Radical Journal of Health 1988 Vol. 3, Nos. 2-3, Sep. – Dec. Health and Human Rights.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

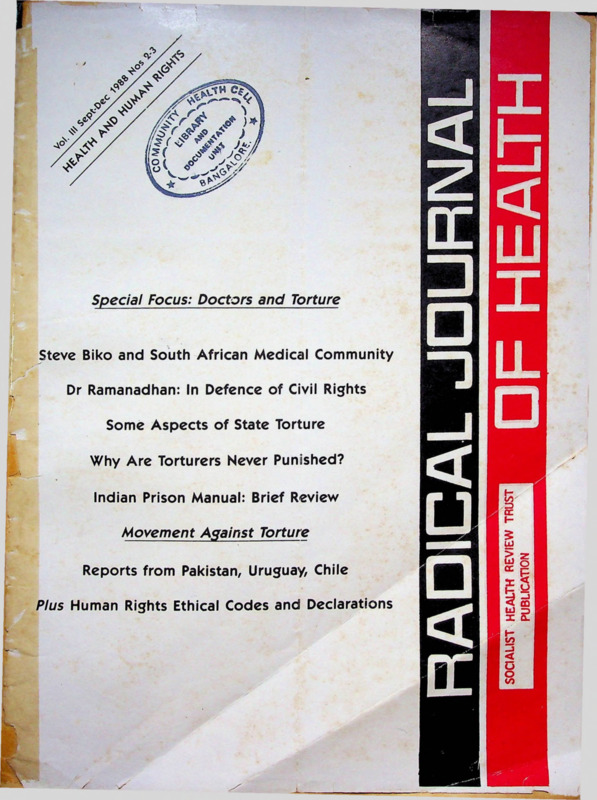

Special Focus: Doctors and Torture

Steve Biko and South African Medical Community

Dr Ramanadhan: In Defence of Civil Rights

Some Aspects of State Torture

Why Are Torturers Never Punished?

Indian Prison Manual: Brief Review

Movement Against Torture

■ ■'

Reports from Pakistan, Uruguay, Chile

Plus Human Rights Ethical Codes and Declarations

B

VX

L \

Volume III

September-December 1988

Nos 2-3

HEALTH AND HUMAN RIGHTS

<u

SPECIAL FOCUS ON DOCTORS AND TORTURE

33

Editorial Perspective

DOCTORS AND TORTURE

35

MEDICINE AT RISK

DOCTORS AS HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSERS AND VICTIM

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

40

Working Editors:

STEVE BIKO AND SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL COMMUNITY

Mary Rayner

Amar Jesani, Padma Prakash,

Ravi Duggal

50

IN DEFENCE OF CIVIL RIGHTS

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF DR RAMANADHAN

Editorial Collective.Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (AP)}lmrana

Quadeer, Sathyamala C (Delhi), Dhruv Mankad

(Karnataka), Binayak Sen, Mira Sadgopal (M P), Anant

Padke, Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar, Manisha

Gupte, Srilatha Batliwala (Maharashtra) Amar Singh

Azad (Punjab), Smarajit Jana and Sujit Das (West

Bengal)

Editorial Correspondence:

53

WHY ARE TORTURES NEVER PUNISHED?

CASE OF ARCHANA GUHA

Peter Vesti

56

STATE TORTURE: SOME GENERAL PSYCHOLOGICAL AND

PARTICULAR ASPECTS

Fernando Bendfeldt-Aachrisson

62

Radical Journal of Health

C/0 19 June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay- 400 050 India.

Mehboob Mehdi

Printed and Published by

INDIAN PRISON MANUAL

PARTICIPATION OF DOCTORS IN TORTURE

REPORT FROM PAKISTAN

64

DOCTOR AND PRISONER

Dr. Amar Jesani for

Socialist Health Review Trust from C-6 Balaka

Swastik Park, Chembur, Bombay 400 071.

Colin Gonsalves

65

IMPLICATIONS OF PHYSICIANS IN ACTS OF TORTURE IN URUGL

Gregorio Martirena

Printed at;

68

Bharat Printers, Shivshakti,

Worli, Bombay.

MISSION TO CHILE

REPORT OF WORLD MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

Andre Wynen

Annual Subscription Rates:

70

30/- for individuals

Rs. 45/ for institutions

Rs. 500/- life subscription (individual)

US dollars 20 for the US, Europe and Japan US

dollars 15 for othgr countries.

We have special rates for developing countries.

ACTION AGAINST DOCTORS INVOLVED IN TORTURE

Francisco Rivas Larrain

Rs.

SINGLE COPY: Rs. 8/(All remittance to be made out ih'favour of Radical

Journal of Health. Add Rs 5/- on outstation cheques).

72

PRESS REPORTS ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION IN INDIA

Book Review

73

TORTURE, PSYCHIATRIC ABUSE AND HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

R Raghav

76

HUMAN RIGHTS ETHICAL CODES AND DECLARATIONS

Editorial Perspective

Doctors and Torture

TORTURE is condemned universally as inhuman and as

a calculatedly cruel practice. As such it should not find

any place in any civilised society. Yet its widespread use

is a truth that cannot be denied. To a greater or lesser

extent it is resorted to in all countries. Why is this so? Why

do countries which apparently place a high value on

human rights routinely practise and condone physical and

mental abuse of its opponents both in times of war and

in peace?

Torture has been recorded in history since the ancient

times and there have been references to torture in the 12th

and 13th centuries, and even earlier. The TUdor and Stuart

monarchs made frequent use of torture. But it was dur

ing the religious and political struggles of the 16th and

17th centuries in European countries that there was more

open discussion of the subject. Indian history also is

replete with references of torture of political prisoners.

It was in the 18th century that a movement against this

cruel inhuman practice was initiated with the hope that

by the end of the 19th century this practice would be

abolished altogether. But the reality of concentration

camps in Germany under Nazi rule, with their largescale

use of torture wiped off this optimistic belief. However,

it was in the aftermath of the war and the end of Nazi

rule that serious attempts were first made to set out norms

of conduct for medical people participating in torture.

Torture is among the most reprehensible aspects of state

repression. Unlike other forms of repression, it can be car

ried out in private and in such a manner that none but

those against whom it is used come to know of it. So it

can be practised with impunity within smiling democracies

professing to be ‘open’ societies ensuring freedom of

speech, expression etc. to its citizens.

Torture is used to suppress dissent against the state and

its ideology in various ways. It is used extensively to ex

tract infqrmation—and this use is often protrayed as be

ing justified in order to maintain ‘law and order’. But more

importantly, it is used to strike terror in the hearts of those

who oppose it. A torture victim becomes a warning to

others who may follow his/her path for much the same

reason that feudal barabaric societies displayed severed

heads or conducted public hangings.

The Indian state has consistently and widely used tor

ture to quell rebellion and protest whether it is to supress

movements of minorities for autonomy or those which

pose an ideological challenge to the state. In Telengana

in the 40s and Naxalbari in the 60s and fOs and Bihar,

Punjab and Andhra Pradesh in the 80s the state’s police

have systematically and routinely used torture on political

prisoners so much so that they have perfected methods

which cause pain and suffering to the individual but leave

September-December 1988

no mark which can be displayed to monitoring authorities,

such as they are. And in all this at some level or other—

whether in diagnosing and treating a victim of torture or

in issuing death certificates of those who have succumb

ed to it or in many other numerous small ways—is involv

ed a health worker most often a medical professional, who

ironically enough is pledged to preserve life and reduce

suffering.

Here there are two aspects which must be touched upon.

