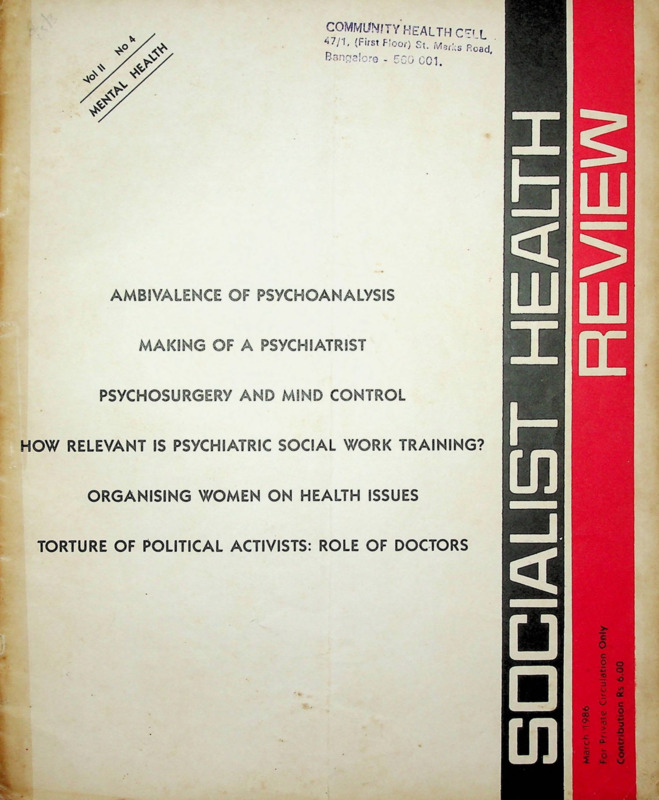

Socialist Health Review 1986 Vol. 2, No. 4, March Mental Health.pdf.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

COMMUNITY HEALTH C7' L

47/'!-

Fioor) St. M9r;;s RoacJ

Bangalore - EOG CC1.

AMBIVALENCE OF PSYCHOANALYSIS

MAKING OF A PSYCHIATRIST

PSYCHOSURGERY AND MIND CONTROL

HOW RELEVANT IS PSYCHIATRIC SOCIAL WORK TRAINING?

ORGANISING WOMEN ON HEALTH ISSUES

TORTURE OF POLITICAL ACTIVISTS: ROLE OF DOCTORS

Vol II Number 4

MENTAL HEALTH

153

Editorial Perspective

MENTAL HEALTH AND SOCIETY

Ravi Duggal

I

u.

157

PSYCHIATRY. STATE OF THE ART

Dilip Joshi

160

THE HELPING PROFESSION. IS IT REALLY HELPFUL

fO

U

XZ

Annie George

163

THE AMBIVALENCE OF PSYCHOANALYSIS

2

y

o

<n

Working Editors:

Amar Jesani, Manisha Gupte,

Padma Prakash, Ravi Duggal

Editorial Collective:

Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (A P),

Imrana Quadeer, Sathyamala C (Delhi), Dhruv Mankad

(Karnataka), Binayak Sen, Mira Sadgopal (M P),

Anant Phadke, Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar,

Srilatha Batliwala (Maharashtra), Amar Singh Azad

(Punjab), Smarajit Jana and Sujit Das (West Bengal)

David Ingelby

171

THE MAKING OF A PSYCHIATRIST

Anand Nadkarni

179

Problems of Praxis

OUR BODIES, OURSELVES

Organising Women on Health Issues

Gabriele Dietrich

Reports

177

DOCTORS AND TORTURE

A Report on Chile

Editorial Correspondence:

185

Socialist Health Review,

C/o 19, June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay - 400 050 India

POLITICS OF INFORMATION

Printed at: Modern Arts and Industries, 151, A-Z

Industiral Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel,

Bombay 400 013.

Rosalie Bertel I

Book Reviews

173

DIFFERENT VOICES

Nalini

175

Annual Contribution Rates:

Rs. 30/- for individuals

Rs. 45/- for institutions

US dojlars 20 for US, Europe and Japan

US dollars 15 for other countries

We have special rates for developing countries.

Index to Volume II: 188

(Contributions to be made out in favour of Socialist

The views expressed in the signed articles do not

Health Review.)

necessarily reflect the views of the editors.

THE SORRY STORY OF PSYCHOSURGERY

Bindu T Desai

The Printed Word: 170

Editorial Perspective

Mental Health and Society

Nowadays, men often feel that their private lives are a series

of traps. They sense that within their everyday worlds, they

cannot overcome their troubles, and in this feeling, they are often

quite correct: what ordinary men are directly aware of and what

they try to do are bound by the private orbits in which they live;

their visions and their powers are limited to the close-up scenes

of job, family, neighbourhood; in other milieux, they move

vicariously and remain spectators. And the more aware they

become, however vaguely, of ambitions and of threats which

transcend their immediate locales, the more trapped they seem

to feel—C.Wright Mills in “The Sociological Imagination.”

THIS is the condition of modern man. In order to under

stand mental health and illness it is very important to know the

concept or nature of man within a given social milieu; for on

this depends the definition of what is mental health and illness,

the normal and the pathological. The human situation or human

existence in a social milieu thus becomes the key to understanding

mental health.

It is not necessary to go into the various conceptions held

historically but it should suffice to state that the definition of

mental health in a society is intimately related to the concept

of human in that society. These conceptions are the result of the

relations of production prevailing within a given society. They

have a direct bearing on the human situation and determine

mental health of individuals as well as classes. Marx described

this aptly in the ‘German Ideology’: “The production of ideas,

of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven

with the material activity and the material intercourse of men,

the language of real life. Conceiving, thinking, the mental inter

course of men, appear at this stage as the direct afflux from

their material behaviour. The same applies to mental produc

tion as expressed in the language of the politics, laws, morality,

religion, metaphysics of a people. Men are the producers of their

conceptions, ideas, etc. real, active men, as they are conditioned

by the definite development of their productive forces and of

the intercourse corresponding to these, upto its furthest forms.

Consciousness can never be anything else than conscious

existence, and the existence of men in their actual life-process.”

(Marx, 1956)

Thus, pathology stems from society itself and no amountof cure of an individual who manifests symptoms of being

mentlaly ill, will provide a complete solution to this sickness.

Mental helath is not a question “of the ‘adjustment’ of the

individual to his society, but, on the contrary it (requires) the

adjustment of society to the needs of man ... whether or not

the individual is healthy, is primarily not an individual matter

but depends on the structure of his society. A healthy society

furthers man’s capacity to love his fellow men, to work creatively,

to develop his reason and objectivity, to have a sense of self which

is based on the experience of his own productive powers. An

unhealthy society is one which creates mutual hostility, distrust,

which transforms man into an instrument of use and exploita

tion for others, which deprives him of a sense of self, except

inasmuch as he submits to others or becomes an automaton”

(Fromm, 1956). It is therefore clear that the understanding of

man’s psyche “must be based on the analysis of man’s needs

stemming from the conditions of his existence” (ibid).

Historical Background

In the past mental illness was generally the equivalent of

lunacy or madness but in post-industrial societies things are

March 1986

different. Understanding of mental health was earlier

dichotomised into being mad or being sane. Now the situation

has changed.

A change in the social formation cuts across the length and

breadth of a social structure and leaves none untouched. The

sphere of the human psyche too is affected. Traditional societies

are close-knit and therefore have a greater capacity for absorp

tion of distress, frustrations and conflicts that impinge upon

individuals because of prevailing class-relations. Family, clan and

community ties cushion members against them temporarily

releasing them (individuals) from the traps of daily living.

