SDA-RF-CH-1B.12.pdf

Media

- extracted text

-

' •'

• ' ■

SDA-RF-CH-1B.12

•

-------aj-e

explains how tins figure was reached. Our for- rice work in Banidhaman

district Almost all seasonal migrants travelWO*1.

observations and estimates suggest that poor, though most cultivate on their own bands or gangs. Gangs in the streams

several hundreds of thousands of people account back home and the livelihoods of originating in Dumka district, Puruliya/

also migrate in the three other main sea many involve multiple activities, includ Bankura districts and Purbi Singhbhum

sons for employment in rice work.

ing, in different combinations, petty trade, district8 were usually mixed sex and often

Our ethnographic research, including life processing, gathering and study. Migrants included children and infants. In contrast,

history interviews, in the study localities7 tend to be in scheduled social groups, almost all gangs in the Murshidabadsuggests that seasonal migration has in- whether castes or tribes, or according to Barddhaman stream were entirely male

creased into the destination locality and religion,

with no accompanying children. Some

out of three of the source area localities

Table 2: Characteristics of the Main Migration Seasons

over the last 30 years. Although in the ____

fourth source area locality, in Purbi Season

Conditions

Months

Singhbhum district, seasonal migration had Aman Transplanting July-August

Heavy rain - standing in water to work; migrants avoid bringing

declined, this was not necessarily typical

children; snakes; clashes with own transplanting at source

November-January

of the Purbi Singhbhum - east Medinipur Aman Harvest

Cold weather - risk of injury through threshing. Coincides with

harvest work at source.

stream as a whole. Overall, seasonal

February

Standing in water to work. In most source areas does not

Boro Transplanting

migration has continued to grow in the

coincide with own work at source.

1980s and 1990s. However, interviews Boro Harvest

Extremely hot - hard manual work during day In open fields in

April-May

temperatures of 40c and above. Risk of injury through threshing.

with employers in five destination locali

Snakes. Work very intensive because of employers’ need to

ties suggest that the source areas and

avoid rain. Employers tense and employ more workers for

recruitment mechanisms used by employ

shorter period than in aman harvest. Often leads to fever or

ers have changed over time. This change

diarrhoea as well as exhaustion among labourers. Does not

coincide with own work at source but remittances may be useful

also reflects supply factors with, for ex

for beginning of own monsoon transplanting.

ample, the development of intensive irri

gated agriculture in west Medinipur [see

Rogaly et al 2000J.

Table 3: Characteristics of the Study Localities and Sub-Regions

■

Migrant Workers and Their

Employers?

I.

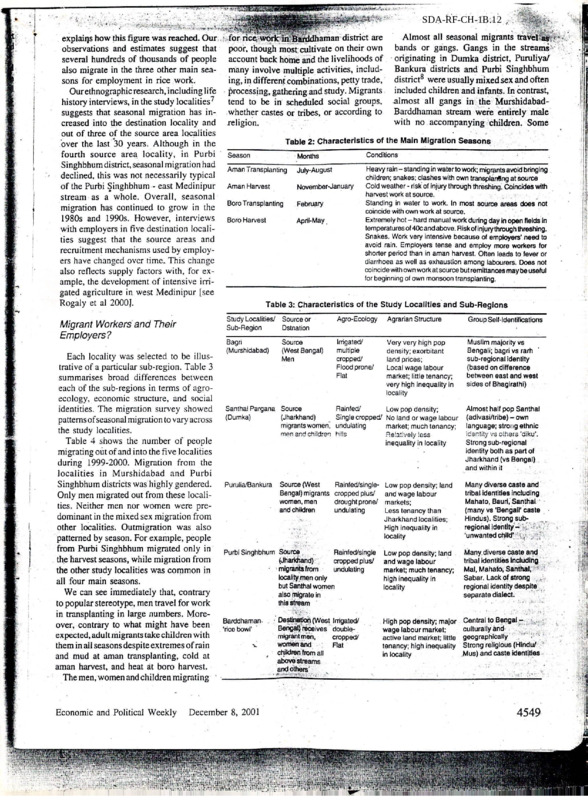

Each locality was selected to be illus

trative of a particular sub-region. Table 3

summarises broad differences between

each of the sub-regions in terms of agro

ecology, economic structure, and social

identities. The migration survey showed

patterns of seasonal migration to vary across

the study localities.

Table 4 shows the number of people

migrating out of and into the five localities

during 1999-2000. Migration from the

localities in Murshidabad and Purbi

Singhbhum districts was highly gendered.

Only men migrated out from these locali

ties. Neither men nor women were pre

dominant in the mixed sex migration from

other localities. Outmigration was also

patterned by season. For example, people

from Purbi Singhbhum migrated only in

the harvest seasons, while migration from

the other study localities was common in

all four main seasons.

We can see immediately that, contrary

to popular stereotype, men travel for work

in transplanting in large numbers. More

over, contrary to what might have been

expected, adult migrants take children with

them in all seasons despite extremes of rain

and mud at aman transplanting, cold at

aman harvest, and heat at boro harvest.

The men, women and children migrating

Study Localities/

Sub-Region

Source or

Dstnation

Agro-Ecology

Agrarian Structure

Group Self-Identifications

Bagri

(Murshidabad)

Source

(West Bengal)

Men

Irrigated/

multiple

cropped/

Flood prone/

Flat

Very very high pop

density; exorbitant

land prices;

Local wage labour

market; little tenancy;

very high inequality in

locality

Muslim majority vs

Bengali; bagri vs rarh

sub-regional identity

(based on difference

between east and west

sides of Bhagirathi)

t

!

■

i

Ilf

Santhal Pargana Source

Rainfed/

Almost half pop Santhal

Low pop density;

(Dumka)

(Jharkhand)

Single cropped/ No land or wage labour (adivasi/tribe) - own

migrants women, undulating

language; strong ethnic

market; much tenancy;

men and children hills

identity vs others ‘diku’.

Relatively less

Strong sub-regional

inequality in locality

identity both as part of

Jharkhand (vs Bengal)

and within it

Purulia/Bankura

Source (West

Bengal) migrants

women, men

and children

Low pop density; land

and wage labour

markets;

Less tenancy than

Jharkhand localities;

High inequality in

locality

Many diverse caste and

tribal identities Including

Mahato, Baud, Santhal

(many vs ‘Bengali' caste

Hindus). Strong sub

regional identity- .

‘unwanted child’ ky

Purbi Singhbhum Source

Rainfed/single

(Jharkhand)

cropped plus/

migrants from

undulating

locality men only

but Santhal women

also migrate in

this stream

Low pop density; land

and wage labour

market; much tenancy;

high inequality in

locality

Many, diverse caste and

tribal identities Including

Mai, Mahato, Santhal,

Sabar. Lack of strong .

regional identity despite

separate dialect.

