Radical Journal of Health 1995 Vol. 1, No. 2, April – June.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

ak

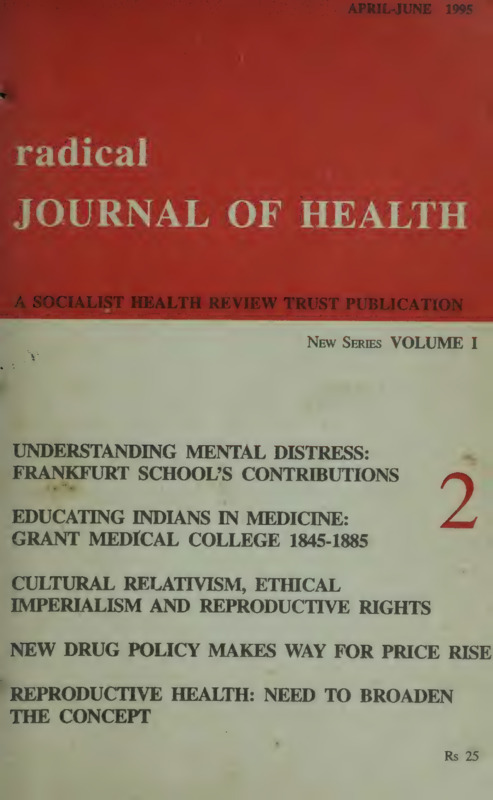

APRIL-JUNE

1995

A SOCIALIST HEALTH REVIEW TRUST PUBLICATION

New Seris

VOLUME

I

UNDERSTANDING MENTAL DISTRESS:

FRANKFURT SCHOOL’S CONTRIBUTIONS

EDUCATING INDIANS IN MEDICINE:

GRANT MEDICAL COLLEGE. 1845-1885

CULTURAL RELATIVISM, ETHICAL

IMPERIALISM AND REPRODUCTIVE

NEW DRUG POLICY MAKES

RIGHTS

WAY FOR PRICE RISE

“REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH: NEED TO BROADEN

THE CONCEPT

Radical Journal of Health is an interdisciplinary social

sciences quarterly on medicine, health and related areas published

by the Socialist Health Review Trust. It features research contributions in the fields of sociology, anthropology, economics,

history, philosophy,psychology, management, technology and other

emerging disciplines. Well-researched analysis of current developments in health care and medicine, critical comments on

topical events, debates and policy issues will also be published.

RJH began publication as Socialist Health Review in June 1984

and continued to be brought out until 1988. This new series

of RJH begins with the first issue of 1995.

Editor. Padma

Prakash

Editorial Group: Aditi Iyer, Asha Vadair, Ravi Duggal, Roopashri

Sinha, Sandeep Khanvilkar, Sandhya Srinivasan, Sushma Jhaveri,

Sunil Nandraj, Usha Sethuraman.

Production Consultant:

B H Pujar

Consulting Editors:

Amar Jesani, CEHAT, Bombay

Binayak Sen, Raipur, MP

_—Manisha Gupte, CEHAT, Pune

V R Muraleedharan, /ndian

Dhruv Mankad, VACHAN, Nasik

K Ekbal, Medical College,

Institute of Technology, Madras

Padmini Swaminathan, Madras

Kottayam

Institute of Development

Francois Sironi, Paris

Studies, Madras

ee

Imrana Quadeer, JNU,

C Sathyamala, New Delhi

New Delhi

Thelma Narayan, London

Leena Sevak, London School of |School of Hygiene and

Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Tropical Medicine, London

London

Veena Shatrugna, Hyderabad

Publisher: Sunil Nandraj for Socialist Health Review Trust.

All communications and subscriptions may be sent to :

Radical Journal of Health,

19,June Blossom Society,

60-A Pali Road, Bandra,

Bombay 400 050.

Typsetting and page layout at the Economic and Political Weekly.

Printed at Konam Printers, Tardeo, Bombay 400 034.

Volume

I

(New Series)

Number

2

Letters to Editor

April-June

1995

.

81

Editorials: ‘If You Can’t Have Bread...’

Padma Prakash

Profitable and Now Legal Sandhya Srinivasan

Managing Resources

VR Muraleedharan

83

Understanding Mental Distress: Contributions of

Frankfurt School

Parthasarathi Mondal

89

Indian Practitioners of Western Medicine:

Grant Medical College, 1845-1885

Mridula Ramanna

116

Reproductive Rights and More

Lakshmi Lingam

.

136

Communications

Making Way for Price Rise: New Drug Policy

Wishwas Rane

Reviews

Government Expenditure on Health Care

Brijesh C Purohit

:

145

:

150

Discussion Paper

Cultural Relativism, Ethical Imperialism and

Reproductive Rights

Ruth Macklin

153

Facts and Figures

Status of Indian Women: Production and Reproduction

162

Asha Vadair

Sandeep Khanvilkar

RJH

(NewSeries)

Vol1:2

1995

LETTERS TO EDITOR

Ethics in Health Care

The Medico Friend Circle, an all India group of medical people and those working in

health is holding its annual meet on December 27 to 29 at Sewagram. The theme of the meet

is ‘ethics in health care’. The organising committee invites background papers, articles,

reports , notes, case studies on any of the following or other relevant topics.

Ethical issues in : Health Policy Making and Implementation of Health Policies;

Population Control and Family Planning, Research and Use of Contraceptives; Disaster

Management; Experiments, Innovations etc in Low cost Primary Health Care Delivery by

NGOs; Technology, End Stage Diseases, Transplantation; Mental Health Care; AIDS; Cost

of Health Care and Doctor’s Fee; Any other.

For more information on the meet, write to Amar Jesani, 519 Prabhu Darshan,

31 S S Nagar, Amboli, Andheri(W), Bombay 400058.

Telephone and PCFax:022-6250363; Email:cehat @inbb.gn.apc.org.

Bombay

Ravi Duggal

ICPD Update

A small group of NGOs that met in Ahmedabad in December last had decided to form a

network of like-minded individuals interested in explorin the feasible approaches to move

forward from the programme of action adopted at the International Conference on Population

and Development in Cairo in September that year. We have called it ‘Health Watch’ and it

is visualised as a vehicle to increase the attention paid to women’s health needs and concerns

in public debate and national policy. We also felt that a periodical ‘Update’ could enhance

our interaction.

;

a

For the time being Health Watch will have its office at the Gujarat Institute of Development Research, Gota, 3824, Ahmedabad. (Phone 079-7474809-10; Fax: 079-7474811).

I would like to prepare a mailing list ( of interested people) and seek your help in the form

of addresses of individuals or NGOs who you think share the concerns about women’s health.

Health Watch will be happy to interact.

Ahmedabad

Leela Visaria

Subscription Rates

Inland

Individuals

Institutions

one year

100

150

|

(In Rupees)

life

1000

+ 3000

two years

i80

——

Foreign

Asia(excluding Japan)

(In US $)

All other countries

Africa and Latin America

one year

two years

one year

Individuals

15

25

25

Institutions

30

50

60

Remittances may be by cheque or draft and may be made out to Radical Journal

of Health. Please add Rs 20 for outstation cheques. Subscriptions rates are per

volume. Mid-year subscriptions will be treated as beginning from the first issue

of the ongoing volume.

82

RJH

(New Series)

Vol1:2

1995

‘If You Can’t Have Bread...’

