RF_COM_H_2.2_SUDHA (1).pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

x;/ -

--

4,.;-..,,

.....

RF_COM_H_2.2_SUDHA

'

*RF_COM_H_2.2_SUDHA

i~s ■ T-'SE?

RF_COM_H_2.2_SUDHA

a..

Health Care Budgets in a Changing Politicar

Economy

■rr

Ravi Duggal

A meaningful analysis of recent health budgets can only be made in the context of the direct and indirect

encouragement given by the state to the growth of the private sector in health services. First, the slowing down

of state investment in the hospital sector and the subsidies, soft loans and duty and tax exemptions offered; second,

the creation of a market for modern health care through the setting up of PHCs and cottage hospitals in the

rural areas; and third, the consistent expansion in highly qualified medical personnel who could not be absorbed

in the state sector.

*

I

WHILE the 1980s saw the beginning of a

process for economic change towards greater

liberalisation and privatisation of the Indian

economy, the 1990s have accelerated the

pace of change under the umbrella of

structural adjustment. This has also meant

increase in borrowings with the debt burden

burgeoning and making interest payments

a rapidly increasing proponion of the state

budget. Tliis state of the economy has its

bearing on state spending, and social sectors

are the first to get the axe. The little hope

which remained of a welfare state evolving

in India is now fading away.

It must be indicated at the outset that I ndia

has always had-a very large private medical

sector, especially for non-hospital care.

While the colonial state developed the

hospital sector at a slow pace, individual

private practice expanded without any state

intervention. Investment in the private

hospital sector was very small until the mid1970s, after whicn it spread likean epidemic

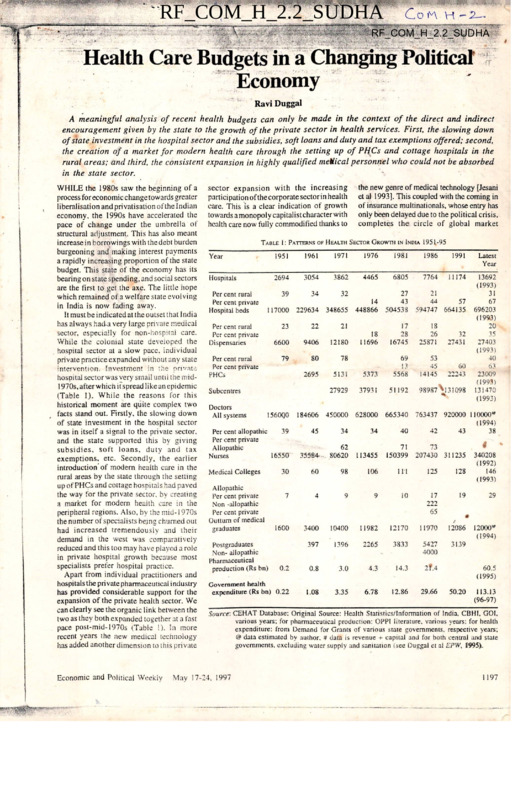

(Table I). While the reasons for this

historical moment are quite complex two

facts stand out. Firstly, the slowing down

of state investment in the hospital sector

was in itself a signal to the private sector,

and the state supported this by giving

subsidies, soft loans, duty and tax

exemptions, etc. Secondly, the earlier

introduction’of modern health care in the

rural areas by the state through the setting

up of PHCs and cottage hospitals had paved

the way for the private sector, by creating

a market for modern health care in the

peripheral regions. Also, by rhe mid-1970s

the number of specialists being churned out

had increased tremendously and their

demand in the west was comparatively

reduced and this too may have played a role

in private hospital growth because most

specialists prefer hospital practice.

Apart from individual practitioners and

hospitals the pri vale pharmaceutical i ndustry

has provided considerable support for the

expansion of the private health sector. We

can clearly see the organic link between the

two as they both expanded together at a fast

pace post-mid-1970s (Table I). In more

recent years the new medical technology

has added another dimension to this private

Economic and Political Weekly

sector expansion with the increasing

participation of thecorporate sectorin health

care. This is a clear indication of growth

towards amonopolycapitalistcharacterwith

health care now fully commodified thanks to

Table 1: Patterns

of Health

the new genre of medical technology [Jesani

et al 1993]. This coupled with the coming in

of insurance multinationals, whose entry has

only been delayed due to the political crisis,

completes the circle of global market

Sector

Growth

in India

1951-95

Year

1951

1961

1971

1976

1981

1986

1991

Latest

Year

Hospitals

2694

3054

3862

4465

6805

7764

11174

39

34

32

14

117000 229634 348655 448866

27

43

504538

21

44

57

594747 664135

23

22

21

6600

9406

12180

18

11696

17

28

16745

18

26

25871

32

27431

79

80

78

2695

5131

5373

69

13

5568

53

45

14145

60

22243

27929

37931

51192

98987^131098

13692

(1993)

31

67

696203

(1993)

20

35

27403

(1993)

40

63

23009

(1993)

131470

(1993)

Per cent rural

Per cent private

Hospital beds

Per cent rural

Per cent private

Dispensaries

Per cent rural

Per cent private

PHCs

Subcentres

Doctors

All systems

I560Q0

39

Per cent allopathic

Per cent private

Allopathic

16550

Nurses

184606 450000 628000 665340 763437 920000 HOOOO4*

(1994)

34

34

40

42

43

38

45

71

73

150399 207430 311235

355-84

62

80620

113455

30

60

98

106

ill

125

128

7

4

9

9

10

17

222

65

19

29

1600

3400

10400

11982

12170

11970

12086

397

1396

2265

3833

5427

4000

3139

12000''’’

(1994)

0.2

0.8

3.0

4.3

14.3

2f.4

Government health

expenditure (Rs bn) 0.22

1.08

3.35

6.78

12.86

29.66

Medical Colleges

Allopathic

Per cent private

Non -allopathic

Per cent private

Outturn of medical

graduates

Postgraduates

Non- allopathic

Pharmaceutical

production (Rs bn)

340208

(1992)

146

(1993)

60.5

(1995)

50.20

113.13

(96-97)

Source: CEHAT Database: Original Source: Health Statistics/lnformation of India. CBHI. GOI.

various years: for pharmaceutical production: OPPI literature, various years: for health

expenditure: from Demand for Grants of various state governments, respective years:

@ data estimated by author. # data is revenue + capital and for both central and state

governments, excluding water supply and sanitation (see Duggal et al EPW, 1995).

May 17-24. 1997

1197

consolidation of the health sector in India.

This is like Alisha Chinai’s ‘Made in India’

which had busted all popularity charts and

supposedly given Indians apndc in the ‘Made

in India’ label but most are not aware that

this album was produced and recorded in

London, UK! This is what globalisation of

India is in reality - the label will become

Indian but the surplus will be appropriated

by the new genre of imperialists.

Apart from private sector expansion and

corporatisation, another strong and

undesirable character of the health sector

in India is its neglect of rural areas where

still over 70 per cent of the population

resides. Today there are over 11 lakh

registered medical practitioners of vanous

systems in the country of which 60 per cent

are located in cities. In case of modern

system (allopathy) practitioners as much

as 75 per cent are located in cities and

especially metropolitan areas. For instance,

of all allopathic medical practitioners

registered with the state medical council in

Maharashtra55 percent are in Mumbai city

alone which has only 12 per cent of the

state’s population. The main reason, thus,

for the underdevelopment of health care in

rural areas is this vast rural-urban gap in

the provision of and location of health care

resources. With rural areas being

underserved two things have happened - a

large number of unqualified people have set

up medical practice and the rural population

exerts pressure on facilities in the cities and

towns thus affecting the efficiency and

capacity of the latter. In spite of planned

development over the last 45 years the state

has failed in narrowing the rural-urban gap,

and in fact at the behest of imperialist

influence it has promoted strategies for rural

health care which cause more harm than

good for the health of the people. Under

the umbrella of community health the state

has given rural areas third rate health care

through its PHCs and that too only

preventive (immunisations) and promotive

(family planning) care; curative care which

is the main demand of the people has been

ignored in terms of investment and

allocations and hence people in rural areas

are left to the mercy of the exploitative

private health sector which more often than

not in rural areas comprises unqualified

providers. It is important to see the health

budgets in the above context for making a

meaningful analysis.

