SDA-RF-CH-4.1.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

'■

SDA-RF-CH-4.1

'J

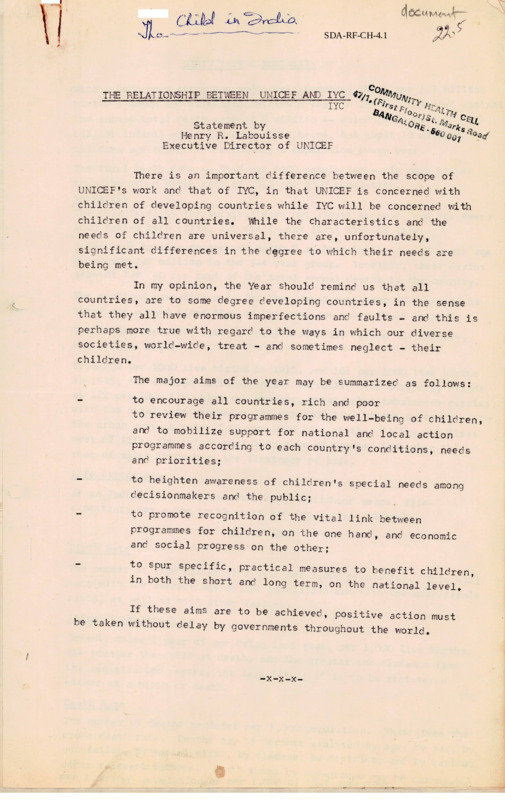

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

UNICEF AND IYC

Statement by

Henry R. Labouisse

Executive Director of UNICEF

•

There is an important difference between the scope of

UNICEF’s work and that of IYC, in that UNICEF is concerned with

children of developing countries while IYC will be concerned with

children of all countries. While the characteristics and the

needs of children are universal, there are, unfortunately,

significant differences in the dggree to which their needs are

being met.

In my opinion, the Year should remind us that all

countries, are to some degree developing countries, in the sense

that they all have enormous imperfections and faults - and this is

perhaps more true with regard to the ways in which our diverse

societies, world-wide, treat - and sometimes neglect - their

children.

The major aims of the year may be summarized as follows:

to encourage all countries, rich and poor

to review their programmes for the well-being of children,

and to mobilize support for national and local action

programmes according to each country's conditions, needs

and priorities;

to heighten awareness of children's special needs among

decisionmakers and the public;

to promote recognition of the vital link between

programmes for children, on the one hand, and economic

and social progress on the other;

to spur specific, practical measures to benefit children,

in both the short and long term, on the national level*

If these aims (are to be achieved, positive action must

be taken without delay by/ governments

throughout the world.

/

-x-x-x-

0

2

The child shall have full opportunity for play and recreation,

which should.be directed to the same purpose as education; society

and the public authorities shall endeavour to promote the enjoyment

of this right.

Principle 8

THE Child shall in all circumstances be among the first to receive

protection and relief.

Principle 9

THE CHILD shall be protected against all forms of neolect

cruelty and exploitation. He shall not be the subject of’traffic

in any form.

yxauxu,

J

Principle 10

ZoriS1110 f?3*1 be Protected from practices which may foster

be brough? ^1inEspiritnof°i!;derSrnriif

tScfiraination- He shall

c^n^iSusKi^’t^rhir5 uni"e^?bro^erho^ raa^eInfSlindShip

se^ic1?UofTis^ll^mln*197

tal<?ntS sh°uld be devoted to the

RIGHTS OF CHILDREN

A. Constitutional Frovisions

!• Fundamental Rights

Article 15 (3)

The State may make any special provision for (women and) children

in regard to ]prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion,

race, caste, sex or place of birth.

Article 24

Prohibition of the employment of children in factories, mi nes

or hazardous employment below the age of 14 years.

2. Directive Principles

Article 39(e) and (f)

The State must direct its policy towards securing ’inter-alia *

economic necessity to enter

vocations unsuited to their age and strength and that childhood and

yout are protected against exploitation and against moral and

material abandonment.

i

that children are not

+V.-.+

forcec3

~

• »vr"

jj

v 14

i iv

i. i 4

V/

11

JL L" I

Article 45

The State, must endeavour to provide free <anc’ compulsory education

for all children until they complete 14I’ years of age*

B. The National Policy for Children, 1974

SXh^e°

^=lesl, cental

1. A comprehensive health programme for all children.

fOr ChU<llen “ith

anf’

tj"

preschool children.

