RF-TB-2.2.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

70

different from that of an uninfected individual - Koch’s phenomenon. Years

later, the tuberculin test became the indispensable tool of the epidemiologists.

TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA — THE PROSPECT*

I

S. SlVARAMAN**

So intense must have been his disenchantment with the failure of tuberculin

that he gave up research in the field of tuberculosis altogether and went on a

I am grateful to the Executive Committee

microbe hunting spree all over the globe. He visited several countries, inclu

of the T.B. Association of India for their kind

ding India and discovered the causative micro-organisms of several diseases ’.gesture

in inviting me to deliver the Wander

like cholera, sleeping sickness, relapsing fever, Rinderpest, Anthrax etc.

'•TAI Oration. Realising the honour that has

Robert Koch may well be described as the father of the discipline of

Microbiology. His techniques of making and staining of smears, culture techni

ques etc. are still in vogue today. He was responsible for making microbiology

as the basis of public health measures. Harley Williams has very rightly called

Robert Koch ‘the greatest technician in Medical Research’.

Honours came to him galore. He was elected a member of the German

Academy of Sciences and was awarded the Noble Prize in Medicine in 1905

for his outstanding work on tuberculosis. In his memorable address at the Noble

Prize Award function, he said with uncanny foresight “1 have performed my

investigations in the interest of public health, to which 1 hope they will bring

greatest benefit. To combat tuberculosis, I recommend prevention of infection

by isolation of the patient in hospitals or screening at home, disinfection of the

patient’s excretion, care of the patient in organised dispensaries, information

and health education of the population and, above all, of the patients and their

families and compulsory registration of all cases”. It is a great tribute to him

that the control of tuberculosis even today, 77 years later, is based, almost

entriely on these principles, except for the addition of chemotherapy which

became available in 1947 and has so revolutionised the management that

tuberculosis has ceased to be a puplic health problem in many developed

countries and isolation is no longer necessary.

The Centenary of the discovery of the bacillus is being celebrated this year

all over the world. Befitting tributes are rightly being paid to Robert Koch, a

colossus amongst medical scientists of all times. The Centenary should, however,

also be an occasion for taking stock of the state of tuberculosis control in our

country, consolidating our achievements and devising ways and means to

improve our strategy in respect of those procedures where our achievement

has so far been unsatisfactory. It is an irony that inspite of the technology and

know-how’ of control being available, tuberculosis still continues to be our

Public Health Enemy No. 1. With the revised strategy in respect of case-finding

and treatment in the rural areas under the National Programme, the added

impetus of tuberculosis being given a priority in the 20-Point Programme of the

Prime Minister, it should not be difficult to tame tuberculosis before the 20th

Century ends. This will be possible only if all medical and para-medical

personnel, voluntary organisations and the community as a whole put their

shoulders together with a sense of commitment in the fight against this scourge.

been bestowed on me by this award, I must

Confess that my contribution in the field of

^Tuberculosis research, compared to that of my

‘illustrious predecessors, is insignificant. Only

’.Stalwarts in our speciality have been selected

[’■'so far to deliver the prestigious Wander Oration,

'.•and this time the Tuberculosis Association has

achosen a humble Tuberculosis worker to dis

charge the responsibility. My distinguished

■fellow delegates must, therefore, hear with me

«if I make a deviation from the earlier Orations.

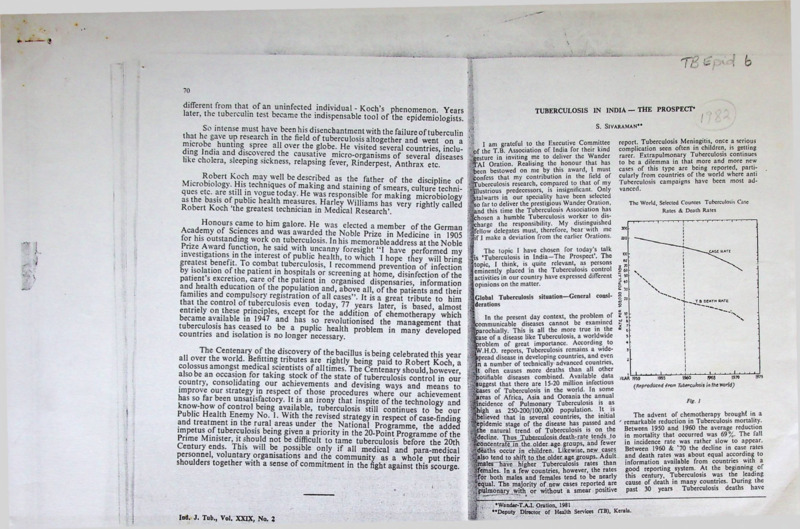

The World, Selected Countcs Tuberculosis Case

Rates & Death Rates

The topic I have chosen for today’s talk

is ‘Tuberculosis in India—The Prospect’. The

topic, I think, is quite relevant, as persons

eminently placed in the Tuberculosis control

activities in our country have expressed different

opinions on the matter.

Global Tuberculosis situation—General consi

derations

In the present day context, the problem of

communicable diseases cannot be examined

parochially. This is all the more true in the

case of a disease like Tuberculosis, a worldwide

Mproblem of great importance. According to

®V.H.O. reports, Tuberculosis remains a wide

spread disease in developing countries, and even

„ ;in a number of technically advanced countries,

‘4t often causes more deaths than all other

■‘notifiable diseases combined. Available data 7teAR two

1,75

^Suggest that there are 15-20 million infectious

(Reproduced from Tubercuhsis in the World)

,‘Stases of Tuberculosis in the world. In some

Jaretts of Africa, Asia and Oceania the annual

Fig. 1

>‘gincidcnce of Pulmonary Tuberculosis is as

Shigh as 250-200/100,000 population. It is

The advent of chemotherapy brought in a

-^believed that in several countries, the initial

idemic stage of the disease has passed and remarkable reduction in Tuberculosis mortality.

Between

1950 and 1960 the average reduction

e natural trend of Tuberculosis is on the

•^decline. Thuj^Tubcrculosis death-rate tends to in mortality that occurred was 69%. The fall

in

incidence

rate was rather slow to appear.