While there is a lot of talk about the latest

budget (1997-98) being remarkable, it has

not really diverted from the path it has been

traversing now for a number of years. While

the salaried class and the bourgeoisie may

have a lot to cheer in terms of saving taxes

and having larger disposable incomes, there

is nothing in the budget to bring cheer to

the toiling masses. Social sector in

terventions like health care, education,

housing, etc, which are regarded as important

Table 2: An Overview

of Central

and

State

Health

|

1989-97

(hi rupees billion)

Budgets

1988-89 1989-90 1990-91 1991-92 1992-93 1993-94 1994-95 1995-96 1996-97

RE

RE

Category

1 Total central

health budget. 10.12 10.28

2 GOI’s own

expenditure

3.78 4.47

3 Disbursement

to states and

6.34 5.81

UTs JI-2)

4 Health expendi

ture of states # 34.77 39.60

5 Per cent central

component in

state budget #

14.7

18.2

(3/5 x 100)

12.73

13.82

17.22

21.48

22.95

26.08

28.72

4.92

5.56

6.33

7.43

9.47

12.77

14.71

7.81

8.26

10.89

14.05

13.48

13.31

14.01

45.86

50.83

56.62

66.69

74.28

85.38

94.42

17.0

16.2

19.2

21.1

18.1

15.6

14.8

Notes: # The state government expenditures are only from 25 states (excluding UTs) and exclude

capital expenditures, hence the actual percentage of central component should be less by

about 0.5 to 2 .

Source: 1 Expenditure Budget 1996-91, Vol 1. GOI, July 1996. 2 and 4 Report on Currency and

Finance, RBI, various years.

Table . 3: Selected

Public Health

Expenditure

Ratios . All India , 1981-95

1980-81 1985-86 1991-92 1992-93 1993-94 1994-95 1995-96 1996-97

RE

BE

Year

Health expenditure as

per cent to total govern

3.29

ment expenditure

Expenditure on medical

care as per cent to total

43.30

health expenditure

Expenditure on disease

programme as per cent

12.96

to total health

Capital expenditure as

per cent to total health

7.54

expenditure

Total health expenditure

11.89

(Rs bn) - Revenue

Including capital

expenditure

12.86

3.29

3.11

2.71

2.71

2.63

3.29

3.29

37.82

26.78

27.66

27.46

25.75

NA

NA

11.69

10.59

10.84

10.41

9.51

NA

NA

8.45

7.78

4.03

4.47

4.27

3.66

4.00

27.15

52.01

62.04

71.83

78.67

97.93

108.60

29.66

56.39

64.64

75.18

82.17

101.65 113.13

Source: CEHAT Database; Original Source: up to 1985-86, Combined Finance and Revenue

Accounts, Comptroller and Auditor General of India, respective years, other years.

Demand for Grants, respective states, various years. The percentage for capital expenditure

is based on revenue + capital total whereas for others it is as a per cent of revenue

expenditure. NA = not available, RE = revised estimate.

.. .

1198

advocating and supporting programmes it

considers to have national importance, and

with control over a major chunk of tax

revenues it can twist arms of the states to

accept its policies and programmes.)

When the central government presents its

budget there is a lot of euphona and expectation

- reliefs in taxes, excise and customs duties,

defence spending, interest burden, subsidies.

The middle classes and business look

forward to the budget eagerly but the same

enthusiasm is not shown in the case of state

and local-government budgets/expenditure

which affect their lives more closely. In fact

there is a complete lack of concern for the

social sector allocations. Even the media

ignores this and highlights only special

schemes or concessions which the finance

minister announces in his budget speech like

the ‘cheap’ hospitalisation policy for the low

income groups announced in the 1996-97

social levellers and help blunt inequities in

society continuc to be neglected. This despite

the promise of the current government of

assuring basic minimum services by 2000

AD. which include 100 per cent coverage

for safe drinking water in rural and urban

areas, 100 per cent coverage of primary

health care services in rural and urban areas,

universalisation of primary education, etc,

among other basic needs [GO1 1997). It

must be noted here that al I the basic minimum

needs being talked about are state subjects

and the allocation of the centre is a very

small proportion. Hence even real increases

in allocations by the centre (often linked to

new schemes) may have a negligible impact,

unless the state governments take some

radical measures on their own. (This is not

to say that the centre has no influence; in

fact with a small proportion of funding the

centre dictates policies in terms of

.

Economic and Political Weekly

...

May 17-24, 1997

...... .r-.'

■

■

a >

......

J

'

*■

'•r'"

'

■

■

•

5

:

2

t

2

a

1

3

3

✓

7

)

3

d

budget or the opening up of health insurance

to the private sector in this year’s budget.

It is important to note that the central

health budget in itself has a very limited

scope. It includes expenditures on central

government-owned hospitals, dispensaries,

the CGHS (health insurance for central

government employees and their families),

medical research (support for ICMR and

allied institutions) and medical education

(central government colleges). Apart from

this the budget also includes the centre’s

contributions and grants to various health

programmes of national importance like

control and eradication of communicable

diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, leprosy,

AIDS, as well as support for the family

planning programme (almost entirely

centrally funded) immunisation, blindness

control, etc. The larger part of health care

budgets come from state and union territory

governments’ own resources or from their

share of revenues disbursed by the centre.

On an average during the last decade the

centre’s contribution (grants and plan fund

shares of special programmes) has been

about 17 per cent to the overall state health

budgets. Table 2 gives an overview of

budgets for the last one decade.

It is evident from Tables 2-6 that state

governments are clearly the dominant

spenders on various health care programmes.

However, given the lamentable state of

affairs of public health services/institutions

and their inability to meet demands of

citizens, it is also clear that allocations to

the health sector are both inadequate and

inefficient. Further, it is also evident that

there is a declining trend in public health

expenditures and when this is viewed in the

context of the introductory remarks above

it becomes apparent why the private health

sector has such a strong hold of the health

care market.

Declining

7

3

)

3

ie

re

je

?7

Health

Expenditures

The state’s commitment to provide health

care tor its citizens is reflected not only in

the inadequacy of the health infrastructure

and low levels of financing but also in declini ng

support to various health care demands of the

people, and especially since 1980s from when

began the processof liberalisation and opening

up of the Indian economy to the world

markets. Medical care and control of

communicable diseases arc crucial areas of

concern both in terms of what people demand

as priority areas of health care as well as

what existing socio-economic conditions

demand. As with overall public health

spending allocations to both these subsectors

also show declining trends in the 1980s and

1990s. This increasing disinterest of the

state in allocating resources for the health

sector is also reflected in investment

expenditure with very large decline in capital

expenditures during the 1990s.

Further, when we look at expenditures

Economic and Political Weekly

■

.

■

A45

'Mm '.

'

on Health

by States

, .

Table 4: Revenue Expenditure

1985-96

(per Cent of Total Government Revenue Expenditure)

’

"

1985-86 .

