RF_COM_H_103_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

RF_COM_H_103_SUDHA

3

■E

I

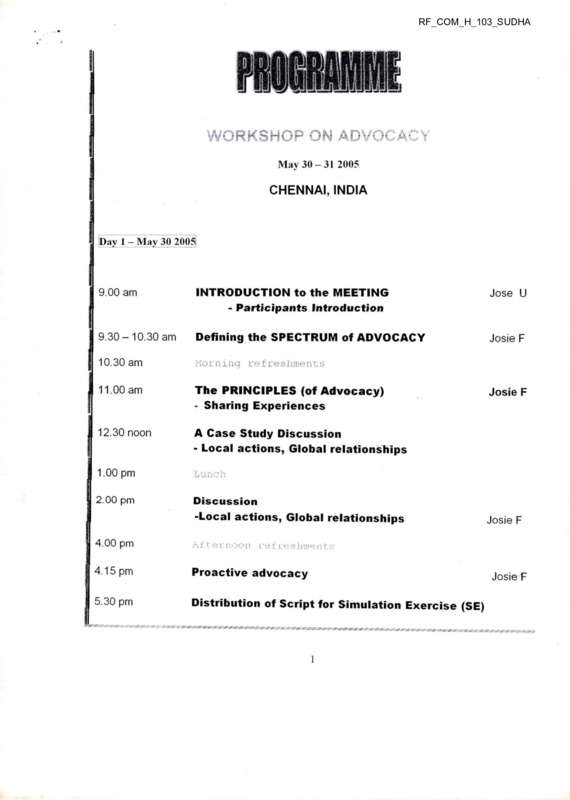

WORKSHOP ON ADVOCACY

May 30-31 2005

CHENNAI, INDIA

Day 1-May 30 2005!

9.00 am

INTRODUCTION to the MEETING

- Participants Introduction

Jose U

9.30 -10.30 am

Defining the SPECTRUM of ADVOCACY

Josie F

10.30 am

Morning re fres hments

11.00 am

The PRINCIPLES (of Advocacy)

Josie F

- Sharing Experiences

12.30 noon

A Case Study Discussion

- Local actions, Global relationships

1.00 pm

Lunch

2.00 pm

Discussion

-Local actions, Global relationships

4.00 pm

A .t t e r n < y o n r e f l e s 11 ip e n t s

4.15 pm

Proactive advocacy

Josie F

Josie F

5.30 pm

1

I

After Dinner

Participants prepare for Simulation Exercise

t Dav 2 May 31 2005

i

8.45 am

Reflection of Program on May 30 2005

9.00 am 10.30 am

Film - Roll Back on Malaria in Tanzania &

Nienke &

Discussion on campaign strategies from the film Josie

10.30-11.00 am

Mor ain a re fres hme nt

11.00 am

Going Glo-Cal: Trials & Triumphs

11.45 - 12.30p.m

Lessons learnt

12.45- 1.00 pm

Critique of national plans

1.00 - 2.00 pm

Lunch

2.00 - 3.15 pm

Simulation Exercise (SE)

3.15-4.00 pm

Jury’s Verdict on SE & Discussion

4.00 pm

A f t e r noo n re f r e s bine nt s

4.30-4.45 pm

Critique of International plans

4.45 - 6.00 p.m

Planning your Campaign (what will You Do Differently?)

Josie F

2

Josie

WEMOS ADVOCACY TRAINING

CHENNAI - MAY 20 - 31 2005

A Case for Simulation Exercise on Advocacy

Nolambi has been devastated by severe tropical storms, political instability and

corruption. Poverty is on the rise. Unemployment is high. Diseases such as malaria and

gastroenteritis are on the increase. Drug addiction poses a serious threat. More cases of

sexually transmitted diseases have been reported after Nolambi opened its beautiful

beaches for tourism. Recently the Ministry of Health warned that an Aids epidemic is

imminent.

For the 35 million Nolambians the situation could not be worse. With the closure of

several companies and a government strapped of cash, young people are leaving the

country in search of employment.

On August 28 2004, Mr Desmond Ali the president of National Organization for People’s

Rights (NOPR), an NGO noticed a news item in the Daily Star on a Public Private

Partnership. The article highlighted that a TNC, Aster Zen will provide pro bono

expertise and resources to develop several health centres and improve water supply and

sanitation. The TNC will provide essential medicines to the poor. The paper added that

“the project brings together like minded people from developed and developing

countries “The project is poised to take action with all stakeholders

l,The PPP will contribute to poverty reduction, employment, better health, empowerment

of women, regeneration of the environment

The news item upset Mr Desmond Ali as he and others in the NGO community were in

the dark about the PPP. He needed to know more. The NGOs are always the last to

know, he said pointing the article to his colleague.

He called a friend in the Economic Planting Unit of the Prime Minister’s office to enquire

further on the PPP news item. The friend provided him some critical information. A

steering committee on the PPP had been set up. It comprised of government officials.

Aster Zen representatives, National Council for Women ^fev-^headed by the Prime

Minister’s wife);\ representatives from WHO, Harvard Centre for International

Development and the National University.

In the course of the conversation with his friend, Mr Desmond Ali learnt that the PPP was

in line with the government’s ambitious 5-year Plan which will witness the privatization

of the health sector, water and higher education.

Mr Desmond Ali and his colleagues swung into action. They mobilized several NGOs,

local politicians and opinion leaders from the community to demand from the

government greater transparency and accountability about the PPP.

The government wanted to avoid a conflict before the PPP could be implemented. It

announced that a meeting would be held with all stakeholders of the PPP and NGOs were

invited. In an unusual move, the government said the media would be present too. The

action surprised many people as Nolambi has a restrictive media environment.

NOPR made several attempts to get more information from NCW, WHO and the

University. All referred NOPR to the government.

■

This case is written by Josie for the WEMOS Advocacy Training Chennai May 2005

Instruction for Participants '.

You will be divided into 4 groups representing:

1) Government

2) Aster Zen

3) WHO

4) NGOs

> Each group is to prepare its case, position, concerns for the meeting on 31st May 2005

at 2.00 pm and advocate its position on the proposed PPP

y>c>S(

•^s

Qin nounCfl

LoQ

NolQroKi

IT.

3*j,. r/)is>s>/c<n z

ho u r><J cck oO

i-|e_cxJLH-)

7 "4

<o

oJj

j r<A onrc)\J <2 A

AJOjCi h')h^<A

I

>-UO

G. ?>\j t-

WG0^. kJ

Cblgzvb' fex(fk jg^^. /

OohAafe^ Ti/s^

(iXSe^ /p;

pex T'Ho^^S Rjp

tO'V’c

cl-pccA)

A A^te< ^g/«^riL

- Le^peasOT• fHfe

<

*

I

(

>

Global Public-Private Partnerships

in Health

Workshop, 30 May- 3 June 2005, Chennai, India

May 2005

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

Contents

Logistics

1. Programme

5

7

1.1. Monday 30 May 2005

7

1.2 Tuesday 31 May 2005

8

1.3 Wednesday 1 June 2005

9

1.4 Thursday 2 June 2005

10

Friday 3 June 2005

11

1.5

2 Consultants

Annex 1

Planning workshop Kenya 2004

Annex 2, 30-31 May training

Annex 3, 1-2 June

3/5

12

13

13

14

16

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

Logistics

Arrival in Chennai

You will be picked up at the airport.

