15134.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

TOWARDS UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE:

An operational manual for states in India

Intermediate

situation - SOME

services for ALL the

people

Universal Health

Coverage ALL services to

ALL the people

• Current situation ALL services only for SOME

people

TOWARDS UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE

An operational manual for states in India

CONTRIBUTORS

Cite as:

IPH UHC team. Towards universal health coverage: An operational manual for

states in India. Institute of Public Health, Bangalore. 2012.

Towards Universal Health Coverage: An Operational

Manual for States in India by Institute of Public Health,

Bangalore is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCcmmercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

License.

1

PREFACE

There has been much talk about Universal Health Coverage (UHC), both internationally as well as

nationally. Presently, there is a major emphasis on moving towards universal coverage, a goal that is laudable

and must be encouraged at all cost. So it is heartening that the Planning Commission has taken the lead in

commissioning a high level expert group (HLEG) to initiate the debate and discussions on UHC in India.

In India the debates and discussions about Universal Health Coverage have tended to remain at a

policy and macro level coupled with inadequate information and much less clarity on the steps required to

operationalise the concept of UHC. It becomes more crucial in the context of health being a state subject in

India, with the State governments having the responsibilities to implement polices to achieve UHC. Further

there is confusion with regard to UHC and its linkages with current health systems and programmes like the

NRHM.

In this context some of us felt the need to go beyond broad policy recommendations and come up with

steps to operationalise UHC. The Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru undertook this task. The key guiding

principles in preparation ofthe document were that

•

Health care services should be accessible and affordable to all sections of Indian society, especially the

vulnerable section ofthe population.

t

•

Health care services should be equitably distributed between urban and rural India, between men and

women, between rich and poor, between the castes and among the States.

•

Health care services should be aimed at maximizing health gain.

This document attempts to provide an understanding of the concept of UHC, explain in detail the

critical aspects with reference to population and services to be covered, financing and the method of delivery.

It is specifically targeted for the State level policy makers and implementers, so that they are able to diagnose

where their state is vis-a-vis UHC, identify the necessary steps they need to take to prepare a roadmap

towards achieving UHC.

This document is not a blueprint, but provides some options for policy makers and those in the

decision making process to consider. The document draws from the various discussions held by various

stakeholders in the past and several documents and experiences of several countries in achieving UHC. The

document brings together a few practical tools (including an excel sheet) necessary to understand how UHC

may be planned at the state level. That said, there is no ONE way or the ONLY way in planning for UHC. Any

manual on UHC is never likely to be the one-stop-shop for EVERYTHING on UHC. The document is a "work in

progress" that may benefit greatly from experiences of policymakers and other stakeholders. We welcome

3

any discussion around shortcomings and critiques of the document, as long as alternatives are provided.

These could be included in subsequent editions of the document to improve its relevance and applicability.

This document does not take any positions regarding, "Public Vs Private"; "Biomedical Vs Social

determinants”; "Health Vs Health Services”; "Purchasing Vs Providing"; "BPL list Vs Actual Poor"; etc.

Similarly, we are silent on AYUSH services, not because we are pro-Allopathic, but because we are not clear on

how to include them in our design of UHC. We would really appreciate experts in this field to give us

suggestions to incorporate AYUSH services as well. This document was drafted with the premise that there

are existing health services and programmes with its own infrastructure, organisation, governance

mechanisms and information systems. Rather than ignore this and start on a clean slate, we decided to build

on these see how best to dovetail our suggestions into the existing system.

The document has been written with the assumptions that the State governments are keen on

moving towards UHC and are willing to allocate necessary resources (financial and others] to achieve

UHC. Each chapter of the document is linked to the preceding and subsequent ones, and so we would

request the reader to go through the entire document. To reiterate, this manual is a humble attempt by the

Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru, India to assist the governments increase the access to quality health

care for all residents (and especially the vulnerable] while protecting them from high medical costs and

subsequent indebtedness and impoverishment.

The authors

September 2012

4

Table of Contents

PREFACE..........................................................................................................................................3

BACKGROUND................................................................................................................................ 6

WHAT IS UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE?............................................................................ 8

WHAT IS POPULATION COVERAGE?...................................................................................... 13

WHAT ARE THE SERVICES TO BE COVERED?...................................................................... 16

HOW WILL THE SERVICES BE FINANCED?.......................................................................... 20

WHERE IS MY STATE ON THE PATH TO UHC?..................................................................... 23

HOW ARE THE SERVICES TO BE DELIVERED?.................................................................... 25

WHAT ELSE IS REQUIRED TO ACHIEVE UHC?..................................................................... 30

Governance........................................................................................................................ 30

Monitoring....................................................................................................................... 30

Support Services.............................................................................................................. 30

Quality and equity............................................................................................................ 30

CONCLUSIONS..............................................................................................................................31

References.................................................................................................................................... 32

Annex 1 - Health indicators in India, vis-a-vis the MDG goals........................................... 33

Annex 2 - Estimating the cost of UHC..................................................................................... 35

Annex 3 - Tool monitor the status of UHC............................................................................. 37

Annex 4 - Provider payment mechanisms to procure private provider services

38

5

BACKGROUND

It is now 65 years since India became independent and the health sector has achieved much from the pre

independence era. Currently, we have a three-tier government health service providing the spectrum of

promotive, preventive and curative health services. National health programmes focus on priority diseases

like tuberculosis and malaria. There is also a strong private health sector providing mainly curative services

at all levels. Some key milestones in the Indian context are:

1947

Acceptance of the Bhore Committee Report

1978

Acceptance of the Alma Ata declaration of 'Health for all'

1983

The first National Health Policy

2002

The new National Health Policy and the National Population Policy

2005

Launch of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM)

2008

Launch of the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY)

2011

Presentation of the HLEG report to the Planning Commission on Universal Health

Coverage (UHC)

Health services are provided by a mixture of government and private providers, practitioners of Allopathy,

AYUSH and herbal medicine, qualified and less than qualified health workers. Given this plurality, there is

very little coordination or synergy between them. According to a recent government report , there are

only 231 human resources for health (HRH) per 100,000 population; the desirable ratio needs to be 450.

So it is clear that we need to produce many more health workers and ensure that they are retained at the

desirable places.

Health financing by the government has been abysmally low. Most of health care in India is financed by

individual households at the point of care. This in turn leads to barriers to access, catastrophic health

expenditure and impoverishment due to medical expenses. Government has tried to infuse resources

through various mechanisms, ranging from the NRHM to the RSBY, but even then, the latest figures suggest

that the allocation on health has increased from 0.9% to 1.06% of the GDP.

Medicines and consumables are in short supply and there is evidence that most government health

facilities suffer from frequent stockouts. This leads patients to purchase medicines from private pharmacies,

increasing their out-of-pocket expenses. Articles have suggested that expenses on medicines have been an

important reason for impoverishment.

The NRHM tried to provide a voice for the community by creating institutions like the village health and

sanitation committees (VHSC), the Accredited Social Health Worker (ASHA), the patient welfare committees

at each facility (RKS) and independent health societies with civil society and panchayat representatives in

them. However, at the end of the first phase of the NRHM, there is unanimity that these bodies have not

fulfilled their roles.