Usually torture in most codes is defined to mean the abuse

of person in the custody of the authority. In a larger sense

and increasingly, it includes the physical and mental abuse

meted out to the friends, relatives and others close to the

victim. Again the evidence of torture becomes valid only

with the involvement of the medical profession. Second

ly, sexual abuse and assault on women held in custody

or held for ‘questioning’ is becoming increasingly fre

quent. And in most cases, it is medical evidence which

will help in bringing the victimisers to book. The medical

profession thus plays a crucial role in protecting human

rights.

The United Nations, in 1975, in its Declaration, has

defined torture as: “Torture means any act by which severe

pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentially inflicted by or at the instigation of a public official

on a person for such purposes as obtaining from or a third

person information or confession, punishing him for an

act he has committed or is suspected of having commit

ted, or intimidating him or other persons. It does not in

clude pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or

incedental to, lawful sanctions to the extent consistent with

the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Priso

ners. Torture constitues an aggravated and deliberate form

of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”

(see Health and Human Rights, ICHP/cinpros 1986, p 25).

As Paul Sieghart states (p 95) the “prohibition against

torture contains no limitations or exceptions of any kind

and allows no derogation in any circumstances—not even

in times of war or public emergency treating the life of

the Nation” (Emphasis added).

Doctors As Victimisers and As Victims

It is an irony that the “protectors of law and order”—

the police themselves employ the method of torture which

is so universally condemned but what is unthinkable is

the involvement of doctors (actively or passively) in tor

ture, particularly when they happen to be police, prison

or military doctors. The conflict between the ethical posi

tions of the prison doctors and national laws are real and

superficially bewildering but certainly not unresolvable

33

As Dr. Wyner of the World Medical Association clarifies

“that if a certain legislation is criminal and contrary to

ethics, the doctor has the deontological duty to ignore it

and in some cases, even oppose it when practicing his pro

fession”. It is thus gratifying to learn and in Switzerland,

the prison doctors and subordinate medical authorities

alone are responsible for the prisoners’ health and thus

find it easy to maintain the patient-doctor relationship.

Such a trend must spread to other countries as well.

So far as the ethical codes on the subject are concern

ed, there need be no ambiguity in the mind of the medical

practfoner. The UN Declarations and codes relating to

Principles of Medical Ethics, the Declaration on the Pro

tection of All Persons from Torture and Other Cruel, In

human or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and (iii)

Standard Minimum Rules for the treatment of Prisoners

and related recommendations are amply clear and con

cise to permit any grey areas. Furthermore, the statements

by various orofessional associations viz. that of (i) physi

cians, (ii) psychiatrists, (iii) nurses and (iv) psychologists,

also leave no stone unturned in respect of the ethical posi

tions. [Elsewhere in the issue we carry the full text of some

of there codes and statements]

Even so, there are reports revealing medical practioners

attending the interrogation of punishment centres for examing the detainees to certify on their health and later

administering treatment for the victims* injuries. Some

of them are even reported to be active in torture. How

else could one explain some of the more modern and

sophisticated methods of torture which could not have

been devised without the active participation of experts

(forensic) having a high degree of knowledge in the area?

To the exteqt that many of its members contribute to tor

ture, the whole medical fraternity must also share his guilt

and it is for the respective medical councils to pull up its

members. Medical fraternity must do all that is in its col

lective power towards eliminating this obscene, cruel, in

human practice that is internationally outlawed.

The doctor compounding or assisting torture discar

ding the ethical norms is obviously only one facet of the

situation existing today, but consider the scene where (and

this*is known to take place more after in some countries

under some dictatorial regimes) the doctor has had to pay

heavy penalties including his life for having listened to

his consciense and abiding with ethical codes laid down.

Often a doctor is penalised for helping the victim of state

repression or for supporting movements for justice. One

such victim of police brutality was Dr. Ramanadhan who

was shot dead the state police in September 3, 1985. We

publish in this issue a short biographical sketch of the

doctor-activist. Undoubtedly, health workers who use their

professional skills to help those who protest against the

state are themselves vulnerable. Particularly under the dictitorial regimes the reality is such that people’s protest

34

against such actions cannot be expected to operate. In

ternational pressures need to be applied and the Human

Rights wing of United Nations have a pertinent role in

this.

What about the repurcussions of torture on physical

and mental health of the tortured? On the family? And

the responsibilities of medical and social scientists in this

matter? It is clearly imminent that torture would both

physically and more importantly mentally wreck the vic

tims’ and ruin them and their families but sadly there are

not enough studies on this important issue in our coun

try [see the case of Archana Guha in this issue]. Such

studies, if nothing else, could serve well towards

eliminating the apathy towards this distantly occuring

nonetheless sensitive issue. Surely it must be remembered

that until empathy towards the tortured does not percolate

through vast multitude of peoples, elimination of this in

human practice will keep eluding us time and again.

Why have we chosen to highlight the issue of the role

of the health worker in preserving human rights, especially

in state torture? Firstly, because as we have seen, the

medical profession plays a crucial role both in perpetrating

torture but also in publicising its use and bringing the vic

timises to book. In doing so, the health workers

themselves become vulnerable to attack. It is therefore

necessary that a strict code of conduct be implemented.

Also, doctors who are placed in vulnerable situations must

be ensured safety. In times of war, for instance, medical

help is always ensured safe conduct. In times of peace too,

it should be possible to safeguard the life of people who

give medical aid.

Secondly, there nas been an increasing incidence of

police torture and inhumanity. With the growth of

political awareness, mass movements are on the upswing.

The state is bound to become more repressive and if this

repression is to be effective while maintaining the facade

of democratic functioning, it has to use such instruments

which focus on the individual and are hidden from the

public eye. There is a tendency to legitimise torture (say,

by branding the victims as ‘terrorists’). Again there is need

to create an awareness of where, how and in what cir

cumstances torture takes place and the role the health

worker plays in this. It is also necessary to empower them

with information on how they can be coerced into abet

ting torture and what they can do about it.

While we highlight some of the major issues in the field

and how the international community of health workers

have tackled it this is certainly not the last word on the

subject. There is a particular lacuna about information

on India. We hope the issue will generate discussion on

the issue and lead to documentation of the Indian

situation.

Anil Pilgaokar

September-December 1988

Medicine at Risk

Doctor as Human Rights Abuser and Victim

Amnesty International

For over a decade now, the Amnesty International has been working to eradicate the use of torture. In this

effort, it has paid special attention to the role of health workers in human rights violations as well as the violation

of the human rights of people working in health.

[This paper was prepared by the Internationa! Secretariat of the Amnesty International and circulated as a background paper

for the International Seminar on the same subject at Pans from January 19 to 21, 1989.]

IN 1978, Amnesty International convened an international

meeting in Athens which brought together some 100

health professionals from 13 countries to discuss ‘medical

detection and effects of torture, the need for treatment,

rehabilitation and compensation of torture victims, and

other work of the medical profession against violations

of human right’. Among the many conclusions and recom

mendations made by the participants, three themes were

identified for continuing study and campaigning. T\vo of

these particularly relevant to the subject of ‘medicine at

risk’ were strategies for the prevention of torture, and the

elaboration of medical ethics codes against torture [1].

Despite continued widespread human rights violations,

there have been since 1978 a number of positive

developments with regard to prevention of medical in

volvement in torture and two in particular might be men

tioned here. The first was the adoption by the United

Nations General Assembly on 18 December 1982 of the

Principles of Medical Ethics Relevant to Health Profe

ssionals, Particularly Physicians, in the Protection of

Prisoners from Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or

Degrading Treatment or Punishment. These, together with

the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Tokyo of

1975, offer the clearest ethical guidance to the health pro

fessional confronted with the problem of torture.

The second encouraging development has been the

active public opposition of some medical and other

associations to torture and their commitment to disciplin

ing those health professionals who participate in it.

However in the face of continuing human rights viola

tions and despite committed work by human rights groups

and professional bodies [2], a wider degree of engagement

by health professionals in supporting colleagues at risk

would make a significant contribution to the fight for

human rights.

