11346.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

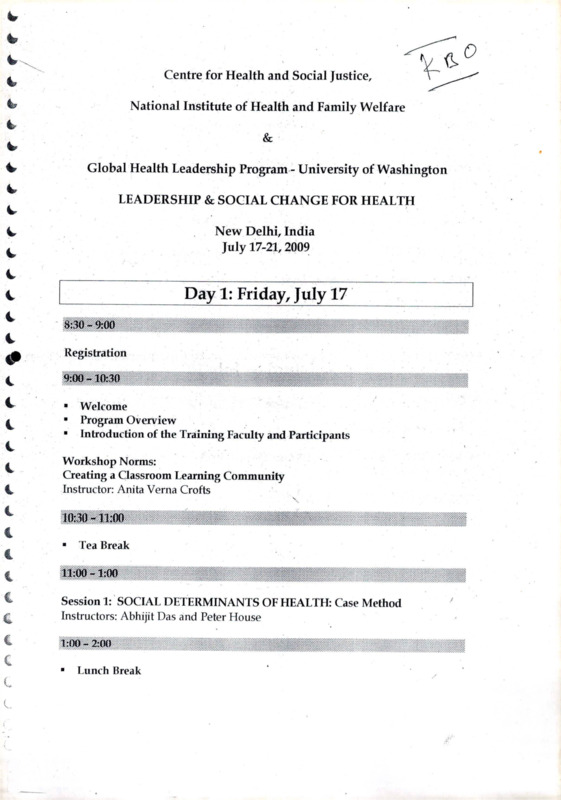

Centre for Health and Social Justice,

€

National Institute of Health and Family Welfare

&

Global Health Leadership Program - University of Washington

LEADERSHIP & SOCIAL CHANGE FOR HEALTH

New Delhi, India

July 17-21,2009

Day 1: Friday, July 17

8:30-9:00

Registration

9:00 -10:30

c

c

t.

€

■

■

■

Welcome

Program Overview

Introduction of the Training Faculty and Participants

Workshop Norms:

Creating a Classroom Learning Community

Instructor: Anita Verna Crofts

10:30-11'00

€

C

Tea Break

c

11:00 -1:00

<

Session 1: SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH: Case Method

Instructors: Abhijit Das and Peter House

c

€

C

c

C

1:00 - 2:00

Lunch Break

/

2:00 - 3:00

Session 2: SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH: Lecture

Instructors: Abhijit Das

3:00 - 3:30

■

Tea Break

3:30 - 4:45

Session 3: SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH: Small Group & Report

Instructors: Abhijit Das and Peter House

4:45 - 5:00

a

Daily Evaluation

Day 2: Saturday, July 18

9:00-10:30

"

Review and Preview

Session 4: MEANING AND VALUE OF COMMUNITY

Instructor: Jim Diers

10:30-11-00

a

Tea Break

11:00 -1:00

Session 5: COLLECTIVE LEADI

Across Cultures

Instructor: Anita Verna Crofts

^nity

1:00 - 2:00

o

Lunch Break

SOCHARA

Community Health

Library and Information Centre (CLIC)

Community Health Cell

85/2,1st Main, Maruthi Nagar,

Madiwala, Bengaluru - 560 068.

Tel: 080-25531518

email: clic@sochara.org / chc@sochara.org

www.sochara.org

*

i

2:00-3:00

Session 6 : COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION AND POWER

Instructor: Jim Diers

3:00-3:30

■

Tea Break

3:30-4:45

Session 7: COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION AND POWER, continued

Instructor: Jim Diers

I

1

■

(

Daily Evaluation

(

DAY THREE: SUNDAY, JULY 19

10:30

(

(

’

Review and Preview

(

(

(

(

Session 8: AUTHENTIC LEADERSHIP FOR MAKING CHANGE

Instructor: Anita Verna Crofts

10:30 - 11:00

■

Tea Break

(

11:00-1:00

(

(

Session 9: AUTHENTIC LEADERSHIP FOR MAKING CHANGE, Continued

Instructor: Anita Verna Crofts

(

(

(

c

c

1:00-2:00

Lunch Break

2:00-3:00

Session 10: ENGAGING THE COMMUNITY IN HEALTH DECISION

MAKING

Instructor: Peter House and Abhijit Das

3:00-3:30

Tea Break

3:30-4:45

3

Session 11: ENGAGING THE COMMUNITY IN HEALTH DECISION

MAKING, continued

Instructor: Peter House and Abhijit Das

•

Daily Evaluation

DAY FOUR: MONDAY, JULY 20

9:00-10:30

■

n

o

Review and Preview

Session 12: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEEN THE GOVERNMENT THE

COMMUNI1% AND NONPROFITS

Instructors: Abhijit Das, Jim Diers, Anita Verna Crofts, and Peter House

•■■w0

■

■■ a

Tea Break

11:00-

■

Report Back

Session 13: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEEN THE GOVERNMENT THE

COMMUNITY, AND NONPROFITS

Instructors: Abhijit Das, Jim Diers, Anita Verna Crofts, and Peter House

12:00-1:00

Session 14: INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

Instructor: Neera Dhar

J

1:00-2:00

Lunch Break

C

c

2:00 -3:00

L

L

L

Session 15: INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION, continued

Instructor: Neera Dhar

3:00-3:30

Tea Break

L

3:30-4:45

t

(

Session 16: NEGOTIATING POLICITCS AND HEALTH

Instructor: Deoki Nandan

4:45 - 5:00

€

■

Daily Evaluation

DAYFIVE: TUESDAY, JULY21

9:00 -10:30

(

Review and Preview

Session 17: INDIVIDUAL ROLE OF A CHANGE AGENT

Instructor: Jim Diers

<

10:30 -11:00

<

<

Tea Break

11:00-1:00

<

c

Session 18; World Cafe Wrap Up

Writing of letters to be sent four months into the future

«

<■

c

€

C

it I

1:00-2:00

■

Lunch Break

2:30 - 3:00

"

Daily and Final Evaluation

3:00-3:30

■

0

n

Certificates & Tea Break

' 1 )

o

o

o

Q

o

o

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM:

To Improve Effectivity, Accountability,

& Communitisation of Health System

Participant Reading List

Day 1 - Friday, July 17, 2009

B

■

8

The Argumentative Indian - A. Sen

Globalization and Health - R. Labonte, T. Schrecker

Pathologies of Power - P. Farmer

Day 2 - Saturday, July 18,2009

■ Politicizing Health Care - J. McKnight

■ Six degrees of Lois Weisberg - M. Gladwell

■ Six degrees of Lois Weisberg Glossary

■ The Relational Meeting - E. T. Chambers

■ Why Organize? Problems and Promise in the Inner City - B. Obama

■ Developing a strategy - K. Bobo, J. Kendall, S. Max

■ God created the world, and we created Conjunto Palmeira - R. A.

Newmann, A. Mathie, J. Linzey

■ Building communities from inside out - J.P. Kretzmann, J.L. McKnight

Day 3 - Sunday, July 19, 2009

■

■

■

■

■

■

Behaviour Styles Information Sheet

Behaviour Styles Rating Form

"What's your story?" A life-stories approach to authentic leadership

development - B. Shamir, G. Eilam

Definitions and Significance of Leadership

Nominal Group Technique: A User's Guide - R. Dunham

Open Space Technology: A User's Guide - H. Owen

Day 4 - Monday, July 20, 2009

■

■

■

Moving Towards Partnership

Healthy Cities: A Model for Community Improvement - D. Clark

Neighbor Power: Building Community the Seattle Way - J. Diers

Leadership Development Programme

To Improve Effectivity, Accountability and Communitisation of Health System

17-21 July, NIHFW, New Delhi

Resource Team

i

(

(

(

(

(

(

(

(

(

(

C

(

(

Anita Verna Crofts believes that strong communication skills help build strong leaders.

