RF_COM_H_5_PART_1_SUDHA..pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

H 5.4

RF_COM_H_5_PART_1_SUDHA.

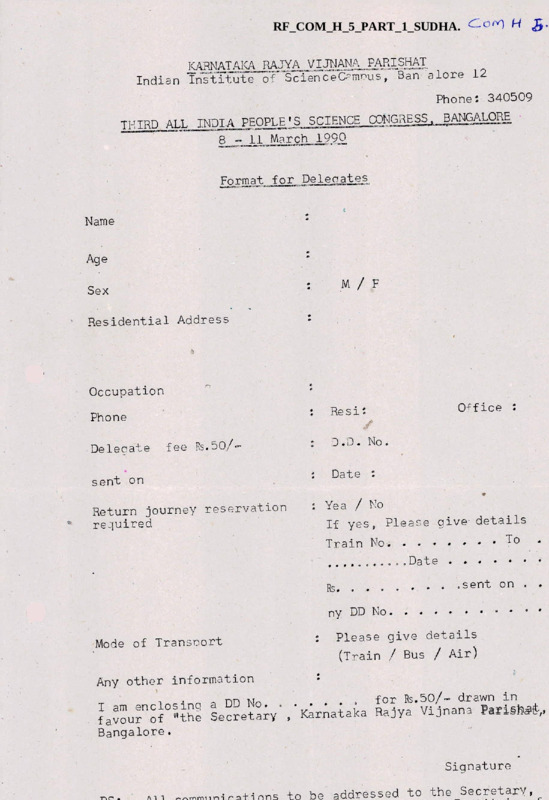

KARNATAKA RAJYA VIJ1JANA^.£ARISHAT

Indian Institute of ScienceCamnus, Ban a lore 12

Phone: 340509

BANGALORE

THIRD^ALLL INDIA PEOPLE'S SCIENCE CONGHESS

8^.±lJ^arch_1990

£ormat__for,..Deleoates

Name

Age

M / F

Sex

Residential Address

Occupation

Re si:

Phone

Defecate

Office :

/

D . D • No .

fee Rs.50/

Date :

sent on

: Yea / No

If yes9 Please give- details

Return journey reservation

required

Train No

....00.00..Date

Rs. .

..............

sent on . .

ny DD No

:

Mode of Transoort

Please give details

(Train / Bus / Air)

Any other information

for Rs.50/- drawn in

I am enclosing a DD No. . ’Karnataka Rajya Vijnana Parishat,

favour of "the Secretary

Bangalore.

9

Signature

addressed to the Secretary,

Coni

i

/

BEING HEALTHY

(or)

HEALTH FOR

INTRODUCTION

- NOW

:

The’ single most important need for all of us is good health

I

It is more important to us than all the wealth in the world,

is true that all of us living must eventually die-but while we

if we must be in a position to enjoy our lives and live, to the

fullest extent,

healthy.

we must be healthy.

Ill health and disease als

leads to premature deal th fo r drores of our people.

While in

many eountries of the world a child bom can .expect to live on

an average for 75 years or more an Indian child can expect to

live for only 57 years.

While in many countries of the world

for every 1000 children bom less than 10 will die in the firs

year of life.

in our country almost 100 will die within one ye

more than one in every ten.

Even this figure does;not tell the -cruth for it as an

<

average of the rich few and the ttiany who are poor,

The poor

have a for worse situation and die farmore easily than the ric

And more importaiat such figures hide the fact that while they

live, the poor suffer from repeated attacks of disease and the

grouwth and development is so stunded both physically and

mentally that they can never live fully.

WHAT IS HEALTH ?

’’Health is not the mere absence of disease.

Health is

a state of complete physical/ mental and social well-being”

(Definition of Health by World Health Crganisation)..

what

is it that our beigg healthy depends on?

Being Healthy depends essentially on our having adequate

food to eat, safe water to drink, a clean environment to live

in, proper employment and proper leisure,

components that are essential to health.

It is these five

*5

:

2

people who die of hunger are seen as dying of some disease or

the other.

A body weakened by hunger is a prey to every passin

i llness.

A mild diarrhoea,

an attack of measles,

a chest infec

a fever

tever - which in a normal healthy person would be only a few

inconvenience that would go away by itself, is enough to kill a

malnourished person especially children.

Thus it is that the

commonest cause of death of children are conditions like respir

(chest) infection, diarrhoeas, measles,

all of which need never

caused death at all but for the malnouri shment.

Malnouri shment also leads to a stunting of the physical

growth of the child,

so that it can never realize its potential

(The average weight of the Indian rural male is as low as 44 Kg

while of the female is only 40 Kg.).

The root causes of malnutrition lie in poverty - in the

inability of our people to purchase the food they need. There

i sz except on occasions/ no true scarcity of food.

Indeed our

country grows enough food - even to export if necessary.

And

if needed we have the capacity and the knowledge to produce

much, much more.

A BALANCED DIET:

Is malnutrition caused by lack of knowledge about the type

of food to be eaten?

Scientists say that a proper diet - a

balanced diet for an average Indian must include adequate stapl

grain like rice or wheat or jowar,

include about 170 gms.

and adequate pulses.

It mu

of vegetables, about 65 ml. of fats and

oil, 55 gms. of sugar and at least 250 ml. of milk or equivalen

value of meat,

fish or eggs.

If a person has all this he needs

no special health foods, no tonics to maintain his health.

Foo

is the best tonic.

Grains like rice or jowar or wheat is the main food,

chief supplier of energy for the body,

It is

The fats and oils are a

I

3

s

Other than these the body also need small amounts of

substances called vitamins.

Carrots, mangoes, leafy vegetables

and fish, meat especially the liver are good sources of Vitamixa substance essential for our eyes & skins.

major cause of blindness in India.

Fish,

Lack of this is a

fruits & vegetables

are a good source of Vitamin-C, especially lemons, guavas,

ami a

Even green chilies & other fresh vegetables & fruits contain th

A lack of this leeds to painfull bleeding into the skin and join

Milk,

eggs & meat provide Vitamin-D.

However a good exposu

to sunlight is by itself enough to provide enough Vitamin-D &

deficiency of this substance which is essential for strong bone

teeth is thus commoner in women who stay indoors ail the time.

Then there are minerals, like iron which is needed for the b

clacium that is needed for bones and iodine.

obtained from good,

Thesd too are

and the balanced diet suggested would provid

all of it.

I

However the average Indian finds such food far out of his re

His money is just enough to buy the staple grains that he needs

I some salt and perhaps a few chilles, and if money permits a bit

of dal.

An average Indian family of about 5 or 6 people would

require almost 3.5 Kg. of rice or lowar or wheat and about a

quarter kilo of pulse per dayo

This itself would cost at least

rupees twenty per day and even this is a great struggle to obta

And one has to remember that on many days there is no work to be

or there is sickness that prevents him from earning- a wage,

It

for these reasons basically that the poor do not have a balanced

diet.

They krow that milk is good for children,

that eggs are

etables are good,

that green ve

ve'etables

th=»t meat and

good for health,

fish make you strong - but they cannot but itw

There is nothing much that a doctor can do,

as a doctor to

remove this single most important cause of ill-health,

to prescribe a

Were ho

tonic or a milk powder or health food he i s

actually depriving the family of much needed food,

Such health

foods and toni os are frauds promoted by drugs companies to make

:

4

;

vegetables/ bananas,

guavas, orgnges and lemons are all healt

and more nutritious that any tonic and far cheaper too.

CCMBATTING HUNGER;

Then what indeed can be done to tackle hunger and ensure o

health.