This paper reviews some of the issues implicit in the

theme ‘medicine at risk’: that is, participation of health

workers in human rights violations, the violation of the

human rights of those working in health care; and the

role of professional associations in dealing with these

abuses.

Human Rights Standards

Human rights violations are contrary to the principles

of all the healing disciplines. Ethical standards of a wide

September-December 1988

relationship of the practitioner and his or her client should

be based, inter alia, on principles of beneficience and

respect for the client’s autonomy.

However, dealing with prisoners poses certain dif

ficulties to medical and other personnel since prisoners

have lost their freedom with concomitant restrictions on

their autonomy; secondly, the health professional has

obligations with regard to the detaining authority which

they may see as threatening the concept of medical confidentality, in practice if not in principle. Nevertheless, the

ethical standards have been clearly set out.

The World Medical Association, at its assembly in

Tokyo in 1975 adopted a declaration which stated that it

was prohibited for a doctor to “countenance, condone or

participate in the practice of torture or other forms of

cruel, inhuman or degrading procedures, whatever the of

fense of which the victim to such procedures is suspected,

accused or guilty.. .” [3] The World Psychiatric Associa

tion, in its Declaration of Hawaii [1977] stated, inter alia,

that “no procedure shall be performed nor treatment given

against or independent of a patient’s own will...” and

“the psychiatrist must never use his professional

possibilities to violate the dignity or human rights of any

individual or group...”.

Nurses’ and psychologists’ associations have also set

out the responsibilities of these particular professions with

regard to the care of those in detention.

An international code applying to all health

professionals— The Principles of Medical Ethics—which

embodied many of the elements of the Declaration of

Tokyo, was adopted by the United Nations on December

18, 1982. This states categorically inter alia that it is a con

travention of medical ethics for “health personnel, par

ticularly physicians, to engage... sub acts [of] torture or

other cruel inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment”.

Unfortunately, in spite of the elaboration of these com

prehensive standards, there is irrefutable evidence that in

many countries professional expertise continues to con

tribute to human rights violations.

These breaches of professional ethics are manifested in

a number of ways, including participation in the practice

of torture. Direct involvement takes a number of forms:

Examination of prisoners before interrogation to en

sure that the prisoner can survive torture or to find sen

35

sitive fpci for exploitation during torture.

lb monitor the torture process: to stop the torture if

it threatens the prisoner’s survival or to resuscitate the vic

tim where necessary.

lb ‘patch up’ the victim after torture, possibility to

undergo further sessions or to make the prisoner presen

table for appearance in court or after release.

To provide the police or other authorities—under

pressure or by free will—with false certificates stating that

the prisoner is in good health or, in event of their death,

certifying a false and misleading cause of death.

lb advise the torturers or to directly use medical or

psychological techniques during interrogation eg. giving

sensitive information obtained during the interview or

helping administer drugs [4].

Other abuses of medical expertise constituting infr

ingements of medical ethics and human rights include:

Falsely certifying that an individual is seriously men

tally iU in order to have them committed forcibly to a men

tal hospital so as to curtail their political activities.

Advising executioners of the progress of an execution

to enable them to continue or to modify whatever techni

que they are using.

Using medical skills to mutilate an individual as a

punishment or advising others in the application of such

skills. [5]

Reasons for participation by health professionals in

behaviour of the kind cited above can, for the most part,

be the subject of speculation only; most of those who take

part in torture do not set out their reasons for doing so

[6]. However there is enough evidence to suggest that the

motives [or rationalisations] include some of the

following:

Fear of consequences of refusal or seeing open opposi

tion to abuses as an impossibility for whatever reason.*

Doctors under military discipline may feel, like others, that

they are under irresistable pressure to participate. In his

study of the behaviour of Uruguayan physicians during

the period of military rule [1973-1985], Bloche could iden

tify only one health professional working with political

prisoners who openly refused to collaborate in abuses [7].

Identification with the cause of the torturers and a

belief that serious measures are justified by what are seen

as serious threats to national security. The Chilean Physi

cian Alfredo Jadresic cited a young doctor explaining his

collaboration in military abuses at the Chile stadium after

the 1973 coup in these terms: “What do you expect? We

are at war?’[8]

Defining the doctor’s function as essentially a

bureaucratic one. A female Uruguayan prisoner testified

to pleading with a doctor to obey his physician’s oath;

she said that he replied; “I’qi just doing my job” [9].

Inadequate understanding of professional ethics: for ex

ample. to see it as the health professional’s job to minimise

36

suffering resulting from torture or ill treatment through

participation in the interrogation process.

The psychological mechanisms and ideological analysis

by which doctors have justified participation in systematic

human rights violations have been examined in depth by

Lifton [10] with respect to doctors in Nazi Germany, and

more briefly with respect to Uruguay during the military

government of 1973 to 1985, by Bloche [II].

Lifton suggested the concept of “doubling”—ie. the

creation of a second self who could participate in a life

style and professional conduct which might ordinarily be

seen as in conflict with the individual’s underlying moral

and professional values. He refers to the ‘technicalisation’of the medical role [dissociating the technical aspects

of their function from the moral values associated with

it] and a related psychological distancing. [Lifton points,

for example, to doctors’participation in selection of vic

lims for the gas chambers, noting that “by not quite see

ing it, they could distance themselves from the very kill

ing they were supervising; selections could be accepted as

an established activity and seem less onerous than special

ly brutal tasks [such as medical collusion in torture to pro

duce confessions]...”; pp. 199-200]. He suggests [p. 200]

that such a view could also be interpreted that selection

for killing was so onerous “that Nazi doctors called forth

every possible mechanism to avoid taking in

psychologically what they were doing [emphasis in

original]. Other authors have dealt more generally which

the motivation of tortures [12].

Participation in

Violations of Human Rights

Evidence of the participation of health professionals

in abuses of human rights is, unfortunately, readily found

but perhaps not widely discussed or acknowledged. The

report by the British Medical Association on doctors and

torture, published in 1986, concluded that “the evidence

given to the [BMA] leaves no room for doubt that doc

tors are involved in many pans of the world in the physical

and psychological torture of prisoners?’[13].

Documents published by Al both before and since the

publication of the BMA report as well as reports from

other medical associations [Chile, Uruguay, Turkey] and

organisations [such at the American Association for the

Advancement of Science] all confirm this phenomenon.

Abuses of psychiatry for political reasons have been

documented in the USSR, Czechoslovakia, Romania and

Yugoslavia, though the role of psychiatrists in these abuses

probably varies from those who knowingly falsify a

psychiatric diagnosis with the express purpose of colluding

in the imprisonment of a political or social non

conformist to those whose role is more passive and who

fail to protest at the failure of the legal system and their

September-December 1988

own colleagues and superiors to protect individuals from

such abuses. The motivations of psychiatrists involved in

these practices probably include genuine belief in the

diagnoses such as ‘sluggish schizophrenia’ [14] as well as

conformist, bureaucratic and ideological reasons 115].

With regard to the death penalty, the role of the health

professional is not well documented apart from the case

of the LISA where there has been a vigorous debate on

the ethics of professional participation. Physicians have

argued against [16] and for [17] physician involvement in

execution by lethal injection, though the American

Medical Association has made clear that any involvement

would be unethical.

The American Psychiatric Association and the

American Nurses Association have both ruled participa

tion unethical though some psychiatrists still present

evidence based on hypothetical questions relating to the

defendant’s “future dangerousness” in death penalty cases

[where their evidence can be highly influential in secur

ing the death penalty] despite the view of the APA that

such testimony has no value a$ expert testimony since

psychiatrists are no more accurate in such predictions than

non-psychiatrists [18]. The ethics of such behaviour has

yet to be ruled upon by the APA.