Barddhaman'rice bowl’

High pop density; major

wage labour market;

active land market; little

tenancy: high inequality

in locality

Central to Bengal culturally and

geographically

Strong religious (Hindu/

Mus) and caste identities

Rainfed/singlecropped plus/

drought prone/

undulating

Destination (West Irrigated/

Bengal) receives double

migrant meh,

cropped/

women and

Rat

children from all

above streams

. andothers . ~

:r,U

I

i

I

I

' I

I

■1

Economic and Political Weekly

December 8, 2001

4549

1

• •*-

J1 :

1 11 .

■

AV,

•-

?

I

It'

‘•■1.

gangs leaving the source area study locali

ties were made up of people of different

‘jati’ (as seen in relation to others in the

source locality) but to differing degrees

depending on the source locality. All

Muslim and all-Santhal groups were com

monly formed in the Murshidabad and

Dumka study localities respectively, though

there were exceptions.

Employers may be tenant farmers or

owner-occupiers. Most of the sampled

employers in the studied destination area

locality were own6r-occupiers. Although

all were Hindu, they were far from homog

enous in terms of wealth, caste, education

and occupational mix. The study locality

included two scheduled castes, Dorns and

Bagdis, high caste Mahanto Bamun, and

the peasant caste Aguris.9 Employers of

migrants included a local Bagdi labourer

who cultivated a small area of land (1

bigha, or 0.3 acres, HH 55) and could

borrow migrant workers recruited by his

own regular employer. At the other end

were employers, all Aguris, whose sons

had studied to degree level, who received

regular salaried income, and who con

trolled the trade in rice and fertiliser as well

as relatively large areas of land (36 bighas,

or 12 acres, HH 5).

In Barddhaman District as a whole, there

is also a sizeable group of Muslim culti

vators who employ migrant labourers.10

Table 7 gives the breakdown by religion

of employers.hiring gangs of workers from

the study localities in 1999 2000. There

was no one-to-one correspondence between

employer’s religion and the social compo

sition of the migrant gang they hired.

However, a larger proportion of gangs

from the predominantly Muslim

Murshidabad (Bagri) locality found work

with Muslim employers. Our findings

suggest this pattern also holds for the

Murshidabad-Barddhaman stream.11

Gangs of Migrants and Their

Recruitment

In studies of contemporary seasonal

migration in other regions of India, middle

men or brokers have been found to be

important in the fixing of wages, working

conditions and living accommodation.12

In the study region there is no cadre of

brokers involved in the recruitment of

migrant rice workers. In most of the stud

ied source localities, individual men and

women act as gang leaders or ‘sardars’.

The rote of a ‘sardar’ varies, however,

from being a person with initiative and

4550

Map of the Study Region

A

ti

l^Deihi

'

r

■-'i

f

la

BAY OP

BENGAL

BANGLADESH

□UMKA

• (\

4-'

Rampurhal •

BIRBHUM

r

yl ^jiyaqHni

Zmurshidabad

?

|

/

'l

JHARKHAND

NADIA

PUHULIYA

•Ranclu

BANKUHA

(

c

\

( 7

(

)

BANKURA

HUGLI

r>

I Jainshenpur A

\

[/

I

WEST BENGAL

\

i

PARGANA -

r—•

Z

PURBI

^INGHBHUM

A. iK0LKA,A

J f

haor

\

fl <

24 parganas

MEDINIPIJR

MAVURBHAN.I

I

ORISSA

/

I

BALESHWAR

(S)

a

BAY OF BENGAL

studied migration streams

0

km

mo I

Barddhaman district destination areas

confidence who builds up a group and regular sardars. Groups form among rela

negotiates with employers.at labour mar tives, friends and acquaintances, often

ket places, to an established

c«-------- contact and involving men from other nearby vil- >

13 Ganes

lages.13

Gangs are more like bands with

semi-permanent recruit of" a destination inopc

a

median

of five or six members (depend

who

travels

employer

regularly

area ( t ,

betwee their own village and the* em ing on the season), much smaller than the

ployer, bringing migrants according to gangs which travel out from the other

prior specifications. This variation in roles study , localities (Table 8). The larger .

exists within as well as between locali*-.

locali- , number of gangs from the Murshidabad

locality is

is due

to the

the common

ties, for example in the Puruliya study study

study locality

due to

common pracprac- ‘*

locality

tice of migrating to work for two or more

W

Exceptionally,

Exceptionally, in Jalpara, the employers in the same season [Rogaly and H

Murshidabad study locality, thete are no Rafique 2001].

»Economic and Political Weekly

December 8, 2001

1

¥

!

* •

ii .v s . ...

redistribution of land held over the ceil

From our observation’s at Katwa railway 24 Parganas and Murshidabad, and paid ing, and panchayati raj.1-8 .

.

station, an important labour market place, at a piece rate.

This was a period of consolidation for

In sum, seasonal migration is of critical

a smaller gang size appears to be typical

the

smallholdercultivators, many of whom

of the Bagri (Murshidabad)-Barddhaman importance to the material livelihoods of were actively involved in the political

stream as a whole. Table 8 also indicates many hundreds of thousands of people in parties in the Left Front coalition, particu

a relatively large median gang size (rang the study region. It involves men, women larly in the Communist Party of India

ing from 14 to 50 depending on the season) and children, mainly scheduled castes, (Marxist). The CPI(M)’s strategy became

from the Puruliya locality, where two scheduled tribes and Muslims. Employers, more focused on electoral success, through

regular institutionalised sardars worked Hindu and Muslim, are smallholders with seeking to maintain support across classes

for the same particular large-scale employ different degrees of wealth and varied of smallholders as well as agricultural wage

labour requirements. While there is some

ers each season.14

workers, and keeping the peace in the

Employers in the destination study lo cooperation in recruitment, most of this is countryside [Webster 1990,1999; Rogaly.

cality hired gangs of a wide range of sizes part of patron-client relationships between 1998b]. Smallholders with profits from

(four to sixty) and for between one and relatively large and relatively small-scale agriculture began to invest in groundwater

thirty days (Table 9). Gangs of labourers employers. Most recruitment is organised irrigation, which was more attractive in the

were recruited directly by employers or by employers acting as individuals rather less conflictive rural environment, and

through employers’ agents ( gomostha ). than in collusive groups. In Section II, we seemed likely to produce further profits,

Recruitment could be from a labour mar move on to consider the causes and con given the efforts made by the regime to

ketplace or by travelling in person to known sequences of seasonal migration for rice make access to credit and other agricul

villages in a source area. Sometimes work.

tural inputs much easier and their supply

employment arrangements were initiated

more timely. Rapid expansion of the new

III

by labour gangs or leaders of gangs (sardars) ,

boro crop and adoption of high yielding

Causes and Consequences

coming to seek work unsolicited. Evidence

varieties and associated cultivation tech

of Seasonal Migration

gathered through travelling with migrant

nologies began in the early 1980s and has

workers, observations of labour market

continued throughout the last two de

places and interviews in source areas Growing Demand for Migrant

cades.19

showed that in Barddhaman district as a Workers

One outcome of these changes was that

whole, it was common practice for em

more

manual workers were required in

The history of settlement and the begin

ployers to seek one season’s gang to commit

Barddhaman district. Although irrigation,

nings

rice

cultivation

in

the

area

now

of

to work in the following season.