The compression in the allocations for health in the 1995-96 Budget

together with the deceleration ofdevelopment and employment generation

programmes under structural adjustment will contribute to a worsening of

the health status of the poor.

THE finance minister, Manmohan Singh ended his speech to parliament

before presenting the Budget proposals for 1995-96 with these words: “Let

us strive tirelessly, as the great poet Rabindranath Tagore has said ... ‘to

build an India where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the

dreary desert sand of dead habit’.” Nothing could have been more

incongruous or inappropriate. For, if the dream is also of building an India

where its people live in health and security with adequate, even if not

plenty of food, water and shelter, the ‘stream of reason’ has long got lost.

With each new budget itis clear that the welfare of the majority is no longer

a primary concern. The ‘India’ that is being built is both by and for the

middle and upper sections of society, with the labouring masses being

squeezed out of breath little by little.

While health is a state subject, the central allocations do not, of course,

tell the entire story. But they are indicative of the government’s concerns.

Even a superficial glance at the central allocations for health in the last few

budgets show that they have barely kept pace with the inflation rates,

resulting thereby in hardly an increase in terms of the funds available.

There has thus been no real expansion of the programmes. The current

budget has allocated Rs 1,048 crore for ‘medical services and public

health’ giving a meagre 5.5 per cent increase over last year’s revised

estimates.

Health funding has always been haphazard, open as it is to influences

from outside the health sector and its needs. This is best illustrated by

central funding. of public health programmes. While each of these

programmes is supposed to have evaluation units, it is obvious that these

play no part in the allocation of funds. It is not surprising that malaria,

which has shown arecent resurgence, gets the lion’s share of the allocation

for disease programmes. But it hardly needs to be pointed out that the

resurgence is itself probably a result of the neglect of the programme at all

levels, and pumping in funds at crisis pointis not likely to reverse the trend.

Similarly, while the control of tuberculosis has now assumed priority, the

STD control programme continues to suffer.

In asense as an indicator of state’s welfare concerns the health budget

is not half as important as its other components. Take for instance, rural

development. As commentators have pointed out, not only is the increase

meagre, but the targets have been lowered; the number of rural families

RJH

(New Series)

Vol1:2

1995

°

83

under the poverty line to be assisted has come down from 23.5 lakhs to

19.5 lakhs. Even the government does not claim this is because the

numbers who need the assistance has come down. Similarly, the allocation for rural water supply has gone up by 37 per cent, but on sanitation it

has remained the same. This plus the fact that the budget has been widely

seen to be having the effect of raising the cost of living for the poor and

middle classes is hardly likely to contribute to the betterment of their

health.

It is also important to take note of the fact that under the structural

adjustment programme, there is already evident a greater degree of

unemployment. Even the most vocal advocates of the SAP acknowledge

this, but see it as a temporary measure whose impact can be minimised by

adequate funding to create safety nets. The problem, however is of two

kinds: one, as the operation of the voluntary retirement and such other

schemes have shown, the people who lose jobs are not those who benefit

from the changes in the long run, because retraining programmes are not

generally designed for them although they are supposed to be. This means

that there is a growing number of skilled under-or un-employed who are

finding it increasingly difficult to find the wherewithal for survival.

Second, in no country which has undertaken SAP can it be said that

unemployment levels have gone down. Yet another problem is that the

emphasis on export-oriented industry has had a deleterious affect on the

people’s well being especially of women who are employed in many of

these hazardous industries, and the emphasis on cash crops has reducedfood

availability for the rural poor. What is most distressing is that the government does not seem to be approaching these supposed ‘interim’ problems

of SAP with any degree of seriousness. In a sense one can hear the old

refrain emanating from the corridors of power — ‘if you can’t have bread,

eat cakes’... If you can’t get rice, eat Kellog’s rice cereals; if public

hospitals are ill-equipped, go to the private institutions; if you have no

access to drinking water, drink Pepsi or Coca Cola’.

—Padma Prakash

Profitable, and Now Legal

Legalising organ transplants will not change the fact that these procedures

are exclusively the privilege of the few who can afford their high cost.

_THE Organ Transplant Act, 1994, came into effect on February 4, 1995.

It bans trading in organs and (almost all) transplants from live donors

unrelated to the patient, incorporates a definition of brain death, regulates

those hospitals allowed to remove, store or transplant organs, and makes

84

RJH

(New Series)

Vol1l:2

1995

unauthorised removal or trafficking a punishable offence. But it will not

change the fact that kidney transplant is almost exclusively the privilege

of the few who can afford the costs of the operation and drugs.

The organ trade in India is the inevitable result of promoting medical

technology unrelated to a country’s needs. The health problems of the

majority remain neglected — communicable diseases like TB and

malaria, and the consequences of poverty, like malnutrition, which have

a far more devastating effect on their lives. But the bulk of the health

infrastructure is curative, rather than preventive. And curative medicine is

getting more technologically sophisticated, and expensive.

The success of organ transplant surgery depended on a number of

developments—in the pharmaceutical industry, with anti-rejection drugs

like cyclosporin, in medical/technical expertise (microsurgery) and even

the medical instruments industry, whether or not they were directly related

to transplant technology. Organ transplant surgery can be done successfully only by trained personnel at very well-equipped hospitals, and

depends on a battery of tests. And all this is available in India—to those

who can afford to pay. We are not here talking about kidney transplants for

everyone who needs them.

According. to press reports, kidney transplants now constitute a

Rs 400 crore industry, most of which depends on paid donors. It

cannot be acoincidence

that Karnataka, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu—

the three states where kidney rackets are now being unearthed—also

have the highest concentration of new private hospitals, offering the

latest in diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, some funded with

public issues.

.

India has a market for such sophisticated medicine. It also has a large

and growing population of poor people, unemployed, underemployed,

retrenched from productive work. The majority of Indians sannot hope to

make a decent living; instead, they get used as sources of spare parts, to

treat the very well-off, both in India and abroad. While the kidney

transplant industry has thrived (today in those states which have not passed

the act) there is little serious effortto address the problems faced by the

majority of the population. Not only daes the government decide to hand

over health care to an unregulated private sector; it has also disclaimed

responsibility for other aspects of good health—decently paid employment, good working and living conditions.

In fact, despite the risks of kidney donation {which may be acceptable

to a relative), some doctors have encouraged the poor to sell their

kidneys; they have promoted this as a solution to the problems of poverty.

(Naturally, the donors were rarely if ever informed of the risks of giving

up a kidney; others were reportedly deprived of a kidney without their

knowledge or sanction). The message to donors has been: sell a kidney,

pay off your debts, get your child married, set up a small business. And to

-RJH-

(New Series)

Voll: 2 1995

85

the government: do not ban the industry, just regulate it: ensure that the

money is locked up in a fixed deposit whose interest will give the donor

a regular income; guarantee free medical treatment for donation-related

illnesses. This way, you can give both desperate patient and povertystricken donor a new lease on life. To put forward its cause, this lobby

describes a scenario of thousands of people on dialysis and whose

salvation rests in the kidney of a poor donor—and of the thousands of

poor, unemployed, whose passport to a life of financial security lies in

donating that kidney. Unemployment, a socio-economic problem, has a

medical solution.

