8861.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

(Reference iMalerutfs -1

SEX SELECTION IN INDIA: ISSUES AND APPROACHES

^^Smiuftabk

5fwos India ^gionaCOffice, (Bangalore

IT1*

February, 2005

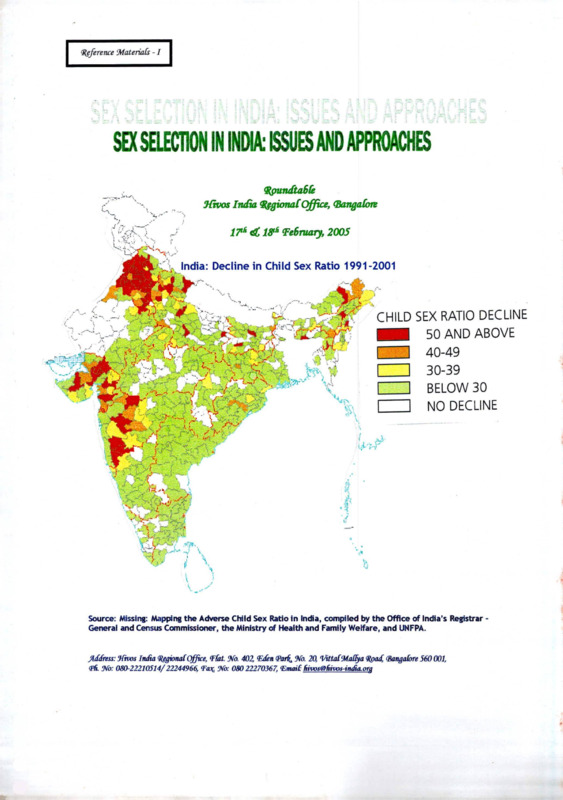

India: Decline in Child Sex Ratio 1991-2001

"“vj

*

ws\

CHILD SEX RATIO DECLINE

|

| 50 AND ABOVE

I ~~| 40-49

I

I 30-39

I

I BELOW 30

I

I NO DECLINE

4

I

Source: Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India, compiled by the Office of India’s Registrar General and Census Commissioner, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and UNFPA.

Jkfdress: Jfivos India RegionalOffice, (Flat. No. 402, (Eden (par^ No. 20, VittaliMalfya Road (Bangalore 560 001,

(Pfi No: 080-22210514/22244966, <Fa^ No: 080 22270367, Email lnvos@Iwws-iiuRa.org

u

(Rgference Materials -1

u

c

SEX SELECTION IN INDIA: ISSUES AND APPROACHES

Utivos India ^gionalOffice, (Bangafoit

L

18^ ‘February, 2005

India: Decline in Child Sex Ratio 1991-2001

<_

<-

I

I

Source: Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India, compiled by the Office of India's Registrar General and Census Commissioner, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and UNFPA.

address: JCtvos India Q^^ionalOffice, (Flat. No. 402, (Edm <Par^ Na 20, VittafMal^a ^pad^ (Bangalore 560 001,

<Pfi No: 080-22210514/22244966 Ta^ No: 080 22270567, (Email: fdvosSkivos-in£a.org

(

Background Note for

the Roundtable

Roundtable on Sex Selection in India: Issues and Approaches

Hivos India Regional Office

17th- 18th February, 2005

Bangalore

Introduction

Hivos (Humanist Institute for Cooperation with Developing Countries) supports many

institutions in the voluntary sector in India which have been addressing issues of

women’s equality in their communities. Hivos’ work in the country is determined by its

partners’ priorities and shared commitments. The Hivos India Regional Office in

collaboration with its partners, its activist friends and fellow development specialists felt it

would be useful to invite representatives of its partner and non-partner organizations,

members of the medical and legal fraternities, media representatives, and members of

the Government to deliberate on the deteriorating situation of women in the country with

special focus on the cluster of issues centered around sex selection in India. Various

factors that have a bearing on the issue have been discussed - patriarchy, son

preference, attitudes and beliefs that discriminate against girl children, population

policies, medical ethics, violence against women and legal reforms. The practice of

elimination of girl children must be stopped and this is possible only through a

convergence of social action and social commitment that brings together different actors

and institutions with their own responsibilities and expertise. How can we carry forward

in social and political practice a history of serious actions that will lead to fundamental

changes in the present social systems of increasing gender inequality and the practice of

sex selection?

In this meeting we hope to draw on the wisdom of earlier meetings to map the contours

of the challenges as they stand now, to pinpoint the similarities and the differences in

approaches and to sharpen the dialogue on future strategies which will put an end to this

state of affairs.

The Process

In 1992 this office of Hivos held a national meeting on the position of women in India in

association with the Centre for Women’s Development Studies. That was the beginning

of focused efforts to work with partner organisations that were committed to the

establishment and realization of women’s rights. We have learnt a great deal from

CWDS and from our partners’ stands on issues pertaining to women’s equality and

position in social life. This meeting is a result of the several dialogues we have held with

different organizations and individuals. In many ways this meeting is being convened by

all the members present! As a preparation for this meeting, Dr. Sabu George from

CWDS was kind enough to agree to draft a report which can be widely disseminated to

partner and other community organizations after this meeting.

1

Many participants have forwarded useful material; a selection of these documents will be

put together in a reference materials folder for all participants. Key articles and press

write-ups will be circulated to our partner organisations. Based on discussions at the

roundtable, Hivos intends to bring out a final report.

Issues

It is clear from anecdotal evidence, testimonies of women and press reports that there is

concern about the growing climate of discrimination against women in India and about

the specific collusion between parties which culminates in the commission of atrocities

against women and girl children. Both these aspects have to be addressed - the

environment that condones collusion and the act of collusion itself. Regarding the first,

one is compelled to question whether the women’s movement has been proactive

enough about safeguarding the interests of the girl child. The issue of the girl child came

into prominence in the eighties, not before that. In the years since then, though there

have been ongoing attempts to raise awareness in different spheres of society, the

situation prevailing today demonstrates that the issue has not been internalized

adequately by all concerned - perhaps even in the women’s movement. Similarly, the

child rights lobby has not seriously looked at gender in childhood. Women’s

organizations have expressed a need for stronger advocacy for the girl child by all

actors.

The present sex ratio imbalance could not have happened without the highly unfortunate

relationships of convenience and connivance that have developed between medical

professionals and those seeking their services. Despite existing safeguards in the

legislation against misuse of medical technology, the problem of sex selection persists in

an environment of traditional-patriarchal values, just as do child marriage and dowry.

This environment makes the issue of redressal and social change a highly complex and

several leveled issue. The weakness in the implementation of social legislation is well

known not only in the area of gender but also in areas such as child labor, untouchability

and dalit rights. Again, in order to really make an impact, we must look at both levels the environment that creates the strong demand for sex selection, and the inability of

legal mechanisms to regulate the actors who cater to that demand with a ready supply of

technology and services. Intervention strategies should address both demand and

supply, but how to sequence or synchronize? Both are essential; perhaps different

groups with different approaches are needed, but focusing on the basic fault line.

While attempting to analyze the efforts made during the past two decades to address the

problem of sex selection, we realize that

■

■

Single issue campaigns leading to highly critical changes in law and society need

to be understood and replicated.

Wider environments of neglect and derogatory attitudes towards women resulting

in the lowering of full citizenship rights need to be explored and understood so

that community-level activists can design campaigns to effect sweeping changes

in health services, health care accessibility, availability of reproductive health

rights information to women and men everywhere, and the premises on which

inequality is built - prejudices that assume the stature of facts and norms in social

life.

2

Poverty, structural processes that result in the disempowerment of people and loss of

their access to and control of resources have been central to Hivos’ financial support.

However, it is clear that the issues being discussed at this roundtable concern

communities who may or may not belong to immiserised populations. Indeed this calls

for differing forms of interventions and efforts at the field level and different kinds of

efforts by social development organizations. The problem is so deep-rooted, spanning

the household and community levels, that it offers multiple long-term challenges to social

development organisations. While the law under Section 23 (2) of the PNDT Act makes

the offence of sex determination a non-cognizable, non-bailable offence, the lax

enforcement machinery robs the law of effectiveness. Purveyors of ultrasound

equipment contribute to the ultimate dispensability of women by making the machines

very easily available. The ‘portability’ of equipment also implies the ‘invisibilisation’ of the

problem itself as far as localities, public policy, and regulatory mechanisms stand. The

problem does not lie with technologies but in the indiscriminate use of them. The culture

of social acceptance of sex selection and the willful practice of eliminating girl children

speak of the wider, growing climate that perpetuates gender inequality. This is of

particular concern given the rapid changes in technology that make regulation and

control difficult. Thousands of institutions and individuals across the country are

complicit in a crime that is tantamount to human rights violations of a kind that is likely to

result in genocide as pointed out by many activists and scholars.

