RF_DIS_6_A_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_DIS_6_A_SUDHA

Polio News

.

.

.

'

■

-.

-

-

'

■

WHO

.

.

w

-/W

- v

■■./

■

unkef

-

Post-certification

era

TCG reviews 3 hightransmission" countries

Aventis Pasteur

donates more OPV

Page 2

Page 5

Page 6

A Newsletter for the Global Polio Eradication Initiative

Department of Vaccines & Biologicals

World Health Organization

in association with Rotary International,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

and the United Nations Children's Fund

!

2002: Lowest number of polio infected

countries ever - but more cases

T most seven countries will

still be endemic for polio at

the close of 2002 compared

to 10 countries last year.1

S'

Furthermore,

the

vast

majority of cases - more than 85% - are

A

® W

Polio eradication highlights2002:

■ EURO certified polio-free. Combined with the

'

WHO's Region of the Americas (1994) and Western

Pacific Region (2000), more than three billion

people in 134 countries now live in certified-zones

■ No polio detected in Sudan or Ethiopia

■ Improved access in countries affected by complex

emergencies - Afghanistan, Angola and Somalia

■ Type IIpoliovirus has not been detected for the

past threeyears

TCG Findini

I I 11j I I 1. 11J I I I

confined to just nine states/provinces of

76 within India, Nigeria and Pakistan.

Despite this geographical restriction in

transmission, a five-fold increase in cases

in northern India and Nigeria will result

in more cases for 2002 (1461 to date)

than for 2001 (483 total). The northern

India state of Uttar Pradesh alone

accounts for more than 60% of the global

total {see pages 3 and 5 for more details).

Four endemic countries - Afghanistan,

Egypt, Niger and Somalia- have lowintensity transmission with fewer than

25 cases combined. ♦

THE GLOBAL TECHNICAL

CONSULTATIVE GROUP (TCG) FOR

POLIOMYELITIS ERADICATION

Due to the approach of the end

2002 target date for stopping

transmission, and the evolution

of research on post-certification

immunization policy, the

Global TCG held a special

interim meeting

13-14 November 2002 in

Geneva. Much of this issue of

Polio News highlights

the TCG's findings.

, —•

’ All data in this issue of Polio News is as of 3 December 2002.

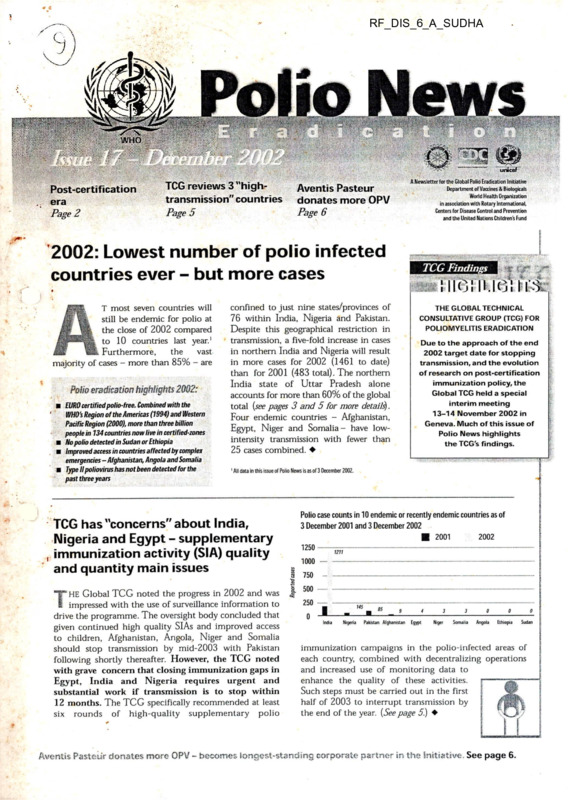

Polio case counts in 10 endemic or recently endemic countries as of

TCG has "concerns" about India,

Nigeria and Egypt - supplementary

, immunization activity (SIA) quality

and quantity main issues

*STK HE Global TCG noted the progress in 2002 and was

I impressed with the use of surveillance information to

drive the programme. The oversight body concluded that

given continued high quality SIAs and improved access

to children, Afghanistan, Angola, Niger and Somalia

should stop transmission by mid-2003 with Pakistan

following shortly thereafter. However, the TCG noted

with grave concern that closing immunization gaps in

Egypt, India and Nigeria requires urgent and

substantial work if transmission is to stop within

12 months. The TCG specifically recommended at least

six rounds of high-quality supplementary polio

3 December 2001 and 3 December 2002

■ 2001

1250

2002

1211

1000

| 750

t 500

£

250

0

145

JL

India

Nigeria

85

9

Pakistan Afghanistan

4

3

3

0

0

0

Egypt

Niger

Somalia

Angola

Ethiopia

Sudan

immunization campaigns in the polio-infected areas of

each country, combined with decentralizing operations

and increased use of monitoring data to

enhance the quality of these activities.

Such steps must be carried out in the first

half of 2003 to interrupt transmission by

the end of the year. {See page 5.) ♦

Mentis Pasteur donates more OPV - becomes longest-standing corporate partner in the Initiative. See page 6.

Technical tips

Risks of polio paralysis in the post-certification era'

Part One

’Risk

category’'

POST C-^l li-ICAllON

IMMUNIZAl lOi'l POLICY

■

\

Risks of polio paralysis

from continued use of

oral polio vaccine

Risk

fregueriRy

Esiifftertffd global

anniii}} buraen "

VAPP

1 in 2.4 million doses

of OPV administered

250-500 cases per year

cVDPV

One episode per year

in 1999-2001

(Haiti, Madagascar,

the Philippines,)

Approx. 10 cases per

year (total of 29 cases

in three years)

iVDPV

19 cases since 1963,

with 4 continuing to

excrete; no secondary

cases

<1 case per year

Inadvertent release

from an IPV

manufacturing site

One known event in

early 1990s

No cases

Inadvertent release

from a laboratory

None to date

Intentional release

None to date

FRAMEWORK FOR THE ASSESSMENT & MANAGEMENT

OF PARALYTIC POLIO IN THE POST-CERTIFICATION ERA

The November interim meeting of the TCG endorsed the

framework which has been developed to summarize the

risks of paralytic poliomyelitis in the post-certification

era. This framework will be particularly important for

discussing post-certification immunization policy with

OPV-using countries and for developing policy decision

models. The framework divides the risks into two

major categories: (a) those due to vaccine-derived

polioviruses and (b) those due to the handling of wild

poliovirus stocks.

Risks of paralysis from

mishandling of wild

poliovirus

This page summarizes the research to date on the nature and

magnitude of the risks of vaccine-derived polioviruses as

presented to the November TCG. The next issue ofPolio News will

include an update on the risks of polio paralysis due to the

handling of wild poliovirus stocks, with a special focus on the

progress in containment.