The involvement of health professionals in certain other

humartgights violations—flogging, amputations, prolong

ed solitary confinement—is more contentious since these

abuses are provided for by a law in some countries and

doctors’ presence at their infliction may be specified in

law. However, some individual doctors and some medical

associations have nevertheless protested at such punish

ments being carried out in their country. For example, the

Mauritanian Association of Doctors, Pharmacists and

Dentists expressed ‘deep concern’ at the involvement of

physicians in the punitive amputation carried out on three

convicted thieves in September 1980. Another amputation

took place in June 1981 and again a doctor was involved

though it was reported that two amputations carried out

in 1982 were executed by a medical auxiliary following

refusal by doctors to assist. In Pakistan, both the Karachi

branch of the Pakistan Medical Association and the

Pakistan Junior Doctors, Association voiced their con

cern about flogging of political prisoners.

“The problem with torture”, concludes the BMA report,

'“is not whether it is right or wrong. It is how to detect

nthe subtle changes in relationships which lead to the doc-tior’s acquiescence in torture.” It continues:

The experience of those who gave information to the [BMA]

demonstrates that a refusal to compromise is effective in the early

stages, firstly because the doctor himself is less likely to be compromis

ed and secondly because the apparatus of the state is likely to be

vulnerable to concerted public opposition. Once these early stages have

been allowed to pass unchallenged, it may be too late to avoid serious

abuse. [19]

September-December 1988

Violation Against Health Professionals

Reasons for repressive measures being taken against

health professionals include: (i) their real or perceived

peaceful or violent political activities against the govern

ment; (ii> their activities in human rights groups; (iii) their

professional activities or criticisms of government health

policy; (iv) their giving treatment to injured armed op

position; (v) the perceived deterrence value of making an

example of the health professional; (vi) accidental reasons

[for example, being in the wrong place at the wrong time].

In many, perhaps most cases, persecution cannot be

simply attributed to one unique reason. Doctors who are

active in political opposition groups may also be engag

ed in human rights activities. Similarly, those who criticise

health standards or government policy on health may also

be seen as politically active, or involved in human rights

action and so on. While the rights of doctors to participate

in political activity must be protected in the same way that

any citizen’s political rights should be protected, the par

ticular focus of this paper is the risk of doctors being vic

timised because of their professional or human rights

activities.

The actions which precipitate repressive measures can,

in some cases, be substantially attributed to human rights

activities: the attacks are focussed and concern individuals

whose prominence owes a lot to their position as a human

rights activist.

In Colombia for example, two doctors active in the

Committee for the Defence of Human Rights [CCDHM]

were the victims of political killings in 1988. On 25 August

1988, Dr Hector Abad, aged 65, and Dr Leonardo

Betancur, aged 41, were shot as they were leaving a ser

vice for the president of a teachers’ union who had been

killed that morning. Dr Abad, who was a former Dean

of the Medical School, reported receiving death threats

shortly before his murder.

In the USSR, those involved in the work of the un

official Moscow Working Commission to Investigate the

Use of Psychiatry for Political Purpose were detained in

connection with their work in documenting the practice

of internment of prisoners of conscience on spurious

psychiatric grounds. Dr Leonard Ternovsky [b. 1933], a

radiologist, was arrested on April 10, 1^80 in Moscow and

was charged under Article 190-1 of the RSFSR Criminal

Code with “anti-Soviet slander”. He was subsequently

convicted and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment.

Other members of the Working Commission were also im

prisoned in the period 1980 to 1981, culminating in the

sentence of 12 years’ imprisonment and internal exile for

Dr Anatoly Koryagin, the psychiatric consultant to the

Working Commission, following the publication in the

British journal The Lancet [20] of a paper describing his

experiences of the misuse of psychiatry for political

purpose.

37

More widespread and indiscriminate repression occur

red in Syria during the period 1978 to 1980, when there

was pressure on the Syrian government from lawyers and

other professionals to implement measures included lif

ting the State of Emergency in force since 1963. In early

March 1980, meetings of dentists, pharmacists, engineers,

lawyers, teachers and medical association representatives

in different Syrian cities urged the introduction of reforms.

On March 21 1980, a general conference of the Syrian

Medical Association met in Damascus and passed a reso

lution which included the following demands:

Re-affirmation of the principle of the citizens’ rights to freedom

of expression, thought and belief;

Denunciation of any kind of violence, terror, sabotage and armed

demonstration, whatever the reasons and justifications;

Abolition of exceptional courts;

Release or trial of all detainees

On March 31 1980 a one-day strike was called by lawyers

in Damascus and this was supported by other branches

of the Bar Association and by other professipnal associa

tions including members of the Syrian Medical Associa

tion. Shortly after the strike, the national congress and

regional assemblies of the Medical, Engineers and Bar

Associations were dissolved by the Syrian Ministerial

Cabinet. In the days that followed the dissolution,

numerous lawyers, doctors and engineers were arrested

and held without charge or trial. At least two doctors were

later executed and some 100 doctors remain imprisoned

still without charge or trial more than eight years after

their arrest.

In Central America, a wide range of health profes

sionals were subjected to intense repression in El Salvador

and Guatemala in the period 1980-1982 and in a less in

tense way in subsequent years. Some of the victims of the

torturers and ‘death squads’ were active government op

ponents but the institutionalised nature of the abuses and

the impunity with which those perpetrating the human

rights violations could act meant that those with little or

po political engagement were also victimised.

In July 1980 a United States Public Health Associa

tion Commission visited El Salvador and reported an

alarming pattern of military incursions into hospitals and

abduction and murder directed against health personnel.

Their report listed 23 health professionals who were kill

ed or had disappeared in the period January to June 1980.

Many were tortured before their murder.

In Guatemala, an equally disturbing pattern of attack

directed against health workers was occurring. On April

23 1981, a 32-year-old doctor, Dr Otto Raul Letona, was

shot 12 times in the torso by unidentified gunmen as he

stood in the emergency ward of a hospital in Antigua,

talking to a patient. Another 13 medical personnel were

reported killed during the first half of 1981 alone.

In both El Salvador and Guatemala, being involved in

providing health care to the rural poor appeared to be

38

linked—in the view of the military—with subversion and

opposition. The widespread and indiscriminate nature of

the repression particularly in the early 1980s suggests that

the definition of subversion was very loose and could be

applied to anyone working to improve the situation of the

peasants. In some cases, doctors did treat members of

armed opposition groups or individuals who had sustain

ed bullet wounds; occasionally doctors were detained for

giving this help though it was much more common that

a doctor suspected of ‘aiding the opposition’ would be

dealt with extra-judicially.

Where torture, ‘disappearance’ and political killings are

everyday realities [as in El Salvador and Guatemala dur

ing the period under consideration], the options for a

health professional appear rather limited. Even if they

wish to remain outside politics they are obliged to ensure

that anyone with injuries should-receive medical care and

must, as a consequence, evaluate the best way to ensure

the physical security of their patient. A number of cases

have been documented where medical personnel have not

reported patients with bullet wounds as required by law

in circumstances where they could reasonably fear that

reporting would lead to their patient being tortured or kill

ed. This action in itself may make the doctor a target for

human rights violations.

Since 1980, Amnesty International has issued medical

appeals on behalf of health professionals in the follow

ing 30 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Benin,

Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, El Salvador,

German Democratic Republic, Guatamala, Iran, Laos,

Nepal, Paraguay, Republic of Korea, Romania, Singapore,

Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Taiwan, Turkey,

Uganda, USSR, Uruguay, Vietnam, Yugoslavia, Zaire.