With the view of building a commonality of purpose and a shared sense of reality, the

roundtable will try to foster a dialogue across the diversity of approaches, situations and

interpretation. It is our hope that the specialists gathered at the roundtable will

underscore the immediate and long term consequences of sex selection, and highlight of

the magnitude of the problem as reflected in the 1991 and 2001 censuses. Other

sessions will touch upon the central role of population policies and a “target-driven

population control” agenda particularly when implemented in a patriarchal society. The

two-child norm, and the focus on controlling ‘numbers’ is a feature of all state policies,

accelerating the decline in girl children. Decline in quality and accessibility of

reproductive health care services have also contributed to the state of affairs and the

roundtable will focus on these aspects of social reconstruction of a more equal society.

The responses that have emerged to this range of violatory practices- social

mobilisation, appeals to the judiciary for clear regulatory mechanisms, media campaigns,

debates on ethical choice and the culpability of the medical profession (including

incorporation of ethics in the medical education curriculum) and public policy advocacy

will be of special interest at the roundtable. We hope that this discussion on responses

will yield new insights on a question that is crucial for Hivos as a development institution

and for all civil society actors:

How can broad-based community organizations working on classical issues of class,

caste and gender divides join with the large number of social organizations already

active on several aspects of this growing crisis?

This question needs to be addressed in the context of communities that are in flux, as a

consequence of pervasive social change at multiple levels flowing from the processes of

modernisation, golobalisation and sanskritisation.

3

1

We hope that this dialogue between single-agenda campaign leaders and

representatives of community development organisations that draw on wider social

bases will strengthen future strategies for political and social action.

In Conclusion

With these objectives in mind, we have drawn up a schedule for the roundtable that will

provide time and space for exchange and intervention by all the participants. Differences

of opinions must be understood and overcome so that a few non-negotiables can be

drawn up by everyone. When talking to many of the participants we sensed that

everyone wishes to come to some convergence of perceptions and actions. In this sense

this meeting may be jointly owned, convened and carried forward by all present. We

hope that based on the analysis developed at the roundtable, recommendations for

social action will emerge for everyone to take home.

We look forward to meeting with all of you and we hope that this roundtable will be

useful for activists across the country who are trying to change the world of growing

divides, with special reference to the practice of sex selection. Free market logic, the

logic of technical totalitarianism which ruthlessly promotes the technical fix to deep social

issues, the exploitation of women’s bodies for social ends not necessarily theirs, the

minimalisation of women’s identity in the social mapping of ‘development and progress’,

the loss of historical memory when building the future by collective action, the threat of

several fundamentalisms ...these are issues the women’s movement has been

struggling with. We respect that struggle and we would like to see how the issue of sex

selection can be addressed further from the strength of the history of the women’s

movement. National attention needs to return more seriously (with sustained advocacy)

to the rights of the girl child.

Hivos India Regional Office

7th February, 2005

4

Draft

Programme Schedule

Roundtable on Sex Selection in India: Issues and Approaches

Hivos India Regional Office

17th-18th February 2005

Bangalore

THURSDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2005

09.30 - 09.40

Welcome and Introduction

Jamuna Ramakrishna, Ireen Dubel and Shobha Raghuram

09.40-10.30

Introductions

Participants will speak briefly about their work, gaps between theory and

practice and what they look forward to in the workshop (2 mins each)

Session I:

Historical Overviews

(15 mins presentation followed by 30 mins discussion to be initiated by Respondent)

10.30-11.15

Contextualising Sex Selection: Patriarchy, Position and Situation of

Women

C.P. Sujaya

11.15-12.00

What the Census Data Show

Satish Agnihotri

12.00-12.45

Campaign Efforts and Public Interest Litigation

Sabu George

12.45-01:00

Concluding Remarks by Chair

Chair: Vina Mazumdar

Respondent: Malati Das

01.00-02.00

Lunch

Session II:

Diverse Responses: Campaigns, Social Mobilisation, Legal Reforms

(15 mins presentation followed by 15 mins discussion to be initiated by Respondent)

02.00 - 03.30

Campaigns and Social Mobilisation

CASSA (Representative), Deepa Sinha, Lenin Raghuvanshi

03:30 - 03:45

Concluding Remarks by Chair

Chair: Akhila Sivadas

Respondent: Abha Bhaiya

03.45-04.00

Tea Break

1

04.00-05.00

Legal Reforms

Ossie Fernandes, Kamayani Mahabal

05:00-05:15

Concluding Remarks by Chair

Chair: Sabu George

Respondent: Elizabeth Vallikad

06.45-07.30

Steering Group Meeting

08.00

Dinner buffet at St. Mark’s Hotel

FRIDAY 18 FEBRUARY 2005

9.30 - 09.35

Steering Group Spokesperson- Recap of Highlights (5 mins)

Session III:

A Meeting Place of Diverse Worldviews and Perspectives

(15 mins presentation followed by 15 mins discussion to be initiated by Respondent)

09:35-11:30

Women’s Health

N.B. Sarojini

Campaign on PNDT Act in Gujarat

Trupti Shah

Effects of Two-Child Norm in Maharashtra

Audrey Fernandes

Maternal Health in Karnataka

Poornima Vyasulu

Chair: Shoba Nambissan

Respondent: Donna Fernandes

11:30-11:45

Concluding Remarks by Chair

Public Policy Advocacy

(10 mins presentation followed by 10 mins discussion to be initiated by Respondent)

11.45-12.45

Sex Selection & Pre Birth Elimination of Girl Child

Vibhuti Patel

Civil Society Perspectives

Sanjeev Kulkarni

Role of Media in Shaping Public Policy

Akhila Sivadas

People’s Health Assembly

Thelma Narayan

2

Chair: H. Sudarshan

Respondent: Basavaraj

12.45-01.00

Concluding Remarks by Chair

01.00-02.00

Lunch

Small Group Discussions on Priorities, Strategies, Alliance Building

02.00 - 03.30

Working Groups (11/2 Hrs)

03.30 - 03.45

Coffee/ tea break

03.45-04.15

Presentation of Reports

Chair: keen Dubel

04.15-04.45

Discussion

04.45- 05.00

Concluding remarks by Chair

Concluding Session

05.00-05.30

Open House Feedback Session

Final Comments

Jamuna Ramakrishna, Vina Mazumdar, Shobha Raghuram

Vote of Thanks

Reena Fernandes

3

List of Participants

Roundtable on Sex Selection in India: Issues and Approaches

Hivos India Regional Office

17th-18th February 2005

Bangalore

New Delhi

Ms. Abha Bhaiya

Jagori

C 54, South Extension Part II

Top Floor

New Delhi 110 049

Ph. No. 011 26257140/26264959

Fax. NO. 011 26253629

Email, jagori iaqori@Yahoo.com; bhaiyaabha@Yahoo.com

Dr. Sabu George

CWDS

25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, (Near Gole Market)

New Delhi-110001

Telephone: 011-23345530/ 23365541/ 23366930

Fax: 011-23346044

Email: cwds@cwds.org; cwds@ndb.vsnl.net.in

Dr. R. Gopalakrishnan

Joint Secretary to PM

Prime Minister’s Office

New Delhi 110 011

Ph. No. 011 23015944

Email. rqopalakrishnan@pmo.nic.in

Dr. Vina Mazumdar

Centre for Women’s Development Studies (CWDS)

25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, (Near Gole Market)

New Delhi-110001

Telephone: 011-23345530/ 23365541/ 23366930

Fax: 011-23346044

Email: cwds@cwds.org; cwds@ndb.vsnl.net.in

Dr. N.B. Sarojini

Sama Resource Group for Women and Health

C/o N.B. Sarojini

G-19, 2nd Floor

Marg No. 24, Saket

New Delhi 110 017

Phone: +9111-26562401/55637632

E-mail: samasaro@vsnl.com

1

Dr. Akhila Sivadas

Centre for Advocacy and Research (CFAR)

C-100/B, 1st Floor

Kalkaji

New Delhi 110 019

Phone: 91-11-2629 2787, 2643 0133, 2622 9631

Email: cfarasam@ndf.vsnl.net.in

Dr. C.P. Sujaya

A2, Diwanshree Apartments

30, Ferozeshah Road

New Delhi 110 001

Ph. No. 011 23320353

Email. aniali@del3.vsnl.net.in

Karnataka

Ms. Christy Abraham

ActionAid

139, Richmond Road

Next to Century Park

Bangalore - 560 025

Tel.No.25586682

Fax. No. 25586284

Email: christYa@actionaidindia.orq

Mr. Basavaraju

MGRDSCT

D.No.B/6/18, ’Sharada’

