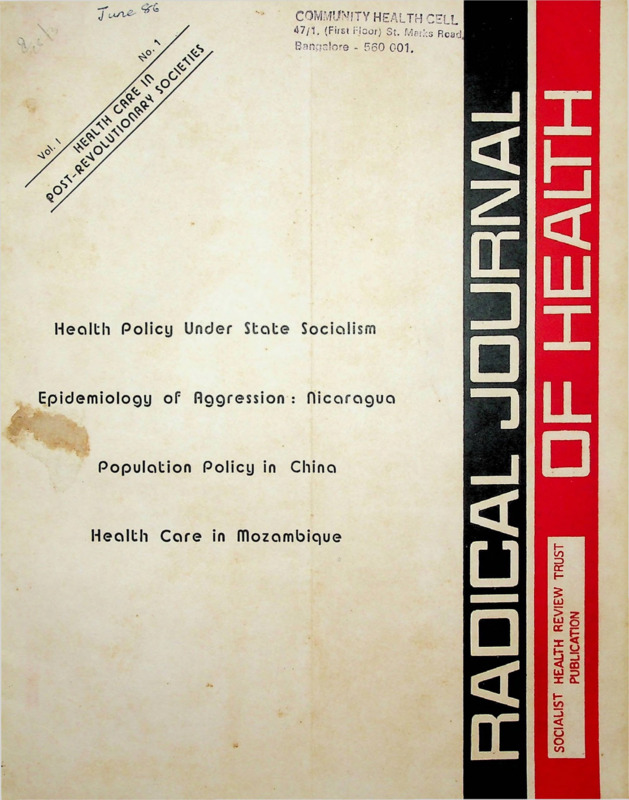

Radical Journal of Health 1986 Vol. 1, No. 1, June Health care in Post-Revolutionary Societies.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

COMiW-'ITY HEALTH C ELL

47/1, (First Hear) St. Marks Read.

Bandore - 560 001,

Health Policy Under State Socialism

Epidemiology of Aggression : Hicaragua

Population Policy in China

Health Care in Mozambique

uj

>

UJ

CD

tn

ra

o

o

cS

Yol I

2—

HEALTH CARE IN

POST-REVOLUTIONARY SOCIETIES

3

O

cu

"5

CQ

Number 1

1

Editorial Perspective

ISSUES IN 'POST REVOLUTIONARY’ HEALTH

CARE

Dhruv Mankad

Working Editors :

Amar Jesani, Manisha Gupte,

Padma Prakash, Ravi Duggal

Editorial Collective :

Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (A P),

Imrana

Quadeer, Sathyamala C (Delhi),

Dhruv Mankad (Karnataka), Binayak Sen,

Mira Sadgopal

(M P), Anant Phadke,

Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar, Jean D'Cunha,

Srilatha Batliwala (Maharashtra) Amar Singh

Azad (Punjab), Smarajit Jana and Sujit Das

(West Bengal)

3

HEALTH IN NICARAGUA

Amar Jesani

11

MEDICAL CARE AND HEALTH POLICY UNDER

STATE SOCIALISM

Bob Deacon

22

POPULATION POLICY AND SITUATION IN CHINA

Malini Karkal

Editorial Correspondence :

25

Radical Journal of Health

C/o 19 June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay - 400 050 India

HEALTH CARE IN MOZAMBIQUE

Padma Prakash

Printed and Published by

Dr. Amar Jesani from C-6 Balaka

Swastik Park, Chembur Bombay 400 0?1

32

HOMOEOPATHY

B. K. Sinha

Book Reviews

Printed at :

37

Omega Printers. 316, Dr. S.P. Mukherjee Road,

Belgaum 590001 Karnataka

EXPLODING MYTHS

Anant Phadke

Annual Subscription Rates :

Rs. 30/- for individuals

Rs. 45/- for institutions

Rs. 500/- life subscription individual

US dollars 20 for the US, Europe and Japan

US dollars 15 for other countries

We have special rates for developing

countries.

SINGLE COPY : Rs. 8/-

f All remittances to be made out in favour of

Radical Journal of Health. Add Rs. 5/- on

outstation cheques.)

39

A BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF PSYCHOLOGY

Pornima Rao

Discussion

CONTRADICTIONS WHERE THERE ARE NONE

Thomas George

Up date - News & Notes : 29

The views expressed in the signed articles do

not necessarily reflect the views of the editors.

Edito rial Perspecti ve

Issues in ‘Post-Revolutionary’ Health Care

HEALTH care system and the health status of the people, of modernisation in PR societies. Still, in the process, these

like all the other aspects of social life, have undergone societies were indeed able to meet the basic requirements of

tremendous changes in those societies where the rule of food, clothing, shelter and medical care of all the people,

capital has been challenged in a revolutionary fashion by the irrespective of their incomes and thus therefore, resulted in

toiling masses. The class nature of the forces that led the a healthier population.

revolution or of those which rule these societies at present, Better Access to Medical Services: Medical services being by

may be controversial, the direction taken by these societies and large free and extensive, are easily accessible to most

after the revolution may be criticised, but the fact that there people. One’s economic position does not prevent one from

have been dramatic improvements in the health status of the availing oneself of the best medical care available. This has

people of these societies following the revolution canot be indeed affected morbidity and mortality patterns in the PR

denied. Conventional health indicators have shown amaz societies.

ingly rapid improvement (as compared to capitalist societies

But whether the health care structure that has emerged

of comparable size, population and levels of development) is really democratic and ‘socialistic’, operated by the working

in the USSR, China, Vietnam, Nicaragua, Mozambique and class possessing the necessary skills and knowledge is a

the East European countries. These societies arc being debatable issue. There are indications to show that it is not.

categorised here as post-revolutionary (PR) societies. (We use There are strong tendencies towards professionalism and

the term ‘Post-revolutionary’ rather simplistically in place technocratic control. One also needs to assess whether or not

of the more controversial ‘socialist’, though we arc aware that a sexist bias against women exists in the field of health care

the use of this term too, is not free of problems.)

and medicine. Therefore, it is not adequate to apply only the

Several features distinguish the health care systems of the conventional health criteria to assess the nature of the health

PR societies from those of the capitalist societies. They care system and the health status in societies generally K

include, public ownership of health care institutions and recognised to be different from capitalist societies. More

allied industries like the pharmaceutical industry, (he near sensitive indicators like comparisons of differences brought

absence of privatised medical care, free or heavily subsidised about in health and disease patterns in USA and USSR (dr

health care, rationalisation of health care delivery, strong India and China), wage differentials among medical and

emphasis on the promotivc and preventive aspects, disease health personnel, the proportion of women occupying high

control by mass action rather than by biomedical interven positions, the extent of homogenisation (narrowing down of

tions alone, decentralised control, integration of traditional sex, race, class, occupational and regional differences of

systems and their practitioners into the existing delivery health and disease indices) and so on need to be applied.

system and so on. Not that all of these could be found in Only such characteristics can differentiate a developed

any one or all of these societies. For instance, emphasis on ‘socialist’ pattern of health care from that of a developed

decentralised control and self-reliance at the local level capitalist society. Whether the health care systems in PR

prevailing in China may not be found elsewhere (Sidel and societies has indeed reached such a stage is an issue requiring

Sidcl, 1982). But one or more of these are generally to be much analysis and discussion.

found in the health care systems in all the PR societies.

While noting the positive aspects of health and health care

Rapid changes in conventional health indicators in the PR societies, one cannot fail to take note'of several

characterised by steep falls in infant mortality rates; reduc features which raise vital issues regarding the nature of health

tion in morbidity due to infections like tuberculosis, malaria, care in these societies, having wider implications outside the

schistosomiasis and Sexually Transmitted Diseases (Sigerist, field of health and medicine.