Barddhaman district go back ploughing and threshing were increasingly

In the destination study locality at least known as 1----------mechanised, the transplanting and harvest

one-third of employers were supplied with over millenia [Eaton 1994]. Populations ing of rice continued to be carried out by

in

the

study

region

as

a

whole,

which

migrants by other employers. For three

hand- Ideologically, manual work was seen

seasons of the year, cultivators of smaller includes parts of present-day Jharkhand by many owners of land as. something to

amounts of land were able to borrow and West Bengal states (see Map), have be avoided by both men and women."®

migrant workers, who had been recruited never been static, and seasonal migration ; ' ‘ ■' j employers’ aspirations for

locality

and were being accommodated in the cow for work in the rice fields of south-central Study

Bengal has a history of at least 100 years.16 thei/ children and even for themselves

sheds and other outbuildings of largerTaken together, our evidence17 suggests involved spending increasing amounts of

scale cultivators. Because of a correspon

a

rapid

increase in the number of manual time out of agriculture, in urban white

dence between landholding size and jati,

collar occupations. This ‘babu’ approach

there was a jati-pattem to cross-recruit workers migrating seasonally for rice work to agriculture came to be more affordable

ment. In general. Mohanto Bamuns and in the last two decades to have taken place as profits were made from rice production

Bagdi employers required less migrants in the context of a-series of political, and wealth was accumulated. It was scoffed

than Aguris and cross-recruitment was by economic and cultural changes in the at by those other landowners who contin

Mohanto Bamuns or Bagdis from Aguri destination area.

Prior to the . coming on stream of the ued to see themselves as ‘chasis’, peasant

employers. Money did not change hands

Damodar

Valley Corporation canal system cultivators, for whom doing their own

between employers for this, though it

cultivation work alongside other family

formed a part of ongoing patron-client in the 1960s, there was little assured members and hired labourers was part of

relations. The smaller-scale employer paid irrigation in Barddhaman district. The their self-identity. However, even this group

the migrants’ wages for their period of coming of canal irrigation and the slow required manual workers in the peak sea

expansion of the entirely irrigated boro

hiring.

sons. At the same time some former local

In the season for transplanting aman paddy crop from the early 1970s took labourers aspired to withdrawal from this

rice, however, there was cooperation in place at a time of violent conflict in the kind of employment.21 Another reason

recruitment between relatively large-scale countryside, including a period of land why demand for migrant workers increased

employers, who would club together to seizures during the 1967-69 period and was the reduction in hours of work per day

cover the costs.15 Whereas for the other heavy repression in the eight years fol for local labourers. The Krishak Sabha, a

three seasons most gangs hired were from lowing. The Lert Front government, CPI(M) mass organisation made up of

the Puruliya/Bankura stream to the west which came to power in 1977, imple smallholder cultivators and wage workers,

and were paid at a time rate, for the aman mented agrarian reforms energetically in supported this direction of change in

transplanting, most of the gangs were hired its early years, in particular the registra Barddhaman.

• <

from the east, from the districts of north tion of share-croppers, the continuing

".s’

I

5

9

-

•

j

- - -J

/'••• - •

Economic and Political Weekly

>-

December 8, 2001

4551

i-l

f

i1

4

jg

I

•'ll

■7-

i L

Role of the Krishak Sabha

Other changes that the Krishak Sabha

has presided over during this period (and

which have been associated with increased

demand for labour in agriculture) have

included the closing of the gap between

male and female wages and ensuring steady

increases in the cash portion of the pre

scribed wage rate, so that real wages did

not decline. Not surprisingly, given its

cross-class composition, the Krishak Sabha

did not represent agricultural workers as

a class-for-itself.22 Indeed agricultural

labourers were not allowed to form a

separate union of their own. The changes

in wages and working conditions reflected

a carefully managed balance of power, in

which smallholder-farmerswho employed

labour were dominant. The positive

developments which were felt by wage

workers were necessary to the overall

strategy of enabling smallholders to pur

sue profit in a non-conflictive countryside

and of keeping cross-class support for the

CPI(M) in elections.

The Krishak Sabha agreed to continue

allowing migrants from outside

Barddhaman district to be employed there.

This reflected employers’ interests in two

ways. It greatly relieved their seasonal

labour shortages, and it also exerted indi

rect pressure on local labourers to comply

with working conditions or be replaced.23

The Krishak- Sabha decided in the early

1980s to compensate local labourers in

two ways: migrants would be allowed to

work only in peak seasons, and, most

importantly, they could not be employed

at lower levels of earnings per day than

local labourers.24

Accumulation of Wealth and

Growing Inequality

i.!,:

Enabled by the Krishak Sabha to bring

in migrant workers to cover the periods of

intense labour shortages, many larger-scale

smallholders accumulated further wealth.

Those in the strongest economic positions

had diversified beyond agriculture into

trade (in fertilisers and rice), processing

(of rice), salaried employment and party

politics. In Moraipur, the destination area

study locality, during the 1990s, better-off

agricultural employers were able to

build large ‘dalans’ (brick built houses)

and to purchase consumer durables,,

including dining tables and chairs,

televisions, satellite dishes and cars.25

The gini coefficient of inequality in the

distribution of assets in the study year side the vertical unequal mutuality be

was 0.58. In the district as a whole tween employers manifest in cross-recruit

inequality among smallholders and ment in the study locality, as well as the

between smallholders and labourers has cooperation over recruitment of piece rate

visibly increased26 during the 1980s and workers at aman transplanting. As men

tioned, employers here did their own re

1990s.

’ As we have seen, the Krishak Sabha cruitment (or used their own permanent

oversaw this process of accumulation in labourers) in migrants’ villages of origin

Barddhaman district, through making or at labour marketplaces. There was no

deals between classes with potentially cadre vof middlemen in the market for

conflicting interests. Accumulation has migrant rice workers.

Recruitment of labour-was not the only

increased the demand for migrant workers

(a cause of migration), while also being factor which made for the insecurity of

built on the back of migrant workers destination area employers. Profits de(a consequence of migration). The success pended on the costs of other inputs, includof the CPI(M)’s strategy can be seen in

Table 6: Social Composition of Migrant

the continued cross-class support it won

Gangs from Source Area Study

in the 2001 West Bengal state assembly

Localities

elections.

