1564.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

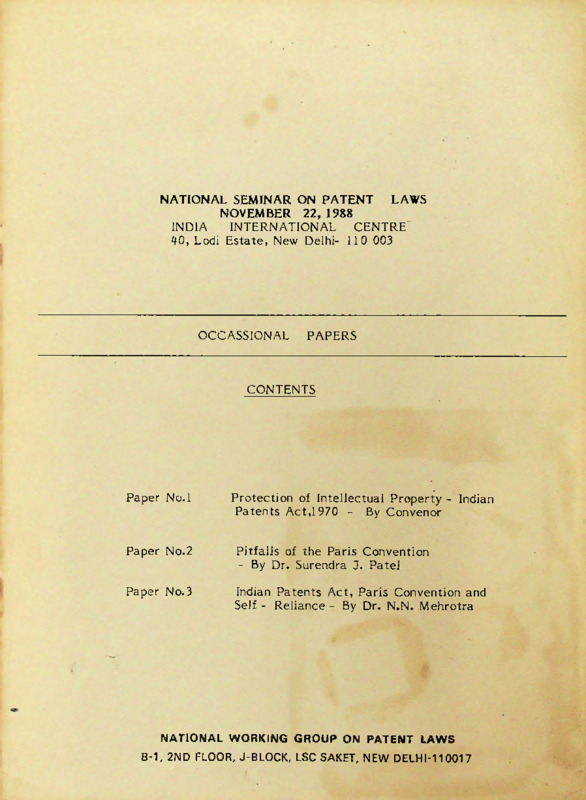

NATIONAL SEMINAR ON PATENT LAWS

NOVEMBER 22, 1988

INDIA

INTERNATIONAL CENTRE'

40, Lodi Estate, New Delhi- 110 003

OCCASSIONAL

PAPERS

CONTENTS

Paper No.l

Protection of Intellectual Property - Indian

Patents Act,1970 - By Convenor

Paper No.2

Pitfalls of the Paris Convention

- By Dr. Surendra J. Patel

Paper No.3

Indian Patents Act, Paris Convention and

Self - Reliance - By Dr. N.N. Mehrotra

NATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON PATENT LAWS

B-1, 2ND FLOOR, J-BLOCK, LSC SAKET, NEW DELHI-110017

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO - 1

PROTECTION OF.INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

- INDIAN PATENTS ACT, 197Q

COMMUNITY HFA'tm CELL

BACKGROUND

-------------------- 47.71 St .Mark's -R-

The iridian Patent

>ct, 1911 was influenced mainly by tbe

British interests who were ruling this country till 1947, This

Act was so retrograde that it allowed a virtual monopoly of the

Indian markets by fechnologically advanced countries through the

Patent System.

To keep India as their captive marlet,

the

British rulers also did not make India a member of the Paris

Conven tion.

After independence,

the importance of modifying the Patents Act

1911 was amply realised by the leaders of the country.

An

expert committee headed by Justice Bakshi Tek Chand was appointed

to examine in depth the issues relevant for rapid industriali

sation of the country by modifying tbe old Patents Act.

Later

another Committee headed by Justice Rajagopala Iyengar was apnointed to examine the new patents Bill and to recommend appropriate

provisions relevant to the national interest. .Both the Commi

ttees found enough evidence of misuse of natent protection by

various foreign companies,

including the Multinational Companies,

to ensure protected markets for themselves.

More than

patents in India were registered by them and only a few patents'

were worked in the country.

from abroad.

Most of the goods were imported

It was thus evident to these Committees that our

National law was a big constraint in the industrialisation of the

country.

Not only this,

the law even denied the country to obtain

goods for its essential requirements at cheeper prices available

from alternative sources in the international markets.

This

happened because of the patent protection granted to the foreign

patent holders included right of importation also for them.

A National Conference of scientists also provided a strong basis

for changes in the Patent Laws.

Later the Patent Bill was exten

sively debated by the Parliamentary Joint.Select Committee which

even invited experts from all over the world to give evidence and

opinion based on their experience elsewhere.

Both the Houses

of Parliament also had in-depth debates on this major economic

statute.

Thus,

a thorough national debate took place before

the enactment of the new patents Act of l°70.

INDIAN PATENTS ACT, 1970

The Indian Patents Act, lq7o was hailed by many countries and

UNCTAD as one of the most progressive Statutes.

The basic nhilo-

sophy of this Act is to strike a balance between the interests of

the inventor and those of the consumer .to ensure that the bene

fits of new technological development reach t^e consumer as fast

as possible.

Appropriate technologies have been developed and

assimilated for indigenisation of production.

A Monopolistic

regime which comes through the patent system is therefore non

existent in India.

The Patents are granted to encourage invention

and to secure that the inventions are worked in India on commercial

scale and to the fullest extent without undue delay.

BASIC PHILOSOPHY

Section 83 of the Patents Act,197o enunciates the basic principles

governing the Act in the following terms :(a)

"that patents are granted to encourage inventions and to

secure that the inventions are worked in India on a

commercial scale and to the fullest extent that is rea

sonably practical without undue delay ; and

(b)

that they are not granted merely to enable Patents to

enjoy a monopoly for the importation of the patented

article."

The Patents Act, 197o during the last 16 years of its oneration

has served the aspirations of the framers.

behind the Act is still' valid.

industrialisation.

In- fact,

The basic rhilosoohy

The country has achieved ranid

near self-reliance in many indus

trial fields has been achieved basically due to the balanced

provisions of this unique Patents Act.

It has also been possible

to import the patented goods for meeting the country's needs from

competitive sources abroad.

(ZJ—IOO

I

COMMUNITY HEALTH CFLL

Wire

BAUGALOilfi - 5t>0

SALIENT FEATURES

There are many positive features of the Patents Act, 197n.

Section 84 provides for 'Comoulsory Licensing' on application

by other interested enterprise,

if the reasonable requirement

of public interest has not been satisfied and the product has

not become available in adequate quantities and at a reasonable

price in a period of three years.

Further Section 87 provides

for automatic endorsement of 'Licences of Right'

in the case

of methods or processes for manufacture of chemical substances,

food,

medicine or drug.

Again under Section 89 Government

can revoke the Patents if in its opinion a patent or the mode

in which it is exercised is mischievous to the State or gene

rally prejudicial to the public.

There are special provisions under Section 5 in the case

of inventions -

(i)

claiming substances intended for use, or capable

of being used, as food or as medicine or drug, or

(ii)

relating to substances ore^ared or oroduced by

chemical processes

no patent is granted in respect of claims for the substances

themselves,

but claims for the methods or processes of manu

facture are patentable.

As regards the Terms of tbe Patent,

it is 7 years from the

date of application or 5 years from the date of sealing

whichever is earlier for food,

medicines or drugs and

chemical substances.

Further, the registration for the

method or process of manufacture of such substances. In

respect of other inventions,

the period prescribed is 14 years

from the date of patent.

ADVANTAGES FROM INDIAN PATENT SYSTEM

Three important..advantages have accrued to the country

because of the progressive provisions of our Patents

Act, 19 70 s-

(i)

Government have been able to ensure starting

of commercial production of a Patented product/

process inIndia sooner i.e. in 3 years.

Earlier

the patent holders including MNCs used to file

'blocking patents' to maintain a market monopoly

for themselves by importing patented products in

India at exhorbitant prices from exclusive sources

abroad ;

(ii)

Indian Scientists and Technologists have been able

to develop processes suited to. the Indian conditions

and these processes are being -•'orked to achieve

self-reliance.