Anita works with professionals to identify communication competencies and strategies

that allow for successful visioning, planning, and results.

As Director of Communication and Outreach for the Population Leadership Program and

the Global Health Leadership Program at the University of Washington, Anita designs

and delivers curriculums on professional communication strategies, storytelling as a

leadership and evidence tool, digital media adoption in resource-poor environments,

and cross-cultural communication techniques for an international development setting.

She also oversees both the documentation and promotion of continuing partnerships

with 78 international PLP Fellows in more than 20 countries worldwide. Her most recent

co-authored article appeared in the book Global Leadership: Portraits of the Past, vision

for the Future, and is entitled, "Vision for Change: Partnering with Public Health Leaders

Globally."

She has taught as a lecturer at the UW's Daniel J. Evans School of Public Affairs and most

recently at the Department of Global Health. Prior to her affiliation with the Population

Leadership Program, she served as Executive Director of the Foundation for

International Understanding Through Students (FIUTS) on the University of Washington

campus. Along with her work at the University of Washington, Anita is an award-winning

journalist and writes and photographs articles on the intersection of culture, food, and

identity.

Anita holds a Bachelor of Arts from Haverford College in Anthropology and East Asian

Studies, and a Master of Public Administration from the University of Washington with

an area focus on leadership and nonprofit management.

Abhijit Das is a doctor with training in obstetrics, paediatrics and public health and has

over twenty years experience in grassroots work, training, research and policy advocacy.

He is founder member of the alliance on men and gender equality MASVAW, and the

reproductive health and rights network Health watch Forum. He has been working on

population and reproductive health issues in India as a consultant to United Nations

Population Fund for a number of years. Currently he is Director of the Center for Health

and Social Justice (CHSJ), a health policy resource organization which is hosting the

national secretariat for ICPD +15 in India : A Civil Society Review. He is among the

leading public health educators and advocates on issues related to coercive population

policies. Abhijit has been a Fellow of the Population Leadership Program of the

University of Washington and is also a Clinical Assistant Professor at the UW

Department of Global Health.

■■H■■

lOSIoll

Jim Diers has a passion for getting people more involved in their community and in the

decisions that affect their lives. Since moving to Seattle in 1976, he put that passion to

work for an Alinsky-style community organization, a community development

corporation, a community foundation, and for Group Health Cooperative. He was

appointed the first director of Seattle's Department of Neighborhoods in 1988 where he

served under three mayors over the next 14 years. Currently, Jim works for the

University of Washington where he teaches courses in community organizing and

development and directs the Seattle-UW Community Partnership Program. Jim also

serves on the faculty of the Asset-Based Community Development Institute and works

with other cities to develop programs of community empowerment.

Jim received a BA and an honorary doctorate from Grinnell College. His work in the

Department of Neighborhoods was recognized with an Innovations Award from the

Kennedy School of Government, a Full Inclusion Award from the American Association

on Developmental Disabilities, and the Public Employee of the Year Award from the

Municipal League of King County. Jim's book, Neighbor Power: Building Community the

Seattle Way, is available through the University of Washington Press.

w

•

V

Peter House cares about communities and public sector organizations and he works

*

with them on planning, governance, and decision-making. Peter is a Clinical Associate

Professor at the University of Washington where he teaches community development

V.

for health courses in the School of Public Health and a course in rural health in the

School of Medicine. Mr. House serves as associate director of the WWAMI Area Health

*

v...

Education Center where he works to support the University of Washington School of

Medicine's regional mission to improve the distribution of health professionals. He is a

former member of the board of directors of the Washington Rural Health Association, a

group that recognized Peter with its "Outstanding Contribution to Rural Health Award"

in 1999. Peter has applied his professional expertise to active engagements with

Seattle's public schools and with political organizing in the state of Washington.

Peter graduated from the University of Michigan with a master's degree in health

I

administration in 1974. He received a bachelor's degree in mathematics from Lawrence

University (Appleton, Wisconsin) in 1968. Peter has wide experience in strategic

planning, program evaluation, meeting facilitation, community assessments, and

community development. Peter has worked with over 50 rural communities to

strengthen and expand their health systems, and he has made numerous presentations

to professional meetings in the US and abroad.

L

t

t

lational Institute of Healtl

nons Causa-Odessa State i

>elhi

MVIS, FIAPSM, FIPHA,

V.

t

Ik-

Prof. Deoki Nandan, Doctor Honoris Causa-Odessa State Medical University, MD, FAMS,

FIAPSM, FIPHA, FISCD, is Director of National Institute of Health & Family Welfare, New

Delhi. He has worked as Principal/Dean & Chief of Hospital, S N Medical College, Agra.

He has been actively working in the field of public Health for more than 30 years and

during this period he has been an adviser and have provided consultancy to many

international Organizations e.g. WHO-SEARO, UNICEF, CARE-lndia, EPOS, Population

Council, MOST-lndia and USAID. He is also member of many state level committees and

National Technical Expert Committees specifically for AIDS, IMNCI and Child Health.

He has also been identified as National Trainer for ICDS, CSSM, RCH, RTI/STD, HIV/AIDS

and IMNCI. He has successfully undertaken more than 45 community based

studies/research/projects on issues related to EPI, RCH, RTI/STD, and HIV/AIDS, in

collaboration with national and international agencies, and has numerous research

papers published in national and international scientific journals. Besides Public Health

Dr Deoki Nandan has also presented excellent performance academics and has teaching

experience of undergraduate and postgraduate medical students. He is Technical

member of PSC selection boards of Govt, of MP, UP and Uttarakhand; Academic Council

member for Agra, Aligarh and Gwalior Universities; Member Governing Council of State

Medical Faculty, UP and examiner for MBBS/MD examinations for more than 30

universities. He had also been nominated by Govt, of UP for Human Rights and has also

been invited as an expert in international meets/workshops.

Dr. Neera Dhar has been involved in designing, coordinating training courses & acting as

a resource person in various training programmes conducted at NIHFW She has also

been engaged in research activities of the Institute in the area of Health SFamily

Welfare. Involved in the teaching and field activities of M.D.(CHA/DHA) Programme

She also acts as a Faculty Guide for M.D (CHA/ DHA) Seminars and Dissertation at the

nstitute. Dr. Neera has been a Guest speaker to various organizations and sister

Institutions for sessions on "Stress Management", "Organizational Behaviour" and

Interpersonal Communication" and Training Technology" As part of larger

organizational responsibilities she also been working as the "Managing Editor" of the

Institutes' quarterly Newsletter since March 2008.

She has in her credit a book on Stress Management titled: "STRESS: LEARN TO MANAGE

IT. SOME COPING TECHNIQUES TO MAKE LIFE EASIER TO LIVE"

She selected as a "Rotary Scholar"from India by the "Rotary International" to work

towards projecting Indian Culture in USA(1989). She was also granted Fellowship by the

Rotary International" to pursue Post Doctoral Studies in USA(1989).

Participant Reading List

DAY 1 - Friday, July 17, 2009

■

The Argumentative Indian - A. Sen

■

Globalization and Health - R. Labonte, T. Schrecker

■

Pathologies of Power - P. Farmer

I

AMARTYA SEN

‘The winner of the 1998 Nobel prize in economics is a star in|India...

he deserves the recognition...shows that the argumentative gene is

not just a part of India’s make-up that can easily be wished) away’

Economist

lKn introduction as good as any to matters Indological’

Chandrahas Choudhury, Scotland on Sunday

I

The Argumentative Indian

J

I

■ I

i

Writings on Indian History,

Culture and Identity

-j

1

about the author

Amartya Sen is Lamont University Professor at Harvard. He ivon the

Nobel Prize in Economics in 1998 and was Master of Trinity follege,

Cambridge, 1998-2004. His most recent books are Development as

Freedom and Rationality and Freedom. His books have been translated

into more than thirty languages.

