6149.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

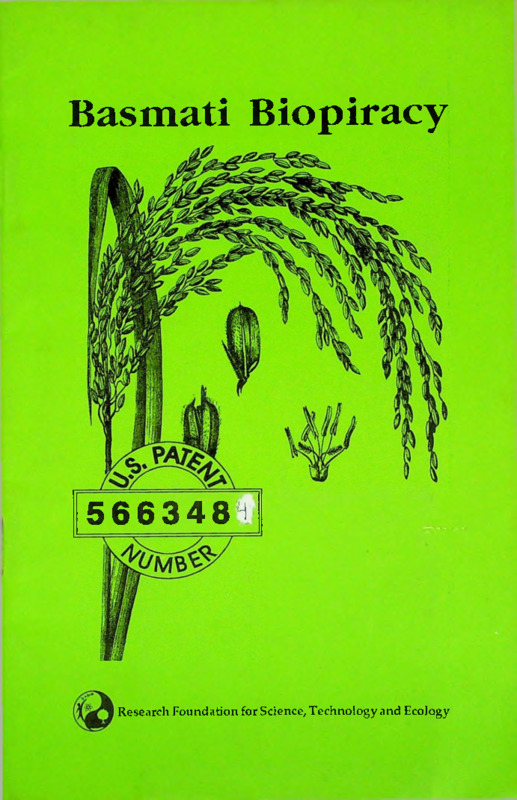

Basmati Biopiracy

566348H

Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology

CONTENTS

Page

1. Introduction

1

2. Basmati and Biodiversity

2

3. Basmati and the Indian Economy

4

4. RiceTec and the Patent on Basmati

5

5. Problems and Implications of Patenting Basmati 7

6. Biopiracy

11

7. What You Can Do / How You Can Help

13

- Consumer Action

- Advocacy Action at the National Level

16

- Advocacy Action at the International Level

19

8. Conclusion

21

INTRODUCTION

Rice forms an integral part of the life of most Indians. It

has been the principal crop in several regions of India

for thousands of years. India is the world's second

largest producer of rice after China. Rice is cultivated

in over forty-two million hectares of land in India. Over

90 percent of total world production of rice is in Asia of

which 21 percent is grown in India.

Apart from being the staple food of most Indians, rice

in India has been closely associated with religious

ceremonies and festivals since time immemorial. Each

traditional variety has its own religious or cultural

significance. The different varieties of rice, the use of

different rice preparations in rituals, and the medicinal

and therapeutic properties of rice have all been

documented in various ancient Indian texts and

scriptures.

India possesses a tremendous diversity in rice varieties,

reflecting the culmination of centuries of informal

breeding and evolution by farmers of this country. The

varietal diversity of rice in India can be considered to

be the richest in the world, with the total number of

varieties estimated to be around 200,000 (Krishan and

Ghosal :3:1995).

BASMATI AND BIODIVERSITY

Basmati (Oryza sativa) is one of the most superior

varieties of rice grown in the world. Indigenous to North

India and Pakistan, this rice variety is distinct for its

unique aroma and flavour, hence the Sanskrit name

"Basmati" which means "ingrained aroma" or "queen

of aroma."

Basmati has been grown for centuries in the

subcontinent as is evident from references in ancient

texts, folklore and poetry. One of the earliest references

to Basmati according to the CSS Haryana Agricultural

University, Hissar, is made in the famous epic of Heer

Ranjha, written by the poet Varis Shah in 1766. This

naturally perfumed variety of rice has always been

treasured and possessively guarded by nobles since

time immemorial, and eagerly coveted by foreigners .

Years of research on Basmati strains by Indian and

Pakistani farmers, has resulted in a diverse range of

Basmati varieties. The superior qualities of this rice

must be recognised as predominantly the contributions

of farmers' informal breeding and innovation. There are

twenty-seven distinct documented varieties of Basmati

grown in India.

