MEASUREMENT AND EVIDENCE KNOWLEDGE NETWORK.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

1

/FvjfiEnJcer

^SORbNE^r

KrJDbOt-^^fr^

Aj£T^>C>^y<

£

1

c O^ae

(9rJ

D£-TERH/M>6a//S

ibCQlr^ e>AA\i~jV_.

CS-bH

I

2x>q^

y

9

/

‘

*

>

■

Page 1 of 1

Community Health Cell

From:

To:

Cc:

Sent:

Attach:

Subject:

"Josiane Bonnefoy" <josiane.bonnefoy@gmail.com >

"Thelma Narayan" <chc@sochara.org>

"Liliana Jadue" <ljadue@udd.cl>; "Francisca Florenzano" <fflorenz@gmail com>- "Mike Kelly"

<Mike.Kelly@nice.org.uk>; "Antony Morgan" <Antony.Morgan@nice orq uk>

Friday, March 31, 2006 5:44 AM

Arrangements for M&E KN Meeting at Santiago.doc; Measurement and Evidence Knowledge

Network.xls; Agenda Draft 31thMarch.pdf; Paper 1 - Methodology Paper 040206.pdf; Paper 2

CSDH - Conceptual framework.pdf; Paper 3 - Consultation on Measurement - Report of

Proceedings.pdf

M&E KN First Meeting Santiago 2006 - Dr. Narayan

Dear Thelma,

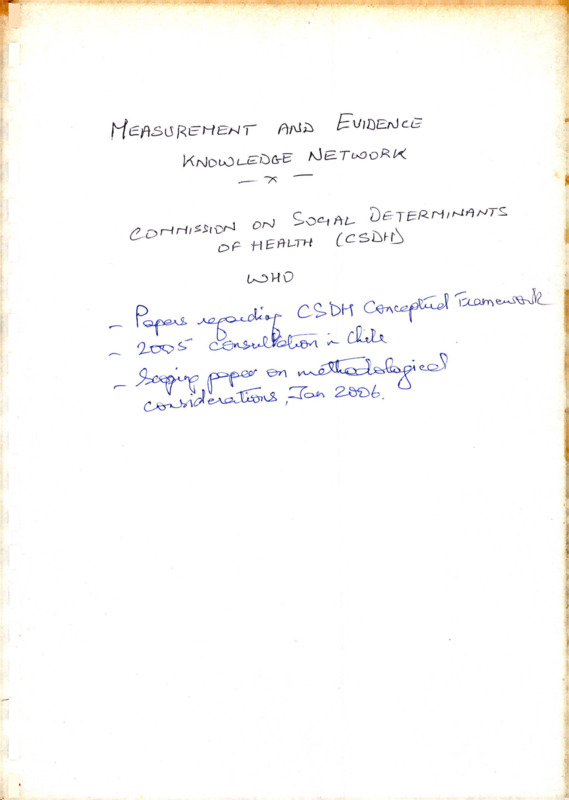

Please find enclosed information for our First Meeting of the Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network.

We are attaching the following documents for your information:

1. Arrangements for M&E KN Meeting at Santiago

2. Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network:

3. Agenda Draft 31thMarch

We are enclosing the following essential reading for the meeting:

Paper 1 - Methodology Paper 040206

Paper 2 - CSDH - Conceptual framework

Paper 3 - Consultation on Measurement - Report of Proceedings

I would appreciate if you could confirm the reception of this mail.

If you would like any further information, please do not hesitate to contact me,

Looking forward to meeting you, I wish a nice and safe trip.

Best regards,

Josiane Bonnefoy

3/31/2006

MEASUREMENT AND EVIDENCE KNOWLEDGE NETWORK

FIRST MEETING

1 • Flight arrangements

Following consultation with all you, itineraries have been agreed and tickets have

been forwarded to you. Please note that once you receive your tickets, the cost of any

changes made to these flights will be at your own expense.

Visa, travel insurance and other travel-related costs

You are responsible for obtaining your own visas for Chile and countries in transit,

wherever required. On arrival in Chile, we will reimburse you for the cost of visas and

any airport taxes on receipt of invoices only. Please bring these invoices with you.

Please note that weecannot •be •held

- - responsible for any costs associated with travelrelated problems, including health problems, experienced during the; course of the

meeting.

3. Meals and accomodation

The Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network will cover the costs of each

participant’s accommodation, meals and transport from and to the airport.

Accommodation is booked until the date of the agreed return flight and meals will be

provided for the same period.

4. Airport pick-ups

On the basis of the agreed flight times, we will make arrangements for you to be

picked up at the airport on arrival. Please look for a representative of Transvip

standing outside the gates immediately after you clear Customs, in the arrival hall. If

you do not see the person who will be waiting for you, please approach the Transvip

counter. You may have to wait a short while for other participants to arrive on

different flights.

Please do not use other means of transport since it is already booked for you. This

means that you do not have to pay for the service because we have already taken care

of it. We will also arrange transport for you back to the airport after the meeting.

5. Accommodation arrangements

The meeting will be held at the InterContinental Santiago Hotel, with contact details

as below:

Hotel InterContinental Santiago

Av. Vitacura #2885 Las Condes

Santiago CHILE

Tel: (562) 394 2000 | Fax (562) 394 2075

http://www.intercontisantiago.com/

1

Upon arrival please inform at the reception desk that you are part of the group booked

by the Universidad del Desarrollo for the Measurement and Evidence Knowledge

Network Meeting.

6. Climate

At present we are in autumn, with decreasing temperatures, at the moment ranging

during the day between 8° and 24° Celcius.

7. Health precautions

No specific health precautions are necessary for Santiago.

8. Currency

At the moment, 1 US Dollar is equivalent approximately to $ 520 (Chilean pesos) and

1 Euro to $ 625 (Chilean pesos).

If you are bringing dollar notes, please take into account that USD 100 notes

beginning the series with AB and CB (years 1996 and 2001) are not accepted.

Nearly all credit cards are accepted. The most commonly used are: Visa, MasterCard,

Dinners and American Express. ATM machines accept Plus and Cirrus. You will find

them at the airport if you need to have some cash immediately.

We very much look forward to seeing you.

(iosiane.bonnefoY@gmail.com)

or

my

colleague

(fflorenz@gmail.com ) with any queries.

Please contact myself

Francisca

Florenzano

Our phone numbers at the University are:

Josiane Bonnefoy

+56 (2) 299 9423

Francisca Florenzano

+ 56 (2) 299 9305

Liliana Jadue

+56 (2) 299 9423

Fancy Fredes (Secretary) : +56 (2) 299 9423.

Only in case of emergency:

Josiane Bonnefoy :

Francisca Florenzano:

Home: +56 (2) 273 5626

Mobil: 09-2247800

Upon arrival to the hotel you will receive information on who will be at the venue to

contact you.

We wish you a nice and safe trip to Santiago.