J947; Alderguia and Alderguia, 1983; Quinn, F973) and

It is noticed that indicators like life expectancy at birth,

reduction in population growth rates cummulatively point IMR and others have reached a plateau and are even.

to the improvements in the health status of the people. They regressing.

have been brought about no doubt, as a result of better nutri

Also, a tendency towards overmortality of males over

tion, sanitation and hygiene, easy availability of sale drink females is noticed {International Journal of Health Services,

ing water, improvements in housing, improved facilities for 1983; Gidadhubli, 1983) due to steep increase in cardiovascular

women (as compared to those in the capitalist countries), diseases, cancer and accidental deaths. A similar

better medical care as well as better work environment phenomenon is noticed in the advanced capitalist societies

indicated by more stringent environmental and industrial also (see Doyal with Pennel, 1983). These diseases have been

safety standards (Derr et al, 1982). The two most important associated with over consumption, stress and other en

factors responsible for these improvements, can be identified. vironmental factors. Whether high incidences of such

Rapid Modernisation and Abolition of Absolute Poverty: diseases signify a life-style and an environment resembling’

Though not a uniform phenomenon in all the PR societies, those in the advanced capitalist societies or not is a ques

this has been the most important factor in improving the tion that needs to be resolved.

health of the people. This was made possible as a result of

In the USSR, an increasing concern is being felt about the

the defeat of the old bougeoisie and their allies in these rise in alcoholism. Various legal and administrative measures

societies. Now, whether the ensuing nfode/’o^tion was have been initiated to curb this problem (Lindgren, 1985)

‘socialist modernisation’ as envisaed by Marx or not is a Alcoholism is associated with psychosocial stresses. Under

moot point. Similar quantitative improvements have also capitalism, besides other factors, a lack of creative pleasure <

been seen in the advanced capitalist societies dilrihg the 19th in work, leads an individual to avenues of superficial

and early 20th centuries and therefore, they by themselves pleasures. Alcohol is one of (hem. Is a similar process still

cannot be said to be the characteristics of ‘socialist’ nature at work on an increasing scale in PR society like USSR? This

June 1986

A

rather uncomfortable question needs id be faced squarely crucial question of the relationship of a social formation and

in order to comprehend the real nature of the processes substructures thereof. Though developments in health and

affecting the psychosocial health of the people in these health care systems come under the influence of socio

societies. Another related indicator reflecting the sociop- economic factors in movement—that is of history—this rela

sychological disharmony is the incidence of mental disorders tionship is not one -to-one and deterministic. It is a highly

complex relationship of mutually dependant dialectical

and suicides.

Though quantitative indicators of health do give an idea interactions. And therefore, each problem has to be

about the health status of a society, but it does not give the understood within its specific historical and social context.

Thus, while studying health and health care in any social

total picture. It can be shown that'early development of

capitalism also produced improvements in the quantitative formation, one important point needs to be kept in mind.

indicators of health care. What it did not improve was the A ‘socialist’ health care system develops in the historical con

quality of health care: doctor-patient-relationship has become text of the process of ‘revolution’ and thus carries with it

depersonalised, the aged are marginalised; the mentally sick the stam^ of the specific processes of the society with all

are heavily drugged and dehumanised. What is the situation their contradictions. Neglecting this aspect may lead one to

in the PR societies? How and how much different is the an incorrect understanding of these societies as well as their

quality of care to the sick, the aged, the minorities, the health situations (Segall, 1983). One may be led to a narrow

women and the mentally sick from those in the capitalist empiricist position; a position which adopts a static view of

societies? What one finds would point to what could well social structures and considers the health care system existing

be an important differentiating feature of a ‘socialist’ health in a society as directly reflecting its socio-economic processes.

Taking an isolated view of the events that went into making

care system.

In a capitalist society, medicine reflects and reinforces the up the health care system in a PR ‘Socialist’ country, this

bourgeois ideology. Thus, a disease is reduced to a biological position labels whatever exists there as being ‘Socialistic’ in

phenomenon, ignoring the rolc-often a determining one-of nature. On the other hand, it may also lead one to take an

social, economic and cultural factors in its causation. Such idealist view constructing an abstract ‘Socialist’ model of

a view justifies the use of biomedical interventions causing health care devoid of any socio-historial context. Various

a growth in the demand for industries producing the required characteristics are ascribed to such a model. Out of these,

technological inputs. On the other hand, the hierarchical rela which constitute the necessary and the sufficient conditions

tionships in the medical field amongst the medical personnel, for a ‘Socialist’ health care system are unspecified. Therefore,

between doctors and patients-reflects the bourgeois ideology mere absence of a few characteristics of this idealised model,

of class, race and sex dominance. Now in the PR societies, in an imperfect concrete health care system, full of contradic

how do health planners, doctors as well as people view health tory tendencies of a PR society, leads one to label it ‘nonand disease. How are the relationships amongst various socialistic’. Worse still, it denies the possibility of waging

health personnel? These are questions of vital iriiportance struggles to incorporate some of these feature into the health

that should be resolved while assessing the health care care systems of capitalist societies.

It would not be entirely out of place here to mention a

systems of PR societies.

There have been disturbing reports of dissidents in PR related problematic of the role of struggles in a capitalist

societies being labelled as ‘behavioural deviants’ and of use* society to imparting to. the health care system, some of the

of psychotropic drugs to bring about behavioural conformity. ‘Socialist’ characters. Whether a movement for greater social

This is a blatant example of the use of ideology in medicine control over health care services and allied industries is a

to serve the political needs of a.class or a group by converting movement towadrs a ‘revolutionary’ health care system or

an essentially political issue into a medical problem. What not is a crucial question for those fighting for fundmenial

are the compulsions that such practices persist in PR societies social changes. One exteme view, might see such a struggle

is also an issue related to the question of ideology in medicine itself as a revolutionary movement thereby overlooking the

in PR societies.

overall persepctive of such a system. On the other hand, an

In some countries like Poland for instance, chronic shor equally extreme view may call such a movement as ‘refortages of drugs, equipments and staff are reported. {Interna 3mist’ as it does not touch the root-cause, thereby overlooking

tional Joyrnal of Health Services, 1983) Now whether this the vital importance of stages in the movement for ‘revolu

shortage is real, that is as related to the needs of the people tionary’ health care. Several other factors like the leadership.

or false that is as related to the needs of the socially more mass mobilisation, methods used for raising people’s ’

powerful medical profession remains to be seen. A false shor awareness, modes of organisation and struggles also need

tage could be felt if there is a tendency towards to be assessed before making any judgment. A thorough

overmedicalisation of life; by replacing community level analysis of the inter relationship of a health care system and

health care personnels and paramedics by doctors; by the a social formation would go a long way to resolve a cons

demands of doctors for more technological inputs of tant dilemma faced by those involved in such struggles.

doubtful value and so op. If the shortages are indeed real,/

a study of the underlying socio-economic processes could

reveal much about not only the. health care scene of the In this issue: Amar Jesani writes about the problems and process affec

health in Nicaragua; Malini Karkal discusses the population policy

society but also about the problems of ‘socialist’ reconstruc ting

in China and Padma Prakash draws attention to the changes brought

tion during the PR period.

about in the health care system in Mozambique after 1975. Bob Deacon’s

reprinted article raises relevant issues regarding health and health care

• in the three post-revolutionary societies. Soviet Union, Hungary and

oland. And we introduce ‘Update’ a section for reports, notes and

Now, the causes of these problems and the underlying pro comments.

Towards a Dialectical Understanding

cesses can only be understood in the context of the prevail

ing social and economic conditions of the existing social for

mation. An analysis of these problems bjings us to the very

2- •

-

—dhruv niankad

(References: see p 39)

Radical Journal of Health

Health in Nicaragua

Epidemiology of Aggression

amar jesani

Though the Nicaraguan revolution is still fighting for survival against escalating US aggression, it. has ushered

in far-reaching changes in the field of health and health care. These changes are examined in this paper. The

author refers to the role health workers played in the Nicaraguan revolution and discusses the post-revolutionary

reforms introduced in the health care system and the consequences of US imperialism's continuing war against

Nicaragua for the people's health. Health professionals, the author argues, will have to understand (he epidemiology

of war better since the world is likely to witness more revolutionary upheavals and crises as well as imperialist

aggressions.