With the industrial and French revolutions the old order

received its death blow. Individuals, uprooted from their

traditional ties, had to face new realities of changed production

relations, but this time with little or no support from their family,

clan or community. The new production relations under

capitalism made alienation of man complete and mental health

acquired additional dimensions. It was no longer confined to

“madness” but smaller deviations from accepted norms became

equally important, because a mass society that was emerging

required stronger measures and mechanisms for social control

if the status quo had to stay undisturbed.

The first break came during the “Paris Commune” when

Philippe Pinel, a French physician, obtained permission of the

commune to treat inmates of asylums with kindness and

sympathy: instead of incurable lunatics they were now considered

as “sick” persons who were in need of treatment rather than

being evil and deserving punishment. Pinel’s therapeutic inter

vention advocated a moral treatment—treating afflicted persons

with care and concern and at the same time improving their

environment; patients were taught the value of w'ork, recreation,

religion, social activities and self-control (Bockoven, 1963).

Thus for the first time the theory of unadjustment to society

was put to practice and mental health henceforth became a

matter of adjusting the unadjusted through a process of

correction.

With further advancement of industrial society and

strengthening of capitalism, issues of mental health were no

longer confined to the lunatics, but increasingly neuroses began

to acquire a central focus. This was thanks to the weakening

of human ties and the process of alienation. Karl Marx described

this as the negation of productivity in that man (the worker)

can no longer “fulfill himself in his work but denies himself,

has a feeling of misery rather than wellbeing, does not develop

freely his mental and physical energies but is physically exhausted

and mentally debased” (Marx, 1967). The man who has thus

become subject to his alienated needs is “a mentally and

physically dehumanized being .. . the self-conscious and selfacting commodity” (ibid).

Through Marx’s writing it became clear that pathology

resided not in the individual but within the social system itself.

Mental illness originated in the pathological society and it was

society that needed a total transformation; man’s mental state

depended upon the nature of the social system.

However, this explanation was set aside as it was a challenge

that suggested the destruction of the existing system. Soon after

Marx, Max Weber’s verstehen approach came to the rescue of

capitalism. Weber upturned Marx and provided a foundation

for a new- explanation to emerge about man’s mentality. This

new break was that by Sigmund Freud who directed attention

to the intrapsychic life and emphasised the importance of the

153

unconscious. This psychology of the unconscious was indeed

“revolutionary” and path-breaking because until Freud

philosophers had always equated the mind with consciousness.

Freud’s now famous “ice-berg" theory revealed that “only a very

small part of what is mental is conscious; the rest is unconscious

made up of inadmissible and involuntary ideas which motivate

behaviour” (Appignanesi and Zarate, 1979).

Sigmund Freud

“Where id was, there shall ego be” was Freud’s way of

describing mental health. Id is the unconscious, governed by the

pleasure principle, and ego is the preconscious that emerges

because of the reality principle. These ideas of the unconscious

devolved around the oedipus complex which has generally

acquired the expression ‘father . .. murder, mother ... incest’. ”

In Freudism ‘libido’ plays the part of the mythical ‘caloric’ of

eighteenth century health mechanics, or of the ‘gravity’ of

Newtonian physics (Caudwell, 1971).

As a consequence, Freud’s obsession with sexuality

prevented him from using to advantage the contributions of

Marx to the understanding of human behaviour.

Freud’s sexual determinism is unrealistic. A child’s desire

for his mother’s breast and subsequently for her love is not an

incestuous response but that of hunger and emotional support;

for the child it is the mother who provides social, economic and

emotional security. Nor does the child see the father as a rival

or, in his unconscious, desire to murder him. The father’s role

as a patriarch bestowed by society is interpreted by the child as

a stranglehold on his freedom, creativity and object of security

(the mother), and therefore in his unconscious he seeks to

challenge it. A review of anthroplogical studies of matriarchal

societies may indicate possibilities to further substantiate and

support this critique of Freud’s conception.

Freud’s insight of the human psyche was based on an

understanding of the individual, and as a consequence his inter

pretations of mental manifestations suffered severely. He did not

see the individual’s psyche in the context of the social milieu

and therefore got trapped in the confines of the libido instinct.

Caudwell (1971) writes: “We must establish sociology

(Marxist) before we can establish psychology, just as we must

establish the laws of time and space before we can treat satisfac

torily of a single particle . ..” This Freud has failed to see. To

him all mental phenomena are simply the interaction and mutual

distortion of the instincts, of which culture and social organisa

tions are a projection, and yet this social environment, produced

by the instincts, is just what tortures and inhibits the instincts.

However, Freud’s influence on the various disciplines of the

human psyche is still very substantial. Freud’s contributions have

greatly been responsible for the extensive attention that mental

health receives, especially in western countries. It was largely

due to the emergence of Freudian psychoanalysis that the men

tal health movement became popular in the USA. Ttfe profes

sions of psychiatry and psychoanalysis subsequently acquired

a new importance in the field of medicine—they became big

business; a new technology developed around them—psycho

tropic drugs, psychosurgery, electrotherapy and the like. Until

the late sixties, this individualistic approach to mental illness

remained predominant.

Community Mental Health

At the turn of the seventies, by when the futility of.the in

dividualist approach was proved beyond doubt, things began

to change. The community basis of mental health was recognised

in the USA, but still the problem continued to be seen as one

154

of adjustment and unadjustment to society. The difference was

that it was not the individual that required to be adjusted, but

the entire community in which he lived. Thus, if the mentally

disturbed person came from a ghetto then psychiatric social

workers and other paramedics were to be used for resocialisa

tion of the immediate community of the mentally ill person;

these paramedic workers thus became a new arsenal in the forces

of social control.

It would be of interest to list out the characteristics of this

community mental health movement (Bloomy 1973): a) emphasis

on practice within the community rather man in institutional

settings such as menial hospitals; b) effort io provide services

and programmes directed at the total community rather than

individual patients; c) prevention services given higher priority

than therapeutic services; d) clinician offering indirect services—

consultation, mental health education, training of community

care givers (teachers, clergy, public health nurses, etc.)—rather

than working directly with patients, thus reaching larger number

of persons; e) innovative clinical strategies developed that more

promptly meet the menial health needs of larger number of

people (eg: crisis intervention) than was possible before; f) more

rational basis for developing specific programmes, based upon

a demographic analysis of the community being served, its unmet

mental health needs, identification of those persons who are at

special high risk for developing disordered behaviour; g) use of

new personnel—para-professionals—to supplement services

delivered by psychiatry, clinical psychology, psychiatric social

work and psychiatric nursing; h) committment to “community

control” dealing with community representatives in establishing

programmes; and i) identifying sources of stress within the com

munity and not simply within a sick person.

From the above listing it becomes clear that the community

mental health movement is no different from the community

health movement which aimed at developing resources in a

decentralized manner (at the community level) so that through

a new category of resource persons (such as paramedics, “volun

tary” agencies or NGOs, etc.) the ruling class could strengthen

mechanisms of social control, making them appear as self (or

community) regulatory and democratic; thus, preserving the

status quo. This fits in with the ‘circulation of elite’ framework

of Vilfred Pareto which is regarded as a weapon of the ruling

class (elites) to protect its own decadence “by introducing the

idea of new ‘social forces’ among the masses” (Bottomore, 1966).

Dimensions of Mental Health

In spite of the understanding that the social structure of

capitalism is in itself responsible for mental illness an overwhelm

ing proportion of psychiatrists and psychoanalysts continue to

treat mental illness as a primarily biological and behavioural

problem. Therapeutic systems that have been evolved in recent

years are therefore based on these assumptions and hence

inadequate.