1st Main, KHB Office Road

Rajendra Nagar

Shimoga 577201, Karnataka

Tel: 08182-220867/227441

Email: kcbmqrdsct@yahoo.co.in

Dr. Malati Das

Additional Chief Secretary and

Principal Secretary to Govt

Planning and Statistics Department

Govt, of Karnataka, KGS-2

IV Stage, III Floor, M.S.Building

Dr B R Ambedkar Veedhi

Bangalore 560 001

Ph: 22252352, Internal Ph: 22092726

Fax: 22253694

Email: psrsplq@Yahoo.com; prs-plq@karnataka.qov.in

Ms. Donna Fernandes

Vimochana

No.33, Thyagaraja Layout

Jaibharath Nagar

Maruthi Sevanagar Post

Bangalore 560 033

Ph. No. 25492781

Email: awhrci@vsnl.com;streelekha@vsnl.net;

2

Dr. Sanjeev Kulkami

C/o. Tavargeri Nursing Home Pvt. Ltd

Near Kittur Chenamma Park

Dharwad 580 008

Karnataka

Ph. No. 0836 2448359

Resi. No. 0836 2743100

Email: sankulajeev@Yahoo.com

Dr. Sobha Nambisan

Principal Secretary to Govt. [Higher Education]

M. S. Building, Bangalore

Ph; No. 22252437

Resi. Ph. No. 26689583

Internal Ph: 22092494/22252437

Fax.No. 22253756

E-mail: prshiqh-edu@kamataka.qov.in

Dr. Thelma Narayan

Community Health Cell (CHC)

No. 369, Srinivasa Nilaya

Jakkasandra

1st Block, Koramangala

Bangalore 560 034

Ph. No. 5531518

Email: chc@sochara.org

Mr. Prasanna

People’s Health Movement (PHM)

Communication Officer Community Health Cell (CHC)

No. 369, Srinivasa Nilaya

Jakkasandra

1st Block, Koramangala

Bangalore 560 034

Ph. No. 5531518/51280009

Email: chc@sochara.orq;secretariat@phmovement.orq

Dr. H. Sudarshan

Vigilance Director

Lokayukta - Karnataka

Multistoried Building

Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi

Bangalore 560 001

Ph.No. 22257487

Mobile: 9448277487

Email: hsudarshan@vsnl.net: vgkk@vsnl.com

Karuna Trust

377, 8th Cross

1st Block

Jayanagar

Bangalore 560 011

Ph. No. 26564460

3

Dr. Elizabeth Vallikad

SJNAHS

Dept, of Obstetrics & Gynaecology

St. John's Medical College Hospital

Bangalore

560034, Karnataka

Tel: 080-25530724/ proj.off.22065271

Fax: 25530070

Email: emv2@vsnl.net

Dr. Suchitra Vedanth

State Programme Director

Mahila Samakhya Karnataka

631, 22nd Main, Near Sanjay

Gandhi Hospital, 4th T Block

Jayanagar

Bangalore 560 041

Ph. No. 26634845

Email: samakhya@vsnl.net

Dr Poomima Vyasulu

Centre for Budget Policy Studies (CBPS)

1st Floor, S.V. Complex

(Opp. Basavanagudi Policy Station)

55, K.R. Road

Basavanagudi

Bangalore 560 004

Ph. No. 56907402

Fax. No. 26671230

Ph. No. 9845231797

Email: poomima@cbpsindia.com

Bangalore based Guests

Dr. Saraswathi Ganapathy

Belaku Trust

No. 697, 15th Cross Road

J.P. Nagar llnd Phase

Bangalore 560 078

Ph. No. 26596933/26595594

Email: belaku@vsnl.com

Prof. Gita Sen (Health Watch)

Indian Institute of Management (IIM)

Bannerghatta Raod

Bangalore 560 076

Ph. No. 26582450

Email: qita@IIMB.ERNET.IN

Tamil Nadu

Ossie Fernandes

Human Rights Foundation (HRF)

10, Thomas Nagar, Little Mount, Saidapet

Chennai 600 015

Ph. No. 22353503

Fax. No. 22355905

Email: hrf@md3.vsnl.net.in

4

Mr. Jeeva/P. Pavalam

Campaign Against Sex Selective Abortion (CASSA)

11, Kamala 2nd Street, Chokkikulam

Madurai 625 002

Telefax: 0452 2530486, 0452 2524762

Email: sirdmdu@hotmail.com

Ms. D Sharifa

STEPS Women’s Organisation

Near Union Office

Pudukkottai 622 001

Telephone: 04322-220583

Email: sherifasteps@Yahoo.com

Mobile: 98424-20583

Orissa

Dr. Satish Balaram Agnihotri

Secretary, Department of Women and Child Development

Government of Orissa

Bhubaneswar

Orissa

Ph. No. 0674 2536775 (2928)

Fax. No. 0674 2406756

Email. sbaqnihotri@Yahoo.com; wcdsec@ori.nic.in

Ms. Bishaka Bhanja

C/o. P.C. Bhanja

Ramgarh, Tulsipur

Cuttack 753 008

Orissa

Ph. No. 0671 2361424

Mobile: 9437046508

Email: bhania@sathyam.netin

Andhra Pradesh

Ms. Dipa Sinha

MVF, No.201/202. Narayan Apartments

Sri Hanumanji Co-op. Housing Society

West Marredpally

Secunderabad -500026, A.P.

Tel: 040-27801320/ 27700290

Fax: 040 - 27808808

Email: mvfindia@hotmail.com

Maharashtra

Ms. Flavia Agnes

Majlis Manch

Bldg. No. 4, Block A/2

Golden Valley

Kalina-Kurla Road

Kalina, Mumbai 400 098

Telephone: 022-26661252/ 2666 2394

Fax: 022-26668539

Email: flaviaaqnes@vsnl.net;flaviaaqnes@hotmail.com

5

Dr. Audrey Fernandes

Tathapi Trust

425, Development Plant 77

Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth Colony

Mukund Nagar

Pune 411 037

Ph. No. 020 24275906

Email: tathapi@vsnl.com

Dr. Kamayani Mahabal

CEHAT

Survey No. 2804 & 2805

Aaram Society Road

Vakola, Mumbai 400 055

Tel: (91) (022) 26673571/26673154

Fax: (91) (022) 26673156

Email: cehat@vsnl.com

Prof. Vibhuti Patel (Dr)

Head, P.G. Department of Economics

S.N.D.T. Women's University

New Marine Lines

Mumbai-400020

Email: vibhuti@vsnl.net

Uttar Pradesh

Dr. Lenin Raghuvanshi

Janmitra Nyas

SA 4/2A, Daulatpur

Varanasi 221002

Uttar Pradesh

Ph. No. 0542 586688/586676

Email: pvchr@yahoo.com

Rajasthan

Ms. Jaya Bharti

Astha Sansthan

attn. Dr. Ginny Shrivatsav

39 Kharol Colony

Udaipur, Rajasthan 313 001

Telephone : 0294-2451348 / 2451705

: 0294-2451391

Telefax

: fish trans@rediffmail.com; astha39@sancharnet.in

Email

Gujarat

Dr. Trupti Shah

Sahiyar (Stree Sangathan)

37, Patrakar Colony

Tandalja Road, Post-Akota

Vadodara-390 020

Gujarat, India

Telephone: 0091-265 513482 or 0091-265 334461

Email: sahiyar1@yahoo.co.in;rohit trupti@Yahoo.com

6

Rapporteur

Dr. Vijayalakshmi

Consultant Sociologist

416, Teacher’s Layout

Nagarbhavi First Stage

Nagarbhavi PO

Bangalore 560 072

Ph.No. 23213353

Mobile: 9448373353

Email: viiaYalakshmi@vsnl.com

Hivos Head Office, The Netherlands

Ms. Ireen Dubel

Senior Sector Officer

Gender, Women and Development

Raamweg 16

2596 HL Den Haag

The Netherlands

Ph. No: 00 31 70 3765500

Fax. No: 00 31 70 3624600

Email: i.dubel@hivos.nl

Netherlands

Dr. Sharada Srinivasan

Institute of Social Studies (ISS)

P.O. Box 29776

2502 LT The Hague

The Netherlands

Telephone: +31 70 426 0460/4260504

Fax: +31 70 426 0799

Email: srinivas@iss.nl

Staff of Hivos India Regional Office, Bangalore

For clarifications on logistics contact: Julietta Venkatesh/Hemalatha

For clarifications on financial and administration contact: Salim Vali

7

2.

