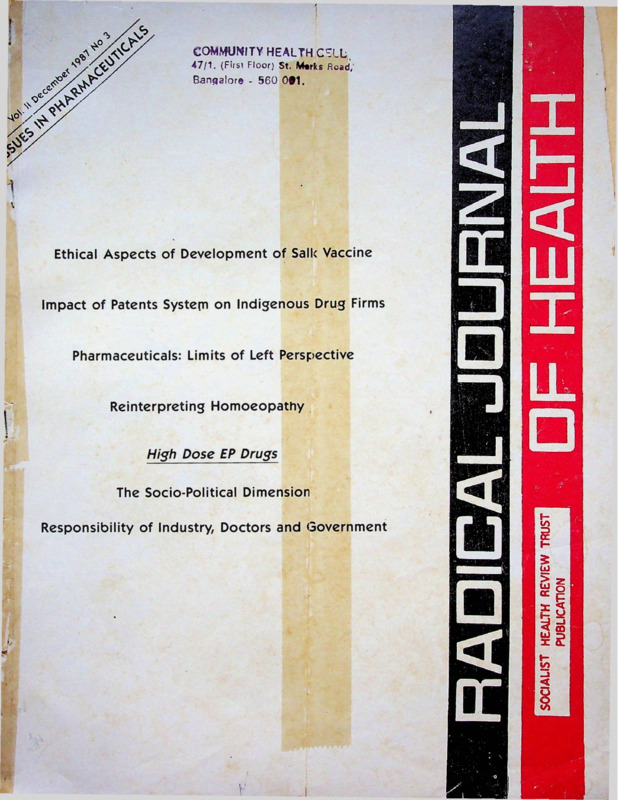

Radical Journal of Health 1987 Vol. 2, No. 3, Dec. Issues in Pharmaceuticals.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL,

47/1. (First Floor) St. Merks Road,'

Bangalore - 560 001.

Ethical Aspects of Development of Salk Vaccine

Impact of Patents System on Indigenous Drug Firms

Pharmaceuticals: Limits of Left Perspective

Reinterpreting Homoeopathy

High Dose EP Drugs

The Socio-Political Dimension

Responsibility of Industry, Doctors and Government

Working Editors:

Volume II

Amar Jesani, Manisha Gupte,

Padma Prakash, Ravi Duggal

ISSUES IN PHARMACEUTICALS

Editorial Collective:

Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (A P), Imrana Quadeer,Sathyamala C (Delhi), Dhruv Mankad

(Karnataka), Binayak Sen, Mira Sadgopal (M P), Anant

Phadke, Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar, Srilatha

Batliwala (Maharashtra) Amar Singh Azad (Punjab),

Smaraiit Jana and Sujit Das (West Bengal)

All Correspondence:

Radical Journal of Health

C/o 19 June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay-400 050 India.

December 1987

No 3

49

Editorial Perspective

PHARMACEUTICALS- LIMITATIONS OF LEFT PERSPECTIVE

Anant R S

52

IMPACT OF PATENT SYSTEM IN INDIA ON INDIGENOUS DRUG FIRM?

Sudip Chaudhun

55

High Dose EP Drugs I

RESPONSIBILITY OF INDUSTRY, .DOCTORS AND GOVERNMENT

Amitava Guha

60

High Dose EP Drugs II

THE SOCIO-POLITICAL DIMENSION

Imrana Qadeer

63

Printed and Published by

Amar Jesani for

Socialist Health Review Trust.

Registered Address: C-6 Balaka, Swastik Park,

Chembur, Bombay 400 071.

POLIO, POLITICS, PUBLICITY AND DUPLICITY

ETHICAL ASPECTS OF DEVELOPMENT OF SALK VACCINE

Allan M Brandt

Printed at:

Bharat Printers, Shiv Shakti,

Worli, Bombay.

BEYOND MEDICAL SOLUTIONS

Guy Poitevin

Book Review

70

Dialogue

75

Annual Subscription Rates.Rs.. 30/- for individuals

Rs.. 45/- for institutions

Rs. 500/- life subscription (individual)

US dollars 20 for the US, Europe and Japan US

dollars 15 for other countries.

We have special rates for developing countries.

SINGLE COPY: Rs. 8/-

(All remittance to be made out in favour of Radical

Journal of Health. Add Rs 5/- on outstation cheques)

REINTERPRETING HOMOEOPATHY __

Ch V Subba Rao

Editorial Perspective

Pharmaceuticals: Limitations of Left Perspective

WHAT are the issues that arise when we are discussing the

relationship between pharmaceuticals and health? There are

three types of issues. First, the issue of the general relation

ship between pharmaceuticals and health. Second the role

of pharmaceuticals in capitalism, and especially monopoly

capitalism, as well as that in state socialism and revolutionary

socialism. Third, the objective and the standpoint of the Left

movement in India as regards this issue of pharmaceuticals

and health. Let us take a brief overview of the various sub

issues involved in these three aspects of this problem.

Contrary to what the drug industry or the technocratic

ideology would like us to believe, drugs have played a

marginal role in improving or maintaining the health of the

people. In a way this is obvious because it is clear that health

status basically depends upon food, water, sanitation, en

vironment, working-conditions and cultural atmosphere.

Moreover, until recently, therapeutic efficacy of medicines

was very low. In ayurveda, the ancient Indian approach to

health and disease, what is notable, (given the primitive tools

of enquiry available in those days and given the dominance

of idealist tradition), is its materialist outlook—not much

scope for spirits and the like. It is however a controversial

issue as to what extent ayurvedic medicines have been effec

tive and safe. That they have been used for hundreds of years

does not necessarily mean that they have been effective and

safe. In the west things were probably worse. Medical pro

fessionals had very few useful medicines to offer to the

patients (less than the folk-people had) till as late as late 19th

century. Many of the remedies were of the nature of blood

letting, branding and the like or use of corrossives or other

drastic and harmful substances as medicines.

The era of safe and effective antimicrobials, anti-biotics,

started from 1930s and most of the antibiotics and other

‘wonder drugs* came after the second world war as a part

of the third industrial revolution and post-war restructuring

of the imperialist system and its boom. By this time, however,

most of the major infectious diseases in the west had already

declined substantially. Now it is well-known in informed

circles that modern drugs have thus not played an impor

tant role in the improvement of the health-status in the west.

It is basically the improvement in the general living standards

(food, sanitation, housing, work, education, etc.) which did

the job. In the developing capitalist societies, these power

ful catalytic agents—the modern pharmaceuticals including

most importantly the vaccines—have hardly realised their

potential because the socio-economic conditions are inimical.

This can be seen from the case of megapolis like Bombay.

Here we have drugs and doctors (including specialists)

available in every lane, but tuberculosis, leprosy, venereal

diseases and even polio show to sign of the respite. China,

which is a quite comparable out of the capitalist straight

jacket has shown how modern drugs can be a powerful aide

in the rapid control over the scourge of infectious diseases

when social cpnditions are favourable for such a control.

The so-called ‘diseases of industrialisation’ (which are the

diseases of monopoly capitalism and the culture it breeds—

cardiovascular diseases, injuries due to accidents, cancers,

December 1987

diseases due to obesity and psychiatric problems—cannot be

cured with drugs. On the contrary, the overuse of drugs in

such disorders lead to a number of iatrogenic health

problems.

It may be argued that the above is a rather simplistic state

ment. Yes, indeed, it is; it being a brief statement of a stand

point about a historical phenomenon or trend. There are

some phenomenon which do not quite fit into this scheme.

But that does not alter the overall picture. Secondly, to point

out the marginal role of medicines in improving health status

of population is not a criticism of modern medicines but

of technocratic, self-servicing ideologues who overplay the

role of medicines. There is no doubt that modern medicines

have a tremendous catalytic potential and even in absence

of favourable social conditions, they have made human life

more tolerable that what it could otherwise be. But its wrong

to attribute more than this to medicines.

