that needs to be provided. Such standards may be useful for individual

projects who can use them to assess how they are doing and as targets for

improved activities in the future. Also, such standards can allow comparisons to

be made between different project approaches. However, many of the standards

are affected by poverty in general. It may be necessary for communities to adapt

these standards so that they are appropriate for local settings.

Areas in which Standards are Useful

One approach is to identify four areas in which standards are needed. These

are:

1. Survival: This area covers a number of basic physical needs that children

have in order to survive. These include food, clothing, home environment,

hygiene/infection control, treatment and health care. It is possible to set

standards in each of these areas. For example, in South Africa under

‘food’, two standards were adopted, namely that children should receive

three meals per day and should be involved in food preparation and

choice.

15

2. Security: This area covers a child’s need for both protection and affection.

Areas in which children need protection include from abuse (Hypenink

Section: Protection from abuse.. ), stigma and discrimination

(Hyperlink Section: Stigma and Discrimination ) and from loss of parental

assets (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Inheritance’).

3. Socialisation: This covers a range of needs and rights children have in

relation to interaction with others. These areas include the right to their

own identity,; education/schooling (Hyperlink Heading: ‘Education’);

participation (Hyperlink Section: ‘Participation ), understanding,

information and communication and counseling/supportive services

(Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Counseling’).

4. Self-actualisation: This area covers a child’s need for recreation/idleness

and freedom of expression.

16

2.3.3 Working with Others

This section looks at ways in which organisations can work with other groups

conducting activities aimed at orphans and vulnerable children. It is part of

improving work (Hyperlink Section: Improving the Work’). Related sections

include working with volunteers (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Working with

Volunteers’) and monitoring and evaluation (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Monitoring

and Evaluation’).

Key points about working with others are:

1. Links to other organisations can be very useful in learning about what others

are doing. This can be extremely helpful in improving practice.

2. Working with others may take many forms. It may consist of informal

linkages, official networks and formal partnerships

Reasons for Working with Others

Organisations often find it useful to develop linkages with other organizations.

Reasons for this vary. First, it provides organisations with ways of sharing

information about what they are doing and learning about what others are doing.

This may be done in a number of different ways including electronic and print

media, meetings and site visits. Such learhing can be helpful in improving an

organisation’s work. In addition, such linkages provide encouragement for staff

and volunteers in organizations who often feel they are working in isolation.

They also provide opportunity for organisations to work constructively together.

Such joint working may result in improved services for orphans and vulnerable

children.

Types of Relationships between Organisations

Relationships between organisations take many forms. These include:

•

•

•

Informal links — such as exchange visits for staff and volunteers

Formal networks - such as the Children in Need Network (CHIN) in Zambia

Formal partnerships - where two or more organisations agree to work

together on a particular activity

I7

3. Health and Nutrition

This section looks at the health and nutrition of orphans and vulnerable children.

It looks at ways in which the effects of HIV/AIDS on the health and nutrition of

children can be measured and the ways in which HIV/AIDS causes its effects on

the health and nutrition of orphans and vulnerable children. It also looks at what

rights (Hyperlink Heading: ’Children’s Rights') orphans and vulnerable children

have regarding health and nutrition and what actions can be taken to improve

their health and nutrition. Other sections look in more detail at health and

nutrition of orphans and vulnerable children, in general, (Hyperlink section.

All Children’) and children living with HIV/AIDS (Hyperlink Section: Children

living with HIV/AIDS'), in particular.

Key points about health and nutrition are:

1.

HIV/AIDS is having severe effects on the health and nutrition of children. In

countries with severe HIV/AIDS epidemics, this is seen in increasing rates of

under 5 mortality.

2. HIV/AIDS affects the health of children directly and indirectly.

3. It is possible to approach this issue by considering the rights (Hyperlink

Heading: 'Children’s Rights') that children have regarding health, and

examining how these rights are abused in relation to HIV/AIDS.

4. Ways in which the effects of HIV/AIDS on the health of children can be

reduced include effective HIV prevention; health education for children and

caregivers; strengthening nutrition (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Nutrition and

Access to Food ) and food production; and improving access to health

services (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Access to Health Care') in general and

antiretrovirals (Hyperlink Subsection: “Access to Treatment’), in particular.

r

Effects of HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS is having severe effects on the health and nutrition of children. In

countries with severe HIV/AIDS epidemics, this is seen in increasing rates of

under 5 mortality. In some other countries, with lower rates of infection, under 5

mortality rates have either not risen or fallen as a result of other factors.