Accomodation

The workshop will be held at:

Hotel Breeze

850, Poonamallee High Road

Chennai-600 010.

Tel :91-44-2641 3334-37

Fax: 91-44-2641 33 01

For more details about the hotel please check their website;

www.breezehotel.com

Contactperson India

Techno Economic Studies and Training Foundation

Mrs. Daisy Dharmaraj

Angie Dare (tel: 0091449840378494)

No. 4 Sathalavar Street

Chennai

India

E-mail: testfoundation@rediffmail.com

E-mail: daremarcusanqie@hotmaii.com

Tel: +91 9 4440 14170

Contactperson the Netherlands

Wemos

Jose Utrera and Geja Roosjen

P.O Box 1693

1000 BR Amsterdam

E-mail: lose. utrera@wemos. nl

E-mail: qeia.roosien@wemos.nl

Tel: +31 20 4352050

5/7

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

1. Programme

1.1. Monday 30 May 2005

By Josie Fernandez

Objectives of Monday 30 May and Tuesday 31 May

1. The participants on the workshop have increased their knowledge on the principles

of good campaigning (advocacy and lobby activities) making use of their own work

experiences.

2. The participants on the workshop have reflected on the application of good

campaigning for the advocacy and lobby activities on GPPIs in health of their

organisations at national level.

3. The participants on the workshop have reflected on the application of good

campaigning for the advocacy and lobby activities on GPPIs in health for the joint

activities of the group at international level.

4. The participants have discussed the contents of the film about Roll Back Malaria in

Tanzania and have discussed and agreed on the possible uses of the film at

national and international levels

5. The group of participants have gained knowledge and skills on linking national and

international campaigns based on concrete working experiences.

6. The group of participants have reflected, discussed and get conclusions on strategic

elements to be taken into account to improve the planning and implementation of

their organisations’ campaigns at national level; and to be included in the planning

and execution of joint campaign activities at international level.

See Annex 2 for background information.

09:00

Introduction of Participants

09:30

Defining the SPECTRUM of ADVOCACY

10:30

Morning refreshments

11:00

The PRINCIPLES (of Advocacy)

12:00

A Case Study Discussion

13:00

Lunch

14:00

Critique of National Action Plans

16:00

Afternoon Refreshments

16:15

Critique of International Plans

17:30

Distribution of Script for Simulation Exercise (SE)

after dinner

participants prepare for simulation

7/9

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

1.2 Tuesday 31 May 2005

By Josie Fernandez

08:45

Reflection of Program on 30th May 2005

09:00

Film Roll Back Malaria in Tanzania’ and discussion on campaign strategies

from the film

10:30

Morning refreshments

11:00

Going Glo-Cal: Trials & Triumphs

12:30

A case study discussion

13:00

Lunch

Simulation Exercise (SE)

15:15

Jury’s Verdict on SE & Discussion

16:00

Afternoon Refreshments

16:30

Planning Your Campaign (What Will You Do Differently?)

8/10

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

1.3 Wednesday 1 June 2005

By Domingos Armani

Objectives of Wednesday 1 June and Thursday 2 June

1.

Evaluation and get lessons learned about the process of collaboration between

Wemos and the other partner organisations and between Southern organisations on

the issue of GPPIs.

2.

Reflection on the points to be taken into account for the last period of the

collaborative work on the issue of GPPIs.

Evaluation and get lessons learned about the outcomes of the collaborative work on

the issue of GPPIs

3.

See Annex 3 for background information.

$

08:00

Opening, presentations & expectations, programme & methodology.

08:30

Introduction - “Evaluation as a learning tool”.

09:00

Evaluation of Phase I - Defining the problem and framing case studies

10:30

Morning refreshments

14:00

Evaluation of Phase II - Doing the case studies

9/11

May 2005

Global Pubfic Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

1.4 Thursday 2 June 2005

By Domingos Armani

08:00

Evaluation of Phase III - Developing advocacy initiatives

10:30

Morning refreshments

11:00

Evaluation of Phase III - Developing advocacy initiatives

13:00

Lunch

14:00

Evaluation of Phase III - Developing advocacy initiatives

16:30

Phase IV - Identifying challenges and relevant questions for planning

19:00

Evaluation of the workshop and closure.

10/12

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

1.5 Friday 3 June 2005

8.30

Reflection on relevant points from workshops about advocacy and

evaluation

9.15

Main advocacy activities of each participating organization

Every organization presents the main objectives and planned activities for

2005

10.15

Break

10.45

Planning joint activities at international level

12.00

Perspectives of collaboration after 2005

12.30

Evaluation

13.00

Closing remarks and farewell

11/13

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

2 Consultants

Mr. Domingos Armani is a sociologist with a degree in Political Science. He is a professor

of the University of the Valley of the River of Sinos (UNISINOS) and the director of Darmani

Consultancy - Development & Citizenship. Mr. Armani works as a consultant in social

development since 1997. He has long experience in conducting the participatory processes

with Civil Society Organizations (social NGOs, movements, philanthropic organizations,

social organizations of churches, etc.), public agencies (public companies, state secretaries,

etc.) and with international institutions. Recently he concentrated his work on institutional

evaluation, strategic planning, formulation of monitoring- and evaluation systems, institutional

development of organizations of the civil society and elaboration and management of social

projects.

Mrs. Josie Fernandez holds a master in Development Management. She is the founder and

Executive President of the of Education and Research Association for Consumers. She now

works as a consultant for the Goverment of Malaysia, FAO, ESCAP, UNDP, Federation of

Malaysia Consumer Associations and Trade Unions.

12/14

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

May 2005

Annex 1

Planning workshop Kenya 2004

Activity___________

1. finalization of case

studies

WHO

All

participants

Period________________________ Remarks

Draft report half June: Daisy,

Laxonie, Thelma, George, Sylvester,

Mwajuma

Final report half July

Draft report half July: Ashnie

Final report end of July: Ashnie

Finished in October

2. finalization of the

report with summary and

analyses of the case

studies

Consultant

Mike

3. Evaluation of

advocacy process

Wemos

Spring 2005

4. Communication on

who has been where through group mail

Wemos

Continuing

5. Report of the seminar

April Nairobi

Wemos

End of May

Rawson

(Medact)

PLANNING OF ACTIVITIES LOBBY AND ADVOCACY

Activity

WHO__

Period______

1. Write a proposal for

lobby and advocacy

All

Beginning of August

2. Write guidelines for

lobby proposal______

Wemos

participants

13/15

Beglming of June

Remarks

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships m Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

Annex 2, 30-31 May training

Background Work for Chennai Training, 30 & 31 May 2005

Dear participants,

When I went through your case studies and experiences vis a vis GPPIs, I picked up the

following problems, which I believe will be the areas of focus for your advocacy, campaign

and lobby efforts.

Do some brainstorming and outline a strategy to find solutions to the concerns and problems.

Problems

k

Challenges

Lack of transparency

programs due to

inaccessibility to

information

CSOs have no control

over programs.

Government is decision

maker

GPPIs, based on

government focus

Concept of GPPI not

understood

Inequalities and

irregularities in

disbursement of funds

Success of PPI based

on amount of funds not

on health outcomes

Program bias in GPPIs

14/16

Recommendation for

Advocacy Action /

intervention

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

Annex 3,1-2 June

WORKSHOP on EVALUATION of EXPERIENCES and LESSONS LEARNED

on GPPIs

Chennai, 1 -2 June 2005

Objectives

The workshop aims at evaluating the outcomes so far and the collaborative work between

the organizations involved in the process as well as drawing lessons learned in order to plan

the next period of activities.

