8862.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

(Rgference Materials - II

SEXSELECHON IN INDIA: ISSUESAND APPROACHES

^mndiaSle

JGvos ImGa OfegionaCOffice, (Bangalore

17th

!1

s' >

gM

<

18^ <Fe6ruaTy, 2005

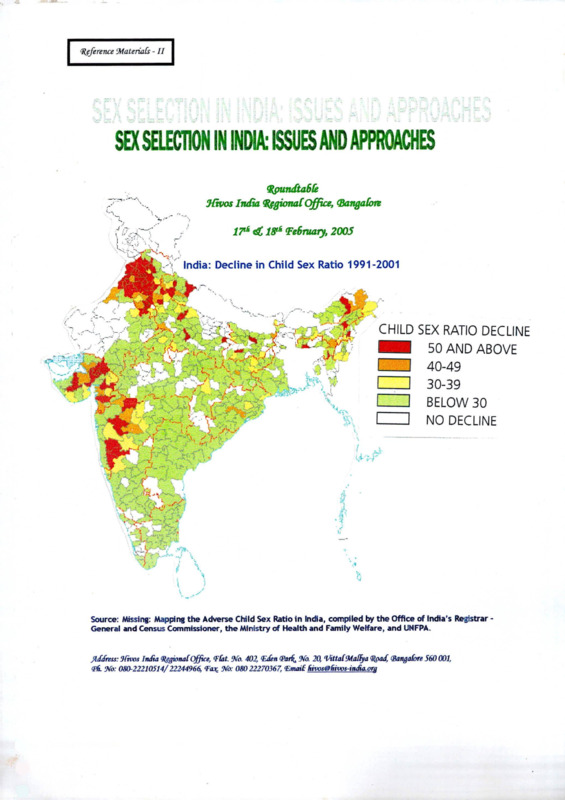

India: Decline in Child Sex Ratio 1991-2001

-

CHILD SEX RATIO DECLINE

50 AND ABOVE

I

I 40-49

f

H 30-39

7

I BELOW 30

___ I NO DECLINE

V

Si

'tW>

*

:

$

Vi

aJ-'

J-?

■f'

if

WTr

w

%

i

Source: Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India, compiled by the Office of India's Registrar General and Census Commissioner, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and UNFPA.

Jid/ress: Ilivos InJia RegionalOffice, I’(at. No. 402, {EJen (Parf^ No. 20, ‘VittalMalfya Q&aJ, (Bangalore 560 001,

<P6 No: 080-22210514/22244966, ¥0* No: 08022270367, ‘Email: 6ivos@liivos-iiuAa.org

^gference Materials - II

SEX SELECTION IN INDIA: ISSUES AND APPROACHES

Q&undtable

Mivos India (RegionalOffice, (Bangalore

IT* <£ 18* February, 2005

India: Decline in Child Sex Ratio 1991-2001

Source: Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India, compiled by the Office of India’s Registrar General and Census Commissioner, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and UNFPA.

^difiTss: Tdvos India (S^jional Office, Tlat. ‘\a 402, <Eden (Par^ Wo. 20, VittalMalfya

<Pii Wo: 080-22210514/22244966,

Wx 08022270367, ‘Email4mw^6ivos-in£a.org

(Bangalore 560 001,

2.

National Population Policy 2000: A Critique

Jashodhara Dasgupta, KRITI

3.

Re-Examining Critical Issues on National Population Policy 2000

Devaki Jain and Mohan Rao

4.

Female Sex Selective Abortions: Some Issues

Mohan Rao, IDPAD Newsletter Vol. II, No. 1, January - June 2004

5.

The Two-Child Norm only leads to Female Foeticide

Madhu Gurung, www.infochanqeindia.orq/analysis47print.isp

Role of Medical Establishment - Role of New Reproductive Technologies

1.

Social Justice and the New Human Genetic Technologies

Centre for Genetics and Society

2.

The Basic Science

Centre for Genetics and Society

3.

NGO moves Court over MCl’s failure to check Foeticide

Stop Selective Sex Abortions Stop Female Foeticide

www.datamationfoundation.orq/female/acourt.htm

4.

Sex Test law kills off Ultrasound

Kalpana Jain

Stop Selective Sex Abortions Stop Female Foeticide

www.datamationfoundation.orq/female/acourt.htm

5.

Sex Selection: New Technologies, New Forms of Gender Discrimination

Rajani Bhatia, Rupsa Mallik, Dhamita Das Dasgupta with contributions from

Soniya Munshi and Marcy Damovsky

6.

Sons are Rising, Daughters Setting

Dr. Vibuti Patel, HumanScape, Vol.X, Issue IX September 2003

7.

A Study of Ultrasound Sonography Centres in Maharashtra

Sanjeevanee Mulay and R. Nagarajan

Population Research Centre, Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

8.

Female Foeticide: The Collusion of the Medical Establishment

Lalitha Sridhar, www.infochanqeindia.orq/features210print.isp

9.

Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis for Gender Pre-Selection in India: A Counter

Argument to the Article by Malpani and Malpani

Rajiv H Mehta, Source: Reproductive Bio-Medicine Outline, Jan/Feb 2002, Vol.

4, Issue 1

10.

Court orders seizure of Illegal Sex Test Machines

Source: National Catholic Report, 3/8/2002, Vol. 38, Issue. 18

ii

11.

Reproductive Technologies in India: Confronting Differences

Rupsa Mallik, Sarai Reader 2003: Shaping Technologies

Ethics

1.

Urgent Concerns on Abortion Services - EPW Commentary

Ravi Duggal, Vimala Ramachandran

2.

Negative Choice

Rupsa Mallik

Law - Human Rights

1

Female Feoticide or Crime against Humanity?

Kalpana Kannabiran

2.

Protecting the Rights of Girls

Dr. Erma Manoncourt, Deputy Director, UNICEF-lndia Country Office

3.

Rights of the Giri Child: Covered under Important National and International

Instruments

CASSA

4

Proposed Changes to the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, Rules and

Regulation in the Light of Concern about Sex Selection: A Response from the

Coalition for Maternal-Neonatal Health and Safe Abortion

5.

Treating Infanticide as Homicide is Inhuman

Lalitha Sridhar, www.infochangeindia.org/features211 print.jsp

6.

Memorandum to SCW to Relieve the Victims of Female Infanticide who are

Accused Guilty under Sec 302

Implementation of Existing Regulations - Obstacles and Bottlenecks

1.

Memorandum - Child Sex Ratio Vs Implementation of PCPNDT Law in Delhi

2.

Amendments to PNDT Act - Critical Appraisal of PNDT Act and Suggested

Amendments

CASSA

3.

The Role of the State Health Services - Emerging Issues

Dr. Reema Bhatia, University of Delhi

4.

A Merely Legal Approach cannot Root out Female Infanticide

Interview with Salem Collector J. Radhakrishnan

Stop Selective Sex Abortions Stop Female Foeticide

www.datamationfoundation.org/female/acourt.htm

5.

The Role of Appropriate Authorities in Implementing the Pre-natal Diagnostic

Technigues Act 1994 and Roles (as amended upto 2002/2003) - Position Note

in

for Discussion from State Level Consultation on the Role of the Appropriate

Authorities in Implementing the PNDT Act 1994 and Rules - 24th September

2003

6.

Steps to be taken to implement the PNDT Act and Rules in Tamil Nadu from

State Level Consultation on the Role of the Appropriate Authorities in

Implementing the PNDT Act 1994 and Rules - 24th September, 2003

7.

A Critical Analysis of Tamil Nadu Government Cradle Baby Scheme

P. Phavalam, Convenor, CASSA

Campaigns and Interventions

1.

Tackling Female Infanticide: Social Mobilisation in Dharmapuri, 1997-99

Venkatesh Athreya, Sheela Rani Chunkath, Economic and Political Weekly,

December 2, 2000

2.

Indicators

CASSA

3.

Public Interest Litigation Filed in Supreme Court

CASSA

4.

Resolutions of Campaign against Sex Selective Abortion - Resolutions

CASSA

5.

Monitoring the Declining Child Sex Ratio - a Suggested Method

CASSA

6.

