3103.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

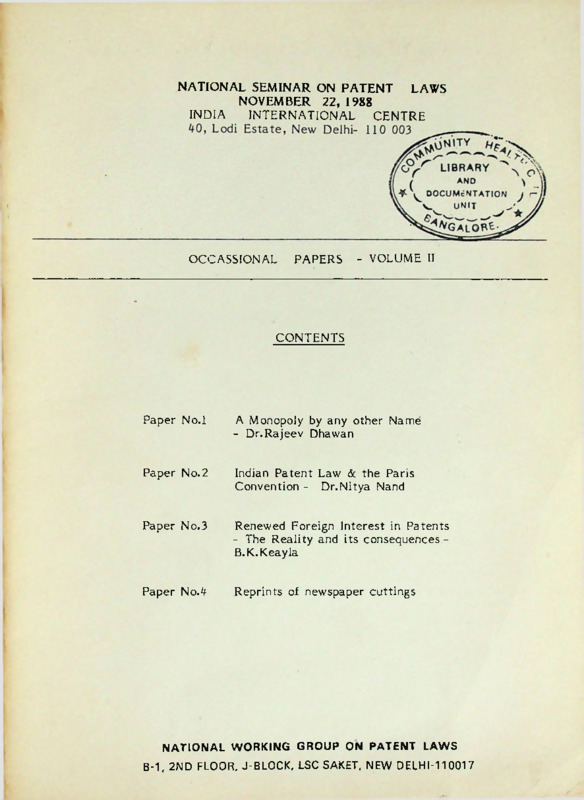

NATIONAL SEMINAR ON PATENT

NOVEMBER 22, 1988

INDIA

INTERNATIONAL

OCCASSIONAL

PAPERS

LAWS

CENTRE

- VOLUME II

CONTENTS

Paper No.l

A Monopoly by any other Name

- Dr.Rajeev Dhawan

Paper No.2

Indian Patent Law & the Paris

Convention - Dr.Nitya Nand

Paper No.3

Renewed Foreign Interest in Patents

- The Reality and its consequences B.K.Keayla

Paper No.4

Reprints of newspaper cuttings

NATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON PATENT LAWS

B-1, 2ND FLOOR, J-BLOCK, LSC SAKET, NEW DELHI-110017

a mo

U*».

.{JNITY HEALTH CEL’

-

326 V Main, I Block Koramana

Patent law is i.; i he news again. This time at the

behest of the multi-nationals supported by powerful

nations hungry-even desparately so - for markets over

which they want exclusive monopolies. At the Uruguay

Round of GATT Multinational Trade Negoti-at ions in the

June 1988, a collective statement, produced after two

years of deliberation, was presented by European, American

and Japanese business. Entitled, "Basic framework of GATT

Provisions on intellectual Property", its purposes were

to take

"...two important steps ...(a) the creation of an

effective deterrent to'international trade in goods

where there is an infringement of intellectual

property rights; and (b) the adoption and implementation

of adequate and effective rules for the protection

of -intellectual property”

It is easy_ to surmise: for whose benefit?- dnd, to what end?

Meanwhile the lobbies have been busy to persuade India to

change its relatively recently enacted Patents Act 1970.

This conspiracy of stealth is made possible by the

apparent remoteness of the patent law from the lives of

the people. It is rendered all the more obscure when

central issue is posed in the mystifying form: Should India

join the Paris Convention? What is hidden from the public

is the impact of all this on their lives: more expensive

medicine, a hike in prices of items using chemicals and

fertilizers, a strengthening of product monopolies all round

and the marginilization of India's own research and

development (R&.D) efforts.

The new moves are not' an attempt at persuasion. They

are backed by the threat of a protectionist trade war; and,

much else besides.

The Paris Convention

The Paris Convention 1883 was part of a centuries

old trend of the Western nations to try to carve out areas

of the world for exclusive exploitation. If the Bull of

Alexander IV divided the world into two (giving the East

to Portugal and the West to Spain) and various grants

(like those to the East India Company) gave exclusive

trade rights to chosen national companies, the Paris

Convention 1883 was an imperial splitting up of the

world markets to feed the expanding demands of an

acquisitive capitalism.

What the Paris Convention - amended in 1900 (Brussels)

1925 (The Hague), 1934 (London), 1958 (Lisbon) and 1967

(Stockholm) - did was to interpret "industrial property

in the broadest sense... not only to industry and commerce

proper but likewise to agricultural and extractive indus

tries and to all manufactured and natural products"

* Director, public Interest Legal Support

Research Centre (PILSARC)

. . . .2

(Article 1(3). National of signatory nations could by

the simple expedient of taking out a patent create an

exclusive monopoly for the product and/or the process

by which it was made. All this without even committing

oneself to producing the product or using that process

in the country for which that market is claimed (Article

5 (non-forfeiture). A stake could be claimed to the

markets of the member nations ‘by filing in any one nation

first (Article 4 - right to priority); and, all the rest

within 12 months. And, to make sure that the less

developed nations did not keep rich and powerful

foreigners out, equality of national treatment was

proclaimed (Article 2 and 3). What provisions! Guaranteed

markets for a substantial period of time in countries

where the monopoly holder did not have to spend a paisa

manufacturing the product! The grant of a patent was

compulsory even.if sale restrictions were imposed round

the product (Article 4 quater ). A monopoly could also

be built round the product from a patented process (Article

5 quater ). Compulsory licensing, if the patent was not used

for three years, and revocation, two years later, was possible

unless the "patentee could justify) his. inaction for legi

timate reasons" (Article 5(4). All this in the name of the

poor inventor (Article 4 ter) whose creativity was - in

virtually all cases - absorbed or cheaply bought out by

mighty enterprizes.

II

The case for India joining the Paris Convention was

supported by the Bakshi Tek Chand Report of the Patents

Enouiry Committee 1948-50 (prs 265-70 pp 110-111) ; but,

decisively rejected by the Ayyangar Committee Report on

the Revision of Patents Law 1959 (prs 304-8 pp 117-9).

Since then India has not looked back. The patents Act 1970

was a genuinely indigenous response, following from a

move in the United Nations by Brazil in 1961 to reagitate

the issue of the world patents system. From 1974 UNCTAD

initiated further discussions from the point of view of

LDCs. But, the rich and powerful nations have struck back

both publicly, as evidenced by the document to .GATT (1988),

and, more covertly through the silent but powerfully

effective means of business and official diplomacy. The

impact of this diplomacy has been felt in India.Responding

to a parliamentary question on 25 April 1984, the Minister

of State accepted that there was pressure from the World

Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) to join the

Convention; but that no*decision had been taken yet (48

L.S.D. (7d.)153-4) Even though, it was made clear pharma

ceuticals would be protected (ibid; cols 77-8)’, mischief

was afoot. But, WIPO pressure is only a constituent part

of a rnfich more uncomprizing pressure is being brought to

bear on the government now.

3

India's own law is the product of much deliberation.

Two Committees (Bakshi Tekchand, 1950; Ayyangar,1959);

three Bills (1953, 1965 and 1967), two Joint Committees

of Parliament (1965-7 and 1968-70) and long debates in

parliament on the Patents Act 1970 (44 L.S.D. (4d.)cols.

1-164; (29 August 1970); 73 R.S.D. 39-126(3 September 1970)

One has only to skim over the Joint Committee Reports to

see how extensive the multi-national lobbies were. Indian

markets were ripe for caputre; and a new patent law was

the means to achieve that end.