Methodology

The workshop will be developed as a participative and reflexive space/process, where

everybody will have the opportunity to express their views and proposals in an atmosphere

of reflection and learning. The methodology should be able to lead to build commitment and

shared responsibility upon a genuine democratic and participative process.

Throughout the workshop, we will take into consideration different ambits of the discussionthe person, the organization, the country and the whole coalition on GPPIs.

The proposed methodology organizes the debate in four distinct phases, in order to get the

most of the evaluation: Phase I - Involvement in the coalition, defining the problem, framing

the case studies; Phase II - doing the case studies; Phase III - carrying out advocacy

initiatives, and Phase IV - identifying challenges for the next phase.

In each phase, we shall do the evaluation and draw lessons learned oriented by key

questions emerging from the following dimensions: concrete outcomes, process of

collaboration, and capacity building.

We will follow the same methodological steps in the evaluation of Phase I, II and III:

Presentation of guiding questions (on outcomes, capacity building and

process of collaboration)

Individual reflection (or by each organization)

Collective debate

Synthesis of evaluation and lessons learned

In the Phase IV we shall work upon the lessons learned in Phases I, II and III to identify

challenges and questions to be taken into account in the planning process (especially on

joint international advocacy activities, advocacy at country level and strengthening capacities

of participant organizations).

Key-questions for debate (preliminary)

PHASE I - Defining the problem

On outcomes:

■ Were the definition of the problem and the framing of the case study developed

satisfactorily?

■ What could have been better?

16/18

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

On capacity building:

■

What were the most relevant skills and expertise obtained?

On the process of collaboration:

■

■

■

■

■

Did the collaboration from Wemos fulfill the needs on the definition of the problem

and of the building of the frame of the case studies?

Was the collaboration between the participant organizations and between them and

Wemos on this stage taken as an opportunity for the strengthening of the network?

Were any problems of this stage well handled?

What could have been better?

What the participant organizations have learned about the process of collaboration

on this stage?

PHASE II - Carrying out the case studies

On outcomes:

■

■

■

How do we evaluate the quality of the research produced?

How do we evaluate the quality of the advocacy documents produced?

What relevant changes have been produced as a result of the implementation of the

case studies?

On capacity building:

■

■

■

What were the most relevant skills obtained (planning, implementation and analysis

of research for advocacy, etc.)?

What were the most relevant experiences / expertise obtained (international health

policies, international and national health policy actors, international and national

health programmes, national health policy processes, etc.)?

Were there any capacity building opportunities missed at this stage?

On the process of collaboration:

■

■

■

■

Did the collaboration from Wemos for the realization of the case studies satisfy the

expectations and needs? (why?)

Was the collaboration between the organizations carrying out the case studies

satisfactory? (why?)

Were any problems on this stage well handled?

What could have been better?

What the participant organizations have learned about the process of collaboration

on this stage?

PHASE III - Developing advocacy initiatives

On outcomes:

■

■

■

■

■

■

How do we evaluate the quality and usefulness of the materials (leaflets, etc.) and

documents produced?

How do we evaluate the advocacy activities organized?

How do we evaluate the advocacy activities organized around case studies?

Was the process of informing relevant actors and decision markers about GRPIs

adequately developed?

Was the process of informing CSOs and making them aware of GPPIs programmes,

risks and drawbacks adequately developed?

How do we evaluate the process of contacting/forming coalition or networks to work

on GPPI or related issues?

How do we evaluate the changes or processes initiated to bring changes in policies

around GPPIs?

On capacity building:

17/19

May 2005

-

■

■

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

What were the most relevant skills, capacities and experiences obtained (definition

and implementation of advocacy activities at the national and international levels;

influencing policies of national and international actors in health; etc.)?

What were the most relevant experiences / expertise obtained (international health

policies, international and national health policy actors, international and national

health programmes, national health policy processes, etc.)?

Were there any capacity building opportunities missed at this stage?

On the process of collaboration:

■

■

■

•

■

■

■

How do we evaluate the collaboration from Wemos with regard to the definition of

advocacy activities at country and international levels?

How do we evaluate the collaboration from Wemos with regard to the realization of

advocacy activities at country and international levels?

How do we evaluate the collaboration between the participant organizations with

regard to the definition of advocacy activities at country and international levels?

How do we evaluate the collaboration between the participant organizations with

regard to the realization of advocacy activities at country and international levels?

Were any problems on this stage well handled?

What could have been better?

What the participant organizations have learned about the process of collaboration

on this stage?

Preparation work by participants

It is expected that the participants in the workshop bring some reflection upon the key

questions listed above, which will be complemented in the workshop.

The participants should also read the paper on “evaluation as a learning tool”, which serves

as an introduction to the methodology of the workshop.

18/20

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

“Learning through Evaluation”

Domingos Armani

This brief paper was written as an introduction to the Chennai evaluation workshop on the

GPPIs advocacy process.

The paper sets out to argue that all evaluation should be a learning process, presenting

some methodological principles to make it happen.

Evaluation as a learning process is here defined as a methodically organised collective

process of evaluation based on experience, guided by a set of critical questions and

presided overby the sense that learning is a vital conditional for effective social change.

Such an evaluation process promotes the critical analysis of the experience - individual,

organisational and collective - confronting it with visions, expectations, objectives and

outcomes, in order to produce a methodologically sound and socially relevant new

knowledge which systematises the main findings and lessons learned.

It is important to point out that development evaluation has not always meant a process of

learning. Unfortunately, evaluation within the development wisdom, in the North as well as in

the South, has all too often been taken in a rather “beaurocratic” and instrumental fashion,

whereby planning, monitoring and evaluation went around a set of pre-defined results,

outcomes and indicators, allowing little space for open and critical thinking about the factors

which could explain success or failure in complex processes of social change.

Monitoring and evaluation in this sense are closer to “auditing” tools rather than to a learning

experience.

It is strategic to promote evaluation as a learning process because: (i) it contributes to

balance the “results based” kind of evaluation, in which products, results and concrete

outcomes are what really matters and not the rather more intangible experiences and

learning about the process of development itself; (ii) it helps to overcome the traditional

“linear approach” of much of development projects evaluation, whereby social processes of

change are perceived and designed as a simple chain of cause-and-effect, and not as a

complex and simultaneous set of multidetermined changes; (iii) it helps to overcome the

activism and the institutional resistance in many organisations of the South with regard to the

development of a culture of evaluation as institutional learning, and finally because (iv) to

promote “evaluation as learning” is the entrance door to any socially strategic action.

Any initiative of “evaluation as learning” should be developed in accordance with the

following principles:

♦

The evaluation should be conceived, organised and conducted as a process of

critical reflection based on key-questions;

♦

The evaluation should use participative working techniques in order to strengthen

ownership;

♦

The evaluation process should allow the emergence of and be able to deal with all

relevant concerns, doubts, criticism, visions, proposals and tensions;

♦

The process should take into account the power relations which structure the group

in question, in order to stimulate and favour equitable participation, considering all

participants as “citizens” of an evaluative “public sphere”;

♦

The evaluation process should be able to promote agreements and, whenever

possible, valid consensus;

19/21

May 2005

Global Public Private Partnerships in Health

Workshop, 30 May-3 June, Chennai, India

♦

The process should look at and take into account both tangible and intangible

outcomes;

♦

The process should value both individual, organisational and collective experiences

of learning, and

♦

A more focused process of evaluation leads to deeper learning.