Best regards,

Josiane Bonnefoy

2

World Health Organization

Commission of Social Determinants of Health

Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network Members

i/

______ • Name

Dr Francisco Espejo

Country

Chile

________ E-mail address

Francisco.Espeio@wfp.org

%• Dr Mark Exworthy

United Kingdom M.Exworthy@rhul.ac.uk

3,. Dr Gao Jun

China

gaoiun@moh.gov.cn

Institution and Postal address

Chief School Feeding Service

Strategy Policy and Programs Division

Policy and External Affairs Department

UN World Food Program

Via CG Viola 68

Parco dei Medici

00148 Rome

Italy

______ TelePhone:

Phone:+39 06 6513 2064

Fax:+39 06 65132854

School of Management

Royal Holloway

University of London

Egham

Surrey TW20 OEX

United Kingdom_________________

Deputy Director,

Center for Health Statistics Information,

Ministry of Health,

1 Nalu Xizhimenwai

Xicheng District,

Beijing, 100044,

China

Phone:+ 44

Fax: + 44

Phone: + 86

Fax:+ 86

_________ Name

4. Dr Ichiro Kawachi

Country

Japan

S' . Prof. Johan Mackenbach

The Netherlands l.mackenbachffierasmusmc.nl

. Dr Landon Myer

South Africa

lmyer@cormack.uct.ac.za

India

chc@sochara.org

Dr Thelma Narayan

■z. Prof. Jennie Popay

_________ E-mail address

Ckawach@aol.com

United Kingdom i.popay@lancaster.ac.uk

______ Institution and Postal address

Department of Society, Human

Development and Health

Harvard University

Kresge Building

7th Floor

677 Huntington Avenue

Boston, MA 02115

USA_________________________

Department of Public Health

University Medical Center Rotterdam

Erasmus University

P.O. Box 1738

3000 DR Rotterdam

The Netherlands

School of Public Health and Family

Medicine,

University of Cape Town,

Anzio Road,

Observatory 7925,

Cape Town

South Africa______________________

Coordinator

Community Health Cell

# 367, Srinivasa Nilaya,

1 st Main, Jakkasandra,

1st Block Koramangala,

Bangalore - 560 034

India

Professor of Sociology & Public Health

Institute for Health Research

Lancaster University

Lancaster LA 1 4YT

UK

_______ TelePhone:

Phone:+1 (617)432 0235

Fax+1 (617)432 3123

Phone: + 31

Fax: + 31

Phone:+ 27 (21)406 6661

Fax:+27 (21)406 6764

Phone: + 91 (80) 255 31518

Telefax: + 91 (80) 255 25372

Phone: + 44 (0) 1524 592493

Fax:+ 44 (0) 7734058761

________ Name

Dr Peter Tugwell

Country

Canada

_ ______ E-mail address

elacasseffiuottawa.ca

Institution and Postal address

Canada Research Chair in Health Equity

Director,

Centre for Global Health

University of Ottawa

Institute of Population Health

1 Stewart St.

Room 202

Ottawa, Ontario KIN 6N5

Canada

[C>.

a

UK-

____ TelePhone:

Phone:+1 (613) 562 5800 ext

1945

Fax:+1 (613)562 5659

World Health Organization

Universidad del Desarrollo

National Institute for Health

and Clinical Excellence

Commission on Social Determinants of Health

Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network First Meeting

Santiago, Chile: April 6th - 8th, 2006

Hotel InterContinental Santiago

Avda. Vitacura 2885, Las Condes

Santiago, Chile

Agenda

Draft

Objectives of the Meeting:

I. To launch the Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network, and provide a

face to face discussion, reflection and proposal on the Network’s subject, tasks

and key deliverables.

2. To agree -the key principles that will steer M&E KN’s work, so as to

provide guidance to the work carried out by the Commission’s main streams:

civil society, country work and knowledge networks.

3. To present and discuss applied experiences of evaluation at different levels:

civil society, country and international cooperation agenciesTofboth upstream

and downstream interventions.

4. To agree M&E KN’s working organisation and methodology, distribution of

responsibilities, links with different CSDH’s components, use of SharePoint,

and timeframe of KN’s activities.

5. To agree on a framework for the collection, appraisal and synthesis of

evidence across knowledge networks.

6. To identify the necessary pieces of work and the main themes for position

papers and how these will be commissioned by the M&E KN.

7. To suggest date and topics to be dealt with in the Second M&E KN Meeting.

Expected outcomes of the meeting:

1. Shared understanding of M&E KN’s role, responsibilities, tasks and key

deliverables.

2. Definition of M&E KN’s working methodology and timeframe.

3. Clarity on individual members’ responsibilities.

4. Preliminary inventory of experiences of evaluation of interventions on social

determinants of health equity known by members.

5. Agreement on necessary pieces of work and on main themes for position

papers and how these will be commissioned.

6.

Proposal of date for Second M&E KN Meeting and highlights of subjects.

Thursday 6th April

19:30

Dinner

Welcome address from representatives of:

Ministry of Health

HDD, Dr Pablo Vial and Dr Liliana Jadue

NICE, Professor Mike Kelly

WHO/CSDH, Ms Sarah Simpson

Introduction of Knowledge Network members and invited observers.

Friday 7th April

9:00 - 13:00 First session: The Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network

Chair: Jeanette Vega

Rapporteur: Francisca Florenzano

Objectives:

1. To introduce the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, and the

organisational context in which the M&E KN will work.

2. To present the Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network: its

background, purpose, special characteristics (cross-cut), tasks and key

deliverables.

3.

fo examine members representation in the network and to agree on how to

deal with potential gaps in representation.

4. To agree on the meeting’s working methodology and expected outcomes.

5. To introduce the preparatory work and the key principles guiding the KN’s

work.

2

9:00 - 9:30 Introduction

Dr Josiane Bonnefoy & Professor Mike Kelly

•

Objectives of Meeting

•

Expected outcomes of Meeting

•

Structure of agenda.

9:30-10:30

Commission on Social Determinants of Health

Ms Sarah Simpson, Secretariat, WHO Geneva & Ms Tanja Houweling

Secretariat, UCL London.

•

•

Social Determinants of Health and WHO’s position on the subject.

Conceptual framework of the Commission on Social Determinants

of Health.

•

CSDH Components: Commissioners, Knowledge Networks,

Country Work, Civil Society, Secretariat and linkages.

Knowledge Networks: Themes.

•

(20’ presentation and 40’ discussion)

10:30-11:00 Break

11:00-12:00 Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network Update on work to date

Dr Josiane Bonnefoy

•

M&E KN Hub History:

(a) Measurement Consultation meeting, Santiago, March

2005 - main themes and conclusions

First meeting of Knowledge Network hubs, Ahemedabad,

India, September 2005Fourth meeting of Commissioners,

Teheran, Islamic Republic of Iran, January 2006.

(b) Work with other knowledge networks to date.

4

•

M&E KN Members:

(a) Preliminary composition of network - criteria, potential

gaps, etc.

(b) Terms of reference: hub, network members and virtual

members.

(c) Expected outcomes.

(20’ presentation and 40’ discussion)

12:00-13:00 M&E KN Scoping Paper

Professor Mike Kelly

3

•

•

Presentation (30 mins)

Discussion (30 mins) - (key issues arising, noted for later

discussion of key issues)

13:00-14:00 Lunch

14:00-18:30 Second session: Measurement and Evidence: developing a shared

perspective and approach

Chair: Sarah Simpson

Rapporteur: Antony Morgan

Objectives:

1. To present the conclusions arrived at the Santiago Consultation,

March 2005, in order to state from where are we taking a step

forward.

2. To identify the key issues for the..Network to consider in gathering

and synthesizing evidence on:

(a) methods for evaluating action on the social determinants

of health (given absence often of RCTs).

(b) equity/inequality measurement tools for setting targets

and monitoring and evaluating - these could be

integrated into health information systems e.g.

household surveys etc.

1. Presentations:

• Introduction and outline of session (5-10 mins)

• Brief presentation of main conclusions of the Santiago

Consultation, March 2005 on evaluation methodologies.

