RF-TB-2.6.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

t- 2Of*'

(h'?2. )I

AaJ<S14^2. /2.« t \

/xj-rP yutj -7_

H

• f'P

5

.. ><i ■••

(

•

rJo-i'. 11 'R f3‘v-/T>

r-t.-

v

, T cf

,)

. b>*f

s<?c_ ,

i

l

o

f

i-t/

Ind. J. Tub.J993. 40, 129

Origin*11 Article

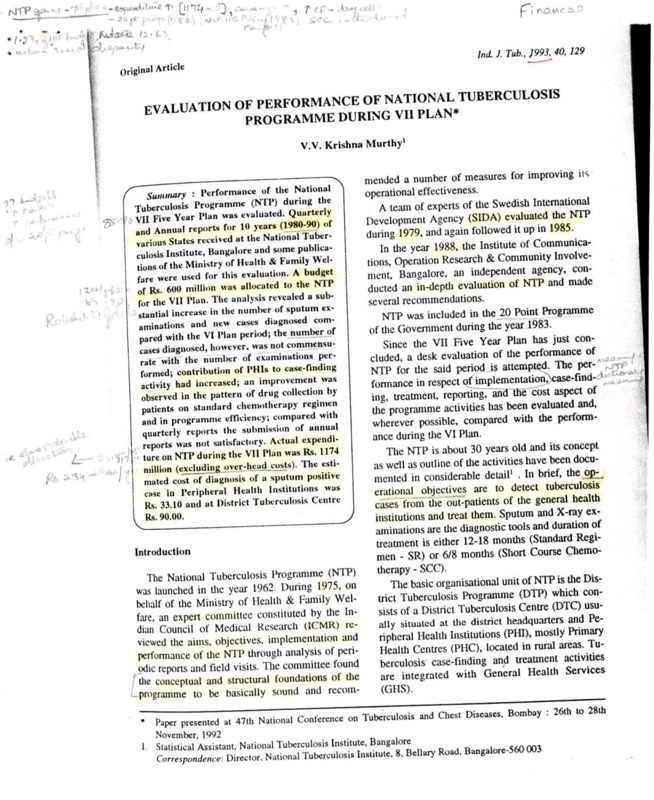

fvaluation of performance of national tuberculosis

evalua ion programme during VI1 plan*

V.V. Krishna Murthy1

I

7?

. T r jj

-df *

f

'

1^'^

■L, b ’• t '•

■In

various States received at lite National Tuber

culosis Institute, Bangalore and some publica

tions of the Ministry of Health & Family Wel

fare were used for this evaluation. A budget

of Rs. 600 million was allocated to the N 11

fur the VII Plan. The analysis revealed a sub

stantial increase in the number of sputum ex

aminations and new cases diagnosed com

pared with the VI Plan period; the numberor

cases diagnosed, however, was not commensu

rate with the number of examinations per

formed; contribution of PHIs to case-finding

activity had increased; an improvement was

observed in the pattern of drug collection by

patients on standard chemotherapy regimen

and in programme efficiency; compared with

quarterly reports the submission of annual

reports was not satisfactory. Actual expendi• ture on NTP during the VII Plan was Rs. 1174

million (excluding over-head costs). I he esti

mated cost of diagnosis of a sputum positive

case in Peripheral Health Institutions was

Rs. 33.10 and at District Tuberculosis Centre

Rs. 90.00.

Introduction

The National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP)

was launched in the year 1962. During 1975, on

behalf of the Ministry of Health & Family Wel

fare, an expert committee constituted by die In

dian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) re

viewed the aims, objectives, implementation and

performance of die NTP dirough analysis of peri

odic reports and field visits. The committee found

die conceptual and structural foundations of die

-programme to be basically sound and recom•

mended a number of measures for improving its

■

operational effectiveness.

■

A team of experts of the Swedish International

|

Development Agency (SIDA) evaluated the NTP

|

during 1979, and again followed it up in 1985.

■

In°tlie year 1988, die Institute of CommunicaI

lions, Operation Research & Community Involve|

ment, Bangalore, an independent agency, confl

ducted an in-depth evaluadon of NTP and made

|

several recommendations.

|

NTP was included in the 20 Point Programme

<

of die Government during the year 1983.

Since die VII Five Year Plan has just con

cluded, a desk evaluation of die performance of*

NTP for die said period is attempted. The per- .jvj

formance in respect of implementation?case-findin<», treatment, reporung, and the cost aspect of

die programme acuviues has been evaluated and,

wherever possible, compared with die perform

ance during die VI Plan.

The NTP is about 30 years old and its concept

as well as outline of die activities have been docu

mented in considerable detail1 . In brief, the op^

erational objectives are to detect tuberculosis

cases from die out-patients of die general health

institutions and treat them. Sputum and X-ray ex

aminations are die diagnostic tools and duration of

treatment is eidier 12-18 mondis (Standard Regi

men - SR) or 6/8 months (Short Course Chemo

therapy - SCC).

The basic organisational unit of NTP is the Dis

trict Tuberculosis Programme (DTP) which con

sists of a District Tuberculosis Centre (DTC) usu

ally situated at die district headquarters and Pe

ripheral Health Institutions (PHI), mostly Primary

Health Centres (PHC), located in rural areas. Tu

berculosis case-finding and treatment acuvides

are integrated with General Health Services

(GHS).

Paper presented at 47tll National Conference on Tuberculosis and Chest Diseases, Bombay : 26th to 28lh

November, 1992

1. Statistical

Assistant,

Corre^ndenee.

DirccTc^

B^'—560 003

EVALUAIION OF PERFORMANCE OF NTP

V.V. KRISHNA MURTHY

131

130

Table 1 Government health expenditure

Industrialized

countries

World

12.28

10.38

in relation to total expenditure in different countries in 1985*

Table 3 Implementation of DTPs during VI & VII Plan periods

Year

Developing countries

Africa

Asia

India

7.93

3.14

2.16

Pakistan

Sri Lanka

1.00

3.77

•Source : Health Information India - 1989

ft

(2.16%) w'as one quarter of dial in African coun

tries (7.93%) and one sixdi of that in industrial

Method

quarterly and annual reports tire also received at

die National Tuberculosis Institute.

The quarterly and annual reports of NTP re

ceived from various Slates, for the 10 years of die

VI and VII Plans (1980-85) & (1985-1990), at die

National Tuberculosis Institute (NTI), Bangalore

and various publications of die Ministry of Healdi

& Family Welfare, viz., Healdi Information India,

Performance Budget etc., have been used in diis

For the VII Five Year Plan, Rs. 600 million

was allocated to NTP. A comparison of die pro

portions of health budget allocated to die three

contemporary national health programmes and die

Budget allocations

The total financial outlay of die Vll Five Year

Plan (1985-90) was Rs. 1,800.000 million. The

-health services”

were

allocated 3.7%

Programme Implementation

ods, is given in Table 3.

Table 2

Family

welfare

1

2

3

Budget allocation (%)

1.8

1.9

Per capita expenditure (Rs.)

1985- 86

1986- 87

6.30

7.19

:

:

Total plan outlay

Budget allocations

■

7.63

8.22

Leprosy

Tuberculosis

4

5

6

/

12.6

2.4

"H.’S

1.12

0.18

0.15

1.01

0.18

0.15

Rs. 1,800.000 million

Cols. 2 & 3 : % to plan outlay

Cols. 4 - 6 : % to Col. 3

76

87

22.333

25.000

10.240

12.810

86

21.300

15.270

420

420

1990

438

378

Percent

46

51

54.

___

; ... •

....

m die VII Plan. At d>e end of die VII Plan. 86% of

>fl/

die urban community and 54% of die rural com-//

i-//

rise-finding

cpse-finding and treatment activities of fTI P. The

targets

targetsfixed

fixedfor die VII Five Year Plan period and

munity were provided widi die tuberculosisserv----ices under NTP.

1

' achievements

''

■ i related

are shown in Table 4.