Thus, the evaluation of the GRPI advocacy network should be carried out as a process of

“evaluation as learning” in order to get the most of the experience so far and to strengthen

the planning for the coming period.

For that to happen, some specific guidelines are proposed:

The evaluation has to consider different stages of the experience - defining the

problem and framing the case studies, implementing case studies and carrying out

advocacy initiatives;

The process will systematise evaluation and lessons learned at three dimensions of

the experience, outcomes, capacity building and the process of collaboration.

♦

The learning has to be valued in individual, organisational and coalition terms;

♦

The methodology should strengthen the sense of ownership and commitment of the

participant organisations over the evaluation in order to empower the network itself;

♦

The discussion in the workshop will be guided by a set of key-questions for

reflection, and

The evaluation and lessons learned shall be inputs for the planning of the next

period.

Porto Alegre

May 2005

20/22

30RAP200434

June 2004

“Global Public Private Initiatives in Health, Research

for lobby and advocacy”

Annex 6. Causes, consequences,

solutions

Problem: Increasing influence of Private sector at global level = GPPIs_____________

Causes

Consequences

Solutions (through

advocacy and lobby

actions)

- Inequalities grow

- Poverty -related diseases

- Poverty increases

are increasing

- Economical policy reforms

- Less resources for health

- Diminishing role of

- Private sector increasing role

governments

in health

- Governments take less their

- Health as commodity

responsibilities for social

- Less attention to right to

problems (corruption, another

health

priorities)

- Short term / technical

- Market as solution of

solutions

problems

- Donors increase resources

- Increasing power of TNG

for vertical programmes

- Diminishing credibility of

- Less attention to structural

WHO - getting less

solutions

resources

- Less attention to equity

- Less resources for

strengthening of health

systems

-WHO looks for resources of

private sector - partnerships

- Increasing number of PPPs

- WHO role as moral authority

/ normative institution

diminished

- Conflict of interests

- Lack of transparency

36/49

30RAP200434

June 2004

"Global Public Private Initiatives in Health, Research

for lobby and advocacy”

Annex 7. Summary important items

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

R

J

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

1

2

3

4

5

Promote South-South solidarity

Technologies and skills in Southern countries should not be hindered.

GPPI should not introduce new medicines when they are not needed.

Demand transparency and democracy and diminishing of corruption / and to

take responsibility of social problems.

Have strong laws sustaining health policies.

Industries should be held accountable.

Information on GPPIs should be publicised.

WHO should be revitalised ***.

People’s movement should be strengthened.

Root causes of health should be addressed **.

Augmenting self-reliance **.

Increase local capacity of health systems for sustainability **.

Challenge TNC to change attitudes **, pay social tax.

Increase awareness on the right to health and the obligation of the states to

promote, protect and fulfil it. Access to health care.

Demand universal basic income grant.

Altering market system.

Develop powerful and accountant mechanisms.

More research on GPPIs.

Altering market systems/challenge TNC’s

WHO revitalisation

People’s movement strengthening (networks)

Address root cuss of health problems

Increase local capacity of health systems / self-reliance

]•

37/49

30RAP200434

"Globa! Public Private Initiatives in Health, Research

for lobby and advocacy”

June 2004

Annex 8. Criteria for ranking issues

- Result in a real improvement of people’s life

- Result in better health for all, specially vulnerable groups and poor

- Fulfillment of the right to health

I

- Be widely supported

I

- Match in international / national agenda

- Promote sustainable improvement of health

- Look for solutions of the root causes of illnesses

- Promote integral solutions to health problems

I

- Improve access to health services for all

- Promote and facilitate participation

I

- Empower people

r

- Improve accountability to the public

- Strength national health systems

- Help to develop local resources

- Facilitate regulation of private sector

38/49

30RAP200434

“Global Public Private Initiatives in Health, Research

for lobby and advocacy”

June 2004

Annex 9. Checklist for choosing an

issue

CHECKLIST FOR CHOOSING AN ISSUE

Criteria

The solution of an

National level

Issue 2

Issue 1

issue should be

- Result in a real

improvement of

people’s life

- Result in better

health for all,

specially

vulnerable groups

and poor

- Fulfillment of the

right to health

- Be widely

supported

- Match with

international /

national agenda

- Promote

sustainable

improvement of

health

- Look for solutions

of the root causes

of illnesses

- Promote integral

solutions to health

problems

39/49

Issue 3

Issue 4

Issue 5

30RAP200434

“Global Public Private Initiatives in Health, Research

for lobby and advocacy”

June 2004

- Improve access

to health services

for all

- Promote and

facilitate

participation

- Empower people

- Improve

accountability to

the public

- Strength national

health systems

- Support the

development local

resources

- Help to develop

local resources

- Promote increase

of resources for

health

- Facilitate

regulation of

private sector

Other

Other

40/49

1

WORKSHOP on EVALUATION of EXPERIENCES and LESSONS LEARNED

on GPPIs

Chennai, 1 -2 June 2005

Objectives

The workshop aims at evaluating the outcomes so far and the collaborative work

between the organizations involved in the process as well as drawing lessons learned

in order to plan the next period of activities.

Methodology

The workshop will be developed as a participative and reflexive space/process, where

everybody will have the opportunity to express their views and proposals in an

atmosphere of reflection and learning. The methodology should be able to lead to

build commitment and shared responsibility upon a genuine democratic and

participative process.

Throughout the workshop, we will take into consideration different ambits of the

discussion - the person, the organization, the country and the whole coalition on

GPPIs.

The proposed methodology organizes the debate in four distinct phases, in order to get

the most of the evaluation: Phase I - Involvement in the coalition, defining the

problem, framing the case studies; Phase II - doing the case studies; Phase III

carrying out advocacy initiatives, and Phase IV - identifying challenges for the next

phase.

In each phase, we shall do the evaluation and draw lessons learned oriented by key

questions emerging from the following dimensions: concrete outcomes, process of

collaboration, and capacity building.

We will follow the same methodological steps in the evaluation of Phase I, II and III.

-

Presentation of guiding questions (on outcomes, capacity building

and process of collaboration)

Individual reflection (or by each organization)

Collecti ve debate

Synthesis of evaluation and lessons learned

In the Phase IV we shall work upon the lessons learned in Phases I, II and III to

identify challenges and questions to be taken into account in the planning process

(especially on joint international advocacy activities, advocacy at country level and

strengthening capacities ofparticipant organizations).

Key-questions for debate (preliminary)

PHASE I - Defining the problem

On outcomes:

■ Were the definition of the problem and the framing of the case study

developed satisfactorily?

■ What could have been better?

On capacity building:

2

■

What were the most relevant skills and expertise obtained?

On the process of collaboration:

Did the collaboration from Wemos fulfill the needs on the definition of the

problem and of the building of the frame of the case studies?

■ Was the collaboration between the participant organizations and between them

and Wemos on this stage taken as an opportunity for the strengthening of the

network?

■ Were any problems of this stage well handled?

■ What could have been better?

■ What the participant organizations have learned about the process of

collaboration on this stage?

■

PHASE II - Carrying out the case studies

On outcomes:

■

■

■

I low do we evaluate the quality of the research produced?

How do we evaluate the quality of the advocacy documents produced?

What relevant changes have been produced as a result of the implementation

of the case studies?