‘ Study and data collection is ongoing lor a

' ’ Under current polio immuniza

s

(see table on the right)

Risks from the continued use of

oral polio vaccine (OPV):

VAPP, cVDPV and iVDPV

key factor in the risk assessment for OPV-using

countries is the small but continuing risks of

paralytic polio due to OPV. These include vaccine

associated paralytic polio (VAPP), the emergence of

circulating vaccine derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) and

excretion of VDPVs from immunodeficient people

(iVDPV). Preliminary estimates presented to the TCG on

the total global burden of disease due to VAPP, measured in

terms of the number of cases per birth cohort, is 250-500

cases per year. Although the risk of emergence of a cVDPV

appears to be even lower than VAPP, it is conditional on

factors such as the level of population immunity and

immunity gaps. Screening of >5000 Sabin polio isolates and

enhanced global surveillance for cVDPVs over the past

three years has documented cVDPV on just three occasions

at a frequency of one episode per year. These three recent

cVDPV outbreaks resulted in a total of 29 cases, but

experience from the pre-eradication era in Egypt suggests

that cVDPVs may establish endemicity under certain

conditions. The iVDPV burden from 40 years of use of

OPV stands at 19 cases globally with just four patients

continuing to excrete poliovirus today. There have been no

secondary cases. New research is underway on further ways

of expressing the risks from cVDPVs and iVDPVs, and will

be presented to the Global TCG meeting on an ongoing

basis. ♦

□

1

Vaccine derived poliovirus

(VDPV) investigation and

response guidelines

J SING the data and experience available at the end of

B 2002, the TCG endorsed interim guidelines for

responding to the isolation of VDPVs. These

guidelines emphasize the need for a mop-up response to (a) any

AFP cases from which a VDPV is isolated which has greater

than 1% genetic drift and recombination with a group C non

polio enterovirus and (b) any cluster of AFP cases from which

a common VDPV is isolated (see below). The guidelines state

that in all other instances the first response should be an

appropriate epidemiological, clinical, immunologic and

virologic investigation. If there is an identified immunization

coverage gap, whether geographic or demographic, this(

’d

be addressed while the investigation is ongoing, xuese

guidelines will be updated as additional information becomes

available. The WHO guidelines on response to wild poliovirus

are also being updated to include the VDPV investigation and

response guidelines. ♦

B

g

Decision-tree for responding to the isolation of a vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV)

2 AFP cases’

mop-up

Immediate mop-up if VDPV has >1% drift

and recombination with a non-polio Group C

enterovirus

Otherwise evaluate for gap in population immunity

0 AFP.cases = investigate

Ifyes immunize and

investigate

' duster in time and space with same VDPV

If no investigate

AFP and polio roportincjf year-to-date (data received at WHO Geneva as of 03 December 2002)

2001 (as of 04 December 2001)

Non-polio

AFP rate

Adequate stool

specimens

Polio

confirmed cases

Wild polio

virus cases

Non-polio

AFP rate

Adequate stool

specimens

Polio

confirmed cases

African Region

2.9

39

10*

0

110

European Region

1.32

157

3**

2.9

0.98

2.25

83%

1.24

83%

1.53

1.19

2

178

1.17

South-East Asia Region

Western Pacific Region

1.63

84%

88%

1.46

0

329

1.2

Global total

72%

76%

84%

90%

84%

87%

82%

70

Region of the Americas

Eastern Mediterranean Region

1.79

85%

164*

0

99

0

1211

0

1474

1.81

178

0

418

93%

88%

Wild polio

virus cases

151

0

99

0

1211

0

1461

■ Vacdne derivedpolio virus. In 2001, in the American Region, in Dominican Republic 3 cases and in Haiti 2 cases.

In 2002, in the Alnun regton, in Madagascar, 4 cases

■' Importation ol wildpoliovirus into the region

Wild poliovirus map

I imolinC” total wild poliovirus and date of most recent wild

poliovirus by country as of 03 December 2002

03 December 2001 - 02 December 2002

.'..OSes

'

-v.. ■

■'■■V"-

........

..

------- '' 4,”

.i-r;'

3 _I

r

India

Pakistan

Nigeria

Egypt

Afghanistan

Somalia

Niger

1238

89

...................

145

4

9

4

4

,,

Seine: Data at WHOGeneva as ol 03 Deamber 2002

Importations

Zambia

*3

Most ream importation usesAms

* 2

• *-*i<**r.*TS4*i

Burkina Faso

1

as at date ol going tnprint

NIDs calendar for selected countries

Region

Country

AFRO

Cameroon__________

Central African Republic

Chad______________

Equatorial Guinea

Gabon_____________

EMRO

Nigeria_____________

Afghanistan_________

February 2003

Type of activity

Intervention

January 2003

Type of activity

Intervention

March 2003

Type of activity

Intervention

21-Jan/SNIDs ZOPV R°und2

21-JanZ NIDs ZOPV Round?

21-JanZ NIDs ZOPV R°und2

21-Jan Z NIDs ZOPV Round 2

21-JanZ NIDs ZOPV Round 2

25-JanZ NIDs ZOPV Round i

00-MarZ SNIDsZOPVRound?

00-MarZ SNIDs Z OPV «°und i

00-MarZ NIDsZOPVR^i

00-MarZ SNIDsZOPVRoundi

Egypt______________

Iraq_______________

Somalia____________

Pakistan____________

Yemen_____________

SEARO

OO-Feb/ MBs/OPV

i

28-JanZ SNIDsZOPVRoundi

OO-JanZ NIDsZOPVRound?

00-MarZ NIDsZOPVR°u"d2

03-MarZ NIDsZOPVRoundi

29-Mar/ NIDs/ OPV

Bangladesh_________

India______________

Maldives___________

05-JanZ NIDsZOPVR°undi

OO-JanZ SNIPsZOPV«°und2

Myanmar___________

Nepal______________

Thailand

12-JanZ NIDsZOPVRound?

Vit A

09-Feb/NIDs/OPV Round?

08-Feb/ NIDs/OPVRound 2

04-JanZ NIDsZOPVRqu^1

21-JanZ SNIDsZOPVRound?ZVitA

This calendar reflects information known to WHO/HQ at the time ofprint. Some NIDs dates are preliminary and may change; please contact WHO/HQ for up-to-date information.

□

f

News and announcements

Polio News [

Decern*. MB Q ggj (g) |

Dozens of US.Rotary club members help immunize

millions of children against polio in Africa

I

a

!

Ll

i

'1 !

Nigerian Rotarian immunizes a child in northern Nigeria. Ihis part of the country continues to

have the highest levels of transmission of wild poliovirus in Africa.

| N support of Rotary’s goal of a polio-free world

I by 2005, more than 150 Rotary members from

the United States flew across the Atlantic to

participate in national immunization days (NIDs)

in Ethiopia, Ghana and Nigeria in October and

November 2002. American Rotarians teamed up

'*Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF"

raises funds for polio

THE United States Fund for UNICEF is

i donating all the proceeds from its 52nd annual

“Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF” campaign to the

global effort to eradicate polio. Every 31 October

in the United States, kids dress up in celebration

of Halloween and go door-to-door to “Trick-orTreat” for sweets and funds for UNICEF. The US

Fund’s “Trick-or-Treat” for UNICEF anticipates

raising more than US$ 4 million, from the 2002

campaign, including US$ 850 000 from the

United Nations Foundation, and it was one of the

Fund’s most extensive efforts involving a record

number of corporate partners and distribution of

20 million donation boxes - more than four times

the number distributed in 2001.

GAVI breakout session on polio

“TTHE polio eradication programme has enhanced

i vaccine delivery systems and capacity in dozens

of countries with equipment, institutional

arrangements such as the laboratoiy network and

more than 2500 skilled people. Participants at the

November 2002 Partners’ meeting of the Global

Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) in

Dakar, Senegal joined a breakout session to discuss

the potential future roles of this polio infrastructure.

EPI managers from several countries including

Nigeria and Bangladesh noted the importance and

value of maintaining capacity to further strengthen

immunization services. The group recommended

that countries have a strong voice in determining

the best ways to ensure the polio infrastructure is

used to forward the GAVI objective of 80% routine

immunization coverage in 80% of districts in every

country. ♦

with their local counterparts to help with vaccine

delivery, volunteer recruitment and trans

portation, and community mobilization and

education. Seattle-based Rotary Club member

Ezra Teshome led 85 Rotary members to his home

country of Ethiopia. “It was moving to see the

families’ hope at the NIDs,” said Teshome. “Some

had walked for miles and miles to get their

children vaccinated.” Brad Howard of the

Oakland California Sunrise Rotary Club brought

34 Rotarians to Ghana. “Something like this

gives people the chance to make a difference one

person at a time,” he said. As the top private sector

contributor to polio eradication, Rotary has

given USS 182 million to eradicate polio on

the African continent and committed more than

USS 500 million worldwide. ♦

The Fund’s regional offices worked to educate

children and adults about polio and its ongoing

effects in the remaining endemic countries.