A target of 17 million sputum examinations to

be done in PHCs was fixed and 11.65 million spu

tum examinations were performed, reaching 68%

of die target. Similarly, a target of 1.4 million new’

cases was fixed for die first year of the Vll Plan

(1985-86) and gradually increased to 1.6 million

annual reports are received at die NIT for moni

toring purpose. During 1990,167c of die expected

quarterly reports were received at NTI, a majority

of which were considered satisfactory for monitor

ing analysis. Hence, die reporting efficiency was

73%. However. onl^27% of die expected number

of annual reports were received of which only

2/3rds were wordiy of further consideration, re

ducing die reporting efficiency to 17%. It is to be

Implementation of NTP in various districts has

been a continuous process since 1962. The prog

ress in diis regard, over die VI and VII plan peri

Malaria

320 t

1980

1985

The NTP activities are reported monthly to the

District and Slate levels, quarterly and annually to

Slate and National levels. Copies of quarterly and

Budget allocation for various health schemes and per capita expenditure during VII Plan

Health

care

Implemented

Pills

Reporting

gramme was die least of die diree programmes.

(Rs. 67,000 million) of die plan outlay, as com

pared to about 3% in die previous six five year

plans. The percentages of government health ex

penditure to total expenditure in different coun

tries in 1985 is given in Table 1. The percentage

of health expenditure to total expenditure in India

No. of

rural health

institutions

During flic VII Plan, SCC was introduced

(1986-87), in a phased manner. At the end of VII

Plan, about 50% of the districts in lite country

were providing SCC. though not uniformly.

per capita expenditure (under plan) on various

health services, is given in lable 2.

It is seen from Table 2 dial die allocation of

1.7% of die healdi budget for tuberculosis pro

Findings and Inferences

Percent

.■C,-

health programmes like National TB Programme,

National Malaria Eradication Programme, Na

tional Leprosy Eradication Programme etc., and

die general health care services (Rs. 34,000 mil-

evaluation.

No. of

DTPs

At die beginning of die VI Plan (1980), NTP

Targets and Achievements During the VII Five

had been implemented in 76% of the districts and

Year Plan

46% of the rural healdi institutions in die country.

During die VI Plan, NTP was implemented in 44

Since inclusion of NTP in the 20 Point Pro

more districts and 2,570 rural healdi institutions

gramme during 1983. die Mii»stry of Health and

(RIH) as compared to 14 districts and 2.460 Kills * Family Welfare ha^e^fix^atmual'^sZ

ized countries (12.28%).

The budget allocated to health services in India

was shared almost equally by die Family Welfare

(Rs 33.000 million) programme, various national

Periodicity of reporting under NTP is

monthly, quarterly and annually, of which die

No. of

districts

mentioned here dial in die annual report, result of

cohort analysis is made available in addition to die

case-finding activity which occurs also in die

quarterly report. 1 he efficiency of die quarterly

report being 73%, die low efficiency of die annual

report is due to die unsatisfactory reporting of

treatment activity which in turn depends on the re

ceipt of treatment cards from PHIs and correctness

and legibility of die entries on treatment cards.

The rectification of diese weaknesses may im

.

.

- ----- , -

prove die efficiency of die annual report.

Table 4 Targets and achievements ofNTP during VII

Plan period

Activity

Target

Achievement

(%)

Examination of sputum

(million)

17.0

68

Detection of new tubercu

losis cases (million)

7.45

102

Percentage of cases detected

to total estimated cases

40

35-39

Percentage of disease arrested

cases out of those detected

65

Not available

Sources :

Performance Budget. Ministry of Health &

F.W. and Health Information India

for die fifdi year (1989-90) - amounting to an in

crease of 14% corresponding to die budget in-^

crease of 9% (not on I able). I lowever, Tbr die eti-

tire VII Plan, the target for die detection of new

tuberculosis cases was 7.45 million against which

a total of 7.6 million cases was reached, attaining

EVALUATION OF PERFORMANCE OF NIP

V.V. KRISHNA MURTHY

133

132

T.bl. s

100

V’ v”^" ’’‘ff

Increase

During Plan

Aclivity/lnstitution

VI

71

70

Id

VH

(million)

50

13.5

29

89

20

147

X-ray Examinations

OTP

10.5

Sputum Examinations

DTP

DTC

PHI

11.0

5.0

6.0

Sputum positive

cases

DTP

DTC

PHI

1.1

0.6

0.5

20.8

6.0

14.8

1.5^

0.7

0.7

3.2

4.8 >

Sputum negative cases

Contribution of PHIs (%)

Sputum examinations

Sputum cases

I

54

71

41

50

22

A

9

.

40% which was more or less achieved.

Case-finding activity

„,mposit.ve cases and 4.8 million sputum nega

te cases were d.agnoxd. showing

‘ncrease of

32% and 50% respectively over die V 1 Plan pe

riod PHIs had diagnosed 62% more sputum posilive cases in the VII Plar ; riod over die VI Plan

as compared to 117. in DTCs. indicating that the

case-finding activ.ty in DTCs might have almost

Diagnostic examinations

reached die optimum efficiency.

During die VII Plan, a total of 17 million X-ray

examinations and 24 million sputum examinations

were done (not shown on Table) Of these. 79% of

X-ray examinations and 87% of sputum examma

tions were done for die new out-patients at the

DTC and PHIs. In respect of newJGra^andjpu-

tum examinations, done during VII Plan, an increase of 29% and 89% respectively v»as observe

over die VI Plan period (Table 5). The increase

observed in die number of sputum examinations

was mostly contributed by the Pl Ils (»47%L

During die first year of die VI Plan (1980-81).

PHIsliad done0.54 inillionnamputumexamina

tions which increased by 307-/, (to 2.2 milliyn)

during die fifth year of the plan, compared to an

increase of 11% m DTCs (not shown on the

Table) The increase in the output of Pl Ils may be

due to die inclusion of NTP in the 20 Point Pro

gramme in 1983. However, the corresponding in

creases during the VII Plan were lOTI and 14'X re

spectively.

Contribution of PHIs in case-finding

During die VI Plampenod. 54% of total sputum

examinations and (41%) of the total cases diag

nosed were contribut'd by PHIs as compared o

71% and 50% respectively during Uie-VH Plan_Vperiod (Table 5). Considering dial PHh die ex

pected to contribute around 80% to die case-find

ing activity. 71% contribution in sputum examina

tions and 50% in die total cases found is encourag-

gThe trend in die contribution of PHIs in yearly

case-finding activities in relation to die total per

formance over die decade is shown in F.g. • The

increased contribution from PHIs during the VI

Plan period was conspicuous but marginal during

die VII Plan period.

During die VII Plan period. 1.45 million spu- .

of examinations done.

For comparison, the case rates among

putum examinations done in PHIs and DTCs at

e end of V, VI & VII Plan are shown The case

les, in PHIs at die end of die VI Plan (5.2%) and

II Plan (5.1%) periods were one half of dial at

: end of the V Plan period (11.1%). The above

nation was marginal in DTCs (12.7% to

.4%).

During 1980, die average number of sputum

aminations done in PHIs was 1700, and the case

e 11 1%. During 1985, the average number of

aminations had increased fourfold (69(X)) and1*:

case rate reduced to one half (5.2%) and the

ne trend, of decrease in die case rate with inase in die number of examinations, continued

mg 1985-90. May be. with die increase in

l num examinations, die quality of selection

fc sputum examination got diluted to a great

e ent Consequently, the number of cases

u gnosed was not commensurate widi die number

Chest Symptoinatics attending PHIs under-going

sputum examination

In NTP, chest symptoinatics (CS) attending

PHIs are eligible for sputum examination. It is

expected that consequent to the increase in spu

tum examinations tlic proportion of CS attending

PHIs and sputum examined would increase. The

numbers of CS in rural community and of lliem.

those attending PHIs (11.1% and 24.1%

respectively - Radha Narayan et al:) were esti

mated for the years 1980, 1985 and 1990. The

number of CS attending PHIs and of them those

sputum examined are shown in Table 7.