HIV/AIDS affects the health-of children in a number of different ways including.

.

Directly, when children themselves are infected with HIV (Hyperlink

Section: ‘Children living with HIV/AIDS’).

•

By making children more vulnerable to other infections. For example,

children, in general, are more vulnerable-to tuberculosis as a result of

IS

HIV/AIDS because of greater exposure to the disease. Children living with

HIV/AIDS are more vulnerable to tuberculosis because of reduced immunity

•

Through the impoverishing effects of HIV/AIDS. One of the impacts of

HIV/AIDS on children, their families and communities is worsening poverty

(Hyperlink Section: 'Situation'). This affects the health and nutrition of

children in a number of ways. Families are less able to afford health care and

other measures to prevent disease, such as the purchase of mosquito nets.

In addition, poor people often have poorer nutrition, housing, hygiene and

water. All these have effects on the health of children.

•

Orphans and vulnerable children are more likely to be involved in work. Such

child labour (Hyperlink Section: 'Child Labour’) is often unregulated and may

expose them to a variety of hazards, including chemicals and pesticides.

•

Orphans and vulnerable children may be less able to access health care

(Hyperlink Section: Access to Health Care ) than other children due to a

variety of reasons.

•

HIV/AIDS has reduced the ability of health systems to cope and deliver

services. This is because of the increased demand for services as a result of

HIV/AIDS and the reduced ability to deliver services because of illness and

death of health personnel.

•

HIV/AIDS has negative effects on the gtowth and development of children.

Causes of this include poverty and illness of the parent and/or the child.

Children’s Health Rights

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (Hyperlink Heading: 'Children's

Rights’) includes specific rights regarding health. Examples of these include the

right to medical confidentiality, the right to informed consent and the right to

access to basic health care services. In many situations, orphans and vulnerable

children do not enjoy the benefits of these rights.

Reducing the Effects of HIV/AIDS on Children’s Health

There are many different ways in which the effects of HIV/AIDS on the health of

children can be reduced. These include:

•

By promoting effective methods to prevent the further spread of HIV/AIDS.

•

Through health education of children and their caregivers.

•

Through a variety of measures which make health services more

accessible (Hyperlink Section: 'Access to Health Care’) and appropriate for

19

children Provision of effective health services for children's caregivers will

also have effects on the health of children.

•

Improving access to treatment with antiretroviral drugs (Hyperlink

Subsection: Access to Treatment').

•

Steps to improve children’s nutrition, including initiatives to strengthen

household food production.

20

3.1. All Children

This section looks at issues which affect the health and nutrition (3) of all

orphans and vulnerable children. This is distinct from issues affecting children

living with HIV/AIDS (3.2). More details are available in other sections on

nutrition (3.1.1) and access to health care (3.1.2).

Key points about health and nutrition (3) are:

1. HIV/AIDS is having severe effects on the health and nutrition of children. In

countries with severe HIV/AIDS epidemics, this is seen in increasing rates of

under 5 mortality.

2. HIV/AIDS affects the health of children directly and indirectly.

3. It is possible to approach this issue by considering the rights (Hyperlink

Heading: ‘Children’s Rights’) that children have regarding health, and

examining how these rights are abused in relation to HIV/AIDS.

4. Ways in which the effects of HIV/AIDS on the health of children can be

reduced include effective HIV prevention; health education for children and

caregivers; strengthening nutrition (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Nutrition and

Access to Food’) and food production; and improving access to health

services (Hyperlink Subsection: ‘Access to Health Care ) in general and

antiretrovirals (Hyperlink Subsection: Access to Treatment ), in particular.

More details on these key points are available in the section on health and

nutrition (3).

Research from Zambia has shown that some children orphaned by HIV/AIDS are

more at risk of problems with health and nutrition than others:

•

Younger children are more at risk than older children.

•

Children living in large families in rural areas are more at risk than those in

smaller families. This may not be true in urban areas.

•

Children in poor families are more at risk.

•

Paternal orphans living with their mother are more at risk of health problems

than maternal orphans living with their father. This stresses the need to

consider paternal orphans (1.1) when working with orphans and vulnerable

children.

21

3.1.1 Nutrition and Access to Food

This section looks at issues which affect the nutrition of orphans and vulnerable

children and their access to food. Other sections cover general issues of health

and nutrition (3.1) and details of access to health care (3.1 2)

Key points about nutrition are:

8. Good nutrition is essential for the physical growth and development of

children. It is also necessary for full development of their immune system.