The argument is that people have a right to sell their boaias or any part

thereof. On that basis, one could say that prostitutes have the right to sell

their bodies. But do they do so when they have an option? Kidney

transplant surgery is one of the better refined procedures, which may be

applicable to a relatively large population. According to one estimate,

every year one lakh Indians kidney fail permanently; even the small group

which can afford to pay for the operation represents a sizeable market for

the operation. Then, there are other body parts on sale today—wombs

(surrogate motherhood has started in India, but there is no legislation on

it), ova and, one could argue, blood.(There have even been reports of

people offering an eye for sale—while they are still alive.) In every case,

economic needs guide the vendor to a decision which seems like a choice.

Poor people are being asked to make money selling their body parts.

Throughout, the government has basically turned a blind eye to the

practice.

The act was delayed for years, and passed only due to public pressure.

And it is certainly a crucial piece of legislation, to put an end to the kidney

racket; it will also monitor those hospitals which want to conduct transplants. But how will it be implemented? True, respectable doctors and

hospitals will stop doing unrelated transplants once they are illegal. But

this by itself will not put an end to the trafficking, given the demand,

the profits involved, and: the commercialisation of the medical

profession today. There are also many loopholes: allowing a spouse to

donate, and allowing altruistic unrelated donations—to be regulated by a

high-powered committee—will inevitably be used to disguise paid donation. Finally, until the act becomes effective all over India, the racket will

only move to states whick-do not ban the practice.

But even an ideal law Will not provide enough cadaver kidneys to meet

the demand. For a cadavar transplant programme to succeed in India,

hospitals will have to provide more uniform facilities, and also change

their functioning, patient care practice and inter-hospital coordination.

More important, even a well-run cadaveric programme can hope to help

only a few of those who need it. Rich countries with the best facilities are

not able to supply enough organs in their cadaver transplant programmes—

86

RJH

(New Series)

Vol1:2

1995

which is why they turn to India, where there is no waiting fy for those who

can buy a kidney.

One cannot ignore the plight of those awaiting transplants. But even

before the law, the majority of those needing transplants couldn’t afford

them. The lucky ones survived on regular dialysis. When a medical

technology is expensive and profitable, it gets promoted extensively,

and that can seem. obscene in a country where. people do not get basic

health care.

|

--Sandhya Srinivasan

Managing Resources

We have practically no experience in conducting cost-effectiveness studies in the field of health care.

|

WE often hear people complaining about the meagre amount of resources

spent annually by governments on health care. But rarely do we find

anyone seriously addressing the important question: “Is the nation using

its resources (however small it may be) allocated for ‘health care’ costeffectively?” We do not have even a tentative answer to this seemingly

straightforward question. Nor have Indian planners so far emb arked on

any serious study comparing the contributions of various programmes

(that come under social sector) on the state of health of the people. The

much publicised NSSO (42nd round, 1986) and the NCAER (1992)

studies throw considerable light on health care expenditure and pattern of

use of public and private health care facilities across states in India. They

are useful in many ways to the policy makers, but do not answer even

partially whether the nation is spending its resources efficiently. Till date,

there is not a single well-known published cost-effectiveness study at any

level (micro or macro) in India conducted either by the state or any private

body. It is also true that we have practically no experience in conducting

cost-effectiveness studies in the field of health care. Clearly this is not a

healthy way of managing our health care resources.

According to the 1993 World Development Report, India’s state of

health (measured by life-expectancy in years) is better than what one

would expect given its level of income and average schooling. But India

is also spending more than what it is predicted to, given its income and

education level. Apart from China and Sri Lanka, countries known for

their achievements, there are others with better outcome and lower

expenditure. Morocco is one among them. According to the same World

Bank report, the US is doing much worse, given its level of expenditure on

health care (which is about 15 per cent of its GNP). The logical conclusion

RJH

(NewSeries)

Vol1:2

1995

1S

ai

is that we are more cost-effective in using our resources than the US of

America. The trap in this logic is that we are comparing countries in terms

of gain in life-expectancy years, which is more than 20 years higher in the

US than in India.

The fundamental question remains: are we spending our resources in

the best way possible? There is a general feeling amongst all those

concerned that over a period of time “the gap between what is technically

possible and economically feasible” will widen. A likely consequence of

this trend will be ‘inappropriate’ provision of health care, which has been

widely reported in western countries. A recent Canadian study has found

inappropriate provision to range from 4 to 27 per cent for coronary

angiography, from 2 to 16 per cent for coronary artery bypass surgery,

and from 11 to24 percent for gastrointestinal endoscopy. This means that

the demand for guidance concerning the equity and efficiency implications of alternative health care policies will grow in the future. There is a

definite need to establish units of health economics, both at the central and

- state government levels, which could advice on how funding should be

directed apart from conducting cost-effectiveness studies. These units

should not be allowed to degenerate into mere bureaucratic leviathans.

They should have well trained health officials who have a clear appreciation of medical requirements, economic compulsions and social needs.

They must be aware of the conceptual and measurement problems involved in health care and cost-effectiveness studies. This is because the

concept of ‘cost-effectiveness’ has already been widely used by policy

makers, but itis doubtful if they are all using itin the same and ‘right’ sense.

Ultimately, the use of such studies depends on a crucial assumption.

The CE analysis may result in ‘freeing up’ resources now devoted to more

expensive alternatives. But what assurance is there that these resources

will be diverted to preferable alternatives identified? CE studies that

ignore political constraints cannot predict correctly the outcomes and costs

of policy initiatives. To say an alternative is the most cost-effective is not

enough. How to make the providers and (financiers) accept and implement

it, is equally important. Choices depend as much on values as on analysis.

We must make a beginning in our analysis of future scenarios. We must

analyse the benefits and costs of alternative policies to influence policymakers’ (and our) behaviour for an effective, accessible and acceptable

health care delivery system.

—V R Muraleedharan

KK

88

7

RJH_

(New Series)

Vol1l:2

1995

Understanding Mental Distress

Contributions of Frankfurt School

Parthasarathi Mondal

In.the recent past, Marxist ideas have been used to challenge many

of the assumptions and practices of established (biomedical)

psychiatry. This challenge has had a startling impact on the western

world, and there are many institutions, professionals and activists

which are trying to further these ‘Marxist-mental well being’ concepts

and programmes. Unfortunately, however, much

of the theory and

practice of mental distress and mental well-being in India has been

impervious to these hopeful developments in the west. The mainstream

institutional approach in India remains primarily the same as in

western biomedical psychiatry one, and that too, a caricature of it. An

analysis of these Marxist approaches to the study of mental distress

reveals that they have used some conceptual tools which draw inspiration froma corpus of social science works called the Frankfurt School

or Critical Theory. Therefore, it would be interesting and perhaps

useful to study what the Frankfurt School offers for mental distress

analysis.

THE Frankfurt School (hereafter FS) largely denotes the school of thought

which developed out of the Institute for Social Research established in

Frankfurt in February 1923. Its primary objective being to make Marxist

- concepts more relevant to the contemporary West, the FS has concentrated

on interdisciplinary social theory and it has been generally critical of

quantitative research. Out of this school, there has further developed a

large number of studies‘ which have significantly departed from the

original positions of the school. This article is concerned with the rather

strictly defined FS itself.

Over the years, there have been numerous theoretical shifts within the

proper FS itself [Kellner 1985:313]. An attempt has been made to be

~ sensitive to the positions of the older and contemporary theorists but the

focus is on the general scheme of things. Moreover, being of an exploratory nature, the paper covers only some important aspects of the work

of a few critical theorists. The most significant omission perhaps is the

work of Erich Fromm who has dealt directly with the issues of

mental distress and well-being. The idea here is to focus on those

thinkers who have only indirectly studied mental distress and well-being,

and who therefore,

need to be brought more centre-stage

in mental

health studies.

