Socialist Health Review 1985 Vol. 2, No. 2, Sep. People in Health Care.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

47/1. (First Ficor) St. Marks Road,

Bangalore - 550 001.

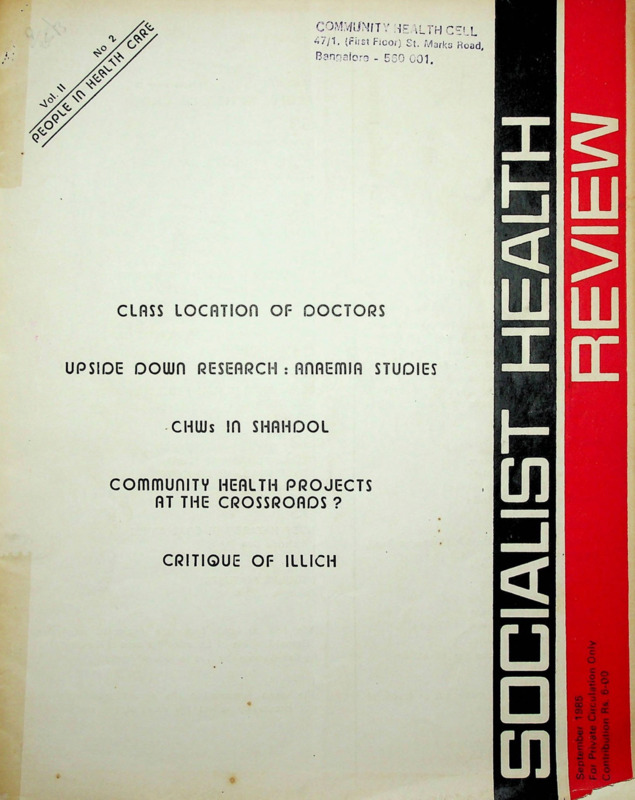

CLASS LOCATION OF DOCTORS

UPSIDE DOWA RESEARCH : AAAEffllA STUDIES

CHWs IO SHAHDOL

communiTv health projects

AT THE CROSSROADS ?

CRITIQUE OF ILLICH

o

Yol II

Number 2

PEOPLE IN HEALTH CARE

53

Editorial Perspective

PEOPLE IN HEALTH CARE

C. Sathyamala

57

DOCTORS IN HEALTH CARE

Sujit K. Das

Working Editors :

67

Amar Jesani, Manisha Gupte,

Padma Prakash, Ravi Duggal

UPSIDEDOWN MEDICAL RESEARCH

Rajkumari Narang

Editorial Collective :

74

Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (A P),

Imrana

Quadeer, Sathyamala C (Delhi),

Dhruv Mankad (Karnataka), Binayak Sen,

Mira

Sadgopal

(M P),

Anant

Phadke,

Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar, Jean D'Cunha,

Srilatha Batliwala (Maharashtra) Amar Singh

Azad (Punjab), Smarajit Jana and Sujit Das

(West Bengal)

Socialist Health Review,

19 June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay - 400 050 India

Printed at:

Omega Printers, 316, Dr. S.P. Mukherjee Road,

Belgaum 590001 Karnataka

Rates

:

Rs. 20/- for individuals

Rs 30/- for institutions

US §20 for the US, Europe and Japan

US$15 for other countries

We have special

countries.

84

COMMUNITY HEALTH PROJECTS: AT THE

CROSSROADS ?

Sumathi Nair

92

Editorial Correspondence :

Annual Contribution

SOCIAL DYNAMICS OF HEALTH CARE

Imrana Quadeer

rates for developing

(Contributions to be made out in favour of

Socialist Health Review.)

REVOLUTIONARY IN FORM,

REACTIONARY IN CONTENT

B. Ekbal

95

DUST HAZARDS IN COAL MINES

Amalendu Das

REGULAR FEATURES

Dialogue : 89

We had to hold back the excerpted article

"Sexual Division of Labour : The case of Nursing"

by Eva Gamarnikov due to lack of space.

The views expressed in the signed articles do

not necessarily reflect the views of the editors.

Editorial Perspective

PEOPLE IN HEALTH CARE

other profession enjoys the amount of adu

lation or gets its share of brick bats as does

the medical profession. The problems of ill-health

being what they are in our country, every discussion

and debate on such issues revolves around the

question of availability of doctors This factor has

assumed such a major importance that the doctorpopulaiion ratio has come to be accepted as a

standard measurement

of health services and

indirectly of the health of a population. In this

process ihe important contribution made by the

other categories of health workers remains invisible

only to come up when they strike work.

The central role doctors play in diagnosing and

treating diseases is not merely confined to the

provision of such services but extends to the entire

field of health care including the right to define

what constitutes disease and the right to treat it.

The medical profession argues that if high quality

services are to be made available and if 'purity' of

medical practice is to be maintained it is essential

that the profession retains complete control through

registration and legislation. Further, the medical

profession argues that diagnosing and prescribing

are superior to all other skills and only those who

possess such skills have the necessary authority to

direct the course of health itself. That all such

arguments merely form a facade for maintaining

monopoly over a valuable commodity can be seen

by looking at the way medical practice evolved into

its present professional status.

The Beginnings of Medicine as a Profession

The emergence of the medical profession can

be traced to 14th-15th century Europe which witn

essed a class alliance between the upper middle

class male 'regular' doctors and the feudal church

leading to the ruthless extermination of other

healers, mostly women, through well organised

witch-hunts Similarly, two centuries later in America

the 'regulars'tried to gain monopoly over medical

practice by attempting to pass state legislation in

collusion with the emerging industrial and comm

ercial bourgeoisie. Initially such attempts met with

mass protests which culminated into a popular

health movement. Unfortunately, the effort against

legislation could not be sustained and the move

ment degenerated into a number of medical sects.

September 1985

The 'regulars' attempt at cornering the market

for their expertise was based on two factors.

Firstly, the 'regulars' need to eliminate competition

now arose as, for the first time, the practice of

medicine was being viewed a full time economic

activity. Secondly, if this activity was to bring in a

substantial income, it was necessary to improve

the image of the activity by giving it a professional

status. As a mark of distinction the regulars adopted

the Hippocratic oath and code of ethics as their

standard. It is important to note that all this took

place before medicine had attained any scientific

aura or had developed any rational medical inter

ventions. In fact, the regulars of that time

practised what was known as heroic therapy which

included blood-letting,

purging and applying

leeches among other such horriffic remedies.

With the support of the industrial and commer

cial bourgeoisie, it was just a matter of time before

specific and effective interventions in the disease

process developed which further consolidated the

power the medical profession had gained through

legislation and the physical extermination, of other

healers. It was this monopoly that shaped the form

and content of medical care to its present form.

The predominant hospital structure and the emer

gence of other categories of workers such as the

nurses, laboratory, x-ray technicians, pharmacists

and others has evolved and revolved around the

functions that a doctor performed.

It was also not a mere accident that nursing

emerged as a suitable profession for women or

that it was subordinated to doctoring. By the time

medical practice had become established as the

domain of male regular doctors, women had been

eliminated from health care for all practical purposes.