The question of the role of non-allopathic medicines is

a perplexing one. Homeopathic and allopathic medicines

have entirely different presuppositions, are of entirely dif

ferent nature, both qualitatively and quantitatively; yet both

help in different .degrees and instances the human body in

its recovery from illness. It is a theoretical puzzle as to how

this can happen. This discussion cannot, however, be

separated from the one about different disciplines of medical

care—homeopathy, ayurveda, unani and others. Secondly,

this question is also related to the question of the very

method of science. Statistical criteria are used to decide the

efficacy of medicines in allopathy. How can this be done in

homeopathy and ayuveda when their basis is that of indi

vidualisation? Is there a way out? Is the very notion of scien

tific criteria as used in allopathic science open to question?

Is there any alternative scientific method? Can there be?

There are a long list of such questions which do not seem

to lead us anywhere.

One thing is, however, definite. Research into these systems

needs to be given more resources—financial and otherwise.

At the same time, unless the efficacy and safety of the nonallopathic medicines have been proved through research, by

some intelligible criteria proposed by the authorities in these

systems, these drugs should not be allowed to be commer

cially produced.

Capitalism and Pharmaceuticals

Drug technology was one of the branches of technology,

which stagnated for quite sometime even after the advent

of the industrial revolution in Europe. The knowledge of

human body in health and disease and the development of

chemistry was too meagre for quite some time. It is only in

monopoly capitalism—the advanced stage of capitalism—

that enough resources could be pumped into research in these

complicated sciences and it is only then that diagnosis and

treatment of diseases could flower into a discipline solidly

based on modern science. Modern pharmaceuticals is essen

tially a product of monopoly capitalism. This same mono

poly capitalism has, however, at the same time, become an

49

oostacle in (he path of the full and proper use of modern

pharmaceuticals. Monopoly drug companies restrict produc

tion and jack-up prices to ensure monopoly profits by using

methods characteristic of monopoly capitalism, a lot of

irrational and even harmful drugs are pushed onto the con

sumers. In India and other peripheral countries, this occurs

in a very crude manner wherein the market abounds in

useless, irrational, harmful products which fetch higher rates

of profits. This is at the expense of essential drugs which

are at least under some price-control. In the rest, this

phenomenon takes place in a more subtle form through a

technocratic consumerist ideology of ‘pill for every ill’.

The full flowering of the science of pharmaco-therapeutics

is also adversely affected by monopoly capitalism. A lot of

resources are wasted in inventing ‘me-too’ drugs which have

no significant advantage over the existing ones, but which

can be marketed as ‘new and better’ through aggressive

monopolistic marketing techniques. Social resources are also

wasted in attempts to prove through ‘scientific research’, really

harmful drugs as safe, or useless drugs as very effective.

•Monopoly multinational drug companies represent a

classic case of how modern imperialism operates. These

monopoly MNCs have on the one hand introduced the fruits

of the development of modern science of pharmacotherapeutics into the third world countries. On the other

hand, their monopoly, imperialist interests demand that a

part of the surplus value created in the drug industry be

pumped off to the imperialist centre; that the drug industry

in the peripheral countries be dependent on the imperialist

centre so that this sector remains one of the channels of more

profitable investments and easier markets. The methods

employed to achieve this aim are scandalously bad-produc

tion and marketing of the most irrational, irrelevant, and

even harmful products at rapaciously high prices through

blatantly unethical marketing practices; and the suppression

of development of indigenous technology by recourse to ‘fair’

and foul methods characteristic of monopoly capitalism. The

results are more disastrous than they are in the west, since

the wastage of and suppression of resources means too much

pressure on a weak economy and the impact of cheating and

exploitation is much more significant for the poor people

who constitute the majority in these peripheral capitalist

countries. The contrast between the potentiality of using

modern science and technology for the betterment of

humankind and the reality of a stunted, distorted develop

ment is much more poignantly seen in case of the drug in

dustry in the peripheral capitalist countries.

Contraceptives as a group of drugs need a special men

tion. The invention of the birth-control pill is regarded by

many as one of the important milestones in the path of

women’s liberation. In reality it is only a defence mechanism

for women in the world of patriarchal capitalism in which

safe, effective male contraceptives are neither developed nor

used adequately. Contraception is considered as the woman’s

responsibility. The availability of the effective pill in a society

wherein women are seen as objects of sexual gratification

for men has also meant women’s bodies being available

‘anytime’ without the fear of them getting pregnant. This

is convenient for patriarchal men since they can achieve the

twin benefit of free sex, and small number of children,

without any responsibility or botheration of use of

contraceptives.

50

For the women in peripheral countries and of the ethnic

minorities in the imperialist centres, hormonal contracep

tives are becoming in addition, a burden on their already

poor health. Patently unsafe injectable contraceptives and

subdermal implements have given the capitalists, patriarchal

state a powerful instrument to enforce its programme of

population-control in these countries—at the expense of

health of the poor women. Pharmaceuticals which are sup

posed to enhance feminity are another example of the crude

sexism practised by the drug industry.

Pharmaceuticals in Socialism

Human beings would of course continue to fall ill under

socialism and communism. The pattern of diseases would,

however, be quite different from those in undeveloped

capitalism or in monopoly capitalism since this pattern is

decided primarily by the nature of social production and the

set of relations encompassing it. It would be an idle specula

tion as to what kind of health problems would exist then

and which drugs would be used. All that we can say with

certainly is that in socialism and communism, there will be

less and less of illnesses and hence less and less necessity of

use of drugs in diseases.

In ‘existing socialisms’ alias state socialist societies (USSR,

China, etc.) conditions are, of course, quite removed from

this ideal. But the use of pharmaceuticals in these countries

is not vitiated by the narrow needs of a profit-hungry drug

industry and hence is quiteTational. But there are some pro

blems. For example, the widespread use of the injectable contraceptive,-Net-En in People’s Republic of China shows that

patriarchal relations are present there to quite a substantial

extent. In more developed societies—USSR and countries in

the eastern block, the disease pattern is not qualitatively dif

ferent from that in the capitalist west. This, however, does

not mean that drugs are overused and misused like in the

west since there is no profit-mongering drug industry in these

societies. It would be interesting to study the precise nature

of use of pharmaceutical in these societies, whether, and to

what extent there is any irrationality in the production and

use of drugs and why.

Standpoint of Left Movement in India

The Left parlies and groups have criticised foreign drug

companies as part of their anti-imperialist standpoint.

During last six or seven years a lot of concrete work has been

done to demonstrate how specifically MNC drug companies

exploit and cheat the Indian people and how they thwart the

Indian sector. There are, however, two problems in these

criticisms—firstly, most of this work has been done by Left

intellectuals as part of their research project or by Left acti

vists, as part of the broader ‘democratic’ science or healthgroups to which we belong. This has put certain limitations

on the standpoint that is expressed in these analyses and has

even put limitations on the very thinking of Left activists.

There is a need to a pause and think about these limitations.

In certain academic institutions, financed by the govern

ment, there exists a liberalism among decision-makers and

hence it is easier to get a research-project to study the impact

of MNCs on the Indian drug industry. This liberalism is in

tune with the interests of the Indian state; because such

Radical Journal of Health

studies fall within the limited anti-imperialist standpoint of

the Indian state. The interests of the Indian bourgeoisie

demand that MNCs be pressurised into allowing more and

more leeway to Indian capital to exploit the Indian people.

Studies focussing on the negative role of MNCs are, therefore,

even encouraged by the Indian state. Such studies unearth

a lot of valuable anti-imperialist material which can be used

by people’s movements in their thorough-going, revolutionary

anti-imperialist struggle.

But a more or less exclusive focus in these studies on the

role of MNCs by omitting a critique of the Indian sector

is more helpful to the non-revolutionary anti-imperialist

struggle of the Indian bourgeoisie. There is comparatively

less concrete research in such studies on the anti-people role

of Indian companies—and of the public sector. A critique

of the Indian sector does not necessarily mean neglecting

the distinction between MNCs, Indian private companies—

(monopoly and non-monopoly) and the public sector. But

a comprehensive critique is perhaps not encouraged. It is no

accident that a majority of these studies directly or indirectly

financed by the Indian state omit the Indian sector from their

critique.