Ill

India's patent law seems to give the public interest

priority over the rights of the individual inventor (in

this case subsumed by rich manufacturers and multinationals after all, it is only multi-nationals who seek trans-national

markets). In a spirit entirely at variance with the Paris

Convention or, for that matter, multi-national demand Indian legislation.seeks to ensure not only that inventions

are encouraged but "worked on a commercial scale (in India)

... to the fullest extent that is reasonably practicable

and without delay; and... that they are not'granted merely

to enable patentees to enjoy a monopoly for importation

of the patented article" (Section 83).-That the Act falls

short of this declared ideal is another matter.

And so, many exceptions are made. Patents dealing

with atomic energy cannot be granted and liable to be

revoked (Sections 4 and 65 ; also Raytheon A.R. 1974

Cal. 336).Patents for food, medicine and drugs will last

7 tears from the date of the patent, as opposed to the

usual 14 (Section 53), Such food, medicine and drugs along

with those for chemical processes shall be just process and

not product patents (Section 5). The import monopoly for

products and exclusive use of processes can be breached by

government for its own use (Section 47). A patent may be

revoked in the public interest if "a patent or the mode in

which it is excercised is mischevious to the State or

generally prejudicial to the public" (Section 66). Those

who do not work their patents in India for 3 years can be

forced to grant compulsory licenses if the "reasonable

requirements of the public ... have not been satisfied or

the ...invention is not available to the public at a

reasonable price (Section 84 and 85). Certain patents dealing

with food, drugs, medicine and chemical processes will be

automatically endorsed with "licenses of right" and are

vulnerable to a form of compulsory licensing straightaway

(Section 86). Two years after a compulsory licence has been

granted, if the requirements of the public remain unsatisfied

the patent may be revoked (Section 89).

This scheme in the Indian Patents Act 1970 differs

greatly from the Paris Convention. Its purpose is to prevent

monopolies, encourage manufacture in India, provide specially

for food, drugs, medicine and chemicals and give over

riding importance to the public interest. Yet, far from

falling short of reasonable standards, many feel that the

Indian legislation does not go far enough in the elimination

of foreign monopolies and protecting the justifiable interest

. . .4

of the public

IV

The truth about using patent law for creating

monopolies for foreigners is much worse than is normally

imagined. From 1856 when the first protection to patents

was given, Indians filed few applications. None out of 33

in 1856, 45 out of 492 in 1900; 62 out of 667 (though

199 originated in India) in 1910; 345 out of 1725 (399

originating in India)in 1949 (Bakshi Tek Chand Report

(1950) 121)were filed by Indians. Since Independence

non'-Indians dwarf Indians for applications for patents

(1950:81%; 1955:87.1%; 1960:85.3%; 1965: 85.4%, 1970:

78.3%). (Ayyangar Report (p 370) and Annual Reports of

the Controller). Under the Patents Act 1970, the position

has not altered (1972-3:68.6%; 1976-77:56.8%); 1076-7:71.8%)

(ibid:Annual Reports). In 1986-87, the number of foreign

patents sealed in India were 74 %. For that year, 83.4%

of the total patents in force in India were foreign owned.

And, if this picture is not striking enough, it should be

remembered that even Indian owned patents are likely to

be manipulated by foreign business; or be the product

of collaborative ventures. Indeed, foreign ownership of

patents registered in India has to be understood again’st

the backdrop of increasing foreign collaborative ventures.

The largest number of patent applications in India came from

Americans. Further out of 67 foreign collaborations in May

1988, 43 were technical, 4 drawing and design and 20 financial.

Why invest money when you can sell closely guarded knowledge

profitably ?

There are many problems with the operation of the

patent law. In 1986-87, 10,363 applications had to be

dealt with by the patent office, out of which 6874 had

to be carried over from the previous year. 4874 applications

were examined, 1006 abandoned for legal reasons and, 5250

carried over to the next year and only 1706 accepted during

the year. It would appear that the law courts are not the

only institutions plagued with arrears of cases!

But, apart from these management difficulties, I

think that there is an incomplete appreciation of the

social and public purposes behind the Patents Act 1970.

Let me take one complex but important example. In India,

only a process patent is given for food, drugs, medicine

and chemical processes. Both the Joint Committee on the

1965 Bill (see pr. 19 p.viii) and the 1967 Bill (see pr.18

and 25 p. vii) categorically refused to accept that a

product monopoly can be built out of a process patent

in respect of products made from that process. Shri

Dandekar tried to introduce an amendment to make such a

monopoly possible on the floor of the Lok Sabha (44 L.S.D.

(4 d.) 95-8(29 August 1970)); but this move was decisively

rejected by the Minister, Shri Dinesh Singh (ibid:col 102).

Yet the jurisprudence on patent law continues to build such

product monopolies into process patents as shown by Justice

Mukharji's views in the Imperial Chemical Industries case

(A.I.R. 1978 Calcutta 77). Seemingly, technical, the failure

. . .5

:

5 :

is one of juristic theory - a failure to fully embrace

the public interest implications, and philosophy, of

the Patent Act 1970 itself. Alongside, as my friend,

Upendra Baxi,points out by reference to judgements

like those in the Monsan to (A.I.R. 1986 S.C. 712), even

where patents are revoked for want of subject matter,

the Indian system of granting stay orders results in giving

patents monopolies a life that they should never have had

in the first place,as the cases drag through our courts.

The real problem lies deeper. Very few countries have

done as much work and thinking about the law of patent as

India. At first, both our juristic thinking as well as

political thinking about this subject was imitative, drawing

inspiration from the English law and embarassed that our law

was not following "progressive" practice elsewhere in the

world. But, since the early sixties, we have looked at

these questions anew; and, sought to put them in a challenging

and interesting framework. Yet the law remains ineffective

in ways that in itiate against the public interest. Although

we have enabled cheaper food, drugs, medicine and chemicals,

they are still expensive. We have not been able to stop

foreign domination of the use of our patent law. Patent

remains a powerful instrument to construct monopolies; and

is relatively free from the operation of the monopolies and

restrictive practices law. (Sections 15, 36D', 37, 39 of. the

MRTP Act 1969). Yet, time and time again, we are called upon

to revise our conceptions in favour of 'a more liberal law,

more inclined to absolutist notions'of private property

and, ostensibly, protecting the creativity of the inventor.

The poor inventor, alas, in most cases remains relatively

poor. The real protagonists are the big companies who having already reaped up tax benefits for the R&D work of

their inadequately compensated employees - threaten to make

their research less available; and use their political

muscle to threaten financial and economic disaster. We

need to get back to our debate, seeking support from those

nations who are similarly placed. Instead, we' seem to be

getting ineluctably drawn into their debate; and, from

then on, into the inevitable monopolistic consequences that

follow.

]

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.2

INDIAN PATENT LAW AND THE PARIS CONVENTION

DR.NITYA NAND

It is understood that a change in the existing Indian patent laws and

India's joining the Paris Convention is under active consideration of the

Government of India. Some articles favouring India's accession to the Paris

Convention have recently appeared in the Press (Times of India, 7th December,

1985). The present write-up makes an analysis of the provisions of the

Paris Convention and discusses the set backs. India's accession to the

Convention would cause, to the industry in general and the chemical and

drug industries in particular.

There is no getting away from the fact that the developed and

developing countries are "unequals" in industrial strength, and when the

present patent systems were designed to protect the interests of

industrialised countries it would be difficult to reconcile the interests

of both in the same- system.

International Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property or

Paris Convention, as it is popularly known was first signed in 1883 as a

multi-lateral treaty among 11 nations. Since then it has been revised

six times, the last being 1967 at Stockholm, each revision superseding the

earlier version. The Convention could attract in more than 100 years of

its existence a total of just 96 members and suprisingly, till date, has no

Preamble. It means, in simpler term, it has no explicit statement regarding

its objectives and does not contain at any place the importance of national

and consumer interest nor any specific statement beneficial to developing

countries in any way.

The convention has a total of 30 Articles and the Article 1 defines

the scope of Industrial Property. It includes all manufactured or natural

products and encompasses Patents of all types, viz. fresh, importation,

improvements, addition etq. It covers all spheres of industrial activity.

The status of industrial development of any country, developing or

developed, is always measured in terms of the strength of its indigenous

industry and not that of the multinationals operating in that country.

India's tenth position among the industrialized nations and UNIDO's

placement of India in the list of countries having a well developed drug

industry speaks well of the progress made by the indigenous national

sector of our drug industry. The era of rapid progress of Indian industries

in general, and of its chemical and drugs sector in particular, got greatly

accelerated after the enactment of the Indian Patents Act, 1970. This

single act of our Government put the Indian drug industry on the threshold

of self-reliance, removed our dependence on imports of drugs and encouraged

local industry to develop and strengthen its R <5c D base.

The strength of the Patents Act of 1970 are its favourable provisions

for compulsory licensing, automatic licences of rights, grant of process

patents only and reduction in period of protection to only 5 years after

sealing of the patent. All these will get nullified once we sign the convention.

The provisions of the convention are so heavily weighted in favour of foreign

patent holders that there are virtually no provisions regarding the obligations

of the patentee, concept of public interest and the rights of the state which

grants patents. Under Article 5 (and clauses, sub-clauses thereof) of the

Convention a patentee can avoid commercial production of its process for

a long period and monopolise import of the products as the provision of

compulsory licensing is rather weak and forfeiture almost impossible.

Article 5A(1) States explicity "Importation by the patentee into the coun try,

the articles patented in any of the Convention countries, shall not entail

forfeiture of the patent". This provision encourages importation of patented

product rather than taking up of the commercial production in the country of

patent grant. At no place the Convention requires compulsorily the working

of the patents. Furthermore, Article 5B states that the protection of indus trial designs shall not, under any circumstances, be subject to any forfeiture,

either by reason of failure to work or by reason of the importation. Article 5

alongwith its clauses and sub -clauses is so favourable to patentees that for

any developing country it is impossible to break the stranglehold of patentee

having vested interests. The provisions of this article leave no scope for any

indigenous industry to develop and operate.

The Convention is so much titled in favour of developed countries that

still almost half of the developing world is out of it. The accession to this

Convention does not end a developing country's, like India, isolation but makes

it recipient to the technology which the patentee wants to transfer and not

the one which the developing convention country wants. And the terms of

this transfer are also dictated by the patentee and not by the recipient. In

India's case not joining Convention has in no way deterred the flow of technology

even the sophisticated ones. The figures in this regard are explicit enough.

The number of collaborations for technology transfer have gone up from 183

in 1970 to 359 in 1974, 526 in 1980, 673 in 1983, 756 in 1984 and 1236 in 1985.

During the current financial year there has been a further increase in foreign

collaborations and that too from the most advanced countries USA and West

Germany. Thus this depends more on Government licensing rather than the

Convention. Many articles of the Paris Convention are amenable to different

interpretations and this will lead to unnecessary litigation and that too many

a time in the courts of other countries, which in turn, will lead to outflow of

scarce foreign exchange. Some such Articles (alongwith clauses, subclauses

thereof) are 4^,6,7,8,9,10,20,25,28, etc. Even our programmes for atomic

energy and power development will be jeopardised as we can be dragged into

international courts for infringement of some of the components used in

atomic power plants etc.

The interested parties are advancing the argument that a participating

country is obliged to apply its own laws to the inventions of the nationals

of other convention countries only with some minimum rules. What are

these so called, minimum rules ? Article 25 of the Convention states clearly

that the country joining the Convention will un dertake measures necessary

...3/

to ensure the application of this Convention. Moreover, sections ‘fS and 99

of the Indian Patents Act are not in harmony with Article 10 bis of the

Paris Convention which states that the countries signatory to the Convention

are bound to assure to the nationals of other member countries effective

protection against "unfair competition". It is feared, if India signs this

Convention most of the modern drugs available now will disappear from the

Indian markets as the foreign patent holder, on the basis of their priority

claims in their home countries (as applicable to all Convention countries)

will file cases in courts against the local manufacturers and stop production

by getting injunctions.

Application of Article 8 of the Convention which reads that a trade

name shall be protected in all the Convention countries without the necessity

of filing or registration whether or not it forms part of a trademark, read

with Article 4 which gives priority from the date on which the first appli cation in the home country was filed, will again lead to a chaos in drug

production as everry foreign patentee will start claiming priority of his

product based upon filing of the first application and would also bring their

own trade (brand) names

Joining the Convention, in no way, going to improve the technological

capabilities of our indigenous sector, these capabilities are already self evident. Our drug manufacturing units, through the liberal provisions of

Patents Act of 1970, are producing sophiaticated drugs of internationally

acceptable standards, e.g. nifedipine, hydrochlorthiazide, diloxamide furoate,

ethambutol, tinidazole rifampicin, all without the help of foreign technologies .

Moreover, many of our drug firms (national sector) have obtained Food and

Drugs Administration's approval for their manufacturing facilities and standards,

again without the help of any foreign technology. Such a situation, a flourishing

and committed national sector, would certainly not have been possible had

India joined the Paris Convention.

The crux of the matter is how India can achieve further Industrial growth

to meet its ever burdening domestic demand and create potential for export.

It hardly needs emphsis that to become industrially strong we have to be

self-reliant in technology and in resources both in terms of materials,

technologists and scientists. By joining the Convention we will only open

the flood-gates to foreign patent holders which would then start a chain

of litigation with indigenous firms. Articles 4,8,9 and 10 (some specific

clauses thereof) are few such ones, open to any vested interpretation.

Almost 98 per cent of the new (or first time) patents filed world over every

year are from the developed countries and just 1 per cent are from

developing countries. This will surely be a case of one-way traffic where

all the advantage would lie with the foreign patentees but with minimum

of risk. The convention gives reverse system of preferences for foreign

patent holders as against Indian Nationals.

How much fair the Paris Convention is to the developing countries

has been so well illustrated in the following para from UNCTAD's report on

"International Patent System." "Since its inception the Convention has grown

haphazardly. Neither at the time of its adoption nor during its six subsequent

revisions has the protection of specific interests of developing countries

found any reflec-tion in it.

The Convention itself lacks structural homogeneity: differences in the

types of members of the Convention and of its various Acts; differences

in the types of industrial property dealt with and in the possibility of

accession to one or another set of its articles. The asymmetry inherent

in its provisions-detailed obligation on countries versus feeble reference

to control of private monopolies for safeguarding public interest;

independence of patents with respect to countries but dependence of

countries with respect to patents; and speed of entry into the convention

contrasted with slowness of exit-work towards making the Convention

serve as an instrument of consolidating private rights of patentees without

ensuring equivalent obligations on them in public interests".

Patent system has been used by highly industrialized countries to

restrict the development of indigenous industry in the developing countries.

It was oh account of this consideration that Government of India took the

initiative of modifying its 1911 Patents law and the new Patents Act 1970

having reduced life span for patent protection, in the vital fields of

insectisides, pesticides, liberal provisions for compulsory licensing and

grant of process patent only for chemicals & drugs was enacted. Any change

in this set-up, as is being planned now, should be carefully considered with

all its implications.