The authority that doctors had in defining norma

lity allowed them the power to advance pseudo

scientific theories and sexist arguments regarding

the intellectual capabilities of women to prevent

them from entering medical colleges. Women from

the upper classes were increasingly being told to

conserve their energies for the supreme function of

being a woman, that is procreation, and were

therefore forced to lead a sedentary life. For the

women from this class who did not or could not

marry, life had little option. Apart from teaching

there was hardly any respectable 'genteel', non

53

industrial occupation which would be socially acce

ptable and at the same time provide a certain

level of economic independence. The goal of Flor

ence Nightingale, the 19th century reformer was to

create a paid job in health care for women. To

make it acceptable to doctors Nightingale demo

nstrated in the battle field of the Crimean war that

nursing would remain subordinate to doctoring and

her attempt to make the occupation acceptable to

women was to draw analogies between nursing

and housework. The doctor nurse relationship was

projected as a husband-wife interaction and nursing

was stated to be 'natural' to women, as it coincided

with what was considered to be her natural biolgical

function. Since Nightingale’s effort was to create a

job for the women in health care she made it quite

clear that it would in no way question the suprema

cy of doctors or the subordinate position of nursing.

Feminist historians however question the acceptance

of nursing as a natural sexual division of labour. By

taking patriarchy as an analytical category they have

tried to argue that what is generally considered a

natural sexual division of labour is in reality a social

division of labour which designates men to be

superior to women in all social interactions, con

cerning men and women.

The heritage handed down to the nursing

occupation by Nightingale and other reformers has

left its indelible mark on the issues identified by the

nursing profession in the later years. Nurses have

taken up issues related to registration, professional

status and for a certain degree of organisational

autonomy. But at no time has the nursing pro

fession questioned its subordinate position. In fact

one of the barriers for expanding the nurses role

to a nurse-practitioner came from the nurses associ

ation in the US, who were reluctant to accept the

responsibility for diagnosing and treating.

In India one could say that the health care

system expanded only after independence. Although

on the whole its evolution was similar to the develop

ment that took place in the West, there were

certain dissimilarities. For instance, even as far

back as 1883 several universities in India began

to accept women as medical students. The Bhore

committee in its recommendations at 1946 stated that

at least 20-30 percent of seats in medical colleges

should be reserved for women students. The change

in attitude of the profession towards women stu

dents was perhaps related to the constraints placed

by the purdah system on women in general which

prevented the male medical profession's entry into

areas such as maternal and child health. The post

54

independent years have seen atlrrepts to provide

medical services through an alternative health care

structure by establishing primary health centres and

subcentres to cover rural populations. But through

out all these developments adequate care was taken

to ensure that the monopoly exercised by doctors

would be maintained and remain unquestioned

The Bhore

committee stated categorically

that only the physicians trained in allopathy,

should

be called doctors and the doctor was

to be the unquestioned leader of the medical

team whether it was in the operating room or in the

primary health centre. It emphasised the training

of one level of doctors and recommended the aboli

tion of the Licenciate course. Without analysing

the class background of the doctors or their class

interests the members of the committee hoped

that training sufficient number of doctors would

ensure that they would opt for the villages That

the committee was not sufficiently interested in

the other categories of health personnel can be

seen by the number of pages devoted in their

report on the training of doctors and all other

categories of workers. Later committees too have

emphasised the role of doctors at the cost of

neglecting all other health personnel. The need to

train a 'lower' category of practitioner is discussed

time and again but is always rejected on the plea

that it would lead to quackery. At the same time

when the suggestions that a 'lower' level of nurse

be trained was made by the nursing council it

was greeted as the most feasible solution given

the low resources available in the country. Similarly

when the Shrivastav committee made its recommen

dation in 1975 for training village level workers,

it also allayed the fears of the medical profession

by stating that since the role of these function

aries was educational, their curative skills would

be limited to just a few remedies for simple day

to day illnesses.

The end result of all such actions has been

to create a structure which is rigidly hierarchi

cal reflecting the class structure in the broader

society. Just the way the economic status or caste

of a person largely influences his/her future position

in any socio-economic activity, in medical practice

too these factors very often determined which level

of hierarchy s/he will

occupy in the health

structure. This streamlining into 'suitable rung in the

hierarchy is generally mediated through the person s

performance in and access to education. For ins

tance, the three categories of nursing personnel we

have in India that is the B.Sc. nurse, the Registere

Socialist Health Review

Nurse Registered Midwife (RNRM) and the Auxi

liary Nurse Midwife (ANM) required different levels

of educational qualifications to enter into their res

pective training schools. This determines the class

that will be predominant in each of these categories

which is further consolidated by the differential

salary structure and status afforded to these three

categories in the nursing profession.

Since medical care is a valuable commodity and

the right to provide it has been appropriated by

doctors, all other categories of health workers

and the functions they perform remain subordinate

to that of doctors. This monopoly is often carried

to ridiculous lengths, such as the prohibition on

nurses to start an intravenous drip or give an intra"

venous injection.

Reports discussing the problems of health

personnel have also mostly focused on the problems

faced by doctors. One hears repeatedly that

doctors have to face innumerable problems such as

lack of educational facilities for their children, lack

of 'entertainment' in the village and less opportuni

ties for professional growth; and that unless these

facilities are provided it would be unrealistic to

expect doctors to work in the villages. But these

'problems' really pale in significance if one considers

the difficulties an ANM faces during the course of

her work.

Nurses : Problems They Face

The problem nurses face needs to be dealt with

separately. Their contribution has been mostly

towards the care of patients, although they perform

important technical tasks too.

The rural health

services rest largely on the functioning of female

health workers and their non-performance could

very well paralyse the entire rural health network.

Yet their status within the structure of health

services has remained one

of subordination.

Attempts in the past to improve the status and

image of nursing has very often been limited to

increasing the content of the curricula or the tech

nical content of their work. But this only ends up

in reemphasising the fact that 'caring' as a function

cannot be held on par with that of diagnosing and

prescribing.

As women, nurses have an added problem of

sexual harassment which they have to continuously

face both within and outside their work situation.

One reads of newspaper reports of nurses who are

molested, who commit suicide because of sexual

abuse or are murdered for their unwillingness to be

September 1985

casual sexual partner. One could hazard a guess

that the women health workers in rural areas are

probably exposed to such problems to a greater

extent. This is not because the rural males are

different from their urban counterparts but rather

the situation that the nurses are in makes them

more vulnerable. Isolated as they are in remote

villages, with little support from other health

workers these women health workers suffer in

silence out of sheer economic necessity to retain

their jobs. This could also be the reason why such

incidents are under-reported.

Although this problem has been recognised as

a major constraint there has been no systematic

effort to document these incidents or evolve support

systems to tackle such problems. Addition of self

defense into all nursing curricula as a skill to be

developed by nursing students could perhaps be

one such way. But a more realistic solution would

only emerge if nurses' unions take up this issue

seriously to launch a struggle to make their work

place safe. Indeed for such struggles to succeed

they will have to become part of much larger

struggle of all women. The top two categories of

nursing personnel are generally better placed to

form unions as they work in hospitals and are phy

sically proximate. The ANMs on the other hand who

work mostly in the PHCs and subcentres have little

opportunity to come together to raise their collec

tive demand.