RJH

(New Series)

Voll: 2 1995

89

Here, a tentative conceptual framework has been devised and presented

in the form of certain broad questions of content and questions of method

which are necessary to any process of mental distress, mental well-being

and their societal organisation. It now becomes necessary to see what

information and understanding the FS generates when it is examined in the

context of this framework.

The questions of content are:

(i) what is the FS’s concept of mental distress and mental well-being?

(ii) what notions of and responses to mental distress in the community are

revealed by the FS?

(iii) what is the effect of these notions on the mentally distressed according

to the FS?

(iv) what is the FS’s understanding about the changes in the notions,

responses and effects on the mentally distressed, and how do they come

about?

The questions of method are:

(i) what are the Marxist and non-Marxist tools used by the FS, especially

when dealing with mental distress and mental well-being?

(ii) what questions are enabled to be asked by the tools used?

(iii) how far are the specific questions answered?

(iv) how far do the questions asked by the FS’s use of Marxist and nonMarxist tools cover the required questions of content; in other words, what

are the questions not asked and not answered by the FS’s insights?

The article is divided into three sections. After having made an outline

of the FS’s understanding of capitalism in the first section, an ‘archaeology’ of the FS is conducted in the second section in order to see what light

is thrown on ‘mental distress and well-being’ by the processes and

institutions of rationality, family, personality and intersubjectivity. The

third section ends the paper with some concluding remarks indicative of

future research.

I

Frankfurt School and Capitalism

The FS understanding of society is mainly concerned with the study of

capitalism, and although it has included in its scope some aspects of

socialism, it has mainly concerned itself with human life and societal

evolution of capitalist western industrial societies. The older FS theotists

focused on the economic and social psychological aspects of ‘postmarket’ or state capitalism. °

At the social psychological level of its approach to society, the two

preliminary points which critical theory emphasises are the apathy of the

masses and the co-optation of mass protest. The masses know from their

life-experiences that the various types of capitalism belong to the same

90

RJH_

(New Series)

Voll: 2 1995

system of exploitation, and thus they hardly react with such interest when

the mere socialisation of production (i e state capitalism) is paraded as

socialism [see Horkheimer 1987].

A distinction however is drawn — within the older FS — between state

capitalism and fascist (‘national socialist’) capitalism. In the monopolised

and cartellised world of fascism there is a total breakdown of traditional

forms and patterns of social organisation leading to the atomisation of the

individual. Those atomised individuals fall prey to the opportunist and

propagandist ideology of such capitalism leading them to be in a high

degree of anxiety and tension. It is this atomised high- strung mass which

is the breeding ground for the mentally distressed authoritarian personality

(which is examined later):

In terms of modern analytical social psychology one could say tnat National

. Socialism is out to create a uniformly sado-masochistic character, a type of man

lene by his isolation and insignificance, who is driven by this very fact

a collective body where he shares in the power and glory of the medium of

a

ich)he-has become a part [Neumann 1967: 402].

The’ psychological analysis of the later critical theorists focuses on

contemporary advanced capitalism and emphasises the social control

aspects of technology, which results in capitalist domination penetrating

the individual’s innermost psyche, turning him into a non-protesting

object of the capitalist realtiy principle full of ‘false needs’.

This technological control is.further based on the blurring of the

distinction between private and public existence whereby all individuality

is absorbed into the rationality of the repressive capitalist collectivity. The

increasing production and plethora of consumer goods in capitalism has

numbed the critical ability of the individual and ensured his complete civic

obedience. This absolute mobilisation, asserts the FS, is done to achieve

the interests of capital and of the ruling class.

Here, the FS is developing on the thesis of Karl Marx on the nature of .

the commodity as a spectacle, as a fascination:

A commodity is therefore a mysterious thing, simply because in it the seta

character of men’s labour appears to them as an objective character stamped

upon the product of that labour; because the relation of the producers to the sum

total of their own labour is presented to then as a social relation, existing not

between themselves, but between the products of labour become commodities,

social things whose qualities are at the same tine perceptible and imperceptible

by the senses... There it is a definite social relation between men, that assumes,

in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things [Marx 1986:77].

As an expansion and refinement of this psychological analysis, some

contemporary theorists have attempted a more socio-politically integrated

analysis of advanced or late capitalism.

The increasing political nature of advanced capitalism requires newer

and increased forms of legitimisation of its existence. One such form of

RJH

(NewSeries)

Voll: 2

1995

91

legitimisation is formal democracy which is not the genuine granting of

civil rights; formal democracy, by eliciting diffuse mass loyalty and no

genuine participation, enables state administrative decisions to be made

largely independent of the specific needs of individuals. This sort of ‘civil

privatism’ produces, for the individual, abstentation from real political

commitment and devotion to absolutely selfish desires, a process which is

incorporated by the welfare state, its reward and educational ideology.

This also generates justifications for the ‘naturalness’ of the capitalist

order [Habermas 1989: 36-38]. This sort of politico-economic legitimising

‘capitalism, according to critical theory, is, however, suspect to three

“crisis-tendencies”: economic, political and socio-cultural [ibid: 45-50].

What picture emerges then from the above brief account of the FS’s ©

understanding of capitalism? Against the background of the macro-level

differences between state capitalism and advanced capitalism, the atomisation

of the individual in state capitalism and the psychic domination of the

- individual in advanced capitalism become evident. Theextreme subordination

of the individual in fascist capitalism is also noted. Moreover, under

advanced capitalisrn, the individual is subjected to more stress owing to the ~

several crisis-tendencies, especially motivation crisis.

The most important contribution of the FS’s analysis of capitalism is

perhaps its recognition of the fact that the masses become participants as

much as victims in the process of exploitation:

Enlightenment and manipulation, the conscious and the unconscious, forces of

production and forces of destruction, expressive self-realisation and repressive

desublimation, effects that ensure freedom and those that remove it, truth and

ideology ... now all the movements flow into one another [Habermas 1987:338].

This recognition of mass-based volition, in contrast to its neglect in the

older critical theory, is an important starting point for a fresh look at mental

distress and its organisation, which has so far been studied from either

benevolent or social control angles mainly.

Secondly, the critique of formal democracy is also helpful in understanding societal responses to mental distress. The state supplements its

legitimation by stressing the need for experts and professionals to manage

complex decisions and situations within the vacuum left by the general

public withdrawal or introversion. This general trend could probably

explain the recent turning away from the popular perception of the 1960s

(anti-psychiatry and counter-culture) to the recently growing perception

that mental distress is an area best left to expert professionals, that it is best

tackled within the crucible of biomedicalism (in privatised institutions, if

need be) and that it has little to do with political awareness and movements.

Moreover, there is this whole issue of the link between community

psychiatry and the welfare state, which is supposed to be the product of a

labour-capital compromise. On account of fiscal ‘shortages’ arising out of

the class compromise, the state initiates the closure of big institutions for

92

RJH_

(New Series)

VolI:;2

1995

the mentally distressed. This blow to the mentally distressed becomes

more acute when the secondary effects of inflation-management by the

state are distributed amongst the unorganised and the powerless.

