ROOL BACK MALARIA GUIDELINE.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

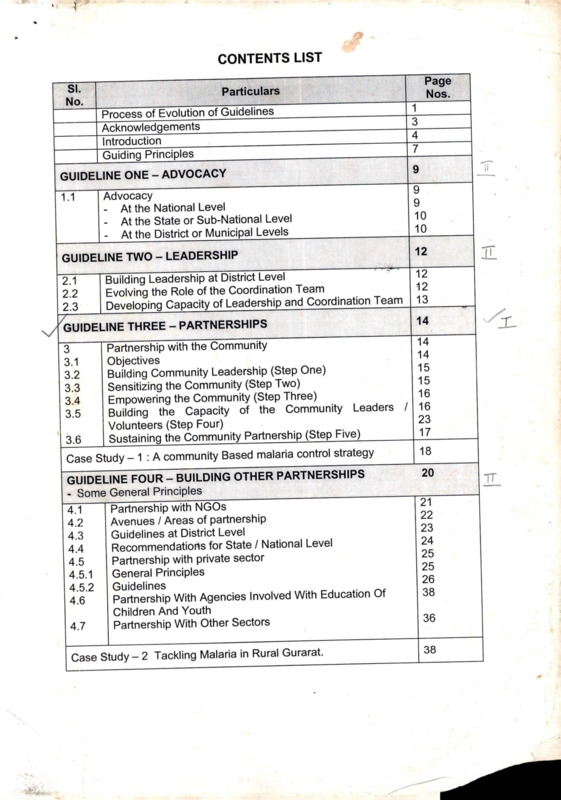

CONTENTS LIST

SI.

No.

Process of Evolution of Guidelines

Acknowledgements

____

Jntroduction_____________________

j~Guiding Principles

GUIDELINE ONE - ADVOCACY

1.1

Advocacy

- At the National Level

- At the State or Sub-National Level

- At the District or Municipal Levels

GUIDELINE TWO - LEADERSHIP

2.1

2.2

2.3

Building Leadership at District Level

Evolving the Role of the Coordination Team

Developing Capacity of Leadership and Coordination Team

GUIDELINE THREE - PARTNERSHIPS

3

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

i

Page

Nos.

Particulars

1

3

4

7

ii

9

9

9

10

10

12

12

12

13

14

14

Partnership with the Community

14

Objectives

15

Building Community Leadership (Step One)

15

Sensitizing the Community (Step Two)

16

Empowering the Community (Step Three)

Building the Capacity of the Community Leaders / 16

23

Volunteers (Step Four)

17

Sustaining the Community Partnership (Step Five)

3.6

Case Study - 1 : A community Based malaria control strategy

18

___

20

GUIDELINE FOUR - BUILDING OTHER PARTNERSHIPS

- Some General Principles__________

Partnership with NGOs

4.1

Avenues

/ Areas of partnership

4.2

Guidelines at District Level

4.3

Recommendations for State / National Level

4.4

Partnership with private sector

4.5

General Principles

4.5.1

Guidelines

4.5.2

Partnership With Agencies Involved With Education Of

4.6

Children And Youth

Partnership With Other Sectors

4.7

21

22

23

24

25

25

26

38

Case Study - 2 Tackling Malaria in Rural Gurarat.

38

36

IL

2

SI.

No.

Particulars

Page

Nos.

TT

GUIDELINE FIVE : COMMUNICATION FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE

39

Organise I EC Strategy and Materials

40

Communication strategy - principles

41

Communication Methods

Innovations_______________________________________ 41

Case Study 3 Evolving a Community Strategy to keep

42

villages Malaria-free.

_____

GUIDELINE SIX : DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT AND TRANSMISSION

CONTROL AT THE COMMUNITY LEVEL

43

Simple Ways for diagnosis and treatment of malaria

6.1

43

How to recognise malaria

6.2

43

What to do

6.3

44

What should be done at the Primary Centre

6.4

44

When to refer patients to a health centre/hospital

6.5

44

Laboratory Diagnosis

6.6

44

Rapid Diagnostic Tests

6.7

45

Treatment

and

follow

up

of

malaria

patients

home

care

6.8

45

Community level

6.9

45

At the Health Centre / Hospital

6.10

46

Malaria in pregnancy

6.11

46

Administrative Level

6.12

47

Medical Audit

6.13

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

.ILL

GUIDELINE SEVEN : MANAGEMENT OF SEVERE MALARIA

7.1

7.2

7.3

7.4

7.5

What is severe and complicated malaria?

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

Physical Examination

Investigations

Management

48

49

49

50

50

GUIDELINE EIGHT : REFERRAL SYSTEM FOR MALARIA

8.1

8.2

8.3

Who should be referred? Criteria for referring malaria cases

Who will and where to refer

What facilities should be available at the referral centre?

52

52

53

GUIDELINE NINE : PACKAGE DELIVERY FOR COMMON DISEASES

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

Definition of Common Diseases for Health Care Package

Package Kit

Preventive drugs / equipment:

Curative:

54

55

55

55

v 47

>

SI.

No.

Particulars

Page

Nos.

///

GUIDELINE TEN : DRUG SUPPLY AND MANAGEMENT

10.1

Management of Drug Supply

57

GUIDELINE ELEVEN : IMPROVEMENT OF HEALTH CARE AT HOME

THROUGH EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN.

58

Identification of key persons

Tm

58

Methods that may be adopted

11.2

GUIDELINE TWELVE : INTER PROGRAMME LINKAGES WITH SAFE

MOTHERHOOD AND OTHER PROGRAMMES.

60

Malaria and Pregnancy

12J

Malaria in pregnancy as part of Reproductive and Child 60

12.2

Health (RCH) ~

Malaria as part of Integrated Management of Childhood 60

12.3

Illness (IMCI)

60

Links with existing health infrastructure

12.4

Malaria related to development projects

61

12.5

GUIDELINE THIRTEEN : MONITORING DRUG RESISTANCE

62

Identifying Sources of Information

137f

62

Information on Failure of Treatment with Anti-malarials

13.2

63

Testing for Resistance

13.3

63

Vigilance for Pv Resistance

13.4

GUIDELINE FOURTEEN : HEALTH MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEM

14

14.1

14.2

14.3

14.4

14.5

14.6

14.7

Health Management Information System

Data Collection System

Analysis of data

Who is responsible?

Coordination with other health sectors

Personnel

Public domain information

Implementation of Computerized HMIS

64

65

65

66

66

67

67

67

ITT

4

Page

Particulars

SI.

Nos.

No.

GUIDELINE FIFTEEN : MALARIA PREVENTION AT COMMUNITY

LEVEL

69

Ts- Malaria Prevention At Community Level

69

Personal protection against mosquito bites

15.1

69

Insecticide treated mosquito nets/curtains

15.2

69

Mosquito repellents

15.3

70

operationalisation

of

use

of

repellents/ITN

programme

in

15.4

different settings

Elimination of mosquito breeding places in and around 71

15.5

houses.

73

Larvae Control

15.6

74

House spraying and thermal fogging

15.7

74

Chemoprophylaxis

15.8

______________

I

74

Malaria vaccine

15.9

GUIDE JNE SIXTEEN : STRATEGY ON ELIMINATION OF BREEDING

PLACES THROUGH COMMUNITY ACTION______________________

Special Strategy On Elimination Of Breeding Places 75

16

Through Community Action

75

Concept

16.1

75

Guidelines

16.2

79

Case Study - 5

16.3

GUIDE JNE SEVENTEEN : EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SURVEILLANCE

17

17.1

17.2

17.3

17.4

Mapping Of Malaria And Geographic Reconaissance (Gr)

Entomological Surveillance

Forecasting and Early Detection of Epidemics

System Surveillance

Behavioural surveillance

80

81

81

82

82

GUIDELINE EIGHTEEN : EPIDEMIC PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE

18

18.1

18.2

18.3

18.4

18.5

18.6

18.7

Epidemic Preparedness And Response

Epidemic

Epidemic Forecasting

Parasite load

Vector Dynamics

Population Dynamics

Ecological Changes

Epidemic preparedness

J1L-.