The single most important measure i s to ensure employ—

ment that provides the minimum income necessary for a person to

live as a human being.

This would mean effective formulation

implementation of laws regarding land reform and of ensuring a

minimum wage for agricultural workers and indeed all other

categories of workers.

Whatever the circumstances

the minimum

wage cannot be less that the amount needed to provide the minim

food, clothing and shelter needed to sustain life and this can

determined by scientific calculations.

Ensuring employment must also in the present context mean

rural development programmes and technologies and industrial

development stratergies that are able to absorb the entire labo

force and provide gainful employment to all

•

NUTRITION EDUCATE ON:

However a proper programme of nutritional education may

be needed in addition to ensuring a minimum income,

especially

help parents make optimum use of the scarce resources available

provide proper nutrition to children.

Malnutrition in children

is often compounded by wrong feeding practices and ineffieicnt

use of available- resources.

Breafct feeding during the first 9 months of life is one

effective guarantee of good health,

The change to bottled milk

powders and infant formula is a major cause of preventable infa

deaths and in most cases should never be done,

Even where

bottles are to be used close attention need to be given to wash

the bottle and plastic nipple in boiling water for at least 5

minutes or better still feed the infant with a clean spoon and

avoid the bottle altogether.

*

s

5

3

cheap fruits like banana etc. should be given them as also a

greater content of fats and oils.

FOOD SUPPLEMENTATION SCHEMES:

4

Food subsidies are no long term solution as they are'diffic

to sustain due to high costs arid more important as they create

culture of dependency.

.However given the abyssmal poverty of s

sections of the population and the impact that^it has" on the fo

intake of the sections within these sections which are most

vulnerable to the ill effects of malnutrition namely ‘children a

p reg an ant women, food supplementation or subsidy schemes remain

an essential component of primary health care.

It is therefore

essential that the special nutriti'dn programmes, the I CDS

’ Anganwadi* based programme and mid-day school meal^s programme^

strengthened and expanded along with schemes like the 1 food for

work1 programme. Efforts need $lso be made to administer them

efficiently, and in a corruption free manner and to ensure that

these subsidies reach the sections that need them most.

SAFE DRINKING WATER:.

After food, the single me st ’importan t determinant <f health

is the availability ef safe, potable drinking water.

an essential* component of all life.

Water is

Today the efforts tb secur

adequate water for one1 s essential needs occupies the energies

and time ef most households,

especially of the wemen.

There ar

many districts especially in Punjab, Haryana, Andhra and Tamil

Nadu where the water so obtained had deleterious levels of

crippling'of a considerab

fluorides - a substance that leads

At other places high levels

section of the population.

iron

or salt makes th.e, water difficult to drink. Indiscriminate

dumping of factory effluents especially from chemical companies

and tanneries have also rendered water hazard>us for drinking in

many areas all over the country, as for example in and around

Madras, N^rth Arcet etc.

-s G

drinking water are therefore the two sides of the same coin.

Scientist^ estimate that almost ■'80% percent ef all preventable

incidence of sickness can* be eliminated by provision of.safe

drinking wat^r alone,

'The status of health in the .ountry sho

be measured’ not by the number of doctors it has but by the num

of water taps' - a very true quote indeed to which are may add

Qumber if water taps with water in them!

Provisi.n of safe drinking water and prtper sanitary facil

is. not an insunnountable problem even with already available

technoligy.

what wculd concretely need to be done for this in

your area? One may for exanple need a) proper construction of

wells taking all the necessary safety precautions to prevent

cntaimiaticn » chlorination .f wells c) filtration plants

in urban areas and larger rural habitats with a regular piped

water supply d) preventi.n of- defecation near tanks and streams

fr.ni which water is used for drinking purposes e) instruction

Jf l.cally appr^riate, cheap and culturally acceptable latrine

along with a proper sweage disposal system in urban and larger

rural habitats f) deflucridation techniques or identification o

safe drinking water sources in fluoride and ir.n affected areas

g) preventing factories and sweage disposal systems from dumping

untreated or hazardoues waste into river and other water source

inclining the sesj. If indeed this is such an. important, yet in m

places an‘easy measure, why has it not been done?.

There are m

reasons for it bu^. one major reascn we should n.te is because w

the people Have noc demanded it

despite the fact that^&Lsrrhoe

has killed and polio has crippled more of our children than any

• ther single cfisease!

Eventually rne we can ensure cur own

health and it is high time we organized and ensured safe

-drinking“'water in our own area.

®here are however many areas in the country where availabi

r f any water is a great problem, In such areas engineering work

•minor or major will ha\e to be taken up or new technologies like

desalination of aalt water adopted.

tit

ENVI ROJMENT :

I

7

to both industries and to the inefficient smoky chulhas are a

major cause of chronic cough and other respiratory problems.

Indiscriminate use of pesticides and unsafe unscientific dispo

■>

wf industrial wastes, poisons the land and water in isany area

Biological

envirement

:

Man as part of the living world,

i

I

and related by evolution

all living things, is also affected by a ny serious affection

Cutting down of trees and green plants dep

the living wor±d.

the air of oxygen sc essen’eial for life. The indiscriminate

killing off of so many plants and animals has alteredthe del

balance in nature on which all life depends.

This as well as

unplanned urban and rural development that leads to dirty ces

water in all our cities and towns have become ideal breeding

grounds for mosquitoes and flies and other cdrriere ef disease

The mosquitoe- al®ne is known to be’ a vector of 5 diseases in

India. Malaria, filaria, brainfever (viral encephalitis),

viral fever® (dengue), haemorrhagic fevers (fever with bleedin

the first three of which are major causes of death and diseas

Flies are the Carriers of diseasd like typhoid, cholera, worm

and dysentery and many other diseases. -The sand-fly causes

Kala-azar in many parts of Bengal, Assam, Bihar and Orissa.

Similarly pests on crops are also rapidly multiplying.

Contr

of such pests whether affecting man or crops is possible in th

long run only by ensuring a proper ecological balance and a

healthy environment.

Measures like pesticides may be needed

a limited and controlled manner but seldom will it by itself

t

a solution.

(The failure

programmes like the National Mala

Control Programmes are related to this).

SHELTER :

However by environment we need also include the social

environment. The provision of good shelter and clothing is o

major aspect, of this.

A person with adequate clothing hiving

in a well ventilated house which is not over crowded within

the house Or located in an over crowded area is far less like

8

Of the various respiratory Infections, by far the most

serious is tuberculosis.

Despite various programmes the

incidence of tub’erculosi s continues to rice and is more than

million• today.

°f there despite the fact that good drugs are

available 5,00, 000 die every year.

On the other hand, tubercul

which was a common disease in the West once is now almost

eradicated there. This is not prirarily due to drugs but to le

overcrowding, better shelter and nutrition.

Even in India,

tuberculosis is primarily a di seas of the poor and., ^a reflection

of their standard of living.

EMPLOYMENT g>

I

Another aspect of social -environment and a essentia^

pre-requisite for health is proper employment and leisure.

Proper employment is not only essential because an income

purchases food & clothing and shelter but it is essential

as an end in itself for mental and social well being. Indeed

man's prime want is to play a productive and useful role in.,

society and his satisfaction is most when his. employment ensure

this.

Abd his leisure he can use for rest and for developing

all the various aspects of his. self that all contribute to

being, a complete human. Indeed a social environment free of

•onfliets and tensions, meaningful employment and adequate s

leisure are the basis for mental and social well-bei*ng for

a truby healthy citizen.