National Population Policy 2000: A Critique

Jashodhara Dasgupta, KRITI

3.

Re-Examining Critical Issues on National Population Policy 2000

Devaki Jain and Mohan Rao

4.

Female Sex Selective Abortions: Some Issues

Mohan Rao, IDPAD Newsletter Vol. II, No. 1, January-June 2004

5.

The Two-Child Norm only leads to Female Foeticide

Madhu Gurung, www.infochanqeindia.orq/analYsis47print.isp

Role of Medical Establishment - Role of New Reproductive Technologies

1.

Social Justice and the New Human Genetic Technologies

Centre for Genetics and Society

2.

The Basic Science

Centre for Genetics and Society

3.

NGO moves Court over MCl’s failure to check Foeticide

Stop Selective Sex Abortions Stop Female Foeticide

www.datamationfoundation.orq/female/acourt.htm

4.

Sex Test law kills off Ultrasound

Kalpana Jain

Stop Selective Sex Abortions Stop Female Foeticide

www.datamationfoundation.orq/female/acourt.htm

5.

Sex Selection: New Technologies, New Forms of Gender Discrimination

Rajani Bhatia, Rupsa Mallik, Dhamita Das Dasgupta with contributions from

Soniya Munshi and Marcy Damovsky

6.

Sons are Rising, Daughters Setting

Dr. Vibuti Patel, HumanScape, Vol.X, Issue IX September 2003

7.

A Study of Ultrasound Sonography Centres in Maharashtra

Sanjeevanee Mulay and R. Nagarajan

Population Research Centre, Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

8.

Female Foeticide: The Collusion of the Medical Establishment

Lalitha Sridhar, www.infochanqeindia.org/features210print.isp

9.

Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis for Gender Pre-Selection in India: A Counter

Argument to the Article by Malpani and Malpani

Rajiv H Mehta, Source: Reproductive Bio-Medicine Outline, Jan/Feb 2002, Vol.

4, Issue 1

10.

Court orders seizure of Illegal Sex Test Machines

Source: National Catholic Report, 3/8/2002, Vol. 38, lssue.18

ii

S

11.

Reproductive Technologies in India; Confronting Differences

Rupsa Mallik, Sarai Reader 2003: Shaping Technologies

Ethics

1.

Urgent Concerns on Abortion Services - EPW Commentary

Ravi Duggal, Vimala Ramachandran

2.

Negative Choice

Rupsa Mallik

Law - Human Rights

1

Female Feoticide or Crime against Humanity?

Kalpana Kannabiran

2.

Protecting the Rights of Giris

Dr. Erma Manoncourt, Deputy Director, UNICEF-lndia Country Office

3.

Rights of the Giri Child: Covered under Important National and International

Instruments

CASSA

4

Proposed Changes to the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, Rules and

Regulation in the Light of Concern about Sex Selection: A Response from the

Coalition for Maternal-Neonatal Health and Safe Abortion

5.

Treating Infanticide as Homicide is Inhuman

Lalitha Sridhar, www.infochanqeindia.orq/features211 print.js£>

6.

Memorandum to SCW to Relieve the Victims of Female Infanticide who are

Accused Guilty under Sec 302

Implementation of Existing Regulations - Obstacles and Bottlenecks

1.

Memorandum - Child Sex Ratio Vs Implementation of PCPNDT Law in Delhi

2.

Amendments to PNDT Act - Critical Appraisal of PNDT Act and Suggested

Amendments

CASSA

3.

The Role of the State Health Services - Emerging Issues

Dr. Reema Bhatia, University of Delhi

4.

A Merely Legal Approach cannot Root out Female Infanticide

Interview with Salem Collector J. Radhakrishnan

Stop Selective Sex Abortions Stop Female Foeticide

www.datamationfoundation.orq/female/acourt.htm

5.

The Role of Appropriate Authorities in Implementing the Pre-natal Diagnostic

Techniques Act 1994 and Roles (as amended upto 2002/2003) - Position Note

iii

for Discussion from State Level Consultation on the Role of the Appropriate

Authorities in Implementing the PNDT Act 1994 and Rules - 24 September,

2003

6.

Steps to be taken to implement the PNDT Act and Rules in Tamil Nadu from

State Level Consultation on the Role of the Appropriate Authorities in

Implementing the PNDT Act 1994 and Rules - 24th September. 2003

7.

A Critical Analysis of Tamil Nadu Government Cradle Baby Scheme

P. Phavalam, Convenor, CASSA

Campaigns and Interventions

1.

Tackling Female Infanticide: Social Mobilisation in Dharmapuri, 1997-99

Venkatesh Athreya, Sheela Rani Chunkath, Economic and Political Weekly,

December 2, 2000

2.

Indicators

CASSA

3.

Public Interest Litigation Filed in Supreme Court

CASSA

4.

Resolutions of Campaign against Sex Selective Abortion - Resolutions

CASSA

5.

Monitoring the Declining Child Sex Ratio - a Suggested Method

CASSA

6.

Minutes of the Two Days National Consultation on Enforcement of PCPNDT Act

iv

Gender Inequality; Patriarchy - Broad Overviews,

Analysis and History

[

s.rvi.o.U

■AZ'^r's

Sex Selection & Pre Birth Elimination of Girl Child

Dr. Vibhuti Patel, Professor & Head, Department of Economics,

SNDT Women’s University, Churchgate, Mumbai-400020.

E-mail- vibhuti@vsnl.net Phone-91-022-26770227, mobile-9321040048

Presented at A Round Table on Sex Selection

organised by HIVOS, Banglore on 17-18, February, 2005

Abstract

Consumerist Culture oriented economic development, commercialisation of medical

profession and sexist biases in our society, combined together have created a sad scenario of

‘missing girls’. Global comparisons of sex ratios shows that Sex ratios in Europe, North

America, Caribbean, Central Asia, the poorest regions of sub Saharan Africa are favourable

to women as these countries neither kill/ neglect girls nor do they use NRTs for production of

sons. The lowest sex ratio is found in some parts of India.

Deficit of women in India since 1901 -Violence against Women over the Life Cycle, from

womb to tomb- female infanticide, neglect of girl child in terms of health and nutrition, child

marriage and repeated pregnancy taking heavy toll of girls’ lives- Selective Elimination of

Female Foetuses and selection of male at a preconception Stage-Legacy of continuing

declining sex ratio in India in the history of Census of India has taken new turn with

widespread use of new reproductive technologies (NRTs) in India. NRTs are based on

principle of selection of the desirable and rejection of the unwanted. In India, the desirable

is the baby boy and the unwanted is the baby girl. The result is obvious. The Census results of

2001 have revealed that with sex ratio of 927 girls for 1000 boys, India had deficit of 60 lakh

girls in age-group of 0-6 years, when it entered the new millennium- Female infanticide was

practiced among selected communities, while the abuse of NRTs has become a

generalised phenomenon encompassing all communities irrespective of caste, class,

religious, educational and ethnic backgrounds. Demographers, population control lobby,

anthropologists, economists, legal experts, medical fraternity and feminists are divided in

their opinions about gender implications of NRTs. NRTs in the context of patriarchal control

over women’s fertility and commercial interests are posing major threat to women’s dignity

and bodily integrity. The supporters of sex selective abortions put forward the argument of

“Women’s Choice” as if women’s choices are made in social vacuum. In this context, the

crucial question is-

Can we allow Asian girls to become an endangered species?

Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act was enacted in 1994 as a result of pressure created by

Forum Against Sex-determination and Sex —preselection. But it was not implemented. After

another decade of campaigning by women’s rights organisations and public interest litigation

filed by CEHAT, MASUM and Dr. Sabu George, The Pre-natal Diagnostics Techniques

(Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act, 2002 received the assent of the

President of India on 17-1-2003. The Act provides “for the prohibition of sex selection,

before or after conception, and for regulation of pre-natal diagnostic techniques for the

purposes of detecting genetic abnormalities or metabolic disorders or sex-linked disorders

and for the prevention of their misuse for sex determination leading to female foeticide and

for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”. The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques

(Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Rules, 2003 have activated the

implementation machinery to curb nefarious practices contributing for MISSING GIRLS. We

have a great task in front of us i.e. to change the mindset of doctors and clients, to create a

1

socio-cultural milieu that is conducive for girl child’s survival and monitor the activities of

commercial minded techno-docs thriving on sexist prejudices. Then only we will be able to

halt the process of declining sex ratio resulting into deficit of girls/women.

