Socialist Health Review 1985 Vol. 2, No. 1, June Imperialism & Health.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

UNITY HEALTH CELL

< • .7 Main, I Block

AOramongala

ngalore-56t034

India

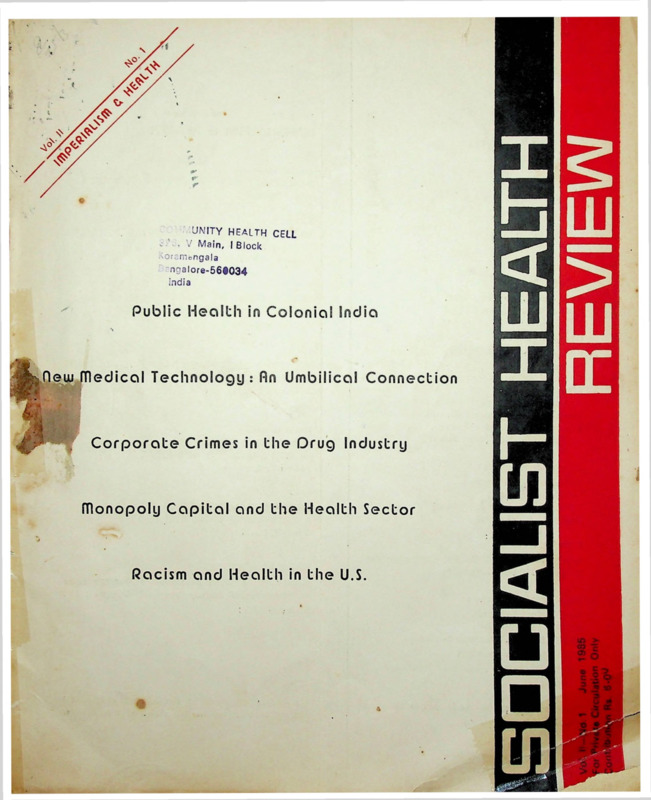

Public Health in Colonial India

medical Technology: An Umbilical Connection

Corporate Crimes in the Drug Industry

monopoly Capital and the Health Sector

Racism and Health in the U.S.

Vol II

Number 1

IMPERIALISM a HEALTH

1

Editorial Perspective

HEALTH AND MEDICINE UNDER IMPERIALISM

Anant Phadke

6

00

THE COLONIAL LEGACY AND THE PUBLIC HEALTH

SYSTEM IN INDIA

Radhika Ramasubban

Working Editors :

17

Amar Jesani, Manisha Gupte,

Padma Prakash, Ravi Duggal

TRANSFERRING MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY:

REVIVING AN UMBILICAL CONNECTION ?

Meera Chatterjee

Editorial Collective :

Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (A P),

Imrana

Quadeer, Sathyamala C (Delhi),

Dhruv Mankad (Karnataka), Binayak Sen,

Mira

Sadgopal

(M P),

Anant

Phadke,

Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar, Jean D'Cunha,

Mona Daswani, Srilatha Batliwala (Maharashtra)

Amar Singh Azad (Punjab),

Ajoy Mitra

and Smarajit Jana (West Bengal)

Editorial Correspondence :

Socialist Health Review,

19 June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay - 400 050 India

23

MONOPOLY CAPITAL AND THE REORGANIZATION

OF THE HEALTH SECTOR

J. Warren Salmon

38

Bhopal Update

TRAGEDIES & TRIUMPHS :

HEALTH & MEDICINE IN BHOPAL

Padma Prakash

45

RACE AND HEALTH CARE :

A PERSPECTIVE FROM CHICAGO

Bindu T. Desai

Printed at:

Omega Printers, 316, Dr. S.P. Mukherjee Road,

Belgaum 590001 Karnataka

REGULAR FEATURES

Annual Contribution Rates :

Review Article : John Braithwaite's Corporate Crime

in Pharmaceutical Industry by Ravi Duggal : 31 ;

Rs. 20/- for individuals

Rs. 30/- for institutions

US$20 for the US, Europe and Japan

Dialogue : 43 ;

US $15 for other countries

We have

countries.

special

rates for

developing

(Contributions to be made out in favour of

Socialist Health Review.)

The views expressed in the signed articles do

not necessarily reflect the views of the editors.

Editorial Perspective

HEALTH AND MEDICINE UNDER IMPERIALISM

Jmperialism is

the

highest

stage

of

capitalism

wherein monopoly capital dominates the life of

society. Monopoly capital leads on the one hand,

to a tremendous development of the productive

capacity of human society, the spread of relations

of wage-labour and capital throughout the world;

but on the other hand, the private monopoly over

these productive forces leads to its underutilisation

its distorted development and the domination of

one country or a group of countries over others

either in the form of colonialism or otherwise. What

are the specific effects of this phase of capitalism on

health (the determinants, dynamics and the status

of health) and Medicine (medical knowledge and

medical profession) ? In general, the contradictions

of capitalism between development of productive

forces in society and the specific capitalist relations

of production get accentuated in the period of

imperialism. Thus the tremendous development of

productive forces in the period of imperialism makes

it more and more unnecessary for ill-health to

continue to prevail. Moreover this development

makes it more and more possible to improve health

in a positive sense. But at the same time, capitalist

relations of production in the imperialist phase do

not allow full utilisation of this possibility. This can

be seen from only a limited improvement in the

provision of food, water, sanitation, safe working

environment, medical care, to all the people in the

world Further, monopoly capitalism affects the

development of productive forces in such a manner

that they instead, foster ill-health by creating malnourishment all over the world (overnourishment

in the imperialist countries, and undernourishment

in the peripheral countries); pollution-creating and

accident-prone working environment, disease creating

medical interventions and so on.

This contradiction is also seen in medicine. On

the one hand there has been a fantastic development

in the medical knowledge leading to increased

possibility of preventing and treating diseases But

on the other hand, the character of medical service

as commodity (though often paid through social

insurance) continues to limit its usefulness and this

increasingly costly commodity is not adequately

available to vast sections of the population who

cannot afford to pay for it. Even the development

of medical knowledge and of the profession itself

June 1985

has been vitiated by the narrow interests of those

in charge of this knowledge and the services. Thus

for example there is comparatively less research on

the health problems of the people in the peripheral

countries; inspite of the rise of preventive medicine,

clinical medicine continues to dominate the scene;

sexism, racism, expertism continues to affect the

character of medicine. Medicine has also played an

increasingly important role as one of the ideological

supports of the ruling class (Ehrenreich. 1 978). For

example, medicine gives "scientific" credibility to

the ideas of the ruling class that diseases are caused

by germs, ignorance, bad habits and "ofcourse"

poverty for which people themselves are to be

blamed and that ill-health can be got rid of if people

become wiser, learn to live clean, give up bad habits

and listen to the advice of the medical experts.

Medical health care programmes have been used

to diffuse class tensions.

Imperialism has developed through two distinct

phases, from 1880's to 1945 is the colonial phase,

wherein

imperialist domination required direct

political rule. The post-war period has seen the

development of a new phase in imperialism with a

distinct change in the structure of imperialist centres

(rise of multinationals, of state intervention and so

on) in the international division of labour and rise of

politically independent bourgeois regimes in peri

pheral countries. We have to analyse health and

medicine in both these phases.