The problem of mental health, though having its own

peculiarities, .is no different from that of health in general or

other social problems such as poverty, communalism, racism,

sexism, arms race, etc. All these problems, both under capitalism

and totalitarian socialism, are dealt with by society from the

perspective of commanding social control. In the case of men

tal illness those afflicted, i e. those not conforming to the norm,

are subjected to degradation, segregation and isolation (in

asylums) and more recently to incarceration, surgery, various

chemical treatment procedures and inhuman psychological

therapies, all directed towards driving home the point (to the

patient as well as the population at large) that norms of society

are sacred and unquestionable and must be followed at all cost.

Socialist Health Review

Those whose behaviour is not accounted for by the rule

following model face not only the above stated consequences

but are also labelled (eg: schizophrenic, hysterical, manicdepressive, catatonic) and stigmatised.

Erving Goffman calls this process ‘mortification’. He writes

(Goffman, 1984): “On admission to-an asylum the ‘patient’ is

stripped of his identity and any social support he enjoys. He

begins with a series of abasements, degradations, humiliations

and profanations of self. His self is systematically, if often

unintentionally, mortified. The staff employs procedures on

admission that complete this process of mortification—taking

of life history, photographing, weighing, fingerprinting, assigning

numbers, searching, listing personal possessions for storage, un

dressing, bathing, disinfecting, haircutting, issuing institutional

clothing, instructing as to rules, and assigning to quarters.”

Mental asylums are thus not very different from penal

institutions having as their main function the correction of un

adjusted behaviour; a process one may call resocialisation, which

at times may go to the extent of disculturation (rendering tem

porary incapacity of managing normal day to day life processes

when one gets out of the asylum).

It has been proved adequately that the therapeutic effects

of currently practised psychotherapy “are small or non-existent

and do not in any demonstrable way increase the rate of recovery

over that of a comparable group which receives no treatment

at all” (Eysenck, 1965). Thus, concludes John Ehrenreich that

psychiatry “is the branch of medicise which openly specialises

in the social control of deviant behaviour” (Ehrenreich, 1978);

and Thomas Szasz adds, “therapeutic interventions have two

faces; one is to heal the sick, the other is to control the wicked

. . contemporary medical practices—in all countries regardless

of their political make-up—often consist of complicated com

binations of treatment and social control . . . psychiatric

diagnoses are stigmatizing labels, phrased to resemble medical

diagnoses an'd applied to persons whose behaviour annoys or

offends others” (Szasz, 1974).

Beyond the asylums, in daily life, such interventions are

increasingly manifesting themselves, becauses problems which

are essentially social are being further appropriated by the

medical professions.

Mental illness is today generally classified into two

categories—psychoses and neuroses. “What most patients of

the first group suffer from is anxiety or depression, which if

it exists in a mild form, may only be neurosis. When it reaches

a severe stage, the person becomes totally abnormal, the opposite

extreme of depression is excitement or elation; when depression

and elation are manifest in a cycle, it is known as manicdepressive psychosis . . (Among neuroses) the commonest is

the anxiety neurosis, followed by obsessional neurosis, the com

pulsive urge to wash your hands, a fetish for cleanliness, an ab

normal concern about pollution. All the phobias too come under

this classification” (Chakraborty, 1985).

In a survey conducted recently in Greater Calcutta it was

found that 140 per 1000 persons suffer from some mental ill

ness or the other. Neuroses affect one in ten of the population.

The psychotic group is smaller, 16 per 1000 persons and half

of these are acute cases, incapable of functioning socially; this

is a very low figure in the international context, surprisingly so

in a city like Calcutta where one expects more psychotic problems

since the major factor, stress, is so overwhelmingly present (ibid).

Poverty and inhuman living conditions, especially in the

third world, play a significant role in determining mental health.

The working classes trapped in unfavourable work situations

an0 unhygienic conditions are probably the worst off due to their

alienated state. These cases of mental disturbances may not be

recorded as neuroses or psychoses but-the fact remains that their

March 1986

mental health is poor because even obtaining two square meals

is a struggle: which means a lot of insecurity and mental trauma.

Minority communities and underprivileged castes in India,

blacks in South Africa and a few western countries also live

under a fear psychoses that adversely affects their mental well

being. Women as a group have historically faced and continue

to experience mental trauma as a consequence of their place

ment in a patriarchal society. Males have throughout history

enjoyed the privilege of double values whereas females have

always been suppressed, their entire life-cycle being explained

in terms of their uterus and sexual function, especially from the

medical perspective (Ehrenreich and English, 1978). This results

in differences of interpretation of the same qualities held by men

and women. This is explained very well in a paper by Vibha

Parthasarathi (quoted by Kalpana Sharma in the Indian Express

Magazine, 27th October 1985). She writes that the quality of

being “open” is interpreted as “flexible” for men and “fickle”

for women; the quality of being “forthright” is interpreted as

“frank” in the case of men and “rude” in women; “resoluteness”

as “firm” for men and “rigid” for women; “unflinching” as

“strong-willed” for men and “stubborn” for women; and so on.

As a consequence these biased interpretations are in a large

measure responsible for the neuroses or psychoses in women.

The modern world of advertising in capitalist societies and

propaganda under both political systems promote values of the

status quo, numbing creativity of the human species, inculcating

a consumerism that drives man into becoming an automaton;

he either becomes obsessed with the advertised or propagated

norms and is labelled as an obedient or good citizen or he rejects

these norms and is classified as a deviant, and if the deviance

goes beyond the acceptable limits the person is labelled mentally

ill, thus becoming a prey to the therapies of psychiatrists and

psychoanalysts.

And finally patriarchy, which manifests itself through

exploitative production relations, also contributes to mental

pathology. Patriarchy, besides promoting sexism and suppres

sing women, promotes the idolatory of the clan, the race and

the nation; it is in Freudian terms an incestuous fixation. It is

manifested in our times in totalitarian regimes, bureaucratiza

tion and monopoly control of productive forces, among other

things. Fromm puts this point forcefully when he points out that

“nationalism is our form of incest, is our idolatory, is our

insanity; ‘patriotism’ is its cult” (Fromm, 1956). He furthers this

argument by indicating the similarities between capitalism and

totalitarian socialism. “Both systems are based on industrialisa

tion, their goal is ever-increasing economic efficiency and wealth.

They are societies run by a managerial class, and by professional

politicians. They both are thoroughly materialistic in their

outlook regardless of Christian ideology in the west and secular

messianism in the east. They organise man in a centralised

system, in large factories, political mass parties. Everybody is

a cog in the machine, and has to function smoothly. In the west,

this is achieved by methods of psychological conditioning, mass

suggestions, monetary rewards. In the east by all this, plus the

use of terror (or course, the west also uses terror—the ‘spectre

of Communism’). It is to be assumed that the more the Soviet

system develops economically, the less severely will it have to

exploit the majority of the population, hence the more can terror

be replaced by methods of psychological manipulation. The west

develops rapidly in the direction of Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’,

the east is today Orwell’s ‘1984’. But both systems tend to con

verge” (ibid).

Conclusions

Medicalisation of human mental situation, the social con

trol that goes with it, the alienation that class-relations generate

155

References

and the general drugging of the human mind through the modern

information systems have made an obedient cog of him/her.

Appignanesi, Richard and Oscar Zarate, Freud for Beginners, Pantheon

Then, if the currently prevailing social formations are largely

New York, 1979.

responsible for mental distress and frustrations, what does the Bloom,Books,

B L, Community Mental Health—A Historical and Critical

common man look towards?

Analysis, General Learning Press, New Jersey, 1973.

It is a difficult question to answer. Psychoanalysis, like Bockoven, J S, Moral Treatment in American Psychiatry, Springer, New

psychiatry, has failed in its purpose. In the west, as well as east

York, 1963.

bloc nations, the former has become only an appendage of the Bouomore, T B, Elites in Society, Penguin, 1966.

latter—which is highly medicalised. In the underdeveloped coun Caudwell. Christopher, Studies and Further Studies in a Dying Culture,

Monthly Review Press, 1971.

tries, especially of Asia and Africa, both psychoanalysis and

psychiatry have not found any significant roots, but in most of Chakraborty, Ajiia, Statesman, Calcutta, September 15, 1985.

these countries traditional ties are still strong enough to provide Ehrenreich, John, “Introduction” in the Cultural Crisis of Modern

Medicine (ed: John Ehrenreich), Monthly Review Press, New

comfort from the trappings of the social system.