Introduction

Asian countries are undergoing a demographic transition of low death and birth rates in their

populations. The nation-states in S. Asia are vigorously promoting small family norms. India

has adopted two-child norm and China has ruthlessly imposed ‘one child per family rule.

Historically, most Asian countries have had strong son-preference. The South Asian countries

have declining sex ratios. This presentation tries to examine gendered socio-cultural and

demographic implications of new reproductive technologies, with special focus on sex

determination and sex-pre-selection technologies.

Sex Ratios - A Global Scenario

Sex ratios in Europe, North America, Caribbean, Central Asia, the poorest region- sub

Saharan Africa are favourable to women as these countries neither kill/ neglect girls nor do

they use (New Reproductive Technologies) NRTs for production of sons. Only in the South

Asia the sex ratios are adverse for women as the following table reveals. The lowest sex ratio

is found in India.

Table 1- Women per 100 men

Europe & North America

105

Latin America

100

Caribbean

103

Sub Saharan Africa

102

South East Asia

100

Central Asia

104

South Asia

95

China

944

India

L93

Source: The World’s Women- Trends and Statistics, United Nations, NY, 1995

There is an official admission to the fact that “it is increasingly becoming a common practice

across the country to determine the sex of the unborn child or foetus and eliminate it if the

foetus is found to be a female. This practice is referred to as pre-birth elimination of females

(PBEF). PBEF involves two stages: determination of the sex of the foetus and induced

2

termination if the foetus is not of the desired sex. It is believed that one of the significant

contributors to the adverse child sex ratio in India is the practice of female foetuses.”

Historical Legacy of Declining Sex Ratio in India:

In the beginning of the 20th century, the sex ratio in the colonial India was 972 women per

1000 men, it declined by-8, -11, -5 and-5 points in 1911, 1921, 1931 and 1941 respectively.

During 1951 census it improved by +1 point. During 1961, 1971, 1981 and 1991 it declined

by -5, -11, -4, -7 points respectively. Eventhough the overall sex ratio improved by +6

points, decline in the juvenile sex ratio (0-6 age group) is of —18 points which is alarmingly

high.

Table-2

Sex Ratio in India, 1901 to 2001

Decadal Variation

Year

Number of Women per 1000 Men

1901

972

1911

964

-8

1921

955

-11

1931

950

-5

1941

945

-5

1951

946

+1

1961

941

-5

1971

930

-11

1981

934

-4

1991

927

-7

2001

933

_____

+6

Source: Census of India, 2001

Prof. Amartya Kumar Sen, in his world famous article “MISSING WOMEN”, has

statistically proved that during the last century, 100 million women have been missing in

South Asia due to ‘discrimination leading to death’ experienced by them from womb to tomb

in their life cycles.

Dynamics of Missing Women in the contemporary India

Legacy of continuing declining sex ratio in India in the history of Census of India has taken

new turn with widespread use of new reproductive technologies (NRTs) in urban India. NRTs

are based on principle of selection of the desirable and rejection of the unwanted. In India,

the desirable is the baby boy and the unwanted is the baby girl. The result is obvious. The

1 “Missing...Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India”, Office of the Registrar General and Census

Commissioner, India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and United Nations Population Fund, 2003

3

Census results of 2001 have revealed that with sex ratio of 933 women for 1000 men, India

had deficit of 3.5 crore women when it entered the new millennium.

Table-3

Demographic Profile

Population of India_________________

Males____________________________

Females

Deficit of women in 2001____________

Sex ratio (no. of women per 1000 men)

Source: Census of India, 2001.

102.7 crores

53.1 crores

49.6 crores

3.5 crores

933

Political Economy of Missing Girls

The declining juvenile sex ratio is the most distressing factor reflecting low premium

accorded to a girl child in India.2 As per the Census of India, juvenile sex ratios were 971,

945 and 927 for 1981, 1991 and 2001 respectively. In 2001, India had 158 million infants and

children, of which 82 million were males and 76 million were females. There was a deficit of

6 million female infants and girls. This is a result of the widespread use of sex determination

and sex pre-selection tests throughout the country (including in Kerala), along with high rates

of female infanticide in the BIMARU states, rural Tamilnadu and Gujarat. Millions of girls

have been missing in the post independence period. According to UNFPA (2003) 3, 70

districts in 16 states and Union Territories recorded more than a 50point decline in the child

sex ratio in the last decade.

1 To stop the abuse of advanced scientific techniques for selective elimination of female

foetuses through sex -determination, the government of India passed the PNDT Act in 1994.

But the techno-docs based in the metropolis, urban and semi-urban centres and the parents

desirous of begetting only sons have subverted the act.

Sex determination and sex pre-selection, scientific techniques to be utilized only when certain

genetic conditions are anticipated, are used in India and among Indians settled abroad to

eliminate female babies. People of all class, religious, and caste backgrounds use sex

determination and sex pre selection facilities. The media, scientists, medical profession,

government officials, women’s groups and academics have campaigned either for or against

their use for selective elimination of female foetuses/ embryo. Male supremacy, population

control and moneymaking are the concerns of those who support the tests and the survival of

women is the concern of those who oppose the tests. The Forum Against Sex Determination

and Sex Pre Selection had made concerned efforts to fight against the abuse of these

scientific techniques during the 1980s.

Science in Service of Femicide :

Advances in medical science have resulted in sex-determination and sex pre-selection

techniques such as Sonography, fetoscopy, needling, chorion villi biopsy (CVB) and the most

popular, amniocentesis and ultrasound have become household names not only in the urban

India but also in the rural India. Indian metropolis are the major centres for sex determination

(SD) and sex pre-selection (SP) tests with sophisticated laboratories; the techniques of

2 Patel, Vibhuti (2003) “The Girl Child: Health Status in the Post Independence Period”, The National Medical

Journal of India, AIIMS- Delhi, Vol. 16, Supplement 2, pp. 42-45.

3 UNFPA (2003) Missing, New Delhi.

4

amniocentesis and ultrasound are used even in the clinics of small towns and cities of

Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, West

Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan. A justification for this has been aptly put by a team of

doctors of Harkisandas Narottamdas Hospital (a pioneer in this trade) in these words, “...in

developing countries like India, as the parents are encouraged to limit their family to two

offspring, they will have a right to quality in these two as far as can be assured.

Amniocentesis provides help in this direction”4. Here the word ‘quality’ raises a number of

issues that we shall examine in this paper.

At present, ultrasound machines are most widely used for sex determination purposes.

“Doctors motivated in part by multinational marketing muscle and considerable financial

gains are increasingly investing in ultrasound scanners.”5 But for past quarter century,

Amniocentesis, a scientific technique that was supposed to be used mainly to detect certain

genetic conditions, has been very popular in India for detection of sex of a foetus. For that

purpose, 15-20 ml of amniotic fluid is taken from the womb by pricking the foetal membrane

with the help of a special kind of needle. After separating a foetus cell from the amniotic

fluid, a chromosomal analysis is conducted on it. This test helps in detecting several genetic

disorders, such as Down’s Syndrome, neurotube conditions in the foetus, retarded muscular

growth, ‘Rh’ incompatibility, haemophilia, and other physical and mental conditions. The test

is appropriate for women over 40 years because there are higher chances of children with

these conditions being produced by them. A sex determination test is required to identify sex

specific conditions such as haemophilia and retarded muscular growth, which mainly affect

male babies.

?.

Other tests, in particular CVB, and preplanning of the unborn baby’s sex have also been used

for SD and SP tests. Diet control method, centrifugation of sperm, drugs (tablets known as

SELECT), vaginal jelly, ‘Sacred’ beads called RUDRAKSH and recently advertised Gender

Select kit are also used for begetting boys.6

Compared to CVB and pre-selection through centrifugation of sperm, amniocentesis is more

hazardous to women’s health. In addition, while this test can give 95-97% accurate results, in

1% of the cases the test may lead to spontaneous abortions or premature delivery, dislocation

of hips, respiratory complications or needle puncture marks on the baby. 7

Popularity of the test

Amniocentesis became popular in the last twenty-five years though earlier they were

conducted in government hospitals on an experimental basis. Now, this test is conducted

mainly for SD and thereafter for extermination of female foetus through induced abortion

carried out in private clinics, private hospitals, or government hospitals. This perverse use of

4 Patanki, M. H., Banker, D. D. Kulkami, K. V. & Patil, K. P. (1979, March). “Prenatal Sex-prediction by

Amniocentesis- Our Experience of 600 Cases”, Paper presented at the First Asian Congress of Induced Abortion

and Voluntary Sterilization, Bombay.