84

84

84

84

84

84

85

85

—

111

5

GUIDELINE NINETEEN : MAPPING OF MALARIA AND GEOGRAPHIC

RECONAISSANCE (GR)___________________________________ _________

87

Mapping Of Malaria And Geographic Reconaissance (Gr)

19

87

Why Mapping and GR?

19.1

87

Mapping and GR

19.2

87

GR

in

Malaria

Control

19.3

GR to Map Basic Receptivity and for Formulation of Control 87

19.4

Studies

GUIDELINE TWENTY : RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

20

20.1

20.2

20.3

20.4

20.5

Research And Development

Socio-economic studies

Vector Studies

Drug Studies

Epidemiological Studies

Control Strategies

Case Studies - 6

89

89

89

89

90

90

91

7

IL

14

Fo^

1 ■

tSCT I ON

in

GUIDELINE THREE:

PARTNERSHIP WITH THE COMMUNITY

3.1 Objectives

The objective of Roll Back Malaria is to promote the broad participation and

ownership of the community in malaria control. This will be done through the

active mobilization, involvement and participation of the community in

planning, implementation and monitoring of the health programme.

This can be evolved in five steps:

Step one:

Building community

leadership.

Step five'.

Sustaining the

community

partnership.

Step four:

Building community

capacity,

(leaders / volunteers)

I

Step two. Sensitising

the community.

4

>

Step three'.

Empowering the

community.

15

•3.2

BUILDING

COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP (STEP ONE)

1. Identify leadership in the community (this may be village, tribal hamlet

or township)

(a) These would include:

• Formal leaders

• Informal opinion leaders

• Community clubs and organisations - youth, women, farmers,

• Teachers

• Religious and community leaders

• Village health workers / local development workers

• Others in the community who could assume leadership roles.

(b) Proactively increase the participation of women members by involving

women’s groups1.

(c) Ensure adequate representation of marginalised/ minority groups.

2. Evolve the health committee at community level with the involvement of

the people

■

■

If there is a functional health committee or group already, integrate malaria

function with that group.

If a functional committee does not exist then evolve a malaria committee

which can take up other health programmes at a later stage.

3. A dialogue of the district administrator2 with the community leadership /

health committee should be initiated to elicit the participation in the

Malaria Programme.

4 Orient the leadership/committee to the malaria situation and malaria

control to get their help in sensitizing the community.

3.3 SENSITISING THE COMMUNITY (STEP TWO)

Through community level meetings, organised by the identified leadership and or

the health committee, sensitize the community to all aspects of malaria situation

and malaria control.

1. Create awareness of national malaria programme at village/township level and

define the expected role of all members of the community.

2. Emphasise community’s role by stressing:

a) that they are partners in the programme and have their roles and

responsibilities in malaria control, and

b) that their participation will ensure benefits to their community.

1 for example, mahila mandals in India; PKK in Indonesia; and MMCWA in Myanmar

2 for example. District Collector in India and Bhupathi in Indonesia

16

3.4 EMPOWERING THE COMMUNITY (STEP THREE)

1. Initiate a dialogue using participatory approaches to understand the existing

knowledge, attitudes and practices of the community in relation to the malaria

problem.

2. Assess the strengths and weaknesses from the KAP exercise against the

expected behaviour.

3. Create awareness in the community on the causes, signs and symptoms

of malaria and about the treatment and prevention of malaria.

4. Involve them in a planning exercise:

• to survey and identify the local situation.

• to identify the existing resources in the community including volunteers

who could be trained for the programme.

• to identify external resource inputs that will be required, and local

resources that can be mobilised.

• to develop a plan of action for malaria control that could include health

promotion, early diagnosis and treatment, and malaria prevention

activities(including vector control).

• to identify clearly the role of the community and the role of the Health /

Malaria programme team.

5. Facilitate the operationalisation of this plan by

• helping them to implement,

• helping them to monitor, and

• helping them to review and revise the plan of action.

3.5 BUILDING THE CAPACITY OF THE COMMUNITY

LEADERS / VOLUNTEERS (STEP FOUR)

Helping the community to build its capacity for malaria control activities will

essentially mean building the capacity of leaders and local volunteers in a

variety of tasks.

1. To understand all aspects essential for malaria control. These will

include all those aspects included in the box pV Malaria A to Z). The

training / orientation must address all these questions in a simple,

demystified way, using supportive health education and learning aids.

2. To further build the capacity of volunteers/leaders in:

• early diagnosis and treatment

• identification of serious cases and their suitable referral

• community surveillance of malaria morbidity and mortality.

• vector control activities at community level

• communication and mobilisation.

• monitoring and evaluation at community level.

Practical skill development in the context of the local situation will be the

key to success.

17

Malaria AtoZ

a) What is the current magnitude of malaria problem : National / State /

District/Local

b) What is malaria - its symptoms and characteristics for identification?

c) How is malaria caused?

d) Where do mosquitoes come from?

e) Where do they breed?

f) Who are at most risk of suffering from malaria?

g) How can we test for malaria?

h) Where can these tests be done?

i) What can be done to treat malaria?

j) Where is the treatment available?

k) How can we control the mosquitoes?

l) What are the complications of malaria?

m) What should be done in case of complications?

n) What are the protective measures against mosquito bites?

3.6 SUSTAINING THE COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP (STEP FIVE)

Community partnership can be sustained by:

1. Frequent interaction with community, providing solutions to

the problems in carrying out control activities will also sustain

the interest of community in malaria control activities.

2. Ensure that supplies are constantly available (insecticides,

fish, nets, medicines, neem oil, equipment, microscopes,

stain, slides). This will also greatly help the sustainability of

the programme.

3. Encouragement of income generating vector control activities,

e.g., social forestry plantations will also help sustainability of

the community involvement.

4. Incentives for the community from the district administration in the form

of:

a) declaring malaria-free or healthy villages

b) developmental inputs.

“True partnership begins when the community

involved decides what needs to be doneand

particularly what needs to be done first.’*

18

Case Study -1

A community based malaria control strategy

Bissamcuttack, Orissa, 1996

[The Christian Mission hospital in Bissamcuttack, Orissa has been recently involved with tackling the

malaria problem by involving the community from the villages served by the hospital as follows:]

Step One

• We began with helping people to recognise their public health enemy No.1 - Malaria

by sharing with them the MIS data from the government PHC on Morbidity and

Mortality. This prepared the ground for step two.

• We also did an informal survey to ascertain sleep habits and patterns, according to

community, age and gender.

Step Two

•

If the village so desired they invited us to explain to them the basics of Malaria. This

involved almost a full day when we met with as many of them as could get organised

into groups according to gender, age and community. The classes were quite

intensive and based on 4 questions:

1. What is Malaria?

2. How does one get it?

3.

4.

What can we do if we get it?

What can we do to keep from getting it?

•

•

•

We used teaching aids, flashcards, photographs, Neem oil, mosquito nets, synthetic

pyrethroids, etc.

An Oriya pamphlet was also distributed to those who could read.

We stressed environmental methods, neem oil, clothing and nets - as alternatives.

Step Three

*

•

The villages chose the options they wished to pursue. Most opted for Neem oil and

impregnated nets.

• The village decided who will take charge - usually 2 or 3 respected people. They

would be incharge of finalising the order, supervising the distribution and collection of

money. Each village decided on different schedules and modes of payment.

• We supplied nets, taught the method of impregnation and taught 8 principles of using

the net. Our team members stayed over the first night to help sort out ‘teething

problems’.

• We got nets from Raipur and synthetic pyrethroids from Calcutta.