Concentrate .fiT the older age groups, and fewer

>‘deaths occur in children. Likewise, new cases Between 1960 & ’70 the decline in case rates

/-'•also tend to shift to the older age groups. Adult and death rates was about equal according to

/.males have higher Tuberculosis rates than information available from countries with a

jiferriales. In a few countries, however, the rates good reporting system. At the beginning of

'7(or both males and females tend to be nearly this century, Tuberculosis was the leading

^cqual. The majority of new cases reported are cause of death in many countries. During the

. 'pulmonary .with or without a smear positive past 30 years Tuberculosis deaths have

S

■ .

Ind, J. Tub,, Vol. XXIX, No. 2

report. Tuberculosis Meningitis, once a serious

complication seen often in children, is getting

rarer, Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis continues

to be a dilemma in that more and more new

cases of this type arc being reported, parti

cularly from countries of the world where anti

Tuberculosis campaigns have been most ad

vanced.

•Wandar-T.A.I. Oration, 1981

*’Deputy Director of Health Services (TB), Kerala.

I

.«

72

TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIa-THB PROSPECT

S. SVAltAMAK

decreased to the point that in countries having

reliable statistics, Tuberculosis is responsible

for a very small proportion of deaths irom all

causes. However, in some countries including

ours, Tuberculosis continues to be the leading

cause of death among communicable diseases.

Even today, with all the modern facilities avail

able. millions continue to develop the disease

and many die of it.

Data on the risk of Tuberculous infection

has certain advantages over other epidemio

logical indices. But, unfortunately, this informa

tion is not available for many countries.

However, information available from a few

countries suggests that in the technically

advanced countries, the risk of infection is

low. According to Blciker of Netherlands

(1973) it is probable that in the majority of the

developed nations, the risk of Tuberculous

infection is below 5,'1000; may be 1-3/1000

and in a few countries this may even be below

1/1000. He concluded that the risk of tuber

culous infection was declining in the developed

countries by about 10% or more each year.

Some studies done or assisted by the TSRU

and 1TSC (International Tuberculosis Surveil

lance Centre) have helped to determine the

risk of infection and its trend in many countries,

both developed and developing. The risk

of infection in developing countries was thus

found to be between 1-4% (10-40/1000). Again,

in the developing countries the risk of Tuber

culous infection was seen decreasing only

slowly or it remained static.

Tuberculosis situation in the different regions

and countries of the world

Encouraged by the global eradication of

Smallpox, the question is being asked by many

as to whether Tuberculosis could be eradicated

next. To gain perspective on this question, the

U.S. Department of Public Health. Education

and Welfare division collected world statistics

from various sources and a world-wide status

of Tuberculosis has been critically assessed in

a book entitled ‘Tuberculosis in the World’

(1976). Antony M, Lowell, chief of the Statistics

and Analysis Section of the U.S.D.P. utilised

W.H.O reports, statistical publications from

various countries for compiling the data on the

world Tuberculosis situation and, wherever

necessary, available information was obtained

through

personal

correspondence

with

numerous National Health Service officials.

The data 1 furnish on the Tuberculosis situation

today regarding all countries except India are

only cxtracts/reproductions from this useful

book.

Ind. J. Tob., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

Western Hemisphere

From the statistics available for 1973, the

North-West territories of Canada, Mexico,

Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Panama

Bahama Islands, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Guadc

loupe. Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Ecuador, Co

lumbia, French Guyana, Brazil and Argentina!

had a case rate above 50/100,000 population.

Of the above, the North-West territories oi

Canada, Peru, Bolivia and Paraguay registered!

case rates above 100/100,000 population. Bolivia

had a case rate of 413/100,000, one of the

world’s highest. This country' with a population*

around 5'million in 1972 registered 9,029 new

cases. About 53% of the population of Bolivia

consisted of Native Indians. In certain areas ofg

this Republic even 62% of the population was|

found infected with a 10% infection rate in the;

0-4 year age-group.

The lowest case rates in the region were;observed in Canada. U.S.A., Belize, the Canals

Zone of Panama, Cuba, Jamaica, Dominican’/

Republic, Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Martinique,!}

Barbados, Trinidad, Guyana and Surinam,

t'i

In Canada, the notification rate in 1973$

was 16.1/100,000 with a very low rate of 7/j

100,000 in certain areas and a high rate of:;

279/100,000 among the Eskimos. Case rate!

among the native Indians was 158/100,000. a

16.9% of all cases of Tuberculosis consisted J

of non-respiratory Tuberculosis. Tuberculosis’^

death rate in Canada in 1972 was only 2.1/

100,000. The Province of Ontario with 8 million's

residents forming 36% of Canada’s population:;

in 1973 accounted for 28% of their new’ cases.;

Of the 1176 new cases notified in Ontario

Province in 1973 only 39.5% were born in

Canada. 9.4% were native Indians and the rest S

51.1% were emigrants (Chinese, Indians,

Pakistanis and other Asians). A network of*a

units. Tuberculosis Clinics and Sanatoria make /j

up the system of Tuberculosis control in

Canada. About 83% of Patients arc treated as

out-patients and only 17% arc admitted for

treatment to hospitals. Prophylactic drug treat

ment is being given.

In the United States of America notification

rate of Tuberculosis was reported as 14.2/

100,000 in 1974. Death-rate had fallen by then

to 1.7/100,000. Maior reduction in case rate

was noticed in Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis manifestations appear

ed to be slowly increasing. All States, large

cities and county health departments have some

type of TB control programme as part of their

public health activities. Since 1960, Tuber

culosis control division of their Public Health 71

-f

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

u

TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA-THE PROSPECT

S. JlVAWUls*

vice coordinates governmental, voluntary

I professional activities in Tuberculosis conI Even though the local or State Health

I

75

people of that continent in general arc very

high. Health resources arc scarce and its dis

tribution is unequal. The reforc Tuberculosis,

Malaria, Leprosy, Yellow fever, Trachoma etc.

flourish there. Tuberculosis is regarded as a

major problem in most of the countries of

Africa.