On capacity building:

What were the most relevant skills obtained (planning, implementation and

analysis of research for advocacy, etc.)?

■ What were the most relevant experiences / expertise obtained (international

health policies, international and national health policy actors, international

and national health programmes, national health policy processes, etc.)?

■ Were there any capacity building opportunities missed at this stage?

■

On the process ofcollaboration:

Did the collaboration from Wemos for the realization of the case studies

satisfy the expectations and needs? (why?)

■ Was the collaboration between the organizations carrying out the case studies

satisfactoiy? (why?)

■ Were any problems on this stage well handled?

■ What could have been better?

■ What the participant organizations have learned about the process of

collaboration on this stage?

■

PHASE III - Developing advocacy initiatives

On outcomes:

I low do we evaluate the quality and usefulness of the materials (leaflets, etc.)

and documents produced?

■ How do we evaluate the advocacy activities organized?

■ How do we evaluate the advocacy activities organized around case studies?

■ Was the process of informing relevant actors and decision markers about

GPPIs adequately developed?

■ Was the process of informing CSOs and making them aware of GPPIs

programmes, risks and drawbacks adequately developed?

■

7

How do we evaluate the process of contacting Tonning coalition or networks

to work on GPPI or related issues?

■ How do we evaluate the changes or processes initiated to bring changes in

policies around GPPIs?

3

On capacity building:

■ What were the most relevant skills, capacities and experiences obtained

(definition and implementation of advocacy activities at the national and

international levels; influencing policies of national and international actors in

health; etc.)?

■ What were the most relevant experiences / expertise obtained (international

health policies, international and national health policy actors, international

and national health programmes, national health policy processes, etc.)?

■ Were there any capacity building opportunities missed at this stage?

On the process ofcollaboration:

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

How do we evaluate the collaboration from Wemos with regard to the

definition of advocacy activities at country and international levels?

How do we evaluate the collaboration from Wemos with regard to the

realization of advocacy activities at country and international levels?

How do we evaluate the collaboration between the participant organizations

with regard to the definition of advocacy activities at country and international

levels?

How do we evaluate the collaboration between the participant organizations

with regard to the realization of advocacy activities at country and

international levels?

Were any problems on this stage well handled?

What could have been better?

What the participant organizations have learned about the process of

collaboration on this stage?

Preparation work by participants

It is expected that the participants in the workshop bring some reflection upon the

key-questions listed above, which will be complemented in the workshop.

The participants should also read the paper on “evaluation as a learning tool”, which

serves as an introduction to the methodology of the workshop.

Case study for discussion for Chennai 1 raining 05

What the Poor Themselves can do to Achieve Access to Healthcare

Actions for access to health for the disadvantaged consumers:

I. Information and education

Based on these findings. Association Senegalaise pour la Defense de I’Environ-nement et des

Consommateurs (ASDEC) a Cl member in Senegal, conducted a senes of information an

XaSSons on “How to access safe drugs and healthcare services” with consumers in

the disadvantaged areas in the suburbs of Dakar.

The discussions at these sessions were aimed at infonnmg ASDEC members and the

community on the Bamako Initiative, a strategy promoting the use of essential generic drugs

made accessible to the great majority of people at affordable prices. The policy is unknown to

most patients. Resource persons who include doctors were part of the pane introducing the

topic and answering questions from the community.

Discussions centred on the rational use of drugs and disease prevention.

2. Representation and lobbying

Advocating for the right to the satisfaction of basic needs - particularly of the most

disadvantaged, is the cornerstone of activities of any consumer association. In the are of

health, Ligue des Consommateurs du Burkina (LCB) has been granted the status of board

member within the Centrale d’Achat des Medicaments Essentials Generique (CAMEG) in

Burkina Faso. The institution is in charge of importing and selecting essential drugs of good

quality at a competitive price.

That status allows LCB to lobby board members, who include doctors, to promote the use of

generic drugs whenever possible, as substitutes for more expensive, branded drugs.

LCB regularly conducts visits to pharmacies to ensure that generic drugs are prominently

displayed on counters.

3. Fostering relationships between community and health structures

In an effort to promote better partnership between its members and a local community clinic,

as well as control costs, ASDEC signed a memorandum of understanding with the clinic. This

ensured that ASDEC members would be charged a low price of 1000 Fcfa (US$2) per month

for medication. Most clinics charge between 7000 to 10, 000 Fcfa (USS14-20) per month.

As for tests, ASDEC members would pay only 20 cents per test.

4. Promoting alternative medicines

Environment et Developpement du tiers Monde (ENDA), another CI member has been very

active in promoting the use of medicinal plants. This is in view of the fact that many people

do not have access to healthcare services and conventional drugs and therefore rely on

medicinal plants for treating their ailments. Additional factors which influenced the use of

medicinal plants are culture and lack of financial resources.

ENDA and the Department of Pharmacy at the University of Dakar jointly collaborated on a

project where a plot of land was allocated to grow plants used by traditional healers. The

plants were then analysed by the university scientists.

Plants that have prove to be effective in curing diseases are put in plastic bags labeled and

sold by pharmacies and traditional practitioners.

Leaflets with information about the plants and their curative properties, dosage, indications

and contraindications are distributed in order to allow more people to grow and use them.

5. Changing community behaviors for better health

Most discussions held by consumer organizations on health at the community level focus on

prevention as the way to better health.

One of the main sources of ill health is lack of water and sanitation in disadvantaged

communities, notes ASDEC.

The organization initiated a project in one of the poorer districts in Dakar, where four to five

families composed of five to ten persons each share one tap in rented premises. To manage

the water - the cost of which is expensive - the families had been filling a jar in the morning

and closing the tap for the rest of the day.

Each family member would then dip a pot into he jar for their domestic use (drink, toilet,

cooking, etc...) for the day.

With support from EU, ASDEC ensured that a faucet was attached to the jar, so that the users

do not put their hands into the jar thereby contaminating the water.

A similar operation for better hygiene was carried out by LCB in a campaign “Clean hand

operation'. In most traditional large families and restaurants meals are eaten using fingers.

Everybody washes their hands in the same bowl of water. This generally leaves dirty water

for the last few person to clean their hands. The campaign uses a simple technology: a kettle

and a small receptacle. Water from the kettle is used to wash one’s hand which is collected in

the receptacle. This ensures that the next person washing his/her fingers has access to clean

water from the kettle.

The success of the campaign was such that most restaurants in Burkina Faso adopted the

technology. As for street food in Benin, Association pour la Protection du Consommateur et

de son Environnement an Benin (APCEB) promoted the use of meat-safe with glass or net to

protect food sold to children at schools or at markets.

By:

Mbacke Ndeye Soukeye Gueye, Association Senegalaise pour la Defensa de

rEnvironnement et des COnsommateurs (ASDEC)

Taken from:

Consumers International (1998). What the Poor Themselves can do to Achieve Access to

Healthcare. Poverty: Rallying for Change (p.66-67). Consumers International:

Penang

.4 case study for discussion on community action at Chennai Workdi on. \1ay Vis

The INPACT Project in Thailand

In April 1999, a project outline was drawn up between the Population and Communit}'

Development Association (PDA), Monsanto Company (USA), Monsanto Thailand, the

International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the Department of Agriculture (Thailand).

