RF_CH_7.1_SUDHA.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

SURVIVAL

VANAJA RAMPRASAD

he recent announcement by

the Government of India to

intervene in five different

sensitive areas of people’s

lives through technology

missions, includes the programme

of immunisation. This echoes the

scale of enthusiasm pronounced at

the international level as a social

movement. The State of the

World’s Children 2986, a UNICEF

annual feature, begins its rhetoric

by claiming—‘Immunisation leads

the way’. It continues to pronounce

that several nations have doubled

and trebled their levels of immun

isation against the vaccine prevent

able diseases.

However, somewhere along the

line ^isolation, in which the prog. ramme of immunisation is envis

aged, the technology mission is

likely to miss the wood for the

trees. It appears that the task has

been given the misplaced honour

of playing the principal role in

child survival and health care

without taking into account the

fundamental biological and human

aspects of it.

What does the immunisation

package consist of? Four vac

cines—the DPT (diphtheria pertus

sis tetanus), BCG (bacillus calmette

guerin), polio and measles—

against six major diseases—

T

Aga

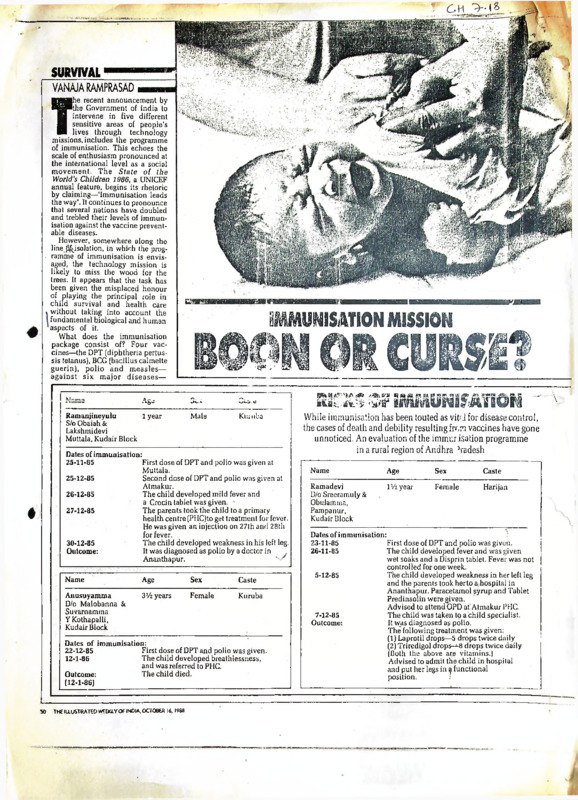

Ramanjineyulu

1 year

S/o Obaiah &

Lakshmidevi

Muttala, Kudair Block

IMMUNISATION MISSION

BOON OR CURSI?

tk.r

Cu. a

Male

Ktunba

Dates of immunisation:

25-11-85

First dose of DPT and polio was given at

Muttala.

25-12-85

Second dose of DPT and polio was given at

Atmakur.

26-12-85

The child developed mild fever and

a Crocin tablet was given. The parents took the child to a primary

27-12-85

health centre (PHC)to get treatment for fever.

He was given an injection on 27th and 28th

for fever.

The child developed weakness in his left leg.

30-12-85

It was diagnosed as polio by a doctor in

Outcome:

Ananthapur.

'

Name

Age

Sex

Caste

Anusuyamma

D/o Malobanna &

Suvarnamma

Y Kothapalli,

Kudair Block

3>/2 years

Female

Kuruba

Dates of immunisation:

22-12-85

First dose of DPT and polio was given.

12-1-86

The child developed breathlessness,

and was referred to PHC.

Outcome:

The child died.

(12-1-86)

SO

THEIU.USTRATCOWEEtU.YOftNOIA,OCTOe£R 16. 1988

^^^HMKUNISATION - V

While immunisation has been touted as vit-'J for disease control,

the cases of death and debility resulting from vaccines have gone

unnoticed. An evaluation of the immurisation programme

in a rural region of Andhra ,’radesh

Name

Age

Sex

Caste

Ramadevi

D/o Sreeramuly &

Obulamma,

Pampanur,

Kudair Block

iWyear

Female

Harijan

Dates of immunisation:

23-11-85

First dose of DPT and polio was given.

26-11-85

The child developed fever and was given

wet soaks and a Disprin tablet. Fever was not

controlled for one week.

5-12-85

The child developed weakness in her left leg

and the parents took herto a.hospital in

Ananthapur. Paracetamol syrup and Tablet

Predinsolin were given.

Advised to attend OPD at Atmakur PHC.

7-12-85

The child was taken to a child specialist.

Outcome:

It was diagnosed as polio.

The following treatment was given:

(1) Laprotil drops—5 drops twice daily

(2) Triredigol drops-^-8 drops twice daily

(Both the above are vitamins.)

Advised to admit the child in hospital

and put her legs in a functional

position.

'

J

diphtheria, pertussis (whooping lysis, when subsequently they are the 30 years since independence

has been much slower in the

cough), tetanus, tuberculosis, exposed to poliomyelitis virus.

The nutritional status of the host 30 years preceding independen

poliomyelitis and measles respec

tively—that .iffect a large per cent before' immunisation is also an ce.

It is evident from the poignant

of Third Wo Id children have been important factor. Immunocompe

advocated to form the package. tence is compromised by severe reports of death and debilitation

Each of these vaccines has to be malnutrition. The body’s ability to that the newly propagated strategy

administered under careful condi cope with infection is reduced for survival using such medical

tions to realise maximum efficien with poor nutritional status. In technology without the corres

cy.

•isolation, immunisation does not ponding efforts for socio-economic

The most important of the con take into account the importance of change and equitable distribution

ditions is s’orage of the vaccine these factors. Environmental mea of resources, has a close resemblance

and the cold chain that is main sures against disease transmission to the much criticised family plan

tained during the time of adminis and the reduction of exposure cus ning model that has been advo

tration of the vaccine. (Vaccine is tomarily involve the provision of cated to control the population of

an immuno-biological substance clean drinking water, institution of the country.

designed to produce specific pro safe disposal of excreta and im

tection against a given disease.)

proved personal and community Invisible benefits

The immune response is net hygiene besides ensuring adequate

entirely"Arrce~lrom~the risk o< nutrition. The huge resources set What has not been openly acknow

adverse reactions, especially those aside for the operationalisation of ledged by the international interest

resulting from septic conditions an immunisation programme are to thrust immunisation on the

due to faulty sterilisation of the- not without their opportunity Third World is that it is a lucrative

25 million dollar-a-year business

equipment and microbial contami costs.

for firms in the industrialised

nation. Use of improperly steril

countries. According to WHO’s

ised syringes and needles carry the

<#tsible Risks

own estimates, about 85 per cent of

hazard of hepatitis virus and

The poor information base in the ‘cold chain’ equipment and pro

staphylo and streptococcal infecWill the government’s

. tions. Medical researchers like country rarely documents the ducts used to keep vaccines safe

wlDr Sathyamsla have documented negative impacts of immunisation are produced in the industrialised

immunisation mission

facts to prove that the increasii g [ "ogrammeS on high risk children world, mainly in Denmark, Luxreally ensure greater

i incidence of polio in areas whe e ci poor and deprived families in umburg, the US, Sweden and

large amom.cS of polio-vaccine are rural areas. Vaccines have at times Japan.

protection against

Vaccines lose potency if exposed

administered annually is due o 1 .ft children debilitated. In some

disease?

the intramuscular injections which Li.es, they have even resulted in to heat and light and must be

death.

While

the

technology

mis

stored below 8’C while tetanus and

- predispose the children to parasion advertises immunisation as a DPT vaccines must not be allowed

new miracle for disease control, to freeze. The 3 M company of the..

u'S is the sole supplier of chc.nicaiName

Caste

Age

Sex

i. ;en'crippled or killed by immun-ii ly treated cards that warn whether

isation go unpubiicised. An eva- the vaccine is usable or not. Each

Nagar.iju

1 Year

Male

Boya

h ation of the universal immunisa- year it ships 1,50,000 cards nt a

S/o Na. asimhulu &

tTm programmehn a rural region of cost of three dollars each. Similar

Venkafalakshmanna

Andhfa~~Pradesh has recorded ly, one can name several firms

Madigubba,

cases of debility and death induced from Denmark, France, Sweden

Kuda;r Block

by vaccinations (see charts):

and Britain that will stand to be

While one is bombarded with nefit. In the next five years, India

Dates of immunisation:

tie rhetoric of guaranteed success expects to spend Rs 2300 million

25-11-85

1

First

dose of DPT and polio was given

of the mission and the internation for immunising 85 per cent of the

25-12-85

Second dose of DPT and polio was given.

al agencies in Delhi, the reality of children and 100 per cent of the

The child got high fever, and was given wet

26-12-85

rise lies in the invisible distant mothers. According to the ministry

soaks and a Disprin tablet: fever was not

viLages whereK children are ex of health, the estimated expendi

controlled.

posed to the hazards of being crip ture on syringes and needles alone

The child could not move both his legs.

27-12-85

pled or killed by the technocratic is Rs 325 million and Rs 820

The child was taken to a hospital.