• More than 50% of our investment has been repaid already.

• Our investment had been in terms of time, energy and capital money. The approach

chosen was slow but encouraging.

• We have not raised the question of subsidy because most families spend around Rs.

800-00 a year on Malaria and our nets are cheaper than local shops - so they opt for

it.

To summarise:

Our strategy is an Alternative, people based, village level, sustainable strategy with 3 basic thrusts:

a) Malaria Education

b) Promotion of personal protection measures - all methods including IBNs

,c) Early clinical diagnosis and prompt treatment.

We then did a 2 day workshop for other NGOs to share our experience. The idea is that they will go

home and launch similar village level ‘wars’ against malaria!

Christian Hospital, Bissamcuttack, Orissa.

19

REMEMBER!

RBM is a social movement for better health and poverty alleviation

"RBM is a social movement for better health and will focus on providing access to the poor

who suffer from malaria the most. RBM actions would lead to poverty alleviation. The

community and the private sector would have the opportunity to play important roles in the

delivery of effective anti-malaria interventions, particularly in primary prevention and

treatment of malaria. National plans to roll back malaria should reflect diverse opportunities

and approaches."

Community mobilization

"The program should address health issues arising through enhanced community

awareness and knowledge about disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment, as well as

through local operational research activities. Bottom-up planning should be the core

principle where decision-making and planning capacity will be based at the level where the

problem occurs i.e., local-level planning, disease surveillance, monitoring of program

activities, resource allocation, IEC, training, vector control etc. Epidemiological information

would be analyzed at the local level and used in proactive action in developing evidence

based planning. However, national-level competence and coordinating function should be

retained or developed at the central level during the process of decentralization and

thereafter."

RBM promotes equity in health by focussing on disadvantaged populations

"Malaria primarily affects the poorest people. Children, women and migrants are the main

victims of malaria. RBM will promote health equity by strengthening interventions focussed

on disadvantaged populations and by developing acceptable standards of health care,

focussing not just on disease burden but also on the cost effective interventions."

Improving access to health care

"Because of poor quality public sector facilities and the lack of public confidence in

them, the private sector plays a dominant role in treatment. There is thus a need for

an effective regulatory function to protect public health interest and secure quality

service."

43

GUIDELINE SIX

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT AT THE COMMUNITY LEVEL

6.1

Simple Ways for diagnosis and treatment of malaria

Recognition of signs and symptoms of malaria, especially the serious

forms of it and the actions expected in an episode of malaria of various

actors at home and at village or primary level should be as clear to the

lay people as to the technically trained people. It is this factor that will

make the Roll Back Malaria Initiative to survive the inadequacies of state

funding, collapses of health systems due to war / violence and the

vagaries that people of developing countries often have to face.

It is hence imperative that as many people as possible are trained in

each community who can learn to distinguish malaria from other

illnesses, can help to detect the serious forms of the disease and help

them to reach the nearest and appropriate treatment facility.

6.2

How to recognise malaria

• Every case of fever in highly endemic areas or in persons with a

history of travel to high endemicity area in the past four weeks, should

be presumed to be due to malaria, unless proved otherwise.

• In low risk areas, other causes of fever should be eliminated before

suspecting malaria.

• Classically a group of symptoms consisting of headache, myalgia,

malaise and nausea occur before the first episode of fever.

• Typical, fever due to malaria occurs in cycles occurring every 48

hours. The fever is accompanied with chills and rigors and ends with

profuse sweating. P.malariae fever recurs every 72 hours. This

classical pattern may not be observed in all cases, particularly so in

P. falciparum malaria and treatment failures.

• Atypical symptoms like abdominal pain, vomiting & dry cough may be

present in some patients. Particularly in children, there is no classical

pattern of fever, regardless of the infecting species.

6.3 What to do

• Patients with any of the above symptoms should visit the nearest

health facility centre for diagnosis and treatment of malaria. This

centre should ideally be situtated within a short distance for any

community: short enough that a lone woman with a sick child can

access easily.

44

6.4 What should be done at the Primary Centre

• If facilities for blood smear examination are available locally or

nearby, and results can be obtained within 2 hours, defer treatment

till results are available. Otherwise, treat presumptively for malaria as

per National guidelines.

• If facilities for blood smear examination are not available, treat

presumptively for malaria as per National guidelines. However if

possible, exclude other causes of fever before presumptively treating

for malaria.

6.5 When to refer patients to a health centre/hospital

The following criteria should be able to help a reasonably aware person

to make a judgement about referring a patient for better treatment

facilities.

• Pregnant women and children with high fever (above 39° C).

• Persistent and/or very high fever (fever over 7 days or above 39° C)

Restlessness/Refusal to take feed in children.

Severe pallor or Jaundice

Change in level of consciousness / Convulsions

Signs of shock (cold & clammy skin, thready pulse and rapid

respiration)

• Bleeding from any site / black or brown discoloration of urine (cola

colored urine) / fall in quantity of urine

• Failure to respond to previous antimalarial treatment (if symptoms of

malaria recur within 1 month of treatment)

• Persistent vomiting and inability to swallow antimalarials.

•

•

•

•

6.6 Laboratory Diagnosis

• Blood smear should always be taken or dipstick test done, wherever

possible, for identification of malaria parasite and its species, before

starting treatment. However, it does not mean that treatment should

be delayed for availability of the result of such a test.

6.7 Rapid Diagnostic Tests

• In high risk areas, where facilities for blood smear examinations are

not available, facility for dipstick test for P.falciparum should be

provided at the fever treatment depot for early diagnosis. In case of

limited availability of these kits, priority should be given to children

and pregnant women and seriously ill patients.

• Where dipsticks are made available but health workers are not

available, efforts should be made to train some responsible

45

community members, such as teachers and volunteer health workers,

to diagnose P.falciparum by the dipstick method. It may be noted that

the sensitivity of Dip stick test is about 95% and not 100%.

• Private practitioners should be encouraged to provide facilities for

laboratory diagnosis of malaria.

• In areas where health facilities are not available, NGOs may be

involved in the diagnosis of malaria, particularly by dipstick method.

• In high risk areas, if laboratory test for malaria is negative and fever

persists, the laboratory test should be repeated on 3 consecutive

days.

6.8 Treatment and Follow up of malaria patients Home care (by

family members)

•

Fever should be brought down as quickly as possible with cool

water sponging. Paracetamol, 500mg to 1gm for adults and

10mg/kg per dose for children may be used. Patient should be

given plenty of fluids.

•

Glucose or sugar solutions must be given to drink, particularly to

children and pregnant women.

•

In case of children, continue breast feeding.

•

Seek medical care as early as possible.

6.9 Primary level (community level/DDC/FTD/sub-centre)

• At the Basic Health Facility Centre in the village

• If a presumptive diagnosis of malaria is made, then the local fever

treatment depot (FTD) or other health facilities should be contacted

and patient treated with Chloroquine or other appropriate drugs

(depending on the drug policies already laid out by the malaria

control programme of individual countries).

• There is no benefit of giving Primaquine to all patients in hyper

endemic areas.

• Advise patient / care providers to look for signs of serious illness and

refer the patient to a health centre / hospital .

• Provide supportive therapy as required (Paracetamol for fever and

headache, plenty of fluids etc.)

• Advise patients / care providers about nutrition, home care, the need

for treatment adherence and when to report back.

• In high endimicity areas, where the probability of malaria is high,

algorithms as per national guidelines may be followed for diagnosis

and treatment, (see box at the end of Guidelines 6)

6.10 At the Health Centre/Hospital

. • Diagnosis of malaria should be confirmed and patient treated with

Chloroquine or other appropriate drugs as per the National policy.

• Patients of severe and complicated malaria should be treated with

intra venous (i/v) Quinine infusion or other appropriate drugs like

Quinine, Mefloquine, Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine and Sodium

Artisunate / Arteether as per the national malaria treatment

guidelines.