Health in the Imperialist Countries

After 1870, in countries like UK, the incidence

of infectious diseases and of diseases of malnourishment started a secular decline, thanks to the rising

living standards and some public sanitary measures.

But the mortality and morbidity declined much more

slowly among the working classes. A substantial

section of the population was still undernourished.

Thus as late as 1930, a study in UK showed that

out of six categories of population according to

their income, only the two most prosperous had

adequate diet (Doyal and Pennel, 1979). Even in

1970s and 80s some undernourishment continued

in some working class sections of the population.

But gradually food consumption had increased and

this along with better sanitation, housing, and

1

other facilities decreased the morbidity and mortality

due to infectious diseases. It needs to be noted that

the impact of cheap grains and other food products

from colonial countries enabled monopoly capital

to offer concessions to the working class through

an improved food basket, without much rise in the

money wages.

The secular decline in undernourishment in the

imperialist countries was, however, replaced by a

new form of malnourishment, overconsumption,

thanks to the rise of monopoly agri-business especi

ally after the second world war. Production of

concentrated foods stuffed with calories by reducing

its fibre content is the way of increase its value per

unit of weight and the surplus value

(profit)

contained in it. This low fibre, high caloric-density

food led to the problem of constipation and a host

of intestinal diseases related to it on the one hand,

and the diseases due to overweight, cardio-vascular

diseases on the other (Doyal 8- Pennel 1979).

Monopoly capital gave rise to a whole variety

of new industrial products and processes. The

technology to control pollution has,

however,

developed at a much slower rate since capitalists

are primarily interested in profits and not in the

health of the people. As a result, the workers and

people in the neighbourhood were exposed to a

new variety of pollutants, many of them being

carcinogens. A new set of "industrial diseases"

have sprung up.

Monopoly capitalism breeds consumerism. Even

those products which are harmful to health are

pushed onto the consumers through high pressure

salesmanship which is characteristic of monopoly

capitalism.

For example, cigarettes, individual

transport instead of efficient public transport, use

of drugs and medical equipment when not indicated,

and so on.

All the above tendencies are seen in a more

sharpened form in the post-war period. The hazards

of nuclear power reactors is an additional pheno

menon. Increased alienation, psychological stress

and strain has resulted in a higher incidence of

psychiatric disorders as indicated by the fact that

in England, 50 percent of the National Health

Scheme expenditure is now used to

provide

psychiatric care of one kind or another (Doyal &

Pennell, 1979). Massive state intervention in the

economy is the specific feature of post-war capitalism.

This has however not basically changed the process

of social production of ill-health; state intervention

has not been able to control the process of

2

overnourishment, pollution, accidents and psychol

ogical stresses, generated by the incessant drive

of the capitalist class for capital accumulation.

Two imperialist world wars figure as two dark

patches in this otherwise not so happy scenario

Millions and millions perished, crores got injured,

maimed, uprooted. Undernourishment, infections

raised their heads once again. These and other

effects turned the clock by decades.

Health in Peripheral Countries

What has been the effect of imperialism on the

health of the people in the peripheral countries ?

The deleterious effect has been manifold. Wars of

colonial conquest and inter-imperialist rivalry left

many natives dead, injured and maimed. The ravages

of war. the decline in availability of food, social

disruption also took their toll in health.

lhe impact of the policies of the colonial masters

have been studied by some researchers. Study of

Africa offers a typical example (Turshen 1977,

Doyal with Pennel 1979). Alongwith the conquest

by western imperialists came a host of infectious

diseases carried by the invaders from the pool of

infection in Western Europe (Doyal with Pennel,

1979) The imposition of high taxes in cash and

commercialisation of agriculture led to widespread

poverty and reduction of availability of food;

the migrant labour system, plantations, and the

filthy, newly-industrialised towns led to epidemics,

premature deaths, venereal diseases and alcoholism.

The extreme degree of exploitation with scant regard

to the health of the workers in the cities gave rise to

a high incidence of industrial diseases (Eiling 1981)

and high incidence of infectious diseases. In the

rural areas, indiscriminate tampering with the local

environment led to epidemics of sleeping sickness,

malaria and other diseases.

In the post colonial period, inspite of the faster

tempo of the development of productive forces in

the newly politically independent states the living

conditions of the labouring people did not improve,

except for a section of the working class in the

cities. Eradication of plague, small-pox; decline in

cholera, malaria (in other words, those problems

which are primarily amenable to technological soluti

ons) have increased the average longevity. But there

are medico-social and new health problems begging

solutions. Those polluting industries which cannot

now be tolerated in the West due to increased

popular resistance to pollution have been exported

Socialist Health Review

to the peripheral countries. Newly cheated irrigation

systems have led to malaria, filaria and Japanese

encephalitis in certain parts of India (PPST Bulletin,

1984). Unplanned use of pesticides in the strategy

of green revolution has increased the problem of

mosquito resistance to D.D.T. Dams have increased

the incidence of bilharziasis in places like Egypt. A

series of wars amongst peripheral countries have

benefited the imperialists at the expense of the

health of the people.

Concentration of world food production in the

imperialist countries after the second world war and

the dependence of peripheral countries on food

imports from abroad has converted the food situation

into a political issue. The sudden withdrawal of the

US food ''aid'' component in the seventies led to

wide spread hunger, death, malnourishment in

Sahel, Bangladesh and elsewhere. The health of the

people in those countries which are now dependent

on food imports is now at the mercy of the imperia

lists.

Medicine Under Imperialism

What have been the characteristics of Medicine

in the period of imperialism ? It is only after the

1870s that clinical medicine acquired some solid

scientific formulation. All the branches of scientific

clinical medicine have grown very rapidly during the

last 100 years. But at the same time, medicine

became more and more synonymous with clinical

medicine since the character of medical services

remained primarily in the form of sale and purchase

between individual doctor and the patient. Though

the sanitary and social reforms were almost solely

responsible for the improvement in the health status

of the population, clinical medicine and the "germ

theory of disease" usurped the pride of place in the

ideology of medicine since the vested interests of the

clinicians demanded this. With the establishment of

scientific clinical medicine a final, decisive onslaught

on the traditional medical system as well as homoeo

pathic system was made through the famous

Flexner report in the US which argued for allowing

only "scientific medicine "(meaning clinical medicine

with all the limitations imposed by the commercial

professionalism of male doctors) to

continue.

Scientific clinical medicine, however, arrived too

late on the European scene since most of the

infectious diseases had already declined substan

tially and medicine had hardly anything to offer on

the new health problems. The post-war period saw

a new explosion of scientific knowledge. In the

absence of a proper social perspective, and a

conducive structure of medical profession, this

June 1985

new knowledge led the ideology of supcrspecialisation and expertism.

The discipline of "public health" in the mid

nineteenth centrury grew into a modern science of

Preventive and Social Medicine (PSM) and still

further into Community Medicine in the twentieth

century. But firstly this all important approach has

been relegated to secondary importance by the

medical-industrial complex. Secondly, the established

discipline of PSM has neglected or rejected the

Marxian approach, is informed by bourgeois soci

ology and hence it has hardly any correct under

standing of the relation between health and the

process of capitalist development, of the changing

balance of class forces. Its scientific insights are

marred by its bourgeois paradigm/framework and

hence cannot challenge bourgeois social order. Nay

more — it tends to create illusions that ill-health can

be eliminated through technical interventions applied

on a social scale. Through concepts like "tropical

diseases", "diseases of industrialisation",

PSM

naturalises the cause of diseases which are primarily

of social origin. It has thus a kind of fetishistic

understanding of the diseases and hence has

become a part of bourgeois ideology.