Isn’t this itself an indicator that a community-life that is

York, 1978.

free from exploitative class relations, patriarchy and a centralised Ehrenreich, Barbara and Dierdre English, “The ‘sick’ women of the

and bureaucratised social control system will lead us towards

Upper Classes” in the Cultural Crisis of Modern Medicine (ed:

John Ehrenreich), op cit.

a mentally and socially healthier life?

It has indeed been a difficult theme to compile. All the Eysenck, H J, “Effects of Psychotherapy”, International Journal of

articles, except David Ingleby’s which has been reproduced from

Psychiatry, 1, 1965 (quoted in Ehrenreich, op cit).

a collection of the Radical Science Collective, are on psychiatry. Fromm, Erich, The Sane Society, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London,

We begin with Dilip Joshi’s Psychiatry: State of the Art, which

1956.

takes a look at present day psychiatry and its medicalisation.

Goffman, Erving, Asylums, Penguin, London, 1984.

Next we have Annie George’s article which reviews the train Marx, Karl, German Ideology (1845-46) reprinted in T B Bottomore and

ing programmes for medical and psychiatric social work and

M Rubel (ed) Karl Marx: Selected Writings, Penguin, 1963.

the role social workers play in psychotherapy. Psychoanalysis,

Marx,

Karl,

Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844), reprinted

that is extremely popular in west, is of little consequence (in

in Erich Fromm (ed), Marx’s Concept of Man, Fredrich Ungar,

practice) in our country—we present Ingleby’s article that deals

New York, 1967.

with ambivalence of psychoanalysis. This is followed by a short

piece on a psychiatrist, Anand Nadkarni’s experience in becom Szasz, Thomas, The Myth of Mental Illness, Harper and Row, New York,

1974.

ing one. We have two review articles, one on psychosurgery by

Bindu Desai and the other on gender differences by Nalini. In

Ravi Duggal

addition we have a long non-theme article on experiences of a

D-3, Refinery View

participatory research project on women and health by Gabriele

62-63, Mahul Road

Dietrich.

Chembur

ravi duggal

Bombay 400 074

LOCOST

Research Proposals Invited

LOCOST is a non profit trust that seeks to promote the rational use of medicines. We also supply quality

drugs to those working with rural/urban poor.

LOCOST offers support for research in the following areas: (1) Review of academic literature of specific

drug categories like analgesics, antispasmodics, haematinics, etc. and/or of controversial drugs like analgin,

etc. (2) Identification of information gaps in drug usage, ADR reporting, and designing and implementing

study to fill up gaps. (3) Review of contents, sales, prices, market share, etc. of top selling allopathic and

traditional medicines, fixed dose combinations, and over-the-counter products. (4) Review of promotional

literature of top selling formulations and companies. (5) Production/distribution bottlenecks of some essen

tial drugs like Vit. A, Rifampicin, INH, etc. (6) Price/sales trends of essential drugs. (7) Social cost benefit

analysis. (8) Prescription pattern studies and prescription guidance. (9) Perceptions and responses related

to communication processes and aids in drug selling and in drug therapy.

LOCOST’s priorities are towards rural poor and urban poor. Our budget is modest. Well designed short

term (one month to six months) research proposals, with concrete output on which action can be taken

are welcomed. Write to: LOCOST, GPO BOX 134, BARODA 390 001.

156

Socialist Health Review

Psychiatry: State off the Art

dilip joshi

Psychiatry, over the years, has been thoroughly medicafsed—it views mental illness as a purely biological problem.

The author presents a critique of the prevailing worldview of psychiatry and its practice. He argues in favour of a dis

counted alliance between psychiatry and medicine so that a more human psychiatry may be evolved.

MENTAL illness seems to be the major problem of our time.

In the United States doctors write 200 million prescriptions each

year for psychoactive drugs. Half to one million people are

treated for ‘schizophrenia’. In Britain, on the other hand, 25 per

cent of all hospital beds are occupied by the mentally ill. One

in nine men and one in six women can be expected to enter a

mental institution in their lifetime (Ingleby 1980).

Psychotherapy—Current Perspectives, a book written by

a group of psychotherapists, reveals an astounding scenario. The

child consults a school-counsellor, mother of the child attends

consciousness-raising groups for women, father attends ‘Tsessions at factory and the grand-parents participate in a

workshop conducted by a professional on ‘pains of ageing’.

Psychiatry today permeates and encompasses all significant

events in human life. (Cottle and Whitten, 1980). On the other

hand within psychiatry there is no consensus about:

(a) What are mental illnesses? (b) Who should treat them?

(c) What are the means (how to?) and what are the ends? (What

is cure?)

We have a vast amount of literature on mental illness com

pared to our inadequate understanding about it. Is there

something fundamentally wrong? This article takes up these

issues and examines them critically.

ing that whole world is against you, etc.) is accompanied by a

change in body chemistry (excess of dopamine in brain) one can

not conclude that excess of dopamine is the cause of this

behaviour or experience because:

(a) One considers excess of dopamine as abnormal only because

one took the behaviour or experience as abnormal in the first

place.

(b) One is correlating an entity in the natural domain (excess

of dopamine) with a phenomenon in experimental domain which

one cannot correlate scientifically.

(c) The excess of dopamine can be subsequent to the experience.

Let us further clarify the difference between a physical ill

ness and a mental illness by taking the example of hypertension

and ‘schizophrenia’.

When as a doctor I find that the blood pressure of the per

son sitting next to me is more than 120 over 80 millimeters of

mercury, I tell him that he is suffering from hypertension.

Whatever my values, my beliefs they do not influence what I

see or observe, hypertension remaining a similar entity all over

the world.

On the other hand when a psychiatrist makes a diagnosis

of ‘schizophrenia’ he is judging the behaviour or experience of

the person sitting next to him according.to certain prevalent

(cultural) beliefs about human nature and what he sees is in

Mental Illness Not a Disease of the Body (Brain) fluenced by what he believes.

The findings of United States-United Kingdom Joint

One is often told during training that ‘schizophrenia’ is a Schizophrenia project reveal that American'-.psychiatrists tend

disease of-body (brain) like diabetes, hypertension (high blood to diagnose ‘schizophrenia’ much more frequently than their

pressure). One is also told that we are ignorant about the cause British counterparts. For a similar case an American psychiatrist

of ‘schizophrenia.’ but is it also not true of a bodily disease like will diagnose the person as ‘schizophrenic’ while the Britisher

cancer? ‘Schizophrenia’ is presented as a disease of body (brain) would not (ibid).

with a fixed cause which is being found out. One is reassured

that with the advance in medical technology, psychiatry will be

Objectivity of Diagnosis in Psychiatry

able to solve the riddle of ‘schizophrenia’.

The present day trend in psychiatry is towards explaining

“The diagnosis of schizophrenia should rest on whether a

mental illnesses as disorders of brain chemistry. It is speculated normal person understands the person concerned’s behaviour’—

that tomorrow we will possess such powerful drugs to cure Manfred Bleuler, a leading psychiatrist (Laing, 1982).

So how are psychiatrists different from lay people? A lay

mental illnesses that psychiatry will not exist as a separate

discipline but will be incorporated in clinical medicine and even person also understands that a person is behaving in an un

orthodox way, the psychiatrists call it ‘schizophrenia’. But what

general practitioners will be able to tackle these problems.