Ms Francisca Florenzano (20 mins).

• Example of a concrete evaluation of intervention carried out by

NICE, to identify the challenges. Mr Antony Morgan (20 mins).

2. Discussion and identification of key issues.

Saturday 8th April

8:30-13:00:

Third session: Developing a framework for the collection,

appraisal and synthesis of evidence: working with knowledge

networks and developing our future guidance

Chair: Josiane Bonnefoy

Rapporteurs: Sharon Friel and Tanya Houweling

4

» 'vO

c-

Objectives:

1. To agree on how are we going to collect, collate and synthesise the

network’s own evidence on evaluation methodologies and

experiences.

2. To agree on the recommendations to Knowledge Networks on how

to collect, collate and synthesise their networks’ evidence.

8.30-9.15

Summary key points from day 1 discussions

Professor Mike Kelly

9.15-10.30

Two working groups focussing on

•

•

•

•

•

What type of evidence is needed to support sound recommendations

and what are the methodological implications?

How to incorporate evidence coming from different sources, i.e.,

civil society, country and international levels.

What criteria to discern whether small-scale interventions or

experiences can be scaled up to the macro level?

How to develop attributable fractions analysis of interventions.

What approaches and methods will be used to gather evidence?

NB there may be other questions to consider in addition to these

10.45-11.15 Working group report back.

11.15- 13.00 Discussion, summary and next steps

Group 1: Rapporteur: Sharon Friel:

Group 2: Rapporteur: Tanya Houwling

13:00- 14:00 Lunch

14:00-18:30 Fourth session: Key foci and activities for MEKN

Chair: Mike Kelly

Rapporteur: Josiane Bonnefoy

Objectives:

To finalise key issues to be considered by Network

To determine priority activities for network

To identify main pieces of work to be commissioned by network

To identify links with other CSDH streams of work (country work

and civil society process)

5. To agree on roles of network members in relation to work

prioritised

6. To agree on network members’ terms of reference.

7. To clarify process, mechanisms and timing of future

communication among network members

1.

2.

3.

4.

5

T

J cJLa.J

v.0

8. To identify other people or experiences that could be drawn on in

undertaking work

9. To identify date and activities for second network meeting (subject

to discussion with missing members)

10. To finalise overall timeplan for network activities

Discussion:

•

•

•

•

20:00

Agreed outcomes from meeting and key issues

(a) Scope of the work and priority activities

(b) Potential gaps, challenges and ways forward with MEKN

approach

Linking to other streams of CSDH work

Other KN planning

(a) Roles of network members

(b) Share Point and communication among network

(c) Second meeting date and purpose

(d) Overall timeplan

Summary and conclusion.

Dinner.

6

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION

COMMISSION ON THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF

HEALTH

MEASUREMENT AND EVIDENCE KNOWLEDGE

NETWORK

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS RELATING TO THE

DEVELOPMENT OF THE EVIDENCE BASE ON THE SOCIAL

DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH: SCOPING PAPER ORIGINALLY

PREPARED FOR THE WHO COMMISSIONERS’ MEETING TEHRAN, IRAN

JANUARY 2006

Michael P Kelly, Josiane Bonnefoy, Antony Morgan, Francisca

Florenzano

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (UK) and

the Universidad del Desarrollo (UDD) (CHILE)

Draft 2 February 4th 2006

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS RELATING TO THE

DEVELOPMENT OF THE EVIDENCE BASE ON THE SOCIAL

DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Draft 2 February 4th 2006

2

1. Introduction

1.1. Commission on the Social Determinants of Health

A

{

In 2005, the Director General of the WHO set up a global Commission on the Social '

Determinants of Health (CSDH). The Commission’s mission consisted of four

elements:

1. learning: the consolidation, dissemination and promotion of knowledge that

demonstrated the imperative and necessity for action on the social

(J

A

determinants of health and informed policy and effective, equitable

interventions on the social determinants;

u

2. advocacy: the identification and promotion of opportunities for action on the

key social determinants for policy makers, implementing agencies and the

wider society;

3. action: the speeding up and supporting of processes that initiated, informed

(j

and strengthened actions to integrate knowledge about social determinants

within public health policy and practice; and

i

6

4. leadership: the support, enhancement and development of the public,

political, technical and institutional leaders to help them inform, advocate and

deliver the desired change in understanding and action.

The overarching objective of the Commission was to lever policy change by learning

from existing knowledge about the social determinants of health (SDH) and turning

j

that learning into actionable global and national agendas. As part of the learning

element, a number of Knowledge Networks (KNs) were established to synthesize

knowledge. This knowledge would inform the Commission about opportunities for '

improved action on SDH by fostering the leadership, policy, action and advocacy

needed to create change.

The purpose of the Knowledge Networks was to organize knowledge:

•

on priority associations between the social determinants of health and

health inequities across different country contexts with attention to

widespread cross-cutting determinants such as gender inequality;

•

on the extent to which prioritized social determinants of health in relation

to globalization can be acted upon, exemplified through successful

national and global policies, programmes and institutional arrangements;

r O’

4

*

j

•

to stimulate societal debate on the opportunities for acting on the social

determinants of health; and

•

to inform the application and evaluation of policy proposals and

programmes in relation to the social determinants of health nationally,

across regions and globally, assessing implications for both women and

men.

The themes for the KNs included: C?

•

Early Child Development

•

Health Systems

•

Urban Settings

Social Exclusion

•

Employment Conditions

Globalization

•

Women and Gender Equity

•

Measurement and Evidence •

The themes of the last two KNs were cross-cutting,^

The Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network (MEKN) will work with the

other KNs on the measurement, appraisal, evaluation and synthesis of evidence

relating to the social determinants of health. This paper outlines the principles that

will inform the approach of the MEKN.

As part of the launch of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health which

took place in Santiago in Chile in March 2005, an expert consultation for the

Measurement and Evidence KN was held. The purpose of the meeting was to begin

a consensus building process towards the development of guidelines on assessing

and evaluating programmes and policies on the social determinants of health.

Following the consultation the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

(NICE) in London, England and the Universidad del Desarrollo (UDD) from Santiago,

Chile were selected as the organizational co-hubs for the Measurement and

Evidence Knowledge Network (MEKN).

5

1.2 The social determinants of health and health inequalities

Globally there have been impressive improvements in overall indicators of health

over the last several decades. None the less, health inequalities within and between

countries persist and in many cases have widened and have continued to widen in

the recent past (WHO, 2004). This is in spite of the fact that the pursuit of equity and

the reduction in health inequalities has been a goal of some national (Graham,

2004a; 2004b) and some international policies (World Health Organization, 1981;

1985; 1998a; Ritsatakis, 2000; Braveman, et al, 1996; Braveman, 1998, United

Nations, 2000).

The first premise for the development of a methodology for working on the social

determinants of health is a statement of a value position. The explicit values

underpinning the development of the methodology is that the health inequalities that

exist within and between societies are unfair and unjust. This is not a scientifically or

rationally derived principle; it is a value position which asserts the rights to good

health of the population at large. It stands in contrast to the value position that

argues that differences in health are a consequence (albeit an unfortunate

consequence) of the beneficial effects of the maximisation of individual utility in the

market. It is important to state this at the outset that individual and collective utilities

may be at odds with the rights to health. The debate about social determinants takes

place within a sometimes explicit but usually implicit tension between the competing

claims of rights and utilities. Arguably these claims and counter claims are

irresolvable through rational discourse. In short, to uphold one person’s or group’s

rights is to interfere with some other individual or group’s utilities - and vice versa

(Macintyre, 1984). This applies in health as it does within in other spheres of human

conflict.