Popular education and propaganda, based on these studies

have an ideological, political role of limiting the critique to

only the MNCs. The fact that many Left analysts have a

limited, anti-imperialist (understood in a narrow sense)

political perspective which excludes an important role of a

critique of the Indian sector, also helps to sustain this un

necessarily narrow focus. In terms of demands also, the focus

of most of Left analysts is limited to -the demand for na

tionalisation of MNCs. In our strategic demands, we should

ask for*nationalisation without any compensation and with

workers’ control/democratisation in the nationalised in

dustry. These strategic demands are for the public education

of what is possible in the coming stage of the revolution;

and hence the fact that the health movement is too weak

today, is no argument including this strategic perspective in

our study and propaganda.

Criticisms mounted as part of a health or science or con

sumer group have an advantage in that such criticisms bring

into focus the question of irrational and hazardous drugs,

SUBSCRIPTION RENEWALS

misleading propaganda by the drug companies about the

efficacy and safety of their drugs and so on. Here again,

misdeeds of Indian companies are generally not mentioned.

But the demand for banning of irrational and hazardous pro

ducts, is such that no concession can be given to the Indian

sector whose performance on this score has been no better.

As a part of the ‘democratic* health/science/consumer

movements, Left activists have participated in bringing

forward the medical (sometimes feminist) issues and

demands. But many such groups do not take a political stand

against even imperialism; leave aside Indian capital even

though the concrete demands made by such groups and their

implications are many times anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist.

But a lack of a clear political anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist

stand sometimes becomes a hinderance in the progress of

analysis in such groups. Part of this problem is due to the

fact that people’s movements and hence the political culture

in such anti-establishment groups has not advanced enough.

But part of the problem is also due to the fact that the

perspective of the Left activists working in such groups is

limited to a purely anti-imperialist standpoint, (understood

in a narrow sense). That is why even among Left-journalist,

analyses about the drug industry from a comprehensive

standpoint are a rarity; most of the writings being from

purely anti-MNC viewpoint.

The editorial perspective in RJH is meant to delineate

various issues (in a somewhat comprehensive fashion)

germane to the theme chosen for the current number of RJH

and to make editorial comments on some of them. In the

foregoing, I have merged this two-step operation into a single

step by making a summary-statement of a certain viewpoint

on the three types of major issues which were thought to be

central to the theme of this current issues of RJH. There are,

of course, viewpoints different from the one outlined above.

It is hoped that there will be further discussion and debate

on these issues. Obviously, in this number of RJH it has been

possible to cover only some of the issues.

Anant R. S.

50, LIC Quarters,

University Road,

PUNE - 411 016.

MEDICO FRIEND CIRCLE PUBLICATIONS

Is this your last subscribed issue? A prompt renewal from

you will ensure that your copy is mailed directly from the

Press. Many of our issues have sold out fast! So book your

copies by renewing your subscription now!

Medico Friend Circle Bulletin (Monthly):

Annual Subscription: Rs 20

Our new subscription rates:

Anthologies:

For individuals—Rs. 30/- (four issues)

For institutions-Rs. 45/- (four issues)

Foreign subscriptions: US $ 20 for US, Europe and Japan

US $ 15 for all other countries

(special rates for developing

countries)

Life subscription: Rs. 500/-____________________ _____

D.D.s, cheques, IPOs to be made out to RADICAL JOURNAL

OF HEALTH. Please write your full name and correct

address legibly. And please'don’t forget to add Rs. 5/- on

outstation cheques.

December 1987

In Search of Diagnosis

Health Care: Which Way to Go

Under the Lense

Rs 12

Rs 12

Rs 15

Bulletin subscriptions to be sent to C Sathyamala,

F-20 (GF), Jangpura Extension, New Delhi 110 014.

Orders for the anthologies to Dhruv Mankad,

1877 Joshi Galli, Nipani, Belgaum Dist, Karnataka.

51

Impact of Patent System in India on Indigenous Drug Firms

sudip chaudhuri

A demand is often made by certain quarters to modify the Patents Act of 1970 to make its provisions less restrictive

for the patentees. This paper examines the experience under the Patent and Designs Act of 1911 to argue that

such a change will go against indigenous efforts to develop processes and manufacture drugs.

THE objective of this article is to briefly relate the experience

of the indigenous drug firms with the Patents and Designs

Act. 1911 in the context of the Patent Act, 1970 which replac

ed the former in 1972.

The Patent and Designs Act, 1911 did not categorically

state what was patentable.1 The interpretation followed by

the Patent Office was that any new process for manufacturing

a drug (whether old or new) was patentable. A new drug was

also patentable provided the process of manufacture was

described in the patent. The process, however, in such a case

was not required to be new.2 Under the Act of 1911, the in

digenous firms have been legally prevented from manufac

turing most of the new drugs introduced by the transnational

corporations, during the life of the patent secured by the lat

ter, i c, for 16 years, which could be extended to a maximum

of another 10 years if the working of the patent had not

hitherto been sufficiently remunerative to the patentee3 This

had been possible because, as N R Ayyangar who was ap

pointed by the Government of India to examine the patent

law in India observed, the patentee, while patenting a new

drug, could describe all the known and possible porcesses.4

Actually the TNCs did so, as the experience of the indigenous

firms suggests.5 Even an old process, so specified by the

TNCs, could not be used by the indigenous firms for at least

16 years. The latter were also forbidden from processing a

patented drug into formulations or importing it.

The TNCs asserted their patent rights to proceed legally

against firms which tried to manufacture or import the

patented drug. Thus, Hindusthan Antibiotics Ltd (HAL),

a public sector firm, e g, claimed that it has developed an

indigenous process for manufacturing oxytetracyline Hcl. A

plant, in fact, was set up and production began in 1961

without any external technical help. In the same year a TNC,

viz, Pfizer too started manufacturing the same drug. HAL

had to suspend production as Pfizer took legal action alleg

ing infringement of patent rights.6 A TNC was importing

a drug at Rs 8 per 20 tablets. It sued an indigenous firm,

CIPLA, when the latter started importing it at Rs 2 per 40

tablets.7 Chloramphenicol and metronidazole are among the

other drugs for which the TNCs took legal action to pre

vent the indigenous firms from formulating.8

The manufacturing activities of the indigenous firms were

restricted to the old drugs or those new drugs for which it

could develop new processes of manufacture. We will now

discuss two cases which will give an idea about how the TNCs

could prevent or delay the use of these new- processes,

developed through indigenous efforts even w'hen these were

not specifically covered in the patents of the TNCs.

Haffkine Institute, a public sector firm, worked out a pro

cess for manufacturing tolbutamide from locally available

raw materials. A patent was also obtained. Unichem

Laboratories, an indigenous firm obtained a licence from it

and started manufacturing from 1961. Hoechst, a TNC,

52

however filed a suit claiming that tolbutamide had been

manufactured by Unichem on the basis of one of the for

mulas as mentioned in the former's patent granted earlier

in 1956. The judgement of the Bombay High Court delivered

in 1968 went in favour of Hoechst.9 What is important to

note here is that Hoechst won the case despite the fact that

its patent did not specifically mention Haffkine’s process.

What clinched the issue was that Hoechst’s description was

open-ended. One of the claims of Hoechst was, in the inter

pretation of the judge:

"Wide enough io cover all methods of eliminating sulphur from

thioureas (to manufacture Tolbutamide) whether desulphurisation

is effected by means of Hydrogen peroxide (as specifically mentioned

by Haffkine) or by the use of any other substance113 (phrases within

brackets ours).

Strange as it may appear, such widely worded claims were

permissible under the Act of 1911.