5 George, Sabu and Ranbir S. Dahiya (1998) “ Female Foeticide in Rural Haryana”, Economic and Political

Weekly, Vol. XXXIII, No.32, August 8-14, pp. 2191- 2198.

6 Kulkami, Sanjeev (1986) “Prenatal SD Tests and Female Foeticide in Bombay City- a Study”, Foundation for

Research in Community Health, 64-A, R.G. Thadani Marg, Worli, Bombay - 400018.

7 Ravindra, R.P. (1986, January) “The Scarcer Half - A Report on Amniocentesis and Other SD Techniques, SP

Techniques and New Reproductive Technologies” Centre for Education and Documentation, Health Feature,

Counter Fact No. 9, Bombay.

5

modem technology is encouraged and boosted by money minded private practitioners who

are out to make Indian women “male-child- producing machines.” As per the most

conservative estimate made by a research team in Bombay, sponsored by the Women s

Centre, based on their survey of six hospitals and clinics; in Bombay alone, 10 women per

day underwent the test in 1982.8 This survey also revealed the hypocrisy of the ‘non-violent,’

‘vegetarian,’ ‘anti-abortion’ management of the city’s reputable Harkisandas Hospital, which

conducted antenatal sex determination tests till the official ban on the test was clamped in

1988 by the Government of Maharashtra. The hospital’s handout declared the test to be

‘humane and beneficial’. The hospital had outpatient facilities, which were so overcrowded

during 1978-1994 that couples desirous of the SD test had to book for the test one month in

advance. As its Jain management did not support abortion, the hospital recommended women

to various other hospitals and clinics for abortion and asked them to bring back the aborted

female foetuses for further ‘research’.

Scenario During the 1980s:

During 1980s, in other countries, the SD tests were very expensive and under strict

government control, while in India the SD test could be done for Rs. 70 to Rs. 500 (about US

S6 to $40). Hence, not only upper class but even working class people could avail themselves

of this facility. A survey of several slums in Bombay showed that many women had

undergone the test and after learning that the foetus was female, had an abortion in the 18th

or 19^ week of pregnancy. Their argument was that it was better to spend Rs. 200 or even

Rs. 800 now than to give birth to a female baby and spend thousands of rupees for her

marriage when she grew up.

The popularity of this test attracted young employees of Larsen and Tubero, a

multinational engineering industry. As a result, medical bills showing the amount spent on

the test were submitted by the employees for their reimbursement by the company. The

welfare department was astonished to find that these employees were treating sex

determination tests so casually. They organized a two-day seminar in which doctors, social

workers, and representatives of women’s organisations as well as the family planning

Association were invited. One doctor who carried on a flourishing business in SD stated in a

seminar that from Cape-Comorin to Kashmir people phoned him at all hours of the day to

find out about the test. Even his six-year-old son had learnt how to ask relevant questions on

the phone such as, “Is the pregnancy 16 weeks old, etc.9

Three sociologists conducted micro-research in Bijnor district of Uttar Pradesh. Intensive

field work in two villages over a period of a year, and an interview survey of 301 recently

delivered women drawn from randomly selected villages in two community developed blocks

adjacent to Bijnor town convinced them of the fact that “Clinical services offering

amniocentesis to inform women of the sex of their foetuses have appeared in North India in

the past 10 years. They fit into cultural patterns in which girls are devalued”.10 According to

s Abraham, Ammu and Shukla, Sonal (1983) "Sex Determination Tests”, Women’s Centre, 104 B, Sunrise

Apartment, Nehru Road, Vakola Santacruz (E), Bombay.

9 Abraham, Ammu (1985, October). “Larsen and Turbo Seminar on Amniocentesis”, Women’s Centre

Newsletter, Bombay, 1 (4), 5-8.

10 Jeffery,Roger and Jeffery,Patricia & Lyon,,Andrew (1984) “Female Infanticide and Amniocentesis’” Social

Science and Medicine, (U.K) 19(11), 1207-1212.

6

the 1981 Census, the sex ratio of Uttar Pradesh and Bijnor district respectively, were 886 and

863 girls per 1000 boys. The researchers also discovered that female infanticide practiced in

Bijnor district until 1900, had been limited to Rajputs and Jats who considered the birth of a

daughter as a loss of prestige. By contrast, the abuse of amniocentesis for the purpose of

female foeticide is now prevalent in all communities.

In Delhi, the All India Institute of Medical Science began conducting a sample survey of

amniocentesis in 1974 to find out about foetal genetic conditions and easily managed to

enroll 11000 pregnant women as volunteers for its research. 11 Main interest of these

volunteers was to know sex of the foetus. Once the results were out, those women who were

told that they were carrying female fetuses, demanded abortion.12 This experience motivated

the health minister to ban SD tests for sex selection in all government run hospitals in 1978.

Since then. Private sector started expanding its tentacles in this field so rapidly that by early

eighties Amniocentesis and other sex selection tests became bread and butter for many

gynaecologists.

A sociological research project in Punjab in 1982 selected, in its sample, 50% men and

50% women as respondents for their questionnaire on the opinions of men and women

regarding SD tests. Among male respondents were businessmen and white-collar employees

of the income group of Rs. 1000/- to Rs. 3500/- per month, while female respondents were

mainly housewives. All of them knew about the test and found it useful.13 Why not? Punjab

was the first to start the commercial use of this test as early as in 1979. It was the

advertisement in the newspaper regarding the New Bhandari Ante-Natal SD Clinics in

Amritsar that first activised the press and women’s groups do denounce the practice.

A committee io examine the issues of sex determination tests and female foeticide, formed

at the initiative of the government of Maharashtra in 1986, appointed Dr. Sanjeev Kulkami of

the Foundation of Research in Community Health to investigate the prevalence of this test in

Bombay. Forty-two gynecologists were interviewed by Dr. Sanjeev Kulkami, who is himself

a gynaecologist. His findings disclosed that about 84% of the gynaecologists interviewed

were performing amniocentesis for SD tests. These 42 doctors were found to perform on-anaverage 270-amniocentesis tests per month. Some of them had been performing the tests for

10-12 years. But the majority of them started doing so only in the last five years. Women

from all classes, but predominantly middle class and lower class of women, opted for the test.

About 29% of the doctors said that up to 10% of the women who came for the test already

had one or more sons. A majority of doctors feel that by providing this service they were

doing humanitarian work. Some doctors feet that the test was an effective measure of

population control. With the draft of the 8th Five-Year Plan, the Government of India aimed

to achieve a Net Reproduction Rate of ond (i.e. the replacement of the mother by only one

daughter). For this objective SD and SP were seen as handy; the logic being a lesser number

of women means less reproduction. 14

11 Mazumdar, Veena (1994), “Amniocentesis and Sex Selection”, Centre for Women’s Development Studies,

Delhi, Occassional Paper Series No. 21.

12Chhachhi, Amrita & Stayamala, C. (1983, November) “Sex-determination Tests: A Technology, Which Will

Eliminate Women”, Medico Friend Circle Bulletin, India; No. 95, 3-5.

13 Singh, Gurmeet and Sunita Jain (1983). “Opinion of Men and Women Regarding Amniocentesis”, College of

Home Science”, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India.

14 Kulkami, 1986, opcit.

7

Controversy Around Amniocentesis and other SD & SP Tests

Twenty years ago a controversy around SD and SP started as a result of several investigative

reports published in popular newspapers and magazines such as India Today, Eve’s Weekly,

Sunday and other national and regional English language journals. One estimate that shocked

many, from academicians to activists, was that between 1987 and 1983, about 78000 female

foetuses were aborted after SD tests as per Times of India editorial in June, 1982. The article

by Achin Vanayak15 in the same paper revealed that almost 100% of 15914 abortions during

1984-85 by a well-known abortion centre in Bombay were undertaken after SD tests.

All private practitioners in the SD tests who used to boast that they were ‘‘doing social work”

by helping miserable women, exposed their hypocrisy when they failed to provide facilities

of amniocentesis to pregnant women during the Bhopal gas tragedy, in spite of repeated

requests by women’s groups and in spite of many reported cases of the birth of the deformed

babies as a result of the gas carnage. Thus it is clear that this scientific technique is in fact not

used for humanitarian purposes, not because of “empathy towards poor Indian women ’ as

has been claimed. Forced sterilization of males during the emergency rule brought politically

disastrous consequences for the Congress Party. As a result in the post emergency period,

there has been a shift in the policy and women became the main target of population control.