US mayors officially declared 31 October as

“Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF” day in 144

American cities. The campaign gave children in

schools, youth groups and clubs the chance to

help raise money for the Global Polio Eradication

Initiative, knowing that every dollar they collected

would help immunize children against polio. ♦

Photographer

.IjM Salgado- urges

support for Horn

of Africa polio

activities

O HOTOGRAPHER Sebastiao Salgado, who has

i worked tirelessly with polio partners to

document eradication efforts around the world,

made the case for support to polio activities in the

Horn of Africa at a Polio Partners’ meeting in

Nairobi in September. Salgado was the keynote

speaker at the gathering of partner agencies, donor

and country representatives, convened to address

the challenges in Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan.

Along with ensuring access in conflict-affected

areas and maintaining local political commitment,

securing the US$ 50 million required for polio

activities between 2003 and 2005 in the region

was considered the key challenge.

Ambassadors from Belgium, Ethiopia and the

United States, representatives from various

countries, international organizations, non

governmental organizations (NGOs), the US

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) and Rotary International participated in

this successful event. ♦

□

TCG Review

I Country focus I

SS

Pakistan ~ The model for

quality work

The November 2002 interim meeting of the

TCG reviewed eradication activities in the

remaining polio-endemic countries. The TCG

recognized progress in all countries and

singled Pakistan out for praise in particular.

However it had "grave concerns" about the

possibility of stopping transmission within

12 months in Egypt and India, Nigeria.

INCE 2000, Pakistan’s polio eradication

W programme has steadily improved. With

continued strong work it may be the first of the

remaining ’ high transmission” countries to stop

transmission. In contrast to Nigeria and India

where cases have increased five-fold in 2002, new

cases in Pakistan have declined by 10% and

transmission has been reduced significantly in the

traditional reservoir areas. The TCG emphasized

that Pakistan’s programme is strong overall, and

that success is due mainly to continued multiple

rounds of high-quality SIAs particularly in the

face of decreasing caseloads and virus lineages.

Other strong areas of the programme include the

careful analysis and use of surveillance data to

inform programme decisions and diligent follow

up of independent monitoring data prior to and

following SIAs. Government commitment is high

at national, provincial and, increasingly, district

levels. To stop transmission, the TCG endorsed

Pakistan’s SIA plans for four rounds of NIDs

and four rounds of subnational immunization

days (SNIDs) in 2003 along with the strategy to

concentrate on identified reservoir and high-risk

areas. ♦

TCG comparison of eradication activities in the three "high-transmission"

countries in 2002

Key activities

Pakistan

Nigeria

India

Number of rounds of

large-scale SIAs in 2002

4NIDs,4SNIDS

2NIDs, 4SNIDS

2NIDS, 1SNID

Management of

operations

Joint national/

international teams at

national, state and

substate levels

Joint national/

international teams at

national and state

levels

Joint national/

international

teams at national

level

Monitoring of SIA

quality

Independent 3" party

monitoring began in

early 2002

Independent

monitoring began in

late 2002

Independent

monitoring

began in late

2002

India - Wanted: higher

quality, quantity SIAs

| IISTORICALLY, India’s progress in polio

t i eradication has been unprecedented in the

world, with the virus circulation drastically reduced

from almost every district in the country to two

states in just a few years. The most progress

occurred in 1999-2000, when India undertook 10

national or subnational immunization campaigns

in a 24-month period. In contrast, only three largescale SIAs took place in 2001. The result? A five

fold increase in cases in 2002 (1211 at 4 December

2002) over 2001 (just 268 for the year). These cases

are primarily (75%) centred in Uttar Pradesh (UP)

- the major reservoir for polio in India and the

world. At year’s end, the area with the highest

transmission in western UP had reseeded many

other districts, including Gujarat and West Bengal

which had been free of endemic polio in 2001.

Data shows this major outbreak is the result of gaps

in the quality of immunization activities, and that

minority populations in western Uttar Pradesh are

the most severely affected by these gaps. The

Global TCG considers that India - the state of

Uttar Pradesh in particular - constitutes the

greatest risk to the achievement of global polio

eradication.

Moving forward, the TCG is recommending

an increased number of better quality SIA

rounds, including four rounds in the areas of highintensity transmission in the first half of 2003.

These must reach every child under five years of

age, particularly children in minority populations.

The TCG also recommends sufficient high-quality

staff to manage polio eradication at national, state

and substate levels, and the formation of substate

operational groups to manage polio eradication

activities across a number of districts, with the

support of partner agencies. ♦

Nigeria ~ political ownership

key

IB J HILE an increase in reported cases in 2002

wV (145 to date) over 2001 (56 total) is partly

due to improvements in surveillance quality,

transmission in several states of northern Nigeria

remains intense. Despite the increase, however,

cases have been geographically restricted, with just

seven states, all in northern Nigeria, reporting over

90% of cases, and two states, Kano and Kaduna,

with half of the total for the country. Virological

evidence demonstrates that many of the strains

causing disease in prior years are no longer

circulating, and there are a limited number of

strains remaining in circulation in 2002.

The TCG noted data showing that until very

recently most children under five years of age had

received insufficient (<3) doses of OPV in several of

the remaining endemic states. Although data from

the September SIAs indicate improvement, the

states of Kano and Kaduna in particular need to

ensure high-quality SIAs, as the current coverage

rates, while at 75-80%, are still too low to

interrupt transmission of wild poliovirus. The

TCG concurred with the national plan for three

rounds of high-quality SNIDs in the highest risk

states in the first half of 2003. The TCG also

emphasized that the high level of government

commitment at national level needed to be matched

at state and local government Area levels. ♦

CONC:-

□

Resource mobilization

Recent donations:1

.7-

Polio firmly on the agenda

for Africa-Europe discussions

USS 32 million for 2003-2005 polio eradication

activities in Africa

| N the final communique of the Second Africa-Europe

I Ministerial meeting held in Ouagadougou, Burkina

Faso in November, African Foreign Affairs ministers

noted the significant progress made toward polio eradi

cation in Africa and called on European Union Member

States to mobilize adequate funds to finish the job.

The inclusion of polio eradication in the

Ouagadougou communique sets the stage for polio erad

ication to be discussed at the European Union-African

Union Summit in April and for Polio Advocacy Group

follow up with European governments for additional

funding for polio eradication in Africa. ♦

Aventis

Pasteor

donates

30 million

doses of

polio

vaccine

° _9

1¥

i

i

David Williams, CEO of Aventis Pasteur, signed on for

the final push to eradicate polio during a ceremony

with WHO Director-General Gro Harlem Brundtland

and UNICEF's Executive Director Carol Bellamy at the

UN Seaetariat in New York in November 2002.

A

S West African countries launched a massive co

ordinated effort to immunize 60 million children

against polio, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer,

Aventis Pasteur, donated 30 million doses of oral polio

vaccine to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. The

donation - the third by Aventis Pasteur - is valued at

USS 3 million, and makes Aventis Pasteur the longeststanding corporate partner of the Initiative.

Materials available:

The report of the November 2002 interim meeting of the Global Technical

Consultative Group for poliomyelitis eradication is available electronically in English.

US$ 3 million worth of oral polio vaccine for

2002-2005 in Africa

USS 9.6 million for oral polio vaccine in Pakistan

USS 14.5 million for 2002-2003 polio activities in

key countries and regions, including India, Nigeria

and Pakistan

USS 100 000 for polio activities in EMR0 countries

USS 8.2 million for oral polio vaccine and

surveillance activities in Bangladesh in 2003-2004

USS 27.4 million in global funding, with a focus on

Africa, and for activities in Nepal

"’J - -u?,'-

'

’

The Aventis Pasteur donation is already making a

difference, with almost 3 of the 30 million doses

earmarked for November’s polio immunization

campaign in Liberia.

At a recent signing ceremony attended by

David J. Williams, President and Chief Executive

Officer of Aventis Pasteur, Gro Harlem Brundtland,

Director-General of WHO and Carol Bellamy,

Executive Director of UNICEF, Mr Williams signed a

banner pledging Aventis’s commitment to end polio.