The same patent was also sought to be used for preventing

Bengal Chemical and Pharmaceutical Works (BCPW), an

indigenous firm, from manufacturing another drug, chlor

propamide. BCPW developed a new process for manufac

turing it and obtained a patent in 1959. But in 1961, BCPW

received a letter from Hoechst, alleging that the former had

infringed upon the latter’s patent under which Pfizer had

been given a licence to produce it. Denying the allegation,

BCPW sought legal action when it continued to receive such

threats. Hoechst and Pfizer, on their part, filed a suit in 1962

in the Calcutta High Court against BCPW.11 This time the

judgement went in favour of the indigenous firm. The judge

concluded that BCPW’s patent was an independent one, not

in any way influenced by Hoechst’s patent which, in fact,

did not relate to manufacture of chlorpropamide at all!

The case is quite revealing so far as the development of

indigenous technology and the role of patent legislation are

concerned. Hoechst’s patent did not refer to any specific

drug. It was for the broad group of sulphonyl Ureas. Forty

examples were given, but it was claimed that other com

pounds could be obtained easily from tKe general formula

and chlorpropamide was one of them. Hoechst, however, fail

ed to establish in the court that chlorpropamide could be

or had been produced on the basis of the process described

in their patent. Even an expert witness appearing for Hoechst

admitted that the information disclosed in the patent was

not enough to carry out the experiment. But Hoechst could

not give specific directions as to how to proceed. One of the

specifications, in fact, was found to be chemically incor

rect.12 Significantly, out of the 40 examples provided, none

referred to chlorpropamide.

One of the objectives behind the patent laws is to induce

the inventors to disclose the inventions (in return for the ex

clusive right of using the invention for a specified period)

so that knowledge may be diffused to facilitate further

technological progress. The above-mentioned case illustrates

Radical Journal of Health

how the TNCs used the Indian patent law existing then to

licence, but the foreign patentee offered to give (he licence

suppress indigenous growth. It is not only that Hoechst’s pa voluntarily on the basis of royalties to be fixed through

tent contained inadequate and misleading information which

negotiations. They demanded an absurdly high rate of royalty

prevents and distorts the diffusion of knowledge. The pa of 25 per cent. It took more than four years to reduce it to

tent was of a general type, supposed to cover a large and

10 per cent, which however was still higher than the limit

unspecified number of products/processes. Thus, other firms

of 5 per cent stipulated by the Reserve Bank of India. By

could be threatened with legal consequences even when their

that time the Haffkine Institute decided to abandon the

product was not at all connected with the patent. All the

scheme.-1 Again, another indigenous firm Neo Pharma In

patent disputes are not fought out in a court of law. A mere

dustries entered into a technical collaboration agreement with

threat may be enough deterrant in many cases. Significantly

an Italian firm for the technology to manufacture

enough, in 1968, before the court hearing started, Hoechst

chloramphenicol.

approached BCPW to settle the dispute ouside the court,

A licence was sought from Parke Davis, which held the

which however the latter refused.13

relevant patent in India. But whereas the subsidiary com

pany in India pointed out that the matter was beyond its

Compulsory licence: An indigenous firm intending to

manufacture a drug is required to obtain a licence from the jurisdiction, the parent company in the USA insisted that

Neo Pharma should first discuss with the local company, h

patentee concerned, if the process of manufacture to be used

took more than two years to decide as to who would

is covered by the patent. Under the Act of 1911, this was the

negotiate. At last when the negotiations started with the

requirement even if the process in question was well known

parent company, they did not formally refuse to grant a

(but even so had been mentioned in the patent as in the case

licence but simply sat over the proposal. Finally, when a com

of new drugs discussed above) or additional technical data

pulsory licence was sought for and was granted, Parke Davis

were necessary to implement the process and these had been

went to the court and obtained a stay order.-2

developed by, or obtained from, other sources. Obviously,

In fact, going to the court is a simple device the foreign

a patentee may grant a licence voluntarily to anyone on

patentees could employ. Even if ultimately the judgement

mutually acceptable terms. Compulsory licence is a licence

goes against the patentee, the applicant would normally be

granted by the Controller of Patents (or by the patentee as

directed by the Controller) or a non-patentee to use a pa prevented from using the compulsory licence during the

period of the court case. The longer the time taken to settle

tent on payment of royalties to the patentee. The Act of 1911

a case, the smaller will be the relative benefit to the appli

provided for the grant of compulsory licence in case of

cant for compulsory licence, because in any case after the

misuse or abuse of patent rights.14

expiry of the patent (normally 16 years) anybody was free

The Patents Enquiry Committee reported in 1950 that the

to use the patent. The hazards of obtaining a compulsory

foreign patentees did misuse or abuse their rights, e g, by

licence, which include legal battles, perhaps explain why so

importing the patented product rather than manufacturing

few applications for compulsory licence were made under

it here, fixing the prices at high levels, not allowing others

to manufacture the product even when it was not itself engag Section 23 CC. Till 1972. i c. when a new Act came into force,

there were only five applications for compulsory licence,

ed in manufacture.15 But, as the Committee observed, the

made by Hindustan Antibiotics Ltd (in 1959), Alembic

provisions regarding compulsory licences were “wholly

inadequate to prevent misuse or abuse of patent rights, par Chemical Works (1963). Dey’s Medical Stores (Manufactur

ing) (1960), Raptakos Brett and Co (1957) and Neo Pharma

ticularly by foreigners”.16 The Panel on Fine Chemicals,

Industries (1961).2’ The applications were ultimately

Drugs and Pharmaceuticals, appointed by the government

withdrawn in the first two cases. Compulsory licence was

also reported earlier in 1946 that not a single compulsory

refused by the Controller of Patents in the third case.24 The

licence could be obtained because of the wording of the rele

vant provisions.17 For example, under Section 22, a com controller granted compulsory licences in the last two cases.

pulsory licence could be claimed if “the demand for a

Patent System under Act of 1970

patented article is not being met to an adequate extent and

An important feature of the new Act, 197O25 is (he special

on reasonable terms”. As the Patents Enquiry Committee

commented, the Section unnecessarily also demanded that

provisions regarding drugs and a few other products. The

it has to be proved that as a result any trade or industry had

life of the drug (and food) patents has been reduced from

at least 16 years in (he previous Act to five years from the

been ‘unfairly prejudiced’. Obviously, in practice it appeared

very difficult to establish such a link.18

date of scaling.,26 or seven years from the date of filing of

complete specifications, whichever is shorter (sections 45 and

The provisions regarding compulsory licence (Sections 22

53), i e, for a maximum period of seven years. For other

and 23) were amended in 1950, following the recommenda

patents, the duration is 14 years. The new Act categorically

tions made by the Patents Enquiry Committee in its interim

states that drugs (and food and those manufactured by

report submitted in 1949.19 In 1952, an entirely new Section

chemical processes) can now be patented only for a new

(23 CC) dealing specifically with drugs (and food, insecticide,

germicide, fungicide, surgical or curative devices) was added.

method or process of manufacture, not for the products as

such (section 5). Hence in contrast to the previous situation,

Under this section, the Controller of Patents was empowered

to grant a compulsory licence to any applicant at any time

the indigenous firms can manufacture new drugs by old pro

cesses without violating the Act. Obviously, as before it can

unless there are ‘good reasons’ for refusing. The foreign

patentees, however, were still in a position to effectively pre continue to manufacture old drugs. Even in cases where new

drugs cannot be manufactured by known processes, and so

vent or delay the use of compulsory licence.

a new process is required, the indigenous firms are expected

The Haffkine Institute, e g, applied for a complusory

December 1987

53

to face less restrictions in developing such new processes. This

is because the firm discovering/inventing a drug can no

longer patent all the processes known to it even if these arc

new. For a particular drug, only one method or process—

the best known to the applicant—can be patented (Sections

5 and 10).27

Under Section 87 of the Patents Act, 1970. every patent

relating to processes for manufacturing drugs (or food or

chemical substances) has to be endorsed with the words

“Licences of right" after three years of the date of sealing.