46

• Chloroquine and Quinine can safely be given during pregnancy

including the first trimester for the treatment of malaria. However

Quinine infusion should be given in dextrose solution to avoid

hypoglycemia.

• Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine combination can be given after the first

trimester of pregnancy up to one month prior to delivery.

6.11 Malaria in pregnancy

During pregnancy, not only does malaria attack more frequently and

severely, but it also worsens women's anaemia and can cause a high

incidence of abortion, neonatal deaths and low birth weight. Effective chemo

prophylaxis in pregnancy effectively protects the women from malaria and

should be given for the entire duration of pregnancy (preferably avoided in the

first trimester because of nausea.

Approved doses of Chloroquine or Quinine may be given in any trimester

of pregnancy for curative treatment of malaria.

Sulfadoxine - Pyrimethamine combination may be given after the first

trimester of pregnancy and upto one month prior of delivery.

Primaquine should not be given during pregnancy (and to infants below

one year).

6.12 Administrative level

• Establish, where possible, a functional drug distribution centre (DDC)

or fever treatment depot (FTD) in each village and urban slum.

• Ensure timely replenishment of diagnostic supplies and antimalarial

drugs.

• Paediatric formulations of antimalarial drugs should be made

available.

• Evolve mechanisms to ensure quality control of antimalarial drugs.

• Training of health workers and volunteers in malaria diagnosis and

treatment.

• Coordination should be ensured between different partners (eg:

private practitioners, volunteers and NGOs) and different programmes

(eg: RCH, IMCI etc) in malaria diagnosis and treatment.

• Local patterns of drug resistance should be monitored by the

specialised teams in order to formulate the local drug policy.

• Development and maintenance of relevant surveillance and reporting

system for monitoring and evaluating malaria situation in the area.

Case definition for reporting should be followed as per the

recommendations of 20th Expert Committee on malaria (WHO).

• Provision of required drugs, preferably in age-group-wise packets,

with instructions in local language.

47

6.13

Medical Audit

To ensure a good quality of care provided to patients with malaria, each

member country in the region should develop a system of medical audit to

build effective mechanisms for ensuring the quality of patient care.

Medical audit is a systematic critical analysis of the quality of

medical care including the procedures used for diagnosis and

treatment, the use of resources and the resulting outcome for the

patient._________________________________

6.13.1 Medical Audit should be carried out in district hospitals with suspected

malaria deaths to begin with. Later it can be expanded to other institutions

and areas. An attempt must be made to introduce it as a necessary

component of good hospital practice in private clinics, nursing homes and

hospitals through professional bodies. Adherence to national treatment

guidelines on malaria and rational malaria care can be promoted through

medical audit and besides ensuring quality care to people, it also goes a long

way in preventing or delaying resistance to antimalarials.

6.13.2 At district level, a committee consisting of district health authority,

public health experts and clinicians not directly involved in the direct

management of the case. The report of the medical audit should be sent to

the concerned authorities for appropriate action. For hospitals, medical audit

committees can be formed by physicians and pharmacists not directly

involved in the case management.

Antimalarial drug policy for the country or region should be

reviewed periodically by an expert committee and changed

whenever required depending

on the sensitivity patterns of

Plasmodium species.

54

GUIDELINE NINE

PACKAGE DELIVERY FOR COMMON DISEASES

It is envisaged that by strengthening District Health System through Primary

Health Care Services we are indirectly strengthening the malaria control

operation in the district. It is in this context that PACKAGE DELIVERY CARE to common diseases is to be incorporated in Roll Back Malaria Program. As

the malaria control activities now are integrated with the general health

services, it would rather be useful to deliver a package of services to the

community related to the- communicable diseases as per the need “of the ’

community. However this packaging of essential care should be defined as

per existing disease prevalence and the felt-need of the community to be

served; availability of manpower (both from government and other sectors);

provision of static health facilities; and not the least, the least care-seeking

behavior of the community. The already existing “Essential Services Package

(ESP)” and the “Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI)” may

be considered wherever useful.

P'

9.1 Definition of Common Diseases for Health Care Package

Since the pattern of endemic diseases and morbidity varies from area

to area, the approach to select the diseases to be addressed for Health

Care Package should be based on area specific pattern of diseases.

Though communicable diseases are common in all parts of the

country, there are certain diseases which have high prevalence and

hence we need to have some criteria to selectsuch diseases for the

delivery of the package. The following criteriajehould be used for

prioritization of health care package.

~~

•

•

•

•

Quantum of morbidity

Complications/Disabilities

Epidemic potential

Amenability in Control , -

Methodology for Selection of Diseases is

• Study of existing records at District level and below

• Special Survey Reports, if available.

• Study of infrastructure including manpower institution.

• Study of the delivery system.

• ^Pattern of local administrative system and community system

It is suggested that about 5 to 6 such diseases may be selected by

following the above criteria.

55

9.2 Package Kit

There is a system of having Drug ^ with^e^ryQMPW^rid

list of the

MPW

drugs supposed to be kept in the kit are givenbelov^5^

Chloroquine tablets and microslides are invariably kept in the kit. This

kit may be revived to see whether it sen/es the purpose aimed for

prevention, control and cure of the disease. An indicative /ist of such •

drugs/ equipment may be:

9.3 Preventive drugs / equipment:

1. Tab Iron & Folic Acid

2. Tab. Chloroquine

3. Vit A solution/capsule

4. Chlorine tablets

5. Disposable pricking needle

6. Gauze /Bandage

8. Microslides

9. Sputum cup

10. Thermometer

9.4 Curative:

1. ORS packets

2. Cotrimoxazole tablets/syrup

3. Paracetamol tablets/syrup

4. Anthelminthics tab./syrup

5. Cough expectorant syrup

6. Amoxycillin tab./cap /syrup

7. Diazepam tab/syrup

8. Tab. Primaquine

9. Tab. Sulphadoxine/Pyrimethamine

10. Tab. Quinine Sulphate

11. Tab. Ergometrine

12. Antispasmodics

13. Anticoagulant tablets

14. Anti-emetic tablets, e.g., Prochlorperazine/Metoclopramide/

Drug information inserts detailing the indication, dosage, side effects and

expiry dates must accompany the drug kit written in easily

understandable language(in local language where possible)

58

GUIDELINE ELEVEN

IMPROVEMENT OF HEALTH CARE AT HOME THROUGH

EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN

Empowerment of women means:

•

•

•

creating an awareness among women through basic knowledge for

prevention of malaria and other common diseases.

Providing adequate information for recognizing the seriousness of the

disease and identifying its possible complications and adopting simple

methods to undertake home care within the family.

This will directly result in early diagnosis and prompt treatment of common

illnesses including malaria.

11.1 Identification of key persons:

For the empowerment of women it is necessary to identify different

groups of women. Depending upon the physio-demographic

characteristics of the area, the women groups can be divided into the

following:

1. Rural

2. Urban slums / laboUr colonies

3. Urban areas

11.2 Methods that may be adopted

A. Rural areas:

• In rural areas women can be empowered through women

members of local bodies. The other organizations and situations

which hold significance in empowering women are

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

Women’s organizations

Religious organizations/social gathering

Weekly markets

IEC material will have to be developed. Street plays / puppet

shows / other sources of entertainment may be used as a vehicle

to provide the necessary education.

• Special groups of women interested and trained in health should

be identified as a trained resource. These groups may include lady

teachers and female members of local bodies, bank and post

offices and may be trained for early detection of malaria also.

•

59

A. Urban slums / labor colonies

•

Knowledge to women in urban slums may be imparted through NGOs /

voluntary organizations and cooperative societies.

A. Urban areas

B. Women in urban areas can be empowered through

♦ Welfare Associations

♦ Women’s development Councils

♦ Women's clubs

♦ Voluntary Organizations involving women (eg: Lions club etc.)