(The basis of many a social disease

like suicides, alcoholism, drug addictions, crime5 are to be

found in the lack of satisfactry work and related social tensio

Just as only healthy individuals can make a healthy society, it

is also ttue .that a healthy society is needed for healthy

individuals.

:

.

HEALTH EDUCATION ;

To nearly all people much of this is common knowledge.

Medical science has only helped establish that most disease

result from a lack of these essential requirements. Medical

-I

i

1

This knowledge about how our body works and about how disease

are. caused is another essential pre-requisite of being health

It is necessary that not only doctors and nurses or health

workers know about-this but that every person has a ininimum

idea of it, so that, they can understand thpir own bodies and

keep it healthy*

( .

1

Health education should also include a minimum kixowledge

of diagnosis and treatment of simple diseases. Take for exam

.diarrhoea. If diarrhoea is watery and not associated with blo

$

I

or mucus the best and only correct treatment is to give the

patient’plenty of fluids.

The fluid adviced can be prepared

the home by mixing a scoOp of sugar and a pinch of salt in a

glass of boiled water* Alternatively rice water with some sa

a^ded is also good treatment. The majority of deaths due to

diarrhoea, especially in children can be prevented by this on

=1

measure alone.

Indeed more deaths have been prevented due to

this one advance than any other single advance in medical scie

in these last few decades.

Similarly colds, simple cuts & bruises, an occasional bo

ache or headache can all be treated with proper knowledge.

Health education should also be adequate for people to

identify certain serious diseases like polio, measles,

chickenpox/ tetanus etc. so that they seek medical help early

f

Measures to prevent diseases like tetanus & rabies, know

about immunization, knowledge about occupational health hazar

all are essential aspects, of being health.

EDUCATION :

Obviously a literate person has far greater access to suc

knowledge than an illiterate person. Literary is an essential

Component of health. But mere literacy is not enough*

The le

of general education is important.

1

General education increase

the ’health' literacy1 of the people. It enables them to und

stand their health problems and how to identify, prevent and

10

disseminate a lot of knowledge about health, and the. access to

", '■ -4

thi sin formation is directly related to literacy.

.Worneh* s literacy and schooling of girls peeds special

emptrasis for the impact of this;.on society & the family, is

much more.

Indeed just like food, water, shelter and worfor education

must be also considered an essential component of being healthy.

MATERNAL HEALTH CARE :

One area where medical science has led to a great benefit

is about pregnancy and childbirth.

There was a time when many

women and even more children died due to pregriancy and at

childbirth. Now we can in most cases detect problems of

pregnancy well in advance and take proper steps to save the

lives of the children, and mother. We know that a pregnant

women needs extra nourishment and should have more rest and

should be spared heavy work. We also know that if they have

many children top soon-and too frequently it endangers the

lives of the child a nd the mother. It is recommended that

the first child'should be after the age of* 21, the second child*

should be after a gap of 4 years at least and there should be

This is essential to safeguard her health.

no third child.

Suitably trained persons • both doctors and health worker §

can datect the .pregnancy cases; where natural delivery is not

possible or dangerous and in such cases the child can be safely

delivered by an operation or forceps.

When natural delivery; tak

place we can ensure by simple hygienfcc measures that any trained

nurse knows that the delivery is safe and that there are no

complications for the mother.

CHILD k CARE :

The newborn child fed on breast milk from a healthy mother

is likely to be healthy. Immunication prefects us against a

5

ft

<

•?

'A

11

*

-

JrLrth,^ and many more (about 40/1000) die in this age group

due to ca uses related to childbirth indirectly.The reason for this Ties in the poor health of our mothers

and the difficulty in getting or total 1 ack .of ..maternal and

Even if they are available

child care in most of our villages.

women are not adequately aware of why they need such help and

the vast difference such help, will make to their lives and that

4-

of their ^children1 s.

The children of illiterate women die far

more often, than those of literate mothers.

Studies have even

estabilished relationships between numbers of years of* schooling

A

of the mother^ and infant mortality.

This is not only related to. the proper socio-economic

background of the illiterate and the knowledge about health

that literacy contributes but also to a critical awareness of

their own reality and their attitude toward^ it.

51

■

’

The - inability of the illiterate woman to make the correct

choice - to ensure the health of their children, their own heajL

and of their children, their inability to plan for the future

security for th^ family leads her to reject the temendous pressu

that the government exerts today for the family welfare programm

and thereby she seriously endangers her own health.

a

♦

4

THE FAMILY PLANNING PROGRAMME :

India i^one of first countries in the world to have a maj

national family planning programme.

Enormous resources have bee

spent on it - *in the last five years plan period alone - more

than 3000 crores have beep spent-'on it. Nearly half the budgeta

allocation for health care goes*to family planning - yet the

programme has not succesded.

The crude birth rate over the

last H years has remained static at about 31/100r' as against

a 22/1000 that it was supposed to reach. Or in simpler words

despite 3000 crores spent there has been almost no change at

all in kirth '"rate. The measege of family planning has been

12

i s the only

tenI, Invent ,r 3avlngs

they are .la 4r elok it is only their ohilaron that they can fa

ac upon.

(In a better income gr.up in our ccuntry .r in more

developed c.untries savings is in the form of a home,

in a bank

pension, provident fund etc)

etc).. N.w when 10 ' aut

100 children

die the need

ensure a living child and that ioo ’ a male child

kedemes a matter of j----para mount importance.

The less of a child

for a mother is a matter of great r“arjeny and guilt, f<r the bein

she brought into the world and loved

-J so intensely is ±jst as th

was unable to protect it. But the millions of mothers are voic

and we do not hear, them

cry. And even as they cry they need to

through it again - to Jbear more children.

Only in s. society where there is social security and low

infant mortality will the birth rate erne down. And .nly in a

iety where the woman is literate and liberated en.ugh to mak

hex own cheiees will family welfare be realized.

There are

countries like Cuba where there is nr Family Planning Programme

at all yet the birth rate is low. There is no population problem

n any .f the developed countries .f the world. Indeed all of

them want more people.

Tha day dur women are educated, they day

they are able, tc ensure the survival of their children and becom

active participants of social development, that day family

planning will bec.me universal.

Till then all we can do it to

ensure easy access f.r every mither to health services which

include family planning and to inf.rmation ab^ut family planning

The money being wasted on many of the schemes be better spent in

educating women, providing, basic health care and .n development

pngrammes.

PREVENUCN OF ENDEMIC DISEASES :

Good knowledge .f the way diseases spread consequent to the

advancements of medical science have also helped us cmpletely

eradicate some diseases like small pox which once killed millions

of people every year. It has made it al so. possible fwr us to

eradicate ®r control may of others.

'

guinea women for examp

Take

1

v

15

w the district or taluk hospital.

Even here no mere than some 150

drugs are needed to take care of all the possible medical treatm

yen may ever need.

Unfortunately in most places .including these 25 primary hea

J

Even at taluk and

centres these 25 drugs are not available.

district level hospitals often there 25 drugs are not available

*

not to speak of the 15 0*. But at the same timeevery local drug

shop and even at villages there are freely available hundreds of

4

other tonics and injections and tablets which are of no use at a

Because people do not know the causes of their diseases they ofte

take tonics and $*ther tablets ’ f«r feeling better or stronger1.

Then why are they there at

But these medicines waste our money,

all?

Why do doctors prescribe them?

them?

Who' do companies make thefci?

Why do governments allow

Of all these questions only the last has an easy- answer.