This implies that anyone is automatically entitled to a licence

from the patentee for using the patent on payment of

royalties, the maximum rate being fixed at four per cent of

the ex-factory sales (Section 88). Even before expiry of three

years from the date of scaling, the controller is empowered

to grant a compulsory licence (and fix the rate of royalties)

if “it is necessary or expedient in the public interest" (Sec

tion 97). There is also a special provision in the Act of 1970

regarding the use of patents by the government. Any lime,

a patent may be used for official purposes, including those

of public undertakings. The maximum royally payable for

such a use, in case of drugs (and food) has been fixed at 4

per cent of the ex-factory sales (Sections 99 and 100).

It must be pointed out, however, that the actual use of a

patent by a non-patentee still remains hazardous. For exam

ple, under Section 87, as mentioned above, while the right

to obtain a licence automatically accrues after three years

from the date of scaling of a patent, it cannot actually be

used till the royalties are fixed either mutually or at the in

tervention of the controller. As before, the patentees can con

tinue to prevent or delay the use of their patents by others

by refusing to negotiate and then proceeding to the court

in case of any intervening action by the controller. This has,

in fact, happened in the case of each of the applications made

to the controller till now by three firms for fixation of

royalties. Incidentally, all these cases relate to products other

than drugs. In the case of the application made in March

1976 by Catalyst and Chemical India (West Asia), the con

troller fixed the rate of royally tentatively as per Section 88(4).

The patentee (1CI), however, went to the court and by the

lime the case came up for final hearing (July 1977) the pa

tent was about to expire (in August 1977). In the remaining

two cases, as the patentees approached the court, interim in

junction was granted and the Patent Office was directed not

to proceed with the applications of Titanium Equipment and

Anode Manufacturing Co and Coromandel Indag Products

made in September 1980 and July 1981 respectively. The two

patents in which Titanium was interested expired in February

1983 while the court case was still pending. Regarding

Coromandel, too, while the case is yet to be settled, one of

the patents has already expired in March 1982, w hile the other

is due to expire in February 1986.28

Despite such hazards, the Patents Act, 1970 appears, on

the whole, to be an improvement from the point of view of

the development of indigenous science and technology, com

pared to the previous situation. A demand is often made by

certain quarters to modify the present Act and make the pro

visions less restrictive for the patentees. If the experience

under the Act of 1911 is any guide, then such a change will

go against the indigenous efforts to develop processes and

manufacturing drugs.

54

Noles

[This paper was written in 1984 and hence does not contain any references

to later events.]

I. Report of rhe Patents Enquiry Committee (1948-50) (Delhi, GOI,

Ministry of Industry and Supply, 1950), p 64; N Rajagopala

Av yangar. Report on the Revision of the Patents Law (Delhi, GOI,

1959). p 20.

2. Av yangar. Report, pp 20. 34. 36.

3. See Section 14 and 15. "The Indian Patent and Designs Act 1911”,

reproduced in Patent Office Hand Book (Delhi. GOI. 13th ed, 1966).

4 A\yangar. Report, pp 34. 36.

5. See the evidence of K A Hamied of Chemical, Industrial and Phar

maceutical Laboratories (Cl PL A). Joint Committee on the Patents

Bill. 1965: Evidence (New Delhi, Lok Sabha Secretariat, 1966), Vol

1. p 154 and of S G Somani of All India Manufacturers Associa

tion, Joint Committee on the Patents Bill, 1967: Evidence (New

Delhi. Lok Sabha Secretariat. 1969), Vol 1, p 294.

6. HAL. Annual Report, 1961.

7. Evidence of K A Hamied of CIPLA, Joint Committee on the Patents

BUI, 1965: Evidence, Vol 1, pp 149-50.

8 Report of the Committee on Drugs and Pharmaceutical Industry

(Hathi Committee) (New Delhi. GOI, Ministry of Petroleum and

Chemicals. 1975), p 92.

9 For the text of the judgement, which also provides the background

of the case. see. The All India Reporter (Nagpur, AIR Ltd, 1969),

Bombay Section, Vo) 56, pp 258-73.

10 Ibid p 264.

II. Information on this Patent case has been obtained from the judge

ment of the Calcutta High Court (Suit No 1124 of 1962); the plaint;

the written Statement submitted by BCPW (all available at the

Calcutta High Court) and the BCPW Assistant Secretary’s Note

placed at the BCPW Board of Directors meeting held on 27 July,

1970.

12. Hoechst’s patent mentions alkalation with primary amides which

is chemically impossible See Ibid.

13. Minutes of the meeting of the directors of BCPW, Calcutta, 5

December, 1968

14. Report of the Patents Enquiry Committee (1948-50), p 71.

15. Ibid, p 162.

16. Ibid, p 172.

17. Report of the Panel on Fine Chemicals, Drugs and Pharmaceuticals

(New Delhi, GOI, Department of Industries and Supplies, 1947),

P 15.

18. Report of the Patents Enquiry Committee (1948-50), p 168.

19. Ayyangar, Report, p 1.

20.

21.

Patent Office Hand Book, p 32.

Evidence of C V Deliwala of the Haffkine Institute, Joint Com

mittee on the Patents Bill, 1967: Evidence, Vol I, pp 451-52.

22.

Evidence of,N L 1 Mathias and A C Mitra of Neo Pharma Industries,

Joint Committee on the Patents Bill, 1965: Evidence, Vol II, PP

487-88. 493-94.

Information obtained from the Patent Office, Calcutta. Apparent

ly. the application by the Haffkine Institute, referred to earlier in

the text, was made before Section 23 CC was added in 1952.

24. According to Rule 32B (inserted in 1953) of the Indian Patent and

Design Rules, 1933. the Controller shall refuse the application, if

"the Controller is not satisfied that a prima facie case has been made

out for the making of an Order" (Patent Office Hand Book, pp

71-72)

25. For the provisions, see The Patents Act, 1970 (New Delhi, GOI,

Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, 1973).

26. A patent is sealed after it is granted.

27. For a discussion of the important provisions regarding drugs in the

Act of 1970 vis-a-vis the Act of 1911, see S K Borkar, “Patent Act,

1970 and Its Effect on Drug Industry in the Country”, in Annual

Publication (Bombay, Indian Drug Manufacturers Association,

1974).

28. "Applications Filed for Licences of Right under Section 88(2) and

88(4) of the Patents Act, 1970", in Journal of Patent Office Technical

Society. Vol 16. 1982, pp 80-81.

23.

Radical Journal of Health

Responsibility of Industry, Doctors and Government

amitava gnha

The proliferation of irrational and dangerous drugs in India has generated a well-informed and dynamic drug

consumer's movement. Of the several issues that it has taken up the issue of banning high dose oestrogen pro

gesterone drugs illustrates best its capability. On the other hand, the issue has also revealed inefficiency of the

drug control authorities, their inability to implement the rules in the book designed to protect the consumer.

This inefficiency on the part of government institutions is compounded by their close collusion with the drug

industry. The medical profession has also played a crucial role in opposing the ban oj these drugs. The article

highlights the unethical practices and actions of (he different sections who have been involved in pressing for

(he continued marketing of high dose EP drugs.

IN 1982, the Indian Council of Medical Research

recommended:

“Fixed dose combination of oestrogens and progesterone may be

totally banned m the country, even for the treatment of secondary

amenorrhoea as other substitute are available in the market for

management of secondary amenorrhoea”

Based on this recommendation, the ministry of health and

family welfare banned HDEP in June 1982. Today five and

half years after, the drug is freely available in India! The in

dustry, medical profession, courts of law even the govern

ment departments played their role in undoing the govt’s ban

order.

For the first time in India the question of banning of a

drug is being discussed and debated; consequently it has ex

posed the low level of ethics followed by the people involved

in the medico-technical establishment.