Governance was decentralised and bottom up planning was encouraged through the NRHM. Facilities were

given the financial powers to receive and use untied funds. Quality was strengthened by developing Indian

public health standards (IPHS) and infrastructure was revamped using the additional funds.

However, in-spite of all this, the health status of Indians did not improve drastically (Annex 1). Infants and

mothers continued to die, we were home to the largest number of malnourished children, infectious diseases

6

still remained out of control and the health services had begun feeling the burden of non-communicable

diseases.

It is a matter of shame for India that many of our neighbouring countries, with much less resources, have

caught up with our health indicators. Admittedly, India is a large country compared to our neighbours, but

we forget that most of the Indian states are similar in size to these countries

It is in this context that the country decided to move towards UHC. Many middle-income countries like

Thailand, South Korea, Philippines, Brazil and South Africa are well on the way to achieve UHC. In the next

section, we describe what UHC is and give examples of how some countries have achieved it in the recent

past.

Iatrogenic poverty: the effect of no UHC.

S~ was the wife of a middle class businessman in Anand. She owned a

three storeyed house with the vegetable business in the ground floor. Her

two sons assisted her husband, while her two daughters-in-law helped her

in the upkeep of the house.

Her world was turned upside down when her husband met with a traffic

accident. He was admitted to a nearby hospital and lived for 40+ days

before giving up the struggle. S~'s struggle started only after this. She and

her sons had to sell their house to pay the hospital bills. They also had to

mortgage all the jewellery in the house to buy medicines.

When I met S~, they were living in a kuchha house and her two sons had

gone to vend vegetables in a push cart. Her grandson was removed from

school because they could not afford the fees and books.

7

WHAT IS UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE?

UHC is actually part of the WHO mandate to promote health for all (HFA). Unfortunately, the HFA

movement did not materialize due to various reasons. In 2005, the World Health Assembly passed a

resolution urging all countries to achieve UHC for their citizens as soon as possible. The Commission

on Social Determinants of Health (SDH) and two World Health Reports (2008 and 2010) further

reiterated the conceptof UHC.

Many of the high-income countries have achieved UHC, but over time and with a lot of resources.

Germany took nearly 118 years to achieve UHC, while Belgium took 64 years to ensure that 99% of

its citizens were protected against both major and minor health risks. Others like Thailand and

Korea used a big-bang approach to cover most of its population within a short period of time. There

are many examples of countries that have achieved UHC at the global level. An analysis of these

country case studies tells us that UHC is not a prerogative of only rich countries. Several middle

income countries such as Mexico and Thailand have been able to achieve UHC. On the other hand,

there are several high-income countries that have not been able to achieve UHC in spite of spending

a lot of money on health care. The classic example of this latter is the United States of America.

Hence, achieving UHC is not merely about resources, but also about "how” these resources are used

and the arrangements through which these resources are used to provide healthcare. And, more

important, it is about the political will.

UHC has been defined by the WHO as "access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative

health interventions for all at an affordable cost". On the other hand, the Commission on SDH

states "Universal coverage requires that everyone within a country can access the same range of(good

quality) services according to needs and preferences, regardless of income level, social status, or

residency, and that people are empowered to use these services". In this manual we use the definition

as stated by the Steering Committee of the Planning Commission (7).

"Ensuring equitable accessfor all Indian citizens, resident

in any part of the country, regardless of income level, social

status, gender, caste or religion, to affordable, accountable,

appropriate health services of assured quality

(promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative) as well

as public health services addressing the wider

determinants of health delivered to individuals and

populations, with the government being the guarantor

and enabler, although not necessarily the only provider, of

health and related services.

Steering Committee, 12^ Five Year Plan, Planning Commission 2012.

8

What does this mean in reality? It basically means that should anybody in India fall sick, he/she

should be able to seek health care at enlisted health facilities at a cost that is affordable to the

patient. To expand this further, be it a manual labourer or a software engineer, if both suffers from

diabetes; they should be able to get their treatment at nearby facilities without having to pay for it at

the time of illness. So the key words in UHC are

• All citizens should be able to access

• Most of the health services at reasonable quality with

• Minimal direct payments because

•

Government guarantees these services

In moving towards universal health coverage three dimensions have to be considered namely;

a population dimension - who is to be covered, populations to be reached, with priority to be given

to the poor and vulnerable; a health service dimension - which services are covered and how

services are to be delivered; and a financing dimension - how to reduce OOP expenditures by

converting direct payments into pre-payments. The famous WHO cube elucidates this very well.

Figure 1: Universal health coverage - the three dimensions

Which population is covered?

Adapted from the World Health Report 2008.

In a country where there is UHC, this figure resembles a different picture, with most of the cube

beingfilled (Figure 2).

There is increasing interest in UHC because governments have realized that one of the drivers for

economic growth is a healthy population. The Commission on Macroeconomics and health [CMH]

has clearly identified the financial losses to a country because of illness and has requested countries

to invest more resources into the health sector. In India, the UHC dialogue was initiated only in 2011.

The Planning Commission constituted a HLEG to submita report on how India can achieve UHC, as a

prelude to the 12th Five Year Plan. The HLEG submitted its report in Oct 2011 which was met with

mixed feelings. While many have applauded it for bringing health to the centre of the development

debate, others have criticized it for being a wish list. Based on the HLEG, the Planning commission

clearly identifies UHC as the way forward for India (1).

Figure 2 : The WHO cube in a country with UHC

Which population is covered?

Narin's experience after head injury

The accident happened on 7 October 2006. Narin came off his motorcycle going into a bend. He struck

a tree, his unprotected head taking the full force of the impact. Passing motorists found him some time

later and took him to a nearby hospital. Doctors diagnosed severe head injury and referred him to the

trauma centre, 65 km away, where the diagnosis was confirmed. A scan showed subdural haematoma

with subfalcine and uncal herniation.

He needed an immediate neurosurgical intervention. He was wheeled into an emergency department

where a surgeon removed part of his skull to relieve pressure. A blood clot was also removed. Five

hours later, Narin was put on a respirator and taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he stayed

for 21 days. Thirty- nine days after being admitted to hospital, he had recovered sufficiently to be

discharged.

What is remarkable about this story is that the episode took place not in a high income country where

annual per capita expenditure on health averages close to US$ 4000, but in Thailand, a country that

spends US$ 136 per capita, just 3.7% of its gross domestic product (GDP). Nor did the patient belong

to the ruling elite, the type of person who - as this report shall show - tends to get good treatment

wherever they live. Narin was a casual labourer, earning only US$ 5 a day!

- 2010 World Health Report

10

While most state governments will aver that they provide 'free health services' to the poor

population, the reality is otherwise. Many health services are not available at the government

facility and even if they are available, patients may have to pay for it. Some examples are used to

illustrate this:

•

Immunisation services are available free to all children in India. This is easily available and

accessible in rural areas. However, the lack of facilities in urban areas forces parents to go to

the private sector and pay for the immunisation of their children. So while immunisation

services are available free to most rural children, it is not so for the urban children.

