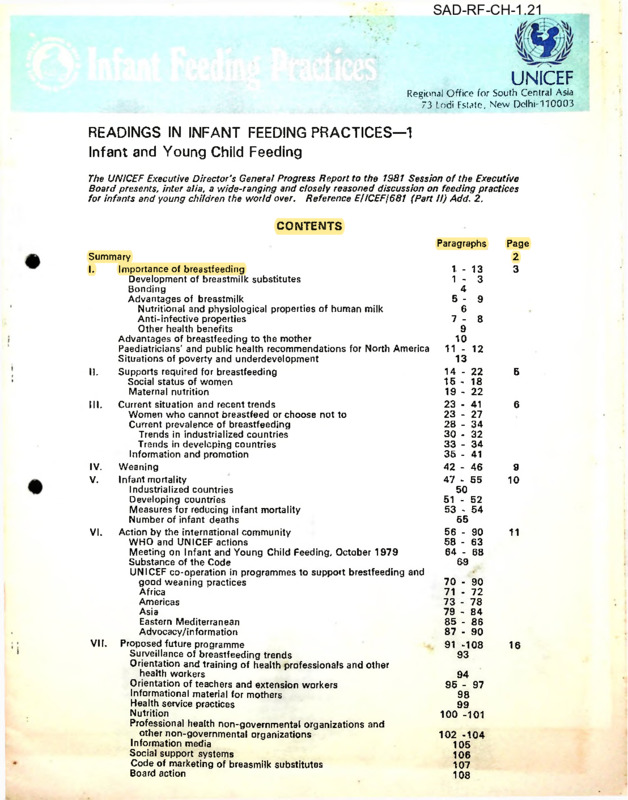

READINGS IN INFANT FEEDING PRACTICES—1 Infant and Young Child Feeding

Item

- Title

-

READINGS IN INFANT FEEDING PRACTICES—1

Infant and Young Child Feeding - extracted text

-

SAD-RF-CH-1.21

UNICEF

Regional Office for South Central Asia

73 Lodi Estate, New Delhi-110003

READINGS IN INFANT FEEDING PRACTICES—1

Infant and Young Child Feeding

The UNICEF Executive Director's Genera! Progress Report to the 1981 Session of the Executive

Board presents, inter alia, a wide-ranging and closely reasoned discussion on feeding practices

for infants and young children the world over. Reference EIICEFI681 (Part 11) Add. 2.

CONTENTS

Paragraphs

Summary

Importance of breastfeeding

I.

Development of breastmilk substitutes

Bonding

Advantages of breastmilk

Nutritional and physiological properties of human milk

Anti-infective properties

Other health benefits

Advantages of breastfeeding to the mother

Paediatricians' and public health recommendations for North America

Situations of poverty and underdevelopment

Supports required for breastfeeding

II.

Social status of women

Maternal nutrition

Current situation and recent trends

III.

Women who cannot breastfeed or choose not to

Current prevalence of breastfeeding

Trends in industrialized countries

Trends in developing countries

Information and promotion

Weaning

IV.

Infant mortality

V.

Industrialized countries

Developing countries

Measures for reducing infant mortality

Number of infant deaths

Action by the international community

VI.

WHO and UNICEF actions

Meeting on Infant and Young Child Feeding, October 1979

Substance of the Code

UNICEF co-operation in programmes to support brestfeeding and

good weaning practices

Africa

Americas

Asia

Eastern Mediterranean

Advocacy/information

VII. Proposed future programme

Surveillance of breastfeeding trends

Orientation and training of health professionals and other

health workers

Orientation of teachers and extension workers

Informational material for mothers

Health service practices

Nutrition

Professional health non-governmental organizations and

other non-governmental organizations

Information media

Social support systems

Code of marketing of breasmilk substitutes

Board action

1. - 13

1 - 3

4

5 - 9

6

7 - 8

9

10

11 - 12

13

14 - 22

15 - 18

19 - 22

23 - 41

23 - 27

28 - 34

30 - 32

33 - 34

35 - 41

42 - 46

47 - 55

50

51 - 52

53 - 54

55

56 - 90

58 - 63

64 - 68

69

70 - 90

71 - 72

73 - 78

79 - 84

85 - 86

87 - 90

91 -108

93

94

95 - 97

98

99

100 -101

102 -104

105

106

107

108

Page

2

3

5

6

9

10

11

16

2

SUMMARY

"Poor infant feeding practices and their consequences are one of the world's major problems,

and a severe obstacle to social and economic development."1 "Breastfeeding is an integral part

of the reproductive process, the natural and ideal way of feeding the infant, and a unique

biological and emotional basis for child development.”2

WHO recommends that breastfeeding should be continued if possible up to the age of 12 months,

or longer in some circumstances to provide a valuable nutritional supplement.34

. "Food comple

mentary to breastmilk will need to be introduced by 4-6 months; when the nutrition of the mother

is poor...it may often need to be introduced earlier."1

There has been remarkable progress in the technology of making infant formulas. Nevertheless,

scientific evidence is reconfirming the superiority of breastfeeding because of its support of the

bonding of mother and child and the psychological support of the child, the nutritional and

physiological properties of human milk, its immunological properties and other health benefits

extending into adult life, and its advantages for the mother.

Beginning earlier, but mainly in the twentieth century and especially since 1920, breastfeeding

has been declining in urban industrial areas. There has been a decline in the proportion of

mothers who start breastfeeding, and a shortening of the duration to less than three months

("premature weaning"). These trends are now being reversed in upper-income groups in many

industrialized countries. In the rural areas of many developing countries, breastfeeding is

maintained by a high proportion of mothers for 12 months or longer; in others it is falling. The

fall off in low-income urban and peri-urban areas is very significant because of the immigration

of rural population to these areas.

It is important for the health, development and even survival of infants that breastfeeding should

be protected and encouraged, and weaning foods given at the appropriate age. The raising of

the standing of women in their family and community, and the improvement of the nutrition of

pregnant women and nursing mothers, are two of the most powerful ways to support mothers

who want to nurse their babies. Good weaning practices can be encouraged by more

information, help with home and local processing of weaning foods, and social welfare systems

to supply foodstuffs to low-income families where required.

Infant mortality has declined to an average level of 13 per 1,000 live births in industrialized

countries, but it is still at 120 per 1.000 live births in developing countries (excluding China),

where there are 1 1 million infant deaths every year, Deaths during the period of weaning in

developing countries are at a level 15 times higher than in industrialized countries. Infant

mortality depends on many factors, and the available estimates cannot be directly related to

breastfeeding and weaning. Nevertheless, experience shows that better infant feeding practices

can make an important contribution to reducing infant mortality.

Child health problems related to infant and young child feeding practices have been a concern

to the governing bodies of WHO and UNICEF throughout the 1970s. This concern resulted in

the calling of the joint WHO/UNICEF Meeting on Infant and Young Child Feeding which took

place in Geneva, in October, 1979. It set our recommendations for the protection of breast

feeding and the adoption of appropriate weaning practices, including the drafting of a code of

marketing for breastmilk substitutes.

Important beginnings have been made in a number of countries, often with UNICEF co-operation,

in support of breastfeeding and good weaning. They need to be widely extended.

As a follow up to the October 1979 meeting WHO and UNICEF have been working together on

a joint programme of increased support to the practice of breastfeeding and the improvement of

weaning practices, including the following main items:

- orientation of health professionals and other health workers;

- orientation of the education system and other extension services in contact with mothers and

families;

- making information available to mothers through the health services, women's organizations

and the media;

- improvement of health service practices at time of delivery;

- nutrition of pregnant women and nursing mothers, and infants and young children, whose diets

need supplementing:

- family, community and social support systems for breastfeeding and good weaning practices; and

- introduction at international and national levels of a code of marketing of breastmilk substitutes.