Morocco, Spanish Sahara, Mauritania, Mali,

Togo, Swaziland and South Africa have a noti

fication rate exceeding 100/100,000. Many

countries such as Libya, Egypt, Senegal, Ghana,

Nigeria, Gabon, Congo, Zaire, Kenya, Angola,

Tanzania & Zimbabwe have notification rates

above 50/100,000. For countries like Sudan,

Algeria, Ethiopia, Somalia, Botswana, Zambia,

Ivory Coast etc. notification rates are not

available. Niger & Cameroon, however, have

notification rates below 24/100,000.

Though this continent on the whole has a

serious Tuberculosis problem, the sum total of

the problem is confined to a population of

about 30 crores (less than half the population

of India). Already control activities have begun

in some countries and the trend of Tuberculosis

can be expected to decline.

Asian conn tries (Fig. V) <£• countries of the Wes

tern Pacific region of W.H.O. excluding India

Among the countries of Asia high noti

fication rates have been recorded in countries

such as Saudi Arabia, Japan, Korea, Hongkong,

Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines,

Indonesia and most of the Islands in the Pacific.

Regarding Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangla

desh, though reliable data arc not available,

there is every reason to believe that the problem

is probably at its worst in these countries.

Macao, an island in the western Pacific region,

with a high density of population of 16,250

persons/sq. k.m., has one of the world’s highest

morbidity and mortality rates recorded in 1973.

The morbidity rate was 469/100,000 population

and the mortality was reported as 76.1/100,000.

Afghanistan, Pakistan & Bangladesh

In Afghanistan, overall infection rate is

reported as around 50% of the population.

In Pakistan, available information shows that

prevalence of Tuberculosis in the 1970s was

as high as 4.7%, may be the highest now re

ported in the world. Bangladesh with a popu

lation of 70 million people reported 84%

infection and an infection rate of 46% in the

0-10 year age group. It would therefore appear

that Pakistan and Bangladesh probably nave

the most serious Tuberculosis problem in the

whole world.

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 1

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA-THE PROSPLCT

77

S. KVAXAMAN

Ytah 3

T16rT

U.S.S.R. consisting of l/6th of the Earth’s

Surface had an estimated population of 25

/.crores (1974). In early 1960s large scale anti

TB measures started in this country. In 1968

>it was further strengthened by enacting suitable

legislation for the improvement of Public

Wealth in general. The general Public Health

Jand special anti TB measures have resulted in

She improvement of epidemiological indices

i'.^n the U.S.S.R. During the period 1964-73

'^Tuberculosis morbidity dropped by 47.5% in

what country. This was especially impressive

»n children. Morbidity of extrapul monary Tuberijculosis also declined to the point that almost

Jgno eases of some forms of disease were notified

;yn the U.S.S.R. Genito-urinary Tuberculosis

Jwas the most common disease among the

’gextrapulmonary diseases.

■j

BCG vaccination is considered in the

• 'jU.S S.R. as the most effective preventive

■.^measure. Mass vaccination to the new born

Tand revaccination upto the age of 18 years and

Jin some cases upto 30 years are given. Chemo' iprophylaxis is considered second in importance

<i|as a preventive measure. With all the great

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

achievements in Tuberculosis control in that

country, they still consider Tuberculosis as an

important health problem that affects consi

derably the well-being of the people and the

economy of the country. Eradication of Tuber

culosis in the U.S.S.R., they believe, is one of

their important State tasks. Exact morbidity

and mortality positions arc not known.

In China, with the largest population among

the countries of the world, statistics of Tuber

culosis morbidity, mortality etc. were not

available to the W.H.O. in 1973. However,

those who have visited that country observed

that there has been a remarkable improvement

of Public Health due to elimination of most

serious infectious diseases including a reduction

in their Tuberculosis problem. All the same,

the extent and variety of literature that have

appeared on Tuberculosis control and treat

ment in Chinese Journals suggest that Tuber

culosis is still a disease of major concern in

that country.

Tn 1949, China probably had a Tuberculosis

prevalence of 3-9% and the estimated TubcrInd. J. Tub,, VIo. XXIX No. 2

S. SIVA RAM. AN

culosis mortality during that period was 230.

100,000 population. A decade of anti-Tuberculosis campaigning in China brought in a

decline ol Tuberculosis prevalence in their

cities to 1%. In 1958, Tuberculosis mortality

in Peking was 46/100,000 population with a

further reduction later.

Tuberculosis in children used to be very

common, especially Tuberculosis Meningitis

(I/3rd of Tuberculosis in children). Even during

1950s China was up-to-date in the treatment

of Tuberculosis and started using S.M., I.N.H.,

PAS, Viomycin etc. A nation-wide BCG vacci

nation began in China in the mid-fifties. Imme

diate goal was to vaccinate all new borns and

all healthy children below 15 years. By 1964

more than 90% of newborns were vaccinated.

Manpower to meet this programme was or

ganized by selecting teachers of Nurseries or

Elementary Schools and by training them in

Tuberculin testing and BCG vaccination.

Japan—Immediately after the second World

War. Tuberculosis was so widespread in Japan

that the morbidity rate for Pulmonary Tuber

culosis was 10%. The mortality also was as

high as 187.2/100,000 population. Anti-TB

measures started very early in Japan In 1951

a TB control Law was enacted. It laid down

methods for diagnosing and treating patients

and for protecting the population. ITie law

also allocated various tasks at Governmental

level and at each of the Prefectures. The law

thus provided for BCG vaccination and registra

tion of all new cases. Even compulsory hospitali

sation of patients was enforced. With such a

vigorous campaign, ably supportcd'by the Japan

Anti-TB Association, the achievement of Tuber

culosis problem reduction was unique. By

1973, the case rate had fallen to 118/100.000

population. In 1969, the case rate was 196.

Death rate (1973) was only 11/100,000 There

was a remarkable reduction in the notification

of cxtrapulmonary tuberculous disease

Philippines with40 million population scat

tered over7000 islands stretching over 1000 miles

had a very high notification rate of 328/100.000

(1972). Death rate during this period was

64/100,000. The trend of Tuberculosis in this

country however appeared to show a decline

since the year 1969.

Oceania Fig. VI.

Indonesia. Population of 125 million (1973)

scattered over 5 large and/3000 small islands

forms an arc between Asia and Australia.