The Government should not under the pressure of vested interests

go back on the modifications made in the old patent Act of 1911 and join

the Paris Convention. This will be a retrograde step and will have serious

repercussions on the national sector of the pharmaceutical and chemical

industries. Considering that it took almost 20 years of discussion and debate

in various forums before the 1970 Patent Act was enacted by the Parliament.

No change should be made without public debate and consultations with

scientists and technologists. It is the 1970 Patents Act which suits our

interest most and any deviation from it will benefit the vested interests

only. Once we accede to Paris Convention there will be no going back,

it will take a minimum of six years, to get out of it, by which time we would

have seen the end of many industries.

DR. NITYA' NAND

Former Director,

Central Drug Research Institute; and

Chairman,

National Working Group On Patent Laws

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.3

RENEWED FOREIGN INTEREST IN PATENTS

THE REALITY AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

B.K. KEAYLA

International interest in the law and policy relating to patents

has

taken many forms. In the years leading up to the

Paris Convention (1883) till the 1960s, the focus of attention

was the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial

Property and its subsequent amendments in 1900, 1911, 1925,

1934, 1958 and 1967. Since the Paris Convention was avowedly

directed to creating import monopolies, for manufacturers

and industrialists seeking markets abroad (without requiring

them to manufacture in the country sought to be exploited

as a market), nations were exhorted to join the'Paris Con vention in an international spirit of good will and modernity.'

Since the early 1960's concerted effort was made by Less

Developed Countries (LDC) to re -examine the true basis of

this good will. This has led to a re -consideration of these

issues through the aegis of the United Nations and UNCTAD.

Meanwhile, the campaign for joining the Paris Convention

continues.

A much more aggressive initiative has been launched by

European, American and Japanese Communities in an important

submission made at the Uruguay Round of the General Agree ment on Trade and Tariffs (GATT). Supported by the Inte llectual Property Committee, (a coalition of 13 major U.S.

Corporations) the Union of Industrial and Employers Confede rations of Europe and the Japan federation of Economic

Organisations (KE1DANRAN), an overhaul of the law of Inter national Patent System has been proposed to

" eliminate trade distortions caused by

infringement of and other misappro priation of intellectual property".

Needless to say, the trade distortions and'consequential effects

created by the Patent System is not given any real consideration.

A brief note below outlines some of the implications of some

of the proposals.

I.

FOREIGN INTEREST

A.

The foreign interests for the developed countries are using

the forum of GATT negotiations to pressurise developing

countries including India to make substantive changes in

their existing Patent Laws.

B.

The U.S.A., European and Japanese Business Communities

contend that the Intellectual Property Protection available

in India and certain countties is inadequate and also in effective against infringements. Many of these countries

in their earlier stages of development either had none or

weak patent legislation.

C.

They demand that patentability should cover, without dis crimination, any new industrially applicable products and

processes.

They want this right to be so provided that others are

precluded from manufacture, use or sale of the patented

invention and patented process.

They also want :

20 years period for Patent life.

Patent not to be revoked .for non - working.

Where for justified legal, technical or commercial

reasons patent is not worked but importation is

authorised, the requirements of working of patent

should be treated as satisfied.

Reversal of burden of proof should be provided

for against infringements.

In short, exclusive reservation of markets is being demanded

for patented products/processes.

’II.

INDIAN PATENT SYSTEM

A.

The Indian Patent System was developed and enacted after

prolonged indepth study when it was found that the Patent

Holders were taking too much undue advantage of their

superior monopolistic position and charging very high prices

to gain enormous profits and keeping in view the needs for

faster economic development and growth. Our Patent Laws

ensure working of inventions and processes within a

reasonable time of 3 years.

3

B.

C

HI.

Our Patent System excludes certain categories of industrial

and other products vital for our economy :

(i)

Drugs & Medicines, Pesticides and Chemical Substances

(only processes are patentable)

(ii)

Atomic energy inventions ; and

(iii)

Agriculture & Horticulture Products.

Provisions of the Act have been designed in a balanced

manner to achieve the objective of working of the patents

by the Patentee or through Licencees (under Compulsory

Licensing or Licensing of. Right provisions).

INDIAN PATENT SYSTEM - COMPARABLE

Certain provisions, which are being objected to by foreign interests,

are not unique in our laws. Such provisions exist in the laws of

Switzerland, Japan, USSR, Spain and several other countries. An

analysis is given in the attached Statement.

„

ft

IV.

CONSEQUENCES IF THE INDIAN PATENT SYSTEM IS CHANGED

If process patent wherever applicable is

changed to product

patent; Compulsory Licensing becomes weak and unenforceable ;

Term of all the Patents get extended to 20 years, Reversal of

burden of proof is conceded etc.,

the consequences will be disastrous to Indian economy

in terms of :

(i)

our current research activity, due to our stage of

development and size of our businesses is mainly

directed to applied/process research. Such research

work will stop completely for new products and would

be applicable only for patent - expired old products

(after a lapse of 20 years).

'

(ii)

No new product would be introduced by Indian Companies

as is happening at present. Licensing of patented products

would be a pre - requisite which would be extremely diffi

cult, if not impossible.

(iii)

Dependence on imports (of not only raw materials but

also of finished products) would increase to a dispro portionately high level and' at exorbitant prices.

(iv)

Export activity would receive a major set-back, subs

tantially worsening the balance of payment position further

....4/

(v)

Monopolistic regimes will get established and competitive

forces would get totally eliminated. Products would be

available at unimaginably high prices.

INDIA'S ECONOMY WILL BE VULNERABLE TO THE DESIGNS OF

TECHNOLOGICALLY ADVANCED NATIONS.

B.K. KEAYLA

Convenor,

National Working Group

On Patent Laws.

ANALYSIS-PROVISIONS OF INDIAN PATENTS ACT 1970 ARE NOT EXCEPTIONAL

ASPECT

I.

11.

PRODUCTS EXCLUDED

FROM PATENTABILITY

PROCESS PATENT

PATENTS ACT OF OTHER COUNTRIES

INDIAN PATENTS ACT, 1970

- Food (Article of nourishment)

Food Products

Australia, China, Canada, Brazil, Japan,

Spain, Switzerland, Korea, GDR, Hungary,

Poland, USSR & many other countries.

- Medicine or drug

Pharmaceutical

products

Australia, Canada, China, Japan, Spain,

Switzerland, GDR, Hungary, Poland,

Turkey, Argentina, USSR, Brazil,

Pakistan & many other countries.

- Substances produced by

chemical processes

Chemical

Products

USSR, Brazil, Chile, China, Hungary,

Korea, Mexico, GDR, Spain.

- Method of Agriculture or

Horticulture.

- Process for Prophylactic or

treatment of human beings or

animals or plants.

- Products for protection of

preservation of plants.

Plant varities or

Austria, China, Canada, Brazil, Denmark,

kinds of animals

Finland, France, Sweden, Norway, UK,

or essential

Poland, Switzerland, USSR & many other

processes for obtaincountries.

ing plants or animals.

- Atomic Energy Inventions

Nuclear Materials,

Atomic Energy,

Atomic Weapons.

Japan, USA, China, Czechoslovakia,

GDR, Poland, Brazil, Romania.

- Substances used as food or

as medicine or drug (include

Insecticide, Weedicides etc.,

intermediates for producing

medicines, insecticides etc.)

Medicinal & Food

Products.

Bulgaria, Colombia, GDR, Hungary,

Turkey, Romania, Spain, Taiwan,

Uruguay, Venezuela, Australia, Mexico,

USSR & Canada.