The specific effect of monopoly capitalism has

been the rise of monopoly medical industrial

complex. The monopoly drug corporations, medical

equipment corporations and health insurance

corporations have joined hands together (with the

doctors acting as accomplices) to exploit the people,

to breed consumerism and help keep the labour

force docile and productive. Some medical insurance

companies like Metropolitan Life, Providential have

grown larger than General Motors and Standard

Oil. Unncessary medical interventions at each stage

of life; ("from womb to tomb") this medicalisation

of life (lllich 1976) is a specific feature of this stage

of capitalism.

Special mention needs to be made of the drug

companies. The explosion of antibiotics and other

"wonder" drugs after the second imperialist world

war is hailed as one of the greatest achievements of

n odern medicine. But these drugs which can con

tribute a great deal to relieve pain and sufferings, are

not available to the poor. Secondly, an illusion is

being created that medicine can solve the healthy

problems of society with the help of these "wonder"

drugs. The potential created by modern sciences

like chemistry and pharmacology is being used to

exploit people and create illusions. There is plenty

of literature available on this issue.

3

Thus the heightened capacity of medicine in

the period of monopoly capitalism has not only been

limitedly used, but the capacity itself has been

affected by monopoly capital.

Medicine and Imperialist Domination

What has been the role of Medicine in the

imperialist domination over the peripheral countries?

In the colonial peiiod, medicine helped the conquest

of colonies. Some of the infectious diseases like

yellow fever and malaria, took a heavy toll of the

imperialist army and hence made it impossible for

the army to win territories. Medicine solved this

problem by controlling these diseases (Brown 1978,

Doyal and Pennell 1979). But, those diseases which

exclusively affected the natives were not controlled

in this period. Secondly, effective curative services

offered by missionary dispensaries created a good

impression on the natives; and distracted their

attention from the ill effects of colonialism. In the

words of the then president of the Rockfeller Found

ation, "Dispensaries and Physicians have of late

been peacefully penetrating areas of Phillipines

Islands and demonstrating the fact that for the

purpose of placating primitive and suspicious

peoples, medicine has advantages over machine

guns." (Brown 1978).

Later, the imperialists initiated health progra

mmes for the natives to improve their health and

thereby their productivity. Increased productivity

meant increased profits for imperialists. For example,

the Rockfeller Foundation programme to control

hookworm infestation in Latin America (Brown 1 978).

Such health-programmes also offered them opport

unities to export drugs and equipment. Problems

like tuberculosis, leprosy, venereal diseases cannot

however, be eradicated by such techniques of social

engineering because they are much more deeply

rooted in the social structure of peripheral capitalist

countries. Colonialism has also led to the suppression

of indigenous systems of medicine.

In the post-colonial period, it is well known as

to how the imperialist domination in the field of

medicine over politically independent countries

continues in an indirect form through the multinati

onal drug companies, through population control

programmes and other 'health programmes". The

role of western dominated medical education is

also important. Western dominated medical education

in peripheral countries produces doctors suited to

work in imperialist countries. This enables imperialist

countries to import medical graduates from peripheral

countries and save money which would have

4

otherwise been spent on training doctors in their own

country. This "brain drain" is also a financial drain

since peripheral countries spend so much on training

these doctors here. Moreover, the illusion that

health problems of your society can be solved

through medical interventions carried with the help

of ' superior and benevolent" west, the ideology of

medical expertism percolates through this type of

medical education.

The period of rapid growth of peripheral

capitalist societies after political independence came

to an end in the late sixties. As a part of its response

to this crisis, the ruling class is changing its strategy

of medical care. The cost of medical care is sought

to be reduced through the scheme of village health

workers. New innovations in the management of

health problems are being used to create illusions

under the slogan of "Health for all by 2000 AD".

The talk about "indigenous" system being made

more suitable than "Western medicine" needs to be

understood in this context. There’s hardly an

adequate attempt to really find out and develop the

useful, rational aspect of indigenous systems of

medicine. The continued neglect of these systems

shows that the hollow praise bestowed on it is

only a part of the new strategy of dumping responsi

bility onto the people for their health.

A struggle to create a healthier society and an

appropriate system of medical care cannot be

separated from the struggle against imperialism. In

this struggle, the aim cannot only be taking over

the existing productive forces, the existing medical

system and using it in the people's interests How

can people in a socialist society be healthy if they

consume the same amount and type of food as is

being done in the US today or get their electricity

from nuclear reactors ? Likewise imperialism has

also vitiated the science of Medicine. How exactly

and to what extent this has happened is a matter of

further study. A word of caution is in order here.

Let us not fall into the opposite pitfall of rejecting

the relevant scientific advances made by medicine in

capitalism. One cannot talk in terms of modern

medicine as such and reject it. Rather its a question

of grasping the rational kernel of existing medicine

and developing it further Otherwise, we would

throw away the baby with the bath water.

anant phadke

References:

Brown E, Public health in imperialism: Early Rockfeller Programmes

at home and abroad, in Ehrenreich John (Ed) (see below).

Doyal Lesely with Pennel Imogen Political Economy of Health,

Pluto Press. London, 1970.

Socialist Health Review

References

INVITED :

Ehrenreich John (Ed), The Cultural Crisis of Modern Medicine

Monthly Review Press, New York-London, 1978

Eiling,

Ray H.

"Industrialisation

and Occupational

Health in

Underdeveloped Countfies", in Navarro Vicente (Ed).

Imperialism Health and Medicine, Pluto Press, London, 1981.

Illich, Ivan, Medical Nemesis. Pelican, 1976.

Navarro Vicente, Class Struggle, the State and Medicine,

Chapter-VIII, State intervention in NH , Martin Robertson,

Oxford, 1981.

Turshen Meredeth, "The impact of Colonia.ism on Health and

Health Service in Tanzania", International Journal of Health

Services, Vol 7, No. 1, 1977.

Waitzkin, Howard, "A Marxist View of Medical Care". Socialist

Health Review, Vol. I, No. 1,

Bombay-1984.

Author's address :

Requests for SHR First Issue

It's not really a collector's item, but

we do have queries and requests pending

for the inaugural issue now out of print I

We cannot, however reprint the issue unless

we have orders for a sufficient number. If

you would like a copy please write to us

urgently. If we receive orders for more than

200 copies we will be able to supply copies

at Rs. 10 each. If not, we can get the entire

issue photocopied at Rs. 25 per issue. Please

let us know if you would like a copy at

this latter rate or only if it is available at

Rs. 10 each.

50, LIC Quarters

University Road

PUNE 411 016

Centre for Education and

Documentation

In This Issue

Radhika Ramasubban

examines the

colonial

health policy in India and traces its legacy to the

present public health system LMeera Chatterjee high

lights the wide ranging implications of a new scheme

formulated by the American Association of Physicians

of Indian Origin in collaboration with the IMA to

transfer high technology in medicine to India.