These processes are cost-effective.

(i 1 i )

It has beer, possible to serve the' consumer by impor

ting even patented products at competitive prices.

This is particularly true in the areas of food, drugs

and chemicals where only the process patents are

allowed.

FOREIGN COLLABORATIONS

It is generally pointed out that because of the inadequate

protection under the Indian Patents Act the registration of

new patents in India is on the decline.

in no way,

affected

This argument has,

the transfer of technology from the

industrially advanced countries.

The Patents Act 197o has

not stood in the way of entering of foreign collaborations

for those products for which technologies are not available

in India.

There has been tremendous' rise in the foreign

collaborations in recent years,

as is evident from the

following table

Year

No.of

Collaborations

1970

1981

183

3 89

1982

590

1983

673

1984

752

1985

1036

1986

957

1987

853

Due to liberal Industrial Policy enunciated during the last

four years,

it is expected that there will be further spurt

in foreign collaborations in the coming years.

The Increase

in foreign collaborations rather than the registration of

foreign patents shows dynamism in India's industrial growth

and capacity to improve self-reliance and absorb technologies

PARIS CON VEN TION - FURTHER THE INTEREST

OF DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

The Paris Convention was signed in March 1883.

there were 97 countries who were its member,

As on 1.1.198

out of which

there are 62 countries who belong to underdeveloped or deve

loping countries and when they became members of the Paris

Convention they orobabaly had no industrial base at all.

there are 3 7 countries which have absolutely r.^

*■

industrial base.

Further, there are 22 members who are

Even now,

signatories to the Paris Convention,

domestic laws,

table.

but accordinoly to their

drugs and pharmaceutical -reducts are un-naten-

These eight countries where chemical substances are

unpatentable.

There are many countries who have excluded

food products from patent System.

heterogenous Convention.

Thus,

Paris Convention is a

It is a club of unequals.

The needs

of a Patent System in industrialised countries is quite diffe

rent from that of the developing countries.

Whereas the deve

loped countries have traditionally been strong advocates of

the Patent System,

the developing countries have been stressing

that the system should help in

their development of indigenous

manufacturing facilities.

PARIS CONVENTION - SALIENT FEATURES

Some of the specific provisions of t^-e Paris Convention which

deserve special mention and which are not in tune with the

philosophy of

the Indian Patent Laws are

Rights of Priority

"Right to Patent despite restrictions or limitations

resulting from the domestic law."

Non-forefeiture of industrial designs despite failure

to work or Importation of orotected articles.

-

Convenient and weak excuses against 'Comnulsory Licensing!

-

No permission to import patented products from competi

tive sources.

-

Effective protection against unfair competition.

-

Amendment of domestic law to give effect to the provisions

of the Paris Convention ;

and

Binding for at least six years before any country can

leave the Convention after joining it once.

The above Articles in essence ensure that a Patentee can

continue to missuse his patent rights against any concern for

the rights of the States who grant these rights and privileges

to the patentee.

Thus, even if the patentee is not at all

interested in working his patent, it becomes extremely diffi

cult to enforce the need for working of the patent or import

o~f the product except from the monopoly patentee.

Thus,

"an overwhelming majority of patents granted to foreigners

through National Laws of develooing countries have been used

as import monopolies".

The above features of the Paris Convention are viewed as

retrograde steps for rapid industrialisation of a country like

India which is still in the developing stage.

The advantages

of joining the Paris Convention are hardly any for the deve

loping countries due to their technological limitations.

the contrary,

On

numerous disadvantages would accrue and hinder

industrial progress of the Patent System provided in the

Paris Convention

(See Table at the end comparing the provi

sions of Indian Patents Act 1970 and Paris Convention).

IMBORTANT VIEWS GENERALLY. QUOTED AGAINST

TOO MUCH PATENT PROTECTION

From time to time,

views have been expressed by important

dignitaries about the patent protection and paramount need

for

self-reliance :

The way in which a foreign patentee behaves,

has been brought

out by Sir William Holdsworth in the following words :

" The foreign patentee acts as a dog in the

manger, sends the patented articles to this

country (U.K) but does nothing to have the

patented articles manufactured here (U.K);

He commends the situation and so our indus

tries are under our own law starved in the

interest of the foreigners".

Sir Robert Reid expressed himself more emphatically when

he said

:

Nothing can be more absurd or more outraaeous

than that a foreign patentee can come here and

get a patent and use it, not for the purpose of

encouraging industries of this country but to

prevent our people doing otherwise what they

would do.

To allow our laws to be used to give

preference to foreign enterprise is to my mind

ridiculous".

Indian Drug Manufacturers Association,

a powerful body

representing the national sector of drugs and pharmaceuticals

also point out the above quotations as strong reasonings for

not joining the Paris Convention.

The process patent has

helped the national pharmaceutical sector to develop process

technologies of a large number of basic drugs and produce them

on commercial scale at competitive prices.

In fact,

the Drug

Industry is now poised to export a large number of bulk drugs

to many developing and developed countries at internationally

competitive prices.

USSR is one of the biggest buyers of

Indian Pharmaceutical products.

Given these circumstances,

the question arises as to why the Indian Patent Laws should

be changed and why India should

join the Paris Convention.

LEGAL OPINIONS ABOUT JOINING THE vARIS CONVENTION

There is formidable legal consensus amongst Four Former

Chief Ju stices zJus tices of Supreme Court who Pave c^me

out against joining the Paris Convention.

Justices Y.3. Chandrachud,

They are

M. Hidayatull ah, J.C.

Shah

and V. R. Krishna Iyer.

As is widely known

these four Justices have in the past

differed on several issues but they are unanimous that

joining the Convention will

require abrogation of several

important provisions of Indian Patents Law which will

seriously harm the economy of the country.

Justice Shah

has gone to such an extent and considers that in his opinion

joininci the Convention is legally impermissible because it is

in violation of the Directive Principles of the State Policy

enshrined in Article 39 of the Constitution of India.

VIEWS OP INDIAN SCIENTISTS

India's foremost Scientists workinc on drug research and

manufacture are also against Indie joining t^e Paris

These include Dr. vi tya "and,

Convention.

of Central Drug Research Institute.

former Director

They have warned that

joining the Paris Convention will crir 'le research and

development

'nd technological development,

not only in the

traditional Drug Industry hut also in the new area of

biotechnology which holds enormous promise of creating a

whole of new Drug & Vaccine Industry.

VIEWS OF INDUSTRY

In 1986,

Government had asked FICCI,

FIEO,

PHDCCI & ASSOCHAM

to give their views about joining the Paris Convention.

Except ASSOCHAM,

all other organisations had recommended to

the Government that India should not join the Paris Convention.

Last year,

a three-member Committee,

Ganguly of Hindustan Lever Ltd.,

Mr.

Mr.

consisting of Mr.Ashok

S.Laha of IEL and

S. Ganguly of Engineers India Ltd,

examined the issue of

joining the Paris Convention.

Although two of the three

Committee Members belonged to MNCs,

the Panel gave a verdict

to the effect that the balance of advantage did not favour

India signing the Paris Convention.

INDO-AMERICAN CHAMFER OF COMMERCE

In 1986,

Indo-American Chamber of Commerce published a study

on protection of intellectual property by Mr. Ashok Pratap,

Barrister-at-Law,

1988.

This publication has b^en undated again in

It deals with all the four forms of intellectual pro

perty in India as elsewhere : Patents,

and Designs.