1991-92

1992-93

Union government

Afo/or States

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Gujarat

Haryana

Jammu and Kashmir

Karnataka

Kerala

Madhya Pradesh

Maharashtra

Orissa

Punjab

Rajasthan

Tamil Nadu

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

Other States

Arunachal Pradesh

Goa, Daman and Diu

Mizoram

Pondicherry

Himachal Pradesh

Manipur

Meghalaya

Nagaland

Sikkim

Tripura

All India

0.52

0.45

0.42

045

0.42

6.61

6.75

5.68

7.51

7.00

7.61

6.60

7.85

6.69

5.97

7.38

7.24

8.11

7.70

9.75

8.92

5.82

5.23

5.66

5.42

4.19

6.37

5.96

6.92

5.78

5.25

5.94

4.32

6.85

6.72

6.00

7.31

5.87

5.57

5.87

4.79

4.56

6.87

6.44

6.29

5.48

5.33

5.63

5.78

6.64

5.73

5.81

7.55

5.75

5.14

6.24

5.09

3.60

7.71

6.56

7.13

5.65

5.34

6.00

5.32

6.34

6.64

5.48

7.15

5.63

6.00

6.89

5.21

2.90

6.20

6.39

7.44

5.55

4.67

5.00

5.33

6.97

6.59

5.38

6.58

5.85

8.22

6.80

9.11

7.89

6.15

9.20

6.96

4.03

6.53

3.29

6.28

8.33

5.21

8.91

7.24

5.74

6.73

4.17

6.01

5.54

3.11

6.37

8.10

5.10

7.93

7.73

6.01

7.19

5.64

7.87

4.97

8.07

8.08

5.24

7.51

5.39

6.10

5.16

2.71

6.39

7.52

4.99

8.03

8.19

4.54

7.33

4.78

6.78

5.10

2.63

Year

6.81

4.90

2.71

1993-94(RE) 1994.95 (b 'e )

Notes: * - Not available. RE = Revised Estimate; BE = Budget Estimate

Source: CEHAT Database; Original Source; Same as Table 3.

on National

by States

Table 5: Expenditure

Disease Programmes

(As Percentage of Total Health Expenditure)

Year

1985-86

1991-92

1992-93

Union government

Major States

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Gujarat

Haryana

Jammu and Kashmir

Karnataka

Kerala

Madhya Pradesh

Maharashtra

Orissa

Punjab

Rajasthan

Tamil Nadu

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

Other States

Arunachal Pradesh

Goa, Daman and Diu

Mizoram

Pondicherry

Himachal Pradesh

Manipur

Meghalaya

Nagaland

Sikkim

Tripura

All India

4.47

5.41

6.56

4.93

$

17.00

18.77

10.90

14.09

20.75

3.10

10.02

12.33

11.25

16.03

15.84

13.55

11.91

2.89

13.52

8.14

17.29

9.90

16.85

11.91

15.17

11.55

12.24

14.58

18.09

9.41

11.75

13.04

15.95

18.79

7.26

10.34

13.76

15.33

5.37

3.78

10.63

11.95

12.84

8.53

9.10

12.13

18.60

9.93

5.28

4.57

9.90

11.81

12.46

10.18

8.89

11.61

18.83

9.37

5.96

5.29

9.34

11.26

11.33

6.48

8.66

11.65

16.51

9.20

5.58

5.98

8.84

11.87

10.98

6.90

8.18

6.20

17.35

9.18

23.82

6.92

13.67

9.90

12.86

16.88

13.06

13.88

10.38

16.20

11.69

9.98

4.85

11.00

8.96

10.92

18.38

14.32

16.16

8.68

6.23

10.59

13.21

5.67

11.19

8.84

13.04

17.66

5.60

12.81

8.70

11.40

11.73

5.13

11.83

8.97

11.24

4.50

3.10

12.66

7.64

8.86

10.41

4.04

16.62

8.66

9.42

9.51

9.32

9.49

10.84

1993-94(RE) 1994-95 (BE)

Notes: * = Not available, RE = Revised Estimates; BE = Budget Estimates; $ = 1994-95 (BE) union

government breakup not available.

Source: CEHAT Database; Original Source: Same as Table 3.

May 17-24, 1997

1199

I

across states not one state shows a

significantly different trend in spite of the

fact that health care is a state subject under

the Constitution! This only goes to show

how strongly the central government

influences the state’s financing decisions

and that too with average grants of less than

10 per cent of the state’s health budgets,

very similar to how international agencies

with even smaller grants exert large

ideological influences.This lackof initiative

on part of state governments to meet

demands of the people is in part due to the

tight grip that the centre has over Plan

resources, which are also largely investment

expenditures. Thus the mechanism of‘planned’

development is used by the centre to make

states tow their line even when the states may

have opposition governments in power.

Under structural adjustment since 1991

there has been further compression in

government spending in its efforts to bring

down the fiscal deficit to the level as desired

by the World Bank. The impact of new

economics unleashed on people comes via

income and prices and affects people through

final consumption and/or employment, and

for the poorest sections the development

expenditures like IRDP. JRY, health care,

education, housing and other welfare are

crucial in the context of the existing overall

life chances available to such sections. There

is clear evidence that expenditures on such

social programmes are declining in real terms

and its benefits are accruing to fewer people.

For instance the GO1 budget expenditures

have declined from 19.8 per cent of the GDP

in 1990-91 to 16.58 per cent in 1993-94 and

the central health sector has been even more

severely affected [Tulasidhar 1993]. The

states’ share in health expenditure has

increased and that of the centre declined

drastically, and especially so for the centrallysponsored disease control and other national

programmes which are mostly of a preventive

nature. If the states do not pick up the added

burden of allocating additional resources for

these programmes then tuberculosis, malaria.

AIDS, leprosy, etc, would be plaguing the

Indian people more severely.

The situation regarding medical care

expenditures, which are the responsibility

of state governments, is even worse. The

decline in these expenditures have been

much more severe and this has affected

particularly the poorer sections of the urban

population. The cutbacks within this account

are on commodity purchases such as drugs,

instruments and other consumables. Patients

in public hospitals are now increasingly

being given prescriptions to purchase drugs

from outside at their own cost and this too

against the background of drug prices having

increased two to three times during the last

two to fouryears. In many states small amounts

of user charges have been introduced.

on Medical

Table 6: Expenditure

Care by States

(As Percentage of Total Health Expenditure)

Year

Union government

Major States

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Gujarat

Haryana

Jammu and Kashmir

Karnataka

Kerala

Madhya Pradesh

Maharashtra

Orissa

Punjab

Rajasthan

Tamil Nadu

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

Other Stales

Arunachal Pradesh

Goa, Daman and Diu

Mizoram

Pondicherry

Himachal Pradesh

Manipur

Meghalaya

Nagaland

Sikkim

Tripura

All India

1985-86

1991-92

1992-93

1993-94(RE)

18.49

13.76

14.61

42.23

45.22

48.17

32.85

21.59

52.65

43.65

51.28

37.69

24.99

42.46

50.86

40.78

57.46

25.80

44.65

31.73

28.39

26.86

20.24

32.03

24.53

15.07

29.34

19.88

34.72

15.75

13.14

26.62

19.18

31.31

9.24

12.79

26.46

17.98

24.32

39.11

28.51

25.25

25.34

23.21

28.09

36.44

28.69

37.86

20.93

42.17

28.58

26.61

24.60

35.36

27.59

35.87

30.09

38.93

24.34

44.61

24.34

28.07

21.85

30.72

27.37

43.42

32.33

36.25

22.91

42.14

25.16

26.15

24.17

30.56

25.09

43.52

32.33

37.18

i

62.67

68.22

63.73

71.58

40.52

50.72

50.88

60.15

46.73

66.45

37.82

71.63

49.54

21.72

66.22

25.87

20.88

34.79

42.93

53.03

43.76

26.78

74.00

53.23

19.64

57.85

24.89

68.85

53.35

19.54

55.07

10.14

60.41

54.62

23.17

53.30

26.04

36.62

34.63

38.30

51.48

36.39

27.46

33.86

37.01

46.26

36.28

25.75

49.45

41.92

27.66

Notes: * = Not available, RE = Revised Estimates; BE = Budget Estimates.