Warren Salmon's reprinted article deals with the

increasing interest and involvement of large US

corporations in health issues in America and the

emerging class stand which will eventually restru

cture the health sector under monopoly control.

The article on racism and health in the US, a revealing

glimpse at health care in a country which spends

one billion a day on such care is by Bindu Desai a

neurologist working in the Cooke Country Hospital

in Chicago. The Bhopal Update which Is likely to be a

regular feature in future issues is a resumme of

health issues, health efforts and on-going medical

debates concerning the Bhopal disaster by Padma

Prakash. We feature a review article on John

Braithwaite's explosive new book on the drug,

industry. Corporate Crimes in the Pharmaceutical Industry

by Ravi Duggal. This book is a must for all con

cerned people — if one can afford the price I

SORRY :

Due to oversight the box requesting for

subscription renewals (1:4,p.144) quotes the new

subscription rates as Rs. 24. Here's some good

news! The subscription rate remains at Rs. 20

(for four issues). We have increased the price

of individual copies to Rs. 6. Do send your

renewals and PLEASE wri,te

your name and

address on the counterfoil of MOs --- we would

prefer cheques or demand drafts drawn in favour

of Socialist Health Review.

June 1985

The CED collects, collates, researches

and disseminates information on a wide

range of subjects of social importance.

The following publications are available

with us :

c/

1.

2.

3.

(CED Health Cell Feature)

Abuse of Female Hormone Drug — No. 1

Bleeding for Profit

— No. 2

Inj ectables: Immaculate Contraception ?

— No. 3

4 Health and the Work-place

— No. 4

5.

Asbestos -- The Dust that Kills

6.

Health Sans Multinationals : The Bangladesh

Crusade

7. Pills for All

8. ORT and the Credibility Gap

1.

Aspects of the

India

Drug

Industry

in

— Mukarram Bha gat

2.

Operation Flood : Development of

Dependence

— CED Research Team

3.

Land Degradations : Indian’s Silent

Crisis

— Mukarram Bhagat

For further details contact:

CED« 3 Suleman Chambers, 4 Battery Street.

Behind Regal Cinema, Bombay 400 039.

Tel : 202 0019

(Open 11 a.m to 7 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday)

5

THE COLONIAL LEGACY AND THE PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM IN INDIA

radhika ramasubban

Colonial health policy in India never really came to grips with the problem of public health. Through the

evolution of a ‘colonial mode of health care , the enclave sector — the army and the European civilian

population------ kept pace with the metropolitan developments in sanitary and medical sciences while attempts

to introduce epidemic control and public health measures remained abortive. In the last years of the nineteenth

century when the situation afforded a compelling basis for a far-reaching pubhc health policy, the colonial

government found an escape route in the new research possibilities. The contradictions of the health system in

India arise from its historical legacies. This article traces the various strands which evolved during the period

of colonial rule and the manner in which they continue to shape the present public health system.

This article is an abridged version of an earlier research report by the author. ‘ Public Health and Medical

Research in India. Their Origins under the Impact of Colonial Policy" (SAREC, 1982).

f | 1 he task of tackling widespread disease and of

raising the health status of the population requ

ires coming to grips with the conditions which cause

debility and disease. The three main instruments for

such a strategy in the Indian context are thorough

going public health measures, improvements in the

standard of living of the population through raising

incomes and providing employment and making

the health services available to those in need.

Obviously, the health system alone cannot cooe

with all these challenges and in a general sense the

contradictions of the Indian health system are a

reflection of the contradictions of the development

process itself. More specifically, the contradictions

of the health system in India arise from its historical

legacies and the overall framework which guides

its nature and functioning.

India missed going through the

period of

sanitary reform which swept through most of

Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Colonial health policy never really came to grips

with the problem of public health in India, whereas

through a policy of segregation and what evolved

into a 'colonial mode of health care', the enclave

sector — the army and the European civilian

population — kept pace with metropolitan develop

ments in sanitary and medical science. In the

absence of general public health measures, epide

mics of small pox, cholera, plague and influenza

continued to recur among the general population.

Some attempts made in the first quarter of the 20th

century to evolve epidemic control measures

remained abortive due to the administrative disrup

tions caused by the two world wars and the pre

occupation with the health of the army, particularly

the control of malaria in the eastern theatre of the

second world war.

6

The independent Indian State, although it

recognised public health as one of its main con

cerns, lacked the commitment to carry through a

public health revolution. Seen in the wider historical

perspective, the huge expenditure that public health

measures require have been incurred by the State in

the western countries for ensuring a steady supply

of the labour force and for raising its productivity.

The capitalist path of development launched in

India has remained distorted and slow. It could

neither impart dynamism to the public health system

as it had very little demands to make, nor could the

productive forces develop to the extent which

would improve the health status of the population

by meeting their nutritional and other basic needsAbout half the Indian population is still living below

the minimum nutritional standard for meeting the

energy requirements of the body and the incidence

of diseases preventible through public health

measures dominates the disease profile.

The problem with undertaking far reaching

public health measures such as protected and

adequate

water supply, sewerage systems and

better housing and nutrition is that it requires

massive public

expenditure. The independent

Indian State, however, has not been able to meet

these requirements (Ramasubban, 1984). It has,

instead, settled for softer options which are essent

ially a continuation of the colonial tradition. The

attempt here will be to trace the various strands

that evolved during the period of colonial rule and

the manner in which they continue to shape the

present public health system.

The Evolution of Colonial Health Policy

The main factors which shaped colonial health

policy in India were its concern for the troops and

the European civil official population. The response

Socialist Health Review

to this concern underwent a series of stages corres

ponding to the growth of knowledge in England

about the principles of disease causation. The old

climatic theory was that the Indian climate caused

diseases in the abdominal cavity' while that of

Europe caused disease in the 'thoracic cavity'

(Scott, 1939) This gave way to the theory of

miasma, resulting in a policy of segregation and

sanitation which began in the mid-nineteenth

century and continued tnrough until the end of the

century. The result was the evolution of a distinctly

colonial mode of health care. This policy also took

into account statistical patterns of mortality and

simple prediction of eoidemics. The general spread

of epidemics resulted, however, in the mobilisation

of international opinion and the perception of the

Indian population as a secondary source of infection

brought the general population into the ambit of

health policy. But the main concern remained the

army, and therefore, the evolution of colonial

health policy has to be necessarily placed within

the framework of the army. The shift in focus in

England and Western Europe from sanitation to

epidemiology and bacteriology, which began in the

1 880 s and gained revolutionary momentum in the

following decades, had significant implications for

India By the turn of the century, laboratory investi

gations were instituted in the four army commands,

to put army health on modern, scientific principles.

Although the direct link between health and

medical research remained confined within the

framework of the army, the growing interest in and

official patronage for the discipline or tropical

medicine in England integrated India, the largest

natural disease laboratory in the British empire,

into metropolitan scientific activities, and a few

laboratories for research were set up within the

country.

The army, the main instrument of the East

India Company's political

consolidation,

was

primarily composed of Indian soldiers, the European

component being outnumbered by roughly eight to

one (Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909). The high

cost of transporting European soldiers to India and

of invaliding due to sickness, and the time taken in

further recruitment and replacement, were the

major factors responsible for the excessive reliance

on the Indian component.