Role of Professional and other Associations

The central role of professional associations in assisting

health personnel at risk of being pressured into col

laborating in, or remaining silent about, human rights

violations is alluded to in the last article of the WMA’s

Declaration of Tokyo, this states that:

The [WMA] will support, and should encourage the international com

munity, the national medical associations and fellow doctors, to sup

port the doctor and his or her family in the face of threats or reprisals

resulting from a refusal to condone the uses of torture or other forms

of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Unfortunately, in many cases the associations

themselves are under severe threat or acute repression. As

noted above the Syrian Medical Association was dissolv

ed after calling for human rights reforms in 1980;

members of the Turkish Medical Association were pro

secuted in 1986 for calling for an end to the death penal

ty in Turkey; the Chilean Medical Association was raid

ed by security agents in 1986 at the time it was organis

ing a meeting with international participation on the

September-December 1988

theme of the role of medical associations in the protec

tion of human rights.

However, it is striking that medical associations and

other professional bodies in countries where abuses occur

systematically have frequently not spoken out against

them nor taken any apparent action against health pro

fessionals collaborating in torture, covering up deaths

following ill-treatment or carrying out other unethical

acts. Individuals doctors seeking support from their

association or an obvious body to whom to complain,

may interpret the silence of the professional association

[sometimes correctly] as a disinterest in the issue or an

unwillingness to speak out. If the professional leadership

will not speak out, the pressure on individuals to remain

silent is all that greater [21].

Recently, the Uruguayan Medical Association has been

active in promoting the idea of an international medical

forum for the hearing of evidence of medical abuses

against human rights. This idea was recently supported

at a meeting in Geneva in October 1988 of the Inter

national Council of Health Professionals. Some specialist

groups of professionals have looked at ways of using their

own expertise to counter human rights violations. For ex

ample, forensic scientists have contributed to the drafting

of a protocol for the investment of deaths in detention

or.in order circumstances where a proper investigation of

the cause of death should be instituted [22], and have par

ticipated in a number of investigations which have had

the objective of clarifying the fate of persons whose deaths

have been the subject of deliberate cover-ups.

While professional associations have a major role to

play in disciplining their members who assist human rights

violations and protecting members who are active in pro

moting human rights or who resist pressure to collaborate

in torture, other bodies also have an important role.

Human rights bodies can help translate and circulate

information, endeavour to break down isolation and give

support to both opponents and victims of torture and

other bodies; they can press governments to fulfil their

international treaty obligations; and they can offer inter

national solidarity—something which has been remarked

on as being of great support to those facing repressive

governments.

Notes

[ 1] The third was the rehabilitation of torture victims. See Viola

tions of Human Rights: Torture and the Medical Profession.

Report of an Amnesty International Medical Semianr, Athens

Mach 10-11 1987. Al Index: CAT 62/03/78.

[ 2] One of the associations which reversed a previous quiescent

stand on human rights was the Colegio Medico de Chile which,

after being permitted by the government to elect its own officers

for the first time since 1972, embarked on a programme of

medical ethical awareness, including the novel initiative of

publishing, in November 1983, the WMA’s Declaration of Tokyo

September-December 1988

as a paid advertisement in a major Santiago daily newspaper.

This reflected the Colegio’s belief in the importance of a public

and professional understanding of ethical standards particular

ly with regard to torture. See, Stover E. The Open Secret: Tor

ture and the Medical Profession m Chile. Wahsington: AAAS,

1987.

[ 3] For this and the codes cited below sec Amnesty International.

Ethical Codes and Declarations Relevant to the Health Profes

sions. Al Index ACT 75/01/85, 1985.

[ 4] Information on these abuses can be found in a number of

Amnesty International reports [see, for example. Recent Torture

Testimonies Implicating Doctors in Abuse of Medical Ethics in

Chile. Al Index AMR 22/29/84, May 31 1984] and also British

Medical Association. The Torture Report, London: BMA, 1986;

Stover E Nightingale. The Breaking of Bodies and Minds. New

York: Freeman, 1985.

[ 5] In Sudan in 1983, a surgeon was included in a delegation sent

to Saudi Arabia to learn amputation techniques; he later par

ticipated in the carrying out of the first amputations in Sudan.

In Iran, a new amputation device was apparently designed in

1985 with the advice of medical personnel in Teheran.

[ 6] Occasionally some talk to the press; see a series of press ar

ticles about a Brazilian doctor who, in 1988, was disciplined by

the Regional Medical Council of Rio de Janerio for assisting

torture in the 1970s: Istoe, April 1, 8 and 15 1987.

[ 7] Bloche MG. Uruguay's Military Physicians: Cogs in a System

of State Terror. Washington: AAAS, 1987.

[ 8] Jadresic A. ‘Doctors and Torture: An Experience as a Prisoner’.

Journal of Medical Ethics, 1980, 6:124-7.

[ 9] [‘Yo solo cumplo con mi trabajo’.] Testimonies on detention

procedures, torture and prison conditions in Uruguay. Al In

dex: AMR 52/18/79, June 25, 1979.

[10] Lifton RJ. The Nazi Doctors. London: Papermac, 1987.

[II] Bloche, op cit.

[12] Ruthven M. Torture: the Grand Conspiracy. London:

Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1978; Peters E. Torture. Oxford:

Blackwell, 1985.

[13] BMA, op cit. p. 22.

[14] Reich W. ‘The World of Soviet Psychiatry’. In Stover and

Nighingale [eds], op cit.

[15] See Bloch S, Reddaway P. Russia’s Political Hospitals London:

Gollancz, 1977.

{16] Curran WJ, Casscells W. ‘The Ethics of Medical Participation

in Capital Punishment by Intravenous Drug Injection’. New

England Journal of Medicine, 1980, 302:226-30.

[17] Kevorkian J. Medicine, ‘Ethics and Execution by Lethal Injec

tion’. Medicine and Law, 1985, 4:307-13.

[18] Cited in Al. The death penalty in the [C/S>4 ].• an issue for health

professionals. Al Index: AMR 51/40/86, 1986.

[19] BMA report, op cit, p. 22.

[20] Koryagin A. ‘Unwilling patients’. The Lancet, 1981, z:821-4.

[21 ] Individual doctors can nevertheless speak out. The ease of Dr

Wendy Orr in South Africa is illuminating. On commencing

work as a district surgeon in the Port Elizabeth area in 1985,

she was struck by the number of prisoners alleging assault most

of whom had injuries consistent with their allegations; she noted

the complaints on the medical record cards, adding that these

should be investigated. When her efforts to have some action

taken on the persisting compalints of police brutality and tor

ture had no effect she sought an urgent ruling from the Supreme

Court restraining police from assaulting prisoners. An interim

injuction was made See Rayner M. Turning a Blind Eye?

Washington: AAAS, 1987.

[22] The Minnesota protocol: Preventing arbitrary killing through

an adequate death investigation and autopsy. A report of the

Minnesota International Lawyers Human Rights Committee.

Minneapolis, 1987.

39

September 7 and had attempted to assault an officer with

a chair.15

On the issu£ of proper hospitalisation, Dr. Lang told

the court that neither he nor Dr. TUcker had any option

but to acquiesce in security police demands. Dr. Lang

stated that he had the ‘impression’ that Mr. Biko could

not be transferred to a non-prison hospital because he was

regarded as “a security risk? Dr. Lang buttressed his

defence by claiming that “we [district surgeons] are

restricted in the sense that we cannot tell them where we

wanted a detainee. .. You cannot buck the security

branch?16

The effect of this particular line of defense was vitiated

when Dr. Lang later admitted to the court that he had

not really pressed the issue of hospitalisation with Col.