C. The member(s) of these organizations may be trained in imparting

knowledge regarding home care of malaria, who in-turn will train other

women at home. Their training shall include the following thrust areas:

1. Health education and awareness about common diseases

including malaria.

2. Cleanliness, in and around the house including water

management and disposal.

3. Use of preventive measures like use of bed-nets, repellents,

mosquito proofing etc

4. Knowledge and awareness about existing local health

infrastructure.

The home care package given to women may include the following:

1. Fever as a symptom to be taken seriously and presumptive

treatment for malaria to be given preferably after taking blood

smear for malarial parasite.

2. Symptomatic treatment like sponging, plenty of fluids,

antipyretics.

3. Identification of complications like drowsiness, vomiting, low

urine out put, convulsions, which need immediate referral to

the hospital.

4. Pregnant women / infants & children with fever to be dealt

with as a potential emergency and immediate treatment to be

given.

5. Prophylaxis for pregnant women especially in high endemic

areas.

Women involved in social development work including malaria control should be

recognized and honored by the local bodies / NGOs. This would act as an incentive for

involvement of more women.

69

GUIDELINE FIFTEEN

MALARIA PREVENTION AT COMMUNITY LEVEL

There are four main ways to prevent malaria

1. Prevent mosquitoes from biting people by personal protection.

2. Control mosquito breeding by elimination of breeding places

3. Kill adult mosquitoes by house spraying and thermal fogging.

4. Chemoprophylaxis by regular intake of drugs taken to prevent malaria.

Important preventive measures that can be adopted and applied by

individuals and the community are personal protection against mosquito

bites and elimination of mosquito breeding places.

15.1

Personal protection against mosquito bites

• Mosquito nets / insecticide treated mosquito nets and curtains

• Mosquito repellents

• Mosquito coils

• House screening

However, none of these measures can provide full protection against

mosquito bites and the diseases transmitted by them (Table 1).

15.2 Insecticide treated mosquito nets/curtains

A major impact on malaria incidence/mortality following the large-scale

application of insecticide treated mosquito nets (ITN) has been

demonstrated. From the experience gained in the usage of ITN, it has

been observed that to optimize the use of nets the following basic

information is essential:

• Mosquito biting times and site of contact

• Sleeping habits / socio-behavioral practices of the communities to

be

protected.

Unless this information is available and ITNs are found relevant in the control

of

malaria in the area, introduction of ITNs in the programme may not

have the desired results.

Operational aspects including delivery, cost sharing and social marketing of

nets should be investigated to look at feasibilty and self-sustainability.

15.3 Mosquito repellents

Mosquito repellents are effective against outdoor as well as indoor biting

vectors. They could supplement effects of mosquito nets and could be

used more frequently in some high-risk groups such as rubber-tappers

and night hunters.

70

Table 1

Personal Protection

Pleasures_________

Mats

Active Ingredient/

Principle_________

Synthetic Pyrethroids

Mosquito Coils

Herbal/synthetic

pyrethroids

Synthetic Pyrethroids

Insecticide Treated Nets

I Curtains

Vaporizers

Light Traps

Mosquito proofing/

window screening

Mosquito Repellent

Creams

Lotions (DEET)

Eucalyptus Oil

Citronella oil

Protective Clothing

Neem Oil

Synthetic pyrethroids

Light attraction

Mechanical barriers

Likely side-effects

Respiratory/eye problem

including asthma,

itching, rash, etc.

--- do--------■do

-do

Nil

Nil

Herbal /Chemical

Skin irritation or rash

Chemicals

Natural oil

Natural oil

Natural oil

Neem derivatives

Skin irritation

Nil

Nil

Nil

Nil

Note: Effective protection by the repellents (except treated mosquito

nets/curtains) varies from one to four hours in the field in different seasons.

The effectiveness also varies against different mosquito species. All repellents

are more effective against Anopheles (malaria vectors) than Culex (filariasis

and J.E. vectors) or Aedes (Dengue vectors).

15.4 Operationalization of use of repellents/ITN programme in different

settings

The strategy for the sustainable use of these methods at the community level

is as follows:

•

The manager of the malaria control programme, at the District Level will be

overall in charge, working under the purview and guidelines of District

Malaria Society. His/her responsibility will include the procurement and

distribution of repellents and ITNs, and providing back up support and

coordination of IEC and other promotional activities through media,

educational institutions, local government institutions, NGOs, etc.

•

It is recommended that the money received from the sale of the subsidized

items such as nets should be handled by a voluntary agency / NGO/

autonomous society created for the purpose.

•

The monitoring mechanism should be developed according to local

situation for which a committee could be set up, taking representatives

from the community and malaria society.

71

•

Annual evaluation of the programme be conducted by a small committee

with representatives of Malaria Control Programme, community, NGOs,

local Government and experts with social science background.

•

In the distribution and use of mosquito, the priority should be given to

pregnant women, infants and children. The significance of protecting this

vulnerable group should be highlighted through mass media and IEC

activities.

•

Type of insecticide for treating mosquito nets should be decided by the

National Program Managers as per insecticide policy of the country.

•

There is evidence in few countries that repellent formulations are of poor

quality or fake. Therefore quality control checks should be rigidly applied.

•

Herbal repellents like Citronella oil, Eucalyptus oil, Neem oil, etc. should

be encouraged.

15.5 Elimination of mosquito breeding places in and around houses.

A. In the Homes

Major mosquito breeding sites within the house, comprise water

storage container, animal drinking pans and flower vases, roof gutters

and pit latrines. Mosquito breeding in these habitats could be checked

by taking the following preventive measures that need to be made

public knowledge through IEC campaigns:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Water storage within the household should be reduced to a

minimum. However, this may not be possible in areas without a

piped water supply or with intermittent supply. In such cases,

mosquitoes must be mechanically excluded by keeping all domestic

water storage containers covered.

Unwanted standing water should be cleared and the containers

inverted. This is required because mosquito larvae dive to the

bottom of the container when disturbed, and may survive in the

residual water at the bottom of the container.

Choked roof gutters should be cleared of debris, so that rain water

does not stagnate.

Water in animal drinking pans, flower vases, etc., should be

replaced every day.

Sullage should be removed from the premises through properly

designed drains.

Breeding of mosquitoes in pit latrines could be controlled by treating

with malaria oil to cover the water. Another novel method is

placement of polystyrene balls to form a complete physical barrier

over the water to prevent oviposition. These balls are cheap, non

toxic, virtually indestructible and have little attraction or value for

72

people to steal them. Proper design and maintenance of sanitation

systems is essential for eliminating mosquito breeding in these

habitats.

Access of mosquitoes to the interior of the house could be

prevented by screening doors and windows with 18 inch guage wire

mesh screens.

B. Around the House

Mosquito breeding habitats around the house include rainy water

collected in waste articles dumped in vacant plots, underground

cisterns and water storage tanks, wastewater drains, cesspits, and

septic tanks. Mosquito breeding in these habitats could be eliminated

by adopting the following preventive measures.

•

•

•

•

•

•

A thorough search of yards and vacant plots must be made for

discarded articles and rain water collection sites.

Tree holes should be filled with mud or cement to prevent

accumulation of rain water. If solid waste disposal services are

inadequate, articles that may collect rain water could be dealt with,

in other ways, e.g., cans could be cut open and crushed, pans and

trays could be turned over, discarded tires could be cut and turned

over, etc.

Underground cisterns and water storage tanks should be covered

with 18-guage mesh screens. If possible these may be stocked with

mosquito-eating fish such as Gambusia affinis for clean water and

Poecilia reticulata for dirty water.

Drainage arrangements should be made.

Cesspits should be avoided completely and replaced with proper

soakage pits.

Septic tanks should be sealed properly and the vent pipes furnished

with screens. Effluent from the septic tank should be discharged

into a soak away and not into the open.