It must be pointed out that the issue of harmful effect of

a drug and therefore, its banning had never been raised by

the medical profession. Even the issue of harmful effect of

‘thalidomide’ was taken up by the journalists and the ripple

created in the so-called ‘lay press’ raised a wave which not

only washed away any effort to defend the crime made by

Gruanthal (its manufacturer) but exposed the menace of the

industry in collusion with certain famous opinion maker

medical personnels. In India similarly nothing is being said

or no action had been taken by the famous doctors or opi

nion makers against the horde of drugs banned in developed

countries but freely and legally available in India. It is again

the ‘lay press’ Onlooker which raised the issue through the

write up—“Pregnancy Test Drugs can Detorm Babies—Ban

them’’. The issue, thereafter was widely taken up by the press

and excepting one or two write ups till date none of them

had spoken against the ban of HDPE.

Role of Industry

Harmful effect of the drug on pregnant women was

delected as back as 1967 for. Pioneering task in this area had

been taken by Dr. Isabel Gal. She writes:

“The unfavourable effect of synthetic sex hormones on animal

reproduction was known long before the introduction of HPT pro

ducts in 1958. Despite this the manufacturers recommended HPT pro

ducts as a safe and reliable method of pregnancy diagnosis and gave

assurance that it does not interfere with the physiological course of

pregnancy”

Following the reports of adverse drug reaction with HDEP,

Rousel in 1970, Schering in 1971 and Organon in 1970 did

not refer to use of the drug for pregnancy lest in UK. The

government of India issued order that this drug should not

be used for pregnancy testing and the order be printed on

the labels of the drugs marketed. The drug was established

in India as an abortificient. It was promoted widely for in

ducing abortion. Even after the said order issued by the

December 1987

government, the companies promoted the drug through

marketing staff as an abortificient.

Immediately after the ban order was issed, Organon India

Ltd., (now Infar) placed a writ petition in Calcutta High

Court and was interested to see that the writ was not con

tested by the Drug Controller of India during its hearing.

It happened exactly as desired by the company and the case

was heard and injunction was passed exparte against the ban

order. It is interesting to note that neither M/s. Organon nor

M/s. Unichem and M/s. Nicholas contested the finding of

ICMR on the potential hazard of the drug but simply

challenged that the ban order was not issued in accordance

with the provisions of law. It was submitted that Sec. 18 of

Drugs and Cosmetics Act allows the state govts only to ban

a drug after issuing official Gazette Notification. That too

the Act only provides banning of misbranded, sub-standard

or adulterated drugs. This was an eye opener for the

legislators, who after much shouting from the consumers and

by some Members of the Parliament amended the law later

giving the same power to the Central Govt also. Even now

the question remains that HDPE or any harmful drug, if

banned, should be done according to which law?

The industry did a lot to utilise medical profession in their

favour. In the submission to the Supreme Court and high

courts, the company placed letters written by a number of

general practitioners and gynaeocologists stating that HDEP

should not be banned. In reality this was again done with

the help of the marketing staff who went to the doctors with

the draft of such letters and requested them to write accor

ding to the draft, a letter on their own letterheads. There

fore, it was found that the letters are not only the matically

similar but, so is the language and text of the letters. In some

cases the marketing staff of the companies wrote the letters

on the doctor’s letter pad and asked the doctors to sign them.

The text of these letters more or less read:

“1 support the order of the government in banning the use of high

dose E. P. Drugs in pregnancy' testing.

The drug is highly needed for treating secondary amenorrhoea,

dysfunctional uterine bleeding, endometriosis and dysmenorrhoea.

I have used this drug for a long lime and never seen any adverse effect.

I recommend that this drug should not be banned”.

The industry made another attempt to mislead the courts

on the information regarding the status of the drugs in dif

ferent countries. Organon (I) Ltd stateu that

“It’s not a fact that many countries have banned these preparations.

These preparations are available in countries like UK, West Germany,

France, most of the Western European countries a.id many South West

Asian and African countries” (Infar, 1987).

One can easily find out how far this is a fact. Table 1 will

clarify the position (UN List, 1986).

Infar (I) Ltd had no reply when asked at the public hear

ing why HDEP was not allowed to be marketed in their

55

parent country, Netherlands. Similarly, the company could

not say why the drug was not allowed to be introduced in

many other developed countries. The company’s honesty was

again questioned when Hermann Schulte-Sasse of the In

stitute for Clinical Pharmacology, Hamburg confirmed that.

“l\vo German pharmaceuticals marketed such drugs in

Germany but withdrew them at the end of 1979”.

Was the company confident that Indian consumers did not

have any access to information from 'civilised European

countries’? In fact Dr N N Roy Chowdhury, the president

of Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of

India (FOGSI) wrote to DCI to the same tune of Infar Co

that the drug was available in most of the developed coun

tries. He had also submitted a list although he did not care

to mention any reference. From this list it appears that ‘Shering’ (he does not know that the real name of the company

is Schering Aktiengesellschaft) market HDEP in West

Germany, UK, TUrkey, Japan, Argentina, Mexico, Belgium,

Denmark, Australia. The drug is not enlisted in the ‘Red List’

(Rote Liste) 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, a list of drugs approved

by the government of FRG. Corroborative statement from

Schering issued by Dr H Richter informs that only one brand

of HDEP was marketed by them in third world countries

that two had been withdrawn from October, 1986.

In the absence of any system of dissemination of unbiased

information to the medical profession, the industry takes the

fullest advantage to misinform the profession to mislead

them with the help of their own tailored and distorted facts.

As regards high dose EP drugs, the industry had taken the

fullest advantage of this situation. The Voluntary Code of

Marketing Practices adopted by International Federation of

Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (IFPMA)

suggests that

“Scientific and technical information shall fully disclose the proper

ties of pharmaceutical products as approved in the country in ques

tion based on current scientific information..

“Information on Pharmaceutical Products should be accurate, fair

and objective, and presented in such a way as to confirm not only

to legal requirements but also to ethical standards and standard of

good taste.’’ (IFPMA)

Classical example can be sited from the promotional

literatures of Infar(I) Ltd as to how they have violated all

such codes of ethics. Even the Guidelines of Introduction

of New Drugs by Government of India say that ‘‘the pro

duct monograph should comprise the full prescribing infor

mation necessary to enable a physician to use the drug pro

perly. It should include description, actions, indications,

dosage, precautions, warnings, and adverse reactions.”

A product monograph of Orgalutin, a high dose of EP

Table 1: Status of EP Drugs Worldwide

Countries

1. Norway

2. Sweden

3. Finland

4. Federal Republic of Germany

5. USA

6. UK

7. Australia

8. Austria

9. Belgium

10. Italy

11. Greece

12. New Zealand

13. tfenmark

14. Bangladesh

15. Venezuela

56

Status

Year

Withdrawn

Banned

Banned

Withdrawn

Banned

Withdrawn

Withdrawn

Withdrawn

Withdrawn

Withdrawn

Withdrawn

Withdrawn

Banned

Banned

Banned

1970

1970

1971

1979

1975

1977

1978

1978

1978

1978

1980

1974

1982

1975

used to promote the drug to the doctors is captioned as—A

Woman’s Strength Is a Woman’s Weakness’.

On page three of the monograph to emphasise that the

drug is ‘safe for the patients’ the following lines arc men

tioned quoting a write up of two doctors Dr Choudhury and

Dr Mitra that with the use of the drug there was—

“No alteration in blood pressure.

No alteration in blood-sugar level.

No hepato-toxic effect observed”.

The said monograph had given-indications of composition

and dosage only but nothing was mentioned about precau

tions, warnings and adverse reactions.

If the warnings and precautions circulated by the company

a few years back are consulted, one can find the following

facts in the Therapeutic Index of the company and judge

how safe the product could be,

"Since such preparations may cause an increase in blood pressure in

predisposed women, this should be checked regularly. In case of serious

hypertension the use of the preparation should be stopped immediately!’

“Since the glucose tolerance may diminish during the use of

oestrogen/progestogen preparation, diabetic patients should be kept

under strict control.”

“Hepatic adenomas have been reported in women on oestrogenprogestogen combinations!’