In addition, the point made by the economic analysis earlier that the

hegemony of bureaucratised unions, which form the core of resistance in

capitalism, is challenged by splinter groups who themselves have to be

bureaucratised — highlight the difficulty in forming a truly non-bureaucratic challenge and alternative to the present system of psychiatry and

other social institutions. According to Adorno,

..the bureaucratisation of proletarian parties...arise from...the constraint of

asserting oneself within an overwhelming system whose power is realised

through the diffusion of its own organisational fores over the whole. This

constraint infects the opponents of the system and not merely through special

contamination but also in a quasirational manner — so that the organisation is

able, at any time, to represent effectively the interests of its members. Within a

reified society, nothing has a chance to survive which is not in turn reified

[Adorno 1976:7].

The same economic analysis also talks of professionals but its deductive contributions to mental distress can be taken only with a pinch of salt.

It is true that vocational training involves considerable standardisation of

goals, thought-processes and reaction-patterns, and the internalisation of —

only a fragmented view of the world. It is also true that mental health

professionals too are subjected to such a training and world view.

Nevertheless, it is not possible to ignore the fact that-a significant part

of mental health professional work involves spontaneity and is directed

towards helping the mentally distressed to form coherent worldviews.

However, such a deductive inference does not address itself to the question

as to why some people become mental health professionals whilst others

do not.

|

)

The central thrust of the psychological analysis — the individual’s

inability to evaluate social reality rationally — may go a long way in

explaining the basic confusion and ideological view to which the masses

are subjected, leading to the ‘inability-to-explain’ symptom of such of

neurotic disorders. As Marx has said, while discussing the mystification

by a monetary capitalism,

Money as the external, universal medium and faculty (not springing from man

or from human society as society) for using an image into reality and reality into

a mere image, transforms the real essential powers of man and nature into what

are merely abstract notions and therefore imperfections and tormenting

chimeras just as it transforms real imperfections and chimeras... In the light of

this characteristic alone, money is thus the general distorting of individualities

which turns then into their opposite and confers contradictory attributes upon

their attributes... Since money, as the existing and active concept of value,

confounds and confuses all things, it is the general confounding and confusing

RJH

(NewSeries)

Voll: 2 1995

93

of all things ... the world upside-down ... the confounding and confusing of all

natural and human qualities [Max 1977: 131-32].

But the psychological analysis does not show why only some of those

confused masses respond with mental distress whilst most others do not.

Furthermore, the idea that what was once external domination has now

been internally programmed so that the individual becomes a passive

desiring machine, does not explain the phenomenon of mental distress or

its class implications.

In terms of methodology, critical theory takes up the Marxist tool of

‘crisis formation’ and addresses itself to the issue of crises 1n capitalism.

For Marx, the serious internal contradictions of capitalism — “The real

barrier of capitalist production is capital itself’ [Max 1986:250] — were

to result in a final explosive situation which capitalism cannot avoid.

Butas the FS’ analysis shows, crisis-modeling is amuch more complex

process, and subject to constant revisions with different types of capitalism. The FS’ position shows that not only do the crises of the economy

reverberate in the socio-political fields but also that capitalism postpones

its final explosion by continuously evolving methods to defuse class

conflicts and to survive its in-built contradictions. Moreover, even this

reworking of the tool of crisis-formation falls short of contemporary

developments; it does not take account of ecological and international

crises. It is a lacuna in the FS’ methodology that it does not address itself

to the implications of such a scenario, which has the potentiality of

changing the present consumption-oriented worldview to one which

appreciates the possibilities of human satisfaction in a not completely

abundant world.

Furthermore, the contention that capitalism’s critique must go beyond

the economy enables it to undertake a psychological examination of state

capitalism. In the process it uses the psychoanalytical concepts of the

‘superego’ (which has internalised the ‘surplus repression’ of dominant

exploitation) and ‘eros’ (which has been ‘sublimated’ into ‘vulgar libidinal’ expressions). The FS does not reject the psychoanalytic concept of

‘necessary repression’ (which enables human beings to live in a sane

manner in the real world) but considers such a concept to be historically

insufficient, ignoring societally-induced variations in the degree of repression over time. On the other hand, it contends that repression is heightened

in late capitalism and uses the psychoanalytical concept of ‘sublimation’

to explain the ways — ‘repressive desublimation’ — by which individuals

are led to believe in their autonomy in an actual reality of bondage.

The psychological analysis therefore seeks a synthesis of Marxist and

psychoanalytical tools. It contends that the Marxist position of freedom as

non-alienated work within the community setting is the only way to

individual and collective liberty. It also uses the psychoanalytical tool of

repression to explain the way excessive repression works, but as Marxists,

94

RJH

(New Series)

Voll: 2

1995

believes in the fact that work need not be only repressive. It can be

liberative too, through ‘re-erotisation’ [see Marcuse 1970]. But, as noted

above, such a methodological synthesis leads to a greater emphasis on

psychoanalysis per se than on class analysis, and it is unable to explain the

‘jump from societal discontent to mental distress’.

Many of the infirmities of the above answers by the FS.to the questions

raised in the conceptual framework of this paper are sought to be overcome

inthe FS’ analysis of rationality, personality, intersubjectivity and familial

processes.

II

Frankfurt School and Mental Distress

Mental distress in general usage is mostly expressed in terms of

rationality and irrationality. The FS dwells at length on this issue.

RATIONALITY AND MENTAL DISTRESS

The FS! assumes that one of the most important principles of human

existence — reason — which forms the basis of the other important goals

of life, of truth, freedom and justice, is subject to a rapid process of decay

in contemporary western industrial societies.

ape

This philosophical concept of reason, evident in western societies

before the technological revolution of the 19th and 20th centuries, and

reaching its zenith during the Enlightenment, included the concepts of

critique, freedom

and autonomy,

vision, and will. Such a rationality

established the criteria of rigidity, clarity and distinctness as essential to

any rational cognition. Necessarily therefore, reason set skepticism as a

methodological cheek on itself: to doubt, cross-check and rethink was to

become immanent in the four processes of pre-technological rational

behaviour. Moreover, pre-technological reason was a moral one because

of individual autonomy wherein the individual had not only alternative

action-choices available to him but also a knowledge of the genesis of

these action choices.

Pre-technological rationality was also emancipatory because of vision

and will-power. It willed a better world for human beings, and this force

led it to assume a non-Nature unity and compelled it to become critical by

fighting illusion and dogma.

In other words, such a rationality was,

content-wise and methodologically, a committed rationality. But pretechnological rationality became a ghost of its former self with the coming

of modernity. The cold rationality which so distinctly characterises the

contemporary individual, after having demolished the false worship of

things, allied itself so closely with the newly-forming and rapidly-spreading capitalist system that individuals became, more than ever before,

RJH

(NewSeries)

Voll: 2

1995

95

dependent on a world of thing and commodities. In other words, what

happens is that “‘...in the service of the present age, enlightenment becomes

wholesale deception of the masses” [Adorno and Horkheimer 1979:42].

This is an advance over Marx’s economistic reading of technological

rationale [Marx 1988: 318-19].

.

The FS strongly asserts that reason in contemporary times can no longer

be called rational metaphysics although the patterns of rationalistic

behaviour have remained. The methodical and regular ordering of ‘facts’,

perception of their interconnections and arrival at the logically correct

conclusions remain. It is the search for a final cause or absolute truth of

Nature and man which has been removed. Therefore, the claim by

technological rationality that it is also anon-ideological critique of illusion

is contradictory because, on one hand, it seeks to project itself as a neutral rationality beyond any subjectivity and so is the most methodical, scientific and logical challenge to the veil of illusion in human society. On the

other hand, existence is geared to technological production and norms of

behaviour and so it illicitly involves a value-choice, which is always a

subjective process.