The Executive Director recommends that the Board endorse the strengthening of UNICEF

co-operation in country programmes in the above fields.

1.

2.

3.

4.

Joint WHOIUNICEF Meeting on Infant and Young Child Feeding, Geneva, WHO, 1979, "Statement", para. 1.

Ibid., para. 7.

M. Cameron and Y. Hofvander, Manual on Feeding Infants and Young Children, Protein-Calorie Advisory

Group, FAO. Rome, Second edition, 1976, p. 23.

Joint WHOIUNICEF Meeting on Infant and Young Child Feeding, op. cit . "Recommendations", p. 15.

3

I.

IMPORTANCE OF BREASTFEEDING

Development of breastmilk substitutes

1. Until the second half of the nineteenth

century, breastfeeding was accepted as the

natural and inevitable way to feed infants; in

fact it has been a prerequisite for the conti

nuation of the human species. In a small

proportion of cases, the breastfeeding was done

by wet-nurses. From 1850 onwards there was

more use of artificial feeds (animal milks or

cereal paps), often with disastrous results?

2. Chlorination of water was introduced in the

United Statas in the 1880s; in the first decades

of the twentieth century pasteurized milk became

more widely available, and the kitchen ice-box

made storage feasible. The use of home-made

formulas based on cow's milk began to spread,

especially in the 1920s. The introduction of

tinned evaporated milk in the twenties made

home formula preparation easier for many, and

the duration of breastfeeding grew shorter

Commercially prepared formulas came into use

on a large scale in the 1 950s and 1960s.

As a result of considerable research and

development, they came closer to the compo

sition and digestibility of human milk?

Substantial declines in breastfeeding from the

1940s to the 1960s are documented for

Poland, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the

United States.

3. In so far as they led to the replacement of

inferior breastmilk substitutes, these develop

ments represented a great technical advance,

and together with bottles and teats that can be

kept clean in a modern kitchen, they saved

many infant lives. Further, it can be safely

assumed that more lives could be saved if

formula was made available through social

measures to families who need it but lack the

income to buy it? However, in recent decades

extensive research has confirmed the general

superiority of breastfeeding for both infants

and mothers. Many of the reasons apply just

as much in industrialized as in developing

countries.

Bonding

4. Breastfeeding supports emotional and

psychological bonding between the mother and

5.

child, and as a result, skin-to-skin contact and

breastfeeding are now recommended during the

first hours of the baby's life. The early close

contact and the physical mother-child inter

action, which they both enjoy, play an impor

tant role in the child's physical development

(of mouth and voice) and psychomotor

development. This interaction also provides

for natural adjustment to the infant's dietary

needs. “On demand" feeding rather than

bottle feeding becomes more practical?

Advantages of breastmilk

5. Breastmilk not only provides all the necessary

nutrients for growth during the first four to six

months of life, but carries antibodies which

protect the child from infections while its own

immune system is developing. Minerals such

as iron and calcium are in a readily assimilable

form? Breastmilk is also economical; the cost

of extra food for the mother is substantially

less—usually only about a quarter of.the cost

of infant formula.

Nutritional and physiological properties

of human milk

6. Human milk has classically been compared

with cow's milk because the latter is the most

available of the animal milks, and is the usual

base for infant formula, whether home-prepared

or manufactured. A joint commentary on

breastfeeding by the Nutrition Committee of

the Canadian Paediatric Society and the

Committee on Nutrition of the American

Academy of Paediatics says, “Differences in

the composition of human milk and unmodified

cow's milk for human milk have been known

for many years. Early attempts to substitute

unmodified cow's milk for human milk were

unsatisfactory for feeding infants

Newer

knowledge of nutritional and physiological

needs of infants and advances in technology

have led to the development of newer infant

formulas which provide many of the nutritional

and physiological characteristics of breastmilk.

However, there are still differences between

infant formulas and breastmilk, and we believe

human milk is nutritionally superior to

formulas ..“The statement goes on to discuss

composition and factors affecting digestibility

and absorption with regard to fat and

cholesterol, protein and iron.5

10

9

8

7

6

Joe D. Wray* “Feeding and Survival: Historical and Contemporary Studies of Infant Morbidity and Mortality ,

paper to be published in Advances in International Maternal and Child Health, vol. II, Oxford University Press.

6. S. J Fomon, Infant Nutrition, Second edition, Philadelphia, Saunders, 1974, chapter 1; D.B. and E.F.P.

Jelliffe, Human Milk in the Modern World. Oxford University Press. 1978, chapter 10; and B. Vahlquist.

"Evolution of Breastfeeding in Europe", Envi ronmenta! Child Health. February 1975.

7. On the other hand, there are unnecessary risks in using artificial feeding where breastfeeding could be done,

especially in conditions of poverty, as explained below.

8. A.M. Raimbault, "Breastfeeding; Influence on the Child's Development", Children in the Tropics.

No. 96, 1974.

9. "Background paper prepared by WHO and UNICEF" (FHE,’IC/79 3) for Joint WHO/UNICEF meeting on

Infant and Young Child Feeding, Geneva. 9-12 October 1979. See also L Hambraeue, "Proprietary milk

versus Human Breastmilk in Infant Feeding" in Pediatric Clinics of North America, vol. 24, No. 1,

February 1977.

10. "Breastfeeding". Pediatrics, vol. 62, 1978, pp 591-601.

4

Anti-infective properties

7. Human milk contains living anti-infective

factors which colonize the infant's intestines and

assist in resistance to infantile diarrhoea or

gastro-enteritis, and respiratory and some other

infections. Colostrum, in the first phase of

lactation, is particularly rich in these. They do

not exist in formula which has to be heattreated.10

11

8. As a result, breastfed infants have lower

rates of infection, both digestive and respi

ratory, than bottle-fed infants, and the episodes

of diarrhoea are of shorter duration and less

grave. This appears to be true not only under

conditions of poor environmental sanitation,

but also in middle-class communities in the

United States.12

Other health benefits

9. There are other benefits as well. Breast

feeding minimizes early exposure to various

foods that might produce allergies. Breastfeed

infants have a lower incidence of allergic

manifestations such as eczema, rhinitis and

asthma in children and also later in life.

Breastfeeding reduces chances of over-feeding

in early life, which may thus tend to prevent

long-term obesity. Cholesterol in human milk

may help constrain cholesterol buildup later in

life.13

Advantages of breastfeeding to the

mother

10. In addition to the bonding process between

mother and child, breastfeeding has a number

of advantages for the mother, including

promotion of the involution of the uterus, and

loss of extra fat stored during pregnancy, and

the restoration of the figure. Breastfeeding

also extends the average period of contracep

tion after giving birth. "Breastfeeding is best

for the health of the young baby, but also for

the health of the mother including the physical,

emotional, and psychological aspects of her

health."1* If the mother is malnourished,

these advantages may be more than counter

balanced by maternal depletion, 1516because

she will continue to feed her baby reasonably

well, at any rate during the first months, but

at the expense of her own body stores

(paras. 19-22).