But let us look for evidence. Seymour S. Kety has done the have they gained in the process? Has calling the person

most extensive work on ‘Bio-chemistry of Schizophrenia’. He ‘schizophrenic’ rendered his situation, his response, more intelligi

says that his work is inconclusive about ‘schizophrenia’ being ble? No. One feels that the exercise of diagnosis is for screening

normal, good, conforming behaviour or experience from an ab

a bodily illness (Avieti).

One does not deny that physical illnesses and drug-induced normal, bad, nonconforming one; rather than to really under

states produce a picture resembling mental illness. But Seiger, stand the genesis of that behaviour or experience. This distinc

Osmond and Mann (1969) disagree about closeness of drug in tion is made by the psychiatrist on the basis of certain prevalent

duced states with real illness. Dr. Joseph Berke argues that in beliefs about human nature and hence in the psychiatric inter

‘schizophrenia’ hallucinations are mainly auditory. While under view a fact never remains a fact, it already becomes an inter

the influence of psychedelic drugs people rarely have hallucina pretation, a value judgement (Goldmann).

tions of any kind. Most of the experiences of false perceptions

(illusions) are visual in nature (Berke).

A-priori Assumptions About Human Nature in

One of the main theories about ‘schizophrenia’ is the

Psychiatry

dopamine theory. It states that the specific behavioural symp

toms are produced by excess of dopamine in the brain (Kaplan

These assumptions are based on an image of the human

and Saddock, 1980). If one finds that an abnormal behaviour being as a sociable, non-violent, hardworking, rationally profit

(inability to work consistently, inability to relate to people, etc.) making organism. These assumptions are revealed when one sits

or an abnormal experience (inability to experience pleasure, feel in the psychiatry out-patient department and makes a list of most

March 1986

157

frequently asked questions. These questions are:

(a) whether the person works regularly? (b) whether he/she mixes

with others? (c) if in business, is there adequate profit making?

(d) whether he/she is violent towards self or others? (Thines)

This human nature is supposed to be all pervasive and

universal, according to the psychiatrist. But let us look around,

let us go into the past to find out whether this is true.

Can one say that human nature is essentially peace loving,

non-violent when one looks back at Nazi concentration camps,

the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Where is the sociable

human nature when two communities exist side by side in the

world with evergrowing paranoia about each other?

Can one find a hardworking human being amongst those

few who rule the world today and enjoy at the cost of toiling

masses? Isn’t the wealth of many European countries smeared

with sweat and blood of the colonised people?

Man is yet to be born. On the totality of images that we

create by our praxis in the world depends the future image of

man. As of today, this is a period of inhuman exploitation of

men and women and a narrative of violence to maintain and

perpetuate that oppression. It is surprising then that those who

are most frequently diagnosed as mentally ill belong to the

category of defenceless (poor, children, women, aged) or those

whom the middle-class, superior caste/race psychiatrist cannot

understand—the ethnic minorities, people who live on fringes

of cities. Half a million children in the United States receive treat

ment with powerful psychoactive drugs for being ‘hyperkinetic’

(Ingleby, 1980). The incidence of ‘schizophrenia’ is more in the

lower socio-economic strata (Lidz).

Practice of Psychiatry

“Cure is accomplished when the former person becomes

an obedient robot moving around either in the chronic

backwards of mental institution or without any human sense

in the outside society ...” (Cooper, 1974).

Antonin Artaud, a great poet, wrote with anguish after be

ing given electroshocks in. a hospital at Rodez “I died at Rodez

under electroshocks. I say dead, legally and medically dead”

(Greene).

Ernst Hemingway describing his experience of shocks to

his friend said, “it was a brilliant cure, but we lost the patient.

It killed both my soul as well as my mind” He committed suicide

a few months later (Madness Network News, Fall 1984). A

violonist who was given shocks for depression in a Glasgow

hospital, could not later on give her performance as she lost

her violin repertoire (Laing, 1976). Most of the groups working

for a ban on electroshocks in different countries of the world

claim that not only do shocks cause memory loss, disorientation

wild excitement or terror, but shocks can also kill. Shock is not

only a procedure wherein electric current is passed through the

brain of a person but also the dehumanising ritual of being for

cibly held by people, being forced to lie down, etc. which a per-.

son has to go through. Why are people not told about the after

effects of shocks? Why are they not told about the procedure?

I am sure if the procedure is described to the person, he will

never like to undergo such a dehumanizing experience. Shocks

are either mystified—-‘Its only an injection’, ‘You will be cured,

or they are offered as an alternative to long term hospitalisa

tion. In a similar situation a group of prisoners agreed to par

ticipate in an experiment which they knew would damage their

health, so as to get their prison stay reduced.

Dr Caligari’s Psychiatric Drugs, a book published from

Berkeley, informs us that psychiatric pills neither tranquillise nor

elevate our mood, they actually deaden our feelings and our

bodies. Drugs like thovagine, steliazine, nlehavil, haldot (all anti-

Towards a Human Psychiatry

Present day psychiatry considers the person as a passive

object, who reacts in a determinate way to his situation. It shows

complete disregard for human subjectivity. Between our interiorisation of exteriority (family, class experience) and our reexteriorisation of this interiority, i.e. in the passage from

exteriority to exteriority (objective to objective) there is a moment

of human subjectivity. We do not necessarily reproduce in the

same exact fashion the exteriority which we interiorise. In other

words we can always make something of what is made of us.

This is the realm of human freedom. This is ignored in the con

stitution of the person as passive object.

Economic and Political Weekly

A journal of current affairs, economics and other social sciences

Every week it brings you incisive and independent comments and reports on current problems plus a number of well-researched

scholarly articles on all aspects of social science including health and medicine, environment, science and technology etc Some

recent articles:

Mortality Toll of Cities-Emerging Pattern of Disease in Bombay: Radhika Ramsubban and Nigel Crook

Famine, Epidemics and Mortality in India-A Reappraisal of the Demographic Crisis of 1876-78: Ronald Lardinois

Malnutrition of Rural Children and Sex Bias: Amartya Sen and Sunil Sengupta

Family Planning and the Emergency-An Unanticipated Consequence: Alaka M Basu

Ecological Crisis and Ecological MpvementS: A Bourgeois Deviation?: Ramachandra Guha

Environmental Conflict and Public Interest Science.- Vandana Shiv? and J Bandhyopadhyay

Geography of Secular Change in Sex Ratio in 1981: Ilina Sen

Occupational Health Hazards at Indian Rare Earths Plant: T V Padmanabhan

Inland Subscription Rates

Institutions/Companies One year Rs 250, Two years Rs 475, Three years Rs 700

Individuals Only One year Rs 200, Two years Rs 375, Three years Rs 550

Concessional Rates (One year): Students Rs 100; Teachers and Researchers Rs 150

(Please enclose certificate from relevant academic institution)

[All remittances to Economic and Political Weekly. Payment by bank draft or money order preferred PIpacp aHh

cheques for collection charges]

P^crrea. riease add Rs 14 to outstation

A cyclostyled list of selected articles in EPW on health and related subjects is available on request

158

Socialist Health Review

For lay people psychiatrists wearing white coats, dispens

psychotics), tofanil, elavil (antidepressants) have a damaging

effect on the brain.

i ing medicines appear scientific, objective. But if there is no con

Thndive dyskinesia is a syndrome charecterised by involun-' sensus on fundamental issues in psychiatry, if there is more em

tary movements of tongue, face, neck, developing after long term phasis on labelling than understanding, and if the therapy is ar

antipsychotic medication. It is difficult to cure. The addiction bitrary and damaging, any amount of scientificity that psychiatry

potential of diazepam (valium, calmpose) is also mentioned in will try to bring in from outside, from its white coats, its pills,

the book. A separate chapter instructs the readers on how to its sophisticated research on the body of ‘schizophrenics’, its

safely and gradually withdraw from psychiatric pills. But people alliance with medicine, will be futile.