The project, entitled “Innovative Partnerships for Agricultural Changes in Technology”

(INPACT), aimed to use a micro-credit system to encourage rice framers in the Nang Rong

and Lamplaimart Districts in Buri Ram Province, Northeast Thailand, to use Monsanto’s

pesticides and other technologies.

According to the project, both IRRI and Monsanto would train fanners on how to use their

recommended technologies. The technologies include:

land leveling

Monsanto’s conservation tillage technology

tractor operation

use of herbicides

use of seeds with “improved quality and traits”

harvesting and threshing technology

The participating fanners would then work with PDA to teach other fanners to “increase the

number of farm households impacted”.

The intentions of the project are clear:

1. To develop the large-scale extensive and industrial rice farming in Thailand;

2. To introduce the use of Monsanto’s herbicides in Thai rice fanning and increase the

sales of its pesticides; and

3. To improve Monsanto’s tarnished name through alliances with established

development groups.

It was also likely that the project would be used to introduce Monsanto’s genetically

engineered seeds or its hybrid seeds into Thai rice fanning. Monsanto is currently developing

rice genetically engineered to be resistant to herbicides. It also holds patents on the infamous

Terminator Technology - which makes seeds sterile and prevents farmers from saving seed

from year to year as they have for generations. Such a technology would be especially

damaging to Thai rice farming, given that the high quality of Thai rice is the result of

generations of careful selection and breeding by Thai fanners.

INPACT claims that it’s goal is to “improve the livelihood of the rural community in North

East Thailand”, but the outline suggests the opposite. The project is actually designed to

reorganize Thai rice fanning in such a way that multinational agribusinesses, such as

Monsanto, can make profits. For example, the project would use Monsanto’s “conservation

tillage”, described in Monsanto’s annual report as “the practice of substituting the judicious

use of herbicides for mechanical tillage.” At the same time, the project aims to mechanise

Thai rice fanning with tractor operations and thrashing technology. In other words, INPACT

will create farms suited to Monsanto’s technology and its financial interest.

Here's how one reporter from the Bangkok Post described the initial operation of the project.

“During the last planting season, the atmosphere in Mr. Sawat s village of Ban Fak Khlong

was electric. Oversized tractors ploughed the selected fields, showcases of advanced land

leveling technology. There was talk that next year the vehicles could be operated by laserguided remote control.

And that was only the tip of the hi-tech iceberg. Buckets of herbicide and fertilizers were

given away, and once in a while hordes of local and foreign specialists would drop by. Either

to observe or offer their views on productivity”.

Mechanised farms that are highly dependent on the products of multinational companies will

never improve the livelihood of Thailand’s rural communities.

Taken from PAN-AP, JZOOO.

Background for discussion on space for advocacy for CSOs.

STATE-NGO RELATIONS

The state’s role is central in the rights-based approach to consumer protection. The state has

so

md

|KliCieS

TTie discourse on what the ‘state’ is has not stopped since people began organizing

themselves into commumtes and established rules to govern their behaviour. The numerous

taki^plac^116

hist°ricaI and PoIiticaI Period the discourse on the state is

Some of the notable definitions are:

An aggregation of different families and villages, organized for the purpose of

providing facilities for the promotion of a happy and prosperous life” - Aristotle

A people organized for law within a definite territoiy” - Woodrow Wilson

An association which, acting through law as promulgated by a government endowed

to this end with coercive power, maintains within a community territorially

demarcated the universal external conditions of social order” - R.M. Maciever

These earlier definitions all point to a convergence of the concept that is well-encapsulated by

The State is the institution through which the dynamics ofpolitics are organized and

formalized. 1 he state consists ofcitizens with their rights and duties, institutions and

jurisdictions, principals and power. It is a network ofstructured relationships.

Lipson distinguishes the “State” from the “government”:

, , , fstate has ^government, and the latter signifies those specific persons who

hold official positions and wield authority on behalfofthe state/Government therefore

implies a distinction within the state between the rulers and ruled (Ali Qadir, 2001).

iS USed tllrou8hout this book. Shinichi Shigetomi (ed.) describes in The State

and NGOs: Perspective from Asia (2002) the major attributes of an NGO.

For an NGO to have legitimacy, its decision-making process must be independent of the

Government. An NGO Must be: (1) non-governmental, (2) non-profit making, (3) voluntaiy

(4) not ad hoc, (5) altruistic and (6) philanthropic.

,th

course when it is conceded or the state has abdicated.

wsieu except ot

NGOs are often referred to as the third sector, after the public and private sectors. NGOs in

developing countries perform varying functions such as delivering services, creating

economic activities and carrying out advocacy work. The functions of NGOs are primarily

determined by the needs and situations in the countries they operate.

The functions undertaken by NGOs are determined not only by their philosophy and

ideological orientations and financial resources, but also by the economic and political spaces

available to them.

When the state, market and community fail to deliver the resources and services to meet the

needs of the citizens, NGOs can be seen accessing that economic space. Conversely, if the

state, market and community supply more resources and services to the citizens, the

economic space for NGOs proportionately shrinks.

One of the state’s primary functions is to provide the basic needs of its citizens, including

food, housing, health and education. The market’s role is to supply adequate quantities of

goods and services efficiently and at a low cost. The community on its part caters for social

needs through such activities as religious giving and philanthropic ventures. Citizens also

benefit from sharing community-owned resources such as forests, parks and irrigation

systems.

Bangladesh, where extreme poverty has crippled human development, for example is one of

the countries in Asia which ranks among the top countries in terms of the extent of NGO

activities providing services and economic activities. Some of these NGOs such as BRAC are

very large, employing 15 000 staff, and its services reach 5 million people. The state depends

on NGOs to supply public services due to a severe lack of resources. There are close to 3

million NGOs in India; about 56 000 in Pakistan, 400 000 in Thailand and an equal number

in the Philippines. In Sri Lanka, Sarvodaya connects 7 000 villages. The Orangi Pilot

Research in Pakistan reaches 1.5 million urban slum inhabitants.

Global communications have helped to define similar ideals within NGOs even if their

functions differ. “An indication of the similarities is the existence of a host of keywords, such

as ‘participation’, ‘community development’, ‘empowerment’, sustainable development’ and

‘women’, which seem to be emphasised, albeit to vaiying extents, by NGOs around the

world” (Shigetomi, 2002).

A major factor that must be addressed in any discourse on NGOs is how the political space

determines the operations of NGOs even if their ideals are universal. Indeed some scholars

have stated that the vibrancy of a country’s NGO sector may indicate the social development

and political characteristics of the state.

Being weak in resources, Bangladesh depends on NGOs to supply essential services and to

eradicate poverty. In such a situation, the Government has no reason to prohibit the activities

of NGOs. They have nothing to expect from the state and therefore have no incentive to

launch political activities. The net result of these factors is the existence of vast economic and

political spaces in which NGOs are very active. Because the state is weak, NGOs can receive

funds directly from international donors and implement projects with local authorities.

In the Philippines, the Aquino administration expanded the political space forNGOs, and this

e to a marked increase in political activism. However, unlike in Bangladesh NGOs in the

Philippines believe that the state has an important role to play in the distribution of resources,

he hegemonic political force can appoint its own members to important administrative

positions, so that NGOs compete with other forces to secure political influence. As a result

actIvlsm 1S seen as operative to influence the decision-making process (Shigetomi,

Hie foregoing discussion which has touched on the spaces for the proliferation of NGOs

would be incomplete if State-NGO relations are not raised. How NGOs manifest themselves

bung about pohcy reforms or achieve their goals and ideals is contingent on their

relationships with the state. This is more so in the case of the advocacy activities of NGOs.