Minutes of the Two Days National Consultation on Enforcement of PCPNDT Act

iv

1

Role of Medical Establishment - Role of New

Reproductive Technologies

CENTER FOR

GENETICS and SOCIETY

www.genetics-a nil-society.org

Social Justice & the New Human Genetic Technologies

Imagine a world in which well-off people planning to have a baby can buy all sorts of genetic

“enhancements” for their future child-better memory, perfect pitch, straighter nose, longer legs. Ferbhty

clinics craft upscale marketing and advertising campaigns with the message that responsible parents must

do whatever they can to give their child an advantage in a competitive world. Of course, only the wealt y

can access these technologies, and the poor fall further behind. Meanwhile, biotechnology corporations

are busy discovering the genes linked to “desirable” traits and hurry to develop artificial human

chromosomes and “gene cassettes” as well as to patent lucrative pieces of the human genetic code.

Cloning and Beyond: An Active Agenda

Such a world is not only being imagined, but actively promoted by a group of influential scientists

biotech entrepreneurs, bioethicists, and others. Their vision of “consumer eugenics (producing allegedly

superior human beings by means of commercially available reproductive and genetic procedures) is

finding its way into mainstream culture, sometimes accepted and even endorsed by major newspapers,

news magazines, and journals of opinion.

Many people have followed the recent headlines about

human cloning: a bizarre sect claiming to have produced

human clones; the difficulties of passing cloning policy at

the United Nations as well as in the U.S. and other

countries. But few people, including social and political

leaders, are aware of the technical and ideological ties

between cloning and the procedures that, if developed,

would enable a high-tech, free-market eugenics. Some of

these technologies may appear far-off and futuristic, but

they are already being widely used in animals.

uThe final ijoal of reproductive engineering j

appears to be the manu facture of a human

being to suit exact specifications of physical 1

attributes, class, caste, colour and sex.... I he |

powerless in any society will get more

disempowered with the growth of such

reproductive technologies. ”

-Saheli Women’s Resource Centre. India

The prospect of consumer eugenics is particularly threatening for groups that have been historically

targeted or disempowered. The underlying technologies—especially cloning and inheritable genetic

modification” (manipulating the genes of very early embryos, so that the child that develops from it will

have certain characteristics)-are of special concern to women because they are so closely tied to

reproduction and women’s health. Their use would dangerously transform the lives of women and

children, and exacerbate existing trends toward corporate-dominated “reproduction for pro it.

People of color and people with disabilities were targeted by eugenic practices of the twentieth centuty, in

which discoveries in genetics were used to justify scientifically dubious and morally indefensible efforts

The Center for Genetics and Society (www.qenetics-and-society.ora) is a nonprofit information and

public affairs organization working to encourage responsible uses and effective societa 9°^^® of

Where do we draw the line?

Pharmaceuticals

Diagnostics

Somatic

therapies

Creating

clonal

embryos

Creating

human

clones

Preimplantation

selection

Inheritable

genetic

modification

Genetic

castes

Posthuman/subhuman

species

to “improve” the human gene pool. Then, proponents relied on state-sponsored coercive methods such as

involuntary sterilization.

A resurgence of state-sponsored programs of eugenic sterilization (or worse) is, thankfully, unlikely in

most countries. Unfortunately, we do have to take seriously the prospect of a new commercial eugenics,

ideologically motivated by notions of “genes as destiny” and consumer choice, and economically driven

by life sciences corporations that could decide to develop and market species-altering technologies to

those who can afford them. The effects would be similar: the poor and disempowered would be deemed

inferior because of their “less fit” or merely “natural” genes, with all too predictable consequences for

their social, political, and economic well-being.

Responsible Policies for Powerful Technologies

A few applications of human genetic and reproductive

science thus open the door to forms of eugenic

engineering more powerful than any envisioned by the

state-sponsored eugenics movements of the twentieth

century. Many other applications are worthy of

support. There is no reason that we cannot distinguish

between the two, and put in place policies that would

foreclose the profoundly dangerous outcomes while

ensuring universal access to beneficial ones.

“The lessons of history have shown as what

happens when people are ordered as better and

worse, superior and inferior, worthy of life and

not so worthy of life.... H hat can happen when

the technology used in support ofgenetic

thinking is not the crude technology oj shackles

and slave ships, of showers that pour lethal gas ,

and of mass ovens, or even the technology of

surgical sterilization, but the fabulous, fantastic,

extraordinary technology of the new genetics

itself?...My children will not be led to genetic

technology in chains and shackles, or crowded

into cattle cars. It will be offered to them."

The United Nations has taken steps to draft a global

treaty banning reproductive cloning, and many

countries have already passed legislation that prohibits

the production of cloned or genetically modified

-Barbara Katz Rothman, City University of

children. Other countries, including the United States,

New York

have no such lugisiauwu.

legislation. rxnu

And aiuivugn

although uicuy

many people

nave

(_--------------------------------------- — ---- -——— ----are now aware that powerful new reproductive and genetic technologies are looming, there is still little

critical understanding of their political and social implications.

"Humans have long since possessed

the tools for crafting a better world.

Il here love, compassion, altruism

and justice have failed, genetic

manipulation will not succeed.

j

I -Gina Maranto, science writer

I Fortunately, that situation is beginning to change through the

efforts of advocates of women’s and human rights, social justice,

environmental protection and environmental justice, disability

rights, and responsible science. It will be far easier to prevent a

new eugenic future if we act before inheritable genetic

modification and cloning develop further, either as technologies,

as ideologies, or as business interests.

C E\ T ER FOR

GENETICS and SOCIETY

u w w. g e ii c t i c s - a ii d - s o c i e t y . o r g

The Basic Science

Reproductive Cloning

Reproductive cloning means creating a genetic duplicate of an existing organism. A human clone

would be a genetic duplicate of an existing person. Genes are strings of chemicals that help

create the proteins that make up your body. Genes are found in long coiled chains called

chromosomes. They are located in the nuclei of the cells in your body.

CELL NUCtfcUS

W!TH CHKOMOSOMLS

4?- ------- genc

PFOTE-M

SfJC

In sexual reproduction, a child gets half its genes from its mother (in her egg) and half from its

father (in his sperm):

SEXUAL REPRODUCTION

FEMALE

ZYGOTE

Q egg

To

BAPY

EF.13HYO

/'

K.

7

O

Q /

o

o

SPERM

This combination of genes is a fundamental basis for human variation and diversity.

In the case of clonal reproduction, all of the cloned child's genes would come from a body cell of

a single individual:

OR ASEXUAL nLr

-EMAlE

BAH-

: ON

Z’/BRYO

r\_y M’ClEL'S INSEHTED

■> \ »?4.a wsri ‘ rr."

The best known cloning technique, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), is shown abo\ e. The

nucleus from a body cell is put into an egg from which the nucleus has been removed. The

resulting entity is triggered by chemicals or electricity to begin developing into an embryo. If

that embryo were placed into a woman's uterus and brought to term, it would develop into a child

that would be the genetic duplicate of the person from whom the original body cell nucleus was

taken—a clone.

Research Cloning

Research cloning uses somatic cell nuclear transfer to produce a clonal embryo. Sometimes

called "'embryo cloning” or "therapeutic cloning,” it would begin with the same procedure that

would be used for reproductive cloning: the nucleus from a body cell is put into an egg from

which the nucleus has been removed. The resulting entity is triggered by chemicals or electricity

to begin developing into an embryo.

FEMALE

9

NUCLEUS

REMOVED

CLONAL

ZYGOTE

CLONAL

EMBRYO

o

o

■•

NUCLEUS INSERTED

BODY CELL

;SKIN. HA>Fi MUSCLE. ETC. ',

Instead of being implanted in a womb and brought to term as a cloned child, the embryo would

be used for research purposes—for example, to generate embryonic stem cells.

BLASTOCYST

O

0

o

O

HARVESTED

STEM CELLS

EMBRYONIC

STEM CELLS

"Z.OWAL

EMBRYO

NEAVE TISSUES

BONE TISSUES

MUSCLE TISSUES

FOR THERAPEUTIC USES

Most scientists agree that research cloning is not needed as a source of embryonic stem cells for

medical research —these can be obtained from embryos generated by in vitro fertilization.

Rather, researchers have proposed that research cloning may turn out to be useful for producing

‘‘customized” embryonic stem cells that could generate compatible replacement tissues for

individual patients. Replacement tissues generated in this way would presumably not be rejected

by a patient’s immune system, since their genetic make-up would be the same as that of the

patient.

Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD)

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) tests early-stage embryos produced through in vitro

fertilization (IVF) for the presence of a variety of conditions. One cell is extracted from the

embryo in its eight-cell stage and analyzed. Embryos free of the targeted condition can be

implanted in a woman's uterus and allowed to develop into a child.

o

X

o -o

o

o

o

FERTILIZED

EGGS

(ZYGOTES)

O —-s

►

x

o

o

o

TESTED FOR

PRESENCE OF

TARGETED GENES

SELECTED ZYGOTES

IMPLANTED AND

BROUGHT TO TERM

PGD allows couples at risk of passing on a serious genetic condition, such as Tay-Sachs disease,

to have a child that is fully genetically related to them and that does not carry genes for the

disease. It does not involve manipulation of genes in embryos; rather, it selects among embry os.

Because it allows the selection of particular traits in future children, PGD can be considered a

eugenic technology. Disability rights advocates in particular have been critical of its uncontrolled

use. They point out that the definition of “disease” is to some extent subjective, and that people

with disabilities can live full and happy lives. PGD is increasingly being used for less and less

serious conditions, and some US fertility clinics advertise PGD for the selection of a preferred

sex. PGD could also be used in attempts to select a future child’s cosmetic, behavioral, and other

traits.

Inheritable Genetic Modifications

The terms “human genetic modification” or “human genetic engineering” mean changing genes

in a living human cell.

There are two types of genetic modification. Somatic modifications involve adding genes to cells

other than egg or sperm cells. If you had a lung disease caused by a defective gene, scientists

might be able to add a healthy gene to your lung cells and alleviate the disease. The new gene

would not be passed to any children you may have.

Germline modifications (also called “inheritable genetic modifications”) would change genes in

eggs, sperm, or very early embryos. The modified genes would appear not only in any children

that resulted from such procedures, but in all succeeding generations. This application is by far

the more consequential, because it would open the door to the alteration of the human species.

Genes are strings of chemicals that help create the proteins that make up the body. They are

found in long coiled chains called chromosomes located in the nuclei of the cells of the body.

(See image on the first page.)

Genetic modification occurs by inserting genes into living cells. The desired gene is attached to a

viral vector, which has the ability to carry the gene across the cell membrane.

Ox VIRAL VECTOR

\

) CARRYING

' NEW GENE

CELL WITH

ORIGINAL

GENES

VECTOR

INSERTS NEW

GENE INTO CELL

NEW GENE IN THE

CELL ALONG WITH

ORIGINAL GENES

Proposals for inheritable genetic modification in humans combine techniques invoking in vitro

fertilization (IVF), gene transfer, stem cells and cloning:

Proposals for germline

engineering combine

the use of stem cells

and embryo cloning

cf

SPERM

EGG

©

STEM CELLS

© f Q

VIRAL VECTORS

CARRYING

NEW GENES

'

I

STEM CELLS ~

HARVESTED

& CULTURED

•«

COLONIES GROWN

PROM EACH STEM CELL

STEM CELL

WITH new gene

TEST COLONIES

FOR SUCCESSFUL

INCORPORATION

OF NEW GENES

I

NEW

GENETICALLY

ENGINEERED

DESIGNER

BABY

CLONING PROCESS

@

w /I

DS

....

As shown above, germline modification would begin by using IVF to create a single-cell

embryo, or zygote. This embryo would develop for a few days to the blastocyst stage, at which

point embryonic stem cells would be removed. These stem cells would be altered by adding

genes using viral vectors. Colonies of altered stem cells would be grown and tested for

successful incorporation of the new genes. Cloning techniques would be used to transfer a

successfully modified stem cell nucleus into an enucleated egg cell. This “constructed embryo’'

would then be implanted into a woman's uterus and brought to term. The child bom would be a

genetically modified human.

(Images courtesy of the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals)

rage i or

STOP SELECTIVE SEX ABORTIONS

STOP FEMALE FOETICIDE

Home

Appreciation

►

NEW DELHI: Aggrieved by a doctor's alleged admission on a television channel

that foeticide was his - and other doctors' - chief source of income, a women’s organization

has moved the high court against the failure of the Medical Council of India (MCI) to take

deterrent steps in this regard.

Femicide

Lodge Complaint

Laws & Acts

Programs/Projects ►

Articles

What's New

►

Links/Resources

►

Pledge Support

Our Inspiration

Admin

Forum

Search

Medical Ethics

NGO moves court over MCl’S failure to check foeticide

Seeking directions to the MCI to take action against the Mumbaibased doctor,

Mahila Jagran Samiti also wants the apex medical body to amend its code of ethics in view of

the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Act of 1994.

The PNDT Act makes the offence of pre-natal sex determination punishable by

removal of the guilty doctor from the register of the council and, consequently, cancel his/her

licence to practice.

The petitioners' grievance is that despite the fact that the Act was enacted eight

years ago, the MCI is yet to incorporate a provision for canceling the licence to practice.

In 1996, when the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) tabled its annual

report focusing on sex-selective abortions, the MCI had given an undertaking that it would

amend its code of ethics in order to take action against erring doctors. But till date, it has not

done so. Provisions of the Act notwithstanding, Mumbai-based gynaecologist on August 16

last year had openly admitted during a talk show - US Newshour - on PBS Television that he

was a participant in "a widely corrupt system" and that such terminations are his chief source

of income. The programme was on the rampant practice of sex etermination in India.

The petitioner quoted him saying. Unless the government really puls its foot down

and decides to act really tough with the people who are doing this, I don't think there is any

way to curb this procedure."

"It is abundantly clear that although there is a law prohibiting sex determination, the

enforcement machinery works so slowly, or does not work at all, that doctors are confident

that they will not be penalized," the petition said.

Section 23(2) of the Act makes the offence a non-cognizable, nonbailable and noncompoundable punishable with imprisonment for five years and a fine of upto Rs 20,000.

Subsequent offences would attract an imprisonment of five years with a fine of upto Rs

50,000.

Once the doctor is convicted under the Act, the MCI is supposed to remove him/her

from its register, thus canceling his/her licence to practice. But MCI has not amended its code

even eight years after the Act was passed.

Back

Article in Hindi

Developed in National Interest by Datamation Consultants Pvt. Ltd. www.datamationindia.com

http://www.datamationfoundation.org/female/acourt.htm

2/19/200-

Page 1 of 2-

Female Foeticide

STOP SELECTIVE SEX ABORTIONS

STOP FEMALE FOETICIDE

Home

Appreciation

Sex test law kills off ultrasound by Kalpana Jain

►

Femicide

Lodge Complaint

Laws & Acts

Programs/Projects ►

Articles

What's New

►

Links/Resources ►

Pledge Support

Our Inspiration

Admin

Forum

Search

Medical Ethics

New Delhi: As the government, under pressure from the Supreme Court, cracks the whip to

implement a law banning sex selection, medical professionals are trying to devise

mechanisms for continuing with the legitimate use of ultrasound.

Ultrasound is used for determining the sex of the foetus, but it is an important diagnostic tool

as well.

The aim of the law, framed in 1994, was to penalize those who assist in the process of female

foeticide by determining, medically, the sex of the foetus. However, eagemess to implement

the law has resulted in checking the use of ultrasound even by those clinics which do not offer

any maternity services.

Recent interpretations of the law have made routine ultrasound scans for a pregnancy almost

impossible. Doctors are having to give reasons such as "history of aspirin" for an ultrasound

scan of a pregnant woman. And patients requiring diagnostic services for a heart, kidney or

another condition requiring an ultrasound, find doctors unwilling to provide the services.

"Until we get a clarification, even cardiologists are prohibited from taking their portable

ultrasound machines out. All free heart checkup camps too have been stopped for the same

reason," says the head of a branch of the Indian Medical Association, K K Aggarwal.

Chairperson of the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques Act advisory committee of the Delhi

government, Dr Sharda Jain, says that not only are doctors being harassed but foeticide

continues just the way it did earlier.

"If a woman comes to me in her third month of pregnancy and I refuse to abort, then she must

be finding a place to get it done, if she does not come back to me again," says Jain. "We have

been telling the government of places where people are sitting with these ultrasound

machines and termination of pregnancy too is taking place, but nothing happens."