C. In the Community

In the community, major mosquito breeding habitats comprise spillage

around water supply sources, wastewater drains, storm water drains,

cesspools, ponds and other large water bodies, and low-lying vacant

plots. These habitats should be dealt with as follows:

•

Water spillage around community water supply sources such as

hand pumps, wells, public stand posts, etc., should be checked and

drainage arrangements made.

•

Wastewater and storm water drains should be maintained properly

and dumping of solid wastes into these areas should be forbidden.

73

e

Undesirable water collections in the community could be eliminated

by drainage or filling. Cesspools and low-lying vacant plots are best

dealt with by filling with rubble, earth or refuse. Ponds, borrow pits

and ditches could be filled or, alternatively, these could be drained.

However, small and temporary habitats such as small pools and

puddles, roadside ditches, water-filled vehicle tracks and cattle

hoof-prints may be too numerous and scattered to fill or drain.

•

Mosquito breeding in large water areas could be eliminated through

environmental modification e.g., construction of public irrigation

works that allow control of the water level and shore conditions

(impoundment).

Drainage, filling and impoundment are methods that usually give

long lasting effects. However, these may have other ecological

repercussions and therefore should be undertaken only with expert

advice.

•

•

Houses may be graded periodically on the basis of cleanliness and

action taken by the individual /family on points mentioned in Table

2.

•

Houses with Grade I (best) may be given some incentive,

recognition or free gifts.

15.6 Larvae Control

Larvae control can be carried out if breeding sites are within the flight

range of mosquitoes from the community and breeding sites are limited

and accessible.

The following options can be used:

•

•

• Chemical larvicides like Temephos

• Use of larvivorous fish

• Covering/screening of water tanks

Biolarvicides like toxin formulations from Bacillus thuringiensis

(BT)/Bacillus sphaericus (BS), and insect growth regulators (IGR).

Use of expanded polystyrene beads (EPB) to cover the water surface.

The following points may be considered in the application of the above

methods:

•

Temephos is useful for an instant larval kill and may be used even in

potable water.

•

•

Larvivorous fish are cheap, can be linked with edible fish production and

can provide long term control, if proper supervision is maintained.

Bt and Bs toxin preparations are specific for mosquito larvae, do not kill

predators and are not prone to illicit sale for other purposes. However

resistance develops against Bs.

74

o

®

•

Screening or sealing of tanks may be expensive but is long lasting.

EPS is long lasting in confined sites without wind and overflow.

IGRs are effective at very low doses (p.p.b.) but the effect is not

immediately visible.

15.7 House spraying and thermal fogging

House spraying and thermal fogging should be done by well-trained

health personnel.

Communities should assist in house spraying

operations and fogging by providing volunteers for spraying and

motivating people to accept house spraying.

15.8 Chemoprophylaxis

The community should be educated by the National authority, whether

or not to take Chemoprophylaxis and which drugs to be used for the

same. In special circumstances, Chemoprophylaxis should be offered

as per national guidelines to special groups such as pregnant women in

endemic areas and short-term non-immune travelers to endemic areas.

15.9 Malaria vaccine

An effective malaria vaccine is not yet available although various

candidate vaccines are being developed and tested.

75

GUIDELINE SIXTEEN

SPECIAL STRATEGY ON ELIMINATION OF BREEDING PLACES

THROUGH COMMUNITY ACTION

In the previous section, we have identified step of involving the community in the

Malaria Programme. A special effort must be made as part of the RBM strategy to

involve them in Elimination of breeding places through Community Action as a social

movement.

16.1 Concept:

Mosquito control can be done by eliminating breeding habitats as much as possible.

Community action is required to eliminate breeding places as most of the breeding

habitats are man made and hence it is the responsibility of the community at risk of

vector borne diseases to eliminate the source of breeding.

Methods of elimination of breeding places are:

■ source reduction by eliminating or changing the breeding places to make them

unsuitable for developing larvae.

■ Making the breeding places inaccessible to adult mosquitoes for laying egg.

■ Releasing fish / predators that feed on larvae and pupae.

Operational area principle:

In and around human settlements in an area with a radius greater than the flight range of the

target mosquito species (normally 1.5 -2 kms).

Elimination of breeding places can be on permanent (long term) basis through

environmental, modification or on a temporary basis through environmental manipulation and

release of bio-control agents.

16.2 GUIDELINES

1. Identify target community : rural, urban, development project area, and

stratify if there are diversities in the socio-epidemiological situation of

malaria in the area.

2. Motivate the community through awareness campaign using appropriate I EC

materials.

3. Carefully identify breeding places at community level and map them.

4. Evolve Guidelines for community action to eliminate breeding places

(depending on local mosquito species it and choice of methods for specific

breeding habitats identified locally (see point 13. Also Appendix 2 for further

guidelines for action for different types of situations in rural and urban

areas).

76

5. It is necessary to establish a committee with a chairperson. Active members

such as teachers, postmasters, retired employees, KDS workers, religious

leaders can be included and one person assuming the leadership role.

6. The activities of the committee should include

•

motivation of the community through - interactive meetings

•

identify solutions - including those from community experience

•

involve / motivate other depts and their field workers

> local administration

> sanitation / water supply

> agriculture.department

> fisheries

> PWD

> forestry

7. Small groups with active members can be formed to generate collective force

in filling low lying areas of public interest. Such reclaimed areas can be used for

public use such as playground, etc.

8. School children can be motivated in planting trees in the reclaimed marshy /

low

lying areas in the effort of developing social forestry.

9. Technical skill in masonary, plumbing and constructing of soakage pits need

to

be developed so as to make the community self reliant.

10. It is necessary to ensure the availability of materials such as larvivorous

fishes, EPS beeds, neem oil cake, etc. This can be achieved through

collaborative approach. Information management system will help in

monitoring activities for feedback..

11. Potential avenues can be explored for resource mobilization.

12. Community participation can be sustained some of the by following

measures in the programme:

Planning income generating programmes with vector control as a

byproduct.

■=> Advocating alternative methods

• drainage

• water supply

■=> Legislation and strict enforcement of law

Dynamic leadership and encouraging self reliance

77

|=>

Periodical meetings with the community - to assess the situation, listen to

local problems and be open to suggestions

Promoting socially acceptable and viable solutions that are

• Culturally acceptable

•

Low-cost - available / affordable by all

• Socio-epidemiological need

Involve community right from planning in all stages of programme

Increase popular awareness of the value and the benefits of a malaria

programme.

Minimize conflicts by keeping organizations small; restricting

memberships to persons with harmonious objectives; defining objectives;

in a focussed way and distributing benefits equally.

Facilitate incentive from District Collector for those who involve in

community action.

78

13. A checklist of methods for mosquito control through environmental management

identifying site of action and assigning ‘roles’ and responsibilities is given below in

Table 2.