T

companies make them because they get a lot of money by selling th

We need to ensure that our governments and doctors dch not encour

such useless drugs that waste o-ur money.

We also need to insist

that the drugs essential in that area are cheap and easily

accessible.

OF DOC^RSsLast of all, we need doctors/ too,

at least in every primary

health centre there must be two doctors

doctors who are intere

They can help when our own knowledge and

in serving the people.

training and that of the community health ^workers is inadequate

Doctors are also needed as scientists to find out more about the

causes of diseases so as to discover ways to prevent the disease

and to treat than. In every district there should be at least o

hospital where modern scientific instruments are available and

specialists in various fields are available to treat serious

They also need to provide training

Conditions or rare diseases.

to newer health personnel and educate people about the causes of

Ul, health and the way to be healthy.

5

HEALTH Pff&ICIES

If many doctors today to not do this it is also rbecause

9

-1G :-.

have proper, equitable access to' health or the other benefits

that advancements in medical science have made possible.

(

Goo 1 health needs far more,, than doctors and drugs.

The

struggle for being healthy is part of the struggld against cond

that make ill health possible. It is a struggle rftor good food,

good water; a clean environment, for good employment & for

leisure. It is a struggle for. a better quality of life.- Scienc

gives us the knowledge and the possibility of making good health

care available today but to^make thij? a reality, society must

*

be wil-uing to read stribute available ^resources so that these bas

needs for all are met.

This then is the true meaning of Health

for all ¥y 2T9J Ad.

*

J

Vf

&&&&&&&&

4

*

s

•#

4)

>

«

5

Com

SCIENTIFIC AWARENESS FOR PEOPLES^BENEFIT_-__CHAI^S_CONTRIBUTI

Catholic Hospital Association of India is a national

organization of 2,222 member hospitals, dispensaries, health

centres and social service societies spread throughout the

Country. Our member hospitals are noted for quality and

efficiency of services and utilization of latest technologie

and advancement in medical science.

Very often, missionary sisters and priests had started these

institutions in needy areas where suffering humanity had no

other option for health care. Some of them started in a ver

humble way and grew into impressive institutions. It was th

compassion and healing spirit of Jesus Christ that motivated

them to go to the extreme rural areas and to the peripherie

But as the years passed, critical evaluation makes us

realise that some of us have lost the original vision and

commitment to the people. Survival and maintenance of the

institution beceme the focus of attention. Sophistication

and incorporation of advanced medical technology turned out

to be the answer to survival. Some of these modern changes

are not affordable by the poor majority and the fact remains

that we fail to realise the additional burden we place on th

poor due to this.

CHAI,holding on to its original vision, endeavours a

critical analysis of the health situation in the country

in relation to the socio-economic and political situation.

Very often many of the health problems, in a detailed

analysis, ultimately are due to an unjust distribution of

land, unequal sharing of profits, exploitatory marketing

systems and unfair wages. This leads to poverty of many an

surplus for a minority. It is this poverty-stricken

majority that have malnutrition, recurrent illnesses and

chronic diseases unattended adequately. It is the weak wome

of this majority who will be doing hard labour inspite of

carrying a baby in an anaemic body. They will deliver a lo

birth-weight infant which will continue to have a poor

2

mosquitoes in plenty. They are fondled and cared for by

elders who cough out tuberculous bacilli. Their weaning food

are mixed with water drawn from the village pond which

r

carry any number of Rota Virus, Amoebic Cysts, Round Worm

Ova, Hepatitits Virus, Typhoid and even Cholera Bacilli.

Out of whatever little money their parents earn toiling

manyr.hours in the hot" sun, a good share is spent in the

local arrack shop which is run quite profitably by the rich

business class. This business class will see to it that no

saving schemes survive in the village as it will make the

poor villagers stronger in facing any financial crisis.

Only when such saving schemes collapse, the poorest of poor

will fall at the feet of the money lender and become more and

more chained to him.

Health can never be a reality in such a vicious circle.

No amount of medicines or efficient medical staff can ensure

the total well-being of that community.

0

In the light of the above analysis we realise that unless

people are made to take care of their own health, HEALTH

FOR ALL BY 2000 AD will be a "myth. It is this "enabling"

process that CHAI has been facilitating through many of

its programmes. Ultimately we want "empowered" communities

who can understand their health problems and take appropriate

remedial measures.

believe that the poor can do

"something" for themselves and they are "somebody" in

society. The poor man with a number of miseries, a great

deal of incapacities and innumerable needs, poses before us

as a man who has lost his dignity. We want people to

rediscover their dignity and self esteem. They should

also rediscover their potential in achieving remedial

changes.

Our awareness building programmes are aimed at raising a

critical consciousness' level of the community so that

3

insisted upon, based on a prioritization. Those health

activities which will bring about maximum desirable changes

in society and those activities which require minimum resourc

input., deserve a high priority. If people are involved in

health activities it becomes a people's movement. It is

chis movement we are facilitating through our orientation

sessions, training programmes, follow up and evaluation and

replanning < f various projects. Many of our hospitals are

getting reoriented in undertaking community based health

care programmes. Many institutions have taken up training

of local community health volunteers to increase the army of

community health movement. At a national level we organise ;

programmes for leaders of community health projects. We

also identify appropriate resource persons in various parts

of the country and strengthen regional resource team for trai

q

o

more workers.

CHAI has taken leadership in coordinating many of the isolate

health activists groups and promoting linkages among them.

We also facilitate exchange programmes between people based

health movements of other countries such as Philippines,SAARC

Countriesc Latin America etc.

Another attempt of ours is to influence the doner agencies

jn America, West Germany, Holland, Switzerland, etc to

direct more funds to ’people based’ health programmes rather

than sophistication of big institutions.

RATIONAL DRUG THERAPY: Drugs being one consumer item in

which the consumer has no say in the selection and use,

was our maj^r concern fox/nany years. This consumer item

.’as misused widely knowingly or unknowingly. The prescriber

has to apply maximum ethical principles considering

financial status of the patient, cost benefit ratio,

actual indication, side effects, availability of

alternative drugs etc. Through various conventions, training

programmes, our publication Health Action , we have promoted

the concept of essential drug and rational drug therapy.

4

hospital formulary. Still the pressurising marketing

technics of many drug companies are influencing our

institutions. In the field of quality control of available

drugs we do not have enough facilities to monitor and report

promptly to member institutions. Even at Government level

only lour states in India have adequately equipped drug .

testing labs and partial facilities in ten states,

states. 10

states do not have any equality control bust

test labs.

labs. To meet

this lacunae in service, and ensure the quality of the

drugs 9 CHAI is planning to start a central quality

control lab of its own.

on the

The necessity of public opinion andconsumer pressure

of

prescribing doctor, for the effective implementation

Our publications

rational drug therapy is quite significant.

continuously try to educate

including iHealth Action magazine

the masses; in this regard.

CHAI had initiated to bring together the producers »f

essential drugs who also believe in Rational Drug Therapy.

The plan is to form a cooperate body of these producers for

pooled procurement of bulk drugs and ensuring steady produc

of good quality essential drugs at reasonable prices.

MISUSE OR MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY : We are protesting against

misuse of any medical technology. The Amniocentesis for

sex determination and descrimination to girls are strongly

condemned. When Ultra Sound Scanning and CAT scanning becam

the fashion of the day an unhealthy trend to overuse them

was noticed. The Doctor-Medical Technology Axis was

unfavourable to the poor man. We also expressed our distres

in the growing commercial cooperate sector hospitals,

especially by the business groups and non-resident Indians.