•J

?

I

I

I

I

I

I PENGUIN BOOKS

i

4

T

il

CLASS IN INDIA

IO

Diverse Disparities

Class in India*

In his speech on the ‘tryst with destiny’ delivered on 14 August 1947,

with which the last essay began, Jawaharlal Nehru talked not just

about freedom from British rule, but also about his grand vision of

independent India.f Nehru was particularly determined to remove the

barriers of class stratification and their far-reaching effects oh inequal

ity and deprivation in economic, political and social spheres. It was

was aa

thrilling image that could rival Alfred Tennyson’s eloquence:

‘For I

dipt into the future, far as human

1

# could

_______

eye

see,, / ______

Saw the (Vision of

the world, and all the wonder that would be.’ It was good for free

India to be told, at the defining moment of its birth, about ihe possi

bility of‘all the wonder that would be’.1

Nehru s vision was not fulfilled during his own lifetime.! There is

nothing surprising in that, since the vision was ambitious. iWhat is,

however, more distressing is the slowness of our progress in the direc

tion to which Jawaharlal Nehru so firmly pointed. But that is not all.

There is disturbing evidence that the battle against class divisions has

very substantially weakened in India. In fact, there are clear indif

.

....

.

.

31 at d,^ere”t levels Economic, social and political policy,

the debilitating role of class inequality now receives remarkably litth

attention. Furthermore, support for consolidation of class barriei

!tS

comes not only from old vested interests, but also from new sources

of privilege, and this makes the task much harder.

This essay is based on my Nehru Lecture, given in New Delhi on rj Nov. iooi.

• i 4W]har,a ^Chru’s spcech’ def,v®"d at the Constituent Assembly, Ne^ Delhi, is

included in/.i^^rZa/ Nehru: An Anthology, ed. Sarvepalli Gopal (Oxford and DelhiOxford University Press, 1983 J.

This is a difficult Subject to deal with, for two distinct reasons. First,

class is not the ohly

source of inequality,

and interest

in class

„

.

..

______________} as a

source of

< disparity has to be placed within a bigger picture that

includes other div sive influences: gender caste, region, community

and so on. For example, inequality between women and men is also a

major contributor to inequity. This source of inequality used to be

fairly comprehensively neglected in India even a few decades ago, and

in this neglect the single-minded concern with class did play a role.

Indeed, about threi decades ago, in the early 1970s, when I first tried

to work on gendefl inequality in India, I was struck by the fact that

even those who welfe extremely sympathetic to the plight of the under

dogs of society wefe reluctant to take a serious interest in the evil of

gender discrimination. This was to a great extent because of the firmly

established tradition of concentrating almost entirely on class divi

sions as a source of inequality. That single-mindedness is no longer

dominant, and thejfe is increasing recognition of the importance of

causes of disparity other than class divisions, including inequality

between women and men. Even though gender and other contributors

to inequality still require, I would argue, more systematic attention,

nevertheless there has been a considerable enrichment of the versa

tility and reach of public discussion in India.

There is, howeVer, an interesting issue that goes beyond the

‘whether’ questionj to rhe ‘how’ question. Should these different

sources of inequality be seen as primarily ‘additive’ to each other

(there is class and then there is also gender, and furthermore, caste,

and so on’), or shoiUld they instead be treated together, making more

explicit room for their extensive interdependences? These different

sources of vulnerabljlity are each significant, but no less importantly,

we must see that they can strengthen the impact of each other because

of their complemenl

complementarity.

Class, in particuldi;

particulii; has a very special role in the establishment and

reach of social inequality, and it can make the influence of other sources

of disparity (such as gender inequality) much sharper. The intellectual

gain in broadening oUr comprehension of other types of inequity has to

THE ARGUMENTATIVE INDIAN

ij

CLASS IN INDIA

■

be followed with a more integrated understanding of the functioning of

class in alliance with other causes of injustice. Oi; to put it differently,

class is not only important on its own, it can also magnify the impact of

other contributors to inequality, enlarging the penalties imposed by

them. The integration of class in a consolidated understariding of injus

tice is. of paramount importance given the need to address, simultane

ously, different sources of inequality, related to class, gender,

community, caste and so on, and given the overwhelming role of class

in the working of each of the other contributors to inequality.

A second source of complexity lies in the fact that some of the new

social barriers reinforcing rather than weakening rhe [hold of class

divisions come - as it were - from the ‘friendly’ side or the dividing

line; they can, in fact, be rooted in institutional devices that are

intended to be among the remedial features against clas^ division. For

example, public programmes of intervention can protect vulnerable

interests and thus serve as a good instrument in the battle against

class-based inequality. However, they can also have regressive con

sequences if the battle lines are wrongly drawn, or if the remedies are

wrongly devised.

In fact, what the armed forces call ‘friendly fire’ - whereby an army

is hit by its own firing rather than by enemy shelling - is a concept that

may have relevance not just in the military spheres but In social fields

as well. The actual impact of supportive public institutions and public

policies has to be constantly scrutinized. The operative impact of

institutions and programmes that have been instituted as anti

inequality devices requires probing investigation in an open-minded rather than in a fixed, formulaic - way.

I shall take up these two issues in turn: first, the need for an integ

rated understanding of the contribution of class in the combined

impact of diverse sources of inequality; and second, the possibility of

‘friendly fire’, which requires us to rethink the old battle lines against

inequality. In particular, the relevance of new barriers strongly

suggests the need to re-examine the ways and means bf confronting

class inequality.

In this essay, I shall try to identify two specific issues to examine in

trying to understand the far-reaching relevance of class in India: first,

rhe ‘integration issue’ (to see the influence of class as not merely

additive,

. .

' but

- - 7alsc

—n as transformational), and second, the ‘institutional

issue’, in particular the role of institutional features - new and old in reinforcing and even strengthening class barriers.

CZflSji, Gendet) Caste and Community

The significant presence of non-class sources of inequality is an impor

1

J

4r

I-

I

tant recognition that can be combined with the acknowledgement that

there is hardly any aspect of our lives that stays quite untouched by

our place in the dass stratification. Class does not act alone in creat

ing and reinforcing inequality, and yet no other source of inequality is

fully independent of class.1

k

Consider gender. South Asian countries have a terrible record in

gender inequality which is manifest in the unusual morbidity and

mortality rates of women, compared with what is seen in regions that

do not neglect women’s health care and

nutrition so badly. At the

----- ----------same time, women from the upper classes are often more prominent

A

.

1

«•

• .

“ South Asia

than elsewhere.

Indeed,

India,

Pakistan,

Bangladesh

and

—m

.uvuu, Mium,

raxisian,

Bangladesh and

Sri Lanka have al had, or currently have, 1women Prime Ministers something that th^

t^e United States (along with Trance, Italy, Gr

Germany

and Japan) has nejyer

never had and does not seem poised to have in th

the near

future (if I am any judge).

Belonging to k privileged

„ classs can help women to overcome

barriers that obstruct women from

_______

___ classes. Gender is cerless thriving

tainly• an additiodkl

contributor

to

societal

inequality, but it d<

i------------ uxzwAviax ixxwjumiLy, uui 11 does not

act independently

‘

of class. Indeed, a congruence of class deprivation

and gender discrimination can blight the lives of poorer women very

severely indeed. It is the interactive presence of these two features of

deprivation - being low class and being female - that can massively

impoverish women from the less privileged classes.

Similarly, turnling to caste, even though being lower caste is

undoubtedly a separate cause of disparity, its impact is all the greater

when the lower-calste families also happen to be very poor. The blight

ing of the lives of Dalits or people from other disadvantaged castes, or

of members of the Scheduled Tribes, is particularly severe when the

caste or tribal adversities are further magnified by abject penury. Even

t

tv

—

; ’•

0

THE ARGUMENTATIVE INDIAN

the Violence associated with caste-related conflicts tends tjo involve a

great deal more than just caste.