- Substances produced by

Chemical processes.

Chemical Processes dr methods.

Germany, Austria, Brazil, Czechoslovakia

Hungary, Poland, Japan, Mexico,

Norway, USSR and Holand

III.

ASPECT

INDIAN PATENT ACT 1970

TERM OF THE

PATENT

For Food, Drugs and

Medicines & Chemical

Substances:

7 years from the

date of application

or 5 years from the

date of sealing of

patent.

For other patentable

products

19 years

OTHER COUNTRIES

5 years : For certain products/processes

Turkey, Argentina, Chile, China

Iran and Venezeula.

6 to 10 years : Turkey, Argentina, Chile, China,

Columbia, Egypt, Iran, Peru, Venezeula,

Yugoslavia, Cuba.

11 to 15 years: Italy, Japan, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia,

Romania, USSR, Greece, Portugal, Spair

Turkey, Argentina, Brazil, China, Egypt,

Iran, Iraq, Korea, Mexico, Sri Lanka,

Uruguay, Malaysia, Thailand.

16 to 20 years : Spain, Israel, Austria, Canada, GDR,

France, Switzerland, U.K., U.S.A.,

FGR, Hungary, Philippines, Bangladesh

Pakistan, Singapore and certain other

countries.

IV.

Compulsory

Licensing

Compulsory licences granted after 3 years

if reasonable requirement of public interest

not satisfied about availability, reasonable

prices.

i) Similar provisions exit in Model Law prepared by

BIRPI predecessor of WIPO.

ii)

Even WIPO Document No.WIPO/IPL/BN/85/4 dt.

December 3, 1985 permit similar objectives.

3

ASPECT

OTHER COUNTRIES

INDIAN PATENT ACT, 1970

iii)

In Public interest, Government

may apply after 3 years, for suo moto

endorsement.

Other countries having similar provisions are:

England, Germany, France, Greece, Israel,

Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Ireland,

Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Newzealand,

Finland, Guatemala, Netherland, Pakistan,

Philippines, Sweden, USSR, Yugoslavia.

China, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Republic of

Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Australia, Canada,

USA, U.K., France.

V.

LICENSING OF

RIGHT

VI.

Deemed to have been endorsed after

LICENCE OF RIGHT

3 years due to non-working.

FOR MEDICINES,

DRUGS OR CHEMICAL

SUBSTANCES

VII.

REVOCATION

If first compulsory licence is not

worked in 2 years, order for revocation

issued within 1 year thereafter.

Australia, Austria, Brazil, Cyprus, Egypt, GDR,

Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Newzealand.

VIII.

REVERSAL OF

BURDEN OF PROOF

No provision

No Provision (i) Switzerland, Brazil, Czechoslovakia,

USSR. Sweden.

France (Minister's Orders), Newzealand, Cyprus.

(ii)

Under European Patent Convention.

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.4

INDIAN PATENTS SYSTEM IS AN IMPORTANT

SUBJECT BEING RAISED AT DIFFERENT FORUM.

GOVERNMENT IS UNDER TREMENDOUS PRESSURE

FROM FOREIGN INTERESTS FOR MAKING

SUBSTANTIVE CHANGES.

IT WILL NOT BE IN OUR

NATIONAL INTEREST TO CHANGE ANY PROVISION

OF OUR PATENTS ACT 1970.

THE ATTACHED PRESS CUTTINGS ARE FOR

YOUR SPECIAL ATTENTION PLEASE.

CONVENOR

THE TRIBUNE, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1988

Strangulating Indian R&D

UBLIC affirmation by the Prime Minister

that the import substitution effort in tech

nology has been •'one of the biggest mistakes” is

ominous. Coming in the midst of mounting

pressure and open arm twisting by the de

veloped countries, in particular the USA, via

the Uruguay' round of GATT negotiations in

which, together with trade in services, protec

tion of intellectual property has been inscribed

as the most pressing issue on the agenda, the

Prime Minister's stand, if not checked and

reversed, portends evil times of a grave nature

and serious dimensions for Indian research and

development (R&D) and tcchnologicaPprogress

Mr Rajiv Gandhi chose to deliver his dictum

on the technology policy and its aims in his

characteristically hectoring style on the occa

sion, ironically enough, of presenting the 1987

Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar awards to Indian

scientists. It is a pity that the Indian scientists

present on the occasion did not have an oppor

tunity to refute his extremely dangerous posi

tion on Indian technology and its tasks at the

present stage of India’s socio - economic de

velopment

But India's scientific community is greatly

disturbed at what are tending to be concerted

moves of comprador business and political

interests in India, foreign multinationals and

the governments of the developed countries to

derail Indian R&D and strangulate the effort

for achieving technological self-reliance to

break neo-colonial shackles on the country’s

socio-economic development process.

The Prime Minister's stand on the technology

policy and the reasoning behind it are strikingly

supportive of the mobilisation of forces by

multinational corporations for incorporating a

provision for the protection of intellectual

property rights under the GATT Charter. This

will be a powerful instrument for enforcing

what is called the Paris Convention on the

protection of patents, designs and trade marks

to cover not only industrial property; as origi

nally conceived, but all intellectual property on

a much broader basis.

Many developing countries, including India,

have refused so far to be a party to the Paris

Convention. This is for the very good reason

that under the Paris Convention indigenous

R&D would have little scope to develop, above

all by way of the import substitution route, and

help indigenous enterprise to engage in the

production of goods and services to satisfy the

domestic demand and even find export outlets.

India, after a great deal of tussle with multi

national corporations, which own 85 per cent of

the patents registered in the world, enacted in

1970 its own patent law. The essence of this law

is that it provides a solid and viable basis for the

Indian R&D to develop technologies for substi

tuting the import of patented products and

prevent their unhindered access to the Indian

market. It challenged the monopoly of foreign

business interests to import the patented pro-

P

by Balraj Mehta

ducts and gave a boost to the Indian R&D and

indigenous business enterprises to undertake

domestic production of similar products.

What the Indian patent law of 1970 actually

provides for are simple departures from the

patent system which the multinational corpora

tions and the developed countries want to

sanctify and enforce. It permits not only pro

duct patents which alone are allowed under the

Paris Convention but also process patents for

food, medicines, drugs and chemical subst

ances. Agricultural products and processes for

the treatment of human beings or animals are

not treated as inventions and are, therefore, not

patentable. Atomic energy inventions are also

not patentable under the Indian law.

As regards the period for patent protection,

the Indian Ihw provides fiVe to seven years for

food, medicine, drugs and chemical substances

and 14 years for other products. The law,

therefore, gives reasonable protection to those

who invest brains and money to invent new

products and processes. The charge of the

multinationals that it encourages imitators and

the production of counterfeit goods is totally

misplaced.

The real point about the working of the

Indian patent law is that it has helped to find

substitutes for imported goods and services by

R&D in India which has rightly concentrated its

efforts not on finding brand new products but

on finding new processes for undertaking

domestic production to substitute import of

goods and services produced abroad. This is due

to the compelling fact that discovery of brand

new products requires huge resources in skills

and money which a developing country lacks. In

the first stage of development, a developing

country must concentrate available resources to

achieve optimal results which come by way of

import substitution rather than new products.

By adopting the import substitution route,

Indian R&D has derived rich returns not only in

terms of foreign exchange savings but also by

ensuring for Indian consumers assured supplies

and reasonable prices. It has slashed the high

monopoly profits foreign goods could earliet

extract from the Indian market. This has been

most palpable in the case of pharmaceuticals

and food products. This also explains the fran

tic lobbying of international drug firms to drag

India into the Paris Convention on patents and

recover a profitable market for their products in

India.