Undoubtedly, the issues are complex and the problem of foeticide needs to be addressed at

several levels.

Member of the national monitoring board for the PNDT Act, Mira Shiva, agrees that the

sensitization of people responsible for its implementation in various states has not been

adequate.

However, national convener of the IMA's female foeticide campaign committee Vinay

Aggarwal, who tried to get doctors to be sensitive to the issue, is no longer so enthusiastic. "In

the name of implementation 'inspector raj' has taken over, which has done little else, except

getting ultrasound centers sealed."

Back

Article in Hindi

Developed in National Interest by Datamation Consultants Pvt. Ltd. www.datamationindia.com

httn7/www dAtAmationfniindAtinn nra/fpmnlp/atpQt htm

o/i o/onoz

Sex Selection: New Technologies, New Forms of Gender Discrimination

By Rajani Bhatia, Rupsa Mallik, and Shamita Das Dasgupta, with contributions from Soniya Munshi

and Marcy Darnovsky

October 2003

Introduction

With the advent of reproductive technologies that made it possible to detect the sex of a fetus

developing in a woman's womb came a new method of discrimination against girls and women.

Developed in the 1970s, prenatal_djagno§JicT.technQlQgies_h

mnniocentesis

proved profitable when maWed as a. method of sex selection. Using prenatal diagnosis to detect sex, a

person^ could choose not to have a child based on the sex of the fetus and opt for an abortion.(l)

Availability of these technologies and their promotion as tools for sex selection spread fast, primarily in

South and East Asia. Currently, they are the most commonly practiced method of sex selection around

the world.

Where its use is most .widespread, prenatal diagnosis for sex ^election reveals clear discrimination

against the'gfrl child, leading to severe gender imbalances in the population. In India, tor example, the

2001 census recorded a substantial decline in the child sex ratio from 945 to 927 females per^ 1000

males in just ten years. In urban areas the ratio declined even more dramatically from 9^5 to 903^girls

per 1000 males.(2) In China, the sex ratio at birth since the mid-1980s is only 100 girls per 107-120

boys.(3)

For decades, women's rights groups in these regions and disability rights groups internationally led the

struggle to expose the discriminatory use of these technologies. They sought, and tn many cases

succeeded in

in getting

Getting laws

laws passed

to regulate

regulate their

their use. But, due to poor oversight and implementation,

succeeded,

passed to

rampant misuse continues.

The U.S. Context

Adding to this climate, the powerful fertility industry (4) in the U.S. has recently developed and begun

promoting even newer technologies fonsex .selection. These include sperm sorting and pre-implantation

aenetic diagnosis (PGD), both of which carry the "added^eLofjLQlJ^mri^ abgrtion, a politically

contentious issue in the U.S. Both sperm sorting and PGD increase the likelihood oi_estabhshing a

pregnancy with a developing child of the desired sex. Because they are applied either prior to

conception of an egg by sperm (sperm sorting) or prior to implantation of a fertilized egg into a

women's uterus (PGD), neither process necessarily involves abortion. However, because neither is 10 J

percent accurate, some couples using these methods may still resort to use of PND followed by sex

selective abortion.

' : use of expensive assisted reproductive technologies commonly

Both PGD and sperm sorting require the

used in the fertility industr^ (like in-vitro fertilization or artificial insemination). The overall cost of

■ - For example, in 2001 the average couple using MicroSort, one

sperm sorting and PGD is very -high.

method of sperm sorting promoted in the

f U.S.

T T spent -nearly $10,000. MicroSort costs S3,200 a try and

most attempted it three times.(5)

Sex selection advocates in the U.S. promote the use of these techniques for what they call family

balancing" or "gender variety," a notion that presupposes.families.o.uglitto_haye children of both sexes.

In

In the

the U

U.’’S?

S’" arguments

arguments for

for sex selection seem to rest on the assumption that the only thing problematic

about its use is the elimination of females through sex selective abortions in societies where there is a

strong preference for sons, e.g., India and China. This, they say, is unlikely to happen in the U.S.

In recent months, sex selection ads have appeared in leading newspapers like The New York Times. Ads

in the North American editions of Indian Express and in India Abroad have specifically targeted South

Asians living in this country.(6)

The increased use and acceptance of sex selection in the U.S. would likely legitimize its practice

elsewhere and complicate the effort by rights-focused constituencies to develop societal and legal

mechanisms that can prevent current and future abuses, both here and abroad.

It is urgent that the unethical promotion and growth of an industry for sex selection is discouraged in

the U.S. In particular the high social cost, abuse potential, experimental nature as well as limited

efficacy of these methods need to be exposed. The practices of the profit-seeking fertility industry as a

whole require oversight and regulation (currently seriously lacking in the U.S.), in order to ensure

ethical use of all new reproductive technologies.

Sex Selection and Discrimination

Economic and social pressures to raise.male childrenJmthe U.S^ may be less than in other societies, but

they are not completely'absent. Furthermore, sex selection is by definition not gender neutral. While we

would like to believe that our preference for one sex over another is not influenced by bias, almost all

societiesJiaYe_inlernalized strong prejudices based on sex from which none of us are completely

immune. A decision to have a girl over a boy, or the ‘offer way around, will be based on gender

stereotypes. What if the child does not live up to our "boy" or "girl" expectations? Would the

disappointed parents feel they had not gotten their "money's worth?" What does it mean to think of a

child as a product with a price tag?

Sex Selection and Gender Violence

Son-preference is a^j^rpduct.pfJhe.ubiqujtQU^^i^chaL^giaL^stem. Unfortunately, this favoring

is hardly a harmless idiosyncrasy, as the valuing of male children is generally accompanied by the

contrasting neglect and mistreatment of daughtere’.TIistoricaliy, this degfaHation of girls has been

expressed in various ways," from female infanticide, to denial of nutrition and health care after birth, to

withholding education and empowerment opportunities to girls and women while they are growing up.

With the advancement in reproductive technology, pre-natal diagnostics followed by sex selective

abortion was added to this list of abuses.

Violence against girls and women often takes the form of deprivation and neglect. But, the dynamic ot

domestic violence can also involve control of women’s reproductive capacity. This aspect ot domination

can become part of a batterer's pattern of abuse.

In the South Asian context, giving birth to a son enhances a woman's status within the family, whereas

her inability to produce a male heir may result in humiliation^. contempt, abuse, and abandonment. Men

frequently blame their wives jor not,giving birth to.a male..child,Ja-laws may also openly threaten their

daughters-in-law with dire consequences if they are unable to produce a son.

abusive situations, a

woman may be forced to undergo testsJo identifyThe sex of her unbom^child, and then coerced to abort

if the fetus js female. Women may be beaten and/or divorced for not giving birth to sons. An abusive

spouselnay use the birth of a daughter as a pretext for violence towards his wife, and then be violent

towards the unwanted daughter. Such abuses occur in the U.S. context as well.

Sex Selection is Big Business

Since new techniques of sex selection require the use of assisted reproductive technologies (7) (like in

vitro fertilization and artificial insemination), the fertility industry can use sex selection to expand their

market to fertile couples. Fortune magazine estimates a U.S. market between $200 and $400 million per

year for the sperm sorting method, MicroSort.(8) In spite of their high price tags, invasiveness, and

risks, demand for these methods appears likely to be high. Surveys reveal that 25-35 percent of all

parents or prospective parents in the U.S. would use sex selection if it were available.(9) One fertility

specialist interviewed by the New York Times said he could fund all of his research until the day he died

if he honored the requests he got for sex selection.(10)

American companies are already turning profits on sex selection in South Asia. General Electric (GE),

for example, captured the largest market share for ultrasound scanners in India. GE sold a

disproportionate number of these machines in Northwest India where the female to male child sex ratio

is the lowest.(l 1) Another American company, Gen-Select, recently marketed dubious sex selection kits

in the Times ofIndia^M)

New Reproductive Technologies Used for Sex Selection

Prenatal diagnosis (PND)\ Developed in the 1970s, PND through techniques such as ultrasound

scanning and amniocentesis followed by sex selective abortion remains the most common method of

sex selection practiced around the world for the last three decades.