For example, the Ranveer Sena in Bihar may be a privat

army that

draws its sustenance ffrom the upper (in this case, BhJmihar and

Rajput) castes, and the victims of brutality may typically bje low-caste

Dalits, yer the predicament of the potential victims cam

inot be adequately grasped if we do not take note of the poverty and landlessnes;

i L _ .j i. _

of Dalits, or place the conflicts in a broad social and economic background. This recognition does not suggest that caste is unimportant

(quite the contrary), but it does make it necessary to place casterelated violence in a broader context in which class, inter alia,

belongs. The basic issue is complementarity and interrelation rather

than the independent functioning of different disparities that work in

seclusion (like ships passing at night). Given the wide reach and

generic relevance of class, related to poverty and wealth,!ownership

and indigence, work and employment, and so on, it is not surprising

that it tends to rear iits ugly

' head

‘

in a great many conflicts that have

other identifications

and

correlates.

ms and correlates.

I

In fact, there is ialso considerable evidence

_

that affirmative action in- z

favour of lower castes has tended to do much

— ------ 1 more for the econo

mically less strained members of those c_____ 1____ _

afC

castes than for thojse who are

weighed down by the combined burden of e^eme^pove^andVwness of caste. For example, ‘reserved’ posts often go to relaiively afflu

ent members of disadvantaged castes. No policy of affirmative action

aimed at caste disadvantage can be adequately effective without taking

account of the class background of members of the lower icastes. The

impact of caste, like that of gender, is substantially swayed [by class.

Or consider the deprivation that is generated by tommunal

vio ence. Members of a minority community can indeed hlave reason

or fear even when they come from a prosperous class. Yet the raw

danger to which targeted communities are exposed is Immensely

magnified when the persons involved not only belong to those com

munities, but also come from poorer and less privileged families. This

is brought out by the class distribution of victims of Hindu-Muslim

riots around the time of independence and rhe partition of) India. The

easiest to kill among rhe members of a targeted community are those

o that group who have to go out unprotected to work, who live in

j

slums, and who It

CLASS IN INDIA

jpad, in one way or another, a thoroughly vulnerable

life. Not surprisL,

thgly, they provide the overwhelming proportion of

the victims in communal riots.

" ‘ "

My own first Exposure to murder ar

.

?

<

his last words tofme were that he knew he was tiking a heavy risk in

hone^Ta3 arg<l'y|H;ndu region of the dty. but he had to do it in the

hope of earning a little money from some work (he was on his way

thelTd

dT

ed)' Kad" labourer;

Mia diedlooking

aS 3 V1Ctimizcd

Mus1for^a

but he also died

4 mi unemployed

desperately

bit of work and r

This was in i, '44- The riots today are not any different in this

respect. In the Hikdu-Muslim riots in the

nnnr^. .

7*““““

I94°S’ Hil,du

billed

the i“verZd

U”S’ n

MUSlim thuSS assass“ated the

impoverished

perished Hirijdu

Hiridu victims. Even though th

the community identity of

extermtnate^ preys was qquite different (Hindu and Mushm

the exterminated

respectively), theft

uieir class

Class identitiridentities were often extremely similar. The

ckss dimension if sectarian violence tends to receive inXu«e

attention, even. inrr*

—"------- accounts, because of unifocal reporting

newspaper

that concentrated

on the divide

communal identity of the ‘victimZ

. I

\ 5 77~’communal identity of the victims

rather than on ttnejir

ki:----1*-J •

••

7

vicums

identity.

n**- unified

'?**“**•“ class lucnm

This remark would apply also to the

Muslim^

fhU°Wing Indira Gandhi’S assassination- ^e anti-

Aaf accompanied the terrible days that foil.

, , and so on. Class is an ever-present

feature of commu lai and sectarian violence.

What we need, therefore, is some kind of a dual recognition of the

role and reach of : ass that takes into account its non-uniqueness as

well as its transfo ^national function. Wt

;—t—. ”Tc have to recognize, simultaneously, that

<i.)

diere are many sources of disparity other than class: we must avoid the

presumption thkt class

encompasses all sources of disadvantage and

handicap; and

|

I

1

:i

THE ARGUMENTATIVE INDIAN

(z) nevertheless, class disparities are not only important on dleir own. But

they also tend to intensify the disadvantages related to the other forms of

disparity.

Class is neither the only concern, nor an adequate proxy for other

forms of inequality, and yet we do need class analysis to see the work

ing and reach of other forms of inequality and differentiation.

Inequality, Concurrence and the Underdogs

Aside from the variety of factors that contribute to inequality, there is

also the important issue of the form that inequality may ta ke. Here, it

may be thought, class speaks in many voices, with much discordance.

There is truth in this recognition, but once again this may loot weaken

the overwhelming relevance of pre-eminent class divisions in under

standing the plight of the underdogs of society. We have tb see simul

taneously the distinctions as well as the interconnections.

There are imany different forms of deprivation: economic poverty,

illiteracy, political disempowerment,

ofand

health

care

,

t absence

- -------so on.

These distinct dimensions of inequality are not entirely congruent in

their incidence. Indeed, they can yield very different socia rankings.3

The tendency to see deprivation simply in terms of income poverty is

often strong and can be quite misleading. And yet there arte also pow

erfully uniting features in the manifestation of severe deprivation. This

is partly because different types of handicap reinforce eac^i other, but

also because they often tend to go together at the extreme tends, divid

ing the general ‘haves’ from the comprehensive ‘have-nots’. The

absence of a conceptual congruence between different types of depri

vation does not preclude their empirical proximity along a big dividing

line, which is a central feature of classical class analysis.

Some Indians are rich; most are not. Some are very well educated;

others are illiterate. Some lead easy lives of luxury; others toil hard for

little reward. Some are politically powerful; others cannot influence

anything. Some have great opportunities for advancement in life;

others lack them altogether. Some are treated with respect by the

police; others are treated like dirt. These are different kinds of

CLASS IN INDIA

inequality, andleach of them requl...

ancntlon

us is the central issue in the centrality of cl;

P0°r m inCOme and wealth> suffer from illiteracy, work hard for little remuneration,

,

> are uninfluential in politics,

lack social and economic

’ opportunities, and are treated with brutal

callousness by tje police. The dividing line of ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots'

is not just a rhetorical cliche, but also an important part of dragnostic

analysis, pomtinfe us towards a pre-eminent division that can deeply

inform our social,

sodial, economic and political understanding. This

PWatlOn adds t0 the ’’''“arching relevance of class

as a source of inltquality and disparity.

tt*—**-/

uiapcuicy.

When I come to

to discuss the issue of what I called ‘friendly fire', the

role of such manifest

ifest concurrence in the lives of the extreme underdogs'

underdogs

of soaety will beiome

particularly

relevant.

Many

of

the

distributional

come particularly relevant. Many of the distributional

institutions that Jxist in India and elsewhere are designed to defend the

interests of groups with some deprivation (or some vulnerability) but

who are not by foy means the absolute underdogs of society. There is

an understandable rationale for seeing them as ‘friendly1 institutions in

the battle against class divisions. Yet if they also have the effect of

worsening the deal that the real underdogs get, at the bottom layers of

society, the overall impact may be to strengthen class divisions rather

Th'S ‘S the SenSE ‘n Which their effects can be

non^S firC ’ t1 T afraid there 15 3

deal °f this Pbenomenon in Indian public policy as it stands.

It is extremely mportant to study the issue of ‘friendly fire', though

not because it isjjthe largest contributor to class divisions in India’

traditional factors, such as massive inequality of wealth and

assets,

immense gaps in location and other social opportunities and

so on,

remain central to our understanding of the brute force of clas'

:s

sions.