It is important therefore to be very clear about questions of inequality and inequity and the

values that inform the discussion. Whitehead describes health inequality as ‘measurable

differences in health experience and health outcomes between different population groups

- according to socioeconomic status, geographical area, age, disability, gender or ethnic

group’. Inequality is about objective differences between groups and individuals

measurable by mortality and morbidity. Whitehead describes ‘health inequity’ as

‘differences in opportunity for different population groups which result in for example,

6

unequal life chances, access to health services, nutritious food, adequate housing etc.

These differences may be measurable; they are also judged to be unfair and unjust

(Whitehead, 1992). Leon et al (2001) point out that health inequalities and health

inequities within countries do not mean the same thing and the related values may be

different As a consequence solutions to tackling health inequalities cannot be universally

applied to all situations and the importance of applying these solutions in context must be

noted. However, regardless of context, cultural differences and differing systems, the

position taken by the MEKN is that systematically differential patterns of health outcomes

which have their origins in social factors are unfair and unjust. The explicit value position is

that this is morally indefensible and that there is an imperative to find solutions to this state

of affairs. Moreover, because the origin is social they are the product of human agency.

Because they are the product of human agency they are potentially changeable through

human agency.

Although such human agency will operate through political, economic and biomedical

systems, they must be underpinned by an evidence based approach. And this is the

second premise - commitment to an evidence based approach. However, there are

a number of difficulties; the present paper offers some solutions to those difficulties.

The difficulties may be briefly stated. There are conceptual problems of attribution.

So it may be argued that pursuing equity in health means eliminating the social

determinants of health inequalities. These determinants are in turn systematically

associated with social disadvantage and marginalization (Braveman, 2003). The

major factors may be relatively easily delimited. The unequal distribution of the

social and economic determinants of health such as income, employment, education,

housing, and environment produce inequalities in health (Graham, 2000). However

while the general relationship between social factors and health is well established

(e.g. Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999; see also Solar & Irwin, 2005 for a review), the

relationship is not as well understood in causal terms, as it is readily observed (Shaw

et al 1999). The causal pathways of inequalities in health are empirically and

theoretically underdeveloped. Consequently the policy imperatives necessary to

reduce inequalities in health are not easily deduced from the known data.

There have been many attempts to develop policy on the basis of what is known, and

on basis of the observed relationships. The results have not been particularly

impressive, partly because the evidence base is weak - there is a very rich literature

describing health inequalities, especially in developed countries, but a dearth of good

studies explaining what can be done about it (Millward et al 2003) - and partly

7

, 0

I

, /Xj: >>( £

1

because policies which damage health and increase health inequalities have

prevailed. The evidence base is further hampered by a lack of systematic studies of

the effects of policy. The contours of inequality are not well described. The degree to

which changes in inequalities can be measured is ill defined (Killoran & Kelly, 2004).

The difference between the determinants of health and the determinants of

inequalities in health is often confused (Graham & Kelly, 2004; Graham, 2004a,

2004b, 2004c). The health of populations and the health of individuals is frequently

elided (Heller, 2005). And, finally, the link between the proximal and distal

determinants of health are poorly conceptualized and integrated into research (WHO,

2004).

In the face of these difficulties a thoroughgoing evidence based approach means

finding the best possible evidence about the social determinants (NHMRC, 1999).

The most sophisticated and technologically advanced search strategies and

systematic review procedures should be used (Glasziou et al 2004, Jackson &

Waters 2005a, 2005b) along with traditional forms of scholarship. The definition of

best evidence should be made on the basis of its fitness for purpose and on the basis

of its connectedness to research questions (Glasziou et al 2004). Those research

questions are the ones which deal with the effectiveness of interventions to-change

the social determinants. While there will be gaps in this evidence and some of it will

be more powerful than other parts. Therefore the strength of evidence alone should

no£driye the strength of policy recommendation (Harbour & Miller, 2001). Never the

less it is taken that is axiomatic that an evidence based approach offers the best

hope of tackling the inequalities that arise as a consequence of the operation of the

social determinants. The evidence will provide the basis for understanding and the

basis for action (Greenhalgh, 2001). Linking evidence based to health policy will

require the identification of appropriate and culturally sensitive mechanisms (Rawlins,

2005; Briss, 2005).

There are of course some important caveats about the evidence based approach.

There will have to be a recognition that strength of evidence alone is not sufficient as

a basis for making policy (NHMRC 1999) and that it is possible to have very good

evidence about unimportant problems and limited or poor evidence about very

important ones. Therefore a distinction must be drawn between absence of evidence,

of poor evidence and evidence of ineffectiveness. The two former are not the same

as the latter. It will need to be recognised that the links between scientific knowledge

and policy and practice are not linear and that the scientific evidence base is

8

generally imperfect in its own methodological, theoretical and empirical terms.

Consequently the connection between evidence and policy and practice inevitably

involves matters of judgements (Kelly et al 2004). This leads to a commitment to the

principle that the application of research findings to non research settings requires an

understanding of the local context and the tacit knowledge and the life worlds of

practitioners and end users. It also means that evidence hierarchies must be used

flexibly.

2 Principles

2.1 Initial Conceptual Ideas

Solar and Irwin (2005) developed a discussion paper for the CSDH ‘Towards a

conceptual framework for analysis and action on the social determinants of health’ to

set out the conceptual foundations for the work of the commission. It put forward a

framework (drawn from existing models and frameworks,) for the social determinants

of health which aimed to:

•

clarify the mechanisms by which social determinants generate health

inequities

•

show how the major determinants relate to each other

•

provide a framework for evaluating which social determinants of health are

the most important to address

•

map specific levels of intervention and policy entry points for action.

The framework also highlights 3 key issues that need to be addressed if effective

action is to be taken on the social determinants of health:

1. to distinguish between the structural (e.g. income and education) and

intermediate (e.g. living and working conditions, population behaviour, food

availability) determinants of health

2. to understand and make explicit what is meant by the socio-political context

(encompasses a broad set of structural, cultural and functional aspects of a

social system whose impact on individuals).

3. to take account of the actions that need to be taken at different levels (macro,

meso, micro) in order that inequalities in health can be tackled (i.e. to alter the

configuration of underlying social stratification, and those policies and

interventions that target intermediate health determinants).

9

The MEKN drew on these ideas to develop a set of principles for thinking about

measurement evaluation and evidence issues relating to the social determinants of

health.

2.2 Defined Principles for MEKN

■

Principle 1 Methods and epistemology

r

iSi-KSP

The data and evidence which relate to social determinants of health come from a

variety of disciplinary backgrounds and methodological traditions. The evidence

about the social determinants comprises a range of ways of knowing about the

biological, psychological, social, economic and material worlds. The disciplinary

differences arise because social history, economics, social policy, anthropology,

politics, development studies, psychology, sociology, environmental science and

epidemiology, as well as biology and medicine may all make contributions. However,

each of these has its own disciplinary paradigms, arenas of debate, agreed canons,

and particular epistemological positions. Some of the contributions of these

disciplines are highly political in tone and intent. And in spite of a great deal of

research endeavour and comment as well as practical attempts at problem solution,

there is also a great deal which is not known about the causes of inequalities in

health.