“Meet of

education

for

->hilSnSotaf9?ha:10"

ision of informal education for

5. Out of school education for children who do not have

access to

formal education in schools.

oi KSatiSnal

spjrts and other types

schools, community centres and other suc^inSl^Uons^ 111'8 in

pct^r^^'o^nHy^L^Sle^1:.^."? to economically weaker

equality of opportunity.

ecu^o castes, and tribes, to ensure

who have'become°delinquents ’ o^hPP^f

rehabilitation ‘

for children

otherwise in distress? 0 S* °r been forcec' to take to begging

I or are

9. Protection of children

against neglect, cruelty anc’ exploitation.

... 2

2

1O» Banning of employment in hazardous occupations 4nd in heavy

work for all children under 14.

,11. Provision of facilities for special treatment, edudation,

rehabilitation and care of physically handicapped, emotionally

disturbed or mentally retarded children.

12. Priority for the protection and relief Bifxh children in times

of distress and national calamity.

J’u* Special Programmes to spot, encourage and assist fis <fiifted

children, particularly those belonging to weaker sections of the

community.

14. Amendment of existing laws so that in all legal disputes,

the interests of children are given paramount consideration.

neighbourhood, and community environment.

LEGISLATION

Legislative support for child welfare services in India is found in

the Children Acts of the various States. These laws have a special

relevance to the protection and rehabilitation of socially handi

capped children such as neglected, destitute, victimised,

delinquent and exploited children.

The biggest drawback of the Children Acts is that the ’child’ is

defined differently from State to State. In Madhya Pradesh,

Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, a child means a person under 16 years,

in Saurashtra and West Bengal a person under 18 years, in

Telengana a person under 16 years, and in the rest of Andhra Pradesh

a person under 14 years. In the Union Territories, a child is

defined as a boy under 16 years or a girl under 18 years. As

inter—State movement of exploited children cannot be prevented,

these laws are not as effective as they could have been.

Some States, like Nagaland, Orissa, Sikkim and Tripura, have yet

to enact any children *s legislation. The Union Territories of

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, Dadra

and Nagar Haveli, Lakshadweep and Mizoram have no institutional

arrangements yet to apply the Children Act of I960.

Protecting the Working Child

The main thrust of the Indian laws concerning child labour has been

on the minimum age of employment, medical examination of children

and prohibition of night work. In each of these directions, the

standards stipulated are below the international levels laid down

by the International Labour Organisation. Enforcement of the law is

renderee difficult by a combination of factors: economic back

wardness forcing the family to supplement its income by letting the

children work; lack of educational facilities; the unorganised

nature of a good part of the economy; and the smallness of most

manufacturing units.

Minimum Age

A major deficiency in the protective legislation is the fact that

thouoh1f+n?c1+hcflX^n9 a mirilmurn.a9e for employment in agriculture,

?aln occuPa'tlon m the country and the bulk of

1

chile.labour, 78.' per cent of it, is engaged in this occupation.

A minimumage has been fixed however at 12 years for plantations

14 years in factories and 12-14 years in the case of non-industrial em

®u\thls

th' unregula?"d: foj

aCt itsclf applies only to factories employing

worKers above a minimum number.

x

Medical Fitness

As ior

for legal safeguards for the health of child workers, the law

AS

-.I... of children upto 18 years of age and that

r$xamination

for industrial employment

only,

too

for

for medical

medical fitn;s"s:-'^

fitness. ;...J “ib«;"irnoBi^n?„SrX"?So?rJeJ?cid1do'’n

examination of children working in theJ non-industrial sector.

Adoption of Children

The Adoption of Children Bill 1

in Parliament in 1972.

is to provide

but has yet to be enacted. Itswasaimintroduced

,

.

an enabling law for

H —' destitut*.

all Indians seeking to adopt

neglected

a^one5'-.

and orphaned children in the country. This was’in

pursuance

of the

Directive principle in the Constitution u

preventing

the

and

moral

of

material abandonment of children (ArticleJ 39 f).

...2

2

The existing Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act covers only that

community.