•

Outpatient services are supposed to be free in all the PHCs in the country. However, most

PHCs do not have enough medicines, so patients are forced to purchase medicines from the

private pharmacies . Thus once again, an assured service is not provided to the citizen,

resultingin deficiency of UHC.

•

TB treatment is provided free to all patients suffering from the disease. The network of TB

clinics and microscopy centres ensures that these patients have the potential to get free

treatment. However, this service is only limited to the TB patients and not to patients with

appendicitis or diabetes or pneumonia.

•

Employees of the Indian Railway services get comprehensive care for all conditions, be it

preventive, promotive, ambulatory or inpatient care. Even catastrophic events are covered

by the employer. However, this luxury is limited only to the employees of the railways and

their family members. It does not apply to people outside this exclusive circle.

So in reality, governments currently provide

1. Some services free of charge to all of the population (e.g. immunisation for children,

treatment for leprosy, TB, malaria, etc).

2. Some services free of charge to some of the population (e.g. inpatient services for BPL

population groups).

3. All services free of charge to some of the population(e.g. employees of the Indian

railways or the beneficiaries of the Central government health services).

4. All services free of charge to all the population (currently not provided by any state).

No state has achieved universal health coverage. The important point is to identify where the state is

and progress from #1 or #2 or #3 toward #4. More important, it is not enough for a government to

say -we are providing XXX services. The government HAS TO guarantee that the population

actually benefits from these services. This can be achieved either by the government providing the

services itself or by purchasing services from the private health sector. A tentative stepwise

approach is provided in figure 3.

Other than this, the government should also consider how this entire process should be

governed / managed / administered and from where it will mobilize extra resources to finance

UHC. In the next sections we take the reader through some of the key steps to achieve UHC.

11

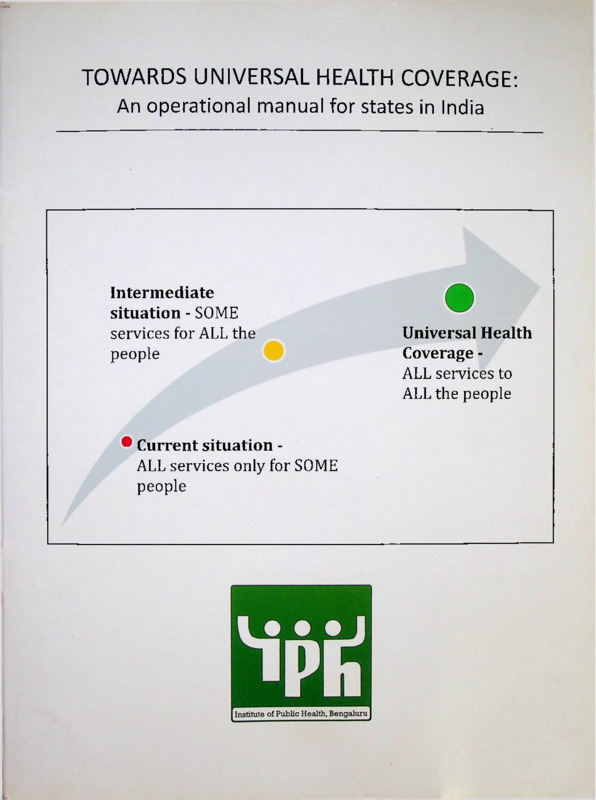

Figure 3 : Potential path to Universal Health Coverage in India.

Intermediate situation where SOME services are

provided free of charge to ALL

the population

Universal Health

Coverage where MOST of the

services are provided

free of charge to ALL the

population

Current situation most services are paid for by

individual households through direct

out-of-pocket payments

Adapted from: Carrins G; James C; Evans D. Achieving Universal Health Coverage: Developing the health financing system.

WHO: Geneva; 2005.

Some people in our country enjoy total and comprehensive health

care without paying money at the point of care. Examples are

employees of the Indian Railways, the troops of the defence forces, the

members of the CGHS scheme, etc.

India will achieve UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE the day each

Indian benefits from similar complete and comprehensive care that is

free at the time of use.

12

WHAT IS POPULATION COVERAGE ?

The first dimension of UHC is population - who should be covered under the universal health

coverage system? Ideally (see definition), all residents in the state should be covered under the UHC

system. This means that irrespective of the social, economic, cultural and political background of the

household, they are eligible to receive free health care. Currently, the existing government health

services do try to provide care to all the population. However, the reality is different. For example, a

tribal patient with an acute appendicitis may have to travel all the way to the district hospital to get

the necessary treatment. On the other hand, a white collared employee in a private firm can get the

treatment in a nearby hospital. Under UHC, ideally both these sets of people should get health care

as near as possible to their house, so that patients face the minimal barriers to care. In a health

system that has achieved universal coverage, the services must be provided to one and all,

irrespective of where they stay (in the state) or who they are.

Studies and surveys clearly show that currently, there are vast numbers of people who cannot access

health care because of barriers like money, distance, availability, acceptability, etc. Who are these

population groups who are excluded? In India, these could be the indigent, the SC / ST households,

those living in border districts, families belonging to certain religious minorities and of course those

who reside in rural areas. Politically and epidemiologically, the highest priority is to identify and

cover the most vulnerable people who are at risk of suffering due to lack of coverage. Therefore, any

UHC plan at the state must ideally seek to identify and cover the most vulnerable at the first instance.

Once this population is covered, then the government should move onto the next population group.

In the long-term, the goal is to cover everybody in the state under the defined services.

How does one identify the various groups? One simple way is to look at them from economic

parameters, e.g. BPL and APL. All those with BPL cards will be provided the services initially and

then those with the APL cards. This is a simple except that when one comes to APL, then the numbers

are large and a state government may not be able to provide to this entire group in one step. So we

may need to break down the APL group further. A simple way for this is to use occupational groups;

e.g. formal sector and informal sector. While the former is easy to cover, as their details are available

with the employers, the latter is once again a nebulous group. To cover the informal sector in

instalments, one can use existing natural groups like "unions," "cooperative societies,""societies,"

"associations," "welfare boards," etc. These usually have most of the individuals of that occupational

group as members. It may be argued that this will not cover the landless agricultural farmers; but

ideally this group should be covered under the BPL category. And, remember that this is a process,

once people realise that there is an economic benefit in joining a group, the chances of more such

individuals joining these groups become a reality.

13

The figure below depicts the mosaic that forms India. There are many groups and sub groups and

we can create similar mosaics along religious lines or caste lines or linguistic lines or

geographic lines. For the sake of this document, we have used a combination of economic and

occupational subgroups as they are easier to identify. Most important is that whatever the

mechanism of grouping, it should be easy to identify the subgroups using existing documents and

processes. For example, SC / ST populations usually have caste certificates, the poor have BPL cards,

domestic workers have union cards, farmers have cooperative society membership cards, drivers

have union cards, shop owners have their own association membership cards, Self Help Groups

have a list of members, construction workers and beedi workers are enrolled in their respective

boards, etc. In this manner, each sub group can be identified by existing documents and

systematically brought under the umbrella of UHC.