The work force employed in the hospital

industry is similar yet distinct from that employed

in other industries. The distinction lies firstly in

the fact that these functionaries work on raw

materials (patients) to produce a non-quantifiable

product 'health'. Secondly, the physicians and

sometimes the nurses who occupy the higher level

of hierarchy view

themselves as professionals

rather than as workers. This often contrasts with

the attitude of non-medical hospital workers who

view their activity merely as a job. But the situa

tion is changing now. Doctors, nurses and other

'professional' health workers are getting unionised

and demanding more and more job benefits, fixed

duty hours and overtime pay, in the process assum

ing the form of wage earners. But even when such

issues are taken up they try to use their'professional'

status to push their point. For instance, in the

recent strike by the interns from medical colleges in

Delhi, a placard was used with the legend 'Doctors

lathi charged! What next!'

Although the demands of the 'professional’

categories are similar to that of non-medical hospital

55

concept of self-help can ever become a viable

alternative to the present system as it exists today.

workers there is little attempt to identify these

issues as common issues and to unionising on the

basis of their identity as workers.

C Sathyamala

C - 152 MIG Flats

SAKET

NEW DELHI 110017

One of the limitations of this perspective as well

as the whole issue on 'People in Health Care' is

that we have concentrated on health workers

functioning as part of the allopathic system of

medicine. We really know very little about health

workers belonging to other systems of medicine in

India, in terms of their role and status. Further even

among the workers in the allopathic system very

little information is available about non-physician

health workers.

In this issue :

Sujit K. Das explores the much debated subject of

the class location of doctors and queries the stereo

typical definition of medical care as a commodity.

Rajkumari Narang looks at various studies in ana

emia to illustrate her contention that the choice

and treatment of problems in medical research is

rarely governed by factors such as people's needs.

Imrana Quadeer examines the impact of the rural

social and economic realities on the Community

Health Worker's Scheme. Sumathi Nair takes a

closer look at four Commumity Health Projects

and asks what their relevance is today. The issue

also carries two articles outside the theme of People

in Health Care. Ekbal reviews the marxist critiques

of the llichian School and Amalendu Das throws

light on dust hazards faced by coal miners

Finally, a word about the people on whom the

'people in health care' work upon. As patients they

are the most powerless in the interaction that

takes place in a health care set up. They are

neither in a position to direct the course of

their treatment nor can they demand a social

accountability from health personnel. The self-help

movement in the west has been a reaction to such

powerlessness. It remains to be seen whether the

SUBSCRIPTION RENEWALS

Is this your last subscribed issue?

A prompt renewal from you will ensure that your

copy of Vol. II No. 3 on 'Systems of Medicine' is mailed directly from the Press. Book

your copies by renewing your subscription now I

Our subscription rates remain :

For individuals — — Rs. 20/- (four issues)

For institutions------- Rs. 30/- (four issues)

Foreign subscriptions :

US §20 for US. Europe and Japan

US S'! 5 for all other countries

(special rates for developing countries)

Single copy :

Rs. 6/-

DDs, cheques to be made out to SOCIALIST HEALTH REVIEW, BOMBAY.

Please write your full name and correct address legibly. And please don't forget to add

Rs. 5/- on outstation cheques /

igz

lot

SHR BACK NUMBERS

We have in stock the following issues :

Vol I : No. 2 - - Women and Health (Reprinted edition)

No. 3 - - Work and Health (Limited stock)

No. 4 - - Politics of Population Control

Vol II No. I - - Imperialism and Health (limited stock)

Vol I No. 1 is out of print. We are planning to reprint it, if we get more than 200

orders - - at a cost of Rs. .10 each. We can get the entire issue photocopied at Rs. 25/If you wish to obtain individual copies of any of the other issues, please send

us for Vol I Rs. 5/- per copy plus postage of one rupee (ordinary post), for Vol II No. 1

send Rs. 6/- plus postage.

56

Socialist Health Review

DOCTORS IN HEALTH CARE

Their Role and Class Location

sujit k das

Doctors have played a central role in health care services. In India medicine has enjoyed both

state and popular support since the independence. State health services expanded rapidly as did the

number of doctors. Many of these doctors went into private practice or migrated to other countries and

others into the state health services. This article explores the much debated subject of the class location of the

medical professi >n. Is the genera! practitioner a productive labourer or a capitalist ? Does the doctor in service

belong to the working dess ? The author draws attention to the effect of the state sector on the medical profe

ssion and traces the growing agitational movements and organisation of state doctors in the country,

with special emphasis on West Bengal. Agair-st this backdrop he queries the stereotypical definition

of medical care as a commodity.

J^jjoctors are the most important people in health

care. Even the official expert group on health,

after unrestrained criticism of the doctor-dependence

of our health system concedes "Moreover, the

doctor as the leader of the team can play an

important role and influence the values and the

quality of caring among the whole staff if he shows

these concerns himself" (HFA, 1981).

Radical

critiques on health care call for reversal of the

doctor-dependence of the health system but never

theless wish for a change towards socialisation and

social

orientation of

the medical profession.

Popularly, doctors |are looked upon as next to

gods since they deal with life and death and no

wonder doctors are often beaten up when a

patient dies or there is allegation of negligence on

the part of the doctor. The popular view offers the

medical profession the key position in health care;

expects it to protect the health of the people;

regards it as the greatest depository of knowledge

and wisdom regarding health; believes that the

weakness of the health care service is due to lack

of adequate

number

of doctors.

From the

Presidents of India down to the Taluk functionaries

they have all been exhorting the medical profess

ion to be patriotic enough to go to the remote

villages and stay there to serve the under-privi

leged rural people

Surprisingly few attempts have been made to

investigate, analyse and understand the medical

profession in the perspective of concrete reality.

Despite its crucial role, the medical profession is

commonly assessed on the basis of subjectivism.

Just as the modern medicine had been borrowed

from the west, the Indian critiques of the Indian

medical profession appear, more often than not, to

have been borrowed from the western radicals. The

September 1985

profession had hardly been looked into as what it

is, but often analysed on the basis of what it

should be.

Development of the Profession

In India the art and practice of healing devolved

on to a group of socially engaged men, and several

systems of medicine developed and have survived

till to-day. Each system was somewhat welldeveloped corpus of knowledge and its practice

had traditionally been taken up by successive

generations. Following the changes in the relations

of production and exchange, independent practi

tioners

emerged.

Later, systems

of modern

scientific medicine (allopathy) and Homeopathy

came from the west and took roots.

In the 19th century, modern medicine had little

to offer. The 20th century, heralded the appearance

and development of a scientific basis and since the

thirties, appearance of chemotherapy and improved

surgical techniques created a surge of interest in,

and attraction towards, modern medicine owing to

its dramatic life-saving achievements. Popular att

raction received a further acceleration around and

after the second world war as a result of the inven

tion of newer wonder drugs and technology. The

practice of modern medicine, likewise, earned a

heightened respectability and soon rapidly emerged

as a profitable livelihood.