This country launched TB control . activities

in 1952 when BCG vaccination received high

TUBERCULOSIS IN 1NDIA-THB PROSPECT

79

priority. Case detection by sputum examination

and treatment with supervised intermittent

treatment are now practised. Tuberculosis

problem is considered very high with a pre

valence rate of 0.6% sputum positive patients.

No doubt the problem of Tuberculosis in

the Western Pacific region is a major one with

some adverse factors. However, the population

involved in this region is below 30 crores (ex

cluding mainland—China).

Australia has a very low notification rate

of- 10.5/100,000 (1973). Tuberculosis mortality

during this period was also very low 1/100,000.

This is one of the lowest death rates prevailing.

In Western Australia, non-Australian bom

persons contribute 50% of the cases. Case

rate for non-Australians ranges from 18-31/

100,000 compared to 8-12/100,000 for Australian

born persons. Non-Australian born comprise

27% of the population.

New Zealand Population is 89% Europeans,

natives 8%, Emigrants from Pacific Islands 2%

and others I %. Overall notification rale in

NewZcaland was steadily declining until recent

years when due to large scale miiyaf;on, the

trend of decline has slo - down.

The Tuberculosis situation in our country

Tuberculosis is known to have existed in

India from time immemorial. It continues to

be a major problem of public health interest.

Until recently our knowledge regarding its

distribution in India in different age groups,

sexes, and also in different places was meagre.

Even today there arc widespread misconcep

tions regarding the diagnosis of the disease and

its treatment. If in the past, there were no health

statistics and no notification on the morbidity

and mortality, even today the system that pre

vails in India is far too incomplete and un

satisfactory. Though it is a disease of antiquity,

actual statistics on the incidence, prevalence,

mortality etc. of Tuberculosis became available

in any part of the world within the last hundred

years only (we know that the disease was proved

with certainty as a communicable disease, and

the causative agent was isolated only about

100 years ago).

For the first time in the history of Tuber

culosis in our country it was only in 1920 that

any epidemiological data on this disease was

collected. Sir Leonard Rogers, on the basis of

2? long years of postmortem studies conducted

in Calcutta, found that 17% of the total deaths.

were due to Tuberculosis. On the basis of the’

decennial estimate of crude mortality for

about 9%,of mortality due.to. all causes in that

.911-21, the Tuberculosis mortality for India population. The death rates were the highest

was computed for the first time as .800 per in 55 years and over—age group and the lowest

100,000. This was probably not a true estimate mortality was in the 5-14 years group. An

as the postmortem studies were on hospital increasing trend in mortality with increasing

deaths and it is unlikely that hospital deaths age was also noticed. According to Official

could truly represent the actual death rale. reports, Tuberculosis mortality for our country

It was Lancaster, who from Rogers’s estimates as a whole is 80-100/100.000. One thing is very

and from other available information computed clear, and that is, as in all countries of the

mortality for some of the Cities in India and world the mortality trend in India is certainly

reported that in most of the Indian Cities the one of decline. However, we shall not lose

mortality rate would be higher than 400 per sight of the fact that a mortality rate over

100,000. Later in 1949 Me Dougal estimated

population is the highest death rate

(Tuberculosis mortality m'h'ndia as 200 per 80/100,000

now in existence anywhere in the world. This,

i 100,000. FrimodL-Mollcr’s estimate during this

[period for" Madanappallc and surrounding no doubt, is highly disturbing.

J rural areas was 253 per 100,000. He also found

Tuberculosis infection as an index of the

I a rapid decline in the Tuberculosis mortality Tuberculosis situation in a country has growing

j in that area to a low level of 21.1 per 100,000 importance. For the first time in India, Dr.

I by 1954-55 (explained as a result of intensive Ukil in .Bengal, one of the pioneers in T.B.

i anti-tuberculosis measures introduced in that ’work introduced Tuberculin testing and BCG

area). A longitudinal study to estimate the vaccination in our country. Though countrywide

! Tuberculosis mortality was undertaken by Tuberculin surveys have not so far been carried

' Chakra borty et al from National Tuberculosis'

out in India, extensive testing was done as part

rhstitutc during the period 1961-68. They of our BCG Campaign from the year 1948.

found the annual cause specific death rate due With all' the“labunac and limitations inherent *

to Tubcrc_ulosis_as...84_perJ 00.000population \ in this effort, for the first time, it became

| aged 5 years and above and this represented

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

Ind. J. Tub.. Vol. XXIX. No. 2

k.

s. SiVA&AM.\N

possible for us to estimate the overall prevalence

of Tuberculous infection in the different age

groups. Without going into the details of those

findings—-well known to all of us. I wish to

mention that it became evident that infection was

widespread in our country both in the rural and

urban areas. The risk or chance of contracting

infection by a person in India was so high that

one had every' possibility of acquiring it before

one reached 20 years of age. Considerable work

in this line was done by Ukil, Benjamin, Sikaad

Pamra, Raj Narain, I.C.M.R. and the National

Tuberculosis institute. 1 wish to refer only to

one study done in South India by the National

Tuberculosis Institute from 1961-68. Prevalence

of infection in that population group was 30%

(25% for female and 35% for males). The

rate increased with age upto 45 years. In the

case of females there was a slowing down after

the age of 15 years in contrast to that for males.

The incidence of infection, a very useful epide

miological index, was also obtained from this

study which showed a rate ranging from 0.84%

to 1.5%. This broadly corresponds to the 1-2%

reported by Frimodt-Moller. The BCG pre

vention study done in Madras showed the

infection rate in the study area to be considerably

higher. For all purposes we can believe that

the annual infection rate in India today may be

anything between 1-2% or 10 to 20/1,000. Com

pared to the infection rate of 5/1,000 for many

of the developing nations and 1-3/1,000 for

the developed nations, our infection rate is at

least double the average of developing nations

and 10 times that of developed nations. In a

few of the developed countries, the infection rate

has fallen to very low levels of below 1/1,000.

Thus the available annual rate of infection in

our country also depicts the serious nature of

our Tuberculosis situation.

Prevalence and Incidence of Tuberculosis in India.