Mortality, sickness and invaliding in the Euro

pean army was due mainly to four major diseases:

fevers, dysentery and diarrhoea, liver diseases and

epidemic cholera, in that order, all of which, parti

cularly the last-mentioned, assumed virulent form

June 1985

when the troops were on the march. And the troops

were almost constantly on the march in the prevail

ing unsettled state of the country.

As regards the European civil population, a large

section was concentrated in the three Presidency

towns of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, which were

centres of government as well as the major ports.

Here European areas of residence were secluded

from the Indian areas and along with the canton

ments in these towns, were fully self-contained.

By the mid nineteenth century, these areas were

relatively well planned and drained and vaccination

against small pox (the only effective prophylactic

known), among the European civilian residents and

among the residents of the cantonments, was

almost universal

The ^events of 1857 — the 'Indian Mutiny' —

highlighted as never before, the importance of the

British soldier s health and efficiency. Army health

which became the primary concern of colonial health

policy remained an abiding concern as, with the

expansion of the British empire, the army in India

increased in importance as the largest single force

in the empire, and as a key instrument in the security

of Britain's eastern possession The 'Mutiny' of 1857

had highlighted the insecurity of British military

power in India. Reliance had hitherto been placed

on Indian soldiers and they had vastly outnumbered

the European component. Although the majority of

the Indian troops had remained loyal to the Com

pany and the 'Mutiny' had been successfully quelled.

it was decided that the defence of India would

henceforth have to be in British hands, and it was

resolved that the 'British army serving in India'

should form part of the Imperial British army. This

necessitated the transfer in 1858 of the European

troops of the East India Company to the Crown and

a Royal Commission was appointed to work out the

army's reorganisation. It recommended raising the

number of British troops, and that the ratio of Indian

and British soldiers should be of the order of 2 to 1.

The result was a 60 per cent increase in the number

of British troops. (Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909)

The result of the increase in the strength of

British troops was that one-third of all British forces

came to be stationed in India. The problems in

acclimatising such large numbers to Indian condi

tions and ensuring their health, therefore, assumed

importance.

Along with the Indian Mutiny, the Crimean war,

too, played an active role in focusing discussion in

England on the health of the British army. The

7

Crimean experience had shown that mortality among

troops had been due primarily to epidemic ravages

and the insanitary state of barracks and hospitals

rather than to wounds of war. It highlighted the need

to apply the principles of modern sanitary science

currently championed in England by sanitarians like

Chadwick and John Simon, to the army. In 1857, a

Royal Commission was appointed to enquire into

the regulations affecting the sanitary conditions of

the army, the reorganisation of military hospitals and

the treatment of the sick and wounded. The enhanced

strength of the British army in India required a

similar enquiry into Indian conditions, and in 1859,

another Royal Commission was appointed to enquire

into the Sanitary State of the Army in India.

Of the total number of deaths in the period

examined by the Commission, i. e., 1817 to 1857,

only 6 per cent had been due to war. The rest were

caused by four major diseases : fevers, causing

about 40 per cent of all deaths and three-fourths of all

hospital admissions; and dysentery and diarrhoea,

liver diseases and cholera being the other killers.

Fevers, besides the suffering and immediate risk to

life, also had a tendency to relapse dangerously and

affect vital organs, resulting in considerable subse

quent illness, mortality and invaliding among

British troops. At this time 'fevers' was still a general

term for most forms of sickness. Clearly, therefore,

"the main enemy of the British soldier in India was

not the Indian enemy but disease". (Royal Sanitary

Commission Report, 1863).

a)

Sanitary principles and the policy of segre

gation.

The situation, however, was neither unfamiliar

nor irremediable. The old climatic theory had held

that the Indian climate produced diseases distinctly

different from those resulting from the English

climate. Now, the diseases which were fatal to the

British soldier in India were recognised as familiar,

as those which had until recently caused the highest

mortalities in Eng'and, and which had been brought

under control in that country through sanitary

programmes.

The keynote of metropolitan sanitary science,

which grew out of the compulsions of urbanisation

in England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,

was environmental control. The means through

which this was accomplished were mainly town

planning, housing and sanitary engineering. These

measures required administrative and government

institutions embodied in 'local governments', which

were responsible for investigation of local insanitary

8

conditions and their control, and given the force

of legal sanction through public health legislations.

The physical placement of the European popula

tion in India was, as far as possible, based on the

principles of this sanitary science. Using criteria of

soil, water, air and elevation, the Royal Sanitary

Commission on the army in India laid down elabo

rate norms 'or the creation and development of

distinct areas of European

residence, and the

'cantonment', 'civil lines', 'civil station' and 'hill

station', regulated by legislations, developed into a

colonial mode of health care and sanitation based

on the principle of social and physical segregation.

From the time of the Royal Commission's Report of

1863, the location a.id layout of European civil and

military areas were determined by criteria of health

laid down by the prevailing medical scientific

theories of miasma and environmental control rather

than by political and strategic criteria. Most of the

troops were located at 'hill stations' or on elevated

ground In cases where strategic stations were

unhealthy, only small forces were posted there to be

reinforced at short notice. Earlier, the 'native lines',

i e., residential areas of Indian soldiers, had been

left outside the pale of colonial planning and con

struction activity for troops. European fears of

miasma emanating from them had even led to

construction of walls between Indian and European

troop locations to keep the miasma out. The Royal

Sanitary Commission voiced concern for the health

of the Indian troops and recommended that canton

ment planning should also be extended to the 'native

lines'.

b)

Public health machinery :

and disease control

vital statistics

Following the Royal Commission's

Report,

Cantonments Acts, Regulations and Codes were

issued modelled on public health acts in Britain.

While segregation was an effective tool, at least

in the three Presidency townscontact with the native

population was unavoidable. Native servants often

lived in the native areas, and native dealers and

tradesmen serviced the cantonments and civil lines.

Grossly insanitary conditions prevailed in these

large and unplanned urban centres and the native

population could well serve as secondary sources

of infection. An understanding of disease among

them was, therefore, considered essential. In his

despatch to the Government of India the Secretary

of State for India pointed out, "The determination

of the effects of local causes on the mortality of the

Socialist Health Review

native population, besides its intrinsic value in con

nection with the welfare of the people of India,

cannot fail to have an important bearing on the

health of the Europeans resident among them."

Gazette of India, 18G4).

Three Presidency Sanitary Commissions were

set up in 1864. The basis for the functioning of

these Commissions was to be the systematic genera

tion of facts about mortality, epidemics and sanita

tion, which would be embodied in an annual

sanitary report to be submitted io the Government

of India by the Sanitary Commissioner to the Gover

nment of India. This would in turn be summarised

in annual reports presented to parliament on the

progress of sanitary measures in India. This laid the

foundation for a public health machinery, parti

cularly in rhe field of vital statistics and disease

control.

The investigative tradition was an integral part

of the sanitary movement concurrently taking place

in England; in fact, the first stage of the public

health movement was that of governmental investi

gations on grand scale. Regular statistical reports

were also seen as essential to any systematic public

health control and since the establishment of the

office of the Registrar-General of Births, deaths and

Marriages in 1836, the steady accumulation of

statistical evidence had generated a demand for

further research into the causes of epidemic diseases.