9. Certain groups of children are particularly vulnerable to nutrition problems.

These include young children (3.1) and children living with HIV/AIDS

(3.2).

”

10. Children’s need for good nutrition starts before they are born. Children of

different ages have different nutritional needs.

11. HIV is known to be transmitted from mother to child through breastfeeding.

However, children are more at risk of other infections if they do not breast

feed. Things to consider when a woman decides how to feed her baby

include whether or not she knows her HIV status and whether or not she is

able to safely feed her baby in another way.

Good nutrition is essential for the physical growth and development of children. It

is also necessary for full development of their immune system.

Certain groups of children are particularly vulnerable to nutrition problems.

These include young children (3.1) and children living with HIV/AIDS (3.2)

Children’s need for good nutrition starts before they are born. Children of

different ages have different nutritional needs. Young children are particularly at

risk of problems with nutrition. For this reason, many of the documents focus on

the nutrition of children under the age of five years. These children can also be

broken down into groups, 0-6 months, 6-11 months, 12-23 months and 24

months to 5 years.

Issues to consider in the nutrition of children under the age of 5 include:

•

The role of breastfeeding. It is well-known that breastfeeding is very good

for children. It protects them against many diseases and greatly increases

their chances of survival. However, it is known that breast milk can transmit

HIV. Deciding on how to feed an infant can be very difficult for women

because of HIV. This choice will depend on whether the woman knows if she

is HIV positive and whether or not she can safely feed her baby in another

22

way. Policy principles on infant feeding (0000175e00) were agreed by

leading UN agencies in 2002. Approaches to infant feeding form an important

part of measures to prevent mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV.

However, there are other important steps which need to be taken, including

preventing HIV infection in women, preventing unintended pregnancy and

providing long-term support to women.

•

Other foods. Children need other foods apart from breast milk from the age

of 3-6 months. There is some evidence that exclusive breastfeeding before

that time reduces the risk of transmission of HIV from an HIV positive mother.

Children need a range of nutrients including those which provide energy and

a range of ‘micronutrients’. Important micronutrients include vitamin A, iron

and vitamin C.

•

Feeding practices can affect whether or not a child is well-nourished. A

child should be provided with food they can digest on their own plate. Good

hygiene is very important when preparing food for children. Particular care is

needed to ensure that a child continues to receive nutrients when they are ill.

•

Access to food. Many documents which talk about nutrition of children

overlook a key problem. Many families do not have enough food throughout

the year. They do not always have the right kinds of food. Ensuring children

and families have enough food is important to ensure that orphans and

vulnerable children are well-nourished. Community grain banks are one way

in which communities can provide ‘safety nets’ for vulnerable children.

2.3

3.1.2 Access to Health Care

from accessing education (4 2 1).

Key barriers to access to

health care for orphans and vulnerable children are.

1. Lack of money

2.

Distance to the health facility and availability of transport

3. Lack of time to seek health care

4. Negative

attitudes and limited skills of some health workers

5. Lack of a family care giver

6.

Lack of health knowledge among children and care givers

Money

Lack of money is a major reason why

SaSfhX^X^^iSS^ayiose income

if they spend time seeking health care.

Distance to Health Facilities

EsSSsSjSBSsS

a barrier.

Time

them taking a child to the health centre.

Health Workers

24

Children and their care givers may not use health services because they fear

they will not be treated well by health workers. This may be because of negative

attitudes among health workers. Health workers may also lack skills to deal

effectively with orphans and vulnerable children. In some cases, people with HIV

are not given treatment or are given a lower standard of treatment. There may

also be fears that information about health will not remain confidential or that they

will have to explain frequent trips for health care.

Care Givers

There may be other reasons why a parent or other adult care giver is unable to

take a child for health care. For example, they may be ill themselves and unable

to do this. Children in child-headed households (7.1.2) may have no adult to

take them for health care. In some cases, adults may feel it is not worth spending

time and resources on health care for children, particularly if they have HIV. Also,

some adult guardians may prioritise the needs of their own child rather than

others that they care for.

Knowledge

Care givers may lack the skills and knowledge on health issues. For example,

they may not know when to take a child to a health centre. This may be a

particular problem when the care giver is a grandparent or older child because

much health education about children is targeted at mothers.

25

3.2 Children Living with HIV/AIDS

This section looks at health and nutrition issues which particularly affect children

living with HIV/AIDS. More general issues of health and nutrition (3) and how

they affect all orphans and vulnerable children (3.1) are covered in other

sections. Other sections give more details on access to antiretroviral treatment

(3.2.1) in children, which drugs to use (3.2.2) in children and practical tips

(3.2.3) on how to give such treatment in children.