“The Initiative has already made tremendous

progress and we admire the remarkable work done by

WHO, Rotary International, CDC, UNICEF and

millions of volunteers around the world,” Williams

said. “This donation is just one example of Aventis

Pasteur’s commitment. We are very proud of our

involvement with the Global Polio Eradication

Initiative.” ♦

Forthcoming events 2003

Date

Event

Venue

20-28 January

4-6 February

WHO Executive Board

Geneva, Switzerland

25-27 March

Rotary IPPC meeting

AFRO Regional Certification Committee

24-25 April

Global TCG

Evanston, USA

Yaounde, Cameroon

Geneva, Switzerland

The Progress2001 (WHO/POLIO/02.08) report is now available in French.

To register to receive Polio News, either in print or by email, or to receive any of the items above, email:

poliocpi&who.int or call +4122 7912657.

mm

< U Polio News

Manypolio documents are available on the web site at:

www.polioeradication.org

i---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1

| Please fill out tltit respoasf' coupon anti return it to Polit> News, £Pl, Deftartment ot

i Vaccines and tiialogicais, Docuntent Centre, iNnrld Health Organiiation. CH-1211

i Geneva 21, if you wt>ulii Hht) to cartlinuv receivirttj this publication.

*

i

j 7 would like to receive this publication regularly.

[ Name:

I

] Institution:

; EWorld Health Organization 2002.

; All rights reserved. The designations emptayed and the presentation of the material in

: this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the

j World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or

of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on

maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement

I

i Address:

The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this

publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result

of its use. Polio News is published quarterly by EPI, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Swntzerland,

and part funded by USAID. Published data reflects information available at time of print

! Please also send this publication to:

i

| Name:

All comments and feedback on Polio News should be sent to:

Department of Vaccines and Biologicals, WHO, Geneva.

i

| Institution:

.

Tel.:

[ Address:

i=-

J

Fax:

Email:

Web site:

+41227913219

+41 227914193

polioepi@>who.int

http://www.polioeradication.org

I

i

WHO

Rotary and CDC special edition (see pages

.

Supplementary immunization

in polio-free areas

Greatly missed:

DrTaky Gaafar

Page 2

Page 6

European Region certified polio-free

P OR some 870 million people living in the 51 Member

i States of the European Region of the World Health ’

Organization (WHO), June 2002 heralded the most

important public health milestone of the new millennium.

The historic decision to certify the Region polio-free was

announced at a meeting of the European Regional

Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis

Eradication (RCC) in Copenhagen on 21 June. Certification

of the Region, which stretches from Iceland to Tajikistan and

includes the Russian Federation, confirms the potency and

transferability of polio eradication strategies.

The European Region has been free of indigenous

poliomyelitis for over three years, in the presence of

certification-standard surveillance. The region’s last case

caused by an indigenous wild poliovirus occurred in eastern

Turkey in November 1998, when a two-year-old

unvaccinated boy was paralysed.

Poliovirus imported from polio-endemic countries

remains a threat to the region. In 2001 alone, there were

three polio cases among Roma children in Bulgaria and one

non-paralytic case in Georgia, all caused by poliovirus

originating in south Asia. At the certification meeting,

Sir Joseph Smith, Chairman of the RCC cautioned that,

“ Throughout the European Region, ongoing vaccination and

surveillance is vital. The risk ofpoliovirus being imported into

Europe will continue until we eradicate polio globally.”

m

f'KI

I

iJ

■

1

i

!

Coordinated national immunization campaigns, known as Operation MECACAR, were instrumental in achieving

a polio-free European Region. MECACAR involved 18 polio-endemic countries and areas in the European and

Eastern Mediterranean Regions of WHO.The synchronization of immunization among neighbouring countries

has become a model for eradicating the disease globally.

—- r’

unierf

A Newsletterfor the Global Polio Eradication Initiative

Department of Vaccines & Biologicak

World Health Organization

in association with Rotary International,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

and the United Nations Children's Fund

Historic milestone \

<

’ '

‘

R

V

&

■e

0'

e>

SWi’ f-

•

u /T7

WW

® Certified polio-free

/

Not yet certified polio-free

Certification of the European Region means over half the

countries of the world -115 countries and areas - are now

certified polio-free. The European Region is the third of the

six WHO regions to be certified - the Americas and the

Western Pacific were certified in 1994 and 2000 respectively.

"To get where we are today required

the full commitment and

cooperation of each of our

51 Member States, the hard work of

public health workers in the field and

the firm support of international

partners in coordination with WHO."

DrMarcDanzon

WHO Regional Director for Europe

21 June 2002

In addition to maintaining high

immunization coverage, surveillance and

the ability to respond to imported cases,

European countries are now cataloguing

all laboratory stocks of poliovirus as part of the global plan

to ensure effective containment in a polio-free world. ♦

G8 leaders commit to raising

funds to eradicate polio by 2005

ft. FRICA was a centrepiece of this year's G8 Summit,

Jb held on 26-27 June in Kananaskis, Canada. With the

Africa Action Plan, G8 leaders responded to the

New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD)

launched by African leaders last year. Health is one of

the components of the plan, and polio was prominently

featured. Jean Chretien, Prime Minister of Canada and

G8 Summit Chairperson, summarized the

outcomes of G8 discussions: “In addition to

our ongoing commitments to combat (other

diseases), we committed to provide sufficient

resources to eradicate polio by 2005”. ♦

See back page for further details on the G8 pledges.

i

! Technical tips j

Supplementary immunization

in polio-free areas

EVEN the risk of spread of imported wild

B w polioviruses (importations occurred into

Bulgaria, Georgia and Zambia in 2001 alone),

the Global Technical Consultative Group (TCG) on

Polio Eradication has re-evaluated the role of

supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) in poliofree areas. The TCG decided that it is important

polio-free areas continue to use periodic national

immunization days (NIDs) or extensive sub-national

immunization days (SNIDs) to maintain population

immunity. The occurrence of the recent vaccinederived poliovirus outbreaks in the presence of low

population immunity (Hispaniola, Madagascar,

Philippines — see box) provides further argument for

achieving and sustaining high immunization coverage,

ideally through routine immunization services.

Consequently, the seventh meeting of the Global

TCG recommended:

■ Polio-free countries which border endemic areas, or have

very low immunization coverage, should continue

to conduct NIDs or SNIDs, as appropriate, on an

annual basis.

Polio compatible cases

Surveillance for acute flaccidparalysis (AFP) in Madagascar has detected a cluster

of four cases of paralytic poliomyelitis from which type-2 vaccine-derived

polioviruses have been isolated. Preliminary data indicate that these patients,

residing in the Tolagnaro district of Toliara province in southeastern Madagascar,

had onset ofparalysis between 20 March and 12 April 2002. None ofthe children

affected was fully vaccinated. Vaccination coverage data suggest that during

1999,37% ofchildren aged under one year had received three doses of OPV. The

genetic sequencing studies on these viruses are compatible with an outbreak of

paralyticpolio due to a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV).

In July, a joint mission by the Ministry of Health, the Pasteur Institute of

Madagascar, WHO and UNICEF in Madagascar recommended that countrywide

NIDs be undertaken in September and October 2002, using a door-to-door

strategy. Further NIDs are planned in spring 2003, after the rainy season, in

Toliara and other districts at risk ofpoliovirus transmission.

To read the WER/MMWR report, visit

www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5128a5.htm

■ Countries which have been polio-free for at least three

years, but have not achieved or maintained a level of

'2l90% routine immunization of infants with OPV

(OPV3 coverage), should continue to conduct NIDs

at least every three years, to prevent the

accumulation of susceptibles and protect against the

importation of wild polioviruses. In larger countries,

where appropriate, SNIDs should be conducted to

cover those states or provinces with lower than 90%

coverage. ♦

Reported polio compatible cases in 2002*

ECOGNIZING the high number of

polio compatible cases reported

II W in 2001, ar its seventh meeting

the Global TCG reaffirmed its

recommen-dations that all countries

a

D

should maximize efforts to obtain two

adequate specimens from every acute

flaccid paralysis (AFP) case,

J

prioritize investigation and follow

up of cases with inadequate jgp

specimens, and ensure all

potentially compatible cases are ® BMffl

referred to an appropriately

trained expert group for classification within 90 days of onset.