For the first time in 1945 Dr. P.V. Benjamin

estimated from certain observations that about

2.5 million persons suffered from Tuberculosis

in our country. During 1955-58, when the

National Tuberculosis Sample Survey was

conducted in India under Dr. Benjamin’s initia

tive' (ICMR Survey), we got for the 6rst time

many useful baseline data which helped us to

appreciate the extent and nature of the problem

of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in our country

Since then we know that the disease was widely

prevalent throughout the length and breadth

of India and that even in rural India the preva

lence of the disease was almost the same as

in the urban areas. We also found that males

suffered more from pulmonary tuberculosis

compared to the females and that in the males

particularly the disease prevalence increased with

tuberculosis in india-tkh prospect

81

the increase in age. Two and half decades after present level of efficiency, has a potential of information that the bulk of the TB patients in

the National Sample Survey today, for rnakifig -Accelerating the natural decline.’’ The study the country stayed in the rural areas and Tuber

estimates of the Tuberculosis problem m our Undertaken by National Tuberculosis Institute culosis was widely scattered made it imparative

country we largely depend on The results of the K a rural South Indian population where virtua- that the programme in the country should be

NationaESurvey. This preSTcamenfw cettainly

no Tuberculosis control .facilities existed one that reached every nook and corner. There

fore, in the year 1959, Govt, of India established

unfortunate. However, after the National Sample Showed the following:

the National Tuberculosis Institute at Bangalore

Survey, seme other surveys have been carefully

to formulate a comprehensive, realistic and

conducted at Delhi, Madanapallc and Banga

["

V

“

The

annual

rate

of

Tuberculosis

infection

economically feasible Tuberculosis Programme

lore all of which show that the prevalence of

previously

uninfactcd

children

and

in

adults

for

the entire country. By 1962 National Tuber

bacillary cases of Tuberculosis was about_400/

100,000 population, a finding in agreement »."-was found to be about 1% (10/1000). The culosis Institute could evolve a programme for

I

’

T

ncidcnce

of

Tuberculosis

(confirmed

by

culture)

the country based on very solid scientific data

with the National Sample Survey. It was also

found that this rate did not appreciably change i ' v/as about J/1000 (excluding children below 5 obtained from the studies undertaken at the

until 1968. At least in the Delhi area a reduction •Wears), About 30% of newly detected cases National Tuberculosis Institute. Chemothera

of bacillary cases was noticed, bringing down its l.fiiamc from the population uninfected at an peutic Research Centre, Madras and other

prevalence to.2£M)-300/l 00,000 population. There Hlbariier survey. ** Prevalence of disease was a valuable studies and the experience gained from

is not much evidence for us to believe that this ugh times the incidence. Among cases found in the within the country and all over the world.

|initial survey 50% died within 5 years, about According to Dr. Banerjee "The findings of the

is happening in the rest of our country.

1:^20% continued to excrete bacilli after 5 years, sociological studies done at National Tuber

Without permanent and extensively spread rKnd the remaining 30% got cured spontane culosis Institute provided an entirely new

out diagnostic facilities, and notification of ously. There was no evidence of an increase in direction to the strategy for dealing with the

drug-resistance among the newly diagnosed problem of Tuberculosis in India. In the first

detected cases it is very difficult to give convincing

cases. The prevalence and incidence of infection place, as already a large number of patients

information on the incidence of Tuberculosis

showed a significant decrease during the 5 years were actively seeking treatment at various health

in our country. But some longitudinal studies

in the age groups 0-24 and 0-34, respectively. institutions, top priority was to be given in a

have been carried out in Defi^ B'Shga1 ore and

Madanapalle. The overall incidence' rate of At each survey, infection rate among the new national programme for providing services to

born, tested for the first time at the survey, also those who had a felt need (Programme ought

Tuberculosis from the studies done at Delhi

and Madanapalle, though not strictly compar showed a decline. The overall prevalence of to be a felt need oriented one). As those who

disease also decreased from the first to the 3rd had felt need sought treatment at institutions

able, was 340 and 410/100,000 . respectively.

survey, but showed a slight increase in the 4th. of general health services, Tuberculosis services

However, a"longitudinal study undertaken by

•However

this was below that found at the 1st ought to be provided as an integral component

the National Tuberculosis Institute in a rural

survey." Pamra in Delhi also found a slight of the general health services. Diagnosis and

population of South India found annual inci

dence rate for Tuberculosis as around .100/ •• decline in the prevalence of Tuberculosis in treatment of about 52% of infectious Tuber

100,000. population

It must however, be ,'jthc city area. This area however had a good culosis who were worried enough to seek

pointed out that whereas Bangalore rate was Ajpnd comprehensive anti-TB service. Frimodt- treatment on their own initiative would require

reported the decline in disease in six"?

based on fresh bacillary cascs_.only, the fwMoller

I^turns with a good tuberculosis service to~~be very great effort. Logistically it implied an administrativc effort to cxaminc_the_ sputa of as

Delhi, Madanapalle rates were in respect of

all cases judged as active, including abacillary i^jnot different significantly from the decline in as many as 30 mifiion cases of _chronLc_cough

cases. In any case one has to admit that an hS’the'ot hefsix control Towns without anyjpecia| who were reporting at over l_2jjOO.Jnpw_it is

service (Fimodt:Mollers 1981^

important information such as attack rate of /^tuberculosis

WjThcse'findihgs of Bangalore, Delhi aniTMadana^ about -20;000)7heaith institutions scattered all

Tuberculosis applicable to our country as a

over the country to identify about a million of

pallc

together

with the characteristic of Chronic infectious patients. Bangalore study revealed

whole is woefullyJacking.

• :Pulmonary Tuberculosis now increasingly seen that as many as 90%' of the patients _who visited

Regarding the trend of Tuberculosis in India, A in the country, the shift in the age group in which the different health institutions did not get any

Imore and more cases of tuberculosis arc seen facility-even to* get diagnosed as cases of Tuber

we have no statistical data applicable to the

country. That means we really do not know S — all indicate the declining trend of tuberculosis culosis and were sent back mostly with a bottle

how the Tuberculosis situation in our country !j in our country, however small it is. This, no of cough mixture."

has responded to three decades of BCG vaccina i| -doubt, is an encouraging feature of the Tubcrtion programme and the National TB Control •^culosis situation in India. Concerted action

In view of the sociological studies made by

Programme in operation for

o... and half & taken now will help us to bring down our Tubcr- the National Tuberculosis Institute, our National

A

culosis

situation.