This gives us an opportunity to question the standard of

ethics maintained by the company and of the two doctors

who had shamelessly concealed the facts.

It is also interesting to note that the manufacturers of

HDEP were really’ frightened of the ban order issued by the

governments. In.the Therapeutic Index printed by Infar(I)

Ltd at the time the ban order was issued, the company deleted

all HDEP drugs namely, Menstrogen, Menstrogen Forte and

Orgalutin. But their effort to promote the drug in the market

remained unhindered. The company has never forgotten to

mention these drugs in their price list!

Role of Statutes

Important statute applicable to import, manufacturing,

etc of any drug is the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and

the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945. This is not only an

cient but highly inadequate also. Although it is a central

statute but it has given authority to the State Drug Con

trollers for approval of a drug for registration and sale.

Because of such inadequacy of law, the Central Drug Stan

dard Control Organisation has prepared ‘Guidelines on In

troduction of New Drugs’. We shall see how even the scanty

restrictions under the said Acts and Guidelines have been

violated by the industry.

Organon (India) Ltd, now Infar (India) Ltd had introduced

the HDEP about 20 years before. Earlier, these hormones

had been marketed separately as single ingredients or in com

bination as oral contraceptives. The drug was imported and

the definition of a ‘New Drug’ under Rule 30A of the Drugs

and Cosmetics Rules (DCR) says:

“The importer of a new drug when applying for permission shall pro

duce before the licensiong authority all documentary and other

evidences, relating to its standards of quality, purity and strength and

such other information as may be required by the licensing authority

including the results of therapeutic trials carried out with it!’ (Drugs

and Cosmetics Rules)

At the time of introduction of the drug it could be defined

as a Fixed Dose Combination (FDC) of the third group ac

cording to the Guidelines on Introduction of New Drugs.

This Guideline requires:

“(c) the third group of FDC includes those which arc already marketed,

but in which it is proposed either to change the ratio of active ingre

dients or to make a new therapeutic claim.

For such FDC, the appropriate rationale should be submitted to ob

tain a permission for clinical trials and reports ot trial should be

Radical Journal of Health

from the Country of Origin’. It would be almost impossible

The clinical trials required to be carried out in India before for Infar to submit such a ‘free sale certificate* as it was never

a new FDC is approved for marketing depend on the status allowed to be manufactured and marketed in Netherlands,

of the drug in other countries. If the drug is approved/ their country of origin.

Not only question of ethics but the failure of the regulatory

marketed, phase III trial is usually required to be conducted

in India. If it is not approved/marketed, trials are generally authorities and the lacuna in the laws are exposed when we

allowed to be initiated at one phase earlier to the phase of consider that the manufacturers have not cared to submit

to the minimum requirements of law and the government

trials made in other countries.

On going through the records one can easily find out that guidelines and have developed a large market of Rs 6.18 crore

the company never obtained any permission to initiate clinical yearly.

trials in India as required by Drugs & Cosmetics Rules

(through form 11 and form 12) for a test licence. No pro

Role of Doctors and Professional Bodies

tocols for any trials were ever submitted by the company—

A famous gyaenocologist C S Dawn has written in his

this is required according to the Guidelines for Introduction

of New Drugs. No case report forms were ever submitted. widely used text book.

Secondary amenorrhoea has had spontaneous cure rate in more than

As required in the Appendix III of the said guidelines the

50% cases where any treatment becomes empirical. New therapies

following reports on the studies are to be submitted by the

of pituitary gonadotropin, clomiphene and bromocryptine showed

company. (1) Human/clinical pharmacology (2) Exploratory

promising results in the treatment of selected cases where these are

Trials. (3) Confirmatory Trials. This was never done. Neither

indicated. Longer the secondary amaneorrhoea persists poorer

the company nor the Director of Drugs Control, Government

becomes the prognosis.

of West Bengal, who allowed the company to sell the drugs

He, as a professor, never vouched for the use of HDEP

in India can produce the following records relating to trials in secondary amenorrhoea in the classrooms and thus hid

supposed to have been conducted by the company ajid ap his other face. For, as a member of the Federation of

proved by the government authority.

Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of India (FOGSI)

Title of the Trial

he says exactly the opposite. He attended the public hear

Name of investigator and Institution

ings held at Madras, Delhi and Calcutta just to say that as

Objective of Tribals

Design of Study: open, single-blind, or double blind, non an eminent teacher and famous gynaecologist he had never

seen any adverse reaction with HDEP, and the drug was very

comparative or comparative, parallel group or cross over.

much needed for treating secondary ameneorrhoea.

Number of patients, with criteria for selection and exclusion,

whether written informed consent was taken.

His notoriety had not stopped here. After the Delhi public

Treatments given, drugs and dosage forms, dosage regiments method

hearing, he had submitted a study report on May 10, 1987

of allocation of patients to the treatment;

of a purported trial as a chairman of the family welfare com

Observations made before, during, and at the end of treatment,

mittee of FOGSI. The report was titled as ‘Use of Common

for efficacy and safety, with methods used.

Drugs in Pregnancy—Indian Experience’. It is only two-page

Results; exclusions and dropouts, if any, with reasons, description

monograph

but the dimension of the study is enormous as

of patients, with initial comparability of groups where appropriate,

clinical and laboratory observations on efficacy and safety, adverse the first paragraph of this report says:

submitted to obtain marketing permission.”

drug reactions.

Discussion of results: relevance to objectives, correlation with other

report/data, if any guideance for further study if necessary.

Summary and conclusions.

In order to maintain a minimum standard of ethics, trials

should be conducted with any drugs prior to their introduc

tion in the country. For the purpos. ‘licence for examination,

test or analysis’ has to be procured under Rule 21(c) which

was never done by Infar in this case. While applying for

manufacture of ‘New Drugs’ as per Rule 75-B of the DCR

one needs to supply “informations as may be required in

cluding the results of therapeutic trials carried out with it’’

(sub sec ii). This was never done cither bv the manufacturers

of HDEP.

// is strikim* to note that a controversial drug iv</y in

troduced in our country at the time when enough controver

sy was raised elsewhere. The manufacturers never cared to

conduct any trials in India. They were not only given licence

to manufacture such a drug but it was periodically renewed

by the drug control authority.

The guidelines for the introduction of new drugs per sec

9.2 under the title ‘Regulatory status in other countries’ state.

“It is important to state if any restriction have been placed

on the use of the drug in any other country, e g, dosage

limits, exclusion of certain age groups, warning about adverse

drug reaction”.

This was not done at any time—either at the time of in

troduction of the drug nor any time thereafter by Infar. On

the contrary, as discussed before, the manufacturers have at

tempted to misguide authorities with false information that

the drug is in use in many developed countries.

The guidelines also require (sec 9.3) a ‘Free sale Certificate

December 1987

“An all-India multicentric study was conducted during 1982 and

1983 by the Food, Drugs and Medicosurgical Committee of FOGSI

by the author as the chairman of the committee. Fourteen teaching

and rural centres participated in this study. Statistically controlled

protocol was prepared in consultations with Department of Hygiene

and Public Health, Calcutta. The protocol covers 78 factors”.

No further methodology and materials used in the study

was mentioned. The result was:

“There were 245 congenitally malformed newborns in this study.

The incidence of congenitally malformed newborns at various cen

tres varied from 2 to 10 per 1000 births”.

The report never mentioned directly as to how many preg

nant women were covered in the study. If the average in

cidence of malformation of newborn babies are considered,

according to the study, say five per 1000 and a total number

of malformed newborn babies reportedly were 245 then we

arrive at the fact that’in order to get such result, the trial

covered 49,000 pregnant women. That such a phenomenally

high number of patients were covered in only one year from

“14 teaching and rural centres” is noteworthy as this type

of trial is impossible even in developed countries.