Single Jati Mixed Jati

Source Locality

Competition and Insecurity among

Employers

Although employers argued common

class positions within the Krishak Sabha,

we have described class differences be

tween employers [Rogaly et al 2000] and

found further evidence of intense rivalry

and competition among agricultural employers of the same class. This ran along-

Gang

Gang

61

39

6

1

8

7,

6

6

Jalpara, Murshidabad

Alopahari, Dumka

Bajnagarh, Puruliya

Upartola, Purbi Singhbhum

Notes: 1 Jati is used here to refer to the social group

(based on caste, religion, ethnicity), which

an individual belongs to in their home

locality as seen by others there.

2 In Jalpara, the social composition of two

gangs was not recorded.

Source: Migration survey.

Table 4: Number of Seasonal Migrants Hiring Out and Number Hired in for

Rice Work by Season (1999-2000)

Study Locality

Aman Transplanting

Aman Harvest

Boro Transplanting

Boro Harvest

Jalpara, Murshidabad

Alopahari, Dumka

54 men

130 mixed sex of

which 18 children

119 men

67 men

61 men, 55 women, 71 men, 78 women.

20 children

29 children

Bajnagarh, Puruliya

127 mixed sex of

which 26 children

35 men, 28 women, 16 men, 25 women,

and 7 children

and 11 children

0

Upartola, Purbi

Singhbhum

Moraipur, Barddhaman ?

18 men

0

143 men

49 men. 72

women and

27 children

21 men, 22

women, and

5 children

53 men

535 inmigrants +

children

500 inmigrants +

children

639 in-migrants +

childrr

I

Notes: 1 The number of women and men in-the mixed groups from Dumka district were not counted

separately in the aman transplanting season, nor in the destination area study locality.

2 The numbers of migrants for aman transplanting work from Bajnagarh, Puruliya, is inflated

£

because it is based on total gang size, rather than gang members from the study locality. .

Source: Migration survey.

1

Table 5: Sex Composition of Migrant Gangs and Number Travelling with Children or

Infants by Source Locality

Source Locality

Jalpara, Murshidabad

Alopahari, Dumka

Bajnagarh, Puruliya

Upartola, Purbi Singhbhum

Men-only

Gangs

Women-Only

Gangs

Mixed Sex

Gangs

61

2

1

7

0

0

0

0

0

28

,14

0

Gangs with

Gangs without

Children/lnfants Children/lnfants

~061

'

23 •

9

0

7

6

7

Notes: 1 Data on the sex and age composition of gangs was collected in three seasons only. Hence thejE

total number of gangs is less than might have been expected from previous tables. ®

2 Gangs travelling with children all included both men and women.

Source: Migration survey.

'

December 8, 2001 j

Economic and Political Weekly

4552

■...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

-

............................................................................................................

I

-/.Xv'Vv i.

< 1I 1I

■' ft

■-I

W

■

■

ing fertiliser as well'1 as diesel and electricelectric they were likely to get consecutive days

ityforgroundwaterimgation.andtheprice

for groundwater irrigation, and the price of work at the agreed rate. This was not

ity

theircropcouldfetchinthemarket.During possible at home.

■ t

Migrant workers also knew that they

the fieldwork year, it became clear that

___________

having would almost always be paid for the work

central government policies were

effect on the .prosperity of agricultural they did because non-payment would be

ant---smallholder producers. Not only were against the interests of the Krishak Sabha

subsidies on inputs being reduced, the as it was likely to lower the reputation of

prices which mills and their agents were the Krishak Sabha itself in terms of its

prepared to pay for their crops had dras- capacity/ to manage the countryside. It

tically declined. The classic method of would

v : ,J also work against the reputation of

making money on rice for relatively well- the locality. Several incidents in which the

to-do cultivators was to store it and sell ‘party’ (whether in the form of elected

it pre-harvest. Mills were now increasingly representatives in the panchayats, party

cadres or

or Krishak

Krishak Sabha

Sabha members)

members) was

was

supplied with unhusked rice by producers cadres

in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The price of called on to enforce proper payment were

rice was further reduced by purchases from recalled by migrants interviewed in the

Bangladesh, Thailand and elsewhere, source localities.31 These incidents were

enabled by the liberalisation of imports.27 especially striking for migrants from

It was admitted by Madan Ghosh, the Jharkhand state,32 to whom organised

secretary of the CPRM) in Barddhaman institutional wage protection, even at the

district,28 that it was conceivable that wages local level was unknown.

might have to fall and the rise eventually

agreed in November 2000 was less than Labourers’ Room for Manoeuvre in

had been anticipated, also due to flood.29 Negotiations

Earning Potential as a Cause of

Increasing Seasonal Migration

For people in the source areas surrounding Barddhaman district, the increases in

wage rates and i n the number of day s ’ work

available at the destination each season

motives for

have been very important

i ,

migration. The length of the migration

seasons was approximately 20 days (see

Appendix). During the study year the wage

the Krishak

--------- Sabha

------- in

prescribed by t.._

Barddhaman district for all agricultural

labourers was T1 rupees per day and 2 kg

was equivalent to 4-4.5 kg of

rice.30 This

'__ ____

hulled rice, which in real terms showed no

changefrom 1991-92 [Rogaly 1996:147].

Wages varied across the source area study

localities and seasonal fluctuations were

also more pronounced there. A peak sea

son wage with a total value of Rs 20 per

day (equivalent to approximately 2 kg of

hulled rice) was not untypical.

There were upward variations from the

prescribed wage in what was actually

received by migrant workers; and most

migrants in the Murshidabad-Barddhaman

stream were paid their kind portion in

cooked food rather than rice. As we have

seen in.the previous section some migrants

were paid at a piece rate, which usually

meant higher daily earnings than time rate

arrangements. Most importantly, in the

four main seasons, workers knew from

previous experience or from others that

I

■ s

•'wI

I

!'lI

JlH

"’ . W

I■

*

ft

ft

I

-s

1

Economic and Political Weekly

-----

The main proximate cause of seasonal

migration from the source areas for those

who migrated was therefore that they

expected to gain a lump sum of cash to

take home which would nor be available

to them in the source area and to eat for

the period of work. However, the specific

dynamics of seasonal migration in the study

region meant that labourers regularly found

room for manoeuvre in negotiations.

Here lies another part of the explanation

for the growth in the numbers of seasonal

migrants. Not all migrants in the study

regioni were compelled by economic circumstances to migrate each time they went.

Lack of collusion by employers contributed to migration even by people who

could get by without it. Migrants knew that

in the season they were very likely to find

work and to get paid in Barddhaman.