Trade-marks,

Conyrights,

The study has made a thorough analysis of the

subject comparing statutory provisions in India and in a

number of other countries developed and developing.

The

conclusions are reproduced as follows :-

" CONCLUSION ON PATENTS POSITION IN INDIA

Viewed, therefore, in the totality of the circumstances,

the historical background, the stage of economic deve

lopment and the relative positions of various other

similarly placed countries the Indian Patent legilation

offers adequate and substantial protection to inventiveness

and, with the possible exception of certain narrow and speci

fic areas, is generally of a standard found in other parts

of the world.

This should generate more confidence and less

concern" .

XXXXXXXYYXXYXXXXXX

" CONCLUSION 0M INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY IN INDIA

All of the foregoing should demonstrate that the concent

of the importance of intellectual property in India is

established soundly at all levels : statutory, administ

rative and judicialThe an-'licable provisions do, as

they indeed must, take into account the felt necessities

of the times but this is not done at the cost of the

foreigner.

The comparative studies presented here show

that India is not out of step and in fact enjoys perhaps

the longest history and experience in these matters in

the developing world.

Although industry and Government

can both take a greater part in ensuring enforcement, the

indications are encouraging.

The indepth investigations

and studies undertaken and directed by the Government

from time to time evidence the intent and willingness

to change and adapt as times and needs requirs.

The

example of the film industry hopefully portends a

trend.

In sum, the protection of intellectual property

in India is alive and well."

SUM UP

To sum up,

India signing the Paris Convention or modifying

the vital provisions of its Patents Act, 1*570 diluting its

philosophy in any way is totally not in the national interest

and economic development of the country.

In regard to the

pharmaceutical field in fact Mrs. Indira Gandhi,

Prime Minister,

the former

made the following bold statement at the

World Health Assembly at Geneva in May, 19 81 on natent

protection :

"

My idea of a better ordered world is

one in which medical discoveries would

be free of patents and there would be

no profiteering from life or death".

CONVENOR

National Working Group on Patent Laws

TABLE

COMPARATIVE PROVISIONS IN INDIAN PATENTS ACT 1970 & PARIS CONVENTION

ON MAJOR ASPECTS OF PATENT SYSTEM

INDIAN PATENTS ACT-1970

ASPECT

1- SCOPE

PARIS CONVENTION

Law permits both product and process patents. Process

Patents are for food, medicine, drug, chemical substanCes:

For others : Product Patents

System provides for product patents. Extends

to Industry and Commerce, Agriculture, extractive industries, natural products.

Agriculture products and processes for treatment of

human beings or animals are not treated as inventions;

hence not patentable.

Covers patents of importation, improvement

and addition.

Atomic energy inventions are also not patentable.

II. TERM

5/7 years for food, medicine, drugs and chemical

substances.

14

years for others.

LTCZusiNG

Compulsory licences granted after 3 years if

reasonable requirement of public interests not satisfied

about availability; reasonable prices.

LICENCES

(a)

Government may apply after 3 years suo-moto

endorsement in public interest for any patent.

(b)

Licences of Right is deemed to have .been endorsed

after 3 years in regard to the process patent for

food,medicine, drugs and chemical substances.

COMPULSORY

OF right

No period specified.

Member countries have different periods viz.

U.K.:20 years; Japan : 15 years;U.S.A.:20 years;

China : 15 years; Spain : 20 years

Compulsory licence can be applied on the ground

of failure to work or insufficient working after

3 years of grant - shall be refused if patentee

.justifies inaction by legitimate reason.

No provisions for Licences of Right.

REVOCATION

Revocation order if first compulsory licence is not

worked in 2 years - orders issued within one year

thereafter.

Revocation proceedings instituted two years after

grant of compulsory licence. Proceedings may take

any length of time.

RIGHT OF

P'RWTTY

No provision.

Right of priority extendable for 12 months in a'l

member countries from the date of registration

in any one country.

UNFAIR

COMPETITION

Infringement proceedings are possible.

Member countries have to assure effective

protection against unfair competition Reason : contrary to honest practices.

OCCASIONAL PAPER MQ.?

I -Pitfalls Of The Paris Convention

By SURE.NDRA J. PATEL

NDIA’S position about not joining

the Paris convention has remained

well-settled since independence. Our

three successive Prime Ministers.

Pandit Nehru. Shaslriji and Mrs

Indira Gandhi, had resisted all press

ures. particularly from foreign trans

national corporations and their

domestic supporters, to join the

convention

Instead, they had

directed our policy towards revising

both the national patent and

trademark laws and the Pans con

vention. in order to safeguard India’s

national interests of rapid develop

ment.

Our longstanding position of not

joining the Pans convention, unless

it is basically revised, is now being

reconsidered A committee of five

men. under the chairmanship of Dr

S. Ganguly, chairman of the IPCL,

has been established to advise the

government whether lojoin or not to

join the Pans convention. Il is im

portant. therefore, that the basic

issues which had guided India for all

these long years against joining the

convention, arc examined once

again so that their full awareness

would show why there is no ease for

a Hamlet-like hesitation on the sub

ject.

A public discussion of this esoteric

subject is hampered by the general

ignorance of what the patent and the

trademark system and its guardian.

the Paris convention, arc all about.

A patent (and a trademark) is an

exclusive grant by government to an

individual or a legal person to re

strain all others from making, im

porting. offering for sale, selling or

using in production.thc products and

processes covered by the grant, h is

thus the grant of a monopoly to

prevent others from imitating,

adapting, improving and producing

these items. Quite clearly, the con

flict between private gains and pub

lic interests or national needs is at

the very heart of the system.

The major industrial countries

have always been the strongest ad

vocates of the system. The imperial

powers — Britain. France. Belgium,

the Netherlands. Italy. Germany —

imposed it tn their colonics upon

conquest. And the United States did

the same in the Latin American

countries under its domination. In

dian patent law was introduced as

early as in 1859. just a few months

after the suppression ol India s first

rebellion against the British. No

wonder, it was among the very first

laws given by the crown. It reserved

at one stroke and for all time Indian

markets for the British exporters. A

similar situation was created in all

other colonics and semi-colonics.

I

3.5m. Patents

There arc some 3.5 million patents

in the world. Of these, the third

world’ countries have only 200.000.

The nationals of the third world hold

only 30.000 of these, that is. less than

even one per cent of the world total.

The other 170.000 — or 85 per cent

of the total — are held mostly by the

powerful transnational corporations

of the United States. United King

dom. Germany. France. Switzerland

and Japan. To add injury to insult,

not even five per cent of these

patents arc used in production in the

third world. In India too, foreigners

held 80 to 90 per cent of all patents.

few of which were ever used in

production.

The system thus reserves the third

world markets for the foreigners. It

perpetuates perverse preferences, or

reverse reservation It is a system

mainly for the benefit of foreigners.

but legalised, operated and even

subsidised by the nationals — a

system guaranteeing private foreign

gains at public cost to the third world

countries. In the comity of nations.

the third world accounts for 75 per

cent of population, 20 per cent of

income. 30 per cent of trade, and

about 40 per cent of enrolment in

higher education But its share in the

world patent system is only I per

cent. The present system, designed to

protect the foreign interests; has thus

remained the most unequal and

most unjust of all the relationships

between the developed and the de

veloping countries.

The Paris convention serves as the

guardian of the patent system. It.

therefore, legitimises all the ine

quities of ihe patent system sum

marised above. The contention was

established during the 19th centuryon the initiative of the United Slates.