A QUARTER of a century ago, the victory of the.'socialist

revolution in Cuba, till then the so-called backyard of the

US imperialism, generated a new wave of revolutionary

movements, not only in the Carribcan basin, Central

America and Latin America, but all over the world. The

revolutions in Grenada (March 1979) and Nicaragua (July

1979) widened the breach opened in the imperialist empire

by the Cuban and Indochinese revolutions. The revolution

in Grenada was, however, crushed by US imperialism before

the whole process could completely unfold and get fully con

solidated. The revolution in Grenada nevertheless in

augurated changes in the health and health care system of

that country, though it is beyond the scope of this article

to deal with them. Also, the information available to us is

very fragmentary to allow us to discuss the changes in detail.

On the other hand, although the Nicaraguan revolution is

still fighting for its survival against escalating US aggres

sion, it has unleashed far more profound changes in all

aspects of people’s social life, including in the field of health

and health care, enabling us to examine them in considerable

detail

There are few regions which have been so much the ob

ject of the foreign policy of an imperialist,power as Central

America.and the Carribean. It has been the theatre for per

manent US intervention for 85 years. The US has always

claimed the right tQ lay down the law there. It considers this

whole region to be an integral part of its ‘defence system’

and has 40 to 50 military bases there and is building many

new ones. In 1982-83, 20 per cent of entire US military budget

was earmarked for this region. Behind this military involve

ment is the US economic interest in the area which is a ma

jor communications and trade route as well as a great,raw

material reserve and source of cheap labour power in the in

ternational division of labour (Fourth International, 1985,

p 89). This is the reason why the countries in this region are

kept strictly subordinated to imperialism to such an extent

that the political regimes there are ‘created’ by the US.

The super-exploitation of people there by imperialism

has led to deterioration of living standards to abysmal levels,

extreme poverty, unemployment, and so on. The resistance

to this exploitation has also grown so much so that people

are in a state of permanent war with the military state

machines. The health consequences of this continuous war

are far-reaching, to the extent that the health professionals

are suddenly required to scientifically understand the health

June 1986

consequences of war or the epidemiology of war and

agression.

Nicaraguan Revolution: Historical Background

The Subjugation'. Nicaragua, like other parts of Cen

tral America, was conquered in 1523 by the Spaniards and

they subjugated the Ghorotec Indians of t-he Aztec family.

It become a centre for slave trade for more then three cen

turies under Spanish rule. It attained “independence” in 1821

and slavery was abolished in 1824 (Weber, 1981, pp 1-5). Ever

since its “discovery” Nicaragua has always been of interest

to the great powers. The US has militarily intervened in

Nicaragua at least three times.

The first US armed intervention took place in the mid

nineteenth century at the time of California gold rush. This

intervention, though short-lived, opened a way for US finan

cial and political interests which, in the course of half a cen

tury, converted Nicragua into a coffee exporting country with

a plantation economy. Coffee constituted 50 per cent of the'

value of Nicaraguan exports till the cotton boom of the

1950s. All, exports were chiefly to the US. The second US

intervention took place in 1909 and US forces continued to

occupy the country from 1909 to 1925. When the' US

withdrew its forces in 1925 it thought that the regime backed

by it would survive,'but the rebellion against the puppet

regime led to the third US intervention within months after

the withdrawal. This, time the US continued lb occupy

Nicaragua till 1933.

During this third intervention, the US helped create a

military force, called the National Guard, inJ927. The

National Guard was.at the beginning commanded, equip

ped, trained and financed by the US. The chief of the Na

tional Guard, Anastaslo Somoza Gracia, seized power in

1936 and established a US backed family dictatorship lasting

for almost fifty years (Weissberg, 1981). Under Somoza,

Nicaragua acted like a true puppet of the US and, through

the National Guard, provided counter-revolutionary military

forces during the 1954 attack on the progressive Arbenz

regime in Guatemala (which incidentally, profoundly

politicised a doctor, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, who sub

sequently led the Cuban revolution with Fidel Castro) and

during the 1965 offensive in the Dominican Repubic. It was

from Nicaragua, moreover, that the CIA mercenaries left for

the. 1961 Bay of Pigs landing in Cuba, the most concerted

(albeit unsuccessful) US attempt to destory the Cuban revolu

tion (Weber, 1981, p 30).

3

The Revolution: The third US intervention in 1925-26

inspired a nationalist uprising led by general Augusto Cesar

Sandino.'The war of resistance, fought on the lines of guerilla

warfare, lasted till the murder of Sandino on 21st February,

1934. But it helped in radicalising many individuals who had

been also influenced by the October Revolution. The 1959

Cuban revolution gave the struggle in Nicaragua further

impetus and in 1962 the Frente Sandinista de Liberation Na

tional (Sandinista National Liberation Front, FSLN) was

formed. The FSLN combined guerilla military warfare and

rural and urban mass organisation and mobilisation for 18

years to lead the revolutionary insurrection on 19th July, 1979

that overthrew the Somoza regime, destroyed the erstwhile

state power and created a completely new statue apparatus

under the leaderhip of the FSLN. It is under the leadership

of the FSLN that the reconstruction’of the Nicaraguan

society is under way.

Before we take up discussion of the changes in the

Nicaraguan health services after the revolution, it would be

useful to know what role the health functionaries played in

the revolution, although this aspect of the revolutionary

movement is not very well documented. While the health care

services have long been deficient in the Central American

region, doctors, medical students and other health func

tionaries have participated in and even led struggles for social

reform. Some examples can be given easily. Che Guevara in

Guatemala, Calderon in Costa Rica, Romero and Castillo

in El-Salvador, Bolanos and Rosales in Nicaragua and

Morales and Alvarado in Honduras led political movements

and governmental efforts toward the establishment of social

security systems, workmen’s compensation, the legalisation

of unions, and agricultural reform (Garfield and Rodrigues,

1985). In Nicaragua, besides the above-mentioned doctors,

reference can be made to a hunger strike by the health

workers in the capital, Managua, in January 1979, in pro

test against the killing of dozens of people participating in

a gigantic demonstration to mark the first anniversary of

the assassination of Pedro Joaquin Chamarro, an antiSomoza editor of the bourgeois paper La Prensa (Weber, 1981

P 4).

Post Revolutionary Health Services Reforms

'Further, it should be kept in mind that these principles

and new health care planning were inaugurated in the con

text of the thorough-going revolutionary reforms started in

the entire social structure. The way the FSLN has introduced

agrarian reforms, which undoubtedly have helped in improv

ing the health status of the people will illustrate this point.

In July 1981, the first agrarian law was enacted which

made it possible to confiscate land left lying fallow by owners

holding 350 hectares or more of land on the Pacific Coast

and 750 hectares or more on the Atlantic Coast. Another

law enacted in early 1986 removed these limits of 350 and

750 hectares and has made it possible to confiscate land of

all big landowners who do not plan for efficient production

(Udry, 1986). The cffects.of these reforms can be seen in the

fact that in 1978. 36.1 per cent of land was owned by those

with more than 350 hectares, whereas they now (in 1984) own

less than 11.3 per cent. The owners of more than 150 hectares

of worked land, who possessed more than 50 per cent of the

land in 1978, now have no more than 23.8 per cent. The land

distribution has been carried through briskly. In the first

fourteen months of the agrarian reform, the average rate of

granting property titles was 647 per month, and the area of

land involved was on average 15 hectares per family. In

addition to the distribution of land for private cultivation,

38 per cent of land is under state ownership (APP 19.3 per

cent) and co-operatives (10 per cent in Service Co-operatives.

CCS and 8.7 per cent in Sandinista Agricultural Co

operatives. CAS) (Devillicrs, 1984).