In the Calcutta public hearing Dr. Dawn was asked that

in order to prove that his trial was not fake, he should sub

mit papers relating to the ten protocols as required by the

government. Dawn is yet to prove that it is not fake Obvious

ly the sole objective of producing such a report, which has

never been published in any professional journal was to prove

that no congenital malformation could be found with the

use of hormonal drugs during pregnancy'. When the govern

ment had banned the use of HDEP during pregnancy' and

the manufacturers have accepted it, the eminent doctors like

Dawn, C L Jhaveri, P K Khan, Sharma are all rejecting it.

57

Dr. Sharma of Delhi and Khan of Calcutta had without any

hesitation said at the public hearings that they would con

tinue to use HDEP for pregnancy testing. We are yet to see

the Medical Council of India react to such violations by

cancelling the registration of these doctors.

Dr. Jhaveri of Bombay, seniormost and famous gyaenocologist and many times president of FOGSI went even further

that estoprogin (HDEP) drug came as a blessing. It had

helped—in the second world war women who had been

assaulted by the soldiers had used HDEP drugs to abort

unwanted feluses! He stated in the Delhi and Bombay hear

ings that in his 40 years’ of gynaecological practice he had

used the drugs for inducing abortion and had not found a

single case of malformation of babies. His statements were

recorded by the Drug Controller of India during the public

hearings.

One may conclude that Jhaveri had committed punishable

offences in two cases. First, he had practiced MTP when it

was not legalised. Second, that he had violated the govern

ment order in using the drug on pregnant women. We are

yet to see that DCI take any action against Jhaveri. This sertugenarian doctor was so loyal to the arguments put by the

industry that he rushed to the dias at the Bombay hearing

to assault one speaker who was dissecting a point of law

placed by the industry.

A good number of famous gynaecologists have attend

almost all the public hearings leaving their generally over

crowded chambers and have said the same things repeatedly.

They had not cared to place any pharmacological and clinical

evidence in support of their statement that the drug is safe

and necessary.

In the Delhi and Calcutta hearing N N Roy Chowdhury,

president of FOGSI stated that the Federation had

unanimously adopted a resolution that the government

should not ban HDEP as they were safe and needed to treat

secondary amenorrhoea, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, en

dometriosis, menopausal symptoms, etc. and there was no

substitute for this drug. This statement was challenged by

a professor of gynaecology at Calcutta who as a member

of FOGSI wanted to know where and when such

‘unanimous’ resolution was taken. He also produced a state

ment by Dr J Mitra, Honorary Joint Secretary of FOGSI

which stales

“I am of opinion that high dose combination of oestrogen

progesterone should not be used during pregnancy.

I also feel that it is not essential to use this high dose combination

for treating gynaecological condition like dysfunctional uterine

bleeding, menopausal syndrome, etc. These combinations should not

be used indiscriminately as there are potential hazards”

Roy Chowdhury could not provide any proof to substantiate

his statement which was openly challenged.

Another instance of violation of minimum standards of

ethics can be cited with reference to the activities of P K

Banerjee, Honorary Treasurer of the Indian Medical Associa

tion. There are complaints by his professional colleagues that

he is an obedient supporter of Infar (India) and defended

the company’s interest in using anabolic sterioid for pro

moting growth in children. Banerjee wrote a letter to DCI

dated April 6, 1987 in the capacity of honorary treasurer,

IMA stating that the drug is much needed and harmless. On

inquiry, it was found that he had misused the good name

of the IMA. As the President of IMA stated that

I would like to mention that the letter issued by Dr Banerjee is his

own view and he is not authorised to communicate the views of IMA.

It is unfortunate that he has used IMA stationary for expressing his

personal views”.

It is necessary to mention here the role of the two doctors

who were involved with banning the drug—P Das Gupta,

Deputy Drug Controller and P K Dutta of World Health

58

Organisation. The Deputy DCI had no scruples about

favouring the industry openly. He tried to dilute the issue.

The Supreme Court had clearly asked the DCI to conduct

public hearings on banning of high dose combinations of

E P drugs. The Deputy DCI. at the Calcutta hearing, attemp

ted quite something else. He stated that the question of ban

ning HDEP should not be taken as an ego fight. Although

the Drugs Controller’s office had once banned it, it did not

mean that they should stick to such decision for- ever. He

also appealed to the gynaecologists that they should come

forward and suggest a ‘cut off1 dose for estrogen-progestogen

combinations. He wanted to confuse the issue on the ques

tion of high dose and low dose EP. He wrote letters without

the knowledge of DCI to FOGSI and Indian Associations

of Fertility and Sterility asking them to give their views on

a questionnaire on estrogen progestogen combinations, dated

March 23, 1987. He carefully dropped words ‘high dose’ in

the questionnaire. The questions are tailored in the follow

ing way which is suggestive of the desired answers.

I W hether fixed dose oestrogen and progestogen is necessary i

the management of secondary amenorrhoea?

2. What are the possible side effects of fixed dose oestrogen and

progestogen combination?

3 Do you feel that with a suitable cautionary label the use of fixed

dose of oestrogen and progestogen combination in pregnancy be

prevented?

4. Whether fixed dose oestrogen and progestogen combinations are

marketed in other countries?

5. Whether fixed dose oestrogen and progestogen drugs should be

banned9

6. Do you have any other suggestions on this issue?”

Nowhere in the above questionnaire had Das Gupta men

tioned 'high dose estrogen and progestogen’. It can be noted

that oral contraceptives are also fixed dose oestrogen and

progestogen combination. The president of these two

organisations C L Jhaveri and N N Roy Chowdhury made

full use of such questionnaires and pumped the arguments

of the industry in their reply which was considered by Das

Gupta as an important document at the public hearing held

at Bombay where Prem K Gupta, DCI who was absent at

the Calcutta public hearing said that this was done without

his knowledge and offered an apology for the action of the

Deputy DCI.

At the Calcutta hearing Das Gupta was openly suppor

ting the manufacturers of HDEP. He, along with Dr P K

Dutta helped the management of Infar to create a stir at the

public hearing and cancelled the hearing with a plea that they

may be physically assaulted when there was no valid reasons

to do so.

It is necessary to mention the role of other doctors and

professional organisations. The reactions of famous

gynaecologists and pharmacologists of UK on the need of

HDEP were different. Some of these doctors are members

of the Committee on Safety of Medicines. Some of the

responses are as follows;

I “I feel strongly that there is no justification for (he use of these

drugs, in amenorrhoea, menstrual irregularities and other

"gynaecological disorders”. Amenorrhoea and menstrual irregularities

require investigation and specific causes identified and, if necessary,

treated. If menstrual regulation is required in patients who have no

periods and who have irregular (and perhaps heavy and painful) period

then the treatment of choice is either the conventional low dose

estrogen-progesterone oral contraceptive pill, or progestogen alone.

1 think it would be irresponsible and dangerous to encourage the

use of high dose estrogen-progestogen combinations in management

of these gynaecological symptoms”. (Dr. Stephen Franks, Reproduc

tive Endocrinology; St Mary's Medical School, London).

2 ”1 was alarmed and disturbed to learn that high dose combina

tions of oestrogen and progestogens are still marketed, and used in

the Indian sub-continent. I understood that steps had been taken in

1983, to withdraw- these productsand 1 find it extraordinary that four

Radical Journal of Health

years later it is still possible to promote, prescribe and purchase such industry than on the harm to consumers. They forgot that

medicines.

(his hearing was most important because for the first time

They arc associated with significant risks to the factus, if ad merits and demerits of a drug were being publicly heard.

ministered during pregnancy. The Committee on Safety of Medicines They also forgot that their counterparts in developed coun

(of which I am a member) issued warnings to all doctors about these

tries have forced the companies to obey a minimum code

hazards in 1975 and 1977. The British Medical Journal drew atten

of

conduct and Infar was admonished by the International

tion to the problem in an editorial in 1974. As a result of these publica

tions, and of professional opinion, pharmaceutical companies in the Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association for

UK voluntarily withdrew their products containing high dose oestrogen violation of its voluntary code however biased, weak and in