2

WELL KNOWN INDIGENOUS VARIETIES OF

BASMATI GROWN IN INDIA

State of

Origin

Name of rice

Strain

District/

Location

Uttar Pradesh Basmati Dehra Dun

Garhwal

Basmati Safed

Garhwal

Lal Basmati

Garhwal

Basmati Basar (red)

Garhwal

Mota Basmati (scented)

Garhwal

Baunya Basmati

Garhwal

Deshi Basmati

Garhwal

Hansraj Basmati

Garhwal

Basmati Basar (white)

Garhwal

Basmati D-52-26-19

Garhwal

Pusa Basmati

Ramgarh

Basmati T3

Saharanpur Sela Basmati

Basmati Pilibit(N-lO-B)

X-T

Punjab

Basmati average

Basmati (P.2-33-14)

Basmati ( P.40-40-17)

Basmati 217

Basmati superior

Basmati 3

Sela Basmati 370

Basmati T.34

Basmati T.23

Punjab

Himachal

Pradesh

Basmati (K.33-39-5)

Basmati

Basmati

Kulu Valley

Haryana

Kamal Basmati

------------

3

BASMATI AND THE INDIAN ECONOMY

India grows 650,000 tonnes of Basmati annually.

Basmati covers 10 - 15 percent of the total land area

under rice cultivation in India.

Non-Basmati and Basmati rice is exported to more than

eighty countries across the world. Non-Basmati rice

exports in 1996-97 were 1.9 million tonnes and

amounted to Rs. 18 billion ($ 450 million), while Basmati

exports were 488,700 tonnes and fetched the exchequer

Rs. 11.2 billion ($280 million). Annual Basmati exports

are between 400,000 to 500,000 tonnes. Basmati rice has

been one of the fastest growing export items from India

in recent years. The main importers of Indian Basmati

are the Middle East (65% of Basmati exports), Europe

(20%) and USA (10-15%).

At $850 a tonne, Indian Basmati is the most expensive

rice being imported by the European Union (EU)

compared to $700 a tonne for Pakistani Basmati and

$500 a tonne for Thai fragrant rice. Indian Basmati

exports to the EU in 1996-97 amounted to nearly 100,000

tonnes.

Asians and Indians in Europe and the USA are the main

consumers of Indian Basmati rice.

RICETEC INC. AND THE PATENT ON

BASMATI RICE

RiceTec is a Transnational Corporation chaired by

Prince Hans-Adam II, the ruler of Liechtenstein. Its

American subsidiary, RiceTec Inc. employs one hundred

people and has an annual turnover of US $ 10 million.

On September 2,1997, the Texas based RiceTec Inc. was

granted patent number 566348^ on Basmati rice lines

and grains. RiceTec got patent rights on Basmati rice

and grains while already trading in its brand names

such as Kasmati, Texmati and Jasmati.

This patent will allow RiceTec Inc. to sell a "new"

variety of Basmati which it claims to have developed

under the name of Basmati, in the US and abroad.

The following abstract from Patent No. 5663484, issued

by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)

demonstrates what a broad patent it is.

" The invention relates to novel rice lines and to plants

and grains of these lines and to a method for breeding

these lines. The invention also relates to a novel meansfor

determining the cooking and starch properties ofrice grains

Specifically, one aspect of the invention relates to novel

rice lines 'whose plants are semi-dioarf in stature,

substantially photoperiod insensitive and high yielding,

and produce rice grains having characteristics similar

or superior to those of good quality Basmati rice. Another

aspect of the invention relates to novel rice grains

produced for novel rice lines. The invention provides a

method for breeding these novel rice lines. "

Patent Number. 5663484 not only defines the scope of

the patent, but also includes 19 distinct and separate

claims within this one patent.

The Basmati variety for which RiceTec has claimed a

patent has been derived from Indian Basmati crossed

with semi-dwarf varieties includingindica varieties. The

patent is thus for a variety that is essentially derived from

a farmers' variety. Therefore it cannot be treated as

novel. It falsely claims a derivation as an invention.