Paediatricians' and public health recom

mendations for North America

11. The Nutrition Committee of the Canadian

Paediatric Society and the Committee

on Nutrition of the American Academy of

Paediatrics concluded their review of breast

feeding with the following summary :

"(a) Full-term newborn infants should be

breast-fed, unless there are specific contra-indi

cations or when breastfeeding is unsuccessful;

(b) Education about breastfeeding should be

provided in schools for all children, and better

education about breastfeeding and infant

nutrition should be provided in the curriculum

of physicians and nurses. Information about

breastfeeding should also be presented in

public communications media;

(c) Prenatal instruction should include both

theoretical and practical information about

breastfeeding;

(d) Attitudes and practices in prenatal clinics

and in maternity wards should encourage a

climate which favours breastfeeding. The staff

should include nurses and other personnel

who are not only favourably disposed toward

breastfeeding but also knowledgeable and

skilled in the art;

(e) Consultation between maternity services

and agencies committed to breastfeeding

should be strengthened; and

(f) .Studies should be conducted on the

feasibility of breastfeeding infants at day

nurseries adjacent to places of work subsequent

to an appropriate leave of absence following

the birth of an infant."18

12. The American Public Health Association in

a policy statement on infant feeding in the

United States said :

"Since feeding of infants during their first

year is an important determinant of

lifelong growth, development, and health,

education on infant feeding should be

viewed as a current public health concern...

The position (paper) and supporting

documentation should be used by members

of the Association to develop local policies

and programmes to support breastfeeding

11. Human Milk in the Modern World, op. cit., chapter 5.

12. A S Cunningham, "Morbidity in breast-fed and artificially fed infants". Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 90, No. 5'

May 1977; S.R. Larsen and D. R. Homer, "Relation of breast versus bottle feeding to hospitalization for gastro

enteritis in a middle-class United States population". Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 92, No. 3, March 1978.

On the other hand, F.O. Adebonojo, "Artificial versus breastfeeding: Relation to.infant health in a middle

class American community", Clinical Pediatrics, vol. 11. 1972, p. 25, found no difference in resistance to

infection,

13. "Background paper prepared by WHO and UNICEF", op. cit., pp. 7-13.

14. Joint WHO]UHICEF meeting on infant and Young Child Feeding, op. cit., p. 22.

15. Human Milk in the Modern World, op. cit. chapter 6.

16. "Breastfeeding", Pedia'rics, op. cit., p. 598.

L

5

and informed infant feeding practices...

Human milk from the healthy mother is the

best known food for nourishing her infant.

To ensure successful production of milk,

education in breastfeeding should be

provided during prenatal care and the

postpartum period. Hospital obstetrical

care procedures should facilitate early

nurturing...17

Situation of poverty and under

development

13. There are additional reasons why breast

feeding is superior to artificial feeding in

situations of poverty and underdevelopment.

Breastfeeding gives the young infant the liquid

required and avoids the need to give water

that is often not clean. The cost of formula is

high in relation to average earnings, so it is

often over-diluted, and the infant is underfed.

Usually, there are no satisfactory facilities for

cleaning and sterilizing bottles and teats.

The cost of fuel is generally high either in

money or in time spent gathering sticks. There

is no refrigeration for keeping formula between

feedings, so it should be freshly made on

demand. As a result of the extreme difficulty

of maintaining hygienic conditions, and the

absence of immune agents in the formula,

bottle-fed babies living in poverty conditions

are at a much higher risk of diarrhoeas which,

in turn, contributes substantially to precipitation

of malnutrition. The continuation of diarrhoeas,

respiratory infections and malnutrition leads to

a higher infant death rate.

II. SUPPORTS REQUIRED FOR

BREASTFEEDING

14. One of the obvious ways to protect and

encourage breastfeeding is to make it more

feasible for the mothers who want it. The

breastfeeding mother needs the support of her

family, her community and the society to which

she belongs. The situation regarding two

subjects, the status of women and maternal

nutrition, is described below The section on

policies and programmes takes up additional

items (paras. 91-108).

Social status of women

15. While the mother is pivotal in matters

affecting her child's health, she may not, in

fact, be taking an active part in decisions

affecting it. This depends particularly on her

expectations about determining her own life

style, the information to which she has access,

and the weight given to her opinions by her

family and community. These factors are

interrelated. Improving her education, her

access to information and her literacy will also

raise her influence; so will opportunities for

earning income, e.g., through women's

associations, co-operatives, etc. Raising the

level of women's education and standing in

the family is one of the most powerful means

for improving the well-being of young children.

This applies with particular force to infant

feeding.

1 6. In feeding her infant the mother will

choose, if she can, what she considers to be

best for her child. The mother needs

information on breastfeeding and on the

interaction of nutrition, child diseases and child

development. She and her family also need

an understanding of the extra food required

for her during pregnancy and lactation, of

anaemia and of the risk of maternal depletion

(paras. 19-22). In many instances, she does

not have access to such information. Her

instruction may come from her own mother,

relatives, friends, or health workers. Where

family and other support systems are not close

by and the health services are either not

available or unsympathetic, the possibilities

for choosing breastfeeding are lessened

considerably. For the disadvantaged, who may

already feel inadequate, the chances of

receiving positive information and instructions

are even less.

17. Conflicting messages may come into play

that may make it difficult for women to make

the decision to breastfeed. For example, the

traditionalist view in favour as opposed to the

modernist who sees breastfeeding as limiting

women to a nurturing role; erotic images of

the breast depicted in the media as against its

natural feeding function; and advertisements

emphasizing the convenience of infant formula

feeding as compared with feeding on demand.

18. For women to breastfeed, protection and

support is needed at all levels. The objectives

of UNICEF co-operation in programmes

affecting expectant and young mothers is to

assist them to become more self-reliant in the

knowledge needed to make informed decisions,

and in their opportunities for arriving at

decisions that will provide the best childrearing possible under the circumstances.18

Maternal nutrition

19. At the beginning stage of her pregnancy

a woman weighing 50 kilogrammes (a weight

typical of many women in developing

countries), needs 2,000 kilocalories per day

with moderate activity. During the second

half of pregnancy the need for calories is

increased by 16 per cent and that of protein by

30 per cent. During the first six monts of

lactation the need for calories is increased by

17. "Infant Feeding in the United States", American Journal of Public Health, vol. 71, No. 2, February 1981,

p. 207.

18. Joint WHOIUNICEF meeting on Infant and Young Child Feeding, op. cit. pp. 21 -22. covers part of the above.

6

25 per cent and that of protein by 50 per cent,

and vitamin A by 70 per cent. Also, there is

an additional need for iron among women

whose stores have been depleted.10 An

increase in the daily diet of, for instance,

cereals, of about 200 grammes of cereal plus

vitamins.and minerals, would be needed to

provide the additional needs for calories and

other nutrients during late pregnancy and

lactation

20. Under conditions of poverty, a dietary

supplement even if available is often not

eaten but shared with other members of the

family. Women arrive at conception with

depleted nutrient stores resulting from

generations of poor nutrition, inadequate food

intake, and the drain of infection, parasites,

physical labour or closely spaced pregnancies.

Weight gains during pregnancy are much

below those in well-nourished women, anaemia

from iron and folate deficiency is common,

maternal mortality rates are high, and babies

of lower birth weight are prduced who have a

higher risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Although the foetus receives considerable

protection at the expense of the mother, she

is less able than a well-nourished mother to

pass on nutrients for foetal needs, nor is she

able to build up her own reserves to ensure

prolonged and successful lactation. Many

mothers may go on to their next pregnancy

without an opportunity to achieve full

nutritional recovery.

21. Improved maternal nutrition merits special

attention for three major health objectives :

- Preservation and improvement of the health

status of the mother so that she can be

healthy, economically productive and socially

active;

- Improved birth weight, which gives the

newborn a better start for survival and

healthy growth; and

- Provision of breastmilk for the infant in the

first 4-6 months. The basic elements in a

broad approach to maternal nutrition are

skills for healthy living, improved diet,

improved spacing in pregnancy and health

care during pre-natal and post-natal periods.