Child Marriage

Throughout the 50 years of its existence, the Sharda Act (The Child

Marriage Restraint Act) has been an ineffective legislative

showpiece. Although it was meant to prohibit child marriage

altogether, the question of validity of a child marriage solemnised

in violation of the statutory age requirements remained outside

its scope.

The Child Marriage Restraint Amendment Act 1978 raises the minimum

age of marriage from 18 to 21 for boys and 15 to 18 for girls

Even with this amendment, the violation of the law would not

affect the validity of the marriage once it has been conducted

tout only entail penal consequences. Offences under the Sharda Act

have now become cognizable and even Muslim, Parsi and Jewish

communities come within its purview even though it does not affect

their personal laws. Parental consent no longer exempts a child

marriage from the provisions of the amended law. This was a

loophole in the original law.

Experience shows that legal changes may not cause marriages to be

delayer, unless constructive opportunities are provided to the youno

permissibleSlgearria9GS

S0Ught t0 be PostPoned till the legally

CHILDREN IN NEED OF DAY-CARE

Many of India ’s children are neglected during early childhood for

lack of day-care services. Shortage of such services often pulls

an older sister out of school to shoulder the task, or forces a

working mother to take small children to work sites, where they face

added hazards.

The 1971 Census lists 16.6 million rural children and 2 million

urban children less than 6 years old, whose mothers are workers.

c’ata also lists 31 million women workers, of whom about

20 million belong to the most needy sections of society. About

94 per cerrt of women labourers work in the unorganised sector

where employers do not provide any services for their children.

Day-care facilities for the children of these working mothers remain

a major unmet need.

What the Law Says

The law does provide for day-care services for children of certain

categories of women workers, but many employers do not fulfil leaal

obligations. Women working in the unorganised sector, or in small

establishments are not covered by such provisions. Nor are women

as clerks, teachers, nurses, and similar lower-level white collar

employees•

Under the Contract Labour Regulation and Abolition Act of 1970

a contractor must provide a creche wherever 20 or more women are

employed as contract labour. This is seldom done.

Under the Factories Act (Section 48), every factory ordinarilv

+0.or mora Woraeh workers has been obliged to provide and

mewtx maintain creches for children under 6 years old

St this

violate^ aS In ?973 th£e wre

f '

J101 ?

only 901 factories in the country providing this facility

With

nhMnn+?rCeKen^K°^ th6 factories (Amenrment) Act of 1976* the

Oo“a^o"rk:S.eXtenC'eC' “ every

The Plantation Labour Act of 1951 stinula+oe

stipulates +h-.+

that ~

a of these

??e"?re Strict

s

enforcement

j are <

scope of these laws.

* + + *

i

•

JUVENILE DELINQUENCY

Juvenile crime accounts for 3.4 per cent of all cognizable crime

in India. Its rate is estimated to be 6.4 per 100,000 population.

Contributing Factors

There seems to be a strong relationship between poverty anc1 the

incidence of juvenile crime. It is found that the lower the

income of the family, the higher the incidence of juvenile crime.

Among the children arrested for crimes under the Indian Penal

Code, it was found that 83 per cent belonged to families where the

joint income of parents and guardians was less than Rs.150 per

n°n^nA

per cent of families whose income was between Rs.150 and

Rs.499 per month; 3.12 per cent to families whose income was

between Rs.500 and Rs.1000 per month and 0.36 per cent to families

whose income was above Rs.1000 per month.

Among the children apprehended, it was found that 48 per cent were

illiterate, 34.6 per cent were below the primary level of

schooling and 11.5 per cent were above the primary but below the

higher secondary level.

Pattern of Crime

Among the crimes committed by juvenile delinquents are murder,

kidnapping, abduction, dacoity, robbery, burglary, theft, riot,

criminal breach of trust and cheating. The largest percentaoe of

andGtheGTndt mGSRfM1 und®r+the Gambling Act, the Prohibition9Act

anc rpe Indian Railways Act.

The Spread

About 30 per cent of juvenile crime was reported in Maharashtra,

followed by 18 per cent in Gujarat, 16 per cent in Tamil Nadu and

11.5 per cent in Madhya Pradesh.

Among the children apprehended, it was found that 17 per cent had

been apprehended for repeated crimes.