The contribution of these reforms to the improvement

of the health status of the people cannot be underestimated,

especially in a country which has a predominantly agri

cultural economy. Otherwise mere changes and improve

ments in health care delivery cannot achieve in seven years

only, the tremendous improvement in the health status of

the people. In short, what we are arguing for is not only that

a revolutionary regime should seriously undertake thorough- •

going redistribution of wealth, but also that in order to make

health a fundamental right of the people, people must be

given the basic right over the means of production and the

result of their productive labor power.

People’s Participation

Another basic principle of the health services in

Nicaragua is people’s participation “in health policy deter

Nineteen days after the victory of the Nicaraguan revolu mination at all levels”. This term, ‘Peoples Participation’ is

tion the new government issued a declaration outlining the so much abused, particularly in the field of community

basic principles of the new health care system. These prin health, that it must be put in a proper perspective in the con

ciples are:

text of Nicaragua. Fundamental to our understanding of peo

1 Health shall be a right of everyone;

ple’s participation is people’s power—political and economic

2 Health services will be a responsibility of government; power in the hands of the working people, mediated through

3 The public will participate in health policy determination their own mass organisation and having decisive say in

at all levels and

decision-making. Only if such people’s power is existing can

4 All health services will be planned on a regionalised, it get permeated in genuine participation of people in health

systematic basis, (Braveman and Roemer, 1985).

care. Therefore, wc must examine in brief whether these

Special emphasis within the new system was put on necessary pre-conditions for the genuine participation of the

maternal and child health, occupational health, and primary people, as envisaged in the basic principles, exist in

health care for everyone. 1/5 overcome the deficiency in the Nicaragua.

availability of health personnel, high priority was also given

The revolution in one stroke destroyed the essential part

to educing them in njiich greater number and in a new of the bourgeois state apparatus—its repressive forces—and

mould.

created a new revolutionary army, called the Sandinista

Basic Principles

4

Radical Journal of Health

People’s Army (EPS), whose origin, composition, leadership

structure and training was.a direct result of the revolutionary

struggle. The original police force was smashed and the

Sandinista police was set up from working class fighters,

thrown into unemployment because of war damage to the

economy. In February 1980, the Sandinista People’s Militia

(MPS) was formed by arming tens of thousands of workers

and poor peasants. The Sandinista Defence Committees

(CDS) are another organised structure of the armed work

ing people for their self-defence. While the EPS and the San

dinista police are part of the organised state structure, the

MPS and the CDS are made of working people. The point

to be noted is that the defence of the nation and exercise of

power are not the functions of the state apparatus alone, but

also of the armed volunteers from the urban and rural pro

letariat and the peasants. While discharging their duty as

workers and peasants, the working people wield arms to fight

against any attempt to take back the gains of the revolution.

Therefore, even though the ruling classes arc not completely

expropriated—they continue to hold substantial econdmic

power under the mixed economy—their political power is

completely expropriated and any refusal by them to go along

with the decisions taken by the revolutionary government is

met with further expropriation, thereby deepening the revolu

tion and consolidating the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Now let us see how these armed workers and peasants

and even those who are not armed but come from the same

classes have set up their mass and class organisations. We

will mention five of them here: (1) the Sandinista Workers.

Confederation (CST) and (2) the Associaton of Rural

Workers (ATC). The CST and the ATC arc trade union

organisations representing about 75 per cent of urban and

rural wage workers. They provide an organic link by their

constant cooperation and thus materialising the workers and

peasants alliance. (3) The National Union of Farmers and

Rajichcrs/Stock Rearers (UNAG) (4) The Luisa Amanda

Espinoza Associationof Nicaraguan Women (AMLAE) (5)

The 19th July Sandinista Youth (JS 19) (Udry, 1985).

The Sandinista democracy rests in the first instance on

these mass organisations. Their power is not subordinated

to any other abstract concepts. Further, although the FSLN

commands political hegemony on the working people, it has

not brought the Nicaraguan society under one party strait

jacket. Instead, at the larger level it has opted for political

pluralism and has legally allowed all political parties, both

bourgeois and working class to operate, however, within the

framework of new realities. In November 1984 elections, the

opposition got 30 per cent of votes. This shows that

Nicaragua has opted for a different type of political struc

ture by allowing all political ideas io contend for hegemony

within the dictatorship of proletariat and has thus chosen

to face up to a series of problem that are relatively new in

the history of the transition to socialism.

This is why a worker and a farmer in Nicaragua is not

only a worker or a farmer, but also an armed defender of

•revolution, a soldier, and some of them even health workers

and/or leaders of their mass and class organisations. Thus,

the people’s participation in health care is an integral part

of people’s participation and contrdl over all the socio

economic processes in the Nicaraguan society.

June 1986

Health Care under Somoza

Nicaragua is one of the poorest countries in the region

with a population of thirty lakhs. In addition to poverty, il

literacy and ill-health, it faces a severe problem of structural

unemployment. Th'is is illustrated by the fact .that the entire

work force in Nicaragua grew only 6 per cent from 1961 to

1971. While the population aged 15 to 64 years grew by 40

per cent in the same period. This led to massive urbanisa

tion with a large proportion of the population living in

shantytowns (slums) on the edge of major cities. Roughly

one-third (ten lakhs) of the country’s total population is con

centrated in its capital, Managua. This is one of the reasons

why Nicaragua has 55 per cent of urban population despite

the central role played by agriculture in its economy (Garfield

and Rodriguez, 1985); 35 per cent of urban and 95 per cent

of rural population lacked access to potable water (Halperin

and Garfield, 1982).

As in any underdeveloped capitalist country, the official

health statistics of pre-1979 Nicaragua arc highly unreliable.

Halperin and Garfield (1982) point out that “the Somoza

regime paid so little attention to health matters that even such

basic data as birth and death certificates were collected for

only about 25 per cent of the population”. The official

estimate of the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) was given as

35 per 1000 live births ano was reported so in one of the

WHO documents of 1980. A survey conducted in a part of

rural Nicaragua in 1977, however, showed that the IMR in

the sample population corresponded to an IMR of the order

of 150 per 1000 live births (Heiby, 1981). Life expectancy at

brith was 52.9 years. Indeed, Nicaragua had the lowest life

expectancy at birth and one of the highest levels of the IMR

in the region.

Malaria was a major public health hazard. Upto 60 per

cent of the Nicaragua population had malaria during the

1930s. From 1934 to 1948, 22.4 per cent of all registered

deaths were due to malaria. Upto 70 per cent of hospital beds

were occupied by malaria patients during epidemics (Garfield

and Vermund, 1983). The national malaria control pro

gramme was started in 1947 and was converted into an

eradication programme, keeping with the change effected in

ternationally at the behest of international agencies. Accor

ding to Halperin and Garfield (1982), one-third of the people

contracted malaria at least once in their lives. One of the

important reasons for this high incidence of malaria was the

indiscriminate use of insecticides in cotton and rice farm

ing, leading to the Anopheles mosquito vector exhibiting

resistance to all insecticides in common use, including DDT

(dicophane), diedrin, malathion, propoxur and chlorofoxin.

As a result in 1978 approximately 4.4 persons per 1,000 con

tracted this disease. The revolutionary civil war paralysed the

health services and the incidence of malaria rose to 7.3 per

1,000 in 1979 and 9.4 per 1,000 in 1980 (Halperin and

Garfield, 1982). This forced the Nicaraguan government to

opt for, as an emergency measure, mass anti-malarial drug

administration in 1981..

. Besides malaria, tuberculosis and parasitism were endemic.

Among the top ten killers of children were diarrhoea, tetanus,

measles, whooping cough and malaria. Some of the major

causes of death in 1973. are shown in Table 1:

5

indigenous medical practices and what the revolutionary

government is doing about it.

Table 1

Causes of Death

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Infectious -and parasitic diseases

Diarrhoeal diseases

Pneumonia and influenza

Avitaminosis and other nutritional

diseases

Homicide and war

Poorly defined causes

Source'. Garfield and Rodriguez, 1985.)