22. Undernourished women who take dietary

food supplements show increased maternal

weight gain, a small improvement in the baby’s

birth weight and reduced morbidity and

mortality in their infants.19

20 There is also

substantial positive experience with vitamin

and mineral supplementation during pregnancy.

Policies and programmes addressed to these

needs are listed in section VII.

III.

CURRENT SITUATION AND RECENT

TRENDS

Women who cannot breastfeed or

choose not to

23 In regions where breastfeeding is taken

for granted as the natural way to feed infants

in normal circumstances, nearly all infants are

breastfed by their mothers. Only the death

or illness of the mother prevents it. In

traditional societies, fewer than 1 per cent of

mothers are unable to breastfeed.21 Thus the

strictly "physical" constraints on breastfeeding

are not extensive, unlike family, psychological

and cultural constraints.

24. Successful breastfeeding requires psy

chological confidence on the part of the

mother—she should not doubt her ability

to breastfeed, nor worry about whether she is

adequate, or whether substitutes would be

better. It is probably an advantage to have

seen breastfeeding by her own mother, or in

her own surroundings. She needs the support

of her family, of health workers who are in

contact with her, and of the surrounding

community and society. "Given adequate

instruction, emotional support, and favourable

circumtances, 96 per cent of new mothers can

breastfeed successfully."22

25. In many "modern" communities these

psychological underpinnings are no longer

present. In such communities there is a

significant percentage of mothers who want

to breastfeed, but are incapable of doing so.

Similarly, the period after which the mother's

milk supply begins to decline, leading her to stop

breastfeeding because of "insufficient milk",

is largely culturally determined.23 Presumably

this confidence can be rebuilt, perhaps in the

next generation. "With adequate teaching and

support, almost all mothers are capable of

breastfeeding and solving any problems which

may arise: The best teachers will be breast

feeding mothers."24

26. A further group of mothers does not

breastfeed because the physical support systems

19. Manual on Feeding Infants op. cit., table 2.

20. "Report of the Third Metting of the Administrative Committee on Co-ordination/Sub-Committee on Nutrition,

Consultative Group on Maternal and Young Child Nutrition". Food and Nutrition Bulletin, United Nations

University, vol. 3, No. 1, January 1981.

21. "WHO Collaborative Study on Breastfeeding", MCH/79.3. table 2.1, p. 15. The number of rural mothers

breastfeeding in Ethiopia, India, Nigeria and Zaire was recorded as 100 per cent at nine months.

22. Nutrition Committee of the Canadian Pediatric Society and Committee on Nutrition of the American Academy

of Pediatrics, "Encouraging Breastfeeding", Pediatrics, vol. 65, No. 3, March 1980.

23. "WHO Collaborative Study on Breastfeeding", op. cit., p. 14.

24. Joint WHOIUNICEF Meeting on Infant and Young Child Feeding, op cit.. p. 10.

7

are lacking in the family or in society, e.g.,

they have to go out to work in circumstances

where breastfeeding is not possible.

27. A further group may decide not to breast

feed for other reasons, including their own

choice.

(b) At the other end of the socio-economic

scale, rural populations in many developing

countries maintain a high proportion of

breastfeeding until the baby is 12 months old,

such as 99 per cent in India; 98 per cent in

Ethiopia; 97 per cent in Nigeria; and 96 per

cent in Zaire. However, in some countries

there has been a substantial fall-off also in

rural areas, to levels such as 40 per cent in

Chile, and 63 percent in the Philippines.

Current prevalence of breastfeeding

28. In most industrialized countries, a high

proportion of mothers begin to breastfeed but

(c) The urban poor are in an intermediate

stop quite soon, a phenomenon described as

position between the economically advantaged

"premature weaning". In most developing

and rural areas, with Ethiopia, India, Nigeria

countries, there is a big difference between the

and Zaire showing a high level at 3-4 months,

prevalence of breastfeeding in urban and rural

which is also well-maintained to 6-7 months;

areas. "Partial breastfeeding" is a further

but Chile, Guatemala and the Philippines

complication, e.g., the mother may be away

showing a substantial fall-of :

from her baby at work and obliged to arrange

for artificial feeds (unfortunately, the reduced

Per cent of mothers breastfeeding

infant sucking often leads to an insufficient

milk supply and the early termination of

at 3-4 months at 6-7 months

breastfeeding). Thus, it is difficult to describe

Chile

80

40

the present situation through the use of a

single measure. Somewhat arbitrarily the

Guatemala

76

73

following paragraphs use approximately four

Philippines

61

53

months as a convenient age at which to

measure the prevalence of breastfeeding,

Because of increasing migration from the

where there is a choice of date. Though it is

country into peri-urban areas, this group is

recommended to maintain breastfeeding for

particularly indicative of current trends,27

1 2 months or even longer if possible, the most

important period is the first four to six months.2526

Trends in industrialized countries

After that age it is in any case, necessary to

30. In industrialized countries, beginning early

begin to introduce complementary weaning

in the twentieth century, breastfeeding patterns

foods.

showed a downward trend but it is now being

reversed. In the United States and Western

29. During 1975-1978, WHO organized a

Europe, there was a dramatic decline beginning

study of breastfeeding by collaborating centres

in the 1930s and continuing through the

in nine countries and covering 23,000

1 960s. For example, in the United States in

mothers.25 The prevalence varies widely,

1920, two out of three mothers breastfed their

suggesting that the situation is evolving, and

first child, but between 1936 and 1940 only

is at different stages of evolution in different

one in three mothers did so

By 1972 only

countries. However, there is a considerable

28 per cent of infants born in the United States

uniformity of pattern within socio-economic

were being breastfed at one week; 15 per cent

groups:

by two months, and 5 per cent by six months.28*

(a) Among the economically advantaged,

breastfeeding usually falls off rapidly with the

age of the baby. While at 1-2 months, 61

per cent of infants are being breastfed in the

Philippines; at 3-4 months the figure is 27

per cent. The comparable figures for

Guatemala are 44 per cent and 29 per cent;

for Chile the figures are 80 per cent and 56

per cent There are also countries where this

fall-off has not occurred at the age of 3-4

months, e.g., 100 per cent in Zaire; 96 per cent

in Nigeria; 84 per cent in India;

31. Similarly, in Sweden, official statistics

show that in 1944 about 85 per cent of the

mothers were breastfeeding their infants at

two months, and 55 per cent at six months.

By 1970, 35 per cent were breastfeeding at

two months, under 5 per cent at six months.18

In England; it was estimated in 1969 that

only 33 per cent of the mothers fully breastfed

beyond the first four weeks, and in France an

investigation of national scope in 1972 found

that 36 per cent of the mothers were breast

25. ' Background paper prepared by WHO and UNICEF", op. cit.. p. 22.

26. • WHO Collaborative Study on Breastfeeding", op cit. The nine countries were Chile, Ethiopia, Guatemala.

Hungary, India. Nigeria, the Philippines, Sweden, and Zaire.

27. Ibid, table 2. 1.

28. Infant Nutrition, op. cit.. chapter 7; H.F. Meyer, "Breastfeeding in the United States", Ciinica! Pediatrics.

December 1968, pp. 708-715.