Figure 4 : The various groups within India's population

Members of

occupational unions

e.g. domestic workers

union, beedi workers

Employees in

Entrepreneurs shops and

establishments

Government

sector

employees

Thailand is a good example of a country that went about covering its population systematically.

In 1991, about 32% of the population had access to free health care (both ambulatory as well as

inpatient, preventive as well as curative). Most ofthese were either the government employees (10%)

through a civil servants medical benefitscheme or the poor (17%) through a welfare scheme. Over the

next ten years, they brought the private sector employees under health cover through a compulsory

health insurance and the informal sector through the Universal coverage plan.

While, theoretically all Indians can access 'free' health care, the reality is otherwise. Only 5% of

patients seeking ambulatory care do not have to make OOP payments. The situation is worse when it

comes to inpatient care. If we dis-aggregate populations in India along occupational lines (Table 1),

we note that 77 million I ndians have access to complete health care without having to pay at the time

of treatment. Another 195 million are protected against hospitalisation expenses for secondary

care, either under RSBY or by private health insurance. A hundred and forty five million Indians are

protected against hospitalisations for tertiary care because of the catastrophic social assistance

schemes in three southern states.

14

Figure 5 : Progress towards universal health coverage: example from Thailand

So the challenge is to identify sub-groups within the uncovered and partially covered population,

prioritise based on vulnerability, ease of coverage and financial resources and cover these

populations incrementally or totally.

Table 1 : Categories of Indians and the health services that they receive. (Population in millions)

Category of population

Benefits received

Number of

individuals

Central government

employees, MPs judges, etc

3

Free and compl ete care under CGHS

Formal sector but earning

<Rs 15,000 pm

56

Free and complete cover under ESIS

Defence troops

11

Free and complete care under AFMS

Indian Railway staff

7

Free and complete care under Railway health services

Formal sector and earning

>Rs 15,000 pm

55

Free hospitalisation services for secondary care under

private health Ins.

Informal sector - BPL

140

Free hospitalisation services for secondary care - RSBY

Informal sector - BPL (in

Andhra Pradesh]

70

Free hospitalisation services for tertiary care under

Aarogyasri.

Informal sector- BPL (in

Tamil Nadu)

40

Free hospitalisation services for tertiary care under CM's

Health Insurance.

Informal sector - BPL (in

Karnataka)

35

Free hospitalisation services for tertiary care under

Vajpayee Arogyashree Suraksha

Informal sector - Farmers

(in Karnataka)

3

Free hospitalisation services for surgical care under

Yeshasvirri

Formal and Informal sector

- who are partially covered

1,123

They receive free hospitalisation services or free

preventive services or free ambulatory care ....

NB: These are estimates based on data from multiple sources including the planning commission chapter on health.

It is not to be taken as the final figure.

Each state needs to first identify those populations that are not covered

by outpatient I inpatient services. If the numbers of this population are

high, then the state can further prioritise depending on the vulnerability

and target them first and later expand to other population sections.

15

WHAT ARE THE SERVICES TO BE COVERED ?

The World Health Organisation defines health services as all the services that deal with the

diagnosis and treatment of disease, or the promotion, maintenance and restoration of health. Health

services are the most visible part of any health system, both to users and the general public. Delivery

of health services is an important function and a building block of the health system.

Ideally, all the health services should be available to all the population at a negligible cost.

However, that is often not a reality, given various constraints within and outside the health systems.

As discussed in the earlier section (Population), there are inequities in access to health services

across the population groups. This could be due to various reasons, including non-availability of the

required services. For example, pregnant women need access to Comprehensive Emergency

Obstetric Care (CEmOC), but if blood is not available at the CHC, then CEmOC services will not be

easily accessible for a poor rural pregnant woman. Similarly, if common antibiotics are not available

at the PHCs, then children cannot access to treatment for pneumonia or other infectious diseases.

Another example is of a government medical college that provides cardiac surgery, but this service is

available only in the state capital. And, most who need valve replacement for rheumatic heart

disease may not be able to reach this college. So though the services are provided 'free' to all the

state's citizens, in reality it is accessible to only those who have the resources. All these examples

clearly show how in our country, access to health services is not universal in the government sector.

This means that the patients turn to the private sector for their needs, but end up paying high OOP

payments to get the benefits. Thus the extent of service coverage in our country is partial.

So one important step, in the path to UHC, is to list all the possible health services that a population

needs. This then can be prioritised according to the local demand, the technical needs, the

community's demands and the availability of resources. Some examples of a list of health services

are provided in table 2 for the readers' benefit. However, this is not exhaustive and is only indicative.

What is important is to first make a list of all the services and then highlight the priority services that

the government wants to provide at all its citizens.

Table 2 : Tentative list of health services that may be required by a population in India

Preventive Services

Provided

(Yes / No)

Curative Services

provided TAI'!

Provided

(Yes / No)

Promotive

Services

Antenatal care

Outpatient care

Safe drinking water

Immunisation

Emergency services

Nutrition services

Growth monitoring

Inpatient services

1EC services

Screening for cancer

Delivery services

Tobacco control

Screening for DM

CEmOC services

Yoga

Screeni ng for HT

ICU services

Counselling

Ambulance services

Surgical services

Anti vector measures

Yes/

No

16

Yet another way of making a list is to follow the existing national health programmes; e.g.

reproductive health

services, child health

services, malaria

control services, TB

control services,

blindness control

services, NCD control

In recent years, many low- and middle-income countries have gone

through exercises to define the package of benefits they feel should be

available to all their citizens. This has been one of the key strategies in

improving the effectiveness of health systems and the equitable

services, etc. The

distribution of resources. It is supposed to make priority setting, rationing

advantage is that

of care, and trade-offs between breadth and depth of coverage explicit. On

these services are

the whole, attempts ervfce delivery by defining packages have not been

already being

particularly successful. In most cases, their scope has been limited to

provided by most

maternal and child health care, and to health problems considered as

government health

global health priorities. The lack of attention, for example, to chronic and

non-communicable diseases confirms the under-valuation of the

services to a certain

demographic and epidemiological transitions and the lack of

extent. The

consideration for perceived needs and demand. The packages rarely give

government would

guidance on the division of tasks and responsibilities, or on the defining

then need to invest in

features of primary care, such as comprehensiveness, continuity or

them systematically so

person-centredness. A more sophisticated approach is required to make

that these services are

provided to all the

population in the

the definition of benefit packages more relevant. The way Chile has

provided a detailed specification of the health rights of its citizens

suggests a number of principles of good practice.

•

region or state. For

example, a

should look at demand as well as at the full range of health needs.

•

It should specify what should be provided at primary and secondary

•

The implementation of the package should be costed so that political

levels.

government may state

that it will ensure that

decision-makers are aware of what will not be included if health care

ALL children of the

state will have access

remains under-funded.

•

to free immunisation

services (including

children in the urban

The exercise should not be limited to a set of predefined priorities: it

There have to be institutionalized mechanisms for evidence-based

review of the package of benefits.

•

People need to be informed about the benefits they can claim, with

mechanisms of mediation when claims are being denied.