Death Rate

per 100,000

population

(1973)

141.8

97.0

190.5

2.1

24.0

151.8

An official community health experiment was carried

out in Nicaragua from 1976 to 1978. In this programme,.768

parteras (traditional birth attendants) were trained in six-day ’

courses, to carry out in theircommunity improved obstetrical

care, treatment of diarrhoea in children using packets of oral

rehydration salts, provision of contraceptives, provision of •

aspirin for fever and pain

so on. A trained partera was

given a free he?’**' l';*

..as required threafter to purchase

supplies through me local government clinics. At the end of

the experiment in 1978, about 40 per cent of the Parteras

had already dropped out (Heiby, 1981). The government was

so disinterested in the programme that it did not make any

serious effort to keep it going nor did it carry out any follow

up work.

•

Thus, what the revolution inherited was poverty illhealth, unemployment and rickety health services. In addi

tion, it also had to (1) care for the families of the 50,000 dead

in the civil war and the 100,000 wounded people and their ■

families, and cope with (2) considerable destruction ol

industry (Somoza bombed his own industries to thwart

revolution), disorganisation of two agricultural cycles.with

repercussions on food supplies and exports (GDP per capita

had declined to levels of. 17 years before), a massive foreign

debt, a near-total lack of foreign currencies and high infla

tion, (3) a poorly developed economy (much less developed

than Cuba in 19’59), (4) dependence on agro-exports for

earning foreign exchange, and (5) the ever-present threat of

economic sanctions and even of a blockade (Fourth Inter

national, 1985).

Some studies in malnutrition have estimated that bet

ween 46 and S3 per cent of Nicaraguan children were

malnourished. The same studies have indicated that a high

proportion of these children (25 to 45 per cent) had the more

severe secondary and tertiary types of malnutrition (Halperin

and Garfield, 1982).

Health Services: A decade before the revolution four

separate agencies and independent health ministry offices

in each province ran in Nicaraguan health,system. All four

agencies.and provincial officies of the health ministry func

tioned independently without any coordination. The ministry

of health had the main responsibility for rural health care.

For the salaried population, the Nicaraguan Social

Security Institute (1NSS) was established in 1957. Twenty

years later it Served only 16 per cent of the economically

active population and only 8.4 per cent of the country’s total

population. (Garfield and Taboada, 1984). Several churches

ran highly respected hospitals, but for the most part they Post-revolutionary Reforms

Many persons mistakenly think that immediately after

treated only those who could pay cash. The National Guard

had relatively good medical services, including most the proletarian revolution, the revolutionary regime brings

specialities, through a system of hospitals and clinics of its under state ownership all the means of production and

own.

services. Actually, while the state takes upon itself the respon

. Health Expenditure: Of all the expenditure in the health sibility of providing adequate health care, it docs not do so’

sector, jhe INSS commanded 50 per cent, the ministry of by any such overnight take-over of the services. The seizure

health only 16 per cent and other local agencies, charitable of state power andjhe nationalisation of the core of the

and private insurance groups the remaining 34 per cent economy can be timed by the day of the insurrection, but

(Garfield and Taboda, 1984). This way, a great divide was the actual consolidation of the revolution takes place in

created between a tiny minority of insured salaried workers course of time,- by a process in which the continuing class

(mainly white collar government employees) and the over struggle within the country and internationally plays a pro

whelming majority of non-insured. Preventive care was minent role. Even decades after the revolution in these coun

neglected, save for some disorganised attempts in respect of tries, small-scale private producers (artisans, private medical

malaria. All of the INSS and much of the rtiinistry’s budget practitioners, small capitalists, etc) are not completely

was devoted to curative care. Of the approximately 13 dollars expropriated. They survive as a marginalised sector and

per capita spent in Nicaragua in 1972 by the health sector, under restrictions. Therefore, an attempt to characterise a

only about 3.15 dollars went for preventive care (Garfield revolution in its initial years only on'.the basis of the pro

and Taboada, 1984)..

portion of (he state-dwned economy and services-could lead

Health Personnel’. The Somoza dictatorship considered to wrong conclusions. ’What is decisive is the ideology anc

students, especially in the health professions, a potentially class nature of-the revolution’s leading organisation, the

subversive group and tried to limit their number. Thus., actual role played by the new state in the ongoing class

Nicaragua had only one medical school with 73 students in struggle does the state side with workers and farmers? Does

a class. The total number of doctors was 1,300 and there were it expropriate those propertied classes who go against the

only 43 professional nurses per 100 doctors. Not surprisingly, people’s interest?—and the development and extension of the

80 per cent of rural health manpower consisted of folk workers’ and farmers’ power and control over all aspects of

healers. We do not have any information about their • the new social structure.'

Radical Journal of Health

The continuing presence of private sector in the been carried out since 1979. The new six-ycar- course con- ’

economy thus does not disprove the proletarian character sists of clinical service, leaching, administration and research.

ol the revolution, although such a sector docs have subver For imparting such integrated medical training, ‘work-study

sive potential. This makes it more imperative for the revolu programmes’ arc instituted wherein the student is required

tionary stale to deepen the class struggle. The stale of reform to assist from the outset in supervised public education pro

of the health care system in Nicaragua is also at this stage jects, in community surveys to asses health needs, door-toonly. Although the state has undertaken full responsibility door programmes to give immunisations, serve as an ad

tor providing health care (sec basic principles cited above), ministrative assistant in local public health offices, etc. The

and it has achieved astounding success in improving health student is also placed in work settings to learn about occupa

•care, this has not been done by sweeping abolition of the tional health and in outpatient settings to learn about preven

private sector and private practice. The trend, however, is tive maternal and child health services. On the other hand,

clear. The state is for people’s health care. Those health the clinical rotations are almost always hospital-based, thus

personnel who want to continue in the old way of looting creating a discrepancy between the primary care, goal and

people, will not be allowed to do so. First restriction and (hen, hospital based training practices. This discrepancy is increas

if necessary, expropriation.

ingly being questioned by the teachers and students

Health Structure; Immediately after the revolution, the (Braveman and Roemer, 1985).

previously separate health agencies were integrated within

Nicaragua has six nursing schools with five times the

the Ministry of Health (MINSA) and a United National prc-1979 enrolment. The educational qualification required

Health System was started.

for enrolment has been drastically lowered. For Auxiliary

Doctors’ Response: Nicaragua had one medical school Nurses the person should only be literate and ten months’

in Leon and a second one was opened in Managua in 1981. training is given. Technical Nurses require primary school

By 1983, 2,240 medical students were undergoing training education and are given two years’ training. While profes

in these schools, an increase by four times over the 1978 level sional Nurses require secondary school graduation and arc

(Braveman and Roemer, 1985). Unlike in the case of Cuba, given three years’ training (Braveman and Roemer, 1985). At

only about 300 of the total 1,300 doctors left the country this rate it is certain that Nicaragua will correct the present.

due to the revolution. This was largely because private prac adverse nurse-doctor ratio very rapidly.

tice was allowed. Before the revolution, about 65 per cent

One of the earliest programmes stdrted by the MINSA

of the doctors were paid for some public service, but for most was training paramedical health aides, catted-brigadistas, who

of them this constituted only a few hours a day and the rest were selected from the youth organisations. They received

of the time they were engaged in private practice. After several.months’ training and were sent to isolated rural areas.

revolution they were pressurised to fulfill their contracted They were to serve tor at least two years after which they

time and increase their scheduled public practice to at least would be eligible for professional training. In fact many of

six hours a day. Their salaries were standardised (Garfield them went on to become health educators and medical

and Taboada, 1984).

students. The doctors forcefully opposed this programme and

After revolution, the doctors’ official organisation so it was revised. The.revised programme look up mobilisa

Federacion de Sociedades Medicas de Nicaragua tion of a large number of people in the immunisation, •

(FESOMENIC), which is a leader of the Federation of malaria prophylaxis and sanitation campaigns which were

Professional Organisations (CONAPRO) and has the back launched in 1981. The campaign included a short-term train

ing of the propertied strata, increased its political activities. ing course and public health education. It is estimated that

In 1980 when the government started discussing a law to upto 10 per cent of the country’s population was mobilised

regulate professional activities, it opposed it looth-and-nail. as health volunteers in these campaigns. The class and mass

It organised a one-day walk-out and even threatened mass •organisations listed earlier in this article actively participated

emigration to Miami. The government retreated by making and provided volunteers. They also promoted the formation

the law less specific. Nevertheless, the government passed the of local, regional and national community, health councils

law and for the first time made the doctors and other pro which are now active throughout the country (Garfield and

fessionals accept the government’s right to regulate their pro Taboada, 1984).