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD)\ First tested on humans in 1990, PGD has found increasing

use during the last 5 years mainly by infertile couples undergoing in vitro fertilization (FVF) who are at

risk of having babies with certain genetic conditions. After fertilization of a woman's eggs by a man's

sperm takes place in the laboratory, genetic testing is performed on the resulting embryos (fertilized

eggs) to determine sex. Only embryos of the "desired" sex are implanted in the woman.

Disability rights advocates have raised concern about whether and where to draw the line on acceptable

uses of PGD. Screening out embryos of "the wrong sex" underlines how the method is already used

without reflection about its impact.on ho•w.peopje are valued (or devalued) in society. PGD has been

used to screen out embryos carrying a gene indicating an increased likelihood of deafness in future

generations of offspring.(13) Will PGD be used next to screen out undesirable hair and eye color? The

issues of sex selection are strongly related to forms of oppression based not only on gender, but also on

race, ability and class.

Since this method is experimental, it is not known whether the process of removing a cell from the

embryo for genetic testing may resulfin long-term health consequences for the resulting child.(14) For

women, IVF is an intrusive procedure that may have to be repeated a number of limes before a

successful pregnancy is achieved, if at all.(15) Risks include ovarian Hyper-stimulation syndrome, a

potentially life threatening condition, and multiple births.(16) Recent studies also suggest that infants

conceived by IVF have a higher risk of low birth weight and birth defects than those conceived

naturally.(17)

Sperm Sorting'. Since it is the sex chromosomes of a man's sperm that determine the sex of offspring,

sorting female from male bearing sperm is one method of sex selection. This is a pre-conception

method because it is used prior to fertilization of a woman’s egg, which is accomplished either by

artificial insemination or IVF. There are currently two methods to sort sperm, which were originally

developed to breed livestock of a particular sex. Since both are currently under experimentation for

humans, health risks are not fully known. When sperm sorting is used in conjunction with IVF, the

associated risks must again be taken into account.

Sperm sorting techniques remain unreliable. MicroSort, for example, had an average purity’ of 88

percent for female bearing sperm and 66 percent for male bearing sperm in 916 sorts conducted

between June 1994 and April 2000.(18)

Legal Status Regulating Sex Selection in Selected Countries

In the UK, stringent guidelines by the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) regulate

the use of PGD. The HFEA recently held a public consultation to decide whether or not to regulate

sperm sorting.

The Council of Europe's Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine states in Article 14, "The use

of techniques of medically assisted procreation shall not be allowed for the purpose of choosing a future

child's sex except where serious hereditary sex-related disease is to be avoided. (19)

In Canada legislation was introduced in May 2002 to make sex selection a crime if used for purposes

other than to prevent, diagnose or treat a sex linked disorder or defect.(20)

In India, the use of PND, PGD and preconception techniques such as sperm sorting for sex selection

have all been banned by the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Sex Selection/Determination (Prohibition

and Regulation) Act, 2001.

In China, a law was passed in March 2003 to ban PND for sex selection.

In the US, there is currently very little regulation of the fertility industry. The American Society of

Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), a trade association, issues policy recommendations on ethical use of

technologies, but clinics are not required to follow them. The ASRM issued guidelines in 2001 that

considered sperm sorting under certain conditions ethically allowable. Last year the ASRM confirmed

its policy recommendation against the use of PGD for sex selection. In spite of this, some U.S. fertility

clinics, such as the Tyler Medical Clinic in Los Angeles and the Sher Institute for Reproductive

Medicine in Las Vegas, perform and advertise PGD for sex selection.(20)

Rajani Bhatia is Coordinator of the Committee on Women, Population and the Environment

(http://www.cwpe.org). Rupsa Mallik is Program Director - South Asia at Center for Health and Gender

Equity (http://www.genderhealth.org). Other contributors represent Manavi, Inc.

(http://www.manavi.org) and the Center for Genetics and Society (http.//www.genetics-and-

society.org).

Footnotes

1. The authors believe that all women should have the right and access to safe abortion services.

2. Government of India; Census of India, 2001.

3. Banister, J. 'Shortage of Girls in China Today: Causes, Consequences, International Comparisons

and Solutions.’ 2003; presentation at PRB, Washington DC.

4. Dickens, B.M. "Can Sex Selection be Ethically Tolerated?" J Med Ethics’, 2002; 28.335-?6.

Robertson, J.A. "Pre-conception Gender Selection." American Journal of Bioethics, 2001; Vol. 1(1).

5. Wadman, Meredith, "Sex Selection: So You Want a Girl?" Fortune, February 8, 2001.

6. Sachs, Susan, "Clinics' Pitch to Indian Emigres," New York Times, August 15, 2001.

7. IVF - in vitro fertilization and artificial insemination

8. Wadman, Meredith, "Sex Selection: So You Want a Girl?" Fortune, February 8, 2001.

10.Ibl

Kolata, Gina, "Fertility Ethics Authority Approves Sex Selection." New York Times.

September 28,2001.

.

onno

11.

George, S.M. "Sex Selection/Determination in India," Reproductive Health Matters, -00^.

10(19): 190-92

12.

Weiss, Rick, "Screening Embryos for Deafness," The Washington Post, July 14 2003, p^A06

13.

Goldberg, Carey, "Screening of embryos helps avert miscarriages," Boston Globe, 6/1? J?.

14.

IVF success rate is around 25%. (Simoncelli, Tania, "Pre-Implantation Genetic Diagnosis

15.

and Selection," Political Environments #10, forthcoming)

I

16.

"Sex Selection: Choice and Responsibility in Human Reproduction, Human Fertilisation. &

Embryology Authority, http://www.hfea.gov.uk.

17.

Simoncelli, Tania, "Pre-Implantation Genetic Diagnosis and Selection," Political

Environments #10, forthcoming.

Wadman, Meredith, "Sex Selection: So You Want a Girl?” Fortune, February 8, 2001.

18.

Dickens,

B.M. ' Can Sex Selection be Ethically Tolerated?’ J Med Ethics', 2002; 28:335-36.

19.

Ibid.

20.

Zitner, Aaron, "Testing Embryos," Los Angeles Times, July 23, 2002; Marcus, Amy Dockser,

21.

"Embryo Screening Test Gains In Popularity and Controversy," The Wall Street Journal, July 25, 2002.

Date modified: May 18, 2004

i

1

<

f

Article by Dr. Vibhuti Patel,

Humanscape

VOL. X ISSUE IX SEPTEMBER 2003

‘Sons are rising, daughters setting’

Sex selection is a violation of law and unethical. But our patriarchal society continues to turn a blind

eye towards it or offer perverted excuses to justify its existence. Even the medical community has not

protested against the malpractices of its guilty peers

The recent controversy over Brihunmumbai Municipal Corporation filing a case against the Malpani

Infertility Clinic, Colaba, Mumbai, for violating the recently amended Pre-conception and Prenatal

Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex"D¥termination)\Act (PNDT Act), 1994 has once again

brought the issue of the doctor’s participation in endangering lives of girl children into the lime-light.

Rated as India’s top five infertility clinics, if^_^^it^adyjsedJtie42ublia-.om how-to^elect the sex of

their child. Despite the highly reported concerns pi the ..Supreme Court, expressed in a PIL on the

subject for a very long time, the clinic continued to advertise, in defiance of the orders. So far 48 clinics

have been prosecuted for violation of the Act.

The legacy of continuing declining sex ratio in India__has_taken a new turn with the widespread use of

new reproductiveJ^F^Iogies (NRTs)74aljhe/ciiie& and__towns of India’. NRTs are based oh the

principle of selection of the desirable and rejection.of the unwanted (Patelu2002).

In South Asia, we have inherited the cultural legacy of strong son-preference among all communities,

religious groups, and citizens of varied socio-economic backgrounds. This preference is embedded in

patri-locality, patri-lineage, and patriarchy, and its result is discrimination in property rights and lowpaid or unpaid jobs for women. The Census of India for 2001 revealed that with the sex ratio of 933

women for 1,000 men, India had a shortfall of 3.5 crore women when it entered the new millennium.