Key points about the health and nutrition of children living with HIV/AIDS are:

1. UNAIDS estimates that 1500 children per day are being infected with HIV

globally.

2. Most HIV infection in children occurs through mother to child transmission

(MTCT). Other routes of infection include through sexual activity and unsafe

health practices.

3. It is difficult to test children under the age of 15-18 months for HIV. Children

born to HIV positive women have HIV antibodies from their mother in their

blood until this age.

4. HIV has serious effects on the health of children. They often grow poorly and

are more at risk of infectious diseases. These are often more severe than in

other children.

5. Without treatment, 60-75% of children with HIV die before the age of five

years. With effective antiretroviral treatment, this figure can be reduced below

20%.

6. Children with HIV have a range of health needs in addition to access to

antiretroviral treatment. These include immunization and prevention and early

treatment of all infections.

In this section, the term children living with HIV/AIDS is used to mean HIV

positive children. However, some documents use the term more broadly to

describe all children (3.1) who are affected by HIV/AIDS.

UNAIDS estimates that 1500 children per day are being infected with HIV

globally.

Routes of Transmission

Most HIV infection in children occurs through mother to child transmission

(MTCT). This can occur during pregnancy, at the time of birth or through

26

breastfeeding (3.1.1). In developing countries, approximately one in every three

children born to an HIV positive mother is themselves infected with HIV. In

developed countries, less than one child in fifty born to an HIV positive mother is

themselves infected. This is because of health practices including delivery by

Caesarean Section, treatment with antiretroviral drugs and safe alternatives to

breastfeeding. Children may also be infected with HIV through sex and unsafe

health practices. Sexual spread of HIV (4.2.2) is most common in older children

but can occur in younger children through sexual abuse (8.3). Unsafe health

practices include use of non-sterile needles and unsafe blood products. These

practices may also occur in the traditional health sector and include activities

such as circumcision and ear piercing.

HIV Testing in Children

It is difficult to test children under the age of 15-18 months for HIV. Standard HIV

tests detect antibodies to HIV. Children born to HIV positive women have HIV

antibodies from their mother in their blood until this age. These are called

maternal antibodies. In some cases, these maternal antibodies are found in the

blood of children aged more than 18 months. It is possible to detect HIV directly.

However, these tests are very expensive and not widely available in developing

countries. The test used is the HIV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In the

United States, children born to HIV positive mothers receive PCR tests at birth

and again at 1-2 months and at 4-6 months. Two positive tests are taken as

evidence of HIV infection. Two negative tests are evidence that the child does

not have HIV infection. This can be confirmed using standard HIV antibody tests,

which become negative after the age of about 18 months.

There are many issues to consider before testing a child for HIV:

•

HIV testing should only be carried out if it brings some clear benefit to the

child. For example, this might be if it results in better care and support.

•

Counselling needs to be provided for children and their care givers. The

counseling provided should be appropriate for the age of the child.

•

HIV testing needs to be carried out in a way which ensures that results are

kept confidential.

It is also possible to decide how severe a child’s HIV infection is. This is done by

assessing two factors:

• Symptoms: The presence and severity of symptoms can be used to assess

how severe a child’s infection is.

• CD4 count: CD4 cells are a particular type of white blood cell. They form part

of the body’s immune system. Tests which count these can show how well

27

the immune system is working. In children, age-adjusted tables need to be

used for assessing CD4 counts. This is because there are more CD4 cells in

the body at birth. These levels fall during childhood to reach adult levels at

about 13 years of age.

Effects of HIV Infection on Children

HIV infection affects children in a number of ways:

•

Children with HIV infection often fail to grow properly. This is sometimes

referred to as failure to thrive.

•

Children with HIV infection are more frequently affected by infectious

diseases. These are often more severe than in other children.

•

Without treatment, 60-75% of children with HIV die before the age of 5 years.

With treatment with antiretroviral drugs (3.2.1), this figure can be reduced to

about 20%.

•

Children with HIV often face stigma and discrimination (8.2) as a result of

their infection.

Other routes of infection include through sexual activity and unsafe health

practices.

Health Needs of Children Living with HIV

Children with HIV have a variety of health needs. These include:

•

Treatment (3.2.1) of their HIV infection.

•

Medicines which can prevent common infections occurring. This is called

prophylaxis.

•

Early and effective treatment of common infections.

•

Immunisation. Children with HIV/AIDS should receive immunizations in the

same way as other children. These help protect the child against infectious

diseases.