Negotiation was possible over wage rates,

number of days work, distance of fields

from —

accommodation, meal quality and

f.—timing.,33 Of course, once a gang of

migrants arrived at the work and living

place for the season, the employer might

renege on parts of this agreement. Employ

ers’ relatively higher material security

meant their capacity to withhold work from

a particular group gave them power in the

market unmatched by migrants’ capacity

to exit. However, this did not leave mi

grants without power altogether. Some

tested out whether the employer seemed

to be true to his word and a few gangs

December 8, 2001

••

• • •

returned to the labour marketplace surrep

titiously (if they found the reality did not

match the rhetoric and they could afford

to), leaving an employer who had invested

time and money in recruitment and more

importantly in their rice crop, with major

problems.

Divergent Trajectories

The underlying causes and the conse

quences of seasonal migration varied across

the four migration streams, as illustrated

through analysis of data from the source

area study localities. These underlying

causes reflected specific agro-ecological

conditions, economic structures and wider

social relations, as well as associated

contrasts in the potential for change in

each of these.

Murshidabad-Bagri Locality: Itinerant

petty trade has long been an important

occupation for poor residents of the

Murshidabad locality, Jalpara, but agricul

ture remains central. The sub-region has

seen a dramatic agricultural revolution in

the 1990s on the scale of that which took

place in Barddhaman district. A high water

table meant that irrigation water was readily

available beneath the surface. Those fami

lies who were able to invest early in groundTable 7: Religion of Employers of Gangs

of Migrant Workers from the Source

Area Study Localities

(Number of Gangs Each Season)

Source Locality and Season

Alopahari, Dumka

Aman harvest 1999

Boro transplanting 2000

Boro harvest 2000

Jalpara, Murshidabad

Aman harvest 1999

Boro transplanting 2000

Boro harvest 2000

Bajnagarh, Puruliya

Aman harvest 1999

Boro transplanting 2000

Boro harvest 2000

Upartola, Purbi Singhbhum

Aman harvest 1999

Boro transplanting 2000

Boro harvest 2000

Hindu

Muslim

8

7

6

2

2

3

4

4

17

18

6

11

5

4

3

o

2

o

4

0

1

1

Notes: 1 This information was not recorded in the

aman transplanting season. Employer’s

religion was also not recorded in the case

of a few gangs in the three seasons

reported here.

2 In the boro harvest there is a shift for the

Murshidabad gangs from predominantly

hiring out to Muslims to predominantly

hiring but to Hindus. This is associated

with migration to Nadia district in the boro

harvest. Six gangs reported migrating to

Nadia at the boro harvest and all but one

gang worked for Hindu employers.

Source: Migration survey.

4553

1

'ifit

livelihoods. Rather than inequality (gmi

was 0.54 in the study year) accelerating

to exclude poorer people from being able

able to dictate terms to crop cultivators to investThiand (as in the Murshidabad

within the command area. Land prices locality), migrants have invested their

have rocketed

with the

new productivity

productivity

iCKeieu wiu.

M.w ..w..

emittances into renting and cultivating

r available

land

per

has

landastenanls. Migration for some has led C°Seasona:i migration in this locality was

and as

*.

r-- cap.ta

creased further, caused by the very rapid the way out of being compelled to migrate.

clearly associated with a process of pa ia

' 1 for rice work is on the decline, delinking from dependence on the patron

Mi,..although there has been a small increase age of rajas; Wages earned through migra

Land prices in the study locality were in migration to work in brick kilns.

tion enabled conspicuous consumption

Rs 1 50,000 per acre in the study year,

In the Purbi Singhbhum study locali y, which in contrast to the employers ot

000 in the migration has also played a part tn changm .uu

to ks 1i .75

compared m

Barddhaman district meant a more secure

Barddhaman district study locality, and

social relations of jati. Different Re roof new cooking utensils or clothing.

from Rs 5,000 to Rs 60,000 (depending mg

manual work have meant that Migrants were more assertive jn their

on quality) in the other source

local.- ologm

‘3 Benias have not had access

ties Inequality has increased sharply and

g

wl— —

■smuchhigherthanintheothersourcearea

o the

the migration

m.gra

iS —ble M.l

I

.1

i

i

w

■

i

1997 and 1999 because of three consecu

tive years of drought. For those who had

previously migrated to invest in their own

land, these years meant continuing o

migrate but for different reasons - for

survival. Agriculture had failed almost

t

those dispensing development grams^rrom

the Block Development Office. Migra

has been important in enabling people to

make more choices about their economic

1 gg9

Boro transpianting 2000

0

0

13

2-14

2-30

2-30

ijn

1-30

16

15

Source: Migration survey.

Economic and Political Weekly

4554

fl

“tX" S de

study localities. Using data on. the rupees migration have ^..abled

enabled some Mai

*

a women

ed b Rogaly and Coppard (2001),

equivalent of a basket of assets including t0 become increasingly bold in taunting

taunUng

J

of ch

land, we estimated a Gmi coefficient

_ - been reduced too

the Benias who have

in individual cases. Many migrants

reliance on symbolic untouchability

untouchabi y to

migrants Continue to depend

0.69 in the study year.

Seasonal outmigration from the locality

.

“"as forEmployment and fori

maintain their sense of

of supenonty.

superiority.

offers little opportunity for syuctural

Puruliya-Bankura Locality: No such

Dumka (Santal Parganas) Locality ■

change. Men are compelled to find work irrigation development was evident in

There were no dramatic agro-ecologca •

outside the district because there is insuf Bajnagarh (Puruliya), also on the

changes in Alopahari (Dumka) either. Here

ficient employment available locally, even Chhotanagpur plateau but further no .

there was less evidence of change in

m

though, for almost all crop tasks women West Bengal. Here, boro production has economic structures, than in the Puruliya

donothireoutlabour.Thisgenderdivision

locality.noevidenceofawtopre—

of paid work is part of the cause of the

high propensity to migrate among poor

Si^hbhum^ahtyTbut at the same time

men - men in the household are. respon w pump water from the tanks they con no major regressive change in terms of

sible for oringing in income to cover the trolled. Though the Rajas were major local — major regressive change

inequality.

•• , r

Economic

' * differentiation

J: e

costs «f.all family members. In the study employers in the aman transplanting and

among tneounuia.a

----- ,

Jocality, men tended to give their rem.f harvesting seasons, there was too htt e In the study year, the gmi coefficient ot

tances to their wives or mothers and these work to go around. Moreover, people were

wealth inequality was 0.33.

were spent mainly on debt repayment and reported to have migrated in greater num

Relations between Santhals in Alopahari.

bers (both for rice work and to work in on the one hand, and their landlord and

on food.

. .