According to the Chandigarh-based Institute for Development and Communication, during 2002-2003

every ninth household in the state acknowledged sex selective abortion with the help of ante-natal sex

determination tests. Commercial minded techno-docs and laboratory-owners have been usjng new

reproductive technologies for femicide for oyer two and a half decades. Among the educated families,

adoption of the smaTTfarriny“norm means a minimum of one or two sons in the family. The propertied

class do not desire daughters because the son-in-law may demand a share in property. The property

less classes dispose off daughters to avoid dowry harassment (although they do not mind accepting

dowry for their sons). The birth of a son is perceived as an opportunity for upward mobility while the

birth of a daughter is believed to result in downward economic mobility. Though the stronghold of this

ideology was north India, it is increasingly gaining ground all over India.

To stop the abuse of advanced scientific techniques for selective elimination of female foetuses

through sex-determination, the government of India passed the PNDT Act in 1994. But the techno

docs based in the metropolis and urban centres, and parents desirous of begetting only sons have

subverted the act. Avers Prof Ashish Bose (2001) “The unholy alliance between tradition (soncomplex) and technology (ultrasound) is playing havoc with Indian society”. In several states of India,

sex-selective abortions of female foetuses have increased among those who want small families of

one, two, or maximum three children. Communities, which were practising female infanticide, started

using sex-selective abortions. Many doctors have justified female foeticide as a tool to attain net

reproduction rate (NRR) of one i.e. to attain population stabilisation or, that a mother should be

replaced by only one daughter. There is an evident gender bias here too. To attain population

stabilisation, a fertility rate of 2.1 is envisaged. There is evidence to indicate a sex ratio in favour of

males and a prolonged duration of gender differentials in survivorship in the younger ages results in

the masculining of the population sex ratio.

Sex selection is a covert form of violence while female foeticide is an overt form against women, with

the use of tools like amniocentesis, chorion villai biopsy, sonography, ultrasound and imaging

techniques and assisted reproductive technologies (in which infertile couples are helped to produce

sons).

Socio-legal and ethical issues

Supporters of sex-selection tests for selective elimination of girls/female foetuses apply the law of

demand to validate their stand i.e. “reduction in the supply of girls will enhance their status”. Even

some Western scholars like Prof Dickens (2002), writing in the prestigious Journal of Medical Ethics

aver, "Son preference has produced, but might also mitigate, the sex ratio imbalance...If sons wish, as

adults, to have their own sons, they need wives. The dearth of prospective wives will, in perhaps a

sMr, «™. enhance <he soda. .a,ue o<

dominance”. This neo-classical logic of the law off de™nd “

J women without any respect to

social forces where patriarchy controls sexuality, fert~ y,

trary |n fact, shortage of women

her bodily integrity. Hence, the real e experiences speck to the^ontrar^

Qf

in Haryana, Punjab and the B1MARUrifX%hr^

evidence does not support

girls, forced polyandry, gang rape, and oh'^"Prostitu

.

was g72 and nQW as

such arguments. The sex ratio has steadily de

century the amount of dowry demanded

Ser — S^Sincreased^e =

t^.pu.at^ha^ and

Zile XVofXring5S— it has only universalised the s.ogan, so vociferous in

Haryana: “Sons are rising and daughters are setting !

th£y desjre. an argument

Is it then a question of giving women a choice to choose the sex o tn

y

even

given by many doctors to justify; their sex "Xc "

2001 (SeVen P

to accept that ethics have anything to with it Fo mst

Ma|pPnj when asked whether it was (j

years after the government passed the PNDT A ),

providing assisted reproductive services, I ;

ethical to selectively discard female e^ry are w£ hurtjng? unborn girls?”

-^i

asserted, “Where does the question of ethicsi comenn

'

d b the patriarchal system, and its

But what choice are we talking about f°r womei" *h

Alongside are threats of desertion, divorce,

supporters in the family and the society to produce sons? A ong&ae

are not mere threats,

ill-treatment, and even wife murder for sucha^,°mXomen are not taking decisions autonomously. How

but are often carried out. Under such a Ration,

the9question: Can we allow Indian

can there be choice without autonomy The ctwo

those wqho be|jeve that it is better to kill

women to become an endangered sp

fpmale child Their logic is not only short-sighted but

a female foetus than to give birth to. an unwante, aiven and therefore, not rectifiable. It is such

fatalistic. Their logic regards evils hke dowry to be^Go dgive,j and,^

By

)ogjc

thinking that creates advertisement copy I ke

2

xs-o

Needless tQ sayi investing in girls

xxt

Xconfon,

aX;for Oemand and darassmenf

;ex

of .fie

for dowry is indeed encouraging.

Integrity and accountability of the medical profession

The struggle by the socially conscious ^Xen is nw^rdecadls^W.'Vhe first strong movement

technologies which trigger violence agams

. ,

was started in 1984 in Mumbai, and resulted in

against doctors' unethical P^'^GoVin 1989 and then the national legislation through the PNDT

a law against it in Maharashtra and Goa n 1989. and t

dominated by vested interests in

Act in 1994. However, till the government move^d, medical^ouncils dom^ ^y^

the profession did not come forwar

viniatina the integrity of the profession. Even after the

XXSrtTpLS\W=t°.Ze«?“a,rt.d

moves .0 enforce fl. In connivance «llh ph.bfe

D, Sa” George. The Lawyers Cofleclive (Defhf) foogdl “ ^rt of the’e--

court d,reefed all

on 4 May 2001, to activate the state machinery for

imDlementation, and directed all bodies

state governments to take action for e ec tve> a

genetic laboratories, and genetic clinics to

under the PNDT Act, namely, genetic counse hng ce

qervices Thjs directive also triggered off

have registration and superv.sion to contmu^with t

jament amended the law by bringmg

attempts to plug loop-hopes m the 1994

X

ofPthe |aw. They put in place a stnng of

sex selection at a pre-conception stage unde

P

Brihunmumbai Municipal Corporation

checks and balances to ensure that the Act was effective.

Qf gender of foetus as per the

(BMC) has initiated a drive against the unau ^raphy centres are required to register themselves

directive of the ministry of law and jushce_ All sonegrap V

tratjon certjficate and the message that

with the medical officer of their wards. The disp y ^9$^ js mandatory at the centres.

ssx®

— ——

*

Balaji Telefilms because its top-rated television serial showed a young couple checking the sex of their

unborn child. The Commission approached the BMC and a first investigation report (FIR) was lodged

at the police station. After an uproar created by the commission, Balaji Telefilms prepared an

advertisement based on the Commission’s script that conveyed that sex determination tests for

selective abortion of female foetus is a criminal offence.

A study by Dr Sanjeev Kulkarni for the Foundation for Research in Community Health in 1984

indicated that 84 per cent of the gynaecologists in Mumbai admitted that they were performing

amniocentesis. In comparison, a study by Dr Sunita Bandewar for CEHAT found that 64 per cent of the

abortion service-providers were against sex selective abortions and another ten per cent said that they

were also against it but were compelled to do it. Those who were against it were vociferous in their

opinion: “It should be banned.” “It is inhumane and criminal.” “It is against medical ethics and human

rights.” “It amounts to discrimination against women.”

Interestingly, it took two decades of consistent campaigning by the socially conscious and health

activists using awareness and legislations to make some doctors realise that their act was unethical,

discriminatory, and inhuman. One is still not sure whether such doctors are convinced or are just

momentarily abstaining for fear of the law. Whatever it may be, by being party to the violence, the

profession has compromised its integrity. It is disconcerting, however, that not only does a sizeable

section of its members continue indulging in such malpractices, but the medical councils have not

shown any initiative to take to task doctors whose names have been publicised. The medical

profession cannot be let off as it waits for the police and appropriate authorities to chase violators of

the law, while its own legally constituted and empowered councils remain a mute spectator to such

gross violation of medical ethics. Till they put their act together, society will condemn the entire

profession for the misdeeds of some errant members.

References:

Bandewar, Sunita. Abortion services and providers’ perceptions: gender dimensions, Economic and

Political Weekly, Vol. XXXVIII, No. 21, 24 May 2003, pp. 2075-2081.

Banerjee, Piali. The battle against chromosome X, The Times of India, 25 November 2001

Bose, Ashish. Without my daughter-killing fields of the mind, The Times of India, 25 April 2001

Chattopadhyay, Dhinman. Child sex ratio on the decline in Bengal: report, The Times of India. 10

March 2003

Dickens BM, Can sex selection be ethically tolerated? Journal of Medical Ethics, No. 28, 2002. pp.