The value system cultivated in these institutions is damagin

to the medical profession.

There are attempts to study mnd campaign against unnecessar

surgical procedures such as Caesarean, Appendicectomy and

5

which if explained to mothers can save millions of dying

children. We had organized 9 regional workshops for

Paediatricians and Paediatric nurses in reorienting them

in diarrhoea management. Each hospital is supposed to

start an Oral Rehydration Corner in their cut-patient

departments and in the paediatric wards. An innovative

attempt to expose ORT to the general public was done in

the twin cities of Secunderabad and Hyderabad by starting

demostration counters at Railway Stations, Bus Stands,

Post offices, Museums etc. during last summer.

Immunization is another scientific technology that, has to

reach e/ery common man for a safer future generation. Social

mobilization for immunization is one area to which CHAI had

given emphasis last year. There was overwhelming response

from our member institutions for taking this up seriously.

We believe many of the herbal and home remedies practiced

through generations in various parts of the country are

effective. It is cheap and affordable to the people.

Scientific bases of its action is yet to be discovered.

A lot of research if undertaken in due course might generate

many effective indegenous drugs eg. Reserpine, Vincristine

etc. We encourage the practice of herbal medicine.

CONCLUSION : CHAI believes in peoples’ welfare through

peoples’ power. This power of the people generates from

awareness. building and peoples’ organization. Science

movements contribute enormously to peoples’ awareness.

BACKGROUND PAPER ON HEALTH AND PSM'S

Presented at 2nd All India People's Science Congress,

Caleutta.

BY DELHI SCIENCE FORUM.

India was s signatory to the "Alma Ata Declaration"it a

adopted by the World Hea1th Assembly in 1978, which gave the

call "Health for all by 2000 AD". Today, 10 years after the

Alma Ata declaration, the state of health in India makes the

country one of the most backward in this respect. The faciliti

in some of our hospitals may be among the best in the world and

the same can be said about our doctors.

This, however, does

not determine the health ofnation. The only true index of a

nation's health is the state of health of the vast majority

of people, andnot that of a privileged few. In this regard the

Government's own "Statement on National Health Policy"

(1982)

states The hospital based disease, and cure-oriented approach

towards the establishment pf medical services has prodived

benefits to the upper crusts of societ specially those residin

in the turban areas. The proliferation of this approach has bee

at the cost of providing comprehensive primary health care

services to the entire population, whether residing in the urba

or the rural apeas".

POST-INDEPENl)ENCE expansion

in

health

services

However this should not detract from the fact that since

independence there has been improvement in many areas, both in

terms of growth in in restructure andinterms of their actual

impact on the health status of our people. The following table

gives an account of the progress made.

Table

1

IMPROVEMENT IN HEALTH FACI LITIES/CONDITIONS SINCE INDEPENDENCE

Year

Life expe

tancy at

1951

1961

32.1

Infantmort

ality rate

180

No. of

Populat ion No. Doct

hosptiaIs per bed

of

per

PHCs pop

2694

3199

725

16

-2

2

2-

It is however important to understand both the content

and the process involved into this progress made in the healt

sector, There is a tendency to cite the above figures to make

out a case for positing that this progress has been adequate,

hence no major policy interventions arenecessary. The health

services at the time of Independence were a function of the so

economic and political interests of the colonial rulers. Cons

quently they were highly centralised, urban-oriented and cater

to a small fraction of the population. Public health services

were provided only in times of outbreaks of epidemic diseases

like small pox, plague, cholera etc.

The post-independence er

witnessed a real effort at providing comprehensive health

care

and in extending the infrastructure of health service.

Even the West wemt through this rapid phase of improvemen

of health services, after a period of stagnation, at the turn

of the century, In the early days of the Industrial Revolution

the bulk of workers who came to work in factories from the

countryside suffered from malnutrition,

- communicalble diseases

an high rates of infant and maternal mortality. When it was

ed that the very suffering of the people was endangering

industrial production (and thereby profits), active steps were

publicshealth services. Economist

taken to dramatically imrpve publicchealth

who had considered medical

medical expenditure

expenditure as a mere consumption

item, realised that allocation on health care was actually

an

investment on increasing productivity of labour,

labour. Another

major thrust was provided in the aftermath of the Second World

War, when with the rise of organised workingclass movements and

democratic consciousness

consequent development

development of

the consequent

in many

of democratic

consciousness in

States" was mooted

uropean countries the concept of "Welfare States”

in Britain,

Britain, which is high

Scheme in

For example the National Health

Health Scheme

- shape

regarded even today, -took

under the Labour Government just

after World War II. A rough analogy can be drawn wkth this and

the Indian situation after Independence. Consequent to the

transfer of power in 1947 the character, amd as a result the

, - the ruling sections changed and conselong term interests, of

quently their intereest. and motivations were qualitatively

different from that of the British. Their own interests requi-

-s 3

At the same time major scientific discoveries revolutio

the treatment and prevention of many diseases. These hav

contributed greatly to the increase in life expectancy and

in reduction of mortality. The antibiotic era has made it

possible to control a larger number of infectious diseases

for which no cure was earlier possible. Rapid strides hav

been made in the field of immunisation, diagnostics, anaes

surgical techniques and pharmaceuticals. This has had a

dramatic impact on mortality and morbidity rates all over

world. There are pitfalls of an absolute dependence on te

nological solutions to health problems, but it is definite

true that in many instances newtechnologiqs have had a ma

impact. However the imporvements in ourhealth delivery sy

have not kept pace with the needs of a vast majority of ou

people.

So much so that the Government's "Statement on

National Health Policy" (1982) is forced to state "Inspite

such impressive progress, the demogfaphic and health pictu

of the country still constitutues a cause for serious and

urgent concern".

BALANCE SHEET OF HEALTH

The following statistics give a picture of the state of

health of our people:

— Only 20% of our people have access to modern medicine.

— 84% of health care costs is paid for privately.

— 40% of our child suffer from malnutrition. Even when

the foodgrain oroduction in India increased from 82

million tonnes in 1961 to 124 million tonnes in 1983,

the per capita intake decreased from 400gms. of cereals

and 69 gms.

of pulses to 392gms. and 38 gms. respectiv

Due to increasing economic burden on a majority of the •

people, they just cannot bujr the food that is theoreti

cally "available".

—Of the 23 million children born every year, 2.5 million

die within the first year. Of the rest, one out of nine

dies before the age of five and four out of ten suffer

-s 3 s-

At the same time1 major scientific discoveries revolutio

the treatment and iprevention of many diseases. These hav

contributed greatly to the increase in life expectancy and

in reduction of mortality. The antibiotic era has made it

possible to control a larger number of infectious diseases

for which no cure was earlier possible. Rapid strides hav

been made in the field of immunisation, diagnostics, anaes

surgical techniques and pharmaceuticals. This has had a

dramatic impact on mortality and morbidity rates all over

world. There are pitfalls of an absolute dependence on te

nological solutions to health problems, but it is definite

true that in many instances newtechnologigs have had a ma

impact. However the imporvements in ourhealth delivery sy

have not kept pace with the needs of a vast majority of ou

people.

So much so that the Government's "Statement on

National Health Policy" (1982) is forced to state "Inspite

such impressive progress, the demogfaphic and health pictur

of the country still constitutues a cause for serious and

urgent concern”.

BALANCE SHEET OF HEALTH

The following statistics give a picture of the state of

health of our people:

— Only 20% of our people have access to modern medicine.

— 84% of health care costs is paid for privately.

40% of our child suffer from malnutrition.