It was signed in Paris in 1893, at the

lime the Pans world fair of industrial

products of’’all" nations w as under

way. Many governments, mostly

from the less industrialised countries

in Europe, had serious misgivings

about such a convention which they

fell, would serve the interests of the

patent holders in the then "de

veloped countries” (USA. Switzer

land. Germany. France and the UK)

and thereby adversely affect their

national interests and industrial de

velopment.

This opposition was skilfully

handled. The USA brought with it to

Paris, aboard the same steamship, its

protectorates—Brazil. Ecuador, El

Salvador and Guatemala, and

France brought in Tunisia—to

create a majority through block

voting.

THE TIMES OF INDIA. BOMBAY

Since then, the convention has

remained for long, "a rich-man’s

club It was revised six limes—in

1900. 1911. 1925. 1934. 1958 and

1967. But each revision only further

strengthened the rights of the

foreigners.

Basic Asymmetry

The basic asymmetry between the

interests of the foreign patent holders

and the nationals of the third world

countries, runs all the way through

the entire structure of the conven

tion. Its first article is devoted to the

definition of the coverage of indus

trial property. Its very next article

guarantees equal treatment to

patentees from all countries—both

the rich and strong, and the poor and

weak. We have come to know well.

how such "spurious equality" be

tween the very strong and the very

weak.

actually

perpetuates

preferences for the powerful foreign

multi-national enterprises. The Pans

convention furnishes, yet one more

classic example of this, along with

nuclear non-proliferation treaty and

such "international legislation”.

The convention then spells out in

detail how the signatory countries

have to pass new laws, or adjust the

old ones they already have to con

form to the basic thrust of the

convention—to protect only the

rights of the patentees while being

silent on his obligations. This is

clearly embodied in the watereddown historic compromise con

tained in article 5. A century-long

legal battles have not produced even

a few favourable judgments safe

guarding public intesrst.

The convention has a unique sys

tem implicit in the provision on its

revision—only by complete una

nimity. The veto system was thus

not invented just for the United

Nations security council. The Paris

convention had started it long before

finally.

The process of withdrawing from

the convention is both tricky and a

long one. It would involve at least

five to six years.

These are the reasons why the

summit conferences of the nonaligned movement and the group of

77 have forcefully called for a basic

revision of the Paris convention.

(To be concluded)

The author, former director erf the

.technology division of UNCTAD

(Geneva) is currently Sr. adviser.

World Institute of Development

Economics Research (UXU). Hel

sinki.

Courtesy - Author

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 8, 1987

II — Pitfalls Of The Paris Convention

HE post-war world saw the col

lapse of imperialism and the

independence of the colonics The

newly independent countries began

to perceive the perversity of the

patent system, the inequity of the

Pans convention.

The third world countries called

for a basic revision of both. As

director of UNCTAD’s technology

division. I was closely associated

with this process. India was in the

forefront of this crusade, acting as

the natural spokesman of the de

veloping countncs, or the Group of

77. as it came to be called in

UNCTAD.

The skill with which Indian rep

resentatives

marshalled

the

evidence, won the respect and ad

miration of the Group of 77.

As charity begins at home, India

was. therefore, among the first coun

tries to revise in 1970 its Britishimposed patent law. The new law

was a long step forward.

Above all, it changed the very

objective of the system — denying

monopoly to foreigners for the im

ports of the patented articles and

centring the system upon encourag

ing national inventiveness and

securing working of the patents in

the production system.

It contained several departures. It

excluded entieal sectors of national

interest from patentability — agri

culture. processes of treating human

beings and animals, inventions relat

ing to atomic energy (alicady made

unpatentable by section 20 of the

Atomic Energy Act of 1962).

Il prohibited the grant of patents

to products for food, pharmaceutical

and chemicals and limited it io only

processes.

The duration of the patent grant

was cut down to only 5 years tn these

items of critical national interest, it

introduced automatic endorsement

for “licences of right" so as to use the

patents in production in order to

promote national development.

T

Patent Act

India’s 1970 patent Act became a

model for other third world coun

tries. They too revised their patent

laws. In consequence, the third

world pressures for the revision of

Jhc Pans convention mounted in

UNCTAD.

During discussions on the re

vision of the Paris convention in

various forums of the World In

tellectual Property Organisation

(WIPO), Geneva, the group of de

veloping countries have maintained

that any industrial property system

must fulfil the developmental needs

of the non-mdustnalised countries.

Today. India has about 1000 in

house R and D units in public and

private sector industrial companies,

and major investments in publicfunded R and.D through the Council

of Scientific and Industrial Research,

Indian Council of Agricultural Re

search. department of atomic energy.

department of space, department of

defence research and institutes of

higher technical/scienlific educa

tion.

Trump Card

India is, therefore, at a stage of

making a competitive entry into

international markets on technology.

Il is at this stage lhal the highly

induslnahscd countries through the

Pans convention can do maximum

damage by blunting the edge of

India's

developing

innovative

capability.

This is the background for India’s

refusal io join the Paris convention.

India's remaining outside the con

vention has served as the strongest

card in the negotiations to revise the

Paris convention. Il has enabled it to

adopt a new patent law safeguarding

ns national interests.

Thus there is no change in the

fundamental reasons why India has

all along refused to join the Pans

convention.

In fact, the needs for India’s social.

economic and industrial develop

ment in the present phase, make the

arguments against joint the conven

tion still more valid.

The appointment of the Ganguly

committee has. therefore, under

standably caused widespread con

cern that this position may now be

compromised.

Several recent developments have

in fact reinforced the grounds for

India's refusal to join the conven

tion. Joining it will compromise

some of the most

important

provisions of our 1970 patent law.

That will underminc the develop

ment of national industries, particu

larly in the pharmaceutical Geld.

According to Dr S. Vcdaraman. for

mer controller general of patents.

sections 5. 10(5). 47. 66. K7. 88. 91.

91. 99 and 102 of the Patent Act

would require modification if India

joined the convention.

According

to

justice

V.

Scthuraman of the Madras high

court, section 23( 1) of the trade and

merchandise Marks Act and section

28 of FERA arc inconsistent w ith the

Paris convention. Similarly, section

20 of the Atomic Energy Act of 1962

wjJJ face modification.

There is a formidable legal con

sensus among four former justices of

the supreme court, who have come

out against joining the Paris conven

tion. They arc justices J. C. Shah. Y.

V. Chandrachud. M. Hidayatullah

and V. R. Krishna Iyer.

As is widely known, these four

justices have in the past differed on

several issues. But they are unani

mous that joining the convention

will require ’’abrogation" of several

provisions in our patent law and

“will seriously harm the economy of

the country."

Drug Element

Justice Shah considers that in his

opinion, joining the convention “is

legally impermissible because it is in

violation of directive principles of

state policy enshrined in article 39”

of the constitution. It will also lead

to “the infringement of fundamental

rights” as protected by statute laws.

The Indian drug manufacturers’

association has expressed its strong

opposition to joining the conven

tion. It considers that such an Act

would undermine the progress we

have made in developing rapidly our

national drug industry

Since 1976. drug production in the

national sector has increased 3.4

times, with that by multi-nationals

more or less unchanged. The FICCI

had established in early 1986. a

special sub-committee on this ques

tion. which came out against joining

the Pans convention. FICCI's views

were communicated to the govern

ment on May 7, 1986.

Our foremost scientists working

on drug research and manufacture

arc against our joining the Pans

convention. These include Dr Nitya

Anand, former director of the Cen

tral drug research institute.