Demands for the expansion of the hospital

services have been raised from all corners. The

situation is a parallel of what prevailed during the

expansion of hospital services in the National

Health Service (NHS) of UK. "For the politician, it

might be assumed, there could be no better adverti

sement than a shining new hospital: a visible symbol

of his or her commitment to improving the peoples'

57

health. For the doctors, new hospitals meant the

opportunity to practise what is considered to be

higher quality medicine. For the consumer, in turn.

new hospitals surely meant better services with

higher standards of treatment (Klien, 1984). No

wonder therefore, in a market economy, almost all

aspiring doctors moved towards the practice of

curative medicine with its life-saving and relief

producing implements. Iliffe has put it succinctly,

“Just as abortion would be a sacrament if men

became pregnant, so health professionals would

stampede into preventive work if prevention could

be made into a marketable commodity” (Iliffe, 1983).

Introduction of welfare activity by the state saw

the expansion of state health care service and the

number of health personnel increased rapidly

(Table I). Later, indigenous systems and homoeopa

thy, for reasons not discussed here, also received

state patronage.

Table I

Year

No. of Med.

Colleges

Students admitted

50-51

60-61

70-71

80-81

28

60

95

106

2675

5874

12029

10934

Qualified

1557

3387

10407

12170

Figures are incomplete as: a few centres failed to report.

Source : Health Statistics of India ( 1982) : C.B.H.I.,

Ministry of Health & F.W., Govt, of India.

Table II Year I98I.

Total No. Went Returned Regd. in No. admi- Total No.

registered abroad from

Employ tted in P.G. Regd.

abroad

ment

Courses

Doctors

in other

systems

268,712

4766

2381

16406

8241

382,686

Source : Health Statistics of India (1982) and

University of Calcutta.

These doctors opted for private practice or

other employment or post-graduate education for

specialisation, or migration to foreign countries. For

the last few years more than 2000 doctors have

been settling abroad annually. There is no available

data to indicate the number of doctors engaged in

each category but the distribution follows the mar

ket situation and economic compulsion. Old pattern

of general practice recruits less and less. Number of

women doctors has been steadily increasing since

1976-1977 and they generally settle towards certain

culturally chosen occupations e.g. gynaecology and

obstetrics, pediatrics, pathology, plastic surgery,

anaesthesiology, non-clinical disciplines in medical

58

colleges and also dental surgery. Most of the

women opt for employment and independent wom

en private practitioners prefer G & O and Pedia

trics. Unemployment is a late development (Table II).

Class and the Medical Profession

Private

Practice and General Practice

In West Bengal, approximately 70 percent

doctors are engaged in private practice. They in

clude independent practitioners. Insurance Medical

Practitioners

of ESI (M.B.) Scheme, part time

practitioners of the state and private sector emp

loyees. The General practice has been changing

with changing social relations, scientific developme

nts and cultural attitudes. In earlier times, the general

practitioners (GP) could not demand any consultati

on fee and had to distribute drugs to his clients. He

then used to incorporate what he considered to

be his due consultation fee, within the price of the

drug. As a result, the consumption of non-essential

drugs and compounded drugs was high Also the

actual price of a compounded drug is difficult to

check and verify.

Later, consultation fee has

gradually been introduced and has received public

acceptance, resulting in the development of a

class of GPs who are only prescribers.

Indian society has a long tradition of voluntary

efforts for charitable medical care to the community.

In fact, a good number of clinics and hospitals

had been established through philanthropic end

eavours. In order to earn and maintain 'nobility',

the price doctors had to pay was to attend to

emergency patients, give free 'service' to a few

indigent patients and offer honorary service in the

voluntary institutions. Besides respect, speedy reco

gnition and fame, this attachment to charitable

institutions used to bring other material returns.

The doctor used to test the emerging therapeutic

techniques on poor patients without informed con

sent and without risk and later employ the technique

thus perfected, in cases of

paying clientele

in the private practice. Actually, the situtation

is so advantageous that there is serious competition

among the contending doctors to secure honorary

employment in the charitable medical establishments.

A sort of corrupt practice was also rampant where

the patients had to pay the honorary doctor in order

to avail of the free hospital service. This mal

practice has now been almost eliminated in West

Bengal due to higher level of consciousness of the

people, but is still in vogue in many other states.

The GP therefore, acts as a retailer of drugs;

sells his skilled labour designated as 'service to

Socialist Health Review

individual buyers; and it may further be argued that

he employs his knowledge and skill as capital and

sells the product of his own labour in the market

as commodity. Is he a productive labourer or

capitalist? Karl Marx, in his inquiry into the social

status of independent handicraftsmen and peasants

as well as that of producers of non-material produc

tion e.g

artists,

actors,

teachers physicians,

etc., said ''It is possible that these producers,

working with their own means of production, not

only reproduce their labour power but create surplus

value, while their position enables them to appro

priate for themselves their own surplus-labour........

And here we come up against a peculiarity that is

characteristic of a society in which one definite mode

of production predominates, even though not all

productive relations have been subordinated to it. ...

The means of production become capital only in

so far as they have become seperated from labourer

and confront labour as an independent power. But

in the case referred to the producer - the labourer is

the possessor, the owner, of his means of produc

tion. They are therefore not capital, any more than

in relation to them he is a wage-labourer*' ( Marx ).

The GP is actually engaged in a precapitalist mode

of production, but nevertheless produces commo

dity of use value and sells it for exchange value. Our

much maligned GP is not altogether a demon or

blood sucker. He is just a small commodity pro

ducer who still renders essential service which the

state is unable to provide for. A close study of

the GP will reveal how the western medicine took

roots here, changed the health culture and in the

process changed its own.

Speed of expansion of the market of private

practice has lately been thwarted and is gradually

being squeezed for several reasons. Increase in

the purchasing capacity of the people cannot keep

pace with the increase in the number of doctors

thrown into the market. Secondly, expansion of the

state sector in medical care has been impressive

and concentrated in the urban areas and these are

totally free or heavily subsidised. Socially dominant

classes who can afford to purchase medical care,

have been able to capture the largest share of

the free/subsidised state service. As a result, private

sector medicare did not develop to the expected

level. Thirdly, private practice has a latent period

to reach profitability. Lately, increasing numbers

from the lower income groups have been recru

ited in the medical profession, who cannot afford to

sustain this latent period. All these have resulted in

increasing trend towards employment and migration

abroad, unemployment and underemployment.

Doctor-in-Service

Expansion of organised medical care service

through state, public undertakings, ESI, big private

industry and voluntary organisations has resulted

in a marked increase in the number of doctors in

employment. Though private medical practitioners

still constitute about 3/4th of the medical profe

ssion, the doctors-in-service attract the major, if

not entire, attention in any debate on health care

owing to the fact that the organised sector is the

trend-setter and almost always features in planning

and debate In this context, the present discussion

dwells largely on the doctors-in-service among the

practitioners of modern medicine. However, no

discussion on the medical profession or for that

matter, medical care is compreshensive unless it

also includes private practitioners of modern medi

cine and of the other systems.