The RiceTec's claim states that:

"Although the invention is described in detail with

reference to specific embodiments thereof, it will be

understood that variations which are "functionally

equivalent" are within the scope of this invention.

Indeed, various modifications of the invention in addition

to those shown and described herein will become apparent

to those skilled in the art from the foregoing description

and accompanying drazoings. Such modifications

are extended to fall within the scope of the

6

PROBLEMS WITH THE RICETEC PATENT ON

BASMATI RICE

1. Though the patent is for a particular variety of

Basmati rice, the clause "functional equivalents"

in the claim has widespread implications and could

be used against all traditional varieties of Basmati

(A and B in the diagram). This could severely harm

Indian Basmati growers.

traditional Basmati (farmers' variety)

A

_________________ C

Basmati 867

(patented by RiceTec)

semi-dwarf variety

2. A patent can only be issued if it meets the three

criteria of novelty, non-obviousness and utility.

Novelty implies that the innovation must be new. It

must not be part of "prior art" or existing knowledge.

Non-obviousness implies that someone familiar in

the art should not be able to achieve the same step.

The development of the 'new' variety (Basmati 867)

by RiceTec has been derived from Indian Basmati

through conventional breedi

techniques. The claims of "novelty'

and "invention" are therefore

false.

3. Iridian law forbids the patenting

of any life forms unlike US law.

7

4. The gene bank of the International Rice Research

Institute (IRRI) is maintained by the CGIAR

(Consultative Group on International Agricultural

Research), which now has an agreement with the

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) of the UN.

None of the varieties held in this gene bank can be

patented. Since RiceTec used the Indian Basmati

strain from this bank, its product cannot be patented

under the terms of the agreement of which both the

US and India are members.

5. The name "Basmati" is not a generic one as RiceTec

claims, but is distinctive of the rice grown in the

Indian subcontinent. Just as champagne is unique

to France, Basmati is unique to India and Pakistan.

The RiceTec patent is for a rice variety grown under

different climatic and soil conditions, and called

Basmati. This should be against the Trade Related

Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) of the World

Trade Organisation (WTO), which is supposed to

protect geographic appellations.

The patent is thus a serious threat to our culture, science

and heritage, and needs to be revoked.

Legal Implications :

If Indian patent laws were in conjunction with US patent

laws, then patents like RiceTec would be applicable in

India. This is precisely what the TRIPs dispute

initiated by the US in the WTO aims at

achieving by 1999.

8

• If the US pressure forces India to implement US style

patent laws, RiceTec would have the sole right to

use the term 'Basmati' for marketing the rice

anywhere in the world.

• US case law is already establishing that once a

patent law is granted for a genetic trait (in this case

aroma), all occurrences of that trait will be an

infringement, irrespective of how they came to exist

(Shiva Vandana: 1998). This could lead to the absurd

situation in which RiceTec could claim that Indian

farmers growing Basmati were "infringing" on the

RiceTec patent.

Economic Costs to India:

o Though there is no way that Indian exporters and

growers can be prevented from conducting their

normal activities of trade, the patent will affect

exports of Basmati rice to the US by allowing the

marketing of a "pseudo Basmati" as Basmati. About

45,000 tonnes of Basmati are exported annually to

the US. The loss of these exports will have an adverse

effect on Indian exporters.

Exports to the Middle East and the EU might also

suffer as RiceTec could capture these markets with

its fake Basmati. These are non-competitive trade

barriers that would harm Indian exports.

"In the long run, India will have

severe problems in positioning

its exports", says Mr. Gurnam

Arora, President, All India

Rice Exporters Association

(AIRE A).

9

‘ r met r»:

• <•

\ aw. -• a direct appropriation of traditional

x ,xcc oi Indian l.innrrs. It reduces years of

o • • .esoatvh breeding and innovation to a

? ■ \v, .'.AU'A't patent.