Goosen. Goosen, Dr. Lang said, could have interpreted

his reference to hospitalisation as necessary for diagnostic

rather than treatment purposes. When asked if he at any

stage suggested to Goosen that Biko was a sick man in

need of treatment in a hospital, Dr. Lang acknowledged:

“No, I did not?17

The two most egregious instances of questionable

behaviour raised against Dr. Lang during the inquest con

cerned his medical certificate and his final entry in the

bed letter. Col Goosen told the court that his request for

a medical certificate on September 7 was ‘plain logic’.

Dr. Lang’s certificate was, he added, completely satisfac

tory for his purposes. In the certificate. Dr. Lang had

recorded as the reason for holding the medical examina

tion that Biko “would not speak”. Yet, in his later report

to the pathologist conducting the post mortem, Dr. Lang

wrote: “The detainee had refused water and food and

displayed a weakness of all four limbs and it was feared

that he had suffered a stroke.” But, when asked to explain

the discrepancy between these two statements, Dr. Lang

could only reply: “I cannot explain it. It is inexplicable!’18

In the second part of Dr. Lang’s certificate of

September 7, he noted that he had found no evidence of

any abnormality or pathology. Dr. Lang admitted that this

claim was “highly inaccurate” as he had found evidence

of bruising, a lip injury, and edematous swelling of the

hands, feet and ankles. Counsel Sydney Kentridge then

asked Dr. Lang if it hadn’t occurred to him that, “if, at

some later stage, Biko might appear in court and com

plain about the way he was treated while in security police

custody, [his] medical certificate would be a most impor

tant piece of evidence”? The doctor agreed that it would

be but added that the possibility had not occurred to him

on the morning of September 7.19

Dr. Lang had similar difficulty in explaining the con

tents of the entry in the Sydenham Prison Hospital bed

letter, dated 10 September. He admitted that the statement

regarding the lack of evidence of pathology was false, he

knew that the cerebrospinal fluid was blood-stained, and

42

Excert From the Inquest

Kent

ridge: Why didn’t you stand up for the interests of your

(Counsel for patient? Biko family)

Lang: I didn’t know that in this particular situation one

could override the decisions made b\ a responsible

police officer.

Gord

on : Why didn’t you say that unless Biko goes to

hospital you would wipe your hands of it?

Lang: I did not think at that stage that Biko’s condition

would become so serious. There was still the ques

tion of a possible shamming.

Kent

ridge: Did you think the plantar reflex could be feigned?

Lang: No.

Kent

ridge: Did you think a man could feign red blood cels in

his cerebral spinal fluid?

Lang: No

Kent

ridge: In terms of the Hippocratic Oath are not the in

terests of your patients paramount?

Lang: Yes.

Kent

ridge: But in this instance they wer subordinated to the

interests of security?

Lang: Yes.

(Inquest into the death of Steve Biko,

Proceedings, in Bernstein, Biko, p. 94).

that Dr. Hersch had reconfirmed the extensor plantar res

ponse. Nevertheless, Dr. Lang argued that the misstate

ment arose from the inadvertent omission of the word

“gross” infron of “pathology”.20

In his testimony, Dr. Tucker, the chief district surgeon

in Port Elizabeth, attempted to explain his behaviour

towards the patient, both claiming that he had accepted

Col. Goosen’s theory of feigned illness and by alluding

to constraints affecting district surgeons’ activities in

relation to political detainees. At one point Professor

Gorden pressed Dr. Tucker to explain why he did not tell

Col. Goosen that he would disclaim all responsibility as

a doctor if Biko was not taken to a proper hospital.

Dr. Tucker replied that he did not consider the patient’s

condition as serious, as “there was still this question of

a possible shamming on his [Biko’s] part.” He did con

cede, however, that no one could feign an extensor plan

tar reflex or red blood cells in the cerebrospinal fluid, he

also accepted that, in terms of the Hippocratic Oath, the

interests of his patients should always be paramount. But

in this instance, Tucker admitted, as had Dr. Lang, that

rhey were subordinated to the interests of security. ‘‘I

didn’t knowj’ he said, “that in this particular situation one

September-December 1988

could override the decisions made by a responsible police

officer?’21

On several occasions during the inquest porceedings,

Dr. Tucker contradicted himself. Although stating at one

point his belief that Biko may have been feigning illness.

Tucker claimed elsewhere in his evidence that the though

of head injury had occurred to him. yet he failed to ask

the detainee the source of his lip injury or the police if

Biko had received a blow on the head. Dr. Tucker initial

ly denied that his reticence came from dealing with the

security plice. When Kentridge pressed him on this issue,

however, Tucker reponded. “I would say no, you don’t [ask

questions in that situation]?’ After a five minute court ad

journment, Dr. Tucker, in resuming his evidence, retracted

his statement. “Questions asked by the district surgeon,”

he said, “are not banned in the security offices?’ He fur

ther claimed that, “at all times I have always had all the

co-operation necessary from the security police. When we

require information and when we require things to be

done, then they are done.”22

If Dr. Tucker’s assertion about the co-operativeness of

the police was correct, then it threw on onus of respon

sibility for the fatal pretoria journey directly on to his

shoulders. Tucker’s evidence shows that he deferred

without protest to Col. Goosen’s refusal to allow the de

tainee local hospitalisation. Dr. Tucker consented to

Goosen’s alternative proposal tht the patient be

transported to Pretoria by motor vehicle. The only aspect

the arrangements he claimed to have insisted upon was

the need for a soft mattress. Tucker stated later, however,

theat he neither saw it as his responsibility to check the

vehicle used nor reassure himself that there was infact a

mattress, blankets, and a pillow for the patient. Further

more, he did not consider it part of his responsibility to

insist that Biko be accompanied by a medical attendent

or his medical records.23

On the crucial matter of the state of Steve Biko’s health

the day before his death, Dr. Tucker had written that he

found no positive sign of organic disease and that the pa

tent’s condition was satisfactory. Under questioning

Tucker admitted that he had found the patient lying on

the floor with forth at his mouth and hyperventilating.

He had found the patient weak in the left arm and

apathetic. He admitted that he knew of the extensor plan

tar reflex. Nevertheless, when challenged to admit that “in

this situation no honest doctor could have advised that

Biko’s condition was satisfactory?’ Dr. Tucker persisted.

“In the circumstances, [I] though it was,” he said.24

In his final submission made to the court on behalf of

the Biko family, Counsel Sydney Kentridge strongly

criticised the indifference displayed by Drs. Lang and

Tucker towards the patient. Their relationship to

Col. Goosen, he charged, “was one of subservience

bordering on collusion?’ And their behaviour carried a

September-December 1988

Excert From the Inquest

Kentridge : Why did you not ask the obvious question,

whether the man received a bump on the

head?

Tucker

: I did not ask it and that is all I can say.

Prins

: Did you ask Biko?

(magistrate)

TUcker

: No.

Kentridge : Was it not possible you were reluctant to em

barrass Goosen?

TUcker

: No.

Kentridge : Either from reading about it or from your

own experience have you no knowledge that

the police assault people in custody?

TUcker

: I have. (Further answer inaudible).

Kentridge : But on that occasion you did not ask?

Tucker

: No, I did not. Where persons are brought to

me for examination my report is completed

on a special form. This is all I am required

to do. This history was given to Dr. Lang...

The restraint [on the morning of 7

September] could have resulted in the

damage.

Kentridge : You accept it as a fact, what Goosen told

you?

Tucker

: May I put it this way? If am called to see a

patient and he has a cut onhis head, then I

am interested in treating him and not in how

he got the cut.