At this stage of the Global Polio

Eradication Initiative, the careful analysis of

|

data on polio-compatible cases is critical. Polio|

compatible cases should be monitored and B

mapped at least monthly, with field

1

investigations of all compatible cases, including

’

active case search, with particular attention to

clusters of cases. Data on polio compatible cases

should be used to identify areas for improving

surveillance quality and areas at risk of wild

poliovirus circulation. ♦

J £>

o

a

® Polio compatible case

BB Endemic region

* Data from 1 January 2002-5 September 2002

See Polio News Issue 12, July 2001 and Issue

Febnuiry 2002, respectively, [or further information on classifying AFP cases

and the role of expert groups for case classification; see the TCG’s full recommendations on polio-compatible cases in the seventh

meeting report. For electronic copies please contact polioepi@iuho.int or Tel: +41 22 791 3219-

□

AFP and polio reporting year-to-date comparison of 2001-2002

2002(as of 10$

2001 (as of 10 September 2001)

Non-polio Adequate stool

AFP rate

specimens

Confirmed

polio cases

Wild polio

virus cases

Pending

cases

Non-polio Adequate stool

specimens

AFP rate

r2002)_____________]

Confirmed

polio cases

Wild polio

virus cases

Pending

cases

African Region

2.80

71%

159

17

780

106

1.11

77%

9*

0

456

2.80

0.93

83%

Region of the Americas

90%

0

92

0

395

Eastern Mediterranean Region 1.90

83%

80

49

511

2.14

88%

41

41

413

European Region

1.12

82%

2**

2

252

1.32

83%

0

0

384

South-East Asia Region

1.41

84%

76

1443

1.43

85%

407

407

1626

Western Pacific Region

1.19

87%

0

1 030

1.19

87%

Global total

138

81%

144

4472

1.70

85%

76

0

327

554

N/A

__2

349

540

3167

• Vaccine derived poliovirus

** Importation of wild poliovirus

Wild poliovirus map

total wild poliovirus and date of most recent

wild poliovirus by country from 10 Sep 2001

to 09 Sep 2002

10-Sept-2001 to 10-Sept-2002

2OO1

Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jut

India

X

'.

|

Pakistan^

.... - ‘ . 540

'.

93

Afghanistan Fl .

•

6

'W '

I.:-.

l\J

' >' •■■■

Nigeria

119

.'k <.

Somalia >

Egypt

importation

(

•

Wild virus type 1

r

•

Wild virus type 3

•

....................

•

...... -

- ----

‘ ' 5

2

Source: Dalo al WHO Gtnm as o< 10 September 2002

Date of/mooned cases/virus

Importations

Zambia

, y

Algeria

Wild virus type 1 and 3

Endemic countries

NIDs calendar for selected countries

Region

Country

AFRO

Central African Republic

Oct 2002

Type of activity

Intervention

Nov 2002

Type of activity

Intervention

17-Dec/NIDs/0PV“VVitA

Chad

9-Nov/ SHIDs/OPV

17-Dec/ NIDs/OPV“ Wit A

2-Nov/ NIDs/OPV“VVitA

21-Dec/NIDs/OPV “z

17-Dec/ NIDs/OPV“WitA

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

EMRO

SEARO

Dec 2002

Type of activity

Intervention

6-Dec/ NIDs/OPV“WitA

Ethiopia

25-Oct/NIDs/OPV

Madagascar

30-0ct/HiDs/OPV“2

West African Block* & Nigeria

5-Oct/ NIDs/OPV“WitA

Afghanistan

22-0ct/ NIDs/OPV“4

Egypt________

1-Oct/ NIDs/OPV^111

Somalia

1-Oct/SNIDs/0PV“3

Sudan

29-Oct/NIDs/OPVRound’

Southern Sudan

**7-0ct/ SNIDs/OPV“s

Pakistan

23-Oct/ NIQs/OPVRounri4

9-Nov/ NIDs/OPV

17-Dec/SNIDs/OPVRound}

l-Nov/NIDs/OPVfi’^i

16-Dec/MDs/0PV“2

4-Nov/ SNBs/OPV Round 6

17-Nov/ SNIDs/OPV “2

India

*The West African Block is Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Cdte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.

This calendar reflects information known to WH0/HQ at the time ofprint. Some NIDs dates are preliminary and may change; please contact WH0/HQ for up-to-date information.

**At time ofprint, the Southern Sudan SNIDs were suspended due to flight restrictions.

o

Spearheading partners:

Rotary International

Gates Foundation

how much can be accomplished when a group selflessly

uses every ounce of the political capital at its disposal to

recognizes Rotary for its

improve the health of the worlds poorest children.”

As the world’s first and one of the largest

critical advocacy role

humanitarian service organizations with 1.2 million

U OTARY’S efforts to

kU eradicate polio were

recently honoured with the

US$ 1 million 2002 Gates

Award for Global Health

| from the Bill & Melinda

I Gates Foundation.

During the award

| ceremony on 30 May, Bill

I Gates Sr, President of

the

Foundation

said,

“What has been achieved

since Rotary International

Luis Vicente Giay, Chairman of the Rotary

Foundation of Rotary International, receives the

courageously committed

Gates award from Bill Gates Senior, President of

the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

to eradicate polio defies

description. Every time we see a world leader

administering polio vaccine to a child, or hear about a

war being stopped somewhere so children can

---- be

__

vaccinated, we can thank Rotary for demonstrating

I

nF

I

members, Rotary is the lead private sector contributor

and volunteer arm of the global partnership dedicated

to eradicating polio.

In 1985, Rotary created PolioPlus — a programme

to immunize all children against polio by Rotary’s

100th anniversary in 2005. To date, Rotary has

committed more than US$ 493 million to the

protection of two billion children in 122 countries.

In addition, Rotary’s Polio Eradication Advocacy

Task Force has played a major role in decisions by

donor governments to contribute over US$ 1.5 billion

to the effort. This year, in an effort to help close the

funding gap, Rotary is embarking on its second

membership fundraising drive, entitled Fulfilling Our

Promise: Eradicate Polio,, with the goal of raising an

additional US$ 80 million for polio eradication. Rotary

and the United Nations Foundation are also

collaborating in a joint appeal for funding from private

corporations, foundations and philanthropists to help

secure urgently needed funds by the end of 2002. ♦

. .. ________________ ^.1

Rotary recognizes polio An international profile

eradicatfQ^gfepions'

ft S part of its ongolng^-advocacy efforts, Rotary

>> publicly recognizes world leaders who have

made outstanding contributions to global polio

4 eradication. Eveline Herfkens, the former

Minister for Development Cooperation of the

Netherlands, was presented with the Polio

Eradication Champion Award on 7 May 2002, by

Luis Vicente Giay, Chairman of the Rotary

Foundation of Rotary International, for her

leadership in securing US$ 110 million in

contributions from the Netherlands Government

to support polio eradication.

Rotary also presented key members of

Congress in the United States with the Polio

Eradication Champion Award on 15 May 2002,

acknowledging their ongoing support of the polio

eradication initiative. In the 2002 fiscal year,

Congress appropriated US$ 129-9 million to the

global polio eradication effort. First time

recipients of the award include: Senator Richard J.

Durbin, (D-IL), Rep. Maurice D. Hinchey

(D-NY), Rep. Benjamin Gilman (R-NY), Rep.

Mark Steven Kirk (R-IL), Rep. John Peterson (RPA), and Rep. Michael McNulty (D-NY). Past

recipients were also honoured for their continued

support. Other leaders who have been honoured

with this award include the former United States

President William Jefferson Clinton, former

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Rt. Hon.