SD and SP’s after effects, harmful effects of hormone based contraceptive pills and anti

pregnancy injections and camps for mass IUD insertion and mass sterilization of women with

their unhygienic provisions, are always overlooked by enthusiasts of the Family Planning

Policy. Most population control research is conducted on women without consideration for

the harm caused by such research to the women concerned.16

India has had a tradition of killing female babies (custom of DUDHAPITI) by putting opium

on the mother’s nipple and feeding the baby, by suffocating her in a rug, by placing the

afterbirth over the infant’s face, or simply by ill-treating daughters.17 A survey by India

Today, 15.6.1986, revealed that among the Kallar community in Tamilnadu, mother who

gave birth to baby girls may be forced to kill their infant by feeding them milk from

poisonous oleander berries. This author is convinced that researcher could also find

contemporary cases of female infanticide in parts of western Gujarat, Rajasthan. Uttar

Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab and Madhya Pradesh. In addition, female members of the family

usually receive inferior treatment regarding food, medication and education. When they

grow up, they are further harassed with respect to dowry. Earlier, only among the higher

castes, the bride’s parents had to give dowry to the groom’s family at the time of engagement

and marriage. As higher caste women were not allowed to work outside the family, their

work had no social recognition. The women of the higher castes were seen as a burden. To

compensate the husband for shouldering the burden of his wife, dowry was given by the girl’s

side to the boy’s side. Lower class women always worked in the fields, mines, plantations,

and factories and as artisans. Basic survival needs of the family such as collection of

firewood and water, horticulture and assistance in agricultural & associated activities; were

15 Vanaik, Achin (1986, June 20) “Female Foeticide in India”, Times of India.

16 Mies, Maria (1986 August) “Sexiest and Racist Implications of New Reproductive Technologies *. Paper

presented at XI World Congress of Sociology, 18-22, New Delhi.

17 Clark, Alice (1983) “Limitation of Female Life Chances in Rural Central Gujarat”, The Indian Economic

and Social History7 Review, Delhi 20 (1), 1-25.

18 Kynch, Jocelyn & Sen, Amartya (1983) “Indian Women: Well-being and Survival”, Cambridge Journal of

Economics, 7, 363-380.

8

provided by the women of lower castes and lower classes. Hence women were treated as

productive members among them and there was no custom of dowry among the toiling

masses.

Historically, practice of female infanticide in India was limited among the upper caste groups

due to system of hypergamy (marrige of woman with a man from a social group above hers)

because of the worry as to how to get a suitable match for the upper caste woman?19

Males in the upper class also thought that a daughter would take away the natal family’s

property to her in-laws after her marriage. In a patri-local society with patri-lineage, son

preference is highly pronounced. In the power relations between the brides and grooms

family, the brides side always has to give in and put up with all taunts, humiliations,

indignities, insults and injuries perpetrated by the grooms family. This factor also results into

further devaluation of daughters. The uncontrollable lust of consumerism and

commercialisation of human relations combined with patriarchal power over women have

reduced Indian women to easily dispensable commodities. Dowry is an easy money, ‘get rich

quick’ formula spreading in the society as fast as cancer. By the late eighties, dowry had not

been limited to certain upper castes only but had spread among all communities in India

irrespective of their class, caste and religious backgrounds. Its extreme manifestation was

seen in the increasing state of dowry related murders. The number of dowry deaths was 358

in 1979, 369 in 1980, 466 in 1981, 357 in 1982, 1319 in 1986 and 1418 in 1987 as per the

police records. These were only the registered cases; the unregistered cases were estimated to

be ten times more.

Academicians Plunged in the Debate:

In such circumstances, “Is it not desirable that a woman dies rather than be ill-treated?” asked

many social scientists. In Dharam Kumar’s20 words: “Is it really better to be bom and to be

left to die than be killed as a foetus? Does the birth of lakhs or even millions of unwanted

girls improve the status of women?”

Before answering this question let us first see the demographic profile of Indian women.

There was a continuous decline in the ratio of females to males between 1901 and 1971.

Between 1971 and 1981 there was a slight increase, but the ratio continued to be adverse for

women in 1991 and 2001 Census. The situation is even worse because SD is practiced by all

rich and poor, upper and the lower castes, the highly educated and illiterate - whereas female

infanticide was and is limited to certain warrior castes.21

Many economists and doctors have supported SD and SP by citing the law of supply and

demand. If the supply of women is reduced, it is argued, their demand as well as status will

be enhanced.22 Scarcity of women will increase their value.20 According to this logic, women

will cease to be an easily replaceable commodity. But here the economists forget the socio

cultural milieu in which women have to live. The society that treats women as mere sex and

19 Sudha, S. and S. Irudaya Raja (1998) “Intensifying Masculinity of Sex Ratios in India: New Evidence 19811991 ”, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthpuram.

“° Kumar Dharma (1983, June 11) “Amniocentesis Again”, Economic and Political Weekly, (Bombay).

21 Jeffery Roger and Jeffery Patricia (1983, April) “Female Infanticide and Amniocentesis”, Economical and

Political Weekly, (Bombay).

Sheth, Shirish (1984, September) “Place of Prenatal Sex determination” , Larson and Turbo Seminar, Bombay

23 Bardhan Pranab (1982, Sept 5) “Little girls and Death in India”, Economic and Political Weekly (Bombay).

9

reproduction object will not treat women in more humane way if they are merely scarce in

supply. On the contrary, there will be increased incidences of rapes, abduction and forced

polyandry.

Agents Hired to buy the Brides and Forced Polyandry:

In Madya Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab, among certain communities, the sex ratio

is extremely adverse for women. There, a wife is shared by a group of brothers or sometimes

even by patrilateral parallel cousins.24 Recently, in Gujarat, many disturbing reports of

reintroduction of polyandry (Panchali system- woman being married to five men) have come

to the light. In villages in Mehsana District, the problem of decling number of girls has

created major social crisis as almost all villages have hundreds of boys who are left with no

choice but to buy brides from outside.25

To believe that it is better to kill a female foetus than to give birth to an unwanted female

child is not only short- sighted but also fatalistic. By this logic it is better to kill poor people

or Third World masses rather than to let them suffer in poverty and deprivation. This logic

also presumes that social evils like dowry are God- given and we cannot do anything about it.

Hence, victimise the victims.

Another argument is that in cases where women have one or more daughters they should

be allowed to undergo amniocentesis so that they can plan a ‘balanced family’ by having

sons. Instead of continuing to produce female children in the hope of giving birth to.a male

child, it is better for the family’s and the country’s welfare that they abort the female foetus

and produce a small and balanced family with daughters and sons. This concept of the

‘balanced family’ however, also has a sexiest bias. Would the couples with one or more sons

request amniocentesis to get rid of male foetuses and have a daughter in order to balance their

family? Never! The author would like to clarify the position of feminist groups in India. They

are against SD and SP leading to male or female foeticide.

What price should women pay for a ‘balanced family?’ How many abortions can a woman

bear without jeopardising her health?

Do Women Have A Choice?

Repeatedly it has been stated that women themselves enthusiastically welcome the test of

their free will. “It is a question of women’s own choice.” But are these choices made in a

social vacuum? These women are socially conditioned to accept that unless they produce one

or more male children they have no social worth.26 They can be harassed, taunted, even

deserted by their husbands if they fail to do so. Thus, their ‘choices’ depend on fear of

society. It is true that feminists throughout the world have always demanded the right of

women to control their own fertility, to choose whether or not to have children and to enjoy

facilities for free, legal and safe abortions. But to understand this issue in the Third World

context, we must see it against the background of imperialism and racism, which aims at

control of the ‘coloured population.’ Thus/' It is all too easy for a population control

advocate to heartily endorse women’s rights, at the same time diverting the attention from the

24 Dubey, Leela (1983, Feburary)

(Bombay).

“Misadventure in Amniocentesis”, Economic and Political Weekly,

25 The Times of India, 8-7-2004.

26 Rapp, Rayna (1984 April) “The Ethics of Choice”, Ms. Magazine, USA.

10

real causes of the population problem. Lack of food, economic security, clean drinking water

and safe clinical facilities have led to a situation where a woman has to have 6.2 children to

have at least one surviving male child. These are the roots of the population problem, not

merely desire to have a male child”27.

Economics and Politics of Femicide

There are some who ask, “If family planning is desirable, why not sex-planning?”. The

issue is not so simple. We must situate this problem in the context of commercialism in

medicine and health care systems, racist bias of the population control policy and the

manifestation of patriarchal power.28 Sex choice can be another way of oppressing women.

Under the guise of choice we may indeed exacerbate women’s oppression. The feminists

assert; survival of women is at stake.