•

Good nutrition

•

Good hygiene

•

A balance between exercise and rest

28

•

Psychosocial Support

including care, comfort and counselling

29

3.2.1 Access to Treatment

This section looks at issues concerning the access of children with HIV (3.2) to

effective treatment. Other sections look at which antiretroviral drugs (3.2.2)

should be used and provide practical treatment tips (3.2.3).

Key points about access to treatment for HIV are:

1. Effective antiretroviral drugs have been available since 1996. Using several of

these drugs together in combination has greatly increased survival of people

with HIV in developed countries.

2. It is estimated that more than 6 million people in developing countries need

antiretroviral treatment. However, only around 230 000 people receive this

treatment.

3. One of the main barriers to treatment has been its cost. This has been

particularly high because of the high costs of the drugs and the fact that a

person needs to take several of these over a long period. However, prices of

antiretroviral drugs have fallen dramatically since 2000.

4. There are other barriers to treatment in developing countries. These include

the lack of sufficient health infrastructure, lack of sufficient trained staff and

lack of national policies which promote antiretroviral treatment from a public

health approach.

Access to Antiretroviral Drugs

Effective antiretroviral drugs have been available since 1996. Using several of

these drugs together in combination has greatly increased survival of people with

HIV in developed countries. These drugs do not ‘cure’ HIV. They do control the

disease which means that people living with HIV live longer and have a better

quality of life. They do have to be taken for life and can have severe side-effects.

Unfortunately, very few people in developing countries currently receive these

drugs. It is estimated that more than 6 million people in developing countries

need antiretroviral treatment. However, only around 230 000 people receive this

treatment. Most of these live in one country, Brazil. The World Health

Organisation has set a target that more than 3 million people in developing

countries should be receiving these drugs by 2005.

Barriers to Access - Cost

The main barrier to access to this treatment has been its cost. This was

estimated at $10-15 000 per year. This was not only because of the high cost of

30

the drugs but also because a person needs to take more than one drug for a long

period. However, drug prices have fallen dramatically since 2000. Treatment may

now cost as little as $350 per year. This has occurred for several reasons. These

include:

•

Generic Production - Many of the antiretroviral drugs that are available are

produced by drug companies. These companies seek to protect their new

drugs through a system of ‘patents’. These patents are laws which prevent

other companies ‘copying’ the drug. Drugs protected by patents are

sometimes called proprietary drugs. Drugs that are not protected by patents

are called ‘generic’. Some countries (Brazil, India, Thailand) have produced

‘generic’ versions of antiretroviral drugs at much lower prices than the

proprietary drugs. As a result of this competition, drug companies have

greatly reduced prices of their proprietary drugs.

•

Differential Pricing/Discounting - This involves companies selling their

drugs at a lower price in developing countries than in developed ones. This

only works if the markets can be kept separate. It relies on the good will of

drug companies. They may only agree to this if countries agree to stricter

rules on patents and other forms of ‘intellectual protection’.

•

TRIPS Safeguards - TRIPS (Trade-related aspects of Intellectual Property

Rights) is one of the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Its aim is

to ensure that rules on intellectual property rights are applied throughout the

world. Many countries are currently able to produce and use generic

antiretroviral drugs because their national laws do not recognise patents on

these drugs. There is international pressure for countries to adopt the

provisions of TRIPS which would make these patents apply in all countries.

However, TRIPS allows for countries to overrule these patents when it is

needed to promote ‘public health’. This can be done through ‘compulsory

licencing’ which allows a country to make or buy a generic version of a

proprietary drug when it is needed for public health reasons. Buying such a

generic drug from another country is called ‘parallel importing’.

•

Regional/lnternational Procurement - Drug costs can be reduced when

they are purchased in bulk. This can be done where countries purchase

jointly with other countries in their region. International arrangements have

been used for other medicines, such as vaccines. Currently, there is no

international system for purchasing antiretroviral drugs.

•

Local Production through Voluntary Licencing - This involves a country

and a drug company agreeing to allow the drug to be manufactured in that

country. This will require the transfer of technology from the drug company to

the country.

31

Drug Donations - These may improve short-term access to a drug

However, they may hinder changes needed to ensure these drugs remain

available over time. They may stop countries producing their own medicines.

In addition, such donations usually only benefit a few people in a few

countries.

•

Other Barriers to Access

Other major barriers to access to antiretroviral drugs include the lack of health

infrastructure and adequately trained staff in developing countries. This is

particularly important with antiretroviral drugs because they are complex and

difficult to take, it is difficult to select and monitor patients and there is a risk of

resistance developing.