29 S. Sjolin, Semper Nutrition Symposium. Stockholm, 1973.

8

feeding their child on the fifth day.30

32. In the last decade there has been a reversal

of these trends in both Europe and North

America. In Sweden, for example, a WHO

study in 1976 showed that 93 per cent of the

mothers in the sample initiated breastfeeding

after delivery, and at four months almost 50

per cent of them were still breastfeeding,

although with regular food supplements.31

Other reports of substantial increases in

breastfeeding have come from Australia,

Denmark, France, Japan, Norway and the

United Stales. The report of the French

study concluded with an interesting obser

vation, that among French women, breast

feeding is not viewed as a survival of the past;

on the contrary, it is associated with modern

techniques (use of contraception and health

checkups during pregnancy).32

to 50 per cent,34 which seemed still to be the

proportion in the collaborative study. Declines

have also been documented in Brazil, Chile,

Mexico, and Thailand.35

Information and Promotion

35. In 1910, Dr. I.E. Holt in an article "Infant

and mortality and its reduction, especially in

New York City"3637 said “Little or nothing has

been done systematically in this country to

encourage maternal nursing... In New York

we have been so much engaged in the

furtherance of the best methods of artificial

feeding that means of promoting maternal

nursing have not received due consideration.

We must be on our guard lest with our day

nurseries and milk depots and other means we

do not encourage artificial feeding and

discourage maternal nursing./ In 1910, 85

per cent of mothers were reported to be

breastfeeding for at least three months.

Trends in developing countries

33. The situation in developing countries has

been studied less than that in industrialized

countries, and the information reported does

not go as far back

The situation revealed at

the moment of the WHO collaborative study

seems to:be a “still photo" of a process of

decline in breastfeeding. As mentioned above

in paragraph 28, breastfeeding among urban

economically advantaged families falls off

rapidly with the age of the child. Unlike the

situation in industrialized countries, women

with more education were breastfeeding less.

Among urban low-income families breatfeeding

also falls off in many countries, though less

rapidly. In rural areas in many countries

breastfeeding is well maintained until 12

months or longer. This seems to confirm

what commonsense suggests, that trends

spread from the economically advantaged to

the new migrants into urban areas, and then

back to the rural areas with which they

maintain some contact. Furthermore, countries

whose “modernization" has been going on

longer, e.g., the Philippines, Guatemala, and

Chile have a generally lower breastfeeding rate

in rural areas than say Nigeria and Zaire.33

In the Phillippines in 1955, 90 percent of

babies born in low-income areas of Manila

were still being breastfed at 1 2 months post

partum, but by 1964 the proportion had fallen

36. Diversion from breastfeeding through

practices in medicine and health services is a

matter of concern to this day. In recent

decades the problem has been accentuated by

the promotion of commercial breastmilk

substitutes through advertising to the public

and through medical and health personnel and

health service systems. There is fairly general

agreement, including in codes that have been

adopted by some of the infant formula

companies that such promotion e.g., through

the use of milk nurses, direct promotion to the

mother, etc., must be controlled.

37. The WHO collaborative study noted that

in some developing countries where the

prevalence and duration of breastfeeding was

low, there was also intense marketing and

sales of breastmilk substitutes. In some

countries information about commercial

products was sometimes provided within and

through the health services, be it through

printed material, direct contact with represen

tatives of commercial concerns or through

free-sample distribution.3’

38. On one occasion. Dr. G.J. Ebrahim,

Institute of Child Health, London University,

received letters from some 50 concerned

paediatricians working in 13 developing

30. “Background paper prepared by WHO and UNICEF", October 1979, PHE/ICF/ 79 3, pp 19-20; Y. Hofvander

and S Sjolin, "Breastfeeding, trends and recent information activities in Sweden", Department of Paediatrics,

University of Uppsala (Sweden) 1979.

31. Ibid

32. C. Rumeau-Romquette and M. Deniel, "L' allaitement maternel au cours de la periode neonatale". Archives

Francaises de la Pediatrie, 1977, vol. 34, pp. 771-780.

33. "WHO Collaborative Study on Breastfeeding", op. cit., table 2. 1.

34. Background paper prepared by WHO and UNICEF, op. cit., p. 20.

35. Human Milk in the Modern World, op. cit., chapter 11; J. Knodel and N. Debavalya "Breastfeeding in

Thailand: Trends and Differences, 1969—1979", Studies in Family Planning, vol. XI, No. 12 (1980).

36. Jouma! of the American Medical Association, vol. 54, 1910, pp. 682-690.

37. "Background paper prepared by WHO and UNICEF", op. cit., p. 22.

9

countries describing promotional practices

they had observed.38

39. Measurement of effects of specific

promotion is known to be difficult. Never

theless, certain approaches are commonly used

because of a general acceptance that they

have some significant effect. Hence adver

tising to the public in the media and promotion

at point of retail sale are assumed to be

effective inducements. Since it is impossible

to direct such promotion only to those who

have decided not to breastfeed, otherwise

acceptable messages can have harmful side

effects

A flow of controversial statements

and demands through the media and

advertising interact with other aspects of

changes through urbanization to disrupt the

sense of security that is needed for successful

breastfeeding.3940 Professor Sjolin, University

Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden, in a recent letter

Lancet (7 March 1980), said that normal

marketing methods should not be used for

breastmilk substitutes.

40. T.H. Greiner, in a study in St. Vincent,

found that infant food brand-name recall by

the mother was associated with earlier

supplementation with commercial infant foods

and earlier weaning 10

41. Recent studies of a low-income population

by the Institute of Preventive Medicine of the

Paulista School of Medicine have shown the

permeation of promotion of milk powder and

formula through medical and health personnel

to the mothers at maternity clinics. Only 6

per cent of mothers received information on

breastfeeding but most were informed about

formula feeding. The majority of the doctors

interviewed (82 per cent) believed that the free

distribution of breastmilk substitutes had great

influence on the decline of breastfeeding.41

IV.

WEANING

42. Weaning 42 is the second main aspect of

infant and young child nutrition, and in

conditions of ignorance or poverty presents

serious problems of child health and deve

lopment.43 Normally, breastfed children grow

at the same rate all over the world up to the

age of four to six months, when the mother's

milk is no longer sufficient and complementary

semi-solid or solid foods should be introduced.

Typically, in low-income areas the infant’s

growth begins to falter at this age, i.e., it falls

behind the reference pattern of the well-fed.44

While mortality is highest during the first year

of life, the proportion of malnourished children

(among survivors) is highest during the second

and third year of life, and typically reaches a

peak at about 24 months. In rural areas where

breastfeeding is almost universal, the current

pressing nutritional problems are to protect

breastfeeding and to ensure the timely

introduction of complementary foods, and

prevent and treat diarrhoeal diseases. It is a

problem of information as well as poverty,

because the requirements of the infant are

small in relation to family food consumption.

43. In addition to the risk of an insufficiency

of complementary food, the change-over from

sterile breastmilk with its anti-infective factors

to animal milk, semi-solid and solid foods

which often have to be acquired, stored and

fed in unsanitary fashion brings the highest rate

of infection, particularly of the gastro

intestinal tract, that the child encounters in an

entire lifetime.45* The young child mortality

rate (between one and four years), though

much lower than for infants, is typically 15 per

1,000 for each year, some 15 times the rate

found in industrialized countries.44 Thus the

average of 30 deaths per thousand during the

two-year weaning period (taken as the second

and third year of life) amounts to one quarter

of the average 120 deaths per 1,000 during

infancy.

44. "Foods that are locally available in the

home can be made suitable for weaning, and

their use should be strongly emphasized in

health, education and agricultural extension

programmes. Foods traditionally given to

infants and young children in some populations

are often deficient in nutritional value and

hygiene, and need to be improved in various

38. The Lancet. November 27 1976, p. 1194.

39. Stig Sjolin, Semper Nutrition Symposium. Stockholm, 1973. See also Human Milk in the Modern World.

op. cit.. pp. 225-233

40. T H. Greiner, "Infant Food Advertising and Malnutrition in St. Vincent", Cornell University, Ithaca

(New York), 1977.