World Health Report 2008. Primary Health Care - Now more than ever

areas). Then, it puts

the various

mechanisms in place

to ensure this. Once

this service is assured,

the government can proceed to the next programme. The drawback of this approach is that

ambulatory care and inpatient care are usually not part of most of the national health

programmes. And, these are the basic demands of the community. Without them, the credibility

17

of the government health service suffers, affecting the performance of all other health

programmes. So if a woman is not assured of 24/7 delivery services, the chances are that she will

go to a private practitioner for antenatal checkup and subsequent delivery. Similarly, if 24/7

ambulatory services are not available, a labourer with cough will return from his work and go to

a private practitioner. The latter will then prescribe a serious of cough syrups and unnecessary

antibiotics and never screen for TB. The patient will ultimately end up in the DOTS programme,

but only after spending considerable amounts of money and spreading the disease to all near and

dear ones.

Yet another list that has been developed is as per the NCMH report (Table 3). The advantage of

this list is that it is costed, so when one wants to estimate the cost of choosing a service, one can

just follow the NCMH formula.

Table 3 : Examples of services that need to be provided, as per the NCMH report

Treatment of ARTI

Childhood conditions

Treatment of Diarrhoea

Immunisation

Antenatal checkups

Maternal health conditions

Insertion of 1UCD

Normal delivery

Treatment of TB

Other disease conditions

Treatment of uncomplicated malaria

Treatment of snake bite

Other examples of benefit packages can be from existing good practices, e.g. the CGHS

scheme, the ESIS, the Indian Railways' health services, the Armed Forces Medical Services, etc.

We (the authors] would prefer the checklist as shown in Table 2 as it has certain advantages.

For example, if one says that a government will assure free outpatient and emergency care to all the

patients and this service is available 24/7; then many disease conditions will be taken care of. Such

an assurance will ensure that pregnant women get antenatal checkups, patients with cough will be

screened for TB, patients with fever will be screened for malaria, typhoid and even dengue; children

with diarrhoea get their ORS, diabetic and hypertensive patients get their medicines and patients

with cataract are detected and sent for surgery. So there is a convergence of all the national health

programmes at the level of the PHC. However, for this to happen, the PHC must be strengthened by

ensuring physicians, nurses, medicines and diagnostics round the clock. This may not be possible

with our current staffing and vacancy patterns.

18

Once the services have been prioritised and a consensus arrived on the universality

of the services, then the next step is to decide how these services can be guaranteed

to the population. What is required to ensure that these services are provided to all the population

with minimal Financial barrier? More human resources? More medicines? More health

facilities? Specific equipment? This is dealt in more detail in the chapter on delivery of health

services.

So to conclude this section, the state needs to define the services that they will

guarantee to the population, and then ensure that this is provided to the population. In the

case of curative services, this would require provision of the services round the clock.

It is important to define a comprehensive benefit package, which is

the ultimate goal. And then move towards it systematically.

19

HOW WILL THE SERVICES BE FINANCED ?

Health financing systems have three basic functions: collecting funds, pooling them and then

purchasing care. Funds can be collected either through direct fees or through prepayments. Direct

fees are those charges paid by the individual patient at the point of care, and when the patient is sick.

This is currently not recommended by most health financing

experts. This direct payment has the propensity to act as a

barrier to accessing health care. It can also lead to

catastrophic health expenditure, indebtedness and

impoverishment. Nearly all experts recommend prepayments

to finance health care. This could be in the form of taxes, or

health insurance premiums or deposits into a medical savings

account.

Pre-payment is any expenditure

made for a future benefit (like

health care). People pay a small

amount when they are not sick, so

that when they are sick, they will be

compensated their medical

expenses from this fund.

The advantage of both taxes and health insurance is that there is pooling of funds. This means that

both the rich and the poor contribute towards a health care fund. To give some examples, the rich

pay direct taxes through income tax, wealth tax, capital gain tax, etc. On the other hand, the poor

usually do not pay direct taxes, but contribute through indirect taxes like sales tax, excise tax, octroi,

etc. Thus both contribute to a common pool, which can then be used for providing health services to

both groups of patients when they fall sick.

One of the cornerstones of UHC is to convert direct payments into prepayments. This reduces the

OOP payments and increases financial coverage. Currently, direct payments form the mainstay of

health expenditure in India. In 2008, individual households shouldered 72% of total health

expenditure [THE] through direct payments at the time of illness (Figure 6). Government finances

contributed only 20% of THE, the per capita expenditure on health by the government was one of

the lowest in the world (only INR 540). Health insurance was a negligible amount. In other

countries, the ratios are usually reversed. The majority of health expenditure is met through

prepayments like taxes and / or insurance and the individual households meet only a small

proportion of THE through direct payments. In India we have a long and uphill task to shift from

direct payments to prepayments.

So how much money do we need to achieve UHC? There are many guesstimates. A recent article in a

journal mentions that we need to spend INR 1,713 per person per year to achieve UHC .The NCMH

report way back in 2005 estimated that we would need about INR 1,160 per person per year to

provide the essential package of services. The HLEG report estimates that by 2022, we would have

achieved UHC, but at a cost of INR 5,145 per person per year (at current costs). Of this, the

government would have to spend 3,450 and the rest would be by the private sector. As stated, these

are estimates as there are many gaps in the data available to make such calculations. Some attempts

at calculating the total cost for achieving UHC is provided in Annex 2. Keeping in view, the range of

estimates that one is receiving and also that patients will still use the private sector for services in

the immediate future, INR 1500 per person per year will be a safe amount to start with. With time,

this amount will increase as the population coverage increases and as the services coverage

increases.

20

How does a state raise this amount? One must remember that the state is already spending

an average of about INR 500 per person per year on health services. So the state needs to increase

this by another 1000 rupees per person.

There are two options possible for a state. One is to allocate more money from taxes for

health care and then spend it effectively on the public health facilities. By strengthening the

government health services and providing better quality free health care, patients may shift from

the private sector to the government sector. This will reduce their OOP payments considerably

and protect them from financial catastrophe due to medical causes. NRHM tried this by infusing

more funds into the health system. The union health budget increased from Rs 8,086 crores

in 2004-05 to 21,680 crores in 2009-10 . The 12lh five year plan has also promised a substantial

increase in tax based funds. According to their calculation, the central government’s

contribution on health is expected to cross 300,000 crores while the state government v

also contribute about 700,000 crores for health services. The total contribution to healrh

expenditure from government sources is expected to cross 2% of GDP by 2017 and will be in the

range of INR 1,500 per person peryear.

Figure 6 : Health expenditure in India (2008) by source of financing.

One main challenge for the state will be toraiseits allocation to health care. Given that

most state governments have a deficit budget, and the tax: GDP ratio is only 17%, this may be

a valid objection. However, the health secretary can suggest some options to raise these

extra funds:

•

One obvious strategy is to allocate taxes from demerit goods (on alcohol and tobacco) for health care.

This will raise substantial funds to achieve UHC. While usually taxes on these goods are part of the

central excise and are collected by the central government, many states have started introducing entry

taxes on tobacco products.

21

•

The other option is to introduce a health cess, similarto the education cess. This can also raise substantial

resources for UHC.