335-336.

Eapen, Mridul & Kodoth, Praveena. Demystifying the ‘high status’ of women in Kerala: an attempt to

understand the contradictions in social development, Centre for Development Studies, Kerala, 2001

Ganatra BR, Hirve SS, Walealkar S et al, Induced Aborin A Rural Community in Western Maharashtra:

prevalence and patterns, Mimeograph, Pune, 1997

Kannan, Ramya. More babies being abandoned now, The Hindu, 1 April 2002

Patel, Vibhuti. Women’s challenges of the new millennium, Cyan Publications, New Delhi, 2002

Sen, Vikram. 2001 Census of India - report for Kolkata, Director of Census Operations, West Bengal,

2002

Sridhar, Lalitha. (Women’s Feature Service), India: Killing in Cradle, POPULI - The UNFPA magazine,

Vol.28, No.2, September 2001, pp.10-12

Dr Vibhuti Patel is an economist and women’s movement activist. She works as Reader at the

Centre for Women’s Studies, Department of Economics of the University of Mumbai. She is also

Member Secretary of Women’s Development Cell of the University of Mumbai.

Send this page to your friends

Copyright ©Foundation for Humanisation. All Rights Reserved

by Dr Vibhuti Patel

Poster by Tushar V Mantri: ‘She has the right to live: Stop sex selective abortion'

Supporters of sex-selection tests for selective elimination of girls/female foetuses apply the law

of demand to validate their stand i.e. “reduction in the supply of girls will enhance their status”.

Even some Western scholars like Prof Dickens (2002), writing in the prestigious Journal of

Medical Ethics aver, “Son preference has produced, but might also mitigate, the sex ratio

imbalance...If sons wish, as adults, to have their own sons, they need wives. The dearth of

prospective wives will, in perhaps a short time, enhance the social value of daughters.”

84 per cent of the gynaecologists in Mumbai admitted that they were performing amniocentesis

Medical councils dominated by vested interests in the profession did not come forward to

declare doctors indulging in these practices unethical and making accountable those who were

guilty of violating the integrity of the profession. Even after the enactment of the PNDT Act,

they thwarted all moves to enforce it, in connivance with pliable government medical and civil

bureaucrats.

A Study of Ultrasound Sonography Centres in Maharashtra

Sponsored by the

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

Government ofIndia

Sanjeevanee Mulay & R. Nagarajan

Population Research Centre

Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

Pune-411 004

January 2005

Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

Telephone: 020-25650287, 25654288, 25654289

Fax: 020-25652579

Email: gipe@vsnl.com

Website: http://www.gipe.ac.in

Contents

Chapter

Page

No.

Description

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Tables

List ofFigures

List ofAppendices

i

a

m

vi

vi

Chapter 1

Introduction

1

Chapter 2

Ultra Sound Sonography Centres in Maharashtra: Distribution,

Type and Qualification of the Owners and Operators

6

Chapter 3

Child Sex Ratio and Ultra Sound Sonography Centres in

Maharashtra

18

Chapter 4

Findings of the Survey of Ultra Sound Sonography Centres in

Maharashtra

34

Chapter 5

Summary and Recommendations

59

References

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

72

73

74

75

i

Acknowledgements

We take this opportunity to thank all those, who have been helpful in carrying out this

study. Since this study has involved private medical practitioners, who are not obliged to give

information to anyone, we needed great help from the state government officials. We are

grateful to Dr. P. P. Doke, Director of Health Services, Maharashtra, whose appeal to the

doctors made our job easy. We are also thankful to Dr. Ashok Belambe, Deputy Director,

State Family Welfare Bureau, Pune who helped us in getting the information from District

Appropriate Authorities.

The work m Mumbai was a challenge for us. Dr. Surekha Mehta, Special

Officer in the Department of Family Welfare and Maternal and Child Health, Municipal

Corporation of Greater Mumbai greatly helped our staff in getting the information from the 24

ward offices in Mumbai.

We owe a lot to her. Similarly, we are thankful to concerned

officials of all the Municipal Corporations and Appropriate Authorities at district/tehsil level

m the study area for helping us in carrying out the study. We express our gratitude towards Dr.

Gawhane and Dr. Ghanwat (officials of National Integrated Medical Association), who went

out of the way for helping us in identifying the doctors desirous of using the machine.

We are grateful to Ms. Madhu Bala, Director (PNDT), MOHFW for her guidance and

support in carrying out this study. We also thank Shri S. K. Das, Chief Director (PRC),

MOHFW, for his continuous support to carry out this study by us. We also acknowledge the

support extended by Ms. Sushama Rath, MOFHW.

We are grateful to Mrs. Vandana Shivanekar, Mrs. Deepali Yakkundi, and Shri.

Abhijeet Mahabaleshwarkar, for the help they provided in tabulation, computer processing and

typing of the report. We are thankful to Shri A.M. Pisal, Shri R. S. Pol, Shri Chintamani Jog,

Mrs. Priti Bhat, Shri Akram Khan, Shri A.P. Prashik, Shri Shirish Naikare, Miss Rima

Amrapurkar, and Miss Deepali Dixit for their valuable assistance in carrying out the field

visits. Lastly, we thank all the trained and untrained doctors who own the sonography centres

and the doctors who are desirous of using the sonography machine for providing the necessary

data and co-operation in spite of their busy schedule.

January 6, 2005

Pune

Sanjeevanee Mulay

R. Nagarajan

Population Research Centre

ii

List of Tables

fable

No.

Page

No.

Title of die Table

2.1

Number and percent of registered ultra sound sonography centres in

Maharashtra by I lealth Circles as on September 30, 2004.

7

9 9

Number of registered ultra sound clinics/centres in the districts of

Miiliarashtra as on September 30, 2004.

8

2.3

Number and percent of registered ultra sound clinics/centres in the

districts of Maharashtra, under PNDT Act, as on September 30, 2004.

9

2.4

Type of centre, qualification of owner of sonography centre and

qualification of operator of sonography centre in Maharashtra

10

2.5

Type of ultra sound sonography centres in Maharashtra

11

2.6

Qualifications of the owners of the ultra sound sonography centres.

12

2.7

Qualifications of the doctors using the ultra sound sonography

machines in the centres owned by trained (Self Operated) and

untrained (Centres Employing Other Doctors) persons/doctors

14

2.8

Ultra sound sonography centres owned by trained and untrained

persons

16

2.9

Information regarding doctors attached to multiple (>=4) ultra sound

sonography centres

17

3.1

Sex ratio of child population in the age group 0-6, Maharashtra, 2001

19

3.2

The range in child sex ratio in the districts of Maharashtra, 2001

20

3.3

Change in child sex ratio between 1991 and 2001, by districts.

21

3.4

Sex ratio of child population in the Municipal Corporations of

Maharashtra, 2001

23

3.5

The range in sex ratio of child population in the tehsils of

Maharashtra. 2001

23

3.6

Top and bottom 10 tehsils by child sex ratio in Maharashtra (total,

rural and urban), 2001.

25

3.7

The correlation between number of ultra sound sonography (USG)

centres and child sex ratio and decline child sex ratio.

26

Contd...

iii

Table

No.

Title of the Table

Page

No.

3.8

Number of sonography centres for the top & bottom 10 tehsils in child

sex ratio.

28

3.9

Regression analysis of child sex ratio and availability of sonography

centres in Maharashtra.

29

4.1

Classification of centres by district and training status of the owner of

the centre

38

4.2

Classification of ultra sound sonography centres by its functional

status, kind of machine, year of installation of machine and cost of

machine.

39

4.3

Distribution of ultra sound machines by their make.

41

4.4

Approximate cost and year of installation and average cost of the

machine

42

4.5

Classification of centres by system of medicine studied by the owner

43

4.6

Classification of centres by purposes on which data are available

43

4.7

Classification of centres by reason for incomplete data

44

4.8

Classification of centres by number of obstetric sonography tests

earned out during July 2003-2004 by training status of the owner and

trimester (Tl, T2, T3).

46

4.9

Classification of non-obstetric sonography tests earned out during

July 2003-2004 by training status of the owner

46

4.10

Frequency of the operator's visit for centres with untrained owner

47

4.11

Classification of obstetric sonography tests by size and type of

untrained doctors.