41. Research project on the impact of dietary habits on the nutritional condition of nursing infants and

pre-school children, April, 1980.

42. "Weaning" as used in this paper means the transition from mother’s milk or formula to regular family food,

and usually extends over 18-30 months (the "weaning period"). It is not used to denote the moment at

which nursing stops.

43. N.S. Scrimshaw aud B.A. Uuderwood, "Timely and appropriate complementary feeding of the breastfed

infant - an overview:’. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, United Nations University, vol. 2, No. 2. April 1980. p. 21.

44. As recorded for example in the guidelines on "growth charts:’ (A growth chart for international use in

maternal and child health care. WHO. 1978).

45. Mannal on Infant Feediug. op. cit.. chapter 3.

46 World Development Report. 1980. World Bank, table 21. average of low-income and middle-income countries

10

ways. Mothers need guidance to improve

these traditional foods through combinations

with other foods available io them locally.

Countries should determine the need for

subsidizing weaning foods or otherwise

helping to ensure their availability to lowincome graups."47 Section VII refers to action

about these points.

45. The use of complementary or weaning

foods may need to be continued to the age of

between one-and-a-half to two-and-a-half

years, by which time a transition to the house

hold diet can be completed. The nature of the

household diet affects the age at which the

weaning process can be finished, according to

its bulk, its lack of protein, the presence of

strong spices, etc.

46. Industrially produced weaning fonds are a

convenience; usually the lower-income families

cannot afford them. UNICEF for many years

was co-operating in country programmes to

produce lower-priced milk products or weaning

foods: however, in low-income countries these

could not be made available to the low-income

population through subsidy on a sufficient

scale. Hence, UNICEF is now focusing its

co-operation on programmes for the preparation

of local foods in the household or in the

community.

V. INFANT MORTALITY

47. It has been pointed out above that

breastfeeding avoids sources of infection;

conveys protection against infection; and

produces a better nourished and more resistant

infant, especially in families who cannot afford

the necessary quantities of breastmilk substitutes

(paras. 5-10). Poor infant feeding practices

lead to illness on a large scale, and death on

a much smaller scale. Usually it is only the

latter that is recorded in the statistics.

48. There is no simple connection between

estimates of infant mortality rates for a country

and bottle feeding; infant mortality results

from far too many other factors as well.

Infant mortality 4849appears to have been

declining during the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries in the now industrialized countries,

and during the twentieth century in the

developing countries. The decline began long

before the introduction of bottle feeding

and has continued during the bottle-feeding

period. Rural areas of countries where

traditional ways of life continue and where

breastfeeding is high, also have high infant

mortality (e g , Nigeria, Zaire). The reasons

include lack of education and information

among mothers, poor maternal nutrition, lack

of knowledge and resources for weaning foods,

and lack of health services. There is sufficient

evidence to show that under conditions of

rural poverty, risk of infant death would be

even higher in the absence of breastfeeding.

In other words, breastfeeding has a very

important role in preservation of infants' lives

and prevention of further deterioration in

areas of high infant mortality.

49. The important fact is that in developing

countries infant mortality remains alarmingly

high, on the average 10 times the level of

industrialized countries. Hence the search for

all available measures to reduce it, to which

the improvement of infant feeding and weaning

can make a signiticant contribution.

Industrialized countries

50. The earliest records are for death rates of

the population as a whole, rather than infant

mortality. However, wherever the death rate

is high, infant mortality accounts for a sub

stantial part. Hence, it is significant that in

modern times, records show a declining death

rate beginning first in Sweden in the eighteenth

century, and in the nineteenth century

beginning in France and England.40 There are

also Swedish records of infant mortality, with

a decline beginning in the mid-eighteenth

century.50 In the 1870's infant mortality was

still nealy 300 per 1,000 live births in southern

Germany, but had fallen to 100 in Norway.

The decline in most industrialized countries

was particularly rapid in the first half of the

twentieth century, and is now down to 1 3 per

1,000 live births.51 The decline in mortality

was followed some decades later by a decline

in the birth rate, thus completing the demo

graphic transition from high birth rates and

high death rates to low birth rates and low

death rates. In industrialized countries, where

immunization, drugs and health services are

available, the loss of the protection afforded

by breastfeeding appears to result in higher

morbidity rather than higher mortality.

Developing countries

51. Infant mortality rates for developing

countries are usually based on a nation-wide

sample of the population, and under that

system it is not possible to make a reliable

47. Joint WHOIUNICEF meeting, op. cit.. p. 15. See also "Report of the Third Meeting of the ACC/SCN

Consultative Group on Maternal and Young Child Nutrition", Food and Nutrition Bulletin, United Nations

University, vol. 3, No. 1., Jauuary 1981.

48. Infant mortality is defined as occurring during the first 12 months of life, and is recorded as number of deaths

per 1,000 children born during the same year.

49. Thomas McKeown, The Modern Rise of Population. New York, Academic Press, 1976. p. 28.

50. B. Vahlquist, cited in Human Milk in the Modern World, op. cit.. chaptar 10.

51. World Development Report, 1980. World Bank, table 21 for high income industrialized countries.

11

breakdown into economically advanced areas,

poor urban areas, and rural areas (as used

above in para. 29), however, it is generally

believed to be much higher in the last two

areas 52 and one of the objectives of primary

health care is to improve their situation. The

protection and promotion of breastfeeding and

better weaning practices is part of the primary

health care strategy.

52. At the beginning of this century, infant

mortality in the country as a whole was often

200 to 300 per 1,000 live births, as it had

been 100 and 150 years ago in the countries

that are now industrialized. There have been

striking declines in recent decades, particularly

from the 1 930s to the 1 960s.5354The rate is

now down to a global average of 120 for

developing countries (excluding China) —

approximately 1 0 times the rate of the

industrialized countries. The target for the

year 2000 included in the International

Development Strategy of the Third Develop

ment Decade is to bring the rate down to 50,

still four times the level of industrialized

countries.51

Measures for reducing infant mortality

53. The reduction of infant mortality calls for

many measures in an economic, social and

cultural complex. They include clean water,

better hygiene, better environmental sanitation,

immunization and access to health services;

better feeding practices; and above all, the

education and status of women, which affect

the preceding factors.5556

54. Since poor infant feeding practices result

not only in illness, but also in death, improve

ment in mortality rates could come about

particularly by reducing the deaths due to

diarrhoeas, infections and weakened resistance

caused by . uor nutrition. "Evidence from the

developing countries indicates that infants

breastfed for less than six months, or not at

all, have a morality rate five to ten times higher

in the second six months of life than those

breastfed for six months or more "55

Number of infant deaths

55. Approximately 12 million infants die every

year, 11 million of them in developing

countries. If the rate of infant mortality is

brought down to the target level of 50 per

1,000, this will mean saving approximately 6

million infant lives. At high rates of infant

mortality, one third or approximately 4 million

of the infant deaths occur in the neonatal

period (0-28 days of age).57 These are due

to low birth weight, tetanus and other

infections, accidents and miscellaneous causes.

Better maternal nutrition could reduce the

number of infants born with low birth weight

(para. 21). The other two thirds of infant

deaths (from 28 days to one year of age),

amounting to approximately 7 million, are

caused inter alia by malnutrition, gastro

intestinal, respiratory and other communicable

diseases, and could be substantially reduced

by better feeding practices, especially pro

tecting and promoting breastfeeding and the

timely introduction of weaning foods.

VI.