Enforcement of Laws

Most of the Children Acts have a clause for providing a 'place of

safety' where child offenders can be kept in custody separately

from the adult offenders. LDespite this, it is estimated that in

the various States and Union

.--.I Territories of India, there are

10,000 children under 16 years of age confined to prisons along

with adult offenders.

m?st St?teE f'oe, not mention anythino

etention for long periods without being brought before a Magistrate.

# * #

WORKING CHILDREN

Lack of data makes it difficult to arrive at a reliable figure of

the number of children pushed into the labour force by economic

pressures. The 1971 Census listed 10»7 million children as workers*

but estimates incicate that the total child labour force may be as

high as 30 million.

If it is assumed that 5 to 10 per cent of India’s children are

working, India has the largest number of children workers in the

world. These children constitute about 6 per cent of the total

labour force m the country.

Of the 10.7.million children classified as workers in 1971 Census

data, 7.9 million were boys and 2.8 million girls. This data does

not seem to adequately refledt the role of girls in the familv-blsed

economy. The proportion of girls to female9adult workers hasbeen

Su

Per Cent hi9her

the P-P»rUo”o?aLyb:etno

Where they work

farmGrelated1workb°orGrn +hfk?

The I?aj?rity are in agriculture or

sector of th'e^co^0^ ln

’^l^SosFwSing^n^he^ganised0"

£er C<?nt are in

manufacturing and processing iobs a nd

hold and other industries wi+h+1^2 another 6 per cent in house

rGSt engai9ed in trade, commerce,

transport and sb storage.’

2flectedri°fCe““rdatr^Yr''

Jh\u™r9anlsed sector is „ot

accounts for children working as domc.+f guessec* at* This sector

hotels, restaurants

2

domestic servants, helpers in

hawkers, newspaoer Vendors , "porters shoe°?hine%Similar establishments;

and unloading goods. Their hours of^nrk 10 bfGaklng stones, loading

and uncertain, their workino and

k 5?xlong’ their wa9es low

1Vlng c°ndltl°ns bad. They are at

the mercy of their employe??.

Where They Come From

toCrSigar?asbG ThZy co^s^iS??^^

c!nt of

belong

areas ?on?titit?*1.8hpeJ c^nt^thl Sf1! WOukers/ounAnrii?bin

Places the in?id^c of chfld^At0 child Potion.

o ld labour as highest in

Andhra Pradesh, which accounts for

child labour rirce, and "S ceS of

°,f ?dla ’=

The next highest recorded incidence is’in gdhSa^d^ a^issa.

early e"1Pl°Y"»nt , - - Dat5UClidlcates1thateasSn>anveas°Sa9e

•

------ 1 seems to

ipricates that as

a<a

of Children.

are workers. This

fou? times

is four

^imes^he/th1 °+fHthe ^i^^en

of

This is

migrants

populations.

er

the rate among settled

.. ..2

2

What It feans

Child labour deprives children of educational opportunities,

minimises their chances for vocational training, hampers their

intellectual development and by forcing them into the army of

unskilled labourers, condemns them to low wages all their lives.

It is estimated that if workers under 18 years of age in India

could be taken out of the labour force and provided education and

vocational training, some 15 to 20 million unemployed adults

would be able to find jobs on standard wages.

Exploitation

Existing legislation covering child workers in factories and

establishments is not being adequately enforced. There are also

areas where no legislative coverage exists, and others where the

laws themselves permit early childhood employment*

@ @ @

THE DEPRIVED CHILD

The Submerged Segment

An estimated 46 per cent of the population live below the poverty

line - 48 per cent in the rural areas and 41 per cent in the urban

areas. This means that approximately 108 million children live

in varying degrees of destitution, 90.5 million of them in the

villages ans 17.4 million in the towns.

The Depressed Classes

There is a predictable overlapping of the child population livina

in poverty and that belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

The vast majority of children belonging to the Scheduled Castes

Srh^„?b5rpe? CGnt

total child Population belongs to the

,Among the 33.5 million Scheduled

CastP

StiiL hiJdIu ’ 29,6 million live in the rural areas, and 14.8

thG^G-i5rG beiow 6 years of age. All but 500,000 of the

Tso

7579miliiAnnofh+idrGn °f ^^uled Tribes live in rural areas, and

7.7 million of them are under 6 years old.