In Rogaly and Rafique (op cit), we brick kilns) during the period between

explore how dependent women in nuclear

Gang Size by Study Locality and Season

families, left behind for a season by ma e

Table 8: Median

Boro Harvest

migrants, can be reliant on their own kin

Aman Harvest

Boro

Aman

Variable

Transplanting

in Jalpara. This may involve compromises Locality

Transplanting

in behaviour, including decisions about

9

11

16

Gangs

19

- - keep close kin available A|Opahari Dumka

reproduction, to

12

4

4

Median size

4

7

for physical security, loans, child care and

7

24

Gangs

50

. • __

Bajnagarh Puruliya

14

24

29

Median size

10

her support.

suppvit.

.

other

22

10

6

6

Purbi Singhbhum

:

. JalparaMurshidabad Gangs

5

5

5

Median size

0

to the Murshidabad-Bagn locality,

■2

0

9

Gangs

9

Upartola, the Purbi Singhbhum locality, is Upartola P Sing

Median size

in an area of low population density.

However, it too has seen change

<

w in agri- Source: Migration Survey.

and Days Worked Range and Median by Season

culture, with action seen over the last decade

Table 9: Gang Size

(Destination Area)

to dam the nearby river and lift w^eT^or

---------------------------Si^e

No of Days

No of Days No DaVs

irrigation of boro rice productton. This has-----Gang Size

Gang Size

Ranae

Median

Range

come out of individual initiative and Season

Range

Med'an__________

2^25

----------------- --------------- id

' 2-25

15

contacts between the family of a long-----------2’60

0

2-14

7

4- 15

5- 35

4-27

a

December 8, 2001

I

<

>

|

I

.1

I

' i'

;5tm

■'W

I

' 1

I

■'i

■•I

■ftl

I

*B

.;s|

-

■

•->

I

through direct involvement in recruitment individually. This was part of a general

other creditors outside the locality, on the

from source areas. Employers from the picture of competition among employers,

other, remained highly unequal, however.

study locality in Barddhaman district whose religion and caste backgrounds

Migration for manual work, not only to

varied. Partly as a result of these differen-.

Barddhaman but also to the north-eastern expressed their fears about having to stay ces, labourers migrating into Barddhaman

states and further afield on ministry of in source area villages. Their sense of district had more room for manoeuver to

defence contracts, has continued to be an coming from the central place, the place make ‘small choices’ in the precise details

important part of livelihoods. The local of modem agriculture and their urban white agreed with employers at home or in the

labour market is very small and most of collar aspirations, were, strengthened by labour market places. However, employ

the Santhals and others who migrated the experience. Santhals and Muslims who ers’ anxieties stemmed not only from labour

seasonally cultivated land as tenants for a had migrated from the study localities in shortages but also from the declining

large-scale ‘dikU’ (non-Santhal, in this case Bagri/ Murshidabad and Santhal Parganas profitability of rice production.

brahmin) cultivator who lived outside the (Dumka) saw themselves more than pre

The sub-regions feeding the West Benviously as members of larger groups, an

locality.

gal

‘rice bowl’ have varied agrarian struc

Outmigration was not a major cause of expected outcome when moving from the tures, as reflected in the wide range of

known

local

area

to

a

broader

playing

structural change in the Dumka study

inequality coefficients found in the study

locality, in contrast to the effect of the field. However, although Santhals met localities. There were.clear divergences

Jharkhand political movement in the 1970s, Santhals from other sub-regions, and at between study localities in patterns of

which saw interest rates on diku loans least three marriages were reported to have structural change resulting from migration

considerably reduced. However, a few happened this way, and Bagri Muslims ot in the study localities. Migration in the

individual migrants were able to save different jati came away with a heightened Puruliya locality enabled wage workers to

enough to move out of migration here. sense of their religious and territorial bring pressure to bear on the sensibilities

Land was commonly mortgaged for cash identities, these two groups were not found of local employers, in the Purbi Singhbhum

in Alopahari. Because of special legisla to spend time together at the destination. locality there was general movement out

tion designated to protect Santhals’ and Such non-interactive encounters helped to of migration, whereas economic compul-,

harden self-identification as Santhals and

other ‘adivasis’ land from passing into the

as Muslims. However, self-identification sion continued for different reasons for

hands of dikus, it could not be sold.

migrants from the Dumka (Santhal

Remittances would be used to unmortgage did not just vary across individuals and Parganas) and Murshidabad Bagri

land, and if production resumed, it was over the life-course, different aspects of localities.

possible for some people to sustain them a persons’ group identity became promi

The stories of individual migrants and

selves without migration. However, live nent at particular points in space.

their households varied too - some used

lihoods were highly precarious and when

remittances to invest and eventually thereby

Summing Up

crisis hit, often through expenses associ

to exit migration, others continued to have

ated with ill-health, it was likely that

no choice in the decision. Decisions were

This

section

has

reported

our

analysis

of

accumulated assets would have to be liq

embedded in particular structures of intra

uidated and migration again become nec why seasonal migration for rice work has household and broader kinship relations,

increased over the last 25 years in the Jhar

essary.

khand-West Bengal region. Characterising which migration could in turn challenge.

the region as a whole, we have also high Even in the localities from which family

Changing Social Identities

lighted important contrasts between sea migration was common (Puruliya/Bankura

and Dumka), kin were important in arrang

Table 3 summarises some of the main sonal migration for rice work there and ing for care of the house, livestock and

group self-identifications in the study sub seasonal migration elsewhere in India. dependents. For younger people earlier

regions. Group self-identifications are Further, looking within the region, we have decisions to migrate might be taken with

based on combinations of ethnicity, caste, illustrated the divergent trajectories of four parents’ permission, urged by parents (rare)

religion, nation and territorial space as major migration streams.

The methodological approach of this or against their wishes. In some cases

well as class. In the process of travelling

migration against elder’s wishes had the

across the countryside, spending time at two-layer comparative study has enabled effect of changing the balance of power

us

to

consequences

of

examine

causes

and

bus or rail stations, living and working in

in the household [Rogaly et al 2000].

the destination area, migrant workers’ seasonal migration as interacting- and

The findings suggest an overall pattern

social identities changed. These changes mutually determining. Social and political in which the element of choice for mi

were complicated because they included conditions as well as technological ones grants about who they work for and where

both instrumental use of identities in labour were necessary to the take off in West they go to work has increased. Many

market place negotiations, and changing Bengal agriculture. Migrants found em migrants are able to use the lump sum of

self-identifications through interactions ployment in larger numbers. They were in remittances they return with for purposes

with other migrant workers, with destina turn essential to the continued agricultural beyond loan repayment and food consump

tion area employers, and with others, such growth at the heart of south-central West tion. However, the process is still driven

as other bus passengers, drivers and con Bengal’s prosperity, which fed back into by an economic compulsion and the choices

ductors and stallholders selling snacks, tea increasing demand for workers.'4

Instead of using middlemen for recruit remain small. This is why changing social

and trinkets.