49

4.12

Classification of non-obstetric sonography tests done by untrained

doctors by Kpe

50

4.13

Classification of sonography tests by functional status and training

status of the owner

50

4.14

Percent sonograph} testes done by training status of the owner and

trimester

52

Contd...

iv

Table

Title of the Table

No.

Page

No.

4.15

Percent sonographies done in first trimester cross-classified by percent

sonographies done in second trimester

53

4.16

Percent referred by allopathic doctors

55

4.17

Number of own clients by training status of owner

55

4.18

Frequency of supervisory visit by appropriate authority

57

4.19

AYUSH doctors desirous of having the sonography machine

58

List of Figures

Figure

No.

Title of the Figure

Page

No.

3.1

The relationship between child sex ratio (total) and number of

sonography centres in the districts of Maharashtra.

31

3.2

The relationship between child sex ratio (total) and number of

sonography centres per 1000 population in the districts of Maharashtra.

31

3.3

The relationship between decline child sex ratio between 1991 and 2001

and number of sonography centres in the districts of Maharashtra.

32

3.4

The relationship between decline child sex ratio between 1991 and 2001

and number of sonography centres per 1000 population in the districts of

Maharashtra.

32

3.5

The relationship between child sex ratio (2001) in Municipal

Corporations of Maharashtra number sonography centres per 1000

population.

33

List of Appendices

Appendix

No.

Title of the Appendix

Page

No.

3.1

Map showing the distribution of sonography centres (in dots) in

Maharashtra

73

3.2

Data used for analysis in Chapter III

74

3.3

Questionnaire used for the study

75

\i

Chapter I

Introduction

India is predominantly a patriarchal society. The perception that the family line

runs through a male makes men a precious commodity that needs to be protected and

given a special status. The dominance of men is reflected also in our marriage practices.

Dowry is a clear illustration of the same. In many parts of India, the dowries are so

staggeringly high that the parents have to incur their entire savings in getting their

daughters married off. Naturally, the daughters are cursed to an extent that even the birth

of a girl child in a family is sought to be avoided.

The women always have fallen prey to violence like rape, sexual abuse, dowry

harassment, etc. with no mechanism of fighting through effective laws. We are ashamed to

find instances of female infanticide occurring regularly. Female infanticide now in most

places has been replaced by female foeticide and more sadly, female foeticide has made

inroads into areas, where earlier there were no instances of female infanticide. Further, we

find that it has crossed the class-boundaries.

Female foeticide or sex-selective abortion is the elimination of the female foetus in

the womb itself. However, prior to the elimination, the sex of the foetus has to be

determined and it is done by methods like amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling and

now by the most popular technique ultra sound sonography. Ultra sound sonography is the

least expensive test and can be performed around 12th week of pregnancy. After the

determination of the sex of the baby, if it is not desired, couples go for Medical

Termination of Pregnancy.

Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act

In 1978, the government of India issued a directive banning the misuse of

amniocentesis in government hospitals. Thereafter due to the efforts of activists, a law to

prevent sex determination was passed in Maharashtra, known as Maharashtra regulation of

Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1988. Finally after a public debate all over India,

the parliament enacted the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act on September 20,

1994. It provides for the regulation of: (i) Use of pre-natal diagnostic techniques for the

purpose of detecting genetic or metabolic disorders or chromosomal abnormalities or

1

certain congenital malformation or sex-linked disorders; (ii) For the prevention of the

misuse of such techniques for the purpose of pre-natal sex-determination leading to female

foeticide; and (lii) For matters connected there with or incidental thereto. This act came

into force in 1996. Some amendments in the act were suggested later on. The amended

rules have come into effect from February 14, 2003.

Some important provisions of the PNDT Act:

♦ No genetic counselling centre, genetic laboratory, or genetic clinic (including

clinics or laboratories or centres having ultrasound or imaging equipment), unless

registered under the Act, shall conduct, associate with, or help in conducting

activities relating to diagnostic techniques that can be used to assess the sex of a

fetus.

♦ No person, including specialist in the field of infertility, shall conduct or cause to

be conducted or aid in conducting a pre-conception sex-selection technique on a

woman or man or both or on any tissue, conceptus, fluid, or gametes derived from

either or both of them.

♦ No prenatal diagnostic technique shall be used or conducted unless the person

qualified to do so is satisfied that at least one of the following conditions is

fulfilled: (i) the age of the pregnant woman is above 35 years; (ii) the pregnant

woman has undrgone two or more spontaneous abortions; (iii) the pregnant woman

has been exposed to potentially teratogenic agents such as drugs, radiation,

infection, or chemicals; (iv) the pregnant woman has a history of mental

retardation or physical deformities such as spasticity or other genetic desease; and

(v) any other condition as may be specified by the Central Supervisory Board

designated by the Act.

♦ No person conducting prenatal diagnostic procedures shall communicate to the

pregnant woman concerned or her relatives the sex of the fetus by words, signs,or

in any other manner.

Following bodies are appointed for the supervision of enactment of PNDT act

i)

Central Supervisory Board

2

ii)

State Supervisory Board and Union Territory Supervisory Board

hi)

Appropriate Authority and Advisory Committee

The Appropriate Authorities at district/tehsil level are the immediate supervisory

authorities. They have powers in respect of the following matters, namely:

a) summoning of any person who is in possession of any information relating to

violation of the provisions of this Act or the rules made there under;

b) production of any document or material object relating to clause (a);

c) issuing search warrant for any place suspected to be indulging in sex selection

techniques or pre-natal sex determination; and

d) any other matter which may be prescribed.

Every Genetic Clinic/Ultrasonography Centre/ Genetic Counselling Centre/Genetic

Laboratory has to have a registration with the Appropriate Authorities and shall be

required to pay prescribed fees. Every such centre has to apply within 60 days of

commencement of the Act. The Appropriate Authorities, after holding an enquiry and after

satisfying itself that the applicant has compiled with all the requirements of the Act, shall

grant a certificate. The certificate shall be displaced in a conspicuous place at the Centre.

Every certificate shall be valid for five years.

There is a prohibition of advertisement relating to pre-natal determination of sex

and punishment for contravention on any person or organisation involved in such

advertisement shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term extending to 3 years and a

fine which may extend to 10,000 rupees. Any subsequent conviction will lead to

imprisonment of 5 years and the fine of Rs. 50,000.

The centre needs to maintain records in terms of different forms to be submitted to

Appropriate Authorities. Form F containing the information on the men/women subjected

to any pre-natal diagnostic procedure, and form G containing the consents of the

men/women need to be maintained by the centre. Appropriate Authorities should maintain

the record of Form H containing the details about the application by centres. The centres

should send monthly report to the concerned Appropriate Authority. Every centre need to

3

display prominently a notice in English to effect that disclosure of sex of the foetus is

prohibited under law.

There is a code of conduct to be observed by persons working at the centre. It

includes mainly: (i) not engaging oneself or helping in sex determination; (ii) not

employing unqualified people; (iii) not conducting the tests in place other than that

registered to conduct or cause to conduct female foeticide.

The Appropriate Authorities have a power to inspect the centre and seal and seize

any ultrasound machine capable of detecting sex of foetus used by any organisation, if it

has not registered with them. The machines could be released if the organisation pays five

times the registration fees to Appropriate Authorities. However, Retherford and Roy

(2003) observe that, “The law contains loopholes. Government laboratories and clinics

are monitored much more closely, than private laboratories and clinics, which are only

required to register under the Act. Also genetic tests are monitored much more closely

than ultrasound tests”

The law is easy to circumvent for both physicians and clients. The PNDT Act

seems to have little impact on sex-selective abortions. Arnold, Kishor and Roy (2002)

estimate indirectly that more than 100,000 sex-selective abortions, following ultrasound or

amniocentesis, have been performed annually in India in recent years. Even if there are no

data available directly on sex-selective abortions, there are number of indirect indicators

on the basis of which one could estimate the extent of sex-selective abortions. The NFHS-

II data on use of ultrasound facility and on sex ratio at birth provide useful clues pointing

to existence of substantial number of sex-selective abortions (UPS and ORC Macro,

2000).

The Census of India (2001) came up with shocking results of decline in sex-ratio,

particularly of children aged 0-6 years and provided more direct evidence of sex-selective