Destitute and Vagrant Children

thJ

nuKJ'for

Karnataka and Orrissa have the next largest incidence of beaaarv

indiaaDushedri +^\1S like|Y that the actual number of child?enYln

in beggar Colonies, where kidnapped waifs^0^0™6* expl°Ration

strays are maimed and

multilated and forced to b^

& »

beggar barons.

9* ThGlr Garnings go to the so-called

2Throw-away * Babies

born'eve^y^ear befo™’’■Xo^^ay'"babllr' T 2*

21 n,illion

birth due to various social and pLnnm^!’ abandoned soon after

estimates place the number of destitute0 pre®surGS’ Social Workers'

children at between one and f-ivoSrJ^UtG ’ orPhanec? ancJ abandoned

reflecting the greater value

’

Children of Migrants

placebo plac^i^sea^ch^^wSrk^15^^6 |!bourers moving from

casual daily wages or short-term* seasonal^mni managG to get more than

the Census listed 4.2 million rhfld™« £!? employment.

In 1971,

place of

Of 't*h©c;ci *5 q

“

chi1^" — £ thfe°rrix :rh:ansr:rex-- aillion

Protecteda>«ater”sJjplyJ1XlthJutUproDernho 1?ve1- ThGV do without

services, and are often outsiHc PfoperJ?ousing, sanitation or sewaoe

G radlUS of medical and schooling

facilities. Migrants® ch?£»

?TSet’ t0

“r

9

disability,

existence. Formal education

barely flgures in Seir Uves

..2

2

Both boys and girls of migrant families take up petty jobs to

add to the meagre family earnings. An urban study showed that

while about 19 per cent of the children of settled city-dwellers’

were workers, child labour among migrant children was as high

as 80 per cent. There is no comparable data available on the

labour rate among children of rural migrants.

ftoor nutrition, low resistance to disease and insanitary conditions

nLt0 uPdermlne the physical status of the migrant child.

While the urban infant mortality rate is otherwise 83 per

sof”6 urban slums and migrant settlements it is as hioh

y

as 140 per 1000.

-x-x-x-

HANDICAPPED CHILDREN

Four major disabilities afflict at least three million children

in the country. Estimates list 2 million mentally retarded,

800,000 blind, 500,000 orthopaedically handicapped and 200,000 deaf

children.

These modest estimates do not include the large number of children

who are marginally or mildly handicapped. While about 12,000 to

14,000 children go blind every year due to Vitamin A deficiency,

about 10 to 15 per cent of all children suffer from night blindness.

Available data does not give a clear picture of the actual

incidence of these and other handicaps.

\

Services and facilities for the education, training and rehabilitation

of handicapped children are grossly inadequate. Existing services

cater to only 4 per cent of the physically handicapped, 2 per cent of

the blind, 2 percent of the deaf and barely 0.2 per cent of the known

mentally retarded child population. There are only 800 voluntary

organisations and State institutions offering educational and

training facilities to about 30,000 handicapped children.

Prevailing social attitudes towards mental and physical handicaps

are an additional problem for the handicapped child.

EDU CATION

A Directive Principle of the Indian Constitution (Article 45) lays

down that the State shall endeavour to provide free and compulsory

education for all children until they complete 14 years of age.

This was to have been achieved within a decade, but has not been

realised so far.

The progress has been uneven from State to State, as between the

urban and rural areas and as between boys and girls.» For example,

example

all urabin areas have facilities for elementary and middle school

education. In rural areas, 80 per cent of the habitations have a

primary school within 1.5 km and over 60 per cent of the habitations

have a micdle school within 3 km. Out of a total of 575,926 villages

m the country, it is estimated that about 48,566 are not served

by any school at all.

Education is free for all children upto the secondary stage in 12

States and Union Territories. In 8 other States and Union

Territories, it is free for all children upto the middle school stage.

Another 8 States offer free edudation*formal! children^uptothe

micole school stage, and upto a few more years only for girls. Two

States offer free education for all children upto the primary school

level ano one of them offers an additional few years of free

education for girls.

School Enrolment

Approximately 4.5 million children are being offered one kind of pre

‘

“

primary programme or the other. “These

barely 5 per cent of the

form

population m the 3-6 years age group and are mainly from the

better-off sections of^society.