Table 2

Methods for Mosquito Control through Environmental Management

(Individual / Family / Community / Government)

Action site in

The house

Action to be taken by

The individual, the family

The house

The house

The house

The individual, the family

The individual, the family

The individual, the family

The house

The family, the community, the

local government____________

The family, the community, the

local government

The house

The house

The family, the community

The house

The house

The family

The family

The house_____

The surroundings

The surroundings

The individual, the family

The individual, the family

The family

The surroundings

The surroundings

The surroundings

The family, the community, the

local government

The community, the local

government_____

The community, the local

government_____

The community, the local

government_____

The community, the local

government_____

The community, the local

government_____

The contractor; the building

laws by government__________

The vendor, community_______

The family, the housing society

The surroundings

The family, Community

The surroundings

The family, the community

The surroundings

The surroundings

The surroundings

The surroundings

The surroundings

The surroundings

Action_________________

Cover domestic water storage containers;

tight fitting lids; empty water once in 7 days

Clear unwanted standing water___________

Clean roof gutters/sun shades____________

Replace water once in 7 days in animal

drinking pans, flower vases, etc.__________

Ensure provision of properly designed

sullage drains_____________________

Ensure proper design and maintenance of

sanitation / cover vent pipes with mosquito

netting__________________________

Store used articles and other refuse in

closed containers ______

Screen doors and windows______________

Coolers / air conditioners may have water

changed once in 7 days or a dry day

observed each week___________________

Use mosquito nets and repellents_________

Clean yards and vacant lots_____________

Cover with lid tightly; screen underground

cisterns and water storage tanks, or stock

them with mosquito eating fish____________

Ensure proper drainage

Control water supply sources and ensure

proper drainage_______________________

Provide properly designed waste water

drains and storm water canals____________

Drain or fill undesirable water areas like

cesspools, puddles, ditches, etc, tap pits

Modify large water areas by impoundment

Ensure adequate solid waste collection and

disposal_____________________________

Construction site

Coconut shells to be cut in 4 pieces_______

Mosquito proofing of overhead tanks (OHT),

make OHT accessible for inspection,

demolish discarded tank completely._______

Unused wells may have water covered by

EPS beads, crude oil or larvivorous fishes

Used wells may be covered, screened with

net or use larvivorous fishes

Adapted from : The CAP guide for Insect and Rodent Control through Environmental Management (WHO/UNEP)

79

CASE STUDY- 5

THE PUDUKUPPAM INITIATIVE

!

“The Vector Control Research Centre (VCRC) demonstrated that vector control could be made into an income

generating programme, which is the only way to enlist and sustain community participation in such endeavours.

A success story of a research project, carried out froml980 tol985 in the coastal villages of Pondivherry in

which malaria control was made a by-product of income generating activities is given below:

•

Pudukuppam, a coastal village, in the Union Territory of Pondicherry, was meso-endemic for malaria. The

vector incriminated was Anopheles subpictus breeding in brackish water. The major source for mosquito

breeding was a backwater lagoon (approximately 3 to 5.5 sq. kms.) with the entire water surface covered

with Enteromorpha compressa a filamentous algae facilitating vector proliferation. Removal of algae was

the only practical solution to control the vector breeding. Vector Control Research Centre explored the

economic utility of this algae in paper industry and the technology developed was handed over to the hand

made paper unit of Sri. Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry. The art paper made by the unit using this algae

drawn world wide attention with an excellent export market. This resulted in the creation of a self

sustaining system for algae removal with economic incentives to the local populace. Total elimination of

malaria was thus demonstrated exclusively through community action.

Feasible vector control measures

Source reduction : By the removal of algae which promote vector breeding

Quantity of algae removed in one year: 130 tons

Practical permanent solution : Economic exploitation of algae for manufacturing paper, file

etc.

cover.

Technology developed by : Vector Control Research Centre

Technology transferred to : 1. Hand made paper unit of Sri. Aurobindo Ashram, the pioneers in art

paper manufacture. 2. Hand made paper unit of Mahatma Gandhi Leprosy Rehabilitation Centre.

Benefits to the Community

Total elimination of indigenous transmission of malaria from the village.

Additional regular income to the villagers.

Employment opportunities to the unemployed youths, who collect and sell algae.

Reduction in the cost of production or mottled art paper, file covers, etc

A clean environment”

VCRC project - Pudukuppam

GUIDELINES : Process of Evolution

WHAT?

Guidelines on Roll Back Malaria Programme for South East Asia

Region

WHY?

To develop guidelines that would enable various components of the

Roll Back Malaria Initiative to be understood in-depth and with clarity.

The guidelines deal with strategies and methodologies for involving the

community and civic society at large; with diagnosis, treatment and

referral of malaria patients; and with the systems required at District

level to implement, monitor and review the programme effectively.

FOR

WHOM?

The effort was to evolve simple, generic guidelines for Malaria

Programme officers and their partners primarily at district level.

(Some guidelines were found necessary for the state / national /

regional levels as well so that the programme at district level benefits

from support at higher levels as well, (e.g., structural inputs, human

and material resources inputs, and planning and management

backup). These have been indicated.)

HOW/

WHERE?

1. The guidelines on Advocacy and Community and Partner

Mobilisation were evolved through an interactive, participatory

workshop held in Bangalore, facilitated by the Community Health

Cell, Society for Community Health Awareness, Research and

Action, Bangalore (CHC) from 9-11th December 1999. (It also drew

up from an interactive, participatory process report entitled

“Towards an Appropriate Malaria Control Strategy" that was

facilitated by the Society and VHAI, New Delhi, in 1997).

I

2. The Guidelines on Strengthening of District Health System for

Implementation ^foLjmplementatiorb of the RBM Initiative were

evolved at a workshop of past and present experts conducted by

the Indian National Anti-Malaria Programme (NAMP) Directorate

from 27th to 29th December 2000 at NAMP Directorate, Delhi.

3. The Guidelines for Simple Ways for Diagnosis and Treatment of

Malaria were developed by experts invited by The Post-Graduate

Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh from 3r

to 5th Jan 2000.

All guidelines were finally reviewed and revised in the context of the

South Asian diversity and restructured in an informal consultation at

WHO-SEARO New Delhi on 18-21 Jan 2000.

The guidelines were then integrated, edited and standardised by a

team of three consultants at CHC, Bangalore in June - July 2000.

I

2

WHO?

1. The participants of the Bangalore Workshop included resource

persons from academic and research centres, field NGOs, NGO

support groups, and citizens groups.

The group was

multidisciplinary with multi level experience in health care and

control

of

communicable

disease

programmes

(See

Acknowledgements).

2. The participants of the New Delhi workshop were mainly past amd

present senior officials from the National Anti-Malaria Programme,

and also had representatives from the Railways, Armed Forces

Medical

Services,

Industry

and

from

NGOs.

(See

Acknowledgements).

3. The experts on malaria involved in the Chandigarh workshop were

mainly academics from various disciplines like parasitolgy,

medicine, public health and also had participants from the local

health authorities and NGOs. (See Acknowledgements).

4. A group of consultants from WHO-SEARO and the region revised

the three guidelines to suit the pan-South East Asian Region at the

Delhi Consultation. (See Acknowledgements).

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

0.^0

List of participants of the Bangalore workshop organised by CHC :

Dr. V.P. Sharma; Dr. Rajaratnam Abel; Dr. Sunil Kaul; Dr. C.M. Francis;

Dr. Thelma Narayan; Dr. Ravi Narayan; Dr. V. Benjamin; Mr. S.D. Rajendran;

Dr. Rakhal Gaitonde; Dr. M.V. Murugendrappa; Dr. P.N. Halagi; Prof. N.J. Shetty

Dr. T.R. Raghunatha Rao; Dr. P. Jambulingam; Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy; Dr. K.