During 1980, 10% of the CS attending PHIs

were examined by sputum; this proportion in

creased to 47% during 1990. Despite this five fold

Table 7 Proportion of chest syinplouuilics attending

PHIs who were sputum examined

bit 6 Comparison of positivity rates according Io

institution doing sputum examination dur

ing successive Plan periods

The question whether the number of cases di

fill

|>TC

WP

1990

Fig. 1 Percent contribution of PHh in case-finding (1^80-1990)

CS attending Sputum

Pills

examined

in Pills

(estimated)

(millions)

Year

Al the end of Plan

Sputum positivity rate at different limes

would reflect the quality of sputum examinaugm.

1985

SP. Exam = Sputa examined, SP. Patients = Sputum positive patients

IIUt>< ill

agnosed remained commensurate with the sputum

examinations done is examined in Table 6 since it

Sputum positive cases

-

VII Plan

VI Plan

1980

I

102% of die target.

The target for die_£asCzIUhW- efticiency

(% total estimated cases detected) was fixed at

44

33

0

31

___ J SP. PATIENTS

ALL PATIENTS

50

O

V

VI

VII

11 1

12.7

12.1

5.2

12.3

7.4

—5.L^

11.4

7.0

I’eivcnl

1980

5.4

0.5

10

1985

6.1

2.5

41

1990

6.8

3.2

47

J

A

''

SP. EXAM.

53____________

V

»

f

EVALUATION OF PERFORMANCE OF NIP

V.V. KRISHNA MURTHY

135

134

Table 10 Expenditure (estimated) on diagnostic and treatment activities in NTP during the VII Plan

TableS Pattern of drug Collection (standard regimen)

Average no. of

Drug collection (%)

Year

O’

5

4

1985

1990

l.j

41

30

4-7

8-11

13

15

19

18

12+

collections

26

37

7

Expenditure (in million Rs.)*

ii

Institution

X-ray

Examinations

Smear

Examinations

DTC

79.1

8.0

87.1

(60)

525.3

(51)

612.4

(52)

PHI

41.3

15.7

57.0

(40)

504.7

(49)

561.7

(48)

DTP

120.4

23.7

144.1

(100)

(12)

1030.0

(100)

(88)

1174.1

(100)

(100)

10

’Initial defaulters

previously undiagnosed sputum smear cases pre- ;J

increase, nearly one half of the CS attending Pi lls

were not examined by sputum. An almost similar

observation has been made by Seetha el al .

senting diemselves for diagnosis.

Treatment efficiency is defined as the propertion of cases converted to sputum negauve status J

•

at die end of die treatment period out of those put

Treatment activity

The annual report of NTP provides the pattern

of drug collection by a cohort of patients i.c. pa

tients diagnosed during a specified period, each

one of litem having an equal opportunity to com

plete the optimum period of 18 treatment months.

On an average, about 50,000 patients could be

thus observed for their treatment every year. The

percentage of patients put on treatment making at

12 monthly collections in 18 months ranged

least

from 26 in 1985 to 37 in 1990. The pattern of drug

collection by patients on SR, during die years

1985 and 1990 is given in Table 8.

A comparison of die pattern of drug collection

by patients starting treatment during 1985 and

1990 reveals a shift to die right in drug collection

during 1990, indicating improvement in drug col

lection. During 1985, 60% of die patients put on

treatment discontinued dieir treatment before

making dieir 8di collecuon, which got reduced to

48% during 1990; during 1985, 26% of die pa

tients made 12 collections or more compared to

37% during 1990, showing a 42% increase, lhe

average number of drug collections per patient

during 1985 was 7 as compared to 10 during 1990,

on treatment.

Programme efficiency is, then, die proportion |

Overhead cost not considered

Percentages within brackets

Table 9 reveals dial over a decade, about 501

•finding efficiency & pro- ■ —---------------increase in die case-finuiug

gramme efficiency, and a marginal increase in du

Health

Institution

treaunent efficiency have taken place.

Estimated expenditure on diagnostic and treat

ment activities during the VII plan

Efficiency of NTP

During die VII Plan period, 41 million exaiw

nations (X-ray and sputum) were carried out at*

6.3 million tuberculosis cases were diagnosed

two activities.

Case-finding efficiency is defined as the pro

portion of cases dial could be diagnosed out of the

Grand

Total

1

treatment widi SCC was insufficient.

activities of NTP : die efficiency of die pro

gramme mainly depends on die efficiency of diese

Treatment

more in DTC. Moreover, expenditure incurred on

of cases estimated to become sputum negative out y Diagnostic activity

X-ray examinations, over die five year period, was

of die total diagnosable cases in the programme t

During 1974, Naganathan ct al4 had estimated.

(product of case finding and treatment efficicnfive times dial on sputum examinations.

the cost of a smear examination to be Re. 0.54, 'd'vr. ■

cies).

land NTI had estimated die cost per X-ray exami

Treatment activity

The above diree parameters, at different points

lnation Rs. 4.00 (not published). Considering die

of time, are given in Table 9.

general cost escalation, the cost of X-ray and

In NTP, cases are treated eidier for 12-18

Isniear examinations now have been taken as Rs. ..

months (SR) or for 6/8 mondis (SCC). SCC was

Table 9 Case-finding, .'ealinenl and programme

17.00 and Re. 1.00 respectively. Based on die num-'

introduced in a phased manner in about 2(X) of 378

efficiency of NTP al different Mies

Iber of X-ray and smear examinations done during^

_____

districts, by 1989-90. ______

The expenditure

to be inkhe VII Plan period, an expenditure of Rs. 144.1 incurred on treaunent by SCC and SR

Efficiency

l was estimated

Year

million is estimated for diagnostic examinations'

....

on die

basis of die proportion of cases treated by

Programme

Treat

Case

Table 10), 60% of which would be incurred at

eidier regimen. The drug cost has been taken asment

finding

..y TI Cs. This estimate is> one and a half times that

Rs.

125/per

patient

on

SR

and

ncurred in PHIs, tliougb die proportions of total

Rs. 725/- on SCC. It was estimated that an expen- :

8

28

27

1980

uberculosis cases and sputum positive cases diagdilure of Rs. 1030 million would be incurred for

9

26

36

1985

. tosed in DTCs and PHIs were not different (Table

treaunent, shared equally by DTCs and PHIs; a to13

33

41

____ 9 >)• Hence, die diagnosis of a case appears to cost

1990

tal expenditure of Rs. £174.1 million foiuhe diae-

showing an increase of 43%.

Material for carrying out a similar analysis ot

Case-finding and treatment arc the two main

Total

Tuble 11 Cost of diagnosing a case (during VII Plan)

Expenditure*

(million)

New

X-ray

,

The financial requirement for die above two

Uvities have been estimated to be Rs. 1174 mi " ;

p- 12% on diagnostic activity and 88% on treat

ment.

Cases diagnosed

(million)

New

Sputum

Cost of diagnosis

(Rs.)___

Sputum

negative

Sputum

positive

Sputum

negative

Sputum

positive

DTC

58.8

6.0

2.6

0.7

24.92

90.00

XC

35.7

5.2

2.2

0.4

18.59

92.95

24.02

79.52

MC/RC

NIP

9.6

94.5

20.8

0.3

4.8

1.4

33.10

Estimated cost

cost of

of an

an examination

examination :: X-ray

X-ray :: Rs.

Rs. 7.00,

7.00, Sputum

Sputum smear by microscopy : Re. 1.00. Overhead

costs not considered

XC = X-ray Centre; MC = Microscopy Centre; RC = Referring Centre

II

■■■ J.IL-

—r?--—

■4

. *

v ♦

I

> ?

I

i

136

V.V. KRISHNA MURTHY

nostic examinations done and treatment given

during the VII Plan period. This estimate may be

viewed against die budoeuiry allounent of Rs. 600

million only for NTP during the said plan period.