Tuberculosis Control Programme is sociologi

decades. Therefore, opii..uiis are varied. Accord

ing to Dr. Nagpaul (1978) “there arc reasons to

cally oriented and is an attempt to meet a felt

believe that India had more than one epidemic

need. It is also cpidemiologically aimed in order

Tuberculosis Control Activities in India

of Tuberculosis since the time of yore. The

to cut the transmission of infection. Another

present epidemic might have started in the 17th

The National Tuberculosis Sample Survey good thing about our National Tuberculosis

century. There is evidence that the present

revealed the urgent need for a nation-wide TB control programme is that it is operationally

epidemic has been declining since the turn of the

Control Programme in our country. The new flexible, or it has a flexibility that will allow for

20th century. The natural decline at present

nt situation. The number of new tuberculosis cases

•‘Prevention trial in Chinglcput showed a dil

is very slow, probably because of the prevailing

in that population. The disease in the infected group

developing from the initially uninfected was particularly

poverty, malnutrition and over crowding The

District Tuberculosis programme, even at the y was 17 time morc-a really peculiar and noteworthy phenomenon.

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

■j

83

TUBERCULOSIS IN 1ND1A-THB PROSPECT

8i

5. SVaXAMAN

local, sociological, administrative, operational

and other variations.

Our National Control Programme is defined

as “an organised effort wihich aims to bring

under control the problem of Tuberculosis in

the community through defined objectives,

activities and resources. It comprises of wellknown anti-TB measures knit into a compre

hensive, practical, acceptable and economically

feasible programme.'’

The objective is to reduce Tuberculosis in

our country sufficiently quickly to the level where

it ceases to be a public health problem.

The operational objectives laid down are:

Table. 1

Health Services, New Delhi shows that out of

400 districts in our country’, there are only 320

districts with TB control programmes which

means that l/5th of the districts in India arc

without a programme. In an average Indian

district there arc about 50 implementable peri

pheral health institutions. The report shows

that the programme has been implemented on

an average only in 33 peripheral institutions. It

would appear from the report that about 34 %

of the peripheral health institutions in the

country are without a programme in the already

established District TB control programmes^

Thus, on the whole about 47% of the country i

cven_LQda.y-is-nol-covcred by the-TB-control]

programmes. This geographical coverage 1T*

reported as fairly satisfactory. I beg to differ

and say that this is rather unsatisfactory.

“To vaccinate with BCG a majority

of the eligible (if possible more than

Average case detection performance of a

70%) in the community, in an efficient District Tuberculosis Control Programme in

manner.

our country can be judged from the quarterly

reports issued from the Directrate General of

(2) To detect maximum number of TB Health Services. According to the report for

patients with symptoms from among the the period ending December 1980, a total of

out patients attending Health institu 1,23,353 cases of Tuberculosis werc’diagnosed

tions and to treat them adequately; in through the reporting District TB Centres.

doing so, to give priority to sputum Of these 10,293 were cases of cxtrapulmonary

positive TB patients.

Tuberculosis.

N.T.P. (INDIA)-Case Detection in an Average Quarter

D.T.Cs.

CASES DEIKTCD

TOTAL

P.H.Is.

123,355

All types

91.645(66-2) 41.708(530)

Pulmonary '

Tuberculosis •

(bacillary)

19,203(641) 10)800(359) 30.083(243)

Pulmonary

Tuberculosis

:

54.034(651) 29,143(34-9) 83.177(675)

;

(abacillary)

;■

Extra Pulmonary

Tuberculosis

8,328(825)

1,765(175)

10,095(82)

Figures in brackets sho* percentage value

(I)

To undertake the above, activities from

all health institutions, as an integral Table I

part of the general health services”.

Table shows average case detection perfor

It is not only the Government medical insti mance in our N.T.P. in a quarter (quarter ending

tutions wherein the control activities are to be December 1980). Of the cases detected 8.2%

organised. Private medical institutions and were cxtrapulmonary tuberculosis and the re

practitioners should be involved in aUJhc_act£ maining were pulmonary tuberculosis. Bacillary j

vitics in the manner posiblc. A District T.B. cases of pulmonary tuberculosis constituted

Centre, OriS fUr eveiy districr, located at the 24.3% of the total :and abacillary pulmonary

district headquarters is to form the nucleus of tuberculosis cases formed the balance 67.5%.

the District TB Control Programme. According

When we look at the performance of D.T.Cs j

to Dr. Nagpaul, "applying the National

Sample Survey findings to the average Indian and P H.Is in our N.T.P., we sec that the P.H.Is ,

district, it was estimated that there would be contribute only 33.8% of all cases detected. The I

5000 infectious Tuberculosis p.irienfy

3-4 bulk of cases arc even today detected in the

times that number with X-ray shadow suggestive D.T.C.s Another interesting observation is that

of the diseaseTnit sputum "negative, to be dealt even in the P.H.Is cases of Pulmonary tubercu

with at any time. This pool of ‘cases’ and ‘X- losis detected are largely abacillary and not

n direct

ray suspects’ constitute the problem of Tubercu bacillary which means that

losis in a district Programme performance sputum microscopy, our literal medical institu

potential studies have shown that District TB tions arc relying on other methods including

Control Programme-is-capable of discovering X-ray examination for case detection. There

in on^^i_46%^onhc entire.pQoLQLinfectiQiis fore, we can conclude that the case detection in

P.H.Is on the whole is poor and the outlook is

cases in the district.’’

not one of detection of infectious cases of

pulmonary tuberculosis by sputum examination.