John Major, First Lady of Egypt Mrs Suzanne

Mubarak and UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

At Rotary's Convention, Wane

Annan, the lawyer and artist

married to UN Secretary-General

Kofi Annan, spoke on "The

Importance of Volunteers in

Today's World." Following her

address, Rotary International

President Richard King and

Chairman of the Rotary

Foundation Luis Vicente Giay

presented her with the Rotary

Award for Humanitarian Service.

Photo: Rotary International

ORE than 18 000 Rotary club members from

I w I 125 countries gathered in Barcelona for Rotary’s annual

convention this June. Despite their different political, cultural,

and historical backgrounds, a common mission united

Rotarians: promoting peace and building better communities.

The convention included a focus on worldwide health and

polio eradication, where Rotary club members shared best

practices of working with governments and other

nongovernmental organizations. The convention included the

election ofthefollowing new Rotary leaders:

■ Bhichai Rattakul of Thailand took office as the new

President of Rotary International on 1 July 2002. A

Member of Parliament for nine terms since 1969 and

Leader of the Democrat Party, he has served his country

as Foreign Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Speaker of

the House of Representatives and President,-xof the

Parliament.

\

■ Glen W. Kinross of Australia is the new Chairman of The

Rotary Foundation of Rotary International. As .a member

of the International PolioPlus Committee, Mr. Kinross is

■■

dedicated to the global effort to eradicate polio.

El

1

W-.

Spearheading partners:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDC technical partner in polio eradication

f'J

£

Deborah Moore microbiologist examines cultures for the presence of poliovirus at the CDC polio laboratory

in Atlanta, United States.

■f" HE Atlanta-based US Centers for Disease Control

I and Prevention (CDC) has been a spearheading

partner in the global polio eradication initiative since

1988. CDC’s niche in the initiative lies in its technical

support and funding for large supplies of oral polio

vaccine (OPV) and operational costs for mass

immunization campaigns.

CDC is perhaps best known for its wide-ranging

technical support. For example, the poliovirus

laboratory at CDC functions as one of the global

specialized laboratories in the polio laboratory

network. Among the four spearheading partners, CDC

____

■

/

'

works as the “virus detective,” using its state-of-the-art

virological surveillance expertise,

or genetic

fingerprinting, to identify the strain of poliovirus

involved in an outbreak and pinpoint its exact

geographical location and origin. Each year CDC

scientists at the polio laboratory test more than

6000 specimens and isolates from around the world.

CDC also assigns short- and long-term technical

experts to WHO and UNICEF offices worldwide to

provide epidemiologic, programmatic, and managerial

assistance to support surveillance and polio immu

nization campaigns in developing countries. These

include members of the Stop Transmission of Polio

(STOP) teams since 1999 (see below) and public

health scientists who analyse surveillance data and

investigate outbreaks of polio, especially in areas within

or bordering polio-free zones. Most recently, CDC staff

members have conducted polio outbreak investigations

in Bulgaria and the Philippines.

In addition, CDC is one of the major funders for the

purchase of OPV used in supplementary immunization

campaigns such as NIDs. In the fiscal years of

2001 and 2002, CDC contributed approximately

US$ 115 million through UNICEF for this purpose.

CDC also provides technical resources to assure that the

purchased vaccine is targeted to achieve polio eradication

objectives. ♦

__________________

- HEALTWfEft « PSOPLE "

STOP programme: providing field support where it's

needed most

a

UR job is to help strengthen surveillance

networks for polio ... we have to know where

the disease is and where it isn’t, and we have to move

fast. Its the most exciting job I’ve ever done,” wrote a

member of the first Stop team sent from CDC in 1999.

This captures the essence of what the STOP

programme is all about: rapidly deploying human

resources to the field to support national polio

eradication programmes.

Based on the model used by smallpox eradication

teams in the 1960s and 1970s, STOP team members

collaborate with local and national counterparts from

the Ministry of Health, WHO, and UNICEF. Their

duties include:

■ supporting, conducting, and evaluating active

surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP);

■ assisting with polio case investigations and follow

up, and

■ assisting with planning, implementing, and

evaluating supplemental immunization activities,

including house-to-house mop-up operations.

Each day is different. Team members may work

with local religious leaders to overcome community

rumours about the safety of OPV; train traditional

healers about AFP surveillance; hire a boat to a remote

island to investigate a suspected polio case; or give a

presentation to health officials on immunization

campaign coverage.

In partnership with WHO and Rotaiy, CDC

launched the programme in 1999, ind since then has

deployed 11 teams, comprising 386 members, to

34 countries. Prior to leaving for their three-month

assignments, participants; receive one week of training

conducted by CDC and WHO staff in Atlanta. The

partnership that supports STOP has expanded from

WHO, Rotary, UNICEF and CDC to also include the

Canadian Public Health Association.

Perhaps one of the best tributes to the programme

is the fact that after completing their field assignments,

one in four team members have continued to work in

polio eradication with CDC, WHO or UNICEF.

To learn more about the STOP programme, the qualifications

sought, and hou> to apply, visit

httptHwww. cdc.gov/nip/global/default. htrn

s

News and announcements

Canada supports NIDs in Nigeria

As part of the social mobilization effort in preparation of the forthcoming NIDs, Mme Chretien, the

First Lady of Canada, and Mrs Danjuma (representing Mrs Stella Obasanjo, who was attending the

Cote d’Ivoire meeting of First Ladies) arrive at the Bamishi village in the area council of Kuje near

Abuja on 5 April to attend a polio immunization session.This advocacy event coincided with the visit

of the Prime Minister of Canada, Jean Chretien, to Nigeria.

phDfo: © UNICEF/Noble Tholari

De Beers

flying for polio eradication

Obituaries

Dr Taky Gaafar, Regional Adviser, Vaccine Preventable Diseases and

Immunization (VPI), and Coordinator, Disease Surveillance Eradication and

Elimination in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean (EMR) Office, passed away

on 4 July in Cairo. Dr Gaafar was first associated with WHO as short-term

consultant in smallpox eradication in Bangladesh in 1975 and in Somalia

(1979-1981). Dr Gaafar had a long association with Alexandria University,

latterly as a Professor in the Department of Public Health, Faculty of

Medicine from 1985 —1994. He actively tookpart in a number of WHO EMR

activities during this time, including national/interregional training courses,

intercountry workshops and indepth programme reviews. Dr Gaafar became

Regional Adviser, VPI at WHO EMR office in January 1995. He will be sorely

missed by all those who had the privilege and pleasure of working with him.

Abdi Risak Mahmed Farah, laboratory technician working for WHO

in Somalia as Regional Polio Eradication Officer for Mudug Region, was

tragically killed in a car accident on 5 May on his way back to his wife and

children from a monthly meeting. His organizing skills and openness,

transcending clan dimensions, had been the single most important factor in

bringing NIDs to as many children as possible in this otherwise hard-toreach area. His relentless effort in detecting AFP cases made a difference

within his first few months with the programme. Working in Mudug Region

is particularly challenging, as its regional town ofGalkayo is the geographic

centre of war-torn Somalia. Abdi Risak is greatly missed by his family, his

colleagues, his community and the programme.

Dr Sekou Victor Sangare, former Expanded Programme on

Immunization (EPI) Manager ofCote d'Ivoire, passed away on 14 June in

Abidjan. Having left EPI management around two years ago,

Dr Sangare undertook several assignments for the Vaccine Preventable

Diseases department at the WHO Africa office as a consultant; his last

assignment was a mission to the Gambia and Guinea in February2002.

He will be much missed.

Suzanne Spencer, Head of Information and Communication at De Beers, doing a wing walk for her

Day of Hope challenge, through which she raised over £1000 (around US$ 1500) for the Global

Polio Eradication Initiative. Seen here on the top wing of a 1940 Boeing Stearman Bi-plane,

Suzanne was wearing £100 000 (around US$ 150 000) of diamonds to gain publicity and raise

awareness for the global bid to eradicate polio.

photo @ BeefS

Bruno Cor be, recent consultant to WHO in Goma, the Democratic

Republic of the Congo, and long-time member ofstaff with Medecins Sans

Frontieres (MSF), died on 11 March in Martillac, France. Mr Corbe joined MSF

in 1986, going to Sudan and Mozambique as a logistical expert, then to Iraq,

Somalia, Afghanistan and Angola. Later at MSF headquarters, hejoined

missions to Bosnia, Chechnya, Rwanda and Kivu. In 1987 he launched the

MSF-Logistics central purchasing offices in Lezignan. In 1993, he was

appointed Logistics Director at MSF's Brussels headquarters and later, a

member of the MSF-France Board of Directors and the MSF-Belgium Board.