(Inquest into the death of Steve Biko,

Proceedings, in Bernstein, Biko, p. 85)

significance beyond the present case. For “the medical pro

fession’s general reputation has led couts in the past,

whenever an issue arose as to whether a prisoner seen by

a doctor had been assaulted or not, to place great if not

absolute reliance on the district surgeon’s findings?’ Ken

tridge submitted that in this case “the proved facts show

that not only can the court not rely on the evidence of

Drs. Ivor Lang and Benjamin Tucker, but that an analysis

of the evidence show that they joined with the security

police in a conspiracy of silence?’ The very best that could

be said, he argued, was that “they turned a blind eye?’ Ken

tridge concluded that the doctors’ neglect of the patient’s

interests in deference to the requirements of the security

police “was a breach of their professional duty, which may

have contributed to the final result?’25

Response of South African Medical Dental

Councils

The South African Medical and Dentral Council

(hereafter referred to as the Medical and Dental Council)

is South Africa’s principal regulatory body controlling the

medical and dental professions. The thirty-four member

43

statutory body has the power, under the 1974 Medical,

Dental, and Supplementary Health Service Professions

Act, to license and control the trainings of the members

of the medical and dental professions and to uphold

ethical medical standards. The Medical and Dental Coun

cil is vested with quasi-judicial powers to regulate the con

duct of the medical and dental professions, including the

authority to institute an inquiry into any complaint,

charge, or allegation of improper or disgraceful conduct

against any person licensed as a practitioner by the coun

cil. The Medical and Dental Council has the power to im

pose penalties, including striking the person off the

register of licensed practitioners.26

The 1974 Act does not define improper or disgraceful

conduct. The Medical and Dental Council has the discre

tion to define such conduct, and, periodically, the coun

cil makes rules specifying the acts and omissions for which

it may take disciplinary steps against a registered member

of the medical or dental professions. For instance, in 1976,

the year prior to Steve Biko’s death, the Minister of Health

approved, infer alia, a rule prohibiting a practitioner from

issuing a medical certificate unless he or she is satisfied

from personal observation that the facts are correctly

stated therein, or has qualified the certificate with the

words “as 1 am informed by the patient!’27 In a 1985

Supreme Court review of the powers and duties of the

Medical and Dental Council, the presiding judge describ

ed the council as “truly a statutory custosmorum of the

medical profession, the guardian of the prestige, status,

and dignity of the profession and the public interest, in

so far as members of the public are affected by the con

duct of members of the profession.. .”28

Despite its clearly crucial disciplinary role, the Medical

and Dental Council was to prove wholly inadequate for

the task before it. In January 1978 the council received

from Magistrate Prins a copy of the inquest proceedings

involving Lang and Tucker’s evidence. At the same time,

the Medical and Dental Council was set a formal “com

plaint” by Mr. Eugene Roelofse, ombudsman for the

South African Council of Churches. Mr. Roelofse’s com

plaint posed a series of questions regarding the ethical

conduct of Drs. Lang and TUcker.29 Though Mr. Roelofse

did not formulate specific charges against the physicians,

the Medical and Dentral Council’s president treated the

matter as a complaint within the meaning of the Act. He

directed the council registrar to refer the complaint, with

the portion of the inquest record, to the council’s Medical

Committee of Preliminary Inquiry (hereafter referred to

as the inquiry committee).30 He also directed the registrar

to send copies of these documents to Drs. Lang and

TUcker and to ask them for an explanation.

In response the state attorney, acting on behalf of

Drs. Lang and TUcker, requested a postponement of the

inquiry, pending the outcome of civil proceedings laun

ched by members of the Biko family.31 When the Medical

and Dental Council’s registrar insisted on an explanation

from the doctors, the state attorney replied that the com

plaint lacked the specificity necessary to initiate action

by the inquiry committee and that it was defective in cer

tain respects. The two doctors then applied to the Supreme

Court for a ruling to this effect. The presiding judge

dismissed the doctor’s application.'2

On April 24, 1980 the five-member inquiry committee

met to consider the inquest record and other materials.

The inquiry committee resolved that the contents of the

documents be noted and, in a highly unusual move, the

committee released its findings to the press before the full

council had met to consider the resolution. In the South

African Medical Journal of May 17, 1989, the inquiry

committee announced that it had found no prima facie

evidence of improper or disgraceful conduct on the part

of the practitioners and that it had resolved that no fur

ther action be taken in the matter. Professor Gordon, one

of the medical assessors at the inquest, later described this

premature public release of the inquiry committee’s fin

dings as unprecedented in his 25 years of service as a coun

cil member.33

The Medical and Dental Council met on June 17, 1980

to consider the inquiry committee’s.resolution. At the

meeting two members, Professors Shapiro and Carlton,

attempted to convince the council that it should not con

firm the inquiry committee’s resolution; that there was

prima facie evidence of improper or disgraceful conduct

on the part of Drs. Lang and Tucker; and that a second

inquiry into their conduct should be held.34 Their mo

tion was put to the vote and defeated. The resolution of

the inquiry committee was confirmed by a majority of

eighteen votes to nine.35

The Medical and Dental Council’s decision provoked

an uproar in the medical community.36 The medical

faculties of the Universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand disassociated themselves from the position

adopted by the council. The Board of tne Witwatersrand

Medical Faculty in Johannesburg unanimously adopted

a resolution expressing their deep disquiet at the coun

cil’s finding. The Witwatersrand faculty felt that there was

sufficient prima facie evidence to warrant a disciplinary

hearing, and warned that “the South African Medical and

Dental Council might have called into question its own

credibility as an objective and unbiased guardian of the

high standards of the medical profession in South Africa.’’

In addition the medical faculty expressed concern as “to

the possible effects of the decision of the Medical Coun

cil on the future treatment of prisoners and detainees by

the authorities!’ The faculty went on to endorse the

Guidelines for Medical Doctors Concerning Detainees and

Prisoners, adopted by the World Medical Association

(WMA) in Tokyo in 1975.37

September-December 1988

The Witwatersrand medical faculty noted in its resolu

tion that the Medical and Dental Council, as the pur

ported watch-dog of the ethics of the profession, had been

zealous, even over-zealous, in the severity of the

punishments meted out in the past for even minor infr

ingements of medical ethics. Yet, in the present case, they

found it difficult to accept “that the council [had] ap

plied its collective mind to the problem of the Biko doc

tors in a purely objective and dispassionate way?38

Despite these protests and the indications that medical

associations in other countries were beginning to review

their ties with South African medical organisations, the

Medical and Dentral Council announced in October 1980

that its dismissal of the complaints against the Biko doc

tors was final and irreversible.39

The Medical and Dental Council’s controversial deci

sion forced critics to turn to the Medical Association of

South Africa (MASA), a non-statutory professional

organisation whose membership is purely voluntary.40

On June 18, 1980 Dr. Jonathan Gluckman, a pathologist

who had attended the post mortem on Biko on behalf of

the deceased’s family and a member of MASA’s Federal

Council, presented the association’s secretary general, Dr.

C. Viljoen, with a letter signed by 38 association members.

The signatories called for an inquiry to determine whether

Dr. Benjamin TUcker “... is a fit and proper person to

continue to be a member of this Association.” (Dr. Lang

was not a member of MASA.)41

In accordance with MASA’s Articles of Association,

Dr. Wiljeon referred the letter with copies of a portion

of the inquest record to the Cape Midlands Branch of the

association where Dr. Tucker held membership. Unlike the

Medical and Dentral Council, MASA lacked wide powers

of inquiry and punishment. Its powers of censure ov6r

its members were limited to that of expulsion, with the

initiative for this lying at the branch level and not at the

national level. In this instance, the Cape Midlands Branch

notified the MASA’s Federal Council two weeks later “that

a charge of unethical conduct against Dr. TUcker could

not be sustained” and advised that “the case now be closed?

The executive committee of MASA’s Federal Council

met in August 1980 and accepted this recommendation.