Cost of diagnosing a single case

Under DTP, both X-ray and sputum examina

tions are done for diagnosing cases (sputum posi

tives or negatives) in DTCs and X-ray Centres

(XC), whereas in Microscopy Centres (MC) and

Referring Centres (RC) only sputum examinations

are performed. Based on die number and types of

diagnostic examinations done, die cost of diagnos

ing a case can be estimated. The estimated cost of

diagnosing a sputum positive case and a sputum

negative case is presented in Table 11. «

It is observed dial die cost of diagnosing a spu

tum positive case in a DTC (Rs. 90.00) and XC

(Rs. 92.95) is diree times dial incurred in a MC or

RC (Rs. 33.10). The observation, dial die cost of

diagnosing a sputum negative case (X-ray case) is

less dian dial of diagnosing a sputum positive case

should not lead to the erroneous conclusion dial

case-finding by X-ray examination is cheaper. It

should be borne in mind that cost estimates under

programme conditions, wherein Pills do many

sputum examinations to find fewer cases and

DTCs and XCs use both X-ray and sputum exami

nation and find more sputum negative cases, are

based on far more negative than sputum positive

cases diereby reducing the cost of diagnosis of a

sputum negative case.

Conclusions

effective and regular supervision and be

utilisation of trained personnel may impi

die quality of the annual reports.

4. Though there has been an improvemt

in the pattern of drug collection,

37 % of the patients put on SR made 12

more collections. Regular and adeqtt

supply of drugs to the PHIs may further ii

prove die drug collection pattern.

5. There has been a substantia] increase

the programme efficiency.

6. Nearly 80% of programme funds a

spent on treatment after excluding esta

lishment cost.

7. The cost of diagnosing a sputum posit!'

case in the programme was Rs. 79.5

calling for a more detailed analysis of co

effectiveness.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to Dr B.T. Uke, Directo

NTI, Dr A.K. Chakraborty, Addl. Director, Mr\

Murali Mohan Sr. Statistical Officer, Dr L. Sury;

narayana. Chief Medical Officer, for their vail

able suggestions, colleagues of Statistical Sectio

and Monitoring Section for statistical help, Mr (

Sathyanarayana & Mrs MJ. Jayalakshnii, Statist

cal Assistants, Monitoring Section for informr

discussion regarding functioning of NTP, Mr B.F

Narayana Prasad for graphics, Mr P. Pcrumal an

Miss T.J. Alamelu, for secretarial assistance.

References

1. The targets for die VII Plan have been substantially achieved.

2. There has been a substantial quantitative

1. Nagpaul, D.R. District Tuberculosis Control Pro

increase in sputum examinations done

and cases diagnosed, but the number di

agnosed is not commensurate with the ex

aminations done indicating that the qual

ity of selection for sputum examination

had deteriorated. Nearly 50% of the chest

2. Radha Narayan, Susy Thomas, Pramila Kumar

S, Piabhakar S, Ramprakash A.N., Suresh Td

Srikantaramu N; Prevalence of chest symptom!

and action taken by symptomatics in a rural com

munity. Ind. J. Tub.; 1976 23, 160.

symptomatics attending PHIs were not re

ferred for sputum examination. Neverthe

less, the contribution of PHIs to die case

finding activity had increased, coming

nearer to die expectations.

Annual reporting was not satisfactory. An

gramme in concept and outline : Ind. J Tub

1967, 14, 186.

3. Seetha M.A., Rupert Samuel G.E. and Parimall

N. Improvement in case-finding in district tuber

culosis programme by examining additional sputurn specimens; Ind. J. Tub.; 1990, 37, 139.

4. Naganathan N., Padmanabha Rao K, & Rajala

kshmi R.; The cost of operating and establishin

a tuberculosis bacteriological laboratory; Ind j

Tub.; 1974, 21, 181.

G .

kb’ .

: Sfl 46

speciality B. Will all these sources conji]|jja to subsidise for long the conferences

which are increasing in number and dost as time goes by?

A time has already cpqje when few apjpngst Pl can gffprd to attend a

conference at one’s own cost. On the other hmm, then is an immeasing tendency

on the part of the employers, both governmental and non-governmental, to

depute only those persons for a conference who have to present a paper. Will it

be worthwhile to hold a conference if only those who are to present a paper

attend it since their number is not likely to be large in a two or three day

conference and a conference lasting more than 3 or 4 days is virtually impossible

for reasons more than one?

Many questions aris$. Ar$ conferences jp such large npnjbers necessary?

Will the object of the conferences be defeated if their number js restricted? For

example, if the National Conference on Tuberculosis and Chest Diseases is held

in alternate years and in the intervening year conferences are held at State level,

would it in any way be detrimental to the objective? One may even go a little

further. Instead of each State organising its own conference in alternate years,

if three or four States could come together and hold a regional conference by

rotation in each state, there will be considerable saving in cost without any

reduction in scientific gains? Probably, the academic contents will even improve

as the conference will draw op the talents of 3 or 4 states instead d3±.cujng on

its own. And if such a course is adopted, the money saved tuereby can be div

erted towards meeting other even more pressing needs of medical and social

relief.

Doc« the prestige of a conference depend merely on its venue? Is a Con

ference organised in a 4 or 5 star hotel in any way more educative or informative!

than a conference erganisedin the unpretentious lecture hall of a college or any

other public institution or organization? Will it detract from the success of a

conference if much of the lavishness is replaced by some austerity? If the prime

object of a conference is education and scientific advancement will severe pruning

of the appurtenances reduce its appeal or attendance in any way?

These are some of the questions which everyone must seriously think

about. Matters are likely to come to a head sooner than later if the trends of the

last few years are allowed to continue unchecked. It is time that we consider

these issues thoroughly but dispassionately and take rational decisions in keeping

with our resources while retaining the academic benefits conferred by these

conferences.

C-Qi.-

■y/

.

: r.rsb

ret

r-...

\.

Ind. J. Tub., 1984, 31, 41

“OUTLOOK FOR TUBERCULOSIS CONTROL 2000 A-D."

K.N. Rao*

I consider it a great honour to have been tion in 1948 stepped up global tuberculosis

invited by the Tuberculosis Association

„ . „of India

v

control measures with the support of UNICEF

to deliver the second Robert Koch-Ranbaxy

I'

viz BCG_Vaccination: Chemotherapy; Research

Oration instituted so generously

\ byv Sri

ri Bhai

ai CfC jn developed countries these measure^Mohan Singh, the well known pharmaceutical wcrejrLaddltion to the socio-economic and

industrialist, at this National Conference on ' wcnare^ mc^Ijre^ such as nutrition,' housing,

Tuberculosis and Diseases of Chest. I thank elivfrbnmeiltr social security, health insurance

them for their kindness.

and health laws. The developing countries

under the guidance of WHO and IUAT took

2. Background

up anti-tuberculosis measures within their

resources to cover the entire population—•

Robert Koch’s epoch-making discovery of prevention by mass BCG Vaccination pro

the tubercle bacillus in 1882, changed the gramme, early detection of cases and domi

outlook for the control of tuberculosis until ciliary chemotherapy (as recommended bv the

the discovery of Streptomycin in 1944. In his Tuberculosis Chemotherapy Centre, Madras),

programme for combating tuberculosis he organisation of tuberculosis demonstration

recommended prevention of infection by & control centres, rehabilitation, research, etc.

isolation, of the patient in hospitals, screening

of the patient at home, disinfection of the patieThe Sth Expert Committee of W.H.O.

nt’s excretions. He further recommended the

(1964) standardised the Indian programme

. I

organisation_pf dispensaries, heaIth education approach for all developing countries The

of the population, particularly that of the District Tuberculosis Control Programme

patients’ and their families, and comt-L.

., through the existing health facilities is the keyiRulsory

rcgjstration of allj:ases._Even in his time, the

,K“ stone of the programme. This was later stream

incidence of tuberculosis was declining in_Europe'] lined, in the light of experience bv the 9th

with improvement Fn the sQcio-economic Expert Committee in 1974. /However, in

conditions of the people and the introduction majority of the developing countries there

of health insurance and social security for has been no improvement in the epidemiological

industrial workers. In 18X7, Sir Robert Philip situation. ~As a result of the Increase of populain line with Koch's ideas established the first tioh And a" stagnant socio-economic and nutri

anti-tuberculosis dispensary' which was the tion situation, there is an absolute increase

forerunner of the network of modern specialised in the number of Tuberculosis cases in these

anti-tuberculosis services

and dispensaries countries during the last three decades.

in the system of primary health care. The

Internajianal Union Against Tuberculosis which 3. Situation Analysis at Present

imposed an obligation on members was born

___________ •______________________________________ tx.

.