Outreach,and popularity of sex pre-selection tests may be even greater than those of sex

determination tests, since the former does not involve ethical issues related to abortion. Even

anti - abortionists would use this method. Dr. Ronald Ericsson, who has a chain of clinics

conducting sex preselection tests in 46 countries in Europe, America, Asia and Latin

America, announced in his hand out that out of 263 couples who approached him for

begetting off-springs, 248 selected boys and 15 selected girls.29 This shows that the

preference for males is not limited to the Third World Countries like India but is virtually

universal. In Erricsson’s method, no abortion or apparent violence is involved. Even so, it

could lead to violent social disaster over the long term. Although scientists and medical

professionals deny all responsibilities for the social consequences of sex selection as well as

the SD tests, the reality shatters the myth of the value neutrality of science and technology.

Hence we need to link science and technology with socio-economic and cultural reality.30

The class, racist and sexiest biases of the ruling elites have crossed all boundaries of human

dignity and decency by making savage use of science. Even in China, after 55 years of

“revolution”, “socialist reconstruction” and the latest, rapid capitalist development SD and SP

tests for femicide have gained ground after the Chinese government’s adoption of the “onechild family” policy.31 Many Chinese couples in rural areas do not agree to the one child

policy but due to state repression they, while sulking, accept it provided the child is male.

This shows how adaptive the system of patriarchy and male supremacy is. It can establish and

strengthen its roots in all kinds of social structures- pre-capitalist, capitalist and even post

capitalist - if not challenged consistently.32

27 Chhachhi & Sathyamla, 1983, opcit.

28 Wichterrich, Christa (1988) “From the Struggle Against ‘Overpopulation’ to the Industrialisation of Human

Production”, Reproductive and Genetic Engineering - journal of International Feminist Analysis, RAGE ,

Vol.l, No. l,pp. 21-30.

29 Patel, Vibhuti (2003) “ Locating the Context of Declining Sex Ratio and New Reproductive Technologies”,

VIKALP- Alternatives. Vikas Adhyayan Kendra, Mumbai.

30 Holmes, Helen Bequart & Hoskins, Betty B. (1984, April) “Pre natal and pre conception sex choice

technologies - a path to Femicide”, Paper presented at the International Interdisciplinary Congress on Women,

the Netherlands.

31 Junhong, Chu (2001) “Prenatal Sex Determination and Sex Selection Abortion in Rural Central China”,

Population and Development Review, Vol. XXVII, No. 2, PP. 259-281.

32 Patel, Vibhuti (1984, September). “Amniocentesis - Misuse of Modem Technology”, Socialist Health

Review, 1(2), 69-71.

11

Action against SD and SP

How can we stop deficit of Indian Women? This question was asked by feminists, sensitive

lawyers, scientists, researchers, doctors and women’s organisations such as Women’s Centre

(Bombay), Saheli (Delhi), Samata (Mysore), Sahiar (Baroda) and Forum Against SD and SP

(FASDSP) - an umbrella organisation of women’s groups, doctors, democratic rights groups,

and the People’s Science Movement. Protest actions by women’s groups in the late 70s got

converted into a consistent campaign at the initiative of FASDSP in the 1980s. Even research

organisations such as Research Centre on Women’s Studies (Mumbai)), Centre for Women’s

Development Studies (Delhi) and Voluntary Health Organisation, Foundation for Research in

Community Health also took a stand against the tests. They questioned the “highly educated”,

“enlightened” scientists, technocrats, doctors and of course, the state who help in propagating

the tests.33 Concerned group in Bangalore, Chandigarh, Delhi, Madras, Calcutta, Baroda and

Bombay have demanded that these tests should be used for limited purpose of identification

of serious genetic conditions in selected government hospitals under strict supervision. After

a lot of pressure, media coverage and negotiation, poster campaigns, exhibitions, picketing in

front of the Harkisandas Hospital in 1986, signature campaigns and public meetings and

panel discussions, television programmes and petitioning; at last the Government of

Maharashtra and the Central Government became activised. In March 1987, the government

of Maharashtra appointed an expert committee to propose comprehensive legal provisions to

restrict sex determination tests for identifying genetic conditions. The committee was

appointed in response to a private bill introduced in the Assembly by a - Member of

Legislative Assembly (MLA) who was persuaded by the Forum. In fact the Forum

approached several MLA’s and Members of the Parliament to put forward such a bill. In

April 1988, the government of Maharashtra introduced, a bill to provide for the regulation of

the use of Medical or Scientific techniques of pre natal diagnosis solely for the purpose of

detecting genetic or metabolic disorders or chromosomal abnormalities or certain congenital

anomalies or sex linked conditions and for the prevention of the misuse of prenatal sex

determination leading to female foeticide and for matters connected therewith or incidental

thereto (L. C. Bill No. VIII of 1988). In June 1988, the Bill was unanimously passed in the

Maharashtra Legislative Assembly and became an Act. The Acts preview was limited only to

SD tests, it did not say anything about the SP techniques. It admitted that medical technology

could be misused by doctors and banning of SD tests had taken away the respectability of the

Act of SD tests. Not only this, but now in the eyes of law both the clients and the

practitioners of the SD tests are culprits. Any advertisement regarding the facilities of the SD

tests is declared illegal by this Act. But the Act had many loopholes.

Two major demands of the Forum that no private practice in SD tests be allowed and in no

case, a woman undergoing the SD test be punished, were not included in the Act. On the

contrary the Act intended to regulate them with the help of an ‘Appropriate Authority’

constituted by two government bureaucrats, one bureaucrat from the medical education

department, one bureaucrat from the Indian Council of Medical Research, one Gynaecologist

and one geneticist and two representatives of Voluntary Organisations, which made a

mockery of ‘peoples participation’. Experiences of all such bodies set by the government

have shown that they merely remain paper bodies and even if they function they are highly

inefficient, corrupt and elitist.

The Medical mafia seemed to be the most favoured group in the act. It, “ has scored the

most in the chapter on Offences and Penalties...last clause of this chapter empowers the

33 Patel, Vibhuti (1987) “Sex Determination and Sex Pre-selection Tests in India- Recent Techniques in

Femicide”, Reproductive and Genetic Engineering RAGE, Vol. II, No. 2, 1989, pp. 111-119.

12

court, if it so desires and after giving reasons, to award less punishment than the minimum

stipulated under the Act. That is, a rich doctor who has misused the techniques for female

foeticide, can with the help of powerful lawyers, persuade the court to award minor

punishment,” said Dr. Amar Jesani in his article in Radical Journal of Health, 1988. The court

shall always assume, unless proved otherwise, that a woman who seeks such aid of prenatal

diagnosis procedures on herself has been compelled to do so by her husband or members of

her family.” 34 In our kind of social milieu, it is not at all difficult to prove that a woman who

has a SD test went for it of her “free will”. The Act made the victim a culprit who could be

imprisoned up to three years. For the woman, her husband and her in-laws, using SD tests

became a “cognisable, non-bailable and non-compoundable” offence! But the doctors, centres

and laboratories were excluded from the above provision. The Act also believed in

victimising the victim. With this act, the medical lobby’s fear that the law would drive SD

tests underground, vanished. They could continue their business above ground. A high

powered committee of experts had been appointed by the Central Government to introduce a

bill applicable through out India to ban SD tests leading to female foeticide.

The Forum accepted that with the help of the law alone, we can’t get rid of female foeticide.

Public education and the women’s right movement are playing a much more effective role in

this regard. Some of the most imaginative programs of the Forum and women’s groups have

been a rally led by daughters on 22.11.86, a children’s fair challenging a sex stereotyping and

degradation of daughters, picketing in front of the clinics conducting the SD tests, promoting

a positive image of daughters through stickers, posters and buttons, for example, ‘daughters

can also be a source of support to parents in their old age,’ ‘eliminate inequality, not women’,

‘Dimolish dowry, not daughters’, ‘make your daughter self sufficient, educate her, let her

take a job, she will no longer be a burden on her parents.’ The Forum also prepared

“Women’s struggle to survive,” a mobile fair that was organised in different suburbs of

Bombay, conveyed this message through its songs, skits, slideshows, video films, exhibitions,

booklets, debates and discussions.

Recent Studies on Socio-Cultural Background of Son Preference and Neglect of

Daughters:

Recent studies have revealed that, in South Asia, we have inherited the cultural legacy of

strong son-preference among all communities, religious groups and citizens of varied socio

economic backgrounds. Patri-locality, patri-lineage and patriarchal attitudes manifest in,

women and girls having subordinate position in the family, discrimination in property rights

and low-paid or unpaid jobs. Women’s work of cooking, cleaning and caring is treated as