In short, although the empirical subject matter of the social determinants of health is

diverse, that diversity is given an added layer of complexity by the disciplines

involved and that those disciplines do not reach an easy consensus on the nature of

knowing the material nor its interpretation. When the ways of knowing and

understanding within the worlds of policy makers, politicians, NGOs, as well as of the

people whose lives are directly affected by the social determinants, the degree of

complexity could be potentially debilitating. As an evidence base therefore it has a

number of problems: it is drawn from a diversity of disciplines using different

methods, it is incomplete, and it is it is biased in various ways, including political and

ideological bias. This does not mean it is unusable; it means we must devise ways of

sorting out the disciplinary differences, of filling the gaps and of reducing the bias

while valuing the diversity.

It is therefore inappropriate to rule out evidence and data a priori on the basis of its

disciplinary and methodological provenance. The immediate task is to find the best

1

tv-

evidence, from whatever source it comes, defined by the extent to which it has used

an appropriate method to answer the research question. It is axiomatic that to assert

the superiority of one type of knowing over another will be unhelpful. A range of types

of knowledge and knowing will be important (Kelly, 2004; Berwick, 2005). A

pluralistic approach will therefore be necessary. The question which must be asked is

what we know, suitable for what we need to do?

The principles involved are very straightforward and have been the premise of

philosophical thought for millennia (Plato, 1974). Humans use different forms of

knowing and different forms of knowledge for different purposes. There is no

necessary hierarchy involved until we need to discriminate on the basis of fitness for

purpose. It is necessary to describe the criteria for acceptability and fitness for

purpose and this the MEKN will do. The task will involve doing this across a range of

different knowledge types. This does not mean that all knowledge and knowing in

general, or of the social determinants of health in particular, is of equal value. It

means we have to develop multiple criteria to determine fitness for purpose, to judge

thresholds of acceptability and critically appraise the knowledge on this basis.

Principle 1 therefore promotes the use of a wide range of methodologies to assess

the success of interventions and policies which aim to address the social

determinants of health. This is familiar territory. Indeed, much has been written over

the last 30 years about the most appropriate means of evaluating the work of social

and community programmes aimed at reducing health inequalities. During the 1980s,

increasing expectations within public services towards evidence-based decision

making led to a desire from those working in the field of health promotion to establish

a credible scientific basis for their work. Early attempts to summarize the evidence of

‘what works’ borrowed methodologies employed by biomedicine to systematically

review evaluations of the effectiveness of health promotion interventions.

Traditionally, a systematic review process was used to assess evaluations in terms of

their methodological merit and measures of effectiveness. To allow long-term follow

up over time, this type of evaluation requires dedicated and substantial research

resources and those with specialist evaluation expertise who can advise on

appropriate research designs and methods, implement these and conduct the

appropriate analysis. One of the biggest problems with this form of evaluation is

providing evidence of a causal link between the project being evaluated and the

outcome measures. Experimental and quasi-experimental research designs go some

11

way towards addressing this problem, although these designs are regarded by many

as a research design that is neither feasible nor desirable for community-based

interventions.

The findings from reviews of scientific studies highlight the tensions inherent in

searching for the limited amount of health promotion that has been evaluated or will

fit into the biomedical model of evidence. Some of the key questions include:

•

What counts as evidence?

•

How do certain perspectives on evidence limit the focus of our endeavours in

evaluating the impact of health promotion?

•

What kinds of explanatory models might help us to ask better questions?

•

What does this mean for indicators of outcome in evaluation studies?

These questions have been considered by a WHO Working Group (1998b), who has

put forward a set of core features for the evaluation of health promotion.

They are:

•

Participation. Each stage of evaluation should involve, in appropriate ways,

those who have a legitimate interest in the initiative. Those with an interest

can include: policy makers, community members and organizations, health

and other professionals, and local and national health agencies. It is

especially important that members of the community whose health is being

addressed be involved in evaluation.

•

Multiple methods. Evaluation should draw on a variety of disciplines and

methods.

•

Capacity building. Evaluations should enhance the capacity of individuals,

communities, organizations and governments to address important health

promotion concerns.

•

Appropriateness. Evaluations should be designed to accommodate the

complex nature of health promotion interventions and their long-term impact.

The MEKN aims to identify what types of instruments exist or need to be developed

to measure the impact of a social determinants approach to improving health, as it is

mediated through the health system. In doing so, it will promote the use of combining

methodologies and to building a strength of evidence and will avoid disciplinary wars

aiming to promote the use of the right method of evaluation to answer specific

questions.

12

1

Participants involved in the expert meeting held in Chile in 2005 to accompany the

launch of the Commission also called for the need to ensure:

•

a balance in the type of evidence drawn upon: consult systematic reviews

(such as the Cochrane and Campbell databases of relevant interventions),

but also aim to develop an 'evidence jigsaw’, including for example,

descriptions of policy-making processes (e.g. detailed case studies of

successful as well as failed policy initiatives in the area of social

determinants).

•

Different kinds of evidence are used for policymaking depending on the

question being asked. Policymakers have recommended that researchers

should help them with the task of piecing together the ‘evidence jigsaw’

(Whitehead et al. 2004). The ‘jigsaw’ would encompass different types of

evidence - for example, evidence about the potential effectiveness of policies

(from experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational studies); evidence

on the diagnosis and/or causes of problems that could contribute to the

development of appropriate interventions/programmes; evidence on costs

and cost-effectiveness.

•

The purpose for which the evidence is used should be made explicit. It is also

important to recognize that evidence is produced for different kinds of

purposes, including: mobilizing political will, purchasing "buy-in” from the

public, demonstrating success, predicting outcomes, and monitoring

progress.

The MEKN will pay particular attention to the role of qualitative research in assessing

the effectiveness of approaches to address the social determinants of health.

Professor Jennie Popay has proposed two different models to describe the ways in

which qualitative evidence contributes to the evidence base for policymaking

(Presented at the March 2005 Chile CSDH Meeting).

1) The enhancement model assumes that qualitative research adds something

“extra” to the findings of quantitative research - by generating hypotheses to

be tested, by helping to construct more sophisticated measures of social

13

phenomena, and by explaining unexpected findings generated by quantitative

research.

2) The epistemological model views qualitative evidence as making an equal

and parallel contribution to the evidence base through: (a) focusing on

questions that other approaches cannot reach; (b) increasing understanding

by adding conceptual and theoretical depth to knowledge; and (c) shifting the

balance of power between researchers and the researched (Popay

unpublished). Importantly, the epistemological model views qualitative

evidence as not necessarily complementing quantitative evidence, but / '

sometimes conflicting with it.

Qualitative research can play two key roles as part of the evidence base for the

social determinants of health: (a) providing insights into the subjectively perceived

needs of the people who are to be the targets of the interventions and programmes

aimed at addressing the social determinants of health and health inequalities (giving

people a ‘voice’); and (b) helping to unpick the ‘black box' of interventions and

programmes to deepen understanding about factors shaping implementation, and

hence, impact (Roen et al; Arai et al 2005). One major difference between the

qualitative and quantitative traditions concerns the notion of replicability and

generalizability. Obviously generalizability within the qualitative tradition is of a

different kind to that which is possible in an experiment or a survey (Popay

unpublished). With regard to judging the external validity of qualitative evidence,

Popay notes: ‘The aim [in the qualitative tradition] is to identify findings which are

logically generalizable rather than probabilistically so’ (Popay et al. 1998). It should

also be noted that there is a rapidly growing literature on methods for the synthesis of

qualitative research and of mixed methods research (see for example, Dixon Woods

et al 2004; Popay & Roen, 2003).