• ..

fessions. This tussle at the same time divided the profes

But a campaign means a programme that ends at one

sionals into the progressive and the conservative camps and point of time. This is not allowed to' happen by converting

in July 1981 a formal split look place The progressives could the activity into permanent-work by providing extensivemaintain official recognition and this ultimately forced the training to a section of the volunteers. There are now 25,000

conscrtativcs to rejoin the organisation (Garfield and of these permanent but volunteer brigadistas comprising

Taboada, 1984).

about 1 per cent of the total population (Garfield and

Personnel and Training: International assistance has Taboada, 1984). This supports our earlier contention that

greatly helped Nicaragua to fill up deficiencies in the number many of the workers and peasants are armed defenders of

of personnel. There arc about 800 foreign health workers in the revolution and also health workers. People’s participa

Nicaragua, coming mainly from Cuba, Latin America and tion is not a cosmetic exercise, but is elevated to self-activity

Western Europe. Cuba and the Pan American Health by the people to decide the condition of their lives.

Organisation have also greatly assisted in leaching

Achievements of (he Campaigns: As mentioned earlier,

programmes. .

during and after the civil war, the incidence of malaria in

A complete overhauling of the medical curriculum has creased so much that there was no alternative but to take

June 1986

7

up mass campaigns to bring it under control. The govern

ment opted for Mass Drug Administration (MDA) in 1981.

Three ambitious goals were set: (1) to prevent new cases, (2)

to cure subclinical cases, and (3) to reduce the transmission.

For this purpose, *70,000 voluntary workers, brigadistas, were

trained. These volunteers recruited many helpers. A malaria

census was carried out in which 87 per cent were covered.

The drugs were given to an estimated 19,00,000 people. More

than 80 lakh does of chlorbque and primaquine were

distributed in October 1981.

As a result, the total number of malaria cases fell con

siderably from November 1981 to February 1982. However,

the incidence of P.Vivax cases returned to endemic level by

March 1982, while that of P.falciparum stayed below endemic

level for three more months. The net result was that if we

take the average of the previous two years’ incidence rates

as the baseline, there were 9,200 fewer cases of malaria than

expected during the four months of reduction in general in

cidence. It is clear from this that the objectives of preven

tion and cure of malaria infection were better realised than

that bf reducing transmission, as the MDA could not reduce

transmission to a ‘break point’ below which malaria eradica

tion could occur (Garfield ancLVermund, 1983). This shows

that even such a massive exercise could not realise the

theoretically possible decisive break in the chain of infection.

Compared to this moderate success o.f the MDA cam

paign, the immunisation campaign was a resounding suc

cess. BCG vaccinationis given at birth, and the three-fold

increase in coverage since 1980 reflects .a huge expansion in

maternal care. Diptheria-pertusis tetanus (DPT) immunisa

tion is given at health centres and health posts as part of

routine child growth and development services. The DPT

coverage is increasing at an average rate of 30 per cent per

year. However, this increase is not so spectacular. Measles

vaccination reches 60 per cent of children in the first year

of life and.85 per cent before their sixth birthday (Williams,

1985).

.

The key to this success in immunisation is a mass cam

paign through holding regular ‘health days’ all over the coun

try. For health days, 20,000 volunteer brigadistas have been

trained in vaccination, health education, etc. On health days

vaccinations are done between 7 am to 6 pm with schools,

community buildings and health facilities as assembly points

finishing with a house-to-house' sweep through the

neighbourhood. The results are announced through mass

media (Wiltjams, 1985). Table 2 shows tfeie immunisation

coverage.

Table 2: Estimated Immunisation Coverage of

Children unT>er 12 Months

Immunisation

BCG

DPT

Poliomyelitis

Measles

Percentage Coverage in

1980

1984

33

. 15.

20

15

97

33

76.

60

Source'. Ministry bf Health and UNICEF Office, Managua

(as givenin Williams, 1985).

Health Financing’and Facilities: Government funds

directly related to the provision of health care jumped from

">00 million cordobas in 1981 and reached an estimated 1.-593

million cordobas in 1983. In 1981, the government budget

for health was 12 per cent of all public spending (Garfield

and Taboada, 1984).

In the last months of the revolutionary war, Somoza’s

National Guard destroyed four hospitals, seriously damag

ed five others and looted four more. Post-revolutionary

reconstruction has nr- nrovided 18 hospital beds per 10,000

population 'ru

• v 4,829 hospital beds in Nicaragua, but

greater awareness and accessibility has increased their use.

Five hospitals with 1,078 beds are under construction (Gar

field and Halperin, 1983). To tackle problem of diarrhoea;

especially in infants, the government initially planned 170

rehydration centres, but popular demand and people’s ac

tion have brought 226 such centres into existence (Halperin

and Garfield, 1982). The availability of health services has

increased tremendously. Il is estimated that more than 80

per cent of the population now has some regular access to

medical care (Garfield and Taboada, 1984).

Health Condition. Finally, about some overall

achievements. The IMR has got reduced to 80 per 1,000 live

births. No case of polio has been reported since 1982 despite

an epidemic in neighbouring Honduras in 1984. Only 3 cases

of diptheria were reported in 1983. Neonatal tefanus.

however, still remains a significant problem (Williams, b985).

In short, the reforms in health care in Nicaragua show

people’s determination to collectively change society. The

future of the revolution is, however, not fully secure and is

threatened by internal and external dangers. This has hap

pened to all such revolutions. The Soviet. Union was invad

ed by several countries to destroy the Bolshevik Revolution:

Cuba had its Bay of Pigs invasion; Vietnam had to fight for*

decades for survival; Grenada was overpowered; Nicaragua

has been assaulted by the GIA sponsored contras and a par

tial blocade since 1981. The very fact that it has achieved

so much under conditions of a threat to its very survival and .

conlinous war since 1981 shows the revolution’s lasting power.

the new state’s mass-base and the preparedness of the-work

ing masses to sacrifice to preserve the gains of th'c revolu

tion, including the gains in health and health care. Never

theless, the war has its impact, and such protracted aggres

sion has consequences ior people's health. Epidemiology ol

war is an emerging subject and the war on Nicaragua has

made it much more relevant. Health professionals will have

to understand it more and more for the world is likely witness

more revolutionary upheavals, revolutionary crises, and im

perialist aggressions.

Health Consequences of War in Nicaragua

The Central American countries are under the grip ot

vio ence, more so since 1980. Violent death is the most com

mon cause of death in El Salvador, Guatemala and

Nicaragua since 1980. At least 40,00 people have been killed

i ”i

lta^ an^ dealh squads in El Salvador (population 47

lakhs) and many more have been killed in bombing .and other

41 takhc? 1S eStin2alcd lhat 20»000 Gautemalans (population

hv thp

most o them indigenous tribes, have been killed

by the army In the last three years. The war takes a toll mainly

Radical\journal of Health

of young men. This is illustrated by the fad that although terms of availability of health facilities, as the Nicaraguan

life expectancy at birth among Salvadoran women has risen Health Workers Union (FETSALUD) reported to visiting

steadily, reaching 67.7 years in 1980, it fell remarkably for American physicians, the increase the in the number of

Salvadorar men from 58.4 years in 1978 to 52 years in 1980. civilians and soldiers wounded in the war has strained existing

More than 1,20,000 Central Americans have died from war- health facilities, leaving less resources for normal civilian

related causes since 1978. This amounts to a 10 per cent rise needs (Siegel, 1985).