coming to psychiatry’ departments are hardly told about the after

On the other hand the present day psychiatry believes that

effects of pills. Why?

the psychiatrist is a passive observer. He does not influence the

situation, he does not see what he wants to see. By constituting

the person as an object, an ensemble of physico-chemical en

Critique of Medicalised Psychiatry

tities, which is only worth effort of labelling and classifying,

In his postscript to ‘Discussion of Lay Analysis’ Sigmund the psychiatrist remains totally external to the lived experience

Freud emphasised that psychoanalysis is not a branch of of mental illness.

medicine but comes under the head of psychology and the train

Mental illness is nothing but a response of the person to

ing for psychoanalysis differs from that imparted to physicians. his situation. We will be able to comprehend it only when we

More important than whether the trainee is a medical graduate grasp the situation to which it is the response. It is also essen

or not, is the specialised training for psychoanalysis. He also tial to understand the lived experience of mental illness with the

stressed that the trainee will have not only to study psychology help of mediations like family and class.

but also sociology, history of civilisation, Darwin’s theory of

Instead of being a discipline which of necessity must give

evolution, etc. But has psychiatry paid any heed to Freud’s, respect to the dignity and freedom of the individual, present day

advice? No. Even to pay heed to it, it will have to read, remember psychiatry is repressive. It should be our common endeavour

his work and not repress it.

to reinstate this respect for human dignity and freedom in

psychiatry so that it will really be a human psychiatry.

Today the alliance between psychiatry and medicine is com

References

plete with incorporation of psychiatry into general hospitals.

Those who train in psychiatry are medical graduates who take Avieti, Silvano, Understanding and Helping the Schizophrenic in

American Handbook of Psychiatry.

up psychiatry as a postgraduate discipline, while in his days Freud

Berke, Joseph, Interview in R D Laing and Anti-Psychiatry by-Robert

defended ‘lay analysis’ (McGuire).

Bayers et al., Philadelphia Foundation.

Cooper, David, The Grammar of Living, 1974.

The present day psychiatry is medicalised psychiatry with Cottle, Thomas and Philip Whitten, Psychotherapy—Current Perspec

its belief that mental illnesses are due to disorders of brain

tives, 1980.

chemistry, with its emphasis bn diagnosis and classification Goldmann, Lucien, Human Science and Philosophy.

(labelling) and its promise of instant cures with pills and shocks. Greene, Naomi, Antonin Artaud—Poet Without Words.

Ingleby, David (ed), Critical Psychiatry—The Politics of Mental Health,

By proclaiming that mental illness is a physical illness, it

1980.

situates the problem inter-individually, allowing family and socie Kaplan, H. and B Saddock, Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry,

1980.

ty to wash its hands of the person and hence it remains essen

tially status-quoist. By giving more emphasis on diagnosis and Laing, R. D. Facts of'Life, 1976.

classification than understanding, intelligibility, which requires Laing, R. D. Voices of Experience, 1982.

empathy, it is basically screening people who cannot fulfil the Lidz, Theodor, Interview in R D Laing and Anti-Psychiatry, op cit.

expectations the society has of them, on behalf of the ruling McGuire, Williams (ed), Freud and Jung Letters.

Seiger, M. H. Osmond and H. Mann, Laing’s Model of Madness in

class.

British Journal of Psychiatry, 115:525, 1969.

By its reliance on pills and shocks it ends up by medicalising Thines G., Phenomenology and Science of Behaviour.

human problems and hence psychiatric therapy has on the con

Dilip Joshi

trary damaging effects.

through SHR

Socialist Health Review

will now be

RADICAL JOURNAL OF HEALTH

We regret to announce that despite all our efforts we have not been able to register the publication under the name

Socialist Health Review. We have been allowed the use of RADICAL JOURNAL OF HEALTH, which incidentally was our

last choice! The issue of June 1986, Vol III number 1 of SHR will appear as RADICAL JOURNAL OF HEALTH. Please note

that the objectives and purpose of the journal and therefore the choice of content, will remain the same.

March 1986

159

The Helping Profession: Is It Really Helpful?

annie george

The role of medical and psychiatric social work in dealing with the mentally ill has

due to the community mental health movement. What is the role of the social worker. o\

for handling their task? In this article the author, herself a trained social worker, addresses the

a critique of psychiatric social work programmes as they exist today in -the context of e

IT is generally accepted today that the causative factors for mental

ill health are multifarious and interlinked and so their handling

on many fronts—curative, preventive and promotive—is done

by a multidisciplinary team. Traditionally, and till today, mental

ill health has been seen as an illness in a clinical sense, and so

the doctor is the person with whom the mentally ill person comes

in contact for treatment. But increasingly, and cardinally,

through the influence of developments in this field in the west,

other professions have been roped into the field of mental health.

Psychiatric social work is one such profession.

Who is helped through the intervention of social work, the

“helping” profession, in the field of mental health? What were

the roles assigned to it historically, and how have they changed

to fit the mental health situation in India today?

Evolution and Contributions of

Psychiatric Social Work

nuestions and presents

<!

situation

social diagnosis and to suggest means of treatment together with

physical and other psychological methods which would help

them revive their strengths and become-active citizens (emphasis

mine) (Marulasiddaiah and Sharriff, 1981). In other words the

social worker used all possible means and resources to help the

person adjust to the very conditions w'hich caused the problem.

Through experience, social workers realised that other social

groups to which the mentally ill person belonged, like the family

and the work group, could also be used in the process of getting

the person readjusted. Thus emerged treatment methods like

family centered therapy and milieu therapy.

By the seventies there was a growing disillusionment with

the p.erson-centered, curative approach. Individual care in help

ing the mentally ill person to adjust was time consuming, ex

pensive, and its results were seen only after a long period of in

tervention. Community based mental health services were seen

as an alternative. In this approach like the earlier individual

centered one, the basic understanding of mental health had not

changed; the contributions of social conditions—growing aliena

tion, pressures of urban competitive life, erosion of traditional

community support systems—to mental ill health were not

acknowledged. Mentally ill persons, those who deviated from the

norms determined by society, still had to be adjusted to fit into

that society. The difference was that the adjustment would start

with the community, would focus on preventive measures and

would reach out to more people by training people from the com

munity as frontline mental health- workers. For the social worker

the essential difference was that instead of treating the individual

as an unit of work, the community became the work unit. Her

major role would now be to provide psycho-social data about

the community, and to plan programmes to prevent mental

illness, programmes which includes recreation facilities for

adolescents, family life education, and so on. Since the com

munity health movement has not gained much ground in India,

there are not many community based mental health program

mes. Activities like organised recreation activities for children,

fun fairs and sports days which are organised by social work

agencies for disadvantaged groups usually go under the garb

o community mental health programmes. These programmes

nrnhumpo?aj1 u di-V«n the attention of the people from their

ms o aily living but they do nothing to alleviate them.

The concept of what constitutes mental health and ill health

has always varied, and with it has changed the role of the social

worker. The western practice upto late 19th century was to

segregate the mentally ill persons in asylums, away from the

mairtstream of society. Since such persons w'ere considered in

curable, no psychiatric attention was given to them; social work

intervention was also non-existent. By the end of the 19th century

the understanding of mental illness in western society had

changed considerably: mentally ill persons were now considered

“sick” and various physical and psychological therapies were

tried on them. The underlying assumption of such an approach

was that people became mentally ill because of their inability

to adjust to the pace and demand of urban industrialised life.

Various theories citing psychological factors intrinsic in the

“sick” individuals were put forward as the cause of their

maladjustment; but whatever the understanding and the line of

treatment, the end goal of the process was definite—the men

tally ill person had to be treated such that he/she would be able

to adjust back to society.