^upptementea by divinew

sions. Yet

Yet these

these traditional

trud;„„... ' features

’

are now supplemented by

barriers, some oj which were created precisely to overcome the

influence of class,, but-■ end up having the opposite effect.

I can illustrate the

I point with a great many examples. LI shall, however, concentrate iln this essay on exactly two paradigmatic illustranons, dealing respectively with food policy and elementary schooling,

both of which have a major bearing on the lives of the most deprived

among the Indian beoole. that is. the hunerv and rhe illiterate

i.

THE ARGUMENTATIVE INDIAN

CLASS IN INDIA

gets, When it ge^ any at all, is so badly divided.’

Food Policy and Hunger

I

India’s record in countering hunger and famine is s

strangely mixed.

The rapid elimination of famine since independence is

-3 an acme

---------levement

of great importance (the last real famine occurred in 1943

>ur years

before-independence), and this is especially so in contrast tJ the fail

t01 prevent

ure of many other countries - most notably China - to

to prevent

famine. Whenever a famine has threatened, the safeguards of

lr a. dem

j.

ocratic process have come into operation, with rapidly arranged

pro

•aiiged protective policies, including temporary public employment,

w’hich give

.1 I

•

y*

the threatened destitutes the money to buy food. The mech'anism

of

famine prevention in IIndia has been discussed in my joint bOok with

Jean Dreze, Hunger and Public Action/

—-4 It is a record, we (argue, of

considerable achievement.

And yet India’s overall record in <'

_ ________

eliminating

hunger___

and undernutrition is quite terrible. Not only is there pe«isten7rec

■rence of

severe hunger m particular regions, but there is also a dreadful pr<

revalence of endemic hunger across much of India. Indeed, Irjidia does

worse in this respect than even sub-Saharan Africa.5 Calcu ations of

general undernourishment - what is sometimes called ‘protJin-enlrgy

malnutrition’ - show that it is nearly twice as high in India ks in subSaharan Africa on the average. It is astonishing that despite,'the inter

mittent occurrence of famine there, Africa still manages tq‘ ensure a

higher level of regular nourishment than does India. Judged in terms

of the usual standards of retardation in weight for age, the proportion

o undernourished children in Africa is 20 to 40 per cent, wAereas the

percentage of undernourished Indian children is a gigantic 40 to 60

per cent. About half of all Indian children are, it appears, Ironically

undernourished, and more than half of all adult women stiffer from

anaemia. In maternal undernourishment as well as the incidence of

underweight babies, and also in the frequency of cardiovascular

disease in later life (to which adults are particularly proni if nutri

tionally deprived in the womb), India’s record is among the very worst

in the world.7

I

A striking feature of the persistence of this dreadful situation is not

i".»repe;,ion ZXfsSS”

■ng to hear persistent u

managed the cha lenge

Iphop of hunger

k

is based on a

is a simple achieyti

ment 1

worse than nearh

con tex

tinued to amass e

.

De

* that

has

inc stock was

ItT r t r 7 tOnneS ’ C1°Se to the

‘buffer

stock’ norms.

ly surpassing

62. million tonn<

Lecture in :

J'“ D,i“1 ^aph,t ‘■““’d”-1< >« *"

sacks of grain

—»n k,te„J X ”

.

»»»«

grain for every fXy below the poye^

°“ tonne of food

presumption of mere insensiti v!w-it lolk

eXplauI ir by the

ity. What could

the perceived t

m°re and more ^ke insanexplain the simulLeourXnceTh 6

COU,d

and the largest uniised food stork ■ k ' W°rSt undernourishnlent

constantly augmented at extremelytavyTos^^

ofstoc^SZtteV5 nOt>hard tO find- The —'-on

support prices for Ud grain -Z"wheat

minimum

d nce ln Papula* But a

regime of high pri tes in ™

m general (despite a gap between procurement

prices and consumers’ retail

?_nCeSf kotk exPands procurement

and depresses demand. The bonanza

“1 for food producers and sellers

is matched by the privation of food c

consumers. Since the biological

|l

’We discuss the role Ipfinadequa.

'ey of public discussion in the formulation and perSen’

o'r/o <tn’ M‘a:

l.wU r,,,h|ir aftenrion it

I

THE ARGUMENTATIVE INDIAN

I

need for food is not the same thing as the economic entitlement to

food (what people can afford to buy given their economic

circumstances and the prices), the large stocks procured are hard to

get rid of, despite rampant undernourishment across the Icountry. The

very price system that generated a massive supply kept the hands and the mouths - of the poorer consumers away from food.

But does not the government automatically remedy this problem

through subsidizing food prices compared with the procurement

prices - surely that should keep food prices low to consumers? Not

quite. The issues involved are discussed more fully in my joint book

with Jean Drfeze, India: Development and Participation^ (2002), but

one big part of the story is simply the fact that much of the subsidy

does in fact go to pay for the cost of maintaining a massively large

stock of food grain, with a mammoth and unwieldy foot} administra

tion (including the Food Corporation of India). Also, since the cutting

edge of the price subsidy is to subsidize farmers to produce more and

earn more, rather than to sell existing stocks to consumfers at lower

prices (that happens too, but only to a limited extent and to restricted

groups), the overall effect of the subsidy is more spectacular in trans

ferring money to medium and large farmers with food to sell, than in

giving food to the undernourished consumers.

If there were ever a case for radical class analysis, in which ‘the left’

could take ‘the right’ to the cleaners, one would have thought that this

would be it. To some extent, we do see such criticism, bujt not nearly

enough. The dog that does not bark is the expectable howl of criticism

from the perspective of class analysis.

Why? This is where the diagnosis of ‘friendly fire’ becomes rele

vant. When1 the policy of food procurement was introduced and the

case for purchasing food from farmers at high prices was lestablished,

various benefits were foreseen, and they were not altogether pointless,

nor without some claim to equity. First, building up stocks up to a

certain point is useful for food security - necessary even for the pre

vention of famines. That would make it a good thing to have a large

stock up to some limit - in today’s conditions, perhaps even a stock of

20 million tonnes or so. The idea that since it is good to build up

stocks as needed, it must be even better to build up even more stocks,

is not only mistaken, but also leads to shooting oneself in the foot.

I

I1

i

■

£

,F

■L

• |

CLASS IN INDIA

I must also examine a second line of reasoning in defence of high

il • also comes in as a good idea and then turns

food prices, which

counterproductive. Those who suffer from low food prices include

some who are not•t affluent - the small farmer or peasant who sells a

part of his crop|J The interests of this group are mixed up with those

of big farmers, ^nd this produces a lethal confusion of food politics.

While the power ful lobby of privileged farmers presses for higher pro

curement prices| and pushes for public funds to be spent to keep them

high, the interests of poorer farmers, who also benefit from the high

prices, is championed by political groups that represent these non

affluent beneficiaries. Stories of hardship among these people play a

powerful part not only in the rhetoric in defence of high food prices,

but also in the genuine conviction of many equity-oriented activists

that this would help some very badly off people. And so it would, but

of course it woujd help the rich farmers much more, and cater to their

pressure groups while the interests of the much larger number of

people who buy! food rather than sell it would be badly sacrificed.

There is a nedi for more explicit analysis of the effects of these poli

cies on the diffei ent classes, and in particular on the extreme under

dogs of society | who, along with their other deprivations (already

discussed), are also remarkably underfed and undernourished. For

casual labourers, slum dwellers, poor urban employees, migrant

workers, rural artisans, rural non-farm workers, even farm workers

who are paid cash wages, high food prices bite into what they can eat.

The overall effect of high food prices is to hit many of the worst-off

members of society extremely hard. And while they do help some of

the farm-based pjoor, the net effect is quite regressive on distribution.

There is, of course, relentless political pressure in the direction of high

food prices com|jng from farmers’ lobbies, and the slightly muddied

picture of benefiting some farm-based poor makes the policy issues

sufficiently befuddled to allow the confusion that high food prices are

a pro-poor stance, when in overall effect they are very far from that.