ACTION BY THE INTERNATIONAL

COMMUNITY

56. Confirmation on the part of the medical

and scientific communities of the importance

of breastfeeding led the international

community to give more attention to the

question of appropriate infant and young child

feeding. During the 1960s the Protein

Advisory Group (PAG) of the United Nations

system 5859

encouraged studies in infant feeding

and in 1969 established an ad hoc working

group on feeding the pre-school child. In

1971, the Group published its report, "Feeding

the Pre-School Child", 53 which in section 4

treated the "sociocultural dynamics for

breastfeeding" and drew attention to a

dangerous decline. The Group also organized

the preparation and publication of a manual

for professional field-workers on feeding

infants and young children, which has been

translated into many languages and has

become a standard text used by health services

and voluntary organizations. It has been

frequently cited above.60

57. At the same time the advertising of infant

formula and free distribution of samples by

the infant food industry became a matter of

52. In Thailand, see J. Knodel and A. Chamratrithirong, " Infant and Child Mortality in Thailand: Levels,

Trends and Differentials as derived through indirect estimation techniques". Papers of the East-West

Population Institute, No. 57, 1978.

53. The Determinants and Consequences of Population Trends. United Nations, 1973, vol. I. chapter V. paras.58-7O.

54. General Assembly resolution 35/56, para. 48.

55. Thomas McKeown, The Modern Rise of Population, op. cit., p. 28. Walsh McDermott analysed New York

city's decline in infant mortality during the period 1900 to 1930, "Modern Medicine and the demographic

disease pattern of overly—traditional societies: A technological misfit". Journal of Medica\ Education.

vol. 41 (supplement) 1966.

56. "Maternal and Child Health:’, report by the Director-General, WHO. (A/32/9), 1979, para. 45.

57. Determinants and Consequences of Population Trends, op. cit.. para. 69.

58. The Protein Advisory Group, later renamed Protein-Calorie Advisory Group, consisted of experts in fields

related to nutrition aud advisad agencies in the United Nations system.

59. Protein-Ca.orie Advisory Group document 1 14/5.

60. Manual on Feeding Infants and Young Children, op. cit.

12

concern. In November 1970, in Bogota,

Colombia, the Pan American Health Organi

zation (PAHO) and UNICEF sponsored an

international meeting of paediatricians,

nutritionists, and representatives of the infant

food industry to discuss the problem. As an

immediate result of the meeting, at least one

of the larger companies changed some

marketing practices.

considered a report on "Priorities in child

nutrition in developing countries", prepared

under the direction of Dr. Jean Mayer, then

Professor of Nutrition, Harvard University

School of Public Health. One of the recom

mendations was that "UNICEF should continue

to support efforts to protect and promote the

practice of breastfeeding infants".63 The

Board conclusions included the following :

WHO AND UNICEF actions

"Particular emphasis was given to the effort to

arrest the decline of breastfeeding. Among

the many measures that might be advisable

was the control of advertising of infant and

weaning foods, for which it might be useful

to prepare model legislation and adopt social

measures for nursing mothers when they

worked outside their homes."64

58. During the early 1970s, the UNICEF

Executive Board took note of concern over the

decline of breastfeeding on a number of

occasions. The report of the Lome Conference61

noted that most of the country studies revealed

a lack of knowledge of proper weaning

procedures and that this was leading to an

abrupt or premature ending of breastfeeding

without the gradual introduction of transition

foods. As a result, increased co-operation

was recommended for nutrition education for

pregnant women and lactating mothers and

the production of weaning foods locally

produced.

59. A report on policy and programmes

concerning the young child 62 considered by

the UNICEF Board at its 1974 session,

suggested a number of actions to encourage

breastfeeding, including the study of reasons

for its decline; orientation and training of

medical and health personnel; public education;

ano support for nursing mothers. The Board

agreed that UNICEF should increase its

assistance in these areas. Support was also

approved for the Protein-Calorie Advisory

Group to promote, along with its other spon

soring agencies, co-operative action by

paediatricians, government agencies and the

infant-food industry in minimizing

problems in early weaning.

60. In 1974, the World Health Assembly

passed a resolution recommending the

encouragement of breastfeeding as the ideal

feeding in order to promote harmonious

physical and mental development of children;

calling for adequate social measures to support

breastfeeding mothers; and urging Member

States to review promotion activities for baby

foods (WHA. 27/43).

61.

In 1975 the UNICEF Executive Board

62. In reviewing UNICEF work in the field

of child nutrition during the Board session of

1 977, several delegations said that consi

derably increased emphasis was required to

discourage premature weaning from breast

feeding. The Board was informed that the

WHO collaborative study was under way and

hoped that it could lead to consideration in the

UNICEF/WHO Joint Committee on Health

Policy, and "a more systematic approach by

UNICEF to the problem".65

63. The following year the board was informed

that work had started in several countries with

WHO and UNICEF assistance to identify the

main factors influencing the decline of breast

feeding and to develop means of countering

these factors.66 The Board expressed its

support of an expansion of UNICEF

co-operation in this area, with WHO.

Meeting on Infant and Young Child

Feeding, October 1979

64. Intersecretariat consultations on the WHO

and UNICEF programme led to a joint decision

to convene a meeting on infant and young

child feeding in October 1979 in Geneva.

With representatives participating from

Governments, international agencies, the health

professions, the infant-food industry and non

governmental organizations, the meeting

recommended changes in hospital practices;

more support for the encouragement of breast

feeding through information and guidance

under the health care system; measures to

61. Children. Youth. Women and Development Plans in West and Central Africa, report of the Conference of

Ministers, Lome, Togo, May 1972 (UNICEF, Abidjan).

62. "The Young Child: Approaches to Action in Developing Countries", (E/ICEF/L. 1303).

63. "Priorities in Child Nutrition in Developing Countries, General Recommendations to UNICEF and

Governments", vol, I (E/ICEF/L. 1328).

64. Official Records of the Economic and Social Council, Fifty-ninth session. Supplement No. 6 (E/ICEF/639,

para. 66).

65. Official Records of the Economic and Social Council. Sixty-third session. Supplement No. 12

(E/ICEF/651, para. 120).

66. "General progress report of the Executive Director, Chapter II: Programme progress and trends"

(E'ICEF/654 (Part II), paras. 162-167).

13

ensure that women's nutritional and health

needs were met, especially during pregnancy;

changes in obstetrical procedure and practices

to facilitate breastfeeding; more information to

the health professions during training, and

orientation of other professions in contact with

the public; and stronger support system for

women working while continuing to

breastfeed.07

65. The meeting recommended follow-up

activities by various groups :

(a) Governments have a major responsibility

to work with communities to give the necessary

support to families living below the income

level which would enable them to provide food

for pregnant and nursing women, and infants

and young children. Often social measures

are also required for the support of breast

feeding, especially for working mothers;

(b) The health services and health professions

have a prime responsibility for the advice given

to women, the organization of maternity and

mother and child health care services, and the

training of professional, auxiliary and

community health workers;

(c) Industry has the responsibility to continue

to make supplies of breastmilk substitutes of

good quality for those who need them, but

promotion to the public should stop;

(d) Women's organizations should play a larger

part in community and national decisions in

this field, including the organization of

information campaigns, support networks for

breastfeeding mothers, and assistance in

monitoring good marketing practices; and

(e) The information media have an important

role for several audiences—families, mothers,

youth and others.

66. The meeting also recommended the

promotion and support of appropriate weaning

practices, with emphasis on the use of locally

available foods.

67. While recognizing that manufactured

infant formulas were excellent products for

infants who were not breastfed—and in fact

needed by many families who cannot afford

them—the meeting stated that promotion to

the public and to mothers should stop There

should be an international code of marketing

of infant formula and other breastmilk

substitutes. This should be supported by both

exporting and importing countries and observed

by all manufacturers. WHO and UNICEF were

requested to organize the process for its

preparation, with the involvement of all

concerned parties.