Technological rationality is aimed at the technological control over the

objectified processes of nature and man, and is therefore instrumental in

character. This instrumental rationality is concerned with survival and

adaptation only. The mass or the collective takes over the personal. Hence,

any individual protest or resistance is considered to be irrational simply

because such protest would overthrow the technological rationality and

constitute a threat to his survival.

|

Critical theory’s analysis of reason and rationality throws up a number

of problems. It seems to have glorified the sanctity of pre-technological

reason and has failed to contextualise it properly. It is not clear, for

instances whether pre-technological reason was interested in the postulate

of human freedom, welfare and justice, or in the welfare and autonomy of

only a specific category of people in each historical period.

Again, the FS handling of the relationship between instincts and reason

leaves such to be desired. What is the nature of an instinct? In what ways

‘ are instincts complementary to and a part of-reflective and committed

reason, and in what ways are they opposed to it? The difficulty arises

because of the usage of the concepts of omitted, reflection and instinctcomplementarity .in pre-technological reason. The innate propensity to

rational acts performed without conscious intention (ie with instinct)

cannot be one and the same thing as a rational process operating with a

particular intent and fully aware of itself and its object (ie committed

reflection). Intentional consciousness exists in the latter whilst the former

is completely unaware of its rational process and intention. It is not very

difficult to contend, then, that one cannot have complete consciousness

and absolute unawareness in one and the same rationality. Moreover, the

96

|

RJH_

(New Series)

Voll: 2 ° 1995

contemporary rationality results in innate, usually fixed, patterns of

behaviour especially in response to certain stimuli and can also be

considered to be instinctual. Hence, what is more important is the goal of

each rationality rather than the absence or presence of instincts. The goal

of reflexive reason was individuality and liberty whereas the goal of

technological reason is the perpetuation of bonded judgment and living.

What appears to be even more illogical is the (older theorists’ )constant

refrain of disappointment at technological rationality’s emphasis on

putting the ‘good’ of the collectivity before the ‘good’ of the individuai.

If it is to be accepted that a vast range of individual human potentialities

exist and that human society is an inescapability (at one and the same time),

then it follows that the full expression of individual will, to various

degrees, trample upon the full expression of collectivity. Hence, a certain

compromise — to which the FS is doggedly opposed in an implicit manner

— between individual aspirations, and societal] imperatives of organisation

and function is the absolute minimum for human civilisation to continue.

As regards the important issue of individual autonomy, it is essential to

be cautious of aromanticisation of the individual’s ability to make choices

consciously in the pre-technological era. What is even more romantic is the

FS contention that technology is fine by itself, and that it is only when it

is misused that an unjust social order based on repressive technology

develops. This neglects the historical-sociological fact that no technological development takes place where the dominant socio-economic and

political factors are not at work: The two are more or less immanent in

each other.

The main problem with the FS (especially of the older theorists) critique

of rationality however could lie somewhere radically different, as made

out by the later theorists:

The critique of instrumental reason, which remains bound to the conditions of the

philosophy of the subject, denounces as a defect something that it cannot explain

in its defectiveness because it lacks a conceptual framework sufficiently flexible

to capture the integrity of what is destroyed through instrumental reason. To be

sure, Horkheimer and Adorno do have a name for it: mimesis... But the rational

core of mimetic achievements can be laid open only if we give up the paradigm

of the philosophy of consciousness namely, a subject that represents objects and

toils with them — in the favour of the paradigm of linguistic philosophy —

namely, that of — intersubjective understanding or communication — and puts

the cognitive-instrumental aspect of reason in its proper place as part of a more

encompassing communicative rationality [Habermas 1988:281-82].

It is because of the potential contributions of a philosophy of communication that mental distress shall be discussed later in connection with the

process of intersubjectivity and language.

Despite these problems, the FS critique of rationality contributes to a

better understanding of mental distress by challenging the dominant

RJH

(New Series) Voll: 2 1995

97

assumption that human beings can rationally control their destinies

by social techniques and other forces of empirical control, and by asserting that man’s emancipation lies in a reflective, conscious and noble

reason.

This sort of critique seems to suggest some lines of thought for the study

of mental distress. For instanced present-day civilisation and its discontents, it seems, are based substantially on a rationality which technologically represses all instinctual and spontaneous expression of individuals,

and makes it mandatory for a man to master all rebellious tendencies in

order to be called rational or sane. Any protest becomes irrational or

insane. This approach to or an understanding of rationality and irrationality, which was originally imposed, is not internalised as a ‘durable’ attitude

which labels as irrational or insane any behaviour or thought which is

opposed to (and thus disruptive of) the technological process and matterof-fact’ attitude required to survive in it.

But whereas it is true that such a repressive regime is conducive to a

higher level of general discontent and emotional distress, there is no

conclusive proof yet of the implicit assumption that the proportion of

the mentally distressed during pre-technological rationality was lesser

than the proportion of the mentally distressed during contemporary

rationality. In addition, not all those who protest today — and there are

many forms of individual and collective protests — are perceived as or

express themselves through mental distress. In other words, the FS’s

contribution lies more in explaining the general level of discontent than in

expressing the jump from discontent to mental distress, that is, the

phenomenon of mental distress itself.

Another possible area of contribution arises from the contemporary FS

_ derivation of Frederick Sohellina’s conception of reason as controlled

insanity [Habermas 1988: 281-82]. According to this derivation, pretechnological reason tried to make sense of the shapeless phenomena of

the world with the purpose of human liberation. Insanity also aims at

creating a base for the unity and coherence of the world but it is a perverted

process. Yes, but how is insanity perverted? And is this perversion

tolerated by the substantive reason because of the similarity of goals

between reason and insanity or because the perversion process is significantly akin to the rational process?

The theorists go on to add that positivistic empiricism merely abstracts

out. of the shapeless phenomena only that which can be reduced to

manipulable quantifiables. Therefore, this rationality excludes from its

domain the insanity which was a tolerated part of critical reason, but it

never eradicates or vanquishes insanity. Hence, it is precisely because this

technological rationality is a husk of critical reason, a mere reflection of

the parts and not a coherent whole, that it ignores insanity but never really

comes to meeting the challenge of insanity which fundamentally under98

RJH_

(New Series)

VolI:2

1995

mines its very base. In short, this rationality is able to tackle insanity only

to the extent it can reduce the phenomena positivistically.

.

As it turns out, insanity is such more than what positivism can tackle,

so that (for it) the greater part remains ungovernable and meaningless. This

sort of derivation directs attention to the broad link between sepal distress

and rationality but it does not speak much of the nature of mental distress

itself. The intensity of the FS possible contributions to the conceptual

framework of mental distress is further weakened by some problems in

methodology. The FS’s use of the concept of rationality enables it to look

at the psychological constructs of capitalism, a process not sufficiently

explained by Marx.

Max Weber’s work, despite its different methodology, was complementary to Marx’s. Weber expounded on the traditicnal Marxist concept

of ‘socialisation’ of society through his own concepts of ‘rationalisation’

and “demagicisation’. Rationalisation, for Weber, is the historical perme-

ation of the monological formalism of modernisation and industrialisation

into all spheres of life. This is made mainly possible by what Weber calls

“the

rational

ethics

of ascetic

Protestants”

[Weber

1985:

27].

Demagicisation, by extension therefore, is the process of elimination

(from theory and practice) of all unpredictable and ‘irrational’ sensuous

and mysterious elements.