It is said that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. So unfortunately

is a little bit of equity when its championing coincides with massive

injustice to vast numbers of people. It is, again, a case of ‘friendly fire*,

even though the involvement of the rich farmers’ pressure groups

thickens the plotjj

■‘is-

.

the

•I

ARGUMENTATIVE INDIAN

»•

W---'

Elementary Education

■■

ta<

• The paucity of financial

w

-‘w are (not enough

------- .1 very

well. A major diffi-

several other problems

culty hes in the weak institutional

, ---- 1 are (

inequity of schooling —

®V

system of primary education?

I have had th<

sample of the problems

lect by the Pratichi

999 with the) help of the

,Ih0

!».r

V"up ” t * -T-a num-<

■i

I

West Bengal initially 1 , ,dThc overall picture

saKumune

_/tlh^khan

that

p"“"

T„ch„

1

„„„ „„. "fl"d

A

M

‘ :o“

• b■

lays we visited them

very much greate ’ in schools

------- Jaste o r Scheduled

nbe families; indeed, 75 per cent of those schooJs

our 1 st had seri-

•*- *» i-

■

■

proponion al cbe children rely ™ 'T V3nM8e‘I

A very Inge

what they get from the schnnk

a ^nVate tultIon as a supplement to

L

vented from doing so becausey pre

satisfied with the teaching rhe rh N

rat^er

becaijse of being

j

pupil.» a.„,'

" 8J ‘

«■"

Amrita SengupSworki^^

findings from the first part of the studv- Th. n

West Bengal (New Delhi:

‘‘‘ “ *

1.M o< a!

*- *

RRn3’ AbdurlRafi^e and

pres<ius 1116 main

OfrMK Edu^

!i

- CLASS IN INDIA

Effective elementary education has in practice ceased to be free in

substantial parts of the country, which of course is a violation of a basic

nght. AU this seeds to be reinforced by a sharp cfass division between

teachers and the poorer families. Yet the teachers’ unions - related to

the respective parties - sometimes vie with each other in championing

the immunity of dachers from discipline. The parents from disadvan

taged families have little voice in the running of schools, and the offi

cial inspectors seqm too scared to discipline the delinquent teachers,

especially when thfe parents come from the bottom layer of society. The

teachers’ unions hive, of course, had quite a positive role in the past in

defending the inteiests of teachers, when they used to be paid very little

and

"" were thoroii]

‘■hTrz jghly exploited. The teachers’ unions then served as an

important part ofi the institutional support in favour of more justice.

Now, however, thdse institutions of justice seem to work largely against

justice through thkir inaction - or worse - when faced with teacher

absenteeism and dther irresponsibilities.

The problem isj in some ways, compounded by the fact that school

teachers are now Comparatively well paid - no longer the recipients of

miserably exploitative wages. The recent boost in the salary of public

servants in Indd (leaving far behind those who are served by the

public servants, sfrch as agricultural and industrial labourers) has led

to a very substantial rise in the. remuneration of school teachers (as

pubhc servants), ill over India. The primary school teachers in West

Bengal, where oifr study was conducted, now tend to get between Rs.

5,000 and 10,006 per month, in the form of salary and allowances,

which comparesjwith the total salary of teachers in the alternative

schools - called Sflshu Siksha Kendras - of Rs. 1,000 per month.

The salary of rtachers in regular schools has gone up dramatically

over recent years even in real terms, that is, after correcting for price

changes This is an obvious cause for celebration at one level (indeed,

I remember beinfe personally involved, as

as aa scudent

student at Presidency

College fifty years ago, in agitations to raise the despe:

_ irately low pre

vailing salaries df school teachers).

1

'

' But

"___the

_ situation is now very

different. The big salary increases in recent years have

ula

5 not only made

school education! vastly more expensive (making ft much harder to

offer regular schobl education to those who are still excluded from it)

but have also tentied to draw the school teachers as a group further

1

t

i

J

ii

THE akgumentative Indian |

CLASS IN INDIA

f

7 eauMtlon to the

urst-ott members of society is now furrk

X Con^ding Remark

d“

J- ■

social------progress of the cnimt-r,, economic,

.

barriers to progress coxne not only from owl"?5'

Th'

------ ic

from new ones. Sometimes thr

?

d hiding lines, but also

iat M ere created to

act is reactionary

fB

positive hopes of equi^o J t

^mp,e °f re

administration of primary education, though making room for effec

tive parent-teacher committees for individual schools, with legal

authority. With the help of the countervailing power of the interest

group most directly involved - that is, parents - the role of teachers’

unions can be mlade more constructive. Similarly, on the former

problem, the food mountains can be turned into assets rather than

liabilities, with an appropriate focus on the interests of the worst-off

members of the society (for example through use in school meals).*

These and other policy changes call for urgent action and consid

eration. That process can be facilitated by clear analysis of the exact

effects of actual and possible public policies. It is important to prevent

‘friendly fire’ as |Well as to press for policies that can make a real

difference to the ihequalities of class division in India. It is crucial to

scrutinize the benefits to be obtained and the losses to be sustained by

the different classes and occupation groups, resulting from each policy

proposal. The ubiquitous role of class divisions influences social

arrangements in t imarkably diverse ways and deserves a fuller recognition than it has tended to get in the making of Indian public policy.

There is something serious to argue about here.

payment of subsidies have to 3 ™

t?POrt price of fo°d and

considerable T'

extent,’ 4

tekded

r- Pr°'

duce exactly the opposite effect Anothl"

ded C0

tutional features of delivery of nrim

Xa.mple re,at“ » theinsti-

inter^estheneglect^^X^

barriers

teachers from the tmpoverished

Ther<!is eviden«

the

I

of pessimism.

the two cases considered, possible li Y

Jdentlfied decencies.lagIn

?

!

On the latteg the report of the P ar k 7

n0‘ H to

see.

>cy suggestions, which includt emnh^ rUStumakes a nu4" Pol-

i

m school management. This would rec '

erprl''lleged sections,

would requtre a restructuring of the

*The recent initiative

of ---theLUIndian

government (in late 13.004.) to help provide

---- 11

iicip proviac

cooked midday meals

sals, jin schools across the country is a very positive move that has

emerged since the Nehru

Lecture----was es'

given

initiative, nmui

which it

followed

i|---- ----------------’-** in 1001. This

Aino mjuuurv,

________

directly from the Indian Supreme Court’s visionary decision to cover this right

w r among

the entitlements of children,

Idren, has favourable potential in simultaneously addressing the

twin problems of child undernourishment and school absenteeism. It has had much

success in states (such as Tamil Nadu) where it has been in use for many years, and it

is beginning to have pc sitive effects where it is just being introduced. Investigations by

the Pradchi Trust team in West Bengal record higher school attendance and a high level

of satisfaction from th j poorer families

o

Central

Globalization and Health

Open Access

Globalization and social determinants of health: Introduction and

methodological background (part I of 3)

Ronald Labonte and Ted Schrecker*

Canada

Email Ronald Labontf - rlabonte@uottawa.ca; Ted Schreckef - uehrecker@rympalico.ca

‘ Corresponding author

Received: 24 July 2006

Accepted. 19 June 2007

Published: 19 June 2007

Globalization and Health 2007. 3:5

doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-3-5

This article is available from: http://www.globalizationandhealth.eom/content/3/l/5

© 2007 Labonte and Schrecker, licensee BioMed Central Ltd

Cw...-^5 Attribution License

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

>y medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproducuon in an)

healthy lives.

Social Determinants of Health and in the Commissions specific concern w,th health equrt

We

health outcomes.

~~

)

)

)

)

>

)

------------

Background: health equity and the social

determinants of health

This article is the first in a series of three that together

describe research strategies to address the relation

between contemporary globalization and the social deter

minants of health (SDH) through an 'equity lens, and

invite dialogue and debate about preliminary findings.