In the practical application of this conceptual framework

there was tremendous scope for social work. Medipal and

psychiatric social work emerged in the USA and Great Britain

in late 19th century because doctors there felt the need for a

person who would supplement the service of medical care pro

chaneed^hm/hh

°f the psych’atric social worker has

vided through hospitals. Social workers were .used by them to

get a more complete picture of the patient’s background by pro tai ill health hJ vari?^s approaches to the treatment of menviding psycho-social data about the patient. In India psychiatric to identify menra?inlI’!|)UtlOn 10 society has remained the same:

social work started because Indian doctors had gone abroad and

qUef’ '° resocialise the Per'

had seen psychiatric social workers and wanted them to act as son to the requhements of J

“acolyte” to the high priest, the doctor. (Marulasiddaiah and is not possible, to segregate the n *

‘f SUCh resocialisation

Sharriff, 1981).

normal people are not^isturhed"0"/™"1 SOC*ety S0 that other

fu“tionin?- In

Right through the sixties, in the west, the treatment of the fact, the social control aspect^nh^ioh

mentally ill was predominantly individualistic, institution-based the background and wh„.

th Job 8enerally remain tn

and curative; this is the approach which is prevalent in India and the public ’at large to bThold^ ‘he mentally iU perSOn

today. The role of the social worker was to understand the (psychiatric social worker)

-S a gentle> caring woman

behaviour of people when they are (mentally) ill, the poten service and to look after °.se entlre function is to be at their

tialities within individuals and their families, the resources in psychiatric social worker? □

pro^ems- Most medical and

the community, the environmental effects associated with the social work like commnnitv Je ^Omen; other specialisations of

disease, creation of insight into their problems, to bring out a • sidered the male domain

Ol?ment or criminology are con-

"..,2,h“‘

domain. Medical and psychiatric social work

160

Socialist Health Review

is probably seen by most people as an extension of the tradi

tional role assigned to women as the caretakers of the sick and

helpless members of the family. Moreover, traditionally, the

woman bears the responsibility of socialising the child and

psychiatric social workers, as an extension of this traditional role,

resocialise the mentally ill person who has lost the social skills

which are necessary to survive in an industrial, competitive

world. Thus through their legitimately assigned task of labell

ing (diagnosis), treating and/or confining persons with deviant

behaviour, the psychiatric social workers perform a subtle and

sophisticated form of social control. Her efforts to identify and

change the stress inducing elements inherent in the way society

has been organised are negligible. The present day social work

education programmes are partly responsible for this state of

affairs.

Psychiatric Social Work Training Programmes

Entrants to the field of psychiatric social work are trained

for the profession through a two year course, generally conducted

at the post-graduate level. Some schools of social work in India

offer specialised training in medical/psychiatric social work. At

such schools, in the first year students are taught basic courses

in the methods of social work, human behaviour, man and

society, and some electives. It is in the second year generally that

courses related to the specialisation are taught. These usually

include courses on psychiatric information for social workers,

courses on methods of social work used by psychiatric social

workers—mainly casework, or working with an individual and

his family—and concepts from different schools of thought, like

Freud, Rank and Parsons which have practical use in casework.

Much of the theoretical base and action of medical and

psychiatric social work is derived from Talcott Parsons’ model

of the sick role, in which, sociologically, illness was seen as a

form of social deviance where an individual adopts a specific

role. The sick role was characterised by the patient’s temporary

exemption from social responsibilities, and freedom from blame

for being sick. However, since the role was considered undesirable

and socially not approved, the sick person was expected to seek

professional help to get well, and to comply with the treatment

prescribed by the medical personnel. Though Parsons’ model

of the sick role provides the basis of work for the psychiatric

social worker, in terms of treating mentally ill persons and get

ting them back to perform their socially defined roles, it also

is a legitimisation of the power of mental health personnel over

mentally ill persons who have to comply with the treatment of

the professionals in order to have the label of social deviant

removed. In the theoretical part of the training most emphasis

is given to casework than on any other method of social work.

In casework the focus of content is on various theories which

explain human behaviour and which therefore help the

psychiatric social worker understand, arrive at a social diagnosis

and plan out the treatment of mentally ill clients. Thus these

courses lend to stress psychiatric analysis of individual problems

rather than skills in dealing with the core of the problem situa

tion itself. They are also institution centres and stress the

remedial aspects in mental health (Miranda, 1985). At the level

of theoretical training mental health is not seen in its wider sense

with contributions from other courses on social work methods.

Specialisation courses are so compartmentalised that students

of psychiatric social work" generally cannot take courses offered

by other specialisations like community development or family

welfare, even though the information content of these courses

may be very relevant for the psychiatric social work student to

develop a holistic understanding of her field of training.

Field work is the practical component, in the training to

become a psychiatric social worker. Field work experience, in

March 1986

which the student is attached to various social work agencies

for two or three days per week for the entire period of the train

ing, is largely limited to institutional urban settings like child

guidance clinics, mental health day care centres, and psychiatric

departments in wards of urban hospitals. Here the student gains

maximum experience in-casework or in working with individuals

who are diagnosed as mentally sick. Any experience in com

munity mental health is usually unplanned and incidental. It

is expected that when students become practitioners they will

be able to transfer their skills to other settings. This never really

happens. In field work students spend more time learning about

the “what” and the “how” in field work tasks than in engaging

in the “why” or analytical and conceptual learning (Miranda,

1985). Hence, students are more bothered about what are the

symptoms and how to counsel a mentally ill person than in

understanding why he has been labelled as sick, and what were

the forces in his immediate and extended environment which

caused him to behave in a different way than is normally

expected.

Field work is critical learning experience for the*social work

student because this is the period when her concepts about the

practice of the profession are being formed, based on her prac

tical experiences; she is also trying to work out her professional

role as a social worker. Relating theory to practice becomes the

major learning activity in field work. When theory and prac

tice focus exclusively on the mentally-ill person and on his treat

ment so as to get him resocialised and readjusted to the demands

of society, it is inevitable that by the end of the training period

the student social worker has equated working on treatment and

rehabilitation of mentally ill persons as the main role assigned

to her. She in turn becomes a practitioner and carries on this

tradition.

Relevance of Training

Observing the practice of psychiatric social work today, it

would appear that the effectiveness of the training is limited to

the time tested casework method. However, as Desai (1981) says,

the effectiveness of a profession depends on the quality of

preparation of the practitioners. The objectives of the curriculum

in social work training are to prepare the type and quality of

manpower capable of performing tasks and functions which

ultimately achieve the goal the profession has set for itself in

the context of the society in which it seeks to serve. Desai analyses

and lists the social realities of India as poverty, population and

its interface with problems of housing, water supply, sanitation,

accessibility to services; unemployment, disability resulting from

social and economic inequity, and the exploitation of the

vulnerable and weaker sections of society. Constant coping with

these problems could lead to a breakdown in an individual’s

mental health functioning. Therefore the tasks of the

(psychiatric) social worker would be to identify policies and

socio-economic structures which are exploitative of the majority

and which are not designed to achieve social goals for all. A

second major role would be to develop and/or modify services

and/or institutional structures for educating people to recognise

their inherent capacity for action. By and large psychiatric social

workers do not perform these roles because neither at the train

ing level nor at the practice level has it been consciously realis

ed and acknowledged that it is these societal problems of daily

living which are contributing to the mental ill health situation

in India.

The present day training programmes do not address these

tasks. The training curricula are basically borrowed from the

west, mainly the USA. They aim at helping people adjust to an

urban, industrial and metropolis dominated social milieu—

because Indian social scientists accept the western model of

161

development for the elimination of poverty. Social work was

established to help the deviants of the system to adjust to it and

to provide remedial services to those who are victims of new

social systems (Desai, 1981).