relations, including stronger group iden

Moreover, it was not only migrant ment as is common practice elsewhere in tities and opportunities to taunt and un

workers whose social identities changed, India, employers of rice workers in West settle employers, to get the upper hand

but also employers of migrants, in part Bengal’s Barddhaman district recruited

Economic and Political Weekly

December 8, 2001

4555

)

-4

I I

and pregnant and post-natal migrant women

I I

I

more demeaning experience. At the same Child Development Scheme-funded

time, such divisions among migrant work ‘anganwadis’. In reality, anganwadis across

ers and between migrants and local

the study region (source and destination

workers, play to employers’ interests in areas) were not functioning properly for

preventing a unified rural working class local women and children. The woman in

movement.

charge in the destination study locality

Migrant rice workers in West Bengal do

expressed great surprise that we even

IV

have many common interests: forexample, asked whether migrant women could at

A Political Approach to

a place to gather peacefully to negotiate tend. The idea seemed absurd to her.

contracts, rather than being lathi-charged

Migrants’ Rights

Because of this, such measures success

f

□ as Muslim men migrants gathered on the fully won, would be of benefit to both

___________

•

’ we ,found railway lines at Katwa regularly were m

In

one source area (Dumka),

migrants and non-migrants and therefore

migrants

to have been excluded from houseA successfui campaign for

Illiyil CU1UO UV7 Iiv* » w -----------------------.

------------fnr

nnor

investment in a labour shelter more widely acceptable than measures

grants

building

earmarked

forfamipoor fami

lies the Indira Awas Yojana, because away from the railway station could lead dedicated to migrant workers alone. A bus

stand health camp at Bankura is a rare

they were deemed likely to be absent dur

to a wider claim for rights to information. example of how health provision for re

ing the stipulated period for building. In

The state could be the target and success turning migrant workers can be organised

questions"^10!" why neonatal seasonally mightmakedaytodayandseasonalchanges

by a coalition of unions, NGOs, local

migrant women did not gain access to in labour market places (number

Government bodies, shopkeepers and oth

Integrated Child Development Scheme employers

emp|oyers and workers, going wage, likely ers. Those using it included both migrants*

potential

facilities were greeted with derision.

length of season) known to potentia

and non-migrants.

misrants; it would also be of use to

From such incidents and from the high migrants;

Changing mindsets on seasonal migra- ■

...

1 lw“*

------- 3 about and/or disin- employers.

tion and persuading influential people of*

the view that migrants have been central

tcrcst in seasonal migrants in conversa

to recent growth in prosperity in destina

tions with officials across 15 districts, we

among other things, an extension of the

tion areas will not be easy. However, we

can see that migrant rice workers are not

number of state-owned buses on West

hope this research makes a contribution to

willingly accommodated by the bureauBengal’s roads and improvements to those

that agenda. One result might be for areacratic machinery. This approach to mibased projects which have a reflex reaction

in making the experience less undignified

for migrants. Such group-identification,

combined with small amounts of power in

negotiation and at the workplace can be

important to migrants’ well-being (ibid).

I

•

t-

a

1 £

••

....... ...........

I'*!'

■----- to de-

velop the opposite tendencies. It might

health when

not just beca

to rLE«j - -------treatment, but also (and especia y)

cause of loss of wages. At the very eas ,

er term_ howeVer, those havfree health care might be campaigned for,

B

more control over

have broader

broader choices.

choices,

to south-central West “ckpayisalongwayoffforcasualworkers

sickpayisalongwayoffforcasualwor er

,f (hey have

What is specific

anywhere.

.

Bengal is that migrants have been pre- anywhere

children at This requires public investment in source

children at areas to counter the unnevenness of

.... and directly under

Migrants struggle to keep cn

vented from explicitly

school, including many children

■' the wages, of

chil ren them deveiOpment and economic opportunity.

cutting

of local

workers by

local workers

by aa

selves. Social debts are made with km;

,ng“political

investment would be most effective

strong

political party and one of its affiliaffili selves. Social e ts; are: m

exams; at.

at least one

8

I- ----------? — children return to take exams

lf.

ated organisations, in order to keep cr^‘

sub.regions It might inciude tm.pport, not least at elections. This child migrated’ toj earn the

the cost of clothes

1 h

class

supr—school. However,

has been

of practical benefit to migrant to wear to school.

However the

!th schooling

h

g

.nvestment in a localily

the one

has been of practical benefit to migrant

workers, and acceptable to local workers system has not respo de to

studied in Puruliya and non-agncultural

^m^^Newcompromisesmay

rceordestination

areas.

and to employers. New compromises may requirements dictatea

py g

enterprises in Murshidabad where land is .

have to be reached, if, as seems likely, ^idte^^-—

Migrants themselves could make

Migrants’ children’s.absences

fromst‘dy

pri moreofthe remittances they returned with

there is sustained pressure on the

the profitprofit- Migrants’

chddren s

in thee Puruliya/Bankura

study

ability of rice production with lower pro- mary

sh t0 jf health and education were actually free

mary school

school in

y d;

locality could be highlighted in a push to

draw attention to primary schools’ need to

only Jo.these

for migrant workers, but

However.migranlshavenoorgamsauon change,

no"only

new inveslmenis would nol fee limchange, not

for the children of manual workers more

broadly. In the destination area study

cent drop m

"Mlarednwurromdwcnsabnietand .uvaiuj,

locality, fcne was a 40 perX'-Sy

Appendix

attendanceby

bychildren

childrenof

ofBagdis;

Bagdis - mainly

in this case caste and religious) groups, attendance

y

•

3 in

m the

th cultivation

twQ main nce crops in

Indeedthestrongersub-nationalconscious- agricultural■ •labourers

seasons.

Many

were

covering

for parents

ness developed through the migration

P

Barddhaman district as in the rest of West

earning aaareuedthatinfants

wage.

process has enabled some migrant busy

busy_earnmg

Bengal; aman, transplanted in July and

Similarly, it could be argued that infants

workers, particularly Muslims and

policies and solidarity with migrants and

their inclusion in welfare schemes when

nr? awav from home cannot be a

ttpr for bureaucratic edict alone. Such

Ii il'

E

>=

-r

“

SXET”—” i. -

gsssssx

X X.%C“Xt“-on „ -dy »ed . nug-.

Economic and Political Weekly

4556

December 8, 2001

■

I

►

,

i

I

•it-J

3

1

i

I

-

-■

August, is harvested in November and

December, and boro, transplanted in Feb

ruary, is harvested in April and May.