28-12-85

ap. roach to health care. Technoc million on vaccines.

Outcome:

It was diagnosed as polio in both legs

ratic interventions have anyway

The technocratic approach of the

and left hand.

never been central to bringing technology mission will ensure

health care to people.

that the invisible costs to high-risk

I: may come as a surprise to children or, on the other hand, the

ma ly that in spite c. the fact that invisible benefits to international

Caste

Sex

Age .

Name

most medical technologies were economic interests will never

not available in India in the early reach the public in an open and

Boya

Female

14 months

S Anthamma

yea s of this century, death rates honest way. Hidden beneath the

D/o Verriswamy &

begin to decline from as early as technology mission’s preoccupa

Obulamma

1923.

tion with immunisation as an ex

Sheikshanapalli,

"he facilities and services of clusive panacea for child survival

Urvakonda Block

medical technology were extended lie the sad stories of many children I

to lha general population only after who are victims of technocratic 1

Dates of immunisation:

E3

India gained independence in insensitiveness.

First dose of DPTiand polio was given.

21-11-85

1947. If technology had made an

The child had mild diarrhoea.

impact on the health status of the This is one of a series of articles

Onset of fever, diarrhoea, vomiting,

22-11-85

population there should have been concerning Survival. Any queries

symptoms of malnourisnment

a sharper decline in t.ie death rate regarding these articles and the

Paracetamol, an anli-diacrhoea tablet

Treatment:

in li e period after independence. issues dealt with herein may be

and oral rehydration ih-iapy were given.

On tie contrary, the figures reveal addressed to Lokayan, 13 Alipur

that .he decline in the death rate in Road, Delhi 110 054

{

THE ILLUSTRATED WEEKLY OF INDIA, OCTOBER 16. 1988

St

iH-rui.zzATiOir

DMJBITY

12.1

When antigens arc introduced into tlx body by infection with

o disease or through immunization, the body responds by manufacturing

antibodies to protect itself against then. An individual becomes

immune or dovclopcs immunity when his body has a-, sufficiently high

level of antibodies against a specific disease or infection. Such

an individual lias developed a kind of resistance to the disease.

.

There arc two types of immunity: •

' :

1• Natural immunity: This is the type 'that a person lias from

birth and it is related to race, species and to individual inhiritancc

from, parents, o.g., tian is immune to some diseases tliat affect animals.

2. Acquired immunity: This can be developed by the individual

either through getting the diseases or through immunization against the

disease. It may be Required actively where the body is stimulated to

produce its own antibodies, or passively where the body is tonpcrai-ily

protected against disease by the adHn.isstration of already prepared'

un+.i bodicis Many

ol.p'll dio vicocl—

md childxon 3 ivirir in Ux.

lossly from a number of coct.-iunicablo disease..- such ns tuberculosis,

diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus, which can be prevented by

innunization.

This situation persists because of the following Facts:

1. Parents end other adults often de not know that children

can be protected from many co; nunicablc diseases, by giving then the

necessary immunization.

2. The services for irirunization nay not be available in the

villages at a title and place that is convenient to the people.

fl

3« Individuals nay have religious or ether beliefs that inter

'f''. their accepting innunization.

4* Pregnant women do net get tetanus boxoid immunization and as

a result the newborn child is exposed to the iri.sk of tetanus.

Tlic immunizations -most commonly rood in India arc those

against the following diseases:

i.

Smallpox

ii.

Tuberculosis (BOG)

iii.

iv.

Diphtheria

Pertussis (whooping cough)

{

|

v.

Tetanus

J

vi.

Poliomyelitis

v,«’.

(DFT)

i

vii’. Cholera.

Typhoid (TAB)

Smallpox, BCG and JpT vaccines are administered routinely to .

infants and young children. Tetanus toxoid is administered to pregnant

women as part of prenatal health care. However, protection against

poliomyelitis, c clora and typhoid is usually limited to commnitics tint

have a high or frequent occurrence of these diseases, or where there

arc outbreaks of such. diseases.

• •Contd/2-

’

,

$

:2:

The protection that is possible through immunization docs

not last for a lifetime. The lenght of protection from various

diseases depends on the particular immunization, o.g., for cholera

it is six nonths and for snailpax three years. This is the reason

why the sane immunizations have to bo repeated regularly for the sane

individual over a period of tine. The immunizations that are adminis

tered after the initial dose or doses at regular tine intervals in

order to maintain a high level of protection are called booster doses.

12.2

RESPONSIBILITIES OF HEALTH WORKER (MALE)

RELATED TO IMMUNIZATION

In the intensive area

1. To administer DPT vaccine, BCG vaccine, and wherever

available, oral polinyclitis vaccine to children one to five years.

ii. To give primary vaccination agniist. smallpox to children

above one year and to adults.

iii. To revaccination all children and adults against smallpox

every three years -or earlier in the event of an Outbreak cf smallpox.

iv. To assist the Health Assistant (Malo) in conducting immuni

zation of school children against smallpox, diphtheria, tetanus, tuber

culosis,” and other diseases.

v. Tc give cholera, TAB or pclimyolitis vaccine in the ease

of.'”n wttowl

typhoid or poliomyelitis.

vi.

To educate the

-f-.lnr.. ^oeossniv for "jmnnrn *^^ti nn

vii. To plan your activities.related. tc immunization with the

Healtli Worker (Female).

viii.

To maintain the required records a.r'1 subrit reports.

In the twilight area ’

In addition to the eight activities listed above, your additional

tasks in the twilight area are as fellows:

ix. To administer DPT vaccine, BCG vaccine, and wherever

aval 1 nbl a, oral polimyolitis vaccine? tc chil Iren aged zero

year.

x. To give primary vaccination against small rex to all children

aged zero to one year.

7

xi.

12.3

To administer tetanus toxoid to pregnant women.

pWIHZATION SCHEDULES

In order to rake sure that the susccptibel groups within the

community arc well protected against preventable communicable

diseases, immunization schedules have boon developed. You will note

that sene i munizntions arete be given to newborn infants as well as

to infants during the first year of life and subsequently'booster

doses arc to be given or revaccination rust bo carried cut.

Schedule cf iarmizations for children.

Age

At birth or as seen ns

possible after birth

Irnunizntion

Smallpox vaccination BCG

Vaccination.

. .Contd/3-

: 3 :

4 to 9 months

DPT (Triple Vaccine):

2 doses at intervals of 8 to

12-weeks ■

Poliomyelitis (trivalent oral

vaccine):

3 doses at ir.turyals of 4 to 6

weeks

........

" .",

1 year

Smallpox rc/accination

5-6 years (school entry). Smallpox revaccination

or soon thereafter

. DT booster, 1 dose

TAB vaccine 2 doses at inter

vals of one month (Repeat every

year)

Every 3 to. 5 years

Smallpox rc'-r.ccinaticp '

During outbreaks, c..g.,

cholera, typhoid or

poliomyelitis

■ Cholera vaccine : 2 ,d< sos atl1Odr.y i ntcrvals

T/JB: 2 doses at 10-day intervals

Poliomyelitis (Trivalent oral

vaccine) : as above

Following injury

Tetanus toxoid booster

Schedule for tetanus i. nunization of pregnant women

Duration of pregnancy

Tota.nus toxoid

20-26 weeks

30-36 weeks

1st d JSc*

2nd dose

*Therc should be on interval, of 8-12 weeks between the first

and second dese-. The second dose should be given at least.

2 to 4 weeks before the expected. date of delivery.

CONTRAItOICATIONS TO IM-iUmZATIOI-I

12.4

;

a

■^0^*

Immunizations should not be administer d to individuals who

arc sick, because illness interferes with the production of a ntibodics

by the body. However, during cpidcidcs, this general rule may be

relaxed in order to protect as ’.’any as possible who arc exposed to

the disease.

. ■ ?,

.

Generally, the following symptoms in 'a.i individual ord considered

as contro-indicdtions for ad. ini st-., ring inainioatic-ns:

i.

ii.

iii.

Fevcris'l'’ncss, cough, running nose, lethargy.

Skin conditions, ■especially rashes.

Vomiting and diarrhoea if an oral v: ccino is to bo administered ■

DEI-FMBER THAT IMMUNIZATIONS SHOULD KQTdiAlY BE ADI1NISTERED

ONLY TO WELL INDIVIDUALS APB SHOULD BL BISTFOMED IF THEY ARE

ILL .

Malnutrition is not a contraindication for administering

immunizations to children. Such children fear:. a low level of resist

ance to infections and need the protection ti. t can-bo -given’be imCuizations. Their parents will have to be infer ud that additional pro

tein fods will have to be given 'for several d-.ys following, i munizati-on

....Contd/4-

to help tho body develop irunity. Such children will also need to

be given additional carbohydrates so that the bdy can utilize the

proteins properly.

12.5.

METHODS OF ADimJISTERilNG IMMUFIZATICN

To naxirizc thoir effectiveness, iv; vnizaticns are advinisterod by various routes. The routes that you will be using for giving

innunizations arc as follows:

By rzouth,. c.g., pclionyclitis vaccine.