(Shryock, 1 948)

In keeping with this tradition, the Government

of India appointed in 1861, the first systematic

enquiry into a major epidemic—the cholera epide

mic of 1861. The facts that it highlighted were

followed up in the annual sanitary reports, which

resulted in a steadily growing volume of statistics

and facts about the disease.

The significance of the 1861 epidemic was

that its impact was not confined to India alone; it

was followed by another epidemic in 1865 which

spread from Egypt across Europe to England.

Cholera had been the most important factor respon

sible for initiating the public health era in Britain in

the early nineteenth century. The 1861 epidemic

provided the final and most powerful spur to sani

tary legislation in England. This was the Sanitary

Act of 1866 embodying the important principle of

compulsion by the central authority if the local

sanitary authority failed in its duty.

This epidemic also gave rise to four international

sanitary conferences participated in by European

June 1985

countries in 1866, 1874. 1875 and 1885. They

devoted their deliberations specitically to this

disease and attempted to work out quarantine

measures acceptable to all participating countries;

systematise existing knowledge about the disease

and identify major questions for further investiga

tion; and, recommend measures for prevention. As

the 1861 epidemic had originated in India, the first

Conference at Constantinople discussed India as a

major topic.

The Constantinople Conference put the Imperial

government into a quandary by pronouncing India

the natural home of cholera. In the absence of any

breakthroughs in know edge about the cause and

mode of infection, the Conference stressed the need

for stricter implementaion of rigorous and lengthy

quarantine both in sea and land movements,

greater cleanliness and disinfection of ships, houses

and merchandise, and care to avoid overcrowding.

The central consensus of the Conference was that

the spread of cholera epidemics was due to rapid

movements of groups of people and their personal

effects, water and food supplies. It pronounced

that in the case of India the movement of pilgrims

and large congregations at fairs and festivals was

the single and ' most powerful of all the causes

which conduce to the development and propagation

of epidemics of cholera". (Cholera Committee

Report, 1867). In the opinion of the Conference

when the pilgrims congregated, the cholera spread

among them and when they dispersed they carried

the contagion with them over long distances. The

Conference recommended elaborate preventive,

sanitary and curative arrangements

at pilgrim

centres and on pilgrim routes.

The international arrangements outlined for

quarantine and the recommendation

proposed

regarding pilgrims, by the Constantinople Confere

nce, were particularly irksome to Great Britain which

had the largest international maritime trade as well

as the most frequent troop and naval movements to

and from its colonies. In the face of stricter quaran

tine restrictions imposed by the Constantinople

Conference and the international pressure to control

cholera within India and prevent its spread there

from, Great Britain responded by instituting its own

investigations into the authenticity of a quarantine

policy, i. e., whether it was local conditions of soil,

air and water rather than contagion carried through

people and their effects which caused the spread of

epidemics, and whether there was a possibility of

coping with cholera through

effecting sanitary

9

improvements rather than quarantine. Professional

medical opinion in England also provided support

to such a move and a special enquiry came to be

sanctioned by the Secretaries of State for War and

India in:o the mode of origin and transmission of

cholera

While the results of the scientific investigation

were being awaited, practical sanitary measures

were intensified in relation to all cantonments,

smaller military stations, troops on the march, jails,

hospitals and seaport towns. By 1872 local medical

officers in all the various military stations were

doing simple qualitative analysis of water. The

prohibitions upon soldieis going into the Indian

cities or cholera affected areas were more strictly

enforced and "sanitary cordons" (suggested by the

Constantinople Conference) were erected around

cantonments to prevent persons residing in nearby

villages and localities and those suspected of carry

ing cholera, from entering the area. Infected cases

in cantonments were isolated and barracks, jails and

hospitals fumigated.

Hitherto, troops on the march had been the

most vulnerable to cholera attacks. The new

sanitary rules governing the marches also included

rules regarding railway travel, such as provision of

good drinking water and wholesome meals at halting

stations, isolation of thetroops from the native towns

and bazaars en route and at destination, thirtyminute stops every four hours and travel for not

more than twelve hours at a stretch.

Systematic statistics about cholera were accu

mulating with the regular publication of annual

sanitary reports. These statistics pointed to direct

personal contact as an extremely unlikely cause of

infection Nor was land quarantine doing much

good; and nor did cholera appear to travel along

highways and major lines of communication. As

regards sea travel, however, stricter control was

instituted, mainly in deference to international

pressure.

Until the end of the 1880's, cholera of all dise

ases pressed most heavily on British soldiers in

India, being the most important cause of mortality

although not adding significantly to the sickness

rates. The investigations of Lewis and Cunningham,

by going into the question of sub-soil water levels,

had launched on a relatively fruitless line of enquiry

which failed to produce conclusive evidence on the

cause of cholera. But although their study (Lewis

and Cunningham, 1876) made little impact on the

10

control of cholera, it was valuable in that it stressed

the importance of looking elsewhere than into,

contagion through personal contact. But by the

period 1870-79, the combined effect of sanitary

measures and other reforms had brought average

mortality due to all diseases among European troops

down to 19.34 per 1030 of strength, of which cho

lera accounted for an average of 3.22 (calculated

from Annual Sanitary Report for relevant years). By

tne end of the century the severity of cholera came

down even further and after 1900 rarely one person

in 10,000 among the European troops came down

with cholera (Annual Sanitary Reports, 1899 1929).

The year 1883 was one of the major landmarks

in scientific investigation into disease causation.

A German Commission led by Robert Koch dis

covered the Cholera 'Comma' Bacillus in Egypt and

visited Calcutta in the same year to confirm the

discovery. Koch's discovery was a significant con

tribution to the germ theory of disease causation

which had emerged in Western Europe in the 1860's

and studies like his and those by Pasteur, which

linked a specific organism with a specific disease,

helped to firmly establish the theory in the 1870 s

and 1880's. This modern scientific revolution in

medicine challenged and ultimately triumphed over

the earlier miasmatic theories.

c)

General Population

The Constantinople Conference's declaration of

India as the source of epidemics, its condemnation

of the British government for failing to control these

epidemics and the latter's own recognition that the

Indian population constituted a secondary source of

infection, provided the compulsion for broadening

the scope of health policy and include the general

population in its purview.

In keeping with the theory of contagion, the

places of pilgrimage and pilgrim routes became the

starling point of health policy in relation to the

general population, and the formal motions of

attending to the problem were gone

through.

Committees were appointed and reports prepared.

But when it came to giving a concrete course to

the policy, however, the government's attitude

remained evasive.

While the suggestions of the Constantinople

Conference regarding the desirability of sanitary

precautions in relation to large groups of people

on the move was quickly given effect in the

case of troops on the march. In order to prevent

Socialist Health Review

the outbreak of epidemics among them, the ques

tion of epidemics at the pilgrim centres was treated

as a puzzle, and various other considerations such

as finance, religion and race clouded the issue.

However, at the 1867 Kumbh Mela, the govern

ment as a test case made some ad hoc sanitary and

hospital arrangements. These had proved success

ful in curbing cholera on the fair grounds. But no

sooner had the pilgrims dispersed, than the cholera

that they carried spread in the regions through

which they passed and in their ultimate destinations

even as for as 700 miles away. This seemed to

imply that not sanitation alone but land quarantine

measures were required. The official position was

to see this as an intractable problem, for quarantine

was not considered to be a feasible measure in the

case of people who would be dispersing over a

large area. The response of the Government of

India was to rest content with the prohibition of

pilgrims from entering military stations or even

their neighbourhood.