The non-practising employed doctor is actually

a wage earner destined to identify himself with the

aspirations of similar wage-workers of the so-called

white-collar category. Though the 'noble profession'

ideology provides an excellent instrument for the

private practitioners to maximise profit in their

trade, it has ironically proved to be a constraint

in the way of fulfilling his aspirations. Because

ot the stigma of 'noble profession', he cannot claim

fixed duty hours; cannot claim 'overtime' i.e. extra

remuneration for extra work; cannot employ 'redtapism' in his daily work-load; cannot even utilise

his earned leave to escape from the drudgery of fre

quent emergency duties. He is further handicapped

in regard to democratic rights so much so that

unionisation of doctors is frowned upon by the

society; agitative action is taboo; call for strike

in hospitals is taken to be sheer blasphemy. On

top of it, the doctor has little hold in the administra

tion of medical care and in the matters of policymaking, programming and power hierarchy, the

doctor is placed in a lower position subordinate

to the generalist administrator But more about this

later.

Do they, then, belong to the working class? The

question has never been raised or debated. On this

issue, the dogmatic marxists adhere to Reductio

nist ideology. ' Reductionism involves a version of

historical materialism which presents all social

phenomena as 'reducible' to, or explicable in terms

of, the 'economic base'. Thus political struggles

or social ideologies are explained as manifesta

tions or

'reflections'

of economic forces. In

this presentation marxism is reduced to asset of

4

September 1985

59

relatively simple and universal 'laws'.......... Such a

position is guilty of 'essemialism', that is of seeing

the economy as embodying the essence of all

social phenomena which are then simply expressed

or made manifest in the social world” (Hunt, 19/8).

This methodology necessarily attempts to define

classes at the economic level and attaches little

importance to the forces operating at the political

and ideological level Working class is differentiated

by the difference between productive and unprodu

ctive labour. Mera wage-earning or labour-selling do

not provide entitlement for entry into the working

class. ''The working class in the capitalist mode of

production is that which performs the productive

labour in that mode of production......... Although

every worker is a wage-earner, every wage-earner is

certainly not a worker, for not every wage earner is

engagedin productive labour ' (Poulantzas, 1 975).

While in cases of white-collar wage-workers of

the industry, transport and mercantile enterprises,

Marx concludes that they are productive labourers,

the physicians-actors-teachers etc. are also produc

tive labourers. He observes, when they sell their

labour power (manual or mental) in a capitalist

establishment which appropriates their surplus labo

ur and makes a profit by selling the products

as commodities. But he adds, "All these manifes

tations of capitalist production in this sphere are

so insignificant compared with the totality of

production that they can be left entirely out of

account” (Marx, 1978).

Technology, capitalist organisation of produ

ction and productive forces are much more devel

oped now than at Marx's time, though the develop

ment of medical care service as a sector of capitalist

industry is still rudimentary in India. The new

’ working class of advanced capitalism — the

technicians, engineers, scientists etc. — is held, by

Serge Mallet, not only to be revolutionary but the

'avant-garde' of the revolutionary socialist move

ment (Mallet, 1975). Services have long been deve

loped into profit making industry in the developed

countries.

Here in India, doctors as wage-earners are

now commonplace. To what class do they belong?

The established left still subscribes to the liberal

concept of health care and therefore, has yet to

face this question. The progressive view, however,

is confusing, to say the least. "The capitalist can

organise the production of surplus value through

the provision of health care and can realise higher

profits in this service industry. It is immaterial

60

whether the surplus value is realised directly

through the productive activities in the clinics and

hospitals owned by the Capitalist or indirectly,

through the provision of health care by the State to

maintain or increase the productive capacity of the

labour” (Jesani and Prakash. 1984). Such an

assertion is based on dubious premises that medical

service has developed into an industry; that the

State also acts as a productive enterprise; and that

State Health Care Service is an organised invest

ment by the capitalist class on the

industrial

productive labour.

What then is the status of the producers of

'health care' ? The above assertion automatically

places the employed doctors into the category of

the working class. But alas, the entire medical

profession carries, in the radical viewpoint, the

same class background as the bourgeoisie and

performs its predestined social task of legitimisingstrengthening and maintaining the bourgeois medici

ne. Why this confusion? ''The mere quantum of

the so-called marxist analysis of health, done in the

West has so impressed us that we have literally lifted

their formulations and transplanted them on the

Indian scene, without even thinking whether they

are applicable. Further, in our hurry to fill in the

gaps in our knowledge, we have concentrated on

theory of health and medicine. That theory, however

has been sought by filling the accepted theoretical

constructs with Indian data and developments rather

than beginning with health and health services itself

to test the assumptions as well as the theoretical

constructs” ( Quadeer, 1984 ). In other words, in

order to understand and analyse its status, role,

trend and potential in health care, we have to make

an actual study of the medical profession in its con

crete reality.

Professionalism

"Professionalism within health care is based on

the idea of 'service' and on the practice of trade.

It is a market concept expressed in the relationship

between a customer (the patient), a tradesman (the

professional) and assorted suppliers (the drug

industry, other superior professionals). Trade secrets

are necessary for the maintenance of the market

relationship, and permit professionals to define

themselves as special, and beyond the control of

those ignorant of these 'trade secrets'. The auto

nomy of health professionals — particularly doctors

rest on the range of their trade secrets” (lliffe 1983).

With this conception it follows that professionalism

could be curbed or even abolished with the

Socialist Health Review

abolition of market economy i. e. private trade or

commodity market in health care. This appears to

be another instance of radical presumption. Profe

ssionalism is not a creed peculiar to the medical

profession nor to the bourgeois ideology. Professio

nalism not only regins in private medical trade but

also exists among the employed non-practising

professionals, among the medical teachers of nonclinical disciplines and among the doctors engaged

in public health work.

Professionalism exists in pre capitalist economy

and continues in the post-revolutionary societies

where the ownership of the means of production

has undergone a change and private trade almost

abolished. In a round table discussion on private

medical practice organised by WHO, it has been

revealed that private practice, in certain forms

exists and is developing in the socialist countries

(Roemer, 1984) Medical co-operatives are spring

ing up where state-employed doctors are allowed

to spend upto two hours a day and are entitled to

a 50 percent share of the payment received from the

patients in cash for the services rendered. Even in

China, barefoot doctors who are essentially parame

dics, are allowed part-time private practice. A common

practice developing in these countries is that of

giving gifts to doctors in hospitals and often the gifts

are relatively large amounts of money. All this is

done to ensure better quality of service (which is by

no means certain). How is the quality of service to

be determined ? How are measures and gradations

to be made ? There is as yet no acceptable indicator

or scale. Hence, quality will be determined diffe

rently by different social ideologies and health

cultures, and the latter are manipulated by profe

ssionalism. Specialisation and mystification are

only other facets or instruments of professionalism

utilised to maximise the price of medical service in

private practice.

Specialisation, however, is not an exclusive

exploitative imposition. It is also an integral part of

social division of labour, not only unavoidable but

necessary in any social formation including the one

based on non-exploitative mode of productionWhat is relevant is not to confuse social division

of labour with capitals' division of labour. In an

analysis of modern chemical industry in UK Nichols

and Beynon have shown that though technical divi

sion of labour is a must in any industry in any mode

of production, in the capitalist mode the technical

imperatives are subordinated to political imperatives

and technology exists to serve and augment capital.

September 1985

"Certainly in any mode of production, given the exi

stence of specialised training, some men will be

more technically competent to solve certain problems

than others This is so obvious as to hardly require

stating. But something else which should also be

obvious is often ignored. For concern with the tech

nical structure of complexes like Riverside (the fact

ory site) can also tco easily obscure the fact that

they are not even designed to make chemicals, but

to make chemicals for profit The reality is that their

division of labour is capital's division of labour.....