Source: CEHAT Database; Original Source: Same as Table 3.

<

1200 |

1994-95 (BE)

I 1.90

.

r

.

.■

*

.

Anecdotal accounts from various states, as

well as data from the performance budget of

the ministry of health in Maharashtra reveal

that the net impact of introduction of user

charges and issuing of presenptions to

purchase drugs, injections, syringes,

bandages, etc, from outside have reduced

public hospital utilisation in most districts

- and these would of necessity mean the

poorest. All this ultimately pushes the poor

to increasingly use private health providers,

often at a cost of personal indebtedness, and

makes public health institutions restneted to

those who can exert influence to grab the

restricted but quality services.

Most of these changes have been at the

behest of World Bank whose World

Development Report (1993) focused on

‘Investing in Health’. This report is directed

at third world governments to reorient public

health spending for selective health

programmes for targeted populations wnere

it clearly implies that curative care, the bulk

of health care, should be left to the private

sector. In keeping with this, the Andhra

Pradesh government set up an autonomous

body called the Andhra Pradesh Vaidya

Vidhan Parishad to make the functioning

of taluka level hospitals independent of the

government and flexible to accommodate

interaction with the private sector and is

making further ‘reforms’ with assistance

from World Bank. Punjab, West Bengal

and Karnataka governments have followed

suit to reform the public health sector under

the guidance of World Bank [World Bank

1996]. in fact Punjab has gone one step

further and set up a corporation for managing

public hospitals with private sector

participation, in many states the first steps

towards privatisation have been taken

through contracting out certain services in

the hospital to private bodies. In Maharashtra

two municipal hospitals in Mumbai are being

considered for handing over to private

medical colleges on a lease contract. In a

number of states PHCs and selected

programmes in selected districts are being

handed over to NGOs to run them more

‘efficiently’. All in all, the state is gradually

abdicating responsibility in the health sector

and that too under the garb of a progressive

slogan, ‘peoples’ health in peoples’ hands’.

I

c

c

f

e

P

it

e

b

st

E

fr

P

g

tc

o

tc

at

is

E

ri

cc

fc

ot

in

fi

h«

ec

hi

ft

ca

of

cc

th

sh

fo

Ti

ur

re

as

References

Duggal, Ravi, S Nandraj and A Vadair (1995):

‘Health Expenditure Across States’ (Special

Statistics). EPW, April 15 and 22.

GOI (1997): Economic Survey 1996-97, Ministry

of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi.

Jesani Amar, and S Ananthram (1993): ‘Private

Sector and Privatisation in the Health Care

Services’, FRCH, Bombay.

Tulasidhar V (1993): ‘Structural Adjustment

Programme - Its Impacton the Heal th Sector’,

N1PFP, Delhi.

World Bank (1996): ‘India - A Comparative

Review of Health Sector Reform in Four

States: An Operational Perspective’, Report

No 15753-IN (Draft Version), Washington.

.

Economic and Political Weekly

. Ec

May 17-24, 1997

■

—

Financing Strategies for Universal Access to Healthcare

Ravi Duggal

Introduction

Access to healthcare is critically dependent on how healthcare provision is financed. Countries

that have universal or near universal access to healthcare have health financing mechanisms

which are single-payer systems .11 which either a single autonomous public agency 01 a lew

coordinated agencies pool resources to finance healthcare. All OECD countries, excluding the

USA. have such a financing mechanism. In these countnes. excluding USA, 85% of financing

comes from public resources like taxes, social insurance or national insurance which insure

healthcare to over 90% of the population - even in the USA public finance (Medicare and

Medicaid) constitutes 44% of total health expenditure butone-th*rd of the population in the US is

either uninsured or under insured In fact the USA and Canada stand out in sharp contrast even

though they are neighbours and strong capitalist economies. Canada gives healthcare access to

100% of its population tree of direct payments at 40% ot the cost that USA spends and has health

outcomes better than the USA.

Outside the OECD group a number of developing countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa

like Costa Paca. Cuba, Argentma. Brazil, South Africa, Kenya. South Korea, Iraq, Iran, Thailand,

Sri Lanka etc. too have evolved some form of single-payer mechanisms to facilitate near

universal access to healthcare. It is only in countnes like India and a number of developing

countnes, which still rely mostly on out-of-pocket payments, where universal access to healthcare

is elusive. In such countries those who have the capacity to buy healthcare from the market most

often get healthcare without having to pay for it directly, and those who suffer a hand-to-moudi

existence are forced to make direct payments, often wrth a heavy burden of debt, to access

healthcare from the market.

India is the most privatised health economy in the world and this despite die fact diat direefourths of the country’s population is eidier below die poverty line or at die subsistence level.

Given the political economy of India one would have expected the State to be die dominant

player in both financing and providing healthcare for considerations of establishing equity in

access to healthcare. But this has not happened.

Historically, the Indian State has always been an insignificant player in provision and/or

financing of ambulatory healthcare. Private providers, both modem and traditional, as well as

informal providers, have been dominant players in the healthcare market. While pre-colomal

healthcare was still largely within the i(ijnicuii realm of transactions, the establishment of modem

medicine dunng the colonial penod gradually moved in the direction of commodification. Today

the healthcare system is completely characterised by modem medicine, and healthcare being a

commodity. Even the traditional and non-formal providers, often practitioners of quackery, use

modem medicine in their practice and operate within die market context.

In case of hospital care the transition has been very different. Right from pre-colonial times,

dtroush the colonial period and the post-independence penod upto mid-seventies, die State and

its agencies were the main providers of hospital care There were also significant non-slate

players who set up large chantable hospitals. By 1970's medical education made a major

transition; post-graduation, specialisation and super-specialisation became sought after and the

character of medical practice changed. Specialists on one hand began setting up private nursing

wmes and the corporate sector on the other hand began to show interests in entering tine hospital

sector. Also major

ranges in medical technology, which hastened the process of

commodification of healthcare, made for-profit hospitals a lllcraC ‘Y ^wasachrmn call forthe

had not only become dominant but also within the state sector pnva isa

well as through contractmg out or leasing had become the order o e ay.

It is apparent from the above discussion that the largest source of■financing he3'*car^J;^

out-of.-pocket or self-financ.no. Out-of-pocket spending on healthcare a a

both regressive and iniquitous. Latest estimates from National Accounts Stat stms indie.... u

pnvateTxpenditures on healthcare in India are over Rs. 1300 b.llion ^%ot

;;

pocket. Public expenditures on healthcare are about s. -.

i ion

adds uo to nearly 6% of GDP with out-of-pocket expenses accounting for 72 /o o

>

total health expenditures or 4.3% of GDP. This is a substantia! burden, especially for the poc.

households, th. bottom thme quintiles, which ar. either below poverty toe or at the thresao, o

subsistence, and when rllness stnkes such households ;ust collapse In act to

/

auintiles the ratio of their income financing health expenditures is ~

i Men orv

: e“ e m.nt Sed above Forttor. whrl.th., burden ,s togeiy seif-financed by househe to«,

large proportion ofthrs does not come from current incomes A ver, targe propomon. espec.ally

for hospitalisations comes from debt and sale of assets.