•

There are many other (more radical) measures like transaction costs (for all financial transactions), etc.

The other option is to increase health insurance coverage among the populations. The important

point to note here is that schemes like RSBY, Rajeev Aarogyasri, Vajpayee Arogyashree and CM's

health insurance scheme are all financed by tax revenues. So they should be considered in that light.

Health insurance should be used to extend coverage rather than generate extra funds. For example,

by extending RSBY to the APL families, it is possible to increase the population coverage. Similarly,

by making health insurance mandatory for all the formal sector, one ensures that the population as

well as financial coverage is enhanced. So in our march towards UHC, we should use health

insurance not to raise funds, but to use people's contributions into a prepayment mechanism and

thereby increasing the coverage of UHC.

Some suggestions for such expansion are:

1.

Expand RSBY to APL populations through existing groups like trade union members, cooperative

society members; self-help group members, resident welfare associations, school children, etc.

The government can collect the premiums from the APL and thereby enhance the financing of

health care.

2.

Expand ESIS to cover the formal sector. Raise the salary limit from Rs 15,000 pm to Rs 150,000 pm.

This way most of the formal sector will have to contribute towards this ESIS fund and this fund

can be used to finance their health care as well asco-financethe RSBY scheme.

3.

Include outpatient services and tertiary health care to RSBY, so that patients get access to

comprehensive cover through one single scheme, rather than having multiple schemes and identity

cards.

To summarise, UHC should be financed using prepayment mechanisms along with pooling of the

collected funds. Direct payments at the time of illness should be converted to prepayments at all

cost. The amount required will depend on the services and the population coverage. We share two

potentially simple tools to arrive at the actual cost and the cost per capita for this expansion.

People will be protected from catastrophic health

expenditure if health care is financed by prepayments.

22

WHERE IS MY STATE ON THE PATH TO UHC?

One must visualize UHC as a goal towards which our society is moving. As stated earlier, there could

be many paths to the same goal, but what is important is that we start moving towards the goal. In

today’s environment, it is unacceptable that people are denied even basic health care because they

cannot afford it or households are impoverished because of high medical expenses for common

ailments.

To begin with, one needs to know where one is on the path to UHC. Is one's state nearing the goal or

is it far away from the goal. There have been many attempts to assess this, but most of these tools

are very complex and only not user-friendly. We propose a simple tool that may not capture the

minute details, but can give the policy maker a broad idea of where the state is. This tool uses

existing data that is easily available and gives a visual depiction of the position of health coverage

in a state. We have used this tool to depict the status of health coverage in India in this manual,

and the same can be used for each state.

We use six indicators to assess coverage, two for each of the dimensions. For the population

coverage, we assess the outpatient contact rate per capita per year and the admission rate per 1000

population per year. For the services coverage, we assess to what extent women are able to deliver

in institutions and what proportion of children are fully immunized by the 2nd year. For the financial

coverage, we calculate the amount of OOP payments made at the time of illness and also

the proportion of patients who did not have to make OOP payments when they sought health care.

All this is depicted in a spider diagram, where if one has achieved universal coverage, then all the

spokes will show 100%. And, to bring in the dimension of equity, we have two lines, one for the

riches quintile and the other for the poorest quintile.

23

If one uses this to analyse the status of UHC for India, we find that:

•

% of children (12 - 23 months) who have completed primary immunisation ideally should be 100%.

However, while children in the richest quintile have achieved 76% coverage, children among the poorest

families have only achieved 47%. This means that there is a gap in immunisation for the poorer segments

of the population. The same is the status for institutional deliveries. From this we can say that while service

coverage is good forthe rich, and affluent, there is a lot to be done for the poor.

•

When one looks at population coverage, one notes that people (both rich and poor) seem to have access

to outpatient services. However, when it comes to admissions, then the story is very different. Rich

patients have a higher chance of getting admitted compared to the poor patients.

•

And, the main reason for this is the OOP payments for health care. We have used "surgical care" just

because we had the data readily with us. NSSO data should give the researcher data on how many patients

received free treatment (for both outpatient and inpatient care) and how many had to pay OOP. This

clearly shows that this is the place that one needs to work on if we went to achieve UHC.

The template for filling up this data and creating a graph is provided in Annex 2. This is a good

starting point to identify gaps in the UHC that need immediate correction and also is a useful tool

to monitor the progress towards UHC.

24

HOW ARE THE SERVICES TO BE DELIVERED ?

India's health care delivery is a mix of public & private health sector practising diverse

systems of medicine. The provision of comprehensive health care by the public sector is a

responsibility shared by the state, central and local governments. More recently, under the NRHM,

the central government has emerged as an important financier of state health systems, while

encouraging the state governments to strengthen the provision of care.

It is clear from the previous chapter that while there are some populations who are not

receiving some services, the immediate issue to tackle is how to convert OOP payments into pre

payments. As stated earlier, it could be either by increasing the allocation for health services or

through a health insurance mechanism. While financing UHC may be easy, providing the necessary

services maybe more difficult. An example of this is given in the box below:

The current norms provide a PHC for 30,000 population. If all the outpatients had to be

seen by the PHC MO, then it would mean an average of 7 00 patients per day. Obviously

one MO cannot provide quality care to these patients AND conduct 1 - 2 deliveries a day,

supervise the ANMs, conduct school health visits, monitor the malnourished children in

the anganwadis, attend meetings at Block, District and Panchayat levels as well as

administer the PHC and manage the programmes. Especially ifone wants the PHC to be

providing 24x7 services. One would need at least three MOs at each PHC. In a state like

Karnataka, that would mean 4,000 new MOs, which may be difficult to find. Even with

reasonable salary and perquisites, Karnataka still has a high vacancy rate at the level of

PHCsMOs.

If one goes to the FRU level, the situation is even worse. Assuming that all normal

deliveries will happen at the PHC and only 15% that need specialized attention are

referred to the FRU, one can easily expect about 450 to 500 'complicated' deliveries in a

year. This has to be managed by a single obstetrician and is very difficult, especially if

one expects this obstetrician to also manage the outpatients, conduct tubectomy camps

and do night duties. Which means that one needs to recruit more obstetricians [and

anaesthetists) to the FRUs. Again, taking the example of Karnataka, in a recent drive to

fill up 600 specialist posts, the government advertised widely. Only about 120 came for

the interviews and 60 joined. If this is the situation in a doctor surplus state like

Karnataka, what will be the situation in otherstates?

Ifthe government wants to remain both the financier and the provider of health care, then it

can adopt various reforms like task shifting (introducing Rural Medical Assistants in place of MBBS

doctors; training MBBS MOs for providing CEmOC and LSAS, etc). This can be a short to medium

term solution, provided the state governments have the strength to counter the powerful IMA and

other medical lobbies.