They have warned that joining the

Paris convention would cnpple R

and D and technology development

not only in the traditional drug

industry, but also in the new area of

bio-technology,

which

holds

enormous promise of creating a

whole new drug and vaccine indus

try.

In summary then, economists of

all shades, supreme court justices.

outstanding scientists. FICCI and

IDMA have added their strong

voices to reinforce India’s de

termined stand not to join the Pans

convention.

That

stand

was

forcefully

articulated by the late Prime Minis

ter. Mrs Indira Gandhi, in an address

delivered at the 34th session of the

world health assembly on May 6.

1981 in Geneva. There she stated.

“My idea of □ better ordered world

is one in which medical discovenes

would be free of patents and there

will be no profiteering from life or

death."

India and Brazil, supported by the

rest of the Group of 77 and the

socialist countnes, finally succeeded

in mid-70’s to initiate the formal

process of the revision of the Paris

convention — a revision in a direc

tion completely different from that

in the earlier six revisions of the

convention.

1

his time the pendulum was to be

pushed in the other direction —

safeguarding the interests of rapid,

industrial development of the third

(Concluded)

world. But even after eight years of

Courtesy- Author

negotiations. the revision process is

still stalled by the fierce opposition

THURSDAY. APRIL 9. 1987. THE TIMES OF INDIA. BOMBAY

of the western industrialised coun

tries

OCCASIONAL PAPE-R-gOfS

Indian Patents Act, Paris Convention and

Self-Reliance

IX IS Mehrotra

The Indian Patents Act of 1970 has been hailed as one of the most progressive of such legislation in many

countries as well as by UNCTAD. It offers several advantages to entrepreneurs, scientists and technologists and

to consumers. The provisions of the Act help India ensure that blocking and repetitive patents are not allowed

to stifle technological and industrial self-reliance.

According to the Paris Convention rhe protection of the industrial property and rights of patentees has supremacy

over the interests of any country or its people More than 99 per cent of the 3.5 million patents held by individuals

or corporations arc in developed countries and the Convention largely helps them maintain their monopoly in

member countries. If India joins the Convention now, it will be bound to give wider rights to the nationals of

all member countries without matching reciprocity. The disadvantages for India far outweigh notional advan

tages jor any activity, be it in the area of innovation, technological development or industrial self-reliance.

OF late, there has been an increasing de

mand that India should join (he Paris Conventien and if possible, modify its Patent Act

of 1970. This is despite denials by the

government against any such move. This de

mand for revising our progressive Patent’s

Act is certainly not sudden and is perhaps

a pan of the recent campaign to open up

the Indian economy to multinational cor

porations (MNCs) in the false hope of get

ting nex technologies. Large developing (and

emerging) nations like India offer such vast

markets that the efforts to control these

(even through unfair trade practices) are not

only made by these multinational companies

alone but also by the governments of the

developed countries representing them. Thus

the role of dc\elop<d countries during recent

debates m GATT should sufficiently caution

the countries like India if they have any

concern for self-reliance.

Historically, though India was not a

member of the Paris Union, its Patent Act

of 1911 was so retrograde that it allowed a

virtual monopoly of (he Indian market by

technologically advanced countries. Though

after independence, the importance of modi

fying the then existing Patents Act (of 1911)

a as amply realised and two expert commit

tees headed by Justice Rajagopala Iyengar

a^d Justice Bakshi Tek Chand went into

great oetail into the issues of modifying the

men Patent Act. Both the commissions

found ample evidence of misuse of patent

protection by foreign companies (who owned

more than 90 per cent patents in India) and

it was clear that many patents were taken by

the MNCs basically to ensure protected ex

port markets. Thus it was observed that the

country was denied by its own national law

the right of gening, in many cases, goods

otn though they were essential for industrial

production:, or for the health and safety of

the community, at cheaper prices available

from alternative sources because of patent

protections. A national conference of scien

tists also provided the basis for changes in

the Patent Law which was extensively

debated as a Patent Bill by a joint select

Economic nod Political Weekly

committee of Parliament, which invited ex

perts from all over the world to give their

experience and opinion.1 Such thorough

debates for almost a decade had to take

place and bills seeking changes had to lapse

more than once, before the New Patents Act

of 1970 came into being.: All this delay oc

curred in changing the Patents Act of

independent India primarily because of

“heavy criticism from abroad” and opposi

tion to these bills by the associations

representing interests of MNCs in India.

The Indian Patent Act of 1970 has been

hailed by many countries including United

Nations agencies like UNCTAD as one of

the most progressive Patent Acts, i he basic

approach of this Patent Act has been to

strike a balance between the interests of an

inventor and those of a consumer and to en

sure that the benefits of new technological

developments reach the people and not be

exploited by the-inventor alone for monopoly

control. It expects that patents are granted

to encourage inventions and to secure that

inventions arc worked in India on a commer

cial scale and to the fullest extent that is

reasonably practical without undue delay

and that they are not granted merely to

enable patents to enjoy a monopoly for the

importation of a patent article.

Three advantages arc available in the

Indian Patents Act of 1970. The first applies

to Indian entrepreneurs, manufacturers and

the government to ensure commercial pro

duction of a patented product (or through

a patented process) in India where an MNC

or any other person may have filed a block

ing patent to maintain a market monopoly

for importation of the patented product in

India at exorbitant prices. 1 he second apply

to Indian scientists and technologists enabl

ing them to obtain patents cm products and

processes after modifications on esi.-tm.;

patents. This was not possible earlier due to

virtually all-encompassing patents which

were allowed by the Patents Act of 1911

similar io which the provisions also exist in

the Pans Convention. The third type of

August 22, 1987

advantages accrue to the consumer since

(a) even patented products can be imported

from manufacturers in the countries where

such patent protection may not be available

and (b) competition in the production of

even the erstwhile patented products causes

a decline in the local prices, if the produc

tion can be ensured through indigenously

developed (or imported) modified process

This'is particularly true in the area of food

and drug products where no product patent

is allowed in India and even the process pa

tent is allowed only for a short period of 5

to 7 years.1

Some of the specific positive features of

Indian Patents Art of 1970 are “revocation

of patents in public interest (article 66. 89);

licences of right (article 86. 87); compulsory

licensing being mote rigorous (article 84, 97);

licensing of related patents (article 96);

power of the government to use inventions

for the purposes of government (article 100)

or in the public interest even to third parties

(article 101), acquisition of inventions and

patents by the central government (article

102). Besides not allowing product patents

on food and drugs, patents arc also not

granted for products related to atomic energy

and space applications. Article 47 of the /Xcl

provides that the government can even im

port patented m-.dicines and drugs for their

own use or distribution to

v’sye.warics;

hospitals or medical institutions’.

It should be clear that the above provi

sions not onlv help the Indian consumer but

also help India ensure that blocking and

repetitive patents are not allowed to stifle

technological and industrial self-reliance It

may be worthwhile to note that many of

these provisions of the Indian Patents .Act

have been adopted by a diplomatic conference

under WIPO in the proposed revision o!

various articles (particularly article 5 and 5

ter) of the Paris Convention. Most of these

provisions arc made to remove hindrances

that are placed by the patentees on working

of their patents 4

1461

Paris Convention and Monopoly

of Patentees

(ii)

Membership of convention will help broad base of scientific research. While

non-resident Indians to return to India.