(Nichols and Benyon, 1977) Professionalism, also,

could make its contributions in the struggle against

the ruling class and the state. The history of the

development of health care service in Great Britain

has shown that the professionalism of the doctors

thwarted, at different stages, the attempts of the

state to reduce or withdraw the medical benefits

demanded by the people Here in India also, profe

ssionalism often reinforces the demands of the peo

ple for the egalitarian distribution of medical services

against the discriminatory practice of the state.

What do we expect from the doctors? Here, the

bourgeois, left, radical and popular views converge

and appear as if grossly influenced by the ideology

of professionalism. A doctor should render utmost

efforts irrespective of the socio-economic status of

the patient; should always ungrudgingly serve emer

gency patients without consideration to his own

convenience; should always be guided by the code

of ethics formulated by the profession; should act

as a friend-philosopher-guide to the patient; should

exude hope and confidence in his conduct etc. etc.

Concomitantly, the community accorded certain

privileges to the profession. The doctor knows best;

he should not be questioned; he has the unchallen

geable right to handle and manipulate the patient's

body; his good faith is taken for granted even in

cases of the patient's death and disability.

What do the doctors think about their own role

expectation? In a large study in two medical college

hospitals in Tamilnadu, Venkatratnam revealed that

the doctors' understanding of their role expectation

is a composite of their own individual perception,

occupational

compulsions

and

organisational

( professional

and

institutional )

principles

(Venkatraman, 1979). Role expectation comprises of

professional, academic, research, managerial and

social. Many interesting facts and controversial

issues regarding doctors' responsibility towards

patients,

role towards other health workers,

requirements of teaching-training-research, level of

61

communication with patients, social responsibility

and so on have been revealed in the above study

and these should be analysed before rushing to

issuing sermons on doctors'

role expectation.

Peculiarly, the 1CMR-ICSSR report, while casti

gating the profession for its negative attitude

towards preventive and promotive health care

recommends for their'alternative model’ of health

care service that "the doctors will still continue to

play an important role in the new health care

system. But this will not be over-dominating and

will be confined more and more to the curative

aspects of the referral and specialized services for

which they are trained” (HFA 1981).

Universally, the understanding of role expec

tation of the doctors suffers from an idealistic

approach. All expect the doctor to be humane,

shorn of commercial urge, dedicated to patient's

welfare, imbibed with principles of social justice

etc etc. No one asks why the doctor should follow

such a model or what objective conditions may

compel him to do so? Or for that matter, what objec

tive conditions persuade the doctor to do as he does?

Perception of role performance differs between

the professionals and the consumers for obvious

reasons. Confusing and paradoxical situations pre

vail. While the State hospitals and the doctors are

almost always on the dock by the consumers and

mass media for the severe shortcomings in role per

formance, the very same hospitals and the professi

onals are very much in demand for their high

quality and indispensible medical service. True, the

service is attractive because it is free. But even

amongst affluent consumers the notion prevails

that the hospital doctors are more skillful, know

ledgeable and equipped. Generally, the doctors'

notion on role performance is that they do their best

under the given circumstances and they could do

more if they have a free hand in the administration

which is responsible for the constraints. The factors

underlying these confusions and paradoxes are

being unravelled by the growing momentum of the

organised movement of the doctors.

Doctor's Organisations and Agitations :

West Bengal

Medical practitioners got themselves organised

under Indian Medical Association in the thirties.

Later, practitioners of each speciality discipline built

up separate associations. The basis of these ass

ociations is professionalism, academic and pseudoacademic. It should be mentioned that non-clinical

and even public health disciplines organised their

62

own associations. But the associations could not

cope with the task of tackling the emerging aspi

rations of the employed doctors.

In fact, a

contradiction developed between them. Ironically,

the bone of contention was economic as well as

ideological. The ideology of professionalism appe

ared to be a drawback for the service-doctors.

The pay packet of service was unattractive not

only in comparison with the income in private

practice but also compared unfavourably with that

of the similar category of government officers,

for instance the civil service, or the engineering

service.

This situation had been a hangover

from the British days when doctor's pay packet

was deliberately kept low with the understanding

that they would make it up with the earning from

private practice, a privilege then enjoyed by all

service-doctors. Later, with the expansion of the

state sector, more and more doctors had been

employed on non-practising basis but this principle

of wage policy did not change.

In matters of job requirement, job perquisites

and job satisfaction, there was nothing glamour

ous to look forward to. Duty hours was virtually

feudal - a doctor was 'on call' for 24 hours a day for

emergency need and seven days a week; almost all

health centres in the rural areas were manned by one

doctor in each; there was no ceiling on the number

of patients one had to attend daily; a rural medical

officer, in addition to his clinical duties, was entrusted

with the tasks of family planning, MCH, School Hea

lth, Immunisation, Epidemic Control Administration

and what not. System of recognition and appreciation

of good and dedicated service was absent. Avenues

for higher education, promotion, research, or even a

transfer to a better post after a scheduled period of

service, were severely limited. Because of longer

period of training to acquire qualification, a doctor*

usually enters service at a later period compared to

others andconsequently is entitled to a lower pension

and lesser amount in the retirement benefits.

The state hospitals were always understaffed

and underequipped and hence, the scope of prac

ticing what the doctor was trained for, was thereby

Limited. On top of these, the health administration

was run by the generalist administrators. These

people had no career attachment to the health

department; were not answerable for failure or

mismanagement; had no inclination to learn the

problems of the health care service as well as of the

employees. The doctor had no voice in health plann

ing, hospital service development and technical deve

lopment. The autonomy enjoyed by the profession

Socialist Health Review

in regard to clinical practice in the NHS of UK was

not even partly granted to the doctors here. On

the other hand, the political authorities found it

convenient to put the blame on doctors and other

health workers for all their failures, misdeeds and

incompetence in the health sector. Consequently,

doctors and the health workers, as they were the

ones, at the counter, had to suffer the burden of

public wrath in the form of physical assault, humi

liation, abuse and so on.

What did the doctors do to overcome these

adversities? It is worth while to note that the

state service was last in the list of priorities of a

new medical graduate. The order being private

practice, specialisation, migration abroad and if

all fail — then he opts for service. Lately, because

of competition, the options have shrank greatly and

large numbers are now competing among them

selves for limited state service; doctors from Orissa,

Assam, Bihar, Bangladesh are now applicants to

the West Bengal State Service.

In this situation how have the service-doctors

reacted ? Quality has been the first victim and

expectedly so. No matter whether 50 or 500 attend

the outpatients clinic the experienced doctor mana

ges to tackle them within 3 hours or so. In a

100-bed hospitcl, 200 patients stay indoor regularly

but the same number of doctors and health workers

treat them without spending any additional timeinthe

hospital. The next escape route is private practice —

both authorised and unauthorised. In west Bengal

except in the case of clinical teachers of the majoritv

of medical colleges and doctors in the district and

subdivisional hospitals, private practice is not allow

ed. In fact, 7/8th of the State doctors are non

practising. The States of Orissa, Andhra, Maharasht»a, Punjab, Hariana and others have either

entirely or partly non-practising state service. Some

other states have indicated that they will too follow

suit. The entire Union government and the public

undertakings sector is non-practising. Expectedly,

most doctors aspire for the limited practising

privilege of the service and in the non-practising

sector, unauthorised private practice is growing

wherever there is scope and opportunity.