Even when

the foodgrain oroduction in India increased from 82

million tonnes in 1961 to 124 million tonnes in 1983,

the per capita intake decreased from 400gms. of cereals

and 69 gms.

of pulses to 392gms. and 38 gms. respective

Due to inceeasing economic burden on a majority of the ■

people, they just cannot bu$ the food that is theoreti

cally "available".

—Of the 23 million children born every year, 2.5 million

die within the first year. Of the rest, one out of nine

dies before the age of five and four out of ten

suffer

,4

0

—- 50% of children and 65% women suffer from iron defi—

ficiency, anaemia.

—— Only 25% of children are covered by the immunization

programme. 1,3 million children die of diseases whic

could have been prevented by immunization.

°f

total population of India is exposed to

Malaria, Filaria and Kalazar every year,

— 550,000 people die of TB every year.

About 900,000

people get infected by Tuberculosis every year.

—nAbout half a million people are affected with lepsor

which is 1/3 of the total number of leprosy patients

in the world.

— 70% of children are affected by some intestinal worm

infestation.

— 1.5 million children die due to diarrhoea every year.

A comparison of Infant Mortality Rates (i.e. number of

under the age of one month per thousand live births) of some

countries in 1960 and 1985 shows that many countries with a

poorer or comparable record 20 years back are today much ahea

of India.

TABLE

2

Country

I MR

in 1960

IMR

in 1985

Turkey

190

84

Egypt

Algeria

179

93

India

168

16 5

Vietnam

160

81

105

72

China

UAE

150

El Salvador

145

142

Jordan

135

36

35

661

49

Sources: *State of the World’s Children’ W87 - UNICEF.

•

5

TABLE - 3

Plan period

% share of Health

Budget

3.32

3.01

2.63

2V11

• 2.12

1.92

1.86

1.88 (esstimated

1951-56

1956-61

1961-66

1966-69

1969-74

1974-79

1980-85

1985-90

Sources GOI, Health Statistics of India, 1984..

The government spends just Rs.3/- per capita every month

on Health. ( This may be contrasted with the estimated averag

expenditure, incurred privately, of Rs.15/— per capita every

month) The following table gives a comparison of the percenta

of govt, allocation on health.

TABLE - 4

Country

India

Egypt

Bolivia

Zaire

Iran

Zimbabwe

Kenya

Brazil

Switzerland

FRG

% of central govt, expenditure

allocated to health (1|983)

‘

2.4

2.8

3.1

3.2

5.7

6.1

7.0

7^3

13.4

18.6

Source: The state of the World’s Children-1987.

Moreover, even these meager resources are not equitably

distributed, 80% of the resources is spent on.big hospitals and

research institutions which are situated in metropolitan cities

TABLE - 5

COMPARISION OF NO. OF HOSPITAL BEDS IN RURAL AND URBAN

AREAS (As on 1*1.1984)

No. of Hospitals % of total

Rural

1894

26.37%

Urban

Total

5287

7181

73.63%

100.00%

No.of Beds %of tot

68233

13.63%

432395

86.37%

100.00%

500628

Source: Health Status of The Indian People, FRCH, 1987.

Of the total number (just over 2 lakhs) of allopathic

physicians in the country, 72% are in urban areas.

Further, on

15.25% of all health personnel work in the rural primary health

sector of the government. As a result of the highly inadequate

Govt, intervention in the health sector people are forced to ta

recourse to the private sector in health care. By this kind of

an approach, health has been converted to a commodity to be

purchased in the market.

Only those who can afford it can avai

of the existing health facilities. It is thus clear that healt

perceived by the Govt, as a low priority area with grossly ina

quate resource allocation, and a skewed pattern of utilisation

his is afundamental problem in the he

these meager resources.

sector which calls for rethinking retarding the whole developme

process in this country.

Here another disturbing trend needs to be mentioned.

In

last few years there has been large scale investment by thepriiw

sector on curative services. With encouragement from the gover

for the first time in India big businesshouses are entering the

of health care.

In addition to the fact that they areexclusive

meant for the elite, the trend is also an indicator of a certai

of Philosophy within Goct. circles regafding health care. It

kind of thinking which draws inspiration from a World Bank repo

which says ’’present health financing policies in most developin

countries need to be substantially reoriented. Strategies favo

public provision of serv;ces at little or no fee to users and w

little encouragement of risk-sharing have been widely unsuccess

(de Ferranti, 1985). This, in other words, is a prescription f

-

in providing

O

7

health care to all.

Increased privatisation

in health can only serve to exclude the most impoverished

sections, pricisely the section who need health services the

most.1. The answer to theGovt*s inability to find sufficient

resources for health programmes certainly cannot lie in

taxing the community tot provision of health care.

LACK OF HOLISTIC APPROACH

Health services, in the traditional sense, are one of the

main but by no means the only factor which influence the healt

status of the people.

Today the concept of social medicine

recognished the role ofsuch social economic factord on health

nutrition, employment, income distribution, environmental sani

tion, water supply, housing etc. The Alma Ata declaration sta

"health, which is a state of complete physical, mental and soc

well bring, and not merely the absence of disease or informity,

a fundamental human right and that the attainment of the highe

possible by level ofhealth is a most important world-wide soci

goal whose realisation requires the action of many other socia

and econokic sectors in addition to the health sector". Flowi

from this understa ding, health is not considered any more a m

function of disease, doctor and drugs.

Yet even today the exi

public health infrastructure in India is loaded in favour of t

curative aspects of health.

For a country like India, it is possible to significantl

alter the health status of our people unless preventive and pr

motive aspects are giben due import a rate.

An overwhelming majo

of diseases can be prevented by the supply of clean drinking wa

by providing adequte nutrition to all, by immunizing children

prevalent diseases, by educating people about common ailments

by providing a clean andhygienic environment. It has been est

that water-borne diesases like diarrhoea, poliomyeilitis and

typoid account for the loss of .73 million work days every year.

The cost in terms of medical treatment and lost production, as

quence, is estimated to be Rs.900 crores-which is about 50% of

total plan allocation on health.’

8

OU of four Slums are the extremely insanitary environmental

an

ygeinic conditions in which the slum population is living".

Further, while India accounts for more than 35% (3000 deaths

ev

day) of all deaths taking place in developing coun ries due to

vaccine-preventable diseases, less than 25% of our children are

covered by the Expanded Programme of Immunization.

How prevent

measures can alter the course of diseases is typified by Tuber

culosis. Drugs for treating Tuberculosis were discovered after

Yet, 29 years earlier, the disease had been almost totally erad

from Britain due to improvement in conditions of living. But ev

today, when numerous drugs have been discovered for treatment of

d sease, more thanhalf a million die of its every year in India.

We have seen earlier that

resource allocation is heavily bi

in favour of urban areas,

Similarly the emphasis on curative se

vices also reflects a bias in

our planning process in favour of

services vis-a-vis preventive and

promotive services. As in oth

services are a function of the political s

walks of life, health

health services

T

of a community.

hey reflect

the needs

hey

reflect the

needs of the ruling sections,

terms of resource and manpower allocation andin regard to the ch

technology. A holistic approach towards health care, taking

technology.

to account the socio-economic factors influencing health, demands

a level of conciousness which is lacking in our planning process.

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

II

The Alma Ata Conference defined Primary Health Care as

essential health care made universally accessible to individuals

and acceptable to them through their full participation and at

a cost the' community and country can affort". This concept was

mooted as <an alternative to the existing concept of comprehensive

health care, which vieweed the people as mere receivers of curati

seryees through doctors, health centres, dlspehsarles and hospit

It based itself on four broad principles:

1. equitable distribution of health services.