Our National Tuberculosis Programme Today

This only means that the very philosophy of our

Quarterly progress report of the District N.T.P. has not been understood/appreciated by

TB Control Programmes for the period ending persons working in the general health institu

1980 issued from the Directorate General of tions. -•/

(3)

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

I] It is rather difficult to get figures of T.B,

Btients detected each year in our country. On

to average about 5-6 lakhs patients of all forms

fre detected through reporting D.T.Ps. (All

S.T.Ps do not send reports and some reports

re incomplete). If we guess that an equal

umber of patients are also detected in our

ounlry from institutions not covered by D.T.Ps.

ossibly 10-12 lakhs patients are detected each_

'ear. This means that only 10-15% of the total

f.B. patients (if the total tuberculosis prevapnee i¥~E2'%rarc~detcctcd ~cach-ycar-in-fndia.

• About case holding, particularly successful

rcatment completion by patients, information

? not available in the quarterly reports. However

iccording to Dr. Nagpaul’s estimate about

|5% of detected patients arc cither cured or

jccamc sputum negative in a period of one year

n an area covered by D T P.

As regards BCG vaccination coverage, we

fave no data. Moreover the ‘indirect protective

iction’ of BCG has been reported as zero by the

yfadras study.

Spidomiological Model

As the evolution of Tuberculosis starting

irom infection—disease—recovery or death is

iow better known, one can prepare an cpidcniological model for tuberculosis in a commulity or country. A simple model prepared by

Jr. Azuma (Japan) which is a modification of

Vaalcr's model is Shown-iirFiprVH:----------This model subdivides a given population

into six groups. Numerical values of these

{roups arc called ‘variables’. Variables vary

vith time and are therefore not constant.

SIMPLE EPIDEMETRIC MODEL

OF TUBERCULOSIS

(modified from Waaler’s model)

newborn

Infected

s 5 years

'1 ^°rn F H

z| infected

years

—Ji >5Infected

'

|

BCGt . t

protected j

Bacilli

Deaths

Cured

Fig- 7

Numerical values for the flow between variables

are called “parameters”. Birth-rate, Infectionratc, BCG vaccination coverage, protective

effect of BCG, case rates (annual incidence

of the disease) death-rate, (crude and cause

specific) and cure rate with or without a pro

gramme are some of the parameters for the

above model. If initial values of variables are

known, and values of parameters are available.

the dynamics of tuberculosis in a community

becomes clear. Such a model approach is

particularly useful in India for predicting the

trend of tuberculosis. As reliable values for

most of the parameters arc not available for

our country, determination of the future trend

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

«4

S. SIVARAMAN

of tuberculosis becomes difficult. However, Dr.

Nagpaul worked out the trend of tuberculosis

problems in our country using a very simple

model.

According to him, the District Tuberculosis

Programme, even at the present level of efficiency,

has a potential of accelerating the natural

decline of tuberculosis in India. He very roughly

calculated that without other epidemiological

‘flows’ there would be 4.8% annual decrease in

our problem over and above the natural decline.

Table 2

Estimated Sputum Positive Cates in Average Indian

District with & without District Tuberculosis programme

at the end of one year

| fate of prevalence cases during one year

i

1

Dead I Cured [Aiaihr'M ,Cases Nc.of

(sputum 1 (Sputum 1 (sputum 1 added Cares

necathe) negative), positive) (inci- at tt

(Preva

lence)

Without pMcrw *>5000

(natural time-freed

700

1000

5500

With programme 4.224

diagnosed

590

B15

2789'

Diagnosed

776

Total

5.000

1700

5.000

1.700

4.761

272 \

737 1 1.202

5.061

Reproduced from "Tuberculosis in India" by Dr.

Nagpaul Journal of the Indian Medical Association

In the estimate of Dr. Nagpaul, expected

reduction in the prevalence in an area without a

programme due to death occurring in the

patients was at the rate of 14% a year. This was

the crude death rate for the country. The same

rate was applied for patients not diagnosed in

an area with a programme. However, a rate of

19% was applied in calculating reduction by

death in the group of patients detected in the

programme area. This appears to be some

what unlikely. If the rate of 14% was also

applied to the group of detected patients in the

programme, the estimated problem reduction

would be 4% instead of 4.8%.

Earlier, 1 worked out that our N.T.P. has

achieved onlv about 50% geographical coverage.

Therefore with the type of programme that we

now have, the annual problem reduction, will

be around 2%. If the programme docs not

change in coverage and efficiency and the general

conditions of living standard remain static.

by 2000 AD our problem will be that of 5.3

million cases of Pulmonary Tuberculosis.

TUBERCULOSIS IN JNDIA'THE PROSPECT

Fig. vm

*3 3

If the rate of growlh of population noticed

during the last two decades is to continue for the

coming two more decades, our population would

touch 1000 million mark by 2000 A.D. With

all our efforts in family planning programme,

the decade growth rate of population in India

was 24.80 for 1961-71 and 24.75 for 71-81. If

this unfortunate thing continues, the prevalence

of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by 2000 AD would

be 0.5% and 0.12% for total problem and pre

valence of infectious cases respectively. To

arrive at the above figures, the problem of

Tuberculosis in India in 1980 was arbitrarily

considered as the one found by. Dr. Pamra for

Delhi area in his 5th survey (1972-7.3), i.e.2.8/

TUOO (Bariliary cases) and~12>T000 (Total'active

cases). This was accepted for calculation 'pTTrposes as the all India prevalence rate since no

other reliable figures were available. Prevalence

for 1973 in Delhi where active anti-TB measures

were in operation could justifiably be ..pplied

as the near true all India t -valence rate for the

year 1980. All these approximations have been

made to have an idea of the possible effect of the

programme in our country.

ESTIMATED TUBERCULOSIS PREVALENCE IN INDIA

FOR THE PERIOD FROM 1900 TO 2000A D.

It would thus appear that Tuberculosis will

have a slow downward trend in the next two

decades to come and tuberculosis may continue

as a major public health problem for many

years. I am not trying to say that the problem

cannot be tackled in a period oC20-30 years. athat a T.B. Control Law, if enacted, could help produce the desired impact on the growth of

If Japan could lower their problem considerably ■>sus in fixing standards for case detection, case our population, the same might get repeated

during the past three decades, wc could also ..^holding, classification or various forms of in the Primary Health Care Programme. Such

achieve it provided wc work together to create a ^disease,

an eventuality should not occur.