One major part of health infrastructure is the availability of laboratory facilities.

The World Health Organisation has identified four levels of such facilities

minimum, basic, desirable and optional. The minimum level requires the ability to

measure haemoglobin and to test for HIV antibodies. Currently, only the

minimum level is required to be able to start antiretroviral treatment programmes.

Expanding Access to Treatment

The following steps will be helpful in expanding treatment with antiretroviral

drugs:

•

Starting small and gradually expanding.

•

Securing additional resources so that funds are not diverted away from other

parts of the health service.

•

Adopting national policies which have a public health approach. These

include having an agreed, simplified first line treatment regime and ensuring a

continuous drug supply.

•

Training health staff at all levels in how to provide this treatment.

•

Ensuring that work is carried out in both public and private sectors.

•

Developing a national system for monitoring drug resistance.

32

/•

lli-'(

K-'

- SOCHATA

KoTaniBngala

kot a > n<)>’ I a

-------- -r-

/ i j)

3.2.2 Which Drugs?

This section looks at issues affecting the choice of antiretroviral drugs to treat

children with HIV (3.2). Other sections look at general issues regarding access

to treatment (3.2.1) and provide practical treatment tips (3.2 3).

Key points about choosing antiretroviral drugs in children are:

1. There are many differences between children and adults regarding HIV

infection and its treatment. Evidence is unclear about whether treatment of

HIV in children is as effective as in adults.

2. Recommendations about when to start treatment differ between the United

States and Europe. World Health Organisation guidelines for developing

countries broadly follow European guidelines.

3. There are very many different antiretroviral drugs available. They are in three

main categories - Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs), NonNucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) and Protease

Inhibitors (Pls).

4. All treatment plans now use a combination of at least three drugs. These

usually include two NRTIs and one from another group.

5. A wide range of issues need to be considered when deciding which drugs to

use. Some of these are general while others apply particularly to children. It is

helpful if a country has one combination of drugs which it uses for first treating

people with HIV. This is called the primary regime. Other drug combinations

may be needed for people who experience side-effects or do not respond to

the primary treatment. These combinations are called secondary regimes.

6. Dosages for children are calculated either based on the surface area of a

child or its weight. Special formulations of drugs are needed for children.

Breaking tablets for children is not recommended.

7. Children who have TB should usually complete their TB treatment before

starting treatment with antiretroviral drugs.

8. Cotrimoxazole should be given to all children born to HIV positive mothers in

the first 6-12 months of life. This is to prevent pneumocystis pneumonia.

Differences between Adults and Children

There are many differences between children and adults regarding HIV infection

and its treatment. Diagnosis of HIV infection is difficult in children under 18

months of age. This is because they still have antibodies from their mother

(3.2) in their blood. It may be more difficult to measure disease progress in

children using laboratory tests. This is because levels of viral load and CD4 cells

are very different in children as compared to adults. Some studies have

suggested that treatment of HIV in children is less effective than in adults. Other

studies have shown that treatment of children is just as effective as in adults.

This means that the current position is unclear.

When to Start Treatment

Recommendations about when to start treatment differ between the United

States and Europe. World Health Organisation guidelines for developing

countries broadly follow European guidelines. These are shown in the table

below:

WHO Staging System

Child under 18

months of age who

has had HIV infection

confirmed by

laboratory test (PCR)

WHO stage III

disease OR

WHO stage I or II

disease with a CD4

percentage <20%

Child under 18

months of age who

has not had HIV

infection confirmed by

laboratory test (PCR)

WHO stage III

disease and CD4

percentage <20%

Child over the age of

18 months who has a

positive HIV antibody

test

WHO stage III

disease OR

WHO stage I or II

disease with a CD4

percentage <15%

Stage I - Asymptomatic or

generalised

lymphadenopathy

Stage II - Unexplained,

chronic diarrhea; severe or

persistent candidiasis

outside the neonatal

period; weight loss or

failure to thrive; persistent

fever or recurrent severe

bacterial infections

Stage III - AIDS-defining

opportunistic infections,

severe failure to thrive,

progressive

encephalopathy,

malignancy or recurrent

septicaemia/meningitis

In practice, this means that different approaches are needed depending on

whether the child is over the age of 18 months. Under that age, it will probably

not be possible to be sure that the child has HIV infection. In that case, treatment

is only recommended for those who are very ill (stage III) and have evidence of

damage to their immune system (CD4percentage <20%). If the child is over the

age of 18 months, treatment should only be given to children who have had a

positive antibody test. It can then be given to all those who are very ill (stage III)

34

and those who are less ill (stages I and II) but have evidence of a damaged

immune system (CD4 percentage <15%).