One another option in terms of providing health care could be to use the existing private

health providers. They are available and it may make more sense to co-opt them rather than

confront them. The private sector practitioners range from General Practitioners (GPs) to the super

specialists, various types of Consultants, Nurses and Paramedics, Licentiates, Registered Medical

25

Practitioners (RMPs) and a variety of unqualified persons (quacks). The practitioners not having

any formal qualifications constitute the 'informal' sector. The above practitioners may practice

different systems of medicine, ranging from Allopathy to yoga. The institutions range from single

bed hospitals to large corporate hospitals, and medical centers, medical colleges, dispensaries,

clinics, polyclinics, physiotherapy and diagnostic centers, blood banks, etc. The private sector in

India has a dominant presence in the provisioning of medical care among other areas. Over 75 per

cent of the human resources, 68 per cent of an estimated 15,097 hospitals and 37 per cent of

623,819 total beds in the country are in the private sector. In such circumstances, no policy maker

can afford to ignore this rich resource.

One feasible option that has been tried in many countries is for the government to purchase

care from the private providers, especially for those services that are not provided by the

government. One little known example is the case of the National Health Service in the UK. While the

government finances the entire health care through tax revenues, it purchases care from the famous

general practitioners who are actually private practitioners. Similarly, the German government uses

social health insurance to finance health care in the country. It collects payroll contributions from

employees and employers, pools the funds together and then purchases care from both private GPs

as well as private hospitals. There are no or very few government facilities, the majority of providers

in this socialist country is from the private sector. In both the above examples, the main difference

between them and India is the strong regulatory framework that exists and is implemented

diligently. Thus there are rules on who can practice, where they can practice and what they can

practice. There are bodies that oversee the practice to ensure that the providers follow the

standards. And if providers do not comply with any of the rules and regulations, there are bodies

that take action. Hence the private sector in these countries is made to act for the public good.

Provi sion of care

Private

Public

Financing of care

Totally

government

provided. This requires:

Public

•

•

•

•

Private

funded

and

Enough revenue from taxes

Enough

resources

(human,

infrastructure,

medicine

and

consumables)

Reforms, especially vis-a-vis human

resources, medicines,

A good governance structure that

can make the staff accountable to

deliver the desired outputs and

outcomes.

Not desirable

Purchasing care from the private sector.

This requires:

•

•

Adequate private sector

Capacity of the government to

actually

purchase

care

and

implement

the

necessary

conditions.

•

Strong regulatory mechanisms to

ensure that the private sector

provides the required services

Current status - not desirable at all.

From the above table, it is clear that the financing of health care should be by the government,

either through taxes or through insurance premiums. There is no doubt about that. Financing by

individual households is not acceptable in today's environment. Then the debate is about provision

of care. This can be provided by the government, or by the private ora mix of the two.

26

The important question that the state needs to answer is - do we expect the government

health services to provide all the services? Does it have the resources in terms of qualified

professionals? Or do we need to purchase services from the private sector? In many instances, there

may be enough resources within the government to provide the services. However, in other

instances, in the short to medium term, it may be more efficient to purchase care from the private

sector. A good example of this is immunisation services in urban areas. It may take a lot of resources

and time to establish a network of primary health centres to cover the entire city. However, the

government can identify select private practitioners and provide them with the necessary

equipment (refrigerator, 1LR and UPS backup) so that they can store the vaccines and provide

immunisation services to the children in their catchment area.

The assumption here is that all state governments have its own health services in place with

a primary health centre, a community health centre and a hospital for defined populations. And that

there is a thriving private health sector whose services can be purchased.

For the sake ofclarity, we would like to define some terms that will be used in the coming sections.

Government health providers mean the Primary Health Centres, the Community Health Centres,

the Taluk Hospitals, the District hospitals, the Government medical colleges, the government

maternity centres, the Urban Health Centres, etc.

Private health providers mean the formal (Allopathic orAYUSH) practitioners like single doctor

clinics, nursing homes, polyclinics, multi-speciality hospitals, single speciality hospitals, private

medical college hospitals, corporate hospitals, etc.

Purchaser of care is the government health directorate (or department) who purchases care from

either the government or the private health providers. One may debate the artificial divide between

government health providers and the purchasers of care, but this is necessary as they have two

different roles.

However, purchasing care is not easy and requires a lot of skills and knowledge. We have

tried to equip the reader with some information about various ways of purchasing care. Details on

howto purchase care is provided in Table 4 and Annex 3.

27

Table 4 : Various mechanisms for purchasing health care from the private sector

Purchasing

mechanism

Ideal for purchasing

Remarks

From

The following

services

Through salaries

Government health

providers

l*/2* / 3*

This is the usual mechanism

used by most governments

Payment for

performance

Government health

providers

1* / 2* / 3*

This incentivises

performance in government

health facilities

Capitation method

Government /

Private health

providers

1*

Requi res the provider to

take responsibility of a

population and the

purchaser to calculate the

cost of the services to be

purchased

Diagnosis related

groups (DRG)

Government /

Private health

providers

2* / 3*

Requires the purchaser to

calculate the cost of the

services to be purchased

Per diems

Government /

Private health

providers

2* /3* usually medical

care

Requires the purchaser to

calculate the cost per day of

the services to be purchased

Fee for service

Government /

Private health

providers

l*/2*/3*

Not recommended as it has

the potential for escalating

costs

Vouchers

Government /

Private health

providers

1* / 2* / 3*

Health equity funds Government /

Private health

providers

2* / 3*

Contracting in of

clinical services

Government health

providers

1* /2* /3*

Contracting out of

facilities (PHC /

CHC)

Government health

providers

1* / 2* / 3*

Useful way of channelizing

social assistance funds

1* / 2* / 3* = primary, secondary and tertiary care respectively.

As one notes from the above table, the moment that the private sector is involved, it is

imperative that the cost of the service is obtained. This will prevent frauds and cost escalations.

Also one can mix and match these methods; for example a government can decide to

purchase primary care services from existing government providers through a salary mechanism

and secondary care services from private providers through a DRG mechanism.

28

Table 5 : Some examples of how other countries purchase care

Hospital care

Primary health care

Name of country

Provider

Payment

mechanism

Provider

Payment

mechanism

Thailand

Government

Capitation

Government

Capitation

Indonesia

Government

Salary + Capitation

Government

Fee for service

Canada

Private

Fee for service

Government

Salary

Taiwan

Private

Fee for service

Private

Fee for service

United Kingdom

Private

Capitation

Government

Salary

Germany

Private

Capitation

Private

Salary

However, it is important that the department has a separate cell to prepare the contracts

with the private sector, to monitor the utilisation of the scheme and also to ensure that it remains

cashless.

To conclude, financing and provision of care by the government has its advantages and

disadvantages. Also, given the epidemiological and demographic transition, the challenges of

provision may be too many to be handled by the government alone. Instead, it would be more

efficient to purchase care from the private sector, so that services reach the needy and vulnerable

as soon as possible.

If India wants to achieve UHC by 2022, it would be advisable to use the existing

private health providers to supplement the government efforts. The government trying

to provide all the services may not be feasible in the short to medium term.

29

WHAT ELSE IS REQUIRED TO ACHIEVE UHC?

While most of the debate and discussion on UHC has been limited to financing UHC and also

on the WHO cube, one should not ignore certain important steps that are required to ensure that

UHC is achieved.