.opinions on the cxteqi of contribution of

(iii)

Indian Patenting abroad is beco’mrng'indigenous • scientific And technological

On the contrary, Paris Convention has

important for India from the angle of research to development of technology and

philosophy according to which protection of

industrial base in India may differ, it is not

exports.

industrial property and rights of patenfee are

(iv)

International protection for Indian debated that the contributions of indigenous

given supremacy over the interest of any

patents abroad will encourage scientific research right from agriculture to space

country or its people,5 Though there have

technology and industrial research have

research in India.

been several modifications in the original

(v)

Faster information flow on patents is made significant impact on the growth of

convention of 1883 because of six revisions,

an essential rquirement for the sound deci indigenous industrial development.12' 15

less developed countries (LDCs) have been

Major components of technology are the

sions on foreign collaborations and this re

dissatisfied with several provisions of the

quirement can be met only by the member know-how and capability to perform a given

convention which put fetters on their na

task. Since the inventors and developers of

ship of Paris Convention

tional administration in the interest of pa

(vi)

Better climate for patenting by the technology would like to derive some bene

tent holders, who are almost invariably from

foreigners in India will enable India to fits from their endeavour, they like to keep

developed countries. While many subsequent

obtain technical collaborations rather than both the know-how as well as these capa

amendments have been more favourable to

having to seek turnkey projects of foreign bilities as secrets to themselves. In order that

patentee, 20 countries of the union have not

collaboration arrangements having a wider the benefits of this technological develop

signed subsequent amendments to the Paris

scope.

ment arc shared by others without prejudice

Convention.6 These countries have thus

(vii)

Membership of the convention will to the interests of the inventor, a system of

safeguarded their interests by not subscribing

help India in getting a better deal in acquisi patents-and inventors’ certificates had been

to these adverse clauses of the convention.

tion of technology from small and medium introduced-. While a patent provides the

However, countries like India who may join

companies and motivating foreign investors patentee the right To exclude others from

now have no such option and are thus faced

to transfer the latest technology.

using the patented invention (subject to na

with a situation where they will be bound

(viii) Membership will help India to in tional law), the owner of an inventor’s certi

to give wider rights to nationals of such 21

tervene in the revision of the convention.

ficate has the right to receive remuneration

countries without matching reciprocity.

It will be appropriate to examine carefully for the use of invention while the exclusive

Some of the specific provisions of the Paris

whether the above mentioned propositions right is transferred to the state.14 While the

Convention which deserve special mention

bring out any real advantage to a country patents and other forms of intellectual pro

in this regard are Rights of priority (arti

like India in its scientific, technological, or perty rights do provide an incentive to the

cles 4C(4), 4F and 4H) , right to patent

inventors, they also allow them to control

self-reliant industrial development.

despite restrictions or limitations resulting

technology transfer as well as further

from the domestic law (article 4 quarter), no

Patents, Technological Develop technological development tn many ways. It

forfeiture of industrial designs despite failure

should, however, be recognised that while the

ment and Industrial Self-reliance

to work or importation of protected articles

patent licencee may not give any information

Let us first examine the role of patents in on know-how and technology, the patentee

(article 5B), convenient excuses against com

pulsory licensing (article 5A(4), no permis

technological and industrial development. may not allow exploitation of a technology

sion to import patented products (article 5

Industrial development requires both the even if others have know-how and other

quarter), effective protection against unfair

capital and technology, besides raw materials details of technology utilisation. This is

and the human capability to make effective becoming increasingly important due to the

competition (article 10 bis), amendment of

use of these sub-systems. The Scientific fact that most of the technologies as well as

domestic law to give effect *o the provisions

Policy Resolution of the Indian government patents are today controlled by MNCs from

of the Paris Convention (article 25) and bin

of 1958 stressed the key role that technology the developed countries.16 Thus, the in

ding of at least six years before any country

plays in industrial development.9 However, ternational trade in technology is between

can leave the convention after joining it once

(article. 26(3) and (4) ). The above articles

it must be kept in mind that the technology unequal partners and this imbalance is used

should not only suit the socio-cultural- by developed countries and their MNCs for

in essence ensure that a patentee can con

economic milieu of a nation but should also economic, technological and industrial ex

tinue to misuse his patent rights against any

be under national control, rather than ploitation of developing countries through

concern for the rights of the states (or its

jeopardising its self-reliance. This was amply restrictive business practices.17 It was

people) who grant these rights and privileges

realised by the Industrial Policy Resolution against this monopoly and exploitative con

to the patentee. Thus, even if the patentee

of 1956 of the Indian government.10 In fact, trol in science and technology that UN

is not at all interested in working his patent,

the Scientific Policy Resolution of 1958 was bodies like UNCTAD have been constantly

it becomes very difficult to enforce the work

in that context a natural corollary to the In raising their voice, demanding that the

ing of the patent or import the product of

dustrial Policy Resolution.*1

the patent except from the monopoly

benefits of modern science and technology

Technological developments in a country should also reach developing countries and

patentee. Thus, "an overwhelming majority

can be based both on indigenously efforts have been made by UNCTAD to

of patents granted to foreigners through

developed technology as well as on import develop an international code of conduct for

national laws of developing countries have

of the required technology. To a developing transfer of technology.18 It is in this context

been used as import monopolies."7

country like India, it is often contingent to that one will have to examine the role of in

Despite the fact that about 99 per cent of

import the required technology since it ternational patent treaties like Pans Conven

the 3.5 million patents are currently held by

cannot always wait for its indigenous tion and their influence on technological

residents or corporations of developed coun

development. However, even the import of development and industrial self-reliance of

tries and that the Paris Convention largely

technology is influenced by the technological an emerging, though developing country like

tries to help these patentees in maintaining

status of the importing country and the India, in order to find correct answers to the

their monopoly in the member countries,

assimilation and development of such im advocates of Paris Convention.

some of the advocates of Paris Convention

ported technology is governed by both scien

have been arguing in favour of India’s join

tific as well .as industrial capabilities.

ing the convention on the following

Paris Convention and Indian

Recognising the importance of tecluiological

grounds:8'

Technological Self-Reliance

(i)

Membership of Paris Convention is im development and the role that science and

Given the character of the Paris Conven

technology plays in today’s society, Indian

portant for obtaining better facilities for the

planners encouraged the establishment of a tion described earlier, let us sec how India’s

Tiling of foreign patents.

1462

Economic and Political Weekly

August 22, 1987

joining this union at this stage will help it

Convention, Indians just as any other ting in India (and other non-member coun

in any concrete terms. If we analyse the

members will have to file patent applications

tries) the processes based on incremental in

grounds on which it is advocated to jcrin the

in all the countries where they want any legal

novations but also of manufacturing thes.