D. Ramaiah; Dr. S.K. Ghosh; Dr. Sathyanarayana; Dr. S.N. Tiwari;

Dr. A.K. Kulshrestha; Mr. R.R. Sampath Dr.K. Ravi Kumar; Dr. Mira Shiva ;

Dr. Mani Kalliath; Dr. Pankaj Mehta ; Dr. B.S. Paresh Kumar; Dr. Daniel;

Dr. J. Fernando; Dr. V.R. Muraleedharan; Dr. Prabir Chatterjee; Dr. Rajan Patil;

Dr. Biswaroop Chatterjee; Dr. H. Sudarshan; Dr. Prakash Rao; Dr. Anton Isaacs;

Mr. Suresh Shetty;

List of partcipants of Delhi workshop held by NAMP at NAMP Directorate: |

Dr Shiv Lal; Dr N Dhingra; Dr PB Deobhankar ; Dr J P Gupta; Col Basappa;

Dr Amrish Gupta; Dr S Pattanayak; Mr Rajesh Gehlot; Dr R Sonal; Dr Aruna Srivastava;

Dr Neena Valecha; Dr S P Misra; Dr T Adak; Dr Nagraj; Dr S K Aggarwal;

Dr. JC Gandhi; Dr R S Sharma; Dr P K Phukan; Dr Rajaratnam Abel;

Dr G P S Dhillon; Dr Sunil Bhat; Dr D Sen Gupta; Dr Kiran Dambalkar;

Dr B N Nagpal; Dr NL Kalra; Dr Bossaiya; Dr Sunil Kaul; Dr Mohanti;

Shri. C Krishna Rao; Dr P N Sehgal; Dr Kuldeep Dogra; Dr B K Borgohain

List of participants of Chandigarh workshop held by PGI, Chandigarh:

Prof S C Varma; Prof N Malla; Dr V P Sharma; Dr R C Mahajan; Dr V K Monga;

Dr T Adak; Dr R M Joshi; Dr M L Dubey; Dr R Sehgal; Dr Sunil Kaul;

Dr Rajaratnam Abel; Dr Archana Sud; Dr S K Ghosh; Dr Khosla; Dr N Valecha; Dr

Bhatti; Dr V P Sharma;

The guidelines were reviewed in WHO-SEARO and further modified and edited

with the participation of Dr. V.P. Sharma - WHO-SEARO, Dr. Ravi Narayan Community Health Cell, Dr. Rajaratnam Abel - RUHSA Department, CMCVellore; Ms. Tavitian-Exley (Myanmar); Dr. B.N. Gultom (Indonesia), Ms.

Jyotsna Chikersal, Mrs. Harsaran Bir Kaur Pandey (Nepal); Mr. V. Alexeev, Mr.

Omaj M. Sutisnaputra, and Dr. Sunil Kaul - CHC Associate; Dr. Sawlwin; Dr. A.

Mannan BangaliTDr. P.B. Chand; Dr. G.P. Dhillon; Dr. Hadi M Abednego; Dr. N.

Kumara Rai; Dr. Harry D Caussy; Dr. MVH Gunaratne.

WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONTRIBUTIONS AND ACTIVE PARTICIPATION

OF ALL OF THEM.

Dr Ravi Narayan, Dr. Rajaratnam Abel, and Dr. Sunil Kaul specially helped with

the final editing and integrating of the guidelines. There support is specially

acknowledged.

'

4

GUIDELINES FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF ROLL BACK

MALARIA IN SOUTH EAST ASIA REGION

Introduction

Malaria. People of the world’s poor communities face many threats to their well

being. 40% of the world’s population is at risk of malaria and the disease is a

particular burden for the poorest countries.

There are as many as 500 million cases of acute malaria in the world each year - as

many as 5% of them causing severe illness associated with time away from work or

studies. The risk of malaria is a constraint to the economic development of

communities, regions and nations.

Roll Back Malaria Initiative. In 1998, Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland, Director-General

of the WHO launched The Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Initiative against malaria. RBM

emphasises evidence-based strategies, community level action, partnership between

governments and development agencies, and a reformed response from all of WHO.

It recognizes that sustained success in rolling back malaria inevitably calls for

development of health sector so that they can address a range of priority health

problems. The RBM Initiative seeks to mainstream efforts to roll back malaria

throughout the range of community-level health activities being taken forward by

societies at risk of malaria and is expected to evolve into a social movement on a

global scale.

Within countries, the Roll Back Malaria movement will be backed by governments

and development agencies, NGOs and private sector groups, researchers and

media working in partnerships. The same partners will be organized as a global

partners.

The global Roll Back Malaria partnership has an overall goal of halving malariarelated deaths throughout the world by 2010; the strategy builds on the 1992

Amsterdam global malaria control strategy; with the following six elements:

1. Enhanced diagnosis and treatment of malaria (eg., new diagnostics test,

universal access to treatment, combination drugs);

2. Disease transmission control (cost effective integration of vector control tools eg.,

insecticide treated nets, selective vector control, bio-environmental methods);

3. Enhanced surveillance (rapid response, border malaria, and monitoring process);

4. Health sector development (eg., decentralization, health equity, package delivery

care, changing role from implementors of malaria control to leadership, regulation

and coordination);

5. Community mobilization (empowerment of communities,

planning and ownership); and

evidenced-based

6. Advocacy (forum for advocacy, strategic investments eg., mapping, new drugs

and vaccines, regional support networks eg., drug policy, rapid response, etc.,

health impact assessment, research on reform in health system).

5

Malaria in South East Asia. Malaria continues to be one of the most serious public

health problems in the South-East Asia region. 85% of the total population in

Southeast Asian countries is at risk of malaria, with 35% living in moderate to high

risk areas.

Malaria in South East Asia - Situation Analysis

❖ In South East Asia Region - there are about 3 million (25-26 million

clinically suspected) malaria cases annually.

❖ Malaria in Asia is unstable and causes epidemics and high morbidity.

❖ An estimated 1,202.5 million people or 85% of the total population of SEA

region are at risk of malaria. About 90% live in moderate to high risk of

malaria in India, Indonesia, Myanmar and Thailand.

❖ Chloroquine resistant P. falciparum is reported from all endemic countries

(except DPR Korea); nearly 400 million people live in areas with risk of

contracting drug resistant malaria. Sulfa-Pyrimethamine resistance is also

reported from all endemic countries except Sri Lanka and DPR Korea with

an estimated 140 million population at risk. Multi-drug resistance P.

falciparum is highly prevalent on the Thai-Cambodia and Thai-Myanmar

borders.

❖ Deteriorating epidemiological indices are associated with drug resistance

and operational problems.

❖ In this region 80-85% malaria cases are reported from India and bulk of the

malaria deaths (55-65%) from Myanmar.

❖ Malaria has adverse effects on economic and social development. Malaria

has been called the single biggest cause of poverty in some countries.

Morbidity caused by malaria reduces family earning by 12% and a

weakened workforce brings down productivity.

❖ The process of development itself contributes to the spread of malaria. As

roads are built, forests cut down, new mining areas opened, habitats which

favour the breeding of mosquitoes, expand. This is very common in the

SEA region.

6

Simple guidelines have been developed to implement the six elements of the Roll

Back Malaria. These guidelines address the health sector development leading to

advocacy and the community mobilization.

The RBM is different from previous efforts to fight the disease. While drawing on the

strengths of past experience in malaria control, it focuses on political commitment,'

community empowerment, inter sectoral linkages and partnerships with the

community; voluntary agencies and NGOs; and the private sector involving both

health and development related programmes.

The focus is on finding local solutions to local problems while drawing on potential

resources outside the health sector. With this aim in mind, The Roll Back Malaria

project emphasises decentralization and district level planning with the full

involvement of the community and other partners.

The National Malaria Control Programme then assumes a role of leadership,

facilitation, co-ordination, regulation and not of sole implementation.

RBM - the New Initiative - What is New?

1. RBM is a social movement for better health and poverty alleviation.

2. RBM plans are country driven, evidence based and adapted to local

realities.

3. RBM promotes health equity by focussing on disadvantaged

populations.

4. RBM solicits effective partnerships within and outside WHO.

5. RBM plays the role of leadership, regulation and coordination.

6. RBM activities mainstream into health sector development.

7. RBM is an integrated approach to address malaria and other

common diseases.

8. RBM is a pathfinder for health and human development.

9. RBM is for high level of advocacy for change.

10. RBM promotes research and development for new tools."

■

7

Guiding Principles

RBM draws on the Primary Health Care (PHC) strategy and aims to strengthen the

existing district health systemffor the sam^. It also identifies that early diagnosis and

treatment cannot be made unless common women and the community at largej

understands the basics of malaria and has access to medical aid for all kinds of

common ailments one of which is malaria.

Mobilisation and advocacy are therefore deeply embedded in the Primary Health

Care approach. This is done through the emphasis on

.

i. Community participation

I

ii. The use of appropriate technology .

j