;

Weber’s analysis enables critical theory to adopt critical tools for social

analysis but it fails to distinguish between the two possible scopes of the

Weberian tools, viz (1) aprocess which has permeated all spheres of life but

not necessarily all thought and all action in all the spheres of life, and (ii)

a process which has permeated human society and psyche comprehensively, and hurtling towards its self-fulfillment. Critical theory’s reworking seems to take the latter scope as the entire Weberian usage, and this

uncriticality disables it from explaining the facts of widespread ‘irrational’

behaviour, counter-cultures, resistances and other genuine

‘reflective-

thoughtful’ human processes in contemporary western societies.

Whereas this reworking of a Weberian remoulding of an orthodox

Marxist concept illustrates the FS methodological affinity to orthodox

Marxism, its position on man’s relationship to Nature illustrates its

departure from orthodox Marxism. The conservative use of this concept

states that man has progressively dominated Nature in order to control it

for his own benefit (resulting in civilisation) but that this linear process

gets vitiated in the course of time by certain minority classes forcibly

appropriating the benefits of this process at the cost of the oppressed

masses.

For the FS, on the other hand, this concept means that the original

harmony of man living within Nature gets disturbed as man tries to

dominate Nature more and more through technology and a technical social

organisation. It is this technical social administration of society which

RJH

(New Series)

Voll: 2 1995

5

99

cruelly and necessarily dampens man’s individuality in order to maintain

social cohesion, and also man’s conquest over Nature. The methodological implication of this departure is that the analysis of rationality becomes

more ps yehological, and less economic and-historical, leading to a weak

emphasis on class issues.

It is against the background of the above tatipaatiey that the FS analyses

the family as a general social unit, with special reference to personality

structure and its implications for mental distress.

FAMILY AND MENTAL DISTRESS?

In the 1930s, critical theorists thought that the-family was the most

important mediator in behaviour modification between the individual and

society.

The family was, however, taken to be an element of domination

which harshly suppressed all instinctual drives of the child towards free

development and creativity in a class society. The central mechanism in such a repressive process was the father-son relationship, whereby the

father strictly oriented the naturalness of the child towards a striving for

economic status and political position. It was such a family regime which

produced a personality type which was oriented towards submission to an

exploitative social structure, and which itself exulted in its perpetuation.

There was a change in the position on the family in the 1950s.

According to this version, the family is not authoritarian when compared

to the authoritarianism of mass society. In this amazing volte face made by

the FS, the

.

i

...father was in large measure a free man ..he became for his child an example

of autonomy, resoluteness, self-command, and breadth of mind. For his own

sake he required of the child truthfulness and diligence, reliability and intellectual awareness, love of freedom and discretion, until these attitudes having been

internally assimilated by the child, became the normative voice of the latter’s

own conscience.. -[Horkheimer 1974:71-72].

In addition to these general accounts of the family, a more psychological

analysis is also attempted. This psychological examination focuses more

on the mass character of society in the west and comes to the conclusion

that although the family structure has loosened, individuals are again

subject to conformity: the individual does not have enough mental space

of his own [Marcuse 1970:88].

It is the lack of the importance of the father, as a result of the fragmented

family, which ensures that individuals will without autonomy in western

societies:

The technological abolition of the individual is reflected in the decline of the

social function of the family. It was formerly the family which, for good or bad,

reared and educated the individual, and the dominant rules and values were

transmitted personally and transformed through personal fate. To be sure, in the

100

RJH

(New Series)

Voll: 2 1995

=

Oedipus situation, not individuals but generations (units of the genus) faced

each other; but in the passing and inheritance of the Oedipus conflict they

became individuals, and the conflict continued into individual life history.

Through the struggle with father and mother as personal targets of love and

aggressions the younger generation entered societal life with impulses, ideas

and needs which were largely their own. Consequently, the formation of their

superegos the repressive modification of their impulses, their renunciation and

sublimation were very personal experiences. Precisely because of this, their

adjustment left painful scars, and life under the performance principle still

retained a sphere of private non-conformity [ibid:. 86-87].

Other than stating the high level of discontent closed by declining hold .

of the family, the FS is not able to contribute much to an explanation of

mental distress within the specific context of the family. It is doubtful as

to how totalising has been the effect of the capitalist manipulation of the

psyche overriding the family’s influence. Moreover, by altering its 1930s

position on the family, the FS neglects the possibilities of the link

between the real authoritarianism and mental distress. The

greater problem of such a conceptualisation is the neglect of the general

issues as belied by the emphasis on patriarchy; the womenfolk hardly ever

came into the picture.

In methodological terms, the volte face of the FS on the family could

probably be explained by its relinquishing (by the 1980s) of the working

class as the subject of social emancipation, and the consequent emphasis

on individuality and not on class consciousness. This switch, and the

subsequent theoretical preoccupation, enables the FS to perceive the

bourgeois family in aromantic haze. Furthermore, it says precious little on

the phenomenon of mental distress, the family’s role in formations and

changes of perceptions, and the family’s influence on the broadly societal

response to mental distress. These lacunae arise because of an uneasy

synthesis of Marxist and psychological concepts.

AUTHORITARIAN PERSONALITY AND MENTAL DISTRESS?

The central assumption of the FS (mainly the old theorists) in its study

of personality (its preoccupation being the authoritarian/fascist/prejudiced variety) is that the socioeconomic and political convictions of an

individual form a pattern which is acoherent one and which expresses deep

processes in his personality.

_On the basis of this and a few other assumptions, a picturisation of two

broad (non-exclusive) personality types is arrived at: (i) the authoritarian

or fascist type which is featured by conventionality, rigidity, repression,

and sometimes by the break-out of its weakness — fear and dependency

- (this type experiences an authoritarian and exploitative parent-child

relationship), and (ii) the egalitarian type which is featured by egalitarian,

affectionate and permissive interpersonal relationships.

RJH

(New’Series)

VollI:2

1995

:

101

The authoritarian personality arises from a certain social and psychological background. With the levelling out of the distinction and opposition between critical high culture and social reality in the modern times,

there is aconsiderable constriction of the liberative sublimation offered by

‘high culture’. Desublimation is the rule of the day. It is within such an

environment that the authoritarian personality develops. Herbert Marcuse

explains:

...the technological reality limits the scope of sublimation. It also reduces the need for sublimation. In the mental apparatus, the tension between that which

is desired and that which is permitted seems considerably lowered...The

individual must adapt himself to a world which does not seem to demand the

denial of his innermost needs — a world which is not essentially hostile. The

organism is thus being preconditioned for the spontaneous acceptance of what

is offered. Inasmuch as the greater liberty involves a contraction rather than

extension and development of instinctual needs, it works for rather than against

the status quo of general repression — one might speak of “institutional desublimation”. The latter appears to be a vital factor in the making of the

authoritarian personality of our time [Marcuse 1964: 73-74].

It is against such a context that the FS analyses mental distress.

Mentally distressed persons, it seems, usually display the same levels of

susceptibility to prejudice as normal people. However, the highly prejudicial have lesser awareness of the genesis of configuration of their

mental distress and are less amenable to psychological explanatory frameworks, whereas the lesser prejudiced are more aware of their mental distress and more open to introspection and psychological analysis. In

other words, the correlations between personality and prejudice variables

remain the same for normal and mentally distressed people but in the

mentally distressed they appear in pathological mores and processes.