On tho skin using multiple puncture, c.g., srallpcx

vaccination

iii. Into the upper layer, of tho skin (intruder:-al), c.g.,

BCG vaccination.

iv. Into the nctscle- (intro: uscular) c.g., DPT vaccination.

i.

ii.

. -■ --BEFORE GIVING A Y VACCINE, YOY MUST MAKE SUFE THAT YOU KNOW

' THE’ PROJER ROUTE FOR WMU'JISTERDJG IT.

CARE /ID STORAGE OF VACCINES

12.6

-The vaccines which you will use for iirunization certain

the following:

'

1.

Live organists that have been we.-honed or diluted so that

they arc no longer capable" Of preducing.the disease, but

are still capable of producing i: r.unity.

2.

Dead organises which can rise st:.Eulato tho production

of protective antilodies.

3.

Toxoids w ich arc toxins produced by or'-.-misns, tut which

have been treated so as tc cstry their toxicity without

destroying their ability tc stirlate the body tc produce

its own i:n unity.

ALL LIVE VACGEHES 1-iUST BE:

'

i.

STORED AT A TE'-WATURE WITHIN THE RANGE WESCETPER^gb

THE WJJUFACTURER.

n . JROTECTED FROM SUNLIGHT.

' iii. PREVENTED FROM CONTACT WE TH ANTISEPTIC SOLUTEOiJS SUCH

AS SHRIT OR SAVLON *

Form

Type-

Stere/refrigerate

. D7T, DT and

Tetanus toxoid

Lqpid

Toxoid

2° to 10°C

BCG

Freeze-dried

live

organist :s

2U tc 10uC

Smallpox _

Frcczo-dried

IdAO

orr^nis^s

to 10v'C

Cholera

liquid

Dor.d

cr^nis'is

to 6 %

Liquid

Do-d

or^'inis’.is

2° to 8 UC

liquid

Li.vo

cr‘7?.rAs:.:s

■ i-inus 20uC

(keep- frozen)

Vaccine

Typhoid and

paratyphoid

’ A" and B

M-ioryoli ti s

Contd/5-

: 5 : '

Since there is a lock of refrigeration facilities at the sub

centres, you will have to remember to order only what is needed each

week from the IriLr.ry Health Centre. Use care in transporting it

from tlio Primary Health Centro to the subccntro and improvise wa.ys

of keeping the vaccines as cool as possible. Vaccines should be

carried in a thermos flask packed with ioc or cold water. They

should be stored in tile coolest place in the subcentre, preferably

in an earthenware container which is covered with a wet cloth.

ALL VACCINES MUST BE STOPED LT TEMPERATURES RECOr MELDED BY THE

MANUFACTURER OTHERWISE THEY WILL DETERIORATE /J© EECOLE USELESS.

DISCARD ALL UNUSED LIVE VACCINE AT THE EID OF THE WORKIIIG DAY

BECAUSE ITS POTENCY DETERIORATES RAPIDLY WHEN NOT REFRIGERATED .

12.7

PREPARATION OF VACCINES. FOR ADlgLI STRATTON

The vaccines that you will be using to administer i:: unizations

to children and pregnant women arc avilablc either in liquid or in

powder fora.

It is important that both for.is are kept sterile during

preparation, recosntitution and administration. If tis is not done,

the results ray not be valid and there ray be infection.

The vaccines in liquid fora generally co: :c in ! ultiple-dose

vials with a sealed rubber cap at the top, in sealed ampoules, or in

small bottles with screwtops which hove attached calibrated or non

calibrated medicine droppers. The?-vac ci nos which come in powder fora

are pack*?'-1 in sealed glass a’, .poulcs. The diluents or liquid which

must be used for : ixing the into sc 1 tion arc usually packed in

either multiple-dose vials or in sealed glass ampoules.

...

....

i

Points to remember

Clean the rubl er cap ef tin vial with spirit before inserting

the needle.

2. Inject air into multiple-dose viols before withdrawing a dose

or doses in order to equalize pressure, and facilitate withdrawal of the solution.

3. Protect fingers when filing and opening glass ampoules so

that cuts are avoided.

Avoid •.aking bubbles when rocostituting vaccines because

this can interfere with accurate measure: ent.

1.

•

12.8

SITES USED FCT. ADMLIC STORING VACCINES

'

Because of the danger of injury to nerves and the need to avoid

injecting vaccines into largo blood vessels, certain sites bn the

body arc selected for administering injections. The core only used sites

are a s fellows:

1.

For intramuscular injections (DPT, DT, Tetanus Toxoid, TAB

Cholera):

i. The upper ara two to three finger widths below the point

of the shoulder on the outer asnoct (sec fig. 12.1).

Be careful to avoid the radial nerve which runs along

the inner aspect of the ar?..

•

Contd/6-

Fig. 12.1 Site for intr-.'mscular injection - ----upper arm.

ii. The buttocks can be divided with imaginary lines into

four parts and the injection given in the upper part

as shown in figure 12.2. Be careful to avoid the

sciatic nerve in the hip. Usually tills site is not

used for infants who ar. not yet walking since it is

not sufficiently well developed.

fig. 12.2: Site f'.r intramuscular inject!; n buttock

iii. The front of the thigh (see fig.12.3). This site doos ’

net lir.vc large nerves and is easily accessible. It is

commonly used in children

Discomfort of the injection

can be ; ini', ized b; slight flexion of the thigh and k

knee before injection

fig.12.3:Sitc for intra:xtscular injection

- front of thi.'fli

: 7 :

Fig .12.4:Site for intramuscular injection —

cut silo of thigh

Hie site used is dependent on whether CG and smallpox

vaccinations are administered at the sane tiro.

i.

If BCG and smallpox vaccinations arc given at the sane tine,

use the right upper am outer portion for BCG and the loft

upper am outer portion for smallpox. The use of different'

sites is necessary to reduce the possibility of complications.

ii.

If BCG is given after the smallpox scab has fallen off, use

the left upper am outer portion.

3.

Multiple-puncture method (smallpox v; ccination);

2.

For primary vaccination, tho loft upper am, outer aspect1

is used (sc.c fig. 12.6).

.......... .Contd/8-

Fig. 12.7 :Sito for S’.'alj.rox revaccination

- front of rr cam

12.9

POINTS TO BE KE IT IN iJIH JJ.CUT A;/flail iili-iG liMJNIZATIONS

Seiction of site should bo dene, by;

i. Inspecting the size of the : n.-jclc •

ii. Ascertaining th.-* the site i" free of bruises or any

sore areas.

iii. Avoiding an area t’>at ‘-'as any scratches, cuts or skin

disease.

iv. reviewing that t.nc area selected, is anatoiically correct.

1.

............... Contd/9-

q

2.

It is necessary to restrain cldldron while

administering irrunizatic ns • This can be'done

be a parent or othcradult so that accidents such

as the noodle breaking during injection can bo

avoided.

Health teaching is in- ortant for .ainiipg the confi

donee of parents- Unless they know about the kinds

of discomforts that can bo expected after im.unization and what action is tc "o taken, parents ray not all

allow i’.nuniz.ytion of their children.

Information

regarding the care of the site is especially important

after an -ind-iy-idnal has been vaccinated against

smallpox.

4- The vaccine rust bo prc'-'crly stored and an;, vaccine

that lias boon improperly kept er left over must,be

discarded.

5. Proper technique is necessary for ensuring go cd

results.

3.

12.10

SHALLFCK VACCINATION ■

.

Your responsibilitis with regard’ to st allpox vaccination

are of two kinds:

To give primary vaccination and revaccination to all

unprotected persons in the community.

2. To vaccinate all persons in the event of an cutbreak

of smallpox irrespective of then they were It. st vaccina

ted. ,

.

1.

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR ADWKE STERIHG SI'f^LIOX VACCINE

12.10.1

In the absence of an epidemic or exposure to a case of,

grind 1 pox, the following individuals should not bo given, smallpox

vaccination-:

i.

ii.

If the person has a skin rash with discharge.

If the child is ralnaurrshod, c.g., if it has

kwashiorkor.

iii. If tlie child is just recovering from a serious disease.

iv. If the worxHi is pregnant.

12.1

STORING AND TRANSPORTING TH'- VACCINE

Ci2

Freeze-dried smallpox vaccine is used in India, and ■

this-vaccina must be stored between /fc and 10°C.

2. The vaccine should bo kept as codas possible by

keeping the ampoules in an earthenware pot covered

with a damp cloth.

3 • If tho vaccine lias boon out of the refrigerator for

for over four wpeks, it should be discarded.

1.

■

REMEMBER, OPDEI ONLY ENOUGH VACCINE FEQUU ED FOR A MAXIMUM OF

TWO WEEKS. AT A TH® TO AVOID WASTING IT BECAUSE OF LACK OF PRO

PER FEFREGEEATION FACILITIES

Use a thermos or other container tc carry the vaccine.

The container should bo packed with ice if possible

or insulated by wrapping it in wet cloths.

................. .Contd/10-

: 11 :

Steps to bo followed:

■ >• -.

Clean the site with cotton weclthat has been r.'.cistenod

with, water and allow it to dry. Do not scrub the skin

vigorously. Do not use .spirit er other antiseptic.