/. •

on

Oct. 1*7

17, 1O3A

1920 in ----succession

to the Central

Tuberculosis

of thehealth

leading health

tuberculosis

is one of istheone

leading

ro _

_...» ^....-1

•tflC ____

Pr<;v!?btlP*L

of Tuberculosis.' problems in South

A:;- t-dsy.

--1 E-East Asia

today. S:.?.-,

Sixty rlive

The developing countries for want of resources, percent

of

this

region

’

s

population

..

‘

— .-gior.'c pcpalaticr. of

cf one

men, money and materials had very meagre billion live in India.

.' SEA “Region

India. At present the

control measures. Towards the end of the has over kn_millionn estimated cases of which / / ^7

Second World War, the work of UNRRA and four million arc sputum positive.

voluntary

organisations

through

the

International Tuberculosis Campaign, was

The joint WHO/IUAT study group surveyed

commendable. The discovery of other drugs- the global situation in 1982 and considered

INH, PAS,

Thiacetazone.

Rifampicin, it a scandal that 4 million new highly infectious

Ethambutol,

Pyrazinamide, etc.

widened cases appear each year and a similar number

the scope of tuberculosis control/cradication of non-infectious cases of tuberculosis,

as a realizable goal in some countries. The particularly in children, also occur. At any

establishment of_____________

the World Health

given Organisamoment, the total number of cases

•President. International Medical Sciences Academy. RBA Buildings, Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, New Delhi-3

Pa^Goa* RObCTt KoCh'Ranbaxy Ora,ion delivered at the 38ih National Conference on TB & Chest Diseases,

ic.N. raO

outlook Jon TtamcuLosa -Control 2000 a.d.

is of the order of 15 qi_2Q—million out of and recommended integration of tuberculosis,

which 10 million expectorate and about three- control measures in thc_Primary Health Care

million oeopk dic_ of Tuberculosis every approach for the attainment of the goals of

S-ThH^hsidcred a paradox in that we tuberculosis control ajd. health for all by 2000

have efficient means of prevention, case-finding A.D. In the field of Research in ‘uberculosis,

and complete cure. n is also a dilemma in that Immunology, Bacteriology, Short-term Chemo■ganisational,

andJ—the human factors therapy. Epidemiology, and Economics of

1 tfiflftnClRlj

---------- r-----jbstacies to the full application of Tuberculosis Control Programme were high

ctmstitute-obstacies

lighted. Ww’

•*

( available knowledge.

Tabu 1

4g

The main obstacles to the present National Primary Health Care: the Need

Programme which require improvement include •

the following :

'

*

Primary

health Care includes

eight vital

elements: neartn

health eaucauon

education;; looaanu

food and nuinuuu,

nutrition;

...

,

elements:

irM) The Ministry of Health requires strong provision of safe drinking water and sanitation;

central technical support'to guide and matemai and child health and family planning;

supervise the N.T.P. There is need for immunization; prevention and control of

improving the manageriaLtcani at the endemic diseases, appropriate treatment for

State and intermediate levels. The common diseases and injuries, the provision

programme specialists should Consider of essential drugs, the organisation of an efficient

themselves as specialised technical sup- referral system both institutional and laboratory

■ port to the General Health Administra- services and evaluation.

x

tion. Tha

The taame

teams ck/\itlr1

should con/a

serve nAt

not rtnlv

only

as specific programme specialists but

Dr. Mahler, in his address at the World

, v’- JhWSt also influence the functioning of Conference on Tuberculosis and Chest Diseases

the whole health system ;

1982, summarised that the future of tuberculosis

lies with Primary Health Care and Health for

2) the process of integration has not All by 2000 A.D. ‘Health for All’ means that

been properly a^reciated by all the there is an equitable distribution among the

members of the Health Services as population, of whatever health resources are

there is split responsibility^.

available, so that people will use the available

for better health care and that

the peripheral health services are approaches

health begins at home, in the schools, in the

inadequate to . icet the requirements factories

and in the fields. He also affirmed

of the total population;

that primary health care should by accessible

all with community participation, and that

4) lack of funds restricts all health activities to

will help themselves with their own

ihcludingtuberculosis control measures; people

health development. Dr. Mahler further stressed

the need for the New International Social

5) lack of continuous supply of drugs;

and Health order, tastly he implored that the

tuberculosis control programme be seen as

6) lack of training of key medical staff;

a stone in the construction of the health system

built upon Health for All and PRIMARY

7) lack of continuous evaluation;

Health Care; and that it is not for the stone

to decide its place but for the builder who selec

8) lack of community involvement;

ted it. There is no doubt that all Tuberculosis

agree with the above assessment and

9) lack of health services research in to workers

the problem of programme delivery; will help in this great adventure.

and

As the socio-economic conditions of the

10) lack of constant review of any variation people in the developing countries continue

to be stagnant, the quality of life as determined

in the programme

by P.Q.L.I. (Pyhsical Quality of Life Index

In addition, lack of good health behaviour based on Literacy %, infant mortality rate

of people, frequent transfer of staff and insuffi and expectation of life of the people) is below

the average 55 when compared to developed

cient salaries to them make the situation worse.

and middle income wnt-L.. ffable I)

The WHO/IUATstudy group(1981) meeting

P.Q.L.I. component indicators, per capita

which was considered as the meeting of the

F

te domestic product and calories intake

century, laid emphasis on socio-economic. State

jneasufes in addition to BCG' vaccination^for for Indian States (1971) with International

cEUdren, case-finding and chemotherapy, etc. comparison are shown in Table II and the rural

40

Average Per Capita GNP and PQLIfor 150 Countriee, by Income Groups, Early 1970s (Weighted by Population)

Total Population

(Millions)

Per capita GNP

(J)

PQLI

Low-income countries (N =42)

(Per capita GNP under $300)

1,242

155

40

Lower middle-income countries (N=38)

(Per capita GNP $300—699)

1,081

340

67

Upper middle-income countries (N=32)

(Per capita GNP J700-S1.999)

417

1 047

High-income countries (N«=38)

(Per capita GNP J2,000 and over)

1,040

4,404

92

All countries (N = 150)

3,781

1,476

65

& urban P.Q.L.I. for States in India in Table

111

Mortality has been reduced but morbidity

continues and the environmental factors remain

unchanged. The defaulters, relapses, occurrence

of new cases are indicative ortfie presence of

other factors. Thus tuberculosis prevalence

and incident in any country serve as indices

of the social organisation in the countries.

The greater prevalence of the disease in the lower

The urban/rural differences in the quality

of life of the people in India in different states

indicate that there is need for emphasis on socio

economic and nutritional factors along with

tuberculosis). Since the advent of chemotherapy

in Tuberculosis in 1944, so far the emphasis has

been on the drug, and the causative organism

without sufficient consideration to the other

factors such as environment and Nutrition.

Fig 1.

Drug

Bacilli

Ehvironmental factors Nutrition

x. .

,

, , ,

.

uugsuj, uic stauuai, me parauox ana

4-

the dilemma described earlier are the result of

Our t ,

vuvuxv, MAVlMfVJ T«UJ U,WV“

duced. Anti-bacterial therapy has its limitations.

different picture.

(

68

’

s e

China Concentrated on four key issues:

China’s three level health care net work; the

involvement of the people, the health man

power development and theTmancing of health

care through Health Cooperatives. China’s

tremendous political commitment to the task

of improving the quality of life of the people,

especially in the rural sector, may be well worth

emulation by the other developing countries.

While each country differs from others in

its historical, cultural, social, economic and

political background and circumstances, the

health care system in China presents many

useful points of reference for those seeking

primary health care in other settings. Even

with limited resources, primary health care

can be established and Tuberculosis Control

measures integrated. Political" w71T’ neonle’s*

^i^a£i0I}.’.cAponsiuii

exPansi0n oi

?f neaitn

health services lor

for

yrnuviyMivu,

primary health care, provision of uninterrupted

**

—

vuiuuuuii seem

to be the secret of success of the programme.