Governance

Most countries that started on the path to UHC introduced enabling legislation that ensured

that the government could move ahead without too many obstacles. For example, Mexico

introduced a series of regulatory acts during the SSPH reforms. These varied from regulation of drug

safety to certification of providers. These laws enabled the government to ensure that the measures

that they introduced were effective.

Monitoring

This is a crucial activity if a country wants to achieve UHC. Monitoring can be through routine

data or from special studies. Thailand's research unit regularly conducted studies to monitor access

and utilisation of services and the extent to which patients incurred out-of-pocket payments. This

body of knowledge helped the government introduce a watertight plan for UHC soon after Mr.

Thaksin was elected in 2001. Also, what is important, especially in a country like India is the shift

from input based monitoring to outcome oriented information system and performance based

monitoring.

Support services

It is not enough to provide resources for UHC, this should be accompanied by expansion

of the support services like supply of medicines, use of technology and production of allied

health staff.

Quality and equity

In the rush to achieve UHC, it is easy to lose sight of quality and equity. To prevent this,

indicators to measure these should be part of the information system and should be monitored

incisively. The policy makers should monitor to ensure that the poorest are not the ones falling

through the safety net. In an effort to cut cost and be more efficient, quality is not compromised.

30

CONCLUSIONS

It is not acceptable that lakhs of mothers and children die every year because of

inadequate health services in a country like India. It is a shame that millions of Indians are

impoverished every year because of medical expenses. It is a matter of concern that every year

lakhs of young hypertensive patients end up with a stroke and become economically unproductive.

It is time that we come together and put an end to this unnecessary suffering.

The tools are there, the resources are available, it is a question of bringing all this

together for a vision where every single Indian will have affordable and equitable access to quality

health services. And, in this journey, we cannot afford to delay any further.

If we decide to move towards UHC, then there are certain basic changes we need to bring

into the existing health systems. The most important is the way of thinking. We need to go beyond

disease control programmes and tailor our services to the needs of the people. And, the people

(like all of us] want assured ambulatory, emergency and inpatient care that is affordable. The

second change that we need to bring is to infuse more resources into the health services. And, finally

we need to stop ignoring a huge resource that exists within our country and needs to be

used, the private sector. Having said that, we need to introduce important legislation to regulate

the private sector before using them, so that they perform for the public good rather than for

profit. One legislation that needs to be introduced into all the states immediately is the

Clinical Establishment Act. Until and unless we define the private sector, it will be difficult for us to

work with them.

We have been guilty of focussing on the poor in this manual. We have not come up

with possibilities for the middle class or the rich. We have neglected them purposely to keep

this manual short. However, they are important stakeholders, and needs to be considered when we

make plans for UHC in our state.

This manual is a work in progress. It is not the ultimate document on how India can

achieve UHC. It is the outcome from years of experience in the field and from observing the way

the Indian health system functions. We recognise that much of this experience may be different

in different contexts and if seen by different lens. Hence, we welcome suggestions, comments,

advise, opinions from our learned and experienced colleagues so that we can improve on the

second edition. Please do write to us atmail@iphindia.org

31

References

1.

Planning Commission. Health Chapter®: 12th Plan. 12th Five Year Plan. New Delhi:

Governmentof India; 2012. p. 1-71.

2.

Carrin G, James C, Evans D. Achieving universal health coverage: developing the health

financing system. World Health.Geneva; 2005 p. 1-11.

3.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health

equity through action on the social determinants of health.Geneva; 2008 p. 1-256.

4.

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008. Primary Health Care: Now

more than ever. Geneva: WHO; 2008. p. 1-148.

5.

World Health Organization. The World Health Report: health systems financing: the path

to universal coverage. Geneva; 2010 p. 1-128.

6.

Barnighausen T, Sauerborn R. One hundred and eighteen years of the German health

insurance system: are there any lessons for mi. Social Science and Medicine. Department

of Tropical Hygiene and Public Health, Medical School, University of Heidelberg, Germany

till_baernighausen@yahoocom; 2002 May;54:1559-87.

7.

Bang A, Chatterjee M, Dasgupta J, Garg A, Jain Y, Shiva kumar A, et al. High level expert

group report on Universal Health Coverage for India. Bangalore; 2012 p. 1-343.

8.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Report of the National Commission on

Macroeconomics and Health.Health (San Francisco]. New Delhi: Government of India;

2005.p. 1-192.

9.

National sample survey organisation. Morbidity, Health Care and the condition of the

aged.Health Care. New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation;

2006. p. 1-482.

10.

World Health Organization. Definition of health services [Internet], Available from:

(http://www.who.int/topics/health_services/en/ )

11.

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000. Health systems: Improving

performance. The World Health Report 2000. Geneva: WHO; 2000. p. 1-215.

12.

Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Pinto AD, Sharma A, Bharaj G, Kumar V, et al. The cost of universal

health care in India; a model based estimate. PloS one [Internet]. 2012 Jan [cited 2012

Apr 21];7(l):l-9.

13.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Annual report to the people on health. New Delhi;

2010p. 1-55.

/, A,/ Lrnc. ■

(p(

Koramanga

32

Annex 1-Health indicators in India, vis-a-vis the MDG goals

Initiatives, like the NRHM and the RSBY are efforts by the government of India to provide health care

to its citizens with minimal financial burden for the beneficiary. However, even today, inspite of all

these measures, the health status of Indians is disappointing. Results from various studies show

that we are still far away from the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). This is depicted in the

figures below. These aggregate figures hide vast disparities between states; between social,

geographical and economic sub-groups within states and between programmes.

33

Eighty per cent of Indians still use the private health sector for outpatient care, many still

spend money even for 'free' government health services and more than 60 million are impoverished

every year because of high medical expenses. While BPL families are benefitting from the RSBY

to some extent, they still need to make out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for outpatient care. On the

other hand, there is no such protection for the near poor or for the low and middle-income families.

Even basic services like safe drinking water, sanitary toilets and primary immunization are

not available for the 'bottom of the pyramid'. A recent UNICEF report states that only 50% of

tribal children are fully immunized and that only 40% of pregnant women in the poorest quintile

could deliver in a facility.

Figure 9 : Maternal mortality ratio in India

Source: SRS bulletins.

MDG target for India for 2015 is 1.1.

34

Annex 2 - Estimating the cost of UHC

How much will these services cost? This is the million-dollar question that the finance department

will ask and which the health secretary needs to answer. This will depend on the services that need

to be strengthened and the extra population that needs to be covered. In the following table, we

share some of the calculations made by the National Commission on Macro-economics and health

(NCMH). While these figures are of 2005, the process of calculation can help each state to estimate

the costs for extending services to new population groups, or for introducing new services into

existing populations. Note that Table 5 has only a few conditions; the NCMH Report has a more

extensive list. The states can use this format, with the caveat that the disease burden estimations

and the cost calculations are based on 2005 figures. This (especially the cost) may have changed

over time, so the element of inflation needs to be factored in. Also the disease burden estimations

were done on a national level, it will vary from state to state. For example, the burden of malaria will

be higher among the eastern and north-eastern states as compared to southern and western states.

So each state needs to calculate its own burden from the existing data that is available. The purpose