Interactions between individuals, groups or societies take place within a set of social rules

A l sociefles have a system of rules governing and regulating their members. The state

establishes a set of rules that it applies uniformly to all its constituent societies across the

boundanes, and which it enforces m the name of safeguarding ‘the public interest’. Some of

these rules regulate private mteractions among its citizens, such as meetings. Others regulate

the distribution of resources. These rules and laws determine the “political space” and

economic space for NGOs respectively.

NGOs can change the political space available to them through advocacy, and some of them

make this function central to their operations. Other NGOs choose to focus on the economic

space and gear their activities towards providing services. For example, in countries where

economic growth has brought wealth to the people, such as Singapore and Taiwan, there has

been little political space for decades. In the case of Taiwan, advocacy NGOs have focused

on the democratization of governance and decision-making processes with some success.

Thepohtical and economic spaces are not the only factors that demarcate the boundaries of

NGO work. How NGOs utilize these spaces depend on a number of factors such as culture

and religion, and the leadership and capacity of the NGOs.

Economic Space for NGOs

State

Areas left uncovered by the

Three sectors form the

economic space for NGOs.

Community

Market

Source: Shinichi Shigetomi (ed.)(2002). The State and NGOs Perspective from Asia

Economic Vacant Space and Political Activities by NGOs

State

Vacant space unfilled by

the sectors

NGQ

Market

Community

Source: Shinichi Shigetomi (ed.)(2002). The State and NGOs Perspective from Asia

Question to participants: What proactive advocacy actions will you take in this situation

(Asian financial crisis 1997 -1998)?

The Crisis and Health: A Common Set of Problems

Medical costs are increasing. Exchange rate depreciations have meant large increases in

medical costs given the high import content of pharmaceuticals, including vaccines and

contraceptives. In Indonesia, imports account for 60% or more of the pharmaceuticals used in

the country, and drug prices have reportedly increased two or three fold. This change in

relative prices is unlikely to be fully reverses, and will require long-term adjustments in drug

consumption patterns.

Private consumption expenditure isfalling, particularly among the rising numbers of

unemployed. Many households are less able to pay for the out-of-pocket cost of medical care,

whether provided by the private sector or the public sector facilities that typically charge

nonzero user fees. This is important because private spending finances 50% of aggregate

health expenditures in East Asia. There is already evidence that private sector users are

switching back to the subsidized public sector, while some potential users - especially among

the poor - may have to switch to lower quality providers, or even forego medical care

entirely.

Public health expenditures are declining. Budgetary pressures can reduce public subsidies

which protect the poor from the increased financial risks of illness. This either increases

financial hardship, or reduces use of medical services. Moreover, increased demand for

public services from former uses of private facilities could divert public subsidies from the

poor. In the long term, cuts in operations and maintenance outlays will also undermine the

productivity of the public infrastructure. Reduced public expenditure also threatens priority

public health programs, such as immunization against childhood diseases and TB control.

Indonesia’s past experience with fiscal adjustment in the mid-1980s demonstrates the

vulnerability of public health programs to public expenditure cuts.

World Bank (1998). The Crisis and Health: A Common Set of Problems. And our rice

pots are empty (p.294). Consumers International: Penang

Source:

Fernandez, Josie (2004). State-NGO Relations. Contested Space’ FOMfik

‘ ngagement with the Government (p.8-13). FOMCA: Selangor

"Learning through Evaluation”

Duriiiii^OS Artriurii

This brief paper w as written as an introduction to the Chennai evaluation workshop

on the GPPls advocacy process.

The paper sets out to argue that all evaluation should be a learning process.

presenting some methodological principles to make it happen.

Evaluation as a learning process is here defined as a methodically organised

collective process of evaluation based on experience, guided by a set of critical questions

and presided over by the sense that learning is a vital conditional for effective social

change.

Such an evaluation process promotes the critical analysis of the experience

individual organisational and collective - confronting it with visions, expectations,

objectives and outcomes, in order to produce a methodologically sound and socially

relevant new knowledge which systematises the main findings and lessons learned.

It is important to point out that development evaluation has not always meant a

process of learning. Unfortunately, evaluation within the development wisdom, in the North

as well as in the South, has all too often been taken in a rather “beaurocratic” and

instrumental fashion, whereby planning, monitoring and evaluation went around a set of

pre-defined results, outcomes and indicators, allowing little space for open and critical

thinking about the factors which could explain success or failure in complex processes of

social change.

Monitoring and evaluation in this sense are closer to “auditing” tools rather than to a

learning experience.

It is strategic to promote evaluation as a learning process because, (i) it contributes

to balance the “results based” kind of evaluation, in which products, results and concrete

outcomes are what really matters and not the rather more intangible experiences and

learning about the process of development itself; (ii) it helps to overcome the traditional

“linear approach” of much of development projects evaluation, whereby social processes of

change are perceived and designed as a simple chain of cause-and-effect, and not as a

complex and simultaneous set of multi determined changes; (iii) it helps to overcome the

activism and the institutional resistance in many organisations of the South with regard to

the development of a culture of evaluation as institutional learning, and finally because (iv)

to promote “evaluation as learning” is the entrance door to any socially strategic action.

Any initiative of “evaluation as learning” should be developed in accordance with

the following principles:

♦ The evaluation should be conceived, organised and conducted as a process of

critical reflection based on key-questions;

♦ The evaluation should use participative working techniques in order to strengthen

ownership;

♦ The evaluation process should allow the emergence of and be able to deal with all

relevant concerns, doubts, criticism, visions, proposals and tensions;

♦

The process should take into account the power relations which structure the group

in question, in order to stimulate and favour equitable participation, considering ah

participants as "‘citizens” of an evaluative “public sphere”;

*

The evaluation process should be able to promote agreements and, whenever

possible, valid consensus;

♦ The process should look at and take into account both tangible and intangible

outcomes;

♦ The process should value both individual, organisational and collective experiences

of learning, and

♦ A more focused process of evaluation leads to deeper learning.

Thus, the evaluation of the GPPI advocacy network should be carried out as a

process of “evaluation as learning” in order to get the most of the experience so far and to

strengthen the planning for the coming period.

For that to happen, some specific guidelines are proposed:

♦ The evaluation has to consider different stages of the experience - defining the

problem and framing the case studies, implementing case studies and carrying out

advocacy initiatives;

♦ The process will systematise evaluation and lessons learned at three dimensions of

the experience: outcomes, capacity building and the process of collaboration.

♦ The learning has to be valued in individual, organisational and coalition terms;

♦ The methodology should strengthen the sense of ownership and commitment of the

participant organisations over the evaluation in order to empower the network itself;

♦ The discussion in the workshop will be guided by a set of key-questions for

reflection, and

♦ The evaluation and lessons learned shall be inputs for the planning of the next

period.

Porto Alegre

May 2005

ADVOCACY INSTITU TE

• '■ Al J.,S - * I f-.A./'-R

•'

'Vs AM:')

TIPS FOR MAKING A COALITION WORK

Coalitions expand the numbers and expertise of those working on an issue; they can unite

unlikely allies and bridge essential gaps. When effective, coalitions mass and focus the

collective skills, resources, and energies of their constituents. When ineffective, they can

drain energy and resources, exacerbate institutional and personal rivalries and conflicts,

paralyze flexibility, and deaden initiative.