Data from the 5204 Round NSS of 1995-96 (Table 1) reveals that over 40% households borrow csell assets to finance hospitalisation expenditures, and there are very clear class gradients to .

nearlvhSX bottom X quintiles get into debt and/o. sell assets m contrast to one-tfiird1 ofTne

top quintile; mfact m the top quintde tins difference .s supported

and msurance. When we combine th.s data w.th the ratio ot "not seekmg care wh n H inca sect

acute ailments bv the bottom three quintiles in contrast to the top quintile - a difference or ...

times, and the reason for not seekmg such care being inostiy tire cost factor it

evident that self-financing has drastic limits and mitstlf !s the prime cause of most .ll .le-.m

especially amongst the large majonty for whom out-of-pocket mode of financing strains ...r

basic survival.

or some such combmation administered by an autonomous health autiionty which is mandate

law and provided through a public-private mix organised under a regulated system. Canao

Sweden, United Kingdom, Germany, Costa Rica, South Korea, Australia, Japan are

.e .

examples.

Experience from these countnes shows that the key factor m establishing equity m access and

healthcare outcomes is the proportion of public finance in total health expenditures^ Mos^of die.

countries have public expend.tures averaging over 80% of total health expenditures. The greater

healthcare and health outcomes in comparison to China, Malaysia, Soutli Korea, Sri Lan a v. ilk

public finance accounts for between 30% and 60% of total health expenditures.

In India public health expenditures had peaked around mid mneteen-eighties and diereaftcr there

was a declining trend, especially post-structural adjustment period. Tre decade °f®'Sht'esJ

critical period in India’s health development because during tins period not only did tlie puoi c

health infrastructure, espec.ally rural, expand substant.ally but also ma or improvements in hea th

outcomes were recorded After that public investment in health declined sharply and public

expenditures showed a declining trend both as a proportion to GDP as well as in total government

spending. This has also impacted health outcomes, which are showing a slower improvement if

not stagnation. At the same time private health sector expansion got accelerated and utilisation

data from the two NSS Rounds 42nd and 52nd Round, a decade apart, provides ample evidence of

this change. (Table 2 and 3)

Thus, if India has tu improve healthcare outcomes and equity in access then increasing public

health expenditures will be critical. Apart from this the healthcare system will need to be

organised and regulated in the framework of universal access, similar to countries like Canada or

Costa Rica. Ofcourse, India has its own peculiarities and the system that will be designed will

have to keep this in mind. We cannot transplant say the Canadian or Costa Rican system into

India as it is, but we can definitely learn from their expenence and adapt useful elements.

Prescription

Currently India’s health financing mechanism as mentioned earlier is largely out-of-pocket and

one sees a declining trend in public finance. Table 4 provides a profile of the current financing

mechanism in India and Table 5 trends in health expenditures. It is quite evident from the data

that public finance of healthcare is weakening and private expenditures becoming even larger.

First, within the existing public finance of healthcare macro policy changes in the way funds are

allocated can bring about substantial equity in reducing geographical inequities between rural and

urban areas. Presently, the central and state governments together spend Rs. 250 per capita at the

national level, but this is inequitably allocated between urban and rural areas. The rural healthcare

system gets only Rs. 80 per capita and urban areas get Rs. 540 per capita, a difference of over six

times. If allocations are made using the mechanism of global budgeting, as done in Canada, that

is on a per capita basis then rural and urban areas will both get Rs. 250 per capita. This will be a

major gain, over three times, for rural healthcare and tins can help fill gaps in both human and

material resources in the rural healthcare system. The urban areas in addition have municipal

resources, and ofcourse will have to generate more resources to maintain their healthcare systems

which atleast in tenns of numbers (like hospital bed:population ratios and doctor : population

ratios) are adequately provided for. Global budgeting also means autonomy in how resources are

ustd at the local level. The highly centralised planning and programming in the public health

sector will have to be done away with and greater faith will have to be placed in local capacities

Second, the public exchequer even today contributes substantially to medical education to tiie

extent that 70% of medical graduates are from public medical schools. This is a major resource

. that is not fully utilised. Since medical education is virtually free in public medical schools the

state must demand compulsory public service for atlcast three years from those who graduate

from public medical schools as a return for the social investment. Today only about 15% ot such

medical graduates are absorbed in the public system. Infact, public service should be made

55% of

MBBS

mandatory also for those who want to do post-graduate studies ( as many as 5^

------doctors opt for post-graduate studies).

Third, the governments can raise additional resources through charging health cesses and levies

on health degrading products (if they cannot ban them) like cigarettes, beedis, alcohol, paan

masalas and guthka, personal vehicles etc.. For instance tobacco, which kills 670,000 people in

India each year, is a Rs. 35,000 crore industry and a 2% health cess would generate Rs. 700

crores annually for the public health budget. Similarly alcohol, which is much larger and

presentlv generates Rs.25,000 crores in revenues can also bring in substantial resources if a 2%

health cess is levied. The same logic can be applied to personal transportation vehicles both at

point of purchase as well as each year through a health cess on road ax and insurance paid by

owners. Land revenues and propertv taxes can also attract a health cess which is earmarked for

public health (municipal taxes already have an education cess component).

Fourth, social insurance can be strengthened by making contributions similar to ESIS compulsory

across the entire organised sector and integrating ESIS, CGHS etc., with the general public health

system. Also social insurance must be gradually extended to the other employment sectors using

models from a number of experiments in collective financing like sugar-cane farmers in south

Maharashtra paid Re 1 per tonne of cane as a health cess and their entire family was assured

healthcare through the sugar cooperative. There are many NGO experiments in using micro-credit

as a tool to factor in health financmg for the members and their family. Large collectives, whether

self-help groups facilitated by NGOs, or self-employed groups like headload workers in Kerala,

can buv insurance cover as a collective and provide health protection to its members. Atleasi 60%

of the workforce in India has the potential to contribute to a social insurance program.

Fifth, other options to raise additional resources could be various forms ot innovative direct taxes

like a health tax similarto profession tax (which funds employment guarantee) deducted at source

of income for employed and in trading transactions for self-employed. Using the Tobin tax route

is a highly progressive form of taxation which in an increasingly service sector based economy

can generate huge resources without being taxing on the individual as it is a very small amount of

deduction at the point of transaction. What this basically means is that for every financial

transaction, whether cheque, credit card, cash, stock market, forex etc. a very small propomon is

deducted as tax and transferred to a fund earmarked for social sector. For example if 0.025% is

the transaction tax then for every Rs. 100,000 the transaction tax would be a mere Rs. 25 or one

paise per Rs. 40 transacted. This would not hurt anyone if it were made clear that it would be

used for social sectors like health, education, public housing, social welfare etc..

The above are just few examples of what can be done within the existing system with small

innovations. But this does not mean that radical or structural changes should not be done.

Ultimately if we have to assure universal access with equity then we have to think in terms of

restructuring and reorganising the healthcare system using the rights-based approach. Tins

requires a multi-pronged strategy of building awareness and consensus in civil society,

advocating right to healthcare at the political level, demanding legislative and constitutional

changes, and legulating and reorganising die entire healthcare system, especially the private

health sector.

To conclude, we have to stem the growing out-of-pocket financing of the healthcare system and

replace it with a combination of public finance and various collective financing options like social

insurance, collectives/common interest groups organising collective funds or insurance. At

another level the healthcare system needs to be organised into a regulated system that is ethical

and accountable and is governed by a statutory mandate, which pools together the various

collective resources and manages autonomously the working of the system towards the goal of

providing comprehensive healthcare to all with equity.