\

71

•/ .went claim is interpreted to apply to ali

n:-u ;:;‘s of Basmati which were used to

.n c cp : patented variety (Basmati 867), Indian

r a Pakistani farmers could be forced to pay

:s ?o RiceTec Inc. for the use of their own seeds

II

Pl' c avehhood of 250.000 farmers growing Basmati

~ hia and Pakistan could be jeopardised by the

-~=r barriers this patent would establish.

The parent on Basmati 867 is an outright violation

hr—ars ethics, which respect agriculture and all

_ra ark condemn its patenting in any form.

H>

B I 0 F I K A C Y

What is biopiracy ?

The appropriation of indigenous knowledge by

obtaining patents on biodiversity resources in the

developing world is known as biopiracy. Years of

indigenous research and development, are reduced to

a mere product. The patenting of Basmati by RiceTec

Inc. is a classic example of biopiracy, and is part of the

norm rather than an exception. The main reason for

developing this Basmati Campaign Kit is because

biopiracy is taking the dimension of an epidemic all

over the world.

Why it needs to be stopped :

According to Dr. Vandana Shiva, biopiracy results in

the following:

1. It creates a false claim to novelty and invention, even

though the knowledge has evolved from ancient

times as part of the cultural and intellectual heritage

of the developing world.

2. It divests biological resources (germplasm) to the

monopoly control of corporations, thus depriving

local communities from the benefits of its use.

3. It creates market monopolies

and excludes the original

innovators (farmers) from

their rightful access to

local, national and global

markets.

11

The Basmati patent, a clear case of biopiracy, represents

a theft in three ways:

1. It is a theft of collective intellectual and biodiversity

heritage of Indian farmers who had evolved and bred

the Basmati varieties.

2. It is a theft from Indian traders and exporters whose

markets are being stolen by the theft of Indian

aromatic rice varieties. It is a theft of the name

"Basmati" which describes the aromatic

characteristics of the rice.

3. It involves a deception of consumers since RiceTec

Inc. is using the stolen name "Basmati" for rice

derived from Indian rice but not grown in India and

therefore not of the same quality.

Countries like the US vindicate developing nations of

pirating information from them, however, the UNDP

estimates that biological resources worth approximately

US$ 5.4 billion are stolen by the rich industrialised

countries from Third World nations every year. The US

alone accounts for nearly 60 percent of this 'loot.'

The issue of biopiracy is a very serious one. In order to

rectify the problem, a number of efforts have to be made

at both the international and national levels. Strong

legislation coupled with a commitment towards equity

are the prerequisites for any solution to be feasible in

reality.

12

WHAT YOU CAN DO /

HOW YOU CAN HELP

CONSUMER ACTION:

• Support Third World movements like 'Navdanya'

which strive to protect the farmer's right to produce

and conserve seeds. Such movements are needed

to ensure that Indian farmers continue to produce

Basmati rice. By protecting indigenous production

of Basmati rice, farmers' livelihoods and

contributions will not be lost to First World piracy.

• Urge consumers, non resident Asians and Indians

to consume only Indian and Pakistani Basmati rice.

• Boycott/afce American Basmati

• Launch a campaign to inform people of the superior

qualities of Indian Basmati rice. Advertise it as the

"real thing."

• Label Indian Basmati as "patent-free ", similar to

the way in which tuna from the US was labelled

"dolphin safe tuna" to discriminate it from Mexican

tuna, and sugar was earlier labelled "slave free."

• Use media - television, student radio, newspapers

to reach out to people and generate

awareness about the piracy of

Basmati and its implications on

Indian farmers and the Indian

iiAw,n v.

economy.

F

*

13

• Design stickers, labels and posters for cars,

supermarkets and stores.

Some samples which could be used

only

'KEAC BASMATIJ at

SUPPORT

IN1DJAK1 FARMERS

14

• Write letters to the Indian government expressing

your support on the move to revoke the Basmati

patent. Urge them to resist WTO pressure to change

patent laws.