There must therefore be a commitment to methodological pluralism and

epistemological variability and a commitment to the view that epistemological

positions should not be viewed as mutually incompatible. The argument that there is

an inherent incompatibility between objectivist and subjectivist approaches is to be

explicitly rejected in favour of the view that there are different ways of knowing, and

that different ways of knowing can and do play different roles in the ways that human

actors use knowledge and information. However, in certain circumstances and for

certain purposes some forms of knowing are more practically useful. The polarization

of knowledge into objectivist and subjectivist approaches is unhelpful and misleading

14

(See Gomm & Davies, 2000; and Gomm et al 2000 for a review of helpful ways to

describe different methodological approaches). The view that all knowledge is

relative and of equal value is to be rejected in favour of a view which defines the

relevance and the salience of knowledge according to its practical value in given

circumstances.

Principle 2: Gradients not gaps

There are conventionally three different ways in which the inequalities are described:

health disadvantage, health gaps and health gradients (for a full discussion of this

see Graham, 2004a, 2004b, 2005. and Graham & Kelly, 2004). Health disadvantage

simply focuses on differences, acknowledging that there are differences between

distinct segments of the population, or between societies. The health gaps approach

focuses on the differences between the best and worst off. The health gradient

approach relates to the health differences across the whole spectrum of the

population acknowledging a systematically patterned gradient in health inequalities.

Conceptually, narrowing health gaps means raising the health of the poorest, fastest.

It requires both improving the health of the poorest and doing so at a rate which

outstrips that of the wider population. It is an important policy goal. It focuses

attention on the fact that overall gains in health have been at the cost of persisting

and widening inequalities between socioeconomic groups and areas. It facilitates

target setting. It provides clear criteria for monitoring and evaluation. An effective

policy is one which achieves both an absolute and a relative improvement in the

health of the poorest groups (or in their social conditions and in the prevalence of risk

factors).

However, focusing on health gaps can limit the policy vision. This is why the

approach advocated here is one of normally aiming to reduce health gradients. The

penalties of inequalities in health affect the whole social hierarchy and usually

increase from the bottom to the top. Thus, if policies only address those at the bottom

of the social hierarchy, inequalities in health will still exist and it will also mean that

the social determinants still exert their malign influence. The approach to be adopted

by the MEKN will involve tackling the whole gradient in health inequalities rather than

only focusing on the health of the most disadvantaged. The different meanings

associated with health inequalities and health inequity is sometimes conflated. The

principle here is to make the conceptual distinction clearly and to argue for a very

15

clear approach based on the whole population gradient. The only significant caveat

is that where the health gap is both very large and the population numbers in the

extreme circumstances is high, a process of prioritising action by beginning with the

most disadvantaged would be prioritised.

This approach is in line with international health policy. The founding principle of the

WHO is that the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is a

fundamental human right, and should be within reach of all ‘without distinction for

race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition’ (WHO, 1948). As this

1/

implies, the standards of health enjoyed by the best-off should be attainable by all.

The principle is that the effects of policies to tackle health inequalities must therefore

(

extend beyond those in the poorest circumstances and the poorest health. Assuming

■(

that health and living standards for those at the top of the socioeconomic hierarchy

continue to improve, an effective policy is one that meets two criteria. It is associated

with (i) improvements in health (or a positive change in its underlying determinants)

for all socioeconomic groups up to the highest socioeconomic group and (ii) a rate of

improvement which increases at each step down the socioeconomic ladder. In other

words, a differential rate of improvement is required: greatest for the poorest groups,

with the rate of gain progressively decreasing for higher socioeconomic groups. It

'

locates the causes of health inequality, not in the disadvantaged circumstances and

r-x

health-damaging

behaviours of the poorest groups, but in the systematic differences

....................................................

in life chances, living standards and lifestyles associated with people’s unequal

positions in the socioeconomic hierarchy (Graham & Kelly, 2004).

Principle 3: Causes: determinants and outcomes

o

Principle 4 is that MEKN will use as a basis for developing the evidence a causal

model which crosses from the social to the biological.

What is generally missing in the analysis of social factors and health is the kind of

underlying certainty about effectiveness and cause which we have come to expect

with respect to clinical medicine. Clinical medicine has its own uncertainties of

course. Aetiology is sometimes unknown or tenuous. The effects of treatments are

r

also uncertain (Chalmers, 2004). The disease categories used by medicine to

describe pathology, are not essentialist but are nominalist and therefore change and

evolve over time. Data and evidence are surrounded by uncertainty (Griffiths et al

0

2005), and the skill of the doctor is in the end about working through and with these

uncertainties, not resolving them.

J)

16

f

But not with standing the uncertain and contingent nature of the understanding of bio

medical processes, medicine operates very successfully with an underlying

epistemological principle which is that health outcomes have preceding causes and

that the isolation of cause is the basis of effective intervention. In the case of

inequalities in health real pathological changes in the human body occur, but in

highly patterned ways in whole populations. The key assumption made here is that

both the pathologies and their patterning have causes. There will be social and

biological causes working in tandem. The task is to map that process as a way of

developing an explanation. In classic scientific terms there must be covering scientific

social and biological laws (Hempel, 1965). What needs to be explained is why the

biological systems in the human body change in ways that are determined by social

circumstances. At the heart of the problem of the social determination of health and

the corresponding inequalities in health is this. The molecules in the human body

behave differently according to the social position someone occupies, according to

their job, according to their experience of class and ethnic relations, according to

their education, and according to a whole range of social factors which impact on

them over their life course. Their immunity, their nutritional status, their resilience,

their ability to cope, all act as mediating factors, but ultimately there is a biologically

plausible pathway from a number of social factors or social determinants to biological

structures in the individual human body.

In the biological clinical realm the randomized controlled trial provides the best way of

determining what the mechanisms of cause are and what precisely it is, that is

effective (Chalmers, 1998). The randomized controlled trial provides the most secure

basis for valid causal inferences about the effects of treatments (Chalmers, 1998).

Inter alia, to what extent can similar methods be applied in the social realm?

It has been argued that before 1948 clinical medicine was dominated by what today

we would call theoretical and political positions and largely untested paradigms

(Cochrane, 1972; Doll, 1998). It is suggested that these practices were tested

empirically by individual clinicians, but were never subject to the kind of deep

rigorous scrutiny which the clinical trial permits (Greenhalgh, 2001). Effectiveness

was in much more tenuous territory than it is today. Doll has argued (Doll, 1998) that

1948 was a watershed because it was the year that the streptomycin trial for treating

pulmonary tuberculosis reported. The methodological breakthrough was that

effectiveness could be plainly demonstrated. Although of course in 1948, the clinical

17

trial still had many years to go before it found general acceptance (Cochrane, 1972),

the fundamental principle was established and the causal premise was in grasp.

The question is to what extent is the study of the social determinants of public health

governed by untested paradigms? To what extent is the study of the social

determinants led by theory rather than by evidence of effectiveness? If it is to be led

by evidence of effectiveness the question of cause has to be confronted head on.

Moreover, even if the goal of seeking causes is aspirational, given the current state

of knowledge, that there are causal mechanisms at work, and that these may

eventually be discerned, is a guiding principle.