2. community involvement

3. multi-sectoral approach

4. appropriate technology

-s 9

3. Primary Health Centre Level-has a staff of 3 doctors (one

female and two male) and other auxiliary staff. PHCs have

facilities for laboratory tests, minor surgical procedures etc

They are also responsible for training of health workers, main

tenance of rec rds and for liaising .with various National Heal

Programmes.

While this 3 tier system is supposed to provide basic health

care, there are a number of "national health programmes".

The

cover areas requiring special attention and include areas like

Immunisation. Family Planning, Tuberculosis, Malaria, Leprosy,

Bliddness, ^hild helath (ICDS)programme) etc. Thes programmes,

also known as "Vertical Programmes" are technically not pert o

the Rural Health Scheme but areorganised along independent lin

with centrally administered control.

It is widely recognised that both the Rural Health Scheme

and the vertical progra,,es are plagued with problems of inadeq

facilities and resources. The annual report of the Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare (1987-88). very candidly states "becau

pf the resource constraints only 50% of the community Health Ce

would be established by the year 1990".

In other words the

targetted coverage of the PHC system by 1990 is just 50% Simila

.is the state of various vertical programmes. The Nutrition Fau

at ion of India in a study of the Integrated Child Development

Service (ICDS) says " Though ICDS has been extended to cover mo

blocks form time to time, the support it has received has been

gruding and halting" and often "extracted after much struggle".

The CAG report for the year ending March 31, 1987, has criticis

the functioning of three major programmes viz. Blindness gpntr

Programme, Tuberculosis control programme and Leprosy eradicati

programme.

/

These programmes have been pulled up fpr

improper

non utilisation of funds, non release of sanctioned funds and l

of planning andmonitoring of these programmes. The principal p

problem with all the health programmes in operation has been a

total lack of community participation and the consequent absens

of accountability of theseprogrammes to the local community,

-?10s-

I 50/6 of the total rural population.

these centres hsve be

set up, they are under staffed and suffer from lack of medicine

and equipment .

/another major drawback has been the difficulty in attracti

doctors to serve in the rural health scheme.

By and large doct

opt to work in rural centres only as a last resort, ^his refelc

on both the quaity and motivation of medical personnel manning

primary health centres.

Unwillingness of doctors to serve in t

rural sector is also an indictment of our medical education syst

The curriculum is heavily loaded in favour of curative medicine

and within this in favour of diseases (Conforming to themortality

and morbidity profile in the West. During their period of

training medical students are taught to rely on sophisticated

diagnostic aids. ^uch training ensures that medical graduates a

ill-equipped to work in conditions prevailing in the rural areas

Moreover the medical profession isinvesfed with an aura of glamo

which unfortunately is seen to be lacking in service in the rura

sectors•

It needs also to understood that entry into medical college

is by and large limited to those coming from a higher socio-econ

stratea, predominantly from urban areas, who consequently find

it difficult to conceive of working in rural areas. Even when

uneploument among doctors is not uncommonm doctors are unwilling

to take up jobs in PHCs. A two pronged strategy is required to

tackle the situation. Medical curriculum has to be reoriented

and entry into medical colleges needs to be regulated in a

manner which ensures amoreba lanced ’’mix" of students. bide by s

incentives have to beworked out to attract doctors to the rural

health schemes. After all its is impractical to believe that

doctors textkKXKxxxi:xh®x±thxxKkxxiK3#are natuitally fired by

altruistic motives and with feeling of "service to the poor".

At the same time, within the medical fraternity, there is a str

resitance in changingehthe age old concept of health as function

of doctors and drugs. Implementation of recent concept of prima

health care requi es a certain degree of demystification of

Medical Science. But within the established medical bureaucracy

-:11sever all theseprogrammes need tooperate

they arr6?

tbX is

and

but

through the rural

Separat? ^in^rative control

hSalth —• As a resu

needless duplication of administrative

verticarprr^10' regarding aims*

manpower, costs

the basic

aim behind

programmes of giving emphsis to problem

areas is lauda

ey need to be administratively integrated

with the rural heal

scheme. Otherwise, they will continue

-to wdrk .at oross<.purposes

e rural health scheme, often at

great cost to the available m

and human resources.

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

-^he slogan "Peoples"

health in people "hands has today

received universal support,

Diverse agencies cutting across all

kinds of ideological positions

| accept that community participati

is vital to the sustenance of .

any comprehensive health programme

The Govt's Statement

on Health Policy also recognises this posit

while statincr "Alqn

-tug z^iso, UVer

the years,

the planning process hasbec

over me

years, the

=rgely Qhifvious of the fact

ultimate ^ola of achievin

satisfactorv hea^

XXe

911

P“Ple

™

911

—t Ce

int the Identification of their

nvolvmg

l"9 the community

co""“"xty mt

"

health needs

needs andoriori

andpriorities

i--i oo as vsell

i i as in the

implementation and

management of the various health and related

P^ogT‘3mmes ”.. Unfort

of clarity on the

oasic lack

unately there is aa basic

lack of

ceoncept of commu

Participation. Often,

Often, especially in official

circles, it is take

O imply that the community participates in

collectively receivin

services.1

3’. * Strategy developed by the Govt, to

communir^^.!

bring about

Th

Y P3rcLC:LPation is the Community Health w'orker

(CHWf) schem

e scheme involves recruitment and traing of a

rkers from every village community. The CHW isCommunity Health

required to

in eract with the PHC system on hehalf of the village

a^ community

he rep. sents. The scheme ,was introduced

as part of the

SCheme' naSed 03 the recommendations of the

Srivasta^c1

onvastava Committee (1975)

Tho

- of

dandldates for the CHW schemes ere’ 1 " ""

perferhblld

community,

-:12sCandidates after selection are trained for a period of a

their training the CHWs are given

3 months. After completion of 1--an honorarium of Rs.50 and simple medicines worth Rs.50 per

free to continue in their earlier vocation, but

month. They are

2-3 hours every day to community health work.

expected to devote

As the CHWs scheme constitutes the Government s principal

effort in implementing the slogan of "Peoples" health in peoples

hands" it merits a closer look.

Under this scheme around 4 lak

CHWs have been trained. However the implementation and impact o

the scheme raises a number of questions related to the whole con

cept of community participation.

.

The CHWs scheme presupposes a degree of volunteerism

selected candidates. Otherwise a stipend of Rs.50 per motthis

is far short of an adequate remuneration for the CHWs whose

functions include - health education regarding preventive and

promotive measures; encouraging participation of community in

public health tasks; curative measures for treating simple disor

and referrals to the next level (sub-centre). In other words

CHWs is also required to play a leadership role in the community

However the methodology required to identi fy such personsis yer

In practice the contradiction between inadequate re

resalved in one of two w

neration and high expectations is often

performing the require

Either, after a short period of CHW stops

functions or dropts out of the scheme altogether, °r he sets hi

worked out.

(In shoirtd be real

up as a private practicioner in the village,

-- j than what a la

that the training imparted to them is often more

section of unqualified practitioners/quacks in villages have

received).

Moreover while the CHWs main functions are related to pro

motive andpre^entive aspects, the village community almost

in his curative abilities. Thus

invariably is more inter sted

in the village, albeit

the CHW ends up as another practitioner

partial Government support, The training programmes of CHWs ar

take into account regional and cast

also not flexible enough to

community based differences in perceptions towards health. Thu

perceptions (with are u

The tendency is to solicit support for any health programme from

the village 'sarpanch" or other infleuntial members of the village

which modtsareas means the "high" caste and landed sections. A

similar modus operand! is applied whle choosing the CHW "acceptab

to all sections" from the village community. This almost invariab

means excluding the landless and poor peasants, who form a bulk

of the population and are most in need of health services,

rom

decision making process.