2. Insert a sterile, cold, bifurcated needle into the ampoule

of reconstituted vaccine. -.When it is withdrawn, a droplet

of vaccine, sufficient for vaccination is contained within

the fork of t he needle.

■ 3. a. Hold tile needle at ah angle 90 to the skin as in the

figure with your wrist resting against the am (see fig.

12.6).

■

b. Touch the points -<f the needle lightly to. the.skin so

that the droplot if vaccine is deposited’on the skin.

c. Males 15 up and down strikes cf the needle in an area

about 5 tn. across through the droplet of vaccine. The

strokes, should be hard enough sc that a. trace of blood

appears at the vaccination site.

4. Allow the vaccine to dry before the individual rolls down

his sleeve or goes away.

5. No dressing should be applied after the vaccination.

6. Focord the administration of vaccine in the individual

health card and in the infant an I child immunization

register.

1.

A VISIT SHOULD BE MADE TO THE HOME OF TIE CHILD BETiEEN THE

SIXTH AND NINTH DAY TO CHECK WIETHE! THE. VACCIIL-TION HAS BEEN

SUCCESSFUL .

STERLIZATIOrl OF BIFURCATED PEEPLES

12.10.5

it is

The needles can bo sterilized by fin’ ing er bciling. Howovrr

referable to boil father than flame needles to sterilize thorn..

1.

-----

Flaring: The needle is passed through the flare of a spirit

lamp. It should net remain in the flare’ fef more tian 3

seconds.

COOL THE NEEDLE BY EXPOSING TO THE AIR K.FORE INSETTING INTO

THE VACO NE AMPOULE. A HOT NEDLE FULL KILL THE’CRGANLSMS IN

THE VACCINE MAKING IT USELESS.

.

.

2.

Boiling: The needles can bo sterilized by bciling for

20 r.hnuts. They can be toil el in ’the plastic container

that holds, the bifurcated. no fibs (see fig. 12.8). Remove

the container from the water nrr’ stand it on its end to

drain out the water after first shaking it hard to remove

as much water as possible. Put the container in the stand

ing position to dry.

Ccntd/12-

Fig . 12.8:-Sterilizing b? furcated needles

THE FORK OF TH’ NEEDLE MUST NOT CONTAIN A DROP OF WATER WEAN IT

IS INSEITID INTO THE VACCINE AMFOUL. WATil WILL WEAKEN THE

STBENGHT OF THE Vl’CCINE ........

NEVER USE A NEEDLE MORE THAN ONCE WITHOUT STABILIZING IT BACAUSE

of the’ danger of shielding infection.

'

.. •.

12.10.6

REACTION TO VACCINATION

A prir.ia.ry vaccination is one that is.g;von to 'an individual

for the first tine. Any subsequent vaccinations arc called rcvaccintions

■When there has been a successful or posit j- f. reaction to a prirary va •

vaccination, it is called. a ’take1 . ■

Tire usual course of a successful take is os follows:

A blister forms at the vaccination site between three

to five days after vaccination. ■

ii. The clear fluid in the blister turns into pus and by the

Bthe and 9th day the blister becomes larger.

iii. By the 11th or 12th day it dri..s air’ forms a scab.

iv. Tire dry scab falls off about 14 to 21 days after the

vaeeinatior., leaving a -pear at the site.

i.

IF THERE IS NO JUS FORMATION .T THE SITE OF A HI. ARY VACCINATION

THE PROCEDURE AS BEEN DONE INCORj FCTLY OD ".’HF, VACCINE WAS NOT

lUTENT AND VACCINATION MUST BE FE HEATED .

12.10.7

HEALTH EDUCATION

It is inportant to emphasize certain facts about vaccina

tion.

z1. It is. harmless and practically painless.

2. It is important for every individual to be protected against

si allpox.

...........................Ccntd/13-

;13 :

3« After vaccination nothing sh-culd be applied on the

vaccination because water, bandages, tight sleeves,

ointnents, herbs or unclean tilings can interfere with

the action of the vaccine•'

4. If there is no reaction at the site between the 3rd

aril 5th days, 'he individual should return to the subcctre

to have the. vaccination repoatod;

'

12.11

BCG VACCINATION

In order to protect an individual fror. tuberculosis, BCG vaccine

trust, be administered before he is exposed tc the disease. It is for

this reason that a high priority is given to administering BCG to infants

as soon after birth as possible. Since children aid. young persons in

the community are also exposed to the disease and need protection, BCG

•is also g.ven to t hen up to the ago of 20 years.

ALL INFANTS AND CHILD; EN SHOTLD BE GIVEN I"G VACCINATION AS

EARLY AS POSSIBLE TO PROTECT THEM AGAINST TUBERCULOSIS.

12.11.1.

PERSONS ELIGIBLE TO ILIAAE gCG VACCINATION

Bic eligible groups in the co.npunity for BCG vaccination

include the following:

.

r

i.

ii.

iii.

All newborn infants.

All children between zero and’ five years of a go.

All persons between 5 and 20 years.of ago.

However, you will to responsible for adtri.nist0r3.ng BCG vaccine

. to the following groups I .

i.

All children between one and five years in the intensive

area. The. Health Worker (For ale) will ndrinistur BCG

Vaccination to infants aged zero to one year in the

intensive Area.

.

■

ii. All children from zero to f ve years in the twilight area.

iii. All school children. You will assist the Health Assist

ant (Male'’ in carrying out this programs.

12.11.2

CONTR/xINDICA^IGNS TC THE USE OF BCG VACCINE

Individuals with tie following characteristics should not

be given BCG vaccinations

1. A person who already has two or more BCG scars.

■ 2. A person who is a known case of tuberculosis (although

it, would not cause hart?. if the vaccinationis ' iven by

mistake).

BCG Vaccine should be postponed if:

1.

ii.

iii.

12.11.3

.

A person has a generalized skin disease.

h person has a high fever or is acutely ill.

A person i§ severely -.'alncuri.shcd unless additional

protein and energy-.giving foods can be started, right

away<

STORING AND TEA IJS PORTING THE VACCINE

BCG

1..

vaccine available in Indan is a freeze—drl cd

vaccine. which must bo stored. nt 2 to 10°C, but not

frozen.

Ccntd/l^-

2.

It can be kept in a refrigorc.tor for up to six months

or in an ice chest up to three months. ’ At room temp

erature it can be kept for two to four weeks. This

means that vaccine for usd at the subcentre rust be

obtained at least twice a month since refrigeration

is net available.

3.

An alternative to keeping the vaccine under re frigera

tion is the use of an cartheir-'are container which is

kept covered with a wet cloth and which is kept in the

ccolcst part of the building. The vaccine can thus

be stored for about feur weeks.

4« Carry the vaccine in a thermos packed with ice when

transporting ..it for any distance, e.g., from the IHC

to the subcontrc.

5.

Light rapidly destroys BCG vaccine either freeze-dried

or in the reconstituted form. The vaccine should be

protected against light throughout, during storage

as _woH_as during transport and use in the field.

ALWAYS REMEMBER Td PROTECT BCG VACCINE FROM HEAT AID LIGHT

TO ENSURE 'ITS FOijENCY. ..... ..

’

’

' :’

RECONSTITUTING BCG VACCINE

12.11.4

Equipment required:

i. Sterile 5 ml syringe

ii'. Sterilq 22 gauge neefj.es

iii. BCG Vaccine ampoules

iv. BCG diluent ampoules

v. Ampoule files

vi. Plastic sheet.

Proceed a» fellows:

1.

!

'

••

.

Examine thj ampoules .-nd discard them, if:'

.

i. There are colour changes;

11 . The powter appears to be wot;

There

iii,

a?e cracks or the ampoule is broken;

There

iv.

is no label on the ampoule;

The

v.

datq ofeepiry is over.

Follow stepfc 2 to 8 under the procedure for reconstituting

smallpox Vtccinc (see section 12.10.3) except substitute

the use of the plastic sheet instead of cotton swab.

9•

Follow -the uc.nufacturor’ s instructions regarding the

amount of ciluent to be added to the dry powder.

10.

Fix the 22 gauge needle into the 5 ml. syringe, withdraw

the requires a.r.'.cunt of diluent fpom the ampoule and gentry

—inject it into the ampoule containing the dry powder.

2-8.

THE USE OF TOO MUCH FGCE III INJECTING THE DILUENT WILL CAUSE B

BUBBLES TO FORM IN THE- SOLUTION. AVOID THIS BECAUSE IT WILL

INTERFERE WITH ACCURATE lE/SbTEMENT OF Till'CAVVI1E .

11. Withdraw and rc-injcct the vaccine into the ampoule at least 4

- tines to cake- -sure that it is thcrougld.y mixed.IF ANY OF TE DILUENT "IS LOST DURING IFCORSTITUTICD TIE STRENGTH OF

THE SOLUTION WILL NOT -3E ACCURATE SC YOU l.UST'OIEN ANOTHER AMPOULE

' OF POWER ’AND' DILUENT JND BEGIN THE ILCGEDUT E OVEI AGAIN.

Contd/lj-

.

: 15 :

12.

Keep the anpoulc of reconstituted vaccine in the anpculc holder

. ’ in a cool place protected free. light by wrapping black paper in

the shape a cone around it.

REMEMBER THAT BCG IS A LIVE VACCINE W1ICII C/JT EASILY LOSE ITS

POTENCY IF IT IS NOT iiANDLED 'IROEER1Y

12.11.5

TECHNIQUE FOR■ INTRALErdlAL ADl-iINI3Tr.ATI0N CF BCG VACCINE

An intradcrnal injection is given in the uppermost cr'superfi-cial layer of the skin. In order to be able to inject a vaccine or drug

intradermally, a special sized needle and a special syringe with fine

parkings (tuberculin syringe) arc needed (see fig. 12.9) and. the needle

trust be introduced at a part? ufLar angle to the skin.

o

Fig. 12.9. Tuberculin syringe and needle

Equipment and supplies required:

i. Sterile rtital box containing noodles and syringes .

ii. 'Sterile roadies 26 gauge, I cn

iii. Sterile tuberculin syrings (calibrated in 1/100 nl)

iv. Weeden I lock for holding opened ampcules

v. Spirit leap and bottle of spirit

vi. Metal shield for spirit lamp

vii. Blackpapcp for covering BCG vaccine

viii. Mantoux ruler for -ensuring intradermal weal.

■

‘

f

' ,

.

!

i

Proceed as fellows:

”

■

1. Assemble the tuberculin syringe us^ng the proper techni

que to avoid cental in ti on r-< attach the 26 gauge needle

to it.

2. Make sure that -the ’eye’ or opening of the needle and the

nr.rld.ngs qn th.: syringu are on the same plane. This isinpor+ant so tint the correct docs can be injected (see,

fig. 12.10).

;

•Contd/t°/-

: & :

Fig. 12 .'0: Intradcrcal noodle shewing tine I’oyo"

>

3.

1

Draw up tho Vaccine into the-syringe'talcing care net to

touch the needle with the fingers or other unstcrilc

objects.

'■ .

4. Ilacc the loaded, syrin o on a sterile surface. ■

5 • Select the ££to for vaccination. BCG vaccine is usually

given on the Loft, upper arc just -below the point of the

shoulder. (Daf-jr to section 12.8).

6. Cleaning the itc is not noco-sary unless it is grossly

dirty in whijii aaso wipe it with a clean, wet cloth.

7. Make tho slcii of the site taut by stretching it slightly

between the tiuub and -forefinger.

8. Keep-! the ’eye' of the needle up, hold the syringe parallel

er flat along tho skin and insert tho needle into tho

upper or superficial layer of the skin (see fig. 12.11).

LEfEEER, DElf liJECHCN GF BCG VACCINE CAbSE ABSCESSES AID

TAKE A LONG TIME TO HEA1.

Cbnd/1!?-

9« Irjcct the required dose which is:

i. 0.05 ul. for infants, under..four-weoks of ago.

ii. 0.10 rfL.' for all other children.

A weal or elevation of the skin should fom at the site

of vaccination. A proper intradcrdal injection of 0.10

ul. of vaccine will fora a weal of about 8 up.. in diauctor. This should be check using the Mantoux ruler for

every tenth person vaccinated.

10. Renovo the needle after administering the vaccine and do

not rub the site of vaccination. .

11. Replace tho used needle by a sterile needle or fierce it

between use.

• •

12. Administer the vaccine to time next individual using the

sane procedu:»■.

13. Record tho administration of vaccine in tho individual

'health card and in the infant and child immunization

register.

-........................

■

^gjBgG.

12.11

.6

IS NOT US!© WITHIN 4 HOURS OF RECONSTITUTION

WHAT TO EX7ECT AFTER BCG VACCINATION

Explain to parents the changes which they should expect

to see at the site where the vaccination has be n given and alert

then to those synptens which requires referral to the lYirnry Health

Centre for further at ten tic n.

Time, precess cf scare formation is as follows:

■4. The BCG veal or raised spot in the skin is. usually

absorbed and is net visible after 30 minutes.

2. After three tc four weeks, there is redness ana ,-^rc.i1ing

and a lunp appears at the . ita, of vaccination. This

is about 3 to 8

in dinretor.

3. By six t? eight woo! s, the area, increases in size to

6 tc 8 ra. in dirmmter. Crusting or pus my be present..

Deep abscess formation always indicates that the injection

was given incorrectly either.into the subcutaneous tissue

■ or into tho uusclj. ~cpending- on tho severity of the

abscess, refer t<. the RHC.

. By 12 weeks, there shoul-’ be a well-lealed scar at the

site of vaccination.

12.11.7

HEALTH EDUCTION

Points to emphasize should.include the following:

1. Rabies aid children need to t-_ im.-unized ns early as

possible with BCG so that they can be protected against

tuberculosis.

• .

■

2. BCG vaccination is a simlc, safe procedure which consi

sts in injecting vaccine into tho skin.

3« Within three m.onths after the vaccination, there will be

a scar showing that the individual is protected against

tuberculosis.

4- BCG vaccination can be taken at the subcentra or at

other convenient places in tho villa/.-, where groups

can bo ga'atcrcd together.

5. A. second vaccination will be required to be given to

the child during the school years.

..........Contd/l8-

: 18 :

DPT, DT, DiniTffiSK AND TETANUS TOXOID

12.12

Tlie vaccine used for itxiunizing -persons against diphtheria,

pertussis and tetanus is available either in a. combined fom, i.c. as

DPT er DT, or as a single vaccine which protects against diphteria or

tetanus. Every op-ortunity should be taken to- protect children under

five years of age against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus, and pre

gnant women against tetanus.

PERSONS ELIGIBLE TO RECEIVE DPT, DT, DIPHTHERIA CP.

TETANUS TOXOID

12.12.1

Groups eligible for DPT arc-as .folios:

i. Infants from four to 12 noths of age.

ii. Children fro;.: one to five years cf age.

Groups eligible for DT are as follows:

i. Children from five to ten years of age (they nc longer need

pertussis vaccine).

Groups clcigible for tetanus toxoid arc as follows;

i. Pregnant woven.

ii. Others in the corr.unity who have not received PIT or DT as

children.

iii. Those who sustain an injury.

In the event of an epidevic cf diphtheria in tho oornunity, all

groups should bo_ immunized with diphtheria toxoid.

12.12.2*

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOPt ADIill'HSTERING DPT.DT A1--D TETANUS TOXOID

Those persons with the following character i.sitcs should not

be given DPT, Dt or tetanus toxoid:

Anyone who is ill or is just recovering from an illness.

History of convulsions.

History of allergies, i.e. inflaraa.tory skin conditions

with blisters, crusts or discharge, or weals with or with

out etching, or wheezing rcspirttion.

4* History of previous unexpected reactions to medicine or

1.

2.

3.

vaccine.

Innunizatitn of anyone who is ill shen Id be postponed and those

vhp have other contraindications should ba examined and screened by tho

doctor.

.

12.12.3

STORING AND TTJ^SIURTING THE VACCINE

.(Soq faction 12.6)

12.12.4

DOSAGE OF VAOffiE

Tho dose of tn vaccine Can vary according to -the manufacturer

and the type of vaccine t< be administered. For full protection child

ren under five years cf age should receive two doses of DPT at intervals

of eight to 12 weeks followed by a booster dose of DFT at one and a half

yar to two years of ago ;.nd a second’booster dose cf DT on entry to

School or soon after.

Pregnant women need to have tzo doses cf tetanus toxoid with

on interval of eight to ’2 weeks between oac' -lose. ■ The second dose

should bo administered tvo to four weeks before tho expected date of

delivery in order io protect the infant at birth against tetanus.

12»12.5

rROCEDUP.S FOR ADnCKISTRATION OF DPT, DT AJO TETANUS,TOXOID

Equipment required:

i. Sterile 2 uL. or 5 ml. syringe

.

'

.......... .....Cbntd/l9-

’ ■

. i.

i

: 19 :

ii.

iii.

iv.

v.

Sterile noodles 1.5 cn (for children) 23 gauge

3.5 cn (for .adults) 23 gEUgo

3.5 cn (for withdrawing vaccine

fren vials) 20 or 21 gauge

Vaccine (DPT, DT or tetanus toxoid) ..

Cotton swabs.

Antiseptic such as spirit or savlon.

Proceed as follows:•

.

Assor.blo the syringe.

Withdraw the required auount of vaccine into the

syringe.

iii. Clean the skin site selected.

iv. Inject the proscribed dose.

v. Record the date and arcunt of vaccine given on the

individual’s health card ant in the register.

vi. Tell tile nether what tc expect and advis^. fcr what to do.

(Pefer also to Chapter 28, 1 Sterilization and Disinfection’

and to section 30.8.4).

i.

ii.

-12.12.6

POINTS TO REISFiBER ABOUT ADrU-ilSTERIIIG PIT, DT HID TETANUS >.

TOXOID

1. Read the label of the vial to ■. akc sure that you have the

correct vaccine far the innunization to be given.

2. Measure each dose carefully when giving no re than one dose

fTon a single syringe.

3. '.Nover use a needle acre than once without first flaring

it or boiling it for 20 tiinutes.

4- The dose is the s-nc whether it is the first or second

injection or the booster dose. The de so tint is usually

prescribed is as follows:

DPT

- 0.5 r?l. for infants and chaldron up to

five years.

*

DT

- 0.5 r.l

for children over five pars.

Tetanus loxr id - 0.5 r.il. for pregnant wenen.

However, rale sure of the dose indicated by the nanufacturer

on the vial before adr.nnistoring the vaccine because this nay vary.

12-12.7

PJEACTIONS 10 DPT, DT AND TETANUS TOXOID

Expo ctod syupters

SLiglt fever, sore am and irritability fcr a day or two.

Trcatr’ent: '

i. Apply hot wet copross.

ii.. Give AJO (1/4 tablet under 1 year

1/2 tablet one to five years).

Unexpected synptons

1

i. Disco’curation or bruising of injoctioii site.

Troatront!

Apply hot -4et copress.

ii. High fever, abscess formation, convulsions.

Refer anyone with those con-licaticns to the Fritary

Health Centre.

12.12.8

HEALTH TELlyH NG ABOUT PIT, DT Ai'~ TETANUS TOXOID

Points for discussi n should include the following:

1. Infants and young children arc -vulnerable to diphtheria,

whooping cough and tetanus r.ni rany die each year from

the effects of such infccti'.ns. They need protection

fro:.’, all three diseases thr ugh. irrunization.

........................... Contd/23-

: 31 :

2,

At least 2 '■loses of DPT '-'.ven net mere than three

r.o: ths apart are needed t<< bi’-ild up protection,in

infants and young children. later, booster doses

arc needed. One infection in not enough to pr<+-oct

infants and ycv.n'’ children against diphtheria, whooping

cough and tetanus.

3« All pro'uant wo~.en need tc. got tetanus toxoid rhrri ng

pre;-nancy in order to protect the ba1 v at birth.

4« Children no. d a booster dose when they arc ready

to enter set. cl since there will bo orc exposure

to infection and they should' be protected'.

5- Immunizations are available bitter at tlx* subcentre

or in the hor.o«

'

6. After ii runia.- tion tte.ro cay be slight fever, sore

ness of the site and irritability for a day er two.

These synpters are expect.i reactions and should riot

be a cause for worry or ilr nc 11 ding the second

IT IS lETOI-TAr?TO EXILAIN THAT TWO C01-STC1 Tlv;; INJECTIONS ARE

NEEDED FOE' DEVELOTlIIG FULL liGTECTION AC.’INST THESE DISEASE ' * '

12.12.9

TETANUS TOXOID IN 1DEG1.ANCT

One cf your inportant tasks in the. villa.-cs of the twilight' '

area is to imnunizo as nany pregnant women as possible against tetanus.

Uiis is necessary because their newborn ha’.ies often contract the

disease as a result of being dcliv re 1 by untrained dais who do net care

properly for the umbilical cord. A large number cf babies die from

tetanus infection each year in India. Such deaths can be prevented

by immunizing pregnant women with tetanus toxcid luring the prenatla

period.

■

In order to bo able to do this, you will have.to develop

goed working relationships with village dais since they a re the only

ones who take care of pregnant women in t’ j twilight area. _ Sone of

the ways in which you can do this arc as .follows:

Sr.ok then out whenever y u rake a regular visit to the

village to show that you recognize their work.

ii. I’ blidy recognize their assistance in prenoting the use

of family planning and other health services by the people

in the village.

iii. Tutoress upon then the health benefits cf tetanus toxoid

f r the pregnant wcr.cn under their care.

iv. Inform the dai after you have given tie tetanus toxoid

to lie pregnant woman.

i.

The Health Worker (Ferric) nay else be able to offer

further suggestions fry approach! g dte's when she ; ay already know thro

through her work in assisting the R alt’-i Assistant (Fonelo) in the

training of dais. These a^it-ional sources of assistance should be

regularly used. since they nay often load to more effective ways of

working withwomen in the village.

One of the problems that you ray fin1 is that pre. pant

women ray n-1 allow you tc i/.mmizc then i.i their hones because cf

social custons. In order to get around this y. u ray have tc take

the following steps:

i.

Ask r number cf women to go.c.bcr in a convenient

place sc that the vaccine C"n bo administered to a

group -of women.

.................. .Ccntd/2l/-

: a, :

. ii. Hol?1, a combined clinic fcr adud nistering tetanus

toxoid to rrc ,-nnnt women a.il J1T fcr•pre-school

children on a rcgularly sc'icduled day in the

village.

iii. Ask the lais tc assist you in gathering together

women and children win liv. in the sane area, so

that innunizaticns can be administered io the

residents of every sector in.the village over a

period ,f months.

12.13

rOUOK ELITIS VACCINATION^ ■ ,T. SAC-IIT VACCIE1) .

In India, policmyo'' itis is adi ini’.tcred on a mass basis

only when there1 is an outbreak cf th- disease in a community, i.c. when

a high or unusual number of cases arc found in a locality.

12.13.1

ELIGIBILITY FO

VACCIH.’.TION

Wherever availaMe the vaccine is given to infante ' J'-ween

four tc six months since this is the period w on the body is able to

begin manufacturing its own antic Bodies. The vaccine can be given at

the same tine as DPT vaccine.

12.13.2

, couTFAiiDiciTicms to vaccination agaenst rcLii-gELiTis

Vaccination against ; clionyclitis should not be given

if the Allowing conditions are present:

i.. Acute infectious disease

ii. High fever

iii. Vomiting.

iv.

Dyseritory..............................-.........................

. —....

USUALLY rOLIOl.YELITlS VACCINE IS NOT AD’IlCJTEnED DUIING THE

SUM® AND MONSOCN SEASONS BECAUSE OF ?1HE HIGH INCIDENCE OF GASTFOINTESTINAL'DISEASES . ' ' "

' '

STORAGE OF VACCINE

Because .the poliomyelitis vaccin ■ that is used in India

is a live vaccine, certain precautions i.ust L>. folloi-cd in storing it

before it is administered.

12.13.3

Fig.12.12:Frocc^urc fcr adrdni.st ring'oral ■''reps to children.

: 22 :

Special facilities are made available for keeping it at minus 20° to 0°C to

ensure that the vaccine retains its potency.

Usually special containers and

ice are provided for this purpose. ,

12.13.4

ADMINISTERING ORAL POLIOMYELITIS VACCINE

Proceed as follows.

1. Note whether the vaccine comes in a container with an attached medici£lfidropper. If there is no dropper, a clean syringe will be needed for /

measuring the dose to be given.

2.

Examine the dropper provided to make sure that it is not cracked or

broken and discard it if this is so.

KEEP THE CONTAINER OF POLIOMYELITIS VACCINE JN A VESSEL CONTAINING ICE

WHILE YOU ARE ADMINISTERING IT. IF THIS IS NOT SCRUPULOUSLY FOLLOWED,

THE VACCINE WHICH YOU WILL BE DISPENSING WILL BE USELESS SINCE HEAT

DESTROYS ITS POTENCY

3.

Measure the dose to be given according to the manufacturer’s instr

uctions using either the medicine dropper or the syringe.

4.

Ask the parent or adult to hold up the head and shoulders of the

baby or child as the vaccine is dropped into his mouth slowly so that

he does not choke. If the child will not open his mouth press down

gently on his chin(see fig 12.12) or press the cheeks.

5.

If the child spits out most of the vaccine, repeat the dose

6.

After the vaccine has been given, instruct the mother or adult

with the child that no breast milk or hot(temperature) foods

should be given for four to six hours following the vaccine. Other

food and liquids can be given. This is important for ensuring

the effectivdness of the live oral vaccine.

7.

Record the dose and date on the child's health card.

8.

Give the second and third doses at intervals of four to

six weeks.

12.13.5. HEALTH EDUCATION

Points for emphasis should include the followings

1. Poliomyelitis is. a serious disease that can paralyse and cripple

arms and legs, but it can be prevented by oral poliomyelitis

vactlnc

2.

The vaccine is given in the form of oral drops

3.

In order to be protected, three doses given at four to six weeks •

intervals are needed by the child.

4.

Usually a booster dose is necessary after four to five pears.

............ Crntu/23—

ANTIBODIES IN BREAST MILK CAN ALSU INACTIVATE LIVE ORAL POLIOMYELITIS

VACCINE SO BREAST FEEDING MUST RE 'WITHHELD FOR FOUR TO SIX HOURS BEFORE

AND AFTER AN INFANT HAS BEEN GIVEN THE VACCINE.. HOWEVER,IT IS IMPORTANT

NOT TO STARVE INFANTS OR CHILDREN WHO HAVE RECEIVED THE VACCINE. THEY

CAN BE GIVEN OTHER FOOD AND LIQUIDS AS DESIRED AS LONG AS THEY IRE NOT

SERVED HOT.

12.14

CHOLERA VACCINATION

Vaccination against cholera is given to individuals on request and

mass programmes for administering the vaccine arc carried out in tho event of

.epidemics of the disease in the community.

You will need to bo alert to cases of cholera and gastro-enteritis in

each village as you make your house-to-house visits since prompt treatment may

be necessary to save life. You must immediately inform your supervisor,

whenever there is a sudden riso in the number of persons who have signs and

symptoms of cholera sc that a decision can be made whether a mass programme needs

to be organized for the community(see soction7.l)

12.14.1

STORING AND TRANSPORTING THE VACCINE

....

1. The vaccine should be stored in.a refrigerator at 2°to 9°C. When

a refrigerator is not available, keep the vaccine in an earthenware

pot covered with a wet- cloth and.in a cool place.

'

' ’’

2.

Transport the vaccine in a thermos flask from the Primary Honith

Centre to the subcentre

3.

Order only enough vaccine that can be used within seven to 14 days

since it will deteriorate whon kept at room temperature for longer

periods.

f"-.

.12.-14.2 DOSAGE OF CHOLERA VACCINE

j.

The dose for adults and children over five years is 0.5 ml. followed by

a second dose within ton days. The dose for children under five years is half

the adult dose. . In orddr to maintain protection against the disease, individuals

nded to be given re—vaccination every six months.

12.14.13 ADMINISTERING CHOLERA VACCINE

Equipment required?

Sterile needles both short and long(for withdrawing vaccine from

multiple—doso vials and administration of vaccine)

ii. Sterile 2 and 5 ml syringes

iii. Cotton swabs

-x

iv. Cholera vaccine vials

v. Antiseptic such as spirit or savlon

i.

Proceed as follows?

1. Remove the metpl disc covering the rubber cap of the vial and clean

the cap with a cotton swab moistened with antiseptic.

2.

Assemble the syringe and attach tho needle for withdrawing the

vaccine

3.

Withdraw the -required, a.miiunt of vaccina from the vial

4.

Change the needle for administering the vaccine

5.

Select the site for administering the vaccine which should be either:

the outer aspect of the upper arm about midway between the

shoulder and elbow, or

ii. the outer aspect of the thigh(see fig 12.4).

i.

............ Contd/24~

6.

Clean the skin site selected using a cotton swab moistened with

antiseptic ->nd allow to. dry.

7.

Inject the prescribed dose of the vaccine intramuscularly

8.

Record the date, name and amount of vaccinr. administered on the health

card of the individual

'

9.

Tell the person immunized or the person accjmpanying a child that after

the injection the following reactions may recur?

i. Soreness and swelling of the site

ii. Fever

iii. Headache

'

These symptoms may last for about two to tnrec days, but should not be a

cause for worry. Tell him to take APC tn reduce pain and fever and apply

warm compresses to the area. 'If the reactions arc more severe than expected tell

him to go to the Primary Health Centre. .

12.14.4. HEALTH EDUCATION

Points to be emphasized should include thi

following?

1. Cholera is a serious disease transmitted thv-ug?. contaminated water or

food and which can be fatal if teatment is not given ■ imc.-idiately.

To be protected against the disease, an individual needs to have two

doses bf vaccine ten days apart. 'Revaccination every six months is

necessary for maintaining n high leVel of protection.

A

,

TYPHOID, PARATYPHOID/AND PARATYPHOID-B Vi,CuINATION(TAB.) -■

2.

12.15

In India vaccination against typhoii! fever is carried out on a mass

scale only when the disease is highly endemic in an area. When there is an

epidemic, house-to-house vaccination is carried out.

You will need to be alert to cases of diarrhoea with abdominal .pain,

headache, skin rash and fever as you go about your work since these are the

signs and symptoms of typhoid fever. You must report any sudden increase in the

number of sych cases to your supervisor,' so that ine can decide whether a mass

programme needs to be organized. Your responsibility is to assist, the Health

Assistant(Male) to immunize the eligible population(refer to section 6.1.7),

H2.15.1 PERSONS ELIGIBLE TO RECEIVE TAB VACCINATION

{

The eligible groups in the;community for TAB vaccine in an-endemic

area are, in order of priority.

i. School-aged children■

ii. Adults up to 50 years of age

However, during an epidemic, all persons in the community should receive

the vaccine.

12.15.2

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR ADMINISTERING ROUTINE TAB VACCINE

Individuals with the following conditions should not be given TAB

vaccine except during epidemics

1. Fever with running nose or cough

2.

Lethargy associated with illness

In such cases, the administration of the vaccine can be postponed and given

to them when these signs and symptoms have subsided.

. .............. Ccr-td/ 25-

: 25 :

12.15.3. STORING AND TRANSPORTING THE VACCINE

,r

’■

1. The vaccine should be stored in the refrigerator at 2° to 8°C. If a

refrigerator .is. not available, keep the vaq'cihe ip ah earthenware

'■ pot covered, with a.-wet clpttVand. kept- in a’’-cdol’‘(Sjlace.

::: „ ,

.-1&U.-1 nno

,..'.3

: ’r. ’.1“ 2*-%“should be transported.jnrfo.ithermos 'fOas^^ftbtn^Eh'e .Primary..Health

----Centre to the subcentre.l- i'o-i ni

dui'bc .. . , . . 37(. nrtd r.oai-iir.s 3’-- ?fii 6

*S

.en'.133-^?1J0i‘de^'.8rtiy. enoughIvaBcine t'baW’oh

"u^ec1 ,Witiii^',^.§von to 14 days since

it will deteriorat-e when/kept'.at'' rboni temp ■'rraturc-iA’’:'5 .■

- n'.f;

JriT

ej^'12.15:.4 BfJff«SE.’TQR...TflB. W&INAbj?; .•SrfdAhfife’

- n Ale

.....' f J;'rl i?t ;nci-dnRj;s!d'PV,-:

hnnJ

_

f . .

...-. This can vary according to the manufactu ?er of. t|nq;,v.a;ccin§i%..(!-,'Usually

the . dose Jorp .cbildrep jus; ha^f^;^heila(dulth.tto'sicf;1J-.•VVj?.^jjL^!’-vp^‘e|ctiqn, .ap

/J■■Jindiv/iciuai.’-1 hepds tp. 'r.e(?.ei.ve 2,;1,dqS'gbi;,of thbivacci

cfj) day..int ervals.

... “ '.‘ Annual .revnccifiatibri. is necessary for1 persons li Jihg in>cn(denij.c areas.

.

■

ridi:iadi2U15.5-'ABMiNIsfE^NG3TiBj)AeQiNEpil^'

ziuda

r:tJ?lSiPUh^ y4 nrn ibiooi Hose ph^avco

-. j-‘ W’-'■ t'<'ITA&-!9a'c.c£fie ’is ava^^^q.jb^rbres'ent'din'hf’y 'rrf’,; 100? dosp ..v^als^fTherefore

inJ order to .avoid wasting -vaccine, ybu 'should gasper’ tpg'pthot;.a .sufficient

x

7 number'of-p’ersons-.when planning'.tn: admxhist'er it in,the community.-; qp

“ '■

■'

- £ ..'J l a

jT“vf’

■miP.’S

t I

.1 ■• .’

tEquipment,..r,equij?ed.S:

*r

hn-Uhi-'ii-''

■ V •

'

' ’

<t‘.'-X-<’t ''-'; . sir.'j-'fi'H'.’rlj'.f. -:).H J

/ .

. -s-t •'«.I "

'

xx;JV/

8f>

'IIJ - ’’

_,t\d^v-St3j$le .2 or- 5-ml, syringes^ in :cteriie’ container/; A .-i .'-> .<S.Li

x-p'- ; 1 '• ii/'Sterile needles? '3.5 enh length/20 ’or 21 "gaugoCfor withdrawing

/accine from vial)

.

.

-r-1.,5' cm 'lengf ti/&5 ghuh^(?o'r''’'ft'5i&nfs't.erxp;g-r

'

iii« '.ottop-'swabs,

‘

c.nt -n-.

.1

? J /'

'iy'I 'A_8 vaccine,-.v,iai-sut tJy-'cS5 J’ '”’w

3

rx. ,,-,.r- eot'la

'tr/ n’

,;v.’ 'Antiseptic such as-'Spirit'or savlb'nf..

b.O

c

Proceed as ."'ollows

•fi

Step^l) to . 9) are the same as-for.-thc administration,'of''.’cholera vaccine

(see section. 12.1,4.3)

-.-A-'r':'I'ox'rr; ; > n-.

-

;l\

-■

'

■?- h-?' •

-.12.T5i6'HEAVh 'EDUCATION :

rHhn uh h’.; i'<"“

;

.

Pqir:g, Cor discussion,■shQult! xncl'jte bhl: Toliowipg?

'I ■'

if

'

"

•> ;

If

-r^-.'

r ■

,..<.4n ,,

3:.'.iji.b,!y--d: '.h.:..n a t

‘

...

■; _ <1 ,

’<■ nJ'-C-' •

.1

—

1. 'yphqicl is a serious'disease Which is transmitted through food and

rater contaminatedwith the typholu ‘ batilliial'7 J *5-\

..,3'.J.

\

,‘^r

-or

V .

t «•

s- : .»•.r .

. 4^.,;

o

1 Jr- 2. Individuals .can. benprotected-.against'5 sfib disease’.by obtaining

f

vaccination with TAB,vaccine. for ' f cfl 'prptect'ion. -'art, individual

• " .* heeds to have -2’ doses ■ erf vaccine t op days, apart ,;.f S4b.sequent.lyj

if- he is living-.in..............

an ...endemic

area,

ha should,

get

.a-booster3 ■■•’"■1 .

.. •

.'/■ ’rn-'fa

1

»

.. dose oach year* ' j.?---’ *• ' '

.1

• 1 *•

12.16

SCHOOL IMMUNIZATION PROGRAMME

You are assigned the task of assisting the Health Assistant .Male)

to immunize the school children in ths villages. .^Som(e...,qf-these children may

need initial immunizations': becauseI thdy' jerio'nSr protected as.-infanes' or '•

toddlejs, but others may only require Be'osters.ar’revaccination, for BCG or

' smallpox. Childr.ep. who att end’ school arn^'a l'passive' popi'.JjatiQ'n and cad ;'

easil' be reached fur administering immunizations in contrast.'to pre-s ohool

children and pregnant women in the villages' w.ho ,mus,t be identified In their

homes.

.

:

■

.

1'" .. ' h ■ ,-.

ontd/26

12.16.1.

SELECTION OF GROUPS TO BE

IMMUNIZED

Usually a few classes in the school are designated as the target

population for administering immunizations. The criteria used for the

selection of classes are as follows^

1. Protection of children as early as possible i.e. vaccination of

children entering the 1st standard and all new admissions

2; Maintenance of protection, i.c. perin-lic booster doses to children

in standards 4 and 8.

Protection of children before they leave school, i.e. .booster

doses to children in standard 101 When these groups are

immunized annually, together with all new admissions, the total

school population is protected within, n- few years.

3.

TYPES OF IMI.UNI7..1TIONS ADMINISTERED

12.16.2.

**

The types of immunizations that are administered in ;n school are

usually similar to the ones that are.ndministerec to pre-school children with

one important difference.

Instead of DPT, children in school are given DT

since they no longer need protection against

wir oping cough. ■ The immunizations,.

that are usually administered in school, ares

-

i. Diphtheria-Tetanus(DT) (primary and booster)

ii. Smallpox vaccination(primary and revaccination)

. iii. BCG vaccination (primary .and booster)

iv. Poliomyelitis oral vaccinc(primary and booster) given only

when there is a high incidence of the disease

When an unusatelly large number of cholera or typhoid fever cases occur in

the community, immunizations against these diseases shouldialso be administered

to children in schools.

■ •

12.16.3

ARRANGING AND CONDUCTING THE PROGRAMME

’

*.

-

'

•

1 r •

The dates for the immunization programme are usually set by the Health

Assistant(Malel after he has received the suggested dates from the principal of

the school. These dates may change from year to year depending bn the request

of the teachers, other programme responsibilities and special campaigns, as

well as the outbreak of particular diseases in the area. ■ •

'

Your specific activities related to‘the school immunization programme

will generally include the following”’

1. Identification of the target population for BCG and smallpox by

doing a scar survey. The toachers can also be shown how to look for

scars.so that, they can help to identify the unprotected in their

classrooms and in the homes.

■

'

.

Compiling a list of •hildron who are t ■ be given immunizations. This

shpuld be done classriecu

a

•

*

.

3. Informing the Health Assistant (Male)’ about the suggested dates

for the programme And the number of children to be given BCG, smallpox

and DT vaccination. ’•

'

■

2.

-

-

4.

Obtaining visual aids on immuhizat ion . from the Primary Health Centre

for health education programmes in th:, school

5.

Assisting the teachers in the school t> plan and carry out health

education activities related to immunization in their classrooms,

covering such topics as why immunization is necessary,how.it is

done, and what happens afterwards.

6.

Inferring children, teachers, and other school personnel

where iraunizntions can bo obtained for ether neribers of

their families.

7 • Assisting the Health Assistant (bfalo) in the adninistration of the innuni zatipns, preparing the equipment, recons

tituting the vaccine, and screening children to identify

those who arc -ill .

8. Making armngericnts for recording the icrunizcticns

adidnistered in each school. This t ay be in the fora of

a register.

9.

Sub, itting the required reports to the Health Assistant

(Iidle) and to the Primary Her 1th Center.

FEMEMBER, WELL-Il'ffORiiED TEACIF.TS AID CHIj.OMAT PAM BE iSLHHiL IN

FINDING OUT THE UFP’OTECTZD AND IN FEJ SUADING FIJEiiTS AID RELATTES TO OBTAIN IM UCTZATIONS F(T OIHlfr CHILDrEN AT HOiE.

12 .17

PROMOTING THE USE GF IllUNIZATIONS IN THE 03EUMTY

Instead of conducting a separate canpaign for inferring

the coraunity a bout the value of inmnizations, it would, be norc prac

tical and effective to incorporate tils topic with your other educat

ional activities pertaining to the prevention of communicable diseases

or fatdly planning as a part of family welfare.

-

IN TALKS SEVEN TO IIUEVIjUAIS AND GROUPS DURING ”TI( FEG’lLAR.

HOUSE-TO-HOUSE VISITS,- YOU SHOULD INCLUDE '.HE VALUE CF I..i UNI

ATION 107 ailLDTEN AND B'.RGIW WOMEN.

The usual orientation Sessions that you conduct for the

ccncrunity loaders and influential individuals regarding ether health

services should also inclu’e the subject of innrnizpticn. In this way,

you will be able to g t their support for this important health nca.sure

for preventing the spread of cor.runica.hle diseases. The help, of the

connunity centers may be taken for preparing suitable visual aids

for use in such sessions. Attractive aucic visual aids • ay also be

obatinod fron the Block Health Assistant.

Together with the Health Worker (Ferric) ;• cu should syste

matically teach- Ider children in schools, their teefhers, and Lalwadi

workers about the value of innniza.ticns since th ose raccps often have

close contact with young children’.-he comprise the targ./t population

for innurization. Educating lais with regard tc 'l.o need for adminis

tering tetanus toxoid to pregnant women is also an important part of

your health educational activities.

12.17.1

WOHITG WITH THE HEALTH W CEKEE (FEMALE; .

As you are aware, in the intensive -rea the Health Worker

(Female) will be administering iixiunizations to the newborn and to

pregnant women. Since you will both be visiting tho same families,

there is a possibility of duplicating y-v? efforts. It is, therefore,

necessary for ycu and the Health Worker (Female) to meet periodically

nd decide on your respective rcs-cnci’ ilitios regarding tire innuxiiaaa.

tion of the non’ ers of each family.

......................Contd/28-

12.18

RECORDS A?" PilR'ATS

You arc expected to submit ti the Primary Health Centre

a monthly report of your activities regarding immunizations given.

This should cover the following points;

1. Numbers and types of I eneficiarios .jivon various types

of immunizations, i.c. zero to one year, one to five

years, pregnant women, scl:-xl-going children, and' other

groups in the co; s unity given smallpox vaccination

(Primary and revaccination), DPT, IT, Tetanus toxoid,

BCG, Poliomyelitis, TAB, Cholera and any other vacci

nation.

2.

Eecoipt, issue and balance of stock of vaccine. IN

order to submit those reports you will 1x3 required to

maintain the: follrwing root rds:

i. Individual health c.

f~r ■chil'h’cn and mothers

to be kept in the family folder.

.ii. Health cards for school children.

iii. Register of individuals receiving immunization*

iv. Stock register of vaccines received and used.

o

Gh 3--K

GOVERNMENT OF, KARNATAKA •

Directorate of Health & F,.W.Service

NO,uiP.187/88-89

Bangalore-9.-Dated: 5th April 1'89.

■

CIRCULAR

'

Immunization Targest for the year

1989-90 and guidelines.

SUB:

Please find enclosed herewith the immunization targets and vac

cine allocation for the year .1989-90,

Following guidelines are Issued

for implementation of the programme,.

1•

TARGETS :

a)

‘

•

Targets for primary immunization

i)

:

1981 census population has been projected to

mid 1.989-90 based on the Expert Committee

report on. Population projections.

ii)

The pregnant women beneficiaries are calculated

taking 27.3 per thousand estimated population as.

. -

birth rate i.e. pregnant -woman = estimated popu

lation x .0273.

iii)

j'

Eligible infants are worked out based on the sur-

-

vivors at the age of one year taking 84 infant

mortality rate per thousand live births.

Margin

is given for the still births out of the total

The actual survivor rate'at the age'of

women.

one year works out to 911.66 per thousand live births.

iv)

All the estimated pregnant women and infant sur-

- , vivors at the age of one year are targetted for

full immunization coverages.

Efforts should be

made to achieve 100% of the estimated beneficiary.

However in case of infant coverages' upto atleast

85% may-be acceptable be'cause' of the' multiple an

tigen, multiple dose, drop outs .etc;,

and herd

immunity.

v)

Though estimates are made and communicated if the

enumeration is complete the local authorities may

adopt higher or lower targets'-based on the actuals

enumerated.

However the responsibility of defend- y

ing the altered targets rests with the local authorities.

/

TT ■

BOOSTER DOSE

:

'

'

The achievements of the booster dose and for the children

receiving three doses of DPT and Polio during the year 1987-88 in .

the year 1988-89 has been aroung 50% only.

All out efforts must be

made to give booster dose to all infants who had received third dose

of DPT and Polio in the year 1988-89.;

1989-90.

firing .the ensuing year of

2

III.

Targets for Secondary Immunization- :

Survivors at the different age groups (5,