The committee also resolved that the findings of the

Medical and Dental Council and its inquiry committee

“be noted? Even so, the Federal Council’s executive com

mittee did raise questions concerning the conformity of

the medical care received by Biko with the WMA guide

lines in the Declaration of Tokyo. The executive commit

tee acknowledged that the lack of conformity probably

contributed to the “subsequent unfortunate course of

events? Nevertheless, the executive committee shifted the

focus of its questioning away from the conduct of the doc

tors to the possibly restrictive effects of existing laws and

regulations upon doctors operating within the prisons.42

September-December 1988

Two additional resolutions adopted by the Federal

Council’s executive, committee alluded to the growing

domestic and international controversy surrounding the

response of the medical establishment to the charges

against the Biko doctors. The committee defended the ‘in

tegrity and bona Tides’ of the members of the Medical

and Dental Council and its inquiry committee, and

MASA’s Cape Midlands Branch. They also expressed

MASA’s satisfaction that the decisions of these bodies

“had in no way been subject to outside influence and that

there had not been any attempt at a ‘cover-up’ with regard

to the conduct of the practitioners concerned?

In contrast, the Federal Council’s executive committee

viewed the critics of these bodies as proceeding on the

basis of flawed newspaper reports, “which were frequently

incomplete, biased, or based on political rather than

ethical or humane considerations? The executive commit

tee concluded that if evidence of improper or disgraceful

conduct could not be found by the Medical and Dental

Council’s inquiry committee, the members of the MASA

executive committee “could not be expected to submit to

pressure or to violate their own consciences by laying a

charge simply to satisfy the demands being made!’43

To members of the South African medical community

anxious to investigate fully the conduct of the Biko doc

tors, it appeared That the medical establishment had closed

ranks. This impression was strengthened by statements

published in September 1980 in the South African Medical

Journal, the official journal of MASA.44 The journal

contained a statement by the Federal Council’s executive

committee recapitulating the discussion and resolutions

passed at its August meeting. The chairman of the Federal

Council, Dr. J. N. de Klerk, pointed out in the journal

that three separate medical bodes independently had

reached the same conclusion, namely, “that in light of the

evidence available to them, and taking into consideration

the particular circumstances surrounding this whole mat

ter, the doctors were not guilty of negligence or of im

proper or disgraceful conduct!’ For those colleagues who

still disagreed with these findings, de Klerk had only cold

comfort. “Manifestly!’ he concluded, “the [Medical and

Dental] Council itself is not able to reopen the matter,

while the ethical committees of the MASA are substan

tially in agreement with its findings!’45

MASA’s stance provoked a spate of resignations among

its members most prominently that of Professor Stuart

Saunders, then principal-designate of the University of

Cape Town, and Professor Frances Ames, head of the

Department of Neurology at the same university. In a Tet

ter to the editor’ of the South African Medical Journal,

Professor Saunders challenged MASA’s Federal Council

to state openly the implications of its position: namely,

that medical doctors should acquiesce in decisions taken

by the police and accept that there are considerations other

45

than the patient’s welfare to be taken into account in

treating a prisoner. Professor Gordon, in announcing his

decision not to stand for re-election for the executive com

mittee of the Federal Council after 25 years of service,

characterised the actions of the Medical and Dental Coun

cil and the MASA executive committee in exculpating the

doctors as “an act of impertinence and arrogance!’46

The resignations and negative publicity eventually

produced a response from MASA’s Federal Council.

Dr. Jonathan Gulckman persuaded it to form a commit

tee to inquire into the ethical issues raised by the medical

treatment of Biko. The Federal Council also agreed to ap

proach the government on the matter of the medical treat

ment of prisoners, especially those detained under the

security laws, and to establish a code of conduct for

medical practitioners working under these circumstances.

In a statement to the press announcing these decisions,

Dr. Gluckman expressed his personal distress at the posi

tion adopted by the Medical and Dental Council. He

acknowledged, as a member of MASA’s Federal Coun

cil, “that mistakes have been made by us in MASA in the

handling of the Biko matter!’ Dr. Gluckman said that it

was essential “in the public interest and in the interests

of the reputation and the good standing of the medical

profession as well as in the interests of the prisoners that

these mistakes be rectified!’47

The Ad Hoc Committee appointed to consider certain

ethical issues (hereafter referred to as the ad hoc commit

tee) reported to MASA in June 1981. Investigations by the

ad hoc committee were limited by its lack of subpoena

powers and the fact that Dr. Lang and Dr. Tucker did not

participate in any of the committee’s proceedings.48 In

addition, the police denied the ad hoc committee permis

sion to examine the Walmer police station cells where Steve

Biko had been held. The ad hoc committee’s report,

however, critically reviewed the available evidence concer

ning the doctors’ conduct and openly disagreed with the

findings of the Medical and Dental Council.49

The report of the ad hoc committee encouraged those

doctors who were dissatisfied with the Medical and Den

tal Council’s decisions. Five doctors subsequently lodg

ed with the council a detailed series of charges and com

plaints concerning the conduct of Drs. Lang. Tucker,

Hersch, and Keeley. Appended to the document was a list

of sixteen cases, dating from 1974 through 1980, involv

ing similar instances of improper or disgraceful conduct

by medical practitioners, along with the sentences imposed

by the council’s disciplinary committees.50 A month later,

in March 1982, five other doctors, together with the

Transvaal Medical Society (now the Health Workers’

Association), a voluntary organisation of mostly black

doctors and allied personnel, lodged a separate list of

complaints against Dr. Lang and 'Ricker.51 Both sets of

complainants referred extensively to the full record of the

46

inquest proceedings in detailing and motivating the

charges against the doctors.

In March 1983 the Medical and Dental Council’s in

quiry committee met to consider the allegations. The in

quirycommittee resolved “that all material evidence which

had been submitted in support of the present complaint

had also been considered by the committee and the council

previously, and that no new material evidence had emerg

ed such as warranted the rescission of the council’s

previous resolution’’. Accordingly the inquiry committee

resolved that no further action should be taken against

the doctors. A month later the Medical and Dental Coun

cil confirmed this resolution, once again rejecting a mo

tion proposed by Drs. Shapiro and Carlton to the

contrary.52

Faced with this rebuff, the complainants were forced

to seek Supreme Court review of the matter. They peti

tioned the Court to set aside the resolutions of the Medical

and Dental Council and its inquiry committee, and to

direct the council to hold a new inquiry into the allega

tions of improper or disgraceful conduct on the part of

Drs. Lang and Tuckty. The petitioners argued that it was

in the public interest and in the interest of South Africa

that the applicants* complaint be properly heard. “The

international reputation... of medical practitioners

within the Republic,” they noted, “has been tarnished by

the fact that the [council] had failed properly to get to

grips with an inquiry' into the conduct of the medical prac

titioners whose conduct is in issue!’53

In January' 1985 the Court ruled in the petitioners’favor. It found that the inquest proceedings did support

the charges and complaints of the applicants, and that

there wasprima facie evidence of improper or disgraceful

conduct on the part of Drs. Lang and Tucker. The

presiding judge referred, inter alia, to Dr. Lang’s false

medical certificate which represented an apparent breach

of one of the Medical and Dental Council’s rules of ethics.

The inquiry council and its inquiry committee, in con

cluding otherwise, had misdirected themselves. The Court

also found that the applicants, as medical practitioners,

did have locus standi to approach the Court, because the

purpose of the 1974 Act governing the activities of the

council was intended not only to protect the public vis-avis the medical profession but also the reputation of the

medical profession itself.

The Court then issued an order repudiating the resolu

tions adopted by the Medical and Dental Council and its

inquiry committee in 1983. It directed the inquiry com

mittee to resolve “that the evidence furnished in support

of the aforementioned complaints discloses prima facie

evidence of improper or disgraceful conduct, or conduct

which when regard is had to the respective professions of

[Drs. Lang and TUcker] is improper or disgraceful!’ It fur

ther directed the council to establish a disciplinary com