The approach to be adopted is that of separating necessary and sufficient conditions.

The necessary condition is/are the preceding phenomenon which needs to be

identified and be described without which the succeeding phenomena will not occur.

The sufficient conditions will describe the degree or volume which is required to

produce an effect. A true causal model would permit the statement, ‘if a then always

b’. By identifying the necessary and sufficient conditions it is possible to develop such

statements (Davidson, 1967). A true causal model would also account for the nature

of the relationship between a and b. This is what Hempel (1965) called the covering

law. Of course, because the subject matter is going to be surrounded by varying

degrees of uncertainty, the initial models or model will be weaker than a true causal

model. However, it is the degree of precision of the true causal model that should be

the goal, and unravelling necessary and sufficient conditions is the starting point

With respect to the social determinants of health, we are able to identify some of

what are the necessary and the sufficient conditions but the nature of which are

which, is very unclear. The core candidates can be listed relatively easily because

—--------- --------...

- ———"——

the literature has explored them at length: occupational exposure to hazards,

occupational experience of relations at work (degree of self direction), the biological

aging process , the experience of gender relations, the experience of ethnic relations

including direct experience of racism, home circumstances, degree and ability to

exert self efficacy especially through disposable income, dietary intake, habitual

behaviours relating to food, alcohol, tobacco and exercise, position now and in the

past in the life course, schooling, marital status and socio economic status. These

are the media through which the direct effects of the social world impacts directly on

the life experiences and exert direct effects on the human body. They in turn are

linked to macro variables like the class system, the housing stock, the education

18

system, the operation of markets in goods and labour and so on (see Solar & Irwin,

2005).

However, just listing the factors, neither tells you what the linkages actually are, nor

what the covering law is, nor what the biologically plausible relations actually consists

of. As Smith (2004) has argued, if we combine all the dimensions of social

differences into one construct, like socio economic group, this precludes discussion

of the policy relevant options (Smith, 2004), but it also precludes proper explanation.

There is clearly an urgent need for these processes to be modelled.

The problem of multi faceted causation will need to be considered in the modelling

process. It is clear that there are likely to be a range of factors involved in the

explanatory framework, and the component parts of the model will need to be

delineated. However, this must not degenerate into simply arguing that it is very

complex, because this is no explanation at all (Cohen, 1951). Modelling in a multi

factorial way allows the delineation of the necessary and sufficient conditions.

The evil causes evil fallacy (Cohen, 1951) also needs to be avoided in this modelling

process. Antonovsky (1985; 1987) called this the pathogenic approach. By this he

meant, a search for system dysfunction, or the identification of the breakdown of

idealized social systems. He argued that the social and medical sciences were

dominated by a pathogenic orientation. Applied to health inequalities, a pathogenic

argument is that health inequalities are a pathological deviation from an idealized

better state caused by some kind of pathological mechanism. The pathological

mechanisms are usually said to be things like global capitalism, political decisions,

failing health care systems and poverty. This is unhelpful on two counts. First,

idealised perfect non pathological social systems do not exist, and the pathology

which is identified as the cause is not an explanation, it is a political statement about

values. The value system is used as the explanation. Now that it is not to say that the

tackling of health inequalities and the associated suffering and premature mortality

are not worthwhile things to do, nor that is a value position of which to be diffident

(see above). Quite the contrary, it is a prime value which should drive forward

research and action. But a value, which determines that something is bad (or good),

is not the same thing as an explanation.

To understand health inequalities we must turn to a concept of cause which has its

origins in positivistic and rationalist thought and which in effect mirrors the kinds of

19

precision about cause which clinical medicine is capable of delivering. This, it will be

argued, requires a classical scientific explanation: neither an historical nor a

sociological explanation will do (Danto, 1968). This is because the phenomena being

explained are not historical or social: they are physical. An explanation which stops at

the social level is insufficient for these purposes. We need a model of cause which

traverses a number of levels of analysis which academic disciplines traditionally keep

separate. Some of the observed patterns which are manifested in mortality and

morbidity data are no doubt accounted for genetically or other purely biological

mechanisms, but it seems inconceivable that the health variations which follow so

closely sets of social arrangements could all be accounted for in this way. Other

processes are at work and they are amenable to causal analysis which asserts the

primacy of a pathway from the social to the biological. This does not undermine any

other form of analysis like a sociological one which operates at the level of the social,

nor does it preclude bringing aspects of the sociological explanations into play. But

the principles of cause should be applied to the issue in question across the social

and biological. In this sense the concern is not really inequalities in health, but much

more specifically the social determinants of inequalities in illness. The research

question is to find out what the social determinants of mortality and morbidity are.

This will lead further to use the distinction between the determinants of health and

the determinants of inequalities in health. The commitment to addressing the social

determinants of health is often summed up in the phrase ‘tackling the determinants of

health and health inequalities’. Such phrases can create the impression that policies

aimed at tackling the determinants of health are also and automatically tackling the

determinants of health inequalities. What is obscured is that tackling the

determinants of health inequalities is about tackling the unequal distribution of health

determinants.

Focusing on the unequal distribution of determinants is important for thinking about

policy. This is because policies that have achieved overall improvements in key

determinants such as living standards and smoking have not reduced inequalities in

these major influences on health. Positive trends in health determinants can go handin-hand with widening inequalities in their social distribution. As these examples

suggest, distinguishing between the overall level and the social distribution of health

determinants is essential for policy development. When health equity is the goal, the

priority of a determinants-oriented strategy is to reduce inequalities in the major

influences on people’s health. Tackling inequalities in social position is likely to be at

20

the heart of such a strategy. It is the pivotal point in the causal chain linking broad

(‘wider’) determinants to the risk factors that directly damage people’s health.

Therefore the model of cause needs to be articulated. The evidence should be

interrogated to determine what phenomena are attributed to other phenomena. Are

necessary and sufficient conditions specified, is the causal chain concerned with

proximal, intermediate or distal causes, and what are the plausibility levels of the

proposed mechanisms? In brief are we able to find patterns which point to strong

causal or associational relationships? To what degree are we able to discern a

consistent direction in the evidence, and to what degree are the patterns of the

results or the conclusions of studies broadly similar? Is there a relationship which

suggests that more of the exposure or the intervention produces more of an effect? If

there is then we have a much clearer sense of potential cause and are able to map

out what the proposed mechanisms are.

The level, or levels of analysis, needs to be identified (Kelly, Charlton and Hanlon,

1993). This means examining the evidence, and regardless of its disciplinary

provenance, assessing whether the dynamics of what is described could plausibly

work at a physical, societal, organisational, community or individual level. In other

words, to what degree is the policy or intervention based on biological, social,

technical plausibility? To what extent is it possible to ascertain time periods and the

chronology in the evidence? Are the purported relationships logically possible in

chronological terms? Do certain events precede others? What dynamic processes in

terms of the component parts of social systems are described? This is particularly

important in multi factoral explanations, where the sequencing of events may be

hidden, or at least difficult to discern and where, as we noted above, multi factoral

explanations are often no explanations at all.

Principle 4: Social Structure

Principle 4 aims to make more explicit the range of dimensions of inequalities that

need to be considered when building an evidence base on how best to address the

social determinants of health, including ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, area,

community and religion (Anthias, 1990; 1992). These represent linked but separate

dimensions of inequality. Whilst these discrete dimensions of social difference are

seldom denied as important, they are under developed empirically and theoretically

in the literature on social determinants. Consequently, the relationships between the

different dimensions of inequality and the ways they interact with each other to

21

produce health effects, are hardly to be found in the extant evidence at all (Graham &

Kelly, 2004). This is a point of very considerable importance because, it is clear from

the evidence that does exist, that different segments of the population respond very

differently to identical public health interventions. This means that we need to

anticipate a wide range of responses to policies across and within societies, by virtue

of the nature of the variation in populations.