Projection Of Resource Requirements

The projections we are making are for die fiscal year 2000-2001. The population base is one

billion. There are over 1.3 million doctors (of which allopathic are 550,000, including over

180,000 specialists), 600,000 nurses, 950,000 hospital beds, 400,000' health workers and 25,000

PHCs with government and municipal health care spending at about Rs.250 billion (excluding

water supply).

1. An Estimate of Providers and Facilities

What will be the requirements as per the suggested framework for a universal health care system 9

> Family medical practitioners = 500,000 (one per 2000 population)

> Epidemiological stations = 35,000 (one per 30,000)

> Health workers = 500,000 (one per 2000)

> Health supervisors = 125,000

> Public health nurses = 35,000

> Basic hospitals = 20,000 (of 50 beds each per 50,000 population)

> Basic hospital beds = 1 million

> Basic hospital staff:

> general duty doctor = 120,000

> specialists = 100,000

> dentists = 20.000

> nurses = 360,000

'r- Other technical and non-technical support staff as per requirements (Please note that the basic

hospital would address to about 75% of the inpatient and specialist care needs, the remaming

will be catered to at the secondary/district level and tcaching/tertiary hospitals)

One can see from the above that except for the hospitals and hospital beds the other requirements

are not very difficult to achieve. Training of nurses, dentists, public health nurses would need

additional investments We have more than an adequate number of doctors, even after assuming

that 80% of the registered doctors are active (as per census estimates). What will be needed are

crash CME programs to facilitate integration of systems and reorganisation of medical education

to produce a single cadre of basic doctors. The PHC health workers will have to be reoriented to

fit into the epidemiological framework. And construction of hospitals m underserved areas either

by the government or by the private sector (but only under die universal system) will have to be

undertaken on a rapid scale to meet the requirements of such an organised system.

2. An Estimate of the Cost

The costing worked out hereunder is based on known costs of public sector and NGO facilities.

The FMP costs are projected on the basis of employed professional incomes. The actual figures

are on the higher side to make the acceptance of the universal system attractive. Please note that

the costs and payments are averages, the actuals will vary a lot depending on numerous factors.

(Table A)

3. Distribution of Costs

The above costs from the point of view of the public exchequer might seem excessive to commit

to the health sector given current level of public health spending. But this is less than 3% of GDP

at Rs.600 per capita annually, including capital costs. The public exchequer's share, that is from

tax and related revenues, would be about Rs.400 billion or two-thirds of the cost This is well

within the current resources of the governments and local governments put together. The

remaining would come from other sources discussed earlier, mostly from employers and

employees in the organised sector, and other innovative mechanisms of financing. As tilings

progress the share of the state should stabilise at 50% and the balance half coming from other

sources. Raising ft rther resources will not be too difficult. Part of the organized sector today

contributes to the ESJS 6.75% of the salary/wage bill. If the entire organized sector contributes

even 5% of the employee compensation (2% by employee and 3% by employer) then that itself

will raise close to Rs.250 billion. Infact, the employer share could be higher at 5%. Further

resources through other mechanisms suggested above will add substantially to this, which infact

may actually reduce the burden on the state exchequer and increase contributory 7nare from those

who can afford to pay. Table B gives the break down of how costs would be shared.

Table A: Projected Universal Health Care Costs (2000-2001 Rs. ai millions}

Type of Costs

> Cap itation/salanes to FMPs

(@ Rs.300 per family per year

x 200 mi femilies) 50% of FMP services

> Overheads of FMP services

> Fees for specific services by FMPs

> Pharmaceutical Services

> Total FMP Costs

> Epidemiological Stations

(@ Rs.3 mi per ES x 35,000)

> Basic Hospitals (@ Rs. 10 mi per

hospital x 20,000, including drugs,

i.e.Rs.200,000 per bed per year)

> Total Primary Care Cost

x Per canita = Rs. 440; 2.09% of GDP

x Secondary and Teaching Hospitals,

including medical education and

training of doctors/nurses/paramedics

(@ Rs.2.5 lakh per bed x 3 lakh beds)

> Total health services costs

60,000

20,000

20,000

35,000

135,009

105,000

200.000

440,000

75,000

515,000

10300

> Medical Research (2%)

10300

x Audit/Info.Mgt/Social Res. (2%)

10,300

x Administrative costs (2%)

545,900

x TOTAL RECURRING COST

54.590

X Add capital Costs (10% of recurring)

600,490

> ALL HEALTH CARE COSTS

> Per Capita = Rs. 600.49; 2.86% of GDP

(Calculations done on population base of 1 billion and GDP of Rs. 21.000 billion)

Table B: Projected Sharing of Health Care Costs (2000-2001 Rs. in millions)

Type of Source

State/ Organised Other

Central

Sources

■Muncp. Sector

Govt.

3,000

7,000

25,000

70,000

1. Epidemiological services

5,000

75,000 45,000

10,000

2. FMP Services

15,000

85,000

100,000

3. Basic Hospitals

5,000

20,000

30,000

20,000

4. Secondary/Teaching Hospitals

300

1,000

1,000

8,000

5. Medical Research

300

5.000

5.000

6. Audit/ Info. Mgt.Z Soc.Research

300

7,000

3,000

7 Administrative Costs

590

25,000

4,000

25,000

8. Capital Costs

162,600

28,890

268.000

141,000

ALL COSTS

Rs.600,490 million

5

27

45

23

Perce ages

Table 1: Key Data pertaining to out-of-pocket expenditures, source of finance and for not

mnc

. .

i _____ Nice

OA,

1995-96

seeking

groups, NSS 52* Round,

care across expenditure quintiles iand -social

ii

m

Tv| V flSC/ST Other a TF

I

Richest

Poorest

OPP_________

Rural________

128

138

I 92

i 174

130

94

124

Rs. per episode 77

Urban

160

166

122

| 225

164

141

139

Rs. per episode 95

IPD_________

Rural________

3133 3102

2789

1931 ' 4595

1197

1495

1020

Rs. per Hosp.

Urban________

4303 3921

7470 I 2046

2765

J964

1499

835

Rs. per Hosp.

43

32

42

42

45

Debt and sale 47

of assets (%)

17

18

18

21

Did not seek 24

I

care (°o)______

'"24

22

21

23

I 15

Cost as factor 33

in not seeking

care (O/o)___________________ ______

Source: Compiled from NSS 52nd Round data files

to

Table 2: Per 1000 distribution of hospitalised treatments by type of facility during

1986-87 and 1995-96, India - NSSO__

Urban

Type of

Rural

1986-87

1995-96

1986-87

1995-96

Hospital

(42nd Rd.)

(52nd Rd.)

(42nd Rd.)

(52nd Rd.)

_________

595

418

554

399

Public hospital

8

9

43

48

PHC/CHC

4

5

Public Dispensary

603

431

597

438

All govt, sources

296

410

320

419

Private hospital

70

111

49

80

Nursing home

19

42

17

40

Charitable institution

12

6

17

8

Others

397

569

403

562

All non-govt. sources

1000

1000

1000

1000

all hospitals

Source: NS SO (1998); Report No 441 on Morbidity and Treatment of Ailments

i

-

Table 3: Percentage distribution of non-hospitalised treatments by source of

treatment during 1986-87 and 1995-96, India — NSSO

Urban

Rural

Source of

1986-87

1995-96

1986-87

Treatment

1995-96

42nd. Rd.

52nd Rd.

42nd. Rd.

52nd Rd.

23

15

18

11

Public hospital

1

5

6

P.H.C. /C.H.C.