The question of the alleged reluctance of the

doctors to serve in the rural institutions should be

understood and analysed with this background in

mind. Concerned people have swallowed the

government propaganda

that because of such

reluctance on the part of the doctors, the govern

ment despite earnest efforts and liberal financial

September 1985

allocation, fails to provide medical care to the

rural

people. By absorbing

this propaganda

uncritically, the health activists on the one hand,

unwittingly agree with the

government that

medical care is synonymous with the presence of a

doctor, fall in another trap that provides for offer

ing barefoot doctors Homoeopaths-Ayurveds and

simple home remedies for the villagers in the

garb of tradition, indigenous culture and community

medicine. The fact is otherwise. It is deliberate

government policy to keep the service conditions

of the rural medical officers unfavourable with a

view to discourage the doctors from taking up

rural postings; and in this attempt, one must admit,

the government has been successful to the exent

that even the occasional few socially conscious

people-oriented young doctors, after a stint of

rural service, try their utmost to move to the urban

area or quit. ‘ The Siddhartha Roy Congress govern

ment's regulation of 1974 stipulated that physicians

with specialist degrees would enjoy a higher pay, a

special allowance and would be exempt from rural

postings. It was only natural that young doctors

went in for specialisation just for the sake of

avoiding rural posting, if not for higher emolu

ments. The Left Front government has not felt it

necessary

to

change

the

regulation'' (The

Statesman, 1985). This policy in fact, induced even

those doctors, who had already settled in the

rural areas, to move for any type of specialisation

and settle in urban areas. Does it show reluctance

on the part of the doctors or that of the government ?

Lately, the Marxist Left Front government in West

Bengal introduced against the protest of the

medical profession, a short term three year medical

course to train up doctors who would fill up the

rural vacancies. Next year, the junior doctors in the

State launched agitation for jobs in the State

service and demanded that all rural posts be immed

iately filled up by currently eligible 3000 unemployed

young medical graduates. Under public pressure,

the Left Front publicly declared that there were no

such vacancies and they were unable to provide

jobs, not even in the rural areas. The short-term

medical course had to be wound up in any case,

the discrimination against the rural medical officers

persists. No one, of course, raises the question why

doctors, of all people, must go and serve the

villagers who are ignored in respect of all other

consumer goods. It must be understood that the

recent organised demand of the junior doctors for

rural appointment is not due to any sudden surge

of patriotism but simply due to pressure of

unemployment.

63

In course of time, however, the consoling

compensation through private practice turned out

to be insufficient. Service-doctors and junior doctors

ventured to organise their own bodies on trade

union basis to voice their grievances which did not

find deserving place in the earlier professional

bodies like IMA which was dominated by private

practitioners. In 1973, junior doctors launched a

movement in West Bengal demanding better pay

and service conditions, and better provisions in the

State hospitals They had to go on strike and come

out partially successful by obtaining pay hikes.

In 1974, the State doctors 'in alliance with the

State engineers) resorted to strike for 41 days but

maintaining the emergency services. Their demands

were not only economic but encroached on the

political and ideological level. They demanded

exclusive executive power for

the scientists,

technologists and professionals in the scientific and

technical departments of the State administration

which were the preserve of the generalists, and

parity in pay scale with the Indian Administrative

Service (IAS). This agitation generated intense

debate throughout the country and the issue has not

yet been settled The West Bengal government

ultimately made a few concessions but unfortunate

ly, with the subsequent imposition of Emergency in

the country, the terms of the agreement were

not implimented, leaders were sacked and doctors

terrorised. The fall out of this agitation was visible

elsewhere; the pay scale of the doctors in the Union

government and public undertakings were soon

revised upwards to bring it on par with that of the

IAS at the lower level.

This agitation made a breakthrough on several

grounds.

People

saw to their surprise that

renowned professors and principals of the medical

colleges, eminent specialists and senior engineers

holding high ranks in the state service, walking in

processions, squatting on the pavements and

holding street-corner meetings. It then struck them

as a novelty that the 'noble' doctors could resort

to agitative ways that befit only common workers.

Doctors, it was stressed, had no right to jeopordise

the well being of the patients by striking. This

agitation, perhaps for the first time, focussed

people's attention on the affairs of the medical

service, particularly into the government assertion

that the doctors and health workers were respo

nsible for all the ills in the system. This agitation

was followed by a series of agitative movements

all over the country, mostly by the junior doctors

but also by the state doctors in Delhi, UP, Orissa,

64

Assam, Maharastra

Andhra, Bihar - though with

different demands as was expected owing to diff

erent levels of development. Everywhere, organisati

ons of service-doctors sprang up independent of the

IMA. The agitation in West Bengal also brought

changes in the orientation of Bengal IMA, which

despite its long history of co operation with the

government had to come out actively in support

of the service-doctors and junior doctors.

Sporadic movements on various issues such as

reduction of job burden, physical security at the

work-site, better provisions for emergency care,

improvement of rural medicare and more scope for

higher education have taken place culminating

in the 1983 statewide movement.The junior doctors

demanded, besides bettrer pay, service conditions

and provisions for emergency care and a health

policy with priority to preventive care. The Left

Front Government took recourse to unprecedented

repressive measures using party cadres and the poli

ce. Brutal police violence on the junior doctors

brought state doctors onto the scene, also in an

unprecedented manner. Perhaps for the first time in

the world, state doctors in their strike action with

drew from the emergency services. This was an

organised retaliation of the doctors against organised

terrorism of the Left Front government who reiterated

the earlier declaration of the Congress regime that

the doctors had no right to strike The government

had also earlier started denying the doctors the

right to any agitative activity

This was strange

and definitely unacceptable to doctors who had

to earn democratic rights through hard struggle in

1974 when the conduct rules for the government

servant had been revised. The doctors received,

unprecedented public support even though they

committed such so-called anti-humanitarian acts as

deserting the emergency counters. The government

finally had to withdraw the victimisation and

punitive measures

and concede the immediate

demands of the strikers.

There are now indications that service doctors

are now beginning to realise that the aspirations of

their occupation are directly related with the nature,

object, standard and extent of the state health care

services. They have now raised the demand for

clear declaration of the aims and objects of the

state health policy and a controlling role in impl

ementation, a plea to share responsibility with power.

The service-doctors in West Bengal demanded that

free state medicare be exclusively reserved for the

indigent population only, which produced indignant

protests not only from the privileged middle class

Socialist Health Review

but a few political parties with 'Left' labels. Diff

erent mass organisations are now holding meetings

and seminars on the health policy and state health

acare administrlion There has also been a renewed

spurt in the agitative movement of the junior doctors

and service-doctors in other states for instance Bihar,

UP, Orissa, Maharastra and Delhi.

These organised movements of the service

doctors brought many undiscussed issues into

public attention. Should the doctors be treated as

a special occupational group with limited democra

tic rights and additional responsibilities to society?