$■-

Table 2.

PQU Component Indicators, Per Capita State Domestic Product, and Calorie Intake for Indian States, 1971, *ith International Comparisons

Actual

Indexes uf

STATE

1. Andhra Pradesh

Life

expectancy

(Years)

Literacy

Infant

mortality

rate

PQLI

Life

Expectancy

1

2

3

4

43

47.7

54.1

28.2

56.1

SDP per

Calorie

capita (Rs.) intake per

(1970-71

day

1972-73

average)

Infant

mortality

rate (per

1000 live

birth)

5

9

7

8

109

303.7

2040

137

275.0

6

Egypt, Iran, Bolivia

Haiti, Papua New Guinea,

Pakistan.

2. Assam/Meghalaya

37

34.1

41.4

36.0

51.3

40

39.5

38.3

42.1

53.4

144

395.7

1612

Uganda, Morocco

3. Gujarat ^

48

46 9

61.3

35.8

56.3

93

300.3

2220

Indonesia, Lestotbo

4. Karnataka

70

63.6 .

77.0

69.3

62.8

58

302.0

1842

People’s Rep. of China, Columbia.

5. Kerala

6. Madhya Pradesh

37

45.9

37.8

26.6

55.9

145

262.3

2779

Haiti, Pakistan.

7. Maharashtra

49

46.4

55.0

44.8

56.1

107

422.7

2281

Indonesia, Honduras

37

37.4

428

31.1

52.6

134

254.3

Haiti, Pakistan.

8. Orissa

112

473.3

2832

Botswana, Burma

2044

Zaire, People’s Rep. of Yemen

64.3

28.8

52.7

67.4

50

9. Punjab

s

10. Rajasthan

33

32.1

45.9

21.9

50.5

127

310.0

11. Tamilnadu

46

43.1

51.8

42.8

54.8

114

355.7

1498

Iraq, Rhodesia, Tunisia

Senegal, Nigeria, Nepal.

27.9

25

12. Uttar Pradesh

42.8

42.6

40

ALL INDIA’

21.2

'W

Nations with same PQU

24.6

48.9

182

260.7

2307

34.1

54.6

134

349 3

1985

5

4-

weighted averages for all states and union territories except as noted in the appropriate

•The "ALL-INDIA" figure used here and in other tables that follow are

Census or SRS sources. They thus represent a wider coverage than the 12-state averages otherwise used.

.nrcrrt

HI

ipiH

8 O’Z’S? >o>

c

O q

S’ n

q

o

K 2

Ez

S'

I

hl

P’Fil 1

o

a

P

c

>

2

>

Q

o’

I

&

21

p

.•O

Mt

I

I[I

$

(

a:

I

£

p

b>

F I I a.

p

I

g’

rr

5O

fI

t

S'

2

g

S g-2

2§

P if!

B-3 o A $r< © 3-• ~

L<2

o i

So£

o 2--O

3 S

&O

^E-

O? J'S o cl? V ■<

w £. ri 2. ? =

c

gp

I

I

I

f

£

O'

5

2

2

s

3

MJ

8

£

C

a

o

3r

I

■O

Pt’lP I i

hl

e

s

‘O

L!

SO

£

s

3

§

£

u*

£

p‘

£

bJ

a

o

K

*2

o

a

s-

K

p

5

t?i awiftsiii

til

p

g.

8

I

? 2.C

JO

I

K

o

o

CM

O\

00

O'

tJ

CM

s

? s a-

&

oo

£

’ll

i

i

I

3 £

p*

t-

j

!

3

K>

►—

3

■o

I

8

o

>

b

K.N. RAO

52

the disease process will be made in this decade made in other related areas will no doubt change

than in the hundred years since Robert Koch the outlook.

discovered the tubercle bacilli. Tuberculosis

The developing countries should encourage

immunitv is cell mediated. T. Lymphocytes

which react directly and specifically to antigens research in health education, econoniics_of

uw

wu

—

tuberculosis

control programmes particularly in

are responsible for the cell mediated immunolo

the integration of tuberculosis control measures

gic phenomenon. T

T. cells

cells do not themselves

l'"-;

effect the cell mediated antibacterial immuni in Primary Health. Care Health Services

ties but act indirectly through hormones— Research/Operational Research is of para

Lymphokines J that

they secrete. These mount importance and more so as the year

Ivmphokines have no immunological properties. 2000 A.D. is near. Can Indian workers make a

They in turn act through macrophages which are contribution towards this end? Yes, they can,

attracted to the site of (he lesion.'bacilli and if there is a will at all levels.

activate them to kill the bacilli and ingest these

The once high hopes for the speedy conquest

(see fig 2) is a virgin field production of

Lymphokines or anything stimulate their of tuberculosis likcTnose for malaria eradication

tpected have faded before the complexities of applying

production will help. Much was exj

is ----area available control technology, in developing

of Levamisole^New developments in this

countries. The governments of developing

are envisaged.

countries deplored the fact that little improve

ment had been achieved during the past two

Simple

Model*

of

cell

mediated

immunity

in

Fig. 2

decades. The Resolution of the World Health

Tuberculosis.

Assembly WHO:36:30 (Annex) expresses succ

inctly the present outlook and the need for

Antigens

concerted action.

+

Peripheral blood

Mono-nuclear cells

(T. cells. Monocytes)

5. Conclusion

I

I

T

The health of mankind requires the coopera

tion of the government, the people, the health

professions and the voluntary organisations

like the IU AT and its affiliates in the achievement

of our goals through PRIMARY HEALTH

CARE. The Tuberculosis Association of India

should spearhead the fight against Tuberculosis

through PRIMARY HEALTH CARE. AND

HFA by 2000 A.D.

\

It has now been realised that socio-economic

factors,standards of livingand nutrition enhance

resistance to infections. As one approaches

2000 A.Dr, along with new knowledge there

is also the fear of nuclear war, the building up

of armaments and the spending of resources

for the extinction of the human species.

_________l_

r

--1 on the principles

Economic

development

based

of the New

International------Economic

Order . is

Oi

.-.v.. ----------------paramount for the conquest of Tuberculosis,

9^„r and Koch

In --------------the meantime* “So tell P

Pasteur

or whoever they

, be, That they have not seen

the last of my comrades ana

Lymphoidncs

Cell or Cell contact

Macrophages

H2O3

Killing or

Inhibition of

M. Microti BCG

Research :

The areas of immunization, Immunology,

studies in geo bacteriology of the Tubercle

Bacillus, case-finding and treatment,particularly

short tc^mchemothcrapy.discoveryofnewantituberculosis drugs, epidemiology and sociology

of tuberculosis require attention. The progress

•••For Tubercle Bacillus'’ by James Hurd Keeling (1831-1909) From the Song of the Squirt—a

Koch’s Tuberculin,

satire o"

WJNDZR—TAI ORATION. 1981

Ind. J. T:ib , 1984, 31. 53

CHEST DISEASES IN INDUSTRY

P.A. Deshmukh

I am extremely grateful to the Executive

Committee of the Tuberculosis Association

of India for selecting me for this year’s Wander

F.A.l. Oration. I consider it an honour. I would

also like to express my deep sense of apprecia

tion to the House of Wanders for their

noteworthy contribution to the advancement

of medical science.

Early man lead a nomadic life. His day

used to be spent in hunting and fishing—arrang

ing food for his family. In searching for game

and green pastures for his herd of animals

he wandered from place to place. Seriously

ill and very weak persons could not stand the

rigours of hard nomadic life. Survival of the

fitt-st was the rule. Air was clean and forests

abundant. Man needed tools for his hunting

and weapons for defending himself. These

were made of stone, then bronze and then iron

was used.

As time passed, farming and housing were

developed. Man started leading a community

life and then he started discovering ways

and means to make his life easier—more

comfortable, more enjoyable.

It was noted that some rocks contained

substances which were of much utilitv. Mining

was started. As the superficial supply started

dwindling man started going deeper in the soil.