Drug Types and Names

There are so many different antiretroviral drugs available that it can be very

difficult to understand articles which describe ways in which they are use.

Antiretroviral drugs have a variety of names:

• Trade or Proprietary Name: This is the name given to a particular version of

a drug produced by a particular company. These names should not be used

when describing or prescribing drugs. Some tablets contain more than one

active drug. These drugs are often known by their trade names but it is better

to describe them using their generic names or abbreviations.

• Generic Name: This is the name of the drug which is used by everyone that

makes it. This is the name that should be used when describing the drug.

• Abbreviations: The generic names of most antiretroviral drugs are very long

This makes them hard to remember and use. Most of them have been given

abbreviations which are made up of three letters or numbers. Some have

more than one abbreviation. For example, AZT and ZDV both refer to

Zidovudine.

Antiretroviral drugs can be grouped into three main types according to how they

work. There are Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs), NonNucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) and Protease Inhibitors

(Pls). A table showing the names of drugs in these categories is shown below:

NRTIs

Pis

NNRTIs

Zidovudine (AZT/ZDV)

Didanosine (ddl)

Stavudine (d4T)

Lamivudine (3TC)

Zalcitabine (ddC)

Ritonavir

Nelfinavir (NFV)

Amprenavir

Lopinavir (LPV)

Indinavir (IDV)

Saquinavir (SQV)

Nevirapine (NVP)

Efavirenz (EFZ)

Abacavir (ABC) (In some papers this is

grouped with NRTIs)

Delavirdine

35

Combination Therapies

All treatment plans now use a combination of at least three drugs. These usually

include two NRTIs and one from another group. There is now no place for

treatment with one or two drugs only. Countries should develop their own

policies on which drugs to use in primary and secondary treatment regimes.

Where these exist they should be followed.

Factors to be considered in choosing drugs for the primary treatment regime

include:

•

Potency - that is the effectiveness or power of the drugs. For example,

NNRTIs are not effective against HIV2.

Side-effects

•

Interactions with other drugs - for example Zidovudine and Stavudine can not

be used together

•

Potential for future treatment options

•

Adherence - some drugs require precise timings and large numbers of tablets

to be taken.

Coexistent conditions

•

Risks in children and pregnant women - for example, Efavirenz can not be

taken in pregnancy or by children under the age of 3

Risk of resistance

•

Cost and other access issues

•

Suitability of each drug for use in areas of limited health infrastructure

•

Ease of transport - some drugs require storage in glass containers and/or

refrigeration

•

The existence of different groups and sub-types of HIV

•

The availability of formulations suitable for small children, such as liquids. It is

not recommended to break adult tablets for children.

•

In the case of children, whether or not mothers have received antiretrovirals

during pregnancy. Current evidence suggests that this does not need to be

taken into account when choosing drug regimes'

36

One primary treatment regime suggested by WHO is Zildovudine, Lamividine

and Abacavir. Secondary treatment regimes usually use two different NRTIs and

a drug from a different category. This would mean that if a PI is used in the

primary treatment regime, an NNRTI would be used in the secondary regime.

Secondary regimes are required for people whose disease does not respond to

the primary regime and those who experience side effects from the primary

regime.

Dosage of Antiretroviral Drugs in Children

It is important to calculate the dose of antiretroviral drugs accurately for children.

Many documents advise doing this on the basis of surface area. However, it is

not possible to measure a child’s surface area directly. This has to be calculated

from measurements of height and weight using formulae or charts. In some

cases, dosages can be calculated from a child’s weight. ‘Drug tables’ can assist

with these calculations and help to avoid errors.

Other Issues

A few general issues are considered here:

•

Children who have TB should usually complete their TB treatment before

starting treatment with antiretroviral drugs. This is because of the risk of

harmful interactions with the TB drug, Rifampicin.

•

Cotrimoxazole can be used to prevent children with HIV becoming ill with

pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). This is called PCP prophylaxis. It is

recommended in all children born to HIV positive mothers for 6-12 months.

•

Work is currently being undertaken to integrate issues relating to HIV into the

approach to childhood illness currently recommended by the World Health

Organisation. This is called the integrated management of childhood illnesses

(IMCI).

37

3.2.3 Practical Treatment Tips

This section looks at ways in which children with HIV (3.2) can be assisted to

take their antiretroviral drugs properly. Other sections cover issues regarding

access to treatment (3.2.1) and provide which antiretroviral drugs to use

(3.2.3).