Enrolment in schools has been slower than expected. Only 80.9 per

children m the 6-11 years age group, 37.0 per cent in the

11^14 years age group and 20.9 per cent children in the 14-17 years

age group are enrolled in schools. The enrolment level for girls

If

han that fOr ^°ys- W1116 the enrolment of boys

6-11

it is onlv g^oup,

of

the

years

is 97.5 perthecent,

per cent for girls age

of group

thatgroup.

Jllwyearrage

9zi%e^rOlrnGn+ of

Per cent, but that of girls is only

is

?fz5i7eroCenV -lu6

«^ens further at the high school level Y

b°YS at 28-3 per Cent and that

of

Drop-Out Rates

The school enrolment figures provide only

education, another being the rate of dropping out^o^echojl”" 'S

SassV^^oi?? 24hie1^mehOclast:rVSrS Jhe^p^t" ££ Cf°'"Plete

a reuaJhhc?a:rv.OfT^::y7j%?^’t*?

leave school without attaining functional literacy!

ci t

9

V?1*

enrolled

HEALTH

Children in India face many health hazards, and many die young

for lack of timely health care.

Forty per cent of all deaths in India occur among children below

5 years of age. Of these deaths, about half are of children less

than a year old.

In the lowest age group (0-12 months), 50 per cent of deaths are due

to dysentery, diarrhoea, respiratory diseases and gastro-intestinal

disorcers, In the 1-4 year group, mortality seems to be specifically

related to respiratory, digestive and parasitic diseases. These in

turn are aggravated by poor environmental sanitation, over-crowded

living conditions, and malnutrition. Ignorance of simple health

precautions also takes its toll.

estimated that 30 per cent of all school-going children are

suffering from one or other ailment. Of children’s illnesses treated

at health centres, 56 per cent are reported to be related to intesti

nal infections, respiratory complaints and nutritional disorders.

rXLollmGn*S anc

due t0 poor diGt an^ P°or hygiene are also

Eruin? m-ny ^ildren needlessly go blind in early childhood.

Tuberculosis is widespread in small children.

Health Services

pGr C!ntx°£ Ino’ians live in rural and tribal areas, but

only 30 percent of hospital beds and 20 percent of doctors in the

country are available there.

-.ocrors in we

Medical care for the rural population is provided bv aovprn™=n+

ce?tres* Saoh centre is ^cted to I^^om

hPln0??? 80»000 people, spread over a hundred villages, with the

auxiliary nurse-Kif?“r™?iSaOT00peopleein°w':'i; JSC-,

9hkmaVean?eabou?S7eo?t"e%n ‘S'

Vl&?.a^ra^.r«iu0

and the health centre9!!’

Y

attention because 50 per cent of vill™ JoSn are’d!t 1 v

with!nt’ia!t theY afnnot tarry their small children to the FHC

health seh^e9 ^?f1Y ear"ln?s- ^tr the govern!°s n!«™ural

araduali5hov+Z HtllakerL^rainec! as com™nity health workers are

ranges from 20 to 50 per cent inViFfe^-^ ’o^he^o^y?

the^illages?

f"”’

and Haryana do not have any children’s hospitals^? 'all^31’ Gujarat

P^°P°^ionnofmtherwomennandhchildrentwhoGrVi^6+hreSC^ °nlV 3 sma11

15-45 age group constitute neailv 99

to^n in the

+^iluren in thG °-6 age group compriseeLn+h1 0^the Population, and

fGr cent’ Afeeting

the health needs of this943 per ?e^t of th^^

major national task.

P°Pula^1on remains a

Water and Health

Water-borne and water-relatpd

infants and children. About 163 millinn^h^?^ loading killers of

rural India do not have access to

^^^n (0-14 years) in

thus exposed to infection which can^rov^faS/31^’ and th® are

1.6 km away, or i^sub-stand^rd^and^s res§ly *bieiehGr feore than

wells, streams,

adequate ip quantity, but

is open to the

-- -J

There are at least 185,000 villages where the

supply of water is both

inadeauatp anc ur)protectriH

risk of pollution.

’

NUTRITION

Malnutrition is a major cause of death among children in India. Every

month 1,00,000'children die from its effects. An even larger number

of children die of infectious diseases, their poor diet having made

them susceptible to infection and vulnerable thereby to death.