Further increase in the health budget has been suspend- .

in mortality above expected levels during this period. It is

estimated that more’than a million Centra] American live cd due to increase in military spending, the budget for which

as refugees within the region and a million have fled to increased from 18 per cent in 1982 to 25 per cent in 1984.

America (Garfield and Rodriguez, 1985). This is how im Not only that, 20-25 per cent of Managua’s health workers

perialism is trying to crush the hopes and rebellion of peo are-at the war front, actually fighting with arms and many

ple in Central America, who have been inspired by the of them arc getting killed. This has necessitated training of

Nicaragua revolution. The effects of imperialist aggression new health personnel.

The economic embargo on Nicaragua by the US has

on Nicaragua are no less tragic.

More than 100,000 persons were wounded in the revolu devastating consequences for health care. Immediately after

tionary war in Nicaragua and 50,000 lost their lives. After the revolution, there was a crisis in the availability of phar

the revolution, the CIA-backed contra attacks have, between maceuticals. The foreign drug companies wanted the debt

January 19S0 and January 1986, killed 3,999 persons, wound incurred by the Somoza government to be settled before sen

ed 4.542 persons and 3.791 persons have been kidnapped. ding any more drugs. The Sandinista government had to

In 1985 alone, 1,852 persons’ were wounded. 1,463 were killed accept responsibility for the debts in exchange for favourable

and 1,455 kidnapped, indicating the counter-revolutionaries terms of repayment (Halperin and Garfield, 1982). Another

who have been killed in the armed conflicts—they are also major problem is the lack of spare parts for medical equip

victims of US aggression—the number of casualties totals ment. Much of the machinery is made in the US, but shor

23,822 persons including 13,930 dead (Ortega, 1986). The tage of US dollars as a-result of the war makes acquisition

president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega, in his recent speech of replacement parts difficult (Siegel, et al, 1985). Thus, when

to the National Assembly said that the total number of peo equipment breaks, it may remain out of commission or one

ple killed as a result of the US policy of terrorism against piece of equipment must be cannibalised to fix another

Nicaragua would be equivalent, as a proportion of the (Hclperin and Garfield, 1982).

In 1983, agricultural losses directly related to the war

population, to some 1,03,000 dead for the US (Ortega, 1986).

totalled 10 million dollars. Since 1981, total destruction

Ortega also gave information about other losses:

1. In 1985, aggression increased Nicaragua’s balance of pay related to health has been valued at over 70 million dollars

ment deficit by 108 million US dollars, the trade deficit rose (Siegel, et al, 1985).

by S 89 million and the capital deficit by S 19 million.

Effects on Diseases

2. A total of 120,324 people have been displaced from their

The term ‘epidemiology of aggression’ was first used

lands by the war, of these, 33,000 have been relocated to 55

by a group of doctors connected with Regional Leishmaniasis

urban and rural settlements.

3. Health services to 250,000 people have been impaired due Group in Nicaragua, to analyse health data ascribablc to the

to the damages caused to 55 health units, including one US aggression in 1982. Before 1979 leishmaniasis was known

to exist in Nicaragua but was not reported to the WHO. After

hospital and four health centres.

4. 48 schools have been destroyed and 502 other education the revolution reported cases increased and came to ocupy

centres can no longer operate because they arc located in war the fifth rank among all notified infectious diseases. When

zones; as a result, a total of 60,240 elementary and 30,120 the Leishmaniasis Group started a study of this disease in

adult education students arc no longer,able to attend classes. 1982 in one region, the study was violently interrupted after

5. In the area of social services, the mercenaries have 24 hours by a contra attack in which several people were kill

destroyed four rural child care centres, three nutrition cen ed, including Dr. Pierre Grosjean, one of the two European

tres for children and two offices of the Nicaraguan Social volunteer physicians (Morelli, et al, 1985).

Security Institute. This has directly affected services to 2,222

One aspect of the epidemiology of war is the impossibility

children and elderly people.

of obtaining basic data. Cases registered in this region pro

The strength of the Nicaraguan revolution lies in peo gressively increased from 1980 (143 cases) to 1982 (2,107

ple’s power and in its accomplishments in the fields of health, cases); since 1982, with the intensified war activities, the

education (the revolution’s strategy of imparting education number of notified cases fell to 1.054 in 1983 and 806 in 1984.

to all has been most successful), nutrition, employment, etc. This is not due to actual decrease in number of cases but

The counter-revolutionary contra mercenaries know this. due to destruction of facilities, less access to services and

Hence health and educational centres and health func migration. Another aspect of this epidemiology is related to

tionaries arc made special'targets of attacks. At least 22 troop movements. Non-immune people have the clinical

health workers (including two European volunter physicians), manifestations when they enter, in troop movements, the

medical students, nurses, malaria control workers, health natural environment of leishmaniasis. This Can be seen from

educators and vaccination campaign workers have been killed age-sex distribution: the significantly high incidence usually

while delivering health care (Siegel et al, 1985). Garfield seen in under 5s has shifted to appear in males aged 15-30

(1985) puts the number of health workers killed at 31. In years. The third aspect is related to migration. People living

June 1986

in endemic areas often resettle, because of the war, in non

endemic areas, resulting in the first appearance of the disease

in those zones. Thus, as the Leishmaniaris Group puts it,

in the war-affected northern regions of the country, aggres

sion and leishmaniaris, indeed, coincide.‘cpidcmiologically’

(Morelli, 1985).

Before we conlude, a mention should be made of the

psychological effects of war. The Americans, for instance

still suffer from (he psychological effects of (he Vietnam war

and a numbr of studies are still being carried out to assess

the increased number of vehicular accidents and suicides

amongst Americans who were drafted to fight for US im

perialism in Vietnam. As reported by Dr. Felipe Sarti, the

chief psychologist at a psychiatric day centre in a pool suburb

of Managua, approximately 25 per cent of all patients show

depressive illnesses connected with the war.. This depression

is particularly prevalent among parents and siblings of

soldiers who' have been killed or sent to the front (Scigcl,

et al, 1985).

The US sponsored aggression is still continuing and no

end to it seems likely in the near future. Such a situation can

jeopardise (he revolution in the long-term. This annihilation

of revolution must stop. The US administration knows that

if it opts for direct intervention, it won’t be any cakewalk.

The working masses arc armed and they will fight till (he

last person. And hence this new strategy of protracted

aggression combined with economic harassment and inter

nal sabotage through the still-unexpropriated big strata of

the former ruling classes. The danger is real. If a massive

counter revolutionary attack is mounted by all of them it

will have a chilling effect on the revolutionary movement all

over the world. Even if such an attack fails, there are bound

to be major distortions in the revolution. Its democratic

fermer. may get lost. A massive bureaucratic state apparatus

may emerge and with the best class-conscious workers and

peasants dead in the war, such an apparatus can get con

solidated. International solidarity is a need of the hour.

Many health professionals have reacted with revolu

tionary zeal to this need. Today, over 900 internationalist

health workers are helping the revolution. They are from

Cuba, Latin America, Mexico and Europe. Many more can

and should join. If we allow imperialism to roll back this

revolution, as it did in Grenada, history will not forgive us.

No matter how- strong the justification for localist thinking

and local-based activity, this international defeat will affect

all of us sooner or later. We must say, “Imperialism—hands

off Nicaragua”.

References

Braveman, Paula and Roemer, Milion, “Health Personnel Training in

the Nicaraguan Health System”, International Journal of Health Ser

vices, 1985, 15(4): 699-705.