What these different and variable axes of differentiation have in common is that they

result in differences in life chances. These differences in life chances are literal: there

are marked social differences in the chances of living a healthy life. This has been most

systematically captured in occupation-based measures of socioeconomic position - but

differences in people’s health experiences and their patterns of mortality are observed

across other axes of social differentiation. It is an important challenge to develop

measures of inequality that embraces these axes. If, as the evidence suggests,

dimensions of disadvantage interlock and take a cumulative toll on health, these

dimensions need to be summed in order both to map and to understand the health

penalty of social inequality.

One of the key principles therefore for the MEKN is that there are different axes of

social difference (Graham & Kelly, 2004) and that these dimensions overlap (Davey

Smith et al 2000). Within different axes of differentiation, like gender, different

aspects interplay as well, like income access to power and prestige (Bartley et al

2000). The specific health impacts will be mediated by proximal factors like social

position, specific exposures, the nature of specific illnesses and injuries and their

social significance in different cultural contexts (Whitehead et al 2000). The model

which will be developed will also need to account for the fact that these different

aspects of social difference vary independently of each other. But they also coalesce

together in varying ways to produce overall patterns of advantage and disadvantage.

Material and environmental disadvantage accumulate through the life course and in

particular childhood disadvantage is associated with disadvantage in later life

(Benzeval et al 2000). The two building blocks which will be used to develop these

ideas are those of the life course and the life world. Life course epidemiology shows

how socially patterned exposures during childhood, adolescence and early adult life

may operate via chains of social, biological or psychological risk (Kuh et al 2003;

Graham & Power, 2004). The purpose of life course epidemiology is to build and test

theoretical models that postulate pathways linking exposures across the life course to

22

later life health outcomes (Kuh et al 2003). The life world is a social space, part

physical, but predominantly cognitive and subjective. The life word is where we

experience the social structure first hand in the form of opportunities, barriers,

difficulties and disadvantage. Schutz (1964, 1967; 1970) conceptualized the totality

of the experience of the life world as a series of concentric circles. The innermost

circle is the one where the everyday contacts and routines are highly predictable and

are therefore taken for granted, which are salient and immediate and which tend

most of the time to be the most important. There are more distant parts of the life

world. It is important to note that the innermost circle of the life world may not be, and

Schutz never suggested it would be, a place that was benign and cosy. It may be

violent and bullying. It may be cold and unforgiving. It may be unpleasant and

chronically difficult. It will be the place where discrimination and disadvantage are

experienced. However, it constitutes the centre of the existence of the person. This is

because life worlds are the building blocks of social life. It is the point where social

structure impacts on the individual. The life world is where the causal mechanisms of

health inequalities operate, and the pathways to ill heath can be described. It is the

bridge between the social and the biological.

The importance of this idea for patterning of health is that health is an outcome of the

accumulated effects of a variety of social and biological factors which impact on

people at distinct periods in the life course in the life world. These factors act both

positively and negatively as well as cumulatively. MEKN will therefore proceed on

this conceptual basis.

So what is the model of social structure, if any, in the evidence? This means

considering the extent to which the evidence is sensitive to the relations between

groups and individuals and in particular the social variations and differences in the

population. The important differences along the dimensions of age, gender, religion,

caste, occupation, mobility, place, residence, status grouping, and class

membership.

Principle 5: Social Dynamics

Principle 5 highlights that the social systems and sub systems which make up

societies are not static objects, they are constantly changing and therefore the

relationships which give rise to the outcome of health inequalities and differences are

themselves also changing in terms of their force and in terms of their salience at any

given moment.

23

In compiling evidence across knowledge networks it is important therefore to reflect

on the historical dimension with respect to the social determination of health. Whilst

inequalities in health seem to be a characteristic of all modern contemporary

societies, the shape they currently have is not a given, is not set in stone. It is instead

something which changes. The question is whether there is any discernible historical

patterning which would help us to understand what is going on, and what the

processes involved actually are.

The starting point for such analysis is the path breaking work of Antonovsky (1967).

In what was one of the very earliest attempts to review historical and contemporary

evidence about inequalities in health in a systematic way, Antonovsky showed that

inequalities were a common feature of all advanced social systems. Examining data

from more than thirty international studies he argued that the inescapable conclusion

was that social class influenced a person’s chance of staying alive. Historically he

noted a variation of about 2:1 between the extremities of the social classes, although

he saw this differential narrowing in the mid nineteen sixties. This class differential

held even though overall death rates were declining. He noted that whatever the

index used, or however the class system was represented, almost invariably the

lowest social classes had the highest mortality rates (Antonovsky, 1967).

He went on to demonstrate that there was an important characteristic in the historical

differences between the most and the least advantaged across different societies. He

observed that where the overall rates of mortality were high, the differences in

mortality between the best and the worse off tended to be relatively small. This, he

claimed, characterised societies in the early period of industrialization. As rates of

economic growth increased, and particularly as industrialization evolved, the patterns

of mortality began to improve for both the most and the least advantaged, but at

differential rates. The middle and upper classes seemed to derive the health

dividends of industrialization earlier. The mortality rate of the most advantaged

improved at a faster rate than the rate of mortality of the least advantaged. The result

was that the differences between the most and least advantaged got bigger.

However, as time went on, the rate of improvement for the middle and upper classes

began to slow, while the rate of improvement for the least advantaged began to

increase, resulting in a narrowing of the difference.

This led Antonovsky to suggest that where death rates are relatively high or low, the

24

difference between the most and the least advantaged will tend to be relatively small,

but where the rates of mortality are mid range the difference between the most and

the least advantaged will be relatively high. Since the publication of these data in the

mid 1960s this pattern seems to have evolved still further. For example the gradient

in countries like Britain seems to have begun to steepen again over the last forty

years or so, and in some countries of the former Soviet block the increase in health

inequalities in recent time has been dramatic. One conclusion to be drawn from

Antonovsky’s earlier work, combined with the more recent data, is that health

inequalities are part of long term social, political and economic trends and are linked

to the playing out of policies and historical events and underlying changes in the

social structure and the division of labour in society in ways that require an

explanation in their own right.

The interesting thing about this is the shape of the curves Antonovsky described.

Both extremes are close together and the middle much further apart. One conclusion

to draw from this is that it describes a pattern that is linked to some underlying

process of modernization/ industrialization, and there are some compelling biological

(the prevalence of infectious disease, the nature of infant mortality) as well as social

(the nature of the housing stock, the appearance of decent sanitation and safe

drinking water in particular), set of factors at work. Certainly the chronology of events

would lead one in that direction. The other important conclusion is that these data

demonstrate namely that inequalities in health are not fixed, but rather are variable at

different historical time periods.

One of the more interesting ways of trying to make sense of global type data is to try

to evaluate it in the context of data from different spheres. One of the most striking

examples of this is in relation to work by Victora and colleagues (2000). They

propose the idea of the inverse equity hypothesis. Drawing on data relating to the

implementation of child health programmes in Brazil, they note a very similar, almost

identical set of curves to that described by Antonovsky, although over very much