And if so, why? What are then the limits of the

forms of agitation for the doctors, if they have

grievances to agitate for ? Are the doctors also

entitled to fixed duty hours just like others? Why

should doctors alone have a moral or social obli

gation to serve the villagers who are deprived of,

and are discriminated against in respect of all other

commodities and services? Should the generalists

enjoy the power and the doctors bear the respon

sibility of state health care service? And finally, who

doctors are primarily responsible to, the employer

or to the patients or to their professional ethics?

The foregoing development and issues per

suade us to take a new approach — the marxist

approach — to determine the role expectation and

analyse the role performance of the medical pro

fession. In a market economy, the medical professi

on cannot but be governed by its rules and to

expect them to swim against the current is an

utterly idealistic proposition. The service-doctors

tend to behave as other wage-workers do. They

try to extract as much wage with as little labour

as possible, in contrastwith the employer's tendency

to extract as much labour with as little wage. It is

all very well and easy to define 'medical care' as

a commodity in the capitalist mode of production

but it needs explaining how the universally free

state medicare remains a commodity and behaves

as a commodity. Or what here is the relation of pro

duction between the owners of the means of pro

duction and the sellers of labour power? It needs

study to understand why the primary need of food

clothing-shelter is denied to a dying citizen but free

medicare service is demanded and created and, the

nature of the class struggle that brings about this

state response. All these studies in the concrete

reality of the Indian situation will bring us back to

the question of class identification.

Conclusion

"The separate individuals form a class in so far

as they have to carry on a common battle against

September 1985

another class; in other respects they are on

hostile terms with each other as competitors. On

the other hand, the class in its turn assumes an

independent existence as against the individuals,

so that the latter find their conditions of life

predetermined, and have their position in life and

hence their personal development assigned to them

by their class, thus becoming subsumed under it"

(Marx and Engels 1976’. The individual s role in the

production process, his location in the social

relations of production, the productive or unprod

uctive nature of his labour - all these form the

basis of inquiry. But as regards the identification of

class, the common interest, common behaviour and

common action, which are often independent of

individual wills, — or the common outlook towards

social events, political and.ideological orientations —

are also important and often act as positive forces.

To this Engels has drawn attention : "The econo

mic situation is the basis, but the various elements

of the superstructure-political forms of the class

struggle and its results, to wit.

Constitutions

established by the victorious class after a successful

battle etc., juridical forms, and even the reflexes of

all these actual struggles in the brains of the

participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories,

religious views and their further development into

systems of dogmas - also exercise their influence

upon the course of the historical struggles and in

many cases preponderate in determining their form"

(Marx and Engels 1965) In order to understand the

social role of a group of similarly placed wage

earners, their historical development in relation to

the changes in the mode and relations of production

as well as their political and ideological expressions

vis-a-vis the dominant political and ideological

current in the given society, are to be studied.

Class is actually, a historically developed, ideo

logically

shaped and economically determined

dynamic relationship expressed

through

class

struggle. Thompson's notion of class reveals this

aspect. 'By class I understand a historical pheno

menon. unifying a number of disparate and seem

ingly unconnected events, both in the raw material

of experience and in consciousness. I emphasize

that it is a historical phenomenon. I do not see

class as 'structure' nor even as 'category', but as

something which in fact happens (and can be

shown to have happened) in human relationships ...

Like any other relationship, it is a fluency which

evades analysis if we attempt to stop it dead at any

given moment and anatomize its structure... The

relationship

must always be embodied in real

people and in a real context" (Thompson 1982).

65

The social role of the employed section of the

medical profession is therefore, determined by their

role in the dominant mode of production and

by their interaction classes in the social events.

Sellers of labour

power primarily sell

their

labour power to earn a living not to produce

commodities. By the complexity of social division of

labour, some have greater interest in their products

while others have greater interest in the production

process. Each of the occupations has an ideologi

cally determined skill, status and price. All have

common despair in unemployment and all undergo

the similar feeling of inferiority, helplessness,

subordination and subjugation in relation to their

employers. Vic Allen, thus describing the wage

earners,

concludes that bourgeois sociological

stratification of different hierarchical classes and

the reductionist categorisation of productive and

unproductive labourer without empirical substantation, will not be helpful in an attempt to differentiate

between wage earners (Allen 1978). In the case of

health professionals, the study should go much

deeper and wider. Health and medicine are not

mere sterile figures or say, mortality and morbidity

statistics. Illness involves pain, fear and desperation

in real life and these saturate the milieu wherein

medical

care operates. Cultural instincts and

ideological creeds strongly influence and occasion

ally determine medicine and medicare. Medicine in

its practice and institutional forms is not merely

commercial

exploitation or oppressive

power

relations imposed by the dominant class — as

radicalism may have us believe — but is a resultant

of class struggle, of antagonistic and non-antagonistic contradictions between classes; of interactions

at the economic, political and ideological levels

The question of the role and behaviour of the

medical profession is relevant to the building up of

a Peoples Health Movement (PHM). PHM is not

merely imparting health education to the individual

or

community. PHM does not end with the

exposure of the inadequacy and exploitative nature

of capitalist medicine. PHM needs to acquire

expertise, to develop sound scientific basis of

egalitarian health system, to search for the mechaanics of building up of a socialist health culture

and to strive for subordination of medical science

to social needs and aspirations. It is a stupendous

task and the role of the health professionals is

crucial. This necessitates objective study of the pro

fession before theorising study of the developing

contradiction in the profession and the nature of

the contradiction; the dialectics of the medicine; the

66

development of the elements of socialist medicine

during bourgeois dominance; the dialectics of

cultural change and development. In the ensuing

struggle the weapons of the bourgeois science and

technology ought to be counterpoised by the wea

pons of peoples' science and technology. Involve

ment of the medical personnel will not be determined

by humanist exhortation or so called deprofessionalisation but by class contradiction and class struggle.

The medical profession or a section of it - be it cate

gorised as the 'new petty bourgeois' (Poulantzas,

1975) or the 'new working class' (Mallet, 1 975) wilhave its own determinant role to play and the PHM

activists must need to analyse and understand this

role in order to formulate the strategy and tactics in

the emerging social events of the health sector.

Sujit K. Das

S 3/5 Sector III,

Salt Lake, CALCUTTA 64

Reference

Allen, Vic : The differentiation of the Working Class in Class and

Class Structure, edited Alan Hunt, Lawrence Wishart,

p 7, London 1978.

Health For AH - An Alternative Strategy : ICMR - ICSSR Report :

Indian Institute of Education, Pune, p 209, 91, 1981.

Hunt, Alan Class and Class Structure (Ed. A>an Hunt', Lawrence

and Wishart, London, p 7, 1978.

Iliffe, Steve : The NHS : A Picture of Health?

Wishart, London, p 150, 147 1983.

Lawrence and

Jesani, Amar and Prakash, Padma: Political Economy of Health

Care in India, Socialist Health Review. (I: 1 ) 30, June 1984.

Klein, Rudolf : The Politics of The National Health Service, Long

man, London, p 75-76, 1984.

Mallet, Serge The New Working Class. Spokesman Books, Notting

ham, 1975, p 25-32.

Marx, Karl Theories of Surplus Value. Part I, Foreign Languages

Publishing House, Moscow, p 395-6, 399