In fact, the whole question of pilgrims taking

cholera back with them to their towns and villages

raised the uncomfortable issue of an extensive

public health machinery for the general population

on a continuing basis, which would be the only

countervailing force against epidemic

cholera

emanating from pilgrim

movements and con

gregations.

But sanitary reforms were expensive and

unremunerative. The MacKenzie Committee appoi

nted to go into the pilgrim question recomm

ended

that the

government should under

take the responsibility for at least a few such

measures at pilgrim centres. If public health

measures for the general population at large could

not be adopted, at least the enforcement of con

servancy measures at fairs and pilgrim centres and

demonstration by the government thereby of the

desirability of sanitation would act as an incentive

for the general population to voluntarily adopt the

modern sanitary principles in townsand villages.

The Committee argued that such a step was also in

the interests of the European population. But the

government rejected the idea of expenditure on

conservancy measures and sanitary

police at

pilgrim centres, and policy floundered on the issue

of whether pilgrims should be made to pay for

sanitary

arrangement through a sanitary tax.

(MacKenzie Committee Report, 1868)

Progress on sanitary reforms concerning the

general population was blocked on the ground that

June 1985

no measures could be enforced, as any element of

compulsion would offend the people's religious

sensibilities and be construed as interference in

their customs. The bogey of interference in the

religion and customs of the people was not new,

but was more self consciously applied after the

'Mutiny.' Eighteenth century East India Company

officials many of whom recognised in India a

superior civilisation, had been replaced in the early

nineteenth century by administrators who saw their

mission as 'civilizing' and 'modernising' Indian

society. Indian socie'y was seen as a tabula rasa

waiting to be recast in the Western mould. The

civilising influence would be Western social and

economic institutions and Western religion, i e.,

Christianity. After the 'Mutiny', however, the enth

usiasm for remaking Indian society declined The

climatic and socio-religious theories gave way to

theories of racial exclusiveness, as Britain establi

shed itself as the supreme governing power and as

the European establishment in the country perfected

the mechanisms of physical and social segregation.

Indians now came to be seen as a distinctly inferior

race incapable of appreciating or successfully adop

ting British habits and institutions. That interference

in social and religious practices would offend Indian

sensibilities, was only the rhetoric, offered for

government inaction to bring into force a public

health machinery and sanitary reforms in India

along modern lines.

As far as the people themselves were concerned,

the MacKenzie Committee which sought Indian

opinion on the matter of sanitary measures at pilg

rim centres, found that the people were willing to

submit to any measures calculated to promote their

health. There was also evidence that the arrange

ments at Hardwar in 1867 had suitably impressed

the pilgrims.

While the government persisted in its evasive

ness the railway companies, realising that pilgrims

were good business, were cashing in on the age-old

enthusiasm of Indians for undertaking pilgrimages.

A large number of pilgrim centres existed across the

country, and it was the aspiration of every Indian

to visit at least one of these centres in his lifetime.

There were also certain specific religious festivals

which drew large numbers at certain times of the

year. In the old days the journey used to be lonq

and arduous and done on foot or by animal carriage.

There were accepted pilgrim routes and halting

places at villages en route where accommodation

and food or facilities for cooking were available

H

Most of these were free and maintained by philanth

ropists.

The introduction of railways offered a universal

opportunity for undertaking pilgrimages and the

possibility of a single person perhaps undertaking

several in his lifetime, and railway travel for this pur

pose became extremely popular. The railway compa

nies responded quickly to this source of profit, offer

ing return tickets and half fares for children. But the

facilities were appalling. Pilgrims were stuffed into

dirty goods wagons with no ventilation lighting,

drinking water and sanitary arrangements on board.

The doors used to be fastened from the outside and

not opened for hours at a stretch, as allowing the

pilgrims to climb in and out at stations en route

would cause delays. The few third class carriages

allotted for pilgrims were impossibly overcrowded.

And for a long time no provision existed for clean

accommodation, drinking water or meals at halting

stations. Death from suffocation and disease in the

goods wagons and cholera epidemics on railway

journeys and at pilgrim centres became more frequ

ent as the pilgrim traffic increased and the rapid

communications spread disease more rapidly. Pilgr

ims now poured into holy places in much larger

numbers than these places had been provided to

cope with and problems of sanitation were further

aggravated. Even as cholera had almost disappeared

among the troops, epidemics continued to rage

among the general population. The Committee

which investigated the matter recommended that

government move in to check the worst abuses of

railway travel and regulate the conditions of pilgrim

movements, conveying pilgrims in closed air-tight

wagons meant for goods should be discouraged,

eating houses at railway stations be licensed, and

provisions made for drinking water and toilets at

stations.

The salient feature of the pilgrim movement

now was that the congregations of people did not

take place only at certain times of the year; rather,

the pilgrim centres had a constant flow of people

round the year. Ad hoc measures, therefore, could

no longer be considered an effective solution to the

epidemic problem.

The last decade of the nineteenth century was

a period of significant landmarks in determining the

course of the colonial health policy. The two gove

rning landmarks were the plague epidemic which

broke out in Bombay in 1896 and the discovery in

India by Ronald Ross of the Indian Medical Service

of the mode of transmission in malaria in 1897. The

12

responses to these two events reflected the growing

complexity of Britain's international position and

rise of British imperialism, Britain's perception of

India's place within the Empire the internal changes

effected by the Government of India to adapt India

to its new role, and the contradictions within the

Government of India's policy.

The neglect of public health measures among

the general population; accompanied by

the

intensification of trade and commerce and the

growth of population in the seaport towns; as well

as the increasing impoverishment in the rural areas

and the flow of migrants into the towns and cities

in search of work; came to a head when the plague

epidemic which broke out in Bombay in 1895 was

followed by successive epidemics which spread

the disease to large parts of the country, and which

by 1918 had taken a toll of almost 10.5 million

lives. What was striking was that all the plague

deaths occurred only among the Indian population.

Plague was known to have been endemic to

Europe since early times but by the end of the

seventeenth century it had completely disappeared.

When the plague broke out in Bombay, the spread

of the epidemic within the city and to other parts of

the country combined with the movements of desti

tute people out of the rural areas and into the

towns due to the widespread famine, threw the

authorities into a flurry of confused activity. The

Bombay plague committee was set up on a crash

basis for the period 1897-1898. In the absence of

any scientific knowledge about what caused the

disease it was treated as contagious. House to

house searches were conducted with the aid of

police cordons to register deaths and remove sick

persons for isolation, dilapidated houses were

vacated and disinfected and the inmates removed to

camps, rural migrants to the city were detained in

camps to prevent disease conditions exacerbating in

the city, and at the railway stations passengers and

their baggage were disinfected.

But these ad hoc measures were no solution to

a situation which was rapidly getting out of hand.

The single most important cause of bubonic plague

was insanitation which created the conditions for a

large number of rats to live in and around human

dwellings, and poorly constructed, dark, ill-venti

lated houses where rat fleas could take refuse away

from air and sunlight which were their most effec

tive killers. As long as drainage, sewerage and

planned housing remained severally defective or

non-existent, the plague, once introduced, would

Socialist Health Review

continue to remain endemic. The transmission of

the disease from the rat to man through the rat flea

and not through human contact as in pneumonic

plague (familiar to England as the 'Black Death’)

rendered isolation and detention camps useless.