Dcvilliers, Claude, “Democratic Elections in War Economy”, Interna-.

tional Viewpoint, Paris, 1984, 62 (October 20): 6-10.

Fourth International, World Congress Resolutions of, “The Cental

American Revolution”, International Viewpoint, Paris, 1985, (Special

issue): 89-109

Garfield, Richard, “Health Consequences of War in Nicaragua”, Lancet,

1985, 8451 (August 17): 392.

Garfield. Richard and Halperin, Devid, “Health Care in Nicaragua”,

ne Hew Enstond Journal of Meiticine. 1983, 309 (July 21): 193.

Garfield', Richard and Rodriguez. Petro, "Heahh and Heahh Serviees

in Central America", Journal of Amencan Medical As.sociudo,,

(JAMA) 1985. 254 (7): 936-943.

Ga field, Richard and Taboada. Eugene "Health Services Reforms i„

Revolutionary Nicaragua". American Journal of Pubhc Health, 1984,

74 (10): 1138-1144.

.

.

.

Garfield Richard. Vermund. Sten, "Changes tn Malarta Inctdence after

' Mass’Drug Administration in Nicaragua", Lancet, 1983 (August 27):

Halperin David, Garfield. Richard, “Developments in Health Care in

Nicaragua”, The New England Journal of Medicine, 1982, 307

(August 5): 388-392.

Hciby James. “Low-cost Health Delivery Systems: Lessons from

Nicaragua”. American Journal oj Public Health. 1981, 71 (5): 514-519.

Morelli. Rosclla, Missoni, Edurdo. Solan. .Maria Felisa De (Regional

Leishmaniasis Grotip) “Epidemiology in Nicaragua , Lancet, 1985,

8454 (September 7): 556.

Onega. Daniel, (February 21, 1986 Speech to the National Assembly)

Barricade International, Managua, February 27, 1986. Excerpts

Reported in Intrcontinental Press, New York, 1986, (April 7): 217.

Siegel, David. “The Epidemiology of Aggression: The Effects of War

on Health Care”, Nicaragua Perspectives, 1985 (Spring—Summer):

21-24.

• .

Siegel, David, Baron Robert, Epstein Paul, “The Epidemiology of Ag

gression: Health Consequences of War in Nicaragua” Lancet, 1985,

8444 (June 29): 1492-1493.

Udry, CharlesrAndre, “The Sandinista Revolution and Mass Democracy"

International Viewpoint, 1985 76 (May 20): 9-16.

Udry, Charles Andre, “A major step forward for the Revolution” Inter

national Viewpoint, 1986 (April 21): 13-14.

Weber. Henri, "Nicaragua: The Sandinista Revolution”, Verso, London.

1981.

Weissberg, Arnold., “Nicaragua: An Introduction to the Sandinista

Revolution", Pathfinder Press, New York, 1981.

Williams. Glen, "Immunisation in Nicaragua", Lancet. 1985, 8458

(October 5): 780.

Amar Jcsani

2/72 ONGC Flats t

Reclamation’

Bombay 400 050

RADICAL JOURNAL OF HEALTH

Forthcoming Issues

September 1986: Vol I no 2.- Primary Health Care

December 1986; Vol I no 3; State Sector in

Health Care

March 1987: Vol I no 4

June 1987: Vol II no 1

September 1987: VoHlno2:

Medical Technology

A

Agrarian Develop

ment and Health

Health Issue in

People’s Movement

10

Radical Journal of Health

Medical Care and Health under State Socialism

bob deacon

1 he transformation of the social relationships of welfare is central to socialist and communist social policy and

may be thought through in •relation to six key aspects of social policy: (1) the priority afforded social policy,

(2) the form of control over welfare provision, (3) the agency of welfare provision, (4) the nature of the relation

ship between welfare provider and user, (5) the rationing system adopted by (he welfare institutions concerned,

ana (6) the assumption embodied in the policy regarding the sexual division of labour. This article reviews medical

-are and health policy in three countries, (he Soviet Union, Hungary and Poland from the standpoint of a perspective

of ideal socialist and communist medical care and health policy derived from an analysis of Marxist and allied

critiques of capitalist medical care policy and theoretical work on socialist social policy. The author concludes

that medical care policy in all three countries exhibits very few characteristics of socialist medical care. It also

examines the possibility (for the moment suppressed) provided by the Solidarity movement in Pyland of a new

development toward a more genuine socialist medical care and health policy.

The article has been slightly abridged from (he International Journal of Health Services Volume 14, number

3, 1984 and excludes the detailed review of medical policy in Hungary.

Socialist Medical Care Policy

The aim of this article is both to explicate a socialist con

ception of ideal medical care policy and to review medical

care policies in the Soviet Union, Hungary and Poland to

sec whether they provide concrete examples of socialist

medical care.

It is clear from George and Manning’s (1) review of the

few specific statements on socialism and health made by

Marx, Engels, and Lenin that their emphasis is on those

causes of ill-health located in the nature of capitalist socie

ty. As an example take Lenin’s view that “thousands and tens

of thousands of men and women, who toil all their lives to

create wealth for others, perish from starvation and constant

malnutrition, die prematurely from disease caused by horri

ble working conditions by wretched housing and overwork”

(2). A socialist health policy would therefore be concerned

primarily to prevent avoidable disease. There is far less in

their writings on the particular form ofcurativc health ser

vice that should be provided to cope with unprcvcntablc

disease.

Few subsequent Marxist theorists, addressing the nature

of socialism have had anything specific to say about medical

care. Bahro (3) is an exception here. His discussion'of the

need to alter the division of labour radically under socialism

is illustrated by the example of the organisation of work in

’a hospital: “We can just as well imagine the everyday situa

tion in a hospital, to take an example from a different sphere,

one still more strongly burdened with the prejudices of the

traditional division of labour, in which the entire staff con

sisted of people with full medical training, or other pertinent

qualification, who also took part in all nursing and ancillary

work and in social and economic functions as well” This twin

concern with both preventive medicine—the fact that it will

become a high priority under socialism—and the altered

forn) of curative medical care will recur as (he Conception

of socialist medical care emerges in this article.

t'

Lesley Doyal’s (4) excellent analysis of the causes .of, and

ways of curing, ill-health under capitalism is structured

around these twin concerns. Her brief postscript to The

Political Economy of Health, where she considers the im

plications of this analysis for the struggle for a healthier

society, discusses both aspects. On the question of preven

tion of ill-health under socialism, she is sensibly cautious:

June 1986

Naturally we would not argue that a transformation of the mode

of production would abolish illness—people will always become

sick and die. But what we'can show are the ways in which poten

tially avoidable illness has become prevalent under capitalism ...

[It follows that] the demand for health is in itself a revolutionary

demand.

This concern with preventing avoidable ill-health is a

touchstone of socialist policy. It would reach into every

corner of working and domestic life. Not only would each

work process be evaluated from the standpoint of whether

it made workers ill or not, but also such diverse aspects of

life as food, housing, transportation, and personal relation

ships would be affected far more than under capitalism by

considerations of their health-enhancing potential. Changes

in life-style in relation to all of these things would be a mat

ter of general public concern and action. Necessary economic

and social’changes that would enable.pcoplc to live, eat, and

relate differently would be a matter of medical policy.

On the form of curative medical care under socialism,

Doyal (4) writes:

'The struggle must therefore go beyond the immediate demand

for more state-organised medicine, towards a critical re-evalnation

of the more qualitative aspects of the current organisationof

medicine and a redefinition of our health needs; This is not. of

course, to suggest that in a socialist society all existing medical

knowledge and skills would simply be abandoned in favour of

something called “proletarian medicine” . .. [But] no technology

would be used uncritically and without some assessment of its

value according to criteria which had been democratically decid

ed t pon ... Hence a socialist health service would not only have

to provide equal access to medical care but would also have to

address itself seriously to such problems as how to demystify

medical knowledge and how to break down barriers of authority

and status both among health workers’' themselves and also.