The dificiencies enumerated above in CHW scheme are questions

if community participation is

which require to be faced squarely

theprobelem is the question

to be the desired goal. Central to

of acceptance by our village comm nities of the concept of

at intoruducing this concept

preventive medicine. Today attempts

' through curative servi

are carried out by initially gaining entry

offered as the “carrot” to

In other wdrds curative services are (---while preventive

esnure to be acceptability of the programme,

services are sought to be introduced through the "back door".

Such subterfuge, which starts by not takinc the local community i

confidence, cannot bring about any significant deg ee of communit

participation.

. .

It needs to be recognised that communities are priman y

of theutter inadequacy

interested in curative services because

ceived/ and rightly/ so

of these services. As result this is pe

Can the people befaulted for such a p

the immediate necessity;.

caption when majority of them are denied access to.even very rudi

Moreover the functioning of programmes. a

atproviding p reventive carehasnot shown to thepeople the advanta

It is only whe, from their own exper

ges of preventive medicine,

preventive servicesthat one can

people realise the advantages of

tary curative services.

expect a shift in perception.

.

Thus to sum UP, for any tangible changes to takeplace in th

field of health, radical redemarcation of priorities m the whol

health care delivery system ha e to be initiated.

Hard politica

decisionsto greatly increase spending on health care have to

be taken. for the Primary Health Care system to function adequa

ft has to be made answerable t

local bodies.

Tftis in turn woul

require steps to democratisethe functioning of panchayat system

14

leaps and bounds.

From a

meager 0.14 Crores in the First Plan

went up to 409 Crores in the

Fifth Plan, 1426 Crores in the Six

and finally to a

proposed 3256 Croees in the Seventh Plan. Yet

birth rate has remained static at

around 33 per 1000, for the l

decade.

How then is the

continued increase in expenditure on f

planning to be justified?

tually the basic problem

yiuDiem lies

in the

the inverted

lies in

inverted logic that

falling birth rate

development. The

rate preceds

preceds socio-economic

socio-economic development.

experience in countries all over

over the

world has

shown that exactl

has shown

the world

the reverse is true. The family planning programme as it stands

today, is another example of attempting to find technological

solutions to social problems which require societal measures.

Moreover, the family planning programme with its fetish for targ

Pieces an added burden on the health care delivery network, whic

it is ill equipped to carry. As a result there is a further

whittling down of the already meager relief that the primary hea

care system provides.

As noted in the case of other vertical

programmes, the family planning programme too needs to function

an integrated manner with the rural health scheme.

CRISIS IN PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY;

Though there continues to be a greater emphasis on the curat

aspect of health even this area is plauged by a variety of proble

This is examplified by the total anarchy which prevails into the

production and supply of medicines.

Only 20% of the people have

accessto modern medicines. There are perennial shortages of

essential drugs, while useless and hazardous drugs flourish in th

market. There are 60,000 drug, formulations in the country, thou

it is widely accepted that about 250 drugs can take care of 95%

of our needs.

The market is flooded with useless formulations li

tonics, caugh syrups and vitamins while anti-TB drug production i

just 35% of the need. While 40,000 children go blind every year

due to Vitamin-A Deficiency, Vitamin-A production was just 50% of

the target in 1986-87.

The production of Chloroquine has shown

decline in recent years, at a time when 20% of the people are

a

15

s

turnover of the Pharmaceutical Industry has increased by leaps

and bounds and today, globally, it stands next only to the

Armaments Industry. The growth of the Industry has been

phenomenal in India too. From a turnover of Rs.10 crores in 1947

it rose to Rs.1050 crores in 1975-76 and today stands at

Rs.2350 crores.

In spite of the growth in Pharmaceutical production in the

country, however, morbidity and morality profiles for a large

number of diseases continue to be distressingly high. It is thus

clear that there is a dichotomy between the actual Health '’needs'

of the country and drug production.

It is also obvious that a me

arithmetic increase in Drug production cannot ensure any signific

shift in disease patterns. Hence, if this dichotomy between drug

production and disease patterns is to be resolved, some drastic

measures are called for to change the pattern.

The Pharma:eutica1 Industry in India has developed along the

lines followed '.n developed countries, The reasons for this are

First, the Industry in India being in the grip of MNCs,

drug production las naturally followed the pattern of production

in the parent ccn ntries of these MNCs. No attempt has been made

twofold.

Secondly, the India/Drug

assess to actuc'. needs of the country.

’ ‘

, who

Industry caters principally to the top 20% of our population,

have the purchasing power to buy medicines. ■Lhis is also the sec

which is amenable to manipulationsby the high power marketing str

of the drug cor panies. Moreover, in this section, disease patte

do roughtly cotrepondent to that in developed countries. The

industry ?*,s thuc able to ueglect the needs of 80% of the populati

andyet make subs tantial profits.

^t sees no ned to change its pa

of drug product! c n and thrust of its marketing strategu.

One is

unlikely to see <iny change ir. these areass unless the industry is

compleeled to cl.enge by stringent regulatory measures, by the ^ov

Government.

drugs differe f.rom other consumer goods, in that

while the co: turners have a direct say in the purchase of consumer

goofd, such !.,' not case for Irugs. Drugs are purchased on the

Further

16

large the curriculam has very limited relevance to the existin

situation in the country. On this the report of the Medical

Education Committee, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare say

’’The present system of medical education has had no real impac

medical care of the vast majority of the population of India”.

is thus the not suprrising that what doctors prescribe have li

relevance to the disease patterns in the country..

what is probably even worse is the fact that doctrs,

afte

passing out of teachinginstitutions, have almost no access to

unbiased dnnrg information. As a result their prescribing habit

moulded by information regularly supplied by drug companies.

his information for obvious reasons, is manipulated to support

production pattersn of the drug industry. ^o ulti tely what

medicines the patients gets is determined not by his actual nee

but by what the drug companies feel are necessary to maximise t

profits.

INCORRECT PRIORITIES OF GOVERNMENT

The problem is compounded by themanner in which the governm

^he most important crit

makes estimates for drug requirements. T.

used for this purpose is based on ’market needs *f Given the sc

related above, this can neveif reflected the actual drug needs o

country.

- Today, a need is created forvarious inessential dur

by salves prmotion campaigns conducted by drug companies. ^hus

ecample Vitamins and tonics in large doses are prescribed laon

antibiotics. This is a ’created need’, though vitamins and ton

are sameof thehighest selling products in themarket.

India accounts for about 18% of the world’s population, many

factures andmarkets only 2% of the total global drug production,

out of which barely 30% are essential, to meet the drug needs

to drug to treat 24% of the total global morbidity, '^hefollowir

table gives us some idea of the shortfall in essential drug prod

(Though the gravity of the situation ismore than waht the table

cates, as the demand estimategiven for 1982-83-based on governmer

figures are a gross under estimation. Moreover for 1986-87 the

Chemicals Ministry has even stopped giving gurues for demand est

ChlorampheniGol

Ampicillin

Vitamin-A

300

111.46

300

200

MMU 77

142.27

52.00

3 80

140

INB (anti Tuber

cular)

T

250

288.40

Chloroquine

T

200

194.57

325

410

177.61

Dapsone (Anti Leprosy)T

200

86.90

60

25.51