2

3

2

Public dispen.

2

1

0

0

ESI doctor, etc.

28

20

____ 2£

19

All govt, sources

16

16

15

12

Private hospital

1

2

•

1

3

Nursing home

1

1

0

0

Charitable inst.

52

55

53

55

Private doctor

7

5

10

Others

72

80

_____ 74

81

All non-govt. sources

100

100

100

•100____

Total_____________

Source: NSSO (1998): Report No 441 on Morbidity and Treatment of Ailments

Table 4: Financing Healthcare in India c2003

Estimated users in millions

250@________

Public Jtector^

_____

55_________

Of which Social Insurance

780@________

Private Sector___________

30

Of which social insurance

11_________

Private insurances________

739_________

Out of Pocket

1030

Expenditure (Rs. Billions)

252 (17)*________

________ 30 (2)__________

1250 (83)**

24 H.6)

______ 11.5 (0.8) _______

1214.5 (80)

1552 (100)

Total

(d), Estimates based on National Sample Survey 52nd Round, and Labour Year Book

* Finance Accounts of Central and State Governments, and Labour Year Book, includes

estimated Municipal health expenditures

** Private Final Consumption Expenditure from National Accounts Statistics

S 85% ofprivate insurance is through public sector insurance companies

Figures in parentheses are percentages

Table 5: Health Expenditure Trends in India

Total Public

Private Health

Health

Expenditure

Expenditure

(Rs.billions)

%

GDP

of

(Rs.bdlions)

Year

24.66

0.90

6.78

1975-76

52.84

0.99

12.86

1980-81

90.54

1.19

29.66

1985-86

160.65

0.96

56.40

1991- 92

175.57

0.74

64.64

1992- 93

% of GDP

3.26

4.06

3.61

2.73

2.61

% Private to Total

Health Expenditure

78.43

80.43

75.32

74.01

73.09

1993- 94

76.81

0.98

195.43

2.50

71.78

1994- 95

85.65

0.93

278.59

3.04

76.48

1995-96

96.01

0.89

329.23

3.07

77.42

1996- 97

109.35

0.88

373.41

3.00

77.35

1997- 98

127.21

0.92

458.99

3.30

78.30

1998- 99

151.13

0.94

653.40

4.04

81.21

1999-00

172.16

0.96

835.17

4.76

82.91

2000-01

186.13

0.98

981.68

5.18

84.06

84.90

5.32

1100.00

0.94

194.54

2001- 02

86.36

5.60

1250.00

0.88

197.32

2002- 03

85.62

5.83

1400.00*

0.98

235.06

2003-04 RE

86.52

6.15

1600.00*

0.96

249.28

2004- 05 BE

* testimates by author for private expenditures; RE=revised estimate, BE-budget

estimates

Source: Public: Finance Accounts of Central and State Governments and RBI’s Finances

of State Governments, various years; Private: CSO - GOI - Private Final Consumption

Expenditures, National Accounts Statistics, 200 j

M - X •

*

1

HEALTH AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

Evolution in Thinking on Development.

1950s:

the real purpose of development was to increase national

income, and all it required was an increase in saving and investment.

1970s

GNP growth was not the end, but merely a means to development.

1990s-Today - Purpose of development is not just to enlarge incomes, but to

enlarge people’s choices: these choices extend to quality education,

good health, political freedom, cultural identity, personal security,

environmental protection, community participation and many other

areas of human well-being.

Development must deal with the entire society, not just with the

economy, and people must be at the center of the stage. As such, the

quality and distribution of GNP growth become as important as the

quantum of growth.

Experience in many countries has shown that economic growth

does not automatically translate itself into human development, though

economic growth is essential condition for human development, a link

between growth and human lives must be created through conscious

national policies.

Source: Human Development in South Asia 1997, Mahbub ul Haq

hr

r

l

Health

Economic Growth

Good Health is a crucial part of well-being, but spending on health can also be

justified on purely economic grounds.

Improved health contributes to economic growth:

It reduces production losses caused by worker illness

It permits the use of natural resources that had been totally or nearly

inaccessible because of disease

It increases the enrollment of children in school and improves their

learning ability

It frees resources, that would otherwise have to be spent on treating

illness, for alternative uses.

Health => Poverty Alleviation

The economic gains are relatively greater for poor people, who are

typically most handicapped by ill health and who stand to gain the most from

the development of underutilized natural resources.

Thus, an enabling environment that improves health of the poor also

contributes to poverty alleviation.

Source: WDR 1993

Gains in Worker Productivity

The most obvious sources of gain are fewer work days lost to illness,

increased productivity, greater opportunities to obtain better-paying jobs, and

longer working lives.

EXAMPLES:

Urban Tamil Nadu, India: - Elimination of deformity due to leprosy would

more than triple the expected annual earnings of those with jobs.

The prevention of deformity in India’s 645,000 lepers would have added

an estimated $130 million to the country’s 1985 GNP. This amount is the

equivalent of almost 10 per cent of total official development assistance

received by India in 1985. Leprosy accounted for only a small proportion of

the country’s disease burden, less than 1 percent in 1990.

> Bangladesh: Healthier workers earn more because they are more

productive and can get better-paying jobs.

> Cote d’Ivoire: Daily wage rates are estimated to be 19 percent lower,

on an average, among men who are likely to lose a day of work per

month because of illness than among healthier men.

> Paraguay: Farmers in malarious areas choose to grow crops that are

of lower value, but that can be worked outside the malaria season.

Improved Utilization of Natural Resources

Some health investments raise the productivity of land.

EXAMPLES:

Sri Lanka:- The near-eradication of malaria during 1947-77 is

estimated to have raised national income by 9 per cent in 1977. The

cumulative cost was $52 million, compared with a cumulative gain

in national income over the 31 years of $7.6 billion, implying a

spectacular benefit-cost ratio of more than 140.

Areas previously blighted by mosquitoes became attractive for

settlement; migrants moved in, and output increased.

> Uganda:- Massive migration to fertile, but underexploited, land

followed the partial control of river blindness (onchocerciasis) in the

1950s.

> Onchocerciasis Control Programme:- The estimated cost of the

OOP during the whole of its existence, from 1974 to 2000,

conducted in 11 countries of the Sahel, is about $570 million. Its

estimated internal rate of return is in the range of 16 to 28 per cent.

Benefits through Education

Schooling pays off in higher incomes. Four years of primary education

boosts farmers' annual productivity by 9 per cent on average, and

workers who do better at school earn more.

EXAMPLES

Ghana, Kenya, Pakistan, and Tanzania: Workers who scored 10 per

cent above the sample mean on various cognitive tests have a wage

advantage ranging from 13 to 22 per cent.

> Nepal: Farmers with better mathematical skills are more likely to adopt

profitable new crops.

Poor health and nutrition reduce the gains of schooling in:

enrollment

ability to learn, and

participation by girls.

Children who enjoy better health and nutrition during early childhood are more

ready for school and more likely to enroll.

Health and nutrition problems affect a child’s ability to learn. Nutritional

deficiencies in early childhood can lead to lasting problems: iron deficiency

X

anemia reduces cognitive function: iodine deficiency causes irreversible

mental retardation:

vitamin A deficiency is the primary cause of blindness

among children. Older children are subject to other kinds of disease.

Girls are particularly liable to suffer from iodine or iron deficiency reasons why fewer of them complete primary school. Other health-related

reasons include dropping out as a result of pregnancy and parental concern

about sexual violence. In societies where girls’ education is given lower

priority than boys’, girls miss school because they have to stay home to look

after sick relatives.