The training and practical efforts of psychiatric social work

is relevant; to whom it is so is the question. If serving the needs

of the majority of the population in order to bring them into

the mainstream of development is the goal of social work, then

the training for psychiatric social work, particularly the

knowledge about what constitutes mental health and mental ill

health, the skills in treating mentally ill persons based on the

understanding of what constitutes mental health, and the values

embedded in such an interpretation are not relevant to the

majority of the people, not even particularly to the mentally ill.

Social workers have not been able, in any significant way, to work

out strategies to deal with the daily problems of living of the

majority—problems which take thejr toll in terms of familial

tensions, and menial ill health. What the professions involved

in mental health have successfully done is to medicalise social

problems, to make it appear that problems stemming from social

causes are actually due to individual deviance, solvable or at

least controllable by the individual’s doctor (and others involved

in the therapeutic process) (Ehreinreich, 1978). Psychiatric social

work, in this sense, is very relevant to the powers that be, th ough

the semblance of a profession based on scientific knowledge,

which helps deviant people adjust, it ensures that the way society

is presently organised is maintained.

References

Desai, A. S., “Social Work Education in India: Retrospect and Prospect”

in Nair T. K. (ed.) Social Work Education and Social Work Practice

in India, Association of Schools of Social Work in India, Madras, 1981.

Ehrenreich, John, “Introduction”, in Ehrenreich, John (ed.) Cultural

Crisis of Modern Medicine, Montlhy Review Press, New York, 1978.

Marulasiddaiah, H. M. and Shariff I., “Medical and Psychiatric Social

Work Education in India” in Nair T. K. (ed.), op cit.

Miranda, M M , “A New Perspective in Medical Social Work”, Indian

Journal of Social Work, Vol. XLV, No. 4, Bombay, 1985.

Annie George

5, Varsha Sangam

Chakala, Andheri (E)

Bombay 400 099

UN List of Banned Products

LAST June, the UN decided to delete all trade information from

future editions of the “UN Consolidated List of Banned and

Severely Restricted Products”, an international directory of trade

and regulatory data on over 500 products contributed by 60

countries. Just this week, the UN announced its intention to

reverse that decision. The reversal came after months of lengthy

debates on the issue within the UN in a highly politicised

atmosphere. Ultimately, reason pre-vailed over pure politics and

the public interest perspective—including trade data—emerged

as the only rational solution to the debate. The 1986 edition will

include trade data and the unique trade name index for pesticide

and pharmaceutical products.

Hundreds of very thoughtful letters from the NGO community

were in a large part responsible for allowing the debate to occur

at all and for eventually helping to turn the decision in the direc

tion of including trade data. While opposition to the mere

existence of the ‘List’ has clearly diminished over the past several

years, it has not disappeared. At the present, claims are being

made that the ‘List’ is not really useful to governments, but is

only a duplication of other efforts at information sharing laready

in place in other UN agencies.

The United Nations is currently preparing its report on the

Consolidated List Project for the Economic and Social Council

(ECOSOC) meetings to be held in July. The office preparing

the report would like to include examples of instances where the

List has been useful to governments. The UN has recently written

letters to countries in order to collect that information from

them.

NGOs could be helpful in supporting the UN effort to collect

data on the List’s usefulness in a number of ways:

1 Encourage your government to reply to the UN’s request

for information. The UN has sent requests for information on

the ‘Lists’ usefulness to World Health Organisation correspon

dents, United Nations Environment Programme correspondents,

and the United Nations Development Programme’s Resident

Representative in all countries, and have asked those Reps to

contact government officials for that type of informaton.

2 Contribute your own examples of how your organisation

has used the List to bring about positive changes in laws or prac

tices in your country. Brazilian groups, for instance, have used

the UN Consolidated List in their efforts to persuade their

government to severely restrict certain very dangerous pesticide

products. A British organisation has reported that it has found

the List very useful in its work with the United Kingdom’s Food

and Environmental Protection bill.

If you do send data on positive contributions of the ‘List’,

please try to make your descriptions as specific and as well

documented as possible. For example, it would be helpful to

include the date of any legal or administrative action taken and

a copy of the actual taxt of the law with your description of

the, action. If it is impossible for you to collect background

documents, but you know of an action that has been taken as

a result of the UN ‘List’, please report it anyway. Background

can be collected later, if needed. All information must be received

by May 15, 1986, it is to be included in the UN’s format report

for the Economic and Social Council. The UN address is:

Assistant Secretary General, United Nations, DIESA-PPCO,

18th floor, New York, New York 10017; USA. Also, please send

a copy of all correspondence to us for our information.

Eileen-Nic

n

Program Coordinator

coordinating Committee on Toxics and Drugs

C/o NRDC, 122 East 42 St.

New York 10168

USA

162

Socialist Health Review

The Ambivalence of Psychoanalysis

david ingleby

Almost since the beginning of the century, psychoanalysis has sat like an undigested meal in the collective stomach.

Unable finally either to assimilate or eliminate it writers have endlessly churned over its merits and demerits. The list

of books on psychoanalysis which are offered to the public year after year never ceases to amaze. For, as well as being

one of the most daring and radical ideas ever put forward, psychoanalysis is also part of a deadening and conformist

apparatus. This paradox, which underlies the permanently troubled relationship between psychoanalysis and the Left

is the subject of the article, condensed from “Psychoanalysis Groups Politics Culture” edited by the Radical Science

Collective Free Association, 1984.

The Essential Ambivalence

WITHOUT doubt it is the ambiguous political message of

psychoanalysis which has kept the discussion open so long. If

it were possible to classify it once and for all as ‘progressive’

or ‘reactionary’, the issue would long since have been dropped.

Writing a political character reference for psychoanalysis is no

easy matter. So deep are the contradictions involved that one

comes to mistrust anybody who has arrived at a simple conclu

sion ‘for' or ‘against’.

The political arguments against are well known. As a

therapy, psychoanalysis can be authoritarian to the point of

‘brainwashing’ its patients; and concerned both with ‘inner’ fac

tors to the exclusion of ‘outer’ ones, and with adjusting the in

dividual to the status quo, rather than society to its inhabitants.

As a theory, it is reductionistic, ignoring social factors and

obscuring political tensions, and embodies many conservative

and socially pessimistic assumptions. When this theory becomes

disseminated as a popular world-view, we are in the grip of an

ideology which stifles political action even before it can be

expressed.

Yet as often as it is vilified, psychoanalysis is redeemed by

leftist (and feminist) enthusiasts who come to its rescue. In the

Frankfurt School tradition, it offers, first, a critique of the col

lective psychoanalysis which makes capitalism tick (Reich,

Adorno, Marcuse); and, second, a mode of analysis—Critical self

reflection—which provides a paradigm for ‘emancipatory’

thought (Habermas). In French structuralism (Lacan, Althusser),

it decentres human subjectivity away from the Cartesian ego,

in a paradigm shift as radical as that achieved by Copernicus

four centuries before. For those seeking to give content to the

slogan, ‘the personal is political’, it reaches beneath the banality

of everyday consciousness to grasp the processes which underly

the power-structure of relationships. Lacking any serious com

petitors on this terrain, psychoanalysis is likely to survive any

denunciation its critics heap upon it.

We are not likely to find which side psychoanalysis is ‘really’

on by scrutiny of Freud’s own political views. Aside from the

fact that quotations can be dredged from his writings which show

him in any light one pleases, the assumption on which such a

search is based is a faulty one; there may be little correspondence

between an individual’s conscious attitudes to society and the

message which speaks through their writings and actions.

The truth is, as I shall attempt to show in this essay, that

the political character of psychoanalysis is inherently ambivalent;

this is due, not only to the fact that different readings of it can

be produced which argue in different directions, but also to cer

tain contradictions built into its practice and theory.

Psychoanalysis As Therapy