Key points about treatment with antiretroviral drugs in children in practice are:

If antiretroviral drugs are to work properly they need to be taken regularly and

in certain ways. Taking drugs in the required way is called ‘adherence’ or

1

‘compliance’.

2. There are many reasons why people fail to adhere to the treatment

schedules.

3. There are a number of practical ways in which children can be helped to

adhere to treatment schedules.

4

In addition to their medicines, sick children and adults require a great deal of

care and comfort. Much of this is provided by family members in the home.

Why is Treatment Adherence so Important?

If antiretroviral drugs are to work properly they need to be taken regularly and in

certain ways. Taking drugs in the required way is called ‘adherence or

‘compliance’.

Problems with Taking Antiretroviral Medicines

There are many reasons why people fail to adhere to the treatment schedules.

These include:

. Some medicines, such as Stavudine, Didanosine and Ritonavir need to be

stored in a refrigerator.

. Some medicines need to be taken on an empty stomach. This means taking

them either one hour before food or two hours after. These include Indinavir

and Didanosine. In.addition, these two drugs need to be taken one hour apart

from each other. Some medicines need to be taken with food. These include

Nelfinavir, Saquianvir and Lopinavir.

• Some medicines interact with each other. One may stop the other from

working. They may also make side-effects more likely.

38

• Some medicines taste bad. Their taste can be improved by mixing with food,

such as milk. Examples include Nelfinavir and Ritonavir.

• Some capsules are very large and difficult to swallow.

• It is difficult to remember to take a medicine several times a day every day. It

may be difficult to fit this into schedules, such as going to school. Children

may not wish to take medicines in public.

• Some medicines cause side-effects which make the child feel ill. They may

not wish to take the medicine for this reason.

*

• It is difficult to calculate dosages based on surface area. It is easier to use

weight. Dosages need to be increased as the child grows.

Some projects have lists of questions that adults can answer to check that a child

is taking their medicines correctly.

Practical Ways of Improving Adherence

There are several practical ways of helping a child stick to their treatment

schedule. These include:

• Producing a schedule for taking all the medicines. This should fit in with the

family’s schedule, including mealtimes. ‘

• Finding ways of reminding children and their care givers when doses are due.

This may include sticking the schedule somewhere that it can be easily seen.

Alarm clocks and watches can be used to remind when doses are due.

• Having a way of recording when each dose has been given. This may include

a version of the schedule with boxes that can be ticked.

• Coloured bottles to show which medicine is which.

• Special dosing cups, measuring spoons or oral syringes to help ensure that

the right dose is given.

• Packing drugs into packages sufficient for one week. It is then possible to

check at the end of the week that all medicines have been taken.

• Being positive and encouraging in dealing with the child.

• Ensuring that an adult is involved with the child in taking the medicine. This is

particularly important for measuring the amount to be taken by small children.

39

Adults should also check that children have swallowed the medicine they

have been given.

. Finding ways of improving the taste of some medicines. This may include

mixing the medicine with something or taking something with a better taste

after the medicine. Chilling a medicine may make it taste better.

. Involving the child in taking their own medicines. This is particularly important

as the child gets older.

. Using medicines which can be given once per day rather than those that have

to be given more often.

• Using dosage tables which show how to calculate the dosage of medicines

from the weight of the child.

. Discussing any possible side-effects of the medicines with health staff.

. Informing health staff of any problems in taking the medicines. This includes

informing them of any missed doses.

Care and Comfort

In addition to their medicines, sick children and adults require a great deal of care

and comfort. Much of this is provided by family members in the home. Elements

J

of care and comfort include:

•

Listening, talking and touching

•

Dealing with past concerns

•

Planning for the future

•

Providing water and food

•

Washing

•

Changing the person’s position in bed. Rubbing Vaseline on the skin

•

Encouraging rest and exercise

•

Avoiding getting or spreading any infections

•

Treatment of common diseases, such as diarrhoea

•

Taking to a clinic

40

•

Buying medicines and assisting the person to take them

V

41

4 Education

This section looks at education issues which affect orphans and vulnerable

children. Other sections look in more detail at issues relating to early childhood

development (4.1) and school age children (4.2).

Key points about education and orphans and vulnerable children are.

1. Education is vital to the development of children in a number of ways.

2.

HIV/AIDS is having serious effects on the education sector. Many teachers

are sick or have died. The cost of education is also increasing because of the

need to train more teachers.