The plague epidemic could have provided a

take-off point for a more far reaching public health

policy. True, the unreformed sanitary conditions

among the general population exacerbated by the

impact of colonial economic policies and natural

calamities had worsened public health conditions.

While the urban centres were undergoing a hapha

zard development, the countryside was becoming

increasingly impoverished. But the result of the

plague innoculation drives, the first major attempt

at epidemic control, was the growing awareness of

and desire for sanitary reform among the general

population Representations were made by Indians

requesting the government to take the initiative in

maintaining the struggle against the plague, and in

widening the scope of sanitary reform. The need to

create an effective public health machinery had

also been unequivocally stressed by a body of

expert scientific opinion from England who, in

elucidating the mode of transmission of bubonic

plague, had pointed to insanitation as the single

most important cause, and had even drawn up a

tentative scheme for public health administration.

The scheme remained unimplemented by the

Government of India, and once again, the offi

cial response was the rhetoric of caution in qui

ckening the pace of sanitary reform for fear of

pressurising public opinion. In fact, as far as

the government was concerned, the living condi

tions of the general population were "beyond

the influence of sanitary effort..." (Annual Sanit

ary Report, 1900-01). Articulated public health

policy was growing into one of leavingthe Indians

to their own efforts.

The plague epidemic and Ronald Ross' malaria

breakthrough had been the thereshold for the

developments between 1900 and 1935. A step

could have been taken in the

direction of

focusing policy on evolving a public health machi

nery. However, the possibility of research also

presented itself at this moment and the colonial

government for its own reasons chose the latter

option.

In England, the public health system had

come into its own by the time of the scientific

advancements in medicine, and the new stream

June 1985

of scientific ideas while they revolutionised health

care, did not replace the public health machinery

which continued to enjoy a relative autonomy. In

India, the metropolitan sanitary science was addre

ssed only to the colonial population resulting in

what we had earlier referred to as a colonial mode

of health care. It, however, had a demonstration

effect on the general population, which began to

see its potential in the last few years of the nineteenth

century.

Public opinion was beginning to form the

basis for a potential sanitary movement in India.

The Indian elite showed eagerness to lay the

foundations in the country for the growth of

medical science in which Indians could participate

and benefit therefrom. The various international

sanitary

coneferences and the British Plague

Commission were an added source of pressure

upon the colonial government to pay attention

to public health.'

Just at a time when the situation afforded

the compelling basis for a far-reaching public health

policy, the colonial government found an escape route

in the new research possibilities, and public health

policy as in the past remained sporadic and ad

hoc. Tne Sanitary Department was most unpopular

with the colonial medical bureaucracy and by

the time sanitation and public health were made

a provincial subject in 1919, the Sanitary Depart

ment already lacking a coherent policy or substantial

financial provision, was depleted of most of its

supervisory personnel. In the remaining decades of

colonial rule nothing occurred to change this pattern.

No single authority responsible for the efficiency of

health measures throughout India came to exist,

and nor was there any single Public Health Act as

in England. The only concern of the Imperial

Government was port quarantine. Vital statistics

remained very defective due to the absence of a wide

deployment of medical personnel.

With the superceding of the era of active

sanitary reform by an era of emerging professionalisation in medicine in England, the consequ

ences for Indian public health in terms of the los*

historical possibilities were far-reaching. ^Medical

education had been

initiated

in

the Indian

Presidency towns by the mid-nineteenth century,

mainly to train hospital assistants for military and

civil hospitals. The medical colleges also received a

steady influx of Indians right from their inceptionWhen the bacteriological advances of the late

T3

nineteenth century put curative medicine on a

scientific basis and led to its increasing professionalisation this served as an argument for colonial

policy to encourage the expansion of the private

medical profession (ooth European and Indian)

— for a few medical colleges were a cheaper

alternative to expending goverernment resources

on sanitary reforms for the general population.

The growth of preventive and social medicine was

irremediably pre-empted and the rising medical

profession made its spoils from the ever expanding

disease market.

The Present Health System

and its Contradictions

The 'functional approach', which sees health

as 'fitness' to undertake one's work as a produc

tive member of society, and ill health as the

result of malfunctioning of one particular part of

the body which can be corrected through medical

interventions, arose out of the conditions of

maturing capitalist development in Europe in the

19th century, and achieved final consolidation

with the development of the germ theory in the

last two decades of the 19th century. (Doyal, 1979)

But the functional approach could come into its

own mainly on the strength of effective declines

in mortality and morbidity due to the control of

infectious diseases brought about by the State in

the pre-germ theory era thiough effective public

health measures which stressed the predominantly

environmental — 'filth' or miasma' — causes of

disease and death.

In India this functional approach, carried over

from the experiments during the colonial rule, has

remained partial and ineffective. In those spheres

where the regular supply of skilled and physically

fit manpower has been crucial, as for instance the

army and capital - and technology-intensive sectors

of the economy, the 'colonial mode has been

the preferred pattern : social and physical segre

gation of employees

and

their families into

exclusive residential areas or housing colonies

with clean and sanitary environments, access to

subsidised and good quality-medical and clinical

care, educational facilities, etc. To take care of

the possibility that the rampant infection, parti

cularly in the poorer urban areas given their

haphazard growth and insanitary environments

might break out in epidemic form, vaccinations,

hospitals and selective measures for improving

drinking water and sewage disposal have been

resorted to. Otherwise the rural areas and the

14

urban slums where most of the population lives,

remain by and large untouched by theexisting health

system. For the health system to reach them in any

significant way, within the functional approach,

requires heavy doses of public expenditure. In the

absence of effective preventive measures, the indivi

dual’s own approach towards health care has been

that of coping with repeated attacks of infectious

diseases only through medical interventions. The

private consumption expenditure on medical and

health care as estimated from the 28th round of

the NSS in 1973/74 was three times the public

expenditure on this activity (Lakdawala, 1978)

Since effecting public health measures through

environmental sanitation and provision of housing

and safe drinking water is an expensive proposition,

the Indian State, helped by advancing medical tech

nology and international assistance, resorted to the

easy alternative of tackling communicable diseases

through vertical programmes that involved the use

of known and tested technology such as vaccina

tion and DDT spraying in the case of small pox and

malaria respectively, and isolation and treatment as

in the case of the other major communicable diseases

such as TB and ’eprosy. With the exception of

vaccination and revaccination against small pox, all

the other known medical interventions presupposed

the existence of effective public health measures

and in a situation where the latter condition did not

exist, could be expected to have only limited

efficacy.

Next to small pox, the vertical programmes

showed some signs of success in the case of malaria,

supported through international aid for the import

of powerful insecticides and drugs which had proved

successful in malaria control in the second world

war. Between 1953 when the National Malaria

Control Programme started (it was stepped up to

'Eradication' in 1958) and 1965, the incidence

of the disease was brought down from around

100 million cases and 1 million deaths to 1

million cases and no reported deaths (Gol, 1977 64

Table 51). These achievements, as Cassen (1978:86)

has argued, must surely be recognised as the single

most important cause for the steep decline in

in mortality that India has been able to effect

after independence. The 1965 record, however,

regressed soon after, and the incidence of malaria