There are several basic rules that can make coalitions more effective and help avoid the

greatest dangers. Use these rules to supplement the constant "care and feeding" of

coalition members, which must remain a high priority.

1. State clearly what you have in common, and what you don't.

The goals and objectives of the coalition must be clearly stated, so that organizations

that join will fully comprehend the nature of their commitment. At the same time,

coalition members must openly acknowledge their potentially differing self-interest.

By recognizing these differences, coalition leaders can promote trust and respect

among the members, while stressing common values and vision.

2. Let the membership and the issue suggest the coalition's structure and

style.

Coalitions can be formal or informal, tightly organized or loose and decentralized.

The type of coalition chosen will depend on the kind of issue as well as the styles of

the people and organizations involved. Coalitions evolve naturally, and should not be

forced to fit into any one style.

3. Reach out for a membership that is diverse - but certain.

Coalitions should reach out for broad membership, but not include those who are

uncertain or uncommitted to the coalition's goals or strategies. The most effective

coalitions are composed of a solid core of fully committed organizations, which can

draw together shifting groups of allies for discrete projects or campaigns.

Overreaching for members can result in paralysis and suspicion. There's nothing

worse than a strategy planning session where coalition members are eyeing each

other suspiciously, instead of openly sharing ideas and plans.

4. Choose interim objectives very strategically.

Interim objectives should be significant enough for people to want to be involved,

but manageable enough so that there is a reasonable expectation of results. They

should have the potential to involve a broad coalition and be of sufficient interest to

gain public and media attention. Interim objectives should be chosen so they build

relationships and lead toward work on other, more encompassing objectives.

© 2004 Advocacy Institute, Washington, DC

ADVOCACY INSTITUTE

-■4A.KIMC -<-C .V

■:? IEA?,=F5I- ■-

.^Ffr - -.r AM;?

Jr. ■ AIEAKIr

5. Stay open to partnerships outside the forma! coalition structure.

A coalition must be able to work with a great diversity of advocacy groups, but all

groups need not belong as formal members. Organizations whose goals are more

radical, or whose tactics are more extreme, are often more comfortable and effective

working outside the formal coalition structure and informally coordinating their

activities.

6. Take care of the coalition itself.

At the heart of every successful coalition, there should be a small directorship of

leaders who are deeply committed not only to the issue, but also to the coalition

itself, and to the importance of subordinating the narrow interest of their individual

organizations to the overall goals of the cause.

7. Maintain strong ties from the top to major organizations.

The coalition's leaders must also have strong ties to the major organizations and

their leaders must be strong. This commitment must be communicated within the

organization, so that its staff members clearly understand that coalition work is a

high priority.

8. Make fair, clear agreements and stick to them.

Coalition tasks and responsibilities should be clearly defined and assignments

equitably apportioned. If a member is falling down on the job, that should be dealt

with promptly. Meetings should allow opportunities for members to report on their

progress.

© 2004 Advocacy Institute, Washington, DC

EVALUATION: THE NECESSARY SYNTHESIS

An instrument of the present to build the future

Background document for the first meeting of

the WCC (Latin America) Evaluation Commission

Ana Maria Bianchi dos Reis

Salvador - Bahia - Brazil

1993

Introduction

In recent years evaluation has been an important item on the agendas of funding

agencies and NGOs that support people’s movements. Similarly, it is an issue

increasingly raised among agencies of civil society and the State, whether they are

involved in production or provide services.

What is the significance of this fact?

What issues are being discussed when an evaluation is a

self-defined need and when it is requested by external

partners?

What about the evaluation is specific to people's

movements, NGOs, ecumenical service organizations

and agencies?

What is the role of the different actors in the process?

What are the basic methodological issues: theoretical,

philosophical and ideological presuppositions; criteria,

phases, procedures, instruments?

What are the repercussions of evaluation processes on

the life of organizations and progi'ammes that are

evaluated?

These are some of the aspects of the question that can be studied; this paper proposes

to begin the study, as a contribution to the work of the WCC in Latin America, in

dialogue with funding agencies.

The sharing of experience of each of the participants of the Evaluation Commission

will allow us to arrive at conclusions and proposals that broaden the present approach

and can be useful in each particular situation and in reaching our common goals.

I. Context v. concept

In terms of political economy, the world’s frontiers are becoming less rigid because of

the need for mutual support.

Given this fact, a planetary situation is clearly emerging that transcends national

interests and moves towards solutions that can only be reached in the ’’unity of

diversity”.

At the same time, we are at a frontier, a hiatus in world history' when the paradigms on

which the organization and administration of society7 were founded are being

questioned as a result of historical experience.

Evaluation: The Necessary Synthesis - 2

This growing awareness of the economic, political and ecological interdependence for

equilibrium on a world level and the common challenge to find solutions redraw the

significance of social movements, people's organizations, advisory bodies and

international cooperation.

With different emphases depending on particular contexts, the dichotomy between the

discourse and the practice of organizations and programmes is becoming evident.

Along the same lines, it becomes increasingly urgent to make the transition from a

practice centered on the denunciation of social conflicts to investment in the

formulation of proposals that solve existing problems. The basic focus gradually

stops being the destruction of the old to be construction of the new.

Evaluation emerges in this context as an instrument to verify the effectiveness of action

- to ensure its significance, to check its contemporary relevance. To this end, it has

been necessary to reformulate the original concept and practice which were based on

the idea of control, comparing what was planned with what was achieved; traditionally,

such evaluation took place at the end of a project.

The hallmark of the new concept is the awareness that there must be ongoing

adjustment, that constantly joins knowledge and practice so that goals can really

be reached.

This is a concern common to those in both public and private sectors who want their

projects to be implemented.

Thus, the main subject of evaluation is no longer the past, a specific action or a

multisectoral project that has already taken place and that can/should only be evaluated

after it has ended, generally within the limits of input v. product analyses.

Even when it is held at the end of a working cycle - and depending on the methodology'

used - evaluation can still be a process if the content is identified as of current interest:

objectives, goals, technical procedures, management conditions and the part played by

each specific action in the broader (economic, political and cultural) context that gives

it meaning.

In this sense, evaluation can be spoken of as the necessary synthesis, able to point

to issues of different kinds that shape the achievement of objectives during the

programmes’ existence.

IL The Approach

Most evaluations originate in questions about the effects and impact of programmed

action:

• The effect - the most immediate, direct result of an action.

Evaluation: The Necessary Synthesis - 3

• The impact - the broader result that changes significant relationships, acting as a

multiplier and generating other processes.

Analyses of efficiency and efficacy are made under these two headings.

. Efficiency takes in the ability to design, choose and use the methodologies,

techniques and procedures that are most suitable to carrying out the actions and,

therefore, to achieving the goals.

. Efficacy conesponds to the effectiveness and the quality of the result obtained.

When an organization decides to evaluate its work or one of its programmes, or when

a funding agency requests evaluation of one of the programmes it finances, these

elements and many others are in play. Among them, perhaps the most important is the

ability to perceive the specificity and to have an overview of the work, in other words,

its conjunctural characteristics, its potential and its structural limitations.

The analysis of the process and the analysis of the results are both influenced by

the parameters thatform the basis of evaluation.

For example, a project may not have reached its operational goals, compromising a

study of results (effects, impact, in the traditional aproach). During the project's

development, however, fundamental progress may have been made as compared to

the previous experience of the group - increased awareness of citizenship, technical