Proccssess were established to obtain a refined

product from the rocks which had to be crushed,

washed and powdered. And in this process

working persons had to breathe air containing

dust.

Turning back the pages of history, it is

seen that the concept of occupational health

is not a new one. It had its inception

antiquity. As early as Sth century B.C.. Hippoc

rates mentioned about the breathing difficulty

of rock miners.

Ancient citizens who were carrying a

mechanical trade had a social stigma. Socrates

is Said to have stated that persons who were

in mechanical trade were dishonoured citizens

as these trades damaged the bodies of the

workers and that they had no time to perform

the duties of friendship and citizenship. Thus,

the working man was neglected in ancient

medical practice. It was only in the 18th Century

that Ramazzini (1713). the father of Occupa

tional Medicine stressed the impoitance of

studv of working environment and its impact

on the human body.

With the development of science

anO

technology, new products for use in homes,

transportation, farming etc were developed.

Newer industries were established. With the

creation of new industries, working force,

mainly from villages started coming in urban

areas. People uprooted themselves from village

life and started settling at new industrial sites

in urban areas. In the beginning, they had to

face acute problems of housing and adjusting

to new environment. Housing shortage led

to breeding of slums in urban areas. Industries

added air pollution. In the developing nations,

industries develop in a haphazard manner

initially. They are established without proper

thought to their location, direction of wind,

disposal of effiuent. Developing nations want

to industrialise fast and in the process, the rules

and regulations about proper development

are ignored. It is only when industries get

established and start paying back that roads,

water supply, housing and medical facilities

are developed.

On the other hand, the industrial processes

themselves are in some respect a hazard to

human body. Today, I am devoting my talk to

diseases of the Lung in industrial environment.

While it may not be possible to include each

and every disease of the chest in industrial

environment, I will deal with the principal

diseases that one comes across in Industries:

I. Tuberculosis

2. Pneumoconiosis

a) Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis

b) Silicosis

c) Asbestosis

3. Byssinosis

4. Industrial Bronchitis and other respiratory

conditions

•Chest Physioan, Tam Main Hospital: Superintendent, A.M. Hospital and Professor of Chest Diseases, M.G.M.

Medical College, Jamshedpur.

HEALTH

Reprinted from Rhe Indian Journal of Tuberculosis, Vol. XXX, No, 2 April 1983.

TUBERCULOSIS CONTROL IN INDIA—CURRENT PROBLEMS AND POSSIBLE

SOLUTIONS

G.V.J. Daily

Attempts to reduce the problem of tuber

culosis through organised efforts had their

beginnings in India in the late thirties. With the

introduction of chemotherapy, organised home

treatment of tuberculosis from the TB clinics,

situated mainly in cities and district headquarter

towns, was started. The mass BCG campaign,

started in 1951, gave the first indications that

the problem of tuberculosis in rural areas

could be as big as that in the urban areas.

The need for extending case-finding and treat

ment of tuberculosis to the rural areas, in addi

tion to urban areas, was confirmed by the

sample survey (1) of tuberculosis conducted

by the I.C.M.R. The concept of offering tuber

culosis services as a component of the compre

hensive health care delivered by the general

health services was evolved in the country

over two decades ago. The concept has been

endorsed by the WHO (2) (3) and recommended

for application in its member countries in

accordance with the developmental situation

in each country. In evolving this concept,

cognisance was taken not only of the^sizc and

extent of the problem of tuberculosis but also

of the fact that the rural areas continue to

remain ill served. In the words of Morley (4)

“Although three quarters of the population in

most developing countries live in rural areas,

three quarters of the spending on the medical

care is in urban areas, where three quarters of

doctors live. Three quarters of the deaths are

caused by conditions that can be prevented at

low cost, but three quarters of the medical

budget is spent on curative services, many

of them provided for the elite at high cost”.

But, the picture is changing. Primary

Health Care, as enunciated by the WHO (5),

and to which India is strongly committed,

holds the promise that a drastic reallocation

of national resources will be made, in an all

ouV cffort to provide essential health care to

the rural population. The report of Working

Group appointed by the Govt, of India on

Health for All by 2000 A.D. (6) recognises tuber

culosis services as an important component of

Primary Health Care. The inclusion of tuber

culosis in the nation’s 20—point programme

is indeed the beginning of the realisation of the

commitment.

In dealing with the tuberculosis problem

and the National Tuberculosis Programme,

it is appropriate to realise that in the past, and

even to-day, several organisations, notably

the Tuberculosis Associations, institutions and

private practitioners have contributed consider

ably and continue to do so, for the alleviation

of the suffering caused by tuberculosis. However,

in this presentation on the problems of and

prospects for tuberculosis control in India,

the rural areas as also the National Tuberculosis

Programme have been selected for the main

emphasis. It is probably appropriate to do so

as that is where most of the problems exist.

1.

The Problem of Tuberculosis and the Prog in mine of Combat

The epidemiological dimensions of the tuber

culosis problem in India

India is one of the few developing countries

of the world where epidemiology of pulmonary

tuberculosis has been studied for a relatively

long time. In recent years, a large amount of

documentation has come to be available mainly

through epidemiological studies conducted in

different parts of the country. In most of these

studies, either one or more of the three main

epidemiological tools, viz., tuberculin test,

chest X-ray examinations and bacteriological

examination of sputum samples have been

employed to study one or more of the following

main epidemiological indices: prevalence and

incidence of tuberculous infection, prevalence

and incidence of abacillary and bacillary pul

monary tuberculosis, and prevalence and

incidence of drug resistance to the main anti-_

tubercular drugs.

Though tuberculin sensitivity in the general

population has been studied for oyer 40 years,

compar isons between findings at different times

and often between findings obtained at the

same time but made by different workers, is

beset with difficulties. This is often because

the tuberculin products used by investigators

at different times were different. The early

workers used old tuberculin(7) which gave

place to purified protein derivatives (PPD) of

tuberculin. In India the first PPD preparation

to be used was PPD RT 19-21(s) followed by

RT22(9), RT 23(10) Cl 1) and finally PPD-S(12).

In addition to changes in the product, criteria

for definition of infection have changed from

mere differentiation of an individual as ‘positive’

♦T.B. Specialist, National Tuberculosis Institute, 8, Bcllary Road, Bangalore-560 003.

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXX, No. 2

■

/■>,

.r-l

46

C-

(

G.V.J. BAILY

or ‘negative’, to exhaustive analyses of the

distributions of the size reactions(13). It has

also been realised that tuberculin reading being

somewhat subjective, the training and standardisation of the tuberculin readers was a

crucial variable not only for obtaining valid

findings but also for comparison of findings

at different times in the same population(14).

The methodology of such training and standar

disation of tuberculin readers has been detailed

recently(15).

Such methodological differences are not

necessarily without rationale. Technological

developments necessitated the methodological

changes. While such changes helped in obtain

ing better estimates of tuberculous infection

they also rendered the comparisons somewhat

difficult. Some of these difficulties can be

overcome through concurrent comparisons of

two or more tuberculin products in the same

individuals. More recently, study of the risk

of infection by converting data on the prevalence

of infection into risk of infection through the

method developed by the Tuberculosis

Surveillance and Research Unit of the

International Union against Tuberculosis(16),

some more problems can be overcome. Thus,

data on tuberculin sensitivity obtained at

different times by different individuals are

rendered comparable.

Changes in radiological and bacteriological

techniques have been less spectacular. One

of the main recent changes in sputum culture

techniques is the methodology of homoge

nisation of sputum samples. Change-over from

the use of oxalic acid(l) to alkali(l 1) for homo

genisation, has not greatly influenced the

estimates. As regards X-ray techniques, inter

pretation of photofluorograms taken in an

epidemiological survey, wherein most of the

individuals X-rayed have normal chest X-rays,

varies from reader to reader. In one study(lO)

the agreement between two readers, for photo

fluorograms read as ‘probably tuberculous

and active’, was only 55 % and for other less

definite categories much lower.