68. The World Health Assembly in May 1980

endorsed the statement and the recommenda

tions of the October meeting, and the work

under way for preparation of the international

code. UNICEF's co-operative effort with WHO

was endorsed in discussions of the UNICEF

Board at its 1980 session. Consultations

with concerned Governments, the infant-food

industry and non-governmental organizations

have taken place and a draft code (WHO

document EB67/20) was considered by the

Executive Board of WHO in January 1981>

and recommended to the 34th World Health

Assembly in May 1981 Jor adoption as a

“recommendation" to Governments in the terms

of the WHO constitution (Article 23).

Substance of the Code

69. The most important provisions of the

proposed Code 08 are contained in the

following extracts, which apart from the first

two on aim and scope, are generally taken

from the opening sentences of the various

articles :

“The aim of this Code is to contribute to

the provision of safe and adequate nutrition

for infants, by the protection and

promotion of breastfeeding, and by

ensuring the proper use of breastmilk

substitutes, when these are necessary, on

the basis of adequate information and

through appropriate marketing and

distribution." (Article 1)

“The Code applies to the marketing, and

practices related thereto, of the following

products : breastmilk substitutes, including

infant formula; other milk products, foods

and beverages, including bottle-fed

complementary foods when marketed or

otherwise represented to be suitable, with

or without modification, for use as a partial

or total replacement of breastmilk; feeding

bottles and teats. It also applies to their

quality and availability, and to information

concerning their use." (Article 2)

"Governments should have the responsibility

to ensure that objective and consistent

information is provided on infant and young

child feeding for use by families and those

involved in the field of infant and young child

nutrition..." (Article 4.1)

"There should be no advertising or other form

of promotion to the general public of products

within the scope of this Code." (Article 5.1)

67. Joint WHOjUNiCEF Meeting on infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva, WHO, 9-12 October 1979.

68. Dta,^^?!na.tj°^al c°de of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, Report by the Director-General. WHO,

(EB67/20), 10 December 1980.

14

"The health authorities in Member States should

take appropriate measures to encourage and

protect breastfeeding and promote the principles

of this Code..." (Article 6.1)

"The use by the health care system of profes

sional service representatives, mothercraft

nurses or similar personnel, provided or paid

for by manufacturers or distributors, should not

be permitted." (Article 6.4)

"Donations to institutions., of infant formula

.. should only be used or distributed for infants

who have to be fed on breastmilk substitutes."

(Article) 6.6)

"Health workers should encourage and protect

breastfeeding..." (Article 7.1)

"...Health workers should not give samples

of infant formula to pregnant women, mothers

of infants and young children, or members of

their families.' (Article 7.4)

"Labels should be designed to provide the

necessary information about the appropriate

use of the product, and so as not to discourage

breastfeeding.” (Article 9.1)

"The quality of products is an essential

element for the protection of the health of

infants and therefore should be of a high

recognized standard." (Article 10.1)

"Governments should take action to give effect

to the principles and rules of this Code, as

appropriate to their social and legislative

framework, including the adoption of national

legislation, regulations or other suitable

measures..” (Article 11,1)

UNICEF co-operation in programmes

to support breastfeeding and good

weaning practices

70. In all regions, UNICEF co-operates in

some activities and services in support of

breastfeeding and appropriate weaning

practices, some of which are of long standing.

Much wider extension is needed. UNICEF’s

co-operation includes support for :

- Reorientation of training of health personnel,

both pre-service and in-service, in

co-operation with WHO;

- Information programmes for use by women's

organizations and other local support

systems;

- Introduction of mother and child weighing

as a routine in maternal and child health

services;

- Maternal, infant and young child supple

mentary feeding through community

involvement, especially in primary health

care services;

- Local studies of infant and yong child

feeding practices;

- Extension of day-care facilities, especially

in low-income urban areas; and

- Local weaning food production through

agricultural planning, agricultural extension,

"applied nutrition", home or community

processing of foods, etc.

Some examples are given in the following

paragraphs.

Africa

71. In Kenya the gathering of data on breast

feeding has been incorporated into the

country's household sample survey system.

A research project is in process on the know

ledge, attitudes and practices of health workers

with respect to breastfeeding. The medical

curriculum is also being reviewed to remove

gaps or defects wich might lead to faulty

counselling and practice. The Kenya Institute

of Education is co-ordinating the study.

72. Over the past two years UNICEF has been

co-operating in a programme of courses for

women on nutrition education and the

preparation of weaning foods in the United

Republic of Tanzania. Co-operation has also

been extended for a project on the production

of soya beans, a main ingredient of the

weaning food lisha

Americas

73. In Brazil the promotion of breastfeeding

forms part of an overall country plan aimed at

incorporating the needs of children in national

development plans. UNICEF is co-operating

in a mass information and communications

programme providing support for technical

advice. This programme aims at :

- Enabling health centres and other relevant

parts of the public health network to educate

the mother, family members, community

workers, etc.;

- Educating medical and health personnel; and

starting to modify medical curricula;

- Motivating and influencing hospital adminis

trators, architects, the judiciary system, etc.,

so that efforts are made to set up systems

and attitudes that support and facilitate

breastfeeding in hospitals, work places,

maternity clinics, etc.:

- Influencing maternal attitudes to

breastfeeding; and

- Influencing the infant food industry.

74. The Government is undertaking a

systematic evaluation of the efforts under way,

including major action programmes in Sao

Paulo and Recife where breastfeeding had

declined rapidly over the past decade.

15

75. Special programmes to promote breast

feeding have been supported in the Caribbean

since the mid-1970s, beginning with surveys

on infant feeding partices in Jamaica;

motivation of professional, voluntary and

extension groups through training sessions;

and panel discussions and promotion via mass

media. Building on this experience, the

Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute, with

assistance from UNICEF and PAHO. organized

a technical group meeting in 1979 to draft

guidelines to promote successful breastfeeding.

Since then, the Institute, with some assistance

from UNICEF, has produced a breastfeeding

promotion package consisting of a manual,

slides, tapes and posters for the sensitization

of policy makers and health teams.69

76, There is concern about the decline of

breastfeeding throughout Central America.

Following the October 1979 meeting in

Geneva, the Institute for Nutrition in Central

America and Panama, with WHO support,

brought together representatives of the health,

education, social services and planning

ministries of six Central American countries in

Tegucigalpa, Honduras, in March 1980.

Recommendations now form the basis for

national action in each country. A

recommendation for “noting" a subregional

programme is before the current Board session

(E/ICEF/P/L. 2043 (REC)). It requests

assistance for training seminars and workshops;

preparation of educational materials; pilot

activities in mass media promotion; and

monitoring compliance with existing and

forthcoming national codes regulating the

promotion of breastfeeding substitutes.

77. The UNICEF regional office in Santiago

supported a seminar on breastfeeding in 1980.

One project for strengthening services for

children in areas of extreme poverty, in which

UNICEF participates in Chile, covers a number

of fields including the extension of breast

feeding. It provides for the training of health

personnel who, with the help of an orientation

manual and audio-visual material, are

promoting breastfeeding among mothers using

the health services.

78. In Mexico a rooming-in programme is

being supported by the Sistema Alimentario

Mexicano, a network of government agencies

involved in promoting improved food produc

tion and consumption habits, with the objective

of encouraging breastfeeding and close mother/

child contact.

Asia

79. Bangladesh. After substantial efforts at

attitudinal change about weaning with rural

women who were reluctant to consider the use

of local ingredients and locally produced