Minister

Ministry of Agriculture

Krishi Bhavan

Dr. Rajandra Prasad Road

New Delhi -110 001

INDIA

• Write letters to the USDA (US Department of

Agriculture) and USPTO (US Patent and Trademark

Office), condemning biopiracy in general, and the

patenting of Basmati in particular. Urge them to

enforce legislation that promotes equity between the

North and South, and to take measures to stop the

practice of biopiracy. The US should be pressurised

to amend its patent laws while recognising the

needs and problems of developing nations, instead

of taking advantage of them.

Contacts:

USDA

USPTO

Dan Glickman

Secretary, Agriculture

200-A Whitten Building,

Washington DC 20250.

USA.

E-mail: agsec@usda.gov

The USPTO

Box 4

Commissioner of Patents

and Trademarks,

Washington DC 20231.

USA

15

ADVOCACY ACTION AT THE NATIONAL

LEVEL

1) Establish “sui generis” systems

Article 27(3) of the TRIPs states that, "parties shall provide

for the protection of plant varieties either by patents or by an

effective sui generis system or by any combination thereof"

"Sui generis" means self generated. National

governments should develop systems to suit their own

cultural and intellectual needs. In countries like India,

80% of the seeds still used are farmers' varieties. Hence

such sui generis legislation should recognise the

collective rights of farmers, and should therefore be an

alternative to the western, industrial style Intellectual

Property Right (IPR) regimes. Legislation should be

passed which sets up mechanisms to enforce these

ideals and ensure that indigenous knowledge holders

are not victimised.

2) Farmers’ Rights Law

Farmers' Rights are the only means to assert our national

sovereign rights to our indigenous innovation. This

indigenous innovation is based on collective,

cumulative processes, and hence on collective

intellectual rights. Since the only way to prevent

biopiracy of our agricultural biodiversity is

by preventing the patenting of varieties

\

derived from them, we need to

•

develop a strong legal system of

T 1

Farmers' Rights for protection of

x

farmers' varieties.

16

3) National Biodiversity Act

The Indian government should develop and enforce a

National Biodiversity Act which builds on the principles

of sovereignty and protection of indigenous knowledge

as stressed by the Convention on Biological Diversity

(CBD). The principle of sovereignty should be based

on co-ownership of biodiversity by local communities,

and the nation as a whole. The State should hold

biodiversity in public trust for the people of India but

not interfere in their daily lives, nor police them in their

utilisation of biodiversity for survival. The drafts of the

Act must be revised to prevent free access of

bioprospectors whose primary motive is profit.

Once this legislation comes into place, India can take

foreign companies to court under the CBD, which

confers biodiversity ownership rights to national

governments.

4) National Patent Laws

There is an impending need to strengthen Indian patent

laws, which do not have any provisions to combat

biopiracy. All life forms should be exempt from

patenting. India should not yield to US pressure to

change laws according to their demands. We must be

assertive and develop systems, which safeguard our

ethical and cultural values. Articles 27.2 and 27.3

of the TRIPs that specify exclusions to

patenting of life forms should be

stressed while formulating strong

tjk j

domestic legislation.

17

5) Non co-operation : Seed Satyagraha

The motto of the Swadeshi Satyagraha launched by

Gandhiji during the freedom struggle was 'non co

operation with the British.' In case none of the above

legal alternatives to prevent biopiracy work, the Seed

Satyagraha, should be launched, which proclaims: 'non

co-operation with IPR regimes and Transnational

Corporations aimed at plundering Third World

biodiversity.'

s.o.s.

Save Our.

Seeds !

18

ADVOCACY ACTION AT THE

INTERNATIONAL LEVEL

1) TRIPs and Intellectual Property Right (IPR)

Regimes of the WTO

The problem of biopiracy is not merely national, but

has international origins too. The loopholes in

international agreements, and their distinct bias towards

the developed nations, facilitate the marginalisation of

the Third World.

The TRIPs of the WTO are aimed at facilitating free trade,

regardless of its costs to humanity. Under the garb of

promoting free trade, developed countries get away with

a number of atrocities against the developing nations.