These arc only sonic of the differences

between different surveys done in India during

the past 50 years. Despite the above and other

differences, the data obtained in different

surveys provide a reasonable idea of the

problem of tuberculosis in the country. Table

below summarises epidemiological data as

obtained from some of the surveys conducted

in the country. The list is by no means complete.

Table

The prevalences and incidences of tuberculous infection, abacillary and bacillary cases as obtained in some epidemiological

surveys in India

(All ages)

Infection (%)

Author

Prevalence

1

Seal, ct. al. 1954(20)

2

3

38.9

4

5

6

7

8

0.39

0.14

11%

(of all

cases)

0.4

0.1

1.0

0.25

9

1.55

Raj Narain, ct. al. 1963(10)

38.3

2.0*

N.T.I. 1974(14)

30.4

1.77

Goyal et. al. 1978(21)

2.00

0.4

1.9

0.41

1.72

50

Bacillary cases (%) Isoniazid resistance (%)

Annual Prevalence Annual Prevalence Annual Prevalence Annual

Incidence Incidence

Incidence

Incidence

I.C.M.R. 1959(1)

TB PT 1980(12)

X-ray cases (%)

3.0

2.3

0.3

10% (

(of new

cases)

*Estimated from prevalence data

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXX, No. 2

4

TUBERCULOSIS CONTROL IN INDIA - CURRENT PROBLEMS AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

None of the above data can be considered

as representative of the whole country or any

particularly large area. Indeed, it may well be

impossible to draw a sample representing the

whole country nor may it be necessary

to do so/fhe available data give us the follow

ing main epidemiological dimensions of the

problem of tuberculosis in the country:

(i) The prevalence of infection is of the

order of about 40% in all age groups

rising from about 2% in the youngest

age group to about 70% at'age 35.

Thereafter, it remains almost constant.

Incidence of infection is highest in

individuals between the ages of 5 and

20 years. The risk of infection is of the

order of about 2-4% per annum.

(ii) The prevalence of disease confirmed

by X-ray is of the order of about 2%

among total population aged 10 years

and more and pf these, about 20 per

cent (0.4% of total) are bacillary., The

annual incidence of new'cases is about

one third of the prevalence: 0.13% of

the total population aged 10 and above

becoming new bacillary cases of tuber

culosis each year.

(iii) The prevalence as well as incidence of

disease are higher as age advances

and again, higher among males than

among females, male to female ratio

varying from 3:1 to 5:1.

(iv) The incidence of disease, i.e., the number

of new cases occurring during a period

of time, among the newly infected is

substantially lower than those that have

been infected some time ago. Only a

fraction of all new cases occur among

those infected for less than 5 years.

(v) The trend of tuberculosis appears to

r

be almost constant over the years

except in some cities where better

services for diagnosis and treatment

have been available for some time(2l).

(vi) Tuberculous infection as well as disease

are more or less uniformly distributed

in urban, semi-urban and rural areas.

Thus the vast majority of pulmonary

tuberculosis cases arc to be found in

rural and semi-urban areas, where

more than 80% of the country’s popu

lation live. However, there are certain

pockets where prevalences and inci

dences are much higher than in other

areas.

47

(vii) Non-specific sensitivity is highly p~prevalent in the entire country though

there are significant differences bet

ween different areas: it is definitely

lower in areas situated at higher

altitudes(38).

Very little is known about the prevalence

and incidence of childhood forms of tuber

culosis in the community as most studies

reported uptil now deal with morbidity of

childhood forms of tuberculosis in the hospital

situations. However, from population surveys,

one fact is known: the incidence rate (risk of

disease) of bacillary disease among the freshly

infected (infected for less than 1 year) is over

fixc times that among those who are infected

for more than I year(17). If the risk of bacillary

pulmonary tuberculosis is so high among the

freshly infected, who arc mostly children, it is

quite likely that the risk of other forms of

tuberculosis is also quite high but the newly

arising cases of primary disease might go

undiagnosed especially in the rural areas.

Data on the prevalence and incidence of

drug resistance is conflicting. In a rural area

in South India, the prevalence of Isoniazid

resistance, among cases diagnosed in a survey,

is 12/^11). The spectre of increasing drug

resistance in the community may be real if

larger and larger number of cases are diagnosed

but treatment efficiency continues to remain

low. It may well be so with continued depen

dence on less acceptable standard chemotherapy

regimens along with increasing case-finding

efforts.

Thus, tuberculosis continues to ravage

India even 100 years after the discovery of the

tubercle bacillus. Indeed, there are some

indications that the problem may be showing

a slow, a very slow, downward trend (II) in

some of the epidemiological indices, such as

prevalence of infection in the very young

(0-4 years) age groups. Viewed as a problem

of suffering of the individual, of the family

and of the community, tuberculosis can rightly

be classified as one of the biggest public

health problems in the community especially

in the vast ill-served rural population of India./'

2.

The need for the continued study of epide

miology of tuberculosis in India

In the not so distant past, when epidemio

logical data in India were scanty, much reliance

was placed on the observations made in highly

developed countries. In the last few years, since

epidemiology is being studied more inten

sively in India, it has been realised that

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXX, No. 2

•i

48

G.V.J. DAILY

epidemiology of tuberculosis can be very quarter town. A stratified random sample of

different in different countries. For instance, the PHIs was selected and at each centre, an

in the BCG trial conducted in Britain, more investigating team identified symptomatics from

than half of the new cases of tuberculosis the out-patients and carried out sputum

occurred among those who, at the time of intake examinations. Extrapolating the findings in

were not infected, i.e., tuberculin negative(l8), the sample to the entire district it was shown

whereas in the (Chingleput) BCG trial conducted that, if all PHIs in the district participated in

in India, only 6 % of all new cases, occurring case-finding according to the recommendations

in the first 2| years after intake, occurred among i.e., examined the sputum of all new patients

the initial tuberculin negatives(12). The reasons attending the PHIs who are aged 10 years and

responsible for such differences may be attri- above

above and

and have

have cough

cough for

for more

more than

than 22 weeks,

weeks,

buted to differences in host response to nearly

nearly 2,000

2,000 bacillary

bacillary cases

cases of

of tuberculosis

tuberculosis

infection, or to environmental variations, or1 could be diagnosed during a period of one

differences in the characteristics of the infect- ;year. Considering

~ that' 15the prevalence of direct

ing organisms. For instance, it has been known smear positive cases in' i an average Indian

that the tubercle bacilli isolated from patients district (pop: 15,00,000), is about ?,000, nearly

in India are generally of a much lower virulence 65% of these cases could be diagnosed. The

than those isolated from British subjects! 19). study, thus, showed that the District TB

The epidemiological significance of this varia Programme has a considerable potential for

tion is not known. Similarly, the differences, case-finding.

if any, in the host responses of different popula

tions as also differences in evnironmental

Similar studies on the potentials for treat

factors, including the effects of the environ ment by the PHIs are not reported. However,

mental non-tubcrculous mycobacteria prevalent an operational investigation(24) was conducted

in the areas, is not known. Identification of at the main TB Centre in Bangalore to study

these and many other such undetermined factors the acceptability of treatment by patients in

demands an abiding interest in the study of the terms of the levels of treatment completed by

epidemiology of tuberculosis and extending bacillary patients of tuberculosis put on anti

it to areas of new interest. Further, India being tuberculosis chemotherapy with any one of the

a vast country, some epidemiological investi two standard regimens, Isoniazid and Thioace

gations will have to be conducted in more tazone (TH) self-administered daily and, Strep

tomycin and Isoniazid twice a week (SHTW)

than one area.

under supervision. The main results of chemo

The National Tuberculosis Programme therapy were assessed in terms of the bacterio

is essentially

a

permanent country-wide logical status at the end of one year as related

programme based on epidemiological, sociologi to the status at intake. While the procedures

cal and economic conditions prevailing in the of management of patients i.e., motivation,

country and integrated into the general health defaulter actions etc., were exactly according

and medical facilities at both the rural and to those recommended in the programme,

urban levels. The programme is organised and assessment of results was more intensive than

supervised by a nucleus of specialised staff at that recommended in the programme. Only 31 %