•'jjUliUdbL,, iiUUllllHIUll

notification Ul

of IIIVIVIViiv;

morbidity & n.«.

mortality

.......

favourable situation.

j-'|ctc

[etc. Such a T.B. Control Law will ensure better

Before 1 conclude, a word about the Father

.'•^participation by individuals and institutions and

If our national Tuberculosis Control Pro W.nlso create an awareness of the problem and of French Phthisiology and former Secretary

gramme docs not function properly, it is not ds,programme in the minds of the lay public. Any General of the International Union against

due to any inherent defect in the programme.

[developmental activity, and no doubt a pro- Tuberculosis. Professor Etinnic Bernard. In a

On the contrary it is the poor coverage, and

l.grammc like Tuberculosis control needs the tribute to this great man who passed away on

operational and managerial problems that arc .•;d knowledgeable cooperation of many for its the 6th June, 1980, the Bulletin of the Inter

responsible for the poor performance. As our • •1 success. T.B. Control Law if enacted would be a national Union in its December, 1980 number

learned President once said it is in short due to ,3’short cut in achieving such cooperation. It is published his short life sketch. I wish to quote a

human failure that the programme docs not is® also unlikely to interpret such an enactment as few lines from this memorial. "Some morning,

function properly, a human failure in which wc

when I left the Hospital, I wanted to shout at

undemocratic.

all have contributed. It is upto us to decide

those who passed by and seemed so indifferent.

what we should do to control our Tuberculosis

The much talked of "Health for all by 2000 It couldn’t go on like that, and one morning I

problem. It is again upto us to din into the cars

AD” and “Primary Health Care" which is had the conviction—not the evangelical convic

of our decision makers the seriousness of our

s,ralc?y f°r achieving the above concept tion of the Christian, but a conxiRlifln, nonTuberculosis situation and what is to be done

has been accepted in India. A well thought thelcss, that the struggle against the scourge

in the matter. There is very little justification

out and planned Primary Health Care, properly of Tuberculosis would hehceforth~Fc_my voca

in not having a countrywide programme. By a j® established, will go a long way in carrying out tion. This conviction has never left me in more

countrywide programme, I mean a programme

a our TB control programme most successfully. ’ than forty years.” This was what he used to feel

in which every medical practitioner and insti

T However, wc have to take lessons from our in the early days of his career as head of a

tution in our country discharge their duties in

® Family Planning and National TB Control hospital department treating Tuberculosis in

the matter of controlling this malady. If suitable -j Programme. If like the Family Planning Pro- women, and what he did thereafter. Wc in our

legislation is to be enacted, it is again upto us to 75 gramme into which a sizeable amount of our country will have to shout at our fellow men

advise our decision makers. I have often felt

3 scarce resources have been pumped did not in the medical profession and tell them that

i

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 2

•i

j

-

-86

5. SIVARAMAN

we can no longer be indifferent to our Tuber

culosis situation. Jointly we may .then. shput

to the decision makers and tell them what is

to~be--done.--------- —----

13.

International Union Against Tuberculosis, Tuber

culosis: Japan, At the Cross Roads No. 31, 1973,

P. 4.

14.

Krishnuswami, K.V.,; Supplement to Indian Journal

of Tuberculosis; 1975, 22.

15.

Lowcl, A.M., Tuberculosis in the World, U.S

Department of Health, Education And Welfare.

Atlanta, 1975.

16.

Nagpaul, D.R.; Journal of Indian Medical Asso

ciation, 1978, 71, 44-48.

I.

Azuma, Y. Tuberculosis control. Research Institute 17.

of Tuberculosis, 1979, P. 68.

Nambiar, M.V.U.; Census of India 1981 Series 10,

Paper 1 of 1981.

2.

Bancrji, D., Social aspects of Tuberculosis in India, 18.

Text Book of Tuberculosis, 1981, P 528.

Pamra, S.P.; Clinics in Chest Medicine, 1980, 1,

265.

Before 1 finish, let me thank all of you for

listening to me so patiently. 1 take this oppor

tunity to thank the House of Wanders for the

keen interest they show in the activities of TB

control in India and particularly for instituting

the Wander TAI Oration.

REFERENCES

3.

Bulla, A., WHO Chronicle; 1977, 31, 279.

4.

Chakraborty, A.K., Gothi, G.D. ct al, Indian

Journal of Tuberculosis, 1978, 25, 86,

5.

Coudrcau. H., Bulletin of the International Union

Against Tuberculosis; 1980, 55, 83.

6.

District Tuberculosis Programme, National Tuber

culosis Institute, 1977.

7.

Farga, V., Bulletin of the International Union

Against Tuberculosis, 1978, 53, 3.

8.

Frimodt-Mollcr, J., Bull. WHO, 1960, 22, 61.

jmirimodt-MoIlcr, J.; Ind. J. Med. Res; 1981, 73

(Suppl.) April 1981, P. 63.

10.

19.

1980.

20.

Rai Narain, ct al; Bull. World Health Organisation,

1974, 51.

I

21.

Styblo, K., Mcijcr, J.: Bulletin of the International iUnion Against Tuberculosis 1978, 53, 283-293. ’J

22.

Styblo, K., Bulletin of the Interna lion? 1 Union g

Against Tuberculosis, No. 3, 1978, 53, 141-152. |

23.

Tuberculosis Prevention Trial,

Res. 1979, 70, 361.

24.

Tuberculosis Survey in England and Wales 1971,

tubercle; 1973, 54. 249.

Gothi, G D., ct al, Indian Journal of Tuberculosis,

25.

1979, 26. 121-133.

11.

Gothi, G.D., ct al, Supplement to the Indian Journal

of Tuberculosis; 1978, 25, 8,

12.

Hitze, K , Bulletin of the International Union

Against Tuberculosis; 1980, 55, 13.

26.

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No, 2

Quarterly Progress Report, Directorate General

of Health Services, quarter ending December. $

Indian J.

Med.

Tuberculosis in a rural population of South India.

a five year epidemiological study, Bull. World

Health Organ.; 1974, 51. 473-488.

World Health Organisation, Expert Committee on

Tuberculosis- Ninth Report, W.H.O., Tech. Rep.

Scr. No. 552, 1974.

Position: 3092 (2 views)