Such free trade treaties thus significantly discriminate

against poor countries. The TRIPs regime calls for a

system of uniform patent laws by 1999, discounting the

differences in ethics and value systems of Third World

nations, where life is sacred and exempt from patenting.

The TRIPs agreement has provisions for "effective sui

generis systems" as an alternative to patents. Since

these systems are not defined, developing nations

should be free to interpret them as indigenous methods

of protection of plant variety.

A uniform IPR regime, which the WTO would

like to establish, would exclude the

freedom of farmers to freely exchange

and grow seeds. The WTO needs to

be amended in order to eliminate

the prejudice against holders of

indigenous knowledge.

19

,

w

>

(

2) The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

The CBD is an international treaty which aims at

protecting biodiversity, recognising sovereignty of

nations, and promoting equity. It came into force in

1992 at the Earth Summit at Rio. It is legally binding

on all signatories. Measures should be taken by all

contracting parties to uphold the principles

embodied in this treaty. The CBD should supersede

all trade treaties with the goal of protecting human

health and the environment. The true purpose of the

CBD needs to be recognised. National diversity laws

of some countries have, under pressure from the

developed world, become mere access laws, which

promote their access to biodiversity of the Third

World. The CBD was developed to protect the

biodiversity in the Third World, and should be used

effectively to counter appropriation of biological

resources.

3) FAO International Undertaking on Plant

Genetic Resources (March 198>7)

This undertaking is an initiative of the FAO to safeguard

plant varieties and the rights of farmers. It defines

Farmers' Rights as "rights arising from the past, present

and future contributions of farmers in conserving,

improving and making available Plant Genetic

Resources, particularly those in the centres of

origin and diversity."

bL « '•

d’

\

Attempts should be made to uphold the

principles of this undertaking and to

establish legal mechanisms to

safeguard the rights of farmers.

20

4) US Patent Act

There are certain distortions in the US law which

facilitate the patenting process for companies. One such

distortion is the interpretation of 'prior art.' It permits

patents to be filed on discoveries in the US, despite the

fact that identical ones may already be existing and in

use, in other parts of the world. Section 102 of the US

Patent law does not state a general definition of 'prior

art' but a very narrow rule bound method to be used

by low level patent examiners to determine which

materials will defeat a patent application by violation

of the novelty and non-obviousness criteria.

Prior foreign knowledge, use, and invention are all

excluded from the 'prior art' related to US patent

applications. Unless Section 102 of the US patent law is

amended, new examples of biopiracy will continue to

occur.

CONCLUSION

Basmati is just one example of the increasing number

of biopiracy cases in India. As responsible citizens, it is

our duty to act, speak up and initiate change. We must

strive to prevent further human rights violations of this

nature. It is time to wake up and take action, or else the

silent majority will soon be reduced to the silenced

majority.

References:

-

RFSTE, Dossier on Patenting of Basmati by RiceTec Inc., 1998.

-

Krishnan Omkar, Ghosal Anjali, Rice, Navdanya, 1995.

Shiva Vandana, Biopiracy, 1997.

21

<SI - / F 0

y

<

and

i

<

uNH

> > ■ y.

; r- ;

0814S. ( ( ooCUM^'TATtON ; .

_________________

"The Basmati patent once again makes clear

that the US patent system facilitates biopiracy

and the WTO protects this biopiracy."

Dr. Vandana Shiva, Director, RFSTE.

"The tussle is not just between Basmati and Rice

Tec Inc. It is between globalisation and national

sovereignty. And it is a much bigger issue than

we think, and basically a political rather than

economic issue."

Jai Dubashi

Economist

"We really do not know how many of our filly

developed hybrids and quality seeds are being

utilised now by other countries."

Dr. Mangala Rai, Deputy Director-General,

Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR).

"If both product and process patents are

introduced in agriculture', it will mean a

scientific apartheid for the Third World.

Dr. Ismail Serageldin, Chairman, CGIAR.

Position: 869 (9 views)