"The influence of his work and personality are indelibly stamped on the

history of MSF"

Worid Press Photo award winner:

polio eradication in Eritrea

"Polio in the press"

i.'..

1

;

Hews media

• Europe declared polio-free but cash shortage hampers rest ofthe world Agence France Presse (21.06.02)

• Silent polio carrier highlights risk - Georgina Kenyon, BBC Online (22.07.02) *

• Polio casein Burkina Faso - BBC Online (30.07.02)

Scientific articles

• Chemical Synthesis ofPoliovirus cDNA: Generation ofInfectious Virus in the

Absence of Natural Template - Jeronimo Cello, Aniko V. Paul, and Eckard

Wimmer, Science (11.07.02) *

• Public Health Dispatch: Poliomyelitis - Madagascar, 2002 - Morbidity and

Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) (19.07.02)

For copies ofthese and other recent articles, please contactpoljoepi@who.int or

Tel: + 41 22 7913219

• *The implications ofthese aspects ofthe risk assessment for post-certification immunization

policyforpolio will be covered in the December edition ofPolio News.

Photographer Stefan Boness won an award in the 'science and technology' category of the World

Press Photo awards for his portrayal of a young girl receiving polio vaccine at a health station in

the village of Dresa in Western Eritrea, taken in December 2001.

Photo© Stefan Boness/lpon

British Airways 'Change for Good'

donation funds Zambia NIDs

RITISH AIRWAYS (BA) staff travelled to Zambia at the end of July

to observe the country’s recent SNIDs and mop-up campaigns.

A US$ 700 000 donation from BA’s Change for Good/UNICEF

fundraising partnership provided all of the OPV and social mobilization

requirements for the July round.

High quality supplementary immunization activities were essential to ensure

that virus from the five polio cases found in Zambia in 2001-2002, all importations

from eastern Angola, did not reestablish poliovirus transmission in the country.

Zambia’s SNIDs aimed to reach at least 1 million children under the age of five.

§

The BA team observed the campaign at close quarters from the country’s

Ndola (Copperbelt) region. Gaining hands-on experience administering OPV to I

©

children, the team also joined vaccinators in the region’s door-to-door campaign. s

£

Later, the imponance of cross-border campaigns was underlined when the team

In Chililabombwe, a town in Zambia’s Copperbelt region on the

travelled to the Zambia/Democratic Republic of the Congo border to observe

country's border with the DRC,the tiny fingernail of a newborn baby i

joint immunization activity between the two countries.

covered with harmless gentian-violet paint to indicate that she has

been vaccinated against polio.Zambia's July SNIDS, funded by BA's

Since 1994 BA’s ‘Change for Good’ campaign has raised more than

Change for Good programme, reached over a million children.

US$ 16 million in support of UNICEF programmes around the world. ♦

1

I

Cease-fires pave the way for direct access to children

5',-

EASE-FIRES in two of the ten countries considered

polio-endemic at the outset of 2002 have resulted in

OPV reaching many children who had likely never

been vaccinated before.

SUDAN: Some parts of the remote Nuba mountains,

located in the central part of war-ravaged Sudan, have been

inaccessible by direct UN humanitarian relief operations in

the region for decades. As a result of a cease-fire signed on

19 May 2002, Initiative partners have been able to gain

direct access to some areas for the first time, successfully

completing three rounds of

polio SNIDs in the Nuba

region. Almost immediately

following the cease-fire, WHO,

in partnership with UNICEF,

seized the opportunity to

launch

the

immunization

campaign, despite difficult

logistics. Landmines severely

hampered the movement of

vaccination teams, and the

mountainous terrain and lack

Photos: WH0/P. Blanc

of roads meant that teams frequently had to walk for over

ten hours a day and climb steep mountain slopes in severe

heat to access remote villages. In the villages themselves,

where there is a dearth of education and health

infrastructure, social mobilization efforts had to be

intensified in order to explain the threat of polio and the

reasons for the campaigns. Despite the difficulties, an

average of 45 000 children were reached in each round.

ANGOLA: The April cease-fire in Angola has led to similar

success for polio eradication, providing the opportunity to

vaccinate hundreds of thousands of children who had been

unreachable for years due to the conflict. The discovery of

Angolan children with polio paralysis just across the border in

Zambia in late 2001 demonstrated the reality of wild virus

transmission in eastern Angola. At that time, the possibility of

conducting successful immunization activities in the east was

not assured. However, the 4 April ceasefire opened the

formerly inaccessible areas, allowing SNIDs and mop-up

campaigns in April and May. For the June and July NIDs,

logistical support from the army, nongovernmental

organizations and about 30 000 volunteers meant children in

150 newly-accessible municipalities, 37 “quartering and

family areas” and children in internally displaced persons

camps were vaccinated against polio. In total, close to

4.5 million children were reached in Angola during the

June round, and the final round of NIDs took place in

late August - all synchronized with neighbouring countries.

The knowledge provided by this ‘direct access’ to

inaccessible populations in both Sudan and Angola has a

major impact on the confidence of the polio status of each

country. To date, Sudan has not isolated a wild poliovirus

since April 2001. Angola’s last recorded virus was in

September 2001, though the recent importations to Zambia

suggest that transmission is ongoing in eastern Angola. With

continued access and strong AFP surveillance, these countries

can reach the goal of being polio-free by the end of 2002. ♦

Recent donations.-* ■

Resource mobilization

DeBeers staff members:

European certification and

G8 commitment provide

backdrop for enhanced

resource mobilization efforts

US$ 5000 of undesignated funds, allocated to Guinea Bissau for

operational costs

LL levels of the polio partnership are actively

working to address the Initiative's most critical

issue: filling the US$ 275 million funding gap.

On 21 June, as the European region of WHO

was certified polio-free, WHO's Director-General,

Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, wrote an exceptional

appeal to all European development ministers, citing

the necessity of an extraordinary show of support for

polio eradication in order to reach the goal of a poliofree world — therefore protecting the collective

investment already made by the European region.

At the June 2002 G8 Summit in Kananaskis,

Canada, G8 leaders pledged to fill the Global Polio

Eradication Initiative's US$ 275 million funding gap

as part of the Africa Action Plan. The partnership is

now working with G8 member states to help to

operationalize this pledge. At the Summit, Canada

pledged US$ 32 million in new funding over three

years. Canada and the UK, which has since committed

an additional US$ 25 million, are now preparing to

advocate with the other G8 countries. A meeting of the

Africa Personal Representatives of the G8 leaders

towards the end of this year will be the crucial forum

for translating the G8 pledges into actual resources. ♦

This autumn, the document'Estimated external financial resource

requirements for 2003-2005' will be published. It will summarize the

global resource requirements and highlight the budget needs for all

endemic countries and countries at high risk of wild poliovirus

transmission - providing the basis for resource mobilization efforts.

Materials available:

A

The polio eradication Progress Report 2001 is available

in English in print and electronic format.

The first edition of the polio eradication endgame

I

briefing pack is available in English and French - it is |

also available electronically on

/

USS 32 000 raised throug

US$ 10.5 million to purchase OPV for Bangladesh, Ethiopia,

Ghana, India, Nigeria and Sudan

7

I

I .

GZ.

www.polioeradication.org

Hew Zealand:

US$ 43 000 contributed to the Rotary Foundation to support

activities in Indonesia

Norway:

US$ 6.8 million in undesignated funding to the global

programme

SSI''.