Paris Convention, these enn be broadly

rights on patents. The only advantage that

products in India as well as exporting tech

classified under three categories. Analysis of

they do not get now is of getting automatic

nology and their products to non-member

these claims under oil these three categories

priority of 12 months in filing a patent in

countries. The case of the pharmaceutical

are given below:

any country of the convention. The lack of

industry is a well known example where

I

Procedural advantages offiling patents this single advantage to India’s in a selected

Indian inventors and industry have been able

abroad, getting information on patenrs and

few cases of patents, which have been of

to achieve such advantages only because of

priority rights in the member countries

consequence, has not created any problem

the Indian Patents Act of 1970 and India not

All these advantages arc relevant if Indian

in the past and is not likely to create any pro

being a member of Paris Union. Thus Indian

inventive activity was at a level where Indians

blem till such a time that Indian innovative

pharmaceutical industry today produces

have to file a large number of patents

activity reaches a level which requires its con large number of drugs for which interna

abroad. However, Indian research and deve stant transfer to other developed or develop

tional patents are yet to expire (Thblc 3),

lopment activity in most areas is unfor

ing countries. Today, India does export tech besides having large number of process

tunately still at a stage where not many new

nology to other developing countries (and

patents based on incremental technological

inventions are often made, particularly of in a few cases, even to developed countries),

advancements. The Paris Convention (arti

the type that require patenting abroad, more

none of this technology, however, has any

cle 4) provides priority even for elements

so which have the potential of working

significant patent protection value (Table 2).

which do not appear among the claims for

abroad. For example, out of 300 parents

Il is not likely that this picture is going to

mulated in the application in the country of

granted to CS1R since 1981, only a few could

suddenly change to let Indiabecomc a major

origin. Such provisions can influence the ex

technology (patentable) donor, requiring

isting advantage of incremental innovation

be licensed or worked abroad. This is Largely

urgent measures to derive advantages of that developing countries like India enjoy

true of other research organisations and

today.

units also, both in the public and private sec priority offered by the Paris Convention.

On the contrary, Indian innovators today

It was for such reasons alone that almost

tors. There are no indications of any signifi

have a definite advantage of not only paten 40 countries of the world do not offer pa

cant changes in the objectives of Indian

R nd D agencies or in their character of

Table 2: CS1R Technologies Exported to Various Countries

R and D, programmes expect a boom in

Indian patenting activity abroad. Even the

extent of Indian’s filing patents in India itself

has been almost constant in the decade

1974-75 to 1983-84 (Table 1). In fact patents

contribute only marginally as incentive to

worthwhile inventive activity whereas several

other factors namely climate for technology

supply, market demand, pattern of industrial

development, industrial R and D nature of

training and education, etc, are more impor

tant.’9 Thus, merely joining the Paris Con

vention or giving more rights to patentee is

not going to significantly increase lhe in

novative activity in India. Several! other

changes are probably more imponann in this

regard.:0- 2,1 22

Even if we assume that there is ai likeli

hood of increased inventive activity i.n India

which would demand filing abroad of more

patents by Indians, do Indian inventors face

any specific problem(s) that could be solved

by joining the Paris Convention? So far as

translation facilities in several European

languages is concerned, these are available

to Indian patentees through the European

Patent Office w here a patent filed in zmy one

language is automatically translated into all

other European languages. So far as. actual

Tiling of patents is concerned, Indians even

today do file patents in other countries (in

cluding those which are members cf Paris

Convention).. Even after joining the Paris

Countries

Technologies

1

Burma

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Malaysia

Nepal

Philippines

Sri Lanka

USA

West Germany

Egypt

Indonesia

Menthol, sodium alginate, bentonite, electrolytic manganese

dioxide, miltone, orange juice concentrate, glue and gelatine.

calcium carbide, potassium schoenite, terpincol, diosgenin and

progesterone, phenol-formaldehyde, model distillation column.

electro-chemical metallurgy, workshop, straw-board and special!

ty paper, hard board, special laboratory equipment, electronic

instruments (pH meters, etc.)

Spice-oleoresins.

High-draught kiln, spice-oleoresins.

Active carbon from saw-dust, fish meal.

Buff coloured green pepper.

Syntan-PKR.

Suri transmission.

Rice bran oil.

Water filter candle.

Table 3: Illustrative List of Bulk Drugs for which Technology Could Be

Indigenously Developed Or Acquired, and Production Undertaken

is a Consequence of Patents Act of 1970

Period when the Patent

Expires/Expired

Name of the drug

1981

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

Ibuprofen, clofibrate. tetramisole and verapamil

Allopurinol, betamethasone and derivatives (1984-87)

Tinidazole, chromoglycate

Lorazepam

Pyrantel

Propranolol

Mebendazole, salbutamol, clotrimazole, ketoprofen levamisole.

bumetamide

Cimetidine, metoprolol

1992

Table 1: Number of Applications for Patents from Persons in India anu Abroad Year-wise from 1974-75 to 1983-84

1983-84

Indians

Foreigners resident in India

Foreigners resident abroad

Total

1982-83

1,055

25

2,065

3.145

1,135

1,950

3,085

1981-82

1,093

19

1,877

2,989

1980-81

1,159

19

1,776

2,954

1979-80

1978-79

1977-78

1976-77

1975-76

1974-75

1,055

37

1,888

2,980

1,124

13

1,795

2,932

1,097

37

1,736

2,870

1,342

23

1/39

3,104

1,129

34

1,833

2,996

1,143

66

2,192

3,406

Source: Annual Report.

Economic and Political Weekly

Au gust 22, 1987

1463

ship of the Paris union under such a lame

excuse.

Thus, it is apparent that at this juncture

the disadvantages to India in joining the

Paris Convention far outweigh some no

tional advantages for any given activity, be

it innovative activity, ’ethnological develop

ment or industrial self-reliance. India has

therefore, wisely decided against joining the

Convention unless it is modified so as to be

a balanced tool of interest both to developed

as well as developing countries. A country

like India can mobilise more pressure from

outside (through forums like NAM and

UNCTAD, etc) for such changes in the Paris

Convention than by joining it. Moreover.

once it joins the Convention, it cannot walk

out of this union for at least six years dur

ing which enough blocking and repetitive

3

Help in Technology Acquisition and patenting may be done by th£ vested interests

Development

of industrialised countries. For those who

According to the fourth Reserve Bank of still want to advocate India’s membership in

India Survey, 40 per cent of the companies

the Convention, we pose a set of questions:

covered were able to obtain technical colla

* I In how many cases in the last 15 years

boration agreements despite Indian absence

have Indian inventors incurred losses due to

lack of simultaneous filing priority (an ad

from the Paris Convention, compared to 35

per cent of the companies covered in the vantage which is likely to be available as a

result of joining Pans Convention)?

third survey. This clearly indicates that the

technology market is becoming interna

2

In how many cases in the last 15 years

tionally competitive to allow access to

has technology import been refused/delayed

technology even without membership of due to India pot being a member of Paris

Paris Convention. This is equally true of the Convention?

3

In how many cases has patent/infoma2

Patenting Advantages to Indians for fact that more progressive patents acts not

lion been rcfused.#delaycd to India because

Patenting Abroad and Increase in Indian In only in India but also in other developing

countries like Mexico and Colombia have of it is not a member of Paris Convention?

ventive Activity

not negatively influenced the inflow of

4

How often in the last 20 years has

As discussed in the earlier paragraphs, the

technology or direct foreign investments in. patent protection been used as a tool to stop

inventive activity in India is not likely to sud

these countries.24 While the foreign

the import of (a) new products (e g, drugs,

denly increase. Moreover, the argument for

technology donors would prefer more etc) and (b) new technological process (par

better patent protection abroad to get more

favourable patents acts, the patents clearly ticularly before the introduction of our new

returns to Indian inver.tors/researchers to

are not becoming any hindrance in tech Patent Act of 1972)?

protect against infringements abroad with

5

Can India join Paris Convention

nology transfer.

the accession to Paris Convention is hardly

without really modifying its Patents Act as

valid. When we look at (a) priorities of

Thus, out of 371 companies having also (he trade-marks and design Act?