The net sown area of Barddhaman dis

trict is 4,73,900 ha (Barddhaman District

Statistical Handbook, 1995). In 1993-94,

4,19,000 ha were planted with rice in the

aman season and 1,58,000 ha in the boro

season (Barddhaman District Holistic

Development Plan, Society for Holistic

Approach to Planning and Evaluation,

Kolkata, no date).

Barddhaman had a population of

6,919,698 according to the 2001 census.

Although at the time of writing the 2001

census breakdown of occupations are not

available, we can use the proportion re

porting themselves in the 1991 census as

primarily agricultural labourers (6.48 per

cent) and cultivators (9.12 per cent) to

estimate the number of people in each

occupational category in 2001. We thus

estimate there to be 4,48,000 and 6,31,100

people who would have reported them

selves as primarily agricultural labourers

and cultivators respectively in the 2001

census.

Four cultivators were asked in detail

about their labour requirements in the

previous aman and boro transplanting and

harvesting seasons. Their estimates for

transplanting were 8-10 person days per

bigha (uprooting, carrying seedlings and

transplanting) and 10-19 person days per

bigha at harvest (cutting, binding, stacking

straw, threshing and storing). Boro rice

usually yields significantly more per bigha

than aman. However, the cultivators’ es

timates did not provide evidence of the

difference between them.35

The higher end of the range for harvest

were estimates by people who would not

work in these tasks themselves nor expect

their family members to do so. The lower

end was estimated by two employers who

would expect themselves and other mem

bers of their families to do harvest work.

As they were asked to detail the direct

financial cost of cultivation they did not

include the opportunity cost of their own

labour.3*5

The range of total labour required in

each season for Barddhaman district is

thus:

Aman transplanting: 25,140,000 - 31,425,000

31,425.000 - 59.707,500

Aman harvest:

Boro transplanting: 9,480,000 - 15,800,000

15,800,000 - 21,014,000

Boro harvest:

The mean number of days spent away

across the 141 groups recorded in the

Economic and Political Weekly

migration survey for the year 1999-2000

was 16.80. However, this figure was

weighted downwards by the counting of

groups in the Murshidabad locality which

travelled out more than once per season.

The mean number of days for that locality

was 12.4, whereas the means for the other

three localities were 21.65, 19.53, and

23.00. We therefore assume for the pur

poses of this calculation that the length of

a season is 20 days. This is a crude assump

tion because season lengths vary. Boro

harvesting is often done at a faster pace

over less days, especially when people are

employed on piece rates.37

Therefore, we calculate the total number

of people required for each season of rice

cultivation in Barddhaman district to fall

within the following ranges:

Aman transplanting 1.257,000 - 1,571.250

1,571,250 - 2,985,375

Aman harvest

Boro transplanting 4,74.000 - 7,90,000

7,90,000 - 1,050,700

Boro harvest

If every one of the 631,100 cultivators

and 448,000 agricultural labourers esti

mated to be resident in Barddhaman dis

trict in 2001 (a total of almost 1,080,000

people) were to work throughout each

season in these tasks, there would still be

a major shortfall of at least half a million

workers in the aman harvest. However,

many of those classifying themselves as

cultivators prefer not to do transplanting

or harvesting work and thus the shortfall

is likely to be much greater.38

Importantly, these calculations were

consistent with our own observations in

five destination localities in Galsi, Memari,

Barddhaman Sadar and Katwa blocks of

Birbhum district and in Nanoor Block of

Birbhum district. In all these villages the

number of migrant labourers was higher

than the number of local wage labourers

in the peak seasons.

Our journeys around the countryside

during the seasons of outmigration and

return have included periods of detailed

observation trying to count migrants at

labour market places. Estimates have been

made by railway staff, bus drivers and

owners and shopkeepers. These numbers

are less reliable as estimates of the number

of migrants, as our own migration survey

suggests that in three of the four source

area localities labour market places were

used relative little for recruiting labour or

finding work.39 Moreover, we only stud

ied two labour market places in detail:

Bankura bus stand and Katwa railway

station and we could only briefly visit

some of the rest, for example, Tinkonia bus

December 8, 2001

stand and the railway stations at

Barddhaman and Guskara. Others, includ

ing, importantly Nadanghat in Nadia dis

trict, and Kusumgram in Barddhaman were

not visited.

At Bankura bus stand alone, stallholders

estimated that at the peak of aman harvest

recruitment as many as 10,000 to 15,000

migrants passed through the bus stand in

a day. The station manager at Katwa sta

tion, narrow gauge line estimated that at

the end of the season 15,000 to 20,000

migrants returned each day. Given that the

peak part of each main rice work season

can last for as much as 15 days, this could

mean 1,50,000 - 2,25,000 passing through

Bankura bus stand and 2,25,000 to 3,00,000

passing through Katwa railway station.

One of us estimated that 6,000 labourers

left for Barddhaman for boro transplanting

work from Dumka bus station on one day

in late January 1999. Bus operators inter

viewed reported that this outmigrating

season lasted for 15 days. This suggests as

many as 90,000 labourers left from

Dumka bus station alone. Such estimates,

each of which refer only to one part ot one

stream, do not contradict the scale of

the estimate above based on demand

calculations. 033

Notes

1 Our thanks especially to the migrant workers,

their employers, officials and others, who spent

lime and effort engaging with us during the

study. This research would not have been

possible without the direct and indirect support

of many colleagues, including coordination

and- research assistance by Somnath

Chattopaddhyay,research assistance by Sujata

Das-Chowdhury andMalini Munshi; sustained

insightful guidance from beginning to end

from the late Sunil Sengupta: valuable advice

from Nirmala Banerjee, Sonia Bhalotra,

Debabrata Bhattacharya, Partha Chatterjee,

Samantak Das, Jean Dreze, Arjan de Haan,

David Mosse, Nitya Rao and Samita Sen; and

the reflective feedback of others including

Mukulika Banerjee, Tony Barnett, Kumkum

and Ranjit Bhattacharya, Piers Blaikie, Rahul

Bose, Srabani Chakrabarty, Surendranath

Chatterjee. Meena Dhanda, Madan Gopal

Ghosh, John Harriss, Barbara Harriss-White,

Mark Holmstrdm, Vegard Iversen, Cecile

Jackson, Praveen Jha. Catherine Locke,

Richard Palmer-Jones, Kirat Randhawa. Kunal

Sen, Dikshit Sinha, Rene Veron and Glyn

Williams. The map was drawn by Philip Judge.

Rogaly is grateful to the Centre for Studies

in Social Sciences, Kolkataand he and Coppard

to Palli Charcha Kendra, Visva-Bharati, where

they were affiliated during the research, and

to those institutions’ respective directors Partha

Chatterjee and Onkar Prasad. We thank the

Department for International Development

• (UK) for funding. Views expressed and any

4557

___

Position: 3092 (2 views)