Private Sector Appeal:

us$ 1.7 million for polio activities in Angola and the Democratic

Republic of the Congo as well as support for CDCs STOP team

programme

US$ 3.75 million in private sector campaign donations from

Wyeth, Baxter, Tellabs and Pew Charitable Trust for polio

activities in Ethiopia, India, West Africa and for the African Polio

Laboratory Network

' '

Trickor Treat:

US$ 3.4 million for polio activities in Pakistan and Afghanistan,

which attracted a US$ 850 000 match from the UN Foundation

United Kingdom:

US$ 7.8 million in undesignated funding

'll

the Global Polio piod^tia^TsUoihe expresses irsgiatmude to alldonots.

^Donations annauntjedsince Mine's JSMay2^2,

Wyeth donates US$ 1 million

to Global Polio Laboratory

Network

\

n

is

Photo: WHO

Dr Gro

right) joined Jack Blane, director of the Rotary's Polio

Eradication Private Sector Campaign (middle right), in

Geneva this June at a ceremony where US-based

pharmaceutical company Wyeth pledged

US$ 1 million to polio eradication.

Tommy Thompson, United States Secretary of Health and

Human

Services

(far

Human Services (far left)

left) looked

looked on'as

on as Kevin

Kevin Reilly,

Reilly,

President ofWyeth Vaccines and Nutrition (middle left)

presented the contribution to the Polio Eradication

Private Sector Campaign (jointly sponsored by The Rotary

Fmindatinn

Foundation nf

of Dntarv

Rotary IntamaftAnal

International nnJ

and fka

the IbG+aJ

United

Nations Foundation).The gift will support the African

Region of the Global Polio Laboratory Network in their

efforts to identify the last reservoirs of wild poliovirus.

As part of Wyeth's commitment to the Initiative, now

spanning six years, this is the company's second

US$ 1 million contribution to support the Global Polio

Laboratory Network.

Forthcoming events 2002

Date

Event

21-22 September Rotary International Meeting of National Advocacy Advisors

25 September

Horn of Africa Polio Partners'meeting

7-11 October

Meeting of Interested Parties

22-24 October

Rotary IPPC Meeting

11 & 15 November Global Polio Management Team Meeting

12 November

WHO/UNICEF MoH Consultation for Priority Countries

13-14 November Meeting of the Global TCG

25-29 November Pan American Health Organization

Special Centennial Meeting on Vaccines

2-5 December

Task Force on Immunization

Venue

Zurich, Switzerland

Nairobi, Kenya

Geneva, Switzerland

Evanston, US'

Geneva, Swi

j

Geneva, Switzerland

Geneva, Switzerland

Washington DC, USA

Abuja, Nigeria

Many polio documents are available on the web site at:

www.polioeradication. org

• Please fill out this response coupon and return it to Polio News, EPI, Department of

i Vaccines and Bialogkals, Document Centre, World Health Organization, CH-1211

| Geneva 22, if you would like to continue receiving this publication or

■ send an e-mail to polioepi^who.int

i / would like to receive this publication regularly.

I Name:

I Institution:

| Address:

i

1

'

World Health Organization 2002.

All rights reserved.The designations employed and the presentation of the material in

this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the

World Health Organlxation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, dty or area or

of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on

maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this

publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result

of its use. Polio News is published quarterly by EPI, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland,

and part funded by USAID. Published data reflects information available at time of print.

i Please aha send this puhlicutiou to:

i Name:

I Institution:

i Address:

;

All comments and feedback on Polio News should be sent to:

Department of Vaccines and Biologicals, WHO, Geneva.

§

Tel.:

4-4122791 3219

I

Fax:

4-4122791 4193

Email:

polioepi@who.int

3

Web site:

http://www.polioeradication.org

_____________

ill

I

o

BMC Public Health

BioMed Central

Open Access

Research article

Polio eradication initiative in Africa: influence on other infectious

disease surveillance development

Peter Nsubuga*1, Sharon McDonnell1, Bradley Perkins2, Roland Sutter3,

Linda Quick3, Mark White1, Stephen Cochi3 and Mac Otten3'4

Address:1 Division of International Health, Epidemiology Program Office, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA,

2Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center of Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia,

USA, 3Vaccine Preventable Disease Eradication Division, National Immunization Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta,

Georgia, USA and 4Regional Office for Africa, World Health Organization, Harare, Zimbabwe

Email: Peter Nsubuga* - pnsubuga@cdc.gov; Sharon McDonnell - semO@cdc.gov; Bradley Perkins - bap4@cdc.gov;

Roland Sutter - rsutter@cdc.gov; Linda Quick - maq2@cdc.gov; Mark White - mhwl@cdc.gov; Stephen Cochi - scochi@cdc.gov;

Mac Otten - ottenm@whoafr.org

* Corresponding author

Received: 17 September 2002

Accepted: 27 December 2002

Published: 27 December 2002

B/VIC Public Health 2002, 2:27

This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.eom/l47l-2458/2/27

© 2002 Nsubuga et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article: verbatim copying and redistribution of this article are permitted in all

media for any purpose, provided this notice is preserved along with the article's original URL

Abstract

Background: The World Health Organization (WHO) and partners are collaborating to

eradicate poliomyelitis. To monitor progress, countries perform surveillance for acute flaccid

paralysis (AFP)- The WHO African Regional Office (WHO-AFRO) and the U.S Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention are also involved in strengthening infectious disease surveillance and

response in Africa. We assessed whether polio-eradication initiative resources are used in the

s.uryeillance for and response to other infectious diseases in Africa,

Methods:

During October

I999-March

——

2000, we developed and

—

administered a survey

questionnaire to at least one key informant from the 38 countries that regularly report on polio

activities to WHO. The key informants included WHO-AFRO staff assigned to the countries and

Ministry of Health personnel.

Results: We obtained responses from 32 (84%) of the 38 countries. Thirty-one (97%) of the 32

countries had designated surveillance officers for AFP surveillance, and 25 (78%) used the AFP

Resources for the surveillance and response to other infection^

In 28 (87%) countries, AFP

program staff combined detection for AFP and other infectious diseases. Fourteen countries (44%)

had used the AFP laboratory specimen transportation system to transport specimens to confirm

other infectious disease outbreaks. The- majority pf thv-^evntnor thnr poQormpd AFP surveillance

adequately (i.e., non polio AFP rate = 1/100,000 children aged <15 years) in 1999 had added 1—5,

diseases to their AFP surveillance prograrn.

Conclusions: Despite concerns regarding the targeted nature of AFP surveillance, it is partially

integrated into existing surveillance and respnn^ ^rpips in multiple African countries. Resources

provided for polio eradication should be used to improve surveillance for and response to other

priority infectious diseases in Africa.

Page 1 of 6

(page number not for citation purposes)

BMC Public Health 2002, 2

Background

The polio-eradication initiative has led to the largest in

flux of public health resources into Africa since the small

pox-eradication campaign, comprising both human

resources and infrastructure investment [1,2]. Public

health professionals have debated the merits and demerits

of the polio-eradication initiative, regarding the priorities

of developing countries. Supporters of the initiative have

reported on the high benefit-cost ratio of eradication

[1,2]. Among the demerits cited is that polio has a lower

public health importance as compared to other infectious

diseases - many of them epidemic prone - in poor coun

tries [1-3]. An investigation of the impact of the polio

eradication initiative on the status of funding for routine

immunization revealed that the amount of funding for

routine immunization activities has not increased over

the years and that whether eradication funding will be

available for other public health interventions when polio

is eradicated is unclear [4). Anecdotally reported merits

and benefits of the polio-eradication initiative have in

cluded increased national enthusiasm and funding for Ex

panded Programs

on

Immunization,

enhanced

surveillance capacity for other diseases, strengthened pub

lic health laboratory capacity, and improved epidemio

logic skills [2]. We report the results of a survey regarding

the impact of the polio-eradication initiative on the sur

veillance for other infectious diseases in Africa.

In 1989, the African Regional Office of the World Health

Organization (WHO-AFRO) adopted the global goal of

eradicating».poliomyelitis by the year 2000, and in 1995,

member countries initiated specific polio-eradication