EXAMPLES

Nepal:- The probability of attending school is only 5 per cent for

nutritionally stunted children, compared with 27 per cent for those at the norm.

Jamaica:- Children with moderate whipwork infection scored 15 per

cent lower before treatment than uninfected children in the same school.

When retested after treatment, those same children did almost as well as the

uninfected children.

Northeast Brazil: - Inadequately nourished children lagged 20 per

cent behind the average gain in achievement score over a two year period.

Children with bad eyesight lagged 27 per cent behind the average gain over

the two years. Both groups had below-average promotion rates and above-

average drop-out rates.

a

w

China:- A child at the twentieth per centile in height-for-age (a sign of

poor health) averages about one-third of a year behind the grade normally

reached by children of that age.

Thailand:- Children whose height-for-age is 10 per cent below

average are 14 per cent lower in grade attainment.

1

Reduced Costs of Medical Care

Expenditure/investment that reduces the incidence of disease can

produce big savings in treatment costs.

For some diseases the expenditure pays for itself even when the

indirect benefits, such as higher labour productivity and reduced pain and

suffering, are ignored.

EXAMPLES:

Polio:- Calculations for the Americas made prior to the eradication of

polio in the region showed that investing $220 million over 15 years to

eliminate the disease would prevent 220,000 cases and save between $320

million and $1.3 billion (depending on the number of people treated) in annual

treatment costs. The programme’s net return, after discounting at even as

much as 12 per cent a year, was calculated to be between $18 million and

$480 million.

AIDS:- Although it remains much less common in the developing world

than diseases such as malaria, its economic impact per case is greater for

two reasons. It mainly affects adults in their most productive years, and the

infections such as pneumonia, diarrhea, and tuberculosis resulting from it lead

to heavy demand for expensive health care.

*

1

Research in nine developing and seven high-income countries

suggests that preventing a case of AIDS saves, on average, about twice GNP

per capita in discounted lifetime costs of medical care; in some urban areas

the saving may be as much as five times GNP per capita.

Calculations for India showed that, given prevailing transmission

pattern, each HIV-positive person in 1991 would infect one previously

uninfected person every four years. At this rate, there will be six HIV-positive

persons in 2000 for every one in 1991.

If the transmission rate could be slowed to one every five years, that

number could be reduced to only four infected persons in 2000 for every one

in 1991. The corresponding reduction in medical costs, after discounting at 3

per cent a year, amounts to $750 by 2000 for each currently HIV-positive

person in India, or a total saving of $750 million.

Similar calculations for Thailand suggest savings of $1,250 per

currently HIV-positive person, or a potential total saving of $560 million.

vvr

Health mustn’t hinge on wealth

*

mi

>

i.

ume; and two, during the first two

"WT y HEN the “buy one,

There S a great deal Ol

or three days, when patients are

> Jw / fake one free” sales

%/%/ pitch hits the marconceptual Clutter 111 OUr tensive diagnostics and invasive

7 f

ket for healthcare,

x ill

procedures, 'the incentives imi it is time to sit up. “Buy a heart by, pass and take a week’s holiday in

| C„’’

| Goa” or “Get the second bypass

to reduce the length of stay or

at 50% discount” is no longer a

IK. Sujatha Rao

make the prices so unaffordable

! joke. It is on offer today. The

that the patient opts to leave. This

question is that while most of us

it

being

underfunded,understaffexplains why a large number of

would be lured into buying that between the US and Canada are

ed

and

overstretched.

Is

this

gradthe “rich” continue to frequent

account

of

largely

on

the

values

extra pair of shoes we do not

need, how many of us are willing enshrined in their respective con ual veering towards the US model the public hospitals and why US

subsidises the care of all its senior

to have our teeth extracted or stitutions. For the Canadian psy a reflection of our Hinduism wh

citizens, who largely suffer from

ich

is

intensely

atomistic

and

wh

che,

it

is

social

solidarity,

order,

heart cut up only because there is a

chronic diseases, under its

ere

each

lives

and

suffers

in

accor

discount? Is it not reasonable to peace and good governance,

medicare programme.

dance

karma?

with

his

own

assume that those in dire need of while for the US it is personal

rFhe hijacking of the health sec

it

Is

really

true

that

concepts

of

of

happiness

freedom,

pursuit

such services would not only re

tor

by the market fundamentalists

and

equality

social

solidarity

are

spond, but the need for suivival and liberty. And while in both

arguing for more subsidies for the

indeed

foreign

and

borrowed

and

countries

provisioning

of

health

being so great, would do so at any

therefore not relevant to India as private sector, starving public hosfuture cost to themselves or their care services is by private

providers. Canada insures all its seems to have been pointed out by pitals of resources, has been possifamily?

ble because of the absence of a na

This then brings in the ques- citizens — rich and poor — inpa- the then prime minister to a group

i tion of individual vulnerability * tient care and physician services, of agitated women activists in re tional consensus on the values that

' which an Ambani and the rick- while in the US, public finance is sponse to his stand on the famous we need to adopt for ourselves. To

I shaw puller have in common, giv- only for specific target groups. Shah Bano case? Qearly, there is start with, as pointed out by for

i

| ing rise to the most fundamental namely the poor and the elderly. an immense amount of concep mer US president, Biil Clinton, in

principle — is profiteering on the Given the widespread poverty, tual clutter and lack of direction in Hyderabad to a gathering of top

industrialists, do we believe that

sickness of other humans ethical?

there is a higher purpose in life to - w

Can companies be lauded and inmerely making profits? If yes, can

Can

be

and,

there

true

happiness

: dividuals be rewarded the best en

we then agree that those who can

trepreneurial award for increasing

more importantly, social stability

not afford healthcare should be

, profits on the ill health and vulnerdenied it and allowed to suffer and

in a society where a large number

' ability of people who are struck

die? Do we believe that all hu

with the misfortune of falling sick?

mans are not equal?

of

its

members

suffer

want

I These are important issues, ones

As all philosophical principles

that were hotly debated in UK

and disease?

remind us, can there be true hap

l during the 40’s, in Canada and

piness and, more importantly, so

I most of Europe in the 60’s and

cial stability in a society where a

our

intellectual

traditions

and

our

discourse

on

health.

In

jump

70’s, as also in Singapore, Aus

large number of its members suf

tralia during the 80’s, resulting in constitutional pronouncements of ing to ideological positions of pub

fer want and disease? Is it then

lic

is

private

is

good

govbad,

and

it

is

inexplicable

as

to

equality,

all these countries opting for a

uuhv discourse on health

emments are bad and markets are not necessary for turning the dewhy

public

strong interventionist role by the systems'has not followed UK or good, our intellectuals have trivi- bate around and placing the prinstate. And this is the issue that

debate.The

ThedevasCanada and why we are creating a alised

alisedserious

serious debate.

devas- ciples of social solidarity and pubtroubles the conscience of most

Americans, too. as evidenced by system resembling the US.

tation

tation markets

markets have

have caused,

caused, in

in lie accountability in health getting

As

US,

we

too

do

not

of

human

suffering

and

precedence over privatisation an«

in

the

terms

terms

! their constant yearning for the

a further commercialisation of

seem to be troubled by accepting a publ ic spending in the US, have

I Canadian model of health care.

health? A national consensus on

not

even

been

studied.

Instead,

in

Compared to the US, Canada two-tier system, where the rich can

I

some of these issues is important

tellectuals

have

allowed

them’

’

’

access

world

class

health

care

as

] provides universal health care of

- y

for clarity in public policy and for

i the same level of quality at one per their ability to pay while the selves to fall prey to facile argufor

privatisation

values of compassion

ments