From this it is deduced that the severely mentally distressed, as

compared to the mildly mentally distressed, display the personality

features of the highly prejudiced individual: rigidity, conventionalised

thought, categorical rejection of impulsive behaviour, narrow and undifferentiated range of ego experiences, and interpersonal relations of

‘dominance-submission’. Hence, whereas the relatively stronger egos and

interpersonal relationships of the less prejudiced are more consistent with

neurosis-formation, the egos in the highly prejudiced become weak owing

to the surfacing into the consciousness of unresolved conflicts. In more

extreme forms, the egos become depersonalised and psychotic manifestations follow.

This analysis of the personality, prejudice and mental distress is the first

concrete step (especially by the older critical theorists) towards an understanding of the phenomenon of‘mental distress itself. Despite the difficulties with such an analysis, the advances at least broadly underline the

possible linkage between prejudiced personalities and mental distress.

102

RJH_

(New Series)

Voll: 2

1995

However, whereas it is possible to conceive of a correlation between

highly prejudiced individuals and mental distress in general (i) the ‘jump’

from prejudice to mental distress, from disturbance to pathology, is not

explained, and (ii) the fact that to various degrees normal people too are not

aware of themselves, repress impulses, and have rigidity in defences and

interpersonal relationships is ignored. This means that to the extent a sharp

distinction is not made between lesser prejudiced individuals and normal

people, to that extent it is not possible to explain the correlative propensity

of the lesser prejudiced individuals towards milder forms of mental

distress. In other words, the basic requirement of a clear distinction

between normal and insignificantly prejudiced individuals, and between

abnormal and highly prejudiced individuals is missing.

Furthermore, this analysis of personality and mental distress does not

answer the question as to what happens to the societal notion of mental

distress within the individual after his affliction, and (after exhausting all

the possibilities of the fundamental psychoanalytical processes) as to why

some express mental distress whilst others do not.

And, although the FS’s position advances by using psychoanalysis to

highlight the importance of childhood and familial experiences in the

formation of mental distress, it is the parent-child relationship which is

conceived as the fundamental structure despite the mention of environmental

factors. Moreover, this concept of personality rules out the process of

autonomy and volition, making individuals prisoners of infantile history and

pre-history. Furthermore, it betrays an over-emphasis on the father-child

relationship at the expense of gender issues. All these difficulties reveal the

patriarchal nature of the psychoanalytical analysis. It reveals the political

economy of the family which is based on the aggrandisement of communal

wealth, dominance of the man, and subjugation of the woman:

It (ie the monogamous family) is based on the supremacy of the man; its express

aim is the procreation of children of undisputed paternity, this paternity being

required in order that these children may in due time inherit their father’s wealth

as his natural heirs [Engels 1990].

There seems to be another central problem with the psychoanalytical

processes of the id, ego and superego, which are thought to underlie mental

_ distress. The ego, in being considered as the reality-satisfying and individual-protecting process which compromises the needs of the id and

superego, leads to a mutually exclusive dichotomy between the processes

of the id and superego. In other words, what is normative becomes

naturally opposed to what is instinctual and vice versa. It is a fallacy to

conceive of the normative and the instinctual in such exclusive and transsocietal terms. Although there are some norms and instincts which are

universal, what might only be a norm in one society might be an instinct

as well as a norm in another society. Therefore, it becomes necessary to

specify what exactly constitutes the superego and what the id.

RJH

(NewSeries)

Voll: 2 1995

103

Additionally, the implicit assumption in the analysis that the expression

of instincts of the lesser prejudiced make them less prone to mental distress

and vice versa for the highly prejudiced, and that the expression of instincts

is desirable, is again a sweeping assertion because it is always normatively

decided in societies that the undifferentiated expression of instincts is not

desirable and subsequently it is always normatively decided which instincts are to be expressed and which not, and these decisions change over

time.

There are two additional issues which require examination. Firstly, the

juxtaposition of prejudice and mental distress can also lead to a study of the

inter-relationships between the prejudiced, the formation of perceptions of

mental distress within them and the changes in these perceptions within the

context of the forces which brings these changes. This analysis which the FS

has not conducted is likely to contribute to the conceptual framework.

Secondly, the FS’s intention to study more how ideologies spread

and get accepted and less how ideologies per se originate, belies the

FS’s implicit model of social movements, viz: ideas originate in a limited

manner within a society and then they gather or do not gather momentum

depending on the levels of readiness in the personality structures of the

majority of the individuals within that society. The socioeconomic factors

are important but personality structure is far more important.

In methodological terms, the FS critique of the personality is based on

an inadequate synthesis of psychoanalysis and Marxism. This leads to a

determinist model which leaves little scope for the role of individual

autonomy or volition.

INTERSUBJECTIVITY AND MENTAL DISTRESS

As mentioned before, the later FS contends that the older FS’s critique

of instrumental rationality is problematic because it remains tied to a

‘philosophy of history’. In order to overcome this difficulty, the later FS

recommends a shift towards the process of language and intersubjectivity.

Marx had already indicated the importance of these two processes:

Language is as old as consciousness, language is practical, real consciousness

that exists for other men as well, and only therefore does it also exist for me;

language, like consciousness, only arises from the need, the necessity, of

intercourse with other men...where there exists a relationship it exists for me...

[Marx and Engels 1976].

FS general framework of normal interaction between individuals and

their personality development through the tool of language is basically a

modification of Noam Chomsky’s model.

Chomsky’s model postulates that every natural language constitutes a

finite number of elements, out of which a person can manufacture an

infinite number of sentences. Such an individual intuitively differentiates

104

|

a

RJH

(New Series)

Voll: 2

1995

between correct and deviant formulations, a skill which also enables him

to classify the seemingly senseless sentences according to the degree of

volition of the intuitively learnt rules.

The history of individual exposure and ability in language suggests that

the knowledge acquired is much less than the ability exhibited. Hence,

asserts Chomsky, there is an abstract linguistic system of regulations

which is generative of rules. This system is based on the relationship

between and development of the individual’s stimuli bombardment and

organic saturation. Furthermore, this apparatus consists of language

universals which predetermines the form of all natural languages, and/is

an expression of deeper psychic process.

Chomsky states that

A child who is capable of language learning must have (i) a technique for

representing input signals, (ii) a way of representing structural information

about the signals, (iii) some initial delimitation of a class of possible hypotheses

about language structure, (iv) a method

for determining what each such

._ hypothesis implies with respect to each sentence, (v) a method for selecting one

of the (presumably, infinitely many) hypotheses that are allowed by (iii) and are

compatible with the given primary linguistic data [Allen and Buren 1972:142].

This sort of linguistic capability ... ‘linguistic competence’ ... is based

on the logic of an immediate and clear understanding of the meanings of

the subject and object by each other, because they operate on the same

premises of validity and invalidity.

This sort of intuitive pre-communication knowledge and operation of

language, of human relationships, ignores according to critical theory, the

very substantive and formative social psychological influences. In other

words, in contrast to Chomsky, it is necessary to distinguish between

universal meanings in languages which are peculiar to a person and which

precedes all communication and meanings which are formed out of a

process of human interaction or inter-subjectiveness. Further, these universalities are very much immanent with role-expectations and role-

playing, which are naturally based on the approach to life, and which vary

from culture to culture. The validity or truth of the universal meaning

elements are, therefore, determined by the cultural systems within which

they are located.

These historically-specific world-views

,

...determine the following (a) whether a finite number of independent and not