Children survive malnourishment depending on the degree of deficiency.

For every child who shows clinical signs of malnutrition, there are

probably at least 4 children suffering from milder grades of

malnutrition without clinically apparent in India.

Approximately 80 to 90 per cent of Indian children do not receive

adequate amounts of key vitamins and minerals; 75 per cent do not

receive adequate calories and about 50 per cent do not receive

enough proteins.

Acute diarrhoeal diseases are more frequent and serious among these

malnourishec chilcren than among those of normal nutritional status.

Pre-School Children

Some 60 per cent of children in the 0-6 years are group suffer from

nutritional anaemia and protein-calorie malnutrition in one

form or the other. Almost 40 per cent of all deaths in the country

P?OUP ancJ

majority of these fatal cases are

A deficiency and anaemia. Again,

three-fourths of the children in this age group have body weights

below 75 per cent of the standard weight of well-nourished children,

52 per cent suffer from moderate malnutrition, 23 per cent from

severe malnutrition and only 3 per cent can be considered as

having normal body weight.

Sn+Cn|n+^°m the ^^.socio-economic strata suffer the worst, 30 per

ar! Vlc,tims of mocerate or severe protein-calorie maln trition, as shown by their sub-standard body weights.

School-Going Children

It is estimated that 22 per cent of the school-going children show

one or more signs of nutritional deficiency. The most common Zre

and lack of vitamin A and Vitamin B-Comolex

anaemia,

A murh

froS f^oclo-oconomc

«6

uo 3 ?56PSIOn

sSb^aXe-’toPy wlghHf

E15"? °.f "Operate protein -calorie

•'*"

'“In^rltion, reflected in

V tt$mi n A Deficiency

early cliLdhoo^becaus^their die^lacks^if31^* by ,blindness in

Vitamin A. Severe Vitamin A

deficiency is estimated at a

10 14’00°

Ab°Ut 12

children of the toddler age gSio

[ syery year because of this

deficiency. Lack of the vT+^m? P-c

bli"^that afflicts about

-S'vitamin

t0 <'?tarV ^Hclency

such blindness is in

Child Nutrition and the Family

ccams are cue to prematurity.

°f

sk

the premature

per cent of infant

ti^rjv1:? jf^acTcMfJ Yse?eytfanih S?2e is

-■■■« o

the nutri, the

,

---- - Research

only

£M1^ a^-Jr^n^^^ayn^riHoy" horn to a family, °"

ly

among the fourth and

symptoms.

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE

Of the 1550 million children in the world, one in every six is an

Indian. The 248 million children of India thus comprise nearly 16

per cent of all the world 's children.

India’s population is rising faster than the world rate, and the

addition of some 13 million infants every year gives India one of

the world's youngest populations. The 1971 Census showed that

42 per cent of the Indian population consists of children under

14 years of age. Children below 6 years comprise 21 per cent of

the population.

An index of the population composition is that while the entire

population of India in 1911 was 252 million, projections indicate

that children alone already numbered 248 million in 1976, and a

more recent estimate puts the child population in 1977 at 255 million.

The Twentieth Century will close with the number of children in

India almost certainly exceeding the total Indian population of 279

million recorded in the 1931 Census.

Urban-Rural Ratios

An estimated 81 per cent of India's children live in the rural areas.

According to population projections for 1976, the rural children

number 183.9 million, tribal children 14.9 million and urban children

49.7 million. These projections also indicate that nearly half of

India's children (48.7 percent) are below 6 years of age. Of the

121 million in this age group, 89.7 million live in the villages

and 7.3 million in tribal areas, while 24.2 million are in urban

areas.

Li ving Cone-it ions

According to 1976 projections, about 99.4 million children — nearly

two-fifths of the total Indian child population - live in conditions

adverse to survival. Of them, 43.5 million, or nearly half, are

less than 6 years olb.

The 1976 estimates place 35.8 million of these

youngest deprived

children in rural areas, 9.7 million in urban

areas and 2.9 million

in tribal areas. In the next age group (7-14 years),

50.9 million

children live in extreme poverty -- 37.7 million in

the villages,

10.2 million in towns and cities and 3 million in

tribal areas.

A more recent estimate (April 1977), indicates that as many as 126

mi ion children may be living below the poverty line.

Position: 1081 (7 views)