Indian R and D. (b) extent of cross-licensing

technical collaborations in the fourth RBI

6

Is India changing its own stand at the

of patents in our technology transfer

Survey only four cases in the private sector

UN (UNIDO. UNCTAD, etc) and NAM

agreements and (c) the nature of export and

(0.1 per cent) involved patents and

where it has been advocating against join

manufacturing activities abroad.

trademarks together or patents alone.13 It

ing the Paris Convention until it is modified

was only in 24 per cent cases that patents in the interest of developing countries?

Most of scientific and technological

or trademarks were involved with know-how

research in India is done in government

in technology transfer. In 80 per cent of the

funded R and D institutions and their

Notes

580 cases of the total technical collaboration

research objectives have hitherto often been

agreements, Indian collaborators were

of generating technology tor indigenous

(Views expressed in this paper are those of the

granted exclusive rights by the foreign col

markets, utilisation of its resources and pro

author and not necessarily of NISTADS]

laborators. A large number of small and

viding services to industry and other service

I

Minutes of the Joint Select Committee on

medium size firms have also been transfer

sectors and assimilation of imported techno

the Patents Bill of 1967 cited in IDSfA

ring their technologies to India. They have

logies, besides conducting basic research to

Bulletin,

XVI1 (12), 19S6, Supplement Pares

also

been

patenting

in

India

in

considerable

keep abreast of frontiers of international

1-48.

strength. Similar has been the experience of

research. Thus, it was natural that our paten

2

U

Baxi

in “Inventive Activity injhe .Asian

many other developing countries "parti

ting activity was of little commercial con

and Pacific Region", WIPO, 1980. pp

cularly for the development of relatively

sequence. Without major changes in our

95-102.'

science and technology policies and the

labour-intensive and small-scale industries"

3

"The Patents Act. 1970" Eastern Book

with "less restrictive terms and conditions

character of the S and T infrastructure

Company, Lucknow. 1985.

than large TNCs” and in a manner as to

(namely larger role of corporate sector), it

4

A K Koul, ‘Technology. Paris Convention

“allow for greater participation and learning

is highly unlikely that international patents

and India—Some Thoughts’, paper pre

by doing by local firms in the host coun

can become any motivating force for Indian

sented at National Seminar, on Indian

tries".*6 Thus, it is clear that the flow of

R and D. On the other hand a global orien

Patent System and the Paris Convention

technology into India (or even into other

tation in R and D of several MNCs operating

Legal Perspectives, Delhi, 1986.

developing countries) is hardly influenced

in India do have an interest in international

5

Q H C Bodenhausen, “Guide to the Ap

today by patent restrictions and therefore,

plication of Paris Convention for the Pro

patent protection particularly since they also

it

may

at

best

be

an

alibi

to

seek

the

member

tection

of Industrial Property", .BI RPL

have live links with their parent companies

tent protection to pharmaceutical products

and some of them do not provide patent pro

tection even for processes used in produc

tion of pharmaceuticals. They include all the

leading pharmaceutical markets in the

developing countries, ranking among the 15

leading wo'-ld markets, c g, Brazil, Argentina,

Mexico, South Korea and India.23 I he dif

ferences in the approach of the developed

and developing countries (almost opposite)

arc clearly related to the differences in

economic and technological circumstances

prevailing in each group of countries. The

range of effects of patent protection in the

pharmaceutical sector clearly shows the

serious implications of the degree of protec

tion that is offered in these countries. It is

also for this reason that lobby of thepharma.'eutical MNCs is one of the most powerful

votaries of India joining the Paris Conven

tion and changirfg the present Patents Act.

Another argument, namely of getting bet

ter information (low due to joining of Paris

Convention is not true either since India even

now gets all the necessary information on

patents, including patents search through

WIPO, European Patent Office and Berne

convention membership. In fact, what is re

quired is the strengthening of the Nagpur

information centre as well as the creation of

more regional centres and following inter

national classification system in India.

14 64

in the west. While Indian subsidiaries of

MNCs may be benefited by joining Paris

Convention, it can hardly be a cause for pro

moting Indian R and D. On the contrary.

as discussed earlier, it may stifle Indian

R and D (and utilisation of its results) by

way of blocking patents which may become

easier as a consequence of joining the Paris

Convention. In fact, Indian manufacturers

can often be put to the disadvantage of not.

being allowed to manufacture or export

many products involving incremental

modifications in patents. For example, if wc

were a member of the Paris union, the Bajaj

auto factory (producing and exporting

scooters) would not only have been forced

to stop exports (and pay damages) but also

indigenous production of these scooters.

Economic and Political Weekly

August 22, 1987

6 Indus!rial Property, January 1987. pp 5-8.

UN Publication Sales No E75HDI and D-2

7 UNCTAD Report “Promotion of National

cited from A K Koul above

Scientific and Technological Capabilities

18 UNCTAD Conference oh an International

Code of Conduct on Thansfer of Tech

and Revision of the Patent System**.

nology. Genoa 1983.

TD/B/C6/AC2/2. July 1975.

19

P Banerjee, V B Lal and P Nath. “/Ar

8 Iqbal, T, 'International Patent System and

rangements for the Promotion of

India’s Econo mic/Tccbnicnl Co-operation

■’ • -! ’

- <. -n

. .

u

?.. / •

’

-I

Ccu.Anes U

.j ,

t -Zeby

of Scientific and Industrial Research (ac- .

N1STADS to WIPO, March 1987.

ceplcd for publication).

9 “Scientific Policy Resolution*', Gcr«rrruT.ent 20 N N Mehrotra, ‘Indian Science. What is

Wrong? What is Right?*, Bulletin of the

of India, 1958.

Association of Scientific Workers of India,

10 “Industrial Policy Resolution”, Government

1983, 13 (9), pp 133-140.

of India, 1956.

11 Dtnesh Abro! el al, “Scientific Pobcy Resolu 21 N Ray in “Management of Indian Science

for Development and Self-Reliance" Ed,

tion: A Different Perspective”, N1STADS,

N N Mehrotra ci al. Allied Publishers,

1985.

Delhi, 198?. pp 32 35.

12 V Rae Aiyagari and P J Lavakara, Depart

22 “Promotion and Encouragement of

ment of Science and Technology, J9SI.

Technological Innovation. A Selert-v*

13 •’Seventh Five Year Plan !9E5.«y\ Vol I.

Rrv-.jv. of Policies and Instruments’*.

Government of India, 1.13 to 1.16.

UNCTAD Report TD/B/C6/139 of 1986.

14 “Role of Patent System in the Transfer of

23 UNCTAD Report TD/B'C6/AC 53 of 1981,

Technology to Developing Counties",

P29.

UNCTAD, New York, 1975.

15 “RrvScv of Current Trends in Patents in 24 Ibid, p 23.

25

“Foreign Collaboration in Indian Industry”,

Developing Countries? UNCTAD. Geneva,,

Fourth Survey Report 1985, Reserve Bank

TD/B/C6/AC5/3 of 1981.

of India, Bombay.

16 A K Koul. ’UNCTAD Code on Transfer of

Technology 1985’, Foreign Trade Revur*\ 26 “Trends in International Transfer of

XX(2) pp 141-162.

Technology to Developing Countries by

17 “Major l«sues Arising from the Tr.nsfer of

Small- and Medium-sized Companies",

UNCTAD, TD/B/C6/138, 1986.

Technology to Developing Countries 1975“,

tourtRsy - Author

NATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON PATENT LAWS

OBJECTIVES

To discuss issues relavant and related to the Patent Laws

and Paris Convention ;

To arrange for research and publication of papers relating

to these issues ;

To help create a better understanding of these issues by

organising meetings, seminars and public debates ;

To represent to the Government and those concerned with