Before the 1970 Patent Act of India came into

force, finished drugs and exotic processed foods

were protected for free entry and the consumer

was mulcted by their producers abroad in the

absence of any competition from domestic pro

ducers. This could go on under Paris Conven

tion for as long as 20 .years for each product.

After 1970, however, Indian R&D (having

developed cost - effective processes) has helped

the manufacture of a large number and range of

basic chemicals, drugs -and pesticides in India

These products arc being sold to the Indian

consumer at reasonable prices and even export

outlets on a competitive basis - quality wise

and price wise - are being found for them.

What the multinational corporations arc cla

mouring for is what they call "effective deter

rent to international trade in goods where there

is an infringement of intellectual property

rights". They are even demanding that for

patent protected products, the production of an

identical product should be prohibited. To this

end, they arc demanding that GATT should

ensure that national laws and procedures on

protection of intellectual property are in con

formity with the standard provisions of the

Paris Convention. If any country fails to fall in

line, the signatories to the intellectual property

right provision of GzXTT should lake concerted

action against it, including trade discrimination

and curbs on financial aid and technology

transfers.

What is being demanded, in (act, is that the

developing countries, among them India, should

join the Paris Convention and the GATT should

put in place sanctions to achieve that end.

It is rather disconcerting in this context that

with the policy of import liberalisation already

hitting hard the domestic production of a

variety of goods and services, above all the

strategic capital goods and machine - making

industries, and the opening of the Indian mar

ket for investment and marketing activities of

foreign capital generally and multinational cor

porations in particular, the Government has

initiated moves to review and revise the time tested official policy and position on the Paris

Convention on patents also. A committee, in

fact, has been already at work since early last

year for this purpose

Meanwhile, there arc disturbing indications

that the Government has been pushed to the

very brink of deciding in favour of joining the

Paris Convention on patents within the

framework of the GATT provision on the pro

tection of intellectual property It appears, as it

often happens in the management of public

affairs under the present political - power

dispensation, that only a nod from the Prime

Minister is awaited (or clinching the issue

The Prime Minister’s tirade against the tech

nology that is geared (or import substitution

may well be an advance notice that he has been

persuaded by the interested quarters and is now

ready to order a fall into the gilded trap of the

Paris Convention on patents and the GAT1

provision for protection of intellectual property

to strangulate the R&D effort and technology

self - reliance of India. The deadline for it is said

to be mid - December. The scientists and

technologists concerned'have to bestir them

selves immediately and raise strong and united

voice of protest to block this disastrous move

HINDUSTAN TIMES - 28.1O.S8

Patents law

Pressure by US

By R. Nair

NDIA'S scientific establishment tending the Sri for another threeas well as senior policy makers are year period from this year, pressure

apprehensive that Government on India began mounting US Trade

leaders may cave in to intense press Representative Michael Smith met

ure from the United States to Commerce Secretary A. N. Verma

change India's patents and licensing on July 30 and bluntly demanded

laws. Should India succumb to the that India introduce product patents

pressure, they warn, the long-term in certain areas. According to mi

effects to the nation could be far nutes of the meeting, Mr Smith

worse than signing the NPT because made it unambiguous that unless the

of its potential to affect every facet ‘product vs process' issue was re

solved to the satisfaction of the US,

of the economy.

The proposal has met with strong there would be quick retaliatory ac

opposition from the Law, Industry tion on the trade front. That was

and Science Ministries with Minister followed by a ‘Dear Rajiv’ letter

of State for Science and Technology from Mr Reagan himself that

K. R Narayanan reportedly addres warned that ihe twice-postponed

sing a letter to the Prime Minister visit of his Science Adviser, Dr Wildetailing the various ramifications Ham Graham would not go through,

of succumbing to the US pressure. apart from hinting at other sanc

Informed sources say he has warned tions. The letter caused some

that self-reliance and indigenous de- amount of flutter in the PM’s Office

vclopment.of science would be a cer and brought the External Affairs

tain casualty, the effects to be im Ministry into the picture. A ‘Dear

mediately felt in the pharmaceutical Ron’ letter was despatched which

industry. Mr Narayanan’s letter was seemed to be sympathetic to US

preceded by a four-page memoran concerns without making concrete

dum to Cabinet Secretary B G. De- promises. Although senior officers

shmukh from Industries Secretary' in Industry and Science ministries

Otima Bordia on similar lines. The blame the External Affairs men for

latest US proposals under the Scien diluting the Indian position, their

ce and Technology Initiative, she is role was apparently limited to seeing'

reported to have warned, is only the Graham visit came through.

another extension of the policy to Shortly before Dr Graham arrived

use cooperation in the field of STI to in Delhi, the US Embassy in Delhi

change our patent laws. If the US handed over a list of "talking

demands are to be accommodated, points" that even seemed to hint

it would call for a mandate to amend that India could hold out its assur

patent laws on a 'substantive and ances quietly. The issue need not

figure in the main communique but

fundamental scale.’

Essentially, the problem revolves could be addressed in side letters,

around process patents and product the Embassy suggested.

patents. Indian patent laws permit

Confusion among the Indian

only process patents for food, medi negotiating team caused by pressure

cine, drugs and chemicals. Limited from the PM’s office to evolve a via

product patents are available for media to accommodate the US con

seven and fourteen years duration cerns, has apparently led to India

for various categories while atomic conceding more than it intended to,

energy and living organisms cannot give away in the first place. A joint

be patented at all.

statement issued by the two sides on

US pressure on India to align its Oct. 5 says “India and the US agree

patent laws with its own began to consider the question of providing

shortly after Prime Minister Rajiv for protection and allocatidn on a

Gandhi and President Reagan mutually agreeable basis of any In

signed an agreement during Mr tellectual Property Rights arising

Gandhi’s 1985 visit to Washington out of the STI programme.

to extend for another three years the

Analysts point out that one

STI signed in 1982 by Mrs Indira

Gandhi with the US President. The reason why the US is so concerned

Committee of Secretaries met on 22 about enforcing industrial property

July 1986 and expressed itself for rights now more than ever is because

continuing with the present legisla of fears that its own exports to tradi

tion, pointing out that it might ham tional markets may be squeezed in

per the indigenous development of the future, for instance, as the Euro

technology if the patent laws were to pean Community attempts to liber

be changed. The view was repeated alise internal trade barriers and cre

when the Committee met again a ate a’ single market. On a similar

few months ago. The PM’s Science tact, the Omnibus Trade Bill passed

Advisory Council headed by Dr C. by the US Congress earlier this year

N. R. Rao met in June last year to is oriented towards pushing exports

discuss the issue and concluded that and gives the US greater leverage in

at no time had the Department of bilateral negotiations with countries

Science and Technology com such as India and China, although

plained that our patenting laws were officials claim that the US would still

inhibiting access to high technology. like to work within the overall

Consequently, "‘nothing should be framework of GATT. If India now

done to undermine the supremacy buckles down to the arm-twisting,

analysts believe, the loss would be of

of the Patents Act."

When, discussions began on ex the entire developing world.

I

ECONOMIC TIMES - 2ND NOVEMBER,

1988.

Continued US pressure on India

Patents law may be amended

By Oar Special Correspondent

NEW DELHI. Nov. 1.

Patents law may be an arcane subject

for most people, but Indo-US

diplomacy nearly reached a flashpoint

in the last two months on the subject

of patents.

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and

President Ronald Reagan have ex

changed persona] letters on the sub

ject; the Indo-US Science and Tech

nology Initiative (STI) nearly got

called off in September, as a result of

the disagreement; and the US even

came close to the unprecedented step

of threatening trade sanctions against

India.

So far the government of India has

refused to buckle under pressure. But

some changes in India's patents law, to

overcome any specific legal dcficiencies that arc pointed out, are not ruled

Out.

The US offensive is part of its global

initiative on the subject of intellectual

property rights. In the Indian context,

it has mounted an attack on three

fronts:

★In the course of negotiating the

extension of the Science and Tech pressure was during the negotiations

nology Initiative (STI), first launched for extending STI for a fresh Lhree-year

when Mrs. Gandhi visited the US in term. Dr. William Graham, science

1982 and then renew’bd for three years adviser to President Reagan and the

US negotiator on the STI renewal.

in 1985;

★At the Uruguay Round nego postponed his visit to India thrice in

tiations of the General Agreement on what were seen as pressure tactics.

Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which are And in July, at a meeting between a

US trade representative and com

due for review soon at Montreal;

★And through pressure to sign the merce secretary A. N. ’Verma, the

controversial Paris Convention on prospect of trade sanctions was held

patents, which is overseen by the out indirectly, through a reference to

World Intellectual Property Organisa such action against Brazil (which has

no patents law).

tion (WIPO).

Indo-US discussion on the over-all When this loo failed to yield results.

subject of intellectual property rights President Reagan wrote a “Dear

dates back to Mr. Rajiv Gandhi’s visit Rajiv’’ letter which seemed to suggest

to the US in 1985. At that time the US that unless the US stand on patents

administration underlined its concern was accommodated, the STI was

about the fact that under Indian doomed. The letter also talked about

patents law, only processes were cov tl]e benefits of the hi-tech that the US

ered in key areas like pharmaceuticals w-as willing to offer.

and chemicals, and not products. Rajiv’s ’’Dear Ron” response was

Among other issues that have figured instant, and reflected the unanimous

in discussions on India’s patents law is view that had developed on the sub

the period for which patent protection ject within the Indian government.

is available.

As far back as July 1986. the commit

Till last month, the most active tee of secretaries had concluded afler

due deliberations that signing the Pans

Convention might jeopardise the in

digenous development of technology.

Last year, the Science Advisory- Coun-^

cil to the Pnmcx Minister in turn

concluded that nothing ought to be

done to undermine the supremacy of

the Indian patents law, and pointed

out that al no time had the department

of science and technology (DST) held

that the Indian stand on this issue had

prevented access to high technology

from abroad

At the height of the STI imbroglio,

the law ministry declared that patent

protection could not be a matter of

discussion between two sovereign na

tions. And the DST held that there was

no need for any significant changes in

the existing law.

The industry ministry (which is the

nodal ’ministry for patents) put its

view down in a detailed note which

talked of the conceptual and

philosophical differences between the

Indian and US patent laws.

The committee of secretaries met

Continued on page 4, col. 7

Indian olficials argue that they have

scored a clear victory on the STI issue.

Continued from page 1. col. 4

and that the intense US pressure w-as

successfully fought off. But they also.

again and reiterated its earlier stand.

recognise that the US is not about to

as did Mr K. R. Narayanan, minister

forget the issue, and that pressure will

of state for science and technology.

who pointed out that any change in be mounted afresh in other forums.

US diplomats in turn say that they see

India's position would damage the

domestic technological development the task of changing India’s stand on

the issue as a long-term process.

of the pharmaceutical industry.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry

The issue has already been joined in

has been in the forefront of the fight GATT, where India has argued that

to keep the Indian patent law un property rights cannot be discussed as

changed, even as the US drug industry it is not a trade-related issue. India and

mounts pressure on the US txl- Brazil have been leading the fight on

this issue in GATT, with a third ally

ministration.

At one stage the US government now being Thailand This could be

tried to ease its way through the STI come another major issue for the

dispute by suggesting that rather than developing countries, along the lines

lake a public stand on the subject, that the issue of trade in services

India could deal with it outside the became On that issue too. it was India

main communique on the STI re and Brazil which fought a determined

US offensive before a compromise was

newal.

But India refused to budge on its eventually worked out.

basic stand. And early last month. STI

Before STI and GATT, the main

was finally renewed Nevertheless, the pressure on India had been for signing

joint communique issued after STI the Pans Convention. Now this has

was renewed for a further three years become a relative sideshow, with the

stated in ambiguous terms: "India and US de-emphasising the issue in favour

the United States agree to consider the of pressing the issue on GATT. quality of providing for protection and

Nevertheless, a seminar is due to

allocation on a mutually agreeable take place later this montji in New

basis on any intellectual property Delhi, organised jointly by WIPO and

the Federation of Indian Chambers of

rights ansing out of the STI.”

Commerce and Industry (FICCI). A

counter-seminar wil be held around

the same time by the newly formed

National Working Group on Patent

Laws.

Patents law

IHPIAM

SATURDAY,

express

OCTOBER

22,

1988.

Patents: India under pressure from US

By R. SASANKAN

cine, drugs and chemicals.. This en- the first list would be ready by May Patents Act. some large industrial

Express News Service

ables the Indian companies io pro- 19§9

houses which have foreign cnllah.ujNEW DELHI, Oct 21 ducc any item in the international

The India scientific community, by tions feel that the Act could be

The Government is split over the market by modifying the process

and large, remains committed to the amended. These arc mostly mcmh i

question of amending the controver- The US Administration is asking for present Patents Act and feels that it of F1CCI.

sial Patents Act on the lines sug- introduction of product patents in all should not be amended It claims the

Industries in the pharm^ccatical

gested by the US Administration

fields to prevent what it calls “mter- support of Mr Sam Pitroda. the and chemical sectors arc panicks

A committee of secretaries in the national thievery ' The US also Prime Minister's technology adviser. They, along with a number ,>t other

hird week of /Xugust this year, de- wants a 20-year duration for the (Mr Pitroda could not be contacted organisations have formed .< ttafior.il

■ided against amending the Act But patents

as he was out of Delhi).

working group on patent laws under

low some of the senior officials oi

us Administration is putting

The Science Advisory Council to the chairmanship of Dr Nityan.ind.

he ministries concerned have tremendous pressure on the Govcrn- the Prime Minister, headed by Prof former director. Central Drug' Re-hanged their views. Even within the ment to amend the Patents Act to C N.R. Rao. director 'Indian Insti- search Institute The working group

iame ministry officials hold different protect its intellectual property tute of Science, has told the Govern- plans a national campaign to make

rights US embassy sources when ment that "nothing should be done to people aware of damages that could

. .ic Ministry of Industry ha< all contacted, told ENS that the Indian undermine the supremacy of the In- be caused if the Government decides

along been opposing any amendment Government had not yet agreed to dian Patents Act’ On the question to amend the Act on the lines vugto the Patents Act. In fact, it send in amend the Act, but it “seems to of India joining the Paris Convention gested by the US Government

its views in writing to the cabinet agree that this is a senous problem “ on intellectual property rights, the

secretary a lew months ago. But a They said there could be trade sane- council said. There is no need at the

Th® scientific community feels that

very senior official of the ministry tions if India is identified as one of present juncture to join it before

’n<^ian Government has already

now feels that "something should be those countries which provide the certain detailed studies arc com- g‘ven >n to the US demand bv making

^e issue a bilateral one. The joint

done ’ to meet the US demand least protection to US intellectual plcted"

Similar thoughts have emerged in property rights. Asked whether India

The Indian industry is also split statement issued by the two countries

other- ministries as well.

had already been identified as one over the issue. While industries in the on October 5 after extending the

Hie Indian Patent Act permits such country, the sources said the pharmaceutical, chemical and food Gandhi-Reagan, Science and lech

only process patents for food, medi- process of identification was on and sectors oppose any amendment to the

Continued on Page 9 Column 2 •_

Patents: India under pressure

Continued from Page 1 Column 8

nology Initiative says that "India and

the United States agree to consider

the question of providing for protec

tion and allocation on a mutually

agreeable basis of any intellectual

property rights arising out of the STI

programme".

A US delegation is expected here

in November-December to discuss

the question of intellectual property

rights in areas falling within the STI

programme The outcome of the

discussions can have broader implica

tions

An executive order issued by the

US President in April last year says

that the US Government should have

international science and technology

agreements only with those countries

which have policies to protect the US

intellectual property rights.

The United States is not keen on

India joining the Paris Convention on

intellectual property It wants the

Indian Patents Aft tn be amended on

certain lines to protect its intellectual

property rights

not licence their patented products to

The Indian patent system excludes them. Large-scale litigation will be

certain vital products such as agri initiated by foreign patent-holders

cultural products. But the US wants against the process developed by the

agricultural products to be included national companies Drug prices

in the patent system. The present Act would go up and drug exports, curallows the Government to force pro tently around Rs 300 crores and

duction of a patent failing which it growing at the rate of 40 per cent per

can give the patent to other com annum, will be adversely affected as

panies. The US wants this provision exports to countries who are mem

bers of the Paris Convention will be

to be scrapped

Those who oppose anv change in stalled, they contend

The Omnibus Trade and Competi

the Patents Act Tee) that faster indus

trialisation had been possible due to tiveness Act 1988. passed by the US

the pragmatic provisions of the Act. Government, requires the US trade

In particular, it has helped the coun representatives to identify countries

try to produce chemical-based pro that deny protection lor US patents

ducts, pharmaceuticals, and agro and copyrights It is now clear that

chemicals at comparatively cheaper the US administration is holding out

the threat of trade sanctions to force

prices.

Their contention is that the process India to amend the Patents Act.

US officials are on record as saying

of industrialisation will be hampered

if India amends the Patent Act or that the Indian Patents Act does not

joins -the Paris Convention The protect the US intellectual property

growth of the national sector of the rights. They forced Brazil to do it by

industry will be set back by 10-15 cutting down imports of coffee from

years as foreign patent holders will that country.

INDIAN EXPRESS: !'•' few DELHI, Monday, July 25, 1988

India and Paris Convention

Govt may succumb to pressure

but he was not aware of any decision. anyone can apply to the controller.

He declined to give his views on the alleging that the reasonable require

subject saying he would reserve them ment of public interest had not been

satisfied and that the product was not

NEW DELHI. July 24 for the Government.

available at reasonable price The

The Indian Government is under

The Paris Convention on Industrial controller, if satisfied, can order the

renewed pressure from industrialised

countries and the World Intellectual Property 1883 provides for effective patentee to grant a licence The

Property Organisation (WIPO), a protection to patented products. The controller can'also revoke the patent

UN affiliate, to join the Paris Con Indian Patent Act. 1970, protects on the ground of public interest if the

only process patent, and not product patent is not worked within two years

vention on patent law.

There is a fear among Indian in patent in pharmaceutical and chemic of endorsement of compulsory li

dustry and the scientific community al industries. This enables Indian cence.

that the Rajiv Gandhi Government. companies to manufacture any pro

in its anxiety to obtain the latest duct by developing their own proces

Once a country joins the Pans

technology, may agree to join the ses. For instance, Glaxo, a leading Convention, it will not be able come

Paris Convention. The industrialised pharmaceutical company, introduced out of it before six years. Of the 97

countries, particularly the United into Indian market Ranitidine, an members, only 77 members had

States, have been insisting that trans anti-ulcer product about three years signed the latest convention, that is

fer of sophisticated technology to ago. This is now being manufactured the Stockholm Convention of 1967.

India will not be possible unless India by a number of Indian companies Of the remaining 20 members, nine

have signed the Lisbon Convention.

honours the rules regarding intellec through their own processes.

The Paris Convention has 97 mem 1958, nine the London Convention of

tual property rights.

The Scientific Advisory Council to bers. According to Indian industry. 1934 and two the Heague Convention

the Prime Minister is understood to the most retrograde provision in the of 1925. There are as many as 62

be the latest body to oppose the Convention is the Right of Priority. members who belong to developing

proposal to join the Paris Conven This article provides that if a com countries most .of whom had no

tion. Officially, there is no indication pany registers a patent on a particular industrial base when they joined the

as yet that the Government has re day. that date will be the priority date Pans Convention

According to the latest estimate, as,

lented in its opposition to the Paris for all member countries. Put dif

Convention. However, there is a ferently. any subsequent registration many as 37 countries are without any

feeling among Indian scientists that can be invalidated through the Right industrial base. Furthermore, there

Mr Sam Pilroda. Prime Minister's of Priority by the original patentee. arc 22 members who are signatories

technology adviser v/ho had himself This will enable the patentee to enjoy to the Convention but their domestic

laws provide that drugs and phar

patented a few electronics products a monopoly in the market.

The Indian Patent Act. it is maceutical products arc non-patent

m the US. may be able to influence

the Government when the issue com claimed, strikes a balance between able. If India joins the convention it

es up for discussion in coming the interests of the inventor and will have to extend these rights to all

months.

those of the consumer to ensure that members without the matching recip

Mr Pitroda, contacted by this cor the benefits of new technological rocity.

The Indian subsidiaries of trans

respondent, said he had not yet been development reach the consumer as

consulted on the issue. He said there fast as possible. It also provides for national corporations, particularly

were some discussions at the Govern compulsory licensing. Three years the drug companies, have bten

ment level about three months ago from the date of sealing of a patent. pleading that India should join the

fir R. SASANlCVs

Express News Service

Paris Convention.. But the Indian

drug sector has been vehemently

opposing it. Ils argument is that the

process patent has already helped the

national drug and pharmaceutical

sector to develop technologies of a

large number of basic drugs and

produce them on commercial scale

and at competitive prices. In fact.

many Indian companies export a

number of bulk drugs to developing

and developed countries. Some of

these products have been patented

cslcwhcrc by multinational -com

panies who are members of the Paris

Convention.

Il is pointed out that if India

decides to join the Pans Convention

it will have to modify its present

Patent Act. According to the Paris

Convention, the protection of intel

lectual property and rights of the

patentees have supremacy over the

interests of any country or its people.

Legal opinion in India too has been

opposed to India joining the Covention

The country's leading scientists

have also warned the Government

that joiniog the Paris Convention

would cripple research and develop

ment not only in drug industry but

also in bio-technology

The Government is expected to

take-up the issue after the forthcom

ing scm'oar on Patent Law and Paris

'Convcnton jointly being sponsored

by F1CCI. the International Cham

ber of Commerce and WIPO. It is

scheduled to be held in Delhi in

November.

NATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON PATENT LAWS

OBJECTIVES

To discuss issues relavant and related to the Patent Laws

and Paris Convention ;

To arrange for research and publication of papers relating

to these issues ;

To help create a better understanding of these issues by

organising meetings, seminars and public debates ;

To represent to the Government and those concerned with

the formulation of policy on agreed views of the Group ;

Publicise and organise publicity ;

in respect of India's and international patent and related laws

and policies.

To forge a National Alliance of various Organisations/Forum/

Associations, etc.to work towards and campaign for patent

laws and policy best suited for India's interests.

Position: 869 (9 views)