The global commitment to health equity is not new; m

1978 the landmark United Nations conference in AlmaAta declared the goal of heMth for all by theyear 2000 [IJ_

Yet in 2007, despite progress toward that goal, millions o

people die or are disabled each year from causes that are

easily preventable or treatable |2], Recent reviews [3,4] of

------------

research on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, commu

nicable diseases that together account for almost six mil

lion deaths per year, identify poverty, gender inequality,

development policy and health sector ’reforms tha

involve user fees and reduced access to care as contribu

tors More than 10 million children under the age of five

die each year, "almost all in low-income countnes or poor

areas of middle-income countries" [5](p. 65; see also (6])

and from causes of death that are rare in the industnabzed

world Undernutrition - an unequivocally economic phe

nomenon, resulting from inadequate access to the

lesources for producing food or the income for Purchas

ing it - is an underlying cause of roughly half these deaths

Page 1 of 10

(page number not for citation purposes)

)

J

)

J

)

Globalization and Health 2007, 3:5

http://www.globalizationandhealth.eom/content/3/1/5

to transport all contribute to the social gradient. Further

[6], and lack of access to safe water and sanitation contrib

confusing the issue is the inclusion of stress and addic

utes to 1.5 million |7]. An expanding body of literature

tion, with the former arguably a pathway through which

describes a similarly unequal distribution of many nonSDH affect physiology and the latter a response to characcommunicable diseases and injuries, with incidence and

vulnerability-often_directly-related-tO-poverty,_economic----- teristics of the-SOcial environment. Einally,-some of the

discussion is primarily relevant to high-income countries,

insecurity or economic marginalization |8-15|. Three dec

rather than to the majority of the world’s population.

ades of rapid global market integration have occurred in

Nevertheless, the extent to which items in the WHO

parallel with these trends; these articles address the rela

Europe list are related to an individual’s economic situa

tion between these two patterns.

tion and the way in which a society organizes the provi

sion and distribution of economic resources is

Our work follows a trajectory of inquiry initiated by the

informative.

World Health Organization (WHO). In 2001, the WHO

Commission on Macroeconomics and Health turned

Both for this reason and because of the preceding discus

much conventional wisdom on its head by demonstrating

sion of how global patterns of illness and death are related

that health is not only a benefit of development, but also

to economic factors, we do not distinguish between ’eco

is indispensable to development |16j. Illness all too often

nomic* and 'social' determinants of health. In addition,

leads to “medical poverty traps" [17], creating a vicious

we consider health systems as a SDH, for two reasons.

circle of poor nutrition, forgone education, and still more

Although the entire rationale for a policy focus on SDH is

illness - all of which undermine the economic growth

that health is affected by much more than access to health

that is necessary, although not sufficient, for widespread

care,

access to care is nevertheless crucial in determining

improvements in health status. Like the earlier Alma-Ata

health outcomes and often reflects the same distributions

commitment to health for all, most of the Commission’s

of (dis)advantage that characterize other SDH - a point

recommendations, which it estimated could have saved

made eloquently in the context of developing and transi

millions of lives each year by the end of the current dec

tion

economies oy Paul Farmer [20]. Further, how health

ade, have not been translated into policy. Further, the

care is financed functions as a SDH. As noted earlier lack

Commission did not inquire into how the economic and

of access to publicly funded care can create destructive

geopolitical dynamics of a changing international envi

downward spirals in terms of other SDH when house

ronment (’globalization1) support and undermine health,

holds have to pay large amounts out of pocket for essen

or how these dynamics can be channelled to improve

tial services, lose earnings as a result of illness, or both.

population health.

The importance of this dynamic in a number of Asian

countries is emphasized in recent work by van Doorslaer

In 2005, WHO established the Commission on Social

and colleagues [21].

Determinants of Health (CSDH), on the premise that

action on SDH is the fairest and most effective way to

We start from the premise that the processes comprising

improve health for all people and reduce inequalities.

globalization affect access to SDH by way of multiple

Central to the Commission’s remit is the promotion of

pathways, which we describe in the second article in the

health equity, which is defined in the literature as "the

series. Because of our focus on health equity (or reducing

absence of disparities in health (and in its key social deter

health inequities) and the fact that the effects of globalizaminants) that are systematically associated with social

mi- ^ tioirTnFSDFFinF^lmost-nev^^

ildvantage/disadvantage^[Tg]Xp^25&)^Socral^TOr

’

across populations, our focus in these articles is on how

nants of health, broadly stated, are the conditions in

globalization affects disparities in access to SDH. The

which people live and work that affect their opportunities

’equity lens’ also informs our concentration on what

to lead healthy lives. Good medical care is vital, but unless

might be described as negative effects of globalization: we

the root social causes that undermine people's health are

presume that disparities in access to SDH lead to deterio

addressed, the opportunity for well being will not be

ration in the health status of those adversely affected, and

achieved.

that when the result is to inaease health inequity that

deterioration is unacceptable even if offset by positive

Beyond this general statement; no simple authoritative

impacts (e.g. improved health for the well-off) elsewhere

definition or list of SDH exists. The European Office of

in the economy or the society. Stated another way, we

WHO [ 19] enumerates SDH under topic headings includ

regard as prima facie undesirable changes in access to SDH

ing the social gradient of (dis)advantage, early childhood

that are likely to increase the socioeconomic gradients in

environment, social exclusion, social support work,

health that are observable in all countries, rich and poor

unemployment, food and transport. Although the scope

of this inventory is impressive, it mixes categories: for

alike [22].

example working conditions, unemployment and access

( '

(

(

(

(

(

(

C

c

<

(

c

(

Page 2 of 10

(page number not for citation purposes)

(

(

c

http://wvwv.globalizationandhealth.eom/content/3/1/5

Globalization and Health 2007, 3:5

I

I

The outline of this series is as follows. The remainder of

this article identifies and defends a definition of globali

zation and describes key strategic and methodological

issues, emphasizing how and why lire special characteris

tics of globalization as a focus of research on health equity

and SDH demand a distinctive perspective and approach.

The second article describes a number of key ’dusters' of

pathways leading from globalization to equity-relevant

changes in SDH. Building on this identification of path

ways, the third article provides a generic inventory of

potential interventions, based in part on an ongoing pro

gram of research on how policies pursued by the G7/G8

countries affect population health outside their borders

123-29]. It then concludes with a few observations about

the need for fundamental change in the values tlial guide

industrialized countries' policies toward the much larger,

and much poorer, majority of the world’s population liv

ing outside their borders.

)

expand profits and markets), even as it contributes to the

"global production of diet" {38] and resulting rapid

increases in obesity and its health consequences in much

of the developing world.

The definition of globalization we adopt does not ignore

global transmission of ideas and information that are not

commercially produced - but here again, reasons exist to

focus on economic issues and on the interplay of ideas

and interests. Perhaps the most conspicuous illustration

of this point is the embrace of 'free' markets and global

integration as the only appropriate bases for national

macroeconomic policy - a phenomenon that leads us to

examine some of the key drivers of globalization, as dis

tinct from the manifestations of globalization processes

themselves. To provide historical context, Polanyi s [39]

research on the development of markets at the national

level showed that markets are not ‘natural,’ but depend on

the creation and maintenance of a complicated infrastruc

ture of laws and institutions. This insight is even more

Globalization and the global marketplace

salient at the international level: "It is a dangerous delu

Globalization is a term with multiple, contested defini

sion to think of the global economy as some sort of ’nat

tions and meanings [30]. Here we adopt a definition of

ural’ system with a logic of its own: It is, and always has____

___ globalization as “a process of greater integration within

been, the outcome of a complex interplay of economic

the world economy through movements of goods and

and political relations" [40](p. 3-4). The connection

services, capital, technology and (to a lesser extent)

between ideas and economic interests is supplied by the

labour, which lead increasingly to economic decisions

fact that that contemporary globalization has been pro

being influenced by global conditions’ [31](p. 1) - in

moted, facilitated and (sometimes) enforced by political

other words, to the emergence of a global marketplace. This

choices about such matters as trade liberalization, finan

definition does not assume away such phenomena as the

cial (de)regulation; provision of support for domestically

increased speed with which information about new treat

headquartered corporations [42]; and the conditions

ments, technologies and strategies for health promotion

under which development assistance is provided. We

can be diffused, or the opportunities for enhanced politi

regard contemporary globalization as having emerged in

cal participation and social inclusion that are offered by

roughly 1973 with the start of the first oil supply crisis, the

new, potentially widely accessible forms of electronic com

resulting impacts on industrialized economies, and the

munication. However, in contrast to simply descriptive

investment of ’petrodollars’ in high-risk Ioans to develop

accounts of globalization that do not attempt to identify

ing countries that contributed to the early stages of the

connections among superficially unrelated elements or to

developing world's debt crises. However, identifying a

assign causal priority to a specific set of drivers (e gprecise starting point is less important than recognizing

132,331), we adopt the view of Woodward and colleagues

fores-th-atsometimrtii the ^ly1770sthewoTld^conornicynrf

lfiar’_[e]conorhic g

geopolitical environment changed decisively, so that (for

behind the overall process of globalization over the last

instance) by 1975 the Trilateral Commission was warning

two decades" [34](p. 876). This view is supported by evi

of a "Crisis of Democracy" in the industrialized world

dence that many dimensions apd manifestations of glo

[41]. By the mid-1990s, a consortium of social scientists .

balization that are not at first glance economic in nature

convened

to assess the prospects for "sustainable democ

are nevertheless best explained with reference to their con

racy" noted that key Western governments have promoted

nections to the global marketplace and to the interests of

an "intellectual blueprint ... based on a belief about the

particular powerful actors in that marketplace. For exam

virtues

of markets and private ownership " with the conse

ple, the globalization of culture is inseparable from, and

quence that: "For the first time in history, capitalism is

in many instances driven by, the emergence of a network

being adopted as an application of a doctrine, rather than

of transnational mass media corporations that dominate

evolving as a historical process of trial and error"[43](p.

not only distribution but also content provision through

viii).

the allied sports, cultural and consumer product indus

tries [35-37]. Belatedly, global promotion of brands such

The blueprint has been promoted and implemented by

as Coca-Cola and McDonald s is a cultural phenomenon

national governments both individually and through

but also an economic one (driven by the opportunity to

______ —

______

)

)

)

J

)

.

—1

' - ■

x

*

"

_ —W

■ ■ -

,,

..-I

■

I

~1'

*'*

-

-w-

i

■

1 ■

1 • n——I .1 >

it1

*

Page 3 of 10

(page number not for citation purposes)

J

J

)

J

Globalization and Health 2007, 3:5

multilateral institutions like the World Bank, the Interna

tional Monetary Fund (IMF) and more recently the World

Trade Organization [43-46]. Within these institutions, the

distribution of power is highly unequal: The G8 nations

(the G7 group of industrialized economies plus Russia)

"account for 48% of the global economy and 49% of glo

bal trade, hold four of the United Nations’ five permanent

Security Council seats, and boast majority shareholder

control over the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and

the World Bank" [47]; their influence on World Bank and

IMF policies is magnified because some decisions require

supermajorities [48] (p. 27-8). Networks of academic and

professional elites, often with connections to industrial

ized country governments and institutions like the World

Bank and IMF, have likewise played an important role in

the outward diffusion of market-oriented ideas about pol

icy design, as shown e g. by the work of Babb [49] on aca

demic economists in Mexico, Lee & Goodman [50] on the

World Bank’s role in promoting health sector ’reform’,

and Brooks |51|(p. 54-65) and Mesa-Lago and Muller

[ 52] (p. 709-712) on the Bank's role in promoting priva

tization of public pension systems, especially in Latin

America.___________________ _____________________

http://www.globalizationandhealth.eom/content/3/1/5

protection has created barriers to access to essential med

icines J59],

Some women's health movements, as another example,

have become "transnationalized," partly within, and

shaping the agenda of, the institutional framework pro

vided by the UN system [60]. CSOs have also been impor

tant actors in the admittedly uneven and incomplete

international diffusion of human rights norms in the dec

ades following the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human

Rights - norms to which we return in the third article as a

potential challenge to the current organization of the glo

bal marketplace. Thus, although we insist on the primacy

of the economic dimensions of globalization, and on the

economic elements of SDH, our view is not narrowly

deterministic, and allows for the possibility of effective

challenges to the interests that dominate today's global

economic and political order.

Globalization and social determinants of health:

Recent conceptual milestones

To be sure, the diffusion of ideas as an element of globali

zation involves more than just ideas about markets, and

some aspects of the process function as an important

counterbalance. Notably, civil society organizations

(CSOs) in various policy fields have taken advantage of

opportunities for rapid transnational information sharing

opened up by advances in computing and telecommuni

cations - the indispensable technological infrastructure of

globalization, which cannot be understood in isolation

from the needs of its corporate users [53] yet is amenable

to use for quite different purposes. Perhaps the bestknown illustration of the political influence of CSOs as

they relate to health and globalization is their role in chal

lenging the primacy of economic interests as defended by

multilateral institutions. In the 1990s, CSO activity con-

As background to a discussion of research methods and

strategies, it is worthwhile to provide a selective overview

of previous conceptual milestones that have contributed

to understanding the influences on SDH. A 1987 UNICEF

publication on Adjustment with a Human Face [61]

reported early and important findings on how what we

would now call globalization was affecting SDH. The

study involved 10 countries (Botswana, Brazil, Chile,

Ghana, Jamaica, Peru, Philippines, South Korea, Sri

Lanka, Zimbabwe) that had adopted policies of domestic

economic adjustment in response to economic crises that

led them to rely on loans from the IMF L a dynamic that

is described in the second article of the series. In many

cases the policies adopted had resulted in deterioration in

key indicators of child health (e.g. infant mortality, child

survival, malnutrition, educational status) and in access to

SDH (e.g. availability and use of food and social services),

with reductions in government expenditure on basic serv-

eral Agreement on Investment by the French government,

and their subsequent abandonment by the Organization

for Economic Cooperation and Development [54]; in the

early 2000s, it resulted in an interpretation of the Agree

ment on Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property

(TRIPs) that allows health concerns, under some circum-,

stances, to ’trump’ the harmonized patent protection that

was actively promoted by pharmaceutical firms during the

negotiations that led to the establishment of the WTO

[55-58]. However, concerns remain about the practical

effect of this interpretation because of informal pressures

from the pharmaceutical industry and industrialized

country governments and TRIPs-plus’ provisions in bilat

eral trade agreements, and one academic observer is scep

tical ^about the extent to which intellectual property

uated these national cases within an analytical framework

that linked changes in government policies (e.g. expendi

tures on education, food subsidies, health, water, sewage,

housing and child care services) with selected economic

determinants of health at the household level (e.g. food

prices, household income, mothers’ time) and selected

indicators of child welfare f 62 J. Based on that analysis, the

study identified a generic package of policies that would

minimize the negative effects of economic adjustment by

protecting the basic incomes, living standards, health and

nutrition of the poor or otherwise vulnerable [63] — prior

ities that have similarly been stressed in subsequent policy

analyses. However, in the context of globalization an

important limitation is that only the final chapter of the

UNICEF study [64] addressed elements of the intema-

Page 4 of 10

r

r

(page number not for citation purposes)

r

http://'www.globalizationandhea[th.com/content/3/1/5

Globalization and Health 2007, 3:5

F

Hi

tl

1

............ '

/, 'v

■

< 11,

E8

1=

i