SDA-RF-CH-4.11.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

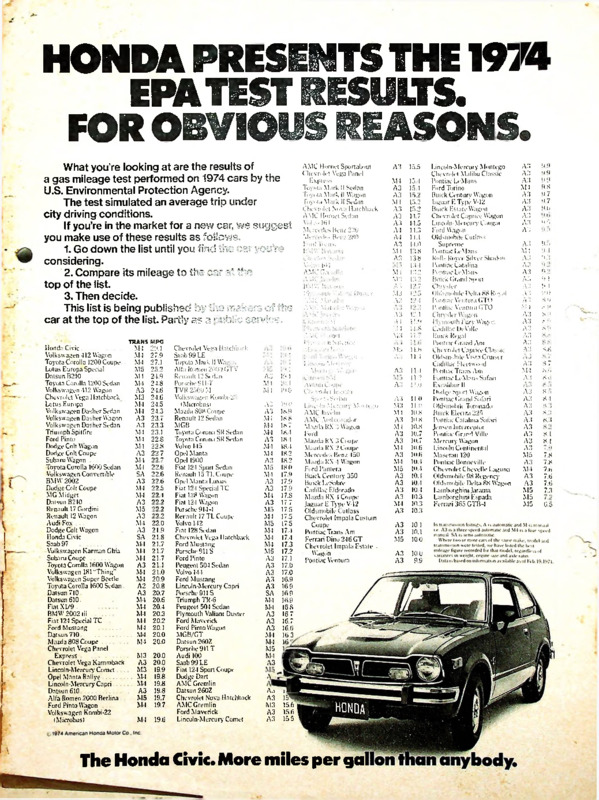

HONDA PRESENTS THE 191

ERA TEST RESULTS.

FOR OBVIOUS REASONS

What you’re looking at are the results of

a gas mileage test performed on 1974 cars by the

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The test simulated an average trip under

city driving conditions.

If you’re in the market for a new car, we suggest

you make use of these results as follows.

1. Go down the list until you find >

considering.

2. Compare its mileage to th

top of the list.

3. Then decide.

This list is being published

car at the top of the list. Partly as a ■

TRAMS P.PG

Honda Civic.

Ml 29.1

Volkswagen 412 Wagon .

M4 27 9

Toyota Corolla 1200 Coupe

Ml 27.1

Lotus Europa Special

M5 25.2

Datsun B210

Ml 24.9

Toyota Corolla 1200 Sedan

Ml 24.8

Volkswagen 412 Wagon

A3 24.6

Chevrolet Vega Hatchback

M3 24.6

Lotus Europa

Ml 24.5

Volkswagen Dasher Sedan

Ml 24.3

Volkswagen Dasher Wagon

A3 23.7

Volkswagen Dasher Sedan

A3 23.3

Triumph Spitfire

Ml 23.1

Ford Pinto

Ml 22.8

Dodge Colt Wagon

Ml 228

Dodge Colt Coupe

A3 22.7

Subaru Wagon .

Ml 99 7

Toyota Corolla 1600 Sedan

Ml 22.6

Volkswagen Convertible

SA 22.6

BMW 2002

A3 22.6

Dodge Colt Coupe

M1 22.5

MG Midget

Ml 99 4

Datsun B210

A3 22 2

Renault 17 Gordini

M5 22 2

Renault 12 Wagon

A3 99 9

Audi Fox . .

Ml 22.6

Dodge Colt Wagon

A3 21.9

Honda Civic

SA 218

Saab 97

.

. ..

Ml 21.7

Volkswagen Karman Ghia

Ml 21.7

Subaru Coupe . ..

Ml 21.7

Toyota Corolla 1600 W'agon

A3 21 1

Volkswagen 181“Thing"

Ml 21.0

Volkswagen Super Beetle

Ml 20.9

Toyota Corolla 1600 Sedan.

A2 20.8

Datsun 710

A3 20.7

Datsun 610.

Ml 20.6

Fiat Xl/9 .

M4 20.4

BMW' 2002 tii

...

M4 20.3

Fiat 124 Special TC

. Ml 20.2

Ford Mustang

...............

M4 20.1

Datsun 710........................

Ml 20.0

Mazda 808 Coupe .

. . . M4 20.0

Chevrolet Vega Panel

Express........................ . M3 20.0

Chevrolet Vega Kammback

A3 20.0

Lincoln-Mercury Comet . . M3 19.9

Ope) .Manta Rallye........... . . M4 19.8

Ml 19.8

Lincoln-Mercury Capri ..

A3 19.8

Datsun 610

....................

M5 19.7

Alfa Romeo 2000 Berlina

Ml 19.7

Ford Pinto W'agon

Volkswagen Kombi-22

t Microbus)

Ml 19.6

Chevrolet Vega Hnlchbirk

Saab 99 LE

Toyota Mark I! Wagon

Alfa Romeo 2000 G 1 '•

Renault 12 Sedan

Porsche 911-3'

TVR 2500 M

Volkswagen Kombi-22

(Microbus)

Mazda 808 Coupe

Renault 12 Sedan

MGB

Toyota Corona SR Sedan

Toyota Corona SR Sedan

Volvo 1-15

Opel Manta

Opel 1900

Hat 121 Sport Sedan

Renault 15 TL Coupe

Opel Manta Luxus

Fiat 121 Special 1'C

Fiat 128 W'agon

Fiat 121 W'agon

Porsche 914-1

Renault 17 TL Coupe

Volvo 142

Fiat 128 Sedan

Chevrolet Vega Hatchback

Ford Mustang

Porsche 911S

Ford Pinto

Peugeot 504 Sedan

Volvo 14-1

Ford Mustang

Lincoln-Mercury Capri

Porsche 911 S

Triumph TR-6

Peugeot 501 Sedan

Plymouth Valiant Duster

Ford Maverick

Ford Pinto W'agon

MGB/GT

Datsun 260Z

Porsche 911 T

Audi 100

Saab 99 LE

Fiat 124 Sport Coupe

Dodge Dart

AMC Gremlin

Datsun 260Z

Chevrolet Nova Hatchback

AMC Gremlin

Ford Maverick

Lincoln-Mercury Comet

..

? 15

A3

M1

M1

A3

A3

M1

Ml

Ml

A3

Ml

M1

A3

M5

M1

A3

A3

Ml

A3

M5

Ml

M5

Ml

Ml

Ml

M5

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

SA

Ml

Ml

A3

A3

A3

Ml

Ml

MS

Ml

A3

'll

I

*I

19 1

19.1

l‘».O

19 0

18.9

18.8

18 7

18.1

18.1

18.4

18 2

18.2

18.0

17.9

17.9

17.9

17.8

17 7

17 5

17.5

17.5

17.4

17.4

17.3

172

17.1

17.0

17.0

16.9

16.9

16.9

16.9

16.8

16.7

16.7

16.6

16.3

16

AMC Hornet Sportabout

Chevrolet Vega Panel

Express

Toyota Mark 11 Sedan

Toyota Mark II Wagon

Toyota Mark II Sedan

Chevrolet Nova Hatchback

AMC Hornet Sedan

Volvo Hi!

Mercedes Benz 230

Merced— B.-ez 280

Ford Torino

BMW

Ca.Cvi .x,k-r.

V.-iv. j.;»

AMCGamlm

A »•» oi'

BMW B,,'..m,i

I’iv; lolitli V.il. -n i/Dr'.i r

\MC Mat.id

A Ml M.ii al.'r W,.g. j

'.•■in

"cl; b'.|

.'.'.•C

a net

I'! ,1 . a i: S ilc'.iih.’

M.- ... .:•!>; ■, >

1'

" ■ ■ ; , ,• - t)

kineoiii-'.h-irr.'v

\ 1* 1 0 •

’-( | ■

Avanti C;-upe

Che. vrol<i liiuial i

Spot is Sedan

l.inc-l.'i-Mcrcury M-mu .;<>

AMC JavMin

AMC Amba^ador

Mazda RX 3 Wagon

Eord

Mazda RX 3 Coupe

Mazda RX 2 Coupe

Mercedes Benz 150

Mazda RX 4 Wagon

Ford Pantera

Buick Century 350

Buick LeSabre

Cadillac Eldorado

Mazda RX 1 Coupe

Jaguar E Type V-12

Oldsmobile Cutlass

Chevrolet Impala Custom

Coupe

Pontiac Trans Am

Ferrari Dino 2-I6 GT

Chevrolet Impala Estate .

Wagon

Pontiac Ventura

K*

A-

A.>

A3

M3

A3

A3

15^1

15.6 ■

15.6 1

155 1

HONDA

The Honda Civic. More miles per gal

A3

15.5

Ml

A3

A3

Ml

A3

A3

A3

Al

Al

A3

Ml

A3

A' 1

xii

M3

MA

M3

A3

15 1

15.1

15.2

15.2

15.2

11.7

11.5

11.3

11.1

11.0

A3

AI

Ml

M3

• >

Mb

A3

A3

IMS

138

13 I

13.2

13 2

12.7

12.5

12 1

1•’

12 1

r..M

'1 s

11/

ii.6

11 1

A3

11 I

11 2

’1 .0

A3

M3

Ml

A3

Ml

A3

A3

Ml

A3

Ml

M5

A3

A3

A3

A3

Ml

A3

11 0

11.0

10.8

10.8

10.8

10.7

10.7

10 6

10 6

10.1

10.4

10.1

10.1

10 1

10.3

10.3

10.3

A3

A3

M5

10.1

10.1

10.0

A3

A3

10.0

9.9

Lincoln-Mercury Montego

Chevrolet Malibu Classic

Pontiac Le.Mans

Ford Torino

Buick Century' Wagon

Jaguar E Type V-12

Buick Estate Wagon

Chevrolet Caprice Wagon

Lincoln-Mercury Cougar

Ford Wagon

Oldsmobile Cutlass

Supreme

Pontiac Le.Mans

Rolls Royce Silver Shadow

Pontiac Catalina

Pontiac Le.Mans

Buick Grand Sport

Chrysler

Oldsmobile Delta 88 Royal

Pontiac Ventura GTO

Pontiac Ventura GTO

Chrysler Wagon

Plymouth Furv Wagon

Cadillac DeViile

Buick Regal

Pontiac Grand Am

Chevrolet Caprice Classic

Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser

Cadillac Fleetwood

Pontiac Trans Am

Pontiac Le.Mans Safari

Excalibur II

Dixlge Sport Wagon

Pontiac Grand Safari

(Hdsmobile Toronado

Buick Electra 225

Pontiac Catalina Safari

Jensen Inti rceplor

Pontiac Grand Ville

Mercury Wagon

Lincoln Continental

Maserati 120

Pontiac Bonneville

Chevrolet Chevellc Laguna

Oldsmobile 98 Regency'

Oldsmobile Delta 88 Wagon

Lamborghini Jarama

Lamborghini Espada

Ferrari 365 GTB-4

A3

A3

A3

Ml

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

9.9

99

99

98

9.7

9.7

9.6

A3

Ml

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A’.

ri i

•Ml

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

9.;>

9 1

9.3

'i .

Q ■>

91

9 1

‘.’0

89

c9

S.9

.*■ '•

89

A3

Ml

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

A3

M5

A3

Ml

A3

A3

M5

M5

M5

95

•i .>

8.8

87

;■'>■ >

Kd

.i

8 ;>

8 1

s ,

s ■;

8.3

81

81

, •i

7.8

7.8

7.o

7.6

7.6

7.3

0

65

MEDICINE

called “endogenous” form of depression,

which seems to arise without any evi

dence of a traumatic life experience to

account for it, is rarely diagnosed in

youngsters. In nearly all cases, childhood

depression is “reactive,” associated with

an event in the child's life, usually in

volving the parents. “The child-psychia

try books of twenty years ago may not

have even mentioned it,” says Dr.

Leon Cytryn of the George Washington

University School of Medicine. “But

we're beginning to realize that there are

many depressed children and we suspect

a lot of them become depressed adoles

cents and depressed adults.”

Its most pathetic form is the “anaclitic” (from the Greek, “leaning on”)

depression that is observed in infants

separated from their mothers in the first

six months of life and raised in institu

of Columbia, may be overlooked by (he

parents for months, but psychological

testing may bring out the true extent of

the child’s depression quite quickly.

Asked to draw a picture and then tell

a story about it, an 8-year-old boy

brought to McKnew recently drew a pic

ture of a small whale. Then he told how

the whale was lost and was trying to get

home. lie tried to hitch a ride with an

other whale, but slipped off its back.

Then he joined a school of whales, but

they swam too fast for him to keep up.

So the whale in the picture was lying

with another whale, also lost, waiting to

be found. “If an adult told you a story

like that,” notes McKnew, “you’d imme

diately give him antidepressants.”

Depression in children almost always

follows a sense of loss. Acute reactions

occur, understandably enough, after the

situations that may be at the bottom of

his problem. The play-therapy concept is

based on the common-sense notion that

play is a more natural mode of expression

for a child than verbalizing.dreams.

One of the most common problems

that call for psychiatric attention in chil

dren is school phobia. It may be a symp

tom of depression, but may also have a

far more readily treated cause. Dr. Lee

Salk recalls the case of Stephen, age 5,

who lived on the twelfth floor of a New

York apartment with his parents and

grandparents, who continually expressed

their fear of burglars. His mother warned

him constantly of the evils that could

befall him when he went out to play and

often warned him not to let the elevator

doors close on him. Soon, he had devel

oped a fear of both burglars and eleva

tors, and was afraid to go out alone.

Not surprisingly, his anxieties contin-.

ued at school; his mother would drop!

him off at the door but could count on

his coming out again minutes later. The

problem, as Salk explained, was that the

child had become totally helpless outside

his mother’s purview and dependent on

her attention—a common source of school

phobias. Salk explained to the overanx

ious mother that Stephen should hear

fewer dire predictions about the world

outside and be allowed more independ

ence. In weeks, he was spending full

days in school.

The relief of the most serious problems

Robert R. McElroy—Newsweek

Keep trying: TEACCII therapists working with a difficult patient

tions where they get little attention

and neural stimulation. These babies,

starved for warmth, withdraw and dis

play some of the signs of autism, such

as monotonous rocking and, as they grow

older, difficulties with language. They

will improve with regard to language and

motor skills if moved to a favorable en

vironment, but the profound emotional

impact of their early experience may

be devastating.

Beyond the age of 6, the depressed

child may show signs of sadness, social

withdrawal and apathy similar to the

symptoms of adult depression. But usual

ly it is masked. In young children it

may be expressed in psychosomatic head

aches or vomiting; in older children it

may show up in aggressive behavior,

truancy, vandalism and, particularly

among girls, sexual promiscuity. The pe

riodic episodes of sadness that are the

tip-off, notes Dr. Donald H. McKnew Jr.

of the Children’s Hospital of the District

58

death of a parent or close relative, divorce

or a move to a new community. Often,

they are more like grief reactions and

disappear with time. But many depres

sions occur because the child senses a

withdrawal of interest and affection

through frequent separations from, say, a

father who travels a lot; or because a

parent conveys an attitude of rejection or

deprecation. In most instances, one or

another of the parents has a depressed

personality, McKnew observes.

Antidepressant medication is seldom

prescribed for children. Most often, psy

chiatric counseling, involving both parent

and child, is required. Fortunately, psy

chotherapy usually is effective. Here psy

chiatrists have devised methods that

sidestep the completely verbal methods

of communication used in more adult

forms of psychotherapy. One of the most

widely used is play therapy, in which the

child uses a variety of toys to expose,

under the therapist’s watchful eye, the

of troubled children—autism, schizophre

nia and hyperkinesis—must await much

further research into the physical and

biochemical mysteries of the brain. What

is required is the same sort of commit

ment on the part of private agencies and

the government that. has lately been

mounted in the war against cancer and

heart disease. At the same time, the

children who are already victims of these

tragic disabilities must be afforded the

special training that will give them the

best chance of finding a useful life. In

view of the fact that 10 per cent of the

nation’s children are now destined to

develop some form of emotional disabili

ty, the effort would seem a small price

to pay.

Meanwhile, in the view of child ex

perts, there is a good deal that parents

can do to protect their children from

many kinds of serious emotional damage.

First, says Salk, is to recognize the child’s

dependency during the first year , of life

and respond unstintingly to his need for

warmth and affection. Once the child

has learned to trust his parents, it is time

to set limits that prepare him for his en

counters with the world. To contend with

the child’s impulse to explore his environ

ment, knocking over countless glasses of

milk as he goes, may be a frustrating and

seemingly endless task, Salk concedes.

“But,” he adds, “for the parent who loves

his child, has patience and can still see

the world through a child’s eyes, the re

wards are beyond measure.’’

Newsweek, April 8, 1974

MEDICINE

homes. Through a one-way glass, thera

pists show parents how to reward the

child with hugs, or candy, when he per

forms an expected task. The early exer

cises focus on such basics as looking the

parent in the eye, learning concepts

such as “same” and “different” by sorting

knives, forks or other objects, and learn

ing to identify objects with words. Par

ents are taught to distract their children

from psychotic movement, such as rock

ing. When a child fails to respond, the

parent is assured that it is correct to

show displeasure.

The road to advancement is painfully

arduous, but many children do improve.

Michael, a brown-haired 5-year-old,

couldn’t talk and was unmanageable

when he entered TEACCH a year and a

half ago. Now he has a vocabulary of

750 words and behaves well enough to

attend a special school. David, who had

an IQ of 70 when treatment began nine

years ago, now scores 30 points higher

and is getting average grades at a regular

private school. "By getting to them ear

ly,” says Schopler, “some children can be

salvaged.”

SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia in children bears some

resemblance to autism and many psy

chiatrists consider them related. The

child may be withdrawn and fail to use

words. He may also be overactive and

aggressive. Unlike schizophrenic adults,

56

children affected by the dis

order don’t usually hear voic

es or otherwise hallucinate.

But they do fantasize, ac

cording to psychiatrists, and

they often can’t distinguish

between the real and the

imaginary.

In the past, psychoanalysts

tended to ascribe schizophre

nia largely to the influence of

a castrating “schizophrenogenic” mother. Many psychi

atrists today believe the emo

tional environment of the

home may play a greater

part in tire disorder than is

the case with autism. But a

growing number of the ex

perts are now persuaded

that a genetic defect, cou

pled with neurologic impair

ment of some kind, constitutes

the underlying cause of the

disorder.

The influence of genetics

in childhood schizophrenia

has been demonstrated by

Dr. David Rosenthal of the

National Institute of Mental

Health. Rosenthal compared

children with a schizophrenic

mother or father who were

raised by normal adoptive

parents with adopted chil

dren of normal parents. In

this way, the possible envi

ronmental influence of par

enting was equalized. It

turned out that the children of psychotic

parents in the study had about twice

the incidence of schizophrenic disorders

as did those of normal parents.

The outlook for the schizophrenic child

is considerable brighter than it is for the

autistic. Many of these children are ed

ucable and never have to be institution

alized. Brooklyn’s League School is typi

cal of centers across the country that

use a “psycho-educational” approach to

treating schizophrenic children while the

child lives at home.

Children are usually accepted at the

school between the ages of 3 and 5 and

most stay several years. Tommy Harper

of Brooklyn began when he was in

second grade. Throughout his childhood

he had displayed a vicious temper. He

threw blocks at his teachers when he

couldn’t get his way, and once pounced

on a little girl and broke one of her teeth.

Consigned to the cloakroom, he was lat

er found sitting on a shelf, beating him

self over the head with a toy gun and

crying, “I want to die.”

With the structured environment and

intensive individual attention he re

ceived at the League School, Tommy

settled down and learned to read, do

math and function in groups. He was

bright, a fast learner and in four years

he was back in regular school. Today, at

15, Tommy is still a bit of a loner. But he

can play sports such as football and not

lose his temper in defeat; more impor-

taut, he is an honor student. Dr. Carl

Fenichel, director of the school, esti

mates that about 80 per cent of th'e

children at the school had been des

tined for state institutions. Now, the ma

jority go on to satisfactory jobs, regular

schools and some even to college.

HYPERKINESIS

Of the more serious childhood behav

ior disorders, hyperkinesis has become

the most widely publicized of late be

cause it is being diagnosed in an increas

ing number of schoolchildren. The symp

toms may be discernible in infancy, when

the mother finds that her baby is un

usually restless and difficult to soothe.

They become more obvious when he

reaches school age. Typically, hyperki

netic children are highly excitable, easily

distracted and impulsive. They have

trouble concentrating and therefore be

come disruptive in the classroom. Be-j

cause they are failures in their work,

they develop the emotional side effect

of low self-esteem and frequently com

pensate by delinquent acting-out. “These

youngsters consider themselves worth

less,” says Dr. Lawrence Taft of the Col

lege of Medicine and Dentistry of New

Jersey, “because everyone is telling them

they’re no good.”

Hyperkinesis seems to run in families,

but there is also evidence that the disor

der may be related to minimal brain

damage, possibly occurring at the time

of birth or after a viral infection such

as measles. There is also evidence that

lead intoxication may produce hyper

kinesis among ghetto children who ha

bitually put pieces of peeling lead-based

paint into their mouths.

At least a third of hyperkinetic chil

dren show marked improvement on daily

doses of stimulants such as ampheta

mines and even coffee (Newsweek,

Oct. 8, 1973). Just how the stimulants

have this paradoxical calming effect isn’t

known, but they seem to improve the

child's ability to concentrate.

Dosing large numbers of schoolchil

dren with the very drugs that constitute

a major abuse problem in the U.S. has

stirred controversy among many parents

and even some psychiatrists. Some

charge that the stimulants are prescribed

as “conformity pills” for rebellious chil

dren. The drugs may produce side ef

fects, including loss of appetite and

sleeping difficulties. As a result, children

who take them for several years may not

grow as tall as they might have other

wise. But the effect of the drugs can be

so dramatic, says Taft, “that you won

der whether an extra bit of height is all

that important.”

DEPRESSION

Among the childhood emotional dis

orders in which the relationship with

the parents is of unquestioned impor

tance, the outstanding example is de

pression. Some experts estimate that de

pression accounts for at least a quarter of

the troubled children they see. The so-

o

Newsweek, April 8, 1974

.. . learning to speak with the gentle help of Danielle Berger

job over to the parents, consulting oc

casionally to see how they were doing.

But Connie found she couldn’t work with

Shawn. “Every’ time I tried, it just hurt,”

she says. “Some parents can’t do it.”

Connie, in fact, felt the need to see a

psychiatrist herself—and it was a wrench

ing experience. “The first thing he asked

me,” she recalls, “was ‘How do you

feel about Shawm?’ I couldn’t answer.”

Finally, thanks to two consultants to

the Los Angeles County Autism Project,

Alan Instil and Danielle Berger, who

have worked with Shawn for the past

year and a half, the child is slowly im

proving. Danielle demonstrated the con

ditioning technique one afternoon re

cently in the Lapin home. Holding a

package of sliced cheese, Shawn’s favor

ite food, she knelt on the floor and in

structed the child to say, “I love mom

my.” Shawn mumbled unintelligibly and

Danielle withdrew the cheese and

frowned. Then she repeated the com

mand, with similar results. Finally, after

half an hour, Shawn formed the right

words and earned his piece of cheese.

Shawn has learned his tiny repertoire

of skills: he can now look his parents in

the eye, he is toilet-trained, he can dress

himself in three minutes instead of the

45 it used to take and he can say about

fifteen words. It is a pathetically small

set of achievements for a normal 5-yearold, but according to the standards by

which the autistic child is judged, it

represents dramatic progress. And the

Lapins haven’t given up.

. .. and dressing himself at last

or fight back. Some children fight back,

’but the autistic child plays dead.”

But the current trend is away from

the Freudian view. Recent studies show

that the parents of autistic children dis

play no emotional traits that set them

apart. “The only differences these par

ents show from other parents,” notes Dr.

Eric Schopler of the University of North

Carolina School of Medicine, “is that

they are all under stress themselves be

cause they have a difficult child.”

Moreover, researchers have made a

number of observations that suggest that

autism is more of a neurologic problem

than an emotional one. A number of

autistics, for example, show so-called.

“soft signs” of neurologic impairment,

such as poor muscle tone, uncoordination

and exaggerated knee-jerk responses.

Drs. Edward Omitz and Edward Ritvo

of the UCLA School of Medicine have

studied the eye reactions of normal and

autistic children placed in a spinning

chair. If the chair spins to the left, a nor

mal person’s eyes will move to the right,

snap back and wander right again; when

the chair stops, the eyes will reverse

their movement. Autistic children show

the same pattern of eye movement, but

for a much shorter period. This suggests

that the disorder involves a maturational

lag in neural development. “The over

whelming evidence,” says Ornitz, “is that

this is an organic condition.”

Because of the evidence suggesting

that a physical abnormality is involved,

there is a tendency among experts to

day to regard autism as a form of mental

retardation rather than an emotional ill

ness. “Autistic children both will not and

cannot perform many tasks,” says Omitz.

About 75 per cent of autistics remain re

tarded through life, he notes, and more

than half eventually are institutionalized.

It is the parents of an autistic child

who suffer the most. Many of them spend

years going from specialist to specialist in

a fruitless search for cures. At first, a

pediatrician may tell them their child is

deaf or simply “spoiled.” Psychoanalysts

may suggest that they, the parents, need

treatment as much as their child does,

only adding to an already unbearable

burden of guilt. Psychiatrists may give

the child tranquilizers, stimulants or even

electroshock therapy. But the child re

mains his autistic self. Recently, some

physicians have prescribed massive doses

of such B vitamins as niacinamide, pyri

doxine and pantothenic acid for both au

tistic and schizophrenic children. But

most experts insist that the so-called

megavitamin therapy has no scientific

basis. “This is the false-hopes business,”

says one researcher, “and it causes a lot

of anguish.” “Every time you go to some

one you’re desperate,” says Connie Lapin,

a Los Angeles mother of an autistic son'

(box). “They say they’ll treat him. But

then they can’t reach him and they

give up.”

But while there is no specific treat

ment for autism, a number of centers

now offer special training that has pro

duced promising results in some children.

One of them is TEACCH (Treatment

and Education of Autistic and relat

ed Communications handicapped Chil

dren), begun by Drs. Eric Schopler and

Robert J. Reichler eight years ago and

now funded by the State of North Caro

lina. One of the outstanding features of

the program, according to Schopler, is the

participation of parents as co-therapists

in training their own children.

Basically, the parents are instructed

how to use reward-and-punishment be

havior modification to train their children

during daily half-hour sessions in their

April 8, 1974

55

Milestones of progress: Crying in a moment of frustration . . . responding to a teacher at his special school . . .

never could hold onto his bottle, recalls

Connie Lapin, 34. But on the other

hand, Shawn had begun to walk even

before his older brother and could say

three or four words. So there seemed to

be no reason for concern. Then a sudden

change in Shawn occurred. “One day he

tuned everything out,” his mother says.

“He didn’t respond to his name any

more. He didn’t talk any more.”

Soon, Shawn’s behavior was growing

worse. He cried all night, and Connie and

her husband, Harvey, a Los Angeles den

tist, split four-hour shifts to quiet him.

pushed his parent away.

Connie and Harvey then began the

tormenting, purgatorial ritual that most

parents of troubled youngsters seem to

follow—making the rounds of experts.

After several false leads, the Neuropsy

chiatric Institute at UCLA finally di

agnosed Shawn as an autistic child.

The last stop for the Lapins in their

search for help was the office of Dr. Ivar

Lovaas of UCLA. A Norwegian-born

psychologist, Lovaas has specialized for

the past twelve years in changing the

behavior of autistic children through

reward-and-punishment “operant condi

tioning.” Lovaas was kind but blunt about

Shawn’s prognosis. “This is not going to

cure Shawn,” he told the Lapins. “All it

will do is modify his behavior, and prob

ably get him into a better institution.”

“It was Ivar who brought me down to

earth,” says Harvey. “All that work and

that’s all it would do—get him into a bet

ter institution. It blew my mind. But as

a parent, what are you going to do? The

kid didn’t ask to be bom, and he certain

ly didn’t ask to be autistic. I thought I

had to do what I could.”

Lovaas and his assistants, usually

UCLA undergraduates, spent several

sessions a week with the child and his

parents, both at tire clinic and in the

home. After six months, they turned the

likely that he himself will be aggressive.”

Because there is no one cause of child

hood emotional problems, many methods

of treatment have evolved in recent

Lears. Since a young child can hardly

be expected to lie still for long, deep

probing sessions of analysis on the

couch, psychiatrists have developed oth

er ways to get at the source of his trou

bles. One involves watching how he

plays with his toys or interpreting the

pictures he draws. Other therapists ig

nore the deep-rooted sources of a child’s

problem and use reward-and-punishment

conditioning techniques to modify the

child’s abnormal behavior. In many cases,

the children with the overactivity syn

drome of hyperkinesis can be helped

with drugs. Unfortunately, no truly ef

fective treatment has yet been found for

the child afflicted with the most devas

tating of all the disorders—autism.

their environment. As an infant, the autis

tic child may go limp or rigid when his

mother picks him up. He may seem deaf

to some sounds but not to others. He

may show no sensitivity to pain, even to

the extent that he can blister his fingers

on a hot stove without flinching. For long

periods, he may rock monotonously back

and forth, flap his hands in front of his

face, walk on tire tips of his toes or whirl

about like a dervish.

Autistics show unusual deviations in

reaching the milestones of development.

They may never sit up by themselves or

crawl, but instead suddenly start walk

ing. Some start to talk, but then abrupt

ly stop using language altogether, or only

echo words and phrases they have over

heard. They reverse personal pronouns,

such as saying “you” for “me.” They

seldom look anyone in the eye. When

an autistic child wants something, he

may, without looking at his mother,

steer her hand toward the object as if

manipulating a pair of pliers. Because

many autistic children show certain

“splinter skills” above and beyond their

otherwise poor level of functioning—such

as the ability to rattle off strings of num

bers—they have traditionally not been

classified as retarded or brain-damaged.

After Kanner’s description of autism

was published, some psychiatrists ob

served that the parents of such children

tended to be intellectual, emotionally

detached and with a tendency to think

in abstractions. With the prevailing in

fluence of Freud on child psychiatry at

the time, it was hardly surprising that

the condition should be blamed on these

"refrigerator parents.” Autism was sup

posed to result from rejection of the

child by the mother at an early stage in

infancy. Dr. Bruno Bettelheim, a dis

tinguished psychoanalyst who recently

retired after 30 years of dealing with

autistic children at the University of

Chicago’s Orthogenic School, is a force

ful exponent of the Freudian view.

The autistic child has an inherited pre

disposition to emotional trauma, Bettel

heim says, but unconscious rejection by

the mother is the major traumatizing

event. The parents, he says, tend to deal

with the child in a mechanistic way, out

of a sense of obligation rather than gen

uine affection. “This is interpreted by

the child as a feeling he shouldn’t be

alive,” says Bettelheim. “When animals

are threatened, they either play possum

The Silent Struggle of Shawn Lapin

1, Shawn Lapin seemed But every time one of them picked him

At tothebeagea ofhealthy,

normal child. He up, his body became rigid and he

AUTISM

The term “early infantile autism,” from

the Greek for “self,” was coined 30 years

ago by Dr. Leo Kanner of Johns Hopkins

to describe a group of disturbed schizo

phrenic children who showed a uniform

pattern of disabilities in responding to

54

Newsweek

770,000. "The drift,” says Noshpitz, “is

toward seeing more and more very dis

turbed children, youngsters who need

residential treatment." And psychiatrists

in private practice note similar trends.

“There is now a widening scope of pa

tients with childhood disturbances,” says

one veteran New York psychoanalyst,

“and it is not just because more people

are deciding to put their children in

therapy."

Frend, who preached that the root

causes of emotional disorders were to be

found largely in a disturbed relationship

between parent and child in early life, is

no longer quite so predominant an influ

ence on child-care professionals. The

more eclectic psychologists and psychia

trists hold that childhood mental ills

seem to arise from three intertwining in

fluences: predisposing physical and he

reditary' factors, forces within the family

—including the Freudian traumas—and

stresses imposed by contemporary life.

“The fortunate child,” says Ner Littner of

Chicago’s Institute of Psychoanalysis, “is

the one with good heredity and adequate

care provided by two parents who are

able to recognize and meet the child’s

needs in early life, and a minimum of

chronic, overwhelming stress situations

as the child grows up.”

But now more than ever before, the

triad of forces seems to conspire against

the emotional well-being of the Ameri

can child. First, there is a growing rec

ognition that children born prematurely

or as a result of difficult labor, those

suffering from complications of measles

and other viral infections and those

raised by parents who are themselves

victims of mental disorders run a high

r»\k nf pmpbinnnl dicti.rhnnrA

Rnyc

fnr

reasons perhaps attributable to hormonal

differences, are up to five times more

vulnerable than girls.

Second, today’s mobile society has all

but abolished the extended family. Par

ents can no longer count on grandparents,

Robert It. McElroy—Newsweek

Six-year-old girl with doll: Nightmares, compulsions and loneliness

aunts and uncles to act as authority

figures in the raising of their children.

“I’m personally convinced that no two

parents can rear a child entirely alone,”

says Dr. Sally Provence of Yale’s Child

Study Center. “Yet young parents have

fewer supports for parenting than ever

before—it’s either drag the kids along or

get a sitter.” With the increasing num

ber of young women carving out careers

for themselves, some experts see a threat

even to the integrity of the nuclear

family. “I’d much rather see people nothave children at all than leave infants

in a day-care center,” says Dr. Lee Salk,

chief child psychologist at New York

Hospital-Cornell Medical Center and

author of the best seller “What EvenChild Would Like His Parents to Know.”

Third, in today’s push-button society

children tend to learn about the world

around them vicariously by television.

“Many of our children and young people

have been everywhere by eye and ear,”

notes a recent report of the Joint Com

mission on Mental Health of Children,

“and almost nowhere in the realities of

their self-initiated experiences.” And

much of what the children see is the

vivid depiction of war, violence and so- cial upheaval; aggression has become

.one of the most pervasive childhood ex

periences of all, says Dr. Ebbe Ebbesen

of the University of California at San Die- ".

go. “Children learn abnormal behavior

from observing other people,” the Cali

fornia psychologist contends. “The more

aggression a child is exposed to, the morA

A schizophrenic child can

produce only squiggles when

requested to draw a person

Big teeth in drawing

by depressed boy sug

gest hostility of parents

April 8, 1974

Withdrawn child’s poor percep

tion of people is shown in drawing

of figure without ears and arms

53

SCIENCE

Mission to Mercury

For the moment the U.S. manned

space program is at a standstill, and after

next year’s planned link-up between U.S.

and Soviet spacecraft, no American as

tronaut is scheduled to fly until 1979

when the space shuttle is due to make

its maiden flight. But the pace of plane

tary exploration by unmanned probes,

belli U.S. and Soviet, is quickening spec

tacularly. In recent months, instrumented

spacecraft have zeroed in on Venus, Mars

and Jupiter to provide astronomers with

a wealth of significant new data on those

planets. And last week in Pasadena, sci

entists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

witnessed perhaps the most dramatic

event yet in planetary exploration—the

transmission by Mariner 10 of the firstever close-up pictures of Mercury.

For the astronomers at Pasadena, the

pictures were priceless. Mercury is the

closest planet to the sun (the distance

varies from 29 million to 43 million

miles), and is thus all but unobseiwable

through even the largest earth-based

telescopes. Because of its proximity to

the sun, the ancients saw Mercury as a

kind of solar equerry—and hence named

it after the messenger of the gods. The

planet is just half again as large as the

moon, but its density is similar to the

earth’s, suggesting that it contains large

amounts of iron. Mercury takes 88 days to

speed around the sun in a markedly el

liptical orbit. Until 1965, astronomers

believed that it continually offered the

same face to the sun as the moon does

to the earth. But then radar studies

proved that the planet rotates on its

axis once every 58': days.

The combination of Mercury’s slow ro

tation and its elliptical orbit produces an

effect unique in the solar system. As the

planet approaches its closest point to

the sun, an observer on Mercury’s surface

would see the sun apparently stop in the

sky and then travel backward for a short

while, before resuming its movement

across the sky in the normal direction.

Pictures: Mariner 10’s first photo

graphs, taken from a distance of 3.5 mil

lion miles, showed Mercury to be covered

with white spots. As the craft moved

closer, the spots became craters, resem

bling those on the moon and Mars. So

clear were the pictures that the scien

tists at Pasadena did not need the normal

computer enhancement to spot craters

within other craters, or to see sinuous,

rille-like features winding between the

craters.

The pockmarked appearance of Mer

cury’s surface had been largely expect

ed, but scientists were amazed when

Mariner’s instruments detected evidence

of a small magnetic field and a wispy

atmosphere around the planet. Astron

omers had thought that Mercury’s slow

rotation would preclude a magnetic field.

They had also believed that the solar

Newsweek. April 8, 1974

wind of particles streaming outward from cember, Pioneer 10 returned a great deal

the sun would strip away any molecules ^pre data than expected. In particular,

in the atmosphere. The''magnetic field the craft discovered that the Jovian up

that Mariner found is onlyXl per cent as per atmosphere consists of at least 70 per

strong as earth’s field, but 'greater than cent hydrogen and that it contains a

those of Venus and the morin; the thin “temperature inversion” (in which the

atmosphere is composed predominantly warmer air lies above the colder). This

of neon, argon, helium and hydrogen. combination of circumstances, says Dr.

Scientists postulate that the gases arose John Wolfe of NASA’s Ames Research

in some way from inside Mercury, 'either Center, means that the space agency

from volcanic activity or some process should be able to send a space probe

yet to be identified.

\

right into Jupiter’s atmosphere—a task

Spectacular as they were, Mariner 10’s previously considered impossible.

views of Mercury were just the latest in,

From the astronomers’ point of view,

a series of recent planetary unveilings. '■ the planetary probes are giving a com-’’

Among the highlights:

\pletely new dimension to the oldest of

■ VENUS. Passing within 3,500 miles of

all sciences. “All of the other sciences

Venus en route to Mercury, Mariner 10 lend themselves to experimentation,” ex

provided scientists with a first clear plains Carl Sagan of Cornell University.

glimpse of Venusian weather patterns. “But this has never been true of astrono

The unexpected findings included ultra my. The astronomer has always had to sit

violet views of a shell of carbon monoxide passively and watch the sky. Now, the

surrounding the planet, a huge (4,500 advent of space probes makes astronomy

miles by 1,250 miles) oval blemish in an experimental science, and this is one

the atmosphere roughly in line with the of the biggest breakthroughs in the his

sun that was dubbed the Venusian Eye, tory of the field.”

and a jet stream that carries the cloud

Interestingly enough, the information

cover in a westerly direction at up to produced by space probes has applica

hundreds of miles an hour.

tions close to home. Meteorologists think

■ MARS. Last month, a convoy of four

that knowledge of planetary atmospheres

Soviet spacecraft arrived in the vicinity will permit them- to build models of

of the red planet, but two efforts to soft- global weather systems that will allow

land an instrument package on its surface better understanding of the earth’s

failed; one missed Mars completely, weather. On Venus, for example, atmos

while the other ceased transmitting on pheric circulation is not affected by

its way down. Even so, the probes did planetary rotation, and on Mars there is

hint that the Martian atmosphere con no evaporation and condensation of

tains several times more water vapor water. “The planets,” says Kenneth

than previously believed. U.S. space ex Franklin of New York’s Hayden Plane

perts think that the Russians will try an tarium, “give us a chance to study some

other soft landing next year.

of the important factors in weather by

■ JUPITER. Negotiating the intense ra

isolating those factors—something that is

diation belts of the giant planet last De impossible to do on earth.”

51 ■

MEDICINE

E-iMni «E1U.

WWteiR sw.)®&. raw3a;.E«ae

Troubled Chi Idren: The Quest for Help

the number of emotionally troubled chil

dren is appallingly high.

■the most conservative estimate, at

he control of the often deadly diseases

of childhood is the proudest achieve-. least 1.4 million children under the age

ment of medical progress in this centuiyj of 18 have emotional problems of suffi

Thanks to vaccines and antibiotics, the cient severity to warrant urgent atten

average American child no longer must tion. As many as 10 million more require

run a gauntlet of physical threats such psychiatric help of some kind if they are

as the crippling effects of polio, the heart ever to achieve the potential that medi

damage of rheumatic fever or diphthe cal progress on other fronts has made

ria’s death by slow strangulation. Thanks possible. “If we used really careful

to better nutrition, today's children grow screening devices,” says Dr. Joseph D.

inches taller and pounds heavier than Noshpitz, president of the American

their forebears did. In short, the Ameri Academy of Child Psychiatry, “we would

can youngster has never had better pros- probably double and maybe treble the

_ poets for a long and healthy life.

official statistics.”

Jut for all that modem medicine has

The hard core of these children are

io- to protect and nourish the child’s those who arc autistic or schizophrenic.

body, surprisingly little has been done They are helplessly withdrawn from re

to assure him of an equally healthy mind?) ality and exist in an inner world that is

Despite all the talk about America’s seldom penetrated by outsiders. More

child-centered society and all the Vest than 1 million other children are hyper

sellers purporting to tell parents how to kinetic. They turn both living rooms

raise happy, well-adjusted youngsters, and classrooms into shambles by their

BY MATT CLARK

T

e

frenetic and uncontrollable physical ac

tivity. Millions more troubled children

are plagued by neurotic symptoms. They

are haunted by monster-ridden night

mares, frightened of going to school, held

in the grip of strange compulsive rituals

or lost in the loneliness p£ Repression.

Harder to pinpoint but just as‘troubledare those who simply don’t function in

society. They fail in school, they run

away, they fight, they steal. Eventually,

they fill reform schools and prisons.

f_JJntil recently, childhood emotional

disorders have been tragically neglect

ed as a national health problem of dra

matic proportions'?) Because of his bizarre

and often repellent behavior, the emo

tionally disturbed youngster has nevermade an appealing poster child for moth

ers’ marches and annual fund-raising

drives.\ While most of the nation’s 7.6 mil

lion physically handicapped children re

ceive educational and medical services

through a variety of public and private

channels, fewer than 1 million of the

emotionally handicapped are receiving

the help they need. All too often, the

disturbed child has been expelled from

public school as unteachable, or shunted

into special cl assessor retarded children

with brain damage^* We are in the Year

One in care and treatment of these chil

dren,” declares Josh Greenfeld, a 46year-old writer whose 1972 book, “A

Child Called Noah,” vividly described

his own agonizing search to find help for

his autistic son. “We are going to have

to shock ourselves into the fact that we

are killing these children as well as de

stroying the lives of the families the kids

are part of.”

But within the past few years, parents

A test of patience: Autistic child with mother in North Carolina ..

52

like the Greenfelds have made some im

portant gains in winning better care for

their troubled children through the legis-:

lators and the courts. In one of the most

far-reaching decisions of all, a District of

Columbia Federal judge ruled in 1972

that all handicapped youngsters—includ

ing the emotionally disturbed—are en

titled to public education under the

Fourteenth Amendment. Thanks to the

relentless lobbying of the National Soci

ety for Autistic Children in Albany, N.Y.

—composed largely of parents—more than

30 states have passed laws providing

special education for autistics in the last

four years.

One reason for the increasing rec

ognition of the needs of the troubled

child is the strong evidence that his

ranks are growing. The number of chil

dren receiving treatment for emotional

problems in institutions and outpatient

facilities has risen nearly 60 per cent in

the last seven years—from 486,000 to

Newsweek

Position: 3092 (2 views)