12127.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

1

Hunger, Under-nutrition and Food Security in India

NC Saxena

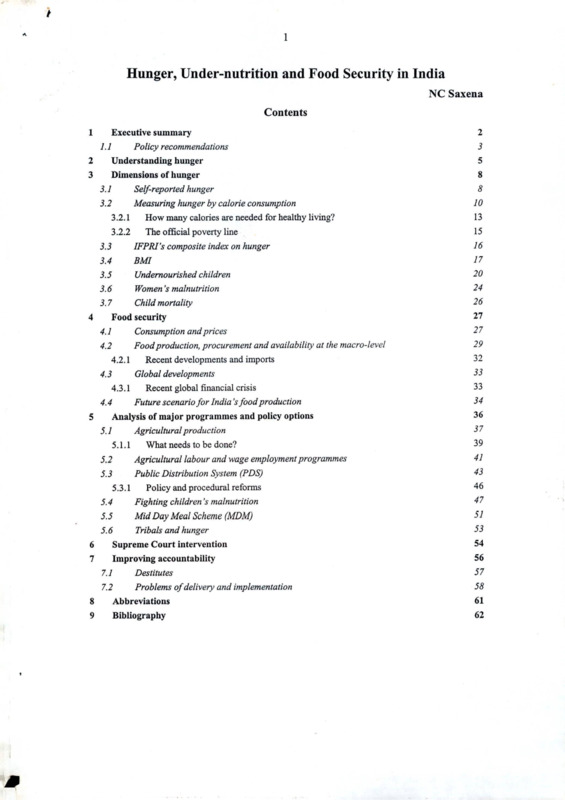

Contents

1

Executive summary

1.1

2

3

Policy recommendations

Understanding hunger

Dimensions of hunger

Self-reported hunger

3.1

Measuring hunger by calorie consumption

3.2

3.2.1

How many calories are needed for healthy living?

3.2.2

The official poverty line

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

3.7

4

IFPRTs composite index on hunger

BMI

Undernourished children

Women's malnutrition

Child mortality

Food security

Consumption and prices

4.1

Food

production, procurement and availability at the macro-level

4.2

Recent developments and imports

Global developments

4.3

Recent global financial crisis

4.3.1

4.2.1

Future scenario for India’s food production

4.4

Analysis of major programmes and policy options

5

Agricultural production

5.1

What needs to be done?

Agricultural labour and wage employment programmes

5.2

Public Distribution System (PDS)

5.3

Policy and procedural reforms

5.3.1

Fighting children’s malnutrition

5.4

5.1.1

2

3

5

8

8

10

13

15

16

17

20

24

26

27

27

29

32

33

33

34

36

37

39

41

43

46

47

5.5

Mid Day Meal Scheme (MDM)

Tribals and hunger

5.6

Supreme Court intervention

6

Improving accountability

7

Destitutes

7.1

51

53

Problems of delivery and implementation

7.2

8

Abbreviations

9

Bibliography

58

54

56

57

61

62

2

1

Executive summary

This paper examines the hunger and nutrition situation prevailing in India and

suggests policy measures for ensuring adequate food security at the household level,

particularly for marginalised groups, destitutes, women and children.

I

Despite rapid economic growth in the last two decades India is likely to slip behind

the first Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of cutting the proportion of hungry

people by half. Per capita availability as well as consumption of foodgrains in India

has declined since 1996; the percentage of underweight children has remained

stagnant between 1998 and 2006; and the calorie consumption of the bottom half of

the population has been consistently declining since 1987. In short, all indicators point

to the hard fact that endemic hunger continues to afflict a large proportion of Indian

population.

Hunger in simple terms is the desire to consume food. However due to an inadequate

diet over time the human body gets used to having less food than is necessary for

healthy development, and after a while the body does not even demand more food. In

such cases hunger is not expressed, though lower intake of essential calories, proteins,

fats, and micro-nutrients would result in under-development of the human mind and

body. Thus objective indicators such as calorie consumption, body mass index (BMI),

the proportion of malnourished children, and child mortality capture hunger more

scientifically than the subjective articulation by individuals.

Surveys on self-reported hunger depend on the responses of the head of the

household, often a man, who may not admit that he cannot provide even two square

meals to his dependents. Pride, self-image and dignity are issues here, which lead to a

deep sense of shame and reluctance on the part of the head of the households to

publicly admit their incapacity to provide for their families. This may result in under

reporting on the number of meals family members are able to afford. Despite this

limitation, a recent UNDP survey (2008) of 16 districts in the seven poorest states of

India showed that for 7.5 per cent of respondents access to food is highly inadequate,

and for another 29 per cent of the households it is somewhat inadequate. A West

Bengal government survey too reported that 15 per cent families were facing

difficulties in arranging two square meals a day year round. These figures are

gloomier than the NSSO survey of the Ministry of Programme Implementation and

Statistics claiming a drastic decline in self-reported hunger in India from 16.1 to 1.9

percent in the last twenty years.

However, NSSO’s calorie data shows that at any given point in time the calorie intake

of the poorest quartile continues to be 30 to 50 percent less than the calorie intake of

the top quartile of the population, despite the poor needing more calories because of

harder manual work. The data also shows higher reliance of the poor on cereal based

calories because of lack of access to fruits, vegetables and meat products. Second,

daily calorie consumption of the bottom 25 per cent of the population has decreased

from 1,683 kcalories in 1987-88 to 1,624 kcalories in 2004-05. These figures should

be judged against a national norm of 2,400 and 2,100 kcalories/day for rural and

urban areas fixed by GOI in 1979. Similar downward trend is observed for cereal

consumption too. As the relative price of food items has remained stable over the past

twenty years, declining consumption can be attributed to the lack of purchasing power

and contraction of effective demand by the poor, who are forced to spend a greater

3

part of their limited incomes on non-food items like transport, fuel and light, health,

and education, which have become as essential as food.

Calorie intake refers to the most proximate aspect of hunger, but it neglects other

effects of hunger, such as being under-weight and mortality. These are captured by

the Global Hunger Index (GHI) which was designed by IFPRI based on three

dimensions of hunger: lack of economic access to food, shortfalls in the nutritional

status of children, and child mortality, which is to a large extent attributable to

malnutrition. IFPRI estimated the hunger index for India as 23 per cent in 2008,

which placed India in the category of nations where hunger was ‘alarming’, with

Madhya Pradesh being categorised as ‘extremely alarming’. Worse, its score was

poorer than many Sub-Saharan African counties, with a lower GDP than India’s.

This is primarily because of the fact that anthropometric indicators of the nutritional

status for children in India are among the worst in the world. According to the

National Family Health Survey, the proportion of underweight children remained

virtually unchanged between 1998-99 and 2005-06 (from 47 to 46 percent for the age

group of 0-3 years). These are appalling figures, which place India among the most

“undernourished” countries in the world.

Higher child malnutrition rate in India (for that matter in the entire South Asia) is

caused by many factors. First, Indian women’s nutrition, feeding and caring practices

for young children are inadequate. This is related to their status in society, early

marriage, low weight at pregnancy and their lower level of education. The proportion

of infants with a low birth weight in 2006 was as high as 30 per cent. Underweight

women produce low birth-weight babies which become further vulnerable to

malnutrition because of low dietary intake, lack of appropriate care, poor hygiene,

poor access to medical facilities, and inequitable distribution of food within the

household.

Second, many unscientific traditional practices still continue, such as delaying breast

feeding after birth, no exclusive breastfeeding for the first five months, irregular and

insufficient complementary feeding after between 6 months to two years of age, and

lack of disposal of child’s excreta because of the practice of open defecation in or

close to the house itself. Clearly government’s communication efforts in changing the

age old practices are not working well.

And lastly, poor supply of government services, such as immunisation, access to

medical care, and lack of priority to assigned primary health care in government

programmes also contributes to morbidity. These factors combined with poor food

availability in the family, unsafe drinking water and lack of sanitation lead to high

child under-nutrition and mortality. About 2.1 million deaths occur annually in under5 year-old children in India. Seven out of every 10 of these are due to diarrhoea,

pneumonia, measles, or malnutrition and often a combination of these conditions.

I

I

I

1.1 Policy recommendations

First, revamp small holder agriculture. Because of stagnating growth in agriculture

after the mid-1990s there has been employment decline, income decline and hence a

fall in aggregate demand by the rural poor. The most important intervention that is

needed is greater investment in irrigation, power, and roads in poorer regions. It is

essential to realize the potential for production surpluses in Central and Eastern India,

where the concentration of poverty is increasing.

■>

5

six times a day in appropriate quantities for the infant, which alone can improve the

infant’s nutrition levels. For nutrition to improve, we have to strengthen proper

breastfeeding and complementary feeding, together with complete immunisation and

prompt management of any illness.

Ninth, cover all adolescent girls under ICDS. They need to be graded according to

age, such as 10-15 group, 16-19 group and pregnant girls. Then they should be

weighed regularly, and given appropriate nutritious food containing all the desired

micro-nutrients and iron. Similar initiative is needed for all women.

Tenth, establish ICDS centres on priority within one year in all primitive tribal group

(PTG) settlements and the most discriminated Scheduled caste (SC) - previously the

untouchable people - settlements, without any ceiling of minimum children; and all

other hamlets with more than 50 per cent SC, ST, or minority populations within two

years. In all these centres, ICDS staff should be locals from the discriminated

communities, and two hot meals should be served instead of one to children aged 3 to

6 years; and weaning foods be given at least twice daily to children below 3 years.

Eleventh, prepare a comprehensive list every two years of all destitutes needing free

or subsidized cooked food. Open up mid-day meals kitchen to these old, destitutes

and hungry in the village. This is already being done in Tamil Nadu, and its

replication in other states should be funded by the GOI. Establish community kitchens

across cities and urban settlements to provide inexpensive, subsidised nutritious

cooked meals near urban homeless and migrant labour settlements.

Last, India requires is a significant increase of targeted investments in nutrition

programs, clinics, disease control, irrigation, rural electrification, rural roads, and

other basic investments, especially in rural India, where the current budgetary

allocations are inadequate. Higher public investments in these areas need to be

accompanied by systemic reforms that will overhaul the present system of service

delivery, including issues of control and oversight (Bajpai et al. 2005). Outlays should

not be considered as an end in itself. Delivery of food based schemes requires

increasing financial resources, but more importantly the quality of public expenditures

in these areas. This in turn requires improving the governance, productivity and

accountability of government machinery.

2 Understanding hunger

In the last decade and a half that India has successfully embraced economic reforms, a

curious problem has haunted the country and vexed its policy makers. India s

excellent growth has had little impact on food security1 and nutrition levels of its

population. Per capita availability as well as consumption of foodgrains has

decreased; cereal intake of the bottom 30 percent continues to be much less than the

cereal intake of the top two deciles of the population despite better access of the latter

group to fruits, vegetables and meat products; calorie consumption of the bottom half

of the population has been consistently decreasing since 1987; unemployment among

agricultural labour households has sharply increased from 9.5 per cent in 1993-94 to

15.3 per cent in 2004-05 (Planning Commission 2006); the percentage of underweight

children has remained stagnant between 1998 and 2006; and more than half of India s

women and three-quarters of children are anaemic with no decline in the last eight

1 The commonly accepted definition adopted at the 1996 World Food Summit is: Food security is

achieved when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and

nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

6

years. In short, all indicators point to the hard fact that endemic hunger continues to

afflict a large proportion of Indian population. Internationally, India is shown to be

suffering from alarming hunger, ranking 66 out of the 88 developing countries studied

(IFPRI 2008). India as part of the world community has pledged to halve hunger by

2015, as stated in the Millennium Development Goal 1, but the present trends show

that this target is unlikely to be met.

This paper examines the hunger and nutrition situation prevailing in the country and

reviews the obligations and initiatives by the government of India (GOI) to ensure

food security through various policies and schemes.

Structure of the paper - In this section we look at various forms of hunger and make

a distinction between explicit hunger and chronic or endemic hunger that manifests

itself in the lower intake of essential calories, proteins, fats, and micro-nutrients

resulting in the under-development of the human mind and body. Section three

examines data, both from government and other sources on self-reported hunger. It

also discusses India’s record in improving its position on various indicators that are

generally used to measure hunger, such as calorie consumption, body mass index

(BMI), proportion of malnourished children, and child mortality.

The fourth section analyses various aspects of food security both at the micro- and

macro levels. The reasons for the decline in food consumption are analysed, followed

by a brief discussion on the recent global trend of reduced availability and increasing

prices. The fifth section is devoted to suggesting changes in some of the major

policies and programmes that affect food security; such as agricultural production,

public wage works, Public Distribution System, Midday Meals Scheme, and the

Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme for improving child

malnutrition. This is followed by a brief report on the Supreme Court intervention on

hunger related matters, and then the paper ends with a discussion on accountability,

which is a cross-sectoral issue.

Types of hunger - There are essentially two types of hunger (Gopaldas 2006). The

first is overt (or raw) hunger, or the need to fill the belly every few hours. Hunger in

simple terms is the desire to consume food. It can also be termed as self-reported

hunger, whereby people judge their own ability to fulfil the physiological urge to

satisfy their hunger.

The second type of hunger occurs when the human body gets used to having less food

than necessary for healthy development, and after a while the body does not even

demand more food. If people have always eaten less than their needs, their bodies

adjust to less food in what is known as biostatis (Krishnaraj 2006). It is also possible

to fill up the stomach with non-nutritious food, which does not provide the required

calories or micro-nutrients2 like vitamins, iron, iodine, zinc, and calcium that are

required in tiny amounts. Another situation could be when the essential calories,

proteins, fats and micronutrients are not absorbed in the body due to ill-health and

poor hygiene. In all such cases hunger is not articulated.

The second kind of hunger may be termed as chronic or endemic hunger as this is not

felt, recognised or voiced by children or adults. Chronic hunger does not translate into

pangs of hunger, but into subtle changes in the way the human body develops. For

2 Deficiency of micro-nutrients is often referred to as hidden hunger. However, micro-nutrients do not

work unless the person is consuming sufficient calories through proper quantity of fat, protein, etc.

7

instance, an under-fed child may be underweight or stunted for his age, if not

consuming sufficient calories and fats. If the child is deficient in Vitamin A, he or she

will not be able to see properly at dusk (“night blindness ), and respiratory ailments

may also occur. In severe Vitamin A deficiency, the child may go totally blind. In the

case of iron-deficiency anaemia, the child will slow down both mentally and

physically, perform poorly in school and experience chronic tiredness. In the case of

iodine deficiency, there will be mental retardation. In its severe form, a goitrous lump

may grow at the base of the neck. Thus prolonged hunger means a predetermined

‘physiological requirement’ or ‘human potential’, defined in terms of norms for

calorie and other essential nutrients and growth standards is not reached.

Subjective hunger, or the first kind of hunger is a matter of articulation — people or

populations have to indicate in some fashion that they are going hungry. This means

there must be a state of not being hungry, so that the state of being hungry can be

recognised as such. What if, not having such a base level, they cannot recognise or

articulate hunger? What if they have always had less food than they need? If body

gets used to having less food than needed, then hunger may never be articulated. Self

reported hunger is also difficult to measure, since perceptions of hunger differ from

one person to another. Therefore objective indicators offer a better measure for

hunger, such as calorie consumption, body mass index, stunting, lack of sufficient

variety in food intake, as it is perfectly possible to have a full belly and yet display

every symptom of under-nutrition.

There is a link between nutritional status or health and human effort and productivity.

Hunger affects the ability of individuals to work productively, think clearly, and resist

disease. Hunger may lead to low output and hence poor wages. Hunger is thus both

cause and effect of poverty. Hunger in India has gender and age dimensions too.

Women, children and the old people are less likely to get full nutritious meals needed

for their development. Half of the country’s women suffer from anaemia and maternal

under-nourishment, resulting in maternal mortality and underweight babies. There are

important seasonal variations in nutritional and health status depending on the cycle

of agricultural work. Hunger and starvation also have regional and geographical

dimensions. Tribal regions in India have higher incidence of food insecurity than the

non-tribal regions in the same state. Agriculture has brought uneven development

across regions and is characterized by low levels of productivity and the degradation

of natural resources in tribal areas, leading to low crop output and reduced gathering

from CPRs (Common Property Resources).

Hunger can also be equated with chronic food insecurity as both refer to a situation in

which people consistently consume diets inadequate in calories and essential

nutrients. This often happens due to the inability to 'access food for lack of

purchasing power. Destitution, leading in extreme cases to starvation deaths but in

any case to a life in misery, is more endemic amongst certain groups. These include

persons with disabilities, persons with stigmatizing illnesses such as leprosy or

HIV/AIDS, the elderly and the young who lack family support and single women.

Social and employment factors causing destitution include scheduled caste

population, tribal populations, manual scavengers, beggars, sex workers, landless

labourers and artisans. Persons displaced by natural disasters or development projects

are also often in this group. Due to prolonged deprivation of sufficient food and

recurring uncertainty about its availability these people are forced to lose their dignity

through foraging and begging, debt bondage and low end highly underpaid work, self

8

denial; and sacrifice of other survival needs like medicine or children’s education, and

thus they transfer their misery to the next generation (Mander 2008).

3

Dimensions of hunger

3.1 Self-reported hunger

Various NSSO3 rounds in India from 1983 onwards have statistically measured4 the

first type of hunger, by asking people on the availability of two square meals a day.

The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Trend in self-reported hunger in India from 1983 to 2004-05

Year

Percentage of population reporting hunger

Rural

Urban

Total

18.54

6.33

16.1

1993-94

5.1

1.6

4.2

1999-00

3.3

0.9

2.6

2004-05

2.4

0.5

1.9

1983

Source: Kumaran 2008

Explicit hunger is especially severe in rural Orissa, West Bengal, Kerala, Assam and

Bihar. The non-availability of two square meals a day peaks in the summer months

from June to September with longer periods of suffering in West Bengal and Orissa

(Mehta and Shah 2002).

The data shows a drastic decline in self-reported hunger in India from 16.1 to 1.9

percent, which can be interpreted as a decline in food insecurity in its severest form,

while much was left undone on other fronts like food and nutritional insecurity in its

not so severe form. However how does one reconcile the above data with significant

reduction in cereal intake (see Table 16) over the years? Is that a result of declining

demand or sign of distress?

An Expert Group (GOI, 1993), while evaluating the suitability of using subjective

hunger data for inferring the extent of poverty arrived at two critiques which are

useful for the present context. First commenting on the limited reliability of the data

as an objective measure the Expert Group noted:

Tt has to be kept in mind that the information regarding the adequacy or inadequacy

of food for consumption, elicited through a single probing question, may not always

be free from subjectivity and at the same time may not be adequately precise and

objective. For instance the size of a 'square meal’ would differ not only from person to

person but also from place to place’ (GOI 1993:53).

3 The National Sample Survey Organisaton of the Ministry of Programme Implementation and

Statistics (GOI) conducts surveys on various socio-economic issues annually. The 61st round of the

National Sample Survey (NSS) conducted between July 2004 to June 2005 collected data on household

consumer expenditure on a large sample basis and was the seventh quinquennial survey on the subject.

It covered a sample of 79,298 rural and 45,346 urban households in all the states and union territories

of India.

4 In 1999-2000 and 2004-05 the question asked was, Do all members of your household get enough

food every day’? (NSSO 2007). In earlier surveys the responds were asked about the availability of two

square meals a day for their family members.

9

The second aspect, noted by the Expert Group, relates to the problem of relying on the

male head of households for the information on hunger experienced by other family

members.

‘Very often, particularly in rural India, the head of the family, usually a man, who is

the main respondent in the survey, would not be sufficiently aware of the quantity and

content of meal left for his wife and other female members of the house. Therefore,

this data would probably give only a broad idea about the perceptions of the people on

adequacy of food’ (GOI 1993:54).

There is yet another problem in interpreting the data given in Table 1. Often men, as

bread-winners would hate to admit that they cannot provide even two square meals to

their dependents (Kundu 2006: 120). Issues of pride, self-image and dignity are

involved here, which leads to a deep sense of shame and reluctance on the part of the

head of the households to publicly admit their inability to provide for their respective

families. This may result in under-reporting on the number of meals family members

are able to afford. For these reasons the NSSO data on decline in hunger over the

years cannot be relied upon.

In addition to NSSO, there have been other empirical studies on subjective hunger.

The Government of West Bengal conducted a rural household survey (Roy 2008) in

2006 through the panchayats and rural development department in which 3.5 per cent

of the population reported that they are not assured of even one meal a day. Another

16.5 per cent face difficulties arranging two square meals a day for all months in a

year. In all around 12 million rural people5 (around 2.5 million rural families) do not

get two square meals a day throughout the year.

A survey (UNDP 2007) was done in selected districts by Pratham, a voluntary

organization. The rural residents were asked on the number of meals they consumed

on most days in a year, and the number of clothes the young women in their families

possessed. The results are shown in the figure below.

Fig 1: Percentage of rural households who

70 1

60

“

50 -

40 J

30 1

20 "I

.A;A;7

m eat less than 2 meals a day

-♦-own less than 3 sets of

clothes

10 1

0

I 1111 ’ 11 n

This shows that the number of people consuming less than two meals a day varied

from 5 to 23 per cent in the rural areas of selected districts, whereas the number of

women having just one or two set of clothes was as high as 60 per cent in some

districts.

5 The total population of West Bengal in 2001 was 80 million.

10

A recent UNDP study (2008) selected 16 districts (9 backward and 7 non-backward)

from the backward states and conducted a perception study of households selected at

random in the districts. The finding on access to food is given in Table 2.

Table 2: District-wise distribution of households according to adequacy of access

to food

Highly

Average Some what

Some

Highly

District

State

Inadequate

Inadequate

what

Adequate

Adequate

Total

29.5

8?5

39.5

20.5

2

100

Dungarpur

2

4.5

65.5

25.5

2.5

100

Sitapur

8

24

10

49

9

100

Lalitpur

3.5

5

5.5

76.5

9.5

100

Azamgarh

6

15.5

21.5

41

16

100

Mandla

0.5

2

43.5

50.5

3.5

100

Tikamgarh

14

45.5

23.5

10.5

6.5

100

Gaya

4

16.5

23.5

46

10

100

Muzzafarpur

5.5

4

14

46

30.5

100

Pumia

4.5

3.5

16.5

49.5

26

100

Palamu

17.5

35

40.5

7

0

100

Dumka

12

41.5

37.5

9

0

100

Kanker

10

45

35.5

9.5

0

100

BilasPur

14

69

16

1

0

100

Ganjam

5.5

45

37.5

10

2

100

Keonjhar

2.5

36.5

40

18

3

100

Total

8.69

25.06

29.38

29.34

7.53

100

Number

278

802

940

939

241

3200

Rajasthan

Uttar Pradesh

Madhya

Pradesh

Bihar

Jharkhand

Chhattisgarh

Orissa

Barmer

Thus 7.5 per cent of respondents state that the access to food grains is highly

inadequate, and in about 29 per cent of the households it is somewhat inadequate. It is

only in about 9 per cent of the households which report that access to food grain is

considered highly adequate. However, the district-wise variations are very stark, more

than 76 per cent of the households in Lalitpur have somewhat inadequate access, but

the situation in Muzaffarpur appears very bad with nearly 31 per cent of the

households reporting highly inadequate access. This stresses the need for governance

and monitoring at the district level as very critical.

3.2

Measuring hunger by calorie consumption

Hunger has many faces: loss of energy, apathy, increased susceptibility to disease,

shortfalls in nutritional status, disability, and premature death. No single indicator can

▼

11

provide a complete picture, and that a variety of different indicators should be used in

analysing different aspects of the problem. One needs to measure dietary diversity,

rather than just the consumption of food staples. Some aspects of hunger, such as the

stability of food consumption between seasons and between years, are generally not

captured by the existing data. In this paper we shall use several indicators - calorie

consumption, BMI, low weight and height among children, and anaemia among

women and children - to see how the situation has changed over the years in India.

In this section we focus on hunger-poverty, as measured by calorie deficiency caused by not consuming the energy required by the body. The mean per capita

consumption of calories, protein, and fats as calculated by Deaton and Dreze (2008)

for various NSS rounds is shown below:

Table 3: Mean per capita consumption of calories, protein, and fats.

Fats (gms)

Protein (gms)

Calories (kc)

Urban

Rural

Urban

Urban Rural

Round Rural

Year

37.1

60.3

27/r

MF

58.6

FTF 3TT

59.1“

58.4

36.0

49.6

2,027

w

MF

346“

46.1 “

2,018

1j82“

■54F

■542“

33.6

FT

2,025

2,014

55.4

347“

47.0

2,106

2,020’

58.0

2004 “ "60

^087

"X036" MF

MF

MF

MF

35.5

46.8

2004-5 “61

F047

“^021"

55.4

35.4

47.4 ’

1983

38

2,240

2,070

MF

1987-8

43

2,233

2>5"

63.2

1993-4

50

2j53“

X073"

1999- 0 55

2000- T 56

2001- 2 57

38

2002

■59

2003

2,148

2,155

2,083

55.8“

58.1

39.3

41.9

MF

Thus, in spite of India’s rapid economic growth, there has been a sustained decline in

per capita calorie and protein consumption during the last twenty-five years; fats are

the only major nutrient group whose per capita consumption is unambiguously

increasing. Patnaik (2007) points out that during the same period the calorie intake in

below poverty line households also declined. The calorie intake at poverty line was

2,170 kcal in 1977-78, 2,060 kcal in 1983, 1,980 kcal in 1993-94 and 1820 kcal in

2004-05.

The decline in calorie consumption of the top quartile could be due to more sedentary

life style or to increasing diversity in food intake, but the decline for the bottom

quartile since 1987, as shown in Table 4, cannot be interpreted as a sign of prosperity.

Several inferences can be drawn from Table 4. First, at any given point in time the

calorie intake of the poorest quartile continues to be 30 to 50 percent less than the

calorie intake of the top quartile of the population, despite the poor needing more

calories because of harder manual work. Second, calorie consumption of the bottom

fifty per cent of the population has been consistently descreasing since 1987, which is

a matter of concern. And last, whereas the top quartile derived only 58 per cent

calories from cereals in 2004-05, the bottom quartile still depended on cereals for 78

per cent of its calorie consumption.

12

Table 4: Total and cereal calorie consumption by decile and quartile of per

capita expenditure, rural India, 1983 to 2004-05 (figures in kcal)

Top

Bottom Bottom Second Third

Quartile Quartile Quartile Quartile

decile

Total calories

1,359

1983

1987-88 1788

1993-94 1,490

1,580

2,007

2,328

3,044

^683

2,056

2,334

2,863

1,659

Xooo

2,251

2,702

1999-00 T796

2004-05 1785

L658

1,978

2^50

2?707

1,624

X900

2,143

2,521

1,150

1,309

1,589

1,738

1,974

U2T

1,359

1,598

1,715

1,894

1,203

1,316

1,504

1,591

1,690

1J97

1,289

1,591

1,509

1,566

2004-05 U89

h259

1,690

1730

1,471

Source: Deaton and Dreze 2008

Cereal calories

1983

1987-88

1993-94

1999-00

A similar picture, of the wide gap between the consumption of the bottom 30 per cent

and top 30 per cent, as well as falling calorie consumption over time of all groups

including the lower 30 per cent, emerges when one looks at variation for a longer

period since 1972-73, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: time trends in average per capita energy intake by expenditure classes

3500 -1

3200 2900 15 2600 £ 23002000 1700 1400 -

*

72-73

■

77-78

Rural Lower 30%

93-94

99-2000 2004-05

—«— Rural Middle 40%

Urban Lower 30^/o

J

(Ramachandran 2007)

Another study on hunger (Ahmed et al. 2007) based on the same NSSO data

disaggregated those consuming fewer than 2,200 kcal in India into three groups:

• Subjacent hungry: those consuming more than 1,800 but fewer than 2,200 kcal a day

• Medial hungry: those consuming more than 1,600 but fewer than 1,800 kcal a day

• Ultra hungry: those consuming less than 1,600 kcal a day

13

The study found that in all 58 per cent people in India suffered from hunger in 1999,

of which 17.4 per cent were classified as ultra hungry.

Table 5: Incidence of Hunger in India (1999)

National

Rural

Urban

Subjacent hungry

20

28.9

27.9

Medial hungry

12.1

12.1

12.3

Ultra hungry

17.4

17.1

18.0

Total

58.1

58.1

58.3

3.2.1

How many calories are needed for healthy living?

The calculation of calorie norms or requirements is complicated as the daily calorie

requirement for healthy life is a function of age, sex and nature of work. The required

average for the entire society will decline if rising incomes lead to a shift from manual

to sedentary life style, but would go up if the proportion of working age population

increases as indeed is happening in India due to demographic changes. In the absence

of well accepted norms of calorie consumption for different time periods valid for

India it is difficult to come to any definite conclusion about the percentage of

population that is not able to satisfy the minimum required calorie needs for healthy

living in a particular year.

The Planning Commission constituted a ‘Task Force on Projection of Minimum

Needs and Effective Consumption Demand’ which on the basis of a systematic study

of nutritional requirements recommended (GOI 1979) a national norm of 2,400 kilo

calories/day and 2,100 kilo calories/day for rural and urban areas (the difference bem^

attributed to the lower rates of physical activity in the urban areas) respectively .

These figures were derived from age-sex-occupation-specific nutritional norms by

using the all-India demographic data from the 1971 Census. However, these have not

been revised, and hence the confusion in interpreting subsequent data based on old

norms of calorie consumption.

There is yet another problem in interpreting calorie data, when it is disaggregated to

the Indian states. The diet of people in poorer states, such as Assam, Orissa and Bihar,

is not diversified and they eat more cereals compared to Kerala and Tamil Nadu

where diets include more vegetables, fats, and fish. The result is that per capita calorie

consumption is higher in Orissa and Bihar but in the absence of proteins and essential

fats these states report higher malnutrition than Kerala and Tamil Nadu, as shown in

column 3 of Table 9. Therefore calorie consumption cannot be the sole determinant of

hunger. Because of these problems Deaton and Dreze (2008) concluded that, there is

no tight link between the numbers of calories consumed and nutritional or health

status. Although the number of calories is important, so are other factors, such as a

balanced diet containing a reasonable proportion of fruits, vegetables, and fats, not

just calories from cereals, as are factors that affect the need for and retention of

6 The average calorie norm of 2,110 kcal per capita per day prescribed by the FAO for South Asia

(Bajpai et al. 2005) in the eighties is much lower than the 2,400 kcal norm that has been typically used

by government in India. The latest calorie norm used by FAO for India is 1820 kcal (IFPRI 2008).

14

calories, such as activity levels, clean water, sanitation, good hygiene practices, and

vaccinations.’

The MDGs call for halving of hunger-poverty between 1990 and 2015. Assuming

constant norms of 2400/2100 kcalories for India, this would mean bringing down the

headcount ratio of calorie deficiency from 62.2 per cent in 1990 to 31.1 per cent in

2015. However, the number of people below the norm has consistently increased over

the years, and more than three quarters of the population live in households whose per

capita calorie consumption is less than the norm, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Fractions of the population living in households with per capita calorie

consumption below 2,100 kcal in urban and 2,400 kcal in rural areas

Round Rural Urban All India

Year

1983

38

66.1

60.5

64.8

1987-8

43

65.9

57.1

63.9

1993-4

50

71.1

67.8

1999-0

55

74.2

58.1

58.2

70.1

2004-5

61

79.8

63.9

75.8

(Deaton and Dreze 2008)

The mere consumption of an adequate number of calories may not ensure sufficient

intake of other nutrients, such as proteins, fats and micro-nutrients, which are just as

essential for human health. It can further be argued that there is a distinction between

gross calorie intake and net calorie absorption, and that the relationship between the

two may change over time depending upon the incidence and severity of gastro

intestinal disorders.

Table 7: Percentage of the undernourished population in India below the

threshold levels of protein and fat, 1983 and 1999-2000

Upper Group

Bottom Group

Year

Rural

Urban

All India

Rural

Urban

All India

1983"

51

64

55

9

20

13

1999-00"

65

65

65

14

"14

14

198?

61

40

55

10

4

8

1999-00

48

16

36

“4

I

T

Protein

Fats

(Kumar et al. 2007)

Notes: Bottom group: Below poverty line; Upper group: Above 150 per cent of

poverty line

Table 7 reveals a general decrease in protein consumption, particularly in the bottom

income group in irural

---- areas7,, where the .population below threshold level had

7 The sample households were grouped into poor (bottom) and non-poor (upper) classes. The non-poor

class comprised households which were above 150 per cent of the poverty line, whereas, the poor class

15

increased from 51 per cent to 65 per cent in terms of protein intake. Ideally, the source

of protein should be pulses and meat. But the data showed that cereals contributed 67

per cent of the protein consumed in rural India. It can perhaps be explained in terms

of the lack of purchasing power for procuring an adequate quantity of high-value non

cereal commodities to compensate for loss in nutrition owing to replacement of

cereals.

To conclude this section, there is strong evidence of a sustained decline in per-capita

calorie and protein consumption in India during the last twenty five years. The

proportionate decline was larger among better-off sections of the population, but also

existed for the bottom quartile of the per-capita expenditure scale. While calorie

deficiency is an extremely important aspect of nutritional deprivation, close attention

needs to be paid to other aspects of food deprivation, such as the intake of vitamins

and minerals, fat consumption, the diversity of the diet, and breastfeeding practices.

3.2.2 The official poverty line

The national-level official poverty lines for the base year (1973-74) were expressed as

monthly per capita consumption expenditure of Rs 49 in rural areas and Rs 57 in

urban areas, which corresponded to a basket of goods and services that satisfy the

calorie norms of per capita daily requirement of 2400 kcal in rural areas and 2100

kcal in urban areas. These figures have been updated for price rises for the subsequent

years. However, the new poverty lines do not correspond to the minimum calorie

norm* as the poor have been forced to shift their priorities to essential non-food items.

Therefore for the year 1999-00 the monetary cut-off corresponding to the minimum

calorie requirements norms should have been Rs 565 in rural areas and Rs 628 in

urban areas, whereas by the price updated methodology as used by Planning

Commission the poverty line was Rs 328 and Rs 454 respectively. The current va ue

of the poverty line does not permit the poverty line class to consume the calorific

norm, and the periodic price corrections that have been carried out to update the

poverty lines are inadequate and indeed may be even inappropriate (Sen 2005).

Consequently, the poverty estimates made in the years after 1973-74 understate the

true incidence of poverty in the country. There is a compelling case for re-estimating

the poverty lines. The proportion of people living below the official poverty line

declined from 56 per cent in 1973-74 to 35 per cent in 1993-94, and further to 28 per

cent in 2004-05, whereas there has been no decline in the number of people

consuming less calories than the norm (Table 6). The set of food insecure in India is

larger than the set of poor in India.

Several features of poverty in India stand out. First, poverty is being concentrated in

the poorer states. In terms of absolute numbers, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand

account for around 27 per cent of the country’s population but 30 per cent of India’s

poor lived there in 1973-74, which has increased to over 41 per cent by 2005

(Himanshu 2007). Second, more than three-fourths of the poor live in rural areas.

Third, more than three-fourths of the rural poor depend on agriculture. Agricultural

growth will therefore have greatest potential of poverty reduction.

Fourth, poverty has many social dimensions. There has been hardly any decline in

poverty for the Scheduled Tribe households, almost half of them continue to be below

consisted of households below the poverty line. The poverty line for rural and urban areas in different

states corresponding to various NSS rounds, as defined and adopted by the Planning Commission, was

used in the study.

♦

16

the poverty line. Although poverty among the Scheduled Castes has declined from 46

to 37 per cent during 1993-2004 (Planning Commission 2008), the caste system

confines those from lower castes to a limited number of poorly paid, often socially

stigmatised occupational niches from which there is little escape, except by migrating

to other regions or to towns where their caste identity is less well known. Many states,

especially in the north and western part of the country, are characterised by long

standing and deeply entrenched social inequalities associated with gender. Gender

cuts across class, leading to deprivations and vulnerabilities which are not necessarily

associated with household income.

And lastly, poverty is intimately connected with vulnerability and shocks. Severe and

chronic deprivation in India is compounded by general uncertainty with respect to

livelihood and life, which threatens an even wider section of the population than

might be counted as poor.

Thus poverty is an extremely complex phenomenon, which manifests itself in a range

of overlapping and interwoven economic, political and social deprivations. These

include lack of assets, low income levels, hunger, poor health, insecurity, physical and

psychological hardship, social exclusion, degradation and discrimination, and political

powerlessness and disarticulation. Therefore, policy instruments should be designed

to address not only the low income and consumption aspect of poverty, but also the

more complex social dimensions (Sen and Himanshu 2004).

The existing types of poverty programmes may not be enough to tackle hunger and

food insecurity. Important food security issues are often left out of poverty

programmes, such as the stability of food consumption, dietary diversity, and food

absorption and utilisation. Furthermore, poverty programmes may fail to recognise

how hunger and malnutrition impair people's capacity to participate in productive

activities and result in worse school performance. Hence there is a need to mainstream

hunger in the existing programmes.

3.3 IFPRI’s composite index on hunger

Calorie intake refers to the most proximate aspect of hunger, but it neglects other

effects of hunger, such as under-weight and mortality. These are captured by the

Global Hunger Index (GHI) that was designed to capture three dimensions of hunger:

lack of economic access to food, shortfalls in the nutritional status ot children, and

child mortality, which is to a large extent attributable to malnutrition (Wiesmann et al.

2007). Accordingly, the Index includes the following three equally weighted

indicators: the proportion of people who are food-energy deficient according to the

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO ) estimates, the

proportion of children under the age of five who are underweight according to the

World Health Organization estimates, and the under-five mortality rate as estimated

by UNICEF.

The Global Hunger Index recognizes the interconnectedness of these dimensions, and

therefore captures performance on all the three of them. The index has been an

effective advocacy tool which has brought the issue of global and national hunger to

the fore in policy debates, especially in developing countries. The ranking of nations

on the basis of their index scores has been a powerful tool to help focus attention on

8 According to FAO, after seeing a decline of 20 million in the number of undernourished between

1990-1992 and 1995-1997, the number of hungry people in India increased from 201.8 million in

1995-1997 to 212.0 million in 2001-2003.

17

hunger, especially for countries like India which under-perform on hunger and

malnutrition relative to their income levels.

IFPRI estimated9 that the hunger index for India had declined from 34 per cent in

1990 to 23 per cent in 2008, although India still continued to be in the category of

nations where hunger was ‘alarming’. Worse, its score was poorer than many SubSaharan African counties, which have a lower GDP than India’s. This indicates

continued poor performance at reducing hunger in India.

Table 8: GDP per capita in relation to scores on the Global Hunger Index 2008

Country

GHI2008

GDP per Capita1

nnp

1977“

Nigeria

18.4

18.7

2124

Cameroon

19.9

1535

Kenya

20.5

2088

Sudan

23.7

2753

India

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dollar estimates at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

per capita Source: World Development Indicators, 2007 (World Bank)

A recent IFPRI report (2008) estimated hunger index for 17 major states in India,

covering more than 95 percent of the population of India, shown in Table 9. All 17

states have GHI scores that are well above the “low” and “moderate” hunger

categories. Twelve of the 17 states fall into the “alarming” category, and one Madhya Pradesh - into the “extremely alarming” category. The study concluded that

GHI scores are closely aligned with poverty, but there is little association with state

level economic growth. High levels of hunger are seen even in states that are

performing well economically, such as Gujarat and Karnataka.

3.4 BMI

A widely used measure of nutritional status is a combination of weight and height

measurements known as the Body Mass Index (BMI). Low body weight, associated

with low intakes, is an indication that people could not reach their growth potential

and hence is essentially a sign of continued hunger and nutritional distress. This is

defined as weight in kilogrammes divided by height in metre squared. A BMI of

below 18.5 for adults indicates chronic energy deficiency (CED), which would be due

to an intake of calories and other nutrients less than the requirement for a period of

several months or years.

According to the XI Plan, volume 2 (Planning Commission 2008), in 1998-99 as

much as 36 per cent of the adult population of India had a body mass index (BMI)

below 18.5; eight years later (2005—06) that share had barely fallen to 33 per cent of

the population, despite a decade of robust economic growth. These figures are based

on the NFHS data, which is collected from all the states. Changes in BMI are also

9 IFPRI used a cut-off of 1,632 kcals per person per day as the national calorie under-nutrition norm

which showed 20 per cent calorie deficient people in India. FAO has also used the norm of 1632 kcal,

showing a reduction in the number of under-nounshed population from 25 to 20 per cent during 19902005. Had it used 1,820 kcals per person per day as the cut-off the number of under-nourished

population in 2005 would have been 34 per cent.

18

monitored by the National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB, shown in Table 10),

but it covers only ten10 states.

Table 9: Underlying components of India State Hunger Index and India State

Hunger Index scores

percentage

India

India State

Under-five

Prevalenc Proportio

State

of people

Hunger

Hunger

n

of

mortality

e of

below

Index

Index

score

rate,

calorie underwei

poverty

line

Ranking

ght

underreported as

in

2004-05

among

deaths per

nourishm

hundred

ent children<

5years

2

T

4

5

India

20.0

42.5

7.4

23.31

Andhra Pradesh

19.6

32.7

6.3

19.54

3

15.79

Assam

14.6

36.4

8.5

19.85

4

19.73

Bihar

17.3

56.1

8.5

27.30

15

41.35

Chhattisgarh

23.3

47.6

9.0

26.65

14

40.88

Gujarat

23.3

44.7

6.1

24.69

13

16.75

Haryana

15.1

39.7

5.2

20.01

5

14.03

Jharkhand

19.6

57.1

9.3

28.67

16

40.35

Karnataka

28.1

37.6

5.5

23.74

11

24.98

Kerala

28.6

22.7

1.6

17.66

2

15.04

Madhya

Pradesh

23.4

59.8

9.4

30.90

17

38.29

Maharashtra

27.0

36.7

4.7

22.81

10

30.75

Orissa

21.4

40.9

9.1

23.79

12

46.37

Punjab

11.1

24.6

5.2

13.64

1

8.41

Rajasthan

14.0

40.4

8.5

20.99

7

22.06

Tamil Nadu

29.1

30.0

3.5

20.88

6

22.53

Uttar Pradesh

14.5

42.3

9.6

22.17

9

32.81

West Bengal

18.5

38.5

5.9

21.00

8

24.72

1

I

6

7

27.5

(IFPRI 2008)

10 Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Uttar

Pradesh, Gujarat, and West Bengal

19

Table 10: Nutrition status of Indian adults, 1975-9 to 2004-5 (Body Mass Index)

per cent decline

Proportion ( per cent) of adults with BMI below 18.5

1975-79

1988-90

1996-97

2000-01

2004-05

Men

56

49

46

37

33

Women

52

49

48

39

36

(1975-9 to 2004-5)

41

31

(Deaton and Dreze 2008)

Predictably the percentage of women in rural areas with BMI below 18.5 in 2004-05

was 41.2 according to NNMB, which is twice that among urban women 22.7 (Arnold

et al. 2004). Regarding age distribution, the percentage of women with BMI below

18.5 ranges from 41.7 for the age group 15-19 to 43.2 for 20-24, 39.4 for 25-29, 35.1

for 30-34 and 31.1 for 35-49. Ironically, at the most vulnerable ages when their

reproductive demands are highest women are most deficient. So much for this

country’s esteem for mothers!

The data for each social group is available for 1996-97, shown below:

Table 11: Percentage of population with BMI < 18.5

Overall

47

Scheduled castes

53.2

Scheduled tribes

60.9

Others

46.8

(Sen 2004)

Undemutrition was relatively higher among the lower socio-economic category of

households such as those belonging to SC and ST communities.

A 20 year trend (Sen 2004) based on a large number of studies and the NNMB

surveys of Indians (1977-1996) show that there have been minimal improvements in

the weights of populations (of the same age) in India. The mean weight of children at

five years of age in 1977 was 12.7 kg and 14.1 kg (girls and boys); when compared to

the NCHS (US National Centre for Health Statistics) median weights of 17.7 kg and

18.7 kg, this deficit is of about 4 kg at the age of five. This increased to a deficit of 14

kg and 23 kg by the age of 18, and the mean weights of Indian women and men were

a mere 42.3 kg and 45.4 kg compared to the NCHS standard of 56.6 kg and 68.9 kg.

There was a small improvement in the weights of Indians as they reached the age of

25 (42.8 kg and 49.9 kg), but it was still way below their desirable weight. At and

above the age of 60 they slipped back to mean weights of 39.7 and 47.6 kg. By the

year 1996 the nutritional status of a large number of people had not changed, or

perhaps had improved only marginally. After observing a average weight gain of 1.25

kg to 2.5 kg at each age group, the author notes that these are mean weights, and

approximately half the population in India has lower weights than these (weights as

low as 38 kg) for adults, a condition very close to chronic energy deficiency or

starvation’ (Shatrugna 2001:2). Fast economic growth did not help these people to

gain a significant amount of height or weight.

Similarly, Shatrugna found that the average height of children from 1977 to 1996

increased minimally by 1 cm. Comparing the weight and height gain in high income

groups in India, the author noted that there was a clear potential for improving height

20

and weight of the Indian population as reflected by the considerable weight gain by

high income groups, captured by the field studies. However there is a huge gap

between actual and potential weight and height of the average Indian. In other words,

the under-nutrition is still forcing generations to remain stunted and remain thin, so

they cannot engage in hard work, given the low level of their food intake.

3.5

Undernourished children

Just as for adults, for children too, the anthropometric indicators of nutritional status

in India are among the worst in the world. According to the National Family Health

Survey, the proportion of underweight children remained virtually unchanged

between 1998-99 and 2005-06 (from 47 per cent to 46 per cent for the age group of 03 years). These are appalling figures, placing India among the most undernourished

countries in the world. The overall levels of child under-nutrition in India (including

not only severe but also moderate under-nourishment) are shown in Table 12.

Table 12: Trends in Child Nutrition: NFHS Data

“

Proportion (percentage) of children under the age of

three years who are undernourished

New WHO Standards

NCHS 11 Standards

1992-3

1W9 2005-6

1998-9

2005-6

Weight-for-age

Below 2 SD12

52

47.0

45.9

42.7

40.4

Below 3 SD

20

To

n/a

TT6

To

Below 2 SD

n/a

45.5

38.4

51.0

44.9

Below 3 SD

n/a

20

n/a

rTn

20

Below 2 SD

n/a

15.5

19.1

19.7

22.9

Below 3 SD

n/a

T8

n/a

“6?7

“O

Height-for-age

Weight-for-height

The data for children under five in 2005-2006 is similar to the above,

percentage of under-fives suffering from: underweight, moderate and

severe

percentage of under-fives suffering from: underweight, severe

43

percentage of under-fives suffering from: wasting, moderate and severe

20

percentage of under-fives (suffering from: stunting, moderate and severe

48

16

11 Until 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the US National Centre for Health

Statistics (NCHS) standard, and this was used inter alia in the first and second rounds of the National

Family Health Survey. In April 2006, the WHO released new standards based on children around the

world (Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the United States) who are raised in healthy

environments, whose mothers do not smoke, and who are fed with recommended feeding practices.

These new standards were used in the third National Family Health Survey.

12 Standard deviation

21

source: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/india statistics.html

Over 70 to 80% of the calories consumed by the children (even though inadequate)

are derived from cereals and pulses. This results in two things: (i) Children cannot

consume more cereals to make up for the calorie deficiency because of its sheer

monotony and lack of energy density, (ii) In the absence of fats, milk, eggs, and

sources of iron, children starve themselves nutritionally. The resultant iron deficiency

anaemia (IDA) further worsens their appetite. Therefore in the absence of foods other

than cereals and pulses in the diets of children and the inability of children in the age

group 1-18 years to derive and satisfy their protein-calorie and other nutrient needs,

the malnutrition scenario can only get worse. Even fats that provide energy density in

the diets are not available in adequate quantities (normally fats should provide 3040% of calorie needs). It is therefore not surprising that there is massive hunger

leading to multiple nutrient deficiencies. This is not hidden hunger; it is hunger for

nutrient rich foods (Planning Commission 2008).

The main reason that explains a higher child malnutrition rate in India (for that matter

in the entire South Asia) than in poorer, conflict-plagued Sub-Saharan Africa is that

Indian women’s nutrition, feeding and caring practices for young children are

inadequate. This is related to their status in society, early marriage, low weight at

pregnancy and their lower level of education. The percentage of infants with low birth

weight in 2006 was as high as 30. Underweight women produce low birth-weight

babies which become further vulnerable to malnutrition because of low dietary intake,

lack of appropriate care, poor hygiene, poor access to medical facilities, and

inequitable distribution of food within the household.

Estimates based on available data from institutional deliveries and smaller

community-based studies suggest that even now nearly one-third of all Indian infants

weigh less than 2.5 kg at birth. Studies (Ramachandran 2007) have shown that LBW

children have a low trajectory for growth in infancy and childhood.

Indian mothers on average put on barely 5 kg of weight during pregnancy. This is a

fundamental reason underlying the LBW problem. They should put on at least 10 kg

of weight, which is the average for a typical African woman (Planning Commission

2008). Middle class Indian women tend to put on well over 10 kg weight during

pregnancy. But this is not the only problem; LBW is also partly explained by low

BMI of women in general, prior to their becoming pregnant. Small women (who are

small before they become pregnant) give birth to small babies.

Even worse is the story about the number of anaemic children, whose percentage

during 1998-2006 has gone up from 74 per cent to 79 per cent.

Table 13: Levels of anaemia among Indian children (as percentage of the total)

Children

aged 635

months

who are

anaemic

NFHS-3 (2005-06)

NFHS-2 (1998-99)

All

India

Urban

Rural

Rural

Urban

Ratio

All

India

Urban

Rural

Rural

Urban

Ratio

74

71

75

fl

79

73

81

TT

(Kumar 2007)

22

When one looks at the Indian states, unlike calorie consumption which is only weakly

correlated with poverty, child malnutrition has a strong correlation with poverty (see

Table 9), with poorer states such as Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand showing a

high degree of malnutrition, whereas better-off states such as Punjab, Haryana, Tami

Nadu and Kerala show comparatively better performance on this indicator.

Determinants of Indian children’s malnourishment can be broadly divided into two

categories. In the first list are factors such as the irrational traditional practices that

still continue, not immediately starting breast feeding after birth, not exclusively

breastfeeding for the first five months, irregular and insufficient complementary

feeding after between 6 months to two years of age, and lack of disposal of child s

excreta because of the practice of open defecation in or close to the house itself

NFHS-3 data shows that 21 per cent of mothers dispose of their children s stoo

safely. There is wide variation between urban and rural households. Whereas 47.2 per

cent urban mothers did so, this proportion was only 11.4 for rural mothers. Clearly the

government’s communication efforts in changing age old practices are not working

well and

and critical

critical public

public health

health messages

messages are simply not reaching the families with

well,

children.

In the second category are factors relating to poor supply of government services,

such as immunisation, access to medical care, and lack of Pnon^

to

primary health care in government programmes. Table 14, based on NFHS-o results,

gives data on both, child rearing practices and government delivery.

Table 14: Access to and Reach of Basic Health Services for children 2005-06

-------------------------- -

Urban Rural

Total

Children under three years breastfed within one hour of birth

IT

29

22

Children aged 0-five months exclusively breastfed

46

40

48

Children aged six to nine months receiving solid or semi-solid

food and breastmilk

Children aged 12-23 months fully immunised (BCG, measles

and three doses each of polio/DPT)

Children aged 12-35 months who received a vitamin A dose m

last six months

Children with diarrhoea in the last 2 weeks who received ORS

56

62

54

44

58

39

21

23

20

26

33

24

Children with diarrhoea in the last 2 weeks taken to a health

58

65

56

51

74

43

22

35

18

facility

Mothers who had at least three antenatal care visits for their last

birth

Mothers who consumed IF A (a vitamin A supplement tablet) for

90 days or more when they were pregnant with their last child

(Kumar 2007)

13 This however is changing with the introduction of NRHM (National Rural Health Mission) in

.

Early evaluation results show optimistic progress in institutional delivery, new household toilets, and

creation of infrastructure for primary health care.

23

Despite the importance of breastfeeding and appropriate feeding for preventing

malnutrition, only 23 per cent of children under three years were breastfed within one

hour of birth and less than half the babies (46 per cent) aged 0-5 months were

exclusively breastfed. Equally striking is the low proportion of children of 6-9 months

-56 per cent - who received solid or semi-solid food and breast milk. It is well

known that frequent illnesses during early childhood and failing to treat them properly

seriously affects the nutritional well-being of children. With only one exception,

namely, children aged 0-5 months being exclusively breastfed, all other indicators

reveal lower reach and access to health services and care in rural areas compared to

urban areas. And this partially explains the higher levels of under-nourishment in

rural compared to urban areas. Also affecting the health and nutritional well-being of

children is the status of women’s health and their access to maternal care services.

Inter-state differences: By and large, in the four states with the lowest proportion of

underweight children — Punjab, Kerala, Jammu and Kashmir and Tamil Nadu —

provisioning of health services, the care of children especially newborns and the

nutritional status of women are better than in the four high malnutrition states of

Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh.

For instance, the proportion of fully immunised children varied between 60 and 81 per

cent in the low malnutrition states and between 33 and 49 per cent in the high

malnutrition states. In the low malnutrition states, between 73 and 97 per cent of

mothers received at least three antenatal care visits; this proportion varied between 17

and 55 per cent in the high malnutrition states. And whereas 14-24 per cent of women

in the low malnutrition states have a BMI below normal, the proportion varied from

40-43 per cent in the high malnutrition states. There are, however, some exceptions

that need more careful examination. Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand seem to be doing

much better in their efforts to promote exclusive breastfeeding in the initial years of a

child’s life. 82 per cent of children aged 0-5 months in Chhattisgarh and 58 per cent m

Jharkhand are exclusively breastfed whereas in the low malnutrition states, the highest

proportion is 56 per cent in Kerala. Also, it is disturbing to find that Gujarat ranks

among the top five states reporting the highest proportion of underweight children - a

phenomenon that needs a closer examination.

The proportion of fully immunised children during 1998-99 to 2005-06 has declined,

in eight states - Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala,

Maharashtra, Punjab and Tamil Nadu - these are generally regarded as more

prosperous than other states. On the other hand, immunisation coverage rates have

shown a significant improvement in West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

On the whole, children’s access to certain critical components of treatment of

childhood diseases has declined over the past seven years. For instance, the proportion

of children with diarrhoea who received ORS in the two weeks preceding the survey

had risen from 18 per cent in 1992-93 to 27 per cent in 1998-99; but since then it has

fallen to 26 per cent in 2005-06.

The contrast between India and China14 is also of some interest in this context. There

is evidence of a steady growth in the heights of Chinese children in recent decades,

not only during the period of fast economic growth that followed the “economic

reforms” of the late 1970s, but also before that. For instance in a representative

sample of Chinese children aged 2-5 years, the average increase in height between

14 This para is based on Deaton and Dreze 2008

24

1992 and 2002 was 3 cm in rural areas (for both boys and girls), and even higher in

urban areas (3.6 cm and 3.8 cm for boys and girls, respectively). According to an

earlier study, the average heights of Chinese children between the ages of 7 and 14

years increased by approximately 8.04 cm between 1951-8 and 1979. NNMB data

suggests much slower growth rates for the heights of Indian children. The increase in

children’s heights between 1975-9 and 2004-5 was a little below 2 cm per decade at

age 3, and barely 1 cm per decade at age 5. The NNMB data also suggests that the

growth rates of heights and weights were particularly slow in the later part of this

period, with, for instance, very little growth in the heights of children at age 5

between 1996-7 and 2004-5.

3.6

Women 9s malnutrition15

According to NFHS-3, while more than one-third of women suffer from CED during

2005-06, over half the women in the age group of 15-49 years suffer from iron

deficiency anaemia. The incidence of anaemia among pregnant women is even higher,

nearly 59 per cent.

The implications of women’s malnutrition for human development are multiple and

cumulative. Women’s malnutrition tends to increase the risk of maternal mortality.

Maternal short stature and iron deficiency anaemia, which increase the risk of death of

the mother at delivery, account for at least 20 per cent of maternal mortality.

Additionally, maternal malnutrition impinges significantly on such important but

interconnected aspects as intrauterine growth retardation, child malnutrition and the

rising emergence of chronic diseases, among others.

Why has malnutrition been so high among women in India? The reasons are multiple

and complex. Apparently, the discriminatory practices associated with the rigid social

norms and the excessive demands made on the time and energies of women join

hands with the usual determinants in blighting women’s nutrition. However, one ot

the usual determinants, namely poverty, seems equally important: not only is poverty

one of the basic causes of malnutrition, but also malnutrition is considered to be both

an outcome and a manifestation of poverty.

Table 15 gives the data for women’s nutrition for various social and economic groups,

suggesting huge socio-economic disparities.

Thus nearly 47 and 68 per cent of women aged 15-49 years from the scheduled tribes

suffer from CED and anaemia, respectively. What is more, more than one-third of

them suffer from the double burden of CED and anaemia together. The incidence o

malnutrition declines with the so-called rise in social status. By extension, such

decline also means huge disparities between social groups: more than 15 percentage

points difference exists between women from ST and others. Thus, the proportion of

women suffering from CED and anaemia together among ST comes closer to double

the proportion of the same among advantaged social groups. More than 50 and 64 per

cent of women from the poorest quintile suffer from CED and anaemia, respectively.

Also, about one-third of them suffer from the double disadvantage of CED and

anaemia As we have observed among social groups, malnutrition among women goes

down drastically with a rise in the household wealth status, creating an equally large

disparity between the wealth groups. The proportion of the poorest women suffering

15 This section is based on Jose and Navaneetham 2008.

25

from CED and anaemia together comes around to more than three times that found in

the highest quintile.

Table 15: Women’s nutrition for social and economic groups (in percentage)

CED

CED and Anaemia

Anaemia

Both

Either I

Neither

Social groups

ST

46.6

68.5

33.5

47.8

18.7

SC

41.1

583”

ITT

47.7

262

OBC16

35.7

54.4

203

48.3

30.9

Others

292

ITT

163

462

362

ST/others

T60

134

129

T03

TTT

Lowest

51.5

64.3

34.0

47.5

18.5

Second

46J

603“

ITT

48.3“

227

Middle

383

To

22.9

48.2

282

Fourth

282

522’

16.4

482’

35.4

Highest

182

46T

“94

45.5

Lowest/highest

233

“139

“T62

1.04

ITT

th

Wealth groups

It is also important to add here that the proportion of women suffering from anaemia

is not low even within the richest quintile. This suggests that a substantially large

proportion of women in India, irrespective of the household wealth status, suffer from

iron deficiency anaemia. The huge disparity in women’s malnutrition between

economic and social groups in India is a matter of serious concern, as the levels ot

nutritional attainment appear to be not only unequal but also unjust.

Further analysis would suggest that though economic and social disparities matter

significantly and independently, the former seems to matter more, at least as tar as

women’s malnutrition is concerned, than the latter. Eastern states, mainly Bihar,

Jharkhand, Orissa and West Bengal, emerge as the repository of womens

malnutrition in India. Though these four states account for 22 per cent of women

considered for the analysis, 30 per cent of women suffering from CED and anaemia

together live in these states.

How does one change the situation? Ensuring equity in women’s rights to land,

property, capital assets, wages and livelihood opportunities would undoubtedly